Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Definition of The Federal Funds Rate

Definition of The Federal Funds Rate

Uploaded by

Nguyễn DungOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Definition of The Federal Funds Rate

Definition of The Federal Funds Rate

Uploaded by

Nguyễn DungCopyright:

Available Formats

Definition of the Federal Funds Rate (Fed Funds Rate): The Fed Funds Rate -- short for Federal

Funds Rate -- is the short-term interest rate at which U.S. depository institutions (commercial banks, savings and loan associations, credit unions, mutual savings banks, etc.) lend to each other overnight within the Federal Reserve system (minimum loan amount is $1,000,000.) In most cases, when economists, academics, investors and central bankers refer to the Federal Funds Rate, they are actually referring to the Fed Funds Rate Target. The U.S. Federal Reserve sets a target for the Federal Funds Rate, and keeps the rate on target by executing open market operations, i.e., the buying and selling of U.S. Treasuries, mortgagebacked and agency securities via repurchase agreements and reverse repurchase agreements (also known as "repos.") These repo transactions take place at the Trading Desk inside the Federal Reserve Bank of New York*. The Fed sells debt when it wants to drain cash from the banking system, and buys it when the Fed wants to pump money into the system. Open market trading with primary dealers is the Fed's main tool used to manipulate the fed funds rate. The Fed has three other tools at its disposal it can use to achieve its monetary policy goals: tweaking bank reserve requirement ratios, modifying the terms associated with borrowing from the Fed's discount window and, as of October 1, 2008, adjusting the rate of interest paid to banks that have required and excess reserve balances on deposit at the Fed[1]. The Fed Funds Target Rate (FFTR) is America's most important and most influential benchmark interest rate. The FFTR can be described as the "main" or "key" interest rate for the United States. The interest rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) uses the Fed Funds Target Rate as its most potent tool for regulating the U.S. economy, lowering it when the economy needs a boost, and raising it when the rate of inflation is too high. NB: On December 16, 2008, the FOMC decided to take the unusual step of setting a target range of 0% - 0.25% for the fed funds rate, as opposed to setting a simple target. Since the FOMC can't set short-term rates below zero, it has devised unique and unorthodox tools it will use to promote economic growth. From a December 16 press release: "...The focus of the Committee's policy going forward will be to support the functioning of financial markets and stimulate the economy through open market operations and other measures that sustain the size of the Federal Reserve's balance sheet at a high level. As previously announced, over the next few quarters the Federal Reserve will purchase large quantities of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities to provide support to the mortgage and housing markets, and it stands ready to expand its purchases of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities as conditions warrant. The Committee is also evaluating the potential benefits of purchasing longer-term Treasury securities. Early next year, the Federal Reserve will also implement the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility to facilitate the extension of credit to households and small businesses. The Federal Reserve will continue to consider ways of using its balance sheet to further support credit markets and economic activity..." U.S. law requires that depository institutions keep a certain percentage of their customers' money on reserve at one of the 12 regional Federal Reserve banks situated in major U.S. cities:

Atlanta, GA Boston, MA Chicago, IL Cleveland, OH Dallas, TX Kansas City, MO

Minneapolis, MN New York City, NY Philadelphia, PA Richmond, VA San Francisco, CA St. Louis, MO

Banks try to stay as close to the reserve limit as possible without going under it, lending money back and forth so as to maintain a reserve level that is both legal and allows banks to maximize profits. The FFTR is set by the FOMC, the Fed's 12-member monetary policy body (7 Fed Governors plus 5 Federal Reserve Bank presidents). The FOMC convenes regularly scheduled monetary policy meetings eight time per year, and it is at these meetings that the FOMC decides whether to raise, lower or leave the FFTR unchanged. During times of economic crisis, the chairman of the Federal Reserve may at any time convene an emergency FOMC monetary policy meeting and raise or lower the FFTR, depending on the nature of the crisis. As America's cardinal short-term interest rate, the FFTR influences some of the most important market interest rates throughout the world, including the LIBOR rates and the U.S. Prime Rate. Banks try to stay as close to the reserve limit as possible without going under it, lending money back and forth so as to maintain a reserve level that is both legal and allows banks to maximize profits. The FFTR is set by the FOMC, the Fed's 12-member monetary policy body (7 Fed Governors plus 5 Federal Reserve Bank presidents). The FOMC convenes regularly scheduled monetary policy meetings eight time per year, and it is at these meetings that the FOMC decides whether to raise, lower or leave the FFTR unchanged. During times of economic crisis, the chairman of the Federal Reserve may at any time convene an emergency FOMC monetary policy meeting and raise or lower the FFTR, depending on the nature of the crisis. As America's cardinal short-term interest rate, the FFTR influences some of the most important market interest rates throughout the world, including the LIBOR rates and the U.S. Prime Rate. Introduction: On December 6 1994, Orange County, a prosperous district in California, declared bankruptcy after suffering losses of around $1.6 billion from a wrong-way bet on interest rates in one of its principal investment pools. The pool was intended to be a conservative but profitable way of managing the countys cashflows, and those of 241 associated local government entities. Instead, it triggered the largest financial failure of a local government in US history. Robert Citron, the hitherto widely respected Orange County treasurer who controlled the $7.5 billion pool, had riskily invested the pools funds in a leveraged portfolio of mainly interestlinked securities. His strategy depended on short-term interest rates remaining relatively low when compared with medium-term interest rates. But from February 1994, the Federal Reserve

Bank began to raise US interest rates, causing many securities in Orange Countys investment pool to fall in value. During much of 1994, Citron ignored the shift in the interest rate environment and the mounting paper losses in his portfolio. But by the end of 1994, demands for billions of dollars of collateral from Citrons Wall Street counterparties, and the threat of a run on deposits from spooked local government investors, created a liquidity trap that he could not escape. Citron could not have undertaken such a risky investment strategy if his actions had been subject to informed and independent risk oversight, and detailed risk-averse investment guidelines. Following the debacle, Orange County revised many aspects of its control procedures and its financial governance, and established a stricter set of investment policies.

Lessons Learnt: - Beware the unconstrained star performer, even when he or she has a long track record. Where theres excess reward, theres risk though it might take time to surface; - If the organisational structure, planning and risk oversight mechanisms of an institution are fractured, it is easy for powerful individuals to hide risk in the gaps; - Borrowing short and investing long means liquidity risk, as every bank knows; - Risk-averse investors must tie investment objectives to investment actions by means of a strict framework of investment policies, guidelines, risk reporting and independent and expert oversight; - Risk reporting should be complete, and easily comprehensible to independent professionals. Strategies that are not possible to explain to third parties should not be employed by the risk averse. The Story: Orange County treasurer Robert Citron was no new kid on the block. He had been treasurer since 1972 and in early 1994, at about the time his investment strategy began to go sour, he survived an election that focused public attention on his financial management of the Orange County investment pool. Citron managed to convince voters that the criticisms, which turned out to be close to the mark, were politically motivated. Citrons strongest card was his track record. Earnings from the investment pool had been an increasingly important part of the Orange County budget since the late 1970s, leading to a relaxation of the rules surrounding how funds could be invested. In addition to the county itself, municipal entities such as the Orange County cities of Anaheim and Irvine, along with various local government authorities and services, were attracted to the investment pool by the unusually good rates of return it offered. These investors put money that they raised from taxes and other sources into the pool, in the hope that the cash would grow before they had to spend it on vital public services. Excess returns from the pool were particularly welcome in the early 1990s: the local political environment was set against raising taxes and local government finances were under increasing strain. Some municipal entities even began to borrow money to increase their pool investments. (According to some commentators, the excess returns over the years amounted to hundreds of millions of dollars and, in a limited sense, considerably offset the eventual loss.)

Few municipal investors in the pool quizzed Citron on how he worked his magic, or analysed independently the level of risk he was running to gain excess returns. They took comfort from the fact that Orange County was itself heavily invested in the pool. However, the board of supervisors that acted as the principal oversight for Citrons actions as Orange County treasurer lacked financial sophistication. Orange County also failed to surround Citron with a compensating infrastructure of strict investment policies, risk controls, regular and detailed reporting, and independent oversight. This mattered more and more as the aim of the pool gradually turned towards making, rather than managing, money. Through the early 1990s, Citron enjoyed his growing importance as someone who conjured up extra money for public services. The amount of public money in the pool grew quickly until in 1994, Citron was investing $7.5 billion in US agency notes of various kinds. He was a popular port of call for salesmen from Wall Streets big brokerage firms, particularly those from securities giant Merrill Lynch. Later, these salesmen would say they were merely servicing an experienced and savvy investor, while Citron would claim he had been misled about the riskiness of the instruments. One thing is certain: while the pool offered greater returns than those of similar cash management pools, it did so only by taking on more risk. In particular, Citron gambled that medium-term interest-bearing securities would maintain or increase their value. He used various techniques to leverage his $7.5 billion of funds into more than $20 billion of investments so that both the returns and the risks were multiplied. One way he did this was to enter into contracts known as reverse repurchase agreements, which allowed him to use securities the pool had already purchased as collateral on further borrowings, and further cycles of investing. But these agreements left him vulnerable to calls for more collateral if the market value of the original collateral fell. Citron also used around $2.8 billion of structured notes, or derivatives, to increase his bet on the structure of the interest rate yield curve. These included many inverse floaters notes whose coupon falls as interest rates rise as well as index amortising notes and collateralised mortgage obligations. The relative complexity of the instruments, the daisy-chain structure of the portfolio and Citrons limited financial reporting made it difficult for independent critics to understand or prove how risky the strategy really was. But the end result is clear: the pool transformed short-term funds intended for vital public services into a risky and leveraged investment in medium-term financial instruments. As long as short-term interest rates remained low, as they did in the early 1990s, Citrons bet on the relative value of medium-term interest rate-linked securities paid off and all concerned prospered. The strategy soured with a shift in policy by the Federal Reserve in February 1994. That month saw the first of a succession of hikes in interest rates that ultimately saw the Fed raise rates by some 2.25 per cent over the course of 1994. By November, the investment pool was in crisis as the value of its interest rate-sensitive medium-term investments sank, and calls for more collateral arrived from Wall Street. Citrons counterparties prepared to seize and liquidate billions of dollars of the investment pools collateral, while the government entities that had invested in the fund, lacking credible

reassurances, looked to withdraw their money. On December 1, Citron admitted the fund had lost around $1.5 billion or around 20 per cent of its value. He resigned on December 3, as Orange County officials desperately tried to work out an agreement with their Wall Street creditors. That agreement proved elusive, and Wall Street institutions began to sell off the securities they held as collateral against their agreements with Orange County. The Orange County Board of Supervisors took legal advice and declared bankruptcy on December 6, a move that prevented investors withdrawing any more of their funds. It also set the scene for a public auction of Citrons investment portfolio so that the proceeds could be reinvested in safe, and liquid, shortdated government stock. By January 19, with this restructuring completed, Orange Countys financial firestorm was over but its losses had crystallised at around $1.69 billion. Some expert commentators have argued that it could have cut this bill if only it had had the nerve to hang onto some of Citrons investment portfolio. But this makes little difference to the fundamental lessons to be learned from the debacle. Citron exposed a set of conservative investors with specific funding needs to a risky portfolio. He failed to communicate the extent of the market risk, or liquidity risk, to either the investors or to his supervisory board though he did not try to hide the fundamentals of his strategy. (Had he properly assessed and communicated the level of risk, the pool would not have attracted riskaverse funds in the first place.) But it is wrong to blame one individual. The risk managers of Canadian investment bank CIBC recently compared the Orange County failure to that of Barings Bank, pointing out that in these otherwise very different debacles, the man in charge showed excellent results at first, and was therefore allowed to transact without proper surveillance or controls (Crouhy et al, 2001). Orange County is primarily a story of what happens when the desire for excess returns overrides risk oversight. The Aftermath: Restitution and Recovery Citron eventually pleaded guilty to six felony counts. However, the charges were largely to do with a misallocation of returns between the county and other municipal entities, and Citron does not seem to have been motivated by personal gain of any direct and obvious kind. He paid a $100,000 fine and spent less than a year under house arrest. If that seems a lenient sentence, then Orange Countys recovery was also swifter than might have been expected. It had to cut back on spending and social service provision, and in 1995 and 1996 it took on massive additional debt in the form of special long-term recovery bonds to cover its losses. But thanks to increased tax revenues from a buoyant local economy, it was able to exit from bankruptcy in only 18 months. With new executives in charge, it instituted a series of governance structures and reforms. These included oversight committees, an internal auditor who reported directly to the supervisors, a commitment to long-range financial planning and a stricter written policy for investments. In December 1997, Moodys Investors Service rewarded the county with an investment grade rating for key borrowings. The new Orange County investment policy statement establishes safety of principal, and liquidity, as the primary objectives of the fund, with yield as a secondary objective. More

specifically it prohibits borrowing for investment purposes (ie, leverage), reverse repurchase agreements, most kinds of structured notes (such as inverse floaters) and derivatives such as options. The same document bans the treasury oversight committee and other designated employees from receiving gifts, and obliges them to disclose economic interests and conflicts of interest. The county treasurer now has to submit monthly reports to the investors and other key county officers that contain sufficient information to permit an informed outside reader to evaluate the performance of the investment programme. On June 2, 1998, Orange County reached a massive $400 million settlement with Merrill Lynch, the firm it held most responsible for steering Citron towards what the county deemed risky and unsuitable securities. Thomas Hayes, who led the countys litigation, said he regarded the settlement as fair while Janice Mittermeier, Orange County CEO in its recovery period, said the resolution assures county taxpayers that those responsible for the losses that caused the countys bankruptcy are being held accountable. Merrill Lynch maintained as part of the settlement that it had acted properly and professionally in our relationship with Orange County. It cited the costs, distraction and uncertainty of further litigation as the reason it had come to make such an expensive settlement, while assuring its investors that it had already fully reserved against such an outcome. Together with settlements from more than 30 other securities houses, law firms and accountancy firms that the county held partly responsible for the losses, the money from Merrill Lynch meant that some 200 municipal and governmental agencies could be finally made good. In February 2000, officers appointed by the courts paid out around $864 million to various government entities that had suffered from the collapse. Five years on from the bankruptcy, it was a big day for the smaller creditors. But on the same day, Orange County supervisor Jim Silva reminded local reporters that the county itself was still paying off some $1.2 billion of the recovery bonds issued in 1995 and 1996 and would be for several decades, unless it was able to speed up repayments. Timeline: Pips Begin to Squeak in Orange County February 1994: Fed makes the first of a series of interest rate hikes, and so threatens the directional bet on interest rates built into the Orange County investment pool. September 1994: Orange County treasurer Robert Citron tries to calm growing fears among investors. November 1994: Auditors find that the pool has massively lost value. December 1, 1994: Citron confirms that the pool faces $1.5 billion loss. December 3, 1994: Citron resigns. December 6, 1994: Prompted by due date of certain repo transactions, Orange Country files for Chapter 9 protection.

May 2, 1995: US Bankruptcy Court endorses settlement of what is left in the investment pool. Some 241 participants get 77 cents in each dollar of their investment balance as a cash distribution. November 19, 1996: Citron is sentenced to a year in jail and $100,000 fine. December 17, 1997: Moodys Investors Service rewards the countys recovery and new investment policies with an investment grade rating for key county borrowings. June 2, 1998: Orange County reaches a $400 million settlement of its lawsuit against Merrill Lynch. February 25, 2000: Some 200 municipal and governmental agencies finally made good in a disbursement of $864 million. But Orange County continues to pay off the recovery bonds it issued in 1995/6 to fund the bulk of the pools losses.

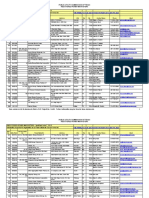

You might also like

- 4 Sem Bcom - Advanced Corporate AccountingDocument56 pages4 Sem Bcom - Advanced Corporate AccountingDipak Mahalik57% (7)

- 11 CHPTDocument6 pages11 CHPTI IvaNo ratings yet

- Summary of Anthony Crescenzi's The Strategic Bond Investor, Third EditionFrom EverandSummary of Anthony Crescenzi's The Strategic Bond Investor, Third EditionNo ratings yet

- Comparision of Banking System of Us, Europe, India-1Document36 pagesComparision of Banking System of Us, Europe, India-1Rashmeet Kaur100% (2)

- PersonalManager ListDocument10 pagesPersonalManager ListSneha LiveitNo ratings yet

- Banking Systems: From Regional To National: 3.1. The American Banking SystemDocument25 pagesBanking Systems: From Regional To National: 3.1. The American Banking SystemsheshadiNo ratings yet

- Fed and Financial PolicyDocument2 pagesFed and Financial PolicyjosephjbucciNo ratings yet

- Interest Rate Determination TopicsDocument6 pagesInterest Rate Determination TopicsGian ErickaNo ratings yet

- Money and The Federal Reserve System: Learning ObjectivesDocument16 pagesMoney and The Federal Reserve System: Learning ObjectivesNeven Ahmed HassanNo ratings yet

- How The U.S. Government Formulates Monetary PolicyDocument3 pagesHow The U.S. Government Formulates Monetary Policykljlkhy9No ratings yet

- Describe The Functions Performed by Federal Reserve BanksDocument3 pagesDescribe The Functions Performed by Federal Reserve BanksShandyNo ratings yet

- Federal Reserve Personal Finance 2017Document16 pagesFederal Reserve Personal Finance 2017api-354625480No ratings yet

- MBF Homework 5Document19 pagesMBF Homework 5JerryNo ratings yet

- Tools of Monetary Policy: Open - Market Operations Discount Rate Reserve RequirementsDocument15 pagesTools of Monetary Policy: Open - Market Operations Discount Rate Reserve RequirementsAngelica BeltranNo ratings yet

- Monetary PolicyDocument27 pagesMonetary PolicyYinying GuoNo ratings yet

- Financial and Fiscal PolicyDocument7 pagesFinancial and Fiscal PolicyLeonardo BanayNo ratings yet

- Federal ReserveDocument5 pagesFederal ReserveMarlo John Mana-ayNo ratings yet

- Federal Funds Rate - What It Is, How It's Determined, and Why It's ImportantDocument6 pagesFederal Funds Rate - What It Is, How It's Determined, and Why It's ImportantDat TranNo ratings yet

- Federal Reserve Tutorial: (Page 1 of 8)Document8 pagesFederal Reserve Tutorial: (Page 1 of 8)Nishant RajNo ratings yet

- Money, The Price Level, and InflationDocument61 pagesMoney, The Price Level, and InflationGianella Zoraya Torres AscurraNo ratings yet

- The Structure and Functions of The Federal Reserve System: Policy, Banking Supervision, Financial ServicesDocument18 pagesThe Structure and Functions of The Federal Reserve System: Policy, Banking Supervision, Financial ServicesJapish MehtaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Financial Markets and Institutions:: Hide Links Within DefinitionsDocument10 pagesIntroduction To Financial Markets and Institutions:: Hide Links Within DefinitionsfananjelinaNo ratings yet

- Check Negotiable Instrument Check Promissory Note DrawerDocument7 pagesCheck Negotiable Instrument Check Promissory Note DrawerghnyerNo ratings yet

- Fin 464 Chapter 2Document18 pagesFin 464 Chapter 2Ibteda Bin Sakayet 2013312630No ratings yet

- Ch25 (Money, The Price Level, and Inflation)Document66 pagesCh25 (Money, The Price Level, and Inflation)MKMikeNo ratings yet

- Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy: ObjectivesDocument9 pagesMoney, Banking, and Monetary Policy: ObjectivesKamalpreetNo ratings yet

- Federal Funds RateDocument2 pagesFederal Funds RateNicolas JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Neoma How Is Climate Change Impacting The Financial System Oct 2022Document30 pagesNeoma How Is Climate Change Impacting The Financial System Oct 2022XX YYNo ratings yet

- The Money Supply and The Federal Reserve SystemDocument18 pagesThe Money Supply and The Federal Reserve SystemYuri AnnisaNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy ToolsDocument8 pagesMonetary Policy ToolsFreddie254No ratings yet

- Fixed Income BulletinDocument12 pagesFixed Income BulletinfaiyazadamNo ratings yet

- Chap 12Document29 pagesChap 12janvi100No ratings yet

- FM Qu and AnswerDocument11 pagesFM Qu and AnswerMikiyas AnberbirNo ratings yet

- Chapter-4, Fin-433, AlifDocument5 pagesChapter-4, Fin-433, AlifMd Al Alif Hossain 2121155630No ratings yet

- Note On Monet PolDocument21 pagesNote On Monet Polaudace2009No ratings yet

- Lecture 9 International Financial SystemDocument30 pagesLecture 9 International Financial SystemGina WaelNo ratings yet

- Fed Rate Cut N ImplicationsDocument8 pagesFed Rate Cut N Implicationssplusk100% (1)

- CHAPTER 4 NarrativeDocument5 pagesCHAPTER 4 NarrativeJoyce Anne GarduqueNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Activities and Charactristics Under Depository InstitutionsDocument7 pagesChapter 4 - Activities and Charactristics Under Depository Institutionssonchaenyoung2No ratings yet

- Economic Development CHAPTER 14Document39 pagesEconomic Development CHAPTER 14Angelica BeltranNo ratings yet

- Finanzas Internacionales: Ejercicios de La Tarea 5Document10 pagesFinanzas Internacionales: Ejercicios de La Tarea 5gerardoNo ratings yet

- UNIT TWO Central BanksDocument6 pagesUNIT TWO Central BankswubeNo ratings yet

- DF 53 Fmbo2Document20 pagesDF 53 Fmbo2Ashish PatangeNo ratings yet

- Unit 1: The Role of Financial Regulation: Background ContextDocument6 pagesUnit 1: The Role of Financial Regulation: Background ContextPulkit AggarwalNo ratings yet

- 4.2.4. Interest Rate DeterminationDocument21 pages4.2.4. Interest Rate DeterminationGuy WilkinsonNo ratings yet

- Functions of Central Bank in An EconomyDocument4 pagesFunctions of Central Bank in An EconomyShafiq MirdhaNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy and Central Banking: Geriel I. Fajardo 3FM3 Assignment 2Document3 pagesMonetary Policy and Central Banking: Geriel I. Fajardo 3FM3 Assignment 2Geriel FajardoNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy and The Economy: Maimoona Sajid ButtDocument50 pagesMonetary Policy and The Economy: Maimoona Sajid ButtUmer Farooq MirzaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Federal Reserve SystemDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Federal Reserve Systemaflbrpwan100% (1)

- Rates and ConceptsDocument7 pagesRates and ConceptsRaul JainNo ratings yet

- fmim.16.Ch11B ChapterDocument8 pagesfmim.16.Ch11B ChapterAhmed MujtabaNo ratings yet

- The Investment Function in BankingDocument21 pagesThe Investment Function in Bankingcyclone man100% (1)

- Tools of Monetary PolicyDocument23 pagesTools of Monetary PolicyNandiniNo ratings yet

- Acknowledgments: From Tariq RazaDocument17 pagesAcknowledgments: From Tariq Razas_alimazharNo ratings yet

- Bangko Sentral NG PilipinasDocument54 pagesBangko Sentral NG PilipinasHyokashi ZakishNo ratings yet

- Central Bank Deposits Federal Reserve BankDocument2 pagesCentral Bank Deposits Federal Reserve Bankarvin cleinNo ratings yet

- The Repo MarketDocument16 pagesThe Repo MarketmeetozaNo ratings yet

- Life After Debt - Debtless by 2012, The U.S and The World Without US Treasury Bonds (FOIA Document)Document43 pagesLife After Debt - Debtless by 2012, The U.S and The World Without US Treasury Bonds (FOIA Document)Ephraim DavisNo ratings yet

- Role & Importance of SBPDocument16 pagesRole & Importance of SBPadnanzaghumNo ratings yet

- US Banking System OverviewDocument2 pagesUS Banking System OverviewAilénVillalbaNo ratings yet

- Central Banks, Their Functions and Role: Monetary Policy Bank Regulation Provide Financial Services HistoryDocument10 pagesCentral Banks, Their Functions and Role: Monetary Policy Bank Regulation Provide Financial Services HistoryJaypee JavierNo ratings yet

- Porter's Five Forces ModelDocument4 pagesPorter's Five Forces ModelNguyễn DungNo ratings yet

- Principles of Bank Management - 1Document60 pagesPrinciples of Bank Management - 1Nguyễn Dung0% (1)

- Chuyªn §Ò Hi®rocacbon Kh«ng No Nguyễn Văn NamDocument4 pagesChuyªn §Ò Hi®rocacbon Kh«ng No Nguyễn Văn NamNguyễn DungNo ratings yet

- Fauji Fertilizer RatiosDocument86 pagesFauji Fertilizer RatiosnickchikNo ratings yet

- Saving and Deposit Analysis of Rastriya Banijya Bank Limited 1 PDFDocument36 pagesSaving and Deposit Analysis of Rastriya Banijya Bank Limited 1 PDFSaipal Education Help Desk100% (1)

- Purisima v. Philippine Tobacco Institute, Inc.Document2 pagesPurisima v. Philippine Tobacco Institute, Inc.Charmila Siplon50% (2)

- Lecture 10 FINM2401 CAPM and Cost of CapitalDocument56 pagesLecture 10 FINM2401 CAPM and Cost of CapitalThomasNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Franchise Operation - FranchisorDocument4 pagesAccounting For Franchise Operation - FranchisorJanella Umieh De UngriaNo ratings yet

- Hedging Strategies Using Futures: Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives, 9th EditionDocument19 pagesHedging Strategies Using Futures: Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives, 9th EditionAvNo ratings yet

- Advantages of A Sole ProprietorshipDocument3 pagesAdvantages of A Sole Proprietorshiplaur33nNo ratings yet

- Babylon SummaryDocument5 pagesBabylon SummaryAditya Pandey100% (1)

- Capitec Case StudyDocument6 pagesCapitec Case StudyMpho SeutloaliNo ratings yet

- Confidential CS/APR2006/MAT112: Do Not Turn This Page Until You Are Told To Do SoDocument8 pagesConfidential CS/APR2006/MAT112: Do Not Turn This Page Until You Are Told To Do SoFara LyaNo ratings yet

- Rbi Monetary PolicyDocument5 pagesRbi Monetary PolicyRohit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Nepal Financial InclusionDocument18 pagesNepal Financial InclusionSanup KhanalNo ratings yet

- Lec1 - Introduction To AccountingDocument47 pagesLec1 - Introduction To AccountingDylan Rabin PereiraNo ratings yet

- Conomic Eview RipuraDocument359 pagesConomic Eview RipuraAswinNo ratings yet

- Case Study: Colgate Palmolive Precision Toothbrush: Submitted By: Group-10 Section-ADocument4 pagesCase Study: Colgate Palmolive Precision Toothbrush: Submitted By: Group-10 Section-AVaibhav MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Tax Card 2021 2022Document26 pagesTax Card 2021 2022AqeelAhmadNo ratings yet

- Budgeting Quiz Answer KeyDocument5 pagesBudgeting Quiz Answer KeyDeniseNo ratings yet

- A Research Paper On Investment Awareness Among IndianDocument18 pagesA Research Paper On Investment Awareness Among IndianElaisa AurinNo ratings yet

- Pas 1Document52 pagesPas 1Justine VeralloNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice Problems Chapter 6Document7 pagesMultiple Choice Problems Chapter 6Dieter LudwigNo ratings yet

- Brook Stone SuitDocument170 pagesBrook Stone SuitMarco Bajak MirandaNo ratings yet

- Test 1 - 2022 08 17Document3 pagesTest 1 - 2022 08 17MiclczeeNo ratings yet

- Sublease FormatDocument6 pagesSublease FormatNan MallNo ratings yet

- 04 Edu91 FM Practice Sheets FM Solution (Not To Print)Document154 pages04 Edu91 FM Practice Sheets FM Solution (Not To Print)Krutarth VyasNo ratings yet

- Letter Backing Jere HochmanDocument1 pageLetter Backing Jere HochmantauchterlonieDVNo ratings yet

- Exercise For Mid TestDocument11 pagesExercise For Mid TestNadia NathaniaNo ratings yet

- Khammam DCCBDocument4 pagesKhammam DCCBGuttula GirishNo ratings yet

- Amendment of By-Laws For Members (By-Laws of Institute of Engineers of The Philippines)Document17 pagesAmendment of By-Laws For Members (By-Laws of Institute of Engineers of The Philippines)meecheekohNo ratings yet

- SAP RE FX v3 PDFDocument16 pagesSAP RE FX v3 PDFharikrishnaNo ratings yet