Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Inspiration and Incarnation: Denis Farkasfalvy

Inspiration and Incarnation: Denis Farkasfalvy

Uploaded by

stjeromesCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- A2 UNIT 4 Test Answer Key HigherDocument2 pagesA2 UNIT 4 Test Answer Key HigherMaxi Comas60% (5)

- (Extract) (Nicholas Lombardo) LogicDesireDocument15 pages(Extract) (Nicholas Lombardo) LogicDesireJtavidNo ratings yet

- Anne HuntDocument13 pagesAnne HuntstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Fides Et Ratio NotesDocument2 pagesFides Et Ratio NotesBrittanyNo ratings yet

- Does Suffering Make SenseDocument74 pagesDoes Suffering Make SensejonicdaoNo ratings yet

- Being and Hayah - ARIGA TetsutaroDocument22 pagesBeing and Hayah - ARIGA Tetsutarorio rio rioNo ratings yet

- Bonaventure Journey of The Mind Into GodDocument31 pagesBonaventure Journey of The Mind Into GodJelena StankovićNo ratings yet

- Testimony of SimplicityDocument14 pagesTestimony of Simplicitybbishop2059No ratings yet

- 4-1 06 Lahav - Quest For WisdomDocument14 pages4-1 06 Lahav - Quest For WisdomarabelmNo ratings yet

- Theravada Methods of Intepretation On Buddhist ScripturesDocument44 pagesTheravada Methods of Intepretation On Buddhist ScripturesHueBaoNo ratings yet

- Moral Market Freer Market - John MilbankDocument7 pagesMoral Market Freer Market - John MilbankJoel Arthur EatonNo ratings yet

- The Legacy of Yves RaguinDocument9 pagesThe Legacy of Yves RaguinstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Olivier Clement and Paul EvdokimovDocument16 pagesOlivier Clement and Paul Evdokimovstjeromes100% (2)

- Tafe NSW: Knowledge AssessmentDocument30 pagesTafe NSW: Knowledge AssessmentDibyendu Karmakar100% (3)

- Aquinas, Science, and Human Uniqueness: An Integrated Approach to the Question of What Makes Us HumanFrom EverandAquinas, Science, and Human Uniqueness: An Integrated Approach to the Question of What Makes Us HumanNo ratings yet

- Sarda y Salvany Félix - Liberalism Is A SinDocument94 pagesSarda y Salvany Félix - Liberalism Is A SinMihai IgneaNo ratings yet

- Augustine and Plato Correlation of WorksDocument4 pagesAugustine and Plato Correlation of Worksstudub26No ratings yet

- Why I Do Not Attend Case Conferences P MeehlDocument11 pagesWhy I Do Not Attend Case Conferences P MeehlIgnacio J. Sandino Pérez100% (1)

- Lecturer Rev. Dr. David K. Mbugua Description:: Fundamental Moral Theology OneDocument3 pagesLecturer Rev. Dr. David K. Mbugua Description:: Fundamental Moral Theology OneKIZITO BONNo ratings yet

- Ethics as a Work of Charity: Thomas Aquinas and Pagan VirtueFrom EverandEthics as a Work of Charity: Thomas Aquinas and Pagan VirtueNo ratings yet

- Infallibility and ContraceptionDocument10 pagesInfallibility and ContraceptionPaul Horrigan100% (1)

- Fides Et Ratio As The Perpetual Journey of Faith and ReasonDocument23 pagesFides Et Ratio As The Perpetual Journey of Faith and ReasonClarensia AdindaNo ratings yet

- Jesus and The Son of ManDocument10 pagesJesus and The Son of ManRezart BekaNo ratings yet

- Excursus On Fear of The LordDocument3 pagesExcursus On Fear of The LordMaria Mercedes GuaitaNo ratings yet

- Dei Filius and The Fides Et Ratio ProblemDocument15 pagesDei Filius and The Fides Et Ratio Problemrog1rio1tadeu1mesquiNo ratings yet

- Radical Orthodoxy & Christian Psychology, Milbank & OliverDocument24 pagesRadical Orthodoxy & Christian Psychology, Milbank & OliveriamrabbitholeNo ratings yet

- Theological Mysteries In Scientific PerspectiveFrom EverandTheological Mysteries In Scientific PerspectiveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Psychological PrayerDocument5 pagesPsychological PrayerAdeniran VictorNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology of ReligionDocument5 pagesPhenomenology of ReligionJaimon ThadathilNo ratings yet

- Reidblackman ChurchlandDocument8 pagesReidblackman ChurchlandYisroel HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Elisabeth of Schönau & Women's SpiritualityDocument15 pagesElisabeth of Schönau & Women's SpiritualityPedroNo ratings yet

- ! - Bloor, Joshua - New Directions in Western Soteriology - Theology, May 2015, Vol 118 Iss 3Document9 pages! - Bloor, Joshua - New Directions in Western Soteriology - Theology, May 2015, Vol 118 Iss 3YuriNo ratings yet

- Aphraates The SageDocument2 pagesAphraates The SageDarry BlanciaNo ratings yet

- Plunged into the Trinity: Our Sacramental Becoming: Essays in Sacramental EcclesiologyFrom EverandPlunged into the Trinity: Our Sacramental Becoming: Essays in Sacramental EcclesiologyNo ratings yet

- Recognizing the Gift: Toward a Renewed Theology of Nature and GraceFrom EverandRecognizing the Gift: Toward a Renewed Theology of Nature and GraceNo ratings yet

- Kreeft4 Nature GodDocument18 pagesKreeft4 Nature GodrichardNo ratings yet

- Agape and Bhakti with Bataille and Mark at Loyola and St. Francis: The Mysticism of ReconciliationFrom EverandAgape and Bhakti with Bataille and Mark at Loyola and St. Francis: The Mysticism of ReconciliationNo ratings yet

- 4800ADTE040 de NovissimisDocument62 pages4800ADTE040 de NovissimisThomist AquinasNo ratings yet

- Alan Jones's Reimagining Christianity Back To RomeDocument9 pagesAlan Jones's Reimagining Christianity Back To RomeServant Of TruthNo ratings yet

- A Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyFrom EverandA Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyNo ratings yet

- Against Inclusiveness: How the Diversity Regime is Flattening America and the West and What to Do About ItFrom EverandAgainst Inclusiveness: How the Diversity Regime is Flattening America and the West and What to Do About ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- The Tridentine Genius of Vatican IIDocument11 pagesThe Tridentine Genius of Vatican IIstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Descartes Locke 1 PDFDocument36 pagesDescartes Locke 1 PDFRenefe RoseNo ratings yet

- Blanchette Aquinas' Conception of The Great Chain of Being A More Considered Reply To LovejoyDocument2 pagesBlanchette Aquinas' Conception of The Great Chain of Being A More Considered Reply To LovejoymartinezruizcmNo ratings yet

- God Needs Salvation: A New Vision of God for the Twenty First CenturyFrom EverandGod Needs Salvation: A New Vision of God for the Twenty First CenturyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 11 LemeniDocument13 pages11 LemeniMirceaNo ratings yet

- John Milbank S Theological Ontology of GiftDocument110 pagesJohn Milbank S Theological Ontology of GiftМикола ОсипенкоNo ratings yet

- A Rahnerian Theological Response To A Secular AgeDocument22 pagesA Rahnerian Theological Response To A Secular AgeLuis FelipeNo ratings yet

- In David Bentley HartDocument6 pagesIn David Bentley HarthenriqueNo ratings yet

- Christology of The MysticsDocument19 pagesChristology of The MysticssdpodmoreNo ratings yet

- Master Eckhart and The Rhineland Mystics by Jeanne Ancelet-Hustache Hilda Graef-Rev. PolitellaDocument3 pagesMaster Eckhart and The Rhineland Mystics by Jeanne Ancelet-Hustache Hilda Graef-Rev. PolitellaHajar Almahdaly100% (1)

- Ne Am Tube HR Archae Us 2003Document6 pagesNe Am Tube HR Archae Us 2003CAStmNo ratings yet

- The Idea of Tradition in the Late Modern World: An Ecumenical and Interreligious ConversationFrom EverandThe Idea of Tradition in the Late Modern World: An Ecumenical and Interreligious ConversationNo ratings yet

- The Bible, Tradition, The Sacraments: Sources of Authority in The Church by Elizabeth Behr-SigelDocument7 pagesThe Bible, Tradition, The Sacraments: Sources of Authority in The Church by Elizabeth Behr-SigelstjeromesNo ratings yet

- The Scandal of The GospelsDocument4 pagesThe Scandal of The GospelsstjeromesNo ratings yet

- AAABooks4me Next List.Document1 pageAAABooks4me Next List.stjeromesNo ratings yet

- Faith Magazine (Catholic Journal)Document32 pagesFaith Magazine (Catholic Journal)stjeromesNo ratings yet

- Cistercian Studies Articles To GetDocument4 pagesCistercian Studies Articles To GetstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Theological Method and The Magisterium of The ChurchDocument9 pagesTheological Method and The Magisterium of The ChurchstjeromesNo ratings yet

- John Thornhill Christopher Dawson PDFDocument51 pagesJohn Thornhill Christopher Dawson PDFmika2k01No ratings yet

- The Tridentine Genius of Vatican IIDocument11 pagesThe Tridentine Genius of Vatican IIstjeromesNo ratings yet

- PneumatologyDocument13 pagesPneumatologycdcrossroaderNo ratings yet

- SchmemannDocument23 pagesSchmemannstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Judgement and Purgatory by John McDade, SJDocument3 pagesJudgement and Purgatory by John McDade, SJstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Risen LordDocument10 pagesRisen LordstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Is The Bible Valued by Catholics?Document7 pagesIs The Bible Valued by Catholics?stjeromesNo ratings yet

- Verbum DominiDocument11 pagesVerbum DoministjeromesNo ratings yet

- Declan MarmionDocument20 pagesDeclan MarmionstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Thornhill - DawsonDocument18 pagesThornhill - DawsonstjeromesNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Christopher Dawson's Concept of History: Chapter Three - The World Religions Bring A New Order of CivilizationsDocument20 pagesAn Introduction To Christopher Dawson's Concept of History: Chapter Three - The World Religions Bring A New Order of CivilizationsstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Yves Congar: Apostle of Patience: Robert Nugent SDSDocument8 pagesYves Congar: Apostle of Patience: Robert Nugent SDSstjeromesNo ratings yet

- One Theologian's Personal Journey: John ThornhillDocument13 pagesOne Theologian's Personal Journey: John ThornhillstjeromesNo ratings yet

- John Thornhill: Theologian of The Church: Gerard Hall SMDocument5 pagesJohn Thornhill: Theologian of The Church: Gerard Hall SMstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Brian JohnstoneDocument22 pagesBrian JohnstonestjeromesNo ratings yet

- HemoptysisDocument30 pagesHemoptysisTAUFIK RAMADHAN BIYANo ratings yet

- Literature Activity 1Document2 pagesLiterature Activity 1Elisha Grace JadormeoNo ratings yet

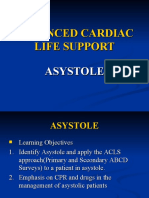

- Advanced Cardiac Life Support AsystoleDocument14 pagesAdvanced Cardiac Life Support AsystoleKar TwentyfiveNo ratings yet

- Robert S. Arthur Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California Jolla, CaliformaDocument6 pagesRobert S. Arthur Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California Jolla, CaliformaLaurenz Luigi CruzNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Project Scheduling Lagging, Crashing and Activity NetworksDocument26 pagesChapter 6 Project Scheduling Lagging, Crashing and Activity NetworksMỹ Mộc LinhNo ratings yet

- Small-Angle Scattering: A View On The Properties, Structures and Structural Changes of Biological Macromolecules in SolutionDocument81 pagesSmall-Angle Scattering: A View On The Properties, Structures and Structural Changes of Biological Macromolecules in SolutiondibudkNo ratings yet

- Camo Paint ManualDocument182 pagesCamo Paint Manualwhsprz100% (1)

- Total Equivalength Length For Pipes - Valves - FittingsDocument6 pagesTotal Equivalength Length For Pipes - Valves - Fittingsvanchai sapaNo ratings yet

- Handling Unit Management in SAP Packing During Outbound ProcessDocument48 pagesHandling Unit Management in SAP Packing During Outbound ProcessmohannaiduramNo ratings yet

- Government Engineering College Dahod: Dadhichi HostelDocument5 pagesGovernment Engineering College Dahod: Dadhichi HostelSandip MouryaNo ratings yet

- Specifications Dimension: (Unit: MM) 55SVH7EDocument1 pageSpecifications Dimension: (Unit: MM) 55SVH7Edervis quinteroNo ratings yet

- AN1671 MC145170 PSpice Modeling KitDocument14 pagesAN1671 MC145170 PSpice Modeling KitfahkingmoronNo ratings yet

- 00 Table of Contents NMDocument9 pages00 Table of Contents NMJohn Bofarull GuixNo ratings yet

- Bloom Ks2-Maths-Blooms-Taxonomy-Meet-The-Bloom-Superheroes-Desk-Mat - Ver - 3Document1 pageBloom Ks2-Maths-Blooms-Taxonomy-Meet-The-Bloom-Superheroes-Desk-Mat - Ver - 3hongbongNo ratings yet

- TST2601 - Minor Test 1 - Memo - 2022Document8 pagesTST2601 - Minor Test 1 - Memo - 2022Johan PienaarNo ratings yet

- Lendell - Engine CatalogueDocument27 pagesLendell - Engine CatalogueRommel Orozco CastellónNo ratings yet

- Specifications: Shenzhen Sunlord Electronics Co., LTDDocument38 pagesSpecifications: Shenzhen Sunlord Electronics Co., LTDdabajiNo ratings yet

- An Essay On Islamic SchoolsDocument3 pagesAn Essay On Islamic Schoolsibnajami100% (1)

- Barcoo Independent 230410Document8 pagesBarcoo Independent 230410barcooindependentNo ratings yet

- OM ParticipantGuideDocument52 pagesOM ParticipantGuideGrace RuthNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Interest Examples and Actions GuidelineDocument3 pagesConflict of Interest Examples and Actions GuidelineAsadullah Abbas100% (1)

- PDFDocument250 pagesPDFMarvellousNo ratings yet

- Bending StressDocument9 pagesBending StressUjjal Kalita 19355No ratings yet

- C S E T: Test GuideDocument16 pagesC S E T: Test GuideShantamNo ratings yet

- ET 03 MixerDocument50 pagesET 03 Mixer091066No ratings yet

- Product and Company Identification: Safety Data SheetDocument6 pagesProduct and Company Identification: Safety Data SheetNikolay ZhelunicinNo ratings yet

- LearnEnglish Listening B1 Meeting An Old FriendDocument4 pagesLearnEnglish Listening B1 Meeting An Old FriendTr RoseNo ratings yet

- Greaves Cotton Ar 2018 1 PDFDocument168 pagesGreaves Cotton Ar 2018 1 PDFanand_parchureNo ratings yet

Inspiration and Incarnation: Denis Farkasfalvy

Inspiration and Incarnation: Denis Farkasfalvy

Uploaded by

stjeromesOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Inspiration and Incarnation: Denis Farkasfalvy

Inspiration and Incarnation: Denis Farkasfalvy

Uploaded by

stjeromesCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Denis Farkasfalvy

Inspiration and Incarnation

At a relatively early point in time Christian theological reflection about the Scripture noticed an analogy between incarnation and inspiration. While the concept of incarnation, closely following the Johannine terminology of Jn 1:14, early received the technical name of sa,rkwsij, for the concept of biblical inspiration it has taken centuries several centuries to be embedded into a technical or at least quasi technical vocabulary Yet beginning in patristic times, an increasing number of thinkers perceived the parallelisms between the flesh in which Gods Word dwelt and the letter which, in a similar way, veiled and revealed, manifested but also transmitted in an appropriately human way what God meant to express in the human beings oral or written instruments of communication. In this essay we will attempt, in the form of a brief survey, main aspects of the analogy of inspiration and inspiration in the hope of providing a new vantage point from which the theology of inspiration may be re-examined.

1.

The History of this Analogy before Vatican II

Analogies between Incarnation and inspiration have been found in Christian antiquity; Luis Alonso Schkel quotes some examples in his book The Inspired Word. 1 Before him, Henri de Lubac pointed out the importance of the analogy in the works of Origen. His book on Origen, Histoire et Esprit, contains a long chapter under the title Les incorporations du Logos in the Scriptures.2 As a man sensitive to ensure the precision of nuances, de Lubac cautiously chose his terminology. For this context he avoided the word incarnation, because in Catholic theology incarnation cannot be put in plural. More importantly, what is scriptures, which is, therefore, both derived from and analogous to the Incarnation. incorporated into the Scriptures as Gods word is a divine message about Christ, not his divine nature subsisting in the person of the Son. But de Lubac closely imitates Origen and imitates his manner of speaking about a certain corporeal dimension which Gods word obtains in the Hugo Rahner, the brother of Karl Rahner and a Jesuit and patristic scholar like de Lubac, began to study Origens theology of Scripture at about the same time de Lubac was. In 1947, he published an article in which he coined the term Schriftwerdung, a word that seems to be made in imitation of the German word Menschwerdung, signifying the Incarnation:3 A short time

1

In The Inspired Word (New York: Herder), 49, quotes St. Hippolytus, who wrote that the same Word was made visible and audible (Contra Noetum 12: PG 10, 820). He also quotes John Chrysostoms famous passage about divine condescension (Hom. in Gen 3:8 no 17, 1; PG 53, 134). The rest of the references about the analogy between Incarnation and inspiration come from medieval authors. 2 Henri de Lubac, Histoire et Esprit. Lintelligence de lcriture daprs Origne. Paris: Aubier: 1950. An English translation appeared only fifty-eight years later: History and Spirit: The Understanding of Scripture according to Origen, translated by A. E. Nash. San Francisco: Ignatius, 2008. 3 Hugo Rahner,Das Menschenbild des Origenes: Eranos-Jahrbuch XV (1947) 197-248.

later in 1958, Karl Rahner published a short but eventually very influential book with the title Inspiration in the Bible, which includes several remarks about this analogy between incarnation in the flesh and becoming human word.4 However, Karl Rahner did not use the term Schriftwerdung, but does employ the concept of an analogy between inspiration and Incarnation throughout his book when referring to the genesis or the coming about (Entstehung) of Scripture, a process similar to the Menschwerdung (God becoming man). Another genius, the Swiss Jesuit Hans Urs von Balthasar, who was a friend to both de Lubac and the Rahner brothers (as well as a student of Origen), also began to use Origens analogy of Incarnation and inspiration on some brilliant meditative pages, where he compared the Word made Flesh with the word becoming Scripture.5 A few years later, when the first outline of a document about Scripture and Tradition was presented to the Second Vatican Council under the title De fontibus revelationis, this new outlook was missing from the Preparatory Commissions text. As we know, the narrow, neothomistic schema failed to obtain enough support, and after stormy sessions was taken off the councils agenda, thanks to a personal intervention by Pope John XXIII.. Only two years later, following the appointment of a new commission, did this outlook make a come-back in a new document, under a new title and within a new perspective. The new text eventually became the Apostolic Constitution Dei Verbum, the first conciliar document ever written in which the patristic analogy between Incarnation and inspiration appears.

2.

Incarnation and Inspiration in Dei Verbum

Dei Verbum consists of six chapters. As its title reveals, it treats Divine Revelation and its transmission. Therefore, biblical inspiration and interpretation are included in it but only in a secondary and sketchy way. The first two chapters deal with Revelation as the process of Gods self-disclosure offered to man to accept it in faith and then hand it over to his fellowmen. It is in such a context that Scripture and Tradition are first mentioned in the second chapter (#10). Then, in chapter III, the document lays down in broad outline the theology of inspiration, with explicit references to previous statements of the Magisterium on the matter.6 In paragraph # 13, the analogy between Incarnation and inspiration is explicitly stated. Of course, we find no reference here to previous magisterial documents, giving the impression that the analogy of Inspiration and incarnation has never been previously mentioned by any papal statement. The text reads: [For] the words of God, expressed in human language, have been made like human discourse, just as the Word of the Eternal Father, when he took to himself the weakness of the human flesh, was in every way made like men. 7

4

Karl Rahner, ber die Schriftinspiration (Freiburg: Herder, 1958), 22, note # 5. Verbum Caro, Skizzen Zur Theologie (Einsiedeln: Johannes Verlag), 12-27. 6 10-12 are heavily footnoted, with references to the Council of Trent, Providentissimus Deus by Pope Leo XIII, Divino afflante by Pius XII, and Spiritus Paraclitus by Benedict XV. 7 Although no footnote indicates it, this is nothing but a rectified version of Divino afflante Spiritu by Pius XII, in which the analogy between Scripture and Gods Incarnate Word appears in the following way: Sicut enim substantiale Dei Verbum hominibus simile factum est quoad omnia absque peccato (Hebr 5:12), ita etiam Dei verba humanis expressa quoad omnia humano

5

After that, the analogy with the Incarnation does not completely disappear. When both subsequent chapters (chapter IV about the Old Testament and Chapter V about the New Testament) begin with the term the Word of God, the document harks back to the Word of the Eternal Father (cf. #11) proceeding from the Father, an expression that seems to evoke the Incarnation. More significant is the parallelism which the opening lines of chapter VI, the last chapter of Dei Verbum, make between the Eucharistic and the Scriptural word. They speak about transmitting Gods life-giving nourishment to the faithful from the double table of word and sacrament, with an obvious parallelism between verbal and sacramental signs as means by which Gods selfdisclosure and self-giving are continually offered to mankind . Through the Eucharist, the parallelism with the Incarnation is again rather obvious.

3.

Implications for a New Theology of Inspiration

The way I see it, , the theology of inspiration collapsed after Vatican II due to various causes, such as neglect and reigning ignorance on the topic. One must also say that the neoscholastic framework, in which Inspiration and inerrancy were treated, lost its credibility, so that textbooks like those of Bea, Tromp, Hpfl-Gut-Metzinger-Leloir 8 etc. became unteachable, but without any replacement in sight.9 The issues about the hagiographers and the double authorship of scripture, one divine and one human, lost their Thomistic speculative context, because Thomistic epistemology was losing ground. Already at the Council it became clear that, due to the lack of monographic studies about the patristic and medieval teaching of inspiration, there was little knowledge about what tradition really said about these matters. Perhaps more correctly, the majority of biblical scholars had little or no esteem for much of what ancient and medieval tradition taught about the allegorical and spiritual senses of scripture and, therefore, remained convinced that there was little to be gained from these sources. Most people knew that substantial challenges were made to the traditional scholastic treatise about inspiration by Karl Rahners book, a tiny volume of 83 pages. He called for a complete re-thinking of the doctrine of inspiration, but besides The Inspired Word by Luis

sermoni assimilia facta sunt excepto errore It seems that the commission wanted to leave out the topic of inerrancy and therefore suppressed any reference to the text of Divino afflante. One must also notice that in this same paragraph, Divino afflante quotes the term condescension in both Latin and Greek with a reference to John Chrysostom (cf. above note 1), which Dei Verbum takes over without referring to the document of Pius XII. 8 This was the last edition of the Introductio Generalis in Sacram Scripturam, updated decade after decade by Benedictine professors succeeding each other which reigned for over half a century in the Pontifical School of theology at SantAnselmo in Rome. 9 The story is a bit more complicated. By the early 1960s in almost every program inspiration and inerrancy became part of Fundamental theology, a subject in transition so that what was previously taught General Introduction to Sacred Scripture became fragmented and often left uncovered.

Alonso Schkel and a few critical pages by Yves Congar, nothing of significance happened in response. 4. The Outline of a Theology of Inspiration in an Incarnational Perspective

Before a question in Catholic theology is re-shaped and renewed, however, one must assess and recover what tradition has achieved and preserved. This task is not as huge today as it was forty years ago, because the history of exegesis has been successfully studied and, as a collateral benefit, we have begun to understand a little better what our tradition has taught about inspiration. The most beneficial contribution comes from Dei Verbum, which inserts the question of inspiration into the general topic of the transmission of revelation in the context of salvation history. It thereby saves inspiration from the narrow confines of an interaction between God and man as co-authors of literary products, books that contain Gods word without error. In other words, Sacred Scripture begins to be regarded as the product of one single sacred history which brought about the coming of Christ at its peak, with the people of Israel in its first phase and the Church in its second phase as the recipients of Revelation. While walking down this path, we come to the realization that the Word becoming flesh and the Word becoming Tradition and Scripture are part of one single process of Gods coming into the world for the sake of our salvation. We are now at the point where we can make some helpful distinctions in order to create adequate conceptual tools for outlining a theology of inspiration, or even, we might say, a theology of the Bible. A first distinction is very important although rarely made. Biblical inspiration can be studied from two sides: an objective side treating the inspired books, and a subjective side treating the biblical authors or hagiographers. The distinction of these two aspects makes it possible to examine separately both the tradition and the doctrinal issues about inspired authors and the inspired books. The inspired authors are recipients of charismas which they receive as mediators of Gods word. Their role is analogous to that of the patriarchs, Moses and his successors, and other prophetic figures, including the prophets whose names mark various books of the Old Testament. In the New Testament, the mediators of Gods new word of Revelation are the apostles and their collaborators, whom the early church calls viri apostolici, apostolic men. In both Testaments the mediators of the word take the place of the earthly Christ and extend the mediation of Christ now in glory. thus these mediators of the word are truly instruments of transmission, but Christ remains Gods full and fully authentic self-disclosure. As the prophetic leaders anticipate, the apostolic leaders extend the supreme office and role of Christ, the only mediator between God and man. This whole structure of transmitters of the divine word must be seen as emanating from and distributing the one Word of the Father. The fact that some of these figures transmitted the prophetic or the apostolic message orally and some did in writing is an important distinction, but remains of a secondary importance. The word of God addresses man viva voce, forms a community, and functions in a role of establishing and maintaining remembrance. Both in its written and oral form Gods word, transmitted in human words, provides lasting instruments by

which the word that constitutes the community of Gods People may enable that People to hear the word in its original force and authenticity. The outline laid out here posits intimate connection between Scripture and tradition. Usually oral tradition precedes Scripture, but tradition also keeps the Scriptures secure, welldefined and stabilized. Tradition also serves as the live interpretive framework of Gods word, while the written texts offer more objective standards of authenticity, precision, solid verbal expression and accurately focused memory. What I have described so far is only one dimension of the genesis of Scripture, a dimension that we can call historical or temporal. In this process, God reveals, while man listens, believes, accepts, responds, remembers and, for the sake of future generations, transmits both memory and text. The one and same God, who initiates Revelation by offering Himself to mankind, keep this very process in motion. He accompanies his word so that it might be retained, remembered and passed on. Biblical inspiration is the grace that accompanies Gods word, all the way up to its written consolidation in the finalized and canonized form of Scripture. There is, however a second dimension. The written word which comes about in the course of this process is the sacred text; it can be called an inspired text. The sacred text enshrines and solidifies what God has told the human creature in the process of salvation history, and can be accessed as such by new generations. Scripture contains a blueprint of Gods dealings with man so that it becomes a map for mans journey to God. The objective aspect of inspiration is a specific quality of the text. The inspired text resembles all human literary productions, insofar as it also represents in some objective and solidified terms human states of consciousness in written form. But the sacred text is not merely a human product. At its greatest depth, it makes Gods word accessible in audible-legible form; it provides for the on-going availability of Gods self-disclosure for any human being who can read and/or understand the particular human idiom. It brings God, in search of man, to potentially every human being who seeks God in faith.

5.

Further clarifications

The relationship between Incarnation and inspiration is manifold.

First, there is a cause-effect relationship. The economy of salvation aims at or derives from the Incarnation of the Son. Scripture is part of the scaffolding on which the Incarnation, the Sons hypostatic union, is set in both its pre-resurrection and resurrected state. The Incarnate and glorified Word is the fulfillment of all other words. This creates a specific reference system of all parts of Scripture to Jesus born, crucified and glorified. Second, there is an analogy between the Incarnate Word and the word of God presented in the Holy Scriptures. Their structures resemble each other insofar as in both the human elements is linked by its instrumental role and by its function of briunging to the realm of sense perception what is beyond the senses., Both are approached by the senses, specifically the eyes and ears. Both need the application of human tools of communication. Both must be explored by fides quaerens intellectum. On the surface the Word Incarnate may create disappointment or scandal; at its depth He offers a revelatory encounter with God on all levels of human existence: physical,

intellectual, emotional, moral and ontological. The various senses of Scripture in ancient and medieval exegesis examine these various yet connected levels. Third, divine condescension is involved in both. This term does not only signify God stooping to man so that mans slow intellect or unyielding selfishness may be overcome. When offering his word in permanently deposited, written form, God allows man to approach him according to the needs of human nature. In the Incarnation, Gods condescension makes possible what was first impossible even to Moses: fellowship with God. Now man begins to converse with God as a man converses with a fellow human being. (Ex 33:11, ). Regardless of the kind of vision which Moses was given, only in Jesus earthly life can mortal flesh possibly carry a full divine personal presence. But, of course, the mortal body of a human nature handicaps the fullness of revelation. Far from simply revealing the Deity, it both veils and hides the Deity. When Jesus is raised, he appears to his apostles and transmits both the gift of the Holy Spirit and the gift of the Scriptures, explaining the meaning of both to the apostles. Three gifts constitute the Church: 1. the presence of Jesus risen humanity in the Eucharist,10 2. the gift of the Holy Spirit, and 3. the meaning of the Scriptures, which the apostolic church takes into its possession while depositing its understanding of Christ in the writings of the New Testament. Rather than to attempt to write a concluding paragraph for an essay that was meant to remain sketchy and incomplete, I provide here as a reminder a rather lengthy passage from the gospel of Luke wwhich, in the framework of the divine word, authentically condenses all that can be said summarily about inspiration and incarnation and the further relationships which they invoke. While they were talking about this, Jesus himself stood among them and said to them, "Peace be with you." They were startled and terrified, and thought that they were seeing a ghost. He said to them, "Why are you frightened, and why do doubts arise in your hearts? Look at my hands and my feet; see that it is I myself. Touch me and see; for a ghost does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have." And when he had said this, he showed them his hands and his feet. While in their joy they were disbelieving and still wondering, he said to them, "Have you anything here to eat?" They gave him a piece of broiled fish, and he took it and ate in their presence. Then he said to them, "These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you-- that everything written about me in the law of Moses, the prophets, and the psalms must be fulfilled." Then he opened their minds to understand the scriptures, and he said to them, "Thus it is written, that the Messiah is to suffer and to rise from the dead on the third day, and that repentance and forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses of these things. And see, I am sending upon you what my Father promised; so stay here in the city until you have been clothed with power from on high." (Luke 24:36-49)

10

Of course, I subsume to this point the whole sacramental order and the liturgical life of the Church.

My last comment spells out a tall task. The incarnational context of inspiration offers to the theology of inspiration a new chance for what Karl Rahner asked for in 1958: a complete overhaul of the concept, in order to re-think, re-develop, and re-possess it for the sake of renewing biblical theology.11

He proposed that the concept of Inspiration be thought through anew (den Begriff der Inspiration neu zu durchdenken), op. cit. p. 16.

11

You might also like

- A2 UNIT 4 Test Answer Key HigherDocument2 pagesA2 UNIT 4 Test Answer Key HigherMaxi Comas60% (5)

- (Extract) (Nicholas Lombardo) LogicDesireDocument15 pages(Extract) (Nicholas Lombardo) LogicDesireJtavidNo ratings yet

- Anne HuntDocument13 pagesAnne HuntstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Fides Et Ratio NotesDocument2 pagesFides Et Ratio NotesBrittanyNo ratings yet

- Does Suffering Make SenseDocument74 pagesDoes Suffering Make SensejonicdaoNo ratings yet

- Being and Hayah - ARIGA TetsutaroDocument22 pagesBeing and Hayah - ARIGA Tetsutarorio rio rioNo ratings yet

- Bonaventure Journey of The Mind Into GodDocument31 pagesBonaventure Journey of The Mind Into GodJelena StankovićNo ratings yet

- Testimony of SimplicityDocument14 pagesTestimony of Simplicitybbishop2059No ratings yet

- 4-1 06 Lahav - Quest For WisdomDocument14 pages4-1 06 Lahav - Quest For WisdomarabelmNo ratings yet

- Theravada Methods of Intepretation On Buddhist ScripturesDocument44 pagesTheravada Methods of Intepretation On Buddhist ScripturesHueBaoNo ratings yet

- Moral Market Freer Market - John MilbankDocument7 pagesMoral Market Freer Market - John MilbankJoel Arthur EatonNo ratings yet

- The Legacy of Yves RaguinDocument9 pagesThe Legacy of Yves RaguinstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Olivier Clement and Paul EvdokimovDocument16 pagesOlivier Clement and Paul Evdokimovstjeromes100% (2)

- Tafe NSW: Knowledge AssessmentDocument30 pagesTafe NSW: Knowledge AssessmentDibyendu Karmakar100% (3)

- Aquinas, Science, and Human Uniqueness: An Integrated Approach to the Question of What Makes Us HumanFrom EverandAquinas, Science, and Human Uniqueness: An Integrated Approach to the Question of What Makes Us HumanNo ratings yet

- Sarda y Salvany Félix - Liberalism Is A SinDocument94 pagesSarda y Salvany Félix - Liberalism Is A SinMihai IgneaNo ratings yet

- Augustine and Plato Correlation of WorksDocument4 pagesAugustine and Plato Correlation of Worksstudub26No ratings yet

- Why I Do Not Attend Case Conferences P MeehlDocument11 pagesWhy I Do Not Attend Case Conferences P MeehlIgnacio J. Sandino Pérez100% (1)

- Lecturer Rev. Dr. David K. Mbugua Description:: Fundamental Moral Theology OneDocument3 pagesLecturer Rev. Dr. David K. Mbugua Description:: Fundamental Moral Theology OneKIZITO BONNo ratings yet

- Ethics as a Work of Charity: Thomas Aquinas and Pagan VirtueFrom EverandEthics as a Work of Charity: Thomas Aquinas and Pagan VirtueNo ratings yet

- Infallibility and ContraceptionDocument10 pagesInfallibility and ContraceptionPaul Horrigan100% (1)

- Fides Et Ratio As The Perpetual Journey of Faith and ReasonDocument23 pagesFides Et Ratio As The Perpetual Journey of Faith and ReasonClarensia AdindaNo ratings yet

- Jesus and The Son of ManDocument10 pagesJesus and The Son of ManRezart BekaNo ratings yet

- Excursus On Fear of The LordDocument3 pagesExcursus On Fear of The LordMaria Mercedes GuaitaNo ratings yet

- Dei Filius and The Fides Et Ratio ProblemDocument15 pagesDei Filius and The Fides Et Ratio Problemrog1rio1tadeu1mesquiNo ratings yet

- Radical Orthodoxy & Christian Psychology, Milbank & OliverDocument24 pagesRadical Orthodoxy & Christian Psychology, Milbank & OliveriamrabbitholeNo ratings yet

- Theological Mysteries In Scientific PerspectiveFrom EverandTheological Mysteries In Scientific PerspectiveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Psychological PrayerDocument5 pagesPsychological PrayerAdeniran VictorNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology of ReligionDocument5 pagesPhenomenology of ReligionJaimon ThadathilNo ratings yet

- Reidblackman ChurchlandDocument8 pagesReidblackman ChurchlandYisroel HoffmanNo ratings yet

- Elisabeth of Schönau & Women's SpiritualityDocument15 pagesElisabeth of Schönau & Women's SpiritualityPedroNo ratings yet

- ! - Bloor, Joshua - New Directions in Western Soteriology - Theology, May 2015, Vol 118 Iss 3Document9 pages! - Bloor, Joshua - New Directions in Western Soteriology - Theology, May 2015, Vol 118 Iss 3YuriNo ratings yet

- Aphraates The SageDocument2 pagesAphraates The SageDarry BlanciaNo ratings yet

- Plunged into the Trinity: Our Sacramental Becoming: Essays in Sacramental EcclesiologyFrom EverandPlunged into the Trinity: Our Sacramental Becoming: Essays in Sacramental EcclesiologyNo ratings yet

- Recognizing the Gift: Toward a Renewed Theology of Nature and GraceFrom EverandRecognizing the Gift: Toward a Renewed Theology of Nature and GraceNo ratings yet

- Kreeft4 Nature GodDocument18 pagesKreeft4 Nature GodrichardNo ratings yet

- Agape and Bhakti with Bataille and Mark at Loyola and St. Francis: The Mysticism of ReconciliationFrom EverandAgape and Bhakti with Bataille and Mark at Loyola and St. Francis: The Mysticism of ReconciliationNo ratings yet

- 4800ADTE040 de NovissimisDocument62 pages4800ADTE040 de NovissimisThomist AquinasNo ratings yet

- Alan Jones's Reimagining Christianity Back To RomeDocument9 pagesAlan Jones's Reimagining Christianity Back To RomeServant Of TruthNo ratings yet

- A Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyFrom EverandA Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyNo ratings yet

- Against Inclusiveness: How the Diversity Regime is Flattening America and the West and What to Do About ItFrom EverandAgainst Inclusiveness: How the Diversity Regime is Flattening America and the West and What to Do About ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- The Tridentine Genius of Vatican IIDocument11 pagesThe Tridentine Genius of Vatican IIstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Descartes Locke 1 PDFDocument36 pagesDescartes Locke 1 PDFRenefe RoseNo ratings yet

- Blanchette Aquinas' Conception of The Great Chain of Being A More Considered Reply To LovejoyDocument2 pagesBlanchette Aquinas' Conception of The Great Chain of Being A More Considered Reply To LovejoymartinezruizcmNo ratings yet

- God Needs Salvation: A New Vision of God for the Twenty First CenturyFrom EverandGod Needs Salvation: A New Vision of God for the Twenty First CenturyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 11 LemeniDocument13 pages11 LemeniMirceaNo ratings yet

- John Milbank S Theological Ontology of GiftDocument110 pagesJohn Milbank S Theological Ontology of GiftМикола ОсипенкоNo ratings yet

- A Rahnerian Theological Response To A Secular AgeDocument22 pagesA Rahnerian Theological Response To A Secular AgeLuis FelipeNo ratings yet

- In David Bentley HartDocument6 pagesIn David Bentley HarthenriqueNo ratings yet

- Christology of The MysticsDocument19 pagesChristology of The MysticssdpodmoreNo ratings yet

- Master Eckhart and The Rhineland Mystics by Jeanne Ancelet-Hustache Hilda Graef-Rev. PolitellaDocument3 pagesMaster Eckhart and The Rhineland Mystics by Jeanne Ancelet-Hustache Hilda Graef-Rev. PolitellaHajar Almahdaly100% (1)

- Ne Am Tube HR Archae Us 2003Document6 pagesNe Am Tube HR Archae Us 2003CAStmNo ratings yet

- The Idea of Tradition in the Late Modern World: An Ecumenical and Interreligious ConversationFrom EverandThe Idea of Tradition in the Late Modern World: An Ecumenical and Interreligious ConversationNo ratings yet

- The Bible, Tradition, The Sacraments: Sources of Authority in The Church by Elizabeth Behr-SigelDocument7 pagesThe Bible, Tradition, The Sacraments: Sources of Authority in The Church by Elizabeth Behr-SigelstjeromesNo ratings yet

- The Scandal of The GospelsDocument4 pagesThe Scandal of The GospelsstjeromesNo ratings yet

- AAABooks4me Next List.Document1 pageAAABooks4me Next List.stjeromesNo ratings yet

- Faith Magazine (Catholic Journal)Document32 pagesFaith Magazine (Catholic Journal)stjeromesNo ratings yet

- Cistercian Studies Articles To GetDocument4 pagesCistercian Studies Articles To GetstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Theological Method and The Magisterium of The ChurchDocument9 pagesTheological Method and The Magisterium of The ChurchstjeromesNo ratings yet

- John Thornhill Christopher Dawson PDFDocument51 pagesJohn Thornhill Christopher Dawson PDFmika2k01No ratings yet

- The Tridentine Genius of Vatican IIDocument11 pagesThe Tridentine Genius of Vatican IIstjeromesNo ratings yet

- PneumatologyDocument13 pagesPneumatologycdcrossroaderNo ratings yet

- SchmemannDocument23 pagesSchmemannstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Judgement and Purgatory by John McDade, SJDocument3 pagesJudgement and Purgatory by John McDade, SJstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Risen LordDocument10 pagesRisen LordstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Is The Bible Valued by Catholics?Document7 pagesIs The Bible Valued by Catholics?stjeromesNo ratings yet

- Verbum DominiDocument11 pagesVerbum DoministjeromesNo ratings yet

- Declan MarmionDocument20 pagesDeclan MarmionstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Thornhill - DawsonDocument18 pagesThornhill - DawsonstjeromesNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Christopher Dawson's Concept of History: Chapter Three - The World Religions Bring A New Order of CivilizationsDocument20 pagesAn Introduction To Christopher Dawson's Concept of History: Chapter Three - The World Religions Bring A New Order of CivilizationsstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Yves Congar: Apostle of Patience: Robert Nugent SDSDocument8 pagesYves Congar: Apostle of Patience: Robert Nugent SDSstjeromesNo ratings yet

- One Theologian's Personal Journey: John ThornhillDocument13 pagesOne Theologian's Personal Journey: John ThornhillstjeromesNo ratings yet

- John Thornhill: Theologian of The Church: Gerard Hall SMDocument5 pagesJohn Thornhill: Theologian of The Church: Gerard Hall SMstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Brian JohnstoneDocument22 pagesBrian JohnstonestjeromesNo ratings yet

- HemoptysisDocument30 pagesHemoptysisTAUFIK RAMADHAN BIYANo ratings yet

- Literature Activity 1Document2 pagesLiterature Activity 1Elisha Grace JadormeoNo ratings yet

- Advanced Cardiac Life Support AsystoleDocument14 pagesAdvanced Cardiac Life Support AsystoleKar TwentyfiveNo ratings yet

- Robert S. Arthur Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California Jolla, CaliformaDocument6 pagesRobert S. Arthur Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California Jolla, CaliformaLaurenz Luigi CruzNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Project Scheduling Lagging, Crashing and Activity NetworksDocument26 pagesChapter 6 Project Scheduling Lagging, Crashing and Activity NetworksMỹ Mộc LinhNo ratings yet

- Small-Angle Scattering: A View On The Properties, Structures and Structural Changes of Biological Macromolecules in SolutionDocument81 pagesSmall-Angle Scattering: A View On The Properties, Structures and Structural Changes of Biological Macromolecules in SolutiondibudkNo ratings yet

- Camo Paint ManualDocument182 pagesCamo Paint Manualwhsprz100% (1)

- Total Equivalength Length For Pipes - Valves - FittingsDocument6 pagesTotal Equivalength Length For Pipes - Valves - Fittingsvanchai sapaNo ratings yet

- Handling Unit Management in SAP Packing During Outbound ProcessDocument48 pagesHandling Unit Management in SAP Packing During Outbound ProcessmohannaiduramNo ratings yet

- Government Engineering College Dahod: Dadhichi HostelDocument5 pagesGovernment Engineering College Dahod: Dadhichi HostelSandip MouryaNo ratings yet

- Specifications Dimension: (Unit: MM) 55SVH7EDocument1 pageSpecifications Dimension: (Unit: MM) 55SVH7Edervis quinteroNo ratings yet

- AN1671 MC145170 PSpice Modeling KitDocument14 pagesAN1671 MC145170 PSpice Modeling KitfahkingmoronNo ratings yet

- 00 Table of Contents NMDocument9 pages00 Table of Contents NMJohn Bofarull GuixNo ratings yet

- Bloom Ks2-Maths-Blooms-Taxonomy-Meet-The-Bloom-Superheroes-Desk-Mat - Ver - 3Document1 pageBloom Ks2-Maths-Blooms-Taxonomy-Meet-The-Bloom-Superheroes-Desk-Mat - Ver - 3hongbongNo ratings yet

- TST2601 - Minor Test 1 - Memo - 2022Document8 pagesTST2601 - Minor Test 1 - Memo - 2022Johan PienaarNo ratings yet

- Lendell - Engine CatalogueDocument27 pagesLendell - Engine CatalogueRommel Orozco CastellónNo ratings yet

- Specifications: Shenzhen Sunlord Electronics Co., LTDDocument38 pagesSpecifications: Shenzhen Sunlord Electronics Co., LTDdabajiNo ratings yet

- An Essay On Islamic SchoolsDocument3 pagesAn Essay On Islamic Schoolsibnajami100% (1)

- Barcoo Independent 230410Document8 pagesBarcoo Independent 230410barcooindependentNo ratings yet

- OM ParticipantGuideDocument52 pagesOM ParticipantGuideGrace RuthNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Interest Examples and Actions GuidelineDocument3 pagesConflict of Interest Examples and Actions GuidelineAsadullah Abbas100% (1)

- PDFDocument250 pagesPDFMarvellousNo ratings yet

- Bending StressDocument9 pagesBending StressUjjal Kalita 19355No ratings yet

- C S E T: Test GuideDocument16 pagesC S E T: Test GuideShantamNo ratings yet

- ET 03 MixerDocument50 pagesET 03 Mixer091066No ratings yet

- Product and Company Identification: Safety Data SheetDocument6 pagesProduct and Company Identification: Safety Data SheetNikolay ZhelunicinNo ratings yet

- LearnEnglish Listening B1 Meeting An Old FriendDocument4 pagesLearnEnglish Listening B1 Meeting An Old FriendTr RoseNo ratings yet

- Greaves Cotton Ar 2018 1 PDFDocument168 pagesGreaves Cotton Ar 2018 1 PDFanand_parchureNo ratings yet