Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tagawa 1970

Tagawa 1970

Uploaded by

David MartínezCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Luke : 2 Volumes (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From EverandLuke : 2 Volumes (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- 1 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From Everand1 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- 2 Corinthians (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From Everand2 Corinthians (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- New Testament Theology: Magnifying God in ChristFrom EverandNew Testament Theology: Magnifying God in ChristRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Jude and 2 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From EverandJude and 2 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- James (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From EverandJames (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Chapter Five: The Problem Op Sensus PlensorDocument24 pagesChapter Five: The Problem Op Sensus PlensorFreed Nixon0% (1)

- Magnifying God in Christ: A Summary of New Testament TheologyFrom EverandMagnifying God in Christ: A Summary of New Testament TheologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Divine Wrath and Salvation in Matthew: The Narrative World of the First GospelFrom EverandDivine Wrath and Salvation in Matthew: The Narrative World of the First GospelRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- 1 Tim 2.15 - Saved by ChildbirthDocument17 pages1 Tim 2.15 - Saved by Childbirth31songofjoyNo ratings yet

- Gideon Bohak Babylonian Jewish Magic in PDFDocument54 pagesGideon Bohak Babylonian Jewish Magic in PDFskaufmanhucNo ratings yet

- Hebrew LanguageDocument16 pagesHebrew LanguageJay RonssonNo ratings yet

- Law Righteousness and Discipleship in Matthew PDFDocument8 pagesLaw Righteousness and Discipleship in Matthew PDFBillybhNo ratings yet

- Matthews Use OT 1964-1 (Rev. Norman Hillyer)Document15 pagesMatthews Use OT 1964-1 (Rev. Norman Hillyer)Alberto PérezNo ratings yet

- The Roman Catholic Church and Its Recognition of the Validity of Baptism in the Name of Jesus (Acts 2:38) from 100 A.D. to 500 A.D.From EverandThe Roman Catholic Church and Its Recognition of the Validity of Baptism in the Name of Jesus (Acts 2:38) from 100 A.D. to 500 A.D.No ratings yet

- Peterh. Davids, St. Stephens University, St. Stephen, Nbe3L 1T3, CanadaDocument3 pagesPeterh. Davids, St. Stephens University, St. Stephen, Nbe3L 1T3, Canadafarax1720No ratings yet

- Biblical Inerrancy Accroding To RatzingerDocument111 pagesBiblical Inerrancy Accroding To RatzingersssdddkkkNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument35 pagesRetrieverickNo ratings yet

- SKARSAUNE OSKAR Them 199410 Heresy and The Pastoral EpistlesDocument14 pagesSKARSAUNE OSKAR Them 199410 Heresy and The Pastoral Epistlesivory2011100% (1)

- Theology & Res. - Metaphors and ParadigmsDocument19 pagesTheology & Res. - Metaphors and ParadigmsJodie BarryNo ratings yet

- New Dictionary of Theology: The EditorDocument4 pagesNew Dictionary of Theology: The EditorAkhoiNo ratings yet

- John P. Meier (1977) - Two Disputed Questions in Matt 28.16-20. Journal of Biblical Literature 96.3, Pp. 407-424Document19 pagesJohn P. Meier (1977) - Two Disputed Questions in Matt 28.16-20. Journal of Biblical Literature 96.3, Pp. 407-424Olestar 2023-06-22No ratings yet

- Barth 01Document16 pagesBarth 01Gabriel LopezNo ratings yet

- Grant Osborne Hermeneutics and Women in The ChurchDocument17 pagesGrant Osborne Hermeneutics and Women in The Churchhasiholannbbn03No ratings yet

- No They Are Not Crazy A Look at Prophecy PDFDocument18 pagesNo They Are Not Crazy A Look at Prophecy PDFBorisNo ratings yet

- The Curious Case of The Analogia EntisDocument16 pagesThe Curious Case of The Analogia EntisakimelNo ratings yet

- Eson Gumban - Matthew 16Document26 pagesEson Gumban - Matthew 16Gear John TigerNo ratings yet

- The Mystery of The Kingdom of GodDocument19 pagesThe Mystery of The Kingdom of GodDavide Varchetta100% (1)

- Revelation and Violence, A Study in Contextualization - Walter Brueggemann (1986, Marquette University Press)Document79 pagesRevelation and Violence, A Study in Contextualization - Walter Brueggemann (1986, Marquette University Press)atila-4-everNo ratings yet

- Matt 5-1-12 ExegesisDocument19 pagesMatt 5-1-12 ExegesisSid Sudiacal100% (6)

- Final Exam Study QuestionsDocument2 pagesFinal Exam Study QuestionsIoan LeonteNo ratings yet

- Roger Corless - Why Are There Monks and NunsDocument6 pagesRoger Corless - Why Are There Monks and NunsTiberiu OprisNo ratings yet

- V5-1 7 BellezaDocument28 pagesV5-1 7 BellezaDaniel FernandesNo ratings yet

- WONG - Matthean Understanding of SabbathDocument17 pagesWONG - Matthean Understanding of SabbathlaszlogalluszNo ratings yet

- New Testament Theology: An IntroductionFrom EverandNew Testament Theology: An IntroductionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Issues in New Testament Theology PDFDocument96 pagesIssues in New Testament Theology PDFrajivkarunNo ratings yet

- Course DescriptionDocument13 pagesCourse Descriptionlongdeal mzaziNo ratings yet

- Matthew's Mission Bracketology: Christ's Mission in The New CovenantDocument7 pagesMatthew's Mission Bracketology: Christ's Mission in The New CovenantChad Richard BressonNo ratings yet

- Fulfillment Quotations Introduction: Chapter 1Document13 pagesFulfillment Quotations Introduction: Chapter 1mertoos100% (1)

- Dirt, Greed and Sex: Sexual Ethics in the New Testament and their Implications for TodayFrom EverandDirt, Greed and Sex: Sexual Ethics in the New Testament and their Implications for TodayRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Instruction On Scripture and ChristologyDocument27 pagesInstruction On Scripture and ChristologyAlbertus Widya Rahmadi PutraNo ratings yet

- 21 Questions On Doctrine of ScriptureDocument90 pages21 Questions On Doctrine of ScriptureNick_MaNo ratings yet

- Snoptic Gosple11Document28 pagesSnoptic Gosple11Julius AliNo ratings yet

- Barth and TextualityDocument17 pagesBarth and TextualityMitrache MariusNo ratings yet

- Aquinas on Israel and the Church: The Question of Supersessionism in the Theology of Thomas AquinasFrom EverandAquinas on Israel and the Church: The Question of Supersessionism in the Theology of Thomas AquinasNo ratings yet

- Hermeneutic CircleDocument8 pagesHermeneutic CirclecisjrNo ratings yet

- Bokedal, Jansen, Borowski, Scripture and Theology in ContextDocument32 pagesBokedal, Jansen, Borowski, Scripture and Theology in ContextMichael MettsNo ratings yet

- Steinmetz Superiority of Precritical ExegesisDocument13 pagesSteinmetz Superiority of Precritical Exegesisrjbarryiv100% (2)

- Evangelical Hermeneutics - Robert L. Thomas (PDFDrive)Document584 pagesEvangelical Hermeneutics - Robert L. Thomas (PDFDrive)suwartono hasardjo100% (2)

- The Pentateuch: Interpreting Biblical Texts SeriesFrom EverandThe Pentateuch: Interpreting Biblical Texts SeriesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (8)

- Iberty NiversityDocument87 pagesIberty NiversityElías E. HerediaNo ratings yet

- Chapter TenTHE SUFFICIENCY OF TRADITION AND SCRIPTURE PDFDocument24 pagesChapter TenTHE SUFFICIENCY OF TRADITION AND SCRIPTURE PDFSalah ElbassiouniNo ratings yet

- The Future of Biblical Interpretation: Responsible Plurality in Biblical HermeneuticsFrom EverandThe Future of Biblical Interpretation: Responsible Plurality in Biblical HermeneuticsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Anders On TraditionDocument4 pagesAnders On TraditionnoquierodarinforNo ratings yet

- The Office of Peter: And the Structure of the ChurchFrom EverandThe Office of Peter: And the Structure of the ChurchNo ratings yet

- The Disputed Teachings of Vatican II: Continuity and Reversal in Catholic DoctrineFrom EverandThe Disputed Teachings of Vatican II: Continuity and Reversal in Catholic DoctrineNo ratings yet

- The Synoptic Problem: A HomeworkDocument6 pagesThe Synoptic Problem: A HomeworkGinoSDBNo ratings yet

- Understanding Jewish InfluenceDocument118 pagesUnderstanding Jewish InfluenceVictoriaGiladNo ratings yet

- Congregation Yeshuat Yisrael Franklin, TennesseeDocument50 pagesCongregation Yeshuat Yisrael Franklin, TennesseeDaniel Malic100% (1)

- Greenberg PDFDocument9 pagesGreenberg PDFAislingNo ratings yet

- Inheritance Rights of Women Under Jewish and Islamic LawDocument38 pagesInheritance Rights of Women Under Jewish and Islamic Lawאליעזר קופערNo ratings yet

- Rosh Hashanah 27Document38 pagesRosh Hashanah 27Julian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- Studies of Religion Past HSC QuestionsDocument21 pagesStudies of Religion Past HSC QuestionsMesina StantzosNo ratings yet

- Religious Studies Form 1 Notes Term 1 2024Document14 pagesReligious Studies Form 1 Notes Term 1 2024elasahmadizNo ratings yet

- Harnack A. - Marcion. The Gospel of The Alien GodDocument186 pagesHarnack A. - Marcion. The Gospel of The Alien GodDomenico CatalanoNo ratings yet

- Fulfillment of The LawDocument169 pagesFulfillment of The LawRobbert Adrianus Veen100% (2)

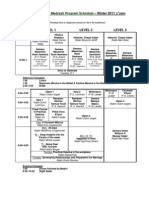

- IBMP Schedule Winter 2011Document2 pagesIBMP Schedule Winter 2011yehoshuadovidNo ratings yet

- James 2 1-13Document7 pagesJames 2 1-13richard5049No ratings yet

- General InterestDocument281 pagesGeneral InterestKhoo Beng Kiat100% (4)

- Furukawa Unic Hydraulic Crane CD PDF CollectionDocument23 pagesFurukawa Unic Hydraulic Crane CD PDF Collectionmikaylakelly141196atp100% (101)

- Understanding Christian Zionism - Paul WilkinsonDocument354 pagesUnderstanding Christian Zionism - Paul WilkinsonRaymond WilfongNo ratings yet

- Midrash Sobre o Mashiach Scr-Páginas-101-200 PDFDocument100 pagesMidrash Sobre o Mashiach Scr-Páginas-101-200 PDFshilomobenavrahamNo ratings yet

- Mystical Book RecommendedDocument2 pagesMystical Book Recommendedjeryon91No ratings yet

- Henry George and Zionism - Jewish CurrentsDocument5 pagesHenry George and Zionism - Jewish Currentst7v6kkfvbhNo ratings yet

- 37 Graves of The RighteousDocument28 pages37 Graves of The Righteouskevinj_jNo ratings yet

- Understanding Hashem's Ways: Volume XII - Issue 15 The DRS Weekly Torah PublicationDocument12 pagesUnderstanding Hashem's Ways: Volume XII - Issue 15 The DRS Weekly Torah Publicationoutdash2No ratings yet

- 10.the Esoteric and Inter-Religious Aspects of The Relation Philosophy - Kabbalah in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe - Yossef SchwartzDocument18 pages10.the Esoteric and Inter-Religious Aspects of The Relation Philosophy - Kabbalah in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe - Yossef Schwartzgtnlmnc99235No ratings yet

- Christianity NotesDocument10 pagesChristianity NotesKelvin kinyuaNo ratings yet

- CHRISTIANITYDocument28 pagesCHRISTIANITYSophia Dapigran Alcido100% (1)

- Lurianic Kabbalah: Unit 1: Introduction: Kabbalah Before and After The Expulsion From SpainDocument17 pagesLurianic Kabbalah: Unit 1: Introduction: Kabbalah Before and After The Expulsion From SpainAnonymous XSixrIuNo ratings yet

- Shulkhan Arukh ShabbatDocument493 pagesShulkhan Arukh ShabbatEdiciones YojévedNo ratings yet

- Hanukkah TriviaDocument5 pagesHanukkah TriviastavtiNo ratings yet

- Nietzsche S Jewish Problem Between Anti-Semitism and Anti-Judaism by Robert HolubDocument6 pagesNietzsche S Jewish Problem Between Anti-Semitism and Anti-Judaism by Robert HolublollipopfactorialNo ratings yet

- 2017 Taubman LecturesDocument1 page2017 Taubman LecturesmagnesmuseumNo ratings yet

- June-July 2008 Tidings Newsletter, Temple Ohabei ShalomDocument12 pagesJune-July 2008 Tidings Newsletter, Temple Ohabei ShalomTemple Ohabei ShalomNo ratings yet

Tagawa 1970

Tagawa 1970

Uploaded by

David MartínezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tagawa 1970

Tagawa 1970

Uploaded by

David MartínezCopyright:

Available Formats

New Testament Studies

http://journals.cambridge.org/NTS

Additional services for New Testament Studies:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

People and Community in the Gospel of Matthew

Kenzo Tagawa

New Testament Studies / Volume 16 / Issue 02 / January 1970, pp 149 - 162

DOI: 10.1017/S0028688500015460, Published online: 05 February 2009

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0028688500015460

How to cite this article:

Kenzo Tagawa (1970). People and Community in the Gospel of Matthew. New Testament

Studies, 16, pp 149-162 doi:10.1017/S0028688500015460

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/NTS, IP address: 138.251.14.35 on 03 May 2015

Mew Test. Stud. 16, pp. 149-62

KENZO TAGAWA

PEOPLE AND COMMUNITY IN THE

GOSPEL OF MATTHEW 1

A number of recent works have attempted to deal with the theological

thought of the evangelist Matthew using the method of 'Redaktions-

geschichte'. But as yet Hans Conzelmann's Matthew has not appeared.2

Certainly the joint work of G. Bornkamm, G. Barth and H. J. Held, the

works of R. Hummel, G. Strecker, K. Stendahl, W. Trilling and others3

have contributed considerably to this field of study. But at the present time

there is no agreement among scholars on the fundamental problem of what

is the essential concern of Matthean theology. It is true that the Law of

Moses and accordingly the problem of the fulfilment of Old Testament

prophecies is one of the most important problems for Matthew, and that the

present state of the church and the expectation of the eschaton, especially of

the last judgement, are also elements indispensable for understanding the

thoughts of the evangelist. But the fundamental problem is how to discover

the basis of Matthew's theology, by means of which the interpreter can

understand these individual elements as organically combined. One can

abstract from these elements several ideas which seem important for the

thought of Matthew. However, it is not the individual ideas themselves

which are so important, but the milieu which determines their meaning. In

the case of works such as that of Luke which have a definite and positive

theological emphasis, the interpreter has only to delineate that theology. But

in the case of the Gospel of Matthew the problem is not so simple. In Luke

and Acts the intention of the author was to show the linear development of

the history of salvation. In other words, the intention of Luke's redaction of the

Gospel materials was to organize them according to his historico-theological

idea. The success of the study of the Lukan theology by H. Conzelmann

consists in the agreement of the question posed by the interpreter with

the ideological intention of the evangelist. But in the case of the Gospel

according to Matthew it is questionable whether the main purpose of the

Gospel redaction was to impart a certain theological idea to its readers.

Naturally, we find here also some theological ideas emphasized. It is well

1

Dedicated to Professor Tateo Kanda to celebrate his seventieth birthday.

2

Cf. Die Mitte der Zeit, Studien zur Theologie des Lukas (5. Aufl. 1964), Tubingen.

8

G. Bornkamm, G. Barth and H . J . Held, (Jberlieferung und Auslegung im Matthdusevangelium

(Neukirchen, 1960); R. Hummel, Die Auseinandersetzung zwischen Kirche und Judentum im Matthaus-

evangelium (Miinchen, 1963); G. Strecker, Der Weg der Gerechtigkeit, Untersuchung zur Theologie des

Matthdus (Gottingen, 1962); K. Stendahl, The School of St Matthew (Upsala, 1954); W. Trilling,

Das wahre Israel, Studien zur Theologie des Mattha'usevangeliums (3. Aufl. 1964, Miinchen).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

15O KENZO TAGAWA

known, for example, that SiKcciocruvri is one of the fundamental concepts in

Matthew. One could enumerate others. But the question is, we repeat,

whether the main purpose of the evangelist was to present these theological

concepts. Did he not have another concern?

It is because of the fact that in Matthew there are contradictory ideas

expressed side by side with no attempt at harmony that we ask such a

hermeneutical question. Moreover, most of these contradictory ideas are

elements which the evangelist himself added to the traditional materials or

to which he gave special emphasis; thus they are to be considered as repre-

senting the personal thought of the evangelist. For example, concerning the

problem whether Christians must keep not only the Old Testament Torah

but the traditions of the rabbinical interpretation, he says on the one hand,

'The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses' seat; so practise and observe

whatever they tell you' (xxiii. 2 f.). This is the opening verse of a long diatribe

against the scribes and the Pharisees which is put into the mouth of Jesus.

Apart from the question of the origin of this sentence, its present position, at

least, is due to the redactional work of the evangelist. It introduces the

subject-matter to be discussed in the whole of chapter xxiii. Consequently

Jesus' main theme in this chapter, according to Matthew, is that one must

keep the words of the scribes and the Pharisees, because what they say is

right, but that one must criticize their hypocrisy, since they themselves do not

practise what they preach. So the evangelist considers the scribal and

Pharisaic traditions of the interpretation of the Old Testament Torah as

substantially correct. But on the other hand, in xv. 3, he distinguishes clearly

between the Torah of the Old Testament and the traditions of the elders, and

rejects the latter. This contradicts explicitly xxiii. 2 f. In xv. 3 Matthew adopts

the sentence of the Markan source without changing it, so we cannot

consider it as his original thought. But he almost always omits sentences

which are not in accordance with his own opinion. In this case, on the

contrary, he not only adopts this sentence but rewrites the whole pericope

which includes it (xv. 1-20) in greater detail than his source. So here the

evangelist is of the same opinion as his source, rejecting 'the traditions of the

elders' as opposed to the commandments of God. What does it mean now

that the evangelist could hold these two contradictory positions at the same

time? Of course it is possible to interpret it as laying stress on one side or the

other. If stress is laid on xv. 3, the conclusion is that Matthew did not reject

the rabbinic traditions in principle, but that returning to the essential spirit

of the Torah, the will of God, he denied in reality the thought of the rabbinic

traditions.1 If stress is laid on xxiii. 2 f., the conclusion is that for Matthew

the scribal traditions had authority in principle and in most actual cases, but

1

G. Barth, in Bornkamm-Barth-Held, op. cit. pp. 80ff.When Barth says that mStirro in xxiii. 2 does

not include the rabbinic tradition, he does violence to the text. What would remain in 'all that the

scribes and the Pharisees tell you', if not the scribal traditions?

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

PEOPLE AND COMMUNITY IN MATTHEW 151

1

that he criticized only some of their applications. Whichever interpretation

is right, the essential problem for the understanding of Matthew is how to

deal with this sort of contradiction. If we give up one side of the contra-

diction, considering it as a residuum of old tradition which has no concern

with the personal thought of the evangelist, we could get a coherent image

of the thought of the evangelist. But it is only an unreal image which results

from an erroneous method.2 What is necessary for the interpreter is to recognize

the fact that the evangelist Matthew is a writer who blithely makes such con-

tradictory utterances. That is to say, there existed for the evangelist Matthew

no question of principle whether the scribal traditions are in themselves

right or not. At least he did not consciously ask this question. Therefore it is not

appropriate to try to interpret the Gospel of Matthew with such a question of

principle. Matthew is not a theorist. This problem of the criticism of the scribal

traditions is rather to be solved from the practical point of view of how and in

what sense the evangelist would confront the Pharisaic Judaism of his time.

The same thing is true concerning the appreciation of the Torah of the

Old Testament itself. On one side the evangelist says one must keep it

faithfully down to the last jot and tittle (v. 17 f.). But in the antithesis which

follows immediately (v. 21 ff.), the Old Testament's commandments and the

words of Jesus are put in contrast. In this case also it is not right simply to

dismiss one of these positions as not being an expression of Matthew's

thought. In the same chapter five, Matthew stresses the necessity of keeping

all the laws of the Old Testament and yet he criticizes them from the point

of view of the more radical commandments ofJesus. The question of principle,

whether the whole Torah of the Old Testament is appropriate or not, is no

more a problem for the evangelist in this case than in the other.

We can find many other examples of this kind of contradiction. One of the

most important of them is the problem of the Gentiles and the Jews. On the

one hand Matthew rejects the Gentiles most decisively, yet on the other hand

he criticizes the Jews very severely and it seems often that according to his

opinion ultimate salvation will be given to the Gentiles. The purpose of this

study is to ask the question how and why the same evangelist could take

these contradictory positions. But before we analyse this problem, we need

to clarify a little more the question of methodology.

We began by questioning whether Matthew wrote his Gospel in order to

present a certain theological idea. We found that this is questionable,

because we find so many contradictory ideas in that Gospel. So what is

important from the methodological point of view is not to ask what theo-

logical ideas the evangelist would present to his readers, but to put a different

set of questions. Georg Strecker, for example, whose work is one of the most

distinguished studies of the Redaktionsgeschichte of Matthew, seems not to be

1

R. Hummel, op. cit. pp. 46ff.,among others.We think this interpretation is right in its major line.

8

The interpretation of G. Barth cited on p. 150 n. 1 is an example.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

152 KENZO TAGAWA

fully aware of this methodological problem. Concerning the purpose of the

evangelist, he says, ' The question to ask concerning the theological concepts

of Matthew is, what the relation is between what is historical and what is

eschatological in the redaction of the first Gospel. n For example, he looks at

the relation between ecclesiology as a historical element and the expectation

of the eschaton as an eschatological element, the relation between the life of

Jesus as a historical event and the eschatological Christ, etc., and he con-

cludes that the relation of the historical and the eschatological elements is

not to be dissolved into an 'either-or', but to be understood as a 'both-and'.

Of course the relation between the historical and the eschatological is one of

the main problems of New Testament theology. But it is questionable

whether Matthew consciously put to himself this question. Strecker's method

of analysing the gospel aims at placing the evangelist in the development of

the history of theological ideas. But he presupposes the main line of the

development of theological ideas as already well established. The question,

however, is whether the main concern of the evangelist was to define his own

theological concepts on the line of this historical development of theological

ideas. The existence of many contradictory ideas in the Gospel militates

against this point of view. Matthew is not a theologian in the strict sense of

the word. He is not a Luke. It is because of this methodological one-sidedness

that Strecker so often introduces uncritically into the exegesis of Matthew's

text the Lukan schema of the history of salvation.

So we must go beyond the question of theological ideas and inquire what is

the milieu of the thinking of the evangelist Matthew which perhaps helps ex-

plain the coexistence in the same work of theological ideas so often contradic-

tory to each other. We should inquire into the social milieu of the evangelist.

The proposal has been made by some scholars that the Gospel of Matthew is a

sort of catechetical teaching of his church,2 or that it is a homiletic re-

interpretation of the earlier Gospel traditions.3 These hypotheses seem valid.

But our purpose is not to inquire into the general hypothetical framework of

the Gospel, but to consider the concrete problem presented by the text4

along the lines of the above methodological reflections.

11

The author of the Gospel according to Matthew shows quite contradictory

attitudes concerning the problem of the Gentiles and the Jews. In regard to

the mission, it is written that the disciples sent by Jesus must go only to the

1

G. Strecker, op. cit. p. 47.

2

Cf. E. von Dobschiitz, 'Matthaus als Rabbi und Katechet', £.JV.W. xxvn (1928), 338-48;

G. Schille, 'Bemerkungen zur Formgeschichte des Evangeliums, II, Das Evangelium des Matthaus

als Katechismus', N.T.S. iv (1958), 101-14.

3

Cf. G. D. Kilpatrick, The Origins of the Gospel according to St Matthew (Oxford, 1946).

4

The study of the formula citations by K. Stendahl, op. cit. shows a deep insight in this direction.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

PEOPLE AND COMMUNITY IN MATTHEW I53

'lost sheep of the house of Israel', and not 'into the way of the Gentiles'

(x. 5 f.), and Jesus declares that he is sent only to the lost sheep of the house

of Israel (xv. 24)-1 However, in xxviii. 18-20, the resurrected Christ com-

mands his disciples to go into all the world. Since this commandment forms

the final word of the Gospel, we must consider it as consciously stressed. This

is a well-known contradiction which students of the Gospel do not neglect.

But the contradictory attitude of the evangelist towards Jews and Gentiles

is not limited to the question of who is to be evangelized. The narrative of

viii. 5-13, for instance, is interpreted ordinarily to mean that the Gentiles

will be accepted into the Kingdom of Heaven and the Israelites will be

rejected. However, in the narrative of xv. 21-8, it is presupposed that in

general the Jews will participate in the final salvation, the Gentiles being

admitted only as exceptions. In v. 47; vi. 7, 32 and xviii. 17, the Gentiles are

mentioned as those on the way to perdition, and in two of these texts they are

linked with the tax-collectors. Such expressions cannot be understood other-

wise than as uttered in the spirit of extremely strong Jewish prejudice. But on

the other hand there are texts which can be interpreted at least at first sight

as showing an anti-Jewish tendency.2 From these texts one might conclude

that Matthew is a Gentile Christian, but the insistence that not an iota, not

a jot, will pass from the Law (v. 17 f.) is only possible for a Jew, for whom

the authority of the Law was absolute. But the same evangelist insists that the

first place of the public activity ofJesus was 'Galilee of the Gentiles' (iv. 15).

In considering that the Galilee of that time was no longer a district of the

Gentiles, but of the Jews, we have no alternative but to conclude that the

evangelist consciously combines the activity ofJesus with the Gentile mission.

But in the genealogy of Jesus, Matthew declares from the very beginning of

the Gospel that Jesus was the son of David, the son of Abraham, that is, a

Jew of the Jews. Being the son of David, he must have been born in Bethlehem

(ii. 5 f.).

The brief enumeration of the texts in question given above shows clearly

enough that this problem is a crucial one for the entire Gospel, one which

must be dealt with in order to arrive at the basic position of the evangelist.

To begin with, the question of whether Matthew was a Jewish or Gentile

Christian depends upon one's judgement of these texts. And upon the answer

to this question one's interpretation of the essential problems of the Gospel,

such as its understanding of the Old Testament tradition, the Law, the

Church, etc., depends. The fact that there are so many texts concerning the

problem of the Jews and the Gentiles in itself witnesses to the fact that this is

1

ix. 35-8 should be understood in the same sense. The image of sheep without a shepherd is an

image applied in the Old Testament to the people of Israel (Num. xxvii. 17; I Kings xxii. 17;

II Chron. xviii. 16; Ezek. xxxiv. 5; Judith xi. 19; Jer. xxvii (1). 6), and the same expression is

applied in Matthew always to Israel (x. 6; xv. 24). So in this context it is Israel which is like sheep

without a shepherd.

8

At least, following G. Strecker, viii. 5-13; ix. 336-34; xi. 16-24; *"• 38-45; *>"'•10-13; xv. 21-8;

xxi. 12-16; xxi. 33-xxii. 14; xxiii. 37-9; xxvii. 24 f. show an anti-Jewish tendency.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

154 KENZO TAGAWA

one of the main concerns of Matthew. As we try to solve this problem, the

following two points must be taken into consideration.

(i) The texts mentioned above which reflect the problem of the Jews and

the Gentiles are usually passages where the redactional intention of the

evangelist is clear, v. 5 f. and xv. 24 are the most important of the texts

which show Judaistic or anti-Gentile tendencies. Both of these are the

additions made by Matthew to the Markan source. So there is no room for

doubt that Matthew wanted to lay stress on the motive ' only to the lost sheep

of the house of Israel'. Even if these logia had had their origin in the earlier

tradition, it is the evangelist Matthew who inserted them into the context of

the Markan source. The disdainful usage of the word £0VIK6S in v. 47; vi. 7

and xviii. 17 is peculiarly Matthean. It is possible that this usage was

motivated by the earlier tradition of Q_ found in vi. 32 ( = Lk. xii. 30) which

speaks of the desire of TT&VTOC TOC E0vr) as something inferior. However,

Matthew, by the redactional phrases of v. 47; vi. 7 and xviii. 17, lays more

stress on this motive than Q_does, at the same time that the other evangelists

avoid doing so. The word on the eternal validity of the Law (v. 17 f.) could

also be an old logion, but it is only Matthew who inserted it into his Gospel.

The opening words of the Gospel, 'Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of

Abraham', because of their position, cannot be understood otherwise than as

an intentional expression of his Christology. The legend that Jesus was born

at Bethlehem (ii. 5 f.) is certainly a tradition earlier than the redaction of the

Matthean Gospel. It is not specifically Matthean. But if he had had no

positive appreciation of this motive,1 he could have introduced it as an

erroneous opinion of some unfaithful people, as is actually the case in the

Johannine Gospel (cf. John vii. 41 f.).

On the other hand, most of the texts which show a universalist or anti-

Jewish tendency should be regarded as redactional work. It is clear that

xxviii. 18-20, being the final words of the Gospel, represents the opinion of

the evangelist. In the narrative of the centurion (viii. 5-13), the praise

accorded to the deep faith of this Gentile is the central point and therefore

must be considered as a part of the original story (cf. Lk. vii. 1-10), but

w . 11 f. which form the conclusion of the Matthean edition of this narrative

are clearly added by the evangelist. And it is just because of these two verses

that the interpreters speak often of the anti-Jewish character of this narrative.

The phrase 'Galilee of the Gentiles' (iv. 15) is found in one of Matthew's

characteristic Old Testament citations (Reflexionszitate), and this citation is

an addition to Mk. i. 14 f., so it must represent the thought of the evangelist.

Accordingly one cannot be satisfied with the conclusion that one attitude

is found in the earlier traditional materials while the other represents the

evangelist's own attitude. The assertion that the primitive Church and

1

As for Mark, either he did not know it, or he omitted it intentionally.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

PEOPLE AND COMMUNITY IN MATTHEW 155

Matthew with their narrow nationalism distorted Jesus' original universalism

results generally from the one-sided apologetic of the interpreters. Certainly

it does not explain the thought of Matthew. Nor are other explanations, such

as attributing Matt. x. 5 f. to the Judaistic tradition of the primitive Jerusalem

church and xxviii. 18-20 to the later Hellenistic church to which Matthew

belonged,1 or that Jesus prohibited his disciples from the Gentile mission

(x. 5f.) during his lifetime, but that the Church ignored this and began

the world mission,2 any more satisfactory. All these explanations fail to

grasp where the problem is. The contradiction between Judaistic and

universalist tendencies remains as an inherent peculiarity of the thought of

Matthew.3

(2) When the Jewish-Gentile problem is raised, we tend to think in terms

of the Gentile mission mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles and the Pauline

Epistles. So almost all interpreters see this problem reflected also in Matthew,

and they analyse the text in order to determine whether it is written from the

standpoint of the Gentile mission or from the more narrowly Jewish stand-

point. In so doing, they apply rather mechanically to the text of the Matthean

Gospel the simplified schema of the development of the mission in the

primitive Church as presented by the author of the Acts: first the Jewish

mission and then the Gentile mission. But this is too schematic and it is very

improbable that the problem of the Gentile mission was solved so simply as is

described in the Acts. The situation was surely much more complicated and

varied according to the particular region involved. Moreover, it is important

to recognize here that the problem is broader than that of missionary

activity; as is clear from the texts discussed above, it is the more compre-

hensive question of national consciousness.

in

Before proposing our own, we shall examine the proposed solutions of other

scholars, arranging them into some types.

(1) The Gospel of Matthew as purely Jewish Christian. This type pays

no attention to the Jewish-Gentile problem we are dealing with, but takes

into consideration only the Judaistic elements.4 This is out of the question.

1

R. Bultmann, Die Geschichte der synoptischen Tradition, p. 156 n. 1.

2

J. Jeremias, Jesu Verheifiung fiir die Volker (Stuttgart, 1956).

3

This type of oversimplification results in eisegesis of the texts. For example, J. Jeremias starts

from the presupposition that Matthew supports the mission to the Gentiles, so he finds allusions to

the Gentile mission even in texts where it is not mentioned, e.g. v. 13f. where there is no mention

of the Gentiles, not to speak of the Gentile mission! xxii. 9 f.; xxv. 40, 'one of the least of these'

means, according to Jeremias, 'die unter den Heiden predigenden Jiinger'!

4

There are many studies of Matthew from this one-sided viewpoint. Here we mention as an

example E. K. Winter, 'Das Evangelium der jerusalemischen Mutterkirche', Judaica, ix (1953),

1-33. Beginning with the observation, right in itself, that there are many elements of a Jewish scribal

character in Matthew, he immediately concludes that the Gospel of Matthew is a product of the

'mother-church of Jerusalem' and is written in the purely Jewish Christian spirit.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

156 KENZO TAGAWA

(2) The 'heilsgeschichtlich' interpretation. This is one of the most pre-

dominant interpretations today and one can regard it as a reaction to the

first type, which was predominant one generation ago. According to this

second type of interpretation, Matthew does not place the Jews and the

Gentiles on the same level of the history of salvation, but he distinguishes

different stages of the history of God's activity. The time of Jesus' earthly life

and the time of the Church belong to different stages of this history, and the

subjects of evangelism are different at different stages. The period of Jesus'

lifetime is in one sense a prolongation of the period of Israel, so during this

time the mission is limited to Israel (x. 5 f.; xv. 24). But the Church led by

the resurrected Christ must carry out a mission to the whole world (xxviii.

18-20). Thus the two tendencies in Matthew are not really contradictory.

All particularistic Jewish tendency is eliminated. Matthew writes from the

standpoint of the Gentile church.1

But as was noted above, this type of explanation is a reaction to the first

type and oversimplifies in the other direction. This explanation would be

possible only if we accept the presupposition that the evangelist was writing

from the standpoint of the Gentile church,2 but this is most improbable.3

1

G. Strecker, op. cit. pp. 99-118; W. Trilling, op. cit. pp. 99-105; R. Hummel, op. cit. pp. 141 f.;

G. Bornkamm, ' Der Auferstandene und der Irdische, Mt. 28: 16—00', £eit und Geschichte, Dankesgabc

an Rudolf Bultmann (Tubingen, 1964), pp. 171-92 (esp. pp. 181 f.).

2

Bornkamm describes very well in this article the fact that the evangelist Matthew, being a

Hellenistic Jewish Christian, opposed Pharisaic Judaism on the one hand, though standing within

the Jewish tradition, but on the other hand, though adopting the Christology of the Hellenistic

church, criticized that Christology from the standpoint of the Jewish tradition. In spite of this correct

understanding, Bornkamm tries to solve the problem of the contradiction between ch. x and ch. xxviii

by introducing period-differentiation of the history of salvation [heilsgeschichtliche Periodisierung). But

it seems to me quite improbable that a man who was very proud of standing in the Jewish tradition

should have been convinced that the present post-resurrection period was the time of the Gentile

church. The Apostle Paul was also racially a Jew, but he was the very apostle who had abandoned

Judaism because of Christ, so that he was able to become the apostle to the Gentiles (cf. Phil. iii. 1 ff.).

Matthew is different from Paul just at this point.

3

The recent attempts made by G. Strecker, W. Trilling and P. Nepper-Christensen to prove that

Matthew was a Gentile Christian are not convincing. P. Nepper-Christensen, Das Matthaus-

evangelium, einjudenchristliches Evangelium?, Ada Theologica Danica, 1 (Aarhus, 1958), raises five points:

(1) the traditions of the church fathers are not sure enough to prove the Jewish character of

Matthew; (2) the first Gospel is originally written in Greek and not a translation from a Semitic

language; (3) the schema prophecy-fulfilment is a motif formed before Matthew and does not reflect

Matthew's redaction; (4) there is no typology in Matthew; (5) the texts which show Jewish ten-

dencies are taken from older traditions. Of these five points, the first, second, and fourth prove

nothing about the nationality of Matthew. The third and fifth points are questionable. Upon these

two points, G. Strecker, op. cit. pp. 15-35, is exegetically more detailed. But his arguments are very

forced, and reveal his methodological faults. For example, the word on divorce (Matt. v. 32 f. and

xix. 3-9): all commentators agree that the phrase 'except on the ground of unchastity' (v. 32;

xix. 9) is an addition of Jewish character added to the sources of Q, (v. 32) and Mark (xix. 9).

Strecker argues against this agreement that this addition belongs also to a tradition earlier than the

First Gospel. According to him, if Matthew had wanted to reinterpret this word of Jesus from his own

viewpoint, it would have been necessary for him to give a more detailed account; the fact that only

a few words are added shows that the re-interpretation was not made on his own initiative, but was

given by the tradition. But in so arguing Strecker exposes his own misconception of the character

of the redactional activity of the evangelists. The synoptic writers never develop their interpretation

of the earlier traditions by detailed reasoning, but they reveal their opinion by delicate additions

to and omissions from the traditions. In this sense they are editors and not authors. Moreover,

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

PEOPLE AND COMMUNITY IN MATTHEW I57

Moreover, this interpretation presupposes a Lukan view of the history of

salvation as the framework also of Matthew's theology. But this view, which

sees the time of Jesus and the time of the Church as different stages of the

history of salvation, is peculiar to the Lukan theology,1 and it is impossible

to regard it as applying to New Testament thought in general. Certainly it

cannot be applied to Matthew. He presupposes the homogeneity of the time

of Jesus and that of the Church, and he never considers Jesus' word as

applicable only to his lifetime.2

(3) ' Christianism' as a third way over against Judaism and paganism.

The third type of interpretation is that Matthew criticizes both the Jews and

the Gentiles and seeks for a third way. He distinguishes the Christian com-

munity from the Jewish national community and on the other hand maintains

it as a third reality over against paganism.3 This interpretation has true in-

sight into the dilemma we are dealing with. But the dilemma remains,

because there is no possibility of a third way. In other words this is not, or at

least not only, a question of religious beliefs, but of national consciousness.

when Strecker says, ' wahrscheinlicher ist daher, daB der Redaktor schon in einer Tradition lebte,

die die Ehegesetzgebung in dieser (rabbinischen) Form praktizierte, und daB er sie hier als Ein-

fiigung in seine Vorlagen schriftlich niederlegte. Der jiidische EinfluB ist danach ein fester Bestand-

teil der vormatthaischen mundlichen t)berlieferung' (p. 17), he falls into self-contradiction. If

Matthew 'lived in such a Jewish tradition', if he himself adopted such a tradition—a correct

assumption—it is anything but a proof of the non-Jewish character of the evangelist Matthew; it

proves, on the contrary, that the evangelist shared in the thinking of the social group which preserved

the tradition. So Strecker not only misunderstands this fact, but he develops his arguments on

methodologically faulty procedures. In all the other cases also, e.g. the citations of the Old Testa-

ment, the pericope of xv. 1-20, the pericopae of the sabbath problem (xii. 1-8, 9-14), etc. he

attributes the elements of Jewish character to the earlier tradition. This one-sided and arbitrary

elimination of materials unfavourable to his thesis is the fatal defect of his detailed study. The

discussion given by W. Trilling on this point is not far from that of Strecker. So we find no reason to

reject the traditional view that Matthew was a Jewish Christian.

1

H. Conzelmann's study of the Lukan theology clarifies this very fact. R. Hummel, op. cit.

pp. 141 f. would find the same schema of the different periods of the history of salvation in the

expression peculiar to Matthew dm' dpTi (xxiii. 39; xxvi. 64). According to him, when Matthew says

' from now on', it means,' Die Erhohung Jesu beendet seine speziell auf Israel gerichtete messianische

Wirksamkeit, charakterisiert sie als eine Epoche der Niedrigkeit und macht den Weg frei fur die

Heidenmission'. Surely 'from now on' in xxvi. 64 designates a differentiation of the Christological

situation. 'Till now'Jesus has been in the humble state of the incarnation, but 'from now on' he

will be the glorified Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power. But one must note that this text

concerns only the Christological situation, not the heilsgeschichtlich period-differentiation. The state

of Jesus is different in his lifetime on earth and after his resurrection, but the discipleship is always

the same from the Matthean point of view; the fKKAtiuia existed for him from the lifetime of Jesus and

its essence has not been changed since then. Moreover, the fact that 4TT'fip-nin Matthew does not

mean necessarily different epochs of the history of salvation is also proved from the usage of An-6 T6TE.

This is also a peculiarly Matthean expression and is the narrative expression which corresponds to

the im'fip-nof Jesus' own words. It is used three times, once to mark the beginning of the public

activity of Jesus (iv. 17), then to mark the first revelation of intention of suffering (xvi. 21), and

finally with reference to the decision of Judas Iscariot to seek an opportunity to betray Jesus

(xxvi. 16). So the expression 'from that time' corresponding to 'from now on' of xxvi. 64 means in

Matthew that something new is beginning, but it does not mean necessarily the differentiation of the

periods of the history of salvation, the time of Jesus and that of the Church.

a

Cf. F. Hahn, Das Verstandnis der Mission im Neuen Testament (Neukirchen, 1963). All the long

speeches of Jesus in Matthew are recorded as directly oriented to the Church of Matthew's time.

3

What R. Hummel says of the relation of the Church and Israel, op. cit. pp. 157ff.,is close to

this type of interpretation.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

158 KENZO TAGAWA

And as far as national consciousness is concerned, there can be no third way

other than Jewish or Gentile. One can espouse as an ideal the universalism

which transcends national consciousness. But the evangelist Matthew does

not think in such terms. He would rather be positively a Jew and in this

sense he rejects what is pagan (cf. the disdainful use of the word E0VIKOS).

Matthew tries to transcend his existence of being Jewish while remaining

positively a Jew.

(4) The interpretation of G. D. Kilpatrick. This is a further development

of the previous type.1 According to him, the evangelist Matthew after all

cannot be regarded other than as a Jewish Christian. Matthew speaks of the

Gentile mission from the viewpoint of the Jewish Christians, but it is only a

peripheral activity, the Israelite traditions being the centre.2 On the other

hand, the criticism made by Matthew against the Jews is not really aimed at

the Jewish people as a whole but mainly at the Pharisaic sect. This comes

close to my own view but still is not completely satisfactory. Many exegetical

problems still remain. According to Kilpatrick, many of Matthew's criticisms

of the Jews are really directed to the religious leaders, especially the Pharisees.

But this is exegetically unjustifiable. Matthew's criticisms are directed to

a much wider milieu.

IV

This problem should be thought of not in terms of theological ideas in the

narrow sense of the word, but in terms of the evangelist's ecclesiastical

standpoint. Not that we are interested in his ecclesiology, but we wish to

determine the nature of the community in which he actually was living, the

Church as his social basis. The consciousness of his life in this Church com-

munity is the fundamental basis of the thought of Matthew.3 He understood

himself as being in the Church community and wrote his Gospel for this

community. This situation explains well why Matthew laid stress on the Law

and ethical teachings. It is these elements which prescribe the standards for

life in the community.4 And it is this community consciousness which is a

1

G. D. Kilpatrick, op. cit. pp. 101 ff.

2

In so far as it concerns the problem of the mission to the Gentiles, F. Hahn is of the same

opinion, cf. op. cit. pp. 108ff.'Was Matthaus in seiner.. .Weise damit zum Ausdruck bringen will,

ist die Prioritat und bleibende Verpflichtung der Mission an Israel... die aber nur recht betrieben

wird, wenn im Wirken unter alien Volkern zugleich der universale Auftrag wahrgenommen ist'

(p. i n ) . This interpretation is to some degree right. But it does not take into consideration the

exclusive meaning of the utterance 'only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel'. 'Only to Israel' is

not the same thing as the priority of Israel. The contradiction remains a contradiction.

3

The recent commentary of P. Bonnard, L'£vangile selon Saint Matthieu (Neuchatel, 1963), tries

to analyse the Gospel of Matthew from this point of view, but it is to be regretted that this point of

view is not sufficiently applied to the exegesis of each text.

4

It is S. Yagi to whom I owe the important suggestion that the basic key to the problem of the

Gospel of Matthew is its community consciousness; cf. especially his recent article, 'Sin and its

Negation in Matthew and Luke' (written in Japanese), in: Seisho ni okeru Hitei no Mondai (The

Problem of Negation in the Bible), symposium published by the Japanese Institute of Biblical

Studies (Tokyo, 1967), pp. 90-106.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

PEOPLE AND COMMUNITY IN MATTHEW 159

continuation of the consciousness of the national community of Israel. Israel,

understood as a community existing before God, and the Church, the com-

munity founded upon the Lord Jesus, are identified half unconsciously in the

thought of Matthew. This fact has been well noted by W. Trilling.1 Matthew

does not use any such expression as ' the new Israel' by which to distinguish

the Church as something different from the old Israel, though not losing

continuity with it. For him, the Church itself is the true Israel. Nevertheless,

while having a keen insight into this fact, Trilling does not press on to its full

conclusion and instead introduces the view of the periodical stages of the

history of salvation. This is because he does not grasp the meaning of the

Church as a milieu in which the evangelist develops his thought, but only

considers it as a theological idea. In reality Matthew has a very strong

consciousness of being a member of a community, but he makes no effort to

give a historico-theological explanation of the relation of the Church to

Israel. He is clearly aware of the fact that the people Israel and the Christian

Church are not directly equal, but on the other hand, he confuses them

because both are the milieu in which he finds his own existence. From this

confusion arises the dilemma of the Jewish-Gentile problem.

On the basis of this observation we can now understand both the anti-

Jewish and anti-Gentile statements. First, for him the Church is the true

Israel. This is recognized in the usage of the word Acros in i. 21. Aoc6s is here

'the people ofJesus whom he will save from their sins'. This sentence is a free

citation of Ps. cxxx. 8 (LXX), and Matthew writes 'his [Jesus'] people'

where the psalmist says 'Israel'. The people of the Lord which is to be saved

is traditionally Israel, but it is for Matthew at the same time the Christian

community, the people of Jesus Christ. As long as the Church is the true

Israel, it is a sin to be a Gentile; therefore Gentiles are to be treated like tax-

collectors (v. 46 f.; xviii. 17; cf. vi. 6, 32). Consequently the mission of Jesus

and his disciples is to the people who are to form the true Israel. The limita-

tion of the mission exclusively to the lost sheep of the house of Israel (x. 5 f.;

xv. 24)2 is also to be understood in this sense. This is why Christian mission-

aries, not only in the lifetime of Jesus but also in the time of the Church,

must not go to the Gentiles. These utterances are made from the standpoint

of the identification of Israel with the Christian community. They are, so to

speak, utterances which arise naturally from national consciousness. But on

the other hand, the Church is not for Matthew merely the Jewish race. It is

the chosen people out of Israel who constitute the Church community. It is

not without reason that only Matthew among the Synoptics uses the word

^KKAricrfcc (xvi. 18; xviii. 17). This fact shows that Matthew grasped the Church

1

W. Trilling, op. dl. pp. 95 f.

a

x. 23 belongs to another context. This sentence treats, at least in the intention of Matthew, of

the relation of the persecution to the eschaton, so the problem of the evangelistic mission is not

directly mentioned here, nor the problem of national consciousness. Cf. E. Bammel, ' Matthaus

10: 23', Studia Theologica, xv (1962), 79-92.

II NTSXVI

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

l6o KENZO TAGAWA

as something opposed to the synagogue.1 From this viewpoint he criticizes

the Jews. Most of his criticisms are directed quite naturally to the Pharisees

and the scribes. But it is not only the Pharisees that he criticizes. To be a Jew

by birth is not sufficient qualification to be counted among the chosen people

of God (iii. gf.). 2

But the anti-Jewish polemics do not have the meaning that because the

Jews rejected Jesus their time was finished and salvation would now be given

to the Gentiles. This kind of theoretical theology would be impossible for

Matthew with his high national consciousness. The texts which are usually

understood in this heilsgeschichtlich sense of period-differentiation ought not to

be so interpreted. For example, note in viii. 11 f. the conclusion added by

Matthew to the narrative of the healing of the centurion's servant (cf. Lk.

vii. I-IO) ;3 in these verses, 'those who will come from east and west and sit

at table with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven' and

' the sons of the kingdom (uioi Tfjs |3occnAEias) who will be thrown into the

outer darkness' are put in contrast. If the latter designate the Jews,4 the

former should logically be the Gentiles, and the point of these verses should

be that those who will participate in the eschatological salvation are not

Jews, but Gentiles.5 But in its other occurrences in Matthew the expression

uioi Tfjs pctaiAsias does not mean the Jewish people as a whole, but those who

belong to the Christian Church (xiii. 38; cf. xxv. 34). Therefore it ought to

have the same meaning here. Consequently viii. 11 f. expresses almost the

same idea as the parable of the tares and its allegorical explanation (xiii. 24-

30, 37-43). Matthew gives his readers the strict warning that just to be a

member of the Church at the present time (that is, to be sons of the kingdom)

does not guarantee final salvation.6 The question here is ' the mixed state of

the Church' and not the problem of the Jews and the Gentiles. Among those

who still remain Gentiles, not belonging now to the true Israel, will be found

the real Christians who have more profound faith than you who call your-

selves Christians, so be careful! Certainly it is asserted here that the Gentiles

will enter the kingdom of heaven, but this does not mean that the Jewish

people as a whole will be rejected. Only those who have no true faith will be

1

Cf. G. Bornkamm, op. cit. p. 183. The fact that Matthew alone of the synoptic evangelists uses

the word £KKAT|CT1C( is not an objection to our thesis. This fact shows, of course, that the community

consciousness of Matthew was very strong, but not that Matthew reflected upon the essence of the

community.

2

According to G. Bornkamm, op. cit. p. 189, the descent from Abraham, emphasized along with

the Davidic descent, in the genealogy of Matt. i. 1-17 is also an expression of the same assertion.

' Die natiirliche Abrahamskindschaft charakterisiert nicht mehr eo ipso das Gottesvolk und garantiert

ihm Anteil an Segen und VerheiBung. Mit um so starkerem Nachdruck heiBt es jetzt betont und

exklusiv im Blick auf Ghristus: ER ist Davids und Abrahams Sohn.'

3

Cf.E. Haenchen, 'Faith and Miracle', Studia Evangelica, 1 (7*.u.[A LXXIH), 1959, Berlin, pp.495-8.

4

A. H. M'Neile, The Gospel according to St Matthew (London, 1915), ad loc, and P. Bonnard,

op. cit. ad loc.

6

G. Strecker, op. cit. pp. 99-101; M'Neile, ad loc; Bonnard, ad loc.

0

Cf. C. F. Smith, 'The Mixed State of the Church in Matthew's Gospel', J.B.L. LXXXII (1963),

149-68.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

PEOPLE AND COMMUNITY IN MATTHEW l6l

rejected. And having been welcomed into the kingdom of heaven, the

Gentiles are no longer Gentiles. They will be members of the people of

Israel, as they sit at table with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. The Gentiles are,

so to speak, potential Israelites. TJ|us interpreted, we find that in these

verses also Matthew understands the Gentiles from the standpoint of his

national consciousness.

The same thing can be said about the parable of the wicked husbandmen

(xxi. 33-46). Verse 43 is an interpretation added by Matthew to the Markan

material (Mk. xii. 1-12). Matthew concludes the parable by saying, 'The

kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a nation (s0vos)

producing the fruits of it.' If the word EQVOS meant here the Gentiles, 'you'

in the first half of the sentence should mean the Jews and consequently the

meaning of this verse should be that the kingdom of God will be taken away

from the Jews and given to the Gentiles.1 But neither of these identifications

is right. "EOvos is here in the singular form, so it does not mean the Gentile

people as distinguished from the Jews.2 ' You' in this context indicates the

leaders of the Jewish people, the scribes and the Pharisees (cf. v. 45). Ac-

cordingly, the evangelist Matthew interprets this parable as a criticism against

Pharisaic Judaism and he declares that the kingdom of God will be given to

'a nation that yields the proper fruits'. It is clear that Matthew is thinking of

the Church which is now in the process of formation. The fact that the

Christian community is here called £0vos corresponds to the usage of Aoc6s in

i. 21 where the Church is understood as the true Israel.3 The evangelist here

criticizes Pharisaic Judaism from the standpoint of the Christian Church. So

this text has nothing to do with the Gentile-Jew antithesis.4

On the basis of the above consideration we can understand also in what

sense Matthew is in favour of the Gentile mission. In so far as he identifies the

Church with the national community, he says not to go beyond Israel, but on

the other hand, in so far as the Church is recognized as a chosen community

of faith distinguished from the Jewish nation, the commandment to go and to

make disciples of all the nations (xxviii. 19) is quite comprehensible.5 These

utterances, though logically in contradiction, can be made because for

Matthew the two communities, though different in nature, are overlapping.

In any case, as we have seen concerning viii. 5-13, when Matthew thinks of

1

G. Strecker, op. cit. p. 170.

a

W. Trilling, op. cit. p. 6 1 ; Bonnard, ad loc; E. Lohmeyer, Das Evangelium des Matthaus (2. Aufl.

Gottingen, 1958), ad loc.

3

F. Hahn, op. cit. p. 108.

4

G. Strecker designates many other texts as of anti-Jewish tendency, op. cit. pp. 99 ff. But within

these texts, ix. 33 f.; xiii. 10-13 and xix. 28 contain no anti-Jewish criticisms at all. xi. 16-24;

xxi. 12-16; xxii. 1—14 and xxiii. 37-9 are certainly criticisms against the Jews, but these criticisms

are not made in contrast with the Gentiles. Matthew criticizes the Jews rather from the standpoint

of the Church elected from the Jewish people. In xv. 21-8 it is a matter of the Gentiles as in viii. 5-13,

but just as in the latter text the faith of the Gentile is here recognized as an exception.

6

In addition, x. 18 and xxiv. 14 can be considered to reflect in one sense or other the conscious-

ness of the Gentile mission.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

162 KENZO TAGAWA

the Gentile mission, his idea is clearly that the Gentiles become members of

the community of 'Israel' by becoming Christians. They will also be con-

stituents of'a nation that yields the proper fruits' (xxi. 43). Accordingly we

can understand the meaning of the f&rerb uoc9r|TEUEiv (make disciples) in

xxviii. 19 also in this light.1 They will be members of this holy people and

become disciples (iaa0r|Teuea6ai, cf. xiii. 52) living under the Law. To state

the conclusion, the Gentile mission in the true meaning of this expression is

not thought of in the Gospel according to Matthew. The Gentile mission in

Matthew is the mission in order to introduce the Gentiles into the Israel-

Christian community. For Matthew there can be no Gentile church.

It is the identification of Israel and the Christian community discussed

above, Matthew's undifferentiated community consciousness, which gives us

an important key for understanding the thought of the evangelist.2

1

Cf. the excellent analysis of this word by G. Bornkamm, op. cit. pp. 182 f. and p. 187.

8

This paper was written in May 1967.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 03 May 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

You might also like

- Luke : 2 Volumes (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From EverandLuke : 2 Volumes (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- 1 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From Everand1 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- 2 Corinthians (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From Everand2 Corinthians (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- New Testament Theology: Magnifying God in ChristFrom EverandNew Testament Theology: Magnifying God in ChristRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Jude and 2 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From EverandJude and 2 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- James (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From EverandJames (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Chapter Five: The Problem Op Sensus PlensorDocument24 pagesChapter Five: The Problem Op Sensus PlensorFreed Nixon0% (1)

- Magnifying God in Christ: A Summary of New Testament TheologyFrom EverandMagnifying God in Christ: A Summary of New Testament TheologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Divine Wrath and Salvation in Matthew: The Narrative World of the First GospelFrom EverandDivine Wrath and Salvation in Matthew: The Narrative World of the First GospelRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- 1 Tim 2.15 - Saved by ChildbirthDocument17 pages1 Tim 2.15 - Saved by Childbirth31songofjoyNo ratings yet

- Gideon Bohak Babylonian Jewish Magic in PDFDocument54 pagesGideon Bohak Babylonian Jewish Magic in PDFskaufmanhucNo ratings yet

- Hebrew LanguageDocument16 pagesHebrew LanguageJay RonssonNo ratings yet

- Law Righteousness and Discipleship in Matthew PDFDocument8 pagesLaw Righteousness and Discipleship in Matthew PDFBillybhNo ratings yet

- Matthews Use OT 1964-1 (Rev. Norman Hillyer)Document15 pagesMatthews Use OT 1964-1 (Rev. Norman Hillyer)Alberto PérezNo ratings yet

- The Roman Catholic Church and Its Recognition of the Validity of Baptism in the Name of Jesus (Acts 2:38) from 100 A.D. to 500 A.D.From EverandThe Roman Catholic Church and Its Recognition of the Validity of Baptism in the Name of Jesus (Acts 2:38) from 100 A.D. to 500 A.D.No ratings yet

- Peterh. Davids, St. Stephens University, St. Stephen, Nbe3L 1T3, CanadaDocument3 pagesPeterh. Davids, St. Stephens University, St. Stephen, Nbe3L 1T3, Canadafarax1720No ratings yet

- Biblical Inerrancy Accroding To RatzingerDocument111 pagesBiblical Inerrancy Accroding To RatzingersssdddkkkNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument35 pagesRetrieverickNo ratings yet

- SKARSAUNE OSKAR Them 199410 Heresy and The Pastoral EpistlesDocument14 pagesSKARSAUNE OSKAR Them 199410 Heresy and The Pastoral Epistlesivory2011100% (1)

- Theology & Res. - Metaphors and ParadigmsDocument19 pagesTheology & Res. - Metaphors and ParadigmsJodie BarryNo ratings yet

- New Dictionary of Theology: The EditorDocument4 pagesNew Dictionary of Theology: The EditorAkhoiNo ratings yet

- John P. Meier (1977) - Two Disputed Questions in Matt 28.16-20. Journal of Biblical Literature 96.3, Pp. 407-424Document19 pagesJohn P. Meier (1977) - Two Disputed Questions in Matt 28.16-20. Journal of Biblical Literature 96.3, Pp. 407-424Olestar 2023-06-22No ratings yet

- Barth 01Document16 pagesBarth 01Gabriel LopezNo ratings yet

- Grant Osborne Hermeneutics and Women in The ChurchDocument17 pagesGrant Osborne Hermeneutics and Women in The Churchhasiholannbbn03No ratings yet

- No They Are Not Crazy A Look at Prophecy PDFDocument18 pagesNo They Are Not Crazy A Look at Prophecy PDFBorisNo ratings yet

- The Curious Case of The Analogia EntisDocument16 pagesThe Curious Case of The Analogia EntisakimelNo ratings yet

- Eson Gumban - Matthew 16Document26 pagesEson Gumban - Matthew 16Gear John TigerNo ratings yet

- The Mystery of The Kingdom of GodDocument19 pagesThe Mystery of The Kingdom of GodDavide Varchetta100% (1)

- Revelation and Violence, A Study in Contextualization - Walter Brueggemann (1986, Marquette University Press)Document79 pagesRevelation and Violence, A Study in Contextualization - Walter Brueggemann (1986, Marquette University Press)atila-4-everNo ratings yet

- Matt 5-1-12 ExegesisDocument19 pagesMatt 5-1-12 ExegesisSid Sudiacal100% (6)

- Final Exam Study QuestionsDocument2 pagesFinal Exam Study QuestionsIoan LeonteNo ratings yet

- Roger Corless - Why Are There Monks and NunsDocument6 pagesRoger Corless - Why Are There Monks and NunsTiberiu OprisNo ratings yet

- V5-1 7 BellezaDocument28 pagesV5-1 7 BellezaDaniel FernandesNo ratings yet

- WONG - Matthean Understanding of SabbathDocument17 pagesWONG - Matthean Understanding of SabbathlaszlogalluszNo ratings yet

- New Testament Theology: An IntroductionFrom EverandNew Testament Theology: An IntroductionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Issues in New Testament Theology PDFDocument96 pagesIssues in New Testament Theology PDFrajivkarunNo ratings yet

- Course DescriptionDocument13 pagesCourse Descriptionlongdeal mzaziNo ratings yet

- Matthew's Mission Bracketology: Christ's Mission in The New CovenantDocument7 pagesMatthew's Mission Bracketology: Christ's Mission in The New CovenantChad Richard BressonNo ratings yet

- Fulfillment Quotations Introduction: Chapter 1Document13 pagesFulfillment Quotations Introduction: Chapter 1mertoos100% (1)

- Dirt, Greed and Sex: Sexual Ethics in the New Testament and their Implications for TodayFrom EverandDirt, Greed and Sex: Sexual Ethics in the New Testament and their Implications for TodayRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Instruction On Scripture and ChristologyDocument27 pagesInstruction On Scripture and ChristologyAlbertus Widya Rahmadi PutraNo ratings yet

- 21 Questions On Doctrine of ScriptureDocument90 pages21 Questions On Doctrine of ScriptureNick_MaNo ratings yet

- Snoptic Gosple11Document28 pagesSnoptic Gosple11Julius AliNo ratings yet

- Barth and TextualityDocument17 pagesBarth and TextualityMitrache MariusNo ratings yet

- Aquinas on Israel and the Church: The Question of Supersessionism in the Theology of Thomas AquinasFrom EverandAquinas on Israel and the Church: The Question of Supersessionism in the Theology of Thomas AquinasNo ratings yet

- Hermeneutic CircleDocument8 pagesHermeneutic CirclecisjrNo ratings yet

- Bokedal, Jansen, Borowski, Scripture and Theology in ContextDocument32 pagesBokedal, Jansen, Borowski, Scripture and Theology in ContextMichael MettsNo ratings yet

- Steinmetz Superiority of Precritical ExegesisDocument13 pagesSteinmetz Superiority of Precritical Exegesisrjbarryiv100% (2)

- Evangelical Hermeneutics - Robert L. Thomas (PDFDrive)Document584 pagesEvangelical Hermeneutics - Robert L. Thomas (PDFDrive)suwartono hasardjo100% (2)

- The Pentateuch: Interpreting Biblical Texts SeriesFrom EverandThe Pentateuch: Interpreting Biblical Texts SeriesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (8)

- Iberty NiversityDocument87 pagesIberty NiversityElías E. HerediaNo ratings yet

- Chapter TenTHE SUFFICIENCY OF TRADITION AND SCRIPTURE PDFDocument24 pagesChapter TenTHE SUFFICIENCY OF TRADITION AND SCRIPTURE PDFSalah ElbassiouniNo ratings yet

- The Future of Biblical Interpretation: Responsible Plurality in Biblical HermeneuticsFrom EverandThe Future of Biblical Interpretation: Responsible Plurality in Biblical HermeneuticsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Anders On TraditionDocument4 pagesAnders On TraditionnoquierodarinforNo ratings yet

- The Office of Peter: And the Structure of the ChurchFrom EverandThe Office of Peter: And the Structure of the ChurchNo ratings yet

- The Disputed Teachings of Vatican II: Continuity and Reversal in Catholic DoctrineFrom EverandThe Disputed Teachings of Vatican II: Continuity and Reversal in Catholic DoctrineNo ratings yet

- The Synoptic Problem: A HomeworkDocument6 pagesThe Synoptic Problem: A HomeworkGinoSDBNo ratings yet

- Understanding Jewish InfluenceDocument118 pagesUnderstanding Jewish InfluenceVictoriaGiladNo ratings yet

- Congregation Yeshuat Yisrael Franklin, TennesseeDocument50 pagesCongregation Yeshuat Yisrael Franklin, TennesseeDaniel Malic100% (1)

- Greenberg PDFDocument9 pagesGreenberg PDFAislingNo ratings yet

- Inheritance Rights of Women Under Jewish and Islamic LawDocument38 pagesInheritance Rights of Women Under Jewish and Islamic Lawאליעזר קופערNo ratings yet

- Rosh Hashanah 27Document38 pagesRosh Hashanah 27Julian Ungar-SargonNo ratings yet

- Studies of Religion Past HSC QuestionsDocument21 pagesStudies of Religion Past HSC QuestionsMesina StantzosNo ratings yet

- Religious Studies Form 1 Notes Term 1 2024Document14 pagesReligious Studies Form 1 Notes Term 1 2024elasahmadizNo ratings yet

- Harnack A. - Marcion. The Gospel of The Alien GodDocument186 pagesHarnack A. - Marcion. The Gospel of The Alien GodDomenico CatalanoNo ratings yet

- Fulfillment of The LawDocument169 pagesFulfillment of The LawRobbert Adrianus Veen100% (2)

- IBMP Schedule Winter 2011Document2 pagesIBMP Schedule Winter 2011yehoshuadovidNo ratings yet

- James 2 1-13Document7 pagesJames 2 1-13richard5049No ratings yet

- General InterestDocument281 pagesGeneral InterestKhoo Beng Kiat100% (4)

- Furukawa Unic Hydraulic Crane CD PDF CollectionDocument23 pagesFurukawa Unic Hydraulic Crane CD PDF Collectionmikaylakelly141196atp100% (101)

- Understanding Christian Zionism - Paul WilkinsonDocument354 pagesUnderstanding Christian Zionism - Paul WilkinsonRaymond WilfongNo ratings yet

- Midrash Sobre o Mashiach Scr-Páginas-101-200 PDFDocument100 pagesMidrash Sobre o Mashiach Scr-Páginas-101-200 PDFshilomobenavrahamNo ratings yet

- Mystical Book RecommendedDocument2 pagesMystical Book Recommendedjeryon91No ratings yet

- Henry George and Zionism - Jewish CurrentsDocument5 pagesHenry George and Zionism - Jewish Currentst7v6kkfvbhNo ratings yet

- 37 Graves of The RighteousDocument28 pages37 Graves of The Righteouskevinj_jNo ratings yet

- Understanding Hashem's Ways: Volume XII - Issue 15 The DRS Weekly Torah PublicationDocument12 pagesUnderstanding Hashem's Ways: Volume XII - Issue 15 The DRS Weekly Torah Publicationoutdash2No ratings yet

- 10.the Esoteric and Inter-Religious Aspects of The Relation Philosophy - Kabbalah in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe - Yossef SchwartzDocument18 pages10.the Esoteric and Inter-Religious Aspects of The Relation Philosophy - Kabbalah in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe - Yossef Schwartzgtnlmnc99235No ratings yet

- Christianity NotesDocument10 pagesChristianity NotesKelvin kinyuaNo ratings yet

- CHRISTIANITYDocument28 pagesCHRISTIANITYSophia Dapigran Alcido100% (1)

- Lurianic Kabbalah: Unit 1: Introduction: Kabbalah Before and After The Expulsion From SpainDocument17 pagesLurianic Kabbalah: Unit 1: Introduction: Kabbalah Before and After The Expulsion From SpainAnonymous XSixrIuNo ratings yet

- Shulkhan Arukh ShabbatDocument493 pagesShulkhan Arukh ShabbatEdiciones YojévedNo ratings yet

- Hanukkah TriviaDocument5 pagesHanukkah TriviastavtiNo ratings yet

- Nietzsche S Jewish Problem Between Anti-Semitism and Anti-Judaism by Robert HolubDocument6 pagesNietzsche S Jewish Problem Between Anti-Semitism and Anti-Judaism by Robert HolublollipopfactorialNo ratings yet

- 2017 Taubman LecturesDocument1 page2017 Taubman LecturesmagnesmuseumNo ratings yet

- June-July 2008 Tidings Newsletter, Temple Ohabei ShalomDocument12 pagesJune-July 2008 Tidings Newsletter, Temple Ohabei ShalomTemple Ohabei ShalomNo ratings yet