Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tridemnsional Personality and Pain

Tridemnsional Personality and Pain

Uploaded by

Satpal SandhuOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tridemnsional Personality and Pain

Tridemnsional Personality and Pain

Uploaded by

Satpal SandhuCopyright:

Available Formats

European Journal of Pain 8 (2004) 3138 www.EuropeanJournalPain.

com

The tridimensional personality theory and pain: harm avoidance and reward dependence traits correlate with pain perception in healthy volunteers

Dorit Pud

a,b,c,*

, Elon Eisenberg a,b,d, Elliot Sprecher David Yarnitsky b,e,d

a

b,d

, Zeev Rogowski

b,d

Pain Relief Unit, Rambam Medical Center, Haifa, Israel b Haifa Pain Research Group, Israel Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Studies, University of Haifa, Haifa 31905, Israel d The Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Israel e Department of Neurology, Rambam Medical Center, Israel Received 2 September 2002; accepted 26 May 2003

Abstract The aim of the present study was to examine the possible role of personality traits in determining the variability of pain perception among individuals. More specically, it was intended to test whether or not the three personality dimensions suggested by Cloninger in 1987 mainly harm avoidance (HA), but also reward dependence (RD), and novelty seeking (NS), can predict interpersonal dierences in responsiveness to experimental pain. Seventy healthy volunteers participated in the study. Their personality traits were evaluated through Cloningers tridimensional personality questionnaire (TPQ). Pain threshold (latency to pain onset), pain magnitude (VAS), and pain tolerance (time to withdrawal) were measured by using the cold pressor test. Bonferroniadjusted correlations were found between HA and the pain parameters as follows: a negative correlation between HA and threshold (q 0:297, Padj 0:039); no signicant correlation between HA and tolerance (q 0:219, Padj 0:207); and a trend for a positive correlation between HA and VAS (q 0:266, Padj 0:081). Possible correlations between pain perception and the various possible combinations of high and low scoring for each of the three traits were also investigated. Correlations were found only for the combinations of high/low HA and high/low RD. The low HA/low RD combination demonstrated the lowest responsiveness to pain (VAS 65.2 21.4; tolerance 107.6 71.8 s), whereas the high HA/low RD combination was correlated with the highest responsiveness (VAS 83.3 10.8; tolerance 30.8 28.4 s). The results indicate that HA personality trait correlates best with pain responsiveness. As such, a high HA are likely to predict a heightened pain response. RD may modify this pattern. The possible relevant behavioral and neuro-chemical mechanisms are discussed. 2003 European Federation of Chapters of the International Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Cold pressor test; Pain magnitude; Pain threshold; Pain tolerance; Personality traits; Tridimensional personality theory

1. Introduction There are large individual dierences in the perception of clinical and experimental pain, in the propensity to develop painful syndromes, and in the response to pain-relieving treatments. Experimental pain studies show a wide range of stimulusresponse relations

*

Corresponding author. Tel.: +972-4-8288013; fax: +972-4-8288017. E-mail address: doritpud@research.haifa.ac.il (D. Pud).

between the intensity of the noxious stimulus and the reported magnitude of pain perception (Mogil, 1999a). Furthermore, considerable interpersonal variability in pain thresholds has been demonstrated for pressure pain (Brennum et al., 1989; Isselee et al., 1997), cold pressor tolerance (Chen et al., 1989), and heat pain (Kleinbohl et al., 1999; Yarnitsky et al., 1995, 1996). Much eort has been invested over the years in an attempt to identify factors predicting pain perception. Although the results have not always been consistent,

1090-3801/$30 2003 European Federation of Chapters of the International Association for the Study of Pain. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/S1090-3801(03)00065-X

32

D. Pud et al. / European Journal of Pain 8 (2004) 3138

several factors have been found to correlate with different pain parameters. First, most clinical trials have found gender-dependent dierences in pain perception, with women reporting more intense, prolonged and frequent pain than men (Fillingim and Maixner, 1995; Keefe et al., 2000; Riley et al., 1998; Unruh, 1996). Experimental pain studies, on the other hand, have been less consistent regarding gender dierences in pain perception, depending partially on the pain modality used (Fillingim et al., 1997; Lautenbacher and Strain, 1991; Lautenbacher and Rollman, 1993). Second, high anxiety levels have been found to correlate with post-operative pain magnitude (Thomas et al., 1998), labor pain (Green, 1993), and experimental pain induced by electrical stimulation (Janssen and Arntz, 1999). Third, cultural background has been shown to inuence the response to experimental and acute pain (see the review by Williams, 1999). Fourth, pain perception has been shown to be associated with autonomic activity, as reected in the association between increased arterial blood pressure and decreased perception of pain (alAbsi et al., 1999; Ditto et al., 1993; Ghione et al., 1988; Zamir and Shuber, 1980). Finally, recent animal studies have demonstrated the inuence of genetic factors on pain perception (Mogil et al., 1999b; Mogil, 1999c). An area of great interest in this context is the role of personality traits in pain perception. Personality traits are dened as deeply ingrained patterns of behaviors, which include the way one relates to, perceives, and thinks about the environment and oneself that are exhibited in a wide range of social and personal contexts (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Since pain is widely accepted to be a bio-psychosocial process (Turk, 1996), it is very likely to be inuenced by personality. Over the years, researchers have investigated the contribution of personality to pain perception, both through experimentally induced pain models as well as in various clinical settings. The dierent parameters measured include pain threshold, pain magnitude, tolerance, and pain behavior. Still, ndings are inconsistent and the relationship between personality and the various pain parameters remains unclear (Phillips and Gatchel, 2000). A unique personality theory that appears to make a great contribution to the understanding of psychiatric disorders is Cloningers tridimensional personality theory (Cloninger, 1986, 1987; Hansenne et al., 1998; Nelson and Cloninger, 1997; Russo et al., 1994). This theory is derived from the unied bio-social model of personality and is based on the hypothesis that neuro-chemical transmitters determine stimulusresponse characteristics. Accordingly, three sets of behavioral manifestations and their corresponding neuro-transmitters are hypothesized: (1) Novelty seeking (NS), described as a tendency to respond with intense excitement to novel stimuli, leading to pursuit of rewards and escape from

punishment. This trait is associated with dopamine. (2) Harm avoidance (HA), dened as a tendency to respond intensely to previously established signals of aversive stimuli and to learn to passively avoid punishment, novelty and frustrating non-reward. This trait is associated with serotonin. (3) Reward dependence (RD), characterized as a tendency to respond intensely to signals of reward and to maintain behavior previously associated with reward or with relief of punishment. This trait is associated with noradrenaline. This theory is assumed to have relevance for pain perception given that serotonin and noradrenaline are the major neurotransmitters in the inhibitory modulation of pain through descending pathways (Fields and Basbaum, 1999). Dopamine may also be involved in pain processing, as suggested by the painful syndromes described in Parkinsonian patients (Chudler and Dong, 1995). Furthermore, behaviors along the lines delineated by the Cloninger theory may correspond to pain-related behavior. For example, avoidance of harm is probably equivalent to avoidance of pain, so that high scores on harm avoidance would likely produce relatively high scoring of painful stimuli. The aim of our study was to examine the possible role of personality traits in explaining the variability of pain perception among individuals. Specically, we attempted to identify the relationships between personality traits and the parameters of pain threshold, tolerance and magnitude estimation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the rst attempt to implement Cloningers theory in the context of pain perception. Our working hypothesis was that individuals with high HA scoring, who are nearly always fearful and anticipating harm, pessimistic and inhibited by unfamiliar situations, would probably express high pain response. We assumed that the other two dimensions will not, by themselves, predict pain perception; NS because of the unpredictability of the individual response, and RD because of their heavy inconsistency and dependence on circumstances.

2. Method 2.1. Subjects Seventy healthy volunteers participated in the study at Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, Israel. The study included 38 male and 32 female subjects, with ages ranging from 18 to 40 years (mean 24.3 3.9, SD). The volunteers were recruited mostly from the student body of the medical and nursing schools, and enrolled in the study after meeting the following criteria: (1) freedom from chronic pain of any type; (2) no use of any medication (except oral contraceptives); and (3) ability to understand and follow the instructions of the study. All subjects were paid for participating the study. A written

D. Pud et al. / European Journal of Pain 8 (2004) 3138

33

informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to beginning the study. The study protocol was approved by the hospitals Ethics Committee and the National Board of Health in Israel. 2.2. Instruments 2.2.1. Personality trait evaluation The tridimensional personality questionnaire (TPQ) is a 100-item true/false self-report inventory (Cloninger, 1987). It has been translated into several languages and used in a variety of studies. The questionnaire has been translated into Hebrew, and this versions reliability was demonstrated by high Cronbachs alpha (0.90 for NS, 0.89 for HA, and 0.85 for RD) (Gil, 2003). Nixon and Parsons (1989) provided evidence for the construct validity of the questionnaire in a sample of 225 male and female college students. They analyzed scores for each personality dimension with respect to gender, academic major, college GPAs, and abstraction test scores. Their results support Cloningers theoretical concept of three essentially independent personality dimensions. This instrument measures the three primary personality factors thought to be involved in the mediation of particular types of stimuli, with 34 questions relating to NS, another 34 questions to HA, and 30 questions to RD (Cloninger et al., 1991). Two questions (No. 61 and 71) were excluded from scoring because of non-specicity (correlations with multiple factors) (Cloninger, 1987). Testretest correlations were found to be moderately high (Cloninger et al., 1991). The total score for each dimension was calculated. 2.2.2. Experimental cold tonic pain The cold pressor test (CPT) apparatus (Heto CBN 8-30 Lab equipment, Allerod, Denmark) is a temperature-controlled water bath of 1.0 C, with a maximum temperature variance of 0.5 C, that is continuously stirred by a pump. 2.3. Study protocol All subjects completed the Hebrew version of the TPQ. As for the cold pressor test, following the standard protocol (see e.g., Wol, 1984), subjects were asked to place their non-dominant hand in the CPT bath in a still position with the ngers wide apart for as long as they could. A cut-o time of 3 min was set for safety reasons. This initial immersion was considered training or familiarization, and the results were not used in the statistical analysis. Thirty minutes later, a second CPT immersion was conducted in the same manner and regarded as the baseline measure. Subjects were instructed to indicate the exact point in time when the cold sensation began to hurt, and they rst felt pain. This was dened as the pain threshold.

The latency to intolerability (spontaneous hand removal) was dened as pain tolerance. Tolerance for subjects that did not withdraw their hand for the entire 180 s was recorded as 180 s. Immediately after withdrawing their hand, subjects were asked to mark on a 100 mm VAS ruler the maximal pain intensity they experienced during the cold stimulus. The VAS was dened a priori to the subjects as a continuum with one anchor at 0, representing no pain at all, and the other anchor at 100, representing the worst pain one can imagine. This mark was dened as the pain magnitude. 2.4. Statistical analysis Statistical analysis employed ANOVA, linear regression and Spearman correlations (q indicates Spearman correlation). ShapiroWilk tests were used to examine the deviation of result distributions from normality. Arcsine, log, or square root transformations (Zar, 1984) were employed as needed to improve the normality of result distributions and to enable the use of ANOVA. Excel (Microsoft Corp., WA, USA), JMP, and SAS (SAS Institute, NC, USA) were employed in the statistical analyses. Results were considered signicant at the 0.05 levels; if multiple tests were required, raw P values were Bonferroni-adjusted appropriately. All results are given as means SD.

3. Results 3.1. Personality traits Analysis of the 70 TPQ questionnaires from the present study showed a NS mean score of 16.4 4.4; an HA mean score of 9.6 5.6; and a RD mean score of 19.2 4.7. 3.2. Pain perception The results demonstrate that exposure to the CPT produced signicant pain, as measured by the three dierent variables of threshold, tolerance, and magnitude (see Table 1), without causing any harm to the subjects. These results are in line with those reported in previous studies (Cleeland et al., 1996; Eckhardt et al., 1998; Fromm et al., 1997; Garcia de-Jalon et al., 1985; Jones et al., 1988; Lovallo, 1975; Peckerman et al., 1994; Poulsen et al., 1995). Results of the CPT are as follows. 3.2.1. Threshold Mean threshold was 7.1 4.5 s, ranging from 1 to 24 s (see Fig. 1A). Since the distribution of threshold among subjects was not normal, a log transformation was used for normalization, as conrmed by the ShapiroWilk test (P 0:279).

34

D. Pud et al. / European Journal of Pain 8 (2004) 3138

Table 1 Pain parameters in response to CPT (n 70) Threshold (s) (THRE) Mean SD Median Range 7.1 4.5 6 124 Tolerance (s) (TOL) 54.8 46.9 38 6180 VAS (0100) 72.8 15.8 73 20100

3.2.2. Tolerance Mean tolerance was 54.8 46.9 s, ranging from 6 to 180 s (see Fig. 1B). About two-thirds of the subjects demonstrated high sensitivity to cold stimuli and could tolerate the pain for no more than 60 s. The others were found to be more tolerant to cold pain and could keep their hands in the water for a longer time. This distribution is similar to previously published data (Chen et al., 1989; Cleeland et al., 1996). The distribution of this data was not normal, and no conventional transformation technique was able to normalize it. 3.2.3. Pain magnitude Mean VAS was 72.8 15.8, ranging from 20 to 100 (see Fig. 1C). Since the distribution of pain magnitude among subjects was not normal, the arcsine transformation was successfully used for normalization, as conrmed by the ShapiroWilk test (P 0:755). Spearman correlations, on untransformed data, for non-parametric variables found a signicant positive correlation between threshold and tolerance (q 0:622, P < 0:0001) and negative correlations between VAS and tolerance (q 0:218, P 0:038), as well as between VAS and threshold (q 0:208, P 0:048). 3.3. Relationship between personality traits and pain perception In order to avoid statistical problems with non-normal distributions and outlying data, we performed three Spearman correlations, relating the HA scores separately to each of the three pain measures. Raw P values were Bonferroni-adjusted by multiplication by 3. Correlations were found between HA and the pain parameters as follows: a negative correlation between HA and threshold (q 0:297, P 0:013, Padj 0:039) (see Fig. 2A); no signicant correlation between HA and tolerance (q 0:219, P 0:069, Padj 0:207) (see Fig. 2B); and a trend for a positive correlation between HA and VAS (q 0:266, P 0:027, Padj 0:081) (Fig. 2C). Thus, individuals with high HA scores demonstrated enhanced sensitivity to painful stimuli, as expressed by a low pain threshold and increased pain perception. In a separate analysis, NS and RD failed to demonstrate signicant correlations with any of the pain parameters. A further analysis using linear regression on transformed data indicated that, when taken together, HA and RD demonstrated a trend toward a correlation with

pain magnitude (P 0:084). The other combinations of the personality traits (HA and NS; NS and RD) failed to show correlations with any pain parameter. Consequently, the subjects were then categorized into two dierent groups for each trait, with the mean point score delineated as the cut-o point. A mean rather than median was used, in order to follow as closely as possible the original report by Cloninger (1987). Thus, six dierent subgroups (high score and low score for each trait) were created. This was followed by a pairing of the traits (e.g., HA and RD) so as to produce three 2 2 cross-tabulations (e.g., high and low HA vs. high and low RD). For the HA/RD interaction, we found that the low HA/low RD group demonstrated the lowest pain magnitude (VAS 65.2 21.4), whereas high HA/low RD showed the highest pain magnitude (VAS 83.3 10.8). The other two groups (low HA/high RD and high HA/

Fig. 1. Threshold (A), tolerance (B), and magnitude (C) of pain in response to CPT.

D. Pud et al. / European Journal of Pain 8 (2004) 3138

35

Analysis of HA vs. NS and of RD vs. NS, using the same methodology, failed to show any signicant results.

4. Discussion The ndings of the present study suggest that personality traits can play an important role in the understanding of the variability of pain perception among individuals in pain perception. More specically, they indicate that the personality traits described by Cloninger may predict responsiveness to cold-induced experimental pain. High HA level alone and even more so a combination of high HA and low RD seems to be the most important traits in the determination of heightened cold pain perception. Clinically, Cloningers model has been the basis for a large number of studies on various psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety disorders, and suicidal behavior (Gil, 2003; Hansenne et al., 1998; Herran and Vazquez, 1998; Nelson and Cloninger, 1997; Starcevic et al., 1996). Hansenne et al. (1998) demonstrated higher harm avoidance scores and lower novelty seeking scores among depressed patients as compared to healthy controls. Gil (2003) found that psychiatric patients characterized by high levels of both HA and NS are at greater risk for suicide attempt. Menza et al. (1993) found low scores for the novelty-seeking trait, which represents dopaminergic activity, among Parkinsons patients as compared to a group of other orthopedic patients with motor disturbances. Possible relations between personality traits and pain perception have been discussed by several earlier writers. A common theoretical perspective used to examine personality was proposed by Eysenck (1960), who divided personality into two main independent, uncorrelated factors: extroversionintroversion and neuroti cism-stability. He dened extroverted people as more outgoing, uninhibited and socially active, whereas introverts were considered to be quieter, more introspective and reserved. In examining the relationship between personality and experimental heat pain, Lynn and Eysenck (1961) found higher tolerance among extroverted subjects, whereas other researchers (Brown et al., 1973; Martin and Inglis, 1965) using the cold pain model failed to report a signicant relationship. As for clinical pain, Bond et al. (1976) found higher pain magnitude among extroverted patients suering from back surgery pain, whereas Taenzer et al. (1986) found no correlation between personality dimensions and post-operative gallbladder pain. It should be mentioned that pain assessment was performed by dierent methodologies in dierent studies and that the personality questionnaire was not always completed at the same point in time, which may account for conicting results.

Fig. 2. Scatter plots of correlations between threshold (A), tolerance (B), and pain magnitude (C), and HA scores. The P value for each Spearman correlation has been Bonferroni-adjusted for the three comparisons.

high RD) were in-between (VAS 73.6 15.1 and 73.2 14.3) (see Fig. 3). ANOVA on the transformed data indicated that this dierence was statistically signicant (P 0:026). The same pattern was found in regard to pain tolerance. The low HA/low RD group demonstrated the longest tolerance (107.6 71.8 s), whereas the high HA/ low RD group showed the shortest tolerance (30.8 28.4 s). Here too, the other two groups were inbetween (54.4 42.9) and (51.6 46.4), with statistical signicance at the P 0:002 level. Likewise, regarding pain threshold, the low HA/low RD group demonstrated the longest threshold (7.3 4.6 s), whereas the high HA/low RD group showed the shortest threshold (5.2 3.2 s). The other two groups were in-between (6.9 4.1 and 7.0 3.2 s). ANOVA indicated only a trend toward signicance for this variable (P 0:083).

36

D. Pud et al. / European Journal of Pain 8 (2004) 3138

Fig. 3. Pain perception in the four subgroups based on combined HA and RD scores. Highest pain perception (dark gray) in high HA/low RD subgroup; lowest pain perception (white) in low HA/low RD subgroup, and intermediate perception in the other two subgroups (light gray).

According to the results of the present study, individuals with a high score of HA in combination with a low score of RD appear to be the most responsive to pain, whereas those with a low score of HA and a low score of RD appear to be the least responsive to pain. The principal factor that seems to determine pain perception is the scoring of HA. HA individuals tend to be fearful and anticipate harm even under supportive circumstances, are typically pessimistic and inhibited by unfamiliar situations, and generally avoid taking risks. High scores on this trait seem to predict high pain perception, as reected in our results showing higher pain perception in high HA volunteers. According to Cloningers theory, individuals with low RD scores are typically independent and non-conformist, socially detached, unwilling to share their intimate feelings with others, content to be alone, cynical and insensitive to social cues and pressures, and only minimally motivated to please others. It may be that low RD serves to unmask pain behavior from possible social and cultural biases, thereby allowing the HA trait to emerge as a net expression. Thus, Cloningers suggested traits do indeed seem to be relevant to pain perception. However, further studies are needed to support these preliminary ndings.

In parallel to this psychological rationale, a neurochemical explanation can also be formulated, although facing the complexity of personality and behavior, relating the latter to measures such as levels of specic neurotransmitters might be an oversimplication of these mechanisms. Several studies have examined the relations between the Cloninger personality dimensions in healthy volunteers and brain neurotransmitters. Hansenne and Ansseau (1999) found a relationship between harm avoidance scores and serotonin by showing a correlation between HA scores and prolactin response to intra-venous Flesinoxan (5-HT1A agonist) in healthy volunteers. Garvey et al. (1996) demonstrated a positive correlation between urinary noradrenaline metabolite level (HMPG) and reward dependence scores. Gerra et al. (2000) demonstrated positive correlations between each specic personality trait (NS, HA, and RD) and dopaminergic, serotonergic and noradrenergic functions in healthy subjects by challenging the monoamine systems with specic agonists (bromocriptine, D -fenuramine, and clonidine, respectively). These ndings support the suggested relations between neurotransmitters and personality traits, as proposed by Cloninger. The neuro-chemical explanation for our ndings points to serotonin as the main neurotransmitter. We

D. Pud et al. / European Journal of Pain 8 (2004) 3138

37

suggest that the level of serotonin determines the basic perception of pain. Accordingly, higher levels of serotonin predict high pain responsiveness and vice versa. Serotonin serves as the main neurotransmitter in the descending pain inhibitory pathways (Fields and Basbaum, 1999). As such, one would expect high levels of serotonin to express a higher degree of inhibition, resulting in less pain. Our results, however, indicate higher pain responsiveness in high HA subjects. A possible explanation relates to the model suggested by Liu et al. (2000). According to this model, brainstem interneurons in the periaqueductal greydorsal raphe nucleus (PAGDRN) complex exert serotoninergic inhibition upon the raphe serotoninergic neurons. The latter send their axons down the spinal cord and inhibit pain messages at their entrance to the cord. Thus, a disinhibition eect will cause an overall heightened pain perception in these subjects. In conclusion, the present study demonstrates a relationship between personality traits and pain perception in response to cold stimuli. These ndings may contribute to our understanding of the possible mechanisms underlying individual dierences in pain perception. The results may also indicate that Cloningers tridimensional personality theory can be used as a tool for improving pain management. The identication of specic personality traits that can predict pain perception will facilitate the design of individually tailored pain management plans.

Acknowledgements The study was supported by the Israel Cancer Association, through the Raya (Rela) Golambo Memorial Fund Grant No. 20000009-c.

References

alAbsi M, Buchanan TW, Marrero A, Lovallo WR. Sex dierences in pain preception and cardiovascular responses in persons with parental history for hypertension. Pain 1999;83:3318. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. Bond MR, Glynn JP, Thomas DG. Relation between pain and personality in patients receiving pentazocine (Fortral) after surgery. J Psychosom Res 1976;20:36981. Brennum J, Kjeldsen M, Jensen K, Jensen TS. Measurements of human pressure-pain thresholds on ngers and toes. Pain 1989;38:2117. Brown RA, Fader K, Barber TX. Responsiveness to pain: stimulus specicity versus generulity. Psychol Rec 1973;23:17. Chen ACN, Dworkin SF, Haug J, Gehrig J. Human pain responsivity in a tonic pain model: psychological determinants. Pain 1989;37:14360. Chudler EH, Dong WK. The role of the basal ganglia in nociception and pain. Pain 1995;60:338.

Cleeland CS, Nakamura Y, Howland EW, Morgan NR, Edwards KR, Backonja M. Eects of oral morphine on cold pressor tolerance time and neuropsychological performance. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996;15:25262. Cloninger CR. A unied biosocial theory of personality and its role in the development of anxiety states. Psychiatr Dev 1986;3:167226. Cloninger CR. A systemic method for clinical description and classication of personality variants. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987;44:57387. Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM. The tridimensional personality questionnaire: U.S. normative data. Psychol Rep 1991;69:104757. Ditto B, Edwards MC, Miller S, DAntono B, Blum S. The eects of sodium loading on blood pressure and pain responses to the cold pressor test. J Psychosom Res 1993;37:77180. Eckhardt K, Li S, Ammon S, Schanzle G, Mikus G, Eichelbaum M. Same incidence of adverse drug events after codeine administration irrespective of the genetically determined dierences in morphine formation. Pain 1998;76:2733. Eysenck HJ. Structure of human personality. New York: Wiley; 1960. Fields HL, Basbaum AI. Central nervous system mechanisms of pain modulation. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of pain. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. p. 30930. Fillingim RB, Maixner W. Gender dierences in the response to noxious stimuli. Pain Forum 1995;4:20921. Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Girdler SS, et al. Iscemic but not thermal pain sensitivity varies across the menstrual cycle. Psychosom Med 1997;59:51220. Fromm MF, Eckhardt K, Li S, et al. Loss of analgesic eect of morphine due to coadministration of rifampin. Pain 1997;72:2617. Garcia de-Jalon PD, Jose-Harrison FJ, Johnson KI, Kozma C, Schnelle K. A modied cold stimulation technique for the evaluation of analgesic activity in human volunteers. Pain 1985;22:1839. Garvey MJ, Noyes Jr R, Cook B, Blum N. Preliminary conrmation of the proposed link between reward dependence traits and norepinephrine. Psychiatry Res 1996;65:614. Gerra G, Zaimovic A, Timpano M, Zambelli U, Delsignore R, Brambilla F. Neuroendocrine correlates of temperamentel traits in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2000;25:47996. Ghione S, Mezzasalma L, Panattoni E. Arterial hypertention is associated with hypalgesia in humans. Hypertension 1988;12:4917. Gil S. The role of personality traits in the understanding of suicide attempt behavior among psychiatric patients. Arch Suicide Res 2003;7:18. Green JM. Expectations and experiences of pain in labor: ndings from a large prospective study. Birth 1993;20:6572. Hansenne M, Pitchot W, Gonzalez-Moreno A, Machurot PY, Ansseau M. The tridimensional personality questionnaire (TPQ) and depression. Eur Psychiatry 1998;13:1013. Hansenne M, Ansseau M. Harm avoidance and serotonin. Biol Psychol 1999;51:7781. Herran A, Vazquez B. Personality dimensions, the TPQ and depression. Eur Psychiatry 1998;13:434. Isselee H, De-Laat A, Lesare E, Lysens R. Short-term reproducibility of pressure pain threshold in masseter and temporalis muscles of symptom-free subjects. Eur J Oral Sci 1997;105:5837. Janssen SA, Arntz A. No interactive eects of naltrexone and benzodiazepines on pain during phobic fear. Behav Res Ther 1999;37:7786. Jones SF, McQuay HJ, Moore RA, Hand CW. Morphine and ibuprofen compared using the cold pressor test. Pain 1988;34:117 22. Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Egert JR, Aeck G, Sullivan MJ, Caldwell DS. The relationship of gender to pain, pain behavior, and disability in osteoarthritis patients: the role of catastrophizing. Pain 2000;87:32534.

38

D. Pud et al. / European Journal of Pain 8 (2004) 3138 patients with pain. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American psychological association; 2000. p. 181202. Poulsen L, Arendt-Nielsen L, Brosen K, Nielsen KK, Gram LF, Sindrup SH. The hypoalgesic eect of imipramine in dierent human experimental pain models. Pain 1995;60:28793. Riley JL, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Myers CD, Fillingim RB. Sex dierences in the perception of noxious experimental stimuli: a meta-analysis. Pain 1998;74:1817. Russo J, Katon W, Sullivan M, Clark M, Buchwald D. Severity of somatization and its relationship to psychiatric disorders and personality. Psychosomatics 1994;35:54656. Starcevic V, Vhlenhuth EH, Fallon S, Patha K. Personality dimensions in panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. J Aect Disord 1996;37:759. Taenzer P, Melzack R, Jeans ME. Inuence of psychological factors on post-operative pain, mood and analgesic requirements. Pain 1986;24:33142. Thomas T, Robinson C, Champion D, McKell M, Pell M. Prediction and assessment of severity of post-operative pain and of satisfaction with management. Pain 1998;75:17785. Turk DC. Biopsychosocial perspective on chronic pain. In: Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, editors. Psychological approaches to pain management: a practitioners handbook. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. p. 334. Unruh AM. Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain 1996;65:12367. Williams DA. Acute pain with special emphasis on painful medical procedures. In: Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, editors. Psychosocial factors in pain: clinical perspectives. 1st ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. p. 15163. Wol BB. Methods of testing pain mechanisms in normal man. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of pain. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1984. p. 18694. Yarnitsky D, Sprecher E, Zaslansky R, Hemli JA. Heat pain thresholds: normative data and repeatability. Pain 1995;60:32932. Yarnitsky D, Sprecher E, Zaslansky R, Hemli JA. Multiple session experimental pain measurement. Pain 1996;67:32733. Zamir N, Shuber E. Altered pain perception in hypertensive humans. Brain Res 1980;201:4714. Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1984. p. 236242.

Kleinbohl D, Holzl R, Moltner A, Rommel C, Weber C, Osswald PM. Psychophysical measures of sensitization to tonic heat discriminate chronic pain patients. Pain 1999;81:3543. Lautenbacher S, Strain F. Sex dierences in pain and thermal sensitivity: the role of body size. Percept Psychophys 1991;50:17983. Lautenbacher S, Rollman GB. Sex dierences in responsiveness to painful and non-painful stimuli are dependent upon the stimulation method. Pain 1993;53:25564. Liu R, Thierry J, Aghajanian G. Serotonin 5-HT2 receptors activate local GABA inhibitory inputs to serotonergic neurons of the dorsal raphe nucleus. Brain Res 2000;87:33445. Lovallo W. The cold pressor test and autonomic function: a review and integration. Psychophysiology 1975;12:26882. Lynn R, Eysenck HJ. Tolerance for pain, extraversion and neuorotioism. Percept Mot Skills 1961;12:1612. Martin JE, Inglis J. Pain tolerance and narcotic addiction. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1965;4:2249. Menza MA, Golbe LI, Cody RA, Forman NE. Dopamine related personality traits in Parkinsons disease. Neurology 1993;43:5058. Mogil JS. The genetic mediation of individual dierences in sensitivity to pain and its inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999a;96:7744 51. Mogil JS, Wilson SG, Bon K, et al. Heritability of nociception I: responses of 11 inbred mouse strains on 12 measures of nociception. Pain 1999b;80:6782. Mogil JS. Individual dierences in pain: moving beyond the universal rat. Bulletin 1999c;9:123. Nelson E, Cloninger CR. Exploring the TPQ as a possible predictor of antidepressant response to nefazodone in a large multi-site study. J Aect Disord 1997;44:197200. Nixon SJ, Parsons OA. Cloningers tridimensional theory of personality: constract validity in a sample of college students. Pers Indiv Dier 1989;10:12617. Peckerman A, Hurwitz BE, Saab PG, Llabre MM, Mccabe PM, Schneiderman N. Stimulus dimensions of the cold pressor test and the associated patterns of cardiovascular response. Psychophysiology 1994;31:28290. Phillips JM, Gatchel RB. Extraversionintroversion and chronic pain. In: Gatchel RB, Weisberg JN, editors. Personality characteristics of

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- JOHN DEERE 670 770 790 870 970 1070 COMPACT UTILITY TRACTOR Service Repair ManualDocument30 pagesJOHN DEERE 670 770 790 870 970 1070 COMPACT UTILITY TRACTOR Service Repair Manualnagypipo1_06% (17)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 03 Apola Iwori de Ifarunbi-4 PDFDocument134 pages03 Apola Iwori de Ifarunbi-4 PDFWilfredo Díaz Morejón100% (2)

- Orbino, Frances Anne N. 4th Rot FdarDocument2 pagesOrbino, Frances Anne N. 4th Rot FdarFrances OrbinoNo ratings yet

- Republic Act No. 8749Document77 pagesRepublic Act No. 8749Jey RhyNo ratings yet

- Perfect Match: Application To Adopt or Foster A Cat or KittenDocument2 pagesPerfect Match: Application To Adopt or Foster A Cat or KittenChichinete MadalinaNo ratings yet

- LO1Clean The Bar AreasDocument27 pagesLO1Clean The Bar AreasEiszel CadacioNo ratings yet

- Wood Restoration Application InstructionsDocument2 pagesWood Restoration Application InstructionsJuanNo ratings yet

- Chloe Ting - 2 Weeks Shred Challenge - Free Workout Program PDFDocument1 pageChloe Ting - 2 Weeks Shred Challenge - Free Workout Program PDFvalentina9echeniqueNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ SỐ 33 - DEDocument4 pagesĐỀ SỐ 33 - DE27. Minh PhươngNo ratings yet

- E38000744 G337 - HIDD C04 IBT1 400-220kV - REV 0 - 2017-11-10Document195 pagesE38000744 G337 - HIDD C04 IBT1 400-220kV - REV 0 - 2017-11-10Sathish Chandran0% (1)

- DineshPonraj 1808165 - 05 00 - 1Document4 pagesDineshPonraj 1808165 - 05 00 - 1revanth kumarNo ratings yet

- 2022 Audit Form 2B - PCMsDocument7 pages2022 Audit Form 2B - PCMsJAMIL ASUMNo ratings yet

- Agrobiodiversity in Southeast Europe - Assessment and Policy Recommendations. Country Report SerbiaDocument92 pagesAgrobiodiversity in Southeast Europe - Assessment and Policy Recommendations. Country Report SerbiaSuzanaĐorđević-MiloševićNo ratings yet

- Covid 19 VocabularyDocument5 pagesCovid 19 VocabularyAndy08 asNo ratings yet

- Expansion ValvesDocument19 pagesExpansion ValvesMostafa ZaytounNo ratings yet

- Identify Causes and Effects of StressDocument17 pagesIdentify Causes and Effects of StressRenard JaenNo ratings yet

- USMLE WORLD QUESTIONS QuizletDocument87 pagesUSMLE WORLD QUESTIONS QuizletPatricio AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Chemistry 250 - Stereochemistry Worksheet Answers October 2, 2009Document4 pagesChemistry 250 - Stereochemistry Worksheet Answers October 2, 2009JajangNo ratings yet

- Httpswww-Clinicalkey-Es Pbidi Unam Mx2443servicecontentpdfwatermarked3-S2 0-B9780323680134000195 Pdflocale Es - ES&searcDocument18 pagesHttpswww-Clinicalkey-Es Pbidi Unam Mx2443servicecontentpdfwatermarked3-S2 0-B9780323680134000195 Pdflocale Es - ES&searcDafne TeranNo ratings yet

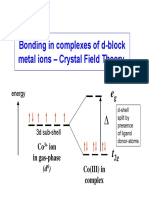

- ABC mg7 (1) - Bonding in Complexes - CrystalfieldtheoryDocument50 pagesABC mg7 (1) - Bonding in Complexes - CrystalfieldtheoryAdistaNo ratings yet

- Container Type Linear Dimensions (Base Width / Overall Width × Depth × Height) RemarksDocument2 pagesContainer Type Linear Dimensions (Base Width / Overall Width × Depth × Height) RemarksBablu JiNo ratings yet

- For Fast Vessels With Low Load Factors (1DS) : Diesel Engines10V/12V/16V 2000 M96Document2 pagesFor Fast Vessels With Low Load Factors (1DS) : Diesel Engines10V/12V/16V 2000 M96Amin ThabetNo ratings yet

- Bilal Switchgear EngineeringDocument10 pagesBilal Switchgear EngineeringAyesha awanNo ratings yet

- Public Health Aspects of Cream-Filled Pastries. A Review: Frankl. BryanDocument8 pagesPublic Health Aspects of Cream-Filled Pastries. A Review: Frankl. BryanChristine Joy PanlilioNo ratings yet

- Nervous TissueDocument32 pagesNervous TissueAnonymous GzRz4H50FNo ratings yet

- Gitman Chapter1Document11 pagesGitman Chapter1Jehad SelaweNo ratings yet

- MMF 1.0.0Document2 pagesMMF 1.0.0unconformistNo ratings yet

- Section 50 NDPS Act - Understanding The Jurisprudence of ComplianceDocument9 pagesSection 50 NDPS Act - Understanding The Jurisprudence of ComplianceMadhav BhatiaNo ratings yet

- CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist 2018 - Fillable - FormDocument5 pagesCASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist 2018 - Fillable - FormEllieNo ratings yet

- Cabison - Histopath ReviewerDocument17 pagesCabison - Histopath ReviewerPatricia CabisonNo ratings yet