Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kondo - Way of Tea

Kondo - Way of Tea

Uploaded by

Alice ComelliOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kondo - Way of Tea

Kondo - Way of Tea

Uploaded by

Alice ComelliCopyright:

Available Formats

The Way of Tea: A Symbolic Analysis Author(s): Dorinne Kondo Source: Man, New Series, Vol. 20, No.

2 (Jun., 1985), pp. 287-306 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2802386 . Accessed: 24/10/2011 09:40

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Man.

http://www.jstor.org

THE WAY OF TEA: A SYMBOLIC

DORINNE KONDO

ANALYSIS

Harvard University

The Japanese tea ceremony can be understood as a precisely structured sequence in which formal features are constitutive of meaning. Though culturally constructed meaning must inform any understanding of the rite, this alone cannot account for the tea ceremony's symbolic power. This internal reading focuses on key formal features: sequencing; the role of multiple media; and patterning or redundancy. Analysis reveals that sequencing is symbolised through: i) a constant contrast between the ritual and the mundane; 2) the use of boundaries to mark these differences; 3) the sensible qualities of objects and substances used in the ceremony, and their transposition into various sensory media; 4) the occurrence of homologous structures and sequences. The interaction of the sensory media effects a homology of code, constituting one source of redundancy. Together with the repetition of sequences, this redundancy intensifies meaning and acts as contrastive background for minute but significant changes that may occur. Through its orchestration of sequence and pattern, the tea ceremony articulates feeling and thought and creates a distilled form of experience.

The tea ceremony presents a unique challenge to the anthropologist, for the essence of tea and of Zen is said to elude logical, discursive analysis. Zen favours experience and intuition over intellection, and although the tea ceremony has given rise to a long tradition of scholarly exegesis, the Zen arts1 continue to emphasise the primacy of transcendence through a-logical, non-verbal means.2 This dialectic of experience and native exegesis is at one level unassailable and must play a key role in any attempt to understand the meaning and symbolism of the ceremony. Yet, culturally constructed mcaning cannot exhaustively account for the tea ceremony's symbolic power. While remaining mindful of the Zen masters' warnings, we will nonetheless attempt to analyse the tea ceremony as a structured sequence directed toward a 'telic or performative outcome' (Tambiah I973: I99). I assume that ritual is, among other things, a communicative and a performative act. This focus on the 'inner frame' (a) complements studies of the way of tea and of Zen aesthetics, which deal exclusively with culturally constructed meaning (e.g., Ludwig I974; Sen I979; Okakura I964) and (b) explores the application of linguistic/semiotic models to the analysis of sequence, the use of multiple media, and the role of patterning or redundancy in ritual.3 Careful attention to the formal features of the tea ceremony will enable us to delineate the movement of this complexly structured symbolic process, aimed towards a change of state in the actor's thought and feeling.

Man (N.S.) 20, 287-306

288

DORINNE KONDO

I Tea ceremonies may be held on a variety of occasions, depending on the season, the time of day, the school of tea, etc. The principal schools are Omote and Ura Senke, with Sekishuiand Enshuias major variants; the differences among them are generally minor, such as details of folding a tea napkin.4 One can participate in ceremonies in a number of ways. The first is tea as okeiko, taking lessons. So natural and effortless when performed, the rite is in fact minutely prescribed, from the smallest details of movement to the creation of larger sequences. The tea student begins with basics such as how to walk and how to wipe a tea bowl, and progresses to simple forms such as the informal bon demae(tea ceremony where a tray is used) and the various forms of usucha,the thin tea ceremony. Acquisition of skills is marked by certificates attesting to the level of expertise attained in the ceremony. The more variants one masters, the higher one's rank.5 Chakai, tea gatherings, are another context in which ceremonies are performed. A tea organisation may rent out the grounds of a temple or a restaurant and hold a day of ceremonies. A schedule is published, with several different ceremonies taking place simultaneously. Participants-usually members of the organisation-may attend the rites of their choice. The hosts are all selected in advance, sometimes performing publicly in order to demonstrate the attainment of a high rank. A recital or a concert would be a close analogue. I have also participated in tea ceremonies held as part of some festival or celebration. For example, during a 'Cultural Festival', my teacher's students were asked to prepare and serve tea for any passersby who might want to act as guests. First and foremost, however, the tea ceremony is a highly ritualised version of the host/guest interaction, and a heightened expression of the emphasis on etiquette inJapanese culture in general.6 It embodies the appreciation of formalised social interaction the importance, for example, of learning tatemae,the graces necessary to maintain harmonious social interaction.7 The theory is that mere good intentions are insufficient; one must know the proper form in order to express one's feelings of hospitality effectively. The following description is of such a host-guest interaction, focusing on a single variant of the many types of tea ceremony. The account is based primarily on written sources-manuals of tea, if you will-and to a lesser extent on informants' statements and my own experience as a student of tea. It is the full-length, formal, midday rite (shogochaji)lasting from three to five hours. Because of its length, the years of expertise required to host such a gathering, and the expense and preparation involved, it is not the most commonly practised variant-forms of the usucha,or thin tea, ceremony are-but I have selected this chajifor analysis because it is considered the 'standardchajiby which all others are created' (Palmer I976: 7I). Moreover, training in tea is designed to make the student capable of hosting such a ceremony. Focusing on a single 'ideal typical' ceremony seemed desirable for two reasons. First, since my concern is to explore the implications of an internal, semantic analysis, this 'standardchaji'as described in tea manuals and as taught to pupils, casts into relief the structure, form and sequence of the rite, providing

DORINNE KONDO

289

a text to penetrate from within. Secondly, although precise details of the ceremony may vary according to type and to context, this form constitutes a basic orchestral 'score', realised in slightly different ways in each performance. In my experience as a student of tea and according to informants' statements, both culturally constructed meaning (especially Zen aesthetics) and the symbolic orchestration of the ceremony do appear to shape the attitudes of participants in highly significant ways. Accordingly, for the purposes of this article, questions of indexical or pragmatic meaning (tea as conspicuous consumption, a domestic art, etc.) are left in abeyance. An exhaustive analysis would of course include these various levels of semantic and pragmatic meaning, both at a particularpoint in time and as they change over time (see, e.g., Tambiah I 979). The intent, then, is to focus on a single variant, as an illustrative object for the methods used to deconstruct the ritual, and as a potential point of entry into other such 'texts' (cf. e.g., Barthes I974). The particularversion described is a shogochajiin the style of the Ura Senke school, performed with the ro, or sunken hearth, used between November and April.8 II Zenrei Guests are generally invited to the ceremony a week in advance, and ideally the principal guest pays a call on the host (zenrei)to accept the invitation (Sen I979: 62). Arrival In classic tea gardens, the guests arrive at the gate, where the paving stones have been sprinkled with water, a signal for them to enter. They proceed to a room called the yoritsuki,in the outer garden, where they change clothes and put on clean split-toed socks. From there they advance to the waiting room or machiai,and await the rest of their number. Ifit has not alreadybeen determined, they select a principal guest (shokyaku)who is first in order, and a final guest (tsume)who brings up the rear. In each instance a special knowledge of the ceremony is desirable. If there is an assistant to the host, the guests may be served osayu, hot water to which a delicate flavouring may be added (Ishikawa 1976: 67). The guests view the scroll, flowers and implements displayed in the machiai, waiting area, and then proceed to the koshikakemachiai, or waiting arbour. The host returns to the tea room, leaving the gate to the inner garden slightly ajar, and the guests follow in single file, setting out on the garden path of stones. This is glossed explicitly in some works as the path into enlightenment. 9 When the last guest reaches the inner roji,s/he shuts the middle gate. In the inner to garden, the guests advance to the stone basin, or tsukubai, purify their mouths and hands with water. Seki-iri The next phase of the ceremony is called seki-iri, literally, entering into one's seat. Leaving the sandals propped against the wall of the tea room, the principal guest crawls through the nijiri-guchi(literally, the crawling-in entrance) with a crouch and slide motion. The extremely small size of the entrance is said to inculcate humility. The principal guest then proceeds to the tokonoma, alcove, kneeling before or

290

DORINNE KONDO

it to view the scroll hung there. This work of art and the tea flowers that appear there later, set the mood for the occasion. The principal guest then proceeds to his/her seat, as each guest examines the scroll. The last guest shuts the door of the nijiri-guchi with a click, a signal for the host to appear. Shozumi (Arrangingof Charcoal)"0 The host, waits in the mizuya (small preparation area adjacent to the tea room) until the guests are in place and then appears at the host entrance to exchange formal greetings with the guests. The host then returns to the mizuya and brings out charcoal, tongs, and incense burner, and begins to smooth the ashes in the brazierinto a pattern. After the fire is started, the contents of the incense burner are emptied into the brazier. The guests admire the fire, then the principal guest asks to see the incense holder, which they all examine in sequence as the host retires to the service area. S/he returns to retrieve the incense holder and to announce that 'a frugal meal' will be served. " Kaisekiis food for the tea ceremony. 12 Each guest is given a small individual tray with a bowl of rice, one of soup, and perhaps a dish of vegetables and/or fish, though other foods may be offered in addition. Sake is also served. Kaiseki should be fresh, natural, and appropriate to the season, and portions should be small. The host does not partake, but may stay to serve the guests sake. S/He retires again to the mizuya until they finish eating. The guests eat, wipe their bowls and chopsticks with small squares of paper they have brought along, and when finished, sharply click their chopsticks on the tray, a signal for the host to remove their utensils. Omogashi,moist sweets, are then carried out in lacquer boxes, one sweet per box, and after the guests partake they retire to the waiting arbour. NakadachiThe interlude here is called nakadachi-'middle standing'-a chance for the guests to stretch their legs. They may talk quietly and enjoy the beauty of the garden. A gong calls them back to the tea hut, and they enter exactly as they did before. KoichaThe next segment is the real height of the tea ceremony: the preparation and drinking of koicha,thick tea. The scroll in the alcove has now been replaced by a chabana flower) arrangement. The guests admire the arrangement, take (tea their proper places, principal guest in the seat of honour near the alcove, 13 and sit quietly as the host brings in separately: i) water jar (mizusashi);2) tea bowl, tea scoop, tea caddy; 3) receptacle for waste water (kensui),lid stand, and bamboo dipper. The host purifies the caddy and scoop by wiping them with the tea napkin, rinses and wipes the bowl, and prepares tea. These minutely prescribed acts are performed with a graceful economy of motion. The guests watch in complete silence. This is considered the climax of the ceremony. The guests then partake of the thick tea, drinking in sequence from a single bowl, the principal guest first, the tsume, or final guest, draining the bowl, wiping it, and returning it to the host. The haikenor examination follows, a question-answer session between the principal guest and the host, centring on

DORINNE KONDO

29I

the names and historical associations of the various tea implements. With the completion of the haiken and the removal of the utensils, the koichasegment concludes. Gozumi At this point there may be a rebuilding of the charcoal fire, a process called gozumi, paralleling the first lighting of the fire, shozumi. Replacing the incense is a small tray or tabako-bon, bearing a piece of charcoal in a cup, and a bamboo 'ashtray', as well as a pipe and a tiny amount of tobacco. 14 UsuchaThe usucha segment follows. The sequence of actions parallelsthat in the koichaceremony, with the following key differences: a) Usuchaitself is a less concentrated form of the same tea; it is thinner and lighter and can be whipped into a froth, while koichamust be kneaded and then stirred. b) The specific tea utensils for usuchaare defined as more informal, though not necessarily less replete with historical associations. c) Higashi-light, dry sweets eaten with the fingers-are served, and one eats them while one's tea is being made. This in contrasts with the formal presentation of omogashi lacquer boxes. Omogashi are eaten with a special pick before partaking of koicha.d) More conversation is allowed during usucha. e) Instead of sharing a single bowl of tea, each guest drains the bowl and then examines it. If desired, the guest may request additional servings of tea. In brief, usuchais more informal, lighter and freer in tone. When all guests have partaken, the principal guest asks the host to end the ceremony. At this point the guests examine the tea container and the tea scoop, as the host removes the other utensils in the reverse order from which they were initially carriedinto the room. The examination completed, the host returns to answer questions about the utensils. The ceremony closes with formal greetings (aisatsu), with both sides expressing their appreciation. The guests leave the room, principal guest last, and close the door of the niiri-guchi. They then turn to face the tea house, as the host opens the nijiri-guchiand silent bows are exchanged. This is the okurirei,or farewell. The host remains waiting until the guests are no longer in sight, and then closes the door. On the following day the chief guest should call informally upon the host to express the group's appreciation (Palmer I976: 77).

III The aesthetic sensibility informing the way of tea traces its roots through Zen Buddhism, to Chinese Ch'an Buddhism and Taoism. Tea ceremony, like other Zen arts, is a religious/aesthetic/philosophical 'way' (injapanese, michior do;in Chinese, tao). This di, an elusive concept to define, could be glossed as 'the inner essence of reality' (Bellah I957: 6i). Accordingly, the 'way' of tea, like the other Zen master arts, is more than mere artistic or technical proficiency: it is a path to Enlightenment. According to Zen doctrine, Enlightenment is mu-emptiness or nothingness. Zen ideals include qualities such as mushin, selflessness or detachment, and

292

DORINNE KONDO

munen,muso,freedom from all ideas and thoughts. Efforts to master the intricate discipline of tea or another Zen art constitute a process of self-realisation, whereby one so thoroughly incorporates the form that it-or other worldly concerns, such as the desire to perform well-no longer requires one's conscious attention. This is the state of 'emptiness'. Through tea or another Zen art, a person may be said to attain the states of y-gen or kotan(yuigen kyochi,kotanno no kyjchi o tassuru).Yugenis a term associated closely with No drama. It bespeaks the evanescence and pathos of life, hinting at the eternal and infinite. It is subtle elegance and profundity. Kotan is defined as seasoned simplicity, when everything unnecessary (e.g., worldly thoughts and cares) has fallen away, leaving only the essential core. The pathway to this state lies in action and intuition; logic and elaborateverbal exegesis are correspondingly downplayed. For example, in tea, as in all the master arts, instruction has little in common with Western didactic methods; instead, one learns through observation, imitation, illustration, and performance-that is, through non-verbal means.15 This form of learning is thought to be exceedingly difficult, a hardship, for unless one undergoes hardship (kuro) one cannot become a mature practitioner of the art. Hardship polishes the soul as well as one's technique. To attain the state of kotantherefore requires years of practice, discipline, even mental and physical suffering. 16 Mastery may take an entire lifetime but consciousness of technique and painstaking years of practice dissolve in the pure action of creation.17 But perhaps the Zen doctrine bearing most directly on the tea aesthetic is the emphasis on the mundaneas a sphere of action and a source of beauty. The Buddha nature, hence the path to Enlightenment, is to be found in every sentient being and in the most everyday activities.18 Extending this exaltation of the mundane to the aesthetic realm, Zen describes a fusion of opposites in which the beautiful and the ordinary are no longer distinct. This leads to the aesthetic appreciation of imperfection and poverty, of sabi and wabi. Inasmuch as the qualities can be defined, sabi is the beauty of the imperfect, the old, the lonely, while wabi is the beauty of simplicity and poverty (Hasumi I964: Si; Ludwig I974: 47). So closely are these qualities associated with the tea ceremony that the ceremony of the great master Sen no Rikyu was called wabi cha, or wabitea. 19 Typically, bothJapanese and Western scholars analyze the tea ceremony as a method of self-realisation (e.g., Suzuki I970; Herrigel I953) and/or in terms of the Zen aesthetic (e.g., Suzuki I970; Okakura I964). These explanations are compelling-even unassailable. Zen philosophy and aesthetics form the consciously held attitudes of the tea adept, and enactment of the ceremony gives life to these beliefs. Yet, there are key questions traditional philosophical and aesthetic approaches do not explore. Are there 'rules' that would enable us to account for the sequencing of the ceremony? Why is there a seemingly inordinate amount of repetition? How do the various media-auditory, visual, gestural, olfactory, gustatory-interact, and do they do so in some intelligible way? What dictates the pre-eminence of koichaas the most formal segment of the ceremony? A formal semantic analysis that addresses such questions must be based on a thorough grounding in ethnographic detail, while going beyond native exegesis to illuminate more precisely the structure and sequence of the

DORINNE KONDO

293

ritual and how these in turn act persuasively to generate a feeling of exceptional experience. IV Like narrative, ritual is an unfolding, a sequence of movement with tensions, climaxes and directionality. The ritual process must create a ritual domain, '. . . by seducing participantsinto involvement with its form and . . . [by] propelling the now-transformed participants out into life' (Peacock I969: I72). I will argue that in the tea ceremony, the principal symbolic devices accounting for the movements of the rite are: i) a constant contrast between the ritual and the mundane and degrees thereof; 2) the use of boundaries to maintain these differences; 3) the sensible qualities of objects and substances used in the ceremony and the transposition of these qualities into various sensory media; 4) perhaps most important, the repetition of sequences and the occurrence of homologous structures, objects, actions, as the principalmeans of signifying the progression of the ritual. A logical point of departurefor analysis is the physical, spatial arrangement of the tea garden and hut. The garden is an especially salient feature, for it is the first apprehensible signal that one is entering the ritual world. Consequently, it must prepare the participant, beginning to restructurehis/her attitude appropriately. A diagram of the garden follows. It should be noted that, like the many variants of the tea ceremony itself, tea gardens also differ from one another. The choice of a particular arrangement ultimately lies with the host.20 However, though certain details may vary, the basic structure of the inner and outer roji does not change; moreover, the impression imparted by each section of the garden must differ, with the outer garden more normal and ordinary, the inner more set apart from the everyday world. First, the garden itself is demarcated from the outside world by the gate. Upon entering, guests find the garden in turn is divided into the inner and outer roji, or dewy path. The outer rojicomprises two principal structures, the machiai or waiting room, and the koshikakemachiai, the waiting bench or waiting arbour. The former is enclosed and floored with tatami mats, the latter is roofed but open. Near the koshikakemachiaiis the privy or setchin,used primarily for display; it may be inspected if the guests so desire, as it, too, has been purified and preparedfor the guests' aesthetic enjoyment. The path in the outer garden is direct, generally a paved stone walkway, and is thus primarily functional or utilitarian. The only real criterion for the outer roji is that it be scrupulously clean. The garden is pleasant, with a free, light atmosphere, and flowering trees may be allowed there (Allan Palmer, personal communication). The outer rojiis a preliminary step into ritual time. As one moves into the inner garden, the atmosphere shifts to one of serene tranquillity and harmony with nature. Everything in the inner garden reflects an induction into the ritual domain. Guests may no longer speak loudly, nor may they touch upon frivolous topics of conversation, for presumably they have left their earthly concerns behind. The path is irregular and divided, to provoke aesthetic interest and leisurely contemplation. Ferns, small plants and trees, and,

294

DORINNE KONDO

K INNER ROJI

c~>c~c2

c?c-,

co

n <:~PZ HD63 tc

<:Dc7c)

OUTER

ROJI

0S~~

A B C D E F G H I

Gate Entry Yoritsuki Machial (waiting room) Setchin (privy) Koshikake machial (waiting arbour) Middle gate Stone lantern Crouching basin Chiriana (dust hole) Nijlrl-guchl (crawling-in entrance) A B D

J

K

The spatialarrangement a typicalteagarden. of especially, moss, are in evidence; no flowering plants are allowed. Everything must be simple and artless, 'things such as grow wild in the hills' (Kuck I940: I98-9). The feeling of the inner garden is one of wabi and sabi. The principal feature of the inner garden is the water basin, or tsukubai. Water is the purificatory agent par excellence inJapanese culture, and it is represented in the inner garden by the water in the basin which the guests use to purify themselves.21 Thus the presence of water, and the wetness of the garden and its structures, is a metaphor for freshness, naturalnessand purity. Just before entering the tea room, the guests pass a hole in the earth, called chirianaor 'dust hole'. This is filled with clippings of trees and plants, and symbolises the 'receptacle for the dust of the world' (Ishikawa I976: 6i). Clearly, the passage from the outer to the inner garden is ajourney through physical and symbolic space, advancing from the mundane to the ritual.22

DORINNE KONDO

295

Boundaries and mediating structures contribute to the evocation of a 'world apart'. Before the participants set foot on the roji, they must enter through the gate and advance to the yoritsuki. Unlike everyday life, where one would announce one's entrance into the foyer with an 'excuse me', during the tea ceremony the gate is left open and water sprinkled on the paving stones signals that the guests may enter. (Ishikawa I976: 56; Sen I979: io). This is recapitulated at the middle gate and at the entrance to the tea room; in each case the door or gate is left slightly open, again a signal to the guests that they may proceed into the next part of the tea gardens. The middle gate is a boundary marker directly mediating between outer and inner gardens. At the outset it is left half-closed, to maintain a relation of contiguity between the outer and the inner gardens, to symbolise that they share the same qualities. Yet, the gate cannot be flung wide open, lest this leave the inner garden too vulnerable to the relative worldliness of the outer. When the final guest passes through the gate, s/he shuts it firmly. This symbolically closes off ritual space from the mundane.23 Again, once the final guest enters the tea room, the door is firmly shut with a click, to seal off all reminders of the outside. Mediation also takes place on the level of the buildings of the garden. The machiaiand the tea room itself form a homologous pair; each is small, enclosed, tatami-lined,and a scroll hangs in each. Again, meaning arises through contrast. The machiaiis informal, lighter and airier than the tea room. A smoking tray, a sign of informality, is displayed there, whereas no smoking is allowed in the tea room. In the tea hut, the symbolic connotations of tea served there contrast with the purificatory but still comparatively mundane osayu, or hot water. Near the gate, however, deep in the outer garden and almost in the inner one, is the koshikake machiai(waiting arbour), another mediating structure. Physically, it is placed almost between gardens, though it is considered part of the outer roji. And unlike the machiaiitself, it has no precise analogue in the ceremony. It is open and thus differs from either the tea hut or the machiai,to allow the guests to enjoy the beauties of nature. In the space between the machiaiand the tea room, the beauties of the garden must prepare the participant for entry into the ritual world proper. The koshikake machiai is thus a midpoint in the symbolic continuum from the mundane to the ritual: not quite a building, not quite the garden, but something of both. The following table summarises the differences between the various parts of the garden:

Outside World Mediator Gate Yoritsuki Outergarden Waiting room Hot water Flowers Trees Direct path Fire Utilitarian Physical Mundane Ritual Mediator Waiting arbor Gate Inner Tea room Tea Moss Ferns Indirect Water Aesthetic Spiritual Ritual

Mundane

296

DORINNE KONDO

Thus, movement from the outside world into the tea garden is a step into the ritual world; movement from one part of the garden to the other is a further progression into the domain of ritual time and space. This both strips the guests of their worldliness and envelops them in a ritual atmosphere of sabi/wabi. The meaning of any single element is opaque when viewed in isolation, but acquires significance when contrasted to its analogues in other parts of the ceremony and to the mundane world outside. Relative formality/informality is symbolised through the exploitation of differences and similarities among features. The tea garden stands in contrast to the world outside; in the garden itself, the outer garden was this-worldy and informal, the inner formal. The same principles apply not only to the induction of the participantinto ritual time but in the easing of symbolic intensity and the return into the mundane world. One example would be the building of the first fire (shozumi)and the building of the second fire (gozumi). Shozumi is a prelude to the koichasegment, the formal climax of the ceremony; thus there is a logical imperative to render this part of the ceremony relatively formal. The mood is set with the slow patterning of the ashes in the brazier and the burning of incense to fill the air with the fragranceof spirituality. During the second building of the fire, no such careful patterning is necessary; indeed the segment can be omitted altogether. The host may bring out cushions to make the guests more comfortable and carries out the smoking tray. One recalls that this was last seen in the machiai.Thus, though the guests are forbidden to smoke in the tea room, the smoking tray signifies informality; it represents the act of smoking, an informal activity, and it is metonymically associated with the structures of the outer garden and the outer world. This recapitulation of elements creates formality and a spiritual, contemplative mood in shozumi, and an informal atmosphere in the gozumi, a quick descent from the intensely formal symbolism of koicha. Accordingly, in juxtaposing the two separated sequences of shozumi and gozumi, the significance of each, their relative formality or informality, is clarified. Moreover, examining the relationship of segments occurring in sequencealso enables us to illuminate their respective meanings. The positioning ofgozumi after the solemn koichasegment highlights the worldliness of the former and the formal mood of the latter. In short, the entire ritual moves along the axis of relative this-worldliness or other-worldliness, and systematically uses the devices of metaphor, metonym and contrast to communicate those differences.

V Now that certain basic symbolic mechanisms informing the tea ceremony have been identified, what of the movement of the sequence as a whole? The progression is encoded in a seemingly chaotic concatenation of modes. Rather than focusing on all of them simultaneously, we will trace one thread throughout the entire sequence: the auditory channel and the role of silence, signals, and verbal v. non-verbal symbolism in conveying an impression of increasing and then decreasing symbolic intensity. The auditory mode is one that immediately presents itself for analysis, for two reasons. First, the pre-eminence of non-

DORINNE KONDO

297

verbal over verbal expression is a general theme injapanese culture.24 Secondly, this general emphasis is carried over into the realm of Zen doctrine and aesthetics.25 In this cultural context, it is not surprising that in the tea ceremony the progressive induction into ritual time is reflected in an increasing emphasis on non-verbal modes of communication. The climax of each segment-the patterning of the ashes, the preparation of both koicha and usucha-is always performed in utter silence. And the koichasegment, in its entirety the symbolic apex of the ceremony, is the most silent and solemn of all the major sequences. But the situation is more complex than a simple equation between silence and the ritual world, noise and the mundane, might indicate. Beginning from a sharp demarcation from the mundane (a non-verbal signal-the open door-at the entrance to the house) which signifies entry into an 'exceptional' domain, emphasis shifts from verbal channels to increasingly non-verbal modes. The initial emphasis is on human interaction; e.g., conversation is permitted, and bows (albeit silent ones) are exchanged at the middle gate. This is reversed when the guests actually enter the tea room. They first bow, not to the person of the host, but to objects: the scroll, the brazier and so on. In Japan, objects in general are not considered atomistic entities, but extensions of people (cf. Bachnik I978; Kondo I982). These objects are symbolic extensions of the host, but that acknowledgement is first transmitted indirectly, heightening this connexion between person and object. This reversal is perpetuated, moreover, in other specific contexts throughout the ceremony. The host is always signalled through 'percussion' as opposed to speech. 26 The noise of the tea room door as it shuts tells him/her that the guests have completed their entry. The click of the chopsticks on the tray indicates that the guests have finished their meal. After the interval the guests are summoned back to the tea room by a gong, and not by a personal greeting from the host.27 Here, an initially social, and hence more informal interaction between persons contrasts with the entry into the ritual domain of non-verbal sounds, and especially, silence. It is interesting to note that ritualised verbalisations-primarily questions and polite formulae-are uttered at certain junctures, generally to admire and comment upon the art objects used during the ceremony. This creates within each major segment (shozumi,koicha,usucha,etc.) small increments in symbolic tension, climaxes and denouements. The first involves a combination of verbal exchanges and non-verbal acts; the climax occurs entirely in silence, with the sequence eventually shifting back to the verbal, and thus more informal, mode in the denouement. For example, after the intensely solemn preparation and drinking of koicha,the verbalisations involving the presentation of the tea bowl, the questions surrounding the tea utensils, in fact symbolically mark a windingdown of the ritual. From the climax of koichapreparationto a less formal, more social question-and-answer session that is less bound and fixed, one moves to the even more informal usucha preparationand the still more informal questions and answers following that. Accordingly, the progression of the ceremony forms a steady decompression from the periods of heightened symbolic intensity. At this point, then, we can summarise the functions of auditory signs in

298

DORINNE KONDO

the tea ceremony:percussive-signalling; verbal-social, relatively informal; silence-symbolic intensity, the height of ritual time. The contrast between verbal and non-verbal modes as one pivot of the syntactic structure of the ritual begins to articulatethe process of movement, but in order to understand more precisely the sequencing of the ceremony, one must focus upon the central opposition of ritual v. mundane, and its metaphorical representation in the sensible qualities of the substances and the objects used in the tea ceremony. VI In examining the role of substances in the ceremony, three features are highlighted: i) setting apart the ritual from the mundane; 2) the similarities and differences in consecutively occurring sequences; 3) creating significant contrasts between similar but discontinuous parts of the ritual (first and second fires, This is a movement from the metaphorically osayu-kaiseki-koicha-usucha). mundane to the metaphorically ritual and back again. First, many of the substances used are particularto the ceremony itself and are only infrequently found in other contexts. For example, among the foods, kaisekiis by definition a tea ceremony meal. This type of refined cuisine can also be found in restaurantsthat specialise in such elegant delicacies, but its primary association is with the way of tea. Ceremonial sweets form another specialised category. Both omogashiand higashi are ritual terms, and both are beautiful aesthetic creations, smaller and more elegant than the usual everyday confections. One could conceivably use regular sweets in the place of proper omogashi or higashi(when I was a student of tea, we did this to economise, as tea ceremony sweets, being specialities, are expensive); equally, one could buy tea ceremony sweets to eat at home. Yet the chief function of omogashi and higashi is ceremonial. Similar arguments could be advanced for the non-food substances. The tea itself is associated chiefly with the ceremony, symbolised in the special ritual terms koichaand usucha.Both are forms of matcha,powdered green tea. Usucha, thin tea, might be served to guests informally, but to my knowledge, koicha-a thick, concentrated form of matcha-is rarely, perhaps never, encountered outside the context of the ceremony. Of the other non-food substances, both are in some way special. Osayu, hot water, is not commonly consumed in everyday life. Sake is one of the typical Shinto offerings to the gods and is found in many Shinto rituals; thus it has sacral connotations. Accordingly, both food and non-food substances create a symbolic cleavage between the ritual and the mundane. Substances also symbolise the movement of the ceremony. On entering the tea room, for example, the sequence begins with fire, air and incense (rendered special by the connotations of incense as a substance) and moves toward increasing intensity with the eating of the fresh foods, drinking of the strong, alcoholic sake, eating the moist sweets, and performing another ablution with cool, fresh water. 28 The entire first half of the rite is a slow, elaboratepreparation for the climax of koicha;it is thought that to drink this thick tea without proper

DORINNE KONDO

299

fortification might be dangerous. After the climax, the ceremony moves again to the element of fire and of tobacco smoke, not incense, signalling a much more informal mood, and then to the eating of dry sweets (informal because they can be picked up and eaten with the hands) and the drinking of weak or thin tea. Several points are important to note: i) Purification with cold water always precedes entry into the tea room, and in each case presages a significant heightening of the ritual atmosphere. 2) The core of the ceremony could be said to correspond to metaphorical spirituality, and the cultural significance of the substances used: sake, moist sweets made especially for the tea ceremony, the purificatory cold water ablution, and then the thick tea. All these occur in sequence, together, and thus form a 'bundle of relations' with considerable symbolic impact. 3) The pre-eminence of koichacan be explained in terms of the metaphorical qualities of the substance itself. 29 Tea symbolises the introspective qualities associated with Zen: an awakening of the senses and a contemplative atmosphere (Watts I957: I90; Suzuki I970: 298). Though not perfectly symmetrical, it is as though the ritual begins from the core and works outward, so that the sequences on either side of the climactic episodes recapitulate one another. There is a reversal from one half to the other, as the sequence itself builds to a high point, bringing together elements in a certain order. In the process of re-entry into the mundane, the opposite sequence is followed. Not only is this demonstrated at the general level of major sequences, it occurs within each segment; e. g., when the host takes utensils out of the room in the reverse order from which they were first brought in. The ritual also makes full use of similar segments occurring in discontinuous parts of the sequence. Take, for example, the partaking of food and drink during the ceremony. Here, the similarities provide a contrastive ground for the salient among these segments. The relative formality of these sequences differences and koicha,higashiand usucha) highlighted in is (osayu, kaisekiand sake, omogashi juxtaposition, symbolising the progressive induction and release of the participant. In osayu, no foods are served, and the drink itself is nothing but hot water, though some delicate flavouring agent can be added. This, then, is a 'weak'30 drink-different from everyday Japanese beverages and hence signalling an entry into ritual time, but not concentrated, hence not symbolically powerful. Sake, which follows, is powerful and strong, and thus symbolically more intense than osayu. It holds dual associations, with social, hence more mundane, activity on the one hand, and as a common feature in the Shinto (not Zen) religion.31 Koicha singifies its strength even in its heavy texture. It is a thick distillate of a natural product, powdered tea leaves, and thus is imbued with these qualities in highly concentrated form. It is a substance peculiar to the ceremony itself. Usucha partakes of these same qualities, but in less intense fashion. It is slightly less special, as it is a less concentrated form of the same tea. And, though it is not the most common beverage served to guests, one could do so-or prepare a bowl for one's own consumption; thus, it is less purely ceremonial in its connotations. Again, the basic movements of the rite, from the more ordinary to the more extraordinary and back again, are encoded even in the sensible properties of the substances used in the various segments of the ritual. Schematically represented, the ritual is divisible as follows:

300

DORINNE KONDO

Informal Osayu weak no food

Formal Sake strong kaiseki

Formal Koicha thick (strong) omogashi

Informal Usucha thin (weak) higashi

Thus the repetition, with variation, of similar sequences is a major mode of symbolising the progression of the ritual. The similarities act as background for the differences in meaning among these segments. In sum, in the tea ceremony one finds many symbolic devices: i) metaphor (wetness as a metaphor for freshness and purity, tea as a metaphor for the ceremony itself); 2) metonym, part standing for whole, or relations of contiguity and proximity to (outer garden and outer world); 3) repetition of sequences in different parts of the ceremony, compelling the mind to explore the similarities and differences between these sequences; 4) position of elements in the segment takes on heightsequence, e.g., when the kaiseki-sake-omogashi-koicha ened symbolic intensity because these elements occur in combination. Any taken alone would not have the same meaning; 5) an element of reversal, in which the return to the mundane is symbolised by reversing the original sequence; 6) contrast among segments and between ritual and non-ritual food and drink, serving as markers of entry into the ritual domain.32 An internal analysis of ritual should not rest at a simple tripartite structuring of a sequence or constructing a matrix of binary oppositions. Rather, one can attempt to recapture with some precision the movements of the rite. Yet even this is far from complete. In what other ways might the participants be compelled to feel serenely at peace?

VII Redundancy of message among the sensory modes and the repetition of sequences is a key rhetorical/symbolic device in the ceremony. Let us begin with the interaction of the graphic, gestural, gustatory, tactile and verbal sensory channels and the process of objectification, or the transposition of intangible qualities into various sensory modes. The performative creation of the ritual domain begins in the yoritsukiwhere the guests put on fresh tabi, brush the dust off their clothes and change their attire. Here, in leaving behind their everyday clothing, they physically divest themselves of reminders of the everyday world. This progressive shedding of worldly concerns continues during their procession in the garden and is powerfully symbolised in the passing of the chiriana(dust hole) near the tea room. Here is one's final opportunity to brush away the pollutions and contingencies of everyday life before entering the tea room. One last reminder of this entry into a ritual domain is the act of removing one's sandals and standing them up outside the hut.33 This transmutation of qualities-in this case, pollution or this-worldliness-into physical objects and tangible properties, is one of the most compelling of performative acts. It gives ritual a literalness that verbal communication rarely achieves. After ridding themselves

DORINNE KONDO

30I

of mundane objects and hence 'mundaneness' in general, the participants are ready to absorb 'ritualness' in its many forms. Beginning with the purity, freshness and naturalness of the garden, the transfer of symbolic qualities intensifies. For example, the ritual ablution with water not only washes away the 'dust of the world', it also metonymically transfers the qualities of water-freshness and purity-to the persons of the guests themselves. The crouching actions at the basin and at the entrance to the tea room signify humility. Once again it is important to note the representation of a mental state by an action, and the performative aspect involved: performing these actions is as good as having the right attitude, for it should induce the right attitude. In the tea room the ritual atmosphere heightens. For example, incense is burned in the tea room, an act with religious connotations inJapanese culture.34 The tone it sets is immediately sacral and contemplative. The scrolls and the flower arrangement set the mood and the theme for the particular ceremony, and by viewing these art objects, the sentiments expressed through the visual and graphic media are, ideally at least, transferred to the viewer in order to structure his/her mental attitude. Just as a Zen painting may leave an empty expanse of white, so the mind of the participant should achieve the same emptiness, mushin. The drinking of tea itself is preceded by the climactic moments of its preparation, where the bounded movements, the graceful yet logical progression of actions, express the essence of peace and calm. In drinking the aesthetic infusion, one partakes not only of the tea and of the qualities it embodies, but of the care, the grace and the selflessness that went into its preparation. The viewing of the tea bowl, its asymmetry and coarseness to the touch, its imperfections, the tea implements and their associations, all contribute further to the symbolic intensity of the ceremony. Like the notes of a baroque score, different symbols in different modes occur in profusion, yet move smoothly forward in an intelligible sequence. The interaction of various sensory media creates a multiple layering of meanings that 'all add up to one message' (Leach I976: 41). Though there may be qualitative and significant differences among the various sensory modes -and I believe there are, as Jakobson (I960), Langer (I942) and Levi-Strauss (I969) have pointed out-the gathering of these elements into a single ceremony tends to highlight the similarities among them. Moreover, though the referents of a single symbol may be myriad, the location of the symbol in the nexus of the tea ceremony narrows its meaning or accents a certain meaning to the partial exclusion of others. This homology of code among the sensory modes is one of the major sources of the tea ceremony's symbolic efficacy and power. What, then, of the constant repetition of actions and sequences? I would argue that it provides a contrastive background for the subtle changes that take place from one segment of the ritual to another. The basic similarity in the sequence renders any changes all the more striking. In this case, redundancy is not 'superfluity'.35Rather, through the subtle variations in the message and in the media into which it is transposed, persuasive symbolic power is inevitably intensified. 36In short, in the tea ceremony, redundancy createsan intensification

302

DORINNE KONDO

of meaning in and of itself, and it is a vehicle of meaning for the minute but significant changes that may occur in the repetition of a sequence.

VIII Finally, this allows something more general to be said about the nature of ritual itself. Should ritual be a mere communicative device designed to impart a simple, discursive message, there would be little apparent rationale for the existence of the ritual form. Ritual 'messages' can be repetitive, prodigally so, freely drawing upon all the sensory modes and all manner of symbolic devices. Folk belief may also encourage a view of ritual as rigid, convention-bound and inimical to real, spontaneous feeling. Why, say these pragmatists, make such a fuss over drinking a cup of tea? Perhaps the answer to these riddles lies with the Zen masters. For at least in the tea ceremony, and perhaps in other ritualsas well, it is by becoming one with the rules that the possibility of transcendence lies.37 The formality of ritual also enables the participant to forget the contingencies of everyday life and frees the mind for 'greater' thoughts.38 Ritual, then, need not be an ossified form interfering with 'true' feeling and spontaneity. In fact, form separates the ritual from the everyday and distinguishes the casual partaking of a cup of tea from chanoyu, the way of tea. By its precise orchestration of sequence and the interrelations among symbols in different sensory modes, the tea ceremony articulates feeling and thought, creating a distilled form of experience set apart from the mundane world.

NOTES

Several people have read this manuscript in draft form. I should particularly like to thank S. J. Tambiah, John C. Pelzel, Matthews Hamabata and Vincent Crapanzano for their perceptive comments. Of course, final responsibility lies solely with the author. 1 Among themgado (the way of poetry), kyuido way of archery), kendo(the way of the sword) (the and Bushido(the way of the warrior). 2 Scholars have long been sensitive to the differences and similarities among various sensory modes (e.g., Jakobson's visual and auditory signs, Langer's discursive and presentationalsymbols). As a method of representation and symbolisation, discursive language, like any mode of communication-the plastic arts, music, gesture and so on-excels at certain tasks and is less suited for others. Roland Barthes, the structuralist literary critic, dares to imply that an art closely related to tea-haiku-is refractory to Western schemes of analysis:'il nous resiste, perd finalement les adjectifs qu'un moment plus t6t on lui decernait et entre dans cette suspension du sens, qui nous est la chose la plus etrange puisqu'elle rend impossible l'exercice le plus courant de notre parole, qui est le . commentaire . .' (Barthes I970: IIO). ' See Tambiah (I979) for a comprehensive review ofthe treatment ofthese issues in the literature. 4 While in Japan, I studied with a teacher of the Ura Senke school for two years, and after returning to the United States continued lessons with another Ura Senke teacher for about six months. 5 This is a practice common in forms of the traditional arts;inju-do, for instance, one rises through the different kyu, or grades, and receives certificates and other external symbols of rank, such as the colour of the belt. Like all the arts, however, true mastery is an unattainablegoal; merely to approach it takes a lifetime.

DORINNE KONDO

303

6 As such, tea tends to be studied and practised by those who value such qualities and who possess sufficient leisure and economic means to enjoy it; i.e., those of at least middle-class status. Regional variations also exist, at least in folk ideology. Residents of certain areas, known for their appreciation of high culture (e.g., Kanazawa) are said to be more familiar with the ceremony than the average Japanese citizen and to frequently serve matcha,the powdered tea used during the ceremony, to their guests, instead of the usual fare of brewed tea. 7 Another highly ritualised expression of this emphasis on formality is the schools of etiquette, such as the Ogasawara-ryu. This is most likely an upper/upper-middle class phenomenon. 8 During my years as a pupil of tea, I attended such a ceremony once, at my teacher's home. The actual experience did confirm the formal rules learned through lessons and books on tea. 9 When the guests enter the tea garden, they wear their host's footgear, not their own. The roji (tea garden), it is said, is not to be trodden by shoes 'defiled by the soil of the outside world' (Okakura I964: 34). 10 During thefuro demae(the tea ceremony performed between May and October with a portable brazier rather than the sunken hearth, or ro) this segment follows the kaisekimeal. 11 The practice of ritual modesty is a common part ofJapanese etiquette. Here, unlike the polite understatement of everyday life, kaisekiis in fact a frugal meal, at least in terms of the amount of food served-though often the dishes are expensive seasonal delicacies. 12 Its initial meaning was 'warming stone', for Zen monks would place a warm stone near their stomachs during long hours of meditation in order to ward off hunger (Palmer I976C: 32). 13 Seating arrangements, both during the ceremony and in the wider society, are indices of status. The seat for the person of highest status is called the kamiza, high or upper seat, and it is usually in front of the alcove and away from the door. 14 'Regardless of the fact that the tabako-bon not actually used for smoking, it is the sign of a is relaxed atmosphere' (Palmer I976: 65). 15 For example, those who enter the Ura Senke school as disciples and students of tea undergo a long apprenticeship, where their only instruction is to watch the teacher teaching other students. They themselves are not allowed even to touch a tea implement until the day when they are suddenly, without warning, told to perform the ceremony in front of the teacher. 16 See Kondo (I982) for a lengthier exposition of the concept of kuri. 17 Suzuki (I970: 3 i) relates a classic admonition about Zen ink painting, but the principle applies to all the Zen arts: 'Draw bamboos for ten years, become a bamboo, then forget all about bamboos when you are drawing'. 18 Ludwig cites a famous Taoist aphorism to that effect: 'In bearing water and chopping wood, there lies the wonderful Tao' (Ludwig I974: 39). In the tea ceremony, then, Enlightenment lies in the preparing and drinking of a cup of tea. 19 The tea room itself, for example, embodies pure sabi-wabi:'The tea hut is extremely bare and almost devoid of colour. If a flower is arrangedin a vase, it is usually a single, small blossom of some quiet hue or white. The tea utensils are not of exquisite porcelain but of coarse pottery, often a dull brown or black and imperfectly formed. The kettle may be a little rusty. Yet from these objects we receive an impression not of gloominess or shabbiness but one of quiet harmony and peace . (Tsunoda et al. i958: 28I). The aesthetic of sabiand wabiis central to an understanding of the ceremony, not only for the sense of what constitutes 'tea style' in the performance of the ceremony (grace, calm, silence, economy of movement), but in its related arts; flower arranging, pottery, scrolls, cooking, gardens and so on. Briefly, the same values of simplicity, asymmetry, age, roughness, austerity and monochrome colour are observed in the ancillary arts. The tea garden is, like allJapanesegardens, simple, peaceful and tranquil, but it should have these qualities to a heightened degree, imparting an impression of being shut away from the outside world. Tea gardens are usually bare of flowers, using instead less showy plants to create a harmonious aesthetic quality. The tea room is small, bare and dimly lit. Tea style in flowers is known for its simplicity and naturalness. Usually a chabana arrangement consists of a single flower and a few leaves. Its distinctiveness is reflected in the verb used to describe the process of arranging:whereas for most other styles of flower arrangingone applies the term ikeru(to arrange), with chabanaone must ireru-put or place into. 'Chabanais a delightful anomaly in the sphere of ikebana.It has no rules; its charm lies in its exquisite simplicity. It cannot be taught, it can only be felt' (Davidson I970: I0-I ).

304

DORINNE KONDO

The tea bowls are of rough pottery, often uneven and lopsided; the most famous types of tea ware (e.g., Raku, Oribe) tend to be black, dullish red, dull brown, or a combination of black and dark green. These are purest sabi-wabi. The scrolls or paintings hung in the alcove are usually of Zen origin; a scroll might be a laconic Zen epigram, or an ink painting. In either case, it is generally simple black on white. 20 The wealthy might be able to afford a tea room or tea garden in their residences; otherwise, one would use the grounds of, for example, a temple, or an elegantJapanese restaurant. 21 It is also represented indexically through the presence of moss, which requires a moist environment in order to survive. Moreover, one recalls that the name of the garden itself, the Dewy Path, restates this association with wetness, purity, and freshness, and that the path itself is in fact sprinkled with waterjust prior to the arrivalof the guests. 22 Architect Fumihiko Maki argues that the concept of oku, the depths, characterisesJapanese architecture(e. g., shrines, streets, arrangementof rooms in a house). The division of the garden into inner and outer roji, for instance, is also characteristic of shrine precincts where the outer path is relatively straight, while the inner path indirect and winding. This 'create(s) a sense of drama and ritual in the process of approaching' the oku (Maki I979: 59). Here the dimensions of space and time are both implied. 23 The same is true, but on a heightened level of purity and symbolic intensity, at the nijiri-guchi. 24 There are countless examples, but I shall cite only a few. Perhaps the ideal form of communication in Japan is ishin denshin,a highly developed empathy in which mutual sensitivity obviates the need for words. Lebra (I976: I i 5) describes this as follows: 'Words arepaltry against the significance of reading subtle signs and signals and the intuitive grasp of each other's feelings'. Studies of childhood socialisation practices inJapan and the United States consistently point to the greater emphasis inJapan on non-verbal interaction between mother and infant. (See, for example, Caudill & Weinstein I969.) An ideal for masculine behaviour (indeed, for anyone) isfugenjikko, silent action. That is, one should prove one's worth through action, not through empty words. 25 The term ma-interval, pause, space, room-is crucial here, for it is used both in everyday social interaction and as an aesthetic concept. Ma exists in Zen paintings and in flower arrangements, where the brush strokes or lines of the flowers and branches describe a space. It corresponds, in this context, to the emptiness of mu in Zen doctrine. But ma is not simply spatial; it can also signify a pause, a silence. A conversation should have ma, appropriatespacing or intervals, to punctuate the rhythms of speech. One is not obligated to fill the silence with words. The spacing in this case contributes to a sense of repose. Ku, emptiness-as in the empty space of air-is an important related concept. 26 Cf. Rodney Needham (I967). 27 Cf. Evon Vogt I977, on the role of percussion in Zinacanteco ritual. 28 The five elements (wood, water, fire, earth, metal) from Chineses cosmology, undoubtedly play a part here, and to some extent feature in exegeses of the symbolism of tea. Indeed, one could say that preparing and drinking tea unites the five elements: wood (charcoal); water (for tea); fire; earth (tea bowl); metal (brazier). 29 Tea embodies the naturalness of sabi and wabi:a powder made of ground-up leaves, it unites these naturalelements with the naturalelement of water, to create a representation, in palpable form, of the Japanese aesthetic. And finally, its thick texture and concentrated state are metaphorical expressions of the intensity of the ritual experience, here distilled into its very essence, a single bowl of tea. The tea is, in a sense, the ritual experience itself. In Fernandez's (I977) terms, the tea is a metaphor that is particularly 'apt'; it embodies the ideas informing the ceremony, as well as making logical sense in terms of the progression of the sequence. 30 'Weak' and 'strong', or rather, 'thick', and 'thin', are salient cultural categories. In fact, 'koi' and 'usui' ('thick' and 'thin') are used in the words koichaand usucha. 31 On first glance, sake might logically be considered the climax of the ceremony; it, too, is a strong, powerful liquid with religious connotations, and it is undoubtedly no coincidence that these occur in close proximity to one another as part of the height of the ceremony. However, when one recalls the connotations of each, based on ethnographic evidence and native exegesis, it is clear that sake on the one hand is more social and informal, and on the other is associated with religion-but with Shinto, not with Zen. In this form, it is known as Omiki, the gods' sake. It is used in the Shinto wedding ceremony and a

DORINNE KONDO

305

special variety of sakeis drunk during the New Year holidays. In this sense, it could be said to be part of the long, purificatory process which takes place before the partaking of the tea itself. Thus, sakeis both social and 'sacred' or special. The manuals on tea emphasise the social connotations of sake, saying that it is offered in order to foster a friendly spirit among the participants. Indeed, Edwards argues for a strong relationship between 'sakeand solidarity', which appearsin ritual contexts as part of a symbolic means of creating 'bonds between men [sic.], or between men and gods. (Edwards I982: 703). 32 Another way of analysing the tea ceremony would be to compare it to other rituals involving the use of stimulants, from other areas of the world. Though this exceeds the bounds of this particulararticle, such a comparison might prove highly illuminating. The opposition between inside and outside is a salient one inJapanese culture. One never wears 3 outside shoes inside the house; instead these are left at the foyer which is at a lower level than the rest of the house. Only slippers, tabi,stockings-inside footwear-can be worn within the home. To do otherwise would be a fundamental breach of etiquette; in fact it would be unthinkable, un-Japanese. Inside/outside also signifies a 'mode' of behaviour-uchi (cf. UchiRoji) is the intimate in-group; soto is the outside, public world (cf. Kondo I982). It is what one offers to the ancestors, and is sometimes thought to have curative powers; it is 3 also closely associated with Buddhism. 35 Leach (I976) argues that patterning or redundancy helps the receiver understand the message being communicated. 36 Through capitalising on the qualities of the particular modes involved (e.g., the discursive nature of language, the simultaneity of visual stimuli, the palpability of objects). 37 This is a profound theme in Japanese culture, underlying pedagogy, definitions of person, maturity, role fulfilment, etc. See e.g., Kondo I982. 38 Lest the reader fear that I am spinning webs of fantasy, it does seem that this feeling of tranquillity and of losing oneself in the rules is in fact conveyed to the participants, however implicitly or imperfectly. One informant told me of her experience. Taking tea solely as a wifely art, she kept a diary of her feelings about the ceremony. Even at a young age, she felt that, once learned, the rules allowed her to think of greater things. In daily life minor matters and small decisions absorb one's conscious attention and energy. Ritual liberates one from the necessity of diverting energy to these trivialities, to learn the rules so completely that one's actions no longer occupy one's attention. Thus the powers of thought and feeling can be directed toward that which is truly meaningful.

REFERENCES

Bachnik, Jane I978. Inside and outside theJapanese household. Thesis, Harvard University. Barthes, Roland I970. L'empiredessignes. Geneva: Skira. I974. S/Z. New York: Hill & Wang. Bellah, Robert I957. Tokugawareligion.Boston: Beacon Press. Caudill, William & Helen Weinstein I969. Maternal care and infant behavior inJapan and America. Psychiatry I2-43. 32, Davidson, Georgie I970. Classicalikebana.New York: A. S. Barnes. Edwards, Walter I982. Something borrowed: wedding cakes as symbols in modern Japan. Am. Ethnol. 9, 699-7II. Fernandez,James W. I977. The performance of ritual metaphors. In The socialuse of metaphor (eds) D. Sapir & C. Crocker. Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press. Hasumi, Toshimitsu I962. Zen inJapaneseart. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Herrigel, Eugen I953. Zen in the artof archery.New York: Pantheon. Ishikawa, Sojin I976. An invitation to tea. ChanoyuQ. i6, 65-70. Jakobson, Roman I960. Linguistics and poetics. In Style in language(ed.) T. Sebeok. Cambridge, Mass.: M. I.T. Press. Kondo, Dorinne I982. Work, family and the self: a cultural analysis ofJapanese family enterprise. Thesis, Harvard University. Kuck, Lorraine I940. The artofJapanese gardens.New York: John Day. Langer, Suzanne K. I942. Philosophyin a new key. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press. Leach, Edmund I976. Cultureandcommunication. Cambridge: Univ. Press.

3o6

DORINNE KONDO

Lebra, Takie Sugiyama I 976. Japanesepatternsof behavior.Honolulu: Univ. Press of Hawaii. Levi-Strauss, Claude I969. The raw andthe cooked.New York: Harper & Row. Ludwig, Theodore M. I974. The way of tea: a religio-aesthetic mode of life. Hist. Relig. 14, 28-5o. 264, So-62. Maki, Fumihiko I979. Japanese city spaces and the concept of oku.Japan Architect Needham, Rodney I967. Percussion and transition. Man (N.S.) 2, 606-I4. Okakura, Kakuzo I964. The bookof tea. New York: Dover. Palmer, Allan I976. Temae:chaji:conclusion and variation. ChanoyuQ. I6, Seattle: Peacock, James L. I969. Society as narrative. In AmericanEthnologicalSociety Proceedings. Univ. of Washington Press. way of tea. Tokyo: Weatherhill. Sen, Soshitsu I979. Chado:theJapanese Tambiah, StanleyJ. I973. The form and meaning of magical acts. In Modesofthought(eds) R. Horton & R. Finnegan. London: Faber& Faber. of I979. A performative approach to ritual. In Proceedings the BritishAcademy65. London: Oxford Univ. Press. Tsunoda, Ryusaku, W. T. DeBary & Donald Keene (eds) i958. SourcesofJapanesetradition.New York: Columbia Univ. Press. Vogt, Evon Z. I977. On the symbolic meaning of percussion in Zinacanteco ritual.J. anthrop.Res.

33, 23 I-44.

Watys, Ala I957. The way of Zen. New York: Vintage.

You might also like

- PERSPECTIVES ON CONNOISSEURSHIP OF CHINESE PAINTING Excerpt PerspectivesDocument4 pagesPERSPECTIVES ON CONNOISSEURSHIP OF CHINESE PAINTING Excerpt PerspectivesClark StillmanNo ratings yet

- Denley 1992 ImprovisationDocument6 pagesDenley 1992 ImprovisationtheredthingNo ratings yet

- Sternberg Press - February 2017Document7 pagesSternberg Press - February 2017ArtdataNo ratings yet

- Dualism and PolarismDocument22 pagesDualism and PolarismNataša StepanovićNo ratings yet

- Edwards Objects of Affect, PhotographyDocument19 pagesEdwards Objects of Affect, PhotographySilvana Hooper100% (1)

- Computer Project 1: Assignment 1.1Document10 pagesComputer Project 1: Assignment 1.1Nelu TurcanuNo ratings yet

- Etruscan DictionaryDocument23 pagesEtruscan DictionaryHakki YazganNo ratings yet

- University of Hawai'i PressDocument22 pagesUniversity of Hawai'i PressAlina Diana BratosinNo ratings yet

- Role of Shamanism in Mesoamerican ArtDocument38 pagesRole of Shamanism in Mesoamerican Artsatuple66No ratings yet

- Spinoza and Deep EcologyDocument25 pagesSpinoza and Deep EcologyAnne FremauxNo ratings yet

- Tarot in The Waste LandDocument22 pagesTarot in The Waste LandaaeeNo ratings yet

- 'Psychical Distance' As A Factor in Art and An Aesthetic Principle.Document32 pages'Psychical Distance' As A Factor in Art and An Aesthetic Principle.Arturo SerranoNo ratings yet

- The Whole Earth ShowDocument7 pagesThe Whole Earth Showarber0No ratings yet

- Art & Design: Symbols: Guide For Teachers 4Document9 pagesArt & Design: Symbols: Guide For Teachers 4umeshkumarpnNo ratings yet

- Chinese Classical MusicDocument23 pagesChinese Classical MusicTafadzwaChinhavaNo ratings yet

- Ángela Gurría Nature Exalted: Miriam KaiserDocument5 pagesÁngela Gurría Nature Exalted: Miriam KaiserRemzije SylejmaniNo ratings yet

- Sloterdijk-Spheres in Cosmograms PDFDocument10 pagesSloterdijk-Spheres in Cosmograms PDFKatma VueNo ratings yet

- Wenzel - Image Buddha Icons Aniconic Traditions India ChinaDocument43 pagesWenzel - Image Buddha Icons Aniconic Traditions India ChinaCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- Fact Sheet Number #4 The Sustainable Aboriginal Spirituality of The Song LinesDocument30 pagesFact Sheet Number #4 The Sustainable Aboriginal Spirituality of The Song LinesNadam GuerraNo ratings yet

- Aboriginal Seasons PosterDocument1 pageAboriginal Seasons Posterapi-350027834No ratings yet

- Architecture and The Virtual PDFDocument208 pagesArchitecture and The Virtual PDFJm tmNo ratings yet

- Transforming The Invisible: The Postmodernist Visual Artist As A Contemporary Mystic - A Review Christine HaberkornDocument25 pagesTransforming The Invisible: The Postmodernist Visual Artist As A Contemporary Mystic - A Review Christine HaberkornJohn MichaelNo ratings yet

- The Visual Poetry of Chinese BambooDocument14 pagesThe Visual Poetry of Chinese Bamboogutax9No ratings yet

- Paul O'Neill. The Wrong Place: Rethinking Context in Contemporary ArtDocument5 pagesPaul O'Neill. The Wrong Place: Rethinking Context in Contemporary ArtMuladarNo ratings yet

- Vegetal Philosophy or Vegetal ThinkingDocument15 pagesVegetal Philosophy or Vegetal Thinkinggiorgister5813No ratings yet

- Ana Mendieta A Retrospective 1987 PDFDocument87 pagesAna Mendieta A Retrospective 1987 PDFDanut Radu SorinNo ratings yet

- 'Beacons in The Dark': Painted Murals of Amitābha's Western Pure Land at Dunhuang.Document39 pages'Beacons in The Dark': Painted Murals of Amitābha's Western Pure Land at Dunhuang.Freddie MatthewsNo ratings yet

- Sullivan, G. (2009) - Making Space. The Purpose and Place of Practice-Led Research. Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in The Creative Arts, 41-65.Document27 pagesSullivan, G. (2009) - Making Space. The Purpose and Place of Practice-Led Research. Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in The Creative Arts, 41-65.goni56509No ratings yet

- A New Interpretation of The Yao Charters: B Aren D J. TerhaarDocument15 pagesA New Interpretation of The Yao Charters: B Aren D J. Terhaartito19593No ratings yet

- Firth A Dart Match in Tikopia 1930 PDFDocument37 pagesFirth A Dart Match in Tikopia 1930 PDFKristina DobraNo ratings yet

- Geometry and Transfiguration-1. Octavio Paz About Rufino TamayoDocument15 pagesGeometry and Transfiguration-1. Octavio Paz About Rufino TamayoGrecia PérezCalderónNo ratings yet

- Matthew Conway Reading: Forms of Time and of The Chronotope in The Novel, BahktinDocument12 pagesMatthew Conway Reading: Forms of Time and of The Chronotope in The Novel, Bahktinrealtimecities100% (1)

- Paul Thek's Teaching NotesDocument16 pagesPaul Thek's Teaching Notesspitzko100% (1)

- Aesthetics and Utopian Possibility - Herbert Marcuse and The ArtsDocument4 pagesAesthetics and Utopian Possibility - Herbert Marcuse and The ArtsMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Baskets PDFDocument84 pagesBaskets PDFImml TasbiNo ratings yet

- RM Final Assignment Print OutDocument57 pagesRM Final Assignment Print OutHarshada ManeNo ratings yet

- A Capsule Aesthetic FeministDocument164 pagesA Capsule Aesthetic FeministDenise Bandeira100% (1)

- Nicolaas Johannes Krom - Life of Buddha On The Stupa of Barabudur, According To The Lalitavistara (Text, Plates) - The Hague, M. Nijhoff (1926) PDFDocument200 pagesNicolaas Johannes Krom - Life of Buddha On The Stupa of Barabudur, According To The Lalitavistara (Text, Plates) - The Hague, M. Nijhoff (1926) PDFAnonymous 4CZGb4RxNo ratings yet

- Flowers in Japanese CultureDocument18 pagesFlowers in Japanese CultureLeonardo PerdomoNo ratings yet

- Ex Voto: Faith Expressed in ArtDocument1 pageEx Voto: Faith Expressed in ArtcrbrunelliNo ratings yet

- Physiognomic Aspects of Visual Worlds (Aaarg 2698)Document9 pagesPhysiognomic Aspects of Visual Worlds (Aaarg 2698)Agastaya ThapaNo ratings yet

- Arts Based Research 2Document18 pagesArts Based Research 2api-257674266100% (1)

- Early Indian ArchitectureDocument82 pagesEarly Indian Architecturejagannath sahaNo ratings yet

- Intentional FallacyDocument21 pagesIntentional FallacyNilmalvila Blue Lilies PondNo ratings yet

- TheDocument46 pagesThefrederic9866No ratings yet

- Nepal - Early Paintings of The Goddess in NepalDocument16 pagesNepal - Early Paintings of The Goddess in NepalShankerThapaNo ratings yet

- Dance Notation, DomeniccoDocument119 pagesDance Notation, DomeniccoBarbara MalavogliaNo ratings yet

- Christopher Norris Platonism, Music and The Listeners Share Continuum Studies in Philosophy 2006Document209 pagesChristopher Norris Platonism, Music and The Listeners Share Continuum Studies in Philosophy 2006Stjepan PalajsaNo ratings yet

- Visual Culture: Norman Bryson, Michael Ann Holly, Keith MoxeyDocument19 pagesVisual Culture: Norman Bryson, Michael Ann Holly, Keith MoxeyJames ConnahNo ratings yet

- What Is PatternDocument3 pagesWhat Is PatternIriniNo ratings yet

- Unit-1 RELIGION - SACRED & PROFANE PDFDocument11 pagesUnit-1 RELIGION - SACRED & PROFANE PDFnehaNo ratings yet

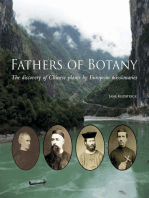

- Fathers of Botany: The Discovery of Chinese Plants by European MissionariesFrom EverandFathers of Botany: The Discovery of Chinese Plants by European MissionariesNo ratings yet

- Shove, E. (2012) - Habits and Their CreaturesDocument14 pagesShove, E. (2012) - Habits and Their CreaturesbrenderdanNo ratings yet

- Antennae Issue 53Document97 pagesAntennae Issue 53NATALIA ISABEL PEREZ VILLEGASNo ratings yet

- John Hennigar Shuh - Teaching Yourself To Teach With Objects PDFDocument6 pagesJohn Hennigar Shuh - Teaching Yourself To Teach With Objects PDFconvers3No ratings yet

- KODO Ceremonia Del InciensoDocument14 pagesKODO Ceremonia Del InciensoViviana HernándezNo ratings yet

- Tea Ceremony: The Way of TeaDocument4 pagesTea Ceremony: The Way of TeaMarie Anne Bachelor100% (1)

- Chanoyu The Japanese Tea CeremonyDocument6 pagesChanoyu The Japanese Tea CeremonyTasha ErNo ratings yet

- 3834 12791 1 PBDocument13 pages3834 12791 1 PBtanjossNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of Zen Buddhist Concepts Lying Behind The Ceremonies of The - Seven Rituals - Tea ComplexDocument6 pagesThe Meaning of Zen Buddhist Concepts Lying Behind The Ceremonies of The - Seven Rituals - Tea ComplexyipgwokhouNo ratings yet

- TeaCeremonyExplanation EnglishDocument8 pagesTeaCeremonyExplanation EnglishYumi SutcliffNo ratings yet

- Sen No RikyūDocument7 pagesSen No Rikyūbiba 4life100% (1)

- Kezelesi Utmutato Q3 RF 2010 AngolDocument12 pagesKezelesi Utmutato Q3 RF 2010 AngolClaudiu AdamNo ratings yet

- Introduction To GlobalizationDocument6 pagesIntroduction To GlobalizationJeselica Anne Marie CastroNo ratings yet

- Essay Types Character Analysis EssayDocument7 pagesEssay Types Character Analysis EssayFatihNo ratings yet

- Biology Form 5: 5.1: MENDEL'S ExperimentDocument29 pagesBiology Form 5: 5.1: MENDEL'S Experimentveronica francisNo ratings yet

- 2006 Philippines Road ClassificationDocument44 pages2006 Philippines Road ClassificationpetiepanNo ratings yet

- EASE Module 1 Geometry of Shape and SizeDocument27 pagesEASE Module 1 Geometry of Shape and Sizemonera mohammad0% (1)

- 04 - Organic SynthesisDocument45 pages04 - Organic SynthesisMerrene Bright Divino JudanNo ratings yet

- Analisis Potensi Dan Tingkat Pemanfaatan Sumberdaya Ikan Di Perairan Kabupaten Bangka SelatanDocument12 pagesAnalisis Potensi Dan Tingkat Pemanfaatan Sumberdaya Ikan Di Perairan Kabupaten Bangka SelatanShope IkmaNo ratings yet

- Module 2 (People and The Earth's Ecosystem)Document11 pagesModule 2 (People and The Earth's Ecosystem)chris ian0% (2)

- Epson m5799Document3 pagesEpson m5799leoNo ratings yet

- Test Report CMI, 200 Amp 35kV Class "Tuf-Ex-Well II" Bushing WellDocument8 pagesTest Report CMI, 200 Amp 35kV Class "Tuf-Ex-Well II" Bushing WellCristobal BohorquezNo ratings yet

- Week 1: Introduction: NM NM Ev Ev E DT T P EDocument9 pagesWeek 1: Introduction: NM NM Ev Ev E DT T P EInstituto Centro de Desenvolvimento da GestãoNo ratings yet

- General Twin Seal 06Document24 pagesGeneral Twin Seal 06Gk GaneshNo ratings yet

- TheDocument12 pagesTheVictor PileggiNo ratings yet

- Drug Information and Poison InformationDocument6 pagesDrug Information and Poison Informationsri deepika sri deepikaNo ratings yet

- Script For FNBDocument5 pagesScript For FNBRaven Grace D. De MesaNo ratings yet

- Valorisation of Spent Coffee Grounds Production of Biodiesel Via Enzimatic Catalisis With Ethanol and Co-SolventDocument14 pagesValorisation of Spent Coffee Grounds Production of Biodiesel Via Enzimatic Catalisis With Ethanol and Co-SolventAline GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Tulip CRP TurbiDocument1 pageTulip CRP Turbirahul kumarNo ratings yet

- Youjo Senki Side Story - A Borrowed Cat (v1.1)Document11 pagesYoujo Senki Side Story - A Borrowed Cat (v1.1)faiyaNo ratings yet

- Lab 7 QUBE-Servo PD Control WorkbookDocument6 pagesLab 7 QUBE-Servo PD Control WorkbookLuis EnriquezNo ratings yet

- 320 Lecture 27Document8 pages320 Lecture 27Gathy BrayohNo ratings yet

- Circuito Integrado BA05STDocument10 pagesCircuito Integrado BA05STEstefano EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Q1. As A Production Manager For RMC, What Do You Recommend? Why??Document2 pagesQ1. As A Production Manager For RMC, What Do You Recommend? Why??MUNSIF JAWEEDNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3: Task #1 Has (10 Parts) That Corresponds To CLO # 2 For A Total of 30 PointsDocument2 pagesAssignment 3: Task #1 Has (10 Parts) That Corresponds To CLO # 2 For A Total of 30 PointsWaqas AliNo ratings yet

- Comparison of The Ratios of Coca Cola and PepsiDocument6 pagesComparison of The Ratios of Coca Cola and PepsiassadullahNo ratings yet

- Unit Two. Dominant Theories Approaches: Positivism Rational Choice Theory MarxismDocument8 pagesUnit Two. Dominant Theories Approaches: Positivism Rational Choice Theory MarxismPaul RicoNo ratings yet