Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ccijnews 49

Ccijnews 49

Uploaded by

Ayla AzuraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ccijnews 49

Ccijnews 49

Uploaded by

Ayla AzuraCopyright:

Available Formats

August, 2006

No.49

Consumer Co-operative Institute of Japan

Plaza F 15, Rokubancho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0085, Japan Tel. 81-3-5216-6025 Fax. 81-3-5216-6030 ccij@jccu.coop http://www.co-op.or.jp/ccij/

M ain F eatures

The Emerging Third Sector in Asia KURIMOTO, Akira: Director, CCIJ

Tradition of Mutual Help and Philanthropy Mingled with Foreign Influence

Asias third sector is enormous in number and varied in content. In all countries there are strong traditions of both mutuality and philanthropy. In most countries, there is a long tradition of village level mutual aid activities; often to manage commonly held resources such as irrigation and commons. Also there are strong religious traditions providing social services and charity to help the disadvantaged members of the community through giving and volunteering. These traditional elements have provided the basic substructure of the third sector. They have survived to some extent and are now mingled with foreign influences in the formation of contemporary organizations. i

Contents; Main Features:

The Emerging Third Sector in Asia by KURIMOTO, Akira: Director, CCIJ

News in Brief:

1-8 9-10

CCIJs Scholarship programme for Future CEOs launched in April CCIJs Publication and Colloquium on Consumer Co-op Studies JSCS Conference Discussed on Co-operative Insurance Inter-university Colloquium on Social/Solidarity Economy 26th CIRIEC Congress in Istanbul

Page 2

CCIJ News No.49 March 2006

For example, in India the inheritance of the British common law tradition, cultural diversity, huge regional variations, and a federal system of government have all combined to encourage a wide variety of third sector organizations. Bangladesh is the home to a number of famous NGOs supported wholly or partially by overseas aid due in part to its Islamic heritage of mutual help. In Thailand, where Buddhism underpins the strong tradition of reciprocity, there are many traditional organizations built around villages and temples. In the Philippines, Catholicism remains deeply rooted in the popular psyche and the third sector has grown rapidly since the middle class overthrew an unpopular regime through a widely ramified network of NGOs. In Korea, which was colonized by Japan and dominated by Confucian traditions, many people adopted Protestant Christianity from the U.S. missionaries along with various charitable institutions and credit unions. ii

Co-operatives as Agents for Socio-economic Development

In Asia and the Pacific region the colonial and post-colonial governments have promoted co-operatives to attain their goals of socio-economic development. The European co-operative idea was imported into the British colonies in 19th century. In Australia some of Robert Owens utopian methods were tried among emancipated convicts in the Hunter Valley as early as the 1820s and a variety of production and retail co-ops were set up by the 1830s when free immigrants began to arrive. Co-operative ideas then came to Japan with the first consumer coops created on the Rochdale model in 1879 while the government directed farmers to set up credit co-ops (along Raiffeisen lines), marketing, purchasing, and production/service co-ops, all of which were recognized by the Industrial Cooperative Law in 1900. But the legislation that brought far-reaching impact was the Co-operative Credit Societies Act of 1904 installed in India by the British Empire. It aimed to check farmers enslavement to moneylenders and support Raiffeisen-style agricultural credit co-ops. Because there was no indigenous support for co-operative ideas, it had to be promoted by a special government agency headed by a registrar with supreme power. This classic British-Indian pattern spread throughout the British colonies and became the prototype for co-operative legislation in developing countries.iii This highly authoritarian or top-down approach by co-operative registrars or ministers was inherited by new independent governments, which promoted cooperatives as an engine for national development. As most Asian countries were agrarian before industrialization took off in the 1970s, agricultural co-ops were promoted as a way of modernizing rural economies. Birchall distinguished between two phases of development. The first, lasting until around 1960, was characterized by a top-down, blue-print based approach, with the new co-operative sector being organized by the state. In China, multipurpose village co-ops achieved considerable success in the early 1950s, until they were turned, by decree, into Peoples Communes, which led to catastrophic famine. In Malaysia, agricultural, and non-agricultural and fishery co-ops were sponsored and controlled

Page 3

CCIJ News No.49

by different authorities. In India, co-operatives received a tremendous boost after independence in 1947 when the government decided to promote all forms of cooperatives through contributing share capital, seconding officers as CEOs and setting up powerful development agencies. In Iran, multipurpose agricultural co-ops were set up and supervised by a central body with direct assistance from the government. The second phase from the 1960s onward was accompanied by a change of emphasis. Against a background of economic growth and rapid urbanization in some countries, co-operatives were expected to become a major tool for rural development. To enable them to fulfill this ambitious role, widespread amalgamations between co-ops were promoted by state subsidies or brought about by government decree. In most countries federal bodies were created and their leaders nominated by governments. Through this process some powerful organizations including Zennoh, Zenkyoren, Norinchukin Bank (Japan), NACF (Korea) and IFFCO (India) emerged.iv In this sector the Japanese IDACA (Institute for the Development of Agricultural Co-operation in Asia) has been a major provider of technical assistances using the ODA fund. Globalization and deregulation, has brought about unprecedented impact on agricultural co-ops after the late 1980s, which have been under pressure from lowered trade barriers and increased competition from foreign food imports. Agricultural co-ops have also faced intense competition in domestic markets losing monopoly or dominant positions through a number of deregulation measures affecting the transaction of goods and services. They have faced government structural adjustment policies which urged withdrawal of public subsidies and preferential treatment although the government did not necessarily give up control of cooperatives. To cope with this situation and facilitate necessary changes to cooperative legislation and policy, the ICA ROAP has convened a biannual Cooperative Ministers Conferences (CMC) since 1990, while the UNs Co-operative Guidelines in 2000 and ILOs new Recommendation 193 on the Promotion of Cooperatives in 2001 set out guidelines for the governments co-operative policy to promote co-operative autonomy and forge equal partnership. But state withdrawal from control of co-operatives has occurred at different rates in different places. The ICAs critical study on co-operative legislation and policy reforms revealed that progress on implementation of the CMC resolutions has been rather slow and has needed time to gather momentum in many countries while government control over co-ops continues and is still prevalent in some countries which places them at a disadvantageous position in comparison with the private sector.v

CCIJ NEWS

August, 2006 No.49

Page 4

CCIJ News No.49 March 2006

In contrast, governments have paid much less attention to urban consumer co-ops or financial co-ops although the registrars have exercised dictating power over them. In the consumer sector the development has been very slow except for Japan and Singapore. This has been attributable to their small size, weak member participation, and shortage of capital, lack of managerial capacity and an effective federative system. In some countries the shift from a regulatory to a market economy has brought both threats and chances. Such is the case of the Indian consumer co-ops which faced stiff competition after losing their monopoly in trading basic commodities while Saigon Co-op established itself as a major supermarket chains in the past 10 years. In this respect, the KF Project center and the JCCU are extending technical assistances to this sector. As for the financial sector, there are co-operative banks and credit unions in many countries. They provide financial services to members ranging form micro-credit at the grassroots to full-fledged services through regional and national networks such as CUSCAL, Australia. Also, strong insurance co-ops exist in Singapore and Malaysia. In this sector, Canadian co-ops have extended technical assistances through the Canadian Co-operative Association and Desjardin International. In addition to these traditional co-ops, there are specific types of co-ops in Asia. Medical co-ops have been organized by users (Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and Singapore) and providers (India, Malaysia, Mongolia and Sri Lanca) to provide medical services at hospitals and clinics. The JCCUs Health Cooperative Association has offered technical assistance and formed a regional network. University co-ops have been organized mainly by faculty members to provide text books, food, appliances and credit/insurance for faculty and students. The National Federation of University Co-ops (NFUCA) of Japan has extended technical assistances to the university co-ops and have persuaded them to involve students as full-fledged members. Womens co-ops have been formed exclusively by women in India, Iran and Malaysia to encourage them to take leadership positions, which would be difficult in co-ops with mixed membership, or on religious grounds. Recently new worker co-ops were born to create employment and cater to the unattended needs that have developed since the 1980s. They have sought to fill the gap of welfare provision, which had been organized in the families/communities and supplemented by religious groups. As a whole, Asian co-operatives are obliged to strengthen autonomy and independence, and improve governance and management. They need to adapt to the shift in public policy from protectionist to pro-competition under the pressure of globalization.

Page 5

CCIJ

News

No.49

Non-profits Proliferating as an Actor in the Civil Society

In Asia, the third sector is often associated with a small groups commonly referred to as NGOs. In fact, NGOs are the dominant type of nonprofits in Asia. Most of the NGOs are wholly or partially supported by overseas aid from both governmental and non-governmental agencies, which are mainly financed by the official development assistance programs of the OECD countries or international organizations like the United Nations and its specialized agencies. This way of financing has the tendency to lead to the development of dependent cultures and disguises the development of truly independent organizations. In fact, there are many NGOs, which would not be able to survive without foreign support. But to focus on the development NGOs that have been sustained by such aid is to miss much of Asias third sector. vi As mentioned before, most countries in the region have witnessed extremely rapid growth and the emergence of a civil society in recent decades. Nonprofits or NGOs are proliferating in many countries regardless of the countrys stage of economic development, degree of democratization or form of government. As a background to such evolution, the limits of a governments ability to cope with the numerous and increasingly complex socio-economic issues are increasingly recognized, and as a result bureaucrats have started to turn to civil society organizations (CSOs) to shoulder greater responsibility to serve public interests. In China, with the reform of the entire economic system including the privatization of state-owned enterprises and the transition to a kind of market economy, the government is no longer able to bear the social burden and is gradually delegating responsibility to the society through community/social organizations and other groups. In Taiwan, CSOs have become more involved in providing services directly to disadvantaged groups, thus taking on a responsibility previously exclusively assumed by the government. In Bangladesh, a robust growth of NGOs in many areas of intervention such as micro-credit, womens empowerment and primary education, has gained global attention and there is a growing recognition of the sectors important contribution to development, especially for the poor, vulnerable and disadvantaged in the society. In Pakistan, the growing size and number of organizations has gained increased recognition and influence over CSOs. In the Philippines, NGOs have continued to show great influence in socio-political life as demonstrated by the peaceful ousting of a corrupt president and the governments recognition of the NGOs as an extension of people power by enshrining them into the Constitution. These examples illustrate that CSOs are increasingly becoming involved in the task of improving the governance of each society, which is reinforcing the changing relationship between the public sector and the third sector and putting strong pressure on CSOs to improve their effectiveness in carrying out their missions as they are expected to fill the widening gap of social needs that have been left unattended. vii

Page 6

CCIJ News No.49 March 2006

The growing role of nonprofits and NGOs, in areas once considered to be the exclusive domain of government bureaucracy, however, has naturally given rise to considerable tension in the relationship between the public sector and the third sector in Asian countries. This can be attributed to the dramatic rise of CSOs in a relatively short period of time, on the one hand, and the continuing dominance of traditional state-centric power structures over public interest, on the other. Governments have shown that they want to harness their power for their own purposes rather than allowing them to become reliant on CSOs. There is a growing concern among CSO leaders that government bureaucracy will attempt to recapture their control over CSOs through regulatory actions that ostensibly target the need for greater accountability and transparency in the nonprofit sector. In fact, the growing pressure on CSOs from the public, the media and donors to improve internal governance on the ground that they are major players has proven to be a convenient excuse for government bureaucrats to strengthen their control over NGOs and nonprofits. With the higher profile of CSOs, there have been more revelations of financial and other irregularities within CSOs that have made such government intervention appear to be desirable.viii Therefore, nonprofits and NGOs are facing ambivalent attitudes on the part of their governments in many parts of the region. While they may have growing support among government officials, they may also face stronger supervision as government influence expands. Faced with such a situation where the governments perspective on CSOs is in a precarious balance and their leaders and researchers are unanimously opposed to stronger government control the critical contributions that CSOs have started making toward better governance of the society may be undermined. At the same time, there is a growing sense of urgency among Asian countries about the need to strengthen their own internal governance with greater emphasis on accountability and transparency.ix They may create autonomous self-regulating bodies to strengthen governance practices. In the Philippines, an umbrella organization, which had encouraged its members to adopt good management and governance practices via an accreditation scheme, successfully lobbied the government to retain tax deductions for donations to organizations that were properly accredited when a new tax bill threatened to remove all tax deductions. Thus the Philippine Council for NGO Certification (PCNC) was born. NGOs certified by the PCNC are eligible for tax exemptions while corporate donors can claim tax reductions only for donations to organizations that have been accredited through this process.x

Page 7

CCIJ

News

No.49

Creating Asian Models but Slow Integration of Third Sector

Asian third sector organizations had been created under strong influence from the west. This does not mean, however, that they are just copies of their western forerunners; rather they have evolved into Asian entities adapting to the existing political regimes, socio-economic structures and traditional cultures. Also, distinct Asian models have also been created which have impacted other regions. For example, the Amul dairy co-operatives in India provided a model for a development program that began in 1965 that was termed the white revolution. This program, which was highly integrated into the village, district and state levels, and under members control proved to be a system, which effectively offered every necessary service. Furthermore, Grameen Bank in Bangladesh was praised as a successful formula for micro-credit co-ops and empowerment of the poor at the grassroots level by the World Bank and its model has been diffused to many parts of the third world. The NTUC Fairprice and NTUC Income in Singapore became the showcase of trade union based consumer and insurance coops. Japans multi-purpose agricultural co-ops were once commended as an example of a co-operative community by Dr. Alex Laidlaw in his report to the ICA Moscow Congress (1980) while Han groups within Japanese consumer co-ops were seen as a model of member participation by Mr. Sven Ake Book in the ICA Tokyo Congresses (1992). These models were more or less copied in Korea and Taiwan. But all these cases have been so deeply embedded in the socio-economic environment and local culture that their impact on the west has been rather limited. At the regional level the consolidation of the third sector is very slow except for co-operatives and credit unions. The ICA established its first regional office in New Delhi in 1960. Today the ICA Asia Pacific Region consists of 55 national organizations from 22 countries, representing 61% of co-operators in the world. The ICMIF set up its Asia and Oceania Association (AOA) in 1984, composed of 26 insurance co-ops in 13 countries. The Asian Confederation of Credit Unions (ACCU), set up in 1971, covers 15 credit union centrals in 13 countries. In the voluntary or nonprofit sector, national groupings are underway in some countries, but their diversity hampers the creation of federal bodies at the regional level except for network organizations such as the Asian NGO Coalition (ANGOC) founded in 1979 and the Asia Pacific Philanthropy Consortium (APPC) created in 1994.

Page 8

CCIJ News No.49 March 2006

Governments, academics and the media in Asia do not, for the most part, recognize the concept of a third sector. The integration process of the sector is therefore not visible in most countries, while the third sector is most often equated with the voluntary/nonprofits sector. Nonprofits often see co-operatives as state-sponsored bureaucratic organizations, while the latter sees the former as heavily dependent entities relying on the public or foreign money. Between the South and the North there exists some sporadic examples of collaboration such as fair trade bananas from Philippine producers to Japanese consumers, but their impact is very limited.

Notes i. Samiul Hasan and Mark Lyons eds. Social Capital in Asian Sustainable Development Management, Nova Science Publishers, Inc. New York, 2004 ii. ibid. iii. J. Birchall, The International Co-operative Movement, Manchester University Press, 1997, pp.163-166. iv. ibid. pp.167-177. v. P.V.Prabhu, Third Critical Studies on Co-operative Legislation and Policy Reforms, ICA ROAP, 2004, pp.1-19. vi. Hasan and Lyons, pp. 1 vii. T. Yamamoto, Overview of Twelve Country/Region Studies, APPC Conference Papers on September 5-7, 2003, Manila, pp.3-5. viii. ibid. pp.5-8. ix. ibid. pp.5-8. x. Hasan and Lyons, pp. 3-4.

CCIJ NEWS

August, 2006 No.49

Page 9

CCIJ News No.49 March

News in Brief

CCIJs Scholarship programme for Future CEOs launched in April

Mr. Akira Uchitate passed away in October 2005 after serving consumer co-ops for more than 40 years. He made major contribution to the movement such as the founding of Miyagi Co-op, the introduction of reforms in the JCCU and rescuing the ailing Co-op Sapporo. He endowed CCIJ with a lump sum to create a Scholarship Fund for Future Consumer Co-op CEOs. CCIJ will administrate the scholarship programme for trainees who will attend MBA courses at universities.

CCIJs Publication and Colloquium on Consumer Co-op Studies

The CCIJ has sought to create consumer co-op studies as a distinct field since 2000. In this endeavor it has organized study groups involving both researchers and practitioners. In June, 2005 CCIJ published a volume entitled Search for Consumer Co-op Studies consisting of chapters analyzing the current status of consumer co-ops in Japan. The second volume was published as an anthology of theoretical essays in May 2006. In commemoration of these publications CCIJ organized a colloquium on May 17th in Tokyo. Chairperson Hasumi introduced the concept of consumer co-op studies. Ms. Chikako Futamura of the JCCU then made a presentation on the changing consumer consciousness and members activities. Prof. Shuji Tai, President of Chiba Co-op, presented a report on how co-op business is responding to such changes. Mr. Kazuhiro Yano, the JCCU CEO, commented on these presentations. Mr. Takeyoshi Fujioka, MD of CCIJ, moderated the ensuing discussion. The CCIJ Board members and authors of the volumes attended this colloquium.

JSCS Conference Discussed on Co-operative Insurance

The Japan Society for Co-operative Studies (JSCS) held its 25th Annual Spring Conference on May 20 at the JA building in Tokyo. This years symposium was moderated by Professor T. Oshio of Meiji University who is a specialist on cooperative insurance. The Japanese insurance co-ops are regulated by co-operative laws for farmers, consumers and SMEs respectively and have demonstrated strong growth in the last decade eating into the market shares of private insurance companies, which insisted that co-operative insurance come under the Insurance Business Law on the ground of equal footing. The conference focused on examining legal and institutional problems together with the international comparisons.

Page 10

CCIJ News No.49 March 2006

News in Brief

Inter-university Colloquium on Social/Solidarity Economy

The annual colloquium on Social and Solidarity Economy (ESS) was held in Grenoble on June 1-2 where a number of papers were presented on the theme ESS and Europe: Which Future? Mr. Kurimoto of CCIJ made a contribution on the Asian viewpoint of ESS. The colloquium, which began in 2001, is organized by an inter-university network of Franco-phone researchers, but this colloquium had an international dimension comparing experiences in different countries and regions. For more information, please contact the organizer; Daniele.Demoustier@iep.upmf-grenoble.fr

26th CIRIEC Congress in Istanbul

The biannual International Congress of CIRIEC was held in Istanbul on June 19-21 with the theme The Public, Social and Cooperative Economy in the Context of Globalization. It attracted approximately 700 political/business leaders and researchers from 30 countries. In the plenary session, Prof. A. Ben-Ner of Minnesota University. delivered a speech on Globalization and the Changing Role of the Nonprofit Sector. Ten round tables were organized to encourage debates between panelists and the audience. Mr. Kurimoto was a panelist in the round table on agricultural co-ops. The next international research conference on social economy will be held in Victoria, Canada, in October 2007 and this will be followed by a Congress in Seville, Spain, in September 2008. At the General Assembly, Mrs. L. Detiege was reelected President.

CCIJ NEWS

August, 2006 No.49

You might also like

- The Essentials of Psychodynamic PsychotherapyDocument6 pagesThe Essentials of Psychodynamic PsychotherapyMarthaRamirez100% (3)

- Fundamentals of CooperativeDocument16 pagesFundamentals of Cooperativewilliam penalverNo ratings yet

- Non Aero Revenue - MBA ProjectDocument68 pagesNon Aero Revenue - MBA ProjectSuresh Kumar100% (2)

- The Place of Cooperative in National Development in The 21st CenturyDocument6 pagesThe Place of Cooperative in National Development in The 21st CenturyEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument13 pagesAssignmentAftab UddinNo ratings yet

- Cooperative V200Document19 pagesCooperative V200Marcos, Jayven B.No ratings yet

- Savings and Credit Cooperatives in Ethiopia - Development and ChallengesDocument8 pagesSavings and Credit Cooperatives in Ethiopia - Development and ChallengesDagmay GebeyehuNo ratings yet

- Chapter One Impact of Cooperatives On MembersDocument38 pagesChapter One Impact of Cooperatives On MembersDONEKE MIRACLENo ratings yet

- From Credit Unions To Credit To Multi-Purpose CooperativesDocument28 pagesFrom Credit Unions To Credit To Multi-Purpose CooperativesromyvilNo ratings yet

- Corporate Philanthropy in Asia: The Philippine CaseDocument24 pagesCorporate Philanthropy in Asia: The Philippine CaseRuby GarciaNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Management Unit 1Document9 pagesCooperative Management Unit 1Junior De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Co-Op 10 PDFDocument10 pagesCo-Op 10 PDFSenelwa AnayaNo ratings yet

- The Federations of Free Farmers CooperativesDocument3 pagesThe Federations of Free Farmers CooperativesJayson ChanNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Societies WriteupDocument8 pagesCooperative Societies WriteupSagargn SagarNo ratings yet

- Emerging Trends in Cooperative MovementDocument8 pagesEmerging Trends in Cooperative MovementShally May Estrella OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Cooperative Society.Document12 pagesAssignment On Cooperative Society.Aftab Uddin67% (3)

- Cooperative AssignmentDocument9 pagesCooperative AssignmentÜm Yöñí Åvïd GödNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Cooperative SocietyDocument12 pagesAssignment On Cooperative SocietyAnkit KumarNo ratings yet

- Voluntary Org Planning Commission Strategy PaperDocument69 pagesVoluntary Org Planning Commission Strategy Paperamarnath61No ratings yet

- Defining The Social Economy - The BC Context John RestakisDocument16 pagesDefining The Social Economy - The BC Context John RestakisKaren gutierrezNo ratings yet

- Global University Bangladesh: An Assignment OnDocument9 pagesGlobal University Bangladesh: An Assignment OnshababNo ratings yet

- Coproduction of Community Public Service: Evidence From China's Community FoundationsDocument21 pagesCoproduction of Community Public Service: Evidence From China's Community Foundationsags.supriyanto1745No ratings yet

- COoperative Bank ProfileDocument7 pagesCOoperative Bank ProfileAnonymous QrLiISmpFNo ratings yet

- CooperativeDocument3 pagesCooperativeDonna Mae BaonNo ratings yet

- Mobilizing against Inequality: Unions, Immigrant Workers, and the Crisis of CapitalismFrom EverandMobilizing against Inequality: Unions, Immigrant Workers, and the Crisis of CapitalismLee H. AdlerNo ratings yet

- Future of Cooperatives in IndiaDocument5 pagesFuture of Cooperatives in IndiaAnandaNo ratings yet

- Rural Financial InstitutionsDocument20 pagesRural Financial InstitutionsJayadatta Shreepada SNo ratings yet

- History of CoopDocument23 pagesHistory of CoopMarites Domingo - PaquibulanNo ratings yet

- Agricultural CooperativesDocument6 pagesAgricultural CooperativesOMOTOSO AJEWOLENo ratings yet

- Investment Opportunities in The Rural Areas Through Cooperative and Agricultural EnterprisesDocument8 pagesInvestment Opportunities in The Rural Areas Through Cooperative and Agricultural EnterprisesPst W C PetersNo ratings yet

- Savings and Credit Cooperative Societies (SACCOS) As A Source of Financing Agriculture. Challenges and Lessons LearntDocument6 pagesSavings and Credit Cooperative Societies (SACCOS) As A Source of Financing Agriculture. Challenges and Lessons LearntYonas Adugna YonasNo ratings yet

- History of NgosDocument11 pagesHistory of NgosRithicka M INo ratings yet

- Module 11, Civil Society and Social MovementsDocument16 pagesModule 11, Civil Society and Social MovementsJulius BrillantesNo ratings yet

- Economic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyDocument6 pagesEconomic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyButterfly DiaryNo ratings yet

- Co-Operative Organizations As A Means of Poverty Alleviation and Rural Community Development in NigeriaDocument17 pagesCo-Operative Organizations As A Means of Poverty Alleviation and Rural Community Development in NigeriaOkafor PrinceNo ratings yet

- Module 4 ContempDocument5 pagesModule 4 ContempMonkey D DragonNo ratings yet

- Microfinance in India Scopes and LimitationsDocument41 pagesMicrofinance in India Scopes and Limitationsspy67% (3)

- Explain The Functions of Cooperatives and Their Role in Development.Document4 pagesExplain The Functions of Cooperatives and Their Role in Development.vincentNo ratings yet

- CIVICUS CSinVietnam DraftpaperDocument5 pagesCIVICUS CSinVietnam Draftpaperapi-26649203No ratings yet

- 4th Tier Government and Cooperative Development in Imo StateDocument3 pages4th Tier Government and Cooperative Development in Imo StateRaphael OnuohaNo ratings yet

- The History of Cooperative Movement in VillaDocument3 pagesThe History of Cooperative Movement in VillaonlyvictoryNo ratings yet

- Japan, Land of CooperativesDocument5 pagesJapan, Land of CooperativesFadhli RamadhanNo ratings yet

- RM Unit3Document22 pagesRM Unit3diwakaranurag20No ratings yet

- Cooperatives As Drivers of Rural EconomyDocument13 pagesCooperatives As Drivers of Rural EconomyAkubuike EluwaNo ratings yet

- Sub Acfid Brief1Document14 pagesSub Acfid Brief1Mohamud OmarNo ratings yet

- The Role of Cooperative Societies in Economic Development: Munich Personal Repec ArchiveDocument21 pagesThe Role of Cooperative Societies in Economic Development: Munich Personal Repec ArchiveBiruktawite SolomonNo ratings yet

- History of Co Operative Movement in IndiaDocument2 pagesHistory of Co Operative Movement in Indiagmsreddy_bsr1890% (1)

- Case 1 The Caribbean Cooperative MovementDocument4 pagesCase 1 The Caribbean Cooperative MovementReina TampelicNo ratings yet

- Building Sustainable Farmer Cooperatives in The Mekong Delta, Is Social Capital The KeyDocument19 pagesBuilding Sustainable Farmer Cooperatives in The Mekong Delta, Is Social Capital The KeyTNo ratings yet

- 09 - Chapter 1Document27 pages09 - Chapter 1Delete SinghNo ratings yet

- Chapter-Ii Review of LiteratureDocument38 pagesChapter-Ii Review of LiteratureMubeenNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument16 pagesUntitledmartha kamaraNo ratings yet

- History and Evolution of Cooperatives in IndiaDocument5 pagesHistory and Evolution of Cooperatives in Indiasirajbloch100% (1)

- Cooperatives and Economic Growth in Indonesia: Muhammad HalilintarDocument12 pagesCooperatives and Economic Growth in Indonesia: Muhammad HalilintarViken Alfi TaniaNo ratings yet

- IntrouctionDocument24 pagesIntrouctionbaghidai बाघिदाइNo ratings yet

- NgosinpakistanDocument18 pagesNgosinpakistanFinal ProjectNo ratings yet

- Rjj$-Sejv .zv6 Zy)Document21 pagesRjj$-Sejv .zv6 Zy)Serenity ManaloNo ratings yet

- 2013 China Social Enteprise and Impact Investment ReportDocument119 pages2013 China Social Enteprise and Impact Investment ReportchelseaavpnNo ratings yet

- Explain The Functions of Cooperatives and Their Role in Development.Document5 pagesExplain The Functions of Cooperatives and Their Role in Development.vincentNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Management Topic 1 4Document11 pagesCooperative Management Topic 1 4Jennia SantosNo ratings yet

- Credit and Thrift Co-Operatives in NigeriaDocument6 pagesCredit and Thrift Co-Operatives in NigeriaAbu FadilahNo ratings yet

- Fathers Work for Their Sons: Accumulation, Mobility, and Class Formation in an Extended Yoruba CommunityFrom EverandFathers Work for Their Sons: Accumulation, Mobility, and Class Formation in an Extended Yoruba CommunityNo ratings yet

- New Hardcore 3 Month Workout PlanDocument3 pagesNew Hardcore 3 Month Workout PlanCarmen Gonzalez LopezNo ratings yet

- Intrnship Report On WapdaDocument106 pagesIntrnship Report On WapdaNarain MenghwarNo ratings yet

- Test Taker Score Report: Prabhakar Thapa MagarDocument1 pageTest Taker Score Report: Prabhakar Thapa MagarRosy BasnetNo ratings yet

- Pengkarya Muda - Aliah BiDocument7 pagesPengkarya Muda - Aliah BiNORHASLIZA BINTI MOHAMAD MoeNo ratings yet

- CONSTITUTIONAL - CHANGES - TO - BE - MADE - pdf-SOME IMPORTANT CHANGES TO BE MADE IN THE LANKAN PDFDocument32 pagesCONSTITUTIONAL - CHANGES - TO - BE - MADE - pdf-SOME IMPORTANT CHANGES TO BE MADE IN THE LANKAN PDFThavam RatnaNo ratings yet

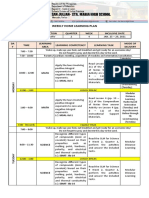

- Weekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateDocument3 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateMarvin Yebes ArceNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs October 2013kDocument76 pagesCurrent Affairs October 2013kKanthi Rekha VardhiNo ratings yet

- APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION/ACCREDITATION AS AN ECOZONE SERVICE ENTERPRISE (For Customs Broker, Freight Forwarder/Trucker and Security Agency)Document7 pagesAPPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION/ACCREDITATION AS AN ECOZONE SERVICE ENTERPRISE (For Customs Broker, Freight Forwarder/Trucker and Security Agency)Albert YsegNo ratings yet

- Courtney Downs June 06Document54 pagesCourtney Downs June 06MarcyNo ratings yet

- Enya Ukuleles - Enya Music UsaDocument1 pageEnya Ukuleles - Enya Music Usav9zmmt9g7hNo ratings yet

- Heirs of John Sycip vs. CA G.R. No. 76487 November 9 1990Document3 pagesHeirs of John Sycip vs. CA G.R. No. 76487 November 9 1990Mariel D. Portillo100% (1)

- The Quiescent Benefits and Drawbacks of Coffee IntakeDocument6 pagesThe Quiescent Benefits and Drawbacks of Coffee IntakeVikram Singh ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2: Sampling and Probability SamplingDocument11 pagesPractical Research 2: Sampling and Probability SamplingJohn Joseph JalandoniNo ratings yet

- HNDIT 1022 Web Design - New-PaperDocument6 pagesHNDIT 1022 Web Design - New-Paperravinduashan66No ratings yet

- Gentrification in Color and TimeDocument38 pagesGentrification in Color and TimeBNo ratings yet

- PhysioEx Exercise 1 Activity 4Document3 pagesPhysioEx Exercise 1 Activity 4CLAUDIA ELISABET BECERRA GONZALESNo ratings yet

- Ed Batista Self Coaching Class 6 Slideshare 150505182356 Conversion Gate02 PDFDocument34 pagesEd Batista Self Coaching Class 6 Slideshare 150505182356 Conversion Gate02 PDFSyed WilayathNo ratings yet

- Deed of DonationDocument2 pagesDeed of DonationMary RockwellNo ratings yet

- Autocad Layout Tutorial - EhowDocument3 pagesAutocad Layout Tutorial - EhowdidlakiranNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice - JOCDocument14 pagesMultiple Choice - JOCMuriel MahanludNo ratings yet

- Nitish SharmaDocument59 pagesNitish SharmaannnnmmmmmNo ratings yet

- Process of Concept Formation: ReferencesDocument1 pageProcess of Concept Formation: ReferencesRamani SwarnaNo ratings yet

- Drill #1 With RationaleDocument12 pagesDrill #1 With RationaleRellie CastroNo ratings yet

- Bac 1624 - ObeDocument4 pagesBac 1624 - ObeAmiee Laa PulokNo ratings yet

- Year 8 English: Examination - Semester 2, 2017 EXAM BookletDocument23 pagesYear 8 English: Examination - Semester 2, 2017 EXAM BookletJayaletchumi Moorthy100% (1)

- Assignment in Research 1Document7 pagesAssignment in Research 1cpmac123No ratings yet

- T-Systems CPNI Policy Statement - Final 022717 PDFDocument2 pagesT-Systems CPNI Policy Statement - Final 022717 PDFFederal Communications Commission (FCC)No ratings yet

- Mindanao Geothermal v. CIRDocument22 pagesMindanao Geothermal v. CIRMarchini Sandro Cañizares KongNo ratings yet