Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Ring of Gyges For Gethics

The Ring of Gyges For Gethics

Uploaded by

Lei Anne GacayanCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Republic - AbridgedDocument18 pagesThe Republic - AbridgedDaniel BalurisNo ratings yet

- Science Week Proposal 2 JuneDocument26 pagesScience Week Proposal 2 Junecsanjeevan100% (1)

- I Ching TesseractDocument14 pagesI Ching Tesseractthoth11100% (1)

- NTPCDocument158 pagesNTPCAnand GuptaNo ratings yet

- 07 Egoism PDFDocument6 pages07 Egoism PDFDMCañonNo ratings yet

- Aristotle On The Value of Friendship As A Motivation For MoralityDocument20 pagesAristotle On The Value of Friendship As A Motivation For Moralitya280872No ratings yet

- Gyges ADocument9 pagesGyges AHamza Saif RanjhaNo ratings yet

- Ethical EgoismDocument3 pagesEthical EgoismstacyshackNo ratings yet

- Moral Philosophy, Pojman & Tramel 4e pp.60-68Document11 pagesMoral Philosophy, Pojman & Tramel 4e pp.60-68GlyphofLife100% (1)

- 10 2307@3293968Document8 pages10 2307@3293968ekdorkianNo ratings yet

- Seminar 1 - PlatoDocument2 pagesSeminar 1 - PlatomantoniabaenaNo ratings yet

- Justice Is The Advantage of The Stronger: Excerpt From Plato's RepublicDocument6 pagesJustice Is The Advantage of The Stronger: Excerpt From Plato's RepublicPratik Butte PatilNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and The Self in Plato S PhiloDocument15 pagesKnowledge and The Self in Plato S PhiloRodrigo Córdova ANo ratings yet

- Plato The Republic BK - IIDocument29 pagesPlato The Republic BK - IIjayjay25585No ratings yet

- Plato's Republic, by Alain BadiouDocument22 pagesPlato's Republic, by Alain BadiouColumbia University Press100% (1)

- A Response To Glaucon - S Challenge - The Sachs Problem and The AccoDocument28 pagesA Response To Glaucon - S Challenge - The Sachs Problem and The Accoaryangupta0574545No ratings yet

- Rousseau - Discourse and Social Contract (2023)Document61 pagesRousseau - Discourse and Social Contract (2023)parismelanson1902No ratings yet

- Summary The Republic Book2Document7 pagesSummary The Republic Book2Ej LagoNo ratings yet

- On Freedom in SartreDocument5 pagesOn Freedom in Sartreaury abellanaNo ratings yet

- Punishment in Socratic PhilosophyDocument14 pagesPunishment in Socratic Philosophyvince34No ratings yet

- Plato and Common Morality (Julia Annas)Document16 pagesPlato and Common Morality (Julia Annas)Javier Arturo Velázquez GalvánNo ratings yet

- Question Week 1 - Plato - Meaning of LifeDocument5 pagesQuestion Week 1 - Plato - Meaning of LifeCheng ZhongNo ratings yet

- Module 4 - Plato and SocratesDocument7 pagesModule 4 - Plato and SocratesLove KimNo ratings yet

- The Socrates-Question BDocument37 pagesThe Socrates-Question Bwish09No ratings yet

- Ethics Chapter1 PlatoDocument11 pagesEthics Chapter1 PlatodanNo ratings yet

- Socrates Apology ThesisDocument5 pagesSocrates Apology Thesisdarlenetourignysaltlakecity100% (3)

- Introductory LogicDocument129 pagesIntroductory Logicwaskhez100% (1)

- The Self From Various Philosophical PerspectivesDocument9 pagesThe Self From Various Philosophical PerspectivesNiño UretaNo ratings yet

- 1 - The Republic Book IIDocument16 pages1 - The Republic Book IISh SamadyarNo ratings yet

- GEC18Document2 pagesGEC18Avian Henna CatamcoNo ratings yet

- Paper2 OneAll (Plato)Document2 pagesPaper2 OneAll (Plato)Romeo Macali Jr.No ratings yet

- Nietzsche, Callicles and The Will To PowerDocument8 pagesNietzsche, Callicles and The Will To Powerantoniompm5237No ratings yet

- Western Political ThoughtDocument110 pagesWestern Political ThoughtWajahat GhafoorNo ratings yet

- Trust in Plato's Republic: HE Hilosophy of RustDocument2 pagesTrust in Plato's Republic: HE Hilosophy of RusttyapikusNo ratings yet

- The Art of Logical Thinking: Or the Laws of Reasoning (Classic Reprint)From EverandThe Art of Logical Thinking: Or the Laws of Reasoning (Classic Reprint)No ratings yet

- PlatoDocument49 pagesPlatoMika BanzuelaNo ratings yet

- What Socrates Knew: Daniel W. GrahamDocument12 pagesWhat Socrates Knew: Daniel W. GrahamNițceValiNo ratings yet

- Student Version-Discourse On InequalityDocument77 pagesStudent Version-Discourse On InequalityliquifiedmaggotpieNo ratings yet

- Philosophy in The Cypher SystemDocument23 pagesPhilosophy in The Cypher SystemEujiniy CosmichNo ratings yet

- Plato Republic ThesisDocument5 pagesPlato Republic Thesisbrittanyjonescolumbia100% (2)

- Grayling Socrates and The Meaning of LifeDocument6 pagesGrayling Socrates and The Meaning of LifeMichael CheungNo ratings yet

- Platonic JusticeDocument76 pagesPlatonic JusticeBedanga Bhushan SaikiaNo ratings yet

- Minding Gaps in RepublicDocument28 pagesMinding Gaps in RepublicColton McKeeNo ratings yet

- Normative Ethical TheoriesDocument13 pagesNormative Ethical TheoriesMohasin Niloy Ahmed 2121497642No ratings yet

- A DIFFERENT KIND OF PRO, First Assigned TextDocument4 pagesA DIFFERENT KIND OF PRO, First Assigned TextWayland DepidepNo ratings yet

- Final ExamDocument9 pagesFinal ExamDaniel KamauNo ratings yet

- PLATO Rep. 1-3Document3 pagesPLATO Rep. 1-3Pablo SahagunNo ratings yet

- Aristotle Thoery of JusticeDocument1 pageAristotle Thoery of Justicexee shanNo ratings yet

- ExportDocument14 pagesExportmar.suntoesNo ratings yet

- Notes On PlatoDocument3 pagesNotes On PlatoCharmee MacapalaNo ratings yet

- 02 - PlatoDocument13 pages02 - Platoroscoe_lee7No ratings yet

- The Art of Logical Thinking Or The Laws of ReasoningFrom EverandThe Art of Logical Thinking Or The Laws of ReasoningNo ratings yet

- Ricoeur Confronts Levi Staruss On StructuralismDocument18 pagesRicoeur Confronts Levi Staruss On StructuralismMazen El MakkoukNo ratings yet

- Module 3: Sophist ObjectivesDocument5 pagesModule 3: Sophist ObjectivesLove KimNo ratings yet

- Ring of Gyges-WikiDocument1 pageRing of Gyges-Wikiapi-265810916No ratings yet

- Impact of Socrates On Philosophy of Morality 1584912263Document7 pagesImpact of Socrates On Philosophy of Morality 1584912263Tamseel MubarikNo ratings yet

- II. Lecture Notes: Morality and The Happy Life (Plato's Republic, Ch.1)Document12 pagesII. Lecture Notes: Morality and The Happy Life (Plato's Republic, Ch.1)Boram LeeNo ratings yet

- Ethics Intro To Ethics AssignmentDocument3 pagesEthics Intro To Ethics AssignmentAvian Henna CatamcoNo ratings yet

- Plato Ring of Gyges PDFDocument4 pagesPlato Ring of Gyges PDFClaire Iris VillaretNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Aristotle'S de Anima Thomas TaylorDocument27 pagesIntroduction To Aristotle'S de Anima Thomas TaylorJefrey Ternera GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- 02 PlatoDocument59 pages02 Platoaidaraafat426No ratings yet

- We Were Something DontDocument6 pagesWe Were Something DontmrycovcvzalvwkofgnNo ratings yet

- Mech PDFDocument9 pagesMech PDFgurusamyNo ratings yet

- The Complete Book of Hairstyling - NodrmDocument63 pagesThe Complete Book of Hairstyling - Nodrmrvf1No ratings yet

- TR2231 AVEVA Plant CAD Model Requirements Ver4Document29 pagesTR2231 AVEVA Plant CAD Model Requirements Ver4ASIMNo ratings yet

- Elements of Mechanism by Doughtie and James PDFDocument1 pageElements of Mechanism by Doughtie and James PDFChristian M. CalinayaNo ratings yet

- Series & Parallel PumpsDocument48 pagesSeries & Parallel PumpsMoh AmmNo ratings yet

- Reservation List As of June 27Document104 pagesReservation List As of June 27Francis DedumoNo ratings yet

- Broaching MachineDocument8 pagesBroaching MachineJaya RamanNo ratings yet

- Fracture CrurisDocument44 pagesFracture CrurisAnonymous turPUJtErNo ratings yet

- Touchntuff-92-600 PDS Us enDocument2 pagesTouchntuff-92-600 PDS Us enFrank Christian Gomez YauriNo ratings yet

- Application of Digital RadiographyDocument13 pagesApplication of Digital RadiographyFred LeviNo ratings yet

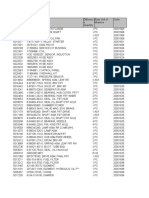

- Platimagen Customer DatabaseDocument4 pagesPlatimagen Customer DatabaseErik OrtizNo ratings yet

- IFU 5902446 Port A-FrameDocument16 pagesIFU 5902446 Port A-FrameBeto AsaberNo ratings yet

- Kantar Worldpanel 5 Key FMCG Trends in Vietnam 2023 ENDocument25 pagesKantar Worldpanel 5 Key FMCG Trends in Vietnam 2023 ENbrianNo ratings yet

- AppendixDocument5 pagesAppendixAsim IqbalNo ratings yet

- 돌프 회로이론 9판 5장 솔루션Document65 pages돌프 회로이론 9판 5장 솔루션냥냥냥No ratings yet

- Wastewater Characteristics: Table 7.1.5 Table 7.1.6Document4 pagesWastewater Characteristics: Table 7.1.5 Table 7.1.6Amin EnviroNo ratings yet

- Final Essay - Global WarmingDocument9 pagesFinal Essay - Global WarmingJarett Lopez100% (1)

- The Real ChristDocument185 pagesThe Real ChristDuncan HeasterNo ratings yet

- Gas Turbine Simulator - VisSimDocument2 pagesGas Turbine Simulator - VisSimAbdelkader TayebiNo ratings yet

- YS VIII Steam ArtbookDocument19 pagesYS VIII Steam ArtbookTuukka MäkinenNo ratings yet

- Brosur Buffet Package TelView 2013Document8 pagesBrosur Buffet Package TelView 2013gearkitNo ratings yet

- "7 Streams of Income For The Average Nigerian": by Oluwatoyin Omotoso ofDocument29 pages"7 Streams of Income For The Average Nigerian": by Oluwatoyin Omotoso ofOliver Dennis100% (1)

- B20B 6X4 AdtDocument297 pagesB20B 6X4 AdtHANNESNo ratings yet

- Mobile SPM & DF 2020.ppt (Compatibility Mode)Document18 pagesMobile SPM & DF 2020.ppt (Compatibility Mode)Sambo BenerNo ratings yet

- Verbos Irregulares y RegularesDocument2 pagesVerbos Irregulares y RegularesFernando MoraNo ratings yet

- WWI 29th Infantry DivisionDocument89 pagesWWI 29th Infantry DivisionCAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

The Ring of Gyges For Gethics

The Ring of Gyges For Gethics

Uploaded by

Lei Anne GacayanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ring of Gyges For Gethics

The Ring of Gyges For Gethics

Uploaded by

Lei Anne GacayanCopyright:

Available Formats

Plato: Why Should I Be Moral?

Gyges’ Ring and Socrates’ Dilemma 455

selfishly will be punished. But take away the notion of a God or a transcendent moral

order that affects us and the Socratic picture breaks down. Self-interest can involve

exploiting others; treating them “unjustly.”

In our second reading, Louis Pojman offers several arguments against ethical

egoism, the doctrine that right actions are those that promote one’s own best in-

terests. He concludes that ethical egoism is unfounded.

VI.55 Why Should I Be Moral? Gyges’ Ring

and Socrates’ Dilemma

Pl ato

Plato (427–347 b.c.) lived in Athens and is the earliest philosopher for whom exten-

sive works still remain today. In a series of dialogues he immortalized his teacher,

Socrates. Perhaps his greatest dialogue is the Republic, from which this present read-

ing is taken. The Republic is a classic treatise on political philosophy, centering on the

concept of justice or moral rightness. In this work, Plato, through his idealization of

Socrates, argues there will only be justice when reason rules and the people are obe-

dient to its commands. This Utopia is only possible in an aristocracy in which the

rulers are philosophers—philosopher-kings. In our selection, Glaucon, who is Plato’s

older brother, asks Socrates whether justice is good in itself or only a necessary evil.

Playing the devil’s advocate, Glaucon puts forth the hypothesis that egotistic power-

seeking in which we have complete freedom to indulge ourselves might be the ideal

state of existence. However, the hypothesis continues, reason quickly shows us that

others might seek to have the same power, which would interfere with our freedom

and cause a state of chaos in which no one was likely to have any of one’s desires

fulfilled. So we compromise and limit our acquisitive instincts. Justice or a system of

morality is simply the result of that compromise. It has no intrinsic value but is better

than chaos but worse than undisturbed power. It is better to compromise and limit

our acquisitive instincts.

To illustrate his point Glaucon tells the story of a shepherd named Gyges who comes

upon a ring, which at his behest makes him invisible. He uses it to escape the external

sanctions of society—its laws and censure—and to serve his greed to the fullest.

Glaucon asks whether it is not plausible to suppose that we all would do likewise?

Then he offers a thought experiment that compares the life of the seemingly just (but

unjust) man who is incredibly successful with the life of the seemingly unjust (but

just) man who is incredibly unsuccessful. Which would we choose?

We enter the dialogue in the second book of the Republic. Socrates has just

shown that the type of egoism advocated by Thrasymachus is contradictory. Socrates

is speaking.

06-Pojman-Part06.indd 455 22/08/16 3:07 PM

456 pa r t s i x : e t h ic s

Study Questions

1. Note the distinction between different kinds of goods: (1) things desirable in themselves,

(2) things not desirable in themselves but instrumental to other goods, and (3) things

both intrinsically and instrumentally good. Which kind of good is justice, according to

Socrates, and why?

2. What is the popular view of justice, according to Glaucon?

3. What is the lesson to be drawn from the story of Gyges’ ring? Do you agree with G laucon’s

conclusion about human nature?

4. What is Glaucon’s point in comparing the completely just-but-seemingly-unjust man with

the completely unjust-but-seemingly-just man? Which would you choose?

gyge s ’ ri ng them as disagreeable; and no one would choose

them for their own sakes, but only for the sake

With these words I was thinking that I had of some reward or result which flows from them?

made an end of the discussion; but the end, in There is, I said, this third class also. But why

truth, proved to be only a beginning. For Glau- do you ask?

con, who is always the most pugnacious of men, Because I want to know in which of the three

was dissatisfied at Thrasymachus’ retirement; he classes you would place justice?

wanted to have the battle out. So he said to me: In the highest class, I replied, among those

Socrates, do you wish really to persuade us, or goods which he who would be happy desires

only to seem to have persuaded us, that to be both for their own sake and for the sake of their

just is always better than to be unjust? results.

I should wish really to persuade you, I replied, Then the many are of another mind; they

if I could. think that justice is to be reckoned in the trou-

Then you certainly have not succeeded. Let me blesome class, among goods which are to be

ask you now:—How would you arrange goods— pursued for the sake of rewards and of reputa-

are there not some which we welcome for their tion, but in themselves are disagreeable and

own sakes, and independently of their conse- rather to be avoided.

quences, as, for example, harmless pleasures and I know, I said, that this is their manner of

enjoyments, which delight us at the time, although thinking, and that this was the thesis which

nothing follows from them? Thrasymachus was maintaining just now, when

I agree in thinking that there is such a class, he censured justice and praised injustice. But I am

I replied. too stupid to be convinced by him.

Is there not also a second class of goods, such I wish, he said, that you would hear me as

as knowledge, sight, health, which are desirable well as him, and then I shall see whether you

not only in themselves, but also for their results? and I agree. For Thrasymachus seems to me,

Certainly, I said. like a snake, to have been charmed by your voice

And would you not recognize a third class, sooner than he ought to have been; but to my

such as gymnastic, and the care of the sick, and mind the nature of justice and injustice have not

the physician’s art; also the various ways of yet been made clear. Setting aside their rewards

money-making—these do us good but we regard and results, I want to know what they are in

Reprinted from The Dialogues of Plato, translated by Benjamin Jowett (Charles Scribner’s, 1889).

06-Pojman-Part06.indd 456 22/08/16 3:07 PM

Plato: Why Should I Be Moral? Gyges’ Ring and Socrates’ Dilemma 457

themselves, and how they inwardly work in the between the two, is tolerated not as a good,

soul. If you please, then, I will revive the argu- but as the lesser evil, and honoured by reason of

ment of Thrasymachus. And first I will speak of the inability of men to do injustice. For no man

the nature and origin of justice according to the who is worthy to be called a man would ever

common view of them. Secondly, I will show that submit to such an agreement if he were able to

all men who practice justice do so against their resist; he would be mad if he did. Such is the re-

will, of necessity, but not as a good. And thirdly, ceived account, Socrates, of the nature and origin

I will argue that there is reason in this view, for of justice.

the life of the unjust is after all better far than Now that those who practice justice do so

the life of the just—if what they say is true, Soc- involuntarily and because they have not the

rates, since I myself am not of their opinion. But power to be unjust will best appear if we imag-

still I acknowledge that I am perplexed when ine something of this kind: having given both to

I hear the voices of Thrasymachus and myriads the just and the unjust power to do what they

of others dinning in my ears; and, on the other will, let us watch and see whither desire will lead

hand, I have never yet heard the superiority of them; then we shall discover in the very act the

justice to injustice maintained by any one in a just and unjust man to be proceeding along the

satisfactory way. I want to hear justice praised in same road, following their interest, which all

respect of itself; then I shall be satisfied, and you natures deem to be their good, and are only di-

are the person from whom I think that I am most verted into the path of justice by the force of

likely to hear this; and therefore I will praise the law. The liberty which we are supposing may be

unjust life to the utmost of my power, and my most completely given to them in the form of

manner of speaking will indicate the manner in such a power as is said to have been possessed

which I desire to hear you too praising justice by Gyges the ancestor of Croesus the Lydian.

and censuring injustice. Will you say whether According to the tradition, Gyges was a shepherd

you approve of my proposal? in the service of the king of Lydia; there was a

Indeed I do; nor can I imagine any theme great storm, and an earthquake made an open-

about which a man of sense would oftener wish ing in the earth at the place where he was feed-

to converse. ing his flock. Amazed at the sight, he descended

I am delighted, he replied, to hear you say so, into the opening, where, among other marvels,

and shall begin by speaking, as I proposed, of he beheld a hollow brazen horse, having doors,

the nature and origin of justice. at which he stooping and looking in saw a dead

They say that to do injustice is, by nature, body of stature, as appeared to him, more than

good; to suffer injustice, evil; but that the evil is human, and having nothing on but a gold ring;

greater than the good. And so when men have this he took from the finger of the dead and re-

both done and suffered injustice and have had ascended. Now the shepherds met together, ac-

experience of both, not being able to avoid the cording to custom, that they might send their

one and obtain the other, they think that they had monthly report about the flocks to the king;

better agree among themselves to have neither; into their assembly he came having the ring on

hence there arise laws and mutual covenants; his finger, and as he was sitting among them he

and that which is ordained by law is termed by chanced to turn the collet of the ring inside his

them lawful and just. This they affirm to be the hand, when instantly he became invisible to the

origin and nature of justice:—it is a mean or rest of the company and they began to speak of

compromise, between the best of all, which is to him as if he were no longer present. He was as-

do injustice and not be punished, and the worst tonished at this, and again touching the ring he

of all, which is to suffer injustice without the power turned the collet outwards and reappeared; he

of retaliation; and justice, being at a middle point made several trials of the ring, and always with

06-Pojman-Part06.indd 457 22/08/16 3:07 PM

458 pa r t s i x : e t h ic s

the same result—when he turned the collet in- their limits, and who, if he fails at any point, is

wards he became invisible, when outwards he able to recover himself. So let the unjust make his

reappeared. Whereupon he contrived to be chosen unjust attempts in the right way, and lie hidden

one of the messengers who were sent to the if he means to be great in his injustice (he who

court; where as soon as he arrived he seduced is found out is nobody): for the highest reach of

the queen, and with her help conspired against injustice is: to be deemed just when you are not.

the king and slew him, and took the kingdom. Therefore I say that in the perfectly unjust man

Suppose now that there were two such magic we must assume the most perfect injustice; there

rings, and the just put on one of them and the is to be no deduction, but we must allow him,

unjust the other; no man can be imagined to be while doing the most unjust acts, to have ac-

of such an iron nature that he would stand fast quired the greatest reputation for justice. If he

in justice. No man would keep his hands off have taken a false step he must be able to recover

what was not his own when he could safely take himself; he must be one who can speak with

what he liked out of the market, or go into effect, if any of his deeds come to light, and who

houses and lie with any one at his pleasure, or can force his way where force is required by his

kill or release from prison whom he would, and courage and strength, and command of money

in all respects be like a God among men. Then and friends. And at his side let us place the just

the actions of the just would be as the actions man in his nobleness and simplicity, wishing, as

of the unjust; they would both come at last to Aeschylus says, to be and not to seem good.

the same point. And this we may truly affirm to There must be no seeming, for if he seem to be

be a great proof that a man is just, not willingly just he will be honoured and rewarded, and

or because he thinks that justice is any good to then we shall not know whether he is just for the

him individually, but of necessity, for wherever sake of justice or for the sake of honours and

any one thinks that he can safely be unjust, there rewards; therefore, let him be clothed in justice

he is unjust. For all men believe in their hearts only, and have no other covering; and he must

that injustice is far more profitable to the indi- be imagined in a state of life the opposite of the

vidual than justice, and he who argues as I have former. Let him be the best of men, and let him

been supposing, will say that they are right. If you be thought the worst; then he will have been

could imagine any one obtaining this power of put to the proof; and we shall see whether he

becoming invisible, and never doing any wrong will be affected by the fear of infamy and its

or touching what was another’s, he would be consequences. And let him continue thus to the

thought by the lookers-on to be a most wretched hour of death; being just and seeming to be

idiot, although they would praise him to one unjust. When both have reached the uttermost

another’s faces, and keep up appearances with one extreme, the one of justice and the other of in-

another from a fear that they too might suffer justice, let judgment be given which of them is

injustice. Enough of this. the happier of the two.

Now, if we are to form a real judgment of the Heavens! my dear Glaucon, I said, how ener-

life of the just and unjust, we must isolate them; getically you polish them up for the decision,

there is no other way; and how is the isolation first one and then the other, as if they were two

to be effected? I answer: Let the unjust man be statues.

entirely unjust, and the just man entirely just; I do my best, he said. And now that we know

nothing is to be taken away from either of what they are like there is no difficulty in tracing

them, and both are to be perfectly furnished for out the sort of life which awaits either of them.

the work of their respective lives. First, let the This I will proceed to describe; but as you may

unjust be like other distinguished masters of craft; think the description a little too coarse, I ask

like the skillful pilot or physician, who knows you to suppose, Socrates, that the words which

intuitively his own powers and keeps within follow are not mine.—Let me put them into the

06-Pojman-Part06.indd 458 22/08/16 3:07 PM

Plato: Why Should I Be Moral? Gyges’ Ring and Socrates’ Dilemma 459

mouths of the eulogists of injustice: they will “By molding in words an image of the soul,

tell you that the just man who is thought unjust so that the one who said that will realize what

will be scourged, racked, bound—will have his he was saying.”

eyes burnt out; and, at last, after suffering every “What kind of image?”

kind of evil, he will be impaled: Then he will “Oh, something like those natures the myths

understand that he ought to seem only, and not tell us were born in ancient times—the Chimaera,

to be, just; the words of Aeschylus may be more Scylla, Cerberus, and others in which many

truly spoken of the unjust than of the just. For different shapes were supposed to have grown

the unjust is pursuing a reality; he does not live into one.”

with a view to appearances—he wants to be “So they tell us,” he said.

really unjust and not to seem only:— “Then mold one figure of a colorful, many-

His mind has a soil deep and fertile.

headed beast with heads of wild and tame

Out of which spring his prudent counsels. a nimals growing in a circle all around it; one

that can change and grow all of them out of

In the first place, he is thought just, and there- itself.”

fore bears rule in the city; he can marry whom “That’s a job for a skilled artist. Still, words

he will, and give in marriage to whom he will; mold easier than wax or clay, so consider it done.”

also he can trade and deal where he likes, and “And another of a lion, and one of a man.

always to his own advantage, because he has no Make the first by far the biggest, the second

misgivings about injustice; and at every contest, second largest.”

whether in public or private, he gets the better “That’s easier, and already done.”

of his antagonists, and gains at their expense, “Now join the three together so that they

and is rich, and out of his gains he can benefit somehow grow.”

his friends, and harm his enemies; moreover, he “All right.”

can offer sacrifices, and dedicate gifts to the gods “Next mold the image of one, the man,

abundantly and magnificently, and can honour around them all, so that to someone who can’t

the gods or any man whom he wants to honour see what’s inside but looks only at the container

in a far better style than the just, and therefore it appears to be a single animal, man.”

he is likely to be dearer than they are to the gods. “I have.”

And thus, Socrates, gods and men are said to “Then shall we inform the gentleman that

unite in making the life of the unjust better when he says it pays for this man to be unjust,

than the life of the just. . . . he’s saying that it profits him to feast his multi-

[We pick up the discussion in Book 9.] farious beast and his lion and make them grow

strong, but to starve and enfeeble the man in

him so that he gets dragged wherever the animals

b o ok 9 lead him, and instead of making them friends

and used to each other, to let them bite and fight

“Now that we’ve gotten this far,” I said, “let’s and eat each other?”

go back to that statement made at the beginning, “That’s just what he’s saying by praising

which brought us here: that it pays for a man to injustice.”

be perfectly unjust if he appears to be just. Isn’t “The one who says justice pays, however,

that what someone said?” would be saying that he should practice and say

“Yes.” whatever will give the most mastery to his inner

“Then since we’ve agreed what power justice man, who should care for the many-headed

and injustice each have, let’s have a discussion beast like a farmer, raising and domesticating its

with him.” tame heads and preventing the wild ones from

“How?” growing, making the lion’s nature his partner

06-Pojman-Part06.indd 459 22/08/16 3:07 PM

460 pa r t s i x : e t h ic s

and ally, and so raise them both to be friends to inside, but if not, it should be imposed on him

each other and to him.” from without so that we may all be friends and

“That’s exactly what he means by praising as nearly alike as possible, all steered by the same

justice.” thing.”

“So in every way the commender of justice “Yes, and we’re right,” he said.

is telling the truth, the other a lie. Whether we “Law, the ally of everyone in the city, clearly

examine pleasure, reputation, or profit, we find intends the same thing, as does the rule of chil-

that the man who praises justice speaks truly, dren, which forbids us to let them be free until

the one who disparages it disparages sickly and we’ve instituted a regime in them as in a city. We

knows nothing of what he disparages.” serve their best part with a similar part in us,

“I don’t think he does at all.” install a like guardian and ruler in them, and

“Then let’s gently persuade him—his error only then set them free.”

wasn’t intended—by asking him a question: “Clearly.”

‘Shouldn’t we say that the traditions of the “Then how, by what argument, Glaucon, can

beautiful and the ugly have come about like this: we say that it pays for a man to be unjust or

Beautiful things are those that make our bestial self-indulgent or to do something shameful to

parts subservient to the human—or rather, per- get more money or power if by doing so he

haps, to the divine—part of our nature, while makes himself worse?”

ugly ones are those that enslave the tame to the “We can’t,” he said.

wild?’ Won’t he agree?” “And how can it pay to commit injustice

“If he takes my advice.” without getting caught and being punished?

“On this argument then, can it pay for a man Doesn’t getting away with it make a man even

to take money unjustly if that means making his worse? Whereas if a man gets caught and pun-

best part a slave to the worst? If it wouldn’t ished, his beastlike part is taken in and tamed,

profit a man to sell his son or his daughter into his tame part is set free, and his whole soul ac-

slavery—to wild and evil men at that—even if he quires justice and temperance and knowledge.

got a fortune for it, then if he has no pity on Therefore his soul recovers its best nature and

himself and enslaves the most godlike thing in attains a state more honorable than the state the

him to the most godless and polluted, isn’t he a body attains when it acquires health and strength

wretch who gets bribed for gold into a destruc- and beauty, by as much as the soul is more hon-

tion more horrible than Euriphyle’s, who sold orable than the body.”

her husband’s life for a necklace?” “Absolutely.”

“Much more horrible,” said Glaucon. “Then won’t a sensible man spend his life di-

“. . . everyone is better off being ruled by the recting all his efforts to this end?”

godlike and intelligent; preferably if he has it

For Further Reflection

1. Which would you choose to be, Glaucon’s good but suffering person or his bad but

successful person? Is there a third alternative?

2. Socrates’ answer to Glaucon and Adeimantus is that, despite appearances, we should

choose the life of the “unsuccessful” just person because it is to our advantage to be moral.

Socrates’ answer depends on a notion of mental health. He contends that immorality corrupts

the inner person, so that one is happy or unhappy in exact proportion to one’s moral integrity.

Is this a plausible reply?

3. Is the good always good for you?

06-Pojman-Part06.indd 460 22/08/16 3:07 PM

You might also like

- The Republic - AbridgedDocument18 pagesThe Republic - AbridgedDaniel BalurisNo ratings yet

- Science Week Proposal 2 JuneDocument26 pagesScience Week Proposal 2 Junecsanjeevan100% (1)

- I Ching TesseractDocument14 pagesI Ching Tesseractthoth11100% (1)

- NTPCDocument158 pagesNTPCAnand GuptaNo ratings yet

- 07 Egoism PDFDocument6 pages07 Egoism PDFDMCañonNo ratings yet

- Aristotle On The Value of Friendship As A Motivation For MoralityDocument20 pagesAristotle On The Value of Friendship As A Motivation For Moralitya280872No ratings yet

- Gyges ADocument9 pagesGyges AHamza Saif RanjhaNo ratings yet

- Ethical EgoismDocument3 pagesEthical EgoismstacyshackNo ratings yet

- Moral Philosophy, Pojman & Tramel 4e pp.60-68Document11 pagesMoral Philosophy, Pojman & Tramel 4e pp.60-68GlyphofLife100% (1)

- 10 2307@3293968Document8 pages10 2307@3293968ekdorkianNo ratings yet

- Seminar 1 - PlatoDocument2 pagesSeminar 1 - PlatomantoniabaenaNo ratings yet

- Justice Is The Advantage of The Stronger: Excerpt From Plato's RepublicDocument6 pagesJustice Is The Advantage of The Stronger: Excerpt From Plato's RepublicPratik Butte PatilNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and The Self in Plato S PhiloDocument15 pagesKnowledge and The Self in Plato S PhiloRodrigo Córdova ANo ratings yet

- Plato The Republic BK - IIDocument29 pagesPlato The Republic BK - IIjayjay25585No ratings yet

- Plato's Republic, by Alain BadiouDocument22 pagesPlato's Republic, by Alain BadiouColumbia University Press100% (1)

- A Response To Glaucon - S Challenge - The Sachs Problem and The AccoDocument28 pagesA Response To Glaucon - S Challenge - The Sachs Problem and The Accoaryangupta0574545No ratings yet

- Rousseau - Discourse and Social Contract (2023)Document61 pagesRousseau - Discourse and Social Contract (2023)parismelanson1902No ratings yet

- Summary The Republic Book2Document7 pagesSummary The Republic Book2Ej LagoNo ratings yet

- On Freedom in SartreDocument5 pagesOn Freedom in Sartreaury abellanaNo ratings yet

- Punishment in Socratic PhilosophyDocument14 pagesPunishment in Socratic Philosophyvince34No ratings yet

- Plato and Common Morality (Julia Annas)Document16 pagesPlato and Common Morality (Julia Annas)Javier Arturo Velázquez GalvánNo ratings yet

- Question Week 1 - Plato - Meaning of LifeDocument5 pagesQuestion Week 1 - Plato - Meaning of LifeCheng ZhongNo ratings yet

- Module 4 - Plato and SocratesDocument7 pagesModule 4 - Plato and SocratesLove KimNo ratings yet

- The Socrates-Question BDocument37 pagesThe Socrates-Question Bwish09No ratings yet

- Ethics Chapter1 PlatoDocument11 pagesEthics Chapter1 PlatodanNo ratings yet

- Socrates Apology ThesisDocument5 pagesSocrates Apology Thesisdarlenetourignysaltlakecity100% (3)

- Introductory LogicDocument129 pagesIntroductory Logicwaskhez100% (1)

- The Self From Various Philosophical PerspectivesDocument9 pagesThe Self From Various Philosophical PerspectivesNiño UretaNo ratings yet

- 1 - The Republic Book IIDocument16 pages1 - The Republic Book IISh SamadyarNo ratings yet

- GEC18Document2 pagesGEC18Avian Henna CatamcoNo ratings yet

- Paper2 OneAll (Plato)Document2 pagesPaper2 OneAll (Plato)Romeo Macali Jr.No ratings yet

- Nietzsche, Callicles and The Will To PowerDocument8 pagesNietzsche, Callicles and The Will To Powerantoniompm5237No ratings yet

- Western Political ThoughtDocument110 pagesWestern Political ThoughtWajahat GhafoorNo ratings yet

- Trust in Plato's Republic: HE Hilosophy of RustDocument2 pagesTrust in Plato's Republic: HE Hilosophy of RusttyapikusNo ratings yet

- The Art of Logical Thinking: Or the Laws of Reasoning (Classic Reprint)From EverandThe Art of Logical Thinking: Or the Laws of Reasoning (Classic Reprint)No ratings yet

- PlatoDocument49 pagesPlatoMika BanzuelaNo ratings yet

- What Socrates Knew: Daniel W. GrahamDocument12 pagesWhat Socrates Knew: Daniel W. GrahamNițceValiNo ratings yet

- Student Version-Discourse On InequalityDocument77 pagesStudent Version-Discourse On InequalityliquifiedmaggotpieNo ratings yet

- Philosophy in The Cypher SystemDocument23 pagesPhilosophy in The Cypher SystemEujiniy CosmichNo ratings yet

- Plato Republic ThesisDocument5 pagesPlato Republic Thesisbrittanyjonescolumbia100% (2)

- Grayling Socrates and The Meaning of LifeDocument6 pagesGrayling Socrates and The Meaning of LifeMichael CheungNo ratings yet

- Platonic JusticeDocument76 pagesPlatonic JusticeBedanga Bhushan SaikiaNo ratings yet

- Minding Gaps in RepublicDocument28 pagesMinding Gaps in RepublicColton McKeeNo ratings yet

- Normative Ethical TheoriesDocument13 pagesNormative Ethical TheoriesMohasin Niloy Ahmed 2121497642No ratings yet

- A DIFFERENT KIND OF PRO, First Assigned TextDocument4 pagesA DIFFERENT KIND OF PRO, First Assigned TextWayland DepidepNo ratings yet

- Final ExamDocument9 pagesFinal ExamDaniel KamauNo ratings yet

- PLATO Rep. 1-3Document3 pagesPLATO Rep. 1-3Pablo SahagunNo ratings yet

- Aristotle Thoery of JusticeDocument1 pageAristotle Thoery of Justicexee shanNo ratings yet

- ExportDocument14 pagesExportmar.suntoesNo ratings yet

- Notes On PlatoDocument3 pagesNotes On PlatoCharmee MacapalaNo ratings yet

- 02 - PlatoDocument13 pages02 - Platoroscoe_lee7No ratings yet

- The Art of Logical Thinking Or The Laws of ReasoningFrom EverandThe Art of Logical Thinking Or The Laws of ReasoningNo ratings yet

- Ricoeur Confronts Levi Staruss On StructuralismDocument18 pagesRicoeur Confronts Levi Staruss On StructuralismMazen El MakkoukNo ratings yet

- Module 3: Sophist ObjectivesDocument5 pagesModule 3: Sophist ObjectivesLove KimNo ratings yet

- Ring of Gyges-WikiDocument1 pageRing of Gyges-Wikiapi-265810916No ratings yet

- Impact of Socrates On Philosophy of Morality 1584912263Document7 pagesImpact of Socrates On Philosophy of Morality 1584912263Tamseel MubarikNo ratings yet

- II. Lecture Notes: Morality and The Happy Life (Plato's Republic, Ch.1)Document12 pagesII. Lecture Notes: Morality and The Happy Life (Plato's Republic, Ch.1)Boram LeeNo ratings yet

- Ethics Intro To Ethics AssignmentDocument3 pagesEthics Intro To Ethics AssignmentAvian Henna CatamcoNo ratings yet

- Plato Ring of Gyges PDFDocument4 pagesPlato Ring of Gyges PDFClaire Iris VillaretNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Aristotle'S de Anima Thomas TaylorDocument27 pagesIntroduction To Aristotle'S de Anima Thomas TaylorJefrey Ternera GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- 02 PlatoDocument59 pages02 Platoaidaraafat426No ratings yet

- We Were Something DontDocument6 pagesWe Were Something DontmrycovcvzalvwkofgnNo ratings yet

- Mech PDFDocument9 pagesMech PDFgurusamyNo ratings yet

- The Complete Book of Hairstyling - NodrmDocument63 pagesThe Complete Book of Hairstyling - Nodrmrvf1No ratings yet

- TR2231 AVEVA Plant CAD Model Requirements Ver4Document29 pagesTR2231 AVEVA Plant CAD Model Requirements Ver4ASIMNo ratings yet

- Elements of Mechanism by Doughtie and James PDFDocument1 pageElements of Mechanism by Doughtie and James PDFChristian M. CalinayaNo ratings yet

- Series & Parallel PumpsDocument48 pagesSeries & Parallel PumpsMoh AmmNo ratings yet

- Reservation List As of June 27Document104 pagesReservation List As of June 27Francis DedumoNo ratings yet

- Broaching MachineDocument8 pagesBroaching MachineJaya RamanNo ratings yet

- Fracture CrurisDocument44 pagesFracture CrurisAnonymous turPUJtErNo ratings yet

- Touchntuff-92-600 PDS Us enDocument2 pagesTouchntuff-92-600 PDS Us enFrank Christian Gomez YauriNo ratings yet

- Application of Digital RadiographyDocument13 pagesApplication of Digital RadiographyFred LeviNo ratings yet

- Platimagen Customer DatabaseDocument4 pagesPlatimagen Customer DatabaseErik OrtizNo ratings yet

- IFU 5902446 Port A-FrameDocument16 pagesIFU 5902446 Port A-FrameBeto AsaberNo ratings yet

- Kantar Worldpanel 5 Key FMCG Trends in Vietnam 2023 ENDocument25 pagesKantar Worldpanel 5 Key FMCG Trends in Vietnam 2023 ENbrianNo ratings yet

- AppendixDocument5 pagesAppendixAsim IqbalNo ratings yet

- 돌프 회로이론 9판 5장 솔루션Document65 pages돌프 회로이론 9판 5장 솔루션냥냥냥No ratings yet

- Wastewater Characteristics: Table 7.1.5 Table 7.1.6Document4 pagesWastewater Characteristics: Table 7.1.5 Table 7.1.6Amin EnviroNo ratings yet

- Final Essay - Global WarmingDocument9 pagesFinal Essay - Global WarmingJarett Lopez100% (1)

- The Real ChristDocument185 pagesThe Real ChristDuncan HeasterNo ratings yet

- Gas Turbine Simulator - VisSimDocument2 pagesGas Turbine Simulator - VisSimAbdelkader TayebiNo ratings yet

- YS VIII Steam ArtbookDocument19 pagesYS VIII Steam ArtbookTuukka MäkinenNo ratings yet

- Brosur Buffet Package TelView 2013Document8 pagesBrosur Buffet Package TelView 2013gearkitNo ratings yet

- "7 Streams of Income For The Average Nigerian": by Oluwatoyin Omotoso ofDocument29 pages"7 Streams of Income For The Average Nigerian": by Oluwatoyin Omotoso ofOliver Dennis100% (1)

- B20B 6X4 AdtDocument297 pagesB20B 6X4 AdtHANNESNo ratings yet

- Mobile SPM & DF 2020.ppt (Compatibility Mode)Document18 pagesMobile SPM & DF 2020.ppt (Compatibility Mode)Sambo BenerNo ratings yet

- Verbos Irregulares y RegularesDocument2 pagesVerbos Irregulares y RegularesFernando MoraNo ratings yet

- WWI 29th Infantry DivisionDocument89 pagesWWI 29th Infantry DivisionCAP History LibraryNo ratings yet