Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Caste 7

Caste 7

Uploaded by

Soma Roy0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesThe occupation of manual scavenging in India is rooted in the Hindu caste system, with manual scavengers belonging to the lowest caste of "untouchables" who perform the most polluting tasks. Manual scavenging involves manually cleaning, carrying, and disposing of human excreta. Though the practice has been outlawed, the social stigma and norms upholding the caste system have rendered anti-scavenging laws ineffective. Scholars trace the origins of manual scavenging to the post-Aryan period, with the enslaved Dravidians assigned the lowest tasks, a practice that was later institutionalized under Mughal rule and received official sanction under British colonial administration.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe occupation of manual scavenging in India is rooted in the Hindu caste system, with manual scavengers belonging to the lowest caste of "untouchables" who perform the most polluting tasks. Manual scavenging involves manually cleaning, carrying, and disposing of human excreta. Though the practice has been outlawed, the social stigma and norms upholding the caste system have rendered anti-scavenging laws ineffective. Scholars trace the origins of manual scavenging to the post-Aryan period, with the enslaved Dravidians assigned the lowest tasks, a practice that was later institutionalized under Mughal rule and received official sanction under British colonial administration.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesCaste 7

Caste 7

Uploaded by

Soma RoyThe occupation of manual scavenging in India is rooted in the Hindu caste system, with manual scavengers belonging to the lowest caste of "untouchables" who perform the most polluting tasks. Manual scavenging involves manually cleaning, carrying, and disposing of human excreta. Though the practice has been outlawed, the social stigma and norms upholding the caste system have rendered anti-scavenging laws ineffective. Scholars trace the origins of manual scavenging to the post-Aryan period, with the enslaved Dravidians assigned the lowest tasks, a practice that was later institutionalized under Mughal rule and received official sanction under British colonial administration.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 3

Of all forms of slavery that human civilization has devised, nothing is more degrading, despicable and inhuman than

the practice of manual scavenging. It

is a forced labor imposed upon a group of people who are doomed to carry

this occupation generation after generation. Their identity and status in society is

linked to the occupation which becomes a cause for exclusion in taking up any

other work. Due to the very nature of the task, they perform, their bodies, nay even

their sight, is considered a source of pollution. They are therefore untouchable and

unapproachable. They are also decreed to shun any social contact with people of

other social groups and are physically segregated and settled in separate colonies

at a fair distance from the main village and urban residential settlement. There are

an elaborate set of social norms and restrictions which are imposed on them. They

are permanently subordinated to the other social groups and have to abide by some

customary social norms which are rigorously enforced by all forms of social violence

and deprivations (Carlsen, 2016; Human Rights Watch, 2014). The enduring

nature of this slavery lies in the collective social force of higher castes which

sustains it and renders laws enacted for the abolition of manual scavenging and

policies made for rehabilitation of scavengers ineffective.

Manual scavenging means manually cleaning, (using brooms and tin plates)

carrying, (in baskets over head to designated sites) disposing of or otherwise

handling in any manner, human excreta in an insanitary latrine or in an open

drain or a pit into which human excreta from unsanitary latrines is disposed

of, or on a railway track or in other spaces or premises before the excreta fully

decomposes.

(Hake, 2015)

Manual scavengers are those who carry out this task. Manual scavengers also

carry out other unsanitary tasks, which include disposing of animal carcasses,

cleaning blood and placenta during child birth, removing clothes and utensils of

the deceased from cremation grounds, cremating unclaimed corpses, cleaning

drains and septic tanks, disposing of non-excretal waste from households, performing

autopsies in hospitals, etc. (Ramaswamy, 2005

The occupation of manual scavenging in India is rooted in the caste-based Hindu

social order, which governs the social, economic and cultural life of people. This

order follows the Varna system, which divides the society into four social groups,

hierarchically ranked in terms of status defined by their respective occupations.

Brahmins are at the top and Sharecare at the bottom. There is a fifth social

formation consisting of those who perform polluting tasks and are therefore considered

untouchables. Manual scavengers are included in this fifth social formation,

and they are placed at the bottom of it. There are stringent norms of social

interaction among these groups based on the premises of pollution and purity.

This linkage between social status and occupation is hereditary and implies its

immutability, which is not amenable to alteration through efforts of an individual

member/members in a group or external force.

Pathak (2015) traces the origin of manual scavenging to a pre-Aryan period,

although the Harappan civilization had an extensive network of underground

drainage and sewerage. It seems that the origin of manual scavenging in India

lies in the conquest of the Aryan people over the Dravidians who were enslaved.

The latter were assimilated into the Hindu Society, but at the bottom of the social

order. Vedic and Post-Vedic period sacred literature, such as Narada Samhita,

Vajasne Samhita, Chandogya Upanishad and Aitarey Brahmin, also confirm the

assignment of work relating to disposal of human excreta to this group known

as Chandalas, Dassin Paulkus who were viewed as degraded persons. The

Dharmashastrasideclared Candelaria’s the illegitimate progeny of a Brahmin

women and a Hardiman. As per Manu, these people were made to live outside

the village and were prohibited from entering villages and towns during the day

time, but were allowed to come to the towns during night hours for cleaning toilets

and removing night soil. Mauryan and Gupta Period also contain references

to the existence of such a group. The practice was further institutionalized during

the Mughal period due to the observance of Purdah (veil) by women among Muslim households and in particular from

the ruling class that secluded Muslim women within the four walls of the house. They were prohibited from going out

for defecation. Bucket privies were designed for their use in the household, which were required to be cleaned and

scavengers were made to do this task. Some of the

manual scavengers accepted Islam, attracted to its egalitarian approach, and were

called Halakhos. Akbar reportedly called them by a less pejorative nomenclature

of ‘Mehta’s’ (Pathak, 2015). Some of the existing scavengers are descendants of

other castes including of Kshatriyas (Nagar 1980 cited in Pathak, 2015).

Shinoda (2002) finds the practice of manual scavenging originating at a later

Mughal period. He traces its origin to urbanization that resulted in the construction

of dry latrine. He also refers to the construction of a public toilet by Emperor

Jahangir in Alwar in AD 1556. The number of such dry latrines were small but

increased enormously during the British period with an increase in urban population,

the establishment of colonies for segments of the ruling class, the cantonment

for army personnel, an increase in Government offices, etc. where they

were attached to the residential buildings. This pattern was later adopted by other

urban dwellers. As the demand for manual scavenging increased, people who

were engaged in sweeping work also took to it as an additional source of income.

The increased demand also resulted in migration to certain parts of the country

where there were no indigenous scavengers. Gradually, sweeping and scavenging

became an exclusive occupation of a section of the population (Shinoda, 2002). D’

Rosario (2016) shares similar view and attributes the origin of manual scavenging

to urbanization and mass production of garbage requiring its disposal. Another

scholar also views the emergence of manual scavenging as an urban phenomenon,

as, due to practice of open defecation in rural areas, there was no need for manual

scavenging (Chaplin, 2002). D’Souza also argues that the process of urbanization

and the state action played a significant role in establishing members of a Dalit

caste as manual scavengers in urban areas (D’Souza, 2016). The British colonial

administration gave it an official sanction by creating the posts of scavengers in

municipalities, Government offices, railways and industries, and reserved these

jobs for members of a particular caste (Hake, 2015). Thus, the practice became

closely associated with a caste (D’ Rosario, 2016).

Manual scavenging is not a uniquely Indian phenomenon. Even in Europe,

manual scavenging started with the construction of public toilets, but ended with

the invention of water closet toilets in 1596 and the flush type of toilets in 1870

(Hake, 2015). Before the invention of the water toilet and piped water supply,

night soil was collected from the privy vaults in cities by persons during the night

and taken to farming areas. Farmers who came to cities for selling their ago

produce took away the night soil as fertilizer (Christopher 1980 cited in Pathak,

2015). However, in Europe, it was not associated with a particular social group. It

was not a caste phenomenon. Scavenging also existed in Arabia before the emergence

of Islam, but there too without its association with the concept of pollution

and hereditary transfer of the occupation to a particular section of society (Pathak,

2015).

You might also like

- 1E7 Force Polygon Experiment 2021Document1 page1E7 Force Polygon Experiment 2021Ratala GepNo ratings yet

- Thumb Rules For Civil Engineers PDFDocument4 pagesThumb Rules For Civil Engineers PDFA KNo ratings yet

- Optitech's CaseDocument4 pagesOptitech's CaseSamuel EncarnaciónNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document16 pagesChapter 1ANJALI NAINNo ratings yet

- History of Manual ScavengersDocument2 pagesHistory of Manual ScavengersSiddharth SinghNo ratings yet

- Manual ScavengingDocument8 pagesManual ScavengingV. Krishna ThejaNo ratings yet

- Political LeadershipDocument12 pagesPolitical LeadershipSandie Daniel GabalunosNo ratings yet

- Globalstudies 48 KhatriDocument24 pagesGlobalstudies 48 KhatriNemesha PanwarNo ratings yet

- Proposal For Research On MAnual Scaveging in MumbaiDocument8 pagesProposal For Research On MAnual Scaveging in MumbaiManthanManishBachaniNo ratings yet

- Socio-Book ReviewDocument14 pagesSocio-Book ReviewAdishree KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Present Dalit (Scavengers) Situation in India: by Dr. Bindeshwar PathakDocument11 pagesPresent Dalit (Scavengers) Situation in India: by Dr. Bindeshwar PathakindiamaheshNo ratings yet

- (Routledge International Handbooks) Steven Vertovec-Routledge International Handbook of Diversity Studies-Routledge (2014)Document9 pages(Routledge International Handbooks) Steven Vertovec-Routledge International Handbook of Diversity Studies-Routledge (2014)P ArunNo ratings yet

- The Prohibition of Employment As Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013: A ReviewDocument9 pagesThe Prohibition of Employment As Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013: A ReviewNamrathaNo ratings yet

- Dalit MigrationDocument12 pagesDalit Migrationdrbhoopal100% (1)

- 23006438Document24 pages23006438Navedita sahuNo ratings yet

- International Covenants, Protocols and InstrumentsDocument12 pagesInternational Covenants, Protocols and InstrumentsRashmiPandeyNo ratings yet

- Lina Carranza & Diego Vargas: National Univertisty of ColombiaDocument12 pagesLina Carranza & Diego Vargas: National Univertisty of ColombiaDiego VargasNo ratings yet

- Imperial Afterlives Citizenship and RaciDocument24 pagesImperial Afterlives Citizenship and Racianamica.sharmaNo ratings yet

- Manual Scavenging: A Case of Denied RightsDocument23 pagesManual Scavenging: A Case of Denied RightsMohd Imran IdrisiNo ratings yet

- Women's Movement Notes/assignmentDocument19 pagesWomen's Movement Notes/assignmentRoly Kumari Singh100% (1)

- Samaj 3886 The Land of The Vaish Caste Structure and Ideology in MauritiusDocument18 pagesSamaj 3886 The Land of The Vaish Caste Structure and Ideology in Mauritiusrainbowmaker3000No ratings yet

- Spaces of Recognition Puja and Power in Contemporary Calcutta Anjan GhoshDocument12 pagesSpaces of Recognition Puja and Power in Contemporary Calcutta Anjan GhoshSwastee RanjanNo ratings yet

- Christopher JAfferlot, CasteDocument24 pagesChristopher JAfferlot, Casteneharana130613No ratings yet

- Lecture 5: Social Change in IndiaDocument7 pagesLecture 5: Social Change in IndiaAmit SinghNo ratings yet

- Redressing The Stigma PDFDocument15 pagesRedressing The Stigma PDFKaRan K KHetani100% (1)

- Unit 3Document11 pagesUnit 3divyagupta8969No ratings yet

- Caste System in IndiaDocument23 pagesCaste System in Indiapvvrr0% (1)

- Efforts Towards Uniform Civil Code-An Historical AccountDocument13 pagesEfforts Towards Uniform Civil Code-An Historical Accountmuca11No ratings yet

- 05 Chapter 1Document13 pages05 Chapter 1vastavi.ghaiNo ratings yet

- VVI Kudmi PaperDocument4 pagesVVI Kudmi PaperiqacjrcgwNo ratings yet

- Chanakya National Law UniversityDocument22 pagesChanakya National Law UniversityRagita NigamNo ratings yet

- 459.fullhuman Rights Movements in IndiaDocument21 pages459.fullhuman Rights Movements in Indiaravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Mnual ScavengersDocument23 pagesMnual ScavengersSainyam BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Casting The Sweepers Local Politics of SDocument34 pagesCasting The Sweepers Local Politics of SVenkat வெங்கட்No ratings yet

- Meerav Paper EzhavasDocument14 pagesMeerav Paper EzhavasShabeeb MuhammedNo ratings yet

- Castesystem AcademiafinalDocument57 pagesCastesystem Academiafinalhrishikesh arvikarNo ratings yet

- Social MovementsDocument18 pagesSocial MovementsJananee RajagopalanNo ratings yet

- 20 Ajitesh BandopadhyayDocument27 pages20 Ajitesh BandopadhyayDebashish RoyNo ratings yet

- Article 17: Manual Scavenging and Abolition of UntouchabilityDocument3 pagesArticle 17: Manual Scavenging and Abolition of UntouchabilityPalak RawatNo ratings yet

- Caste System in IndiaDocument27 pagesCaste System in IndiaRanjith RanjuNo ratings yet

- Caste MobilityDocument6 pagesCaste MobilitySubhojit Das0% (1)

- Garlanding The Sanitation Workers: Glorification of Labor, Caste and Indian PsycheDocument7 pagesGarlanding The Sanitation Workers: Glorification of Labor, Caste and Indian PsycheAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Social Exclusion in Modern Urban Space. 2022Document12 pagesSocial Exclusion in Modern Urban Space. 2022Ananda BritoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 3.7.228.102 On Fri, 14 Jan 2022 21:07:24 UTCDocument12 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 3.7.228.102 On Fri, 14 Jan 2022 21:07:24 UTCAliveNo ratings yet

- Aisha Mughal PaperDocument24 pagesAisha Mughal PaperJarri HaiderNo ratings yet

- Chapter # 1: Utmost Happiness, Roy Gives A Critical View of The Dilemma of Deviant Gender andDocument10 pagesChapter # 1: Utmost Happiness, Roy Gives A Critical View of The Dilemma of Deviant Gender andIkramNo ratings yet

- The Persistence of Caste Indias Hidden Apartheid and The KhairlanjiDocument178 pagesThe Persistence of Caste Indias Hidden Apartheid and The KhairlanjiHarshwardhan G1No ratings yet

- Carcass Boycot Movement in NepalDocument5 pagesCarcass Boycot Movement in NepalSuraj DhakalNo ratings yet

- The State and Subaltern Assertion in The Diaspora: Towards A Pan-South Asian Identity? by Crispin BatesDocument16 pagesThe State and Subaltern Assertion in The Diaspora: Towards A Pan-South Asian Identity? by Crispin BatesCrispin BatesNo ratings yet

- Modernity and Social ChangeDocument13 pagesModernity and Social ChangeShaantanupurab ShaantanupurabNo ratings yet

- Caste and Varna SystemDocument92 pagesCaste and Varna SystemVictoria777No ratings yet

- Technology and Culture Among The Iron Workers of Bihar During The 17th and 18th CenturiesDocument36 pagesTechnology and Culture Among The Iron Workers of Bihar During The 17th and 18th CenturiesNishtha SinhaNo ratings yet

- Transformasi Sosial-Budaya Masyarakat Indonesia Nurdien H. KistantoDocument10 pagesTransformasi Sosial-Budaya Masyarakat Indonesia Nurdien H. KistantoErika Dianty PutriNo ratings yet

- Panchayat RajDocument33 pagesPanchayat RajSurabhi Sadavat100% (1)

- Tribes As Indigenous People of India Virginius Xaxa The IdeaDocument14 pagesTribes As Indigenous People of India Virginius Xaxa The IdeaSaurabh Suman100% (1)

- 81 From Stigma To Self-Assertion: Paraiyars and The Symbolism of TheDocument25 pages81 From Stigma To Self-Assertion: Paraiyars and The Symbolism of Theravibunga4489No ratings yet

- Who Is A Dalit?: Has Become A Political Identity, Similar To The Way African Americans in The United StatesDocument11 pagesWho Is A Dalit?: Has Become A Political Identity, Similar To The Way African Americans in The United Statesyashasvi mujaldeNo ratings yet

- Nagamandala TheoryDocument9 pagesNagamandala TheoryKarnan ThilakNo ratings yet

- Social Change of The Kurdmi-Mahatos in West Bengal: A Sociological StudyDocument4 pagesSocial Change of The Kurdmi-Mahatos in West Bengal: A Sociological StudyJoheb IslamNo ratings yet

- Indigenist Mobilization: Confronting Electoral Communism and Precarious Livelihoods in Post-Reform KeralaFrom EverandIndigenist Mobilization: Confronting Electoral Communism and Precarious Livelihoods in Post-Reform KeralaNo ratings yet

- Lineages of Political Society: Studies in Postcolonial DemocracyFrom EverandLineages of Political Society: Studies in Postcolonial DemocracyNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan Group 1Document10 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan Group 1Ray Allen FabroNo ratings yet

- Cae Listening Test TipsDocument12 pagesCae Listening Test TipsUREÑA SALAS GUADALUPE ABIGAILNo ratings yet

- Levels of AmputationDocument3 pagesLevels of AmputationPratyaksha TiwariNo ratings yet

- Examen de NES Inglés B - APROBADODocument12 pagesExamen de NES Inglés B - APROBADOJuanMa DiazNo ratings yet

- Science Q 3 3wk 5 - 3Document3 pagesScience Q 3 3wk 5 - 3Junior FelipzNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2. The Tourist Market and SegmentationDocument13 pagesLesson 2. The Tourist Market and SegmentationDonna BanuagNo ratings yet

- TS4F01 2 EN Col08Document13 pagesTS4F01 2 EN Col08Kushagra purohitNo ratings yet

- Caterpillar: Service ReportDocument1 pageCaterpillar: Service ReportUGINo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Competence Assessment Updated August 2019Document13 pagesGuidelines For Competence Assessment Updated August 2019Danni MoniqueNo ratings yet

- Thermal Cooling Fan ControllerDocument2 pagesThermal Cooling Fan ControllerPabloReyesNo ratings yet

- FTII Acting Entance EXAM Notes - JET 2019Document61 pagesFTII Acting Entance EXAM Notes - JET 2019Vipul ShankarNo ratings yet

- Ronald J. Adamson 1Document2 pagesRonald J. Adamson 1Dan BaumanNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Hiv AidsDocument3 pagesSyllabus Hiv Aidsniketut alit arminiNo ratings yet

- QAHO1002227 PNC 4th ClsDocument2 pagesQAHO1002227 PNC 4th ClsdevNo ratings yet

- Case study-Connaught-PlaceDocument31 pagesCase study-Connaught-PlaceSwetha Ashok100% (2)

- Subject ChemistryDocument13 pagesSubject ChemistryNikita JakharNo ratings yet

- Discussion Assignment Unit 1 EDUC 5240-01Document5 pagesDiscussion Assignment Unit 1 EDUC 5240-01Javier ToyNo ratings yet

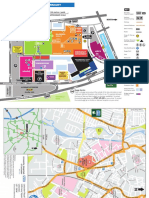

- Leicester Royal Infirmary: M1 M69 Football Stadium KEYDocument2 pagesLeicester Royal Infirmary: M1 M69 Football Stadium KEYpdhoppyNo ratings yet

- Clamp-On Ground Resistance Testing: Fall 2008 NETA WORLDDocument4 pagesClamp-On Ground Resistance Testing: Fall 2008 NETA WORLDAnonymous utxGVB5VyNo ratings yet

- CNG Refuelling - English Final 100504Document8 pagesCNG Refuelling - English Final 100504Worldwide Equipment SolutionsNo ratings yet

- SLG700 34-SL-03-03Document41 pagesSLG700 34-SL-03-03RADAMANTHIS9No ratings yet

- Screenshot 2020-12-24 at 11.13.39Document35 pagesScreenshot 2020-12-24 at 11.13.39Finca NurizzatiNo ratings yet

- Mounthly PT. EBS - KPI MAINTENANCE UNIT JANUARI 2019Document210 pagesMounthly PT. EBS - KPI MAINTENANCE UNIT JANUARI 2019albert svensenNo ratings yet

- Robotic Process Automation StudyDocument48 pagesRobotic Process Automation StudyAkmanar BaktanNo ratings yet

- Computer Applications in ChemistryDocument16 pagesComputer Applications in ChemistryGanesh NNo ratings yet

- Despiece de La Caja de Transmision R1300GDocument3 pagesDespiece de La Caja de Transmision R1300GArmando Calderon YalleNo ratings yet

- Glenda Gloria Media in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesGlenda Gloria Media in The PhilippinesHappy Jayson Mondragon100% (1)