Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gender Equality in The Judiciary: 3. Public Employment

Gender Equality in The Judiciary: 3. Public Employment

Uploaded by

Talila SidaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Course: Digital Business Innovation Project: Hamley'SDocument7 pagesCourse: Digital Business Innovation Project: Hamley'SAkanksha Kar89% (9)

- In Re Atty. Emil Jurado Freedom of Expression and The Administration of JusticeDocument2 pagesIn Re Atty. Emil Jurado Freedom of Expression and The Administration of JusticeRowardNo ratings yet

- CLN4U Legal GlossaryDocument12 pagesCLN4U Legal GlossaryJulian HeidtNo ratings yet

- 7f55c675 enDocument3 pages7f55c675 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 8b8c48af enDocument3 pages8b8c48af enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 1d754cfc enDocument3 pages1d754cfc enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Salaries: 3. Public Employment and PayDocument3 pagesTeachers' Salaries: 3. Public Employment and PayJosé Ignacio Ortega GómezNo ratings yet

- B6d836a0 enDocument3 pagesB6d836a0 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Inclusive Government For A More Inclusive SocietyDocument26 pagesInclusive Government For A More Inclusive SocietyMarcelo Rodrigo RiffoNo ratings yet

- Future Fashion: Global Fashion Sales Growth Rates (%) Fashion Business SentimentDocument1 pageFuture Fashion: Global Fashion Sales Growth Rates (%) Fashion Business SentimentJeremy KurnNo ratings yet

- Negotiation Skills For Scientists Moving To IndustryDocument3 pagesNegotiation Skills For Scientists Moving To Industrymidosking-16No ratings yet

- Careers: Paths Less TravelledDocument4 pagesCareers: Paths Less TravelledJuan David Rodriguez HurtadoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Part1Document21 pagesChapter 1 Part1刘伟康No ratings yet

- SafariDocument1 pageSafariJana JanaNo ratings yet

- Utilize LinkedIn For Career Search CertificateDocument1 pageUtilize LinkedIn For Career Search CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Use Canva To Design Digital Course Collateral CertificateDocument1 pageUse Canva To Design Digital Course Collateral CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Comment: Restructure Science in South KoreaDocument3 pagesComment: Restructure Science in South KoreaAnonymous cjGn0KNo ratings yet

- Cunanan WebsiteDocument1 pageCunanan WebsiteMaxene DominiqueNo ratings yet

- 2a3b6f81 enDocument3 pages2a3b6f81 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Brief 1 - Play Now AshaDocument5 pagesBrief 1 - Play Now AshaAsha FarahNo ratings yet

- Cunanan-3D ModelingDocument1 pageCunanan-3D ModelingMaxene DominiqueNo ratings yet

- Guidelines CicshalDocument6 pagesGuidelines CicshalSergio Ricardo Alves de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- MACOMM-DENTSU BANGLADESH - AGENCY CREDENTIAL - Nov - 19 - Compressed-MinDocument51 pagesMACOMM-DENTSU BANGLADESH - AGENCY CREDENTIAL - Nov - 19 - Compressed-MinYaman HasanatNo ratings yet

- Design AI So That It's FairDocument3 pagesDesign AI So That It's FairmjohannakNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Part2Document29 pagesChapter 1 Part2刘伟康No ratings yet

- 9.data Science CertificateDocument1 page9.data Science CertificateP NAGESWARA RAONo ratings yet

- Coursera X36J64XU4Z7HDocument1 pageCoursera X36J64XU4Z7Hmanar mohamedNo ratings yet

- CGPPDocument173 pagesCGPPLynn ThetNo ratings yet

- fd9700c6 enDocument3 pagesfd9700c6 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Aso Sirwan Ahmed: Personal InformationDocument2 pagesAso Sirwan Ahmed: Personal InformationAso SerwanNo ratings yet

- Growing Great Writers With Writable CertificateDocument1 pageGrowing Great Writers With Writable CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Sketch UpDocument1 pageSketch Uplandachaitanya07No ratings yet

- Mehak Typescript Operator CertificateDocument1 pageMehak Typescript Operator Certificatemuizzalamgir99No ratings yet

- Coursera 59USUCZEQLZHDocument1 pageCoursera 59USUCZEQLZHFahad SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- TypeScript CertificateDocument1 pageTypeScript CertificateFahad SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Teacher As A Techno Pedagogue ImportanceDocument10 pagesTeacher As A Techno Pedagogue Importanceparvathy bNo ratings yet

- PYTHONDocument1 pagePYTHONRobinson Paredes FloresNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Microsoft Excel CertificateDocument1 pageIntroduction To Microsoft Excel CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Certificate Data Scientist IntroductionDocument1 pageCertificate Data Scientist IntroductionYoel Dwi Putra GultomNo ratings yet

- Citizenship and Rule of LawDocument1 pageCitizenship and Rule of LawsathwickbgNo ratings yet

- GithubDocument1 pageGithubrakshika2580No ratings yet

- Analyze User Research Data With Microsoft FormsDocument1 pageAnalyze User Research Data With Microsoft Formsassad.ullah1006No ratings yet

- An Updated Review of Hypertensive Emergencies and Urgencies: Katalin Makó, Corina Ureche, Zsuzsanna JeremiásDocument11 pagesAn Updated Review of Hypertensive Emergencies and Urgencies: Katalin Makó, Corina Ureche, Zsuzsanna JeremiásiganuryantiNo ratings yet

- Skill Matrix SRS FinalDocument63 pagesSkill Matrix SRS FinalAnil RajputNo ratings yet

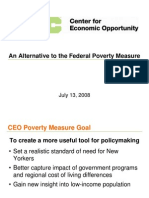

- Ceo Poverty MeasureDocument21 pagesCeo Poverty MeasureThomas B DonaldsonNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 CertificationDocument1 pageCovid-19 Certificationapi-546467833No ratings yet

- SRS Computers Presentation FINALDocument15 pagesSRS Computers Presentation FINALDaveNo ratings yet

- Articulo NatureDocument2 pagesArticulo Natureivan.quijano.aranibarNo ratings yet

- Camilo Andrés Espinosa Romero: Course CertificateDocument1 pageCamilo Andrés Espinosa Romero: Course CertificateCamilo Andres Espinosa RomeroNo ratings yet

- Create Charts and Dashboard Using Google Sheet CertificateDocument1 pageCreate Charts and Dashboard Using Google Sheet CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Heyder Adrián Cetzal Hau: Course CertificateDocument1 pageHeyder Adrián Cetzal Hau: Course CertificateHEYDER CETZALNo ratings yet

- A Biologist Talks To A PhysicistDocument4 pagesA Biologist Talks To A PhysicistBzar Blue ClnNo ratings yet

- ZBA Decision FairgroundsDocument2 pagesZBA Decision FairgroundsMCSNews ArchiveNo ratings yet

- 85ae5d36 enDocument3 pages85ae5d36 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 5 UNECE Sdgs Session 912Document9 pages5 UNECE Sdgs Session 912Walter Eduardo TeránNo ratings yet

- Information FactoriesDocument5 pagesInformation FactoriesmaheshNo ratings yet

- Doromal, MF Moceno, EM Gervacio, C Jovita, J Cale, J Mercado, M Bugas, E Amistad, ZDocument27 pagesDoromal, MF Moceno, EM Gervacio, C Jovita, J Cale, J Mercado, M Bugas, E Amistad, ZJesnefa JovitaNo ratings yet

- Ucsp Q1 Week8Document4 pagesUcsp Q1 Week8HanessyNo ratings yet

- Chat GPTDocument1 pageChat GPTAkashNo ratings yet

- Glexer Dazo Corrales: Course CertificateDocument1 pageGlexer Dazo Corrales: Course CertificateGlexer Dazo CorralesNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledFrenesel May Pilla MallorcaNo ratings yet

- News in Focus: Earth Is Warmer Than It'S Been in 125,000 Years, Says Landmark Climate ReportDocument2 pagesNews in Focus: Earth Is Warmer Than It'S Been in 125,000 Years, Says Landmark Climate ReportTarek BarhoumiNo ratings yet

- Cost Effectiveness: 13. Core Government ResultsDocument3 pagesCost Effectiveness: 13. Core Government ResultsTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- ENDEXDocument1 pageENDEXTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Youth Representation in Politics: 3. Public EmploymentDocument3 pagesYouth Representation in Politics: 3. Public EmploymentTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 8b8c48af enDocument3 pages8b8c48af enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Sovereign Climate and Nature Reporting: Proposal For A Risks and Opportunities Disclosure FrameworkDocument54 pagesSovereign Climate and Nature Reporting: Proposal For A Risks and Opportunities Disclosure FrameworkTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- MIS AssignmentDocument1 pageMIS AssignmentTalila Sida100% (2)

- 08ea873f enDocument3 pages08ea873f enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 314681ea enDocument4 pages314681ea enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 8eff3e63 enDocument3 pages8eff3e63 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 594feaa8 enDocument3 pages594feaa8 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 53fad860 enDocument3 pages53fad860 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- cdcc7bb2 enDocument3 pagescdcc7bb2 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 61b1564f enDocument3 pages61b1564f enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- IFAC How Global Standards Become LocalDocument2 pagesIFAC How Global Standards Become LocalTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 6fc55141 enDocument2 pages6fc55141 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- ECIIA Letter On ISSA 5000 Consultation Reaction FINAL ECIIA LETTER - 0Document4 pagesECIIA Letter On ISSA 5000 Consultation Reaction FINAL ECIIA LETTER - 0Talila SidaNo ratings yet

- Gri GSSB - Workprogram2023 2025Document13 pagesGri GSSB - Workprogram2023 2025Talila SidaNo ratings yet

- Crowe Global Comment Letter ED-5000 291123Document8 pagesCrowe Global Comment Letter ED-5000 291123Talila SidaNo ratings yet

- f707559f enDocument3 pagesf707559f enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 7f55c675 enDocument3 pages7f55c675 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 4c72add3 enDocument3 pages4c72add3 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 1c84b760 enDocument2 pages1c84b760 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 0acc66ae enDocument2 pages0acc66ae enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 4bff5b26 enDocument3 pages4bff5b26 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 0aa564d3 enDocument3 pages0aa564d3 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- IFAC G20 Call To AcionDocument1 pageIFAC G20 Call To AcionTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Gri Topic Standard Project For Climate Change Exposure DraftDocument56 pagesGri Topic Standard Project For Climate Change Exposure DraftTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- WBCSD Response To ISSA 5000 Consultation Submitted 30 NovemberDocument2 pagesWBCSD Response To ISSA 5000 Consultation Submitted 30 NovemberTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Financial Accounting I&II Course OutlineDocument6 pagesIntermediate Financial Accounting I&II Course OutlineTalila Sida100% (3)

- Cipfa Report Sustainability Reporting Time To Step It Up April 2023Document81 pagesCipfa Report Sustainability Reporting Time To Step It Up April 2023Talila SidaNo ratings yet

- Right To Disconnect Bill, 2018 in EnglishDocument10 pagesRight To Disconnect Bill, 2018 in EnglishLatest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Date of Decision: 18 August 2015Document19 pagesDate of Decision: 18 August 2015Aieshno FnsNo ratings yet

- National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW) vs. OvejeraDocument4 pagesNational Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW) vs. OvejeraRaymarc Elizer AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, RousseauDocument1 pageThomas Hobbes, John Locke, RousseauAhmed Blinky SulejmanovicNo ratings yet

- 1984 P.CR.L.J 2588Document6 pages1984 P.CR.L.J 2588Judicial AspirantNo ratings yet

- Canadian Business English Canadian 7th Edition by Guffey ISBN Test BankDocument19 pagesCanadian Business English Canadian 7th Edition by Guffey ISBN Test Bankwendy100% (29)

- People Vs MalunsingDocument1 pagePeople Vs MalunsingJelyn Delos Reyes TagleNo ratings yet

- National Action Plan NACTA PakistanDocument1 pageNational Action Plan NACTA PakistanMaher UsamaNo ratings yet

- Canon 6 - New Code of Judicial EthicsDocument19 pagesCanon 6 - New Code of Judicial EthicsAlyssa Mae Basallo67% (3)

- No Person Shall Be Compelled To Be A Witness Against HimselfDocument19 pagesNo Person Shall Be Compelled To Be A Witness Against HimselfKaren Sheila B. Mangusan - DegayNo ratings yet

- RTPS PPT 27-9-13Document39 pagesRTPS PPT 27-9-13Vivek Kankipati100% (1)

- 1 in Re Torres 2017Document1 page1 in Re Torres 2017KM Mac100% (1)

- Nocum Vs TanDocument2 pagesNocum Vs Tanangelescrishanne100% (1)

- Cases Feb 16Document11 pagesCases Feb 16Basri JayNo ratings yet

- Question Bank For Criminal Procedure Code, 1973Document2 pagesQuestion Bank For Criminal Procedure Code, 1973Aishwarya MathewNo ratings yet

- Roman Catholic vs. LRCDocument1 pageRoman Catholic vs. LRCVEDIA GENON0% (1)

- Cabrera v. Horgas, 10th Cir. (1999)Document2 pagesCabrera v. Horgas, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Napoles Vs de Lima 2016Document16 pagesNapoles Vs de Lima 2016Anthony Isidro Bayawa IVNo ratings yet

- Înoarce-Te, Pisică!Document18 pagesÎnoarce-Te, Pisică!Vlad IndrecanNo ratings yet

- Appropriate Dispute Resolution: Atty. Brenda Jay Angeles MendozaDocument5 pagesAppropriate Dispute Resolution: Atty. Brenda Jay Angeles MendozaGian Tristan MadridNo ratings yet

- Fairfax County Public Schools Internal Security Review RecommendationsDocument28 pagesFairfax County Public Schools Internal Security Review RecommendationsFOX 5 NewsNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Case Analysis: Google in China 1Document5 pagesRunning Head: Case Analysis: Google in China 1Kipkemboi2No ratings yet

- Complaint Against Thomas Lopez-PierreDocument20 pagesComplaint Against Thomas Lopez-PierreMichael BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Human Rights: Fall 2014 Prof. Inés Valdez Session 9: Critiques of RightsDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Human Rights: Fall 2014 Prof. Inés Valdez Session 9: Critiques of RightsKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Fflangress Of: ( Ixfprallj Dongress ®L (TR& Gular EsstnnDocument13 pagesFflangress Of: ( Ixfprallj Dongress ®L (TR& Gular EsstnngaryNo ratings yet

- 18B139, Laws On Mob-LynchingDocument16 pages18B139, Laws On Mob-LynchingMayank AameriaNo ratings yet

- APA Vs MLA Vs Chicago Vs Harvard Referencing StylesDocument8 pagesAPA Vs MLA Vs Chicago Vs Harvard Referencing StylesDanilo CumpioNo ratings yet

Gender Equality in The Judiciary: 3. Public Employment

Gender Equality in The Judiciary: 3. Public Employment

Uploaded by

Talila SidaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gender Equality in The Judiciary: 3. Public Employment

Gender Equality in The Judiciary: 3. Public Employment

Uploaded by

Talila SidaCopyright:

Available Formats

3.

PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT

Gender equality in the judiciary

Ensuring gender balance in judicial leadership has been

increasingly highlighted by OECD countries as a key Methodology and definitions

governance issue related to fairness, transparency and the

effectiveness of rule of law (OECD, 2019). A diverse judicial Data on the gender equality of professional judges

workforce can bring different voices and perspectives to refers to the overall share of women occupying

the bench. Such diversity and gender balance can also judgeship positions in 2016 and 2018 in courts of all

strengthen the integrity of the judiciary, promoting citizen’s instances. The data were retrieved from CEPEJ-STAT,

trust in justice services. Greater participation of women in a dynamic database of European judicial systems of

judicial professions, particularly at senior levels, can also the Council of Europe European Commission for the

help reduce gender stereotypes and increase women’s Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ).

willingness to enforce their rights. Data on the gender equality of professional judges

As of 2018, women made up 61% of the judiciary in the by court refers to the share of women occupying

OECD-EU countries, ranging from 81% in Latvia to 33% judgeships in three levels of courts as of 2018: first

in the United Kingdom. Overall, in most OECD countries, instance, second instance and supreme courts. The

gender representation across the judiciary has remained data were retrieved from the CEPEJ-STAT.

fairly constant or has marginally increased compared to Courts of first instance are where legal proceedings

2016. On average during this period the share of women begin, courts of second instance review decisions issued

judges increased by 2 p.p. The greatest increase in the by lower courts and supreme courts are the highest

share of women judges was recorded in Turkey (5 p.p.) courts within the hierarchy of many legal jurisdictions

but there were marginal declines of 1 p.p. in Iceland and and primarily function as appeal courts, reviewing

Israel. When comparing gender balance among judges, it decisions of lower and intermediate-level courts.

is important to consider the unique features of national Professional judges are those recruited, trained and

legal systems and professional development patterns. For remunerated to perform the function of a judge as a

example, differences exist between the civil law system main occupation. This category includes professional

and the common law system: in the former, women can judges from first instance, second instance and

be recruited directly from law schools before they face supreme courts.

possible career disruptions, while in the latter, women

face a statutory requirement for at least five or seven years

post-qualification experience for legally qualified posts in

the judiciary (Figure 3.14). Further reading

However, uneven gender representation continues to OECD (2019), Fast Forward to Gender Equality: Mainstreaming,

be observed in high-level courts, with significant gaps Implementation and Leadership, OECD Publishing, Paris,

observed at the supreme court level. In fact, on average the https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9faa5-en.

share of female judges in supreme courts across OECD-EU OECD (2018), Toolkit for Mainstreaming and Implementing

countries, recorded a value of 36% in 2018 (Figure 3.15). Gender Equality, OECD website, www.oecd.org/gender/

In comparison, the average share of female judges was 63% governance/toolkit/.

in first instance courts and 54% in second instance courts

OECD (2016), 2015 OECD Recommendation of the Council

across OECD-EU countries in 2018. This pattern can be on Gender Equality in Public Life, OECD Publishing,

explained by several persistent barriers to access to judicial Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252820-en.

positions for women, such as gender stereotypes and

biases and challenges in reconciliating work and life due

to a culture of long working hours. Lack of empowerment, Figure notes

mentoring, networking and professional development

Germany, Greece and Poland have not been included in the average

opportunities can also hamper women’s presence in the because of missing time series.

pool of senior judicial positions.

Data for the United Kingdom calculated as a simple average of the share

of female judges in England and Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland.

112 Government at a Glance 2021 © OECD 2021

3. PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT

Gender equality in the judiciary

3.14. Gender equality of professional judges, 2016 and 2018

2016 2018

% of women

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

A

T

E

A

BE

IR

IS

CH

ES

PR

CZ

IT

AU

SW

LV

ES

DN

LU

SV

FR

BR

FI

IS

TU

HU

NO

GB

NL

-E

SV

LT

CD

OE

Source: Council of Europe European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) CEPEJ-STAT (database),

12 https://doi.org/10.1787/888934257584

3.15. Gender equality of professional judges by level of court, 2018

First instance Second instance Supreme court

% of women

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

A

N

U

U

U

BE

IR

IS

PR

PO

CH

ES

CZ

IT

AU

SW

LV

ES

DN

LU

SV

FR

FI

HU

IS

TU

DE

NO

GB

NL

-E

SV

LT

CD

OE

Source: Council of Europe European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) CEPEJ-STAT (database),

12 https://doi.org/10.1787/888934257603

Government at a Glance 2021 © OECD 2021 113

From:

Government at a Glance 2021

Access the complete publication at:

https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en

Please cite this chapter as:

OECD (2021), “Gender equality in the judiciary”, in Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/2f520410-en

This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments

employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries.

This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any

territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Extracts from

publications may be subject to additional disclaimers, which are set out in the complete version of the publication, available at

the link provided.

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at

http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.

You might also like

- Course: Digital Business Innovation Project: Hamley'SDocument7 pagesCourse: Digital Business Innovation Project: Hamley'SAkanksha Kar89% (9)

- In Re Atty. Emil Jurado Freedom of Expression and The Administration of JusticeDocument2 pagesIn Re Atty. Emil Jurado Freedom of Expression and The Administration of JusticeRowardNo ratings yet

- CLN4U Legal GlossaryDocument12 pagesCLN4U Legal GlossaryJulian HeidtNo ratings yet

- 7f55c675 enDocument3 pages7f55c675 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 8b8c48af enDocument3 pages8b8c48af enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 1d754cfc enDocument3 pages1d754cfc enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Salaries: 3. Public Employment and PayDocument3 pagesTeachers' Salaries: 3. Public Employment and PayJosé Ignacio Ortega GómezNo ratings yet

- B6d836a0 enDocument3 pagesB6d836a0 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Inclusive Government For A More Inclusive SocietyDocument26 pagesInclusive Government For A More Inclusive SocietyMarcelo Rodrigo RiffoNo ratings yet

- Future Fashion: Global Fashion Sales Growth Rates (%) Fashion Business SentimentDocument1 pageFuture Fashion: Global Fashion Sales Growth Rates (%) Fashion Business SentimentJeremy KurnNo ratings yet

- Negotiation Skills For Scientists Moving To IndustryDocument3 pagesNegotiation Skills For Scientists Moving To Industrymidosking-16No ratings yet

- Careers: Paths Less TravelledDocument4 pagesCareers: Paths Less TravelledJuan David Rodriguez HurtadoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Part1Document21 pagesChapter 1 Part1刘伟康No ratings yet

- SafariDocument1 pageSafariJana JanaNo ratings yet

- Utilize LinkedIn For Career Search CertificateDocument1 pageUtilize LinkedIn For Career Search CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Use Canva To Design Digital Course Collateral CertificateDocument1 pageUse Canva To Design Digital Course Collateral CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Comment: Restructure Science in South KoreaDocument3 pagesComment: Restructure Science in South KoreaAnonymous cjGn0KNo ratings yet

- Cunanan WebsiteDocument1 pageCunanan WebsiteMaxene DominiqueNo ratings yet

- 2a3b6f81 enDocument3 pages2a3b6f81 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Brief 1 - Play Now AshaDocument5 pagesBrief 1 - Play Now AshaAsha FarahNo ratings yet

- Cunanan-3D ModelingDocument1 pageCunanan-3D ModelingMaxene DominiqueNo ratings yet

- Guidelines CicshalDocument6 pagesGuidelines CicshalSergio Ricardo Alves de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- MACOMM-DENTSU BANGLADESH - AGENCY CREDENTIAL - Nov - 19 - Compressed-MinDocument51 pagesMACOMM-DENTSU BANGLADESH - AGENCY CREDENTIAL - Nov - 19 - Compressed-MinYaman HasanatNo ratings yet

- Design AI So That It's FairDocument3 pagesDesign AI So That It's FairmjohannakNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Part2Document29 pagesChapter 1 Part2刘伟康No ratings yet

- 9.data Science CertificateDocument1 page9.data Science CertificateP NAGESWARA RAONo ratings yet

- Coursera X36J64XU4Z7HDocument1 pageCoursera X36J64XU4Z7Hmanar mohamedNo ratings yet

- CGPPDocument173 pagesCGPPLynn ThetNo ratings yet

- fd9700c6 enDocument3 pagesfd9700c6 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Aso Sirwan Ahmed: Personal InformationDocument2 pagesAso Sirwan Ahmed: Personal InformationAso SerwanNo ratings yet

- Growing Great Writers With Writable CertificateDocument1 pageGrowing Great Writers With Writable CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Sketch UpDocument1 pageSketch Uplandachaitanya07No ratings yet

- Mehak Typescript Operator CertificateDocument1 pageMehak Typescript Operator Certificatemuizzalamgir99No ratings yet

- Coursera 59USUCZEQLZHDocument1 pageCoursera 59USUCZEQLZHFahad SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- TypeScript CertificateDocument1 pageTypeScript CertificateFahad SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Teacher As A Techno Pedagogue ImportanceDocument10 pagesTeacher As A Techno Pedagogue Importanceparvathy bNo ratings yet

- PYTHONDocument1 pagePYTHONRobinson Paredes FloresNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Microsoft Excel CertificateDocument1 pageIntroduction To Microsoft Excel CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Certificate Data Scientist IntroductionDocument1 pageCertificate Data Scientist IntroductionYoel Dwi Putra GultomNo ratings yet

- Citizenship and Rule of LawDocument1 pageCitizenship and Rule of LawsathwickbgNo ratings yet

- GithubDocument1 pageGithubrakshika2580No ratings yet

- Analyze User Research Data With Microsoft FormsDocument1 pageAnalyze User Research Data With Microsoft Formsassad.ullah1006No ratings yet

- An Updated Review of Hypertensive Emergencies and Urgencies: Katalin Makó, Corina Ureche, Zsuzsanna JeremiásDocument11 pagesAn Updated Review of Hypertensive Emergencies and Urgencies: Katalin Makó, Corina Ureche, Zsuzsanna JeremiásiganuryantiNo ratings yet

- Skill Matrix SRS FinalDocument63 pagesSkill Matrix SRS FinalAnil RajputNo ratings yet

- Ceo Poverty MeasureDocument21 pagesCeo Poverty MeasureThomas B DonaldsonNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 CertificationDocument1 pageCovid-19 Certificationapi-546467833No ratings yet

- SRS Computers Presentation FINALDocument15 pagesSRS Computers Presentation FINALDaveNo ratings yet

- Articulo NatureDocument2 pagesArticulo Natureivan.quijano.aranibarNo ratings yet

- Camilo Andrés Espinosa Romero: Course CertificateDocument1 pageCamilo Andrés Espinosa Romero: Course CertificateCamilo Andres Espinosa RomeroNo ratings yet

- Create Charts and Dashboard Using Google Sheet CertificateDocument1 pageCreate Charts and Dashboard Using Google Sheet CertificateIan DiestroNo ratings yet

- Heyder Adrián Cetzal Hau: Course CertificateDocument1 pageHeyder Adrián Cetzal Hau: Course CertificateHEYDER CETZALNo ratings yet

- A Biologist Talks To A PhysicistDocument4 pagesA Biologist Talks To A PhysicistBzar Blue ClnNo ratings yet

- ZBA Decision FairgroundsDocument2 pagesZBA Decision FairgroundsMCSNews ArchiveNo ratings yet

- 85ae5d36 enDocument3 pages85ae5d36 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 5 UNECE Sdgs Session 912Document9 pages5 UNECE Sdgs Session 912Walter Eduardo TeránNo ratings yet

- Information FactoriesDocument5 pagesInformation FactoriesmaheshNo ratings yet

- Doromal, MF Moceno, EM Gervacio, C Jovita, J Cale, J Mercado, M Bugas, E Amistad, ZDocument27 pagesDoromal, MF Moceno, EM Gervacio, C Jovita, J Cale, J Mercado, M Bugas, E Amistad, ZJesnefa JovitaNo ratings yet

- Ucsp Q1 Week8Document4 pagesUcsp Q1 Week8HanessyNo ratings yet

- Chat GPTDocument1 pageChat GPTAkashNo ratings yet

- Glexer Dazo Corrales: Course CertificateDocument1 pageGlexer Dazo Corrales: Course CertificateGlexer Dazo CorralesNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledFrenesel May Pilla MallorcaNo ratings yet

- News in Focus: Earth Is Warmer Than It'S Been in 125,000 Years, Says Landmark Climate ReportDocument2 pagesNews in Focus: Earth Is Warmer Than It'S Been in 125,000 Years, Says Landmark Climate ReportTarek BarhoumiNo ratings yet

- Cost Effectiveness: 13. Core Government ResultsDocument3 pagesCost Effectiveness: 13. Core Government ResultsTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- ENDEXDocument1 pageENDEXTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Youth Representation in Politics: 3. Public EmploymentDocument3 pagesYouth Representation in Politics: 3. Public EmploymentTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 8b8c48af enDocument3 pages8b8c48af enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Sovereign Climate and Nature Reporting: Proposal For A Risks and Opportunities Disclosure FrameworkDocument54 pagesSovereign Climate and Nature Reporting: Proposal For A Risks and Opportunities Disclosure FrameworkTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- MIS AssignmentDocument1 pageMIS AssignmentTalila Sida100% (2)

- 08ea873f enDocument3 pages08ea873f enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 314681ea enDocument4 pages314681ea enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 8eff3e63 enDocument3 pages8eff3e63 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 594feaa8 enDocument3 pages594feaa8 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 53fad860 enDocument3 pages53fad860 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- cdcc7bb2 enDocument3 pagescdcc7bb2 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 61b1564f enDocument3 pages61b1564f enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- IFAC How Global Standards Become LocalDocument2 pagesIFAC How Global Standards Become LocalTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 6fc55141 enDocument2 pages6fc55141 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- ECIIA Letter On ISSA 5000 Consultation Reaction FINAL ECIIA LETTER - 0Document4 pagesECIIA Letter On ISSA 5000 Consultation Reaction FINAL ECIIA LETTER - 0Talila SidaNo ratings yet

- Gri GSSB - Workprogram2023 2025Document13 pagesGri GSSB - Workprogram2023 2025Talila SidaNo ratings yet

- Crowe Global Comment Letter ED-5000 291123Document8 pagesCrowe Global Comment Letter ED-5000 291123Talila SidaNo ratings yet

- f707559f enDocument3 pagesf707559f enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 7f55c675 enDocument3 pages7f55c675 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 4c72add3 enDocument3 pages4c72add3 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 1c84b760 enDocument2 pages1c84b760 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 0acc66ae enDocument2 pages0acc66ae enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 4bff5b26 enDocument3 pages4bff5b26 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- 0aa564d3 enDocument3 pages0aa564d3 enTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- IFAC G20 Call To AcionDocument1 pageIFAC G20 Call To AcionTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Gri Topic Standard Project For Climate Change Exposure DraftDocument56 pagesGri Topic Standard Project For Climate Change Exposure DraftTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- WBCSD Response To ISSA 5000 Consultation Submitted 30 NovemberDocument2 pagesWBCSD Response To ISSA 5000 Consultation Submitted 30 NovemberTalila SidaNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Financial Accounting I&II Course OutlineDocument6 pagesIntermediate Financial Accounting I&II Course OutlineTalila Sida100% (3)

- Cipfa Report Sustainability Reporting Time To Step It Up April 2023Document81 pagesCipfa Report Sustainability Reporting Time To Step It Up April 2023Talila SidaNo ratings yet

- Right To Disconnect Bill, 2018 in EnglishDocument10 pagesRight To Disconnect Bill, 2018 in EnglishLatest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Date of Decision: 18 August 2015Document19 pagesDate of Decision: 18 August 2015Aieshno FnsNo ratings yet

- National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW) vs. OvejeraDocument4 pagesNational Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW) vs. OvejeraRaymarc Elizer AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, RousseauDocument1 pageThomas Hobbes, John Locke, RousseauAhmed Blinky SulejmanovicNo ratings yet

- 1984 P.CR.L.J 2588Document6 pages1984 P.CR.L.J 2588Judicial AspirantNo ratings yet

- Canadian Business English Canadian 7th Edition by Guffey ISBN Test BankDocument19 pagesCanadian Business English Canadian 7th Edition by Guffey ISBN Test Bankwendy100% (29)

- People Vs MalunsingDocument1 pagePeople Vs MalunsingJelyn Delos Reyes TagleNo ratings yet

- National Action Plan NACTA PakistanDocument1 pageNational Action Plan NACTA PakistanMaher UsamaNo ratings yet

- Canon 6 - New Code of Judicial EthicsDocument19 pagesCanon 6 - New Code of Judicial EthicsAlyssa Mae Basallo67% (3)

- No Person Shall Be Compelled To Be A Witness Against HimselfDocument19 pagesNo Person Shall Be Compelled To Be A Witness Against HimselfKaren Sheila B. Mangusan - DegayNo ratings yet

- RTPS PPT 27-9-13Document39 pagesRTPS PPT 27-9-13Vivek Kankipati100% (1)

- 1 in Re Torres 2017Document1 page1 in Re Torres 2017KM Mac100% (1)

- Nocum Vs TanDocument2 pagesNocum Vs Tanangelescrishanne100% (1)

- Cases Feb 16Document11 pagesCases Feb 16Basri JayNo ratings yet

- Question Bank For Criminal Procedure Code, 1973Document2 pagesQuestion Bank For Criminal Procedure Code, 1973Aishwarya MathewNo ratings yet

- Roman Catholic vs. LRCDocument1 pageRoman Catholic vs. LRCVEDIA GENON0% (1)

- Cabrera v. Horgas, 10th Cir. (1999)Document2 pagesCabrera v. Horgas, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Napoles Vs de Lima 2016Document16 pagesNapoles Vs de Lima 2016Anthony Isidro Bayawa IVNo ratings yet

- Înoarce-Te, Pisică!Document18 pagesÎnoarce-Te, Pisică!Vlad IndrecanNo ratings yet

- Appropriate Dispute Resolution: Atty. Brenda Jay Angeles MendozaDocument5 pagesAppropriate Dispute Resolution: Atty. Brenda Jay Angeles MendozaGian Tristan MadridNo ratings yet

- Fairfax County Public Schools Internal Security Review RecommendationsDocument28 pagesFairfax County Public Schools Internal Security Review RecommendationsFOX 5 NewsNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Case Analysis: Google in China 1Document5 pagesRunning Head: Case Analysis: Google in China 1Kipkemboi2No ratings yet

- Complaint Against Thomas Lopez-PierreDocument20 pagesComplaint Against Thomas Lopez-PierreMichael BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Human Rights: Fall 2014 Prof. Inés Valdez Session 9: Critiques of RightsDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Human Rights: Fall 2014 Prof. Inés Valdez Session 9: Critiques of RightsKailash SreeneevasinNo ratings yet

- Fflangress Of: ( Ixfprallj Dongress ®L (TR& Gular EsstnnDocument13 pagesFflangress Of: ( Ixfprallj Dongress ®L (TR& Gular EsstnngaryNo ratings yet

- 18B139, Laws On Mob-LynchingDocument16 pages18B139, Laws On Mob-LynchingMayank AameriaNo ratings yet

- APA Vs MLA Vs Chicago Vs Harvard Referencing StylesDocument8 pagesAPA Vs MLA Vs Chicago Vs Harvard Referencing StylesDanilo CumpioNo ratings yet