Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fox PopCultureArgument 2020

Fox PopCultureArgument 2020

Uploaded by

AndyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fox PopCultureArgument 2020

Fox PopCultureArgument 2020

Uploaded by

AndyCopyright:

Available Formats

Pop Culture as Argument and AspirationAuthor(s): Richard Fox

Source: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde , Vol. 176, No. 1, Special Section:

Pop Culture as Argument and Aspiration (2020), pp. 1-5

Published by: Brill

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26910981

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26910981?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Brill is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bijdragen tot de

Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde

This content downloaded from

180.249.165.98 on Wed, 10 Jan 2024 05:06:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en

Volkenkunde 176 (2020) 1–5 bki

brill.com/bki

Pop Culture as Argument and Aspiration

Richard Fox

Department of Pacific and Asian Studies, University of Victoria

rpfox@uvic.ca

Abstract

The scholarship on post-authoritarian Indonesia has taken a relatively passive atti-

tude to theorizing popular culture—either presupposing the category absolutely, or

invoking prior theorists as authorities without querying the coherence or applicabil-

ity of their accounts and terminology. As the contributions to this special issue mean

to suggest, the question of popular culture may require more careful consideration—

not least given its alleged importance for our understanding of recent developments

in politics, religion and the economy. This introductory essay provides a brief synopsis

of the articles and a survey of the key issues addressed.

Keywords

Indonesia – pop culture – media – critical theory – argument

Popular culture has figured prominently in the scholarship on post-authoritar-

ian Indonesia, seen to affect everything from party politics and the economy

to romance and religion.1 Alongside publications that aim to provide a survey

of the field, an extensive literature has developed around more detailed ana-

lyses of television, cinema, fashion, pop music, street art, and social media,

among other things.2 An important subset of these studies has focused on

1 The articles collected in this special issue were originally presented at the Annual Meetings

of the American Academy of Religion (November 2018, Denver, CO), at a panel discussion

entitled ‘Pop Culture as Argument: Contesting Religion, Gender and Romance in Contem-

porary Indonesia’.

2 A critical review of recent publications is presented in my contribution to this issue, in the

section entitled The Idea of Popular Culture.

© richard fox, 2020 | doi:10.1163/22134379-17601003

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License.

This content downloaded from

180.249.165.98 on Wed, 10 Jan 2024 05:06:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2 fox

the intersection with Islam, highlighting the complex relationship between

piety, entertainment, style, and consumption. This is arguably one of the more

dynamic fields in Indonesian studies today. Yet, for all its ethnographic and

analytic richness, and with but a few notable exceptions,3 this rapidly grow-

ing body of scholarship has tended to take the concept of ‘popular culture’

for granted—as if the term’s referent were self-evident, and its theorization

unproblematic. Put another way, it might be said that the scholarship on

post-authoritarian Indonesia has taken a relatively passive attitude to theoriz-

ing popular culture—either presupposing the category absolutely, or invoking

prior theorists as authorities without querying either the coherence or applic-

ability of their accounts and terminology. As the contributions to this special

issue aim to suggest, the question of popular culture may require more careful

consideration—not least given its alleged importance for our understanding

of recent developments in politics, religion, the economy, and so on.

In the first of the three articles, ‘A political dance in the rain’, Rosalia Namsai

Engchuan explores how queer cinematic practice has disrupted a wider ‘cli-

mate’ of homophobia and oppression. Despite the reform movement’s progress

in fighting for individual freedom, LGBT Indonesians are regularly subjected to

abuse, and in practice do not have equal access to the fundamental protections

putatively assured by law. The rise of nationalist homophobia in the late 1990s

(Boellstorff 2004) and its subsequent re-articulation under the aegis of Islamic

piety (Thajib 2015) have fuelled what Engchuan and others have described

in terms of a ‘moral panic’—as manifest in public debate, but also in violent

protest and bodily attack. Under the circumstances, it has become extremely

difficult—and often dangerous—to discuss openly the day-to-day forms of

discrimination suffered by LGBT Indonesians. For many, the organized and

aggressive support for a pious hetero-nationalism has foreclosed the possibility

of resistance. Either one is a good Muslim or one is queer, but never the twain

shall meet—or so the argument often goes. Facing such a seemingly intract-

able predicament, Engchuan describes how queer cinema has intervened to

challenge this disarticulation of queer voices—and quashing of queer lives—

by opening up possibilities for discussion and argument. Queer films, she says,

offer more than a mere ‘alternative’. As arguments, they ‘nullify’ the prevail-

ing ‘LGBT/Islam binary’. Using the example of a short film entitled On Friday

noon, Engchuan explores the rhetorical strategies—visual and verbal, aural and

otherwise—that community filmmakers deploy to ‘evoke empathy’ and spur

discussion. Engchuan has no illusions about the relative impact these small-

3 See, for example, Heryanto 2014; Hobart 2008; Jurriëns 2011.

Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde 176 (2020) 1–5

This content downloaded from

180.249.165.98 on Wed, 10 Jan 2024 05:06:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

pop culture as argument and aspiration 3

scale interventions may have on the ‘wider public sphere’. But she convincingly

shows how the performative ‘nullification’ of religio-nationalistic homophobia

can bring hope. The weather may be terrible—and the climate inhospitable—

but community filmmakers in Indonesia are out dancing in the rain, opening

up spaces to imagine and work toward a better future.

Developing a closely related set of issues, Andrea Decker presents a richly

complex account of gender, power, and performativity in the popular musical

genre of dangdut, tracing the transformation of public debate that has accom-

panied dangdut’s ongoing journey from village-level entertainment to nation-

ally televised extravaganza. Her account is at once historical and ethnographic,

drawing on a combination of media analysis and extensive ethnographic field-

work—all with an eye to Indonesia’s shifting articulations of sexuality, piety,

and nation. Decker describes how female dangdut singers performing along the

coastal Pantura Highway were—and indeed still are—admired for their ability

to attract large and enthusiastic audiences—reflecting, on her account, a tradi-

tionally Javanese conception of power. It was precisely this power to attract—

and, more specifically, the ability to elicit an irresistibly erotic response—that

animated public debates over dangdut from the late 1990s through to the early

2000s—as exemplified by ‘Inul-mania’, the controversy surrounding Inul Dar-

atista and her ‘drilling’ dance (see Faruk and Aprinus 2003; Weintraub 2008). In

more recent years, it seems the debate has shifted with the growing prominence

of dangdut on national television. Where the sexual power of women’s bodies

was previously said to endanger public morality, male performers are now shar-

ing the burden of expectation. As Decker notes, live dangdut shows have histor-

ically accommodated—and thrived upon—the sort of gender-bending ambi-

guity and non-normative sexuality from which Indonesian performative tradi-

tions have long derived both humour and entertainment. But, she argues, the

same cannot be said for national television, where ratings-minded producers

endeavour to create programmes suitable for middle-class consumption, as

informed by the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission’s prohibition on effem-

inate self-presentation for men—proscribing everything from the male use of

women’s clothing, make-up, and mannerism to female terms of address. It is

in facing such proscriptions, and the threat of public disapproval, that many

male dangdut performers have adopted Arabic-inflected lyrics and Islamically

themed styles of self-presentation in order to appear heteronormatively cowok

banget (‘super manly’)—perhaps especially when their off-screen lives may

suggest otherwise. Ironically, given the Broadcast Commission’s commitment

to protecting gendered minorities, the ban on public male effeminacy has res-

ulted in transgender women and other gendered minorities being ‘hidden for

their own protection’.

Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde 176 (2020) 1–5

This content downloaded from

180.249.165.98 on Wed, 10 Jan 2024 05:06:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

4 fox

Taken together, the analyses from Engchuan and Decker highlight the com-

plex relationship between piety, gender, and nation in post-authoritarian Indo-

nesia. They additionally draw attention to how fine-grained ethnographic and

historical research may challenge prevailing understandings of large-scale pro-

cesses that are conventionally described under the rubrics of globalization,

Islamization, and commercialization. Inspired by these and related issues, my

own contribution examines the underlying theoretical foundations for schol-

arly commentary on Indonesian media and popular culture, with a special

emphasis on depictions of piety, class, and romance. Reflecting critically on a

series of films and YouTube videos, I have tried to draw attention to some of the

difficulties entailed in our unreflective reliance on notions such as ‘the public

sphere’, ‘mediascapes’, and ‘the marketplace of ideas’. My central contention is

that, albeit convenient, the use of these terms—and the lines of enquiry they

embody—help to underwrite an otherwise inexplicable leap from the analyst’s

own ‘reading’ of films, pop songs, and the like to broader statements about soci-

ety as a whole. The upshot is that, in adopting such an approach, scholarship

exempts itself from the theories of representation that it presumes to impose

on Others—holding itself apart, as if it were able to refer objectively to a soci-

ological reality that pop culture can but simulate, and with reference to which

it may be contextualized. Drawing on a series of recent symposia on the theme

of How Indonesians argue,4 I have provisionally suggested we approach pop-

ular culture in terms of argument, construed broadly as an effort to address,

rebut, persuade, exemplify, or otherwise performatively transform the world

and one’s place within it. Among the other advantages of such an approach,

this may help to level the playing field, subjecting scholarship—as itself a form

of argument—to the same theoretical framing that we envisage for our pop-

culturally imagined Others.

Implicit in this approach is the idea that an important aspect of pop culture

is its orientation to the future—exemplifying aspirations that may be variously

emulated, decried, or ignored in the day-to-day practices of envisaging and

working toward a better life. Engchuan has shown how queer cinema embod-

ies a critique of existing homophobia and discrimination but at the same time

projects us forward to an idealized time yet to come—when LGBT Indonesians

gain equal recognition as citizens and members of the various overlapping

communities they help to constitute. Meanwhile, as queer cinema has leaned

forward, striving to actualize a new and inspiring future, Decker describes a

4 An overview of themes and presentations is available online here: www.criticalia.org/sympo

sia‑‑panels/how‑indonesians‑argue.html.

Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde 176 (2020) 1–5

This content downloaded from

180.249.165.98 on Wed, 10 Jan 2024 05:06:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

pop culture as argument and aspiration 5

contrasting scene in which dangdut performers trace a more defensive line—

working to forestall condemnation for appearing inadequately ‘manly’, and so

inadequately Indonesian. In so doing, they are working to garner popular sup-

port, and so succeed as performers in a crowded and unforgivingly competitive

field. It is in this respect that both queer cinema and televised dangdut are dir-

ected to realizing a particular vision for the future. Yet, as a form of argument,

the same may be said mutatis mutandis of scholarship. It, too, is an aspirational

practice oriented to transformation. The question is, what sort of future does

our work aspire to? And what sort of intellectual practice is best suited to that

end?

References

Boellstorff, T. (2004). ‘The emergence of political homophobia in Indonesia: Masculin-

ity and national belonging’, Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 69-4:465–86.

Faruk and S. Aprinus (2003). Hanya Inul. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Marwa.

Heryanto, A. (2014). Identity and pleasure: The politics of Indonesian screen culture.

Singapore: NUS Press.

Hobart, M. (2008). ‘Introduction: Why is entertainment television in Indonesia import-

ant?’, in: M. Hobart and R. Fox (eds), Entertainment media in Indonesia, vii–xv. Lon-

don and New York: Routledge.

Jurriëns, E. (2011). ‘A call for media ecology: The study of Indonesian popular culture

revisited’, Indonesia and the Malay World 39–114:197–219.

Thajib, F. (2015). ‘Living in a state of suspension: Emotional dimensions of normat-

ive violence towards Indonesian queers in Islamic legal discourse’, Kyoto Review

of Southeast Asia 18. https://kyotoreview.org/issue‑18/normative‑violence‑towards

‑indonesian‑queers/.

Weintraub, A. (2008). ‘“Dance drills, faith spills”: Islam, body politics, and popular

music in post-Suharto Indonesia’, Popular Music 27-3:367–92.

Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde 176 (2020) 1–5

This content downloaded from

180.249.165.98 on Wed, 10 Jan 2024 05:06:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Analysis of Rizal RetractionDocument6 pagesAnalysis of Rizal RetractionGail Embudo100% (8)

- Sermon Guide: How To Change Your MindDocument5 pagesSermon Guide: How To Change Your MindNiyonshuti YvesNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Numerology - Gematria The Mathematics of The TorahDocument11 pagesHebrew Numerology - Gematria The Mathematics of The Torahdav700% (1)

- Goldman V Hargrave (1967) 1 Ac 645 - PCDocument13 pagesGoldman V Hargrave (1967) 1 Ac 645 - PCAzizul KirosakiNo ratings yet

- A Decolonial Critique of Diaspora Identity Theories and The Notion of SuperdiversityDocument14 pagesA Decolonial Critique of Diaspora Identity Theories and The Notion of SuperdiversityBernardoMoraesNo ratings yet

- Social Networks: Wenhong ChenDocument12 pagesSocial Networks: Wenhong ChenCarolina Diartt GonzálezNo ratings yet

- The Female Nude - 1990Document14 pagesThe Female Nude - 1990Anonymous IC3j0ZSNo ratings yet

- E Povinelli Radical WorldsDocument17 pagesE Povinelli Radical WorldsAnonymous n4ZbiJXjNo ratings yet

- Disability in An Eastern Religious Context Historical PerspectivesDocument23 pagesDisability in An Eastern Religious Context Historical PerspectivesSinziana-Elena GrasuNo ratings yet

- Nead TheFemaleNudeDocument14 pagesNead TheFemaleNudeМария НикольскаяNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. Political Theory: This Content Downloaded From 144.82.108.120 On Thu, 11 Aug 2016 10:46:08 UTCDocument7 pagesSage Publications, Inc. Political Theory: This Content Downloaded From 144.82.108.120 On Thu, 11 Aug 2016 10:46:08 UTCPauCrneoNo ratings yet

- 'Language Ideologies and The 'Vernacular' in South Asian Colonial and Post-Colonial Literature(s) and Public Spheres' - H-Announce - H-NetDocument3 pages'Language Ideologies and The 'Vernacular' in South Asian Colonial and Post-Colonial Literature(s) and Public Spheres' - H-Announce - H-NetAalim AkhtarNo ratings yet

- The Nuevo Cancionero MovementDocument25 pagesThe Nuevo Cancionero MovementaguayorodriguezNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Cultural Distance and Cultural Music Video Consumpstion On YoutubeDocument19 pagesRelationship Between Cultural Distance and Cultural Music Video Consumpstion On YoutubeAfriza Bin Yuana ArifinNo ratings yet

- Spring 2016Document12 pagesSpring 2016CharlotteNo ratings yet

- Living Folklore: Unlimited Creativity: January 2019Document9 pagesLiving Folklore: Unlimited Creativity: January 2019teshomeNo ratings yet

- Florida State University Department of Philosophy Social Theory and PracticeDocument25 pagesFlorida State University Department of Philosophy Social Theory and Practiceanh haNo ratings yet

- British Forum For Ethnomusicology, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Ethnomusicology ForumDocument5 pagesBritish Forum For Ethnomusicology, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Ethnomusicology ForumMusicNo ratings yet

- Culture As Identity An Anthropologists ViewDocument16 pagesCulture As Identity An Anthropologists ViewAlper BilgilNo ratings yet

- Critical Essays On OthelloDocument8 pagesCritical Essays On Othelloafhbexrci100% (2)

- Sommers, Margaret - Whats Political or Cultural About Political Culture and The Public SphereDocument33 pagesSommers, Margaret - Whats Political or Cultural About Political Culture and The Public SpheremoyanodiazNo ratings yet

- Ijels-34 Jan-Feb 2022 PDFDocument7 pagesIjels-34 Jan-Feb 2022 PDFIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Presentation5sem3 220213084048Document10 pagesPresentation5sem3 22021308404898ashishhsinghNo ratings yet

- Cultureandpoliticsin Palestine IsraelDocument8 pagesCultureandpoliticsin Palestine IsraelAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- How Does Interculturalism Contrast With MulticulturalismDocument23 pagesHow Does Interculturalism Contrast With Multiculturalismสามชาย ศรีสันต์No ratings yet

- Beyond Tradition and Modernity in MadrasDocument37 pagesBeyond Tradition and Modernity in Madrasrahul krishnanNo ratings yet

- Introto Citizenshipin Diverse SocietiesDocument43 pagesIntroto Citizenshipin Diverse SocietiescrmagoamNo ratings yet

- Oramedia Three Case Studies in Participatory Media DevelopmentDocument11 pagesOramedia Three Case Studies in Participatory Media DevelopmentRatie GeeNo ratings yet

- Society For Comparative Studies in Society and History: Cambridge University PressDocument29 pagesSociety For Comparative Studies in Society and History: Cambridge University PressZeru YacobNo ratings yet

- Cultures of Consumption: Working Paper SeriesDocument46 pagesCultures of Consumption: Working Paper SeriesjoanjimenezNo ratings yet

- Cultural Appropriation - What It Is and Why It Matters?Document11 pagesCultural Appropriation - What It Is and Why It Matters?msfNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of Culture in Complex SocietiesDocument24 pagesThe Analysis of Culture in Complex SocietiesArthur PeciniNo ratings yet

- Cultural Studies Dissertation HelpDocument7 pagesCultural Studies Dissertation HelpBuyCollegePaperWestValleyCity100% (1)

- Culture and Identity in AnthropologyDocument27 pagesCulture and Identity in AnthropologyTatoNo ratings yet

- Hildegard Anne Maria Ma English ST - Alosyius College MangaloreDocument8 pagesHildegard Anne Maria Ma English ST - Alosyius College MangaloreHilde Gard AnneMariaNo ratings yet

- WEEK 12 (3) - Culture and Foreign Policy AnalysisDocument10 pagesWEEK 12 (3) - Culture and Foreign Policy AnalysisSankalp WadhwaniNo ratings yet

- (Optional) Prof. Dr. Robert W. Hefner Pap, Global Civiliz Progress Indo Lessons, Hefner 10-2021 Short VersionDocument8 pages(Optional) Prof. Dr. Robert W. Hefner Pap, Global Civiliz Progress Indo Lessons, Hefner 10-2021 Short Versionfitriansyah kamilNo ratings yet

- How To Overcome EthnocentrismDocument13 pagesHow To Overcome EthnocentrismGuilherme Rodrigues LeiteNo ratings yet

- Ethnomusicology.54.2.0318timothy RiceDocument9 pagesEthnomusicology.54.2.0318timothy RiceIliya KhaliliNo ratings yet

- Global Diversities The Nation Form in The Global Age Ethnographic Perspectives Palgrave Macmillan 2022 Irfan Ahmad and Jie Kang Full ChapterDocument68 pagesGlobal Diversities The Nation Form in The Global Age Ethnographic Perspectives Palgrave Macmillan 2022 Irfan Ahmad and Jie Kang Full Chaptervicki.raio639100% (8)

- EditedDocument5 pagesEditedWild WestNo ratings yet

- Defining Heroism From Folklore To MediaDocument12 pagesDefining Heroism From Folklore To MediaManshi YadavNo ratings yet

- Culture, Catastrophe, and Rhetoric: The Texture of Political ActionFrom EverandCulture, Catastrophe, and Rhetoric: The Texture of Political ActionNo ratings yet

- Kroskrity2021ArticulatingLingualLifeHistoriesandLanguageIdeologicalAssemblagescorrectedproof PDFDocument21 pagesKroskrity2021ArticulatingLingualLifeHistoriesandLanguageIdeologicalAssemblagescorrectedproof PDFMayra AlejandraNo ratings yet

- Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural StudiesDocument3 pagesArizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural StudiesPatricia LopezNo ratings yet

- CFC "Edited Volume On Holocaust in Popular Culture"Document10 pagesCFC "Edited Volume On Holocaust in Popular Culture"Silvia Del ZoppoNo ratings yet

- Bigenho GraspingCacophonyBolivian 2018Document36 pagesBigenho GraspingCacophonyBolivian 2018Lucas da Costa MacielNo ratings yet

- Milton Singer-Beyond Tradition and Modernity in MadrasDocument37 pagesMilton Singer-Beyond Tradition and Modernity in MadrasKusum LataNo ratings yet

- When Dance Becomes Political: Georgian Rave Culture As The Site of Global and Local Construction of PoliticsDocument47 pagesWhen Dance Becomes Political: Georgian Rave Culture As The Site of Global and Local Construction of PoliticsgerardNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 80.89.73.207 On Mon, 27 Sep 2021 09:41:28 UTCDocument11 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 80.89.73.207 On Mon, 27 Sep 2021 09:41:28 UTCymaNo ratings yet

- In Uence of Mayan Mythology On The Architecture of Eric Owen MossDocument107 pagesIn Uence of Mayan Mythology On The Architecture of Eric Owen MossRichard Kennith Asto AltamiranoNo ratings yet

- Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land - en Volkenkunde - Journal of The Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia) A Political Dance in The RainDocument30 pagesBijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land - en Volkenkunde - Journal of The Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia) A Political Dance in The Rainsri yadiNo ratings yet

- Introduction Situating Ethiopia in Genocide DebatesDocument15 pagesIntroduction Situating Ethiopia in Genocide Debatesሰሎሞን ገብረ ወልደኣናንያNo ratings yet

- Folklore and Media - Indian Folklife 18Document24 pagesFolklore and Media - Indian Folklife 18akunjinNo ratings yet

- A Virtual Ethnography Study - Fandom and Social Impact in Digital EraDocument14 pagesA Virtual Ethnography Study - Fandom and Social Impact in Digital EraYasyfa Nida SaffanahNo ratings yet

- The Nation Form in The Global Age Irfan Ahmad Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Nation Form in The Global Age Irfan Ahmad Full Chapterkevin.verne147100% (9)

- 10 2307@20452465 PDFDocument9 pages10 2307@20452465 PDFPauCrneoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document4 pagesChapter 2Vianne SaclausaNo ratings yet

- Conversation+Pieces +the+Role+of+Dialogue+in+Socially Engaged+ArtDocument16 pagesConversation+Pieces +the+Role+of+Dialogue+in+Socially Engaged+ArtAbdelaziz Zuñiga LopezNo ratings yet

- Boellstorff - Dubbing CulturesDocument19 pagesBoellstorff - Dubbing CulturesÍtalo TavaresNo ratings yet

- Culture, Prejudice, Racism, and DiscriminationDocument17 pagesCulture, Prejudice, Racism, and DiscriminationLola Abrahams AbelNo ratings yet

- 0 Heeren IntroductionDocument23 pages0 Heeren Introductiondhia al fajrNo ratings yet

- 37-40 DocxfffDocument5 pages37-40 DocxfffSilvi PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Grimshaw (2016) Styling The Occidental Other Interculturality in Chinese University PerformancesDocument17 pagesGrimshaw (2016) Styling The Occidental Other Interculturality in Chinese University Performances葛知性No ratings yet

- Hadith Qudsi 21 - 25Document3 pagesHadith Qudsi 21 - 25pcworld2No ratings yet

- GST203 Module 2Document37 pagesGST203 Module 2asalihu217No ratings yet

- Use of The Subud SymbolDocument2 pagesUse of The Subud Symbolapi-292896527No ratings yet

- Tourism YemenDocument2 pagesTourism YemenMohammed GamalNo ratings yet

- Jacob A Handful of Popular Sayings Vol 1Document76 pagesJacob A Handful of Popular Sayings Vol 1DrMvnpavana Kumara SarmaNo ratings yet

- PENRICE, John (1873) A Dictionary of KoranDocument191 pagesPENRICE, John (1873) A Dictionary of KoranJuan de HeratNo ratings yet

- TheHistoricalLandmarksandOtherEvidencesofFreemasonryExplained 10014306Document800 pagesTheHistoricalLandmarksandOtherEvidencesofFreemasonryExplained 10014306jurebieNo ratings yet

- Mind and Mental FactorsDocument7 pagesMind and Mental FactorsNgu HoangNo ratings yet

- (Anthony Pagden (Ed.) ) The Languages of PoliticalDocument374 pages(Anthony Pagden (Ed.) ) The Languages of PoliticalPabloMoscoso100% (3)

- Roman Greece, Greek Palestine. Original, Jan 2024 Edit. English, Arabic.Document6 pagesRoman Greece, Greek Palestine. Original, Jan 2024 Edit. English, Arabic.Alexander MaronNo ratings yet

- 100 Inspirational Quotes About HopeDocument9 pages100 Inspirational Quotes About HopesamNo ratings yet

- Read These Docs b4 We Die Lest We Die MORONIC!Document122 pagesRead These Docs b4 We Die Lest We Die MORONIC!Yusuf (Joe) Jussac, Jr. a.k.a unclejoeNo ratings yet

- GreekDocument3 pagesGreekALANNAH SABANDALNo ratings yet

- Definition and Elements, Material and Formal Object, Division, and Historical Development of EthicsDocument21 pagesDefinition and Elements, Material and Formal Object, Division, and Historical Development of EthicsKate EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- How To Be Quiet and Stop Thinking MeditationDocument41 pagesHow To Be Quiet and Stop Thinking MeditationPoojaChavan100% (1)

- Kregel Publications Fall 2009 CatalogDocument64 pagesKregel Publications Fall 2009 Catalognoellep100% (2)

- Instant Download Principles of Managerial Finance 13th Edition Gitman Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Principles of Managerial Finance 13th Edition Gitman Test Bank PDF Full Chaptersocketedfluoxjf5100% (14)

- A Pragmatic Analysis of Deixis in A Religious Text PDFDocument15 pagesA Pragmatic Analysis of Deixis in A Religious Text PDFArlisa HidayatiNo ratings yet

- Saima IshaqDocument63 pagesSaima IshaqAman Ullah GondalNo ratings yet

- Swami Viveka AnandaDocument105 pagesSwami Viveka AnandaVashikaran.OrgNo ratings yet

- ArroganceDocument5 pagesArroganceJavad Ahmad HurraNo ratings yet

- Ethical School of ThoughtsDocument27 pagesEthical School of ThoughtsPhil Cahilig-GariginovichNo ratings yet

- Vedic PrayerDocument2 pagesVedic PrayerRenuka Ranjith RamnunanNo ratings yet

- © John S. Romanides (Patriarch Athenagoras Memorial Lectures)Document48 pages© John S. Romanides (Patriarch Athenagoras Memorial Lectures)Nicholas Pantelopoulos50% (2)

- Bishops Homily - Holy Saturday Easter VigilDocument21 pagesBishops Homily - Holy Saturday Easter VigilMinnie AgdeppaNo ratings yet

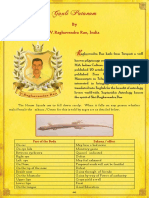

- Gauli Patanam: by V.Raghavendra Rao, IndiaDocument8 pagesGauli Patanam: by V.Raghavendra Rao, IndiaEmmanuel GrimaudNo ratings yet