Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mount Fuji - Icon of Japan

Mount Fuji - Icon of Japan

Uploaded by

vikidtioCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mount Fuji - Icon of Japan

Mount Fuji - Icon of Japan

Uploaded by

vikidtioCopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Reviewed Work(s): Mount Fuji: Icon of Japan by H. Byron Earhart

Review by: Gaynor Sekimori

Source: Monumenta Nipponica , 2013, Vol. 68, No. 1 (2013), pp. 110-114

Published by: Sophia University

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43864597

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sophia University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Monumenta Nipponica

This content downloaded from

62.44.108.57 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 13:59:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

no Monumenta Nipponica 68:1 (2013)

Tatsuta, but the combination . . . leaves no doubt about its autumn identity" (p. 69).

The associations were, by the Edo period, strong enough to define the status of these

places as meisho , vestiges of which remain important even today: at Mt. Yoshino,

cedar stands in the Okusenbon portion of the mountain are being felled to make way

for cherry trees to please the hordes of visitors who, in imitation of their Edo-period

ancestors, go to the site made famous by Saigyõ and others for its blossoms.

In general, the path toward the Edo period leads the reader to the complex world

of the urbanités of early modernity, to haikai and haiku, to mitate (visual transposi-

tion) at its most parodie, and to the vitally important development of urban ports

and the new relationship to the sea that these created. Shiranes provocative discus-

sion in chapters 6 and 7 of Edo seasonal referentiality- which was influenced by

urban living, by the importance of sea fish in cuisine, and by scientific discourse and

technology- draws an essential link between the classical past and modern life. The

books conclusion places this discussion even more firmly within the wider net-

work of concerns about the character of urban early modernity and its connection

to modernity and postmodernity. These last chapters are provocative and leave the

reader wanting to linger in the complex world of kaiseki menus, the kabuki calen-

dar, woodblock print art, and tourism - all topics that are part of the growing body

of literature on Edo life and culture both in Japan and abroad. The way in which

Japan and the Culture of the Four Seasons underlines the vitality of the classical past

in early modernity, articulating continuity as well as change, mark this book as a

vital contribution to our understanding of the literature, art, and daily practices of

Japan over the centuries.

Mount Fuji : Icon of Japan. By H. Byron Earhart. University of South Carolina

Press, 2011. 262 pages. Hardcover $39.95.

Gaynor Sekimori

SOAS, University of London

In September i860, Rutherford Alcock, consul general at the British legation in

set out from the consulate in Kanagawa with eight companions. They included

Lieutenant Robinson of the Indian navy, who carried "a few instruments for the pur

pose of scientific observations," and Mr. Veitch, "a son of the well-known Lon

horticulturist," who intended to study the mountain vegetation of "Fusiyama."1

"Japanese Ministers" had tried to dissuade Alcock from the "pilgrimage," telling

that "it was not fitting in a person of the rank of a British Envoy to make the pilgr

age, limited by custom if not by law to the lower classes." Insisting, however, th

was "the free right" of the head of a diplomatic mission "to travel all over the empir

1 Rutherford Alcock, The Capital of the Tycoon: A Narrative of a Three Years Residence in Jap

vol. 1 (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1863), p. 397.

2 Alcock 1863, p. 396.

This content downloaded from

62.44.108.57 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 13:59:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BOOK REVIEWS 111

he overcame official objections and f

leader of a virtual pilgrimage group:

under every imaginable pretext, had,

without limit, to the party. ... To ma

with the natives, to which deliveranc

gether there were more than 120 peo

officials, and some 60 porters.

Besides using the expedition for pol

both recreation and observation. To h

picturesque. The contrast between lei

regard to Fuji is neatly encapsulated

who, at Hakone, proceeded to boil his

infinite astonishment of some native at

Once the ascent started, from Mura

southern foot of Mt. Fuji), the part

the fourteenth century, a priest calle

sequently underpinned the Fuji ascen

( nyübu ) practices of other Shugend

Alcock stayed was probably Kõhõji, t

was abolished as a result of the shinbu

leaving the present Sengen Jinja as t

priests" were provided as guides, and

Alcock described the pilgrims as bein

they are careful to have stamped wit

the bonzes located there during the s

mit they hoisted the Union flag, fire

measuring the size of the crater and

clashing variance with the religious ac

Alcocks ascent of Fuji provides a ne

images" displayed by the mountai

described by H. Byron Earhart in Mo

of the imagination, gazed upon from

James Kirkup wrote that climbing F

the physical mountain is also clothed

divine, whether it be the heaven of

of Dainichi, or the realm of Asama

for most of its history, Fuji was trodd

3 Alcock 1863, pp. 398-99.

4 Alcock 1863, p. 415.

5 Alcock 1863, p. 426.

6 James Kirkup, These Horned Islands: A J

This content downloaded from

62.44.108.57 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 13:59:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

112 Monumenta Nipponica 68:1 (2013)

form of ascesis, whether by professionals (usually shugenja/yamabushi) or lay believ-

ers under their guidance. Saigyö, a religious practitioner as well as a poet, went so

far as to imagine the mountain as a symbol of impermanence, conferring upon it an

existence even further removed from its status as a physical presence.

Though Earharts interests, given his long-term academic concern with Shugendõ

and mountain religion, are firmly focused on Fuji as a sacred mountain, he has used

a wide variety of secondary sources, mainly in English, to present with great finesse

a variegated picture of the "natural, cultural, spiritual, and symbolic drama that Fuji

has played out" (p. 190). Though in places a great deal of material not directly related

to Fuji is provided (as for example in the chapter on japonisme)y this by no means

detracts from the narrative, but rather acts to give rich context, as well as useful

sources for further research on the part of the reader.

The poets and artists who extolled Fuji tended to look upon it as a representa-

tive symbol, generally viewed from a distance. Earhart describes how poems in the

Manyöshü focus on its "aesthetic grandeur," as the "lofty peak" (p. 9), while in the

later Kokinshü and other works, Fujis physical nature is used as a metaphor for love

("deathless/hidden fires," "eternal smoke"; pp. 12-13). The earliest graphic portray-

als of the mountain tended to see it not as an actual Japanese mountain but as an

ideal Chinese one, with three peaks and verdant vegetation rather than snow. Inter-

estingly, in both shape and coloring, the mountain as portrayed in Hata no Chitei s

yamato-e style Shõtoku Taishi eden of 1069 has much in common with the sixteenth-

century Fuji pilgrimage scroll attributed to Kanõ Motonobu (reproduced in the book

as plate 3), as well as with Hokusai s famous "Shower below the Summit" (plate 1)

and Rutherford Alcocks illustration of the mountain "The Ascent of Fusiyama."7 The

dimensions of medieval suibokuga , on the other hand, are closer to the flatter style

of the printmakers like Hiroshige (as depicted in plates 5 and 6). But even today, the

average Japanese will, if asked to draw Fuji, still portray it as a cone with three peaks,

which has nothing to do with its actual shape.

Perhaps the best way to understand the physical mountain, Earhart argues, is in

terms of relationship. This notion appears visually in Hiroshige s One Hundred Famous

Views o/Edo, where Fuji is brought to the capital to legitimate or sanctify it and Edo

is transported to the "realm of the ethereal peak" (p. 102). The presence of miniature

Fujis (fujizuka ) in Edo was another aspect of this idea. Religious practitioners went

into the sacred realm of the mountain to enter a relationship with the divine, and the

mountain can also be seen in terms of divine relationships. For example, as Earhart

explains, the twelfth-century Matsudai Shõnin, in discovering the equality between

the divinities associated with the mountain (such as Asama Daimyõjin, Sengen Dai-

bosatsu, and Dainichi Nyorai), understood that Fuji united the kami and buddhas

and transcended male and female. Ascetic practice on the mountain stressed the

relationship between this world and the "other"; as at other sacred mountains, prac-

7 Alcock 1863, facing p. 425 (chromolithograph by M. and N. Hanhart).

This content downloaded from

62.44.108.57 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 13:59:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BOOK REVIEWS 113

titioners symbolically died on entering the mo

course of making pilgrimage to its sacred si

cises, and emerged reborn. Murayama was th

ment that supervised both its own shugenja

Earhart takes up the various confraternitie

sacred. These groups, he explains, can be tra

to whom the mountain embodied all sacred p

the realm and relieve all suffering. The gro

related to the growth of Edo itself, and com

the course of the eighteenth century cente

and the Miroku-ha of Jikigyõ Miroku. The

came to be known as Fujidõ, which was par

and Rokugyõ Sanshi. Within Fujidõ, radical

inspired Sanshi to take women to the summi

sacred mountains, closed to female access. (

by Sanshi, became the first woman recorded

From the middle of the eighteenth century

greater movement around the country. It w

sure travel, which were often hard to distin

pher Kan (Nakagawa) Tenju climbed Hakusan

Ike Taiga and Kõ Fuyõ; it is significant that

dosha" (pilgrims to the three peaks); dosha w

to lay mountain pilgrims at many sites. Incr

to as a "complex negotiation between visitor

emerged both as "a domestic national symbo

(p. 110). The expansion of the culture of printi

played an important role in this, both domes

From late Tokugawa into the Meiji period,

interests" (p. 122); the Meiji governments cul

ple on banknotes and postage stamps- to co

the light of the mountains history, no new

use in wartime propaganda, Fuji later became

war mission of peace. This change illustrate

tain as an "enduring and malleable icon of Ja

Earhart divides his material into five sectio

Mountain," discusses the natural and cultura

status as an ideal mountain in early poetry

Shugendõ. Part 2, "The Dynamics of a Cosmic

ascetics Kakugyõ and Jikigyõ Miroku and th

8 Mary Beard, Confronting the Classics: Traditions

Books, 2013), p. 236.

This content downloaded from

62.44.108.57 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 13:59:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

114 Monumenta Nipponica 68:1 (2013)

confraternities. Part 3, "Fuji as Visual Ideal and Political Idea," discusses representa-

tions of Fuji in woodblock prints, and on money and postage stamps. Of particular

interest are the chapter on japonisme, which brings together various sources to give a

wide-ranging sketch of the Western discovery of ukiyo-e, and a subsequent chapter

that frames Japans identity in the modern period, drawing attention to pre-Meiji art-

ists and writers such as Ogyù Sorai, Hiraga Gennai, and Shiba Kõkan and taking up

the appearance of Fuji in Meiji-period school textbooks and the use of its image on

money and stamps. Part 4, "Fuji Devotion in Contemporary Japan," gives an excel-

lent overview of several Fuji-centered religious movements, Fujikõ, Miyamotokõ,

Murayamakyõ, and Gedatsukai. It includes the results of a survey conducted by Ear-

hart of members of three current Fuji groups, data that is useful for identifying dis-

tinctive patterns of Fuji belief and practice. (Earhart also made a valuable film of

these groups in the early 1990s, and this became commercially available in 1998.) Part

5, "Fuji the Flexible Symbol," deals with how Fuji has been used in war and peace for

propaganda, and in commerce as a stereotype and commercial logo. Here Earhart

discusses both Western and "reverse" orientalism, giving as an example of the former

Wanda Jacksons song Fujiyama Mama .

In his epilogue, Earhart reminds us that whatever the future holds, Fuji remains a

tabula rasa, ever adaptable "in a wide range of artistic genres and religious milieux,

as well as in diverse social and political settings" (p. 193). The mountain continues,

indeed, to play various roles in Japans understanding and presentation of itself. The

year 2013 marks the 150th anniversary of the arrival in the United Kingdom of five

young men from Chôshù- including Itõ Hirobumi, who would later become prime

minister- to study at University College London. On 3 July, the college hosted a

reception to commemorate this event, during which the university received a dona-

tion of a painting by a descendant of Itõ intended to encapsulate the achievement of

the "Chôshù Five." Its subject? Mt Fuji.

Im Wettstreit mit dem Westen : Japans Zeitalter der Ausstellungen 1854-1941 .

By Daniel Hedinger. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2011. 458 pages. Softcover

€45.00.

Michael Facius

Freie Universität Berlin

In his introduction to the book under review, Daniel Hedinger recounts the follow-

ing episode: When Commodore Matthew Perry landed in Edo bay to extract a treaty

from the Tokugawa government in 1854, he had in tow what- in the words of an

observer- amounted to a "full-sized industrial exhibition" (p. 34), including a length

of railroad track and a locomotive. The purpose of this gift was, of course, to impress

the Japanese negotiators and convince them of American technological and military

This content downloaded from

62.44.108.57 on Thu, 11 Jan 2024 13:59:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Ghosts And The Japanese: Cultural Experience in Japanese Death LegendsFrom EverandGhosts And The Japanese: Cultural Experience in Japanese Death LegendsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (12)

- Munakata FamilyDocument140 pagesMunakata FamilysleepwalkNo ratings yet

- THEO 201 Educational PhilosophyDocument24 pagesTHEO 201 Educational PhilosophySamantha Collyn GomezNo ratings yet

- Answers To Practice For Ethos Pathos Logos Rhetorical Devices and ToulminDocument5 pagesAnswers To Practice For Ethos Pathos Logos Rhetorical Devices and ToulmindianeNo ratings yet

- Japan in A NutshellDocument160 pagesJapan in A NutshellProfessor Solomon100% (25)

- History of JapanDocument10 pagesHistory of Japanjazziebrown284No ratings yet

- Yotsuya Kwaidan 1Document136 pagesYotsuya Kwaidan 1Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Yukara: Epos of The AinusDocument46 pagesYukara: Epos of The AinusAeowen Tene Serwaa SaitoNo ratings yet

- Origuchi Shinobu's MarebitoronDocument31 pagesOriguchi Shinobu's MarebitoronKeane RazielNo ratings yet

- Kitsune With InariDocument2 pagesKitsune With InariBruno ChevalleyNo ratings yet

- Phi (Osophical: Reseanch Soci - EtyDocument4 pagesPhi (Osophical: Reseanch Soci - EtyRodrigo Ramon RecaldeNo ratings yet

- Did Christ Visit JapanDocument25 pagesDid Christ Visit JapanRyan ChaddockNo ratings yet

- Omni System - Ronin (OEF) (05-2006)Document180 pagesOmni System - Ronin (OEF) (05-2006)G MNo ratings yet

- Edlit 102Document4 pagesEdlit 102Mapple SchuylerNo ratings yet

- Cu 31924014202687Document270 pagesCu 31924014202687Ioan CretaNo ratings yet

- Japanese Literature: Prepared By: BARROZO, RICA MAE DDocument9 pagesJapanese Literature: Prepared By: BARROZO, RICA MAE DRica Mae BarrozoNo ratings yet

- Japan's World Heritage Sites: Unique Culture, Unique NatureFrom EverandJapan's World Heritage Sites: Unique Culture, Unique NatureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange ThingsFrom EverandKwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange ThingsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (142)

- Shintothewayofgo00asto 0Document412 pagesShintothewayofgo00asto 0Maria RoaNo ratings yet

- Legendinjapanese00joly 1Document730 pagesLegendinjapanese00joly 1Vicente HayaNo ratings yet

- Kwai DanDocument267 pagesKwai DanIH InanNo ratings yet

- Fairy Tales From Far Japan by Susan BallardDocument140 pagesFairy Tales From Far Japan by Susan Ballardardeegee100% (8)

- Sacred Mountains: Fuji: Japan's Sacred SummitDocument2 pagesSacred Mountains: Fuji: Japan's Sacred SummitSon PhamNo ratings yet

- Sacred Mountains: Fuji: Japan's Sacred SummitDocument2 pagesSacred Mountains: Fuji: Japan's Sacred SummitSon PhamNo ratings yet

- ShakushainDocument30 pagesShakushainJosé manuel BlancoNo ratings yet

- F - Fison, Lorimer - Tales From Old Fiji (1904)Document276 pagesF - Fison, Lorimer - Tales From Old Fiji (1904)Christian IrigarayNo ratings yet

- A Brief Account of The Catfish As A Cultural Symbol in JapanDocument8 pagesA Brief Account of The Catfish As A Cultural Symbol in Japanardeegee100% (1)

- Ryokan Origins and History PDFDocument1 pageRyokan Origins and History PDFinsightsxNo ratings yet

- Blind Biwa PlayersDocument17 pagesBlind Biwa PlayersPauras PARCNo ratings yet

- (1902) Mythological Japan - Alexander F. Otto and Theodore S. HolbrookDocument86 pages(1902) Mythological Japan - Alexander F. Otto and Theodore S. HolbrookSamurai_Chef100% (1)

- Komatsu Kazuhiko - Bstudies On Izanagi-Ryū: A Historical Survey of Izanagi-Ryū Tayū (Hayashi Review)Document4 pagesKomatsu Kazuhiko - Bstudies On Izanagi-Ryū: A Historical Survey of Izanagi-Ryū Tayū (Hayashi Review)a308No ratings yet

- Japanese Journals PDFDocument7 pagesJapanese Journals PDFhnif2009No ratings yet

- A5 Gerry ZhuDocument3 pagesA5 Gerry Zhuapi-462999990No ratings yet

- Introduction To Japanese Archaeology: A Quick Tour of The Jomon, Yayoi and Kofun PeriodsDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Japanese Archaeology: A Quick Tour of The Jomon, Yayoi and Kofun PeriodselisabettaNo ratings yet

- Araki 1978. Yuriwaka and Ulysses. The Homeric Epics at The Court of Ouchi Yoshitaka'Document37 pagesAraki 1978. Yuriwaka and Ulysses. The Homeric Epics at The Court of Ouchi Yoshitaka'Emiel NachtegaelNo ratings yet

- L4 U01 La RCDocument3 pagesL4 U01 La RCDana TanasescuNo ratings yet

- Paper - Mobilizing Death in Imperial Japan War and The Origins of The Myth of Yasukuni Akiko TakenakaDocument15 pagesPaper - Mobilizing Death in Imperial Japan War and The Origins of The Myth of Yasukuni Akiko TakenakaAyana Hanashiro de MoraesNo ratings yet

- Nishimura 1985Document13 pagesNishimura 1985groot marvelNo ratings yet

- Shintoism: Ancient Wisdom To Modern SensibilitiesDocument25 pagesShintoism: Ancient Wisdom To Modern SensibilitiesKeeley RatherNo ratings yet

- Article-How People MoveDocument22 pagesArticle-How People MoveCik BedahNo ratings yet

- Maringer1974 2Document12 pagesMaringer1974 2MariaNo ratings yet

- CH 12 Sec 4 - Feudal Powers in JapanDocument5 pagesCH 12 Sec 4 - Feudal Powers in JapanMrEHsiehNo ratings yet

- Wolves or People' Lupine Loss and The Liquidation of The Nuclear Family in Mamoru Hosoda's Wolf Children (2012)Document34 pagesWolves or People' Lupine Loss and The Liquidation of The Nuclear Family in Mamoru Hosoda's Wolf Children (2012)aisyahNo ratings yet

- JimusakuDocument13 pagesJimusakustradivariusNo ratings yet

- Japanese Folklore - WikipediaDocument9 pagesJapanese Folklore - WikipediaTesteryioNo ratings yet

- HUDSON, Mark - Rice, Bronze, and Chieftains An Archaeology of Yayoi Ritual (1992)Document51 pagesHUDSON, Mark - Rice, Bronze, and Chieftains An Archaeology of Yayoi Ritual (1992)rafael93duarteNo ratings yet

- The Metamorphosis of The KappaDocument24 pagesThe Metamorphosis of The Kappaardeegee100% (5)

- 6.saigjo KeeneDocument3 pages6.saigjo KeenestefanNo ratings yet

- Prostitute As Bodhisattva-The Eguchi Theme in Ukiyo-EDocument19 pagesProstitute As Bodhisattva-The Eguchi Theme in Ukiyo-EMaria Fernanda100% (1)

- Flang2 Midterm (Jude Lunar)Document3 pagesFlang2 Midterm (Jude Lunar)Kim DimaanoNo ratings yet

- The Matayoshi Family and Kingai-RyuDocument8 pagesThe Matayoshi Family and Kingai-RyuJohnNo ratings yet

- Origin Myths Susano-O Orikuchi Shinobu and The Imagination ofDocument33 pagesOrigin Myths Susano-O Orikuchi Shinobu and The Imagination ofRenee E.No ratings yet

- Saito 1985Document13 pagesSaito 1985Laura Elizia HaubertNo ratings yet

- Victimage in The Kojiki of Japan: FragmentsDocument133 pagesVictimage in The Kojiki of Japan: FragmentsThe Lintons' Video Press67% (3)

- Dojoji Noh Play PDFDocument35 pagesDojoji Noh Play PDFkunstart. JJ.No ratings yet

- Ufo Remnants Discovery in AklanDocument4 pagesUfo Remnants Discovery in AklanLuisito PaduaNo ratings yet

- Kwaidan (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Stories and Studies of Strange ThingsFrom EverandKwaidan (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Stories and Studies of Strange ThingsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (144)

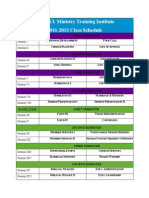

- AZUSA MTI Class Schedule For Blocks 3&4Document1 pageAZUSA MTI Class Schedule For Blocks 3&4AZUSA World Ministries Ministry Training InstituteNo ratings yet

- Quit India Speech Analisys - Final Draft PDFDocument6 pagesQuit India Speech Analisys - Final Draft PDFJunior Andres Rojas BustosNo ratings yet

- JFK in SpeechDocument4 pagesJFK in SpeechatNo ratings yet

- Divisions of VedasDocument4 pagesDivisions of VedasMp SunilNo ratings yet

- JH - Ecampusupload - Subjectnote - STD 6 - History - Early Vedic Civilization - NotesDocument4 pagesJH - Ecampusupload - Subjectnote - STD 6 - History - Early Vedic Civilization - NotesShubhanshu JoshiNo ratings yet

- PushpanjaliDocument2 pagesPushpanjaliTishya MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Recruitment/ Hiring/ Selection Through Islamic Point of ViewDocument19 pagesRecruitment/ Hiring/ Selection Through Islamic Point of ViewNafiz Jawad Talukder 19350200600% (1)

- Interesting Stories From Ramayan: For More Children Stories/Poems, Visit BlogDocument61 pagesInteresting Stories From Ramayan: For More Children Stories/Poems, Visit BlogJigneshShahNo ratings yet

- Stepping Up: A Call To Courageous Manhood ExcerptDocument50 pagesStepping Up: A Call To Courageous Manhood ExcerptJoy Robinson Roark83% (6)

- India State Polls 12 Holi Special 16-33 Fashion 40 Spiritual Awareness 44Document46 pagesIndia State Polls 12 Holi Special 16-33 Fashion 40 Spiritual Awareness 44Thesouthasian TimesNo ratings yet

- Ibn Al-Haytham - The First ScientistDocument3 pagesIbn Al-Haytham - The First ScientistDhantel Rhesa PrawedhaNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography (2/6/15)Document21 pagesAnnotated Bibliography (2/6/15)yeahbaby524No ratings yet

- Vippassana Meditation Retreat by Mya Sein Taung Taw Ya SayadawDocument3 pagesVippassana Meditation Retreat by Mya Sein Taung Taw Ya SayadawmyochitmyanmarNo ratings yet

- Journal of Islamic MarketingDocument14 pagesJournal of Islamic MarketingSoel Rock PerdozNo ratings yet

- God Defined Marriage: Theology of Sex (Washington, DC: National Association of Evangelicals, 2012), 10Document1 pageGod Defined Marriage: Theology of Sex (Washington, DC: National Association of Evangelicals, 2012), 10Silva SilvaNo ratings yet

- Fenomena Api Di Dasar LautanDocument17 pagesFenomena Api Di Dasar LautanFatasyaa AuliaNo ratings yet

- 40 Hours Adoration PrayersDocument4 pages40 Hours Adoration Prayersamadbest16No ratings yet

- Andres Robles A.P. World History P.2 Western Europe During The Middle Ages AachenDocument4 pagesAndres Robles A.P. World History P.2 Western Europe During The Middle Ages AachenAndrees RoblesNo ratings yet

- Added Branch OutDocument1,167 pagesAdded Branch OutGreen ValleyNo ratings yet

- Key Concepts in Anthropology, Ethnocentrism and Cultural RelativismDocument3 pagesKey Concepts in Anthropology, Ethnocentrism and Cultural RelativismEman ElNo ratings yet

- Why Do We Fast - Pastor Muyiwa OlubowaleDocument2 pagesWhy Do We Fast - Pastor Muyiwa Olubowaleapi-200727801No ratings yet

- Lal - Historicizing The Harem - The Challenge of A Princess S Memoir - 2004Document28 pagesLal - Historicizing The Harem - The Challenge of A Princess S Memoir - 2004Anonymous tChsoGok1No ratings yet

- HanoveriansDocument9 pagesHanoveriansFiametta RuiuNo ratings yet

- An Act of Entrustment of The Home To Mary Help of ChristiansDocument2 pagesAn Act of Entrustment of The Home To Mary Help of ChristiansDenmar BalbonaNo ratings yet

- Hermeneutics The 24 PrinciplesDocument25 pagesHermeneutics The 24 PrinciplesYaj EstefanoNo ratings yet

- Sacrament of Initiation BaptismDocument16 pagesSacrament of Initiation BaptismLei PaghinayanNo ratings yet

- The Genetic Code and The Book of LifeDocument26 pagesThe Genetic Code and The Book of Lifeapi-3814641No ratings yet

- History of RevivalDocument20 pagesHistory of RevivalIrene McGough100% (3)