Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SSRN Id3572102

SSRN Id3572102

Uploaded by

Marko SrdanovićCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Evidence Project (Facts Otherwise Not Relevant Become Relevant)Document6 pagesEvidence Project (Facts Otherwise Not Relevant Become Relevant)Ayushi JaryalNo ratings yet

- Evidence Part IDocument10 pagesEvidence Part IVitz IgotNo ratings yet

- Improper Evidence Non Jury Trials PDFDocument10 pagesImproper Evidence Non Jury Trials PDFMohit JainNo ratings yet

- Case NoteDocument6 pagesCase NoteJepter LordeNo ratings yet

- Kozinski Preface PDFDocument42 pagesKozinski Preface PDFphoenix92xNo ratings yet

- Litigation NotesDocument138 pagesLitigation NotesEnrique SanchezNo ratings yet

- 2023 NJC Mock Trial Case - CO HighlightingDocument63 pages2023 NJC Mock Trial Case - CO Highlightingslowmo slowmoNo ratings yet

- United States v. Peter Nick Thoma, 713 F.2d 604, 10th Cir. (1983)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Peter Nick Thoma, 713 F.2d 604, 10th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Patrick Leon O'Bryant, 42 F.3d 1407, 10th Cir. (1994)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Patrick Leon O'Bryant, 42 F.3d 1407, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Evidence Outline - ClarkDocument54 pagesEvidence Outline - Clarketphonehome331No ratings yet

- United States v. Orlando Gutierrez Acosta, 369 F.2d 41, 4th Cir. (1967)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Orlando Gutierrez Acosta, 369 F.2d 41, 4th Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Robert Marlin Slater, 692 F.2d 107, 10th Cir. (1982)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Robert Marlin Slater, 692 F.2d 107, 10th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Tillman Randolph Cunningham, 638 F.2d 696, 4th Cir. (1981)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Tillman Randolph Cunningham, 638 F.2d 696, 4th Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- R. v. Valentine, (2009) O.J. No. 5961Document11 pagesR. v. Valentine, (2009) O.J. No. 5961Jordan WeiszNo ratings yet

- Malcolm Rent Johnson v. Oklahoma, 484 U.S. 878 (1987)Document5 pagesMalcolm Rent Johnson v. Oklahoma, 484 U.S. 878 (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- School of Law University of California, Davis: UC Davis Legal Studies Research Paper SeriesDocument37 pagesSchool of Law University of California, Davis: UC Davis Legal Studies Research Paper SeriesZigor PelaezNo ratings yet

- RL 0110Document24 pagesRL 0110Mosa MasiloNo ratings yet

- Ronald C. Taylor, Cross-Appellee v. Coors Biotech Products Company, Cross-Appellant, 951 F.2d 1260, 10th Cir. (1991)Document5 pagesRonald C. Taylor, Cross-Appellee v. Coors Biotech Products Company, Cross-Appellant, 951 F.2d 1260, 10th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Attorneys For Appellants Attorneys For AppellantsDocument12 pagesAttorneys For Appellants Attorneys For AppellantsEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Charles Flynn v. Terrance Holbrook, 749 F.2d 961, 1st Cir. (1984)Document10 pagesCharles Flynn v. Terrance Holbrook, 749 F.2d 961, 1st Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. John W. Downing, 753 F.2d 1224, 3rd Cir. (1985)Document30 pagesUnited States v. John W. Downing, 753 F.2d 1224, 3rd Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Brien, 59 F.3d 274, 1st Cir. (1995)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Brien, 59 F.3d 274, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Angel Rios Ruiz, A/K/A Junior Rios, 579 F.2d 670, 1st Cir. (1978)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Angel Rios Ruiz, A/K/A Junior Rios, 579 F.2d 670, 1st Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ronald W.jordan, 466 F.2d 99, 4th Cir. (1972)Document14 pagesUnited States v. Ronald W.jordan, 466 F.2d 99, 4th Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Wilfred Johnson, 343 F.2d 5, 2d Cir. (1965)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Wilfred Johnson, 343 F.2d 5, 2d Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Amicus Petition NACDLDocument18 pagesAmicus Petition NACDLRick ArmbrustNo ratings yet

- Hugh J. Addonizio v. United States, 405 U.S. 936 (1972)Document7 pagesHugh J. Addonizio v. United States, 405 U.S. 936 (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Joe Delores Gomez, 603 F.2d 147, 10th Cir. (1979)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Joe Delores Gomez, 603 F.2d 147, 10th Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Donald Lee Schnoor v. C. E. Linkiewicz, Carl W. Larson, First State Bank of Calumet City and Wally Troyan, 397 F.2d 480, 1st Cir. (1968)Document5 pagesDonald Lee Schnoor v. C. E. Linkiewicz, Carl W. Larson, First State Bank of Calumet City and Wally Troyan, 397 F.2d 480, 1st Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Samuel Banks, 942 F.2d 1576, 11th Cir. (1991)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Samuel Banks, 942 F.2d 1576, 11th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- William L. Tippens, Deceased, Nell P. Tippens, Individually and As Widow of William L. Tippens v. The Celotex Corporation, 805 F.2d 949, 11th Cir. (1986)Document10 pagesWilliam L. Tippens, Deceased, Nell P. Tippens, Individually and As Widow of William L. Tippens v. The Celotex Corporation, 805 F.2d 949, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Assignment3 - Civprsat1-6 - (Ay18-19) - Pastor, Gee, A 1. Discuss The Concept of Newly Discovered Evidence Using American JurisprudenceDocument9 pagesAssignment3 - Civprsat1-6 - (Ay18-19) - Pastor, Gee, A 1. Discuss The Concept of Newly Discovered Evidence Using American JurisprudenceGeeAgayamPastorNo ratings yet

- Keeping Cross-Examination Under ControlDocument37 pagesKeeping Cross-Examination Under ControlFrancis ArvyNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Group v2Document12 pagesLegal Ethics Group v2Indomitable RakoNo ratings yet

- United States v. Rosenberg, 195 F.2d 583, 2d Cir. (1952)Document35 pagesUnited States v. Rosenberg, 195 F.2d 583, 2d Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Improper Use of Presumptions in RecentDocument41 pagesThe Improper Use of Presumptions in Recentromadz.coNo ratings yet

- United States v. Timothy M. Dwyer, 843 F.2d 60, 1st Cir. (1988)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Timothy M. Dwyer, 843 F.2d 60, 1st Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Alfred L. Hodges, JR., 524 F.2d 568, 1st Cir. (1975)Document5 pagesIn Re Alfred L. Hodges, JR., 524 F.2d 568, 1st Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nos. 13180-13183, 281 F.2d 581, 3rd Cir. (1960)Document13 pagesNos. 13180-13183, 281 F.2d 581, 3rd Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Richard Roe, Inc., and John Doe, Inc. United States of America v. Richard Roe, Inc., Richard Roe, John Doe, Inc., and John Doe, 68 F.3d 38, 2d Cir. (1995)Document5 pagesIn Re Richard Roe, Inc., and John Doe, Inc. United States of America v. Richard Roe, Inc., Richard Roe, John Doe, Inc., and John Doe, 68 F.3d 38, 2d Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id2311210Document33 pagesSSRN Id2311210mazuzaNo ratings yet

- Nos. 13180-13183. United States Court of Appeals Third Circuit, 281 F.2d 581, 3rd Cir. (1960)Document12 pagesNos. 13180-13183. United States Court of Appeals Third Circuit, 281 F.2d 581, 3rd Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Anthony Joseph Russo, JR., and Daniel Ellsberg v. William Matthew Byrne, JR., Etc, 409 U.S. 1013 (1972)Document4 pagesAnthony Joseph Russo, JR., and Daniel Ellsberg v. William Matthew Byrne, JR., Etc, 409 U.S. 1013 (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henry J. Wright, JR., 573 F.2d 681, 1st Cir. (1978)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Henry J. Wright, JR., 573 F.2d 681, 1st Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument10 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Heineman, 10th Cir. (2014)Document32 pagesUnited States v. Heineman, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Merkuri Stanback, 11th Cir. (2011)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Merkuri Stanback, 11th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States of America, Plaintiff-Respondent v. Peter Lubertazzi, 283 F.2d 152, 3rd Cir. (1960)Document5 pagesUnited States of America, Plaintiff-Respondent v. Peter Lubertazzi, 283 F.2d 152, 3rd Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- TLI Textbook Part 1Document98 pagesTLI Textbook Part 1he yNo ratings yet

- United States v. John Humphrey Sullivan, 329 F.2d 755, 2d Cir. (1964)Document3 pagesUnited States v. John Humphrey Sullivan, 329 F.2d 755, 2d Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Albert Junior Holley, 502 F.2d 273, 4th Cir. (1974)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Albert Junior Holley, 502 F.2d 273, 4th Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. George N. Collatos, 798 F.2d 18, 1st Cir. (1986)Document5 pagesUnited States v. George N. Collatos, 798 F.2d 18, 1st Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Face-Coverings, Demeanour Evidence and The Right To A Fair Trial Lessons From The USA and CanadaDocument19 pagesFace-Coverings, Demeanour Evidence and The Right To A Fair Trial Lessons From The USA and CanadaKen MutumaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kenneth L. Brown, 615 F.2d 1020, 4th Cir. (1980)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Kenneth L. Brown, 615 F.2d 1020, 4th Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States of America Ex Rel. Albert B. Crosby v. Joseph R. Brierley, Superintendent, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 404 F.2d 790, 3rd Cir. (1968)Document17 pagesUnited States of America Ex Rel. Albert B. Crosby v. Joseph R. Brierley, Superintendent, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 404 F.2d 790, 3rd Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NSDS EVIDENCE101 A PRIMERONEVIDENCELAW 03jun141Document14 pagesNSDS EVIDENCE101 A PRIMERONEVIDENCELAW 03jun141wensislaus chimbaNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument12 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Compulsory Fingerprinting and The Self-Incrimination PrivilegeDocument5 pagesCompulsory Fingerprinting and The Self-Incrimination PrivilegeAnthonyNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Cyber Law NotesDocument23 pagesUnit 3 Cyber Law NotesAkash RajaNo ratings yet

- Stand Your Ground: TO KILL, OR NOT TO KILL The Legal Limits of SafetyFrom EverandStand Your Ground: TO KILL, OR NOT TO KILL The Legal Limits of SafetyNo ratings yet

- editor-66-560-564Document5 pageseditor-66-560-564Marko SrdanovićNo ratings yet

- Ubc - 1985 - A8 C88Document135 pagesUbc - 1985 - A8 C88Marko SrdanovićNo ratings yet

- Fordham Intl. L. J. - UnlockedDocument23 pagesFordham Intl. L. J. - UnlockedMarko SrdanovićNo ratings yet

- Eu Gender Action Plan 2016-2020 at Year one-QA0217807ENNDocument88 pagesEu Gender Action Plan 2016-2020 at Year one-QA0217807ENNMarko SrdanovićNo ratings yet

- Diktat - Peti AmandmanDocument25 pagesDiktat - Peti AmandmanMarko SrdanovićNo ratings yet

- Defining Transport Logistics: A Literature Review and Practitioner Opinion Based ApproachDocument9 pagesDefining Transport Logistics: A Literature Review and Practitioner Opinion Based ApproachMarko SrdanovićNo ratings yet

- Delivery Volume OptimizationDocument15 pagesDelivery Volume OptimizationMarko SrdanovićNo ratings yet

- Domingo-2017-SSRN Electronic JournalDocument29 pagesDomingo-2017-SSRN Electronic JournalMarko SrdanovićNo ratings yet

- Vasan Singh v. PPDocument5 pagesVasan Singh v. PPAishah MunawarahNo ratings yet

- Alibi Notes On Criminal Procedure CodeDocument11 pagesAlibi Notes On Criminal Procedure CodeNur AqilahNo ratings yet

- Law of Evidence Project: Topic - Plea of AlibiDocument15 pagesLaw of Evidence Project: Topic - Plea of AlibiJin KnoxvilleNo ratings yet

- Olatinwo V State S.CDocument32 pagesOlatinwo V State S.CGoodhopeNo ratings yet

- Evidence LawDocument12 pagesEvidence LawAnvesha ChaturvdiNo ratings yet

- Plea of Alibi and Its EssentialsDocument3 pagesPlea of Alibi and Its EssentialsIkra MalikNo ratings yet

- Esqueda vs. People - DigestDocument1 pageEsqueda vs. People - DigestJustine Dawn Garcia Santos-TimpacNo ratings yet

- Plea of AlibiDocument3 pagesPlea of AlibiIkra Malik100% (1)

- Indian Evidencr ActDocument4 pagesIndian Evidencr ActIkra MalikNo ratings yet

- Memo - Appellant EvidenceDocument14 pagesMemo - Appellant EvidenceYogita Singh RathoreNo ratings yet

- AlibiDocument4 pagesAlibimuhammad wafiNo ratings yet

- Nunavuumi Iqkaqtuijikkut La Cour de Justice Du NunavutDocument15 pagesNunavuumi Iqkaqtuijikkut La Cour de Justice Du NunavutNunatsiaqNewsNo ratings yet

- (2018) Myca 117 - 10215Document16 pages(2018) Myca 117 - 10215Amirhamd100% (1)

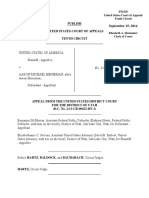

SSRN Id3572102

SSRN Id3572102

Uploaded by

Marko SrdanovićOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SSRN Id3572102

SSRN Id3572102

Uploaded by

Marko SrdanovićCopyright:

Available Formats

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

INVESTIGATING AND PRESENTING AN ALIBI

DEFENSE

by Lisa J. Steele1

Alibis always sound so delightfully healthy, but they crack-up

dreadfully easily. . . Whatever the truth about his defence, Dave Anstey

it seemed had total faith in it. As for me, I'm not sure that I like cast

iron alibis. They're the sort that sink quickest, to the bottom of the sea.

Horace Rumpole (attorney), Mortimer, THE TRIALS OF RUMPOLE (1979)

The New Jersey Supreme Court has said that “few defenses have greater

potential for creating reasonable doubt as to a defendant's guilt in the minds of the

[jurors than an alibi].”2 But is alibi a powerful defense, or a risky gambit with a

high likelihood of backfiring?

Courts and prosecutors contend that alibis are easy to manufacture and

effective defenses.3 “Alibi”, some court suggest “has long been considered as one of

the main avenues of escape of the guilty”.4 Other courts refer to it as a “‘hip pocket’

defense because of the ease with which it can be manufactured for introduction in

1

Practicing Attorney in Connecticut and Massachusetts.

2

(internal quotation marks omitted) State v. Porter, 216 N.J. 343, 353, 80

A.3d 732 (2013).

3

See Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78, 81 (1970).

4

See Alicea v. Gagnon, 675 F.2d 913, 916 (7 th Cir. 1982); State v. Davis, 624

P.2d 376, 379 (Haw. 1981) (both quoting from Millar, The Modernization of

Criminal Procedure, 11 J.CRIM.L. & C. 344, 350 (1920)).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

the final hours of the trial.”5 Concerns about easy fabrication underlie notice of alibi

rules (such as Fed.R. Crim.P. 12.1) found in many jurisdictions.

Defense attorneys, on the other hand, frequently decline to offer alibi

witnesses out of concerns that the jury will reject the defense after the prosecutor’s

clever cross-examination and summation, leading to the defendant’s conviction.

Appellate dockets frequently contain post-conviction cases arguing that trial

counsel was ineffective for not investigating or not presenting alibi witnesses6 –

these claims are rarely successful. Commentators warn defense counsel to “exercise

extreme caution” in choosing alibi witneses and “take pains” to ensure that the alibi

5

State v. Davis, 624 P.2d 376, 379 (Haw. 1981) (“hip pocket” was first

mentioned in Stassen, The Show Window of the Bar, 20 MINN. L. REV. 577, 580-81

(1935)).

6

See e.g. Johnson v. Commissioner, 330 Conn. 520, 544 n. 4, 198 A.3d 52

(2019) where trial counsel said:

My belief about alibis is that unless they are solid, they can get you

into trouble. It's the last thing the jury hears if you have a good

prosecutor who's a good cross-examiner and can try to kind of attack

either a family member who's an alibi witness or some other

vulnerability to the alibi. To me, it pulls attention away from the

weaknesses in the state's case, and it kind of develops jurors' focus on

the weaknesses in the alibi. So, it's just been my practice to shy away

from alibis unless they're solid, and I had some concerns about the

alibi in this case.

and Outing v. Commissioner, 190 Conn. App. 510, 522, 211 A.3d 1053 (2019) where

trial counsel “testified that she had ultimately concluded, on the basis of her

experience as a trial attorney, that the presentation of an incomplete alibi defense,

bolstered only by friends and relatives of the accused, often undermines the

defendant's defense in a murder trial.”

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

witness’ testimony is consistent with other defense witnesses.7

So who’s right? Is an alibi defense the key to the jailhouse door, or a

millstone? The DNA exoneration cases suggest the latter. In about two-thirds (68%)

of the DNA exoneration cases, the innocent defendants offered an alibi which was

not believed by law enforcement; worse, weak alibis were used by prosecutors as

incriminating evidence at trial.8 Fact-finders, it seems, underbelieve alibi witnesses.

Defense counsel’s concerns seem validated – courts fears seem overstated. Yes, an

alibi can be fabricated – but so can almost all other testimony. Deciding whether an

alibi witness is accurate and truthful is hard – it is easy for a suspect to make a

good-faith error about where he was when first confronted by police, and easy for

potential alibi witnesses to make good-faith errors about the details of what was, for

them, an everyday event.

Does defense counsel then abandon alibis unless they are complete and

7

Sullivan, Presentation of the Defense, 62:2 J. CRIM. L, CRIMINOLOGY & POLICE

SCI. 153, 160 (1971). See Skakel v. Commissioner, 329 Conn. 1, 64, 188 A.3d 1

(2018) (Skakel). (“[there is nothing as dangerous as a poorly investigated alibi. An

attorney who is not thoroughly prepared does a disservice to his client and runs the

risk of having his client convicted even [when] the prosecution's case is weak”)

8

See Culter, CONVICTION OF THE INNOCENT 239-40 (2012); Garrett,

CONVICTING THE INNOCENT 156-57 (2011); Crozier, Strange, & Loftus, Memory

Errors in Alibi Generation: How an Alibi can Turn Against Us, 35:1 BEHAV. SCI. &

L. 6 (2017); Dysart & Strange, Beliefs about Alibis and Alibi Investigations: A

Survey of Law Enforcement, 18:1 PYSCH., CRIME & L. 11, 11-12 (2012); Olson &

Wells, What Makes a Good Alibi? A Proposed Taxonomy, 28:2 L. & HUM. BEHAV.

157, 157-58 (2004).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

unequivocal, based on strangers, and supported by physical evidence? The question

falls largely on defense counsel because alibi is a reaction to the prosecution.

Defense counsel investigates alibi witnesses and looks for confirming evidence.

Counsel decides whether to offer an alibi defense, giving appropriate notice, and

chooses what witnesses to present and how. Investigators and prosecutors are

largely reactive – they follow-up on information provided by the defendant, and

challenge the defense witnesses at trial.

Insisting on only offering an alibi supported by physical evidence would mean

very few alibis would be offered. Alibis supported by strong physical evidence are

rare.9 Insisting on only offering an alibi supported by disinterested witnesses

ignores the risk that the witnesses who are most likely to be believed are also the

9

Culter, CONVICTION OF THE INNOCENT 240 (2012) (14% of alibis offered in survey of

American and Canadian cases were supported by physical evidence).

This may be changing. Cell phone location history, apps, and call records may

document a witness or defendant’s location at key times. Admittedly, these locate

the device, not who is holding it, but it may be persuasive corroboration even if not

absolute. Smart speakers and assistants that capture voices at critical times would

be harder to fabricate.

Litigation about geo-fencing warrants (searches of past location history) is

still in its infancy. See Valentino-DeVries, Tracking Phones, Google is a Dragnet for

the Police, N.Y. TIMES (4/13/19) available at:

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/13/us/google-location-tracking-police.h

tml ; Schuppe, Police used Google Location Data to find an Accused Bank Robber. He

says That’s Illegal, ABC NEWS (11/20/19) available at:

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/police-used-google-location-data-find-accus

ed-bank-robber-he-n1086836

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

most likely to forget having seen the defendant.10

So what can defense counsel do? Basic research about perception, memory,

and good-faith error should be familiar to attorneys and judges from eyewitness

identification research and case law.11 There is also more specific research available

the psychology of alibis.12 Understanding what one can realistically ask of alibi

witnesses, and communicating that research to fact-finders may lead to a more

accurate assessment of alibi defenses and a decrease in convictions of innocent

defendants.

Where Were you that Night? – The Suspect and the Initial

Questioning

My heart started pounding . . . I had gotten my weekends confused.

Which meant the alibi I gave to the police was not going to check out at

all.

Ronald Cotton (exonerated defendant), Thompson-Cannio, Cotton &

Toreno, PICKING COTTON: OUR MEMOIR OF INJUSTICE AND REDEMPTION

86 (2009)

10

Charman, et al., The (Un)reliability of Alibi Corroborators: Failure to

Recognize faces of Briefly Encountered Strangers Puts Innocent Suspects at Risk,

35:1 BEHAV. SCI. L. 16 (2017).

11

See generally 2019 Report of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Third Circuit Task Force on Eyewitness Identification, 92 TEMPLE L. REV. 1 (2019).

12

This is a new field of research. A 2017 literature search of the term ‘alibi' on

Web of Science generated “three hits for 1988–1997, 11 for 1998–2007, and 43 for

2008–present day. As a comparison, close to 2,500 and 3,000 hits are returned for

the terms ‘eyewitness' and ‘deception', respectively (1988–2017).” Sauerland, Alibis:

Generation, Consistency, Corroboration, Believability, and Detection – Introduction

to this Special Issue, 35:1 BEHAV. SCI. L 3 (2017).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

An innocent suspect may first learn that he or she needs an alibi when first

questioned by police. Questioning may occur soon after the crime, when the

suspect’s memory of where he or she was should be fresh. But it may also occur

days, weeks, or months later. The innocent suspect’s memory of his or her

whereabouts on a past date and time that had no significance until that moment

may be wrong – but a good faith mistake may be interpreted as a deliberate lie.

The Reid Method cautions that where a suspect has an alibi “it is imperative

that the alibi be checked, if at all possible, before the interrogation begins.”13 If the

alibi is defective, it will help the questioner. If not, it “may actually establish the

innocence of the suspect, despite other circumstances that may point to his guilt.”14

The manual suggests open-ended questions to elicit an alibi, like “please tell me

everything you did from noon on Friday until you went to bed”.15 If the suspect gives

a general alibi, like I was driving alone in my car that night, then the manual

suggests asking for details about the route the suspect drove, places he visited, and

approximate times of arrival and departure at any place he went.16 Doing this may,

13

Inbau, et al., CRIMINAL INTERROGATION AND CONFESSIONS 18 (5th Ed. 2013)

14

Id.

15

Id. at 86, 156, 444. The manual suggests that “[i]nformation that is volunteered during a

response to an open question – for example – a subject’s alibi – will probably all be truthful,

although perhaps incomplete.” and then gives an example of a truthful answer implying an alibi,

but not actually committing to it. Id. at 86-87.

16

Id. at 175.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

the manual suggests, show gaps in the witness’ story or provide details that could

be tested. To test an alibi, the manual suggests:

! asking the witness about a fictional event, like a car accident, that

supposedly happened at the time and place mentions to see if the

suspect will believe the false event is true and add it to his story;17

and/or

! asking the witness for a detailed description of his activities and then

to recount the alibi in reverse chronological order.18

In practice, observers have noted that if a suspect offers an alibi “the interrogator

will attack it as inconsistent, contradicted by all of the case evidence, implausible,

and/or simply impossible – even if none of these assertions are true.”19

Innocent suspects are more likely to waive their Miranda rights and talk to

investigators. They believe, wrongly, that their innocence will be obvious to the

investigators.20 An innocent suspect may have no experience with a serious felony

17

Id. at 175-76. (The authors assume that the suspect has a clear memory of the evening

and “there would be no delay” in saying that the event didn’t happen. Id. at 76.)

18

Id. at 180. (“A person who has related a truthful account”, it posits, “will have little

difficulty doing this, because their memories are based on factual occurrences.” Id.)

19

Drizen & Leo, The Problem of False Confession in the Post-DNA World, 82 N.C. L.

REV. 891, 915 (2004).

20

Kassin & Norwick, Why People Waive their Miranda Rights: The Power of

Innocence, 28 L. & HUM. BEHAV. 211 (2004); Savitsky & Gilovich, The Illusion of

Transparency and the Alleviation of Speech Anxiety, 39 J. EXP. SOC. PSYCH. 618

(2003). Gilovich, Savitsky & Medvec, The Illusion of Transparency: Biased

Assessments of Others’ Ability to Read one’s Emotional States, 75 J. PERSONALITY &

SOC. PSYCH. 332 (1998); Vorauer & Claude, Perceived versus Actual Transparency of

Goals in Negotiation, 24 PERSONALITY & SOC. PSYCH. BULLTN. 371 (1998). See

Kassin, On the Psychology of Confessions: Does Innocence put Innocent at Risk?, 60

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

investigation, and is likely to be unfamiliar with techniques used by police to obtain

admissions and confessions.21 This may make the suspect more anxious to offer an

alibi without taking the time to verify it. Cotton, an innocent suspect arrested a few

days after Jennifer Thompson was sexually assaulted, confused his weekends and

gave police the wrong information about where he was.

This is not unusual. Innocent suspects may not accurately recall where they

were in the past. In one study, participants were asked to report their whereabouts

on four particular times in the past, then given 48 hours to return with evidence of

their whereabouts – in this low stress/low stakes test over 1/3 (36.4%) were wrong

about where they had been.22 If the suspect in the high stress/high stakes

interrogation room setting provides wrong information to law enforcement, officers

AM. PSYCH. 215 (2005). See also Scherr, Relich, & Kassin, Cumulative

Disadvantage: A Psychological Framework for Understanding how Innocence can

lead to Confession, Wrongful Conviction, and Beyond, PERSPECTIVES ON

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE (2020) (available at:

https://web.williams.edu/Psychology/Faculty/Kassin/files/Scherr%20Redlich%20Kas

sin%20(2020)%20-%20Cum%20Disadvant)

This same illusory aura of innocence may affect alibi witnesses, who expect

that the truth of their testimony will be obvious to investigators and may be

surprised when it is not.

21

See generally, Inbau et als, CRIMINAL INTERROGATION AND CONFESSION 150-

th

51 (5 Ed. 2013).

22

Olson & Charman, But Can You Prove it? Examining the Quality of Innocent

Suspects’ Alibis, 18:5 PSYCH., C & LAW 453, 459-64 (2012). See Culhane et al,

Generation and Detection of True and False Alibi Statements, 20:4 PSYCH., PSYCHOL.

& L. 619 (2013); Dysart & Strange, Beliefs about Alibis and Alibi Investigations: A

Survey of Law Enforcement, 18:1 PSYCH., CRIME & L. 11, 13 (2012).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

may see this as a deliberate lie and as evidence of guilt.23

Cotton, like other witnesses, may have relied on a schema to generate this

alibis – he recalled what he habitually did at that time on a weekend, rather than

recalling specifically what he did on that particular day.24 If he in fact did what he

usually did, the alibi would be reliable. If he did something different, and had

forgotten that he had deviated from his routine, then the alibi would be

inaccurate.25 When police are unable to verify it, the suspect looks guilty.

As noted above, acquaintances and strangers may not recall interacting with

the defendant. If the defendant overconfidently assumes that the witness will do so,

then he or she may suggest alibi witnesses who don’t recall them when contacted by

an investigator.26 If the alibi witness fails to remember the defendant when

23

Id. at 19; See Bowden, Interview and Interrogation: Breaking the Alibi

https://www.policeone.com/investigations/articles/interview-and-interrogation-break

ing-the-alibi-PrttCmxEQCm5Y3kb/ (Last Viewed 1/13/2020).

24

Lens & Charman, Schema Reliance and Innocent Alibi Generation, 21:1

LEGAL & CRIMINOLOGICAL PSYCH 111, 112 (2013). See Crozier, Strange, & Loftus,

Memory Errors in Alibi Generation: How an Alibi can Turn Against Us, 35:1 BEHAV.

SCI. & L. 6, 12 (2017).

25

Lens & Charman, Schema Reliance and Innocent Alibi Generation, 21:1

LEGAL & CRIMINOLOGICAL PSYCH 111, 112 (2013).

26

Charman, et al., The (Un)reliability of Alibi Corroborators: Failure to

Recognize faces of Briefly Encountered Strangers Puts Innocent Suspects at Risk,

35:1 BEHAV. SCI. L. 16, 21 (2017); see Gilovich, et al., The Spotlight Effect in Social

Judgement: An Egocentric Bias in Estimates of the Salience of one’s own Actions and

Appearance, 78 J. PERSONALITY & SOC. PYSCH., 211 (2000) (people overestimate the

extent to which others notice them). See also Yarmey, Eyewitness Recall and Photo

Identification: A Field Experiment, 10:1 PSYCHOL., CRIME & L. 53 (2004) (discussing relatively

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

questioned, then the investigator may assume that the defendant lied to them and

is guilty.27

The consequences of good-faith mistakes are serious. Once a defendant

makes a mistake, it may be near-impossible for them to convince anyone of their

innocence.28 (The one exception seems to be if the defendant lies, then provides a

salacious alibi.29) Changes, even changes that genuinely strengthen the alibi, tend

to weaken how fact-finders perceive it.30

If a suspect hesitates, however, wanting to think about where he or she was,

or to consult records, the prosecution may argue that the delay is a sign of

deception, not an attempt to be accurate. In Outing v. Commissioner, the defendant

was arrested four days after the shooting. Outing told police when he was arrested

that he did not recall where he was at the time of the murder.31 He provided police

poor witness performance identifying a person they briefly interacted with four hours earlier).

27

Id.

28

Olson & Charman, But Can You Prove it? Examining the Quality of Innocent

Suspects’ Alibis, 18:5 PSYCH., CRIME & LAW 453, 456 (2012).

29

See Nieuwkamp, et al., A Lie and a Mistress: On Increasing the Believability

of your Alibi, 23:5 PSYCH, PSYCHOL. & L. 733 (2016).

30

See Culhane & Horsch, Changed Alibis, Current Law Enforcement, Future

Law Enforcement, and Layperson Reactions, 39:7 CRIM. J. & BEHAV. 958, 974 (2012).

31

Outing at 522.

10

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

with a list of alibi witnesses the next morning.32 (He was incarcerated overnight –

there was no evidence that he’d had any contact with possible alibi witnesses before

providing the list to police.) Trial counsel believed that Outing’s inability to

immediately provide an alibi would undercut an alibi defense.33

Research on autobiographical memory suggests that people can respond

quickly to questions about their past whereabouts with general details, but have a

harder time recalling specific details.34 Had Outing’s attorney been more aware of

the limits of autobiographical memory, she may have been able to defend Outing’s

delay in naming his alibi witnesses, possibly with the aid of expert testimony.

Courts, like investigators, assume that innocent people should be able to

provide relatively strong and accurate alibis.35 This turns out to be untrue; most

people have trouble accurately recalling where they were in the past.36 In

Nieuwkamp’s study of over 800 volunteers drawn from the community, asked about

their whereabouts no more than a week earlier, 90% of subjects reported that they

32

Outing at 522.

33

Outing at 522.

34

Culhane et al, Generation and Detection of True and False Alibi Statements,

20:4 PSYCH., PSYCHOL. & L. 619, 620-21 (2013).

35

Olson & Charman, But Can You Prove it? Examining the Quality of Innocent

Suspects’ Alibis, 18:5 PSYCH., C & LAW 453, 464 (2012).

36

Nieuwkamp, Horselenberg & Van Koppen, The Illusion of the Perfect Alibi:

Estabishing Base Rate of Non-Offenders’ Alibis, 14 J. INVESTIG. PSYCH OFFENDER

PROFIL. 23 (2016) (Perfect Alibi).

11

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

could support their alibi with at least one witness – 65% could provide a motivated,

familiar person, 16% could provide an acquaintance or stranger.37 About 25% could

provide an item of physical evidence (typically a receipt); only 7% believed they

could find video recordings to support their claim.38 Alibis were weakest during the

times when a person was most likely to be at home, with friends, or at a movie and

strongest when the person was at work or in class.39 This study supports the general

proposition — the majority of a person’s time, especially at night, on weekends, and

during the holidays, is spent with friends and family – the weakest alibi

witnesses.40

In State v. Dickson,41 the defendant first learned he was a suspect in a

murder when he was arrested eighteen months after it occurred. His mother and

aunt repeatedly told police that he was with them at a sports bar on the night of the

murder and asked them to contact the bar to see if it still had video recordings to

prove Dickson’s alibi. Police did not contact the bar, which had a fire six months

after Dickson’s arrest. The Connecticut Supreme Court noted that “neither of the

37

Perfect Alibi at 30.

38

Perfect Alibi at 30.

39

Perfect Alibi at 30.

40

Culhane & Hosch, An Alibi Witness’ Influence on Mock Jurors’ Verdicts, 34:8

J. APP. SOC. PSYCH. 1604, 1606-07 (2004).

41

322 Conn. 410 (2016).

12

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

alibi witnesses testified unequivocally that the defendant had been in the sports bar

with his family at 9:30 p.m. on January 9, 2010, when the crime occurred.

Moreover, to the extent that the testimony of the defendant's mother and aunt

would support that conclusion, both witnesses had a clear motive to attempt to

convince the jury that the defendant was in the bar at that time.”42

What about strangers – would the bartender or wait staff have remembered

serving Dickson if asked a year and a half later? Unlikely. Unlike an eyewitness to

a crime, an alibi witness has no reason to realize when they interact with the

defendant that they will be asked to recall him or her later. The alibi witness may

have interacted with dozens of people during the critical time, and may not recall

which customers were there at that time.43

What about supporting physical evidence? Suspects provide leads or

references to physical alibi evidence in less than a quarter of criminal cases.44 In

Dickson, the defendant’s family believed that physical alibi evidence existed, but

police did not try to obtain it before it was lost in a fire at the bar. In a survey of

police officers, less than half (49.2%) said that a thorough investigation of an alibi is

42

Dickson at 459.

43

Charman, et al., The (Un)reliability of Alibi Corroborators: Failure to

Recognize faces of Briefly Encountered Strangers Puts Innocent Suspects at Risk,

35:1 BEHAV. SCI. L. 16, 19 (2017).

44

Dysart & Strange, Beliefs about Alibis and Alibi Investigations: A Survey of

Law Enforcement, 18:1 PSYCH., CRIME & L. 11, 19 (2012).

13

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

always conducted before an arrest warrant is prepared or the defendant arrested,

38.1% said it is often investigated; 7.9% said it is sometimes investigated; and 4.8%

said it is rarely or never investigated before the warrant is prepared or the

defendant is arrested.45 Telling the police about physical alibi evidence does not

mean that it will be pursued.46

Police and Prosecutor Questioning of an Alibi Witness

What happens when a suspect provides alibi witnesses to the police or

prosecution? One survey of 73 prosecutors found that all but one took advantage of

notice-of-alibi rules to make a pretrial investigation of alibi witnesses.47

Epstein theorized that pre-trial investigations would lead to dismissal if the alibi

proved true.48 Nineteen percent reported no cases dismissed after investigation;

45

Dysart & Strange, Beliefs about Alibis and Alibi Investigations: A Survey of

Law Enforcement, 18:1 PSYCH., CRIME & L. 11, 17 (2012).

46

If the police fail to follow up on alibi information, the defendant could

combine an alibi defense with a claim of an investigative failure or omission,

arguing that a jury that could find reasonable doubt if jurors conclude that "the

investigation was careless, incomplete, or so focused on the defendant that it

ignored leads that may have suggested other culprits." State v. Wright, 322 Conn.

270, 322, 140 A.3d 939 (2016) citing Commonwealth v. Silva-Santiago, 453 Mass.

782, 801, 906 N.E.2d 299 (2009). This may be especially important to counter jurors’

inherent belief that if a case makes it to trial, then there is a reason not to trust an

alibi witness – if police had believed the alibi, the case would not have progressed to

trial. Sommers & Douglass, Context Matters: Alibi Strength Varies According to

Evaluator Perspective, 12 LEGAL & CRIMINOLOGICAL PSYCHOL. 41 (2007).

47

Epstein, Advance Notice of Alibi, 55 J. CRIM. L. CRIMINOLOGY & POLICE SCI.

29, 31-32 (1964). This 55-year-old article is the only reported survey of prosecutors to date.

48

Id.

14

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

this includes a few respondents who said they would not dismiss the case, even if

they thought the alibi might be true, because credibility was for the jury.49 Over

half (58%) reported a few dismissals, 15% reported dismissals in half their cases;

and 8% said there were many dismissals.50 Epstein concluded that “[t]he fact that

comparatively few cases are dismissed as a result of pre-trial investigation is

entirely consistent with our notion of alibis – they are usually false.” (emphasis

original).

There is another possibility, perhaps unknown to Epstein in 1964 – tunnel

vision and investigative bias. If the police have arrested the suspect, they have

already formed a conclusion that he or she is guilty.51 Once prosecutors have filed

charges and begun to prepare their case, they have likewise concluded that the

defendant is guilty.52

49

Id.

50

Id.

51

See generally Rossmo, CRIMINAL INVESTIGATIVE FAILURES 282-83 (2009).

See also Garrett, CONVICTING THE INNOCENT 266 (2011) ("[w]hen police form a

hunch that a suspect is guilty, they may then without realizing it discount any

evidence that does not jibe with their prior belief in the suspect's guilt.")

52

See Findley & Scott, The Multiple Dimensions of Tunnel Vision in Criminal

Cases, 2 Wisc. L. Rev. 291, 329, 331 (2006) (the prosecutorial role “inevitably fosters

tunnel vision”, “ethical prosecutors feel a pressure to push hard to obtain

convictions, because only a conviction serves the interest of justice”)

Similar confirmation bias issues may affect judges considering the effect of

alibi witnesses on the strength of the prosecution’s case on appeal, and whether

trial counsel was ineffective for not pursuing or offering alibi witnesses in a habeas

case.

15

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

If the police or prosecutor are convinced that the defendant is guilty, then the

alibi witness must be either liars or wrong. Disbelieving investigators may subject

alibi witness to coercive interrogation methods, which may pressure witnesses to

retract or hedge the alibi.53 Police or prosecutors may threaten alibi witnesses with

prosecution for perjury or obstruction of justice.54 Accurate, truthful witnesses may

be intimidated and either hedge or retract their statements.

Even more subtle methods can lead witnesses to retract an accurate, truthful

alibi.55 Witnesses exposed to incriminating information may doubt their own

53

See Moore, et al, Shaping Eyewitness and Alibi Testimony with Coercive

Interview Practices, THE CHAMPION 34 (October, 2014) (coercive techniques used in

specific case lead to retraction from alibi witness).

54

See People v. Henne, 165 Ill.App.3d 315, 326 (1988) (police arrested alibi

witness and charged her with obstruction of justice; witness then hedged her

previous answers The court faulted the defense for not calling the alibi witness at

trial. “For all we know, she did not testify due to her susceptibility of impeachment

by her inconsistent statements, or was not called by the defendant for fear of her

truthful answers.”); People v. Chen, 256 A.D.2d 75, 682 N.Y.S.2d 145 (N.Y. 1998)

(prosecutor’s interview with alibi witness in which prosecutor explained the legal

consequences of perjury did not improperly intimidate the witness). But see People

v. Pena, 175 N.W.2d 767 (Mich. 1970) (improper for prosecutor to send alibi

witnesses a letter quoting the state’s perjury statute).

See generally Sali & Robb, Fighting Governmental Witness Tampering, THE

CHAMPION 34 (June 2017) (potential alibi witness might be told, for example, “that

the investigation is still open, the prosecution may ultimately bring charges against

additional suspects, and continuing to maintain that the defendant was somewhere

else sounds like the kind of thing an accomplice would say”).

55

See Marion, et al, Lost Proof of Innocence: The Impact of Confession on Alibi

Witnesses, 40:1 L & HUM. BEHAV. 65 (2016) (over half of witnesses retracted an alibi

when falsely told that an innocent confederate confessed).

16

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

memories or fear being seen as lying for the suspect and prosecuted, and soften or

retract an alibi.56 Both truthful and false alibi witnesses may not recognize or

respond when police test them with altered versions of earlier alibi statements.57

If counsel becomes aware of an alibi witness before a police or prosecutors

interview, counsel may want to take a statement to preserve the original alibi from

further contamination by suggestion, post-event information, and pressure.58 If

counsel first becomes aware of the alibi witness after a statement was given,

counsel should see if the interview was recorded and talk with the witness to see if

coercive tactics were used.

Why Didn’t You Go to the Police? – The Alibi Witness After

Arrest

56

Marion, et al, Lost Proof of Innocence: The Impact of Confession on Alibi

Witnesses, 40:1 L & HUM. BEHAV. 65, 66 (2016).

57

Saureland, et al., Deceiving Suspects about the Content of their Alibis:

Consequences for Truthful and Untruthful Suspects, 18:2 J. FORENSIC PRACTICE 143

(2016) (both truthful and false witnesses were largely blind to alteration sin their

alibi statements when interviewed a few days later, leading to the appearance of

inconsistency for both kinds of witnesses). See also Sauerland, Krix, and Sagana,

Deceiving Suspects about their Alibi is Equally Harmful to the Innocent and Guilty,

__ APP. COG. PSYCH. __ (2019) (similar study showed that untruthful witnesses were

slightly better than truthful witnesses at noticing alterations to their prior

statements; guilty suspects are not easier to mislead than innocent ones).

58

Sullivan, Presentation of the Defense, 62:2 J. CRIM. L, CRIMINOLOGY &

POLICE SCI. 153, 161, n. 62 (1971) warns that “[t]he subtle pressures that the

subsequent interview [by the police or prosecutor] may bring to bear on the witness

may disturb the certainty of the witness’s recollections and engender changed

testimony at trial.”

17

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

Unless I could break this guy's alibi a murderer might be walking on

the street. There was such a small window of opportunity, I had to act

fast.

– Prosecutor’s remark to the press, see Browning, Prosecutorial

Misconduct in the Digital Age, 77 ALB. L. REV. 881, 889 (2013-14).

Sometimes, alibi witnesses do not go to the police and instead go to the

defendant’s family or defense counsel. In State v. Ghere59, the Connecticut Supreme

Court stated that

Although we do not believe that an alibi witness has a duty to report

an alibi story to the police or, for that matter, to any other person, a

witness in many instances naturally may be expected to convey such

information, especially when the witness is friendly with the accused.

** Failure of the witness to do so would, under [those] circumstances,

constitute grounds for impeachment [because the failure to report an

alibi under such circumstances is] relevant on the issue of credibility

or, more specifically, the issue of fabrication.

A review of the Ghere briefs shows that this assertion is based on judicial

experience; neither party provided the Court with research into how alibi witnesses

behave. The Ghere opinion is akin to the historical belief discussed a decade later in

State v. Troupe60 that “any ‘normal’ woman would report a rape soon after its

occurrence. The clear implication of this assumption was that if the woman did not

complain, it was likely that no rape had occurred.” The Troupe Court recognized

that “[i]ndisputably, one of the historic premises of the doctrine—that it is natural

for the victim of a sexual assault to complain promptly following the assault—has

59

201 Conn. 289, 304, 513 A.2d 1226 (1986).

60

237 Conn. 284, 295, 677 A.2d 917 (1996).

18

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

been discredited substantially in contemporary times. The overwhelming body of

current empirical studies, data, and other information establishes that it is not

inherently ‘natural’ for the victim to confide in someone or to disclose, immediately

following commission of the offense, that he or she was sexually assaulted.”61 Alibi

research does not yet have an overwhelming body of empirical studies about

witness behavior, but there is enough research to suggest that Ghere’s assumption

is flawed and should be abandoned.

A witness may be afraid to get involved in a criminal case62 or to go to the

police or prosecutors. As one court observed, “it is a lamentable but undeniable fact

of modern society that some of our citizens harbor a mistrust for law enforcement

authority which leads them to shun contact with the police even when the

avoidance of contact is not in their own best interest.”63

Witnesses may be afraid of the police in general, or may have immigration

issues, child custody issues, or pending criminal charges that make them

61

Id. at 300-01.

62

See People v. Steede, 149 A.D.2d 744, 540 N.Y.S.2d 528 (2d Dep't 1989)

(witness explained that “there's reasons why you don't go down to that precinct to

volunteer, because if they see you in the presence of other people they may lock you

up too for no reason.”) This is not an unreasonable fear; Kory Wise, one of the

defendants in the Central Park Jogger case became a suspect and falsely confessed

to the crime having gone to the station as an alibi witness for Yusef Salaam. See

generally, Smith, Central Park Revisited, N.Y. MAGAZINE (10/21/02).

63

People v. Conyers, 52 N.Y.S.2d 454, 458 (1981).

19

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

particularly concerned about contradicting the police narrative. If the case has

received significant media attention, the witness may be afraid of becoming part of

the story. The witness may be afraid of disapproval from the victim’s family or

friends.

Witnesses may believe that once the defendant has been arrested, going to

the police or prosecutors, even with a strong alibi, will not lead to the end of the

case.64 The further along the case is, the less likely it is that exculpatory evidence

would lead to a dismissal instead of giving the prosecutor time to prepare an attack

on the evidence.65

No empirical research exists to suggest that alibis presented early in the

criminal investigation process are better for an innocent suspect. To avoid good-

faith mistakes, an innocent suspect may want to wait until he or she can confirm

64

See Crozier, Strange, & Loftus, Memory Errors in Alibi Generation: How an

Alibi can Turn Against Us, 35:1 BEHAV. SCI. & L. 6, 14 (2017).

65

Culhane & Horsch, Changed Alibis, Current Law Enforcement, Future Law

Enforcement, and Layperson Reactions, 39:7 CRIM. J. & BEHAV. 958, 975 (2012).

In 2000, a Commission of Inquiry was established in Manitoba, Canada to

look into the exoneration of Thomas Sophonow, falsely convicted of murder. The

Commissioner made a number of recommendations – as to alibi evidence, he

suggested that the witness be interviewed by officers other than those involved in

the investigation of the offense, that any interview with an alibi witness be recorded

in its entirety, that the witness be treated with respect and courtesy – the witness

should not be cross-examined, leading questions should not be used, police should

not suggest that they are mistaken, threaten, intimidate, or influence the witness to

change their story. The Honourable Peter Cory, Commissioner, THE INQUIRY

REGARDING THOMAS SOPHONOW 20, 99-100 (November 5, 2001).

20

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

the alibi, even if that means waiting until the eve of trial.66

The Alibi Witness and Defense Counsel

Defense counsel is obligated to make all reasonable efforts to identify and

interview potential alibi witnesses.67. This includes reasonable efforts to identify

and locate witnesses, even if the defendant doesn’t know their full name. “[C]ounsel

reasonably cannot limit the pretrial investigation of a case to only those leads

offered by the client himself. * * * counsel has an independent duty to investigate

potentially important witnesses not suggested by the client, including, of course,

potentially important alibi witnesses.” (internal citations omitted).68 “[A] decision by

counsel to forgo an investigation into the possible testimony of a potentially

significant witness is constitutionally impermissible unless counsel has a sound

justification for doing so; speculation, guesswork or uninformed assumptions about

the availability or import of that testimony will not suffice.”69 A thorough

investigation of an alibi defense is especially important when “the missing witness

66

Most jurisdictions have procedural rules requiring defense counsel disclose

an alibi to the prosecutor prior to trial. Counsel should keep these requirements in

mind and make proper disclosures.

67

Skakel v. Commissioner, 329 Conn. 1, 36, 188 A.3d 1 (2018); the Skakel case

and Gaines v. Commissioner, 306 Conn. 664, 51 A.3d 948 (2012) (discussed infra)

are rare examples of successful habeas claims that trial counsel was ineffective for

not investigating or presenting an alibi witness.

68

Skakel at 55.

69

Skakel at 24-35.

21

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

is disinterested in a case in which the other witnesses have a relationship to the

defendant.”70

The Skakel Court set out four factors to consider in reviewing the

reasonableness of trial counsel’s decision not to investigate and/or present alibi

witness/witnesses. They include: “(1) the importance of the alibi to the defense; (2)

the significance of the witness' testimony to the alibi; (3) the ease with which the

witness could have been discovered; and (4) the gravity of the criminal charges and

the magnitude of the sentence that the petitioner faced.”71

The defendant’s family or friends may seek out alibi witnesses, and try to

encourage them to meet with defense counsel, or a defense investigator. Counsel

should warn incarcerated defendants about trying to contact witnesses themselves

or discussing contacting witnesses with family. Incarcerated defendants’ phone calls

and mail are routinely recorded and monitored. A recording of a defendant’s call, or

copy of a letter, seeming to intimidate a witness or create a false alibi would be

devastating to the defense and may lead to additional charges of tampering and/or

obstruction of justice, as well as a jury instruction about consciousness of guilt.72

70

Skakel at 36.

71

(internal citations omitted) Skakel at 37.

72

Counsel should, of course, caution both defendants and their families

against actually tampering with witnesses or evidence, obstruction of justice, and

perjury, which can lead to separate prosecutions or arguments that such efforts

show consciousness of guilt.

22

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

Family and friends should likewise be cautioned about appearing as if they

are trying to pressure an alibi witness or influence his or her testimony. One

treatise opines that:

Alibi witnesses are often honest by mistaken as to the occasion to

which they testify. Many alibis are built up of the testimony of

witnesses who, approached by the defendant or someone in his behalf,

are asked leading questions such as to whether they do not remember

that at a particular time and place they were with the defendant and,

if the witnesses are friends or member of the family of the accused,

they are very likely to fix some occassion when they were in the

company of the defendant as having occurred on the date suggested in

the inquiry. In interviewing alibi witnesses they should be asked with

whom they have talked on the subject and what was said, when they

first had occasion to think back and recall the occasion, what means or

facts they have to identify the occasion as occurring on that particular

date and what other facts and incidents were connected with the

occasion in question.73

Ideally, a defense investigator should contact potential alibi witnesses instead. He

or she is likely to be trained in nonsuggestive questioning methods, will be able to

document the conversation, and can testify, if needed, at trial.

Counsel should look for any evidence to support the alibi – receipts, security

videos, and cell phone records, for example – and carefully document how the

supporting evidence was obtained and preserved.

Tunnel vision and confirmation bias, not to mention cynicism about an alibi

defense, may lead counsel to discount an alibi witness. Regardless of any cynicism,

73

Frick, CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION 24 (5th Ed. 1949).

23

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

have an investigator interview potential alibi witnesses, look for corroborating

physical evidence, and take statements as appropriate. Memory is fragile and

vulnerable to after-acquired information; if counsel does not investigate the alibi

early, then vital information may be lost forever.

Once counsel learns of an alibi or alibi witness, he or she must consider

whether the jurisdiction has a notice of alibi defense requirement and, if so, when it

must be complied with.74 Notice-of-alibi rules were enacted in the early 20th century,

and dramatically reduced the use of alibi defenses at trial.75 “Convictions where an

alibi was offered had greatly increased since passage of the act.”76 In one survey of

prosecutors, 81% of respondents said that alibis were “only occasionally successful”,

11% said that they were successful “about half of the time”, only 8% reported more

frequent success.77 As suggested above, the decline may not have been entirely due

to deterring false alibis, but could include accurate, truthful alibi witnesses

deterred by prosecutor questioning from giving strong testimony, or testifying at all.

If the defense is aware of potential alibi witnesses, but uncertain whether it

74

See Wardius v Oregon, 412 U.S. 470 (1973) (notice-of-alibi rules must

impose reciprocal obligations on the prosecution); Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78

(1970) (upholding Florida’s notice-of-alibi rule).

75

Epstein, Advance Notice of Alibi, 55 J. CRIM. L. CRIMINOLOGY & POLICE SCI.

29, 31 (1964).

76

Id.

77

Id.

24

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

will rely on an alibi defense at trial, then it may want to delay notice until a

decision has been made. (Notice must normally be given in time for the prosecution

to investigate the alibi witnesses if it wishes.) In Outing, trial counsel was

concerned about potential alibi witnesses who would say that the defendant was

less than a mile from the crime scene shortly after the murder.78 None of the

witnesses could pinpoint the defendant’s location at the exact time of the shooting.79

In that case, deciding to offer the alibi witnesses and disclosing them to the

prosecution could have weakened the defendant’s case. Similar problems could arise

if the alibi witnesses describe the defendant wearing something like descriptions of

the culprit around the time that the crime occurred.

Whether to Offer an Alibi Defense

An alibi is not a traditional affirmative defense – it is a response to the

prosecution’s case. Logically, an accurate and truthful80 alibi means that the

prosecutor’s witnesses have mis-identified an innocent defendant either through

good-faith eyewitness identification mistakes, or through deliberate lies by co-

78

Outing at 522.

79

Outing at 521.

80

Both the prosecutor and defense counsel are, of course, prohibited from

offering perjured testimony.

25

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

offenders or cooperating witnesses.81 Alibi defenses may work well when combined

with arguments about mistaken eyewitnesses, lying informants or co-operating

witnesses, and investigative failures or omissions, including a rush to judgment and

ignoring exculpatory evidence in the investigation. If the prosecution’s case is based

on physical or forensic evidence establishing that the defendant was at the crime

scene, then even an accurate, truthful alibi may be unpersuasive.82

Counsel needs to consider the relative strengths of the prosecution and

defense cases and the seriousness of the charges. Counsel should consult colleagues

to see how the prosecutor in this case has cross-examined alibi witnesses and

argued about alibi in closing. Counsel then needs to think about the alibi witnesses

and any corroboration of the alibi.

Counsel should make the decision whether or not to present an alibi along

with the client. Admittedly, decisions about which witnesses to call and what

defenses to raise are traditionally within trial counsel’s discretion. When a client is

represented by assigned counsel, he or she has no right to his choice of counsel.83

81

See Griffin v. Warden, 970 F.2d 1355, 1359 (4th Cir. 1992) ("[e]yewitness

identification evidence... is precisely the sort of evidence that an alibi defense

refutes best"); State ex rel. Wearry v. Cain, 161 So.3d 620, 621-22 (La.2015) (same).

82

The defendant may have had innocent access to the area and left DNA or

fingerprints prior to the crime. Video evidence is often unclear and may result in a

mistaken identification. Forensic evidence may be tainted by confirmation bias if

the examiner was aware of extrinsic inculpatory information at the time of the test.

83

See Caplin & Drysdale, Chartered v. United States, 491 U. S. 617, 624-625

26

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

Unless the defendant can show circumstances mandating a change of assigned

counsel well before the start of trial, he or see either cedes to his assigned lawyer

trial management decisions or waives his right to counsel under Faretta v.

California84. Those ceded decisions included “what arguments to pursue, what

evidentiary objections to raise, and what agreements to conclude regarding the

admission of evidence.”85

It is the client’s future that is at stake in the trial. The client should have

some input on the decision of whether or not to present an alibi defense. It may be

important to the client that his or her family testify and demonstrate the client’s

innocence, even if that risks weakening the case. The final decision is counsel’s, but

if the client feels strongly about it, counsel should expect to have to defend the

decision in post-conviction proceedings.

(1989). See also United States v. Gonzalez-Lopez, 548 U.S. 140, 144 (2006); Wheat v.

United States, 486 U. S. 153, 159 (1988).

84

422 U.S. 806 (1975).

85

McCoy v. Louisiana, 138 S.Ct. 1500, 1508 (2018) (defendant decides

whether to plead guilty, waive the right to a jury trial, testify in one's own behalf,

and forgo an appeal and sets the general objectives of his defense.

In McCoy, Justice Alito contends that the criminal justice system “would

break down if defense counsel were required to obtain the client's approval for every

important move made during the course of the case.[] Among the decisions that

counsel is free to make unilaterally are the following: choosing the basic line of

defense, moving to suppress evidence, delivering an opening statement and deciding

what to say in the opening, objecting to the admission of evidence, cross-examining

witnesses, offering evidence and calling defense witnesses, and deciding what to say

in summation.” McCoy at 1516.

27

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

While the jury will be instructed that the defendant does not need to prove

the alibi is true, and that the prosecutor must disprove it to prove its case beyond a

reasonable doubt, jurors may nevertheless perceive the alibi as pitting the

credibility of the alibi witnesses against the prosecutor’s witnesses.86 In some cases,

jurors may even be instructed that if they find the alibi witnesses testified falsely,

then they can infer the defendant’s consciousness of guilt for manufacturing a false

alibi. Counsel may want to consider asking for alternative jury instructions to

emphasize that the burden of proof rests on the prosecutor and does not shift to the

defense.

Defense Counsel Preparation of Alibi Witnesses

Counsel should be careful not to tamper or interfere with the alibi witnesses,

or to appear to do so. Counsel should caution alibi witnesses that the police and/or

prosecutor are likely to contact them. As noted above, police or prosecutors may

86

See e.g. Spearman v. Commissioner, 164 Conn. App. 530, 548 n. 12, 138

A.3d 378 (2016) where defense counsel did not offer alibi witnesses because:

[It was] my fear ... that the jurors would potentially compare the two

— the two versions and see that maybe [the petitioner's] family had a

greater motive to protect him and * * * compare that [version to] [the

prosecutor’s witness’] motive for a couple hundred dollars and say,

well, the [defendant’s witnesses] have a greater motive and maybe

water down the proof beyond a reasonable doubt standard and not hold

the state to that — to that high standard, so I was — I made — you

know, made the decision that it was — that we had done enough on

cross-examination and didn't want to take that risk of — to having the

jury water down the standard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. And

that was only made after — after the state rested.

28

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

threaten the witnesses with obstruction or perjury charges for contradicting their

case. If the witness feels threatened or pressured, the witness should let defense

counsel know that.

Some jurisdictions permit defense counsel to suggest that witnesses not talk

to the prosecutor and/or police87 – others view this as potentially obstruction or

tampering. If the witness refuses to meet with the prosecutor and/or police, expect

the witness to be cross-examined about this at trial. At minimum, counsel should

suggest that if an alibi witness wants to talk to the police and/or prosecutors, that

he or she ask for any interview to be recorded from start to finish so that there is an

objective record of what was said, and how it was said. Counsel can then request a

copy of the recording through discovery.

Counsel should caution witnesses that police and/or prosecutors will review

their public social media posts and that they should be wary of unusual social

media contacts or friend requests after their names have been disclosed.88 Witnesses

should let defense counsel know of any suspicious contacts or activity.

Motion in Limine: Voir Dire when Witness Comes Forward Late

87

See Foster v. State, 35 So. 3d 112 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2010) (proper for

attorney to give his office address as contact address for alibi witnesses).

88

See Browning, Prosecutorial Misconduct in the Digital Age, 77 ALB. L. REV.

881, 889-902 (2013-14) (prosecutor created a false social media identity and

engaged in social media chats with alibi witnesses to persuade them to recant their

alibi).

29

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

Counsel could ask the trial court to preclude cross-examination of an alibi

witness about the timing of their disclosure until the prosecutor demonstrates that

“the witness was aware of the nature of the charges pending against the defendant,

had reason to recognize that he possessed exculpatory information, had a

reasonable motive for acting to exonerate the defendant and, finally, was familiar

with the means to make such information available to law enforcement

authorities.”89 The witness should be questioned outside of the jury’s presence if

there is any concern that the witness was reluctant to come forward because of

otherwise inadmissible personal concerns or fear of the defendant or victim’s family.

Dawson and Bryant also suggest voir dire if there is a possibility that the witness

was explicitly told by defense counsel not to go to the police or prosecutor – “in such

a case examination on the issue of the witness' post-consultation silence would be

improper and could well result in a mistrial.”90

89

People v. Dawson, 50 N.Y.2d 311, 321 n.4, 406 N.E.2d 771 (1980). See State

v. Bryant, 202 Conn. 676, 705-06, 523 A.2d 451 (1987); Commonwealth v. Brown, 11

Mass. App. 288, 416 N.E.2d 218 (1981).

90

Bryant at 706.

Counsel should be wary of any advice that may be construed as tampering

with a witness or interfering in a police investigation, and should consult the ethics

rules and case law in his or her jurisdiction. See Commonwealth v. Hart, 455 Mass.

230, 238, 914 N.E.2d 904 (2009) (Massachusetts ethics rules now prohibit counsel

from requesting "a person other than a client to refrain from voluntarily giving

relevant information to another party." Mass. R. Prof. C. 3.4 (f).

30

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

Counsel should expect a vigorous cross-examination.91 Defense counsel needs

to prepare the alibi witness to answer questions about:

• What is the witness’ relationship with the defendant?

• Any other information that affects the witness’ credibility,

including past convictions, or suggests bias.92

• Why the witness came forward when they did?

• When did the witness realize the defendant had been arrested?

• What did the witness learn about the crime?

• The prosecutor may ask a witness if he or she was aware

of other incriminating information like witnesses, forensic

evidence, or an admission/confession.

• When did the witness realize he or she could provide an alibi?

• If the witness did not go directly to the police or prosecutors, why not?

• Note: if the witness did go to the police or prosecutors, is there

any recording of the interaction? Did police or prosecutors

pressure the witness about the alibi?

• How is the witness sure about the alibi?

91

See State v. Briggs, 179 Conn. 328, 333, 426 A.2d 298 (1979) ("[w]here a

defendant proposes an alibi as his defense, one permissible method of determining

whether the alibi was fabricated is to inquire into the specific details and the

surrounding circumstances of the alibi on cross-examination in an attempt to show

inconsistencies in the testimony of the various alibi witnesses, since the claim of

alibi is subject to searching scrutiny").

92

Asking the witness if he or she would lie or shade the truth for the

defendant was held to be improper – speculative and argumentative – in Watson v.

State, 257 Ark. 876, 531 S.W.2d 205 (1975).

31

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

• Does the witness have any supporting physical evidence?

• If there was supporting evidence not under the witness’ control,

did he or she tell anyone about it?

When did You Realize You had Exculpatory Information?

Witnesses who are casually acquainted with the defendant may not realize

that they can provide an alibi. Witnesses may be uncertain about dates or times –

for the witness the crime may have occurred when he or she was doing something

routine, and had not paid particular attention to specific times or places.

Sometimes the exact time or location of the offense is uncertain. Not only

could witnesses be unsure if they could provide an alibi for that time, investigators

or forensic experts who become aware of a strong alibi may subconsciously

reconsider the evidence and change their estimate of time or location to still support

the defendant as culprit.

Did You have a Motive to Exonerate the Defendant?

Most alibi witnesses are the defendant’s family, friends, co-workers, and

other people who know the witness well (“motivated” witnesses).93 This is normal –

one spends the most time around one’s family, friends, and co-workers.94

93

See Culhane & Hosch, An Alibi Witness’ Influence on Mock Jurors’ Verdicts,

34:8 J. APP. SOC. PSYCH. 1604, 1606-07 (2004).

94

Id.

32

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3572102

Draft Accepted for Publication in vol. 56 of the Criminal Law Bulletin (2020).

Unfortunately, police and jurors tend to be skeptical of motivated alibi witnesses.95

If the crime took place during business hours on a weekday, the suspect’s

alibi witnesses are most likely his or her co-workers. If it took place late at night or

on a holiday, then the suspect’s alibi witnesses are most likely family. Expecting the

suspect to be able to provide neutral alibi witnesses for most dates and times is

unrealistic.

Would You Lie for the Defendant?

What about the popular assumption that friends and family are likely to lie

for the defendant? In one study, 62% of jury-eligible participants felt a biologically-

related alibi witness would be most likely to lie for a defendant; 50% felt the same