Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Case Study Subsidized Wheat Production in Japan-1

Case Study Subsidized Wheat Production in Japan-1

Uploaded by

anh.nguyen210176Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Case Study Subsidized Wheat Production in Japan-1

Case Study Subsidized Wheat Production in Japan-1

Uploaded by

anh.nguyen210176Copyright:

Available Formats

Subsidized Wheat Production in Japan

Japan is not a particularly good environment for growing wheat. Wheat produced on large fields in the

dry climates of North America, Australia, and Argentina is far cheaper and of much higher quality than

anything produced in Japan. Indeed, Japan imports some 80 percent of its wheat from foreign producers. Yet

tens of thousands of farmers in Japan still grow wheat, usually on small fields where yields are low and costs

high, and production is rising. The reason is government subsidies designed to keep inefficient Japanese wheat

producers in business. In 2016, Japanese farmers were selling their output at market prices, which were

running at $9 per bushel, but they received an average of at least $35 per bushel for their 2016 production!

The difference - $26 a bushel - was government subsidies paid to producers. The estimated costs of these

subsidies were more than $700 million in 2016.

To finance its production subsidy, Japan operates a tariff rate quota on wheat imports in which a

higher tariff rate is imposed once wheat imports exceed the quota level. The in-quota rate tariff is zero, while

the over- quota tariff rate for wheat is $500 a ton. The tariff raises the cost so much that it deters over-quota

imports, essentially restricting supply and raising the price for wheat inside Japan. The Japanese Ministry of

Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) has the sole right to purchase wheat imports within the quota (and

since there are very few over-quota imports, the MAFF is a monopoly buyer on wheat imports into Japan). The

MAFF buys wheat at world prices, then resells it to millers in Japan at the artificially high prices that arise due

to the restriction on supply engineered by the tariff rate quota. Estimates suggest that in 2015, the world

market price for wheat was $5.96 per bushel, but within Japan the average price for imported wheat was

$10.23 a bushel. The markup of a bushel yielded the MAFF in excess of million in profit. This “profit” was then

used to help cover the $700 million cost of subsidies to inefficient wheat farmers, with the rest of the funds

coming from general government tax revenues.

Thanks to these policies, the price of wheat in Japan can be anything from 80 to 120 percent higher

than the world price, and Japanese wheat production, which exceeded 850,000 tons in 2016, is significantly

greater than it would be if a free market were allowed to operate. Indeed, under free market conditions, there

would be virtually no wheat production in Japan since the costs of production are simply too high. The

beneficiaries of this policy are the thousands of small farmers in Japan who grow wheat. The losers include

Japanese consumers, who must pay more for products containing wheat and who must finance wheat

subsidies through taxes, and foreign producers, who are denied access to a chunk of the Japanese market by

the over-quota tariff rate. Why then does the Japanese government continue to pursue this policy? It

continues because small farmers are an important constituency and Japanese politicians want their votes.

Source: Charles-Hill-International-Business 9ed. Page 217

1. What type of trade barrier has Japan imposed on imported wheat?

- They operated tariff rate quota on imported wheat, in which a higher tariff rate is imposed once wheat

imports exceed the quota level (The in-quota rate tariff is zero, while the over-quota tariff rate for wheat

is $500 a ton).

2. How much is the world market price of wheat? In Japan?

- In 2015, the world price of wheat was $5.96 per bushel, while in Japan was $10.23 per bushel.

3. What is the landed cost of imported wheat in Japan and what is the cost of local wheat?

- Within Japan the average price for imported wheat was $10.23 a bushel. Japanese farmers were selling

their output at market prices which were running at $9 per bushel, but they received an average of at

least $35 per bushel due to subsidies.

4. What would be impact of introducing free trading in wheat in Japan?

- There would be virtually no wheat production in Japan since the costs of production are simply too high

5. Who win, who lose in this case?

- The winners: the thousands of small farmers in Japan who grow wheat.

- The losers:

o The consumers (have to pay more for products containing wheat).

o The ones who must finance wheat subsidies through taxes.

o Foreign producers (are denied access to a chunk of the Japanese market by the over-quota tariff

rate).

6. Why is Japanese government interested in continuing with local wheat cultivation?

- Because small farmers are an important constituency and the government need their votes.

You might also like

- Sumati Varma - Fundamentals of International Business (2018, Pearson India) - Libgen - Li (MConverter - Eu)Document617 pagesSumati Varma - Fundamentals of International Business (2018, Pearson India) - Libgen - Li (MConverter - Eu)YashaswiNo ratings yet

- A Position Paper On The Philippine Rice Tariffication Law: Against Rice TarifficationDocument10 pagesA Position Paper On The Philippine Rice Tariffication Law: Against Rice TarifficationCamila Flores75% (4)

- ARGUMENTATIVE-ESSAYDocument5 pagesARGUMENTATIVE-ESSAYtri shia100% (2)

- The Economics of Us Farm Support ProgramsDocument14 pagesThe Economics of Us Farm Support ProgramsrizkielimbongNo ratings yet

- Paddy Whacked The EconomistDocument5 pagesPaddy Whacked The EconomistAlena Francine EballoNo ratings yet

- Cheaper Rice For NowDocument12 pagesCheaper Rice For NowRey Anne DongonNo ratings yet

- Declining Prices of RiceDocument2 pagesDeclining Prices of RiceJoanna AbreaNo ratings yet

- REPUBLIC ACT No-WPS OfficeDocument3 pagesREPUBLIC ACT No-WPS OfficeKen KanekiNo ratings yet

- Rice Tariffication LawDocument18 pagesRice Tariffication LawJasmine Garcia100% (1)

- Practicality: No To Rice Tarrification Law. Ladies and Gentlemen, Once Again Good Morning!Document2 pagesPracticality: No To Rice Tarrification Law. Ladies and Gentlemen, Once Again Good Morning!lauro sr legarioNo ratings yet

- Spice Market Update: ContentsDocument6 pagesSpice Market Update: ContentsMohit JailkhaniNo ratings yet

- Upgrade RTLDocument2 pagesUpgrade RTLTin TarubalNo ratings yet

- Rice StudyDocument59 pagesRice StudyLEIZLNo ratings yet

- Agriculture Growth Development - 1Document41 pagesAgriculture Growth Development - 1mariamikaelad8No ratings yet

- Dairy Investment ProposalDocument13 pagesDairy Investment ProposalRashid IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Indian Food IndustryDocument95 pagesAnalysis of Indian Food IndustryRam DakeNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper 2Document2 pagesReaction Paper 2Pocholo Regencia100% (2)

- GROUP1 UmajiDocument11 pagesGROUP1 UmajiKevin Matibag100% (3)

- Commodity June July Tur Dal Channa Dal Urad Dal SugarDocument4 pagesCommodity June July Tur Dal Channa Dal Urad Dal SugarSneha AgarwalNo ratings yet

- 02 Productivity Crisis in FarmingDocument2 pages02 Productivity Crisis in FarmingMuhammad AshrafNo ratings yet

- 1588084812feasibilty ReportDocument40 pages1588084812feasibilty ReporttatawalatatuNo ratings yet

- Rice TarrificationDocument2 pagesRice TarrificationTeddy EspirituNo ratings yet

- Economics Presentation of Market Impact of Price Support Scheme For Sugar (For IB Diploma)Document26 pagesEconomics Presentation of Market Impact of Price Support Scheme For Sugar (For IB Diploma)4I (02) Lee Shui HangNo ratings yet

- Uganda MacroeconomicDocument16 pagesUganda MacroeconomicAndrew MwesigyeNo ratings yet

- Soybeans in ChinaDocument4 pagesSoybeans in ChinaEvan Situ100% (1)

- Rice Tariffication LawDocument2 pagesRice Tariffication LawCharLene MaRie100% (1)

- It Ia AritroDocument5 pagesIt Ia AritroPreet kotadiyaNo ratings yet

- Think Rice - Think ThailandDocument4 pagesThink Rice - Think ThailandMilling and Grain magazineNo ratings yet

- Module 2 - Foreign TradeDocument2 pagesModule 2 - Foreign TradejessafesalazarNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Rice Tariffication Law To The Selected Farmers Consumers Traders of Brgy Duhat UmalividuyaDocument55 pagesThe Effects of Rice Tariffication Law To The Selected Farmers Consumers Traders of Brgy Duhat UmalividuyaAngel Ann V. RebongNo ratings yet

- Advantage and D-WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesAdvantage and D-WPS Officecharlotte frances bagaoisanNo ratings yet

- Importance of Agriculture MarketingDocument3 pagesImportance of Agriculture MarketingShuvojeet MandalNo ratings yet

- Contemporary WorldDocument3 pagesContemporary WorldRonna Jean AndeNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper CWDocument3 pagesReaction Paper CWmedranolyca45No ratings yet

- Poultry Production Group 1 ZariaDocument27 pagesPoultry Production Group 1 ZariaSagir Musa SaniNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics - Assignment 2 - Oliva - BSA1ADocument6 pagesManagerial Economics - Assignment 2 - Oliva - BSA1AJan Drew OlivaNo ratings yet

- Rice Trade Policy and Rice Tariffication LawDocument5 pagesRice Trade Policy and Rice Tariffication LawJan Marinel A. SerinoNo ratings yet

- Rice Tariffication LawDocument2 pagesRice Tariffication LawDane Delina0% (1)

- Basmati ReportDocument18 pagesBasmati ReportJai SoniNo ratings yet

- Benin Coarse Grains and Rice Report - Lagos - Benin - 1!29!2013Document9 pagesBenin Coarse Grains and Rice Report - Lagos - Benin - 1!29!2013Edem CHABINo ratings yet

- Practical Research FarmersDocument39 pagesPractical Research FarmersNhaaa100% (1)

- Final Research Impact On RTLDocument38 pagesFinal Research Impact On RTLAljo KimayongNo ratings yet

- Oilseeds and Products Annual Tokyo Japan 4-7-2016Document20 pagesOilseeds and Products Annual Tokyo Japan 4-7-2016Dane SpaceyNo ratings yet

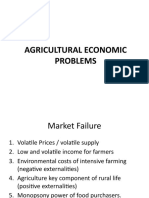

- Agricultural Economic ProblemsDocument23 pagesAgricultural Economic ProblemsRiska FadilaNo ratings yet

- Ateneo RiceDocument4 pagesAteneo RiceRizza Mae RamonesNo ratings yet

- Ethiopia Oilseeds Report Annual - Addis Ababa - Ethiopia - 01!16!2020Document21 pagesEthiopia Oilseeds Report Annual - Addis Ababa - Ethiopia - 01!16!2020SelamNo ratings yet

- Negative Effects of Rice Tariffication LawDocument2 pagesNegative Effects of Rice Tariffication LawUnsolicited Comment100% (1)

- Why Are Soybeans Valuable?Document2 pagesWhy Are Soybeans Valuable?karanNo ratings yet

- The Capitalist Are So High. According To PSA (2020), The Country's Nominal Wage Rate ofDocument2 pagesThe Capitalist Are So High. According To PSA (2020), The Country's Nominal Wage Rate ofJames Ezra EvangelioNo ratings yet

- POSITION PAPER: English For Academic and Professional PurposesDocument3 pagesPOSITION PAPER: English For Academic and Professional PurposesJames Ryan SorianoNo ratings yet

- JAURIGUE - Rice Importation in The PhilippinesDocument10 pagesJAURIGUE - Rice Importation in The PhilippinesRiyya Jaurigue100% (1)

- USDA - 2020 - 07 - Foreign Farm Labor's Role Growing in Japan - Tokyo - JapanDocument5 pagesUSDA - 2020 - 07 - Foreign Farm Labor's Role Growing in Japan - Tokyo - JapantruefireNo ratings yet

- Zimbabwe's Farmers Lament: The Taxes Are Just Too Much'Document3 pagesZimbabwe's Farmers Lament: The Taxes Are Just Too Much'Gudo MichaelNo ratings yet

- Export Marketing of Agricultural and Food ProductsDocument18 pagesExport Marketing of Agricultural and Food ProductsRuchira ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Proposal: Zurmat Flour Mill: 1. Executive SummaryDocument10 pagesProposal: Zurmat Flour Mill: 1. Executive SummaryNafyad Tola Abebe100% (1)

- Case CritiqueDocument4 pagesCase CritiqueErvin SagunNo ratings yet

- Eco Analysis MidtermDocument18 pagesEco Analysis MidtermKim Patrick VictoriaNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1 BULATINDocument3 pagesCase Study 1 BULATINHairu VincentNo ratings yet

- Daily: by Riceplus MagazineDocument20 pagesDaily: by Riceplus MagazineMujahid AliNo ratings yet

- For CH 9Document17 pagesFor CH 9Jayavarma S me19b115No ratings yet

- Food Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets July 2018From EverandFood Outlook: Biannual Report on Global Food Markets July 2018No ratings yet

- IPO Prospectus List - Draft and Red Herring Prospectus PDFDocument11 pagesIPO Prospectus List - Draft and Red Herring Prospectus PDFDavis ManNo ratings yet

- Farm To Market Road Development in Rural AreasDocument9 pagesFarm To Market Road Development in Rural AreasIvy TalisicNo ratings yet

- 181120231754-SBI RFEDigital TransformationDocument1 page181120231754-SBI RFEDigital TransformationkanstarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9Document1 pageChapter 9Liza SoberanoNo ratings yet

- FM 02 Central Banking and Monetary PolicyDocument10 pagesFM 02 Central Banking and Monetary PolicyIvy ObligadoNo ratings yet

- Tata SteelDocument56 pagesTata SteelG-TYBAF-24- SHRADDHA-JNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement AnalysisDocument18 pagesFinancial Statement Analysis223001006No ratings yet

- Bahana Company Update 1Q24 HMSP 25 Apr 2024 - Buy TP Rp1,000Document11 pagesBahana Company Update 1Q24 HMSP 25 Apr 2024 - Buy TP Rp1,000Candra AdyastaNo ratings yet

- 17.3-Practice Questions Break Even AnalysisDocument6 pages17.3-Practice Questions Break Even AnalysisZak OxmaniNo ratings yet

- Individual Report Brief Jan 2024Document2 pagesIndividual Report Brief Jan 2024shenyi.sixuanNo ratings yet

- What Is Gross Income - Definition, Formula, Calculation, and ExampleDocument7 pagesWhat Is Gross Income - Definition, Formula, Calculation, and ExampleKapil SharmaNo ratings yet

- AFA II ModuleDocument71 pagesAFA II ModulefageenyakaraaNo ratings yet

- Financial Derivatives - Exercises - Chap4 - SolDocument9 pagesFinancial Derivatives - Exercises - Chap4 - SolAbdelhadi KaoutiNo ratings yet

- Cost of Preference Share CapitalDocument12 pagesCost of Preference Share CapitalNeha KumariNo ratings yet

- Non-Current Asset Held For Sale & Discontinued Operations WorkBookDocument16 pagesNon-Current Asset Held For Sale & Discontinued Operations WorkBookMusawer ShirzaiNo ratings yet

- 18-03-23 Exer Chapte3Document1 page18-03-23 Exer Chapte3Nguyễn ThanhNo ratings yet

- Itr 2Document34 pagesItr 2Anurag SharmaNo ratings yet

- QA SIPACKS in Business Finance Q3 W1 7Document91 pagesQA SIPACKS in Business Finance Q3 W1 7Roan DiracoNo ratings yet

- Internship Report Index BBADocument9 pagesInternship Report Index BBACrazy SoulNo ratings yet

- Retained EarningsDocument2 pagesRetained EarningsJustine MaravillaNo ratings yet

- Final Account of Joint Stock CompanyDocument8 pagesFinal Account of Joint Stock CompanyanupsuchakNo ratings yet

- Commercial Applications BookDocument17 pagesCommercial Applications BookOm PatilNo ratings yet

- National Westminster Bank USADocument4 pagesNational Westminster Bank USAChris.No ratings yet

- Golden Notes - Mercantile Law - RemovedDocument154 pagesGolden Notes - Mercantile Law - RemovedJazer DairoNo ratings yet

- 2ndyr - 2ndMT - Business Taxation - 2324Document26 pages2ndyr - 2ndMT - Business Taxation - 2324angelo eleazarNo ratings yet

- Jio (Marketing Strategy Analysis)Document28 pagesJio (Marketing Strategy Analysis)Anwar BNo ratings yet

- Kan Healthcare Fund Deck Draft 1.0Document35 pagesKan Healthcare Fund Deck Draft 1.0Ramani NairNo ratings yet

- QP Xi BST PDFDocument8 pagesQP Xi BST PDFJohn JoshyNo ratings yet

- Intacc V1 ProblemsDocument26 pagesIntacc V1 ProblemsacctgnotesforreviewNo ratings yet