Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 1

Chapter 1

Uploaded by

FARIDA subaidi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views3 pagesThis chapter introduces the topic of ekranisasi, the adaptation of works into films in Indonesia. Ekranisasi has become prominent in recent decades, but the history of adapting novels into films in Indonesia's colonial period is not well documented. The chapter aims to explore the earliest cases of ekranisasi by identifying the individuals and social factors involved in the process. It defines key concepts like films, novels, and the adaptation process (ekranisasi). It also discusses how ekranisasi can be viewed as a social act, and establishes theoretical frameworks for understanding the material object of the study and social actors involved in the colonial period adaptations.

Original Description:

Original Title

CHAPTER 1

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis chapter introduces the topic of ekranisasi, the adaptation of works into films in Indonesia. Ekranisasi has become prominent in recent decades, but the history of adapting novels into films in Indonesia's colonial period is not well documented. The chapter aims to explore the earliest cases of ekranisasi by identifying the individuals and social factors involved in the process. It defines key concepts like films, novels, and the adaptation process (ekranisasi). It also discusses how ekranisasi can be viewed as a social act, and establishes theoretical frameworks for understanding the material object of the study and social actors involved in the colonial period adaptations.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views3 pagesChapter 1

Chapter 1

Uploaded by

FARIDA subaidiThis chapter introduces the topic of ekranisasi, the adaptation of works into films in Indonesia. Ekranisasi has become prominent in recent decades, but the history of adapting novels into films in Indonesia's colonial period is not well documented. The chapter aims to explore the earliest cases of ekranisasi by identifying the individuals and social factors involved in the process. It defines key concepts like films, novels, and the adaptation process (ekranisasi). It also discusses how ekranisasi can be viewed as a social act, and establishes theoretical frameworks for understanding the material object of the study and social actors involved in the colonial period adaptations.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 3

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND

Ekranisasi (literally “screenification”) is an Indonesian word indicating the adaption

of a work form another medium to the screen; the term is derived from the French ecran,

meaning ‘screen’, and the suffix-isasi, which is equivalent to the English- ization, or

‘process of becoming’. In recent years, such works (particularly those adapted from

novels) have dominated the country’s box office and awards ceremonies. By 2012, four

of the five highest-grossing Indonesian films were adapted from novels (“Data Penonton

(2007-2013”). The 2011 Citra Award for Best Film went to an adaptation, Sang Penari

(from the novel Ronggeng Dukuh Paruk by Ahmad Tohari; Kurniasari, 2011) and in both

2011 and 2012 indonesia’s submission to the Academy Awards was an adaptation of a

novel.

Despite the prominence of films adapted form novels, the history of this phenomenon

is poorly described. If we are to believe Usmar Ismail’s spiel while promoting Anak

Perawan di Sarang Penjamun (1962; form the novel of the same name by Sutan Takdir

Alisjahbana), Which he touted as the first film to unite writers and filmmakers white a

common goal the history of film adaptations from novels in Indonesia only dates to the

1960s. Such a position is, however, untenable, as indicated by contemporary journalist

Rosihan Anwar (1962: 3), who writes “if I am not mistaken, before World War II Marah

Roesli’s Sitti Nurbaya was adapted form film “this suggests that such adaptations predate

Indonesia’s independence.

Anwar’s doubts were well-founded. Although Siti Noerbaja, wich was released in

1941, was not the earllest adaptation of novel in the Dutch East Indies (pre-independence

Indonesia). The earliest domestic film adapted from a novel in the archipelago was, in

fact, released fourteen years earlier; this work, G. Kruger’s Eulis Arjib, was adapted from

a Sundanese-language novel by Jochana, As will be shown, 11 of the 100-odd fiction

films produced between 1926, when the area’s first domestic fiction film Loetoeng

kasaroeng was released, and 1949, when the Dutch recognized Indonesia’s independence

and the Dutch East Indies was dissolved, were adapted from novels.

Multiple works discuss the films produced in the Indies and the companies and

individuals behind these productions; the most detailed of these is the collaboration

between Misbach Yusa Biran, Taufik Adbullah, and SM Ardan titled Film Indonesia

Bagian I: 1900-1950 (reprinted with some changes in 2009 as Sejarah Film 1900-1950).

However, the process of ekranisasi in the Indies has yet to be presented as a single,

coherent narrative, nor have the social factors behind the act of ekranisasi been described

in any detail. Though Biran (2009) and Said (1982) do mention which films were

adapted from novels, and in some places discuss the role of film production in society,

the neglect to discuss the adaptation process itselt or the related social factors.

We propose that an understanding of the earliest films adapted form novels is

necessary in order to understand better the history of ekranisasi and its role in Indonesian

society; only through an understanding of the past can we give meaning to the present.

As such, this book explores the earliest cases of ekranisasi in the Indonesian archipelago,

focusing on the colonial period. To do so, we indikates which individuals were behind

the social act of ekranisasi in the Dutch East Indies, as well as the known instances of

this social act. We further explore the social factors in the colony which likely influenced

the social act of ekranisasi, and based on this we attempt to answer how such social

factors affected the screen adaptation process. This includes, but is no limited to, why

certain novels were selected over others for adaptation; why cerratain novels were not

adapted; how and why aspects of the story were changed; why stage performances were

a consideration in selecting novels to be adapted; and how the race of persons performing

the social act influenced the adaptation process.

1.2 THEORETICAL FRAME WORK

1.2.1 Film, Novel, and Ekranisasi

An understanding of three basic concepts-films, novels, and ekranisasi-is required to

understand the material object of this study. For film, we derive our understanding from

the standard dictionary definition. A film, according to Oxford, is a story or event

recorded by a camera as a set of moving images and shown in a cinema or on television.

As television was non-extant in the Dutch East Indies, and novels are by definition

fiction, we narrow this definition to a fictional story or event recorded by a camera as a

set of moving images and shown in a cinema. As stated above, and enumerated by Biran

(2009: 379-386), some 100 works produced in the Dutch East Indies fit this definition.

The term novel is somewhat more difficult to define. Oxford defines it as a fictitious

prose narrative of book length, typically representing character and action with some

degree of realism (“Novel”), a general definition which leaves much room for debate,

particularly regarding length and the degree of “realism” (a term which, if defined too

strictly, excludes all forms of fantasy and most science fiction) required. Some

organizations, such as the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (“Nebula

Rules”), give definitions of length which are based on word count, with shorter works

being classified as (in increasing length) short stories, novelettes, novellas. However,

such a fixed definition does not properly describe the state of prose in the Dutch East

Indies: G. Francis’ Njai Dasima, as compiled by Pramoedya Ananta Toer in Tempo

Doeloe (223-247), is well under 20,000 words, while Marah Roelis’s Sitti Nurbaya is

over 80,000. As such, for the purposes of this paper we will define a novel, with an

addendum to exclude traditional works published as books, as a fictitious prose narrative

released as an individual book and credited to a named author or authors, typically

representating character and action.

The third key concept here, ekranisasi, or the adaptation of novels into films, is

derived from the above two definitions, combined with the dictionary definition of

adapt: “to make (something) suitable for a new use or purpose; modify” (“Adapt”), a

definition which implies that what is adapted is still remnant in some form in the

adaptation produced; a work which does not show any sign of the original source

material cannot be said to adapted from it. Ultimately, we define the adaptation of novels

into films as the modification of fictitious prose narrative, one released as an individual

book, credited to a named author, and typically representing character and action, as a

fictional story or event recorded by a camera as a set of moving images and shown in a

cinema.

Throughout this book we will use ekranisasi and adaptation of novels into films

interchangeably. A third term, alih wahana, which has gained currency in Indonesian

studies into the screen adaption process, has not been used. Alih wahana (‘media

adaptation’) is too general to be of use here; it does not differentiate between target

mediums. Aside form the adaptation of novels, poems, comic books and stage plays into

film, alih wahana could include such social acts as the adaptation of films to novels,

poem to stage plays, and even statues to poetry. As such, ekranisasi-in which the film

aspect is emphasized-remains the best term for this book.

Regarding the material object of this study, there are two variables; the identity of

work as a film, and its identity as a novel. Both are binary; a work is either a film or not,

either a novel or not. In this study, works which are neither films nor novels have not

been included. There could, conceivably, be a gradation in the ekranisasi process based

on how faithful a film adaptation is to the original novel, ranging from a complete

reproduction, mostly, faithful, somewhat faithful, barely faithful, and almost unrelated.

However, as most films from the Indies have been lost, such a detailed gradation is not

possible for films from the colony. It is impossible to accurately judge how faithful a

film was to its source novel without having acces to the film itself. However, since

promotional materials from the time exist and can be consulted, a basic understanding of

the main story and major variations of the underlying work can be known.

1.2.2 Social Act and Social Actors

The above understanding of the research object shall be combined with a theoretical

understanding of ekarnisasi as a social act, a concept promoted in the sociologicak

theory of max Weber. Though Weber wrote

You might also like

- 3 Historiography Between Scholarship and Poetry.Document10 pages3 Historiography Between Scholarship and Poetry.sandjc9511No ratings yet

- The Issue of Fidelity in Film AdaptationsDocument7 pagesThe Issue of Fidelity in Film Adaptationssebastian_stratan67% (3)

- Representations of Hong Kong in The Films of Wong Kar-WaiDocument55 pagesRepresentations of Hong Kong in The Films of Wong Kar-WaiAlex TurnerNo ratings yet

- Anime and The Art of Adaptation-Eight Famous Works From Page To Screen (Dani Cavallaro, 2010)Document221 pagesAnime and The Art of Adaptation-Eight Famous Works From Page To Screen (Dani Cavallaro, 2010)Ma.leonor Correa Gonzalez100% (4)

- English Drama Project ReportDocument9 pagesEnglish Drama Project Reportnala100% (1)

- Tower To The MoonDocument13 pagesTower To The MoonAngelene75% (4)

- RealismDocument39 pagesRealismAna VallsNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Lungit WawastionoDocument14 pagesJurnal Lungit WawastionoAllung SheinXyuNo ratings yet

- Rpaper The GuideDocument9 pagesRpaper The GuideKush ChaudhryNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study Between Northup's Narrative Slave "Twelve Years A Slave" and Its Adapted MovieDocument6 pagesComparative Study Between Northup's Narrative Slave "Twelve Years A Slave" and Its Adapted MoviebudiarmanNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER I Ecranization PDFDocument11 pagesCHAPTER I Ecranization PDFAllung SheinXyu100% (1)

- Modernist Fiction On ScreenDocument29 pagesModernist Fiction On ScreenElisa ScublaNo ratings yet

- Literature Versus FilmDocument10 pagesLiterature Versus FilmWish_HopeNo ratings yet

- Symmetry in Film PDFDocument4 pagesSymmetry in Film PDFTyrone TuohyNo ratings yet

- Ekranisasi Novel Sunshine Becomes You Ka Bb87ae8e PDFDocument9 pagesEkranisasi Novel Sunshine Becomes You Ka Bb87ae8e PDFAulia PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Howl's SlidesDocument7 pagesHowl's SlidesBlankgigNo ratings yet

- Literature in FilmsDocument37 pagesLiterature in FilmsVijay GoplaniNo ratings yet

- Passage TIDocument10 pagesPassage TImoin khanNo ratings yet

- 03 PrefaceDocument4 pages03 PrefaceAvani ShahNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument12 pagesReview of Related Literature and StudiesShannen Anne MalubayNo ratings yet

- Local Media3051422343527873709Document19 pagesLocal Media3051422343527873709Ayu KizanagiNo ratings yet

- The Film Essays Writing With The Movie CameraDocument5 pagesThe Film Essays Writing With The Movie CameraŞtefan-Adrian RusuNo ratings yet

- From Scottish' Play To Japanese Film: Kurosawa's Throne of BloodDocument11 pagesFrom Scottish' Play To Japanese Film: Kurosawa's Throne of BloodLuisNo ratings yet

- Adaptation For Animation - Transforming Literature Frame by FrameDocument473 pagesAdaptation For Animation - Transforming Literature Frame by FrameБогдан Быков100% (1)

- Week 1 Lecture NotesDocument7 pagesWeek 1 Lecture NotesClaudio BalboaNo ratings yet

- Why Do People Choose Watching Adaptations of English Literature Over Reading It?Document5 pagesWhy Do People Choose Watching Adaptations of English Literature Over Reading It?IJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan For Am Lit Film IntroDocument3 pagesLesson Plan For Am Lit Film IntroGian QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- Cary Fukunaga's Jane Eyre As A Re-Working of The Female GothicDocument61 pagesCary Fukunaga's Jane Eyre As A Re-Working of The Female GothicFryderyck ChopinNo ratings yet

- Literary Text in Multimedia PresentationDocument15 pagesLiterary Text in Multimedia PresentationsharonNo ratings yet

- Diexis in Red by Taylor SwiftDocument11 pagesDiexis in Red by Taylor SwiftNirmana ArtstikaNo ratings yet

- The Future Revisited: Jules Verne on Screen in 1950s AmericaFrom EverandThe Future Revisited: Jules Verne on Screen in 1950s AmericaNo ratings yet

- Suspense Formula Analysis in Kingsman The Secret Service 2014Document10 pagesSuspense Formula Analysis in Kingsman The Secret Service 2014lalalovegoodNo ratings yet

- Sense and Sensibility - Final PaperDocument48 pagesSense and Sensibility - Final PaperBeatriz Ilibio MoroNo ratings yet

- Scriptas Hypothesis AaltonenDocument20 pagesScriptas Hypothesis Aaltonenajohnny1No ratings yet

- 1.2 Literature and Motion PicturesDocument31 pages1.2 Literature and Motion PicturesBogles Paul FernandoNo ratings yet

- Film Poetry HistoricalDocument29 pagesFilm Poetry HistoricalblowupsNo ratings yet

- Masterpiece Fitc AdaptationDocument7 pagesMasterpiece Fitc AdaptationAniOrtizNo ratings yet

- 06 AbstractDocument7 pages06 AbstractAvani ShahNo ratings yet

- Bakalsk Prce UstkovDocument53 pagesBakalsk Prce Ustkovmoni hasanNo ratings yet

- TV NARRATIVES Pages From Narrative and MediaDocument19 pagesTV NARRATIVES Pages From Narrative and MediaBorbála IllésNo ratings yet

- SWALE 2020 Anime and The Conquest of TimeDocument21 pagesSWALE 2020 Anime and The Conquest of TimeSamuel WebsterNo ratings yet

- Representations of Architecture in JapanDocument58 pagesRepresentations of Architecture in JapanRobin MotmansNo ratings yet

- Language of Cinema Module-1 Language of Cinema: An Introduction Academic ScriptDocument11 pagesLanguage of Cinema Module-1 Language of Cinema: An Introduction Academic ScriptNaveen ReddyNo ratings yet

- Harry Ludens - Harry Potter and The Philosopher's Stone As A Novel and Computer GameDocument137 pagesHarry Ludens - Harry Potter and The Philosopher's Stone As A Novel and Computer GameAbhishek KaulNo ratings yet

- Representations of Architecture in Japanese Anime and MangaDocument58 pagesRepresentations of Architecture in Japanese Anime and Mangayanot leiNo ratings yet

- "Two Patersons" by Arseni MaximovDocument13 pages"Two Patersons" by Arseni MaximovArseni MaxNo ratings yet

- 2013 Ilha Do Desterro - UNSWORTH Copy 2Document34 pages2013 Ilha Do Desterro - UNSWORTH Copy 2Ariana V. LokerNo ratings yet

- Realism in The Animation Media Environment: Animation Theory From JapanDocument14 pagesRealism in The Animation Media Environment: Animation Theory From Japanjuan acuñaNo ratings yet

- The Presentation of Speech and Thought in Jane Austen's - Pride - GRINDocument14 pagesThe Presentation of Speech and Thought in Jane Austen's - Pride - GRINKazal BaruaNo ratings yet

- Józsa István - Kortárs Művészet: Immortal Literature: Film Adaptations and Interpretations of Oscar Wilde'SDocument19 pagesJózsa István - Kortárs Művészet: Immortal Literature: Film Adaptations and Interpretations of Oscar Wilde'SDeeJay MussexNo ratings yet

- Bollywoodising Literature Forging CinemaDocument16 pagesBollywoodising Literature Forging CinemajagiyaaNo ratings yet

- Code 9416-1Document32 pagesCode 9416-1junaid khanNo ratings yet

- Cavallaro, Dani - Anime and The Art of Adaptation - Eight Famous Works From Page To screen-McFarland & Co., Publishers (2010)Document221 pagesCavallaro, Dani - Anime and The Art of Adaptation - Eight Famous Works From Page To screen-McFarland & Co., Publishers (2010)HitomiNo ratings yet

- TasneemDocument8 pagesTasneemTasneem M. Rababa'hNo ratings yet

- ALMUHARDI DARWIN ISMA AsliDocument26 pagesALMUHARDI DARWIN ISMA Asliryza mauryzNo ratings yet

- Almuhardi Darwin Isma AsliDocument25 pagesAlmuhardi Darwin Isma Asliryza mauryzNo ratings yet

- Adaptation of Novels Into Film-A Comprehensive New Framework For Media Consumers and Those Who Serve ThemDocument75 pagesAdaptation of Novels Into Film-A Comprehensive New Framework For Media Consumers and Those Who Serve ThemAnavrin AivilNo ratings yet

- Esharp Is An International Online Journal For Postgraduate Research in The ArtsDocument18 pagesEsharp Is An International Online Journal For Postgraduate Research in The ArtsXander ClockNo ratings yet

- Ecranization Trends and Their Effects in The World of Indonesian Literature - Izdiharti HusniyahDocument3 pagesEcranization Trends and Their Effects in The World of Indonesian Literature - Izdiharti HusniyahNina BunyaminNo ratings yet

- Buku Ajar ProseDocument36 pagesBuku Ajar Prosefitrawati100% (1)

- Media and Information Langauges (Part 1) Genre, Codes, and ConventionsDocument3 pagesMedia and Information Langauges (Part 1) Genre, Codes, and ConventionsMaster NistroNo ratings yet

- Summary of "A Midsummer Night's Dream"Document4 pagesSummary of "A Midsummer Night's Dream"Việt Anh Nguyễn ThịNo ratings yet

- Classical Mechanics, Prentice Hall, 1991, 1991: DownloadDocument35 pagesClassical Mechanics, Prentice Hall, 1991, 1991: DownloadVineet Chauhan0% (1)

- DocumentDocument7 pagesDocumentBe AwakeNo ratings yet

- Chapter One: The NurseryDocument8 pagesChapter One: The NurseryJuan Camilo Durango GarciaNo ratings yet

- Destination B2 GRAMMARDocument84 pagesDestination B2 GRAMMARRyeetNo ratings yet

- The Power of Sympathy: American Literature IsDocument2 pagesThe Power of Sympathy: American Literature IsNabeelBhattiNo ratings yet

- Eve of Chaos: A Group Quest by PhoenixDocument14 pagesEve of Chaos: A Group Quest by PhoenixHNo ratings yet

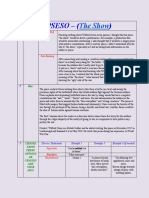

- Example, The Show TPSESO AnalysisDocument4 pagesExample, The Show TPSESO AnalysisAANo ratings yet

- Peter Pan and Captain HookDocument1 pagePeter Pan and Captain HookAchaa GurawidjajaNo ratings yet

- The White TigerDocument10 pagesThe White TigerKarthikeyan SNo ratings yet

- TFR PDF CG 5E FINAL v2 (PDF SAMPLE) PDFDocument54 pagesTFR PDF CG 5E FINAL v2 (PDF SAMPLE) PDFjuanbv100% (3)

- The Prisoner of Zenda ch.123Document4 pagesThe Prisoner of Zenda ch.123Shaimaa HabibNo ratings yet

- Red Chief QDocument4 pagesRed Chief QeNo ratings yet

- PitestiDocument17 pagesPitestiElenushChiriacNo ratings yet

- Activity in Excel Santos, Kristel JoyDocument24 pagesActivity in Excel Santos, Kristel JoyKristel Joy SantosNo ratings yet

- Game Character Design MasterDocument564 pagesGame Character Design MasterАнтон АлександровNo ratings yet

- Elf Acceptanct LetterDocument1 pageElf Acceptanct LetterJenniferLeeNo ratings yet

- East Asian LiteratureDocument12 pagesEast Asian LiteratureEllaine joy DariaNo ratings yet

- Story of An Hour 1Document4 pagesStory of An Hour 1emysameh100% (1)

- Find The Perfect Editor For Your Next Book: Reedsy (/)Document11 pagesFind The Perfect Editor For Your Next Book: Reedsy (/)Clevertough GalvanNo ratings yet

- SOME WAYS OF STUDYING LITERATURE by UffaqDocument4 pagesSOME WAYS OF STUDYING LITERATURE by UffaqKhurram MalikNo ratings yet

- Literary AnalysisDocument2 pagesLiterary AnalysisErika AlmogueraNo ratings yet

- Presentation Lord of The FliesDocument8 pagesPresentation Lord of The FliesJan NovákNo ratings yet

- 21st CenturyDocument31 pages21st CenturyAlthea CorpuzNo ratings yet

- F. Scott Fitzgerald's Unique Literary and Writing StyleDocument9 pagesF. Scott Fitzgerald's Unique Literary and Writing StyleАлена ЛебедеваNo ratings yet

- Candlekeep MysteriesDocument227 pagesCandlekeep MysteriesEric H.33% (3)