Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Seminario 7 Ovariohysterectomy Versus Ovariectomy For Elective Sterilization

Seminario 7 Ovariohysterectomy Versus Ovariectomy For Elective Sterilization

Uploaded by

Hello pandi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views4 pagesThis document discusses the surgical techniques and potential benefits and risks of ovariohysterectomy (removal of ovaries and uterus) versus ovariectomy (removal of ovaries alone) for electing sterilization of female dogs and cats. Ovariohysterectomy has historically been more common in the US and Canada but ovariectomy is becoming more standard in Europe. Studies show ovariectomy has smaller incisions and less tissue handling, which may result in fewer complications and less pain. Both procedures appear to have similar surgery times and complication rates. Ovariectomy eliminates risks of vaginal bleeding but increases risk of ovarian remnant syndrome, while ovariohysterectomy provides greater reduction in mammary tumors but risks include intra-abdominal bleeding.

Original Description:

Original Title

Seminario 7 Ovariohysterectomy Versus Ovariectomy for Elective Sterilization

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses the surgical techniques and potential benefits and risks of ovariohysterectomy (removal of ovaries and uterus) versus ovariectomy (removal of ovaries alone) for electing sterilization of female dogs and cats. Ovariohysterectomy has historically been more common in the US and Canada but ovariectomy is becoming more standard in Europe. Studies show ovariectomy has smaller incisions and less tissue handling, which may result in fewer complications and less pain. Both procedures appear to have similar surgery times and complication rates. Ovariectomy eliminates risks of vaginal bleeding but increases risk of ovarian remnant syndrome, while ovariohysterectomy provides greater reduction in mammary tumors but risks include intra-abdominal bleeding.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views4 pagesSeminario 7 Ovariohysterectomy Versus Ovariectomy For Elective Sterilization

Seminario 7 Ovariohysterectomy Versus Ovariectomy For Elective Sterilization

Uploaded by

Hello pandiThis document discusses the surgical techniques and potential benefits and risks of ovariohysterectomy (removal of ovaries and uterus) versus ovariectomy (removal of ovaries alone) for electing sterilization of female dogs and cats. Ovariohysterectomy has historically been more common in the US and Canada but ovariectomy is becoming more standard in Europe. Studies show ovariectomy has smaller incisions and less tissue handling, which may result in fewer complications and less pain. Both procedures appear to have similar surgery times and complication rates. Ovariectomy eliminates risks of vaginal bleeding but increases risk of ovarian remnant syndrome, while ovariohysterectomy provides greater reduction in mammary tumors but risks include intra-abdominal bleeding.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 4

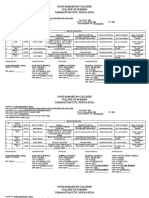

Commentary

Ovariohysterectomy versus ovariectomy

for elective sterilization of female dogs and cats:

is removal of the uterus necessary?

Michael DeTora, dvm, and Robert J. McCarthy, dvm, ms, dacvs

E lective sterilization of female dogs and cats is one

of the most common procedures performed in vet-

erinary practice and is considered by private veterinary

incisions are considerably smaller and located more

cranially with ovariectomy, compared with ovario-

hysterectomy.9 In one study,9 for instance, mean skin

practitioners as one of the most important skills required incision length was 19.8% of the manubrium-to-pubic

of new graduates.1,2 Potential benefits of sterilization in- brim distance in dogs undergoing ovariectomy and

clude population control, prevention of diseases of the 23.8% in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy. Mean

reproductive tract, and elimination of undesirable be- fascia incision length was 17.7% of the manubrium-to-

haviors associated with hormonal cycling. The AVMA3 pubic brim distance in dogs undergoing ovariectomy

and the Association of Shelter Veterinarians4 both pro- and 21.3% in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy. The

mote elective sterilization of female dogs and cats as in- suspensory ligament must be broken down with either

tegral to reducing euthanasia of unwanted dogs and cats. procedure to allow identification of the ovaries, and with

Sterilization of female dogs and cats can be ac- both procedures, the ovarian pedicles are ligated and

complished by removing both the ovaries and uterus severed. With ovariohysterectomy, however, the uterine

(ovariohysterectomy) or by removing the ovaries alone vessels are also ligated and the uterus is crushed and sev-

(ovariectomy). Ovariohysterectomy has historically ered. Surgery time is approximately the same for both

been recommended in the United States and Canada and ovariohysterectomy and ovariectomy, and it is likely that

is currently emphasized at schools and colleges of vet- with experience, each procedure is of equal technical dif-

erinary medicine in these countries. To our knowledge, ficulty.9 Minimally invasive surgical techniques are being

only one of the most frequently used surgical textbooks used with increasing frequency for elective sterilization

in the United States and Canada describes ovariectomy,5 of female dogs, and it is the authors’ opinion that ovari-

and ovariectomy is generally not taught to veterinary ectomy is easier to perform than ovariohysterectomy

students during their surgical laboratories. The Clinical with these techniques.

Proficiency Examination, which is the final step in the

Educational Commission for Foreign Veterinary Gradu- Signs of Pain

ates’ program for establishing the educational equiva-

lence of graduates of nonaccredited veterinary schools A recent prospective clinical trial9 compared signs

seeking licensure in the United States or Canada, re- of pain in dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy or

quires “complete removal of both ovaries and removal ovariectomy. Scores for the Glasgow composite mea-

of the majority of the uterus” to obtain a passing grade.6 sure pain scale were not significantly different between

Despite the apparent preference for ovariohyster- groups, and rescue analgesia was not required for any

ectomy in the United States and Canada, ovariectomy dog. However, all dogs were premedicated with carpro-

appears to have become the standard of care in many fen prior to surgery and received buprenorphine for

European countries.7 In addition, with the develop- the first 24 hours after surgery and carprofen thereaf-

ment of minimally invasive surgical techniques, laparo- ter, which might have masked any differences that may

scopic ovariectomy has gained popularity.8 Thus, it may have existed. Studies10–13 comparing laparoscopic with

be helpful to review the scientific evidence comparing open sterilization techniques have generally identified

ovariohysterectomy and ovariectomy for elective steril- fewer and less severe signs of pain in dogs undergo-

ization of healthy female dogs and cats. ing laparoscopic procedures, possibly as a result of the

smaller incision and decreased tissue handling associat-

Surgical Technique ed with laparoscopic techniques, compared with open

techniques.

Ovariohysterectomy and ovariectomy involve simi-

lar surgical techniques, except that the skin and fascia Complications

From the Department of Clinical Sciences, Cummings School of Vet- Surgical complication rates associated with ovario-

erinary Medicine, Tufts University, North Grafton, MA 01536. hysterectomy in healthy dogs and cats have been re-

Address correspondence to Dr. McCarthy (Rob.McCarthy@tufts.edu). ported to range from 6.2% to 20.6%, depending on sur-

JAVMA, Vol 239, No. 11, December 1, 2011 Views: Commentary 1409

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 07/24/23 09:04 PM UTC

geon experience.14,15 Most complications are mild and compared the incidence of ORS in dogs that have un-

generally consist of incisional inflammation or gastro- dergone ovariohysterectomy versus ovariectomy, but

intestinal tract upset. Incisional complications are more it has been suggested that ORS would be less likely to

common in larger animals and animals with longer sur- develop after ovariectomy because the more cranial lo-

gery and anesthesia times.15 Although the overall com- cation of the incision may allow better exposure of the

plication rate after ovariectomy has not been evaluated ovarian pedicle.7

in a large group of animals, no difference in surgery

time or wound scores was noted in a small prospec- Mammary Gland Tumors

tive study9 in which ovariohysterectomy was compared

with ovariectomy. An important time-dependent benefit of elective

sterilization in female dogs is a decreased incidence

Intra-abdominal hemorrhage during or after sur-

of mammary gland tumors. Mammary gland tumors

gery has been reported in 6.4% to 20% of dogs under-

are the most common tumors in female dogs, with an

going ovariohysterectomy, most often in dogs weighing

overall incidence of 3.4%; 41% to 53% of mammary

> 22.7 kg (49.9 lb) and in procedures performed by

gland tumors are reportedly malignant, and metastasis

inexperienced surgeons.7,15,16 Bleeding occurs most fre-

is common.21–24 The relative risk for malignant mam-

quently from the right ovarian pedicle but may also oc-

mary gland tumor development in dogs sterilized be-

cur from the left ovarian pedicle, broad ligament, uter-

fore the first estrus is 0.5%, compared with the risk in

ine arteries, uterine stump, or body wall. The incidence

sexually intact dogs. Dogs sterilized between the first

of intra-abdominal hemorrhage with ovariectomy has

and second estrus have a relative risk of 8%, and dogs

not been reported, but it has been theorized that bleed-

sterilized between the second and third estrus have a

ing may be less likely because only the ovarian pedicles

relative risk of 26%.22 There is no documented ben-

are potential sources of blood loss.7,9 With either pro-

eficial effect of sterilization on development of ma-

cedure, severe life-threatening hemorrhage is rare.15,16

lignant mammary gland tumors after the third estrus.

Vaginal bleeding, reported in up to 15% of dogs that

The development of mammary gland tumors in dogs

undergo ovariohysterectomy, would not be expected

appears to be hormone dependent, although an exact

to occur after ovariectomy because ligatures are placed

cause-and-effect relationship between neuter status

around the proper ligament of the ovary, leaving the se-

and mammary gland neoplasia has not been identi-

rosal surface of the uterine horns intact.7,17

fied.21 Sterilization by either ovariohysterectomy or

Inadvertent ligation of a ureter is an uncommon ovariectomy in a time-dependent fashion can largely

but potentially severe complication of either ovario- eliminate the risk that mammary gland tumors will

hysterectomy or ovariectomy. Ligation can occur proxi- develop in dogs.

mally in association with ligation of the ovarian pedicle

or distally in association with ligation of the uterine

stump.18 It has been suggested that ligation of the distal Uterine Abnormalities

portion of the ureter is more likely to occur because of Ovariohysterectomy, rather than ovariectomy, is of-

its intraperitoneal location and close proximity to the ten advocated for female dogs and cats because of the

uterine body.7 Ligation of the distal portion of the ure- presumed potential for uterine abnormalities to devel-

ter would not be expected with ovariectomy because all op in animals in which the uterus is not removed. The

ligatures are placed in close association with the ovary. most commonly cited abnormalities in this regard in-

Excessive inflammation and granuloma formation, clude cystic endometrial hyperplasia (CEH)–pyometra

manifested clinically as a draining fistulous tract, can complex and uterine neoplasia.

occur after either ovariohysterectomy or ovariectomy.

In general, this complication is associated with exces- CEH-pyometra complexCystic endometrial

sive tissue trauma, poor aseptic technique, and the use hyperplasia–pyometra complex is a condition that oc-

of braided nonabsorbable suture material. Granuloma curs secondary to chronic hormone influence on the

formation can occur at either the ovarian pedicle or uterus.25,26 The exact pathophysiology of CEH-pyome-

uterine stump after ovariohysterectomy but is more tra complex is not completely understood, but current

frequently identified at the uterine stump.17–19 Granulo- theory suggests that progesterone priming of uterine

mas would be expected to occur only at the site of the tissue leads to a suppressed immune system, closure of

ovarian pedicle following ovariectomy. the cervix, stimulation of endometrial secretions, and

Ovarian remnant syndrome (ORS) is a disorder development of CEH. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia

characterized by clinical signs related to functional re- allows ascending opportunistic pathogens (most fre-

sidual ovarian tissue after ovariohysterectomy or ovari- quently Escherichia coli) to cause infection and pyome-

ectomy. To our knowledge, no studies have reported tra.25,26 All dogs with an intact uterus are expected to

identifying ectopic ovarian tissue in dogs; therefore, develop CEH with age, but not all dogs with CEH will

ORS is considered to exclusively be a result of func- go on to develop pyometra.

tional tissue remaining after surgery. Retrospective Regardless of the exact pathophysiology of the

studies17,19 indicate that ORS represents 17% to 43% of CEH-pyometra complex, it is clear that it requires a

all complications after ovariohysterectomy and is more source of progesterone, so it is not expected to occur

common with inexperienced surgeons. Dogs have a after complete removal of the ovaries. In a previous

higher likelihood of developing ORS, compared with study,27 a questionnaire was administered to the own-

cats, and the right ovary is more likely to be involved ers of 135 dogs (69 that had undergone ovariectomy

because of its more cranial location.20 No studies have and 66 that had undergone ovariohysterectomy) eight

1410 Views: Commentary JAVMA, Vol 239, No. 11, December 1, 2011

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 07/24/23 09:04 PM UTC

to 11 years after surgery, and none of the dogs had de- Conclusion

veloped signs of CEH-pyometra complex. In another

study,28 bilateral flank ovariectomy was performed in We do not believe that there is any scientific evi-

72 dogs, and no episodes of pyometra were identified dence for the preferential teaching of ovariohysterec-

after six to 10 years of follow-up. Potentially, pyometra tomy instead of ovariectomy by schools and colleges of

could occur after ovariectomy if exogenous progester- veterinary medicine in the United States and Canada,

ones are administered, but there are currently no dis- and it is our view that ovariectomy provides an equally

eases for which the use of these substances is recom- effective technique for elective sterilization of female

mended. Stump pyometra, often cited as an example of dogs and cats, with no recognized disadvantages. Po-

how pyometra can occur in the absence of the ovaries, tential advantages of ovariectomy include a smaller in-

has only been reported in association with ORS, break- cision, better viewing of the ovarian pedicle, and pos-

age in aseptic technique, or exogenous progesterone sibly less risk of complications associated with surgical

administration.7,29–31 manipulation of the uterus.

Uterine neoplasiaPrimary uterine tumors in References

dogs are rare, and almost all are benign leiomyomas.32–36

In a survey of the incidence of neoplasia in dogs, only 1. Greenfield CL, Johnson AL, Schaeffer DJ. Frequency of use of

various procedures, skills, and areas of knowledge among veter-

11 of 33,570 female dogs had a tumor of the uterus inarians in private small animal exclusive or predominant prac-

and only one had a malignant uterine tumor.32 An- tice and proficiency expected of new veterinary school gradu-

other study35 identified nine dogs with uterine or ates. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004;224:1780–1787.

cervical tumors among 2,361 dogs with neoplasia. Fi- 2. Stockner PK. The economics of spaying and neutering: market

nally, postmortem histologic evaluation of the genital forces and owners’ values affecting pet population control. J Am

tracts of 300 mixed-breed female dogs identified a Vet Med Assoc 1991;198:1180–1182.

3. AVMA. Why you should spay or neuter your pet. Available at: www.

single primary uterine tumor.33 On the basis of re- avma.org/myveterinarian/spay_neuter.asp. Accessed Jul 23, 2011.

sults of these studies, it has been calculated that the 4. Looney A, Bohling W, Bushby P, et al. The Association of Shelter

true overall incidence of malignant uterine neopla- Veterinarians veterinary medical care guidelines for spay-neuter

sia in dogs is approximately 0.003%.7 Leiomyomas programs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;233:74–86.

of the uterus are generally regarded as noninvasive, 5. Stone EA. Ovary and uterus. In: Slatter D, ed. Textbook of

nonmetastatic, and slow growing, with hysterectomy small animal surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Science,

2003;1487–1496.

almost always curative. 6. Educational Commission for Foreign Veterinary Graduates.

To our knowledge, uterine neoplasia has never Clinical proficiency examination instructors guidelines. Schaum-

been reported in a dog that has had its ovaries re- burg, Ill: AVMA, 2010.

moved before 2 years of age, regardless of whether the 7. Van Goethem B, Schaefers-Okkens A, Kirpensteijn J. Making a

uterus was left in situ. This would suggest a strong rational choice between ovariectomy and ovariohysterectomy in

hormonal influence on the development of these tu- the dog: a discussion of the benefits of either technique. Vet Surg

2006;35:136–143.

mors and a sparing effect of any technique that re- 8. Gower S, Mayhew P. Canine laparoscopic and laparoscopic-

moves the ovaries.32,34,35 assisted ovariohysterectomy and ovariectomy. Compend Contin

Educ Pract Vet 2008;30:430–440.

Urinary Sphincter Mechanism Incontinence 9. Peeters ME, Kirpensteijn J. Comparison of surgical variables

and short-term postoperative complications in healthy dogs

Urinary sphincter mechanism incontinence (USMI) undergoing ovariohysterectomy or ovariectomy. J Am Vet Med

reportedly occurs in 4.9% to 20.0% of sterilized female Assoc 2011;238:189–194.

10. Culp WTN, Mayhew PD, Brown DC. The effect of laparoscopic

dogs, compared with 0.2% to 1.0% of sexually intact versus open ovariectomy on postsurgical activity in small dogs.

female dogs.7,21,37–39 Large-breed and giant-breed dogs Vet Surg 2009;38:811–817.

and dogs that undergo gonadectomy at an earlier age 11. Devitt CM, Cox RE, Hailey JJ. Duration, complications, stress,

appear to have a higher risk of developing USMI. In a and pain of open ovariohysterectomy versus a simple method of

retrospective study40 evaluating the long-term effects of laparoscopic-assisted ovariohysterectomy in dogs. J Am Vet Med

gonadectomy at an early age, dogs were significantly Assoc 2005;227:921–927.

12. Hancock RB, Lanz OI, Waldron DR, et al. Comparison of post-

more likely to develop USMI if spayed before 3 months operative pain after ovariohysterectomy by harmonic scalpel-

of age. The corresponding projected cumulative inci- assisted laparoscopy compared with median celiotomy and liga-

dence during the first 6 years of age (when most signs tion in dogs. Vet Surg 2005;34:273–282.

of incontinence are identified) was 12.9% for female 13. Davidson EB, Moll HD, Payton ME. Comparison of laparoscop-

dogs spayed before 3 months of age and 5.0% for female ic ovariohysterectomy and ovariohysterectomy in dogs. Vet Surg

dogs spayed at or after 3 months of age.40 2004;33:62–69.

14. Pollari FL, Bonnett BN, Bamsey SC, et al. Postoperative com-

Although the underlying mechanism of USMI is plications of elective surgeries in dogs and cats determined by

poorly understood, the importance of estrogen influ- examining electronic and paper medical records. J Am Vet Med

ence is not debated. Therefore, the incidence of USMI Assoc 1996;208:1882–1886.

should not differ regardless of whether the uterus is re- 15. Burrow R, Batchelor D, Cripps P. Complications observed dur-

moved. In one study,27 six of 69 (8.7%) dogs developed ing and after ovariohysterectomy of 142 bitches at a veterinary

USMI after ovariectomy, compared with nine of 66 teaching hospital. Vet Rec 2005;157:829–833.

16. Berzon JL. Complications of elective ovariohysterectomies in

(13.6%) after ovariohysterectomy. In other studies,7,38 the dog and the cat at a teaching institution: clinical review of

54 of 260 (20.8%) dogs undergoing ovariectomy and 29 853 cases. Vet Surg 1979;8:89–91.

of 152 (19.1%) dogs undergoing ovariohysterectomy 17. Pearson H. The complications of ovariohysterectomy in the

developed USMI after surgery. bitch. J Small Anim Pract 1973;14:257–266.

JAVMA, Vol 239, No. 11, December 1, 2011 Views: Commentary 1411

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 07/24/23 09:04 PM UTC

18. Okkens AC, van de Gaag I, Biewenga WJ, et al. Urological com-

plications following ovariohysterectomy in dogs [in Dutch]. Ti-

jdschr Diergeneeskd 1981;106:1189–1198.

19. Okkens AC, Dieleman SJ, van de Gaag I. Gynaecological compli-

cations following ovariohysterectomy in dogs, due to: (1) partial

removal of the ovaries. (2) inflammation of the uterocervical

stump [in Dutch]. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd 1981;106:1142–1158.

20. Ball RL, Birchard SJ, May LR, et al. Ovarian remnant syndrome

in dogs and cats: 21 cases (2000–2007). J Am Vet Med Assoc

2010;236:548–553.

21. Kustritz M. Determining the optimal age for gonadectomy of

dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2007;231:1665–1675.

22. Schneider R, Dorn CR, Taylor DON. Factors influencing canine

mammary cancer development and postsurgical survival. J Natl

Cancer Inst 1969;43:1249–1261.

23. Lana SE, Rutteman GR, Withrow SJ. Tumors of the mammary

gland. In: Withrow SJ, Vail D, eds. Small animal clinical oncol-

ogy. 4th ed. St Louis: Elsevier Science, 2007;619–633.

24. Moulton JE, Rosenblatt LS, Goldman M. Mammary tumors in a

colony of Beagle dogs. Vet Pathol 1986;23:741–749.

25. Verstegen J, Dhaliwal G, Verstegen-Onclin K. Mucometra, cystic

endometrial hyperplasia, and pyometra in the bitch: advances in

treatment and assessment of future reproductive success. The-

riogenology 2008;70:364–374.

26. Smith FO. Canine pyometra. Theriogenology 2006;66:610–612.

27. Okkens AC, Kooistra HS, Nickel RF. Comparison of long-term

effects of ovariectomy versus ovariohysterectomy in bitches.

J Reprod Fertil Suppl 1997;51:227–231.

28. Janssens LA, Janssens GH. Bilateral flank ovariectomy in the

dog—surgical technique and sequelae in 72 animals. J Small

Anim Pract 1991;32:249–252.

29. Wallace MS. The ovarian remnant syndrome in the bitch and

queen. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1991;21:501–507.

30. Miller DM. Ovarian remnant syndrome in dogs and cats: 46

cases (1988–1992). J Vet Diagn Invest 1995;7:572–574.

31. Musal B, Tuna B. Surgical therapy of complicated uterine

stump pyometra in five bitches: a case report. Vet Med (Praha)

2005;12:558–562.

32. Brodey RS, Roszel JF. Neoplasms of the canine uterus, vagina

and vulva: a clinicopathologic survey of 90 cases. J Am Vet Med

Assoc 1967;151:1294–1307.

33. Ortega-Pacheco A, Segura-Correa JC, Jimenez-Coello M, et al.

Reproductive patterns and reproductive pathologies of stray

bitches in the tropics. Theriogenology 2007;67:382–390.

34. Reichler IM. Gonadectomy in cats and dogs: a review of risks

and benefits. Reprod Dom Anim 2009;44:29–35.

35. Cotchin E. Neoplasia in the dog. Vet Rec 1954;66:879–888.

36. Klein MK. Tumors of the female reproductive system. In: Withrow

S, Vail D, eds. Small animal clinical oncology. 4th ed. St Louis: Else-

vier Science, 2007;613–614.

37. Arnold S, Hubler M, Reichler I. Urinary incontinence in spayed

bitches: new insights into the pathophysiology and options for

medical treatment. Reprod Dom Anim 2009;44(suppl 2):190–

192.

38. Arnold S, Arnold P, Hubler M, et al. Urinary incontinence in

spayed bitches: prevalence and breed predisposition [in Ger-

man]. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 1989;131:259–263.

39. Thrusfield MV. Associations between urinary incontinence and

spaying in bitches. Vet Rec 1985;116:695.

40. Spain CV, Scarlett JM, Houpt KA. Long-term risks and

benefits of early-age gonadectomy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc

2004;224:380–387.

1412 Views: Commentary JAVMA, Vol 239, No. 11, December 1, 2011

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 07/24/23 09:04 PM UTC

You might also like

- Nursing Care of Male and Female Clients With General and Specific Problems in SexualityDocument22 pagesNursing Care of Male and Female Clients With General and Specific Problems in SexualityDecere PascualNo ratings yet

- Oh No, It's A Big Fat Bitch SpayDocument8 pagesOh No, It's A Big Fat Bitch SpayWilliam Chandler100% (1)

- (Ebookobgyne - Net) Diagnostic Imaging Gynecology, 2ndDocument948 pages(Ebookobgyne - Net) Diagnostic Imaging Gynecology, 2ndJessica Ugalde Mata100% (5)

- Theriogenology Volume 66 Issue 3 2006 (Doi 10.1016 - J.theriogenology.2006.04.005) Lisa M. Howe - Surgical Methods of Contraception and SterilizationDocument10 pagesTheriogenology Volume 66 Issue 3 2006 (Doi 10.1016 - J.theriogenology.2006.04.005) Lisa M. Howe - Surgical Methods of Contraception and SterilizationMark Afandy Fitrah MNo ratings yet

- Via Module NicprDocument16 pagesVia Module Nicprpedjoang fkupr2017No ratings yet

- Assignment On MenopauseDocument13 pagesAssignment On MenopauseRashmi C S100% (2)

- Feline Mammary Tumors Hayes1985Document8 pagesFeline Mammary Tumors Hayes1985MicheleBerselliNo ratings yet

- Rangkuman TeratomaDocument22 pagesRangkuman TeratomaFelicia Fernanda IskandarNo ratings yet

- Ovariectomia Vs OvariohisterectomiaDocument5 pagesOvariectomia Vs OvariohisterectomiaRicardo CaveroNo ratings yet

- Rootk001@umn - Edu: CVM 6949: Comparative Theriogenology Small Animal Course NotesDocument5 pagesRootk001@umn - Edu: CVM 6949: Comparative Theriogenology Small Animal Course NotesPrakash JNo ratings yet

- Complications of Ovariohysterectomy and Orchiectomy in Companion AnimalsDocument17 pagesComplications of Ovariohysterectomy and Orchiectomy in Companion AnimalsCarolina Soler GómezNo ratings yet

- Effect of Spaying and Timing of Spaying On Survival On Dogs With Mammary CarcinomaDocument4 pagesEffect of Spaying and Timing of Spaying On Survival On Dogs With Mammary CarcinomaSebastian MatamalaNo ratings yet

- Top 5 Complications of GonadectomyDocument7 pagesTop 5 Complications of GonadectomyCabinet VeterinarNo ratings yet

- Committee Opinion: Salpingectomy For Ovarian Cancer PreventionDocument3 pagesCommittee Opinion: Salpingectomy For Ovarian Cancer Preventionw y0% (1)

- TVP 2022 0708 - OvariohysterectomyDocument9 pagesTVP 2022 0708 - Ovariohysterectomysimon alfaro gonzálezNo ratings yet

- Current Diagnosis and Management of Ovarian Cysts: Review ArticlesDocument4 pagesCurrent Diagnosis and Management of Ovarian Cysts: Review ArticlesFelNo ratings yet

- Cesárea CerdosDocument6 pagesCesárea CerdosViviana RuedaNo ratings yet

- Management of Ovarian EndometriomaDocument13 pagesManagement of Ovarian EndometriomaAghnia PutriNo ratings yet

- Single Incision, Laparoscopic-Assisted Ovariohysterectomy For Mucometra and Pyometra in DogsDocument5 pagesSingle Incision, Laparoscopic-Assisted Ovariohysterectomy For Mucometra and Pyometra in Dogsalfi fadilah alfidruNo ratings yet

- Bibliography: Surgery of The Reproductive TractDocument1 pageBibliography: Surgery of The Reproductive TractsalwaNo ratings yet

- Ovariohysterectomy: Preoperative ManagementDocument1 pageOvariohysterectomy: Preoperative ManagementsalwaNo ratings yet

- Final Version Surgery AssignmentDocument28 pagesFinal Version Surgery AssignmentAyele AsefaNo ratings yet

- Examining Indicators of Early Menopause FollowingDocument11 pagesExamining Indicators of Early Menopause FollowingDanielle VNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2018Document9 pagesJurnal 2018aulNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Knowledge and Management Practices of Hypertension in Establishing A Threshold For Endometrial SamplingDocument8 pagesA Study On The Knowledge and Management Practices of Hypertension in Establishing A Threshold For Endometrial SamplingGregNo ratings yet

- Reichler-2009-Reproduction in Domestic AnimalsDocument7 pagesReichler-2009-Reproduction in Domestic AnimalsMarcelle FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Flank and Midline Approaches To OvarDocument6 pagesComparison of Flank and Midline Approaches To Ovartrisnaput3No ratings yet

- Ovarian Masses: Surgery or Surveillance?Document9 pagesOvarian Masses: Surgery or Surveillance?MutianbllNo ratings yet

- Pathol Vet 1970 Moulton 289 320Document33 pagesPathol Vet 1970 Moulton 289 320Moldovan Nicolae-AndreiNo ratings yet

- Problems and Clinical Challenges: Feline ReproductionDocument8 pagesProblems and Clinical Challenges: Feline ReproductiondpcamposhNo ratings yet

- Art 20177509Document4 pagesArt 20177509Jashashree SaikiaNo ratings yet

- OHT Flank ApproachDocument6 pagesOHT Flank ApproachMarinaJiménezNo ratings yet

- Ovarian Cysts - A ReviewDocument7 pagesOvarian Cysts - A RevieweeeeeeNo ratings yet

- Practice Bulletin: Management of Adnexal MassesDocument14 pagesPractice Bulletin: Management of Adnexal MassesDasha VeeNo ratings yet

- Common Gynecologic ProceduresDocument55 pagesCommon Gynecologic ProceduresQurrataini IbanezNo ratings yet

- Updateon OvariohysterecomtyDocument9 pagesUpdateon Ovariohysterecomtysimon alfaro gonzálezNo ratings yet

- 2023 1840 OnlinePDFDocument7 pages2023 1840 OnlinePDFjuhiNo ratings yet

- ArticuloDocument6 pagesArticuloadrianarocio57No ratings yet

- Just The Berries: Who Needs An Endometrial Biopsy?Document3 pagesJust The Berries: Who Needs An Endometrial Biopsy?Azzhr FahNo ratings yet

- Cases Journal: Torsion of Ovarian Cyst During Pregnancy: A Case ReportDocument3 pagesCases Journal: Torsion of Ovarian Cyst During Pregnancy: A Case ReportAde Gustina SiahaanNo ratings yet

- Complicações Associadas À Ovariosalpingohisterectomia Eletiva Realizada Com Abraçadeira de Náilon Como Método de HemostasiaDocument5 pagesComplicações Associadas À Ovariosalpingohisterectomia Eletiva Realizada Com Abraçadeira de Náilon Como Método de HemostasiaDuarte SiamesNo ratings yet

- A Study To Determine Association of Ovarian Morphology With Endometrial Morphology and Postmenopausal BleedingDocument7 pagesA Study To Determine Association of Ovarian Morphology With Endometrial Morphology and Postmenopausal Bleedingmadhu chaturvediNo ratings yet

- Ca OvarioDocument13 pagesCa OvarioDaniel MálagaNo ratings yet

- Rectovaginal Fistulae: Bidhan Das, MD Michael Snyder, MDDocument7 pagesRectovaginal Fistulae: Bidhan Das, MD Michael Snyder, MDNovaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Medical Case ReportsDocument4 pagesJournal of Medical Case ReportsAna Di JayaNo ratings yet

- Rodent OncologyDocument24 pagesRodent Oncology黃皓No ratings yet

- SMJ 56 E134Document3 pagesSMJ 56 E134tyasNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Tools in ObgynDocument27 pagesDiagnostic Tools in ObgynHenok Y KebedeNo ratings yet

- Intl J Gynecology Obste - 2018 - Berek - Cancer of The Ovary Fallopian Tube and PeritoneumDocument20 pagesIntl J Gynecology Obste - 2018 - Berek - Cancer of The Ovary Fallopian Tube and PeritoneumHưng Nguyễn - Yola T.A.No ratings yet

- Ijcem0007 1366Document4 pagesIjcem0007 1366Ratih Kusuma DewiNo ratings yet

- Selective Vs Routine Midline Episiotomy For The PRDocument4 pagesSelective Vs Routine Midline Episiotomy For The PRIriawan Indra PutraNo ratings yet

- Ovarian Torsion in Pregnancy A Case ReportDocument3 pagesOvarian Torsion in Pregnancy A Case ReportCakraEkkyNo ratings yet

- Mokmedical Thermal AblationDocument12 pagesMokmedical Thermal AblationWilliam MookNo ratings yet

- Persistent Vulvar Hemorrhage Secondary To Vaginal Hemangioma in DogsDocument4 pagesPersistent Vulvar Hemorrhage Secondary To Vaginal Hemangioma in DogsFlaviu TabaranNo ratings yet

- Colic Surgery Recent Upda - 2023 - Veterinary Clinics of North America EquineDocument14 pagesColic Surgery Recent Upda - 2023 - Veterinary Clinics of North America EquinediazsunshineNo ratings yet

- 1343-Texto Del Artículo-3585-2-10-20180815Document8 pages1343-Texto Del Artículo-3585-2-10-20180815Gianella Zavala GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Outcome in Dogs Undergoing Adrenalectomy For Small Adrenal Gland Tumours Without Vascular InvasionDocument8 pagesOutcome in Dogs Undergoing Adrenalectomy For Small Adrenal Gland Tumours Without Vascular InvasionEquilibrium EduardoNo ratings yet

- Tinjauan Pustaka Agenesis UteriDocument2 pagesTinjauan Pustaka Agenesis UteriMaulana DimasNo ratings yet

- Endometriosis Surgical Treatment of Endometrioma Sep 2012Document8 pagesEndometriosis Surgical Treatment of Endometrioma Sep 2012Lina E. ArangoNo ratings yet

- Mammary CarcinomaDocument6 pagesMammary Carcinomapand00raNo ratings yet

- Theranekron For Treatment of Endometriosis in A Rat Model ComparedDocument5 pagesTheranekron For Treatment of Endometriosis in A Rat Model ComparedCat SkullNo ratings yet

- Borderline Ovarian TumoursDocument8 pagesBorderline Ovarian Tumoursuswatun khasanahNo ratings yet

- Gynecology: Three Minimally Invasive Procedures You Need to Know About For: Permanent Birth Control, Heavy Menstrual Periods, Accidental Loss of Urine Plus: Modern Hormone Therapy for the Post Menopausal WomenFrom EverandGynecology: Three Minimally Invasive Procedures You Need to Know About For: Permanent Birth Control, Heavy Menstrual Periods, Accidental Loss of Urine Plus: Modern Hormone Therapy for the Post Menopausal WomenNo ratings yet

- OB-GYN - Standardized Patient PrepDocument6 pagesOB-GYN - Standardized Patient Prepskeebs23No ratings yet

- Genital ProlapseDocument39 pagesGenital ProlapseFenias BoaneNo ratings yet

- Birth Control Methods BayoDocument3 pagesBirth Control Methods BayoRamsis Pimentel BayoNo ratings yet

- Varicocele and Male Infertility Evidence in The Era of Assisted Reproductive Technology 2161 038X 3 E114Document3 pagesVaricocele and Male Infertility Evidence in The Era of Assisted Reproductive Technology 2161 038X 3 E114quickdannyNo ratings yet

- IntersexDocument46 pagesIntersexGeeta DoppaNo ratings yet

- Science 10 LAS Quarter 3Document89 pagesScience 10 LAS Quarter 3Christopher John Natividad100% (3)

- Pelvic Examination: W - Newton LongDocument3 pagesPelvic Examination: W - Newton LongyuexinchongNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document16 pagesModule 1bhrayancacheroNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Preventing Pregnancy Common Ways of Preventing PregnancyDocument3 pagesChapter 7 - Preventing Pregnancy Common Ways of Preventing PregnancyJennie WatanabeNo ratings yet

- Good Samaritan CollegesDocument3 pagesGood Samaritan Collegesdimple2718No ratings yet

- Facilities Provide by Podar Hospital MumbaiDocument8 pagesFacilities Provide by Podar Hospital MumbaivaibhavNo ratings yet

- Male InfertilityDocument26 pagesMale InfertilitySahil VermaNo ratings yet

- Female Reproduction CyclesDocument36 pagesFemale Reproduction CyclesKeanne RelanoNo ratings yet

- PCODDocument178 pagesPCODAbhishek Vijayakumar100% (1)

- InfertilityDocument46 pagesInfertilityOmg ,No ratings yet

- Anatomy and Physiology CompleteDocument9 pagesAnatomy and Physiology CompleteJohn BretanaNo ratings yet

- AIUM Practice Guideline For The Performance of Pelvic Ultrasound ExaminationsDocument6 pagesAIUM Practice Guideline For The Performance of Pelvic Ultrasound ExaminationsreyorquidiaNo ratings yet

- Disoreder Sex of DevelopmentDocument37 pagesDisoreder Sex of DevelopmentBesth To Frynce HutabaratNo ratings yet

- Klinefelter SyndromeDocument3 pagesKlinefelter SyndromeKylalerrsssNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology - Repro (EDITED)Document25 pagesPharmacology - Repro (EDITED)AditiNo ratings yet

- Reproductive SystemDocument7 pagesReproductive Systemcollege code - 5No ratings yet

- The Organs of The Male Reproductive System Are Specialized For The Following FunctionsDocument3 pagesThe Organs of The Male Reproductive System Are Specialized For The Following FunctionsGabrielaNo ratings yet

- Mammalian Reproductive SystemDocument50 pagesMammalian Reproductive SystemLeena MuniandyNo ratings yet

- Ovarian Cysts Treatment & Management - Approach Considerations, Fetal and Neonatal Cysts, Ovarian Cysts in PregnancyDocument6 pagesOvarian Cysts Treatment & Management - Approach Considerations, Fetal and Neonatal Cysts, Ovarian Cysts in PregnancyTrần Hà TrangNo ratings yet

- Case 2: Gumalo, Glethel Heruela, Michelle Jalandoni, IreenaDocument44 pagesCase 2: Gumalo, Glethel Heruela, Michelle Jalandoni, IreenaMichelle ThereseNo ratings yet

- Amenorrhea & Heavy Menstrual BleedingDocument22 pagesAmenorrhea & Heavy Menstrual BleedingJanesel Plariza PanerioNo ratings yet