Professional Documents

Culture Documents

5 Research Methods in The Information Systems Discipline A Literat

5 Research Methods in The Information Systems Discipline A Literat

Uploaded by

Hub TechnologyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

5 Research Methods in The Information Systems Discipline A Literat

5 Research Methods in The Information Systems Discipline A Literat

Uploaded by

Hub TechnologyCopyright:

Available Formats

Research Methods in IS Conferences

Research Methods in the Information

Systems Discipline: A Literature Analysis of

Conference Papers

Completed Research

Anna Kupfer

Otto-Friedrich University Bamberg

anna.kupfer@uni-bamberg.de

Abstract

I examine the employed research methods of 1,023 article from Information Systems (IS) conferences in

order to assess the status quo of the usage of research methods in the IS discipline. Thus, I follow a long

tradition of IS researchers who study literature in order to investigate and discuss topics such as diversity,

innovativeness, boundaries, and maturity in relation to the discipline’s evolution. To that end, in

alignment with previous scholars, I identify a categorization framework and classify all articles manually.

My results provide information about the absolute and relative number of employed research methods in

three selected years show a clear change of used research methods. I discuss the results in the light of new

challenges for the discipline (e.g. BigData, Design Science, private IS usage).

Keywords

Research method, research designs, research strategies, research approaches, meta-research.

Introduction

The Information Systems (IS) discipline has undergone a constant evolution since its beginnings in the

1970s. While innovations, societal evolutions, and smaller fashion waves impact IS research (Baskerville

and Myers 2009) in general, the changes have recently been accelerated by the enormous influence the

Internet has developed on the way of doing business (e.g. Cloud Computing, E-Commerce, E-Business)

and the way individuals interact also outside of firms (e.g. social networks, blogs, user generated content).

Further drivers include the miniaturization of IT that now makes the adoption of information systems

feasible in many areas of life (e.g. self-tracking, eHealth) and the falling cost of hardware that contributed

to the emergence of the ubiquitous computing paradigm (Yoo 2010). This evolution of the IS discipline is

in fact closely linked to the adoption of computers in evermore use cases outside the boundaries of

companies, now spanning many applications in public institutions and private households (Ferstl and

Sinz 2013; Lee 2016). The broader spectrum of applications and consequently the increasing body of

relevant theories is nicely reflected by the discipline’s name being altered from Management Information

Systems to Information Systems, which highlights the importance ascribed to the transition.

The relevance of such developments for IS research also becomes evident along the multitude of newly

emerging tracks on major IS conferences (International/European/Americas Conference on Information

Systems I/E/AMCIS) in comparison to the number of traditional tracks (see Ayanso et al. (2007)). For

example, the main topic of ICIS 2018 “Bridging the Internet of People, Data, and Things” lays focus on the

digitization of our everyday life and routines and the increase in data generation. Furthermore, ECIS2018

promotes tracks such as “Big Data Analytics and Business Transformation”. Moreover, also AMCIS2018

includes discussions on new trends and developments with the following tracks: “ICTs in Global

Development” or “Data Science and Analytics for Decision Support”. The seizure of the trends by the

discipline’s scholars also becomes apparent in Journals. Examinations of the evolution of journals (Gable

2010) indicate a careful but recent shift from an almost exclusive focus on business-related topics to a

wider perspective that also includes contributions covering topics outside the operational business

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 1

Research Methods in IS Conferences

context. These new topics and trends induce changes in the employment of research methods (Riedl and

Rueckel 2011) in the way that data analytics are needed in order to analyze the large amounts of user-

generated and secondary data due to private IS usage (twitter, Facebook etc.) or more field work is done

to understand how individuals interact with technology in the new non-organizational environment..

Since the beginning of the era of IS, scholars have started to examine the literature of the discipline in

order to capture its identity. Literature analysis serve to discuss topics like diversity, agility, legitimacy,

boundaries, and maturity of the discipline. They investigated various variables concerning IS literature:

core topics (Sidorova et al. 2008), co-citations (Culnan 1987), research methods (Chen and Hirschheim

2004), nationalities of authors (Gallivan and Ahuja 2015), underlying epistemology (Orlikowski and

Baroudi 1991). Results from such bibliometric or scientometric analysis lead to vivid discussions that help

to form an identity of IS research and question the focus of the discipline. Especially, research methods

are often investigated for such discussions. In general, research methods reveal a “philosophical

assumption” or “world view […] of the researcher” (Orlikowski and Baroudi 1991, p. 2) and they may also

account for new types of information such as Big Data (Chen et al. 2012) or new IS approaches (e.g.

Design Science). Pluralistic research methods may help to avoid “misunderstandings or incorrect

conclusions” (Ayanso et al. 2007, p. 674), supports “greater confidence in findings” (Palvia et al. 2004, p.

290), and offer “rich insights into various phenomena of interest that cannot be fully understood”

(Venkatesh et al. 2013, p. 21).

However, in the light of the new trends of the past years, existing studies of IS literature show various

shortcomings. First, studying the meta-analysis from Riedl and Rueckel (2011) and engaging in some

explorative literature research, it becomes apparent that most of such work is already outdated. The

detection of any of the above named trends is rather limited to the years of 2006 and 2007 (Ayanso et al.

2007; Venkatesh et al. 2013). Yet, IS trends such as BigData or the relevance of Design Science and

NeuroIS just arose since then (Iivari 2007; Riedl and Rueckel 2011), so, they cannot be reflected in the

results of previous studies. Second, due to the increased number of articles, studies focus solely on a small

number of outlets (Ayanso et al. 2007) and are thus prone to biases such as regional ones (Chen and

Hirschheim 2004; Riedl and Rueckel 2011). Additionally, more recent studies mainly investigate only one

aspect at a time and do not take a holistic view on the disciplines development (Venkatesh et al. 2013). In

order to overcome these shortcomings, I aim to answer the following research question:

What are currently employed research methods and does the composition of research methods reflect

new trends and phenomena of the past years in IS literature?

To that end, I undertake a bibliometric analysis of ECIS and ICIS articles in order to quantify the usage of

a set of research methods in various IS outlets and over a selected but broad period of time (full years of

1995, 2005, 2015). The results will help to obtain an updated view on the use of research methods.

Furthermore, in order to ensure that my data is representative and meaningful, I compare my results on a

historical basis and with some previous work.

Theoretical Background

Beyond various IT (Information Technology) and management related questions, the IS disciplines shows

a broad spectrum of self-reflection since its beginning. This self-reflection mainly encompasses examining

the intellectual structure of the discipline. Such an intellectual structure conceptualizes scholarly work in

the form of thematic analysis (Hirschheim et al. 1996) or approaches (Vessey et al. 2002). With the help

of such (often) critical self-reflections, IS scholars discuss for example issues such as diversity (Alavi et al.

1989; Cocosila et al. 2009; Culnan 1986), identity (Agarwal and Lucas 2005; Benbasat and Zmud 2003),

boundaries and methodological rigor (Chen and Hirschheim 2004; Grover et al. 1993), publication biases

(Gallivan and Ahuja 2015), cumulative research tradition (Farhoomand and Drury 1999; Hamilton and

Ives 1982a), and legitimacy (Lyytinen and King 2004). In particular, a large stream of research is engaged

into studying the employed research methods to debate on the identity of the discipline, to influence

identity formation (Riedl and Rueckel 2011), or to ensure diversity (French and Shim 2011). In this sense,

various discussion over the previous decades concerned positivist vs. interpretivist paradigms, rigor vs.

relevance, the core of IS, and very recently behavior vs. Design Science (French and Shim 2011). Riedl and

Rueckel (2011) analyzed twenty different studies that investigated the employed research methods from

1968 until 2006 and give a comprehensive overview on the most prominent evolutions of the last decades.

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 2

Research Methods in IS Conferences

First of all, it is vital to discern the role of the research method within the research process (Jenkins

1985): A research method helps the researcher to gather data. After the data collection itself, data analysis

starts. The results of data analysis answer to a specific research question. For that reason, the research

method represents the first part of a methodology chosen by a researcher to engage into scientific work.

The article alone from Riedl and Rueckel (2011) reveals 50 different research methods that have been

applied in IS research. Additionally, when studying various frequently cited and discussed articles in IS

research a broad collection of (meta) categories of research methods, research methods, and data

collection methods can be collected. However, each author uses another framework and or adapts

existing ones. So, it exists unanimity about the exact range of IS research methods and it remains difficult

to find simple definitions and differentiations for research methods, approaches, strategies and

paradigms. In the following, I try to summarize the utmost number of perspectives of IS scholars.

Especially Orlikowski and Baroudi (1991), Chen and Hirschheim (2004), and Galliers and Land (1987)

focus on the underlying epistemological aspects of the employed research methods to show that the

positivist paradigm (i.e. testing of hypothesis and drawing conclusions from a selected sample) clearly

dominates during the period of interest. Furthermore, Vessey et al. (2002) differentiate another level they

refer to as the research approach. They distinguish evaluative (e.g. evaluating an Enterprise Resource

System), descriptive, and formulative (e.g. formulate an algorithm) research approaches. Their study

revealed that evaluative approaches dominate in IS research. Moreover, most authors (Alavi et al. 1989;

Chen and Hirschheim 2004; Farhoomand and Drury 1999; Harrison and Wells 2001; Holz et al. 2006;

Venkatesh et al. 2013) classify the employed research method in empirical (based on observations,

describing an object) vs. non-empirical (based on ideas, frameworks) and qualitative (narrative data

collection) vs. quantitative research (numerical/statistical data collection). Yet, other mix these levels and

combine research methods with meta-designations or data collection (Backlund 2005).

In fact, Riedl and Rueckel (2011) analyze twenty research methods studies and identify four research

methods that are used the most in IS research: surveys, case studies, laboratory experiments, and field

experiments.. Yet, the remaining 45 research methods identified by Riedl and Rueckel (2011) are less

often or even rarely used (e.g. protocol analysis, game playing, hermeneutics, secondary data usage). In

addition, differently named research methods often describe very similar ways of data collection. For

example, this encompasses methods including data analytics or secondary data usage which all use

already “existing” (Chen and Hirschheim 2004, p. 206) “large, diverse, and dynamic data sets of user-

generated content” (Müller et al. 2016, p. 289). This represents a challenge for detecting essential changes

within the usage of research methods and the discussion of challenges and trends. The unanimity and

plethora of named research methods by scholars might hinder my goal of recognizing any reflection of

“new IS topics” (such as data analytics, design science, Neuro IS) and changes on the employment of IS

research methods. First of all, the data is not easily comparable (as each author has a different framework

with only small overlaps). Second, the existing names of research methods may not necessarily reflect a

change in the IS discipline (e.g. almost no framework contains design science as a research method). For

that reason, I chose to not only rely on one framework but to combine multiples to take differentiations

into account and ensure easy comparisons with other studies.

Furthermore, even though scholars studied the use of research methods since 1968 in order to answer

various questions on behalf of the status quo of the discipline, the most current data set only includes data

from 2007 (Venkatesh et al. 2013). Yet, in the last years, the discipline acknowledges more and more “new

questions and opportunities created by the availability of Big Data” (Agarwal and Dhar 2015, p. 444) and

other research methods such as design science (Hevner et al. 2004, Iivari 2007) or NeuroIS find their way

into IS research. Thus, in order to quantify the influence of such evolutions on the discipline, I aim to

gather data from immediate and distant past.

Methodology

I conduct a bibliometric analysis to quantify the use of research methods in IS literature by categorizing

and counting the employed research methods (Chen et al. 2012; Sørensen and Landau 2015). For the

categorization I undertake a content analysis (Weber 1990) of IS articles in order to measure science-

specific “publication patterns” (Arnott and Pervan 2012, p. 926).

For the categorization I developed a framework for classifying research methods, strategies, and

approaches. The frame work was developed based on literature. A first (explorative) round of

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 3

Research Methods in IS Conferences

categorization considered the Chen and Hirschheim (2004). Through this rather inductive approach, I

realized that the employed categories do not properly represent the categories needed for a more

thorough analysis that can be compared to other studies or interpreted in regard to my research

questions. For that reason, I reworked the categorization framework by taking into consideration the

categorization from Alavi et al. (1989), Hamilton and Ives (1982b), Harrison and Wells (2001), and

Venkatesh et al. (2013). All four articles were used because they either are quite similar or cover a broad

spectrum of research methods. Additionally, they are from different time periods which should cover a

broad variety of research methods. I essentially differentiate empirical and non-empirical research

designs (see Table 1), definitions can be found section “theoretical background”). Non-empirical research

mainly consists of a qualitative approach containing research methods such as conceptual, opinion, other,

or literature analysis (with an only quantitative analysis goal). Empirical research designs (field study,

literature review, action research, etc.) follow a quantitative and/or qualitative approach. Finally, my

framework also accounts for mixed strategies and approaches (both) and combinations of different

multiple research methods. The research methods are explicitly defined in the articles named above.

Research design (1 or both of the following) Empirical Non-empirical

Research approach (1 or both of the following) Quantitative Qualitative Quantitative Qualitative

Research method Action Research Simulation Prototype

(1-n of the following) Ethnography Tutorial

Case Study Opinion

Survey Conceptual

Field & Lab Experiment Literature Review

Field Study Others

Literature analysis

Others

Table 1 Overview the Combined Categorization Framework

In the first exploratory categorization round there was significant increase in articles using a design

science methodologies as well as data analytics studies. Rather than inventing a new category myself, I

chose to reuse existing categories in use a combination of the non-empirical research method prototype

(as used by Alavi et al. (1989), Van Horn (1973), and Jenkins (Jenkins 1985) in the case of an application

or software development) combined with field study or action research, for example. This decision

originates from the discussions within the community about similarities between design science and other

research methods or epistemologies (Burstein and Gregor 1999; Iivari and Venable 2009; Järvinen 2007).

Additionally, concerning the research methods including data analytics/secondary data/grounded

theory/big data/archival data (Alavi et al. 1989; Hamilton and Ives 1982b; Holz et al. 2006; Jenkins

1985; Müller et al. 2016; Vessey et al. 2002), I tried to bring together these categories that are basically

quite similar but have a different notation in various studies. Following Riedl and Rueckel (2011) and my

experiences, I approach the issue by reconsidering a traditional and established research method before

inventing a new artificial one. Considering the definitions of these similar categories, they all describe the

(re)gathering of already (often automatically) collected data from a real world setting (blog, twitter, stock

prices, consumption readings). As the data has been gathered in an explorative way without a primary

experimental design, I recognize several aspects that describe a field study (Alavi et al. 1989; Cheon et al.

1993). In order to more precise on the non-empirical research methods, I used a variety of categories.

Notable, the category conceptual was enlarged. According to Alavi et al. (1989) and Chen and Hirschheim

(2004) this category contains articles that develop frameworks, models, and work with theories. From my

insights from coding of ECIS and ICIS articles in the first round, the category should also encompass

conceptual work in the context of algorithm development or mathematical modeling.

In order to gather a representative and reasonably sized sample, I chose to include all publications that

appear in the conference proceedings of ICIS and ECIS for the years 1995, 2005, 2015 (see Table 2). As I

started my analysis mid 2016, I wanted to include the full number of publications of a whole year and the

previous year (2015) offered a complete year of publications. Having already over 600 articles at hand, I

chose to select two further years to cover a broad period and to ensure historically comparisons as well as

previous studies. I selected two top IS conferences because (1) the data base is large, (2) the data is more

recent (due to the missing delay for the review process that exists for journal articles, see Sørensen and

Landau (2015)), (3) in many cases the articles represent a first version of highly qualitative journal articles

anyway, and (4) most previous studies rely on journal publications only such that I can contribute by

enlarging the perspective.

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 4

Research Methods in IS Conferences

In an Excel file various data was stored an analyzed descriptively. For each article the following

information is available: the year of publication, the publication outlet (ECIS or ICIS), the authors, the

title, the abstract, the research design, the research approach, one until five possible employed research

methods, additional information (such as if an article named another research method which did not fit to

my categorization or further precisions such as lab or field for experimental research methods). In 674

articles the explicitly named research methods were extracted and correspond to my categories named

above. 145 articles did not mention a precise research method, for that reason, the coder categorized the

articles according to my framework. For 71 articles at least one research method had to be renamed

(because the named research method did not fit in my categorization scheme). Finally, 133 articles

employed several research methods either explicitly named and according to my categories or no explicit

research method and had to be categorized according to my framework. The categorization process

encompasses analyzing the full text of an article, as abstract and title (both collected in a data base) do not

often contain the focal information. So, the coder scans the methodology section and the general structure

of a paper.

Proceedings / Number of all Publications in

Journals 1995 2005 2015

ECIS 104 160 286

ICIS 44 85 344

Total for all: 148 245 630

Table 2 Overview on the Number of Articles Analyzed

All in all, in order to ensure validity and reliability of the classification, I developed a detailed guideline for

coders and used a training sample of over 40 articles.

Results

In order to answer research question one about the current employment of research methods, I counted

the articles and the employed research methods per article for 2015. Then, I summarized the frequencies

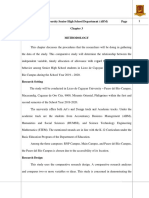

in bar charts (Figure 1 and 2). As the bar chart 2.1 and 2.2 of Figure 1 show, the majority of the articles of

omy sample (both outlets together) are still of an empirical (44%) as well as qualitative (45%) nature. The

predominantly used research methods (chart 2.3 of Figure 2) in both outlets together are: conceptual,

case study, field study, survey, and literature review. They account together for over 90% of all employed

research methods. The remaining research methods (experiment, prototype, ethnography, simulation,

literature analysis, other, action research, and opinion) are far less often employed. Please consider that

due to the fact that an article may use up to five research methods, the number of employed research

methods (n=996) exceeds the number of articles of 2015 (n=630) in my data set. When comparing the

compositions of 2015 for the different outlets (ECIS and ICIS), the results show (2.1 and 2.2 in Figure 2),

that in the ICIS proceedings of 2015 the employed research methods are dominated by conceptual

research methods (70%) whereas ECIS articles preferable employ conceptual as well as case study and

field study methods. Moreover, ECIS shows to have accepted a greater part of articles that use empirical

as well as non-empirical research designs (21 and 5 percentage points difference). ICIS publishes

relatively more empirical and mixed (both empirical and non-empirical) designs. Considering the

research approaches, articles of both conferences employ the same relative part (21%) of quantitative

approaches. Yet, ECIS is dominated by qualitative approaches (53%), while ICIS articles almost equally

use qualitative as well as mixed approaches.

Relating to research question two, I also analyzed the frequencies for the three main variables (research

design, approach and methods) for all three selected years (1995, 2005, 2015) to get an impression on

trends and variations. Considering the overall frequencies for all outlets and years, empirical designs

(over 40% articles), qualitative approaches (over 50% articles), and conceptual research methods (over

85% employed research methods) dominate the sample. The bar charts 2.4 and 2.5 of Figure 1 show the

different shares of employed research designs and approaches in each year (1995, 2005, 2015) as well as

for each conference separately and consolidated. The charts show that mixed research designs increased

from 1995 to 2015. The non-empirical research designs decreased during this period (from 66% in 1995 to

36% in 2015) and empirical ones slightly increased. The shares are different for the research approaches:

mixed and pure quantitative approaches slightly increase and qualitative approaches rather decrease.

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 5

Research Methods in IS Conferences

In a next step, I zoom into more details and analyze to what extent the research methods are being used in

the conferences for all three years (see Figure 2). To that end, I show the relative part of employed

research methods for the complete sample which contains 1,023 articles with 1,531 identified research

methods. I report the shares of frequencies for both conferences/outlets together as well as individually.

First, I can observe that during all years conceptual research methods dominate. Yet, there is a small

increase from 1995 to 2015 (10 percentage points). The effect seems to be mainly induced by the ICIS

research methods as the share has been almost doubled. However for ECIS there is rather a downward

trend – a small one of 10 percentage points. Then, the share for the second most often used research

method, case study, is relatively stable over the years for both conferences together (1995: 15%, 2005:

16%, 2015: 12%). The small decrease is mainly due to the ICIS articles, where the share of case studies was

more than cut in half (from 16% to 6%). For ECIS, there is rather an upward trend. The third most often

used research method is survey (questionnaires and interviews). The share of this research method

decreases mainly for ICIS (from 20% in 1995 to 5% in 2015) and stays stable for ECIS articles. All in all,

the trend for both conferences is rather decreasing.

2.1 Relative part of research design 2.3 Relative part of employed research

employed in ICIS and ECIS articles for methods (n=996) in ECIS and ICIS articles 2.4 Relative part of research design employed in ICIS and

2015 (n=630) for 2015 ECIS articles for all three years (n=1023)

100,0%

100% 100%

Non Non Non

90% 19% 14% 17%

90% Empirical; Empirical;

Empirical; 33% 29%

19% 14% 17% Conceptual 80% 39% 36% 39% 33%

80% 90,0%

70%

12% 36%

70% Empirical; 60% 44%

35% Empirical; 56% Non-Empirical

60% 50% 36%

Empirical; 44% 80,0% Case Study 36% 52%

41% 40% 41% Empirical

50% 55% 55%

30% 59% Both

40% 49%

20% 39%

70,0% 58% 31%

10% 25% 25% 20%

30% Field Study 16%

Both; 51% 9%

70% 0%

20% Both; 39% 1995 2005 2015 1995 2005 2015 1995 2005 2015

Both; 26%

10% 60,0% ECIS ECIS

ECIS ECIS ICIS ICIS

ICIS ICIS Both Both

Outlets

Both Outlets

Outlets

Both Outlets

0% Survey

ECIS ICIS Both Outlets

2.5 Relative part of research approach employed in ICIS

50,0% 20% and ECIS articles for all three years (n=1023)

2.2 Relative part of research approaches

employed in ICIS and ECIS articles for Literature Review 100%

9% 6%

16% 14%

2015 (n=630) 90% 18% 21% 21% 21%

40,0% 32%

100% 80%

12% 41%

Quantitativ Quantitativ Quantitativ 70%

90% 10% Experiment

e; 21% e; 21% e; 21% 60% 67% 38%

30,0% 60% 45%

80% 50% 53% 64% Quantitative

6% 69%

70% 10% 40% 57% Qualitative

Qualitative 11% 30% Both

60% Qualitative Prototype 53%

Qualitative ; 38% 20,0% 10% 20% 41%

; 45% 34%

50% ; 53% 8% 24% 26% 27%

10% 20%

6% 13% 11%

40% 0%

5%

10,0% 4% 5% 1995 2005 2015 1995 2005 2015 1995 2005 2015

30% Ethnography, Simulation,

3% 5% 2% Literature Analysis, Others, ECIS ECIS ECIS ICIS ICIS ICIS Both Outlets

Both Outlets

Both Outlets

20% Both; 41% ECIS ICIS Both Outlets

Both; 34% 2% 1% Action Research, Opinion

Both; 26% 5,5% 0,3%

10% 2,8% 3,9%

0,0%

0% ECIS ICIS Both

ECIS ICIS Both Outlets Outlets

Figure 1 Results Showing the Relative Part of Employed Research Designs, Approaches as

well as Methods for the Conferences for 2015 and of the Employed Research Designs and

Approaches for all three Years

Further, field studies are the fourth most often used methods. I observe that there has been a really small

share in 2005 - especially induced by ICIS research methods: In 1995, 12% of all research methods

constitute field studies, in 2005 there is only 1%, and in 2015 the share rises again up to 10%. For ECIS,

the share of research methods clearly increases (doubled from 1995: 5% to 2015: 10%). These four

research methods already cover 80-90% of all employed research methods in my sample. The remaining

10-20% constitute: literature review, opinion, experiment, action research, literature analysis, tutorial,

others, simulation, ethnography, and prototype. For both conferences together only the share of the

literature review increases (from 1% to 5%), but all other research methods show rather a decrease

(simulation, action research, experiment, opinion, and tutorial is even nonexistent in 2005 and 2015) or

stability (ethnography and prototype). Comparing the individual compositions of both conferences, I

observe that for ECIS there even is no tutorial method at all and for ICIS tutorials were only employed in

1995. Literature analysis (only quantitative data collection methods) only appear in 2015 for both

conferences. In the ICIS sample the research methods others, simulation, literature review, and

ethnography only appear (but with a really small share) in 2015. The same almost applies for action

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 6

Research Methods in IS Conferences

research which only appears in 2005 and 2015 in ICIS conferences. Moreover, prototypes and

experiments were only employed in 1995 and 2015 in ICIS. Interestingly, opinion methods have a rather

large share only in 2005 (9% in comparison to 2% in 1995 and 1% in 2015) in all ICIS articles. For ECIS

simulation and ethnography methods do not appear in 2005 (yet decreased in comparison to the share in

1995), and the remaining research methods (others, action research, and opinion) show a downward

trend. Only literature analysis, experiments, and prototypes show a slight increase of a hand of percentage

points.

Figure 2 The Relative Part of Research Methods Employed (n=1,531) in Articles (n=1,023)

for 1995, 2005, 2015 and all Outlets (Separate and Together)

Discussion and Conclusion

In order to investigate the current composition of research methods employed in IS conferences as well as

demonstrating if there are any changes within time that may reflect trends and changes in IS research, I

undertook a bibliometric analysis of 1,023 articles from ECIS and ICIS. I derived a categorization scheme

from literature that covers a broad variety of research methods as well as vital meta-categories (research

designs and approaches). Concerning the current composition (for 2015) empirical designs, qualitative

approaches, and the following research methods dominate: conceptual (58%), case study (12%), field

study (10%), survey (8%), and literature review (5%). There are clear differences between ECIS and ICIS

conferences in the use of research methods, designs and approaches. ICIS is much more dominated by

conceptual methods (which have almost doubled since 1995). Whereas ECIS articles employ – to the same

extent - conceptual methods as well as case and field studies. In 292 articles of 2015, a conceptual method

is used as the first research method and in 85% this first research method is combined with at least one

additional research method. This is not surprising, as many articles build upon a self-developed

(research) framework or development in order to validate it empirically (which is mostly described in the

methodology section). On the one hand, this explains the rather high share of conceptual papers as well as

the high share of mixed research designs (83%). All together, these results show that in 2015 authors lay

attention to both theorizing as well as empirical validation. This shows that some calls of scholars

(Venkatesh et al. 2013) have been answered to obtain rich insights of various phenomena. Yet, concerning

the approaches, mixed as well as purely qualitative ones dominate. This shows a contradicting trend to the

findings from Backlund (2005) for ECIS. He finds that qualitative research methods are increasing

between 2002 and 2004 as well as that quantitative methods are relatively stable during this time.

Overall, for all three years, the data show that conceptual methods have increased (especially for ICIS).

Another upward tendency can be seen for field studies and literature reviews. Yet, methods such as case

study, survey, experiment, and opinion have decreased. It becomes apparent that the tendencies between

ECIS and ICIS are often contradictory. This can be explained there are regional differences (different

preferences for research methods or topics) or differing conference or reviewer strategies and preferences.

Then, in almost 50% of the articles of all three years, the conceptual method is used as first method – 70%

of these articles use at least another research methods in combination. Again, this explains the rather high

share of conceptual papers as well as the mixed research designs. Interestingly, when zooming into

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 7

Research Methods in IS Conferences

additional information of the research methods, I observe that only in 2015 the methods design science

appeared. As the method does not represent a specific category in the categorization scheme, I renamed

the employed research method and checked if only a framework or a prototype was developed and by

what kind of research method it was validated (e.g. action research). Almost 45% of all renamed research

methods are design science studies. The surge of design science papers may explain why prototype

methods experience a sudden (re)-appearance in 2015 in ICIS papers. Furthermore, I can see that there is

a significant increase in the availability of automatically observed data (also often called secondary data)

that is analyzed in the form of field studies. I assume that this new kind of data is more often

automatically analyzed with data analytic methods which decreases the risk of subjectivity when

interpreting collected qualitative data. This data encompasses secondary (such as electricity consumption

or geographical tracking) and user-generated data (such as from Twitter, Facebook, Blogs). Additionally,

the share of field studies slightly increased from 1995 to 2015, especially for ECIS. Moreover, in

accordance with Backlund (2005), I also observe an increase of interviews (as I differentiate interview

surveys and questionnaire surveys with the additional information). Finally, considering the research

designs, I can see that especially for ECIS the share of non-empirical research decreases and empirical

designs increase. On the contrary, for ICIS mixed designs significantly increase at the expense of pure

empirical and non-empirical designs. The reported results show that there has been an evolution of the

usage of research methods in the light of new trends (Open Data, Big Data (Laine and Lee 2015)) and

“research orientations” (Iivari and Venable 2009). This is translated by the newly analyzed data, for

example. Yet, the tendency is positive and it will be interesting to re-examine the situation in a couple of

years, as the comparison with selective years of the previous 20 years already showed an interesting

evolution of different research methods.

The results contribute in various ways to literature. First, I provide an update on employed research

methods in IS of previous but outdated studies (Backlund 2005; Chen and Hirschheim 2004; Ebeling et

al. 2012; Farhoomand and Drury 1999; Glass et al. 2004; Palvia et al. 2004). Second, the data set is only

based on conference proceedings which are often ignored in larger journal publications (see theoretical

background). This enlarges the perspective and adds interesting insights on research methods employed

in journal articles. Third, as most studies use a large variety of categorization schemes, I attempt to have

developed a more unified framework that takes into consideration various distinctions (research designs,

approaches, methods) that are often used in a very heterogenous way by other scholars. This should help

to compare my results easily to other study results and ensures a wide spectrum of employed research

methods. To start, in comparison to Backlund (2015) and Ebeling et al. (2012) my others category is really

small (about 1% in comparison to 10-41%). This shows that the framework takes into consideration a large

number of employed research methods. In comparison to Chen and Hirscheim (2004), surveys are less

widely used and the IS research is still dominated by empirical research. So, the interpretivist domain is

still rather sparse. Fourth, the insights on the composition of employed research methods may guide

researchers to employ more heterogenous research methods, designs, and approaches in order to preserve

or increase diversity. They may even get encouraged to revive older research methods from 1995 and 2005

in order to acquire interesting and rich results than traditional research methods (field and case studies as

well as surveys). Finally, the results obtained by my study contribute to the general discussions on the IS

discipline. As such, the employment of research methods, as part of the intellectual structure of the IS

discipline, reveals increasing diversity, openness, maturity, and innovativeness. In alignment with

previous researchers, I want to “motivate a more reasoned, reflective adoption of approaches from the

diverse perspectives available” (Orlikowski and Baroudi 1991, p. 1). These insights should not only direct

authors but also reviewers or track chairs who can manage the plurality and heterogeneity of conferences

at the first place. With the appearance of new methods and data, scholars can revisit the discussion of

Benbasat and Zmud (2003), Lyytinen and King (2004) or Argawal and Lucas (2005) about the relevance

of the IT artefact in IS research.

To begin with the limitations, the implications of the research at hand rely mostly on the subjectivity of

only one round of classification by a coder. For that reason, the coder carefully read the papers and re-

used (if possible) the research method as indicated by the authors. Another limitation relies on the

selected focus of the conferences – I cannot rule out that the results in other IS outlets are different.

Additionally, concerning the representativeness for the years in between, the three years selected for the

analysis (1995, 2005, and 2015) is questionable - special issues or specific conference themes may affect

the analysis. Future work will enlarge and refine as well as strengthen my results First of all, I will

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 8

Research Methods in IS Conferences

integrate 737 journal articles from the Senior Scholar’s Basket of Eight to the data sample. Second, I will

draw up a detailed comparison of my research results to previous articles. Third, I will consider additional

data such as the keywords of each article in order to allocate an IS topic to each article and compare the

evolution of IS topics and research methods over time.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, R., and Dhar, V. 2015. “Big Data , Data Science , and Analytics : The Opportunity and Challenge

for IS Research,” Information Systems Research (25:3), pp. 443–448.

Agarwal, R., and Lucas, H. C. 2005. “The Information Systems Identity Crisis: Focusing on High-Visibility

and High-Impact Research,” MIS Quarterly (29:3), pp. 381–398. (https://doi.org/Article).

Alavi, M., Carlson, P., and Brooke, G. 1989. “The Ecology of MIS Research: A Twenty Year Status Review,”

in Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, J. DeGross, J. C.

Henderson, and B. R. Konsynski (eds.), Boston, MA, USA, pp. 363–375.

Arnott, D., and Pervan, G. 2012. “Design Science in Decision Support Systems,” Journal of the

Association for Information (13:11), pp. 923–949.

Ayanso, A., Lertwachara, K., and Vachon, F. 2007. “Diversity or Identity Crisis? An Examination of

Leading IS Journals,” Communications of AIS (20:42), pp. 660–680.

Backlund, P. 2005. “On the Research Approaches Employed at Recent European Conferences on

Information Systems (ECIS 2002–ECIS 2004),” in Proceedings of the ECIS, pp. 1–13.

Baskerville, R., and Myers, M. D. 2009. “Fashion Waves in Information Systems Research and Practice,”

MIS Quarterly (33:4), pp. 647–662.

Benbasat, I., and Zmud, R. W. 2003. “The Identity Crisis Within The IS Discipline : Defining And

Communicating The Discipline ’ s Core Properties,” MIS Quarterly (27:2), pp. 183–194.

Burstein, F., and Gregor, S. 1999. “The Systems Development or Engineering Approach to Research in

Information Systems: An Action Research Perspective,” in 10th Australasian Conference on

Information Systems, Beverly Hope and P. Yoong (eds.), Wellington, New Zealand, pp. 122–134.

Chen, H., Chiang, R. H. L., and Storey, V. C. 2012. “Business Intelligence and Analytics: From Big Data to

Big Impact,” MIS Quarterly (36:4), pp. 1165–1188.

Chen, W., and Hirschheim, R. 2004. “A Paradigmatic and Methodological Examination of Information

Systems Research From 1991 to 2001,” Information Systems Journal (14:3), pp. 197–235.

Cheon, M. J., Groven, V., and Sabherwal, R. 1993. “The Evolution of Empirical Research in IS,”

Information & Management (24:3), pp. 107–119.

Cocosila, M., Serenko, A., and Turel, O. 2009. “A Scientometric Study of Information Systems

Conferences : Exploring ICIS , PACIS and ASAC,” in Proceedings of the AMCIS, San Francisco, CA,

USA, pp. 1–10.

Culnan, M. J. 1986. “The Intellectual Development of Management Information Systems, 1972-1982 : A

Co-Citation Analysis,” Management Science (32:2), pp. 156–172.

Culnan, M. J. 1987. “Mapping the of MIS, 1980-1985 : A Co-Citation Analysis,” MIS Quarterly (11:3), pp.

341–353.

Ebeling, B., Hoyer, S., and BÃ, J. 2012. “What Are Your Favorite Methods? - An Examination on the

Frequency of Research Methdos for IS Conferences from 2006-2010,” in Proceedings of ECIS, p. 13.

Farhoomand, A. F., and Drury, D. H. 1999. “A Historiographical Examination of Information Systems,”

Communications of AIS (1:19), pp. 1–27.

Ferstl, O. K., and Sinz, E. J. 2013. Grundlagen Der Wirtschaftsinformatik, (7th ed.), München:

Oldenourg Wissenschaftsverlag.

French, A. M., and Shim, J. P. 2011. “Multinational Diversity in IS Research: The Effects of Education on

Publication Outlets,” Journal of Information Technology (26:4), pp. 313–322.

Gable, G. 2010. “Journal of Strategic Information Systems Strategic Information Systems Research : An

Archival Analysis,” Journal of Strategic Information Systems (19:1), pp. 3–16.

Galliers, R. D., and Land, F. F. 1987. “Viewpoint: Choosing Appropriate Information Systems Research

Methodologies,” Communications of the ACM (30:11), pp. 901–902.

Gallivan, M., and Ahuja, M. 2015. “Co-Authorship, Homophily, and Scholarly Influence in Information

Systems Research,” Journal of the Association of Information Systems (16:12), pp. 980–1015.

Glass, R., Ramesh, V., and Vessey, I. 2004. “An Analysis of Research in Computing Disciplines,”

Communications of the ACM - Wireless Sensor Networks (47:6), pp. 89–94.Grover, V., Lee, C. C.,

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 9

Research Methods in IS Conferences

and Durand, D. 1993. “Analyzing Methodological Rigor of MIS Survey Research from 1980-1989,”

Information & Management (24:6), pp. 305–317.

Hamilton, S., and Ives, B. 1982a. “MIS Research Strategies,” Information & Management (5), pp. 339–

347.

Hamilton, S., and Ives, B. 1982b. “MIS Research Strategies,” Information & Management (5), pp. 339–

347.

Harrison, R., and Wells, M. 2001. “A Meta-Analysis of Multidisciplinary Research,” Empirical Software

Engineering (5:3), pp. 1–15.

Hevner, A., March, S., Park, J., and Ram, S. 2004. “Design Science Research in Information Systems,”

MIS Quarterly (28:1), pp. 75–105.

Hirschheim, R., Klein, H. K., and Lyytinen, K. 1996. “Exploring the Intellectual Structures of Information

Systems Development: A Social Action Theoretic Analysis,” Accounting, Management and

Information Technology (6:1), pp. 1–64.

Holz, H. J., Applin, A., Joyce, D., Purchase, H., Reed, C., and Haberman, B. 2006. “Research Methods in

Computing : What Are They , and How Should We Teach Them ?,” ACM SIGCSE Bulletin (38:4), pp.

96–114.

Van Horn, R. L. 1973. “Empirical Studies of Management Information Systems,” ACM SIGMIS Database,

pp. 172–182.

Iivari, J. 2007. “A Paradigmatic Analysis of Information Systems As a Design Science,” Scandinavian

Journal of Information Systems (19:2), pp. 39–64.

Iivari, J., and Venable, J. 2009. “Action Research and Design Science Research - Seemingly Similar but

Decisively Dissimilar,” in Proceedings of the 17th ECIS, Verona, Italy, pp. 1642–1653.

Järvinen, P. 2007. “Action Research Is Similar to Design Science,” Quality and Quantity (41:1), pp. 37–

54.

Jenkins, A. M. 1985. “Research Methodologies and MIS Research,” in Research Methods in Information

Systems, E. Mumford, R. Hirschheim, G. Fitzgerald, and T. Wood-Harper (eds.), Amsterdam: Elsevier

Science Publishers B.V. (North-Holland), pp. 103–117.

Laine, S., and Lee, C. 2015. “Transparent Data Supply for Open Information Production Processes,” in

Proceedings of the 23rd ECIS, Muenster, Germany, pp. 1–15.

Lee, J. K. 2016. “Invited Commentary: Reflections on ICT-Enabled Bright Society Research,” Information

Systems Research (27:1), pp. 1–5.

Lyytinen, K., and King, J. L. 2004. “Nothing At The Center?: Academic Legitimacy in the Information

Systems Field,” Journal of the AIS (5:6), pp. 220–246.

Müller, O., Junglas, I., Brocke, J. Vom, and Debortoli, S. 2016. “Utilizing Big Data Analytics for

Information Systems Research: Challenges, Promises and Guidelines,” European Journal of

Information Systems (25:4), pp. 289–302.

Orlikowski, W. J., and Baroudi, J. J. 1991. “Studying Information Technology in Organization : Research

Approaches and Assumptions,” Information Systems Journal (2:1), pp. 1–28.

Palvia, P., Leary, D., Mao, E., Midha, V., Pinjani, P., and Salam, A. F. 2004. “Research Methodologies in

MIS: An Update,” Communications of the AIS (14:1), pp. 526–542.

Riedl, R., and Rueckel, D. 2011. “Historical Development of Research Methods in the Information

Systems Discipline,” in Proceedings of the 17th AMCIS, Detroit, MI, USA, pp. 1–15.

Sidorova, A., Evangelopoulos, N., Valacich, J. S., and Ramakrishnan, T. 2008. “Uncovering the

Intellectual Core of the Information Systems Discipline,” MIS Quarterly (32:3), pp. 467–482.

Sørensen, C., and Landau, J. S. 2015. “Academic Agility in Digital Innovation Research : The Case of

Mobile ICT Publications within Information Systems 2000 – 2014,” Journal of Strategic Information

Systems (24:3), pp. 158–170.

Venkatesh, V., Brown, S. A., and Bala, H. 2013. “Bridging the Qualitative-Quantitative Divide: Guidelines

for Conducting Mixed Methods Research in Information Systems,” MIS Quarterly (37:3), pp. 855–

879.

Vessey, I., Ramesh, V., and Glass, R. L. 2002. “Research in Information Systems: An Empirical Study of

Diversity in the Discipline and Its Journals,” Journal of Management Information Systems (19:2),

pp. 129–174.

Weber, R. P. 1990. Basic Content Analysis, (2nd ed.), Newbury Park: SAGE.

Yoo, Y. 2010. “Computing in Everyday Life: A Call for Research on Experiential Computing,” MIS

Quarterly (34:2), pp. 213–231.

Twenty-fourth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New Orleans, 2018 10

You might also like

- Conceptual Foundation of Human Factor MeasurmentDocument257 pagesConceptual Foundation of Human Factor MeasurmentSanty SanNo ratings yet

- Ethiopian Instiue of Technology: Department of Information SystemDocument47 pagesEthiopian Instiue of Technology: Department of Information SystemAnonymous ccQg5k1No ratings yet

- 2023 JIT CFP SI Next Generation Research MethodsDocument4 pages2023 JIT CFP SI Next Generation Research MethodsTyric Commercial Air Conditioner Inc.No ratings yet

- Library & Information Science Research: Aurora González-Teruel, M. Francisca Abad-GarcíaDocument6 pagesLibrary & Information Science Research: Aurora González-Teruel, M. Francisca Abad-GarcíaGrecia V. MuñozNo ratings yet

- Information Systems Dominant Paradigms and Emerging Concepts - ADocument13 pagesInformation Systems Dominant Paradigms and Emerging Concepts - ALife TimeNo ratings yet

- Myers Qualitative ResearchDocument19 pagesMyers Qualitative ResearchMuhammad Asroruddin100% (2)

- Introduction To Information Systems - Methodologies 2: Silvia Masiero University of Oslo, Department of InformaticsDocument25 pagesIntroduction To Information Systems - Methodologies 2: Silvia Masiero University of Oslo, Department of InformaticsElizabeth DovginkaNo ratings yet

- QUT Digital RepositoryDocument23 pagesQUT Digital RepositoryThales S.No ratings yet

- Design Science in IS Research: A Literature AnalysisDocument19 pagesDesign Science in IS Research: A Literature AnalysisendaleNo ratings yet

- Design Science Research Methodology in Computer Science and Information SystemsDocument7 pagesDesign Science Research Methodology in Computer Science and Information SystemsDEBORA EIRENE H -deiNo ratings yet

- The Ontological, Epistemological and Methodological Debates in Information Systems Research: A Partial ReviewDocument23 pagesThe Ontological, Epistemological and Methodological Debates in Information Systems Research: A Partial ReviewLikassa LemessaNo ratings yet

- Haekokoversio PHPDocument20 pagesHaekokoversio PHPRABAB MASDOURNo ratings yet

- Bridging The Qualitative-Quantitative DivideDocument34 pagesBridging The Qualitative-Quantitative Divideprasenjit_baishyaNo ratings yet

- Applying Grounded Theory To Study The Implementation of An Inter-Organizational IsDocument13 pagesApplying Grounded Theory To Study The Implementation of An Inter-Organizational IsIyan GustianaNo ratings yet

- Bibliometric Analysis of Sla 1997 2018 Zhang 2019Document24 pagesBibliometric Analysis of Sla 1997 2018 Zhang 2019johnreyvin amaliasNo ratings yet

- تطبيقات الحاسوب ٢Document9 pagesتطبيقات الحاسوب ٢Rhma mhmoud Rhma mhmoudNo ratings yet

- Visualizing The Intellectual Structure of Information Science (2006-2015) : Introducing Author Keyword Coupling AnalysisDocument20 pagesVisualizing The Intellectual Structure of Information Science (2006-2015) : Introducing Author Keyword Coupling AnalysisEri ZuliarsoNo ratings yet

- Trends of E-Learning Research From 2000 To 2008 Use of TextDocument12 pagesTrends of E-Learning Research From 2000 To 2008 Use of TextAdrian SiebritzNo ratings yet

- The Shift Towards Multi-Disciplinarity in Information ScienceDocument15 pagesThe Shift Towards Multi-Disciplinarity in Information Sciencejolios85No ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Theory and Methodology in Learning Design ResearchDocument11 pagesChapter 5 - Theory and Methodology in Learning Design ResearchMike NallNo ratings yet

- Coherence and Transparency: Some Advice For Qualitative ResearchersDocument8 pagesCoherence and Transparency: Some Advice For Qualitative Researchersmiguel rosarioNo ratings yet

- Chen Hirschheim 2004Document39 pagesChen Hirschheim 2004Romika JainNo ratings yet

- Design Science Research As Research Approach in Doctoral StudiesDocument14 pagesDesign Science Research As Research Approach in Doctoral Studiesnromy2006No ratings yet

- Integrating The Grounded Theory Method and Case Study Research MeDocument13 pagesIntegrating The Grounded Theory Method and Case Study Research MePintu KrNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Operational Research: Leroy WhiteDocument15 pagesEuropean Journal of Operational Research: Leroy WhiteLucianoPradoNo ratings yet

- Hodgkinson, 2001, Realigning The Stakeholders in ManagementDocument8 pagesHodgkinson, 2001, Realigning The Stakeholders in ManagementfjsvasconcellosNo ratings yet

- 2015-Gallivan - Co-Authorship, Homophily, and Scholarly Influence in Information Systems ResearchDocument36 pages2015-Gallivan - Co-Authorship, Homophily, and Scholarly Influence in Information Systems ResearchLuckySaigonNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Information Technology On Identity: Framing The Research AgendaDocument20 pagesThe Impact of Information Technology On Identity: Framing The Research AgendaNach Hamid100% (2)

- Information Technology and The Humanities Scholar - Documenting Digital Research PracticesDocument14 pagesInformation Technology and The Humanities Scholar - Documenting Digital Research PracticesElanthamil PandiNo ratings yet

- Zach 551Document19 pagesZach 551apinporn chaiwanichsiriNo ratings yet

- Technological Forecasting & Social Change: Cong Cheng, Limin Wang, Hongming Xie, Lulu YanDocument18 pagesTechnological Forecasting & Social Change: Cong Cheng, Limin Wang, Hongming Xie, Lulu Yansohrab67No ratings yet

- Pilot Study in The Research ProcedureDocument9 pagesPilot Study in The Research ProcedureCaroline SantosoqNo ratings yet

- Taylorismo PDFDocument13 pagesTaylorismo PDFBrayan StivenNo ratings yet

- EJ1196755Document9 pagesEJ1196755Wen PamanilayNo ratings yet

- Gatekeeping: A Critical Review: Annual Review of Information Science and Technology January 2009Document64 pagesGatekeeping: A Critical Review: Annual Review of Information Science and Technology January 2009Mario HadiwijayaNo ratings yet

- New Evidence On Instrumental, Conceptual, and Symbolic Utilization of University Research in Government AgenciesDocument32 pagesNew Evidence On Instrumental, Conceptual, and Symbolic Utilization of University Research in Government AgenciesNatalia Bozo CarrilloNo ratings yet

- Cesis: How Can We Study Innovation Systems? - Introducing An Actor-Centralised PerspectiveDocument30 pagesCesis: How Can We Study Innovation Systems? - Introducing An Actor-Centralised PerspectiveRajesh KalarivayilNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Internet ResearchDocument19 pagesThe Ethics of Internet Researchagus maulanaNo ratings yet

- The Bibliometric Analysis of Scholarly Production How Great Is The ImpactDocument23 pagesThe Bibliometric Analysis of Scholarly Production How Great Is The ImpactapatzNo ratings yet

- Venkatesh Etal 2013 MISQDocument68 pagesVenkatesh Etal 2013 MISQLê ChiNo ratings yet

- Cho2017 Article IdentifyingInterdisciplinaryReDocument7 pagesCho2017 Article IdentifyingInterdisciplinaryRePhương VõNo ratings yet

- Australasian Journal of Information Systems Special Issue 2003/2004Document10 pagesAustralasian Journal of Information Systems Special Issue 2003/2004Amorsiko ExeNo ratings yet

- A Framework and Approach For Analysis of Focus Group Data in InfoDocument22 pagesA Framework and Approach For Analysis of Focus Group Data in InfoHoàng QuỳnhNo ratings yet

- Article The Identity Crisis Within The Is Discipline: Defining and Communicating The Discipline'S Core PropertiesDocument4 pagesArticle The Identity Crisis Within The Is Discipline: Defining and Communicating The Discipline'S Core PropertiesusmanNo ratings yet

- Armann Keown2020Document12 pagesArmann Keown2020willdalostoNo ratings yet

- El Estatus Científico Del Diseño InteligenteDocument25 pagesEl Estatus Científico Del Diseño InteligenteMarcos del RíoNo ratings yet

- Research Quality in Case Study Research Ates EURAM08Document35 pagesResearch Quality in Case Study Research Ates EURAM08Siva Sankara Narayanan SubramanianNo ratings yet

- Rakas 2019Document26 pagesRakas 2019farshidhatamabadiNo ratings yet

- Venkatesh Etal 2013 MISQDocument68 pagesVenkatesh Etal 2013 MISQSultan Haekal YusufNo ratings yet

- Examining Mobile Learning Trends 2003-2008 (2012)Document17 pagesExamining Mobile Learning Trends 2003-2008 (2012)IRFANNo ratings yet

- Trends in Educational Technology Through The Lens of The Highly Cited Articles Published in The Journal of Educational Technology and SocietyDocument18 pagesTrends in Educational Technology Through The Lens of The Highly Cited Articles Published in The Journal of Educational Technology and SocietyMarjorie Vecinal CaparasNo ratings yet

- Organizational and Institutional in Uences On Creativity in Scientific ResearchDocument14 pagesOrganizational and Institutional in Uences On Creativity in Scientific Researchmariana henteaNo ratings yet

- Chapter-16 (Mix Method)Document33 pagesChapter-16 (Mix Method)waqas farooqNo ratings yet

- Research Methods Content AnalysisDocument3 pagesResearch Methods Content Analysiskhusna asNo ratings yet

- The Information Search Process RevisitedDocument17 pagesThe Information Search Process RevisitedFiryal AdillaNo ratings yet

- Critical CaseDocument11 pagesCritical CasebuttsahibNo ratings yet

- In Pursuit of Systems Theories For Describing and Analyzing SysteDocument18 pagesIn Pursuit of Systems Theories For Describing and Analyzing SysteMaría José Cano ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Reusable Conceptual Models-Requirements Based On TDocument30 pagesReusable Conceptual Models-Requirements Based On Taust austNo ratings yet

- The Handbook of Social Work Research Methods Ebook PDF VersionDocument61 pagesThe Handbook of Social Work Research Methods Ebook PDF Versionlynn.anderson710100% (41)

- Choosing a Research Method, Scientific Inquiry:: Complete Process with Qualitative & Quantitative Design ExamplesFrom EverandChoosing a Research Method, Scientific Inquiry:: Complete Process with Qualitative & Quantitative Design ExamplesNo ratings yet

- Capital Markets Fundamentals - Ethiopian ContextDocument50 pagesCapital Markets Fundamentals - Ethiopian ContextHub TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 4th Assignment Case Study Business Application of Oracle TechDocument12 pages4th Assignment Case Study Business Application of Oracle TechHub TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 5th - Cloud Support For Large Scale E-Healthcare SystemsDocument7 pages5th - Cloud Support For Large Scale E-Healthcare SystemsHub TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 4 An Experimental Comparison of Two Machine Learning ApproachesDocument4 pages4 An Experimental Comparison of Two Machine Learning ApproachesHub TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 4 6044259754279176200Document3 pages4 6044259754279176200Hub TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 1 Inquiries, - Investigations - and - Immersion UpdatedDocument66 pages1 Inquiries, - Investigations - and - Immersion UpdatedMary Jane CadagueNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 - Introduction To PM JL PDFDocument41 pagesLecture 1 - Introduction To PM JL PDFthejas89No ratings yet

- Mental Health Among Jail and Prison InmatesDocument10 pagesMental Health Among Jail and Prison InmatesdehamericoNo ratings yet

- Parenting SkillsDocument97 pagesParenting SkillsSaqib BajwaNo ratings yet

- Biniyam BerhanuDocument84 pagesBiniyam Berhanutinsae beyeneNo ratings yet

- Final Dissertation GuidelinesDocument16 pagesFinal Dissertation GuidelinesArpita SenNo ratings yet

- The Role of School Board, School Heads and Parent-Teachers Association in The Effective Management of Public SchoolsDocument8 pagesThe Role of School Board, School Heads and Parent-Teachers Association in The Effective Management of Public SchoolsAbifarin OlamideNo ratings yet

- Nancy Kutama ProposalDocument18 pagesNancy Kutama Proposaljitha nipunikaNo ratings yet

- Brand Identity Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesBrand Identity Literature Reviewc5rn3sbr100% (1)

- Intro Page - Community Health ProjectDocument3 pagesIntro Page - Community Health Projectapi-467110214No ratings yet

- Complete Research ProposalDocument10 pagesComplete Research ProposalZamaraNo ratings yet

- Vision MissionDocument2 pagesVision MissionmanmohansinghloteyNo ratings yet

- Listening Practice Test 2Document16 pagesListening Practice Test 2Tareq Abu NazifNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesLiterature ReviewSyed FaisalNo ratings yet

- Topic About Engineering Research PaperDocument6 pagesTopic About Engineering Research Paperscxofyplg100% (1)

- Soc 101 Course OutlineDocument6 pagesSoc 101 Course OutlineBusayna AlamNo ratings yet

- Twitter Civil Activisms and EndSARS Protest in Nigeria As A Developing DemocracyDocument23 pagesTwitter Civil Activisms and EndSARS Protest in Nigeria As A Developing DemocracyMajestyNo ratings yet

- National Workshop On Block Designs and Their Applications: University For Women, University With A DifferenceDocument6 pagesNational Workshop On Block Designs and Their Applications: University For Women, University With A DifferenceMukesh BishtNo ratings yet

- Practical Research1 - Q1 - M4-Differentiating Quantitative From Qualitative ResearchDocument13 pagesPractical Research1 - Q1 - M4-Differentiating Quantitative From Qualitative ResearchKaye ToledanaNo ratings yet

- Chapter-3 Research About FinancialchuchuDocument4 pagesChapter-3 Research About FinancialchuchuNyl ViduaNo ratings yet

- Social Project by Lokesh & SwatiDocument48 pagesSocial Project by Lokesh & SwatiLokesh BhoiNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 The Research ProcessDocument2 pagesLesson 2 The Research ProcessMarkChristianRobleAlmazanNo ratings yet

- Social Media Marketing in Hospitality IndustryDocument16 pagesSocial Media Marketing in Hospitality IndustryIvan MungungeyoNo ratings yet

- Adult Smoking Habits in The UKDocument16 pagesAdult Smoking Habits in The UKRaquelle MasoudiNo ratings yet

- Research Timeline: Assessing Second Language Speaking: TH THDocument37 pagesResearch Timeline: Assessing Second Language Speaking: TH THDrGeePeeNo ratings yet

- Sarfraz Ahmed PHD Thesis Foundation University RawalpindiDocument260 pagesSarfraz Ahmed PHD Thesis Foundation University RawalpindiazharjavedNo ratings yet

- Web Digital Hydra Full 16nov PDFDocument85 pagesWeb Digital Hydra Full 16nov PDFNope nopeNo ratings yet

- Allwright - Integrating Training and Development - The Role of ResearchDocument17 pagesAllwright - Integrating Training and Development - The Role of ResearchTatiany Pertel Sabaini DalbenNo ratings yet

- Online GamingDocument21 pagesOnline Gamingarrow3966692marklloydNo ratings yet

- My CV pt2Document3 pagesMy CV pt2api-649148533No ratings yet