Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Reason Ehy Uk Economy Need Plan B

The Reason Ehy Uk Economy Need Plan B

Uploaded by

ekwonnaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Reason Ehy Uk Economy Need Plan B

The Reason Ehy Uk Economy Need Plan B

Uploaded by

ekwonnaCopyright:

Available Formats

THE REASON EHY UK ECONOMY NEED PLAN B

For several months, George Osborne has vigorously defended Plan A that includes 130m in cuts to public expenditure over five years, a scale unprecedented since the 1930s. In doing so, many have given him the benefit of the doubt, but no more. The imminent quarterly figures for growth are likely to signal yet again that the economy is flatlining. Now, a diverse range of organisations and individuals both secular and religious; on the left and on the right; drawn from the City and business; from the trade unions and from the international ranks of economists and academics is increasingly speaking as one. What they demand is the formulation of a Plan B. And fast. The voices are not all in accord on what Plan B might constitute. How to diversify and rebalance the economy; how to promote growth and how to restore ethics, mutualism and a sense of fair play to an economy and society does not easily command a consensus. However, we are witnessing an important shift. There is an awareness that a "business as usual" approach is no longer acceptable. The Observer welcomes this change of direction and the initiation of a debate that could prove historic in the salvaging and reshaping of our economy and the resetting of our national priorities for years to come. A letter is published today in the Observer from 100 renowned academics and economists. They point out that the UK jobless total is at its highest for 17 years. Dr HaJoon Chang and others warn starkly: "If the government persists with Plan A the deficit could rise, not fall." This prediction comes in the wake of several days of abysmal news. The pay of FTSE directors enjoyed a rise of up to 49% last year; by contrast, in the last quarter, the financial wellbeing of the average family fell at the fastest rate for 14 years. Another study has found families were 15 a week worse off in September 2011 than in the same month the year before. In addition, small to medium companies, the engine of a country's growth, have struggled to find financing. In spite of 275bn in quantitative easing (QE) given to the banks since 2009 to encourage them to lend, the proportion of small businesses turned down for bank finance quadrupled between 2007 and 2010; this shameful rejection rate is among the highest in Europe. It is hardly surprising that issues such as accountability and morality are now also part of the economic debate. In "Plan B: A Good Economy for a Good Society", published by Compass, a left-ofcentre pressure group, the extent of Plan A's cuts is described as "an act of economic sadomasochism". The report argues that Plan A is based on a false set of assumptions. The country is neither bankrupt nor has it "maxed out on credit cards". Some of the measures in this Plan B echo the proposals outlined by the 100 economists. They include reversing some cuts to save public sector jobs; the use of QE to invest in a green new deal; increased benefits for those on lower and middle incomes to stimulate demand and the creation of a British investment bank to leverage and back investment in low-carbon sectors such as housing, transport and renewable energy. What neither mention and

which, in our reckoning, deserves consideration is an investment in highly subsidised good-quality childcare to boost employment, support child development, reduce benefits and increase tax revenue. The umbrella group's Plan B rejects one of the five points put forward by Ed Balls, the Labour shadow chancellor, in his version of Plan B, namely a cut in VAT. The report argues that this would benefit the better-off most. Indeed, in this burgeoning debate, some might argue that Ed Balls's solution to the economic crisis is set in the same mould as that which has influenced fiscal policy for the past several decades. What the Compass report calls for is far more radical and challenging. It rightly calls for an end to the short-termism of the high-debt, low-wage, low-investment economy. Instead, if citizens are to "flourish", they require reasonable health, income and a value placed on the development of aspiration and an appreciation of a sense of self-worth, not just net worth. (According to the charity, the Sutton Trust, improving social mobility could bring 140bn a year to the economy.) Some may profoundly disagree with elements of these options to Plan A. However, the vigour of this debate offers not only practical solutions, it also brings with it a muchneeded optimism. It challenges the view that we live in a post-hope era. On the contrary, it reminds us that growth, although struggling, is not entirely absent from the British landscape. David Cameron has set out his own commitment to a more balanced economy with greater growth coming from the non-financial sectors, "the industries of the future", including the creative industries. The latter, embracing fashion, textiles, communications, music and technology, already account for 6% of UK GDP, employ more than 2 million people and bring in more than 17bn a year in exports. In independent television production, there has been a 34% increase in export growth in the past 12 months. The barriers facing the creative industries capture in miniature the challenges facing the economy as a whole in trying to establish growth that is more evenly shared across Britain and between industries. There is a need for better access to finance and greater support for innovation. One study discovered that the common link in the 11,000 highly diverse companies that created 54% of the new jobs (2002-8) was that commitment to innovation. Government and local authorities have also played a part in the growth of creative industries by protecting international property (IP) for instance and investing in clusters of industries (a route that is vital for the north). Manchester, for example, is one of Europe's largest creative and digital and media hubs. Any Plan B must recognise that government has to play an active social and economic role in, for instance, providing infrastructure, tax incentives, in regulating and, when necessary, in deregulating and by investing in research and development. Not all can be left to market forces.

So, while Mr Osborne may still be reluctant to talk about Plan B, or even Plan A Plus, that doesn't mean the rest of us can afford to stay mute. As our columnist Will Hutton has argued in these pages many times, and in his latest book, Them and Us, it is imperative that we consider not just the value of economic growth, but also the values that underpin it. Now is the time for each of us to lend our support to the voices attempting to shape our new model economy. WRITTEN BY: Onyekachi Ekebere

You might also like

- Back To Black: Budget 2009 PaperDocument44 pagesBack To Black: Budget 2009 PaperLuke BaileyNo ratings yet

- Orthopedic Hospital PlanningDocument7 pagesOrthopedic Hospital Planningሀይደር ዶ.ርNo ratings yet

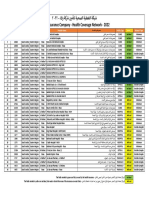

- Walaa Network 2022 شبكة التغطية الصحية-تامين شركة ولاءDocument1 pageWalaa Network 2022 شبكة التغطية الصحية-تامين شركة ولاءMohammed SulimanNo ratings yet

- GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History - Revised and expanded EditionFrom EverandGDP: A Brief but Affectionate History - Revised and expanded EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (20)

- Adras32 UserManualDocument93 pagesAdras32 UserManualnixon_b_2000100% (1)

- Compass Plan B WebDocument42 pagesCompass Plan B WebZain SardarNo ratings yet

- Time For A Plan C - Slow Growth and Fiscal ChoicesDocument12 pagesTime For A Plan C - Slow Growth and Fiscal ChoicesThe RSANo ratings yet

- Five Ideas For A Budget For GrowthDocument8 pagesFive Ideas For A Budget For GrowthIPPRNo ratings yet

- Plan C - Shaping Up To Slow GrowthDocument11 pagesPlan C - Shaping Up To Slow GrowthThe RSANo ratings yet

- Five Ideas For A Budget For Growth: Laura ChappellDocument8 pagesFive Ideas For A Budget For Growth: Laura ChappellIPPRNo ratings yet

- Finance and InvestmentDocument4 pagesFinance and InvestmentThảo PhươngNo ratings yet

- Tim Morgan Report 007Document34 pagesTim Morgan Report 007alastair82sNo ratings yet

- Working Paper Number 129 Tax Evasion, Tax Avoidance and Development FinanceDocument20 pagesWorking Paper Number 129 Tax Evasion, Tax Avoidance and Development FinanceFeby Anggraeni TanjungNo ratings yet

- In The Black LabourDocument5 pagesIn The Black LabourZain SardarNo ratings yet

- Generational Accounting in The Uk: NOVEMBER2000Document28 pagesGenerational Accounting in The Uk: NOVEMBER2000Bayarmaa OdonNo ratings yet

- Tullett Prebon Project Armagedon Aug 2011Document34 pagesTullett Prebon Project Armagedon Aug 2011SwamiNo ratings yet

- Current Priorities of GovernmentDocument1 pageCurrent Priorities of Governmentviktor6No ratings yet

- 02 Mazzucato 2013 TheEntrepreneurialStateDocument40 pages02 Mazzucato 2013 TheEntrepreneurialStateIvana MaubachNo ratings yet

- 07neal Lawson and John Harris 'No Turning Back'Document4 pages07neal Lawson and John Harris 'No Turning Back'steve_yemmNo ratings yet

- Economic Function of Government - Presentation Transcript: Business-To-Government (B2G) Is A Derivative ofDocument20 pagesEconomic Function of Government - Presentation Transcript: Business-To-Government (B2G) Is A Derivative ofaditibrijptlNo ratings yet

- 2014 04 23 Speech Spectator - PressDocument12 pages2014 04 23 Speech Spectator - PressPolitical AlertNo ratings yet

- The Big Society - Telegraph 20-02-11Document3 pagesThe Big Society - Telegraph 20-02-11shamn15No ratings yet

- Economic Situation in EnglandDocument3 pagesEconomic Situation in EnglandAnıl AlbayrakNo ratings yet

- Investing in The FutureDocument13 pagesInvesting in The FuturekkarajanevaNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Current Status/situation: Push Europe 6 Million New Jobs Could Be Created in EuropeDocument2 pagesSummary of The Current Status/situation: Push Europe 6 Million New Jobs Could Be Created in EuropeEllie HopkinsNo ratings yet

- Banks 2018Document15 pagesBanks 2018Teguh HariyantoNo ratings yet

- 2010 Statement of Labour Leaders To The World Economic Forum Annual MeetingDocument5 pages2010 Statement of Labour Leaders To The World Economic Forum Annual Meetinganthony.blancoNo ratings yet

- Austerity Measures: Video: Political News of The Day - 60 Secs at A TimeDocument9 pagesAusterity Measures: Video: Political News of The Day - 60 Secs at A TimeLalitha SurasgarNo ratings yet

- A New Macroeconomic Strategy WebReady FinalDocument36 pagesA New Macroeconomic Strategy WebReady FinalHeathwoodPressNo ratings yet

- Portugal A European Path Out of AusterityDocument14 pagesPortugal A European Path Out of Austeritygfrutosmiranda_75834No ratings yet

- New Uk Economic StrategyDocument4 pagesNew Uk Economic Strategyjawadahmed7854No ratings yet

- Commerce 3rd Yr Bcom Hons Econ DevtDocument41 pagesCommerce 3rd Yr Bcom Hons Econ DevtvermaashleneNo ratings yet

- Deutsche Bank 2006 Measures of Well BeingDocument11 pagesDeutsche Bank 2006 Measures of Well BeingLilian MaNo ratings yet

- EC6201 International EconomicsDocument4 pagesEC6201 International EconomicsutahgurlNo ratings yet

- What Are The Millennium Development Goals?Document5 pagesWhat Are The Millennium Development Goals?Cheryl TayNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy in A Pandemic EmergencyDocument6 pagesMonetary Policy in A Pandemic EmergencyTrần ThiNo ratings yet

- Articles GlobalizationDocument20 pagesArticles Globalizationmeeru360No ratings yet

- One Nation EconomyDocument60 pagesOne Nation EconomyDr. Geoffrey A. WalkerNo ratings yet

- English Project Răducu Elena Nicole CSIE Grupa 1024Document9 pagesEnglish Project Răducu Elena Nicole CSIE Grupa 1024ile 06No ratings yet

- Meso-Economics, New Public Enterprise and Economic PlanningDocument14 pagesMeso-Economics, New Public Enterprise and Economic PlanningarsemNo ratings yet

- Eco ReadingsDocument3 pagesEco ReadingsnoviceNo ratings yet

- Will Davies FutureDocument10 pagesWill Davies FutureaghlaniserverNo ratings yet

- A Major Wave of UK Business Closures by April 2021? The Scale of The Problem and What Can Be DoneDocument27 pagesA Major Wave of UK Business Closures by April 2021? The Scale of The Problem and What Can Be DoneMuhammad MuaviaNo ratings yet

- Euro Crisis ThesisDocument5 pagesEuro Crisis Thesisangeljordancincinnati100% (2)

- Deficit Reduction, The Age of Austerity, and The Paradox of InsolvencyDocument21 pagesDeficit Reduction, The Age of Austerity, and The Paradox of InsolvencyheraklisNo ratings yet

- Essay On Globalisation and Inequality PDFDocument3 pagesEssay On Globalisation and Inequality PDFArqam WaqarNo ratings yet

- Defisit Budget UKDocument10 pagesDefisit Budget UKMonika br GintingNo ratings yet

- 06-06-11 - EOTM - Occam's RazorDocument5 pages06-06-11 - EOTM - Occam's Razorlee_ankitNo ratings yet

- The Growth Theories: Prepared By: Mary Jane Araos Erlyn Garcia Mary Grace Latorre Trisha Anne OlivaDocument60 pagesThe Growth Theories: Prepared By: Mary Jane Araos Erlyn Garcia Mary Grace Latorre Trisha Anne OlivaJennifer Dela RosaNo ratings yet

- How The West Fell Out of Love With Economic Growth - The EconomistDocument8 pagesHow The West Fell Out of Love With Economic Growth - The EconomistDito InculoNo ratings yet

- International Solidarity Levy Network: Busting The Myths About The Financial Transactions TaxDocument3 pagesInternational Solidarity Levy Network: Busting The Myths About The Financial Transactions Taxapi-90502001No ratings yet

- Thesis Statement On Economic GrowthDocument5 pagesThesis Statement On Economic Growthvictoriathompsonaustin100% (2)

- Economic Development and Economic GrowthDocument4 pagesEconomic Development and Economic GrowthIrish NashiNo ratings yet

- CaseDocument4 pagesCaseprateek bhandariNo ratings yet

- Devlopment Eco 2Document7 pagesDevlopment Eco 2Gwahram BalochNo ratings yet

- The Washington Consensus: Winter 2010/2011Document20 pagesThe Washington Consensus: Winter 2010/2011Lê Phan Anh ThưNo ratings yet

- Americ Is Not BrokeDocument20 pagesAmeric Is Not Brokechirese2000No ratings yet

- User's and Maintenance Manual: Franke Finland OyDocument19 pagesUser's and Maintenance Manual: Franke Finland OyRomário Caribé100% (1)

- Butterfly HouseDocument5 pagesButterfly HouseViral PatelNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Syllabus CompleteDocument4 pagesLegal Ethics Syllabus CompletejessieNo ratings yet

- 75kw Cummins 6bt5.9-g2Document4 pages75kw Cummins 6bt5.9-g2Sarpras RSIMNo ratings yet

- UNIT VI Government Grants Borrowing CostsDocument4 pagesUNIT VI Government Grants Borrowing CostsJi Eun VinceNo ratings yet

- Strategic Plan For The Dem PartyDocument7 pagesStrategic Plan For The Dem Partyapi-255139145100% (1)

- EB 06 LightingDocument45 pagesEB 06 LightingTamNo ratings yet

- Fronter RebuttalsDocument4 pagesFronter RebuttalsDayna Dyandra Arias PazNo ratings yet

- The Four Dimensions of Public Financial ManagementDocument9 pagesThe Four Dimensions of Public Financial ManagementInternational Consortium on Governmental Financial Management100% (2)

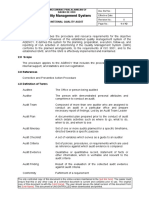

- 3 Internal Quality AuditDocument12 pages3 Internal Quality AuditJeaneth Dela Pena CarnicerNo ratings yet

- ISO 45001:2018 Migration Self-Assessment Guide: How Ready Are You For ISO 45001?Document16 pagesISO 45001:2018 Migration Self-Assessment Guide: How Ready Are You For ISO 45001?Vikas SinghNo ratings yet

- People's Dome Cad File-A1Document1 pagePeople's Dome Cad File-A1Macoy CarandangNo ratings yet

- Scheduling Practice ProblemsDocument2 pagesScheduling Practice ProblemsM ThuNo ratings yet

- Concrete Technology Homework 2 PDFDocument3 pagesConcrete Technology Homework 2 PDFXiaoman TuNo ratings yet

- Taxation Management AssignmentDocument11 pagesTaxation Management AssignmentniraliNo ratings yet

- Tingkat Stres Dan Kualitas Tidur Mahasiswa: Keywords: Level of Stress, Stress Management, Sleep QualityDocument6 pagesTingkat Stres Dan Kualitas Tidur Mahasiswa: Keywords: Level of Stress, Stress Management, Sleep QualityJemmy KherisnaNo ratings yet

- ProduseDocument996 pagesProdusezippe srlNo ratings yet

- Dell Powerstore 3 0 SpecDocument9 pagesDell Powerstore 3 0 SpecbilashsNo ratings yet

- Eng Cressi Manu 03842Document7 pagesEng Cressi Manu 03842Marin PintarNo ratings yet

- R Eugp1 TPT P 000 Gen Man 003 R01Document94 pagesR Eugp1 TPT P 000 Gen Man 003 R01debapriyoNo ratings yet

- M-Class Parts Catalog 92-2505-01 EDocument24 pagesM-Class Parts Catalog 92-2505-01 EjNo ratings yet

- Drip Torch DUCOTSDocument6 pagesDrip Torch DUCOTSQBMontgomeryNo ratings yet

- MCKEE vs. IACDocument3 pagesMCKEE vs. IACJohnny EnglishNo ratings yet

- Total Quality ManagementDocument55 pagesTotal Quality Managementss100% (2)

- First Aid Android ApplicationDuc - Chapter 1 4Document26 pagesFirst Aid Android ApplicationDuc - Chapter 1 4paul francoNo ratings yet

- IIM Calcutta - Job Description Form - Summers 2019: Name of The CompanyDocument2 pagesIIM Calcutta - Job Description Form - Summers 2019: Name of The CompanyVaishnaviRaviNo ratings yet

- Hiệu part3Document4 pagesHiệu part3Đỗ Đại HọcNo ratings yet