Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Truth On Expanded Esc-Evidence Based Response

Truth On Expanded Esc-Evidence Based Response

Uploaded by

WSLSOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Truth On Expanded Esc-Evidence Based Response

Truth On Expanded Esc-Evidence Based Response

Uploaded by

WSLSCopyright:

Available Formats

Thursday, February 29, 2024

Re: Misleading Claims on Expanded Earned Sentence Credits

Dear Members of the General Assembly,

We write to you to ask that the General Assembly adopt the House Budget language striking Item

390(R)(2), fully enacting expanded Earned Sentence Credits legislation passed in the 2021 General Assembly

Special Session.

Summary

Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares’ letter to the General Assembly dated February 27, 2024, regarding the

Enhanced Earned Sentence Credit (EESC) program distorts the data and provides an inaccurate analysis of the

public safety and fiscal impacts of the program in an attempt to justify continued restrictions on eligibility for

enhanced credits.

Virginia remains among the safest states in the union. The violent crime rate in Virginia in 2022 was over 38%

lower than the national average.1 In fact, earned sentence credit systems have been found to reduce recidivism and

improve work opportunities in rigorous comparisons,2 including following the recent federal First Step Act.3

Expanding earned sentence credits has generated millions in savings already, driving the reduction of Virginia’s

prison population by more than 2,000 and facilitating the closure of four prisons.4 Honest accounting indicates

that eliminating the budget amendment will save at least $28 million and as much as $118 million, money that we

encourage the Commonwealth to invest in Virginia Victim Services Network and Virginia Sexual and Domestic

Violence Action Alliance and evidence-based public safety and rehabilitation efforts.

The fact that the population of people ineligible for EESCs have had a lower recidivism rate than those who are

eligible for EESCs is precisely why the Commonwealth would benefit from expanding the EESC program – and

the incentives for rehabilitation that it provides – to everyone in VADOC custody.

The legislature has recognized as much in recent legislative sessions by defeating each and every bill aimed at

codifying the budget language restrictions in whole or in part. This demonstrates that the legislature has

already made a determination against the language in the governor’s budget. To allow the language to

remain would short-circuit the legislative process and undermine the legitimacy of the body.

1

FBI Crime Data Explorer. Violent Crime Trend in Virginia 2022.

https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend

2

Lawrence, Alison (2009). ”Cutting Corrections Costs: Earned Time Policies for State Prisoners 2,” Nat’l Conf. of State Legislatures.

3

Bhati, Avinash (2023). “First Step Act: An Early Analysis of Recidivism.” Council on Criminal Justice (August).

https://counciloncj.foleon.com/first-step-act/fsa/

4

Weston, Helen (January 26, 2024). “Under Governor Youngkin, Prison Reform is Working.” Richmond Times-Dispatch.

https://richmond.com/opinion/column/commentary-under-gov-youngkin-prison-reform-is-working/article_c87eefe0-b952-11ee-a8f2-67

f40241ffea.html

www.thehumanizationproject.org 808.292.8731 taj@thehumanizationproject.org

As set out below, the Attorney General has failed to make a convincing argument for the continued limitation of

the EESC program. Eliminating Item 390(R)(2) from the state budget will not harm public safety, and it will

generate cost savings and respect the will of the legislature.

Public Safety

Recidivism

The Attorney General’s claim that the EESC program should not be expanded because people who are eligible for

it are more likely to recidivate is both deeply flawed and misleading.

Firstly, the Attorney General claims that in FY23 three people released under EESC were rearrested for capital

murder. The Commonwealth of Virginia abolished capital murder in 2021, well before anyone was released as a

result of EESCs upon its enactment in 2022. It is disappointing that Virginia’s top law enforcement officer would

publicly claim that people were arrested for a crime that no longer exists.

Beyond this factual error, the Attorney General’s discussion of recidivism implies that the EESC program is

responsible for increased recidivism. The Attorney General supplies no evidence to support this claim and

fails to account for multiple variables that are known to impact recidivism. These flaws render the Attorney

General’s conclusions inaccurate and unreliable.

Notably, the Attorney General does not provide any evidence that the recidivism rate for people with

EESC-eligible offenses increased after implementation of the EESC program. The comparison of recidivism rates

of EESC-eligible offenses and non-EESC-eligible offenses is misleading, because it is well-established that

EESC-eligible offense categories have higher recidivism rates. For example, the April 2021 Recidivism study

states plainly that “Inmates who commit Property or Public Order crimes as their most serious offenses are more

likely to recidivate.”5

In fact, some of the offenses associated repeatedly with the lowest recidivism risk, as confirmed by Department of

Corrections’ researchers, are offenses such as homicide in the first and second degree, manslaughter, and arson —

offenses that are currently excluded from eligibility for EESCs.6 Thus, the Attorney General’s letter simply

identifies a pattern that existed before the implementation of the EESC program and continues today.

Academic research7 and the Department of Corrections8 have both identified factors that are associated with

increased recidivism, like youth and untreated Substance Use Disorder. Both of those traits are inherently more

common among the drug, property, and public order convictions that are the vast majority of EESC-eligible

sentences. Suggesting that increased recidivism is attributable to the EESC program is inaccurate and

entirely unsupported by the data cited by the Attorney General.

If the Attorney General prefers that the incentives toward rehabilitation provided by the EESC program be

extended to those with the lowest recidivism risk, he should join us in seeking to extend the program to everyone,

rather than curtailing it further. The Commonwealth could then reinvest the savings generated by the EESC

program into programs that prioritize treatment, restorative justice, and job training to further reduce the chance of

recidivism.

5

VADOC Research-Evaluation Unit (2021), “VADOC Recidivism” (April).

https://vadoc.virginia.gov/media/1683/vadoc-recidivism-summary-report-2021-04.pdf

6

https://vadoc.virginia.gov/media/1783/vadoc-recidivism-crime-type-over-time-report-2022.pdf

7

Huebner, B. M. (2006). Drug abuse, treatment, and probationer recidivism. Chicago: Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority

8

https://vadoc.virginia.gov/media/1783/vadoc-recidivism-crime-type-over-time-report-2022.pdf

www.thehumanizationproject.org 808.292.8731 info@thehumanizationproject.org

Technical violations are not new crimes

The Attorney General’s letter exaggerates the significance of the arrest statistics for EESC-eligible people who

have been released, because those statistics include arrests for technical probation violations, which are not new

crimes.

The letter collectively describes 1,569 new arrests for EESC releases, but does not specify how many of these

alleged violations are technical probation violations, which include such minor actions as lying (about anything)

to a probation officer, not reporting a change of address immediately, or missing a meeting with a probation

officer. Researchers have found that technical violations without new crimes are the most common reason

people are rearrested.9 Technical violations alone account for 30% of rearrests, six times as many as all violent

felony rearrests combined.

Further, the number of arrests says nothing about the number of convictions that result. Arrests are far more

common than convictions: for example, in FY21, there were 979 robbery arrests in Virginia,10 but just 190

convictions for robbery as a primary offense.11 Many people who are arrested for crimes are never charged at all,

later have the charges dropped, or are found innocent.

Not only do the arrest statistics that the Attorney General cites fail to make the case against the EESC program,

but his letter drastically distorts the data to exaggerate the risk of recidivism from the EESC program.

COMPAS is a biased and inaccurate system

The Attorney General’s analysis of the COMPAS risk assessment scores for people released under EESC fails to

acknowledge the flaws and biases repeatedly associated with the system. The COMPAS assessment has been

shown to have a strong racial bias, disproportionately assigning crime risk to people of color. “African Americans

were more likely than Caucasians to be given higher scores regardless of their recidivism rates,” as Dartmouth

College researchers found in 2018, 12 when in fact African Americans are more likely to not recidivate relative to

their scores.

The COMPAS system’s predictions of criminal behavior overall have also been demonstrated to be unreliable.

Researchers who directly compared its predictions with those of laypeople found that “COMPAS is no more

accurate or fair than predictions made by people with little or no criminal justice expertise.” 13

Even if COMPAS were an accurate system, the Attorney General fails to offer analogous information on

COMPAS scores for those who were not released on EESCs, making a meaningful comparison impossible.

Fiscal Impact

9

CSOSA Congressional Budget Justification Fiscal Year 2021 (2020), “Community Supervision Program.” Court Services and Offender

Supervision Agency.

https://www.csosa.gov/wp-content/uploads/bsk-pdf-manager/2020/02/CSP-FY2021-Congressional-Budget-Justification-02062020.pdf#

page=22

10

Virginia State Police Public Reporting Site. Robbery Arrests Q3 2020 - Q2 2021,

https://va.beyond2020.com/va_public/View/dispview.aspx

11

Virginia Criminal Sentencing Commission, Interactive Sentencing Event Dashboard, FY19-21.

https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/vacrimsentcommission/viz/2019-2021SentencingEventDashboard/InteractiveStoryboard

12

Julia Dressel,Hany Farid. The accuracy, fairness, and limits of predicting recidivism.Sci.

Adv.4,eaao5580(2018).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aao5580

13

Julia Angwin, Jeff Larson, Surya Mattu, Lauren Kirchner. Machine Bias. Pro Publica. May 23, 2016.

https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing

www.thehumanizationproject.org 808.292.8731 info@thehumanizationproject.org

VADOC’s original assumed implementing the EESC program would cost the taxpayer approximately $7.3 million

annually, but the legislature subsequently removed almost $4 million of implementation funding from the budget.

SB30 currently proposes recouping 21 unnecessary and unfilled reentry FTEs and four IT-related positions that

were originally allotted for implementation of the more complicated ESC expansion (Item 390(6)(S) ). Clearly,

the costs of implementing the program are overstated.

Further, eliminating Item 390(R)(2) will generate substantial cost savings during the biennium – $28.4

million in direct costs at least – by releasing additional incarcerated people.

According to the Department of Corrections, “direct inmate costs…are the expenditures that vary in direct

proportion to the population.” In other words, direct inmate costs like food and medical expenditures are the

marginal burden of incarcerating a single additional person. In FY22, total direct inmate costs were $237,548,200

over an average daily population of 23,288, equaling $27.95 per person in daily direct expenditures by the

department. Every month a person is released sooner than expected will reduce the cost to the department

by $838.50 in direct costs.14

We estimate that approximately 2,160 people would be released during the biennium if Item 390(R)(2) were

removed from the budget, making the cost savings in “direct inmate costs” alone (e.g. food, medical, etc.)

approximately $28.4 million during the biennium.

Saving Model 1 - “Direct Inmate Cost” Savings

Releases15 Year 1 Savings Year 2 Savings Biennial Savings

Immediate - 560 $5,712,255 $5,712,255 $11,424,510

Year 1 - 800 $4,420,208 $8,160,364 $12,580,572

Year 2 - 800 $0 $4,420,208 $4,420,208

Total - 2160 $10,132,463 $18,292,827 $28,425,290

Savings in direct inmate costs do not take into account additional savings that could be achieved by reducing fixed

costs, such as closing additional VADOC facilities (and eliminating corresponding energy bills, facility

maintenance, etc.). This scenario would substantially increase actual cost savings.

The total departmental expenditures, which include “direct inmate costs” and fixed costs, are $42,432 per

person.16 This equals $116.25 per person in daily direct expenditures by the department. Assuming the closure of

additional facilities, the maximum cost savings to the department could be as high as $118.2 million over

the biennium.

Saving Model 2- Total (“Direct Inmate” and Fixed) Cost Savings 17

Releases Year 1 Savings Year 2 Savings Biennial Savings

Immediate - 560 $23,761,920 $23,761,920 $47,523,840

14

VADOC FY22 Annual Report, Page 16. https://vadoc.virginia.gov/media/1813/vadoc-financial-annual-mis-report-2022.pdf

15

Denise Lavoie and Sarah Rankin, Virginia law stops early inmate releases, angering families. Associated Press. July 4,

2022. https://apnews.com/article/entertainment-prisons-virginia-robert-ford-f8dde969ef981c58174704258e24cc54

16

VADOC FY22 Annual Report, Page 11. https://vadoc.virginia.gov/media/1813/vadoc-financial-annual-mis-report-2022.pdf

17

First-year savings in both models for non-immediate releases assume a flat release rate per month and a release rate of 10% of the

eligible population each year. This equals 66.67 people released each month. People released during the first month of the Fiscal

Year accrue savings for the entire year. People released in the second month accrue savings for 11 months, etc.

www.thehumanizationproject.org 808.292.8731 info@thehumanizationproject.org

Year 1 - 800 $18,387,200 $33,945,600 $52,332,800

Year 2 - 800 $0 $18,387,200 $18,387,200

Total - 2160 $42,149,120 $76,094,720 $118,243,841

Conclusion

A closer look at the evidence presented by the Attorney General refutes the notion that the current implementation

of EESC has had any detrimental impact on public safety. Closer examination of the fiscal considerations shows

that rather than extreme cost burdens, substantial net savings can be reliably expected.

Consequently, the statement from the Attorney General is both a misleading representation of incomplete data

and clear evidence of an agenda against incentives for rehabilitation, a proven method of improving public safety

and saving taxpayer funds.

Already, the limited expansion of earned sentence credits has produced positive systemic change in Virginia’s

justice system. Virginia has led the nation in decarceration 18 since its enactment, reuniting thousands of

families, expanding the workforce, and strengthening communities, even as Virginia remains one of the safest

states in the nation. Hundreds of millions of dollars will be available for more beneficial purposes than extended

human warehousing because EESC’s enactment has driven the closure of four prisons.

Most importantly, EESCs have incentivized active rehabilitation. Thousands of people behind bars have been

inspired to engage in the rehabilitation that keeps all of us safer and makes fewer victims.

Lawmakers across the aisle agree that earned sentence credits are sound policy. Earned credits were a hallmark of

the First Step Act in 2018, passed with strong bipartisan support and signed into law by President Trump. Since

then, analysis by the Council on Criminal Justices finds that “[r]ecidivism rates were 37% lower for people

released under the FSA.”19

Experts across the ideological spectrum agree: the Nolan Center for Justice calls earned sentence credits a “public

safety force multiplier,” 20 explaining “[a]llowing people in prison to earn time off their sentences by engaging in

educational programs, workforce training, mental health treatment, or other proven rehabilitative programs

increases community safety, keeps prisons more secure, ensures correctional staff safety, and allows taxpayer

dollars to be used more efficiently.”

Not only should we avoid artificially limiting those benefits, but the Commonwealth should actively extend those

incentives to those with “mixed charges” and everyone else who will eventually rejoin society.

Expanding earned sentence credits is principled, evidence-based policy. It’s shameful to see the Attorney General

attempt to represent it as otherwise.

18

Bureau of Justice Statistics (2023). “Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical Tables,” NCJ 307149. https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/p22st.pdf

19

Bhati, Avinash (2023). “First Step Act: An Early Analysis of Recidivism.” Council on Criminal Justice (August).

https://counciloncj.foleon.com/first-step-act/fsa/

20

Nolan Center for Justice (2022). “Expanding the Use of Earned Credits in Prison Increases Public Safety.”

https://conservativejusticereform.org/expanding-the-use-of-earned-credits-in-prison-increases-public-safety/

www.thehumanizationproject.org 808.292.8731 info@thehumanizationproject.org

You might also like

- ORDER Judge Greg Mooney On Natural Bridge ZooDocument7 pagesORDER Judge Greg Mooney On Natural Bridge Zookaitlyn.dillonNo ratings yet

- Wawa RT 29 & Lawyers RD Site Plan Rev 0Document32 pagesWawa RT 29 & Lawyers RD Site Plan Rev 0Caitlyn FroloNo ratings yet

- Response From DA Torrez To LFC MemoDocument19 pagesResponse From DA Torrez To LFC MemoAlbuquerque JournalNo ratings yet

- 2021-8-10 Commutation Release and Subsequent Criminal CasesDocument10 pages2021-8-10 Commutation Release and Subsequent Criminal CasesDustin VogtNo ratings yet

- Challenges Facing Comparative Criminal Justice ResearchDocument18 pagesChallenges Facing Comparative Criminal Justice ResearchMartin DuffyNo ratings yet

- Social Policy BriefDocument6 pagesSocial Policy BriefRebecca SmithNo ratings yet

- Preventing Crime What Works, What Doesn't, What's PromisingDocument633 pagesPreventing Crime What Works, What Doesn't, What's Promisingaorsós100% (1)

- Annotated Guide To The Amicus Briefs in The Citizenship Question Cases (NY)Document3 pagesAnnotated Guide To The Amicus Briefs in The Citizenship Question Cases (NY)The Brennan Center for JusticeNo ratings yet

- Comments To The U.S. Civil Rights Commission On Economic Impact of Criminal RecordsDocument12 pagesComments To The U.S. Civil Rights Commission On Economic Impact of Criminal RecordsThe Brennan Center for JusticeNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Crime RatesDocument11 pagesResearch Paper On Crime Ratesepfdnzznd100% (1)

- Research Paper Crime RatesDocument12 pagesResearch Paper Crime Ratesj1zijefifin3100% (1)

- Research Paper On Crime StatisticsDocument11 pagesResearch Paper On Crime Statisticsm0d1p1fuwub2100% (1)

- To Serve and Collect - Measuring Police CorruptionDocument59 pagesTo Serve and Collect - Measuring Police Corruptionray_phenicieNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Crime RateDocument11 pagesLiterature Review On Crime Ratec5rr5sqw100% (1)

- Following The Money of Mass Incarceration - Prison Policy InitiaDocument22 pagesFollowing The Money of Mass Incarceration - Prison Policy InitiaDeezyNo ratings yet

- Osc Second Interim ReportDocument136 pagesOsc Second Interim ReportJamie WhiteNo ratings yet

- Criminal Justice: Reforms To Improve Lives and Save MoneyDocument31 pagesCriminal Justice: Reforms To Improve Lives and Save MoneySteve Marroni100% (1)

- IRS LetterDocument5 pagesIRS LetterJames LynchNo ratings yet

- Avis, Ferraz e Finan (2018) - Do Government Audit Reduce CorruptionDocument53 pagesAvis, Ferraz e Finan (2018) - Do Government Audit Reduce Corruptionsergio krakowiakNo ratings yet

- PBO Crime Cost CanadaDocument36 pagesPBO Crime Cost CanadaThe Criminalization and Punishment Education Project (CPEP)No ratings yet

- Uniform Commerical Code Fraudulent FilingsDocument32 pagesUniform Commerical Code Fraudulent Filingsreaction_s100% (1)

- Have US-Funded CARSI Programs Reduced Crime and Violence in Central America? An Examination of LAPOP'S Impact Assessment of US Violence Prevention Programs in Central AmericaDocument22 pagesHave US-Funded CARSI Programs Reduced Crime and Violence in Central America? An Examination of LAPOP'S Impact Assessment of US Violence Prevention Programs in Central AmericaCenter for Economic and Policy ResearchNo ratings yet

- 19-21-002-03-315 UI COVID-19 Alert Memo - 022221Document7 pages19-21-002-03-315 UI COVID-19 Alert Memo - 022221ABC Action News100% (1)

- Senate Hearing, 109TH Congress - Bolstering The Safety Net: Eliminating Medicaid FraudDocument109 pagesSenate Hearing, 109TH Congress - Bolstering The Safety Net: Eliminating Medicaid FraudScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Uniform Crime Report Research PaperDocument4 pagesUniform Crime Report Research Papergw1w9reg100% (1)

- Groups' Letter To CongressDocument5 pagesGroups' Letter To CongressJohn BinderNo ratings yet

- Reforming America's Criminal Justice System: Refocusing On Delivering Results, Aligning With Our Values, and Reducing The Burden On TaxpayersDocument16 pagesReforming America's Criminal Justice System: Refocusing On Delivering Results, Aligning With Our Values, and Reducing The Burden On Taxpayerscorybooker100% (1)

- Global AntiCorruption Laws DentonsDocument2 pagesGlobal AntiCorruption Laws DentonsFelipe XavierNo ratings yet

- Brennan Center Weighs in On Fiscal Cliff TalksDocument4 pagesBrennan Center Weighs in On Fiscal Cliff TalksThe Brennan Center for JusticeNo ratings yet

- 12-09-26 J Zernik, Large-Scale Fraud in US Court Records Is Linked To Failing Banking Regulation - OpEdNewsDocument3 pages12-09-26 J Zernik, Large-Scale Fraud in US Court Records Is Linked To Failing Banking Regulation - OpEdNewsHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)No ratings yet

- Criminalrecords 1Document43 pagesCriminalrecords 1Nelson Danny JuniorNo ratings yet

- The Juvenile Justice System in Washington State: Recommendations To Improve Cost-EffectivenessDocument8 pagesThe Juvenile Justice System in Washington State: Recommendations To Improve Cost-EffectivenessWashington State Institute for Public PolicyNo ratings yet

- Artigo RedesDocument17 pagesArtigo RedeswilsoncloverNo ratings yet

- Reducing Recidivism Lessons From The States - Reducing Recidivism and Curbing Corrections Costs Through Justice ReinvestmentDocument9 pagesReducing Recidivism Lessons From The States - Reducing Recidivism and Curbing Corrections Costs Through Justice ReinvestmentswmelNo ratings yet

- Cfetf 2024 Report FinalDocument33 pagesCfetf 2024 Report FinalVeronica SilveriNo ratings yet

- SB2061 Harms and Costs - MIRA SummaryDocument7 pagesSB2061 Harms and Costs - MIRA SummaryVotoBostonNo ratings yet

- CybercrimeDocument6 pagesCybercrimeapi-569081456No ratings yet

- Audit - California Fails To Track Its Homelessness Spending, Outcomes - CalMattersDocument7 pagesAudit - California Fails To Track Its Homelessness Spending, Outcomes - CalMattersSteveNo ratings yet

- Week 2Document3 pagesWeek 2r66kbsksy2No ratings yet

- Assignment 10 PageDocument12 pagesAssignment 10 PageDennis waitiki muiruriNo ratings yet

- U.S. House Report On New York's Medicaid SystemDocument35 pagesU.S. House Report On New York's Medicaid SystemCasey SeilerNo ratings yet

- D.D.C. 21-cv-00430 DCKT 000001 000 Filed 2021-02-18-1Document11 pagesD.D.C. 21-cv-00430 DCKT 000001 000 Filed 2021-02-18-1Spit FireNo ratings yet

- Biometrics PrimerDocument13 pagesBiometrics PrimerJeya Prakash JPNo ratings yet

- ACPO Final Nature Extent and Economic Impact of FraudDocument119 pagesACPO Final Nature Extent and Economic Impact of FraudrajsalgyanNo ratings yet

- 2023 01 13 Ny Ui Fraud Letter To Ny Dol - FinalDocument3 pages2023 01 13 Ny Ui Fraud Letter To Ny Dol - FinalAdam PenaleNo ratings yet

- Report From The Crime Prevention Research Center: Concealed Carry Permit Holders Across The United States: 2021Document75 pagesReport From The Crime Prevention Research Center: Concealed Carry Permit Holders Across The United States: 2021SteveGNo ratings yet

- Mandatory Minimums and Racial DisparityDocument14 pagesMandatory Minimums and Racial DisparityFayaadh Salehin AhmedNo ratings yet

- An Eye For An Eye in The Electronic Age - GaugingDocument19 pagesAn Eye For An Eye in The Electronic Age - GaugingxipixipiNo ratings yet

- Background CheckDocument46 pagesBackground CheckPike Fer100% (2)

- Peninsula-Lai-Lai-Neg-6 - Westminster-Round3Document38 pagesPeninsula-Lai-Lai-Neg-6 - Westminster-Round3IanNo ratings yet

- DOJ False Terrorism Report ComplaintDocument34 pagesDOJ False Terrorism Report ComplaintProtect DemocracyNo ratings yet

- U.S. Labor Department Awards $140 in GrantsDocument19 pagesU.S. Labor Department Awards $140 in GrantsAdam ForgieNo ratings yet

- RE: House Bill 564: Attachment A)Document6 pagesRE: House Bill 564: Attachment A)Marc LevinNo ratings yet

- U.S. Sentencing Commission Adopts Economic Crime AmendmentsDocument2 pagesU.S. Sentencing Commission Adopts Economic Crime Amendments92589258No ratings yet

- Tax Policy and the Economy: Volume 32From EverandTax Policy and the Economy: Volume 32Robert A. MoffittNo ratings yet

- Tax Policy and the Economy, Volume 37From EverandTax Policy and the Economy, Volume 37Robert A. MoffittNo ratings yet

- Summary of Recoding America by Jennifer Pahlka: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do BetterFrom EverandSummary of Recoding America by Jennifer Pahlka: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do BetterNo ratings yet

- Capitol Gains: Exposing and Reforming Government Financial Crimes.From EverandCapitol Gains: Exposing and Reforming Government Financial Crimes.No ratings yet

- Out of Bounds and Out of Control: Regulatory Enforcement at the EPAFrom EverandOut of Bounds and Out of Control: Regulatory Enforcement at the EPANo ratings yet

- Zoning Changes Lawsuit RoanokeDocument26 pagesZoning Changes Lawsuit RoanokeWSLSNo ratings yet

- 2021-22 ROCI Threat ReportDocument62 pages2021-22 ROCI Threat ReportWSLSNo ratings yet

- 2022-23 ROCI Threat ReportDocument58 pages2022-23 ROCI Threat ReportWSLSNo ratings yet

- 2019-20 ROCI Threat ReportDocument16 pages2019-20 ROCI Threat ReportWSLSNo ratings yet

- Natural Bridge ZooDocument2 pagesNatural Bridge ZooWSLSNo ratings yet

- Report Use of Tony Brown Nov 10 2023Document3 pagesReport Use of Tony Brown Nov 10 2023Pat ThomasNo ratings yet

- 2018-19 ROCI Threat ReportDocument18 pages2018-19 ROCI Threat ReportWSLSNo ratings yet

- 95 Animals SeizedDocument5 pages95 Animals SeizedWSLSNo ratings yet

- Officer Involved Shooting (June 30, 2023) Press ReleaseDocument8 pagesOfficer Involved Shooting (June 30, 2023) Press ReleasePat ThomasNo ratings yet

- Press Release - December 8, 2023Document2 pagesPress Release - December 8, 2023Justin GearyNo ratings yet

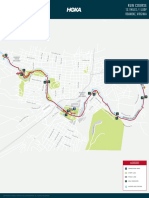

- IM23 703VBR CourseMap Swim 020623 CCDocument1 pageIM23 703VBR CourseMap Swim 020623 CCWSLSNo ratings yet

- ConclusionDocument1 pageConclusionWSLSNo ratings yet

- Roci Gun Violence Stats 1.1.23-10.15.23Document1 pageRoci Gun Violence Stats 1.1.23-10.15.23WSLSNo ratings yet

- AG Letter - 10-15-2023Document1 pageAG Letter - 10-15-2023WSLSNo ratings yet

- Lynchburg Vice Mayor CensuredDocument2 pagesLynchburg Vice Mayor CensuredEzra HercykNo ratings yet

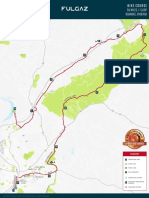

- IM22 703VirginiasBlueRidge CourseMap Run 040722 CCDocument2 pagesIM22 703VirginiasBlueRidge CourseMap Run 040722 CCWSLSNo ratings yet

- Criminal ComplaintDocument1 pageCriminal ComplaintWSLSNo ratings yet

- IM23 703VirginiasBlueRidge CourseMap Bike 033023 CC 2Document2 pagesIM23 703VirginiasBlueRidge CourseMap Bike 033023 CC 2WSLSNo ratings yet