Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Perancangan Pelatihan

Perancangan Pelatihan

Uploaded by

Muhammad Aji PangestuOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Perancangan Pelatihan

Perancangan Pelatihan

Uploaded by

Muhammad Aji PangestuCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/227629113

The effects of training design, individual characteristics and work

environment on transfer of training. International Journal of Training and

Development, 11(4), 282-294

Article in International Journal of Training and Development · December 2007

DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2419.2007.00286.x

CITATIONS READS

209 11,755

5 authors, including:

Raquel Velada António Caetano

ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

7 PUBLICATIONS 542 CITATIONS 172 PUBLICATIONS 2,003 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

John W. Michel Brian D. Lyons

Loyola University Maryland Elon University

33 PUBLICATIONS 1,138 CITATIONS 28 PUBLICATIONS 828 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

ELITE: Emergence of high-impact entrepreneurs View project

Leader Behavior View project

All content following this page was uploaded by John W. Michel on 15 April 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

International Journal of Training and Development 11:4

ISSN 1360-3736

The effects of training

design, individual

characteristics and work

environment on transfer

of training

Raquel Velada, António Caetano,

John W. Michel, Brian D. Lyons

and Michael J. Kavanagh

This study aims to gain insight into some of the factors that

determine the transfer of training to the work context. The

present research examined the relationship between three types

of predictors on transfer of training, including training design,

individual characteristics and work environment. Data was

collected at two points in time from 182 employees in a large

grocery organization. The results indicated that transfer

design, performance self-efficacy, training retention and perfor-

mance feedback were significantly related to transfer of train-

ing. Contrary to expectation, supervisory support was not

significantly related to transfer of training. These results

suggest that in order to enhance transfer of training, organiza-

tions should design training that gives trainees the ability to

❒ Raquel Velada, PhD student, ISCTE – Institute of Social Sciences and Business Studies, Department of

Social and Organizational Psychology, Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1649-026 Lisbon, Portugal. Email:

raquel.velada@netcabo.pt. António Caetano, Associate Professor, ISCTE – Institute of Social Sciences and

Business Studies, Lisbon, Portugal. Email: antonio.caetano@iscte.pt. John W. Michel, Assistant Professor,

Department of Management, College of Business and Economics, Towson University, 8000 York Road,

Towson, MD 21252, USA. Email: jmichel@towson.edu. Brian D. Lyons, Assistant Professor, Department

of Management, Craig School of Business, California State University, Fresno, 5241 N. Maple Ave.,

Fresno, CA 93740, USA. Email: blyons@csufresno.edu. Michael J. Kavanagh, Professor Emeritus,

Department of Management, School of Business, University at Albany, 1400 Washington Ave., Albany,

NY 12222, USA. Email: mickkav@nycap.rr.com

This study was supported by a grant to the first author from the Foundation for Science and Technology

of Portugal (SFRH/BD/10558/2002).

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2QD,

UK and 350 Main St., Malden, MA 02148, USA.

282 International Journal of Training and Development

transfer learning, reinforces the trainee’s beliefs in their ability

to transfer, ensures the training content is retained over time

and provides appropriate feedback regarding employee job per-

formance following training activities.

Introduction

Organizations spend an immense amount of time and money on training in order to

facilitate employees’ learning of job-related competencies (Cascio, 2000; Noe et al.,

2006). According to Training Magazine’s ongoing industry report, US companies spend

more than $50 billion annually on formal training (Dolezalek, 2004). Moreover, invest-

ment in training activities has increased all over the world in recent years. As a result

of the financial investments organizations make in training, it is important to provide

evidence that training efforts are being fully realized (Cascio, 2000; Dowling & Welch,

2005). In other words, it is important for organizations to ensure that training leads to

desired work outcomes such as increases in job performance.

Research has demonstrated that training efforts are unlikely to result in positive

changes in job performance unless the newly trained competencies are transferred

to the work environment (see Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Montesino, 2002; Rouiller &

Goldstein, 1993). As a result, there has been an increased effort to understand the

antecedents and consequences of the transfer of training process.

Baldwin and Ford (1988) define transfer of training as ‘the degree to which trainees

effectively apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes gained in the training context to

the job’ (p. 63). This suggests that transfer of training first requires a trainee to learn

new job-related competencies (Velada & Caetano, 2007). By learning, we are referring

to a relatively permanent change in knowledge, skills and behaviors of trainees (Weiss,

1990). After learning and retaining the training content, trainees should transfer the

knowledge and/or skills accrued to the work context with the intention of improving

job performance over time (Noe et al., 2006).

However, it has been estimated that only about 10 per cent of all training experi-

ences are transferred from the training environment to the job (Baldwin & Ford, 1988).

Although this is a lower-bound estimate, Wexley and Latham (2002) suggest that

although approximately 40 per cent of content is transferred immediately following

training, the amount transferred falls to 25 per cent after 6 months and 15 per cent

after 1 year. This suggests that as time passes, trainees may be unable or less moti-

vated to retain and use the information gained in the training program. Furthermore,

this indicates that much of the time and money invested in training is never fully

realized, because only a small percentage of the training effectively results in perma-

nent transferability to the workplace. As a result, understanding and improving the

transfer of training process has become a primary concern for training researchers

and practitioners.

Although several studies have been conducted to understand the transfer of training

process, conceptual models for understanding this process are limited. Kavanagh (1998)

developed a multi-level multistage process to help understand the complexities of the

transfer of training process. Specifically, he suggested that training transfer is influ-

enced by several variables at different levels of analysis (e.g. individual, supervisor,

workgroup and organization) and in different stages in the training process (e.g.

pre-training, training and post-training). To date, the extant literature (e.g. Baldwin &

Ford, 1988; Holton, 1996, 2005; Tracey et al., 1995) has identified three main determi-

nants of training transfer: training design or enabling factors, individual factors or trainee

characteristics, and work environment or transfer climate.

Holton et al. (2000) developed the Learning Transfer System Inventory (LTSI) to

evaluate the specific factors on those dimensions affecting the transfer of training

process. Based on the Human Resource Development Research and Evaluation Model

(Holton, 1996), the LTSI includes 16 factors that either facilitate or inhibit training

transfer. It has been argued that the LTSI is the only research-based instrument for

Transfer of training 283

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

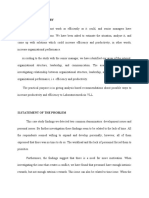

TRAINING DESIGN

Transfer design

INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS

Self-efficacy

Transfer of

Training retention training

WORK ENVIRONMENT

Feedback

Supervisor support

Figure 1: Simplified model of transfer of training.

assessing a comprehensive set of factors affecting transfer of learning (Chen et al.,

2005; Holton et al., 2000). Whereas studies have been conducted to validate the LTSI

measure (Chen et al., 2005; Holton et al., 2000; Khasawneh et al., 2006), little has been

done to empirically demonstrate the relationship between LTSI measures and transfer

of training. Additionally, the LTSI appears to exclude important individual difference

variables such as cognitive ability, locus of control and training retention (e.g. Baldwin

& Ford, 1988), and environmental factors such as continuous learning culture (e.g.

Tracey et al., 1995).

Based on a review of the transfer of training literature, Kavanagh (1998) concluded

that there are significant gaps in the empirical literature for training design, individual

variables and organizational environment factors. This suggests the need for studies to

investigate the impact of these issues on the transfer of training process. Thus, consid-

ering the three main influences on transfer of training previously identified by Holton

(1996, 2005), this study aims to contribute to the theory of training transfer by empiri-

cally analysing how different sets of variables simultaneously influence the transfer of

training.

As depicted in Figure 1, we hypothesize that several variables related to training

design, individual characteristics and work environment affect transfer of training. The

following section provides a brief overview of the literature regarding the influence of

training design, individual characteristics and work environment on transfer of train-

ing, giving special attention and theoretical justification to the relationships that will be

tested in this study.

Influences of training design on transfer of training

According to the training literature, there are several training design factors that

influence transfer of training: instructional techniques and learning principles (e.g.

Alvarez et al., 2004); self-management and relapse prevention strategies (e.g. Tziner

et al., 1991; Wexley & Nemeroff, 1975) and goal setting (e.g. Gist et al., 1990). Thus,

organizations should design their training programs to include such factors that

increase the likelihood of transfer. Accordingly, the LTSI measures such a factor, trans-

fer design. Transfer design refers to the degree to which training has been designed and

delivered in such a way that provides trainees the ability to transfer learning back to the

job (Holton et al., 2000). Holton et al. (2000) argue that part of transfer design is the

degree to which training instructions match job requirements. Trainees are more likely

to transfer the training content to the work context when they perceive that the training

program was designed and delivered in such a way that maximizes the trainee’s ability

284 International Journal of Training and Development

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

to transfer the training to the job (Holton, 1996; 2005). Consequently, when trainees

have previous knowledge and practice on how to apply the newly learned knowledge

and skills to the job and when training instructions are congruent with job require-

ments, an increased likelihood of transfer should exist. Based on these assertions, we

hypothesized the following:

H1 Trainees’ perceptions of transfer design will be positively related to transfer of

training.

Influences of individual characteristics on transfer of training

In addition to training design, there are several individual characteristics that affect the

transfer of training process. Some of these characteristics include cognitive ability,

locus of control, conscientiousness, achievement motivation, motivation to learn and to

transfer, anxiety, self-efficacy, and valence (e.g. Colquitt et al., 2000; Mathieu et al., 1992;

Noe, 1986). Others include job involvement, organizational commitment, organiza-

tional cynicism and job satisfaction (e.g. Mathieu et al., 1993; Tannenbaum et al., 1991;

Tesluk et al., 1995; Velada & Caetano, 2007).

Of these characteristics, performance self-efficacy has been found to strongly relate to

both learning (Gist et al., 1991; Mathieu et al., 1992; Quinones, 1995) and transfer of

training (e.g. Ford et al., 1998). Additionally, some studies (e.g. Ford et al., 1998) have

indicated that trainees with higher self-efficacy are more likely to transfer the training to

the job. Holton et al. (2000) defined performance self-efficacy as an individual’s general

belief that they are able to change their performance when desired. Hence, when a

trainee feels confident in his or her ability to perform, the more likely he or she will

transfer such knowledge and/or skill to the job. Thus, we hypothesized the following:

H2 Performance self-efficacy will be positively related to training transfer.

As suggested before, trainees must have the ability to retain the knowledge instilled

during the training program to facilitate the transfer process. Similar to cognitive

ability, training retention is the degree to which trainees retain the content after train-

ing is completed. Baldwin and Ford (1988) argue that learning retention outcomes are

directly associated with the generalization and maintenance of training effects on the

job. They argue that in order for trained skills to be transferred, they first must be

learned and retained. Although we were unable to find any previous research empiri-

cally demonstrating this relationship, we believe it is an important aspect in the transfer

of training process. Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

H3 Training retention will be positively related to training transfer.

Influences of work environment on transfer of training

Work environment variables have been investigated less often than training design and

individual characteristics (Alvarez et al., 2004; Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Holton et al., 1997;

Tannenbaum & Yukl, 1992). However, a number of studies have shown that environ-

mental factors are important for understanding the transfer of training process (e.g.

Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Lance et al., 2002; Rouiller & Goldstein, 1993; Tracey et al., 1995).

Two dimensions of the work environment that have received attention with regard

to transfer of training include organizational culture and climate (e.g. Baldwin & Ford,

1988; Rouiller & Goldstein, 1993; Tracey et al., 1995) Tracey et al. (1995) stressed the

importance of both transfer of training climate and continuous learning culture as work

environment variables that have a significant impact on the post-training behaviors.

Some indicators of transfer climate include performance feedback, peer support, super-

visor support and supervisor sanctions (e.g. Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Holton et al., 2000;

Tracey & Tews, 2005; Tracey et al., 1995).

Research has indicated that when employees perceive that the organizational climate

is supportive, they are more likely to apply their new knowledge in the work environ-

Transfer of training 285

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

ment (see Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Tracey et al., 1995). Performance feedback includes an

indication from management about how well one is performing his or her job (Holton

et al., 2000). Specifically, feedback regarding the newly learned knowledge and skills

and how these relate to job performance increases the likelihood of its transfer to the

work context (Reber & Wallin, 1984). Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

H4 Feedback regarding the trainee’s performance after training will be positively

related to training transfer.

Supervisor support can be described as the extent to which supervisors support and

reinforce the use of newly learned knowledge and skills on the job (Holton et al., 2000).

Although there is some contradictory evidence (e.g. Russell et al., 1985), the dominant

literature suggests that when trainees perceive that their supervisors support the appli-

cation of newly developed knowledge and skills, they are more likely to transfer these

competencies back to the job (e.g. Bates et al., 2000; Brinkerhoff & Montesino, 1995;

Colquitt et al., 2000; Noe, 1986; Tracey & Tews, 2005). Thus, we hypothesized the

following:

H5 Supervisor support for training transfer will be positively related to training

transfer.

Method

Procedure

The initial sample consisted of 336 employees from nine stores of a grocery market

company in Portugal. All training occurred in a classroom within each store, although

the training content differed to reflect each store’s job composition. In a period of 1

month, participants attended one of the following training programs: customer service,

environmental issues, security, prevention and hygiene in the workplace. In order to

address all the training objectives and to facilitate the knowledge acquisition as well as

behavior change, different training methods were used including lecture, discussion,

simulations (e.g. role play) and audiovisual techniques (e.g. video tapes).

At the end of the training program, 336 trainees completed a self-report survey to

assess perceptions of transfer design, performance self-efficacy and supervisor support

(Time 1 data collection). Three months after the training sessions, surveys were sent to

the trainees to complete and return (Time 2 data collection). These surveys measured

the trainees’ perceptions of training retention, feedback and training transfer. Of the

336 surveys distributed, 219 were returned. This loss of 117 respondents over the

3-month period was due in part to the high rate of personnel turnover in these jobs. In

addition, due to incomplete survey completion and incorrect coding, 37 more surveys

had to be discarded, leaving a final sample of 182 matched pairs.

Participants

Of the 182 study participants, 62 per cent were female. The mean age for the partici-

pants was 30, with a range of 19–58. The average tenure of the participants in the

company was 4.5 years with 46.6 per cent having been employed in the company for

less than 1 year. In terms of education, 52.3 per cent had a high school degree while

only 5.2 per cent had a college degree. Furthermore, 79 per cent of the participants were

in non-supervisory roles.

Measures

The independent variables of transfer design, performance self-efficacy, supervisor

support and performance feedback were measured with items from the LTSI (Holton

et al., 2000). The measure of training retention was created specifically for this study.

286 International Journal of Training and Development

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

The measure of the dependent variable, training transfer, was based on Tesluk et al.’s

(1995) research. All variables were measured using a 5-point Likert scale.

Transfer design

Transfer design is defined as the ‘degree to which (1) training has been designed and

delivered to give trainees the ability to transfer learning to the job, and (2) training

instructions match job requirements’ (Holton et al., 2000, p. 345). Transfer design was

measured with four items with an alpha of 0.78. A sample item is ‘The way the

trainer(s) taught the material made me feel more comfortable I could apply it’.

Performance self-efficacy

Performance self-efficacy was defined as ‘an individual’s general belief that they are

able to change their performance when they want to’ (Holton et al., 2000, p. 346).

Performance self-efficacy was measured with four items with an alpha of 0.76. A

sample item is ‘I am confident in my ability to use new skills at work’.

Supervisor support

Supervisor support was defined as the ‘extent to which supervisors/managers support

and reinforce use of training on the job’ (Holton et al., 2000, p. 345). The measure of

supervisor support consisted of six items with an alpha of 0.89. A sample item is ‘My

supervisor meets with me to discuss ways to apply training on the job’.

Performance feedback

Performance feedback was defined as ‘formal and informal indicators from an organi-

zation about an individual’s job performance’ (Holton et al., 2000, p. 346). The measure

of performance feedback consisted of three items with an alpha of 0.72. A sample item

is‘After training, I received feedback from people on how well I am applying what I

learned’.

Training retention

Because a measure of training retention could not be found in the literature, three items

were created for this study (a = 0.70). The three items included ‘I still remember the

main topics that I have learned in the training course,’ ‘I can easily say several things

that I have learned in the training course’ and ‘I had never thought again about the

training content (reverse coded)’.

Training transfer

Tesluk et al. (1995) developed a three-item scale to measure the extent to which indi-

viduals transfer the knowledge and skills presented in training sessions to their core

jobs (a = 0.87). A sample item is ‘I have been using the skills presented in the training

course to help improve my performance’.

Results

Factor analysis

In order to assess the extent to which each of the variables represents a separate

construct, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed. An EFA is warranted

because some of the items were adapted from previous research to correspond to the

purposes of this study and, as a result, the dimensionality of the survey was not assured

for this sample. A principal component analysis (PCA) followed by varimax rotation

was performed on the 23 survey items. Two decision rules were imposed to ascertain

the number of components and items comprised in the factor analytic model: (1)

eigenvalues over 1.0 were retained and (2) components that discretely loaded from

other factors in the screen plot were retained. As depicted in Table 1, six components

were deduced from the 23 items and these components accounted for 55.43 per cent of

the variance in the items.

Transfer of training 287

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Table 1: Item means, standard deviations and varimax rotated factor loadings

Item Factor loadings

M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

Supervisor support

Ways to apply training on 3.47 0.83 0.85 0.09 0.14 0.13 0.09 -0.01

the job

Problems in using 3.56 0.84 0.79 0.12 0.04 0.16 0.08 0.07

training

Interest in the training 3.71 0.82 0.72 0.21 0.06 0.07 0.05 0.05

learning

Feedback on performance 3.73 0.82 0.65 0.20 0.15 -0.04 0.31 0.01

after training

Performance goals based 3.63 0.82 0.63 0.14 0.26 -0.03 0.36 0.03

on training

Goals to apply training on 3.77 0.85 0.56 0.22 0.14 0.08 0.21 0.02

the job

Transfer design

Examples about ways to 4.13 0.59 0.19 0.77 0.19 0.06 0.07 -0.02

use learning on the job

Activities and exercises on 3.98 0.67 0.10 0.63 0.17 0.19 -0.06 -0.03

how to apply learning

Teaching on how to apply 3.84 0.70 0.18 0.61 0.10 0.07 0.04 0.07

learning on the job

Understanding of the 3.98 0.69 0.23 0.54 0.18 0.02 0.17 0.01

training designers on

how to use learning

Performance self-efficacy

Ability to use newly 3.99 0.64 0.08 0.16 0.80 0.08 0.05 0.05

learned skills on the job

Confidence in the ability 4.00 0.61 0.10 0.22 0.71 0.11 0.01 0.07

to use new skills at

work

Using learning even in 3.98 0.61 0.30 0.17 0.51 0.14 0.04 -0.02

difficult situations

Overcoming obstacles to 3.95 0.64 0.17 0.16 0.40 0.21 0.26 -0.01

use new skills or

knowledge

Training transfer

Using new skills to 3.76 0.71 0.01 0.07 0.14 0.75 0.24 0.25

improve performance

Training helped to 3.77 0.69 0.13 0.19 0.15 0.73 0.30 0.16

improve job performance

Incorporating learned 3.77 0.75 0.08 0.17 0.21 0.65 0.31 0.20

skills into daily work

activities

Performance feedback

Post-training conversations 3.38 0.77 0.28 0.08 0.12 0.17 0.72 0.02

with people about how

to improve job

performance

Feedback on how well was 3.20 0.82 0.14 -0.04 0.01 0.21 0.59 0.05

the training application

288 International Journal of Training and Development

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Table 1: Continued

Item Factor loadings

M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

People said things that 3.50 0.81 0.17 0.10 0.03 0.26 0.47 -0.08

helped to improve job

performance

Training retention

Remember the main topics 3.90 0.65 0.00 0.06 -0.07 0.08 0.08 0.99

learned in the training

Easily say several things 3.82 0.70 0.02 -0.01 0.09 0.10 0.05 0.67

learned in the training

Never thought again 3.98 0.87 0.05 -0.01 0.04 0.21 -0.12 0.37

about the training

contenta

Note: Higher item loadings on each factor are underlined. A 5-point Likert response scale was

used for all items.

a

item was reversed coded.

n = 182.

Overall, the results of the PCA were consistent with the extant literature. The

first principal component (six items) was labeled ‘supervisor support’ (a = 0.89); the

second principal component (four items) was labeled ‘transfer design’ (a = 0.78);

the third principal component (four items) was labeled ‘performance self-efficacy’

(a = 0.76); the fourth principal component (three items) was labeled ‘training transfer’

(a = 0.87); the fifth principal component (three items) was labeled ‘performance feed-

back’ (a = 0.72); and finally, the last principal component (three items) was labeled

‘training retention’ (a = 0.70). Based on the results from the EFA, we used these 5-factor

scores to test the aforementioned hypotheses.

Hypothesis testing

Means, standard deviations, intercorrelations and reliabilities of the variables are pre-

sented in Table 2. In general, results indicated that all independent variables of our

study were positively and significantly related to training transfer. To determine the

extent to which transfer design, performance self-efficacy, training retention, feedback

and supervisor support affect transfer outcome, hierarchical regression analysis was

performed (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). The independent variables entry was based on the

logic of our hypothesized model. Additionally, demographic variables and the nature

of the training were initially included in the analysis but were subsequently discarded

because they did not significantly predict transfer of training. The results of the hier-

archical regression analysis are presented in Table 3.

The results of step 1 showed that transfer design significantly predicted transfer of

training (b = 0.31, p < 0.01), supporting our first hypothesis. In step 2, we entered the

individual factors. Similarly to transfer design, both performance self-efficacy (b = 0.30,

p < 0.01) and training retention (b = 0.30, p < 0.01) significantly predicted transfer of

training, supporting our second and third hypotheses, respectively. Finally, in step 3 we

entered the environmental variables. As shown in Table 3, only feedback significantly

predicted transfer of training (b = 0.42, p < 0.01), providing support for our fourth

hypothesis. Although the bivariate correlation between supervisor support and train-

ing transfer was positive and significant (r = 0.31, p < 0.001), the hierarchical regression

did not support this hypothesis (b = -0.05, p = ns) Therefore, the fifth hypothesis was

only partially supported. Overall, these variables explained 42 per cent of the total

variance in transfer of training.

Transfer of training 289

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Table 2: Scale item means, standard deviations, intercorrelations and reliabilities

Variables M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

(1) Transfer design 3.96 0.51 (0.78)

(2) Performance self- 3.98 0.47 0.43** (0.76)

efficacy

(3) Training retention 3.90 0.58 0.05 0.08 (0.70)

(4) Performance 3.36 0.64 0.19* 0.25** 0.06 (0.72)

feedback

(5) Supervisor 3.65 0.66 0.42** 0.41** 0.08 0.43** (0.89)

support

(6) Training transfer 3.77 0.63 0.31** 0.40** 0.33** 0.50** 0.31** (0.87)

Note: A 5-point Likert scale was used for all variables.

* p < 0.01.

** p < 0.001.

Table 3: Hierarchical regression analysis results

Independent variables Dependent variables

Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

b b b

Transfer design 0.31** 0.17* 0.14*

Performance self-efficacy – 0.30** 0.23**

Training retention – 0.30** 0.29**

Performance feedback – – 0.42**

Supervisor support – – -0.05

R2 0.10 0.27 0.42

Adj. R2 0.09 0.26 0.41

Note: Dependent variable: training transfer.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

Discussion

The results of this research demonstrate the importance of training design, individual

characteristics and the influence of the work environment on transfer of training.

The results for H1 indicated that transfer design, which assessed how applicable the

training was to the job, positively influenced transfer of training. These results reinforce

the notion that organizations should be aware of how well the content of the training

program, in terms of the use of activities, examples and exercises, is focused on the

application of on-the-job learning.

The second and third hypotheses involving performance self-efficacy and the reten-

tion of the training content were also significantly related to transfer of training. Such

results suggest that when trainees believe in their capabilities to transfer learning and

when they retain training content, they are more likely to perceive that they have

transferred the training to the work context.

The impact of the work environment in terms of feedback on transfer of training, as

predicted in hypothesis 4, was also supported in this research, indicating that the

feedback from others in the organization regarding the trainee’s performance after

training influences perceptions of training transfer. Contrary to what was predicted,

however, hypothesis 5 was not supported. In this instance, supervisor support did not

significantly predict transfer of training.

290 International Journal of Training and Development

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

One strength of this research was that it allowed us to compare the results of transfer

of training research using two different methodologies. One methodology assumes

that in order to evaluate transfer of training, one must have evaluations of changes in job

performance as measured by persons (sources) other than the trainees (Lance et al.,

2002; Tracey et al., 1995). These other persons could include supervisors, co-workers

and customers. However, it is usually difficult to gain access to and collect data from

persons other than the trainees. The other methodology used in this study is to collect

all data on the research variables from the trainees. Despite the fact that some argue

against the use of self-report ratings of job performance, it is likely that the trainees are

the most important and valid source of the measurement of job performance as their

perceptions will drive their motivation and performance. Whereas using data collected

from other sources (i.e. supervisors, peers and customers) may provide slightly differ-

ent ratings, data collected using only a trainee self-report method can provide similar

results as demonstrated in the present research. Furthermore, because it is so important

to measure transfer of training in order to assess the practical and financial aspects of

training effectiveness (Cascio, 2000), using this latter paradigm may be simpler and less

expensive for human resource and managerial professionals. The important point is

that it may influence more organizations to evaluate transfer of training with empirical

data rather than assuming that transfer always occurs.

Theoretical and practical implications

Results from this study have potentially important implications for future research and

practice. In general, the results of this research argue for examining all aspects of the

training process when conducting research on transfer of training. Hence, these results

provide empirical evidence to the aforementioned theoretical models (e.g. Baldwin &

Ford, 1988; Holton, 1996, 2005; Kavanagh, 1998) suggesting that transfer of training is

impacted by the training design, characteristics of the trainee and contextual factors

such as feedback regarding post-training job performance. Future research should

examine pre-training factors in a similar study in order to determine if the combined

factors provide better prediction of transfer of training. As indicated earlier, without

the effective transfer of training from the training context to the organizational envi-

ronment, the costs and time spent in training is simply wasted.

More specifically, this study supports the theoretical literature (e.g. Holton, 1996,

2005) that suggest the importance of a transfer design that maximizes the trainee’s

ability to transfer in enhancing training transfer. The present study also extends

Baldwin and Ford’s (1988) work by demonstrating empirically that for training to be

transferred, the training content should be retained over time. Finally, the results of this

study reinforce the role of performance self-efficacy (Ford et al., 1998) and performance

feedback (Reber & Wallin, 1984) on the explanation of training transfer.

However, results of this study do not support the dominant literature (e.g. Bates

et al., 2000; Brinkerhoff & Montesino, 1995) that indicate that supervisory support is a

critical variable in transfer of training. The results regarding the hypothesis in which it

was predicted that supervisor support would affect transfer of training could seem

puzzling at first because the previous literature has typically supported this relation-

ship (Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Lance et al., 2002; Rouiller & Goldstein, 1993; Tracey et al.,

1995). However, some gaps persist in the literature regarding the specific supervisory

factors that influence transfer. Like in the prevalent literature, this study considered

only the post-training supervisory dimensions like meetings and feedback. Perhaps

supervisory interventions in pre-training and during the training could have the stron-

ger impact on transfer of training. Clearly, this is an avenue for future research.

An interesting aspect of the findings of this study is a comparison with previous

research using a different methodology (Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Lance et al., 2002;

Rouiller & Goldstein, 1993; Tracey et al., 1995), as well as using participants from a

country other than the United States. Most of the cited transfer of training research has

used pre-post designs using a sample from the United States, whereas this study used

a post-test design with a sample from Portugal. Thus, the different results generated

Transfer of training 291

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

with the supervisor support variable could also be attributed to these methodological

and cultural differences. More important, however, are the similarities in findings

between this study and those done in the United States.

Regarding psychometric implications, the results from this study provided some

criterion validation evidence for the LTSI measure. As noted in the hypotheses testing,

the results of this study found strong relationships between some LTSI dimensions and

transfer of training.

Based on the results of this study, we can argue that for organizations to maximize

their return on investment with regards to training and development, they need to

focus on all three determinants of transfer of training: training design, individual

characteristics and work environment. First, organizations need to ensure that training

is designed such that it matches the ability level of trainees. This will help ensure that

trainees have the ability to (1) learn the training material and (2) utilize the knowledge

and skills accrued during training outside of the learning environment. Second, orga-

nizations can improve transfer of training by ensuring that trainees believe that they

have the capabilities to successfully learn the new material and utilize their new

knowledge, skills and abilities (KSAs) on the job. This can be improved by (1) showing

trainees that other employees who have received the training have successfully

improved their job performance, (2) providing trainees the opportunity to experience

mastery of the training material in the training environment and (3) modeling the

appropriate behaviors so that trainees can conceptualize how the KSAs can be utilized

outside of the training context. Organizations should also conduct follow-up assess-

ments after the training to ensure that the training content is retained over the time.

Finally, it is important for organizations to create environments that support the

transfer of newly trained KSAs to the work environment. In other words, trainees

should feel that they will receive the support and feedback necessary regarding their

performance from the organization, supervisor and co-workers in order to effectively

transfer the training. One way this can be accomplished is by creating a climate in

which all employees perceive that training is an important aspect of organizational life

that will help employees become productive members of the organization (Baldwin &

Ford, 1988; Tracey et al., 1995).

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, common method variance could

be an issue as data on the predictor and criterion variables were collected from the same

source. However, we controlled for common method bias using both statistical and

procedural methods. Statistically, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test and exam-

ined the unrotated factor solution (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Results of the EFA demon-

strated that no single factor accounted for the majority of the covariance among the

measures. Procedurally, we controlled for common method bias by collecting our

predictor variables at time 1 and our criterion variables at time 2 as suggested by

Podsakoff et al. (2003).

A second limitation is that transfer of training was measured by self-report rather

than actual behavior and this may have influenced the pattern of results. Nevertheless,

in addition to the above-mentioned argument for using self-report performance

ratings, utilizing specific items and anonymous and confidential surveys might have

enhanced the accuracy of the self-report data. Also, previous research has used similar

self-report measures of training transfer (e.g. Chiaburu & Tekleab, 2005; Facteau et al.,

1995; Tesluk et al., 1995), showing evidence that trainees can accurately self-report their

levels of training transfer. Finally, as mentioned before, the results of this research

using self-report data are in fair agreement with previous transfer of training results

using both self-report and supervisor evaluations of performance (Lance et al., 2002;

Tracey et al., 1995). This convergence of results using different research paradigms

provides evidence that self-report data, collected anonymously, may be adequate for the

evaluation of transfer of training. However, for future research, we do suggest the use

of additional measures collected from several sources (e.g. supervisors, peers and

292 International Journal of Training and Development

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

subordinates) in order to reinforce the trainees ratings or, when possible, the use of

direct and objective measures of the trainee’s on-the-job performance.

A third limitation is the attrition rate of our sample between the two points of data

collection. However, our final sample of 182 participants yielded passable statistical

power to conduct our hypotheses testing.

Finally, because we collected data from only one organization, these results may not

generalize to other organizations or industries. This may be especially relevant for the

findings regarding supervisor support. It is likely that in other organizational environ-

ments, supervisory support will have a larger impact on transfer of training as evi-

denced by previous research (Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Lance et al., 2002; Rouiller &

Goldstein, 1993; Tracey et al., 1995). Consequently, future research should examine the

generalizability of our results in different organizational contexts.

Conclusions

Training practitioners and researchers have not yet extensively studied the empirical

and simultaneous effects of the three major determinants (training design, individual

characteristics and work environment) of transfer of training. This study attempted to

fill this gap by analysing the influence of these determinants on training transfer. The

findings indicated that transfer design, performance self-efficacy, training retention

and performance feedback were significantly related to transfer of training over time.

This suggests that it is important that training researchers and practitioners examine all

aspects of the training process when conducting research on transfer of training.

References

Alvarez, K., Salas, E. and Garofano, C. M. (2004), ‘An integrated model of training evaluation and

effectiveness’, Human Resource Development Review, 3, 385–416.

Baldwin, T. T. and Ford, J. K. (1988), ‘Transfer of training: a review and directions for future

research’, Personnel Psychology, 41, 63–105.

Bates, R. A., Holton, E. F. III, Seyler, D. L. and Carvalho, M. A. (2000), ‘The role of interpersonal

factors in the application of computer-based training in an industrial setting’, Human Resource

Development International, 3, 19–42.

Brinkerhoff, R. O. and Montesino, M. U. (1995), ‘Partnerships for training transfer: lessons from

a corporate study’, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 6, 263–74.

Cascio, W. F. (2000), Costing Human Resources: The Financial Impact of Behavior in Organizations, 4th

edn (Cincinnati, OH: South-Western).

Chen, H.-C., Holton, E. F. III and Bates, R. (2005), ‘Development and validation of the learning

transfer system inventory in Taiwan’, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 16, 55–84.

Chiaburu, D. S. and Tekleab, A. G. (2005), ‘Individual and contextual influences on multiple

dimensions of training effectiveness’, Journal of European Industrial Training, 29, 604–26.

Cohen, J. and Cohen, P. (1983), Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral

Sciences, 2nd edn (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum).

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A. and Noe, R. A. (2000), ‘Toward an integrative theory of training

motivation: a meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research’, Journal of Applied Psychology,

85, 678–707.

Dolezalek, H. (2004), ‘TRAINING annual industry report’, TRAINING Magazine, 42, 10. Available

at www.trainingmag.com (accessed 27 July 2005).

Dowling, P. J. and Welch, D. E. (2005), International Human Resource Management: Managing People

in a Multinational Context, 4th edn (Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western).

Facteau, J. D., Dobbins, G. H., Russell, J. E. A., Ladd, R. T. and Kudisch, J. D. (1995), ‘The influence

of general perceptions of the training environment on pretraining motivation and perceived

training transfer’, Journal of Management, 21, 1–25.

Ford, J. K., Smith, E. M., Weissbein, D. A., Gully, S. M. and Salas, E. (1998), ‘Relationships of goal

orientation, metacognitive activity, and practice strategies with learning outcomes and trans-

fer’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 218–33.

Gist, M. E., Bavetta, A. G. and Stevens, C. K. (1990), ‘Transfer training method: Its influence on

skill generalization, skill repetition, and performance level’, Personnel Psychology, 43, 501–23.

Gist, M. E., Stevens, C. K. and Bavetta, A. G. (1991), ‘Effects of self-efficacy and post-training

intervention on the acquisition and maintenance of complex interpersonal skills’, Personnel

Psychology, 44, 837–61.

Transfer of training 293

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Holton, E. F. III (1996), ‘The flawed four-level evaluation model’, Human Resource Quarterly, 7, 5–21.

Holton, E. F. III (2005), ‘Holton’s evaluation model: new evidence and construct elaborations’,

Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7, 37–54.

Holton, E. F. III, Bates, R. A, Seyler, D. L. and Carvalho, M. B. (1997), ‘Toward construct validation

of a transfer climate instrument’, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 8, 95–113.

Holton, E. F. III, Bates, R. A. and Ruona, W. E. A. (2000), ‘Development of a generalized learning

transfer system inventory’, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 11, 333–60.

Kavanagh, M. J. (1998), ‘Transfer of Training: A Multi-Stage Model Designed for Practical Use by

Organizations’, in C. Scholz and J. Zentes (eds), Strategisches Euro-Management (Stuttgart:

Schaffer-Poeschel), pp. 301–21.

Khasawneh, S., Bates, R. and Holton, E. F. III (2006), ‘Construct validation of an Arabic version of

the learning transfer system inventory for use in Jordan’, International Journal of Training and

Development, 10, 180–94.

Lance, C. E., Kavanagh, M. J. and Brink, K. E. (2002), ‘Retraining climate as a predictor of retraining

success and as a moderator of the relationship between cross-job retraining time estimates and

time to proficiency in the new job’, Group and Organization Management, 27, 294–317.

Mathieu, J. E., Tannenbaum, S. I. and Salas, E. (1992), ‘Influences of individual and situational

characteristics on measures of training effectiveness’, Academy of Management Journal, 35, 828–47.

Mathieu, J. E., Martineau, J. W. and Tannenbaum, S. I. (1993), ‘Individual and situational influ-

ences on the development of self-efficacy: implications for training effectiveness’, Personnel

Psychology, 46, 125–47.

Montesino, M. (2002), ‘Strategic alignment of training, transfer-enhancing behaviors, and training

usage: a post-training study’, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 13, 89–108.

Noe, R. A. (1986), ‘Trainee’s attributes and attitudes: neglected influences on training effective-

ness’, Academy of Management Review, 11, 736–49.

Noe, R. A., Hollenbeck, J. R., Gerhart, B. and Wright, P. M. (2006), Human Resource Management:

Gaining a Competitive Advantage, 6th edn (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Irwin).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003), ‘Common method biases in

behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies’, Journal of

Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Quinones, M. A. (1995), ‘Pretraining context effects: training assignment as feedback’, Journal of

Applied Psychology, 80, 226–38.

Reber, R. A. and Wallin, J. A. (1984), ‘The effects of training, goal setting, and knowledge of results

on safe behaviour: a component analysis’, Academy of Management Journal, 27, 544–60.

Rouiller, J. Z. and Goldstein, I. L. (1993), ‘The relationship between organizational transfer climate

and positive transfer of training’, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 4, 377–90.

Russell, J. S., Terborg, J. R. and Powers, M. L. (1985), ‘Organizational performance and organi-

zational level training and support’, Personnel Psychology, 38, 849–63.

Tannenbaum, S. I. and Yukl, G. (1992), ‘Training and development in work organizations’, Annual

Review of Psychology, 43, 399–441.

Tannenbaum, S. I., Mathieu, J. E., Salas, E. and Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (1991), ‘Meeting trainees’

expectations: the influence of training fulfillment on the development of commitment, self-

efficacy, and motivation’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 759–69.

Tesluk, P. E., Farr, J. L., Mathieu, J. E. and Vance, R. J. (1995), ‘Generalization of employee

involvement training to the job setting: individual and situational effects’, Personnel Psychology,

48, 607–32.

Tracey, J. B. and Tews, M. J. (2005), ‘Construct validity of a general training climate scale’,

Organizational Research Methods, 8, 353–74.

Tracey, J. B., Tannenbaum, S. I. and Kavanagh, M. J. (1995), ‘Applying trained skills on the job: the

importance of the work environment’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 239–52.

Tziner, A., Haccoun, R. R. and Kadish, A. (1991), ‘Personal and situational characteristics influ-

encing the effectiveness of transfer of training improvement strategies’, Journal of Occupational

Psychology, 64, 167–77.

Velada, R. and Caetano, A. (2007), ‘Training transfer: the mediating role of perception of learning’,

Journal of European Industrial Training, 31, 283–96.

Weiss, H. M. (1990), ‘Learning Theory and Industrial and Organizational Psychology’, in M. D.

Dunnette and L. M. Hough (eds), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol 1

(Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press), pp. 171–221.

Wexley, K. N. and Latham, G. P. (2002), Developing and Training Human Resources in Organizations

(Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall).

Wexley, K. N. and Nemeroff, W. (1975), ‘Effectiveness of positive reinforcement and goal setting

as methods of management development’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 64, 239–46.

294 International Journal of Training and Development

© 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2007 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

View publication stats

You might also like

- Cheat Sheet - Theorists & EducationDocument4 pagesCheat Sheet - Theorists & EducationKatie Anson100% (1)

- The Science of Training and Development in Organizations: What Matters in PracticeDocument28 pagesThe Science of Training and Development in Organizations: What Matters in PracticeMia ValdesNo ratings yet

- Master/slave (BDSM in Chicago)Document2 pagesMaster/slave (BDSM in Chicago)chicagofortressNo ratings yet

- My Leadership Development PlanDocument8 pagesMy Leadership Development Planapi-260120536100% (1)

- Hidden in Plain Sight Statistical Analysis (Summary)Document8 pagesHidden in Plain Sight Statistical Analysis (Summary)Christina StewartNo ratings yet

- Clinical Psychology EDEXCEL A2 Unit 4 BookletDocument16 pagesClinical Psychology EDEXCEL A2 Unit 4 Bookletbarrios19100% (1)

- Assignment On Job Search & RecruitmentDocument15 pagesAssignment On Job Search & RecruitmentFaisal Pervez100% (1)

- Mark Klimek Lecture 4 Canes N CrutchesDocument4 pagesMark Klimek Lecture 4 Canes N CrutchesJohn Desir100% (1)

- Job/work Environment Factors Influencing Training Transfer Within A Human Service Agency: Some Indicative Support For Baldwin and Ford's Transfer Climate ConstructDocument17 pagesJob/work Environment Factors Influencing Training Transfer Within A Human Service Agency: Some Indicative Support For Baldwin and Ford's Transfer Climate Constructsam mirrorNo ratings yet

- 2001 - Holton III - Development of A Generalized Learning Transfer System InventoryDocument28 pages2001 - Holton III - Development of A Generalized Learning Transfer System Inventoryahmed sharkasNo ratings yet

- ED492788Document8 pagesED492788amirul mukmininNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Training Activities and Transfer of Training in OrganizationsDocument20 pagesAn Investigation of Training Activities and Transfer of Training in Organizationsjoseph porterNo ratings yet

- A Conceptual Model of Training Transfer That Includes The Physical EnvironmentDocument8 pagesA Conceptual Model of Training Transfer That Includes The Physical EnvironmentNadeem AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Leadership Quarterly: Andromachi Athanasopoulou, Sue DopsonDocument19 pagesThe Leadership Quarterly: Andromachi Athanasopoulou, Sue DopsonKISHORE KANKIPATINo ratings yet

- Work Factors Influencing The Transfer Stages of Soft Skills Training - A T Literature Review PDFDocument18 pagesWork Factors Influencing The Transfer Stages of Soft Skills Training - A T Literature Review PDFBC INo ratings yet

- Employee Post-Training Behaviour and Performance: Evaluating The Results of The Training ProcessDocument23 pagesEmployee Post-Training Behaviour and Performance: Evaluating The Results of The Training ProcessImmChristianNo ratings yet

- PsychologicalScienceinthePublicInterest 2012 Salas 74 101Document29 pagesPsychologicalScienceinthePublicInterest 2012 Salas 74 101Κατερίνα Γ.ΞηράκηNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Factors Affecting Training TransferDocument60 pagesDissertation On Factors Affecting Training TransferDeepti JoshiNo ratings yet

- The Science of Training and Development PDFDocument28 pagesThe Science of Training and Development PDFChukriCharbetjiNo ratings yet

- Case Study SampleDocument7 pagesCase Study SampleEmillie Kristine SalorNo ratings yet

- Examining The Effect of Teacher's Self-Efficacy On Job SatisfactionDocument12 pagesExamining The Effect of Teacher's Self-Efficacy On Job SatisfactionNus BunNo ratings yet

- Learning TransferDocument19 pagesLearning TransferThu Hien PHAMNo ratings yet

- In PsychologyDocument30 pagesIn PsychologySirajudinNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Motivation To Transfer TrainingDocument15 pagesFactors Affecting Motivation To Transfer TrainingKenan KoçNo ratings yet

- Teaching OrganisationalDocument11 pagesTeaching OrganisationalloebevansNo ratings yet

- 352 698 1 SMDocument18 pages352 698 1 SMnad finaNo ratings yet

- Workplace Climate and Peer Support and Determinants of Training TDocument19 pagesWorkplace Climate and Peer Support and Determinants of Training TAsiyanbi Ibukun EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Impact of On The Job Training Courses On The Staff Performance (A Case Study)Document8 pagesA Study On The Impact of On The Job Training Courses On The Staff Performance (A Case Study)ChristianBaloaloaNo ratings yet

- oRzqOS EJ892382Document24 pagesoRzqOS EJ892382sretalNo ratings yet

- Influencing Factors in The Training EffectivenessDocument6 pagesInfluencing Factors in The Training EffectivenessShajith SudhakaranNo ratings yet

- Leading Change and The Challenges of Managing A Learning Organisation in Hong KongDocument18 pagesLeading Change and The Challenges of Managing A Learning Organisation in Hong KongNaufal Surya MahardikaNo ratings yet

- 70-20-10 Learning Model PDFDocument5 pages70-20-10 Learning Model PDFJuan BendeckNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework of The Factors Affecting UniDocument11 pagesTheoretical Framework of The Factors Affecting UniKyle FederiganNo ratings yet

- Social DevelopmentDocument14 pagesSocial Developmentkashif salmanNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Framework of Workplace Learning - Implications For Theory Development and Research in Human Resource DevelopmentDocument19 pagesConceptual Framework of Workplace Learning - Implications For Theory Development and Research in Human Resource DevelopmentShelby Rose LopenaNo ratings yet

- Prado Gasco Et Al 2015 KnowledgeManagementinRDTeamsDocument12 pagesPrado Gasco Et Al 2015 KnowledgeManagementinRDTeamsDeok NguyenNo ratings yet

- IJRBS 21 DocumentDocument15 pagesIJRBS 21 DocumentNus BunNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Training Transfer Between Self-Efficacy, Supervisor Support and Transfer DesignDocument35 pagesThe Relationship Training Transfer Between Self-Efficacy, Supervisor Support and Transfer DesignPetersonAugustineJadanNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Training andDocument26 pagesThe Influence of Training andVaishnavi GotmareNo ratings yet

- Design Culture, Immersion, and Visuo-Spatial Learning: Re-Envisioning TrainingDocument10 pagesDesign Culture, Immersion, and Visuo-Spatial Learning: Re-Envisioning TrainingairesNo ratings yet

- A Report/Proposal of Implementing Lean in Our Institution/ WorkplaceDocument27 pagesA Report/Proposal of Implementing Lean in Our Institution/ WorkplaceJefford Vinson ValdehuezaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of International Business Education On Career Success-Evidence From Europe2017,1Document12 pagesThe Impact of International Business Education On Career Success-Evidence From Europe2017,1kienneuNo ratings yet

- Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary PerspectivesDocument15 pagesReflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary PerspectivesJoe TotemNo ratings yet

- Corporate Sustainable Development: Testing A New Scale Based On The Mainland Chinese ContextDocument16 pagesCorporate Sustainable Development: Testing A New Scale Based On The Mainland Chinese ContextTrần Thái Đình KhươngNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Technical and Vocational Education in Iran: Jamshidi Akbar, Jamshidi LeilaDocument2 pagesEvaluation of Technical and Vocational Education in Iran: Jamshidi Akbar, Jamshidi LeilaMutiaAfifahNo ratings yet

- Development of Conceptual Bases of The Employee Life Cycle Within An OrganizationDocument14 pagesDevelopment of Conceptual Bases of The Employee Life Cycle Within An OrganizationMun MunNo ratings yet

- Faculty PerformanceDocument10 pagesFaculty PerformanceJuliet TanNo ratings yet

- Academic Performance and Perceived Employability oDocument14 pagesAcademic Performance and Perceived Employability oAsce ParraLopez PusingNo ratings yet

- A Proposed Theoretical Model For Evaluating E-LearDocument9 pagesA Proposed Theoretical Model For Evaluating E-LearDeep ShiNo ratings yet

- Three Images: What Principals Do in Curriculum ImplementationDocument36 pagesThree Images: What Principals Do in Curriculum ImplementationGiezelle LeopandoNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Mujahid AliDocument7 pagesResearch Proposal Mujahid AliMujahid AliNo ratings yet

- Transfer of Training To EmployeesDocument21 pagesTransfer of Training To EmployeesBhavika ReddyNo ratings yet

- The Organisational Learning Process As Facilitator of InnovativenessDocument22 pagesThe Organisational Learning Process As Facilitator of InnovativenessstevenisafacilitatorNo ratings yet

- LS 137 SyllabusDocument5 pagesLS 137 Syllabuslalalalala44No ratings yet

- Teacher Professional Development On Self-Determination Theory-Based Design Thinking in STEM EducationDocument14 pagesTeacher Professional Development On Self-Determination Theory-Based Design Thinking in STEM EducationLichelle BalagtasNo ratings yet

- Deposited in Repositório ISCTE-IULDocument9 pagesDeposited in Repositório ISCTE-IULamirul mukmininNo ratings yet

- Transformations? Skilled Change Agents Influencing Organisational Sustainability CultureDocument16 pagesTransformations? Skilled Change Agents Influencing Organisational Sustainability CultureRichard TineoNo ratings yet

- 2020-WangOlivierChen CreatingindividualandorganizationalreadinessforchangeconceptualizationofsystemreadinessforchangeinschooleducationDocument27 pages2020-WangOlivierChen Creatingindividualandorganizationalreadinessforchangeconceptualizationofsystemreadinessforchangeinschooleducationabbass.alseadyNo ratings yet

- Thesis Pin Aka Final Ye HeyDocument50 pagesThesis Pin Aka Final Ye HeyKaith Budomo LocadingNo ratings yet

- Adult & Continuing Professional Education Practices: Cpe Among Professional ProvidersFrom EverandAdult & Continuing Professional Education Practices: Cpe Among Professional ProvidersNo ratings yet

- Title: Instructions For UseDocument25 pagesTitle: Instructions For UseRechella BantilanNo ratings yet

- Paper6 PDFDocument12 pagesPaper6 PDFCH ELNo ratings yet

- Career Development Learning Frameworks For Work-InDocument15 pagesCareer Development Learning Frameworks For Work-InA rodricksNo ratings yet

- Human Capital Productivity and GrowthDocument59 pagesHuman Capital Productivity and Growthjhon junaidiNo ratings yet

- How Does Self-Regulated Learning in Uence Formative Assessment and Summative Grade? Comparing Online and Blended LearnersDocument31 pagesHow Does Self-Regulated Learning in Uence Formative Assessment and Summative Grade? Comparing Online and Blended Learnerscristofermarambio88No ratings yet

- Grossman & Salas (2011)Document18 pagesGrossman & Salas (2011)Diane Des RochersNo ratings yet

- Quality Training: Needs and Evaluation-Findings From A European SurveyDocument10 pagesQuality Training: Needs and Evaluation-Findings From A European SurveyYogeshNo ratings yet

- De Kiem Tra 1 Tiet Lan 1 Tieng Anh 11 Thi Diem Co Dap An PDFDocument3 pagesDe Kiem Tra 1 Tiet Lan 1 Tieng Anh 11 Thi Diem Co Dap An PDFThai Thi Hong LoanNo ratings yet

- Sample Behavior PlanDocument3 pagesSample Behavior PlanFrance BejosaNo ratings yet

- SW 4441 Anika Davis Field Placement Setting PaperDocument7 pagesSW 4441 Anika Davis Field Placement Setting Paperapi-282542988100% (1)

- (18.02.22) Unit 3. 2nd Day. Homesickness.Document3 pages(18.02.22) Unit 3. 2nd Day. Homesickness.mariela almeidarendonNo ratings yet

- Dialectical Behavioural TherapyDocument47 pagesDialectical Behavioural TherapyAthul Raj100% (1)

- The Importance of Organizational Culture For Innovation in The CompanyDocument14 pagesThe Importance of Organizational Culture For Innovation in The CompanyDanily Faith VillarNo ratings yet

- Life Coach ResumeDocument4 pagesLife Coach Resumedmipdsekg100% (1)

- Stephen Kent: Scientology Versus PsychiatryDocument24 pagesStephen Kent: Scientology Versus PsychiatryTony Ortega100% (1)

- Traditional MDD Festival by Ombatia Benard.Document3 pagesTraditional MDD Festival by Ombatia Benard.Ombatia BenardNo ratings yet

- Transactional AnalysisDocument5 pagesTransactional AnalysisSa MiNo ratings yet

- Theory of Personality Virtues - EssayDocument2 pagesTheory of Personality Virtues - EssayHuang Yuit Hwai50% (2)

- Top 10 Unethical Psychological ExperimentsDocument10 pagesTop 10 Unethical Psychological Experimentsapi-307566553No ratings yet

- Terapi Tanah LiatDocument15 pagesTerapi Tanah LiatSangaran Nair100% (3)

- Assessing Student Learning Outcomes: An Investigation of The Relationship Among Feedback MeasuresDocument5 pagesAssessing Student Learning Outcomes: An Investigation of The Relationship Among Feedback MeasuresWaqas ShamshadNo ratings yet

- Project MBA 1st YearDocument44 pagesProject MBA 1st YeardibyaranjanbhrNo ratings yet

- Presentation of Allama IqbalDocument15 pagesPresentation of Allama Iqbalkanwalsweet0% (1)

- EDU501 Midterm Short NotesDocument92 pagesEDU501 Midterm Short Noteszaiba kiranNo ratings yet

- Toward A Theory of Family CommunicationDocument22 pagesToward A Theory of Family Communicationbkmt albadarNo ratings yet

- How Playing Tetris Has Benefits For Our LifeDocument2 pagesHow Playing Tetris Has Benefits For Our LifeHana Nurul Izzah KautsaraNo ratings yet

- Journal of Sex & Marital TherapyDocument16 pagesJournal of Sex & Marital TherapyINSTITUTO VIDANo ratings yet

- The Real Reason Why TV Is Bad For The KidsDocument2 pagesThe Real Reason Why TV Is Bad For The Kidstyas andriastutiNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Interventions To Manage The Stress of Living With A New RoommateDocument8 pagesInterpersonal and Intrapersonal Interventions To Manage The Stress of Living With A New RoommateAngelo PinerNo ratings yet

- Spiritual-Self-Philo FinalDocument21 pagesSpiritual-Self-Philo FinaljulliairisNo ratings yet