Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Crossing Merfolk, The Human, A

Crossing Merfolk, The Human, A

Uploaded by

He LiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Crossing Merfolk, The Human, A

Crossing Merfolk, The Human, A

Uploaded by

He LiCopyright:

Available Formats

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the

Anthropocene in Nalo Hopkinson’s

The New Moon’s Arms and

Rivers Solomon’s The Deep

Jalondra A. Davis

F rom Syrian goddesses to Disney princesses, mermaids are mutable

figures capable of carrying a multitude of meanings. In Scaled for Success: The

Internationalization of the Mermaid, Philip Hayward argues that the mermaid is

uniquely polyvalent, that it embodies “the potential for multiple associations

and combinations of elements that accrue to a text and/or cultural entity” (3).

In our current moment of accelerating climate crisis, one meaning that the

water-dwelling, hybrid mermaid increasingly and inevitably gestures toward

is a critique of the human—and of humans’ impact on the natural world.

Though there are many ways that the mermaid possibly unsettles the human,

this unsettling is inhibited by mermaid studies’ almost exclusive focus on white

mermaids within European folklore and Western popular culture. My aim in

this paper is to specifically use Black portrayals of the mermaid to explore

critical connections between the mermaid, the human, and the racializing

reordering of the human and natural world under European conquest and

modernity.

Mermaids and water-dwelling beings have a long, rich tradition within

African diasporic culture. Ras Brown’s African-Atlantic Cultures and the South

Carolina Lowcountry undertakes a rigorous study of West and Central African

nature spirits, called simbi, some of whom come to be described as mermaids

in Lowcountry folklore (251). Ytasha Womack’s Afrofuturism, The World of

Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture and Nettrice Gaskins’s “Mami Wata Remixed:

The Mermaid in Contemporary African-American Culture” both construct

rich genealogies of a Black aquatic imaginary. These studies include feminine

water deities that take mermaid form, Black female performers’ callouts to

mermaids and water goddesses, and the mythos of nineties electronic duo

Drexciya, who imagined an aquatic civilization founded by descendants of

captive Africans cast into the sea (Gaskins 195-204; Womack 80-96). My

analysis takes the latter narrative—the proposal that African people cast

Vol. 32, No. 3, Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts

Copyright © 2021, International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts.

350 · Jalondra A. Davis

overboard during the Middle Passage transformed into oceanic beings—as its

point of departure. This idea appears in many texts besides the sonic fiction of

Drexciya, and it should be theorized as a recurring tradition in Black culture

(Davis, “Crossing Merfolk”). I call this narrative “crossing merfolk,” following

M. Jacqui Alexander’s use of “the Crossing” to describe both “the enforced

Atlantic Crossing of millions of Africans that serviced from the fifteenth

century through the twentieth the consolidation of British, French, Spanish,

and Dutch empires” (2) and “the crossroads, the space of convergence and

endless possibility” (8). Focusing my analysis on Nalo Hopkinson’s 2004 novel

The New Moon’s Arms and Rivers Solomon’s 2019 novel The Deep, I argue

that crossing merfolk narratives enhance the mermaid figure’s potential to

disrupt the hierarchical and ecologically disastrous category of the human.

By anchoring mermaid lore within the transatlantic slave trade as it launches

modernity and global racial capitalism, crossing merfolk narratives interrupt

the human. In doing so, these narratives reveal the imbrication of white

supremacist and environmental violence and embody alternative forms of

being.

Several scholars have proposed the mermaid as a figure that disrupts

Western humanism. In Mermaids and the Production of Knowledge in Early

Modern England, Tara Pedersen states that “The notion of a ‘whole human’

who exists in distinct hierarchical separation from the animal world is arguably

upset by competing popular images such as that of the mermaid” (26-27).

In From Amazons to Zombies: Monsters in Latin America, Penelope Braham

argues that “the siren’s hybridity and mutability embody resistance to modern

science and statehood, portending unfamiliar paradigms for human enterprise

and understanding” (89). And Peter Mortensen insists in “‘Half Fish, Half

Woman’: Annette Kellerman, Mermaids, and Eco-Aquatic Revisioning” that

mermaid fictions “specifically can trouble anthropocentrism, which situates

humanity outside (and above) the nonhuman biosphere, and geocentrism,

which particularly disavows humanity’s vital interdependence with aquatic

creatures and oceanic environments” (201-02). These studies signal the

mermaid’s potential challenge to the human, but they pay little attention

to the human itself as a raced, gendered, and classed construct produced

through conquest and racial chattel slavery. As Zakiyyah Iman Jackson

points out, “A critique of anthropocentricism is not necessarily a critique

of liberal humanism…Many critics of anthropocentricism have mistakenly

perceived that the problem of our time is anthropocentricism rather than a

failed praxis of being” (15). Such an analysis of the human, as not a given

but a “failed praxis of being,” is unavoidable in looking at crossing merfolk

narratives, which locate the origin of mermaids in the stratified making of

the human. According to critical humanist Sylvia Wynter, “Man”—white,

straight, male, able-bodied, propertied, rational, individual, and sovereign—is

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the Anthropocene · 351

an overrepresentation of the human, the only genre within a diverse array

of humans validated and entitled to power in the emerging colonial/modern

world, whose overrepresentation (in comparison to other humans) is key to

“all our present struggles with respect to race, class, gender, sexual orientation,

ethnicity, struggles over the environment, global warming, severe climate

change, the sharply unequal distribution of the earth resources” (260-61).

Building upon Wynter’s claim that there are indeed other genres of the

human, my article “Power and Vulnerability: Black Girl’s Magic in Black

Women’s Science Fiction” proposed the term “otherhuman” to describe the

coexisting forms of knowledge production (such as Indigenous cosmologies)

suppressed by Western coloniality/modernity (14). I expand that formulation

here to think about how Western suppression of otherhuman forms of

knowledge also upset the relationalities between people, animals, and natural

elements that provide for more sustainable ways of life. In interrupting the

human, crossing merfolk narratives highlight the human itself as not a static

being but as a violent process, which intertwined intra-human and human-

nonhuman hierarchies. Nalo Hopkinson’s The New Moon’s Arms and Rivers

Solomon’s The Deep depict disruptions of the violence of humanism, clearing

space for otherhuman ways of being and doing in both human communities

and the natural world.

Published in 2007, Nalo Hopkinson’s The New Moon’s Arms is set in a

fictional Caribbean island called Cayaba. Cayaba reflects the neocolonial

conditions of many Caribbean locales, in that the very pleasures marketed by

its tourism industry (beautiful tropical beaches, waters, and wildlife) are under

threat by foreign resource exploitation. The protagonist of the novel, a woman

named Calamity Lambkin, discovers an injured child stranded on the beach

and takes responsibility for him as she struggles with aging, family conflicts, and

the ongoing environmental threats to Cayaba. She eventually discovers that

the child she has fostered is from a local community of shapeshifting aquatic

people. The “sea people,” as Cayabans call them, are the either evolved or

magically transformed descendants of Africans aboard a slavers vessel that

was wrecked off the coast of the island. Solomon’s The Deep similarly depicts

the Middle Passage as the source for a new form of human hybrid aquatic life.

The novel builds upon the worldbuilding of nineties electronic duo Drexciya

and the hip-hop group clipping’s homage song to the duo, also entitled

“The Deep.” The Wajinru merpeople of The Deep evolve from the wombs

of pregnant African women who were cast overboard. Most of the Wajinru

cannot form long-term memories. Yetu, as historian of the Wajinru, holds all

of the generations’ memories, which she briefly imparts to the community in

a seasonal Remembrance ceremony. Yetu, who is neurodiverse, is tormented

by the traumatic memories of the Crossing. Her decision to escape rather than

take back the memories during a Remembrance ceremony incurs violent storms

journal of the fantastic in the arts

352 · Jalondra A. Davis

that suggest the effects of climate change, threatening the demise of both the

Wajinru people and the human world. My analysis focuses on how each of

these novels disrupts two facets of Western humanism: (1) epistemologies that

disregard otherhuman ways of knowing in favor of Western rationalism and

science, and (2) concepts of the normative and desirable body that maintain

colonial hierarchies and perpetuate a racialized human-animal divide. I then

briefly analyze how these disruptions play out in the novels’ representation of

crossing merfolk and human communities’ experiences of and resistance to the

Anthropocene.

Interrupting Human Epistemology: Origins of Crossing Merfolk

Crossing merfolk narratives upend the ontological violence of Western

humanism, which elevates rationalism and empirical science above other

ways of knowing. Pedersen argues that “the mermaid asks us to confront

the mechanisms of knowledge production that bring her into focus and to

interrogate the very processes of seeing and knowing” (9). Crossing merfolk

narratives heighten this confrontation of “the very processes of seeing

and knowing” through origin stories that incorporate both “evolutionary

possibility” and otherhuman cosmology (Alonso 106). The New Moon’s Arms

builds on the understanding that species can evolve over time to adjust to their

environments, but it uses memory, oral culture, and myth to both corroborate

and unsettle Western scientific certainty. Following her father’s funeral,

Calamity Lambkin finds a badly injured toddler with bluish-brown skin and

webbed feet on the beach. She immediately recalls almost drowning as a child

while playing and swimming with a similar little girl on the beach (Hopkinson

78). Along with the oral history of a slavers’ ship shipwrecked off the coast

of the island and legends of a blue devil baby that grows into a monster that

drags people under the water, Calamity’s childhood memory “echoes and

extends other stories of jumping and/or drownings in the novel” (Wisker 82).

Attempting to convince her friend Evelyn to contemplate the possibility that

the child, whom she names Agway, is a merchild, Calamity brings up a series

of stories involving creatures and adapted humans living in the ocean,

“It’s interesting, you don’t find, that we have all these stories about devils

living in the sea?”

She shrugged. “Sea kill plenty people in the history of Cayaba. It make sense

the devil would live in the sea.”

Shit, how to get her to think this through? “You know the legend about

Captain Carter?”

“Yes. Such a beautiful love story.”

“I guess. Except the lovers throw themselves into the water and die.”

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the Anthropocene · 353

She kissed her teeth. “You have to have a little romance, man. The story

says they transformed.”

“They adapted to living in the sea.” (Hopkinson 134)

It is only after Calamity has pushed Evelyn to recall these oceanic oral

narratives that Evelyn becomes willing to consider that Agway may be one

of the island’s fabled sea people, that his bodily differences are evolutionary

adaptations to aquatic life. The alternative knowledge source of oral culture

and the possibilities of evolution coalesce to form an imaginative rationality

that overturns the dominant rationality that transatlantic voyages can only

have ended in death for African people—either literal death in the ocean or

the social death of enslavement (Alonso 108; Kaplan 100).

Throughout the novel Hopkinson also presents an alternative, supernatural

origin for her crossing merfolk: that they were transformed by the Igbo goddess

Uhamiri into seals that can take human form (316). Uhamiri is associated

with Mami Wata, which refers to both a singular divinity and a group of water

spirits that syncretize Indigenous West and Central African water spirits with

“foreign” influences that include Indian snake charmers and European mermaid

lore (Chuks and Makwudo 1; Osinubi 4-5). That the sea people are initially

transformed into seals and can shed their sealskins for their more human forms

evokes the selkie, Northern European folkloric figures who live in the ocean as

seals and on land as beautiful women (Le Couteur 66). Hopkinson’s fluid and

playful intersection of Mami Wata, mermaid, and selkie lore echoes her blend

of African-derived religion, oral culture, and evolutionary science. She does

not attempt to set one authoritative account or resolve the tensions inherent

between these biological and magical origins for the crossing merfolk. The

coexistence of multiple narratives allows for coexistence of multiple realities

and epistemologies—rationality is neither surrendered as beyond Black

capacity nor privileged over the otherhuman ways of knowing represented by

orality, memory, and African cosmology.

Unlike the origin story in The New Moon’s Arms, in which the crossing

merfolk are transformed in response to a prayer, The Deep, inspired by

Black, electronic group Drexciya, depicts a process of spontaneous uterine

mutation. In the liner notes to Drexciya’s 1997 compilation album The Quest,

an “Unknown Writer” extrapolates from evidence of amphibious features

in developing fetuses and from aquatic survival instincts of newborn babies

to propose the possibility that the babies in the wombs of enslaved African

women survived (Eshun 143). Solomon’s novel fleshes out this idea as it

depicts the watery, postmortem births of a new species:

Then the surface dweller’s legs begin to splay apart, and we come under it.

We see it: the head. Our eyes widen, struck. It is not a two-legs head. There

journal of the fantastic in the arts

354 · Jalondra A. Davis

are fins at the center of its back, on its sides, and at its front. Hairless. And

darker than any land creature...What magic had intervened to transform the

pup in the womb? Was it the ocean itself, the progenitur of all life? Did the

zoti aleyu have a god after all? (Solomon 60)

While Solomon’s adaptation of this Drexciyan myth shares its mystery

and seemingly de-religious context, it also opens the door to a spiritual

explanation for the origins of the Wajinru. While The Deep does not explicitly

invoke specific African cosmologies, it hints at these very cosmologies with

the question, “Was it the ocean itself?” In African diasporic syncretic religions

such as Lucumí and Vodou, the orisha or lwa (intermediary deities or spirits

that are manifestations of a supreme God or universal life force) are associated

with natural elements such as wind and bodies of water (Alexander 303;

Brown 245). Some practitioners of these religions insist that these spirits and

the Catholic saints associated with them are personifications, faces for the

elemental force with which devotees seek communion (Hale 122). Therefore,

the “ocean itself” could refer to Yemayá, Yoruba orisha of the ocean, or Mami

Wata. Both Yemayá and Mami Wata, not coincidentally, are frequently

depicted in mermaid form (Brown 263-73; Drewal 60-62). That the “ocean

itself” is responsible for the birth of the mermaids in The Deep echoes the

divine birth of the mermaids in The New Moon’s Arms at the hands of Uhamiri

and refuses the dominance of Western science over other ways of knowing.

Interrupting Human Form: The Crossing Merfolk’s Body

Crossing merfolk narratives interrupt the human through disrupting not only

the epistemologies of Western humanism but also the body of the human.

Crossing merfolk in these two novels complicate the more typical mermaid’s

relationship to ideal human form. In Making a Splash: Mermaids (and Mermen)

in 20th and 21st Century Audiovisual Media, Philip Hayward describes

mermaids as “relatively straightforward compound figures comprising the

upper half of a female human and the lower half of a fish” (7). While the

absent genitalia and the presence of a phallus (through her tail) permit the

mermaid to be read as a queer figure, she also has features—breasts and long

flowing hair—that reassert her desirability within the heterosexual male gaze

(14-15). The tail withholds, or at least obscures, the possibility of reproductive

sex, producing ongoing mystery and allure. These physical attributes, along

with the predominance of Western narratives depicting mermaids in liaisons

with human men, support Hayward’s claim that “the potency of the mermaid

can be identified as deriving, in substantial part, from aspects of masculine

heterosexual desire (10). The typical mermaid reinforces androcentric

hierarchies in a fetishization of ideal yet unattainable femininity.

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the Anthropocene · 355

Crossing merfolk narratives often remove this emphasis upon masculine

heterosexual desire and unsettle human hierarchies. These revisions exemplify

Joy Sanchez-Taylor’s concept of “double estrangement,” through which

Sanchez-Taylor intersects Darko Suvin’s definition of cognitive estrangement

and W. E. B. Du Bois’s concept of double consciousness. Sanchez-Taylor

combines Suvin’s argument that the depiction of alternative realities within sf

can serve to defamiliarize and thus raise critiques of “real world” structures and

systems with W. E. B. Du Bois’s theorization of the sense of racial estrangement

and alienation experienced by Black people in a white supremacist society.

According to Sanchez-Taylor,

Sf authors of color present the unfamiliar as familiar to estrange their

readers, but I argue that they also frequently include critiques of sf by

altering established sf tropes…For peoples who are more likely to identify

with the alien “other” in traditional sf more than a white human narrator,

sf becomes a space to where authors of color (who are typically fans of the

genre themselves) can employ recognizable aspects of sf—tropes like the

alien, time travel, and immortality—yet also re-work these tropes to make

room for peoples of color. (7).

Nalo Hopkinson and Rivers Solomon enact double estrangement through

their reworking of the mermaid trope. Reading these novels, we are estranged

from mimetic reality through the fantastic figure of the mermaid, but we

are also estranged from how this figure typically appears. As the mermaid so

reliably conjures associations of sexuality, romance, and whimsy, its rewriting

from within Black experience unsettles such associations by centering

different bodies. Double estrangement makes the mermaid unfamiliar again

and heightens its ability to defamiliarize and critique the human. The bodily

experiences of the crossing merfolk contest interlocking forms of violence and

subordination, exemplifying how “black women’s speculative fiction highlights

the mutual constitution of (dis)ability, race, and gender and its impact on so

many of us in often oppressive and violent ways” (Schalk 83).

Of the two novels, Nalo Hopkinson’s merfolk depart the most from

the compound mermaid form. They take either aquatically adapted but

recognizably human form or, when they have their sealskins, seal form. But

unlike the Northern European selkie myths of white-skinned, raven-haired

women, Hopkinson’s selkies are, as Liza Anatol points out, rotund with brown,

faintly blue-tinged skin, and naturally occurring dreadlocks. They appear “in

stark contrast to the images marketed towards predominantly white tourists

and absorbed by the islanders themselves” (204). The mermaid is a major

marketing tool of Cayaba’s tourism industry:

journal of the fantastic in the arts

356 · Jalondra A. Davis

At the corner of each picture was a mermaid, exotically brown but not too

dark. No obvious negroes in Cayaba Tourist Board publicity, unless they were

dressed as smiling servers. The fish woman sported the kind of long, flowing

hair that most black women had to buy in a bottle of straightening solution.

They had shells covering their teacup breasts. I would love to see the shell

big enough to hide one of my bubbies (Hopkinson 222).

This passage provides a critique of colonial racialized and gendered

hierarchies. Tourism industries often continue the logics of conquest,

marketing native bodies as items of consumption along with the pristine

natural environment and imaginaries of the local culture (Sheller 13, 23).

In the same scene, Calamity protests the constant blaring of reggae rather

than an actual local music genre, tumba. Like the reggae music that projects

a vaguely Caribbean fantasy onto the specific cultural locale of Cayaba, the

mermaid’s silky locks of hair and seashell bras are importations that enable

Western consumption of a flattened, sanitized exotic. Lynda H. Schneekloth’s

“The Frontier Is Our Home” helps to contextualize Cayaba’s mermaid

billboards’ exploitative promotional strategy. Drawing connections between

colonial print cultures and contemporary representations of urban centers,

Schneekloth examines the gendered imagery of sixteenth-century colonizers’

writings and engravings, in which young, scantily clad, and fair-haired Native

maidens are aligned with the lush landscapes that they occupy, supposedly

welcoming “the white male arrivals with open arms and loving kindness” (211).

By approximating some aspects of whiteness through their flowing hair and

“exotically brown” skin, the billboard mermaids hearken back to the colonial

imagery that Schneekloth describes. These “not-too-dark” mermaids also bear

resemblance to the young women performers of the Weeki Wachee Springs

mermaid show in Florida, whose whiteness has for generations been essential

to the “family-safe yet chastely erotic spectacle” of young women swimming,

dancing, and sometimes drinking Cokes and eating bananas underwater

(Kokai 72-73). Through the portrayal of racially ambiguous mermaids, the

Cayaban tourism billboards intersect the exploitation of Indigenous women’s

bodies in narratives of conquest with that of white, idealized femininity within

mass culture. The femininity of most mermaid imagery coincides with the

feminization of colonial discourse and tourist propaganda. Therefore, it is

probably intentional that Hopkinson, in alignment with the text’s anticolonial

critique, makes the central mermaid figure of the novel not a sexualized young

woman but a toddler boy. Rather than the enticing, exotic feminine figure to

be subdued and conquered, Agway is a small child that requires care.

The merboy Agway departs from the common depiction of the mermaid

as an idealized white (or racially ambiguous) femininity. María Alonso argues

that The New Moon’s Arms’s construction of merfolk as marine-adapted

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the Anthropocene · 357

humans embodies a “diasporic marvelous realism” in which “speculation

replaces magic” (106). They do not have fish tails, though their webbed feet

and the sticky patches inside their knees that hold their legs together to

swim mimic the look and action of a mermaid’s tail. Small adaptations allow

the merfolk to survive in the water: mammalian diving reflex, lots of body

fat to protect from cold, broad chests to allow larger lung capacity, second

eyelids, and webbed extremities (Hopkinson 134-35). The sea people are

human enough that Agway’s anatomical irregularities do not raise substantial

alarm in the hospital, and he is able to live on land. Yet his body renders him

vulnerable to the systems, such as social services and medicine, that attempt

to “correct” difference. In fact, we can read Agway as (dis)abled. Sami Schalk,

also drawing on the work of Alison Kafer, who resists the hard distinction

between disability and impairment, uses (dis)ability rather than disability

to distinguish between disability and the larger social system of which one’s

specific impairment or challenge is only one part (Kafer; Schalk). Agway is

(dis)abled by his displacement from a social system and physical environment

(the community of sea people and the ocean) to another (the postcolonial

human world), which is unable to accommodate the aquatic survivals read

by Calamity and Evelyn as deformities. He waddles on land because of the

sticky skin patches on his inner legs that enable faster swimming in the sea.

Though Calamity knows, or at least suspects, that Agway is a merchild, she

allows her doctor friend Evelyn to perform a surgery to remove the skin

patches (Hopkinson 280), evoking science fiction narratives that often rely on

technological cures to erase disability.

Agway’s skin surgery brings to mind Cynthia Barounis’s analysis of disabled

swimmer Nadya Vesey’s mermaid performance, “To become human, in this

context, is to overcome one’s disability, passing as ‘normal’ among nondisabled

(in this case, land dwelling) society” (197). To pass as normal has both ableist

and white supremacist connotations. Anatol claims that some of Calamity’s

treatment of Agway—cutting the shells and dreadlocks from his hair, assuming

that his language is gibberish, and failing to learn his real name—perpetuates

“cultural imperialism” (205). Along with the cultural assaults of renaming

Agway and cutting his hair, the skin surgery is aggression in the guise of

care. This distorted care echoes the paternalistic abuse that disabled, Black,

Indigenous, and people of color communities have suffered at the hands

of social systems that try to force bodily conformity to Eurocentric norms.

However well-meaning, Evelyn and Calamity’s actions harm the merboy and

compromise his ability to survive in the water, “extending the violence of

‘universal humanity’” (Jackson 29).

Rivers Solomon’s merfolk in The Deep also depart from typical representation

of Western mermaids and trouble the hierarchies embedded in those more

popular representations. Though the novel mentions some resemblance to

journal of the fantastic in the arts

358 · Jalondra A. Davis

the Wajinru’s human ancestors, most textual details reveal alien, amphibious

creatures dramatically different from the beautiful, long-haired half-women

of myth and billboards. The Wajinru are described as hairless, scaled, and

boneless (Solomon 42), with gills and fins (Solomon 2). Unlike many

mermaids in popular culture representation and The New Moon’s Arms’s

shapeshifting seal people, they are not what Hayward defines in Making a

Splash as “transformational mermaids”; they cannot become human (188). An

African woman named Waj, who teaches the merfolk human language and

culture and whom they see as a mother of their “civilization,” initially names

them zoti aleyu, “strange fish,” demonstrating that she perceives them as more

fishlike than human (Solomon 48). A striking image of their difference comes

when Yetu tries to ward off the humans who discover her stranded in a tide

pool: “She settled for a scream, opening her mouth wide, showing rows of

sharp, long teeth, narrow and overlapping. Her eyes and nose disappeared

as her mouth expanded, her face replaced with a black, endless pit guarded

by fangs” (Solomon 72). The disappearance of Yetu’s semihuman face into a

“black, endless pit” with rows of fangs asserts her otherness and animality. Her

somewhat human features disappear completely into this scream, revealing

the porousness of the arbitrary boundaries between human and Other. The

image of a Black woman’s face disappearing into rows of fangs invokes the

ways in which Black femininity has been read as monstrous (Brooks 25-27).

Associations of Black femininity with monstrosity have inhibited Black

feminist studies’ critical explorations of monstrosity’s potential to unsettle

the logics of Western humanism. I explore this potential in my earlier work,

“Butler’s Monsters: The Grotesque and the Black Communal Body in Octavia

Butler’s Dawn”:

If a particularly black conception of humanity developed through the

attempts of black people to admit themselves to the category of human,

this conception has sought restoration of the integrity: bodily, familial, and

otherwise, excavated by enslavement and racial genocide. Therefore, a

black feminist grotesque…might resist the tropes of healing, reconciliation,

wholeness, reveling in the uneasy but radical space of abjection, porousness,

and non-closing. (310)

I read Yetu’s scream through a Black feminist grotesque to reclaim the

mermaid as monstrous and the monstrous as a productive disruption of the

human. While the mermaid is commonly analyzed within monster studies

because of its otherness and aberration of boundaries, it sits there somewhat

uneasily due to its common depiction within norms of feminine whimsy

and desirability. If the mermaid is dangerous, that danger is usually in her

sexual allure and mesmerizing song, locating her within a moral discourse as

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the Anthropocene · 359

a temptation to be resisted (Barounis 190). De-emphasizing feminine allure

and sexuality, Solomon reinserts the mermaid into a family of unsettling,

fearsome monsters, revels in her porousness, and enhances her potential for

“challenging the integrity of existing orders and systems of authority” (Braham

From Amazons to Zombies 12). Aware of the violence of two-legs both to

present-day Wajinru and their human ancestors, Yetu uses her monstrosity as

self-protection. She disappears her human face to ward off the likelihood of

human violence. This calls into question who—humans or monsters—are the

actual source of justifiable terror.

Yetu’s understanding of her bodily difference from humans extends to her

sense of an ontological difference between her and humans. When talking to

Suka, a farmer and one of the humans who cares for her as she is stranded in

the tide pool, she bristles at his suggestion that she is not an animal, but only

“animal-ish,”

Two-legs had specific ways of classifying things that Yetu didn’t like...They

organized the world as two sides of a war, the two-legs in conflict with

everything else. The way Suka talked about farming, it was as if they ruled

the land and what it produced, as opposed to—they’d just said themselves—

existing alongside it. (Solomon 84)

In this passage, Yetu critiques a major facet of Western modernity, an obsession

with taxonomy and an androcentric biological and philosophical worldview

“in which humans exist as the central and highest forms of life” (Hejnol G87).

Yet all humans were not ranked equally within this Chain of Being, as Zakiyyah

Iman Jackson points out in her theorization of how concepts of blackness and

animality developed in tandem through modernity. Interestingly, African

peoples and mermaids functioned somewhat similarly in nineteenth-century

scientific thought as alleged missing links between animal ancestors and

modern humans. Scientists examining the Feejee mermaid—P. T. Barnum’s

infamous hoax that marketed the combined skeletons of a monkey and a

large fish as a mermaid corpse—saw similarities between this “mermaid”

specimen and African people, identifying “many of the characteristics of

a human being belonging to “the Negro type” at an intercepted stage of

development” (Brink-Roby 29). The ease with which the mermaid and the

African were linked in the description of the forged Feejee mermaid speaks to

the intersection of emerging theories of race with uses of mythological hybrids

to visualize shifting scientific paradigms. As Jackson claims, “Africa was seen

as a land of new monsters” (6).

Just as The Deep asserts the monstrosity of the mermaid as a critique of

human violence, it claims the animality of the mermaid as a critique of the

Chain of Being. Yetu understands the hierarchical taxonomy that informs

journal of the fantastic in the arts

360 · Jalondra A. Davis

Suka’s perspective on agriculture, in which the land is an inert object to

be controlled, and his attempt to understand Yetu as “only animal-ish”

(Solomon 84). Her assertion, “I am animal” is an expression not only of

her physical difference from two-legs but of how that divergence produces

a differing “ecological relationality” (Frazier 67). “I am animal” is a radical

claim, the reading of which requires moving beyond a justified hesitancy in

Black studies to engage blackness in intersection with animality (Frazier 54).

Yetu is an embodiment of this fraught intersection, a location which enables

a “vision of life that is profoundly ecological, one that takes place in a social

field made up of dynamic relationships not predicated solely on domination or

exploitation” (Bennett 7). Her incredulity that humans presume to “rule the

land” rather than “exist alongside it” proposes existing alongside the land as

an otherhuman, ecological relationality.

Crossing Merfolk and the Anthropocene

The failure of Western ontology to “exist alongside the land” leads directly to

systems that destroy the livability of the land for plant, animal, and human life.

The human-mermaid interactions in both novels illustrate how environmental

violence threatens both the sea-people and their two-leg cousins, particularly

those already marginalized within the hierarchies of the human. In The New

Moon’s Arms, both the survival of the merfolk and that of the people of Cayaba

are threatened by the encroachment of salt plants that promise employment

to Cayaba’s people, sabotaging their ability to be self-sustaining and poisoning

the waters (Hopkinson 250). This conflict over the salt plants exemplifies the

effects of the Anthropocene, our current geological epoch in which human

activity is the largest force in environmental change (Tsing et al. G11). Black,

Indigenous, anticolonial, and feminist scholars intervene in the growing

literature on the Anthropocene, pointing out that humans’ role in the physical

change of the planet is not equally shared in culpability or benefits. Jane Caputi

argues in the strongest possible terms that “the Man as well as the Human in

the proposed new geological age—the Anthropocene (“Age of Man” or “Age

of Humans”)—does not signify everyone of our species. The Man behind the

Anthropocene is the motherfucker in the word’s original and worst sense (the

most vicious of oppressors and exploiters)” (3).

According to Tsing et al., “Ghosts remind us that we live in an

impossible present—a time of rupture, a world haunted with the threat of

extinction. Deep histories tumble in unruly graves that are bulldozed into

gardens of Progress” (G6). These authors’ attention to the ghostliness of the

Anthropocene align with The New Moon’s Arms’s depiction of “a shrinking

small world of pollution, takeovers, erasure, and absence” (Wisker 79).

Throughout the novel, oral culture and casual conversation call up hauntings

both of drowned Africans from sunken slaver ships and of disappearing species

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the Anthropocene · 361

of bats, seals, and fish whose habitats and populations are destroyed by the

hotels and salt plants. This linking of human and ecologies’ ghosts connects

these novels to environmental justice movements, which, as T. V. Reed claims,

“fully understand that the fate of the other-than-human world and the fate

of human beings are inextricably linked, and that the degradation of certain

‘primitive’ peoples and certain ‘underdeveloped’ places go hand in hand”

(252). The same large-scale economic powers that drive small fisheries and

salt farmers out of business also pollute the island and threaten both Cayaban

people and the sea life’s health. Calamity is initially skeptical and disinterested

in her daughter’s involvement in projects to support small-scale, sustainable

industries, reduce Cayabans’ dependence on the tourism industry, and stop

the pollution of the region (Hopkinson 198). This skepticism shifts once

Calamity is moved by her feelings of kinship to the sea people:

“Bittern. That’s what get leave behind when you manufacture salt. One

pound salt give you a pound of bittern. And bittern in high levels is toxic.

Gilmore Saline supposed to dilute in three hundred to one with water and

pipe it way out to sea. We think they releasing it strong just so into the waters

around Cayaba.”

“Oh, shit.” The water the sea people lived in. (Hopkinson 250)

Calamity is alarmed by the information about the bittern because of its

threat to Agway and his ocean family. This connection produces what Grace

Dillon calls an Indigenous scientific literacy, a scientific practice that is

informed by a “sense of spiritual interconnectedness among humans, plants,

and animals” (26). Indigenous scientific literacy suggests that “sustainability

is about maintaining the spiritual welfare of natural resources rather than

simply planning their exploitation efficiently so that humans do not run out of

necessary commodities” (Dillon 26). The New Moon’s Arms demonstrates how

the recovery of ancestral knowledge, of Indigenous scientific literacy, requires

healing of a severed relationship to the natural world. Calamity’s original

knowledge of the sea people, provided through her mother and meeting a

little sea girl as a child, is lost in her adulthood, mimicking the generational

alienation from ancestral knowledge. Her relationship with Agway (whose

name recalls Agwe, Voudon lwa of the sea) restores her connection to the

ocean. After returning Agway to his people, Calamity joins her daughter in

the protests against the salt plants. A flyer for a protest left in the zoo’s seal

enclosure suggests that the merfolk themselves (who sometimes visit the

enclosure in seal form) participate (Hopkinson 321). Therefore, Calamity’s

involvement in the movement against the salt plants signifies not only a

moment of reconciliation in the troubled relationship between her and her

daughter but also a moment of reconciliation between persons across the

journal of the fantastic in the arts

362 · Jalondra A. Davis

human-animal boundary. The sea people and the local Cayaban people

stand together against big industry in defense of their lives. Rather than the

possessive conservationism that underlies mainstream environmentalism,

Calamity’s new desire to protect the ocean is motivated by the knowledge that

she has kin in the ocean. Such relationalities, as Chelsea Frazier describes,

“trouble ecology” by “challeng[ing] the (dis)connections between human and

non- human entities, and initiat[ing] alternative notions of environmental/

ecological ethics” (46).

As Persephone Braham describes in “Song of the Sirenas: Mermaids in

Latin America and the Caribbean,” mermaid lore frequently depicts mermaids

or sirens as culpable for shipwrecks and human destruction, either through

their mesmerizing songs or ability to cause storms (150-51). Rivers Solomon

plays upon this mermaid lore but rewrites it within Black Atlantic history. In

The Deep it is the justifiable grief of crossing merfolk rather than the casual

mischief of the Western mermaid that causes human destruction. This shift of

the mermaid’s destructive power moves it away from a misogynist suspicion of

femininity to a linking of racial chattel slavery with the Anthropocene. Once

the Wajinru discover their relationship to those imprisoned on enslavers’ ships,

they also discover their power over the water: “We and the other zoti aleyu

now present gathered together to trouble the waters, to sink the ship. This

did not come about by plan, but by anguish. As all of us wept and raged, we

noticed the way that our fury made the water pulse and rise” (Solomon 62). In

hip-hop group clipping’s song “The Deep,” the merfolk launch a cataclysmic

tidal wave after humans attack their seafloor home while drilling for oil.

Solomon’s The Deep references this event, not as the central narrative of the

novel but through Yetu’s collective memory: “She saw the two-legs drowning,

but not just in water, on land, too. Water erupted from the sea and flowed onto

the surface…The drownings had been part of the Tidal Wars—that was the

name—a conflict between wajinru and two-legs” (73).

The memory of the Tidal Wars foreshadows and intercuts the storms

caused by the frenzied energy of the Wajinru left in trance state after Yetu flees

the Remembrance ceremony: “They were so lost in it, they were taking their

grief out on the whole world” (Solomon 125). The storms flood the region

where Yetu had been rescued and cared for by a rural human community and

wash away her human lover Oori’s ancestral islands, illustrating the irreparable

harm of increasing climate extremity to the communities that depend directly

on the water for survival (Hobart). While the cause of the current storm is

Yetu’s flight away from the Remembrance ceremony, we must trace her flight

back to the violence that makes the Memory so unbearable. Yetu’s intersection

of the trauma of the Crossing with the current storms answers in narrative

form Ian Baucom’s query, “Can we hold the view from the Anthropocene

and the view from the Middle Passage in concert?” (14). In History 4 Celsius:

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the Anthropocene · 363

Search for a Method in the Age of the Anthropocene, Baucom builds upon Dipesh

Chakrabarty’s radical argument for the need to desegregate human history

and natural history in the humanities. Also building upon the work of Black

Atlantic scholars Paul Gilroy and Achille Mbembe, Baucom argues that

studies of the Black Atlantic must encompass and are essential to:

an encounter with the forcings of the Anthropocene; an encounter with a

mode of vulnerability/disposability appearing not only under the generalized

“aegis of neoliberalism” but under the crash of the climate-and-capital-

changed oceans, coasts, cities, and political orderings of a new Anthropocene

nomos of the Earth; an encounter with a new mode of precariousness to

which black life is, at once, singularly subject and of which black life (or,

to be more precise to Mbembe, black “forms of life”) is/are prophetic of the

generalized” “becoming-black,” planetwide, of the “species.” (23)

The tumultuous grief of the Wajinru is a grief for the vulnerability/

disposability of black life as produced by the transatlantic slave trade: “We

are descendants of the people not on the top of the ship, but on the bottom,

thrown overboard, deemed too much of a drain on resources to stay on the

journey to their destination” (Solomon 58). It is the horror of this vulnerability/

disposability that prompts the first generation of Wajinru to remove long-term

memory from the minds of the newborn pups and create the role of Historian

to carry that burden (Solomon 63). The disruption of that role during Yetu’s

tenure unleashes a collective grief that threatens both the natural and human

world, revealing an ongoing and broadening danger that grows directly from

the precarity of Black life. By using Yetu’s plural consciousness to fuse the

Crossing, the Tidal Wars, and the current floods, Solomon collapses the space

between temporalities and links climate change to coloniality/modernity. The

relationship between the Memory and the storms parallels the relationship

between Black vulnerability/disposability and the acceleration of resource

extraction and carbon emissions launched by racial chattel slavery. The pain

of those assaulted during the transatlantic slave trade feeds directly into the

fury of the ocean, rain, and wind, as racial capitalism accelerates humanity’s

disastrous impact on the ocean and its creatures.

Conclusion

Joshua Bennett argues that within Black Atlantis myths (which overlap and

intersect what I call crossing merfolk narratives), “The haunting presence of

the Middle Passage is recalibrated toward the end of imagining an elsewhere,

however remote or deeply submerged, where black life can flourish” and

“demands a more dynamic approach to organizing life on Earth” (178).

Extending a creative tradition first established in black music, Hopkinson and

journal of the fantastic in the arts

364 · Jalondra A. Davis

Solomon suggest that a place where Black people’s lives could flourish would

be a place where other forms of being cast outside and below the Western

human could flourish as well. By locating the origins of mermaids in “the

haunting presence of the Middle Passage,” these narratives complicate the

ecocritical fantasy of the mermaid, highlighting modernity’s disastrous impact

upon otherhuman and nonhuman lifeworlds. Therefore, any unmaking of

both the ideologies and the systems that make humanity such a dangerous

force of nature must attend to the hierarchies within the human, to the

violence of conquest and racialization. Crossing merfolk that exist because of

this violence, but also exceed it, offer possibilities for a more lateral and livable

world.

Works Cited

Alexander, M. Jacqui. Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics,

Memory, and the Sacred. Duke University Press, 2005.

Alonso, María Alonso. Diasporic Marvellous Realism: History, Identity, and Memory in

Caribbean Fiction. Brill/Rodopi, 2015.

Anatol, Giselle Liza. “The Sea-People of Nalo Hopkinson’s The New Moon’s Arms:

Reconceptualizing Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic through Considerations of

Myth and Motherhood.” Diasporic Women’s Writing of the Black Atlantic, ed.

Esther Alvarez-Lopez and Emilia Maria Duran-Almarza, Routledge, 2014, pp.

202-17.

Barounis, Cynthia. “Special Affects: Mermaids, Prosthetics, and the Disabling

of Feminine Futurity “ Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 1/2, 2016,

pp. 188-204.

Baucom, Ian. History 4 Degrees Celsius. Duke University Press, 2020.

Bennett, Joshua. Being Property Myself: Blackness and the End of Man. The Belknap

Press of Harvard UP, 2020.

Braham, Persephone. From Amazons to Zombies: Monsters in Latin America. Bucknell

UP, 2015.

—. “Song of the Sirenas: Mermaids in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Scaled for

Success: The Internationalization of the Mermaid, edited by Philip Hayward, John

Libbey Publishing, 2018.

Brink-Roby, H. “Siren Canora: The Mermaid and the Mythical in Late Nineteenth-

Century Science.” Archives of Natural History, vol. 35, no. 1, 2008, pp. 1-14.

Brooks, Kinitra D. Searching for Sycorax: Black Women’s Hauntings of Contemporary

Horror. Rutgers University Press, 2018.

Brown, Ras Michael. African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry.

Cambridge UP, 2012.

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the Anthropocene · 365

Caputi, Jane. Call Your “Mutha”: A Deliberately Dirty-Minded Manifesto for the Earth

Mother in the Anthropocene. Oxford UP, 2020.

Chuks, Madukasi Francis and Kenechukwu Makwudo. “A Philosophical Appraisal

of Spirituality and Witchcraft through Mami Water Belief System in Igbe Cult

Traditional Religion in Aguleri Cosmology.” American Journal of Multidisciplinary

Research and Development, vol. 2, no. 2, 2020, pp. 1-14.

clipping. “The Deep.” The Deep, 2019. Sub Pop, https://megamart.subpop.com/

products/clipping_the-deep.

Davis, Jalondra A. “Crossing Merfolk: Mermaids and the Middle Passage in African

Diasporic Culture,” in The Routledge Handbook to Alternative Futurisms, edited by

Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay, Grace Dillon, Isiah Lavender III, and Taryne Jade

Taylor, Routledge, forthcoming 2022.

—. “Butler’s Monsters: The Grotesque and the Black Communal Body in Octavia

Butler’s Dawn.” On the Politics of Ugliness, edited by Sara Rodrigues and Ela

Przybylo, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, pp. 309-34.

—. “Power and Vulnerability: Black Girl’s Magic in Black Women’s Science

Fiction.” MOSF Journal of Science Fiction, vol. 2, no. 2, 2018, pp. 13-30.

Dillon, Grace. “Indigenous Scientific Literacies in Nalo Hopkinson’s Ceremonial

Worlds.” Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts vol. 18, no. 1, 2007, pp. 23-41.

Drewal, Henry John. “Mami Wata: Arts for Water Spirits in Africa and the

Diaspora.” African Arts, vol. 41, no. 2, 2008, pp. 60-83.

Eshun, Kodwu. “Drexciya as Spectre.” Aquatopia: The Imaginary of the Ocean Deep,

edited by Alex Farquharson and Martin Clark, Tate Nottingham Contemporary,

2013, pp. 138-46.

Frazier, Chelsea M. “Troubling Ecology: Wangechi Mutu, Octavia Butler, and Black

Feminist Interventions in Environmentalism.” Critical Ethnic Studies, vol. 2, no.

1, 2016, pp. 40-72.

Gaskins, Nettrice. “Mami Wata Remixed: The Mermaid in Contemporary African

American Culture.” Scaled for Success: The Internationalisation of the Mermaid,

edited by Philip Hayward, John Libbey Publishing, 2018, pp. 195-208.

Hale, Lindsay. Hearing the Mermaid’s Song: The Umbanda Religion in Rio De Janeiro.

University of New Mexico Press, 2009.

Hayward, Philip. Making a Splash: Mermaids (and Mermen) in 20th and 21st Century

Audiovisual Media. John Libbey Publishing, 2017.

—, editor. Scaled for Success: The Internationalization of the Mermaid. John Libbey

Publishing, 2018.

Hejnol, Andre. “Ladders, Trees, Complexity, and Other Metaphors in Evolutionary

Thinking.” Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing Heather

Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Hobart, Hiʻilei Julia. “On Oceanic Fugivity.” Items: Insights from the Social Sciences,

September 29, 2020, https://items.ssrc.org/ways-of-water/on-oceanic-fugitivity/.

Hopkinson, Nalo. The New Moon’s Arms. Warner Books, 2007.

journal of the fantastic in the arts

366 · Jalondra A. Davis

Jackson, Zakiyyah Iman. Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack

World. New York University Press, 2020.

Kafer, Allison. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indiana University, 2013.

Kaplan, Sara Clarke. “Love and Violence/Maternity and Death: Black Feminism

and the Politics of Reading (Un)Representability.” Black Women, Children, and

Families, vol. 1, no. 1, 2007, pp. 94-124.

Kokai, Jennifer A. “Weeki Wachee Girls and Buccaneer Boys: The Evolution of

Mermaids, Gender, and ‘Man Versus Nature’ Tourism.” Theatre History Studies,

vol. 31, no. 1, 2011, pp. 67-89.

Le Couteur, Peter. “Slipping Off the Sealskin: Gender, Species, and Fictive Kinship

in Selkie Folktales.” Gender Forum, vol. 55, 2015, pp. 55-82.

Mortensen, Peter. “‘Half Fish, Half Woman’: Annette Kellerman, Mermaids, and

Eco-Aquatic Revisioning.” Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, vol. 29, no. 2,

2019, pp. 201-21.

Osinubi, Taiwo Adetunji. “Provincializing Slavery: Atlantic Economies in Flora

Nwapa’s Efuru.” Research in African Literatures vol. 45, no. 3, 2014, pp. 1-26.

Pedersen, Tara E. Mermaids and the Production of Knowledge in Early Modern England.

Routledge, 2015.

Reed, T. V. “Toxic Colonialism, Environmental Justice, and Native Resistance in

Silko’s Almanac of the Dead.” MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the U.S., vol.

34, no. 2, 2009, pp. 25-42.

Sanchez-Taylor, Joy. Diverse Futures: Science Fiction and Authors of Color. Ohio State

University Press, 2021.

Schalk, Sami. Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women’s

Speculative Fiction. Duke University Press, 2018.

Schneekloth, Lynda H. “The Frontier Is Our Home.” Journal of Architectural

Education, vol. 49, no. 4, 1996, pp. 210-25.

Sheller, Mimi. Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies. Taylor and

Francis, 2003.

Solomon, Rivers. The Deep. Saga Press, 2019.

Tsing, Anna, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, eds. Arts of Living on

a Damaged Planet. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Wisker, Gina. “Middle Age, Mer People, and the Middle Passage: Nalo Hopkinson’s

Afrofuturist Journeying in The New Moon’s Arms.” Literary Afrofuturism in the

Twenty-First Century, edited by Isiah Lavender III and Lisa Yaszek, Ohio State

University Press, 2020, pp. 73-86.

Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture. Vol.

First Edition, 2013. Independent Publishers Group, 2013.

Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards

the Human, after Man, Its Overrepresentation—an Argument.” The New

Centennial Review, vol. 3, no. 3, 2003, pp. 257-337.

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Crossing Merfolk, the Human, and the Anthropocene · 367

Abstract

Mermaids are plural and complex beings with significant implications, as

human-animal-hybrids, for a critique of androcentrism and the Anthropocene.

Yet theorizations of the mermaid within monster studies rarely critically engage

Black mermaid texts. This article defines a particular recurring narrative

within Afrofuturism’s imaginings of aquatic hybrid people: what I call

Crossing Merfolk, the proposal that those lost during the Middle Passage and/

or their offspring transformed to survive in the sea. Foregrounding mermaid

studies, Black feminist critical humanisms, and feminist, anticolonial, and

environmental justice ecocriticisms in an analysis of Nalo Hopkinson’s The

New Moon’s Arms and Rivers Solomon’s The Deep, I argue that Crossing

Merfolk narratives disrupt the Human and its power over subordinated humans

and the Earth. By locating the origin of mermaids in African cosmologies and

the launch of racial chattel slavery, crossing merfolk interrogate the violent

conditions of modernity and the Anthropocene and propose otherhuman ways

of being.

journal of the fantastic in the arts

Contributors

VINCENT ALBARANO is completing his Film Studies MA at The Ohio State

University with a focus on amateur and underground cinema. He is the editor

of the Experimental Kindergarten zine, and contributor to Dangerous Encounters,

as well as the author of Pinhead Music: The Underground Sights and Sounds of

Keyser, West Virginia and the forthcoming Aesthetic Deviations and The Fantastic

Mundane: A Critical View of American Shot-on-Video Horror, 1984–1994.

M. KEITH BOOKER is Professor of English at the University of Arkansas,

Fayetteville. He is the author of dozens of published essays and the author

or editor of over sixty books on literature, popular culture, and literary and

cultural theory.

ISRA DARAISEH is Assistant Professor of English at the Arab Open University,

Kuwait. Her research focuses on the intersection between Western and Middle

Eastern cultures, as in her co-authored volume Consumerist Orientalism: The

Convergence of Arab and American Popular Cultures in the Age of Global

Capitalism (I. B. Tauris, 2019).

DR. JALONDRA A. DAVIS is a Black feminist artist-intellectual, merwomanist

Melusine, and fierce warrior mama who currently works as a University of

California Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California, San Diego. She

holds a Ph.D. in Ethnic Studies from University of California, Riverside with

a designated emphasis in Science Fiction and Technocultures and a Master

of Professional Writing from the University of Southern California. She is the

author of a coming-of-age novel, Butterfly Jar, set during the 1992 Los Angeles

Uprisings. Her research on Black speculative culture has been published in

the Museum of Science Fiction Journal of Science Fiction and Shima Journal,

with more work forthcoming in the Routledge Anthology of Co-Futurisms. Her

scholarly book project in progress, Merfolk and the Black Aquatic focuses on

mermaids, water spirits, and other aquatic-themed figures in African diasporic

literature, art, and performance.

COURTNEY J. DREYER is a PhD student in the Communication Studies

department at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Her primary research

interests include Christian media, horror cinema, and the intersections

between them.

Vol. 32, No. 3, Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts

Copyright © 2021, International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts.

Reproduced with permission of copyright owner. Further

reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Monster Theory Reading CultureDocument330 pagesMonster Theory Reading CultureBalonashe Colorate89% (9)

- Jeffrey Cohen Monster Theory Reading CultureDocument47 pagesJeffrey Cohen Monster Theory Reading CulturePaula Pepe100% (1)

- Mermaid Women by William R. MisteleDocument241 pagesMermaid Women by William R. Misteleisis_anastasiaNo ratings yet

- Encounters in The Infinite Planes Vol 02 Plane of WaterDocument33 pagesEncounters in The Infinite Planes Vol 02 Plane of WaterChristopher BruceNo ratings yet

- OotDL - Adapting The Odyssey AnthologyDocument18 pagesOotDL - Adapting The Odyssey AnthologygemmaNo ratings yet

- Noble Savages: My Life Among Two Dangerous Tribes -- the Yanomamo and the AnthropologistsFrom EverandNoble Savages: My Life Among Two Dangerous Tribes -- the Yanomamo and the AnthropologistsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- The Things That Fly in the Night: Female Vampires in Literature of the Circum-Caribbean and African DiasporaFrom EverandThe Things That Fly in the Night: Female Vampires in Literature of the Circum-Caribbean and African DiasporaNo ratings yet

- Culture HeroesDocument3 pagesCulture HeroesadimarinNo ratings yet

- Eseu Mitologie EnglezaDocument96 pagesEseu Mitologie EnglezaNandin YssuNo ratings yet

- Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and FilmFrom EverandCreaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and FilmNo ratings yet

- DruiddDocument151 pagesDruiddRodney Mackay100% (3)

- The Lamia in The Art of JW Waterhouse.Document9 pagesThe Lamia in The Art of JW Waterhouse.Maff MunaNo ratings yet

- Printer Friendly Quest For The Dragon Crown PDFDocument50 pagesPrinter Friendly Quest For The Dragon Crown PDFjosiahzimm67% (3)

- MerfolkDocument2 pagesMerfolkfishguts4everNo ratings yet

- Fairy Dictionary of Names and Terms: Common Faerie PhrasesDocument35 pagesFairy Dictionary of Names and Terms: Common Faerie PhrasesKeane Raziel100% (1)

- The Little Mermaid Study GuideDocument27 pagesThe Little Mermaid Study GuideAMNo ratings yet

- Queer PessimismDocument21 pagesQueer PessimismEthanNo ratings yet

- Afrofuturism 1AC (Non n00bs Only)Document11 pagesAfrofuturism 1AC (Non n00bs Only)Sam BaslerNo ratings yet

- Black+atlantic+queer+atlantic+Queer+imaginings+of+the+middle+passage TinsleyDocument26 pagesBlack+atlantic+queer+atlantic+Queer+imaginings+of+the+middle+passage TinsleyMarcelo SpitznerNo ratings yet

- Maroons and the Marooned: Runaways and Castaways in the AmericasFrom EverandMaroons and the Marooned: Runaways and Castaways in the AmericasRichard BodekRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Black Atlantic, Queer AtlanticDocument26 pagesBlack Atlantic, Queer AtlanticJohnBoalsNo ratings yet

- Black Atlantic, Queer AtlanticDocument26 pagesBlack Atlantic, Queer AtlanticPedroNo ratings yet

- The Original AttachmentDocument35 pagesThe Original AttachmentBarbara RoseNo ratings yet

- The Preservation of Cultural Memory in African-American FictionDocument4 pagesThe Preservation of Cultural Memory in African-American FictionIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- 1 Climate, Culture or Kinship? Explaining Human Diversity c.1500Document24 pages1 Climate, Culture or Kinship? Explaining Human Diversity c.1500therenam825No ratings yet

- Outsiders: The Humanity and Inhumanity of Giants in Medieval French Prose RomanceFrom EverandOutsiders: The Humanity and Inhumanity of Giants in Medieval French Prose RomanceNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 5.152.213.186 On Fri, 31 Mar 2023 23:39:06 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 5.152.213.186 On Fri, 31 Mar 2023 23:39:06 UTCJNo ratings yet

- Cover PageDocument41 pagesCover Pageمحمد ناصر عليويNo ratings yet

- The Littlemermaid 1995Document17 pagesThe Littlemermaid 1995sarahlind32No ratings yet

- A Material StratumDocument19 pagesA Material StratumAkhim AlexisNo ratings yet

- AmazonsDocument18 pagesAmazonsManuel ValeroNo ratings yet

- Representations of TropicsDocument16 pagesRepresentations of TropicsARK234No ratings yet

- Naturalism in American LiteratureDocument6 pagesNaturalism in American LiteratureKimYotNo ratings yet

- Helmreich Genders of Waves ColorDocument12 pagesHelmreich Genders of Waves ColormikeNo ratings yet

- Toni Morrison S Beloved From The Middle Realm To Apocalyptic VisionsDocument70 pagesToni Morrison S Beloved From The Middle Realm To Apocalyptic Visionsofentsekeorapetse4No ratings yet

- A Caribbean Woman Writer and The Dynamics of LiberationDocument8 pagesA Caribbean Woman Writer and The Dynamics of LiberationSofia VindasNo ratings yet

- Posthumanist FeminismDocument11 pagesPosthumanist FeminismFernanda Alencar PereiraNo ratings yet

- Unravelling Post-Colonial Identity An Analysis of Walcott's "Dream On Monkey Mountain" - 82-91Document10 pagesUnravelling Post-Colonial Identity An Analysis of Walcott's "Dream On Monkey Mountain" - 82-91Ayesha ArifNo ratings yet

- Literary Criticism of The Novel: 1. Donne Undone: The Journey of Psychic Re-Integration in Wilson Harris'sDocument5 pagesLiterary Criticism of The Novel: 1. Donne Undone: The Journey of Psychic Re-Integration in Wilson Harris'sAnonymous FHCJucNo ratings yet

- Amiri+Baraka+ +afro Surreal+ExpressionistDocument4 pagesAmiri+Baraka+ +afro Surreal+Expressionistnoor alqaisiNo ratings yet

- Homeless Dogs and Melancholy Apes: Humans and Other Animals in the Modern Literary ImaginationFrom EverandHomeless Dogs and Melancholy Apes: Humans and Other Animals in the Modern Literary ImaginationNo ratings yet

- 27- إنعام هاشم هادیDocument16 pages27- إنعام هاشم هادیChow Cheng YangNo ratings yet

- EhessDocument21 pagesEhessJosé Villalobos-RuizNo ratings yet

- To Be DoneDocument12 pagesTo Be DoneMohammedIlouafiNo ratings yet

- Ramirez - ChicanafuturismDocument10 pagesRamirez - ChicanafuturismOlga 'Ligeia' ArnaizNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapter4 Samskara ChapterDocument50 pages10 Chapter4 Samskara Chapterprakritilaya50% (2)

- Birds and Beasts of Ancient Mesoamerica: Animal Symbolism in the Postclassic PeriodFrom EverandBirds and Beasts of Ancient Mesoamerica: Animal Symbolism in the Postclassic PeriodNo ratings yet

- Livingston Et Al - 2017Document17 pagesLivingston Et Al - 2017okparaobogheneNo ratings yet

- Ideology Myth and Space in Cormac McCarthyDocument47 pagesIdeology Myth and Space in Cormac McCarthyMiroslav CurcicNo ratings yet

- 04 DelickaDocument11 pages04 DelickaFulguraNo ratings yet

- Sally in Three Worlds: An Indian Captive in the House of Brigham YoungFrom EverandSally in Three Worlds: An Indian Captive in the House of Brigham YoungNo ratings yet

- AfroSuper - The Power WithinDocument566 pagesAfroSuper - The Power WithinPeter JonesNo ratings yet

- Jackson On Becoming HumanDocument45 pagesJackson On Becoming Humandropdrip145No ratings yet

- Woman Triumphant: The story of her struggles for freedom, education and political rightsFrom EverandWoman Triumphant: The story of her struggles for freedom, education and political rightsNo ratings yet

- Becoming Human Matter and Meaning in AnDocument394 pagesBecoming Human Matter and Meaning in AngeoeeNo ratings yet

- Kremer PDFDocument9 pagesKremer PDFAlin M. MateiNo ratings yet

- BAUER NORTON Introduction Entangled Trajectories Indigenous and European HistoriesDocument17 pagesBAUER NORTON Introduction Entangled Trajectories Indigenous and European HistoriesJKNo ratings yet

- CLEMENT LiteraturDocument21 pagesCLEMENT Literaturhouseof comfortNo ratings yet

- The Cross-Dressed Caribbean: Writing, Politics, SexualitiesFrom EverandThe Cross-Dressed Caribbean: Writing, Politics, SexualitiesNo ratings yet

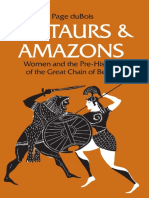

- (Women and Culture Series) Page duBois-Centaurs and Amazons - Women and The Pre-History of The Great Chain of Being - University of Michigan Press (1991) PDFDocument184 pages(Women and Culture Series) Page duBois-Centaurs and Amazons - Women and The Pre-History of The Great Chain of Being - University of Michigan Press (1991) PDFMamutfenyo100% (4)

- Are You My MotherDocument16 pagesAre You My MotherVivian Mellon SnyderNo ratings yet

- Fire on the Water: Sailors, Slaves, and Insurrection in Early American Literature, 1789-1886From EverandFire on the Water: Sailors, Slaves, and Insurrection in Early American Literature, 1789-1886No ratings yet

- Mermaids - SecretsoftheserpentDocument5 pagesMermaids - SecretsoftheserpentEugeneNo ratings yet

- The Mermaid of Kona, Hawaii Answer KeyDocument8 pagesThe Mermaid of Kona, Hawaii Answer Keyli zhangNo ratings yet

- 10 Short Biographies of Incarnated MermaidsDocument85 pages10 Short Biographies of Incarnated MermaidsZacNo ratings yet

- (EngSub) The Legend of The Blue Sea - Ep2Document43 pages(EngSub) The Legend of The Blue Sea - Ep2Try SandiNo ratings yet

- "The Wonders of Mermaid Tales Around The World": University of Santo TomasDocument10 pages"The Wonders of Mermaid Tales Around The World": University of Santo TomasLatrell CayNo ratings yet

- Hcas The Little MermaidDocument25 pagesHcas The Little MermaidcoritylovaNo ratings yet

- Smockb Assignment1Document5 pagesSmockb Assignment1api-317462017No ratings yet

- La SirenitaDocument2 pagesLa SirenitaMarina MúsicaNo ratings yet

- Complete Travel Essay Docx1Document11 pagesComplete Travel Essay Docx1api-247653471No ratings yet

- Folklore: Churile (Pronounced Choo-Ryle)Document6 pagesFolklore: Churile (Pronounced Choo-Ryle)ThePhantomStrangerNo ratings yet

- CS2 The Dark Temple r14Document92 pagesCS2 The Dark Temple r14Joe Doe100% (2)

- The Little Mermaid EssayDocument5 pagesThe Little Mermaid Essayapi-271854549No ratings yet

- Visions and Beliefs in The West of IrelandDocument213 pagesVisions and Beliefs in The West of Irelandtaraleigh100% (1)

- Ise 1 Listening 1Document4 pagesIse 1 Listening 1jessicaNo ratings yet

- Do Mermaids Really Exist?: Other Sea MonstersDocument19 pagesDo Mermaids Really Exist?: Other Sea MonstersgeraldNo ratings yet

- Master Guide 4 Card Storylines - Yugipedia - Yu-Gi-Oh! WikiDocument93 pagesMaster Guide 4 Card Storylines - Yugipedia - Yu-Gi-Oh! WikiAnaquis TarginoNo ratings yet

- Demo DLP 2022 21st Lit 2Document5 pagesDemo DLP 2022 21st Lit 2Apollo Simon T. TancincoNo ratings yet

- ANSWERS Tales Hans AndersenDocument3 pagesANSWERS Tales Hans AndersenAlejandroNo ratings yet

- The Water MythologyDocument14 pagesThe Water MythologyHanggara PadmanegaraNo ratings yet

- De Mylius HCA PDFDocument14 pagesDe Mylius HCA PDFpimiento24No ratings yet

- You and I Journal ArticleDocument14 pagesYou and I Journal Articleapi-325198524No ratings yet