Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jules - Beauvoir and Desdemona

Jules - Beauvoir and Desdemona

Uploaded by

trusteecruets0vCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Simone de Beauvoir - The Second Sex PDFDocument210 pagesSimone de Beauvoir - The Second Sex PDFmaieruchan100% (1)

- A Desire of One's Own: Psychoanalytic Feminism and Intersubjective Space - Jessica BenjaminDocument24 pagesA Desire of One's Own: Psychoanalytic Feminism and Intersubjective Space - Jessica BenjaminDaniel Andres Racines Jerves100% (1)

- Children of Blood and BoneDocument2 pagesChildren of Blood and BoneHannah Banana0% (1)

- (Ideas in Context) Andrew Fitzmaurice - Sovereignty, Property and Empire, 1500-2000-Cambridge University Press (2014)Document390 pages(Ideas in Context) Andrew Fitzmaurice - Sovereignty, Property and Empire, 1500-2000-Cambridge University Press (2014)Natko NEMECNo ratings yet

- Literary Analysis Mirrors in Je and WssDocument20 pagesLiterary Analysis Mirrors in Je and Wssapi-1993506300% (1)

- Tianni Ivey Wgss 200 MidtermDocument3 pagesTianni Ivey Wgss 200 Midtermapi-405059207No ratings yet

- Women Have No HistoryDocument3 pagesWomen Have No Historyaditi202004No ratings yet

- The Second SexDocument39 pagesThe Second SexAdbhut BalokNo ratings yet

- Wuthering Heights', The Female Version of The Male Form & The Second Sex' in ItDocument6 pagesWuthering Heights', The Female Version of The Male Form & The Second Sex' in ItIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Simone de BeauvoirDocument6 pagesSimone de BeauvoirHimanshi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Enotes AnswersDocument5 pagesEnotes AnswersForhad RaselNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument16 pagesThe University of Chicago PressAlvanis HQNo ratings yet

- Simone BeauvoirDocument6 pagesSimone BeauvoirtonydongdotcomNo ratings yet

- De BeauvoirDocument4 pagesDe BeauvoirBuğu Eylül YAŞARNo ratings yet

- Wittig PDFDocument16 pagesWittig PDFFloyd Williams100% (4)

- Simone de Beauvoir and The Second SexDocument10 pagesSimone de Beauvoir and The Second SexRachanaNo ratings yet

- Simone de Beauvoir's Work Second Sex by Iraa ChawlaDocument3 pagesSimone de Beauvoir's Work Second Sex by Iraa ChawlaSukanya Shridhar 1 9 9 0 3 5No ratings yet

- 06 Chapter 2Document32 pages06 Chapter 2Laxman PariharNo ratings yet

- The Second Sex - Issue 69 - Philosophy NowDocument3 pagesThe Second Sex - Issue 69 - Philosophy NowBanderlei SilvaNo ratings yet

- Existentialist Feminism Simone de BeauvoDocument13 pagesExistentialist Feminism Simone de BeauvoDanfNo ratings yet

- Second SexDocument7 pagesSecond SexAlishaNo ratings yet

- Simone de BeauvoirDocument10 pagesSimone de BeauvoirVũ Nguyễn Cao HuyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18Document9 pagesChapter 18Nadine DelfierroNo ratings yet

- FAQs: Dr. Sarojini SahooDocument4 pagesFAQs: Dr. Sarojini SahooSarojini SahooNo ratings yet

- The Construction of Gender: Judith Butler and Gender PerformativityDocument4 pagesThe Construction of Gender: Judith Butler and Gender PerformativitySandipan MandalNo ratings yet

- Philosophical EssayDocument6 pagesPhilosophical EssayYixing ZhangNo ratings yet

- Article de BavourDocument10 pagesArticle de BavourCristina DallosNo ratings yet

- Sem Paper FinalDocument21 pagesSem Paper Finalapi-490173413No ratings yet

- U1 T5 Reading AssignmentDocument3 pagesU1 T5 Reading AssignmentIsabelNo ratings yet

- Womanbeing and Womanself: : Characters in Black Women's NovelsFrom EverandWomanbeing and Womanself: : Characters in Black Women's NovelsNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology, Beauvoir Describes Woman As "The Other," An: The Second Sex Is An Attempt To Answer The Basic QuestionDocument6 pagesPhenomenology, Beauvoir Describes Woman As "The Other," An: The Second Sex Is An Attempt To Answer The Basic QuestionRia Roy ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT) ISSN: 2617-0299Document10 pagesInternational Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT) ISSN: 2617-0299Esraa EldadNo ratings yet

- Queer TheoryDocument3 pagesQueer TheoryAngie UzalNo ratings yet

- Contingent Ontologies Sex, Gender and Woman' in Simone de Beauvoir and Judith Butler (And MP) : STELLA SANDFORDDocument12 pagesContingent Ontologies Sex, Gender and Woman' in Simone de Beauvoir and Judith Butler (And MP) : STELLA SANDFORDConall CashNo ratings yet

- Becoming A Woman: Simone de Beauvoir On Female EmbodimentDocument5 pagesBecoming A Woman: Simone de Beauvoir On Female EmbodimentNinaBegovićNo ratings yet

- De Beauvoir PDFDocument4 pagesDe Beauvoir PDFrinu rinuNo ratings yet

- Simone de Beauvoir: The Second Sex - Introduction Woman As OtherDocument14 pagesSimone de Beauvoir: The Second Sex - Introduction Woman As OtherrajsundarsNo ratings yet

- Simone de BeauvoirDocument17 pagesSimone de BeauvoirBlair HallidayNo ratings yet

- Becoming A Woman: Simone de Beauvoir On Female EmbodimentDocument5 pagesBecoming A Woman: Simone de Beauvoir On Female EmbodimentAngel TadeoNo ratings yet

- FeminismDocument4 pagesFeminismSibel Ceaus100% (1)

- Bacevic2022 - Philosophy HerselfDocument6 pagesBacevic2022 - Philosophy Herselfpretty.ghuman21No ratings yet

- Femininity Isn't FemmeDocument13 pagesFemininity Isn't FemmeKatharina IrinaNo ratings yet

- Intro of Second SexDocument12 pagesIntro of Second Sexrajnish gandhiNo ratings yet

- Existentialist Feminist 2022Document14 pagesExistentialist Feminist 2022Pramuka MranggenNo ratings yet

- Simone de BeauvoirDocument2 pagesSimone de BeauvoiransarshkNo ratings yet

- Second Sex Intro QuotesDocument1 pageSecond Sex Intro QuotesTessa Clews100% (1)

- Final Essay #4Document3 pagesFinal Essay #4Harry HandlersNo ratings yet

- Exam Roll - RAB ENG 200052, PG CC-3.2Document4 pagesExam Roll - RAB ENG 200052, PG CC-3.2Fahmida YasminNo ratings yet

- Kirby1991 - Corporeal HabitsDocument21 pagesKirby1991 - Corporeal HabitsLuciano ArévaloNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter-3Document36 pages09 Chapter-3yashica tomarNo ratings yet

- A History of Sex - Simone de BeauvoirDocument15 pagesA History of Sex - Simone de BeauvoirDaniel Felipe Gutiérrez ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- The Second Sex - DeRYADocument2 pagesThe Second Sex - DeRYAMuzaffer Derya NazlıpınarNo ratings yet

- It Is Important To NoteDocument22 pagesIt Is Important To NoteChristiancamilogilNo ratings yet

- The Handmaid's Tale and The Passion of New Eve's Critiques of Societal Attitudes Towards Women andDocument6 pagesThe Handmaid's Tale and The Passion of New Eve's Critiques of Societal Attitudes Towards Women andDerouiche MariemNo ratings yet

- Title of Popular Song by Eagles (1972) Foucault, Michel. (1976) (1998) - The History of Sexuality Vol. 1: The Will ToDocument17 pagesTitle of Popular Song by Eagles (1972) Foucault, Michel. (1976) (1998) - The History of Sexuality Vol. 1: The Will Toapi-14486402No ratings yet

- Amy Hollywood "Sensible Ecstasy" ReviewDocument6 pagesAmy Hollywood "Sensible Ecstasy" ReviewJack MitchellNo ratings yet

- Reclaiming Femme - Queer Women of Colour and Femme IdentityDocument7 pagesReclaiming Femme - Queer Women of Colour and Femme Identityrachel leeNo ratings yet

- Existentialism NotesDocument5 pagesExistentialism NotesDwight SargaNo ratings yet

- Writing-And Reading-The Body - Female Sexuality and Recent Feminist FictionDocument24 pagesWriting-And Reading-The Body - Female Sexuality and Recent Feminist FictionMosza DiánaNo ratings yet

- Simone de Beauvoire Al Treilea SexDocument11 pagesSimone de Beauvoire Al Treilea SexDana DanutzaNo ratings yet

- Feminist View On Sex and GenderDocument18 pagesFeminist View On Sex and GenderPeterA.MacabinguilNo ratings yet

- Woman's Self-Identification: Resistance and Reluctance Under Patriarchal Society Liu Hiu Lam 20608793Document4 pagesWoman's Self-Identification: Resistance and Reluctance Under Patriarchal Society Liu Hiu Lam 20608793guap froggyNo ratings yet

- Mrs. DallowayDocument33 pagesMrs. DallowaySheena C. OcutareNo ratings yet

- India's Approach To AsiaDocument538 pagesIndia's Approach To AsiaSingh JagdishNo ratings yet

- Karnataka Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes (Reservation of Seats in Educational Institutions and of Appointments or Posts in The Services Under The State) Act, 1994Document22 pagesKarnataka Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes (Reservation of Seats in Educational Institutions and of Appointments or Posts in The Services Under The State) Act, 1994Latest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Mindanao 2020 Peace and Development FrameworkDocument16 pagesMindanao 2020 Peace and Development FrameworkJun-Jun Putot PagoyNo ratings yet

- Seperation of Power UzairDocument15 pagesSeperation of Power UzairuzairNo ratings yet

- Political Science-IIIDocument14 pagesPolitical Science-IIISrishti AgrawalNo ratings yet

- TRUSTEES OF THE PLUMBERS LOCAL UNION NO. 1 WELFARE FUND, v. BASS PLUMBING & HEATING CORP. Et Al DocketDocument2 pagesTRUSTEES OF THE PLUMBERS LOCAL UNION NO. 1 WELFARE FUND, v. BASS PLUMBING & HEATING CORP. Et Al DocketACELitigationWatchNo ratings yet

- NHD Annotated BibliographyDocument14 pagesNHD Annotated Bibliographykylenguyen70% (1)

- Field of EconomicsDocument5 pagesField of EconomicsVinod JoshiNo ratings yet

- CompiledDocument8 pagesCompiledBrigette DomingoNo ratings yet

- British American Tobacco v. Camacho Case DigestDocument3 pagesBritish American Tobacco v. Camacho Case DigestMak Francisco100% (1)

- Expected Questions From February 2021 Current AffairsDocument27 pagesExpected Questions From February 2021 Current Affairsfathima rifkaNo ratings yet

- Activity (Group5)Document5 pagesActivity (Group5)Tricia Maxine DomingoNo ratings yet

- EN - EP Brochure Citizen VoicesDocument25 pagesEN - EP Brochure Citizen Voices1234567890albertoNo ratings yet

- Public Agenda 3-5-12Document19 pagesPublic Agenda 3-5-12daniel_goodman7884No ratings yet

- As If Consenting To HorrorDocument5 pagesAs If Consenting To HorrorNabeelShahzadNo ratings yet

- Executive Assistant Job Description (For Lisa Hall)Document3 pagesExecutive Assistant Job Description (For Lisa Hall)Teuku RickyNo ratings yet

- Printslip Token lDWH54JkLUqWB8gi2yTk8rDLRsLVWBbfHIJsAFCk&cnic 45206-6263441-1&roll Number 32194613Document3 pagesPrintslip Token lDWH54JkLUqWB8gi2yTk8rDLRsLVWBbfHIJsAFCk&cnic 45206-6263441-1&roll Number 32194613sh7881807No ratings yet

- A Brief History of The Israeli-Palestinian ConflictDocument18 pagesA Brief History of The Israeli-Palestinian ConflictKamizori100% (2)

- Workplace Conflict Resolution and Management: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleDocument25 pagesWorkplace Conflict Resolution and Management: Click To Edit Master Subtitle Stylefpokoo_aikinsNo ratings yet

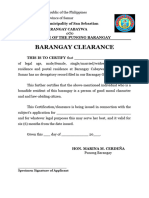

- Certification and ClearanceDocument6 pagesCertification and ClearanceElmarNo ratings yet

- English 13-10-2020Document3 pagesEnglish 13-10-2020Aakash BerliaNo ratings yet

- Indian Down Under E Paper Jan - Feb 2012Document65 pagesIndian Down Under E Paper Jan - Feb 2012indiandownunderNo ratings yet

- THE UNION OF INDIA Vs K LAKSHMINARAYANANDocument156 pagesTHE UNION OF INDIA Vs K LAKSHMINARAYANANMeghan PaulNo ratings yet

- Jaramilla - v. - Commission - On - Elections20210424-12-1gemsflDocument7 pagesJaramilla - v. - Commission - On - Elections20210424-12-1gemsflMary Ann TanNo ratings yet

- Executive Women and The Myth of Having It AllDocument13 pagesExecutive Women and The Myth of Having It AllGargi TiwariNo ratings yet

- Tabasa v. CA 500 SCRA 9Document2 pagesTabasa v. CA 500 SCRA 9Estee XoohNo ratings yet

- Growing Up and Growing Older: Feminism As A Context For Women'S LivesDocument9 pagesGrowing Up and Growing Older: Feminism As A Context For Women'S LivesFernanda SoriaNo ratings yet

Jules - Beauvoir and Desdemona

Jules - Beauvoir and Desdemona

Uploaded by

trusteecruets0vOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jules - Beauvoir and Desdemona

Jules - Beauvoir and Desdemona

Uploaded by

trusteecruets0vCopyright:

Available Formats

Vivid 1

The Situation of Woman and Desdemona in Beauvoir’s The Second Sex

I. INTRODUCTION

Simone de Beauvoir was a luminary in her serious and committed analysis of the

secondary status of women in society. The following exposition seeks to convey Beauvoir’s

intellectual project vis-à-vis the “Introduction” and “The Independent Woman” chapters of The

Second Sex. The first part of this essay will explicate Beauvoir’s interpretation of woman’s

situation and becoming, the dialectic of immanent woman as embodied Other vs. transcendent

man as disembodied Subject, and the dual problematics of woman’s dependence and

independence. Woman and desire will then be addressed as a segue into how the character of

Desdemona, in Shakespeare’s Othello, used her embodiment of love and desire to transcend her

body and reach eternal freedom.

II. THE SITUATION OF BECOMING

Simone de Beauvoir begins her discourse on the multifaceted problem of being a woman

by addressing the situation of how one becomes a woman. Beauvoir introduces her idea of

woman’s situation and how one grows into this situation by speaking to the artifice and

performativity of femininity, for “not every female human being is necessarily a woman; she

must take part in this mysterious and endangered reality known as femininity” (3). Beauvoir

touches on this notion of becoming a woman by examining how women are compelled to do

femininity, for “the individual is not free to shape the idea of femininity at will,” (724). This idea

of gender performativity as a social construct took several decades to be shepherded into the

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 2

postmodern lexicon vis-à-vis Judith Butler and Candace West & Don H. Zimmerman, whose

respective work in Gender Trouble 1 and “Doing Gender”2 asserts the idea that gender has no

natural form preceding that which has already been culturally inscribed.

Yet, the matrix of social construct and cultural inscription can be difficult to disavow.

Beauvoir noticed that some may even lament the loss of woman as the eternal feminine, that

which is the socially-sanctioned, ideal construct of woman and the corollary of her immanent

biological capaciousness for childbearing, “Tota mulier in utero: she is a womb” (Beauvoir 3).

Ideological frames of normative femininity were, and still are, held close as if they were a

religious creed or some type of abstract, symbolic idol for worship or, even more likely, one’s

own lost child that must be found and paternalistically sheltered. Therefore, losing the

stereotypical image of femininity for one who may be lamenting the loss of the eternal feminine

could mean losing a part of one’s own self, in that they are losing a part of their own cultural

myth, because “the myth of the Woman, of the Other, remains precious” (14).

It could be argued that one’s situation only becomes a situation in itself because of the

social world, in that one being is recognized by another as something else, which then places that

being into a specific social identity and situational being. When Beauvoir recognizes woman as a

situation, she is recognizing that gender is a situation, and that falling out of the boundaries

society constructs around being a woman can have devastating implications, for “a situation does

not depend on the body; it is rather the body that depends on it” (736). Butler addresses this

notion via gender dislocation, for if existence is gendered, were one to fall outside of the locus of

1 Sara Sahir, Judith Butler, 2002, p. 55-56

2 Candace West and Don H. Zimmerman, “Doing Gender,” 1987, pp. 125-127

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 3

gender norms, one would, in many ways, fall outside of existence (42). Yet, if woman remains

inside the locus of her situation, this situation essentially becomes woman’s being, because her

situation is oftentimes, and devastatingly so, the only social experience and expression she has

access to. Beauvoir addresses how even if women, or any other marginalized social group, e.g.

Jewish people and people of color, were to reject their social, situational, and stereotyped

imprints, they would still not be liberated, for to reject the notions behind one’s situation does

not abolish one’s situation: “this [...] is not a liberation for those concerned but an inauthentic

flight” (4). It is impossible to simply remove a human being from their situation, because it is

their social being that makes their situation manifest, so removing one from one’s situation

would mean removing it from its essential being, for the social matrix that situates one’s body

into a situation to begin with cannot be separated from the situation itself.

The situation of woman has also long been considered as the negation of that of men, for

anything that a woman does becomes placed in the limited particulars of her as woman. For

Beauvoir, woman’s particulars are her ovaries and uterus, which become the site for her

constraint and means of subjectivity, so that when women are in conversation with men, they

must efface their subjectivity in order to occupy a social space without having their particulars be

the underpinning of their words. Therefore, a woman’s situation essentially becomes the

acceptance or disavowal of this form of subjectivity, which society has made manifest through

her reproductive organs. This is ironic, because women do not enter into the social world as

subjects to begin with. Regardless of whether they remove their nominal situation from the

conversation or not, their bodies are still the makers of their situation: Only the physical removal

of their body would allow for the removal of this kind of subjectivity. Therefore, the situation of

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 4

woman for Beauvoir is really about negotiating one’s objectivity in the situation, for the

objectification of women is what keeps them embodied as immanent Others, while men are able

to remain as disembodied, transcendent Subjects in what Beauvoir deems “a masculine world”

(745).

III. WOMAN AS OTHER

The social inequality of men and women persists throughout western thought and can be

found at the beginnings of Abrahamic religions. The Genesis story of Eve as ostensibly created

from Adam is emblematic of woman as Other, with “humanity [...] male, and man defines

woman, not in herself, but in relation to himself; she is not considered an autonomous being” (5).

While man has never had to search for his meaning outside of himself, woman only knows

heteronomy, which is because of man’s subjectivity and what man decides woman’s utility

should be. Woman is therefore often perceived of being both from and for man, because the

historical tendency of man has been to objectify and expropriate the body of the woman; this is

when woman became sexed. When man entrenched woman in her sex, she became the Other and

implement of his pleasure. This Otherness of woman made her a vassal, “imprisoned in her

condition” (721) and destined for an existence as the hollow auxiliary to man, the essential One.

Beauvoir recognizes the historical archetypes of Otherness in order to recognize alterity

as a “fundamental category of human thought,” for the only way one can be established as the

essential One and Subject is to have the Other. This is not unlike the aforementioned need for

relational social constructs to reify one’s situation, for social reality, as Levi-Strauss concluded,

is really just a myriad of dialectical “systems of opposition: duality, alternation, opposition, and

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 5

symmetry” (7). One would be remiss to not associate Hegel when considering systems of duality

and nominal opposition, for as evidenced in his master-slave dialectic: “[...] it must proceed to

supersede the other independent being in order thereby to become certain of itself as the essential

being; secondly, in so doing it proceeds to supersede its own self, for this other is itself;

ambiguous otherness [as] an ambiguous return into itself”3. This interdependent self-reflexivity

Hegel addresses begins with an initial supplanting of the Other in order to assert oneself as the a

priori essential being; yet, this Other à la Butler can be interpreted as an alienation4, or rejection,

of some part of the Subject’s own being. In this context, the Genesis story is ironically relevant,

for if the Other is the Other because it is really just a rejected aspect of the Subject, then the story

of Eve, appearing to exist from and of Adam, suggests Eve to be a very early representation of

the rejected Other in Western history.

IV. THE PROBLEM OF DEPENDENCE

Beauvoir questions why women surrender to the sublimation of this alterity. Unlike

Jewish people or people of color, women are not oppressed because they are outnumbered (by

men), nor are there any laws or injunctions behind their subjugation. For women, there was never

a before of shared kinship or cultural tradition to fall back on. There was never a collective we

for women -- women simply refer to themselves as women (9). There is no historical precedent

beyond alterity itself. It becomes self-declaring, as women decisively claim the status of object,

because there leaves no room for subjectivity; the pronouns of she, her, and we are personal,

3 Georg Wilhelm Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, 1807, p. 111

4 Judith Butler, “Sex and Gender in Beauvoir,” 1986, p. 43

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 6

subjective pronouns. For Beauvoir, if women cannot reclaim their subjectivity in an individual or

collective context, men will always hold the exalted status of Subject. Yet, women may not have

anything to incentivize collective action. Perhaps this is why Beauvoir mentions Mitsein, or the

lack thereof, for which women strive to be a part of. Nancy Bauer articulates Heidegger’s

theoretical conception of Mitsein: “the idea, very roughly speaking, is that an absolutely,

ontologically, basic feature of being human is experiencing oneself as part of a fellowship about

which one is bound to care”5. During the time that Beauvoir wrote The Second Sex, there was not

nearly enough solidarity or shared motivation between women, nor a historical purpose to

reappropriate what was theirs, because it was never theirs to begin with. Women, in Beauvoir’s

perspective, and in the most reductive sense, simply have not had a good enough reason to

collectively organize.

The social ties opportuned to women are not collective ties that are shared with other

women who occupy a similar status with opportunities, resources, and situations. Instead, the

social ties women have are dependent ties, with women inherently bonded to the men they live

with, work for, and are provisioned by: “the tie that binds her to her oppressors is unlike any

other,” for “she is the Other at the heart of a whole whose two components are necessary to each

other” (9). There is not any becoming to this aspect of woman’s situation, for this is a dimension

of being. Why? Historical systems of social organizing for subsistence strategies, apropos of

Marx and Engels’ theory of historical materialism, would suggest that human existence and

social relationships are intrinsically based around systems of production for one’s material life

5 Nancy Bauer, “Being-with as being-against: Heidegger meets Hegel in The Second Sex,” 2001, p.130

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 7

and intercourse 6, as “men [make] their own history, but they do not make it just as they please;

[but under] circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.7” Just as

Marx and Engels were materialists in their theoretical project to free the proletariat from the

oppressive shackles of class inequalities, Beauvoir is also, in this respect, somewhat of a

materialist to the extent that women have been binded to and by men in their historical

dependence of material life and intercourse, and in their reliance of their sexed body as an

exchangeable commodity and basis of selfhood -- all under circumstances that were likewise not

chosen. Beauvoir’s intellectual vision feels raw in this image of woman as Other, fragile and

fettered by dependence.

Beauvoir addresses how this dependence is co-dependent, but not reciprocal. While men

have a biological, sexual need that is cause for their dependence on women, that dependence

does not make women more free, whereas women’s dependence on men liberates men and, in

fact, privileges them, for they occupy a better situation in the world socially, historically,

politically, and economically because “this world still belongs to men” (9-10). Both men and

women are aware of this bleak truth; what Beauvoir wants to understand is how women come to

be okay with this self-effacement. Being free, for Beauvoir, comes at a cost, but one that, in the

end, will unchain women into economic autonomy, for “when she is productive and active, she

regains her transcendence; she affirms herself concretely as subject in her projects; she senses

her responsibility relative to the goals she pursues and to the money and rights she appropriates”

(721). Women would need to relinquish their material dependence on men to become free. Kant

6 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Marx-Engels Reader, 1848, p. 150

7 Karl Marx, Der 18th Brumaire, 1851, p. 15

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 8

would maintain that this freedom, this enlightenment, requires one to find the courage and

confidence to leave behind immature dependence in order to become both personally and

publicly accountable for one’s life -- which is hard, because “it is so convenient to be

immature!”8 Therefore, because woman needs man to provide for her subsistence through his co-

dependent Subject, and because accepting one’s situation as Other brings more ease and pleasure

than developing the courage to become free, most women avoid “the anguish and stress of

authentically assumed existence” (10), while men are conferred perpetual transcendence as

Subjects.

Men have used paternalistic ideological frames to relegate women into subordinate

positions because they believe they have natural rights -- natural and superior rights to freedom

and transcendence. Men also believe that anything a woman has is because she has received it

from men: “We listen in a tone of polite indifference [...] knowing that her intelligence, in a more

or less dazzling way, reflects ideas that come from us” (13). It is because of the essential nature

of the Subject to transcend that men have always had the upper hand, while women remain

objectified, sexed Others. This objectification forces women to exist in their sexed embodiment,

and because women’s embodiment and sexedness is immanently within, of, and from their very

physical being, “there is a degradation of existence into ‘in-itself,’ of freedom into facticity” (16).

Beauvoir considers the situation of woman’s immanence her doom into inessentiality, for woman

cannot transcend her situation because she will always be transcended by man, who is the

essential transcendent Subject; yet, one can perceive Beauvoir as hopeful for woman to one day

8 Immanuel Kant, “An Answer to the Question,‘What is Enlightenment?’,” 1784, p. 54

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 9

be able to transcend her immanent embodiment and alterity -- but certainly not without

challenges.

V. THE PROBLEM OF INDEPENDENCE

Beauvoir traces the history of women’s incipient emancipation to the early

industrialization of the 18th century, when women were budding competitors to men, leaving the

work of the home for the work of the factory. This shift into modern society caused an uproar,

with anti-feminists committed to preserving the “true woman” (12) by rationalizing women’s

subordination through religion, philosophy, and science, just as people have done when

attempting to justify racial prejudice. However, Beauvoir believes that this industrial seachange

of the modern world and its subsequent effect on women’s work is complex and not expressly

emancipatory, for only in a socialist world could freedom and work co-exist; only in an

egalitarian world could social infrastructure adapt to serve women’s changing condition. “While

work alone can guarantee her concrete freedom” (721), the social organization of modern society

still situated women in a locus of heteronomy because the dominant society of the 18th and 19th

centuries was a bourgeois society. The bourgeoisie became the new arbiters of human life and

labor, exploiting working-class laborers under the capitalist enterprise of the commercial market,

where “the value of anything depended on how exchangeable it was”9. Factory life was so bleak

that some women even came to prefer the oppression of the home over the oppression of the

factory (722). The dark picture Beauvoir is painting of the independent woman renders the

modern working woman as capable of freedom through her work, though the conditions of her

9Professor Paul Kottman, Lecture 29 August 2018, The New School for Social Research, The Making of the

Modern World

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 10

work are impenetrably dire and still housed in hegemony. Woman, therefore, came to suffer

oppression both at home and at work, experiencing “the double servitude of a job and masculine

protection” (723).

A sad truth that Beauvoir illuminates is that even once woman frees herself from the

constraints of her economic dependence on man, she is only emancipated economically, for she

will still be unequal to man socially, morally, and psychologically (723). Woman remains

socially lesser than man because her situation locates her in an immanent position of otherness,

while what is inherent for man is his ability to so easily reach transcendence. The reasons behind

why woman believes that she is morally lesser than man is two-pronged: woman subscribes to

the normative belief that she is psychologically inferior to man, and woman is constantly

reminded of what society wants of her sex (and has wanted since biblical times). Because of

these reasons, she must try and reconcile that which is inside of herself without subscribing to

prescribed normatives. To be a woman is to be psychically liminal, for the woman is constantly

reminded that she is not a man, but also that she may not be doing femininity right, with the

burdens of femininity unable to be deconstructed. This creates an interstitial, labyrinthian

dynamic of having been tasked with a nature that forces woman to negotiate how, à la Judith

Butler, to “[live] one’s body in the world” (40).

This is a very different kind of dependence than the dependence men experience. Men are

not divided, at least not in respect of their natural endowments as superior beings, with their

natural presence of “virile prestige [...] he is not divided” (723). Men’s natural status in society is

one in which men take and women are taken -- women are “required to be object and prey; that

is, she must renounce her claims as a sovereign subject” (723). Beauvoir outlines such a cruel

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 11

and honest truth here. Although men are “naturally” the transcendent Subject, with women as

embodied Others, a dimension of dependence and embodiment that men do fulfill is that of their

phallus. Their phallic strength is a historic and representative motif for power and security. It is a

mimetic sword with decided strength and absolutism, a notion that Hobbes captured very well:

“the covenant without the sword are just words.” 10 With the phallus as Hobbesian sword, it

seems expressly obvious why this would foreground men’s embodiment; the phallus is what

gives meaning and madness to the covenant that men and women enter into within their dyadic

enterprise. If the phallus sexes man, might woman become man’s equal by embodying a

symbolic, isomorphic phallus? This is a trap, because no matter how capable the phallus is in

sexing man, it will never yield constraints that contain him and hold him captive in his body. The

phallus is instead the instrumental, immanent means of man’s transcendence, and like the sword,

is more an implement of power than an apparatus for dependence.

VI. WOMAN AND THE DUALITY OF DESIRE

One of the greatest of problematics for women is desire. Women’s desires enter into a

space of liminality because their desires can never be fully realized by their being, for their

desires are not of them. Because woman is constantly negotiating the state of her becoming by

fulfilling or challenging social demands, her desires are in flux and provisioned by whatever man

needs. Desire for woman is liminal, dualistic, and fractured by desiring the freedom of man while

also preserving the desires of the nesting eternal feminine that were infused into her internal

world by the women she grew up with (725). Which desire will win? Will the desire for freedom

10 Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651, p. 111

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 12

win, or the desire for the feminine? The immanence of woman as embodied Other places her

desire-situation into one of remarkable duality. The feminine will triumph if women’s singular

preoccupation is their appearance. Their space of desire will become secured and fulfilled by the

maintenance of appearance, the weapons of seduction, for “the woman [...] knows that when

people look at her, they do not distinguish her from her appearance: she is judged, respected, or

desired in relation to how she looks” (724). Woman may become secure if she satiates her desire

to keep becoming the eternal feminine, but security does not always beget freedom. And what a

terrible onus it is for one to have to choose between freedom and security.

Woman and desire are arguably synonymous with woman and freedom, for desire can be

thought of as a type of self-directed movement because it is “what makes our limbs go.”11

Pursuing the desire to achieve the same freedom as men is seen through the woman who

relinquishes her servility “by playing the game with masculine weapons: she talks instead of

listening, she flaunts clever ideas, unusual feelings; she contradicts her interlocutor instead of

going along with him, she tries to outdo him” (726). Mary Wollstonecraft doesn’t think it’s so

bad for women to do masculinity, for she believed that if one construed masculine women as

those who are as virtuous and successful as men, then “join me in wanting women to grow more

and more ‘masculine’ every day.”12 Yet, men look down on the defiant woman who fashions her

own sword to join the pleasure-ring. But why should a free woman care whether a man approves

of her newfound wielding of masculinity? Woman doesn’t pursue her desire for freedom in order

to please man; to do that would just be fulfilling the desire of the Subject while remaining the

11 Kottman, Lecture 12 September 2018, The New School for Social Research, The Making of the Modern World

12 Mary Wollstonecraft, The Vindication of the Rights of Women, 1792, p. 5

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 13

Other. The only mediation a free woman would need is that which is of her own psyche, an

internal voice that can act as a mediating, intersubjective psychic third between her and herself

that would help harness her pursuit of freedom and desire. Perhaps woman can only

reappropriate desire once she conciliates this free and decisive third with the world, the man’s

world in which she lives.

Until then, desire for woman is mimetic desire, for the only way woman’s desire can be

reified is for woman to do desire in a masculine way. This frame for desire is not unlike Rene

Girard’s theoretical concept of mimetic desire, à la Robert Pippin: “desires are everywhere

dependent on ‘mediators,’ on others who certify or make worthy their desire, others whom, given

the extreme importance of the desirer’s self-image as independent, they eventually come to hate

and compete with.” 13 The irony here comes when one considers the synthesis of both this

mimetic form of desire, along with the Hegelian role of the Other; the latter being instrumental to

desire insomuch as it is a rejected part of the Subject (master). If woman’s desire simply mimics

man’s, which instrumentally requires the woman as Other, then woman is left, indirectly, with

her own subjection (or objectification) undergirding her capacity to do masculine desire. This

mimesis reaches a profound place when Beauvoir speaks of woman as a double for man, for “she

will take charge of his worries, she will participate in his successes just as much as taking care of

her own lot, and sometimes even more so” (734). What this doubling then produces within

woman is another duality of desire, for the feminine woman is forced to reconcile her desire to

self-actualize and transcend objectification with her desire to prioritize her husband’s desires and

13 Robert Pippin, Modernism as a Philosophical Problem, 1991, p. 34

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 14

thereby negotiate the mimetic doing of desire. Why stay mired in all of this, one might ask? Well,

because both man and woman believe in man’s transcendent status.

Beauvoir mentions how desire for women is made complicated by femininity. The

problem of the sexual feminine has existed far behind and beyond the modern world, so far that

it is a historical precedent that might as well be considered a fundamentally essential quality of

becoming, in that woman is forced to learn how to please men “in order to succeed in her life as

a woman” (723). While men are able to often quickly and easily reach sexual fulfillment and

satiation without any threat to their emotional or physical wellbeing, women are at a higher risk

for sexually-transmitted diseases, don’t reach “relief” as automatically as men, and must reckon

with the prospect of pregnancy that is perpetually looming (728). Also, this leads to yet another

duality women must navigate in desire: If woman does masculinity properly, she will be

assuming a stance of domination that will prevent her from reaching an orgasm (731), for when

women initiate sexual intercourse or relationality, men become insecure or jealous: “they want to

awaken a personal sexual response in the woman, not to be selected to satisfy her need in its

generality: chosen, they feel exploited” (729). Yet, if she does femininity right, she either again

doesn’t reach an orgasm and feels “had,” or if she does reach an orgasm, she “will want to hold

on to her lover for a longer time” because it is “pleasure, far from freeing her, [that] binds her”

(733). Or, if women initiate their own desire or give in to the desire of men too much, she risks

being thought of and talked about as lascivious. And yet another frightening truth and challenge

to women’s fulfillment of desire is that they are not as physically strong as men, so while men

have nothing to fear or be insecure over in their sexual and romantic pursuits, women must be

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 15

constantly vigilant of ensuring that their bodies and beings are safe and free from the potential

harm of an aggressive or abusive partner.

Beauvoir elucidates an alternative option for women’s desire trajectory through the idea

of monetizing erotic practices. Women can pay for the provisions men provide sexually, yet most

women who opportune themselves of this strategy are wealthy, and often older, women: “By

paying the male, they make an instrument of him, permitting them to use him with disdainful

abandon” (728). The reason why it is commonplace for older women to pursue this method is

because younger women may be more susceptible to growing an attachment or sentiment to their

lover. Therefore, even if women were to be able to afford a sexual, transactional relationship, the

fulfillment of desire and erotic freedom for most women is often constituted in a secure space of

sexual, physical, and emotional security.

One of the most compelling dimensions of Beauvoir’s stance on how women negotiate

the sphere of sex and desire is her illumination of the double standard around Subjectivity and

Desire. While men are able to become Subjects through both satisfying women and being

satisfied by women, women are not able to experience the same subject-identification. When

women pleasure men, they are both giving them pleasure and also reaffirming their own object-

worth. Although women may look at this sexual solicitation as a form of generosity (729), it is

really just a way of maintaining one’s body as an object-offering. The insidious aspect of this is

that even once woman uses her will and initiative to assert her desire, to use her body as an

instrument for her taking, “she is [still] a utensil” (730), and is unable to elevate herself to the

status of man.

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 16

This unfortunate situation foregrounds woman’s sexual life into a desire-deadlock. If

woman does not pursue her sexual desire, she is left as an object for the taking, “she limply gives

in to the spell of arousal, she is fascinated by the male who picks her like a fruit” (730), and if

she pursues her sexual desire, she has a chance at willing her flesh into whatever situational form

and place of her choosing. Yet, if she takes too much from man, or even gives too much to man,

she will regress back into object:“if she admits her pleasure, she is acknowledging her

submission” (730). This predicates the problem and duality of woman’s desire and subsequent

freedom into a sisyphean tragedy. While man’s nature is not to be chosen to receive, but to take

and conquer, (which is consistent with conceptualizing the phallic sword as material and

symbolic strength), woman is left entangled in an immanence that is what it is only because of its

dialectical relation and referentiality to man. Woman’s nature remains fashioned as a lacking

receptacle, a cavity for unbridled receiving and “losing” -- and “she remains lost” (730). So, how

is woman ever to be found? How is freedom ever to be found, if she, and it, remain lost? The

character of Desdemona in Shakespeare’s Othello may help illustrate the possibilities for woman

and desire, love, and freedom.

VII. DESDEMONA: IMMANENT AND TRANSCENDENT

When Beauvoir mentions woman as remaining lost by “consenting to make herself flesh

through her sexual arousal, anticipation, and promise,” she also writes that woman can only win

by losing (730). The following delineates how the character of Desdemona in Shakespeare’s

Othello wins through her tragic and profound death, by losing the very flesh that in fact allowed

her to become wholly free and transcendent. Desdemona’s death delivers her freedom, but only

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 17

through the loss of her two means of captivity -- the primary captivity of her body and the

secondary captivity of Othello’s transcendence. The immanence of Desdemona and

transcendence of Othello mutually-reinforced the objectification of her being as Other, while

Othello was able to remain as the disembodied, transcendent Subject until Desdemona’s death,

which is when she uses her immanent desire and love to self-actualize subjectivity, agency, and

freedom. In the end, Desdemona has won not because she loses her body, but because she uses

the passions that her body provided to find freedom and transcendence.

There is much one could say and write for the characters and relationship of Desdemona

and Othello. However, the remainder of this essay will focus on one interpretation of

Desdemona’s impending transcendence and subsequent culmination in freedom. Desdemona’s

first sign of transcendence is when she defied her father, Brabantio, by marrying Othello without

Brabantio’s permission. Desdemona did not seek her father’s approval beforehand. Instead, she

wed Othello through her own will and freedom. This event disgraced her father, who proclaimed

in anger and dismay upon hearing of her becoming newly betrothed, “O heaven! How got she

out? O treason of the blood! Fathers, from hence trust not your daughters’ minds by what you see

them act” (Act I, scene i); and when confronting Othello, “O thou foul thief, where hast thou

stow’d my daughter?” (Act I, scene ii) . In both of these utterances, Brabantio is using figurative

language to express Desdemona as an animal who has escaped captivity or as booty that was

stowed away for safekeeping.

However, Desdemona transcends this objectivity because it is her very word, and not

Othello’s, that legitimates her marriage to Othello in front of her father and the councilmen. This

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 18

instance marks Desdemona as a “cosmopolitan 17th century proto-feminist”14, for not only does

she deviate from the gendered expectations of her father and the time, she also eclipses Othello

in authorizing the legitimacy of their marriage. This is important, because at this point in the

play, Othello possesses a status that is more illustrious and esteemed than Desdemona, yet her

voice holds primacy for the sanctioning of their love and commitment. Othello’s status quickly

falls soon after this, as he becomes caught within Iago’s web of deceit, which further exalts

Desdemona. Yet, whatever Iago unveiled was arguably already there to begin with, with the

character of Iago as a type of imp uprooting the most horrific of the human condition within

Othello. Desdemona, in contrast, is stable in her integrity, and the security and confidence she

has in herself, for when wrongfully aggressed by Othello, she does not retort combatively;

instead, she stands her guard with calm and strong resolve: “I have not deserved this,” which is

soon followed by “I will not stay to offend you” (Act IV, scene i). Desdemona is patient in trying

to understand Othello’s fury and the possible remedy for this sudden calamity. Her incipient

transcendence is again here felt by a type of “hermeneutic capaciousness”15 .

Desdemona’s body now enters into this picture, because the issue at the heart of Othello’s

anger is a carnal issue16. Othello is not infuriated by the idea of Desdemona falling in love with

Cassio; he is brought to a savage rage because what is called into question is Desdemona’s body.

It is not her heart that he fears may have been reappropriated, it is her body. That it is her body

that he fears has been taken from him is similar to Brabantio’s prior exclamation of Desdemona,

14 Kottman, Lecture 24 October 2018, The New School for Social Research, The Making of the Modern World

15 Kottman, Lecture 24 October 2018, The New School for Social Research, The Making of the Modern World

16 Kottman, Lecture 24 October 2018, The New School for Social Research, The Making of the Modern World

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 19

with his analogous language likening her to the booty one might find on a ship or to a farm

animal that has been let out of its bin. What this play’s primary problematic becomes, then, is an

issue with Desdemona’s body, which is essentially an issue with Desdemona as Other. However,

Desdemona solidly positions herself as Subject by remaining secure in her love and fidelity --

and by never questioning Othello’s love and fidelity. Desdemona has taken it upon herself to be

the representation of love and security through both her love for Othello and the love Othello

once had for her that he was unable to stand by. Desdemona is more secure than Othello and

does not need to fight him on his false claims. Instead, she can only hope that he comes to see

her as who she really is: “I hope my noble lord esteems me honest” (Act IV, scene ii).

Desdemona is so secure in her being, as Subject, that she tries to rescue the Othello she knew and

loved through her body and its passions. Instead she rescues herself, ironically, through the loss

of both.

In the final scene of Desdemona and Othello, Desdemona asks Emilia to dress her and

Othello’s bed with their wedding sheets. Desdemona is setting up the scene for her love and

desire to hold sway, though her agentive, desirous body and strong heart is not enough to reel

Othello in from the Iago-plague. The idea of Desdemona sharing her body-object, i.e. what

Othello considers to be his property, compromised Othello’s masculinity -- his masculine control,

power, and transcendence, for if Othello is “man-enough,” why would Desdemona need to seek

sexual pleasure elsewhere? Through the use of her body, Desdemona risks her life to try and

meet Othello halfway in love and desire. But he does not submit. His phallic pride and now

pseudo-transcendence brings Othello to kill the source of his love and desire. It is a tragedy that

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 20

Othello is so entirely blinded by his jealousy and ostensibly-fallen phallus that he destroys

Desdemona and the love they shared, as well as his own once-strong and transcendent character.

Desdemona, on the other hand, enters her final scene fully aware of the prospect of death

that awaits her. Desdemona bravely attempts to pacify Othello’s violent rage through both her

body and heart, through the desire and love she has for him, and through the desire and love she

believes might still be alive somewhere beneath his rage. Here, Desdemona’s desire and love can

be looked at as the inviolate means for manifesting both body and heart transcendence.

Desdemona uses the one thing her situation has empowered her with -- her body, her physical

being17, the home of both her sexual agency and love -- to try and recover Othello and the love

they shared. That is her agency. That is her freedom. Desdemona risks her life and never doubts

herself or the integrity of her feelings and character. It is the strength of her immanence that frees

Desdemona and allows her to face death with courage, wisdom, and honesty. She is able to find

her freedom, her own transcendence, by risking her life, by standing by the love and desire that

her body provided -- by choosing love.

While Desdemona chose love, and let the love and desire of her body bring her to full

transcendence, indeed used her body to lose her body, Othello fell from eminent transcendence to

flaccid embodiment. The idea of Desdemona sleeping with Cassio originally made Othello feel

disempowered and emasculated, but his real downfall was letting the imp of jealousy destroy his

love and desire. At the end of the play, once he killed his love and realized his grave mistake,

Othello is left to reconcile his failure, which is, for him, a failed masculinity that lives within his

failed body. The body that was once home for his transcendence and the desire and love for

17 Kottman, Lecture 24 October 2018, The New School for Social Research, The Making of the Modern World

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 21

Desdemona failed him. “My life upon her faith!” (Act I, scene iii) proclaimed Othello in the

beginning of the play, wagering his life on Desdemona’s faithfulness. Yet both Othello and

Desdemona’s lives were lost despite her faithfulness. It was Othello’s lack of faithfulness that

was the cause of both of their deaths. Perhaps a more appropriate and prescient remark would

have been, “my life upon my faith,” or “our lives upon my faith”. The transcendence of Othello

became the uncontrollable transcendence of his flighty mind when dosed with a drop of fear and

doubt. So Othello, too, had a “hermeneutic capaciousness,” but one that ultimately destroyed his

love and freedom.

VIII. CONCLUSION

Simone de Beauvoir was illustrious in her theoretical analysis of the problem of sex,

which is why she is accredited among the pantheon of modern social thinkers. The Second Sex à

la the “Introductory” and “The Independent Woman” chapters offers a theoretical contribution to

the plight of women that is deep and complex, and one that ultimately contemplates “how, in the

feminine condition of subjugation, does the woman realize freedom?” 18 It has been argued herein

that woman, à la Desdemona, can realize freedom and achieve transcendence by using her body,

the very situation that can likewise constrict and control her; fortunately, death is not always

necessary for freedom.

While The Second Sex contributes some of the most deep and disturbing truths

concerning the problem of gender in general and the situation of woman in specific, one can say

the same for Shakespeare’s Othello. Desdemona used her delimited situation of immanence to

18 Kottman, Lecture 17 October 2018, The New School for Social Research, The Making of the Modern World

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 22

surpass this situation and reach freedom through her transcendent love and desire. Desdemona

never let go of what her body allowed her to be -- a loving, desirous, committed and faithful

woman for and of herself, risking her life and choosing love to stand by who she was. It is an

absolute tragedy that the only way for Desdemona to reach the apotheosis of her freedom and

agency meant losing the very means that brought her there. Although “she could only win by

losing” (730), Desdemona achieved transcendence by standing by her body and using her body

to stand by herself.

© Jules Vivid 2018

Vivid 23

Bauer, Nancy. “Being-with as being-against: Heidegger meets Hegel in The Second Sex,”

Continental Philosophy Review, (34): 2001. p. 130.

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. New York: Knopf. 1952. pp. 3-17, 721-751.

Butler, Judith. “Sex and Gender in Beauvoir,” Yale French Studies, (72): 1986. p. 43.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm. Phenomenology of Spirit. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1977, p.

111.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1998. p. 111.

Kant, Immanuel. “An Answer to the Question, ‘What is Enlightenment?’” in Political Writings.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1970. p. 54.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. Marx-Engels Reader. 1848. p. 150.

Marx, Karl. Der 18th Brumaire. 1851. p. 15.

Pippin, Robert. Modernism as a Philosophical Problem: On the Dissatisfactions of European

High Culture. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 1991. p. 34.

Sahir, Sara. Judith Butler, London: Routledge. 2002. p. 55-56.

Shakespeare, William. Othello. St. Paul, Minn.: EMC/Paradigm Publishing. 2005. Web.

West, Candace and Don H. Zimmerman. “Doing Gender.” Gender and Society, 1, 2 (1987):

125-127.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. The Vindication of the Rights of Women. Jonathan Bennett 2017. Web. p. 5.

© Jules Vivid 2018

You might also like

- Simone de Beauvoir - The Second Sex PDFDocument210 pagesSimone de Beauvoir - The Second Sex PDFmaieruchan100% (1)

- A Desire of One's Own: Psychoanalytic Feminism and Intersubjective Space - Jessica BenjaminDocument24 pagesA Desire of One's Own: Psychoanalytic Feminism and Intersubjective Space - Jessica BenjaminDaniel Andres Racines Jerves100% (1)

- Children of Blood and BoneDocument2 pagesChildren of Blood and BoneHannah Banana0% (1)

- (Ideas in Context) Andrew Fitzmaurice - Sovereignty, Property and Empire, 1500-2000-Cambridge University Press (2014)Document390 pages(Ideas in Context) Andrew Fitzmaurice - Sovereignty, Property and Empire, 1500-2000-Cambridge University Press (2014)Natko NEMECNo ratings yet

- Literary Analysis Mirrors in Je and WssDocument20 pagesLiterary Analysis Mirrors in Je and Wssapi-1993506300% (1)

- Tianni Ivey Wgss 200 MidtermDocument3 pagesTianni Ivey Wgss 200 Midtermapi-405059207No ratings yet

- Women Have No HistoryDocument3 pagesWomen Have No Historyaditi202004No ratings yet

- The Second SexDocument39 pagesThe Second SexAdbhut BalokNo ratings yet

- Wuthering Heights', The Female Version of The Male Form & The Second Sex' in ItDocument6 pagesWuthering Heights', The Female Version of The Male Form & The Second Sex' in ItIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Simone de BeauvoirDocument6 pagesSimone de BeauvoirHimanshi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Enotes AnswersDocument5 pagesEnotes AnswersForhad RaselNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument16 pagesThe University of Chicago PressAlvanis HQNo ratings yet

- Simone BeauvoirDocument6 pagesSimone BeauvoirtonydongdotcomNo ratings yet

- De BeauvoirDocument4 pagesDe BeauvoirBuğu Eylül YAŞARNo ratings yet

- Wittig PDFDocument16 pagesWittig PDFFloyd Williams100% (4)

- Simone de Beauvoir and The Second SexDocument10 pagesSimone de Beauvoir and The Second SexRachanaNo ratings yet

- Simone de Beauvoir's Work Second Sex by Iraa ChawlaDocument3 pagesSimone de Beauvoir's Work Second Sex by Iraa ChawlaSukanya Shridhar 1 9 9 0 3 5No ratings yet

- 06 Chapter 2Document32 pages06 Chapter 2Laxman PariharNo ratings yet

- The Second Sex - Issue 69 - Philosophy NowDocument3 pagesThe Second Sex - Issue 69 - Philosophy NowBanderlei SilvaNo ratings yet

- Existentialist Feminism Simone de BeauvoDocument13 pagesExistentialist Feminism Simone de BeauvoDanfNo ratings yet

- Second SexDocument7 pagesSecond SexAlishaNo ratings yet

- Simone de BeauvoirDocument10 pagesSimone de BeauvoirVũ Nguyễn Cao HuyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18Document9 pagesChapter 18Nadine DelfierroNo ratings yet

- FAQs: Dr. Sarojini SahooDocument4 pagesFAQs: Dr. Sarojini SahooSarojini SahooNo ratings yet

- The Construction of Gender: Judith Butler and Gender PerformativityDocument4 pagesThe Construction of Gender: Judith Butler and Gender PerformativitySandipan MandalNo ratings yet

- Philosophical EssayDocument6 pagesPhilosophical EssayYixing ZhangNo ratings yet

- Article de BavourDocument10 pagesArticle de BavourCristina DallosNo ratings yet

- Sem Paper FinalDocument21 pagesSem Paper Finalapi-490173413No ratings yet

- U1 T5 Reading AssignmentDocument3 pagesU1 T5 Reading AssignmentIsabelNo ratings yet

- Womanbeing and Womanself: : Characters in Black Women's NovelsFrom EverandWomanbeing and Womanself: : Characters in Black Women's NovelsNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology, Beauvoir Describes Woman As "The Other," An: The Second Sex Is An Attempt To Answer The Basic QuestionDocument6 pagesPhenomenology, Beauvoir Describes Woman As "The Other," An: The Second Sex Is An Attempt To Answer The Basic QuestionRia Roy ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT) ISSN: 2617-0299Document10 pagesInternational Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT) ISSN: 2617-0299Esraa EldadNo ratings yet

- Queer TheoryDocument3 pagesQueer TheoryAngie UzalNo ratings yet

- Contingent Ontologies Sex, Gender and Woman' in Simone de Beauvoir and Judith Butler (And MP) : STELLA SANDFORDDocument12 pagesContingent Ontologies Sex, Gender and Woman' in Simone de Beauvoir and Judith Butler (And MP) : STELLA SANDFORDConall CashNo ratings yet

- Becoming A Woman: Simone de Beauvoir On Female EmbodimentDocument5 pagesBecoming A Woman: Simone de Beauvoir On Female EmbodimentNinaBegovićNo ratings yet

- De Beauvoir PDFDocument4 pagesDe Beauvoir PDFrinu rinuNo ratings yet

- Simone de Beauvoir: The Second Sex - Introduction Woman As OtherDocument14 pagesSimone de Beauvoir: The Second Sex - Introduction Woman As OtherrajsundarsNo ratings yet

- Simone de BeauvoirDocument17 pagesSimone de BeauvoirBlair HallidayNo ratings yet

- Becoming A Woman: Simone de Beauvoir On Female EmbodimentDocument5 pagesBecoming A Woman: Simone de Beauvoir On Female EmbodimentAngel TadeoNo ratings yet

- FeminismDocument4 pagesFeminismSibel Ceaus100% (1)

- Bacevic2022 - Philosophy HerselfDocument6 pagesBacevic2022 - Philosophy Herselfpretty.ghuman21No ratings yet

- Femininity Isn't FemmeDocument13 pagesFemininity Isn't FemmeKatharina IrinaNo ratings yet

- Intro of Second SexDocument12 pagesIntro of Second Sexrajnish gandhiNo ratings yet

- Existentialist Feminist 2022Document14 pagesExistentialist Feminist 2022Pramuka MranggenNo ratings yet

- Simone de BeauvoirDocument2 pagesSimone de BeauvoiransarshkNo ratings yet

- Second Sex Intro QuotesDocument1 pageSecond Sex Intro QuotesTessa Clews100% (1)

- Final Essay #4Document3 pagesFinal Essay #4Harry HandlersNo ratings yet

- Exam Roll - RAB ENG 200052, PG CC-3.2Document4 pagesExam Roll - RAB ENG 200052, PG CC-3.2Fahmida YasminNo ratings yet

- Kirby1991 - Corporeal HabitsDocument21 pagesKirby1991 - Corporeal HabitsLuciano ArévaloNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter-3Document36 pages09 Chapter-3yashica tomarNo ratings yet

- A History of Sex - Simone de BeauvoirDocument15 pagesA History of Sex - Simone de BeauvoirDaniel Felipe Gutiérrez ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- The Second Sex - DeRYADocument2 pagesThe Second Sex - DeRYAMuzaffer Derya NazlıpınarNo ratings yet

- It Is Important To NoteDocument22 pagesIt Is Important To NoteChristiancamilogilNo ratings yet

- The Handmaid's Tale and The Passion of New Eve's Critiques of Societal Attitudes Towards Women andDocument6 pagesThe Handmaid's Tale and The Passion of New Eve's Critiques of Societal Attitudes Towards Women andDerouiche MariemNo ratings yet

- Title of Popular Song by Eagles (1972) Foucault, Michel. (1976) (1998) - The History of Sexuality Vol. 1: The Will ToDocument17 pagesTitle of Popular Song by Eagles (1972) Foucault, Michel. (1976) (1998) - The History of Sexuality Vol. 1: The Will Toapi-14486402No ratings yet

- Amy Hollywood "Sensible Ecstasy" ReviewDocument6 pagesAmy Hollywood "Sensible Ecstasy" ReviewJack MitchellNo ratings yet

- Reclaiming Femme - Queer Women of Colour and Femme IdentityDocument7 pagesReclaiming Femme - Queer Women of Colour and Femme Identityrachel leeNo ratings yet

- Existentialism NotesDocument5 pagesExistentialism NotesDwight SargaNo ratings yet

- Writing-And Reading-The Body - Female Sexuality and Recent Feminist FictionDocument24 pagesWriting-And Reading-The Body - Female Sexuality and Recent Feminist FictionMosza DiánaNo ratings yet

- Simone de Beauvoire Al Treilea SexDocument11 pagesSimone de Beauvoire Al Treilea SexDana DanutzaNo ratings yet

- Feminist View On Sex and GenderDocument18 pagesFeminist View On Sex and GenderPeterA.MacabinguilNo ratings yet

- Woman's Self-Identification: Resistance and Reluctance Under Patriarchal Society Liu Hiu Lam 20608793Document4 pagesWoman's Self-Identification: Resistance and Reluctance Under Patriarchal Society Liu Hiu Lam 20608793guap froggyNo ratings yet

- Mrs. DallowayDocument33 pagesMrs. DallowaySheena C. OcutareNo ratings yet

- India's Approach To AsiaDocument538 pagesIndia's Approach To AsiaSingh JagdishNo ratings yet

- Karnataka Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes (Reservation of Seats in Educational Institutions and of Appointments or Posts in The Services Under The State) Act, 1994Document22 pagesKarnataka Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes (Reservation of Seats in Educational Institutions and of Appointments or Posts in The Services Under The State) Act, 1994Latest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Mindanao 2020 Peace and Development FrameworkDocument16 pagesMindanao 2020 Peace and Development FrameworkJun-Jun Putot PagoyNo ratings yet

- Seperation of Power UzairDocument15 pagesSeperation of Power UzairuzairNo ratings yet

- Political Science-IIIDocument14 pagesPolitical Science-IIISrishti AgrawalNo ratings yet

- TRUSTEES OF THE PLUMBERS LOCAL UNION NO. 1 WELFARE FUND, v. BASS PLUMBING & HEATING CORP. Et Al DocketDocument2 pagesTRUSTEES OF THE PLUMBERS LOCAL UNION NO. 1 WELFARE FUND, v. BASS PLUMBING & HEATING CORP. Et Al DocketACELitigationWatchNo ratings yet

- NHD Annotated BibliographyDocument14 pagesNHD Annotated Bibliographykylenguyen70% (1)

- Field of EconomicsDocument5 pagesField of EconomicsVinod JoshiNo ratings yet

- CompiledDocument8 pagesCompiledBrigette DomingoNo ratings yet

- British American Tobacco v. Camacho Case DigestDocument3 pagesBritish American Tobacco v. Camacho Case DigestMak Francisco100% (1)

- Expected Questions From February 2021 Current AffairsDocument27 pagesExpected Questions From February 2021 Current Affairsfathima rifkaNo ratings yet

- Activity (Group5)Document5 pagesActivity (Group5)Tricia Maxine DomingoNo ratings yet

- EN - EP Brochure Citizen VoicesDocument25 pagesEN - EP Brochure Citizen Voices1234567890albertoNo ratings yet

- Public Agenda 3-5-12Document19 pagesPublic Agenda 3-5-12daniel_goodman7884No ratings yet

- As If Consenting To HorrorDocument5 pagesAs If Consenting To HorrorNabeelShahzadNo ratings yet

- Executive Assistant Job Description (For Lisa Hall)Document3 pagesExecutive Assistant Job Description (For Lisa Hall)Teuku RickyNo ratings yet

- Printslip Token lDWH54JkLUqWB8gi2yTk8rDLRsLVWBbfHIJsAFCk&cnic 45206-6263441-1&roll Number 32194613Document3 pagesPrintslip Token lDWH54JkLUqWB8gi2yTk8rDLRsLVWBbfHIJsAFCk&cnic 45206-6263441-1&roll Number 32194613sh7881807No ratings yet

- A Brief History of The Israeli-Palestinian ConflictDocument18 pagesA Brief History of The Israeli-Palestinian ConflictKamizori100% (2)

- Workplace Conflict Resolution and Management: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleDocument25 pagesWorkplace Conflict Resolution and Management: Click To Edit Master Subtitle Stylefpokoo_aikinsNo ratings yet

- Certification and ClearanceDocument6 pagesCertification and ClearanceElmarNo ratings yet

- English 13-10-2020Document3 pagesEnglish 13-10-2020Aakash BerliaNo ratings yet

- Indian Down Under E Paper Jan - Feb 2012Document65 pagesIndian Down Under E Paper Jan - Feb 2012indiandownunderNo ratings yet

- THE UNION OF INDIA Vs K LAKSHMINARAYANANDocument156 pagesTHE UNION OF INDIA Vs K LAKSHMINARAYANANMeghan PaulNo ratings yet

- Jaramilla - v. - Commission - On - Elections20210424-12-1gemsflDocument7 pagesJaramilla - v. - Commission - On - Elections20210424-12-1gemsflMary Ann TanNo ratings yet

- Executive Women and The Myth of Having It AllDocument13 pagesExecutive Women and The Myth of Having It AllGargi TiwariNo ratings yet

- Tabasa v. CA 500 SCRA 9Document2 pagesTabasa v. CA 500 SCRA 9Estee XoohNo ratings yet

- Growing Up and Growing Older: Feminism As A Context For Women'S LivesDocument9 pagesGrowing Up and Growing Older: Feminism As A Context For Women'S LivesFernanda SoriaNo ratings yet