Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brainerd Reyna 2002 Fuzzy Trace Theory and False Memory

Brainerd Reyna 2002 Fuzzy Trace Theory and False Memory

Uploaded by

eliseazazelCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Confabulation and MisrememberingDocument13 pagesConfabulation and MisrememberingdanielahaisanNo ratings yet

- Applied Computational Economics and Finance PDFDocument521 pagesApplied Computational Economics and Finance PDFAidan HolwerdaNo ratings yet

- Astm A500Document6 pagesAstm A500notsofar100% (4)

- Sculpture 122 ArticleDocument3 pagesSculpture 122 ArticleGusti Ragil AprilianoNo ratings yet

- Neural Basis of ConsciousnessDocument13 pagesNeural Basis of ConsciousnessAlejandro León100% (1)

- False Memory Syndrome Research PaperDocument5 pagesFalse Memory Syndrome Research Papergxopkbxgf100% (3)

- False Memory Research PaperDocument8 pagesFalse Memory Research Paperafedyvlyj100% (1)

- Hoffman - Conscious Realism and The Mind Body ProblemDocument24 pagesHoffman - Conscious Realism and The Mind Body ProblemejonysNo ratings yet

- Blanco 2017 Cognitive Bias EncyclopediaDocument8 pagesBlanco 2017 Cognitive Bias Encyclopedia777 777No ratings yet

- What Science Tells Us About False and Repressed MemoriesDocument7 pagesWhat Science Tells Us About False and Repressed MemoriesKami67% (3)

- Knowing Who'S New: From Deja To Jamais Vu: Memory, and Cognition, II, 501-518Document2 pagesKnowing Who'S New: From Deja To Jamais Vu: Memory, and Cognition, II, 501-518abrahamzapruderNo ratings yet

- Hippocampal Maturation Drives Memory From Generalization To Specificity, Keresztes2018Document11 pagesHippocampal Maturation Drives Memory From Generalization To Specificity, Keresztes2018Ana Paula CastroNo ratings yet

- Naturalizing Consciousness A Theoretical Framework Edelman PNAS 2003Document5 pagesNaturalizing Consciousness A Theoretical Framework Edelman PNAS 2003hamletquiron100% (1)

- Rossano 2003-Evolution of ConsciousnessDocument30 pagesRossano 2003-Evolution of ConsciousnessМаја КокановићNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Architecture, Concepts, and Introspection: An Information-Theoretic Solution To The Problem of Phenomenal ConsciousnessDocument59 pagesCognitive Architecture, Concepts, and Introspection: An Information-Theoretic Solution To The Problem of Phenomenal ConsciousnessMarko RadovicNo ratings yet

- Meadhbh Foster@ucdconnect IeDocument24 pagesMeadhbh Foster@ucdconnect IeNondoda ChagiNo ratings yet

- Metcalfe 2008 MetamemoryDocument14 pagesMetcalfe 2008 MetamemoryhoorieNo ratings yet

- (Ebook) (Philosophy of Mind) Jerry A. Fodor - A Theory of Content and Other Essays-Chap8Document26 pages(Ebook) (Philosophy of Mind) Jerry A. Fodor - A Theory of Content and Other Essays-Chap8Sebastian ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Proust2007 Article MetacognitionAndMetarepresentaDocument25 pagesProust2007 Article MetacognitionAndMetarepresentavbaumhoffNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Awareness A Framework For Integrating Science Philosophy and MetaphysicsDocument20 pagesFundamental Awareness A Framework For Integrating Science Philosophy and MetaphysicsAjit GhoshNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On False MemoryDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On False Memorygihodatodev2100% (1)

- Review Memory Consolidation in Sleep: Dream or Reality: 2004 by Cell PressDocument14 pagesReview Memory Consolidation in Sleep: Dream or Reality: 2004 by Cell PressLeFührer Zabdiel PazaranNo ratings yet

- Nagel IntuitionsDocument33 pagesNagel IntuitionsAlejandroNo ratings yet

- Implicit Memory and MetacognitionDocument22 pagesImplicit Memory and MetacognitionMonica SanduleanuNo ratings yet

- The Somatic Marker Hypothesis and The Possible Functions of The Prefrontal CortexDocument9 pagesThe Somatic Marker Hypothesis and The Possible Functions of The Prefrontal CortexMauricio Vega MontoyaNo ratings yet

- MARGINS of REALITY The Role of Consciousness in The Physical World (Jahn, Robert G.dunne, Brenda J)Document425 pagesMARGINS of REALITY The Role of Consciousness in The Physical World (Jahn, Robert G.dunne, Brenda J)guilherme gomesNo ratings yet

- NeuroscientistDocument5 pagesNeuroscientistMouhamadou Moukhtar SarrNo ratings yet

- Pseudocontingencies: An Integrative Account of An Intriguing Cognitive IllusionDocument20 pagesPseudocontingencies: An Integrative Account of An Intriguing Cognitive IllusionYo MeNo ratings yet

- The Getting of Wisdom: Theory of Mind in Old Age: Francesca G. E. Happe Ellen WinnerDocument5 pagesThe Getting of Wisdom: Theory of Mind in Old Age: Francesca G. E. Happe Ellen WinnercursuriposdruNo ratings yet

- WestraCarruthers TheoryofmindDocument8 pagesWestraCarruthers Theoryofmindimroah339No ratings yet

- Art Cleeremans2011 TheRadicalPlasticityThesisDocument12 pagesArt Cleeremans2011 TheRadicalPlasticityThesisLuis Escobar L.-DellamaryNo ratings yet

- TOK Final EssayDocument7 pagesTOK Final EssayManishNo ratings yet

- 4 Response To CommentariesDocument5 pages4 Response To CommentariesMaximiliano PortilloNo ratings yet

- Dienes and Seth 2022 Conscious and Unconscious Mental StatesDocument39 pagesDienes and Seth 2022 Conscious and Unconscious Mental StatesMehwish LodhiNo ratings yet

- Hindsight Foresight: The Effect of Outcome Knowledge On Judgment Under UncertaintyDocument9 pagesHindsight Foresight: The Effect of Outcome Knowledge On Judgment Under Uncertaintyujangketul62No ratings yet

- Psyc - With Reference To Relevant Research Studies, To What Extent Is One Cognitive Process ReliableDocument2 pagesPsyc - With Reference To Relevant Research Studies, To What Extent Is One Cognitive Process Reliableloveis1020No ratings yet

- False Memory Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesFalse Memory Literature Reviewfeiaozukg100% (1)

- Logic and Biology Emotional Inference AnDocument30 pagesLogic and Biology Emotional Inference AnItzamna FuentesNo ratings yet

- Leslie 1987b Psychological ReviewDocument15 pagesLeslie 1987b Psychological ReviewanaNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Fmri Detection of False Eyewitness Memory 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: Fmri Detection of False Eyewitness Memory 1api-534201968No ratings yet

- Declarative y No Declarative Memory SystemsDocument14 pagesDeclarative y No Declarative Memory SystemsLuciano Dante MianiNo ratings yet

- Thiemo Breyer (Eds.) - Epistemological Dimensions of Evolutionary Psychology-Springer-Verlag New York (2015)Document248 pagesThiemo Breyer (Eds.) - Epistemological Dimensions of Evolutionary Psychology-Springer-Verlag New York (2015)LandoGuillénChávezNo ratings yet

- Paper Illusion of Explanatory DepthDocument47 pagesPaper Illusion of Explanatory DepthkolantreasNo ratings yet

- 1986 - Pribram - The Cognitive Revolution and Mind-Brain IssuesDocument15 pages1986 - Pribram - The Cognitive Revolution and Mind-Brain Issuesandres ceaNo ratings yet

- Varela, Francisco - The View From WithinDocument17 pagesVarela, Francisco - The View From Withinapi-3719401No ratings yet

- Phenomenology and Embodied ActionDocument16 pagesPhenomenology and Embodied ActionAjit GhoshNo ratings yet

- Unified Theories of CognitionDocument10 pagesUnified Theories of Cognitionvirtualinformatica159357No ratings yet

- Science & Society: Neuroethics Beyond GenethicsDocument5 pagesScience & Society: Neuroethics Beyond Genethicseduardoazevedo_ccciNo ratings yet

- Francisco J. Varela & J. Shears-First Person What, Why, HowDocument14 pagesFrancisco J. Varela & J. Shears-First Person What, Why, HowCiencias Cognoscitivas Costa RicaNo ratings yet

- Quine 1969Document13 pagesQuine 1969Hans OrangenbaumNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Journal For Psychoanalysis and The NeurosciencesDocument12 pagesNeuropsychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Journal For Psychoanalysis and The NeurosciencesPierreNo ratings yet

- What Is An "Explanation" of BehaviorDocument13 pagesWhat Is An "Explanation" of BehaviorDebasish SahooNo ratings yet

- How To Read MindsDocument18 pagesHow To Read MindsFahrizon IlmarNo ratings yet

- Hindsight Foresight The Effect of Outcome KnowledgDocument11 pagesHindsight Foresight The Effect of Outcome KnowledgAntonioNo ratings yet

- Taylor 2000Document36 pagesTaylor 2000MoqaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and NeuroscienceDocument19 pagesPhilosophy and NeuroscienceRandy AlzateNo ratings yet

- Impulsividad BarratDocument18 pagesImpulsividad BarratadrianaNo ratings yet

- How People Make Decisions That Involve Risk: A Dual-Processes ApproachDocument7 pagesHow People Make Decisions That Involve Risk: A Dual-Processes Approachjehu325No ratings yet

- The Brain has a Mind of its Own: Attachment, Neurobiology, and the New Science of PsychotherapyFrom EverandThe Brain has a Mind of its Own: Attachment, Neurobiology, and the New Science of PsychotherapyNo ratings yet

- Detection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationFrom EverandDetection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationArthur MacNeill Horton, Jr.No ratings yet

- Adolescent Suicide and Self-Injury: Mentalizing Theory and TreatmentFrom EverandAdolescent Suicide and Self-Injury: Mentalizing Theory and TreatmentLaurel L. WilliamsNo ratings yet

- 10th Reflection and Refraction of Light Cbse Test Paper Solved-4Document4 pages10th Reflection and Refraction of Light Cbse Test Paper Solved-4ashokNo ratings yet

- Ch-03 Vectors: Lect-01Document20 pagesCh-03 Vectors: Lect-01Mohit TewatiaNo ratings yet

- Ic60 RCBODocument1 pageIc60 RCBOEng.Panelindo masNo ratings yet

- Literature Review in Research ProposalDocument5 pagesLiterature Review in Research Proposalmzgxwevkg100% (1)

- Dialogue Questionnaire-3rd SessionDocument3 pagesDialogue Questionnaire-3rd SessionMiguel HernandezNo ratings yet

- AP at RHHS 2016Document13 pagesAP at RHHS 2016Ryan YuNo ratings yet

- Fcaw Wps-001a PDFDocument3 pagesFcaw Wps-001a PDFirfan bari100% (1)

- Performing Cold Backup On Oracle 10gDocument10 pagesPerforming Cold Backup On Oracle 10gapi-250287051No ratings yet

- Unidrive M400: Fast Set-Up and Diagnostics With Real-Text Display, Integrated PLC and Safety InputsDocument16 pagesUnidrive M400: Fast Set-Up and Diagnostics With Real-Text Display, Integrated PLC and Safety InputsJunior enriquez cabezudoNo ratings yet

- Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Postsynthetic ModificationDocument60 pagesMetal-Organic Frameworks and Their Postsynthetic ModificationDean HidayatNo ratings yet

- Pipe Drafting and DesignDocument38 pagesPipe Drafting and DesignMohammad TaherNo ratings yet

- Online Class Activity Work No1-Ged0011Document2 pagesOnline Class Activity Work No1-Ged0011Khristian SorianoNo ratings yet

- Technical Specification For Ground Wire OPGWDocument28 pagesTechnical Specification For Ground Wire OPGWtanujaayer100% (1)

- Contermporary Arts Week 4Document3 pagesContermporary Arts Week 4Ira Jane Caballero0% (1)

- Self-Assessment Questions For Module 12 Project Procurement ManagementDocument12 pagesSelf-Assessment Questions For Module 12 Project Procurement ManagementLawal Idris AdesholaNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To LEX and YACC: SYSC-3101 1Document19 pagesAn Introduction To LEX and YACC: SYSC-3101 1Sruti SukumarNo ratings yet

- Tissues 1.Document2 pagesTissues 1.Adeaga ElizabethNo ratings yet

- Health8 - q1 - wk8 FinalDocument9 pagesHealth8 - q1 - wk8 FinalMary Ann MalaguitNo ratings yet

- Principles of Inheritance and Variation Class 12 Notes Biology - myCBSEguideDocument15 pagesPrinciples of Inheritance and Variation Class 12 Notes Biology - myCBSEguideShireen SuhailNo ratings yet

- Prashant Jain PJ Sir COMPLETE MATHS PYQ PDF PYQ's ExportDocument20 pagesPrashant Jain PJ Sir COMPLETE MATHS PYQ PDF PYQ's ExportSourabh Singh100% (1)

- User Manual Canon IXUS 165Document117 pagesUser Manual Canon IXUS 165zilltrinnNo ratings yet

- Getting StartedDocument17 pagesGetting StartedManuel Jesus Vera Duran100% (1)

- HP 15-CS 1016ur Quanta G7BD DAG7BDMB8F0 Rev 1ADocument49 pagesHP 15-CS 1016ur Quanta G7BD DAG7BDMB8F0 Rev 1AJuan Carlos Huaman HuertaNo ratings yet

- Ibs Ipoh Main, Jsis 1 30/06/20Document6 pagesIbs Ipoh Main, Jsis 1 30/06/20Muhdalihelmy MdYaakobNo ratings yet

- Maruti SuzukiDocument30 pagesMaruti SuzukiChaitanya KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Getting Started With MDM: 9 Steps ToDocument16 pagesGetting Started With MDM: 9 Steps ToSantiago GivNo ratings yet

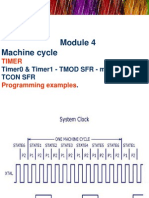

- Iv TimersDocument48 pagesIv TimersanishthNo ratings yet

Brainerd Reyna 2002 Fuzzy Trace Theory and False Memory

Brainerd Reyna 2002 Fuzzy Trace Theory and False Memory

Uploaded by

eliseazazelOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brainerd Reyna 2002 Fuzzy Trace Theory and False Memory

Brainerd Reyna 2002 Fuzzy Trace Theory and False Memory

Uploaded by

eliseazazelCopyright:

Available Formats

164 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 5, OCTOBER 2002

Fuzzy-Trace Theory and False Memory between adequacy and parsimony

such that increased adequacy can

C.J. Brainerd1 and V.F. Reyna be purchased in the coin of re-

duced parsimony, which means

Department of Surgery (C.J.B., V.F.R.), Department of Special Education, Rehabilita-

that successful theories achieve a

tion, and School Psychology (C.J.B.), and Department of Medicine (V.F.R.), Univer-

sity of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona balance between empirical breadth

and assumptive frugality.

Thus, explanatory progress con-

sists of improving adequacy, parsi-

ground facts—getting the gist— mony, or both. In false-memory re-

Abstract search, the most pressing problem

A key problem confronting and that, in contrast, remembering

their exact content is not usually at the moment is to improve ade-

theories of false memory is that quacy. The reason is apparent in

false-memory phenomena are crucial (for a review, see Reyna &

Brainerd, 1995). A surprising find- Table 1, which exhibits 10 false-

so diverse: Some are character- memory effects, arranged in ap-

istic of controlled laboratory ing was that reasoning accuracy

was largely independent of mem- proximate historical order, each of

tasks, others of everyday life; which has an associated literature.

some occur for traumatic ory accuracy.

Research on human false memo- The diversity of these phenomena

events with legal conse- is great: Some are produced by

quences, others for innocuous ries intensified during the mid-

1990s, and since then, FTT’s as- controlled laboratory tasks, others

events; some are characteristic by real-world experiences; some

of one developmental level, sumptions have been used to gain

leverage on such phenomena. The involve innocuous events, others

others of another developmen- emotionally charged events with

tal level. Fuzzy-trace theory ex- theory’s explanations and predic-

tions of false-memory effects are legal consequences; some are char-

plains false memories via a acteristic of adults, others of chil-

small set of principles that im- the topics of the present article.

First, we sketch general criteria for dren. Therefore, although it is very

plement a single representa- desirable to be able to explain, say,

tional distinction. Those a successful theory of false mem-

ory. Next, we summarize princi- false memories that arise when un-

principles generate new pre- dergraduates study word lists (Ex-

dictions, some of which are ples that FTT’s account of false

memory relies upon. Last, we de- amples 3 and 4), the compass of a

counterintuitive. successful theory will have to be

scribe a series of novel predictions

about false memory that fall out of far broader, so that the theory will

Keywords be applicable to topics as varied as

fuzzy-trace theory; false mem- those principles.

comprehension of narratives, psy-

ory; explanation; prediction chotherapy, forensic interviews,

and human development.

CONSTRAINTS ON THEORIES Although the diversity of the

Fuzzy-trace theory (FTT) is not OF FALSE MEMORY phenomena in Table 1 seems

so much a model of false memory daunting, there is a common

as a model of the interface between Successful theories perform two thread: Falsely remembered infor-

memory and higher reasoning pro- principal tasks, explanation and mation is consistent with the gist of

cesses. In origin, it was a response prediction. We postpone the issue subjects’ experience (e.g., an un-

to findings about how the validity of prediction until later. Explana- dergraduate falsely remembers

of solutions to reasoning problems tion, telling why the data are as reading doctor after reading several

(e.g., decision making, deductive they are, has two aspects, ade- medical words, a high school stu-

inference, quantitative judgment) quacy and parsimony. Adequacy dent falsely remembers hearing the

is related to memory for back- refers to explanatory breadth: statement The coffee is hotter than the

ground facts that determine which Other things being equal, explain- cocoa after hearing The coffee is hot-

solutions are valid (e.g., the pre- ing more facts is preferable to ex- ter than the tea and The tea is hotter

mises in deductive-inference prob- plaining fewer. Parsimony refers to than the cocoa, a child-abuse victim

lems). Contrary to then-current in- explanatory frugality: Other things falsely remembers being touched

formation processing models, the being equal, explaining known facts on the right breast rather than cor-

data suggested that the key mem- with fewer assumptions is prefera- rectly remembering being touched

ory support for reasoning lies in ble to explaining them with more on the left breast, an adult crime

having the right take on the back- assumptions. There is a trade-off witness who knows that the prime

Published by Blackwell Publishing Inc.

CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE 165

(meanings, relations, patterns) that

Table 1. Ten demonstrations of false memory have been retrieved as a result of

encoding items’ surface forms. Al-

Example Phenomenon

though it was once supposed that

1 After children observe a series of objects that ascend in meaning content is extracted from

magnitude (e.g., a series of rods that increase in length), their previously stored verbatim memo-

recall of the objects’ appearance (e.g., the rods’ lengths) is ries, it is now known that meaning

distorted upward.

2 Over repeated retellings, recall of the details of folk stories is processing begins as early as 20 to

distorted in ways that preserve their themes. 30 ms after the onset of a stimulus,

3 After studying a short word list (e.g., nurse, hospital, sick, cure, well before the processing of the

ill, . . .) whose members share a familiar semantic associate item’s surface form is completed.

(doctor), subjects falsely recall (and recognize) the associate Gist traces can be stored at various

when asked to recall (or recognize) only list words.

4 After studying a long word list containing a few exemplars of a levels of specificity (e.g., reading

familiar semantic concept (e.g., elm, maple, pine), subjects spaniel may cause the concepts

falsely recognize unpresented exemplars of that concept “hunting dog,” “farm animal,” and

(e.g., oak). “pet” to be stored).

5 After reading a narrative, subjects falsely recognize

unpresented sentences that connect the meaning of several

narrative sentences.

6 Witnesses to crimes falsely recognize events that are consistent Principle 2: Dissociated Retrieval

with the nature of the crimes, especially following of Verbatim and Gist Traces

suggestion.

7 Witnesses to crimes falsely recognize faces of innocent people Memory performance is based

that have the same gender and ethnicity as police suspects.

8 During interviews that focus on possible sexual abuse, children on the retrieval of both verbatim

falsely recall incidents of abuse. and gist traces. The mix of verba-

9 During psychotherapy, clients who believe that they may be tim and gist retrieval, which deter-

victims of abuse falsely recall being sexually abused as mines the level of false memory for

children. gist-consistent information, turns

10 After reading metaphorical prose, subjects falsely recognize

unstated metaphors that are consistent with the stated on factors such as (a) retrieval cues,

metaphors. (b) the relative accessibility of ver-

batim and gist memories, and (c)

forgetting. Concerning retrieval

cues, items that were experienced

(e.g., spaniel ) are better retrieval

police suspect is a Hispanic male most of the explanatory load is cues for verbatim traces than items

identifies a photograph of an inno- borne by the following five princi- that were not, and nonexperienced

cent Hispanic male). It is this fre- ples, all of which implement a sin- items that preserve the meaning of

quent feature of false-memory phe- gle representational distinction— experience (e.g., collie) are usually

nomena—that otherwise disparate namely, the distinction between ver- better retrieval cues for gist traces

falsely remembered objects and batim and gist traces of experience. than for verbatim traces. However,

events fit with the gist of experi- retrieval can be slanted in one di-

ence—that allows them to be ex- rection or the other by instructions

plained with a common set of prin- Principle 1: Parallel Storage of that tell subjects how to use re-

ciples. Verbatim and Gist Traces trieval cues. Concerning relative

accessibility, verbatim retrieval is

Subjects process the surface favored when verbatim traces are

form and meaning content of expe- strong relative to gist traces (as

EXPLANATORY PRINCIPLES rience in parallel, storing dissoci- when the same item, e.g., spaniel,

ated representations of the former has been repeatedly presented),

It might be thought, considering (verbatim traces) and the latter and gist retrieval is favored when

the diversity of false-memory phe- (gist traces). Verbatim traces are gist traces are strong relative to

nomena, that a comprehensive the- episodically instantiated represen- verbatim traces (as when different

ory would have to be quite com- tations of the surface forms of ex- exemplars of a meaning are pre-

plex. Research has shown, however, perienced items, including contex- sented but no exemplar is re-

that this need not be the case. In tual cues, and gist traces are peated, e.g., hound, poodle, retriever,

FTT’s account of false memory, episodic interpretations of concepts spaniel ). Concerning forgetting, a

Copyright © 2002 American Psychological Society

166 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 5, OCTOBER 2002

familiar finding is that over time, the ability to connect meaning structivism) or a common retrieval

memory for surface form declines across different items improves. process (source monitoring).

more rapidly than memory for These abilities decline during late

meaning, suggesting that verbatim adulthood, but declines are more

traces become inaccessible more marked for verbatim memory. Dissociations and Associations

rapidly than gist. Between True and

Principle 5: Verbatim and Gist False Memories

Processing Both Cause

Principle 3: Dual-Opponent Vivid Remembering In memory research, two phe-

Processes2 in False Memory nomena are said to be positively as-

Retrieval of verbatim traces sup- sociated if higher frequencies of

Verbatim and gist retrieval both ports a vivid form of remembering, one produce higher frequencies of

support true memory for experi- sometimes called recollection, in the other and lower frequencies of one

enced items, either because the cor- which subjects consciously reexpe- produce lower frequencies of the

responding experiences are speci- rience items’ occurrence in specific other. Otherwise, the phenomena

fically recollected (verbatim retrieval) contexts. Retrieval of gist traces are said to be dissociated. Positive

or because items’ meanings are fa- usually supports a more generic associations between true and false

miliar. However, verbatim and gist form of remembering, sometimes memories are basal predictions of

retrieval have opposite effects on called familiarity, in which nonex- one-process approaches (Reyna &

false memory for items that pre- perienced items are perceived to Brainerd, 1995). In contrast, FTT

serve the meaning of experience (e.g., resemble experienced items but predicts that true-false dissocia-

collie when spaniel was presented). their occurrence is not explicitly re- tions will be observed under cer-

Gist retrieval supports false mem- called. However, when gist traces tain conditions, and associations

ory because items’ meanings seem are especially strong, they can sup- will be observed under others.

familiar, but verbatim retrieval sup- port high levels of phantom recol- These predictions fall out of Princi-

presses false memory by neutraliz- lective experience for certain types ples 1 through 3, according to

ing meaning familiarity, either at of nonexperienced items—namely, which subjects retrieve dissociated

the level of individual items (“No, I items that are good cues for the gist verbatim and gist traces, with true

distinctly remember hearing span- of experience. responses being supported by both

iel, not collie”) or at the level of gen- kinds of traces and false responses

eral cognitive strategies (”I won’t being supported by gist traces

accept any word unless I have an only. Thus, dissociations should be

auditory image of its presenta- PREDICTIONS ABOUT observed in situations that foster

tion”). An important exception to this FALSE MEMORY reliance on verbatim traces as the

rule occurs when false items have basis for true responses (e.g., when

been presented as suggestions The other task of a theory is to memory for memorable material is

(e.g., Example 6 in Table 1). In such forecast new phenomena. Some tested immediately after its presen-

circumstances, both gist retrieval predictions are more probative tation), so that true and false re-

and retrieval of verbatim traces of than others, and the most interest- sponses will be based on different

suggestions support false memory, ing ones are those that seem coun- representations. Data confirming

while retrieval of verbatim traces of terintuitive, either from the per- this prediction have been reported

original experiences suppresses false spective of currently accepted (Reyna & Kiernan, 1994, Experiment

memory.3 theories or from the perspective of 1, and 1995, Experiment 1; Roediger,

common sense. Predictions of this Watson, McDermott, & Gallo, 2001).

sort have been emphasized in ap- In contrast, positive associations

Principle 4: Developmental plications of FTT to false memory. between true and false memory

Variability These predictions have often been should be observed in situations

contrasted with those of one-pro- that foster reliance on gist traces as

Acquisition, retention, and re- cess approaches, such as construc- the basis for true responses (e.g.,

trieval of both verbatim and gist tivism (Bransford & Franks, 1971) when memory testing is delayed

memories improve as the child de- or the source-monitoring frame- for several days and subjects are

velops into an adult. Gist memory work (Johnson, Hashtroudi, & instructed to rely on the meaning

improves during development be- Lindsay, 1993), which assume that content of experience), so that true

cause both the ability to process the true and false memories are based and false responses will be based

meaning of individual items and on a common memory code (con- on the same representations. Con-

Published by Blackwell Publishing Inc.

CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE 167

firmatory data have been reported children, it is acknowledged that tion if young children are able to

for this prediction as well (Reyna & false memories can be implanted store and retrieve the relevant gist

Kiernan, 1994, Experiment 2, and by investigative interviews that traces; in this case, false memories

1995, Experiment 2). suggest to witnesses events that will decrease with developmental

support charges against defen- improvements in the ability of ver-

False Persistence dants. However, it is also assumed batim retrieval to suppress false-

that as long as interviewers do not memory responses. By the same

Common sense suggests that offer suggestions and merely pro- principle, false memories will vio-

true memories will be far more sta- vide recall prompts (e.g., “Tell me late the generalization if young

ble than false ones because the about the robber.”) and recognition children are unable to store or re-

events that figure in the former probes (e.g., “Did the robber have a trieve the relevant gist traces, so

were actually experienced, gun in his hand?”), such interviews that false memories will increase

whereas those that figure in the lat- do not elevate levels of false report- with developmental improvements

ter were not. This idea occupies a ing during subsequent interviews in these abilities.

prominent position in the law, and sworn testimony and that, in- An example is provided by a

where it is known as the consis- deed, their principal effect is to in- simple ability that is surprisingly

tency principle of testimonial cred- oculate true memories against for- slow to develop in children—

ibility: Events that witnesses report getting. However, FTT predicts, on namely, the formation of gist mem-

consistently over time are regarded the basis of Principles 2 and 3, that ories that involve spontaneously

as more likely to be true than neutral, nonsuggestive memory connecting meaning across several

events that they report inconsis- questions can substantially elevate distinct events. (Examples 3 and 4

tently. However, FTT predicts, on later false memory when subjects in Table 1, which involve the gist

the basis of Principles 2 and 3, that respond to the questions by re- memories “a bunch of medical

false memories can be highly per- trieving gist traces. False-memory words” and “a bunch of tree

sistent and that, surprisingly, they levels ought to rise under such con- names,” are illustrative.) Because

can be more persistent than true ditions because subjects become this ability develops slowly, FTT

memories under certain condi- practiced at processing the very predicts that false-memory re-

tions. Persistence of false memories types of representations that sup- sponses that depend on connecting

is predicted because they arise port false-memory responses. Ex- meaning across distinct events will

from particularly stable memory periments have shown steady in- also develop slowly. Confirmatory

representations—namely, gist creases in false-memory responses data have been reported (Brainerd,

traces. The conditions under which over a series of nonsuggestive rec- Reyna, & Forrest, in press).

false memories are expected to be ognition or recall tests (Brainerd &

more persistent than true memo- Reyna, 1996; Payne et al., 1996). Phantom Recollection

ries are ones in which the events in

the false memories are especially FTT predicts (Principle 5) that

good retrieval cues for strong gist Developmental Increases in certain false memories will be ac-

memories (e.g., Examples 3 and 4 False Memory companied by high levels of phan-

in Table 1), and initial true-mem- tom recollection (illusory vivid

ory responses are based on less sta- A familiar generalization, in the mental reinstatement of events’

ble verbatim traces. Several experi- law as well as the psychological lit- “occurrence”). Confirmatory data

ments have shown high levels of erature, is that children, particu- have been reported for tasks like

false-memory persistence, includ- larly young children, are especially those referred to in Examples 3

ing greater persistence of false than prone to false memories. Although through 5 in Table 1 (e.g., Payne et

true memories (Brainerd, Reyna, & there is much empirical support for al., 1996). A further prediction that

Brandse, 1995; Payne, Elie, Black- this generalization (for a review, follows from Principle 5 is that

well, & Neuschatz, 1996; Toglia, see Ceci & Bruck, 1993), FTT pre- phantom recollection should be

Neuschatz, & Goodwin, 1999). dicts, on the basis of Principles 3 dissociated from true recollection

and 4, that only certain false mem- (i.e., vivid mental experience that

Creation of False Memories by ories conform to this generalization accompanies true-memory re-

Mere Testing and that, further, some important sponses) by manipulations that se-

forms of adult false memory will lectively affect gist and verbatim

In the law, particularly in eye- be largely absent in children. Ac- memory, respectively. Confirma-

witness-identification cases and cases cording to Principle 4, false memo- tory data have also been reported

in which evidence is provided by ries will conform to this generaliza- for this prediction (Brainerd,

Copyright © 2002 American Psychological Society

168 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 5, OCTOBER 2002

Wright, Reyna, & Mojardin, 2001;

Payne et al., 1996).

Repetition Has Different Effects

on True and False Memory

Repeated presentation of target

material (i.e., the event to be re-

membered) is one of the oldest ma-

nipulations in memory research.

By Principles 2 and 3, repetition

should increase false-memory re-

sponses if gist traces are not yet

available, but should decrease

false-memory responses if gist

traces are already available (by

strengthening the verbatim traces

that can be used to suppress such

responses; Reyna & Lloyd, 1997).

Because gist traces are more stable Fig. 1. False recognition (false alarm probability) of meaning-preserving items as a

function of list repetition in two experiments by Seamon et al. (2002). Example 3 in

than verbatim traces, repetition has Table 1 illustrates the task used. Target lists were presented either 0, 1, 5, or 10 times

disproportionate effects on verba- (Experiment 1) or 0, 1, 5, or 25 times (Experiment 2).

tim traces once gist traces have

been stored. Seamon and his asso-

ciates (e.g., Seamon et al., 2002)

ing surface overlap ought to have diversity of these phenomena not-

have proposed that with standard

two opposing effects. On the one withstanding, a small set of princi-

experimental procedures for pre-

hand, high surface resemblance be- ples that implement a core repre-

senting stimuli, the differential ef-

tween true and false items should sentational distinction has proved

fects of repetition on verbatim and

make it more difficult to discrimi- useful in explaining false memory

gist traces should lead to an in-

nate the two when the latter are and generating new predictions

verted-U relation between repeti-

presented on memory tests, thereby about it. False-memory research is

tion and false-memory responses—

increasing false responding. On the still in its infancy, however, and

that is, such responses should in-

other hand, because verbatim theoretical principles could change

crease with initial repetitions but

traces are representations of sur- considerably down the road.

then decrease with subsequent rep-

face information, increasing the

etitions as verbatim traces are

surface resemblance between true Recommended Reading

strengthened. Experiments con-

and false items should make the

ducted by Seamon et al. (2002) con- Brainerd, C.J., & Reyna, V.F. (2001).

latter better retrieval cues for ver-

firmed this prediction (see Fig. 1). Fuzzy-trace theory: Dual-pro-

batim traces of the former, thereby

cesses in reasoning, memory, and

decreasing false responding. Find- cognitive neuroscience. Advances

Similarity Can Be Distinctive ings that various surface-similarity in Child Development and Behavior,

manipulations either failed to in- 28, 49–100.

A seemingly self-evident claim crease or decreased false respond- Koriat, A., Goldsmith, M., & Pansky,

A. (2000). Toward a psychology of

about false-memory responses is ing are consistent with this predic-

memory accuracy. Annual Review

that they will increase as their simi- tion (see the review by Reyna & of Psychology, 51, 481–538.

larity to experienced material in- Lloyd, 1997). Schacter, D.L., Norman, K.A., &

creases (e.g., for Example 4 in Table Koutstaal, W. (1998). The cogni-

1, oak will produce more false rec- tive neuroscience of constructive

memory. Annual Review of Psychol-

ognition than, say, fern). However,

CONCLUSION ogy, 51, 289–318.

according to FTT, this relation

should hold consistently for mean-

ing overlap but not for surface FTT has been applied to false Acknowledgments— This research was

overlap (Reyna & Lloyd, 1997). This memories in a range of laboratory supported by a National Science Founda-

tion grant (SBR-9730143), by National In-

prediction follows because increas- tasks and real-world situations. The

Published by Blackwell Publishing Inc.

CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE 169

stitutes of Health grants (NIH31620 and References Reyna, V.F., & Brainerd, C.J. (1995). Fuzzy-trace

theory: An interim synthesis. Learning and Indi-

P50AT00008), and by a Schering Plough/ vidual Differences, 7, 1–75.

Brainerd, C.J., & Reyna, V.F. (1996). Mere memory

Integrated Therapeutics Group grant.

testing creates false memories in children. De- Reyna, V.F., & Kiernan, B. (1994). The develop-

velopmental Psychology, 32, 467–476. ment of gist versus verbatim memory in sen-

Brainerd, C.J., Reyna, V.F., & Brandse, E. (1995). tence recognition: Effects of lexical familiarity,

Are children’s false memories more persistent semantic content, encoding instructions, and

than their true memories? Psychological Science, retention interval. Developmental Psychology,

Notes 6, 359–364. 30, 178–191.

Brainerd, C.J., Reyna, V.F., & Forrest, T.J. (in

1. Address correspondence to C.J. press). Are young children susceptible to the Reyna, V.F., & Kiernan, B. (1995). Children’s mem-

false-memory illusion? Child Development. ory and interpretation of psychological meta-

Brainerd, Departments of Surgery and phors. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity, 10, 309–

Special Education, Rehabilitation, and Brainerd, C.J., Wright, R., Reyna, V.F., & Mojardin,

331.

A.H. (2001). Conjoint recognition and phan-

School Psychology, University of Ari- tom recollection. Journal of Experimental Psy-

zona, Tucson, AZ 85721; e-mail: Reyna, V.F., & Lloyd, F. (1997). Theories of false

chology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 27, memory in children and adults. Learning and

brainerd@u.arizona.edu. 307–327. Individual Differences, 9, 95–123.

2. Dual-opponent processes means Bransford, J.D., & Franks, J.J. (1971). The abstrac-

that two distinct processes are in- tion of linguistic ideas. Cognitive Psychology, 3, Roediger, H.L., III, Watson, J.M., McDermott, K.B.,

193–209. & Gallo, D.A. (2001). Factors that determine

volved in false memory, but they have false recall: A multiple regression analysis.

Ceci, S.J., & Bruck, M. (1993). Suggestibility of the

opposite effects on observed levels of child witness: A historical review and synthe- Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 8, 385–405.

false-memory responses. sis. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 403–439.

3. In the interest of brevity, we ig- Seamon, J.G., Luo, C.R., Schwartz, M.A., Jones,

Johnson, M.K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D.S. K.J., Lee, D.M., & Jones, S.J. (2002). Repetition

nore this special case, restricting our at- (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulle- can have similar and different effects on accu-

tention to the standard situation in tin, 114, 3–28. rate and false recognition. Journal of Memory

which verbatim traces that support Payne, D.G., Elie, C.J., Blackwell, J.M., & Neu- and Language, 46, 323–340.

schatz, J.S. (1996). Memory illusions: Recalling,

false-memory responses are not avail- recognizing, and recollecting events that never Toglia, M.P., Neuschatz, J.S., & Goodwin, K.A.

able and such responses therefore arise occurred. Journal of Memory and Language, 35, (1999). Recall accuracy and illusory memories:

from gist processing. 261–285. When more is less. Memory, 7, 233–256.

Sources of Bias in Memory for Emotions How accurately can people remem-

ber their own past emotions? Clini-

Linda J. Levine and Martin A. Safer1 cians routinely ask individuals to

rate the intensity and frequency

Department of Psychology and Social Behavior, University of California, Irvine,

with which they have experienced

California (L.J.L.), and Department of Psychology, Catholic University of America,

Washington, DC (M.A.S.) affective states such as depression

and anger over the past weeks or

months. Diagnostic and treatment

decisions concerning mental disor-

ders are based partly on such self-

Abstract of enduring personality traits.

reports. In nonclinical settings,

How accurately can people People’s memories for emo-

memories for emotions inform

remember how they felt in the tions provide highly con-

people’s current actions and future

past? Although some investi- densed and accessible

plans. Remembering emotions may

gators hold that emotional summaries of the relevance of

alleviate the need to store detailed

memories are resistant to past experiences to current

information about the past, while

change, we review evidence goals.

still enabling rapid decisions based

that current emotions, apprais-

on that information. For example,

als, and coping efforts, as well Keywords

one may retain “gut feelings” that

as personality traits, are all as- memory; recall; emotion; af-

guide decisions to seek out or

sociated with bias in recalling fect; bias

avoid a person or situation, with-

past emotions. Bias occurs as

out remembering the specific de-

memories of emotional states

tails that led to those feelings.

are updated in light of subse-

Most research on emotional Thus, it is important to determine

quent experience and goals. Bi-

memories focuses on how accu- how people recall their emotions,

ased memories in turn influence

rately people remember the events and what factors might be associ-

future plans and emotions, and

that elicited emotions. In this arti- ated with the accuracy or distor-

may contribute to the formation

cle, we ask a different question: tion of these memories over time.

Copyright © 2002 American Psychological Society

You might also like

- Confabulation and MisrememberingDocument13 pagesConfabulation and MisrememberingdanielahaisanNo ratings yet

- Applied Computational Economics and Finance PDFDocument521 pagesApplied Computational Economics and Finance PDFAidan HolwerdaNo ratings yet

- Astm A500Document6 pagesAstm A500notsofar100% (4)

- Sculpture 122 ArticleDocument3 pagesSculpture 122 ArticleGusti Ragil AprilianoNo ratings yet

- Neural Basis of ConsciousnessDocument13 pagesNeural Basis of ConsciousnessAlejandro León100% (1)

- False Memory Syndrome Research PaperDocument5 pagesFalse Memory Syndrome Research Papergxopkbxgf100% (3)

- False Memory Research PaperDocument8 pagesFalse Memory Research Paperafedyvlyj100% (1)

- Hoffman - Conscious Realism and The Mind Body ProblemDocument24 pagesHoffman - Conscious Realism and The Mind Body ProblemejonysNo ratings yet

- Blanco 2017 Cognitive Bias EncyclopediaDocument8 pagesBlanco 2017 Cognitive Bias Encyclopedia777 777No ratings yet

- What Science Tells Us About False and Repressed MemoriesDocument7 pagesWhat Science Tells Us About False and Repressed MemoriesKami67% (3)

- Knowing Who'S New: From Deja To Jamais Vu: Memory, and Cognition, II, 501-518Document2 pagesKnowing Who'S New: From Deja To Jamais Vu: Memory, and Cognition, II, 501-518abrahamzapruderNo ratings yet

- Hippocampal Maturation Drives Memory From Generalization To Specificity, Keresztes2018Document11 pagesHippocampal Maturation Drives Memory From Generalization To Specificity, Keresztes2018Ana Paula CastroNo ratings yet

- Naturalizing Consciousness A Theoretical Framework Edelman PNAS 2003Document5 pagesNaturalizing Consciousness A Theoretical Framework Edelman PNAS 2003hamletquiron100% (1)

- Rossano 2003-Evolution of ConsciousnessDocument30 pagesRossano 2003-Evolution of ConsciousnessМаја КокановићNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Architecture, Concepts, and Introspection: An Information-Theoretic Solution To The Problem of Phenomenal ConsciousnessDocument59 pagesCognitive Architecture, Concepts, and Introspection: An Information-Theoretic Solution To The Problem of Phenomenal ConsciousnessMarko RadovicNo ratings yet

- Meadhbh Foster@ucdconnect IeDocument24 pagesMeadhbh Foster@ucdconnect IeNondoda ChagiNo ratings yet

- Metcalfe 2008 MetamemoryDocument14 pagesMetcalfe 2008 MetamemoryhoorieNo ratings yet

- (Ebook) (Philosophy of Mind) Jerry A. Fodor - A Theory of Content and Other Essays-Chap8Document26 pages(Ebook) (Philosophy of Mind) Jerry A. Fodor - A Theory of Content and Other Essays-Chap8Sebastian ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Proust2007 Article MetacognitionAndMetarepresentaDocument25 pagesProust2007 Article MetacognitionAndMetarepresentavbaumhoffNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Awareness A Framework For Integrating Science Philosophy and MetaphysicsDocument20 pagesFundamental Awareness A Framework For Integrating Science Philosophy and MetaphysicsAjit GhoshNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On False MemoryDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On False Memorygihodatodev2100% (1)

- Review Memory Consolidation in Sleep: Dream or Reality: 2004 by Cell PressDocument14 pagesReview Memory Consolidation in Sleep: Dream or Reality: 2004 by Cell PressLeFührer Zabdiel PazaranNo ratings yet

- Nagel IntuitionsDocument33 pagesNagel IntuitionsAlejandroNo ratings yet

- Implicit Memory and MetacognitionDocument22 pagesImplicit Memory and MetacognitionMonica SanduleanuNo ratings yet

- The Somatic Marker Hypothesis and The Possible Functions of The Prefrontal CortexDocument9 pagesThe Somatic Marker Hypothesis and The Possible Functions of The Prefrontal CortexMauricio Vega MontoyaNo ratings yet

- MARGINS of REALITY The Role of Consciousness in The Physical World (Jahn, Robert G.dunne, Brenda J)Document425 pagesMARGINS of REALITY The Role of Consciousness in The Physical World (Jahn, Robert G.dunne, Brenda J)guilherme gomesNo ratings yet

- NeuroscientistDocument5 pagesNeuroscientistMouhamadou Moukhtar SarrNo ratings yet

- Pseudocontingencies: An Integrative Account of An Intriguing Cognitive IllusionDocument20 pagesPseudocontingencies: An Integrative Account of An Intriguing Cognitive IllusionYo MeNo ratings yet

- The Getting of Wisdom: Theory of Mind in Old Age: Francesca G. E. Happe Ellen WinnerDocument5 pagesThe Getting of Wisdom: Theory of Mind in Old Age: Francesca G. E. Happe Ellen WinnercursuriposdruNo ratings yet

- WestraCarruthers TheoryofmindDocument8 pagesWestraCarruthers Theoryofmindimroah339No ratings yet

- Art Cleeremans2011 TheRadicalPlasticityThesisDocument12 pagesArt Cleeremans2011 TheRadicalPlasticityThesisLuis Escobar L.-DellamaryNo ratings yet

- TOK Final EssayDocument7 pagesTOK Final EssayManishNo ratings yet

- 4 Response To CommentariesDocument5 pages4 Response To CommentariesMaximiliano PortilloNo ratings yet

- Dienes and Seth 2022 Conscious and Unconscious Mental StatesDocument39 pagesDienes and Seth 2022 Conscious and Unconscious Mental StatesMehwish LodhiNo ratings yet

- Hindsight Foresight: The Effect of Outcome Knowledge On Judgment Under UncertaintyDocument9 pagesHindsight Foresight: The Effect of Outcome Knowledge On Judgment Under Uncertaintyujangketul62No ratings yet

- Psyc - With Reference To Relevant Research Studies, To What Extent Is One Cognitive Process ReliableDocument2 pagesPsyc - With Reference To Relevant Research Studies, To What Extent Is One Cognitive Process Reliableloveis1020No ratings yet

- False Memory Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesFalse Memory Literature Reviewfeiaozukg100% (1)

- Logic and Biology Emotional Inference AnDocument30 pagesLogic and Biology Emotional Inference AnItzamna FuentesNo ratings yet

- Leslie 1987b Psychological ReviewDocument15 pagesLeslie 1987b Psychological ReviewanaNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Fmri Detection of False Eyewitness Memory 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: Fmri Detection of False Eyewitness Memory 1api-534201968No ratings yet

- Declarative y No Declarative Memory SystemsDocument14 pagesDeclarative y No Declarative Memory SystemsLuciano Dante MianiNo ratings yet

- Thiemo Breyer (Eds.) - Epistemological Dimensions of Evolutionary Psychology-Springer-Verlag New York (2015)Document248 pagesThiemo Breyer (Eds.) - Epistemological Dimensions of Evolutionary Psychology-Springer-Verlag New York (2015)LandoGuillénChávezNo ratings yet

- Paper Illusion of Explanatory DepthDocument47 pagesPaper Illusion of Explanatory DepthkolantreasNo ratings yet

- 1986 - Pribram - The Cognitive Revolution and Mind-Brain IssuesDocument15 pages1986 - Pribram - The Cognitive Revolution and Mind-Brain Issuesandres ceaNo ratings yet

- Varela, Francisco - The View From WithinDocument17 pagesVarela, Francisco - The View From Withinapi-3719401No ratings yet

- Phenomenology and Embodied ActionDocument16 pagesPhenomenology and Embodied ActionAjit GhoshNo ratings yet

- Unified Theories of CognitionDocument10 pagesUnified Theories of Cognitionvirtualinformatica159357No ratings yet

- Science & Society: Neuroethics Beyond GenethicsDocument5 pagesScience & Society: Neuroethics Beyond Genethicseduardoazevedo_ccciNo ratings yet

- Francisco J. Varela & J. Shears-First Person What, Why, HowDocument14 pagesFrancisco J. Varela & J. Shears-First Person What, Why, HowCiencias Cognoscitivas Costa RicaNo ratings yet

- Quine 1969Document13 pagesQuine 1969Hans OrangenbaumNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Journal For Psychoanalysis and The NeurosciencesDocument12 pagesNeuropsychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Journal For Psychoanalysis and The NeurosciencesPierreNo ratings yet

- What Is An "Explanation" of BehaviorDocument13 pagesWhat Is An "Explanation" of BehaviorDebasish SahooNo ratings yet

- How To Read MindsDocument18 pagesHow To Read MindsFahrizon IlmarNo ratings yet

- Hindsight Foresight The Effect of Outcome KnowledgDocument11 pagesHindsight Foresight The Effect of Outcome KnowledgAntonioNo ratings yet

- Taylor 2000Document36 pagesTaylor 2000MoqaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and NeuroscienceDocument19 pagesPhilosophy and NeuroscienceRandy AlzateNo ratings yet

- Impulsividad BarratDocument18 pagesImpulsividad BarratadrianaNo ratings yet

- How People Make Decisions That Involve Risk: A Dual-Processes ApproachDocument7 pagesHow People Make Decisions That Involve Risk: A Dual-Processes Approachjehu325No ratings yet

- The Brain has a Mind of its Own: Attachment, Neurobiology, and the New Science of PsychotherapyFrom EverandThe Brain has a Mind of its Own: Attachment, Neurobiology, and the New Science of PsychotherapyNo ratings yet

- Detection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationFrom EverandDetection of Malingering during Head Injury LitigationArthur MacNeill Horton, Jr.No ratings yet

- Adolescent Suicide and Self-Injury: Mentalizing Theory and TreatmentFrom EverandAdolescent Suicide and Self-Injury: Mentalizing Theory and TreatmentLaurel L. WilliamsNo ratings yet

- 10th Reflection and Refraction of Light Cbse Test Paper Solved-4Document4 pages10th Reflection and Refraction of Light Cbse Test Paper Solved-4ashokNo ratings yet

- Ch-03 Vectors: Lect-01Document20 pagesCh-03 Vectors: Lect-01Mohit TewatiaNo ratings yet

- Ic60 RCBODocument1 pageIc60 RCBOEng.Panelindo masNo ratings yet

- Literature Review in Research ProposalDocument5 pagesLiterature Review in Research Proposalmzgxwevkg100% (1)

- Dialogue Questionnaire-3rd SessionDocument3 pagesDialogue Questionnaire-3rd SessionMiguel HernandezNo ratings yet

- AP at RHHS 2016Document13 pagesAP at RHHS 2016Ryan YuNo ratings yet

- Fcaw Wps-001a PDFDocument3 pagesFcaw Wps-001a PDFirfan bari100% (1)

- Performing Cold Backup On Oracle 10gDocument10 pagesPerforming Cold Backup On Oracle 10gapi-250287051No ratings yet

- Unidrive M400: Fast Set-Up and Diagnostics With Real-Text Display, Integrated PLC and Safety InputsDocument16 pagesUnidrive M400: Fast Set-Up and Diagnostics With Real-Text Display, Integrated PLC and Safety InputsJunior enriquez cabezudoNo ratings yet

- Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Postsynthetic ModificationDocument60 pagesMetal-Organic Frameworks and Their Postsynthetic ModificationDean HidayatNo ratings yet

- Pipe Drafting and DesignDocument38 pagesPipe Drafting and DesignMohammad TaherNo ratings yet

- Online Class Activity Work No1-Ged0011Document2 pagesOnline Class Activity Work No1-Ged0011Khristian SorianoNo ratings yet

- Technical Specification For Ground Wire OPGWDocument28 pagesTechnical Specification For Ground Wire OPGWtanujaayer100% (1)

- Contermporary Arts Week 4Document3 pagesContermporary Arts Week 4Ira Jane Caballero0% (1)

- Self-Assessment Questions For Module 12 Project Procurement ManagementDocument12 pagesSelf-Assessment Questions For Module 12 Project Procurement ManagementLawal Idris AdesholaNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To LEX and YACC: SYSC-3101 1Document19 pagesAn Introduction To LEX and YACC: SYSC-3101 1Sruti SukumarNo ratings yet

- Tissues 1.Document2 pagesTissues 1.Adeaga ElizabethNo ratings yet

- Health8 - q1 - wk8 FinalDocument9 pagesHealth8 - q1 - wk8 FinalMary Ann MalaguitNo ratings yet

- Principles of Inheritance and Variation Class 12 Notes Biology - myCBSEguideDocument15 pagesPrinciples of Inheritance and Variation Class 12 Notes Biology - myCBSEguideShireen SuhailNo ratings yet

- Prashant Jain PJ Sir COMPLETE MATHS PYQ PDF PYQ's ExportDocument20 pagesPrashant Jain PJ Sir COMPLETE MATHS PYQ PDF PYQ's ExportSourabh Singh100% (1)

- User Manual Canon IXUS 165Document117 pagesUser Manual Canon IXUS 165zilltrinnNo ratings yet

- Getting StartedDocument17 pagesGetting StartedManuel Jesus Vera Duran100% (1)

- HP 15-CS 1016ur Quanta G7BD DAG7BDMB8F0 Rev 1ADocument49 pagesHP 15-CS 1016ur Quanta G7BD DAG7BDMB8F0 Rev 1AJuan Carlos Huaman HuertaNo ratings yet

- Ibs Ipoh Main, Jsis 1 30/06/20Document6 pagesIbs Ipoh Main, Jsis 1 30/06/20Muhdalihelmy MdYaakobNo ratings yet

- Maruti SuzukiDocument30 pagesMaruti SuzukiChaitanya KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Getting Started With MDM: 9 Steps ToDocument16 pagesGetting Started With MDM: 9 Steps ToSantiago GivNo ratings yet

- Iv TimersDocument48 pagesIv TimersanishthNo ratings yet