Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Belonging Without Believing

Belonging Without Believing

Uploaded by

m2f7rcwfqpCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Effective Intercultural Communication (Encountering Mission): A Christian PerspectiveFrom EverandEffective Intercultural Communication (Encountering Mission): A Christian PerspectiveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Summary of Class On James W Carey's A Cultural Approach To CommunicationDocument4 pagesSummary of Class On James W Carey's A Cultural Approach To CommunicationBarathNatarajNo ratings yet

- Networked Theology (Engaging Culture): Negotiating Faith in Digital CultureFrom EverandNetworked Theology (Engaging Culture): Negotiating Faith in Digital CultureNo ratings yet

- Module 13 The Human Person in SocietyDocument38 pagesModule 13 The Human Person in SocietyFreyja ErikaNo ratings yet

- Ecclesiology for a Digital Church: Theological Reflections on a New NormalFrom EverandEcclesiology for a Digital Church: Theological Reflections on a New NormalNo ratings yet

- Christianity and The Digital Age: Sustaining The Online ChurchDocument7 pagesChristianity and The Digital Age: Sustaining The Online ChurchPremier Publishers100% (1)

- Constructing Civility: The Human Good in Christian and Islamic Political TheologiesFrom EverandConstructing Civility: The Human Good in Christian and Islamic Political TheologiesNo ratings yet

- Click2Save Reboot: The Digital Ministry BibleFrom EverandClick2Save Reboot: The Digital Ministry BibleRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- A-Life LegasiDocument76 pagesA-Life Legasizaini0% (1)

- The Dis-Embodied Church Worship, New Media and The Body - Christianity in The Modern WorldDocument23 pagesThe Dis-Embodied Church Worship, New Media and The Body - Christianity in The Modern WorldMehmet HaberliNo ratings yet

- VirtualLivesArticleCampbellTeusner PDFDocument10 pagesVirtualLivesArticleCampbellTeusner PDFAndreea OanceaNo ratings yet

- Digital Society and ChurchDocument10 pagesDigital Society and ChurchShanza qureshiNo ratings yet

- Social Media in The New EvangelizationDocument13 pagesSocial Media in The New EvangelizationAndré James FadrigalanNo ratings yet

- Faith-Based Media Literacy EducationDocument20 pagesFaith-Based Media Literacy EducationAung MyintNo ratings yet

- Christianity and The Digital Age - Sustaining The Online Church PDFDocument7 pagesChristianity and The Digital Age - Sustaining The Online Church PDFRay MonthaNo ratings yet

- Christianity and Digital Media: Tim HutchingsDocument20 pagesChristianity and Digital Media: Tim HutchingsJwngma Bright BasumataryNo ratings yet

- Cybertheology: Thinking Christianity in the Era of the InternetFrom EverandCybertheology: Thinking Christianity in the Era of the InternetRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- American Academy of Religion: Oxford University PressDocument29 pagesAmerican Academy of Religion: Oxford University PressRaimundo SousaNo ratings yet

- Debate SpeechDocument1 pageDebate SpeechAkshit BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Digital Intimate Publics and Social Media 1St Ed Edition Amy Shields Dobson Full ChapterDocument67 pagesDigital Intimate Publics and Social Media 1St Ed Edition Amy Shields Dobson Full Chapteradolfo.milliken178100% (16)

- Issues in Feminist Public Theology - McIntoshDocument19 pagesIssues in Feminist Public Theology - McIntoshShieldmaiden of RohanNo ratings yet

- LIII World Communications Day, 2019 - "We Are Members One of Another" (Eph 4,25) - From Social Network Communities To The Human Community - FrancisDocument4 pagesLIII World Communications Day, 2019 - "We Are Members One of Another" (Eph 4,25) - From Social Network Communities To The Human Community - FrancisBryan VisqueraNo ratings yet

- Information, Communication & Society: To Cite This Article: Heidi A. Campbell & Mia Lövheim (2011) : INTRODUCTIONDocument15 pagesInformation, Communication & Society: To Cite This Article: Heidi A. Campbell & Mia Lövheim (2011) : INTRODUCTIONrinasariNo ratings yet

- Is Internet-Centrism A Religion?Document6 pagesIs Internet-Centrism A Religion?jaleesrehmanNo ratings yet

- Social NetworksDocument3 pagesSocial NetworksHue TranNo ratings yet

- Pope Benedict XVI: Message For The 47th World Communications DayDocument3 pagesPope Benedict XVI: Message For The 47th World Communications DayJeanoRusticoCruzNo ratings yet

- Public Intellectuals and the Common Good: Christian Thinking for Human FlourishingFrom EverandPublic Intellectuals and the Common Good: Christian Thinking for Human FlourishingNo ratings yet

- Communication in Religion and Its Integrative ImplDocument10 pagesCommunication in Religion and Its Integrative Implgabby macaNo ratings yet

- Hillsong Church Expansive Pentecostalism Media and The Global City Palgrave Studies in Lived Religion and Societal Challenges 1St Ed 2021 Edition Miranda Klaver Full ChapterDocument68 pagesHillsong Church Expansive Pentecostalism Media and The Global City Palgrave Studies in Lived Religion and Societal Challenges 1St Ed 2021 Edition Miranda Klaver Full Chaptermarie.peterson493100% (18)

- A Theology of CommunicationDocument13 pagesA Theology of CommunicationChhurlianaNo ratings yet

- Give Me That Online Religion. by Brenda E. Brasher. Rutgers UniversityDocument4 pagesGive Me That Online Religion. by Brenda E. Brasher. Rutgers UniversityGandac Ionut DanielNo ratings yet

- Ge3 2Document3 pagesGe3 2Charm Angel LopezNo ratings yet

- Interpretative CommunitiesDocument15 pagesInterpretative CommunitiesMartín Echeverría VictoriaNo ratings yet

- 7650-Article Text-26209-4-10-20181218Document17 pages7650-Article Text-26209-4-10-20181218Yopi SabatudungNo ratings yet

- Impact of Globalization On Religion: (University Name)Document15 pagesImpact of Globalization On Religion: (University Name)Obaida ZoghbiNo ratings yet

- Being Sacramental in Today Web3Document7 pagesBeing Sacramental in Today Web3Duan GonmeiNo ratings yet

- ALPERT CARINO WW2 2ndQDocument1 pageALPERT CARINO WW2 2ndQZach Cariño100% (1)

- Christian Living Module 5week 5Document2 pagesChristian Living Module 5week 5jomarov funovNo ratings yet

- Talking God: The Legitimacy of Religious Public ReasoningDocument80 pagesTalking God: The Legitimacy of Religious Public ReasoninggodzillafoodNo ratings yet

- Christianity and the Soul of the University: Faith as a Foundation for Intellectual CommunityFrom EverandChristianity and the Soul of the University: Faith as a Foundation for Intellectual CommunityNo ratings yet

- The Digital Nexus: Identity, Agency, and Political EngagementFrom EverandThe Digital Nexus: Identity, Agency, and Political EngagementNo ratings yet

- (Download PDF) Intercultural Communication in Contexts 8Th Edition Judith Martin Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pages(Download PDF) Intercultural Communication in Contexts 8Th Edition Judith Martin Full Chapter PDFprumekarr89% (9)

- John Drane The Mcdonaldization of The Church - Spirituality, Creativity and The Future of The ChurchDocument5 pagesJohn Drane The Mcdonaldization of The Church - Spirituality, Creativity and The Future of The ChurchJane CrystelNo ratings yet

- Discipline, Devotion, and Dissent: Jewish, Catholic, and Islamic Schooling in CanadaFrom EverandDiscipline, Devotion, and Dissent: Jewish, Catholic, and Islamic Schooling in CanadaNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism and ReligionDocument2 pagesPostmodernism and ReligionFilozotaNo ratings yet

- Virtual Ritual, Real FaithDocument18 pagesVirtual Ritual, Real FaithantonioNo ratings yet

- Globalization of ReligionDocument3 pagesGlobalization of ReligionPatrick Lanz Padilla100% (1)

- Inaku K. Egere, Social Media and Mission-Based Marketing Approach For New Evangelization in The Digital Age"Document21 pagesInaku K. Egere, Social Media and Mission-Based Marketing Approach For New Evangelization in The Digital Age"popa_ghNo ratings yet

- A Reflection On Inter MirificaDocument1 pageA Reflection On Inter MirificaChristian John DakayNo ratings yet

- Integrating Social Media To Spirituality: Beneficial and Adverse EffectsDocument12 pagesIntegrating Social Media To Spirituality: Beneficial and Adverse EffectsAshley CastilloNo ratings yet

- Polarization EditedDocument4 pagesPolarization Editedchachacarolyne5No ratings yet

- Socio101 Assignment3Document1 pageSocio101 Assignment3Kristine Paulina B. BenitezNo ratings yet

- Mystical Traditions: Approaches To Peaceful CoexistenceDocument354 pagesMystical Traditions: Approaches To Peaceful CoexistenceAlejandro CabNo ratings yet

- DORS2015: Book of AbstractsDocument32 pagesDORS2015: Book of AbstractsStacey PitsillidesNo ratings yet

- Relativism and Religion: Why Democratic Societies Do Not Need Moral AbsolutesFrom EverandRelativism and Religion: Why Democratic Societies Do Not Need Moral AbsolutesNo ratings yet

- ANDREWDocument6 pagesANDREWJacob YeboahNo ratings yet

- Conformity: The Power of Social InfluencesFrom EverandConformity: The Power of Social InfluencesRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (13)

- Part I: Overview-What Is Evangelization? Caroline Cerveny, SSJ-TOSF, D. MinDocument39 pagesPart I: Overview-What Is Evangelization? Caroline Cerveny, SSJ-TOSF, D. MinNii Okai QuayeNo ratings yet

- The Mediatisation of Religion Theorising Religion Media andDocument18 pagesThe Mediatisation of Religion Theorising Religion Media andjowanna_ramona2007No ratings yet

- A Course in Community StudiesDocument47 pagesA Course in Community StudiesPeter ForsterNo ratings yet

- IB ACIO-II - Exe 2023Document4 pagesIB ACIO-II - Exe 2023jashanpreetkaur0990No ratings yet

- Social SinDocument27 pagesSocial SinLyh Ann NavarroNo ratings yet

- (Oxford World's Classics) René Descartes, Ian Maclean-Discourse Method of Correctly Conducting Ones Reason and Seeking Truth in The Sciences-Oxford University Press, USA (2006) PDFDocument161 pages(Oxford World's Classics) René Descartes, Ian Maclean-Discourse Method of Correctly Conducting Ones Reason and Seeking Truth in The Sciences-Oxford University Press, USA (2006) PDFDovydas CaturianasNo ratings yet

- Beacon of LightDocument3 pagesBeacon of LightMuzamil KamokaNo ratings yet

- Ifp001 Midterm PDFDocument4 pagesIfp001 Midterm PDFMessiyah C. CalambaNo ratings yet

- Studies of Religion Notes - BioethicsDocument2 pagesStudies of Religion Notes - BioethicsNicholas RobertsNo ratings yet

- Qu Ac 2021-2023Document2 pagesQu Ac 2021-2023biomathenNo ratings yet

- From Curses To Blessings - Removing Generational CursesDocument726 pagesFrom Curses To Blessings - Removing Generational CursesClerry Samuel100% (10)

- Sl. No. Event Venue Supporting Agency M/O Ayush Nodal Officer Technical Support OfficerDocument1 pageSl. No. Event Venue Supporting Agency M/O Ayush Nodal Officer Technical Support OfficerAnshu SinghNo ratings yet

- The Power of PrinciplesDocument7 pagesThe Power of Principlessfarel567No ratings yet

- Maximize Your CallDocument5 pagesMaximize Your CallPrince AdjeiNo ratings yet

- Body and Soul in Dionysius The AreopagitDocument6 pagesBody and Soul in Dionysius The AreopagitVasilisaPrekrasnaNo ratings yet

- The Lucado Life Lessons Study Bible, NKJV - Inspirational Applications For Living Your Faith (PDFDrive)Document1,866 pagesThe Lucado Life Lessons Study Bible, NKJV - Inspirational Applications For Living Your Faith (PDFDrive)ariana, jazlynn, and taden Zook100% (5)

- The Travelers and The TreeDocument7 pagesThe Travelers and The TreefizzyshadowNo ratings yet

- Church Growth Theology: Arthur F. Glasser Fuller Theological SeminaryDocument18 pagesChurch Growth Theology: Arthur F. Glasser Fuller Theological SeminaryDenni PinontoanNo ratings yet

- Raja Ram Mohan Roy NotesDocument3 pagesRaja Ram Mohan Roy NotesAnish JainNo ratings yet

- Bible Character NoahDocument4 pagesBible Character NoahRoberto Queiroz GomesNo ratings yet

- Turning The Wheel of Dharma (Trans. by Thich Nhat Hanh)Document5 pagesTurning The Wheel of Dharma (Trans. by Thich Nhat Hanh)ArcalimonNo ratings yet

- Numerology NimaDocument2 pagesNumerology NimaImha ChuaNo ratings yet

- Man's Real Nature Is DivineDocument37 pagesMan's Real Nature Is DivineMinakshi KanuNo ratings yet

- Srimati RadharaniDocument3 pagesSrimati Radharanirishabh108No ratings yet

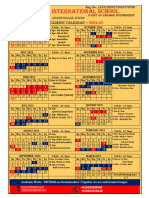

- Academic Calendar 2024-25Document1 pageAcademic Calendar 2024-25Passionate EducatorNo ratings yet

- Basic Christmas WreathDocument11 pagesBasic Christmas Wreathkristy petersNo ratings yet

- Full Download New Corporate Finance Online 1st Edition Eakins Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesFull Download New Corporate Finance Online 1st Edition Eakins Solutions Manualprindivillemaloriefx100% (42)

- 4th SUNDAY OF LENT YEAR ADocument136 pages4th SUNDAY OF LENT YEAR ANino ValenciaNo ratings yet

- 7248 Aukst MargeticDocument7 pages7248 Aukst MargeticMarko NikolicNo ratings yet

- Hindu God Mantras in TamilDocument3 pagesHindu God Mantras in TamilVictoriaNo ratings yet

- Marriage - A Biblical Illustration of Our Faith Commitment To Jesus Christ For SalvationDocument10 pagesMarriage - A Biblical Illustration of Our Faith Commitment To Jesus Christ For SalvationO Canal da Graça de Deus - Zé & SandraNo ratings yet

- Tamil Nadu State MSF Conference: The Times of LeagueDocument8 pagesTamil Nadu State MSF Conference: The Times of LeaguemuslimleaguetnNo ratings yet

Belonging Without Believing

Belonging Without Believing

Uploaded by

m2f7rcwfqpOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Belonging Without Believing

Belonging Without Believing

Uploaded by

m2f7rcwfqpCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of

Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

brill.com/ijpt

Belonging without Believing

Church as Community in an Age of Digital Media

Esther McIntosh

York St John University, UK

e.mcintosh@yorksj.ac.uk

Abstract

This article flips on its head Grace Davie’s notion of ‘believing without belonging’. From

a consideration of the internet and social networking media as a public space and a

new ‘public’ or fifth estate, the article proceeds through a discussion of religious activ-

ity online to investigate the concept of community, the function of communication

theology and the place of morality in online activity. Finally, the article considers the

popularity of Sunday Assembly and concludes that there is a significant move towards

belonging without believing both on- and offline.

Keywords

belonging – believing – community – church – digital media – digital theology

Introduction

According to Grace Davie’s well-worn argument the decline in traditional

church attendance is not fully accounted for by secularization and loss of the-

istic belief; rather, she claims that while religious practice is in decline, reli-

gious belief is alive and well. Hence, she asserts that Britain has entered an

* This article began as a shorter presentation for the Global Network of Public Theology

consultation ‘The Word and the World’, University of Chester, 2–6 September 2013; it was

then developed for an invited presentation at King’s College London’s Research Institute for

Systematic Theology before being further developed into this article. I am grateful for the

feedback I have received from audiences and referees.

© koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���5 | doi 10.1163/15697320-12341389

132 mcintosh

era of ‘believing without belonging’.1 Turning Davie’s oft-cited statement on

its head, through an exploration of the concepts of community and church,

I will argue that, with the advent of social networking media, Twitter and

virtual churches, we have entered an era of ‘belonging without believing’.

In previous work I have focused on the concept of community in face-to-

face relations.2 In particular, I have borrowed the notion of community from

the work of John Macmurray, who argues for a distinction between society

and community.3 That is, groups of people related for a specific purpose or

to achieve a common goal—such as work colleagues, sports clubs or activ-

ist networks—are societies, at least at first; they may become communities if

relationships among the members deepen and go beyond their roles and func-

tions, so that they relate to one another for the sake of the relationship itself.

Communities, then, are to be found in families and among friends, where care

and concern for others are the bedrock of the relationships. We may also find

communities among religious groups, where there is genuine concern for the

well-being of fellow worshippers, who are, then, treated as ends in themselves

and not as a means to an end. Historically, functional relationships have devel-

oped into friendships over time, through the communication of our inner

selves during face-to-face contact. While pen pals have maintained long dis-

tance relationships, it is generally true that close relationships are harder to

sustain over distance, both because communication is out-of-date by the time

it is shared and because the possibilities for practical acts of kindness—such

as sharing childcare, or cooking a meal—are limited. This concept of com-

munity fits with the African notion of ubuntu: I am because we are. However,

this notion of community is deeply challenged by digital media, where geo-

graphical distance is no longer a barrier, updates are instant and friendships

are maintained without (or with infrequent) face-to-face contact.

At the heart of our friendships, our communities and our religion we find the

human desire to communicate. Religions rely on the ability to communicate,

especially over space and time, in order to maintain continuity and a sense

1 Grace Davie, Religion in Britain Since 1945: Believing without Belonging (Oxford: Blackwell,

1994), p. 94; rewritten as Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell,

2015), still using the phrase ‘believing without belonging’, while also introducing the notion

of ‘vicarious religion’.

2 See, for example, Esther McIntosh, ‘Community and Society: Macmurray and New Labour’,

in S. C. H. Kim and P. Kollontai, eds, Community Identity: Dynamics of Religion in Context

(London: T. & T. Clark, 2007), pp. 69–88.

3 Esther McIntosh, John Macmurray’s Religious Philosophy: What It Means to be a Person

(Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011), esp. ch. 5.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 133

of identity, and to transmit meaning. Historically, religions communicated to

self-selecting members through the human voice and the written word. More

recently, advances in technology enabled the dissemination of religious ideas

to wider and less committed groups through radio and television, and now

religion is grappling with social media. The growth in e-churches is challeng-

ing the notion of ‘church’ as a physical gathering of persons, in a particular

physical space, that is both the focus of and the means by which community

is sustained.

This burgeoning field of digital media has been assessed mostly within North

American communication studies and sociology of religion (in particular by

Heidi Campbell, Gordon Lynch, Stewart Hoover and Pauline Cheong who look

at how religious groups view and use such media); there has also been some

similar work done that is more focused on Europe and UK, by CODEC Research

Centre for Digital Theology at the University of Durham and Tim Hutchings in

particular.4 Work in digital theology tends to survey current use of digital tech-

nology, focus optimistically on the perceived need to engage with social media

in order to be culturally relevant and to evangelize and/or warn against idola-

try of technology and the dangers of isolation and addiction, while attempting

to address what it means to be a person of faith in a digital age.5 While such

works represent significant developments in the field, there is more to be done

from the perspectives of philosophical and public theology.

Public theology frequently draws on the three publics as put forward

by David Tracy—academy, church, society—and is concerned with the

4 For more information on CODEC, go to <http://www.dur.ac.uk/codec> [accessed 21 October

2014].

5 See, for example, Barry Taylor, Entertainment Theology: Exploring Spirituality in a Digital

Democracy (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008); Justin Wise, The Social Church: A

Theology of Digital Communication, new edn (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2014); Brandon

Vogt, The Church and New Media: Blogging Converts, Online Activists and Bishops Who Tweet

(Huntington: Our Sunday Visitor, 2011); Elmer Towns and Todd Mullins, Online Churches:

An Extensive Analysis and Application (Lynchburg: Liberty University Press, 2014); Kimberly

Young and Patrice Klausing, Breaking Free of the Web: Catholics and Internet Addiction

(Cincinnati: Franciscan Media, 2007); Derek C. Schuurman, Shaping a Digital World: Faith,

Culture and Computer Technology (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2013); Douglas Estes,

SimChurch: Being the Church in the Virtual World (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009); Jesse

Rice, The Church of Facebook: How the Hyperconnected are Redefining Community (Colorado

Springs: David C. Cook, 2009); Jonah Lynch, The Scent of Lemons (London: Darton, Longman

and Todd, 2012); Dwight J. Friesen, Thy Kingdom Connected (Grand Rapids: Baker Books,

2009); Jana Marguerite Bennett, Aquinas on the Web? Doing Theology in an Internet Age

(London and New York: T. & T. Clark, 2012).

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

134 mcintosh

c ommunication of theological ideas across these publics.6 Further, Sebastian

Kim suggests that there are ‘six main players in the public sphere in contem-

porary society: the state, the market, the media, the academy, civil society and

religious communities’.7 Of particular interest to public theology, then, is the

discussion concerning whether social media is properly referred to as another

‘public’, a public sphere or a public space. Theological conversation can and

does happen online, and, in this sense, even if it lacks the depth of more formal

academic theology, the internet definitely represents a space for God-talk, but

this is not sufficient to constitute a public sphere. Borrowing from Habermas,

Jodi Dean states: ‘the public sphere is the site and subject of liberal democratic

practice. It is that space within which people deliberate over matters of com-

mon concern, matters that are contested and about which it seems necessary

to reach a consensus’.8 While Habermas’ notion of a public sphere in which

social status is eradicated and citizens reach rational agreement has been

widely criticized as an ideal, since many groups find themselves excluded from

having their voices heard, the internet revives this idea of the public sphere

(only now citizens are operating as ‘netizens’). In theory, the internet prom-

ises greater opportunities for inclusion and participation in political democ-

racy, and in practice it has been the site of some political activism through,

for example, change.org and the hacking and ‘bombing’ of corporation web-

sites. Nevertheless, it is also the case that access to the internet is limited to a

small fraction of the world’s population and much of the discussion that takes

place online is inane and/or not democratic but racist, sexist and engaged in

the expression of vitriolic rage (known as ‘flaming’) rather than rational dis-

course aimed at reaching agreement. We are currently seeing the internet

being used as a tool in the radicalization of young persons by IS (ISIS/ISIL),

who then find the reality in Syria to be vastly more terrifying than they had

imagined. In practice, the Net is subject to the same power play and commer-

cial influence as the rest of capitalist culture; its focus is entertainment and

advertising revenue, with those who have the financial backing able to pay for

6 David Tracy, The Analogical Imagination: Christian Theology and the Culture of Pluralism

(London: SCM, 1981), p. 5; see also, for example, John W. de Gruchy, ‘Public Theology as

Christian Witness: Exploring the Genre’, International Journal of Public Theology, 1:1 (2007),

26–41.

7 Sebastian Kim, ‘Editorial’, International Journal of Public Theology, 6:2 (2012), 131–6 at 132.

8 Jodi Dean, ‘Why is the Net not a Public Sphere’, Constellations, 10:1 (2003), 95–112 at 95; see

also Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into

a Category of Bourgeois Society, trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge: Polity, 1989 [original in

German, 1962]).

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 135

websites and airtime to promote their own agendas. Hence, Dean states that

the Net is the ‘ideology of publicity in service of communicative capitalism’;9

as such, it is a public space, but not a public sphere.

Alternatively, in terms of the classical estates of the realm, networked indi-

viduals (especially bloggers and online journalists) may be seen as constitut-

ing a fifth estate in addition to the four estates of clergy, nobility, commoners

and media (in the form of print journalism). As the fifth estate, netizens exist

outside of mainstream power structures and institutions, whether as terrorists,

campaigners for justice or politically indifferent citizens, and in this sense may

constitute another ‘public’. Indeed, it is this ability to exist outside of mainline

religious institutions that is significant for public theology.

While Davie suggests that Britons believe without belonging, Callum Brown’s

research identifies a ‘steady growth’ in the UK of those who regard themselves

as having no religion ‘from 1983 (when it stood at 31.6% of adult population)’

to over fifty per cent in 2009.10 Thus, by drawing on the work of Campbell and

others, in this article, I focus on the notion of community in relation to online

religious activity in order to discover the sense in which this new public space

represents a significant challenge to Christianity (and other religions) in the

form of communication and mediation, the realities and possibilities of virtual

church, issues of moral behaviour online, and religious practices and activities

that take place outside of a singular religious belief system. In fact, while reli-

gious extremism constitutes a minority off- and online, religious activity on the

Net is engaged in by those who have no fixed religious beliefs and those who

borrow from a multiplicity of belief systems, because it increases the possibili-

ties of belonging without believing (rather than believing without belonging).

In what follows, I will use the phrase ‘traditional church’ to refer to main-

stream Christian practice, characterized by weekly services in a designated

(church) building, involving singing, praying, a sermon from an ordained

leader, as well as the regular (but not necessarily weekly) sacramental rituals of

communion/Eucharist and baptism (whether of adults or infants). Admittedly,

the Roman Catholic Church has a greater number of sacraments, Quaker prac-

tice is less ritualistic and house churches are less focused on a designated

building, but the aforementioned description will suffice for the majority of

mainstream Christian practice. Furthermore, I am using the basic definition

of ‘church’ derived from the Greek ekklēsia, namely a public gathering of

believers whose aim is friendship and social action. While this definition of

9 Dean, ‘Why is the Net not a Public Sphere’, 98.

10 Callum G. Brown, ‘The People of “No Religion”: The Demographics of Secularisation in the

English-Speaking World Since c. 1900’, Archiv für Sozialgeschichte, 51 (2011), 37–61 at 56.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

136 mcintosh

church has a well-established provenance in Christianity, at various periods

the focus on individual spirituality has been more prominent than action for

social justice; thus, at the 2013 meeting in Rome of the current Archbishop of

Canterbury, Justin Welby, and Pope Francis, the emphasis on friendship and

social justice was revived.11

Communication and Mediation

With the decline in traditional church attendance, Christian churches are

increasingly seeking to communicate their message over the internet. In this

respect, there is a distinction to be made between online religion and religion

online. Religion online, Rachel Wagner explains, is the passive communication

of information about beliefs, services and so on, whereas online religion goes

further than this and includes active participation in virtual religious activities

such as discussion, prayer and other forms of worship.12 In many cases, reli-

gious groups that use the internet not only blur the distinction between online

and offline religion by having an online and an offline presence, they also blur

the distinction between online religion and religion online by engaging in

both. Particularly among the more evangelical Protestant churches, there is an

assumption that they should and must use digital media, as Wilson and Moore

insist: ‘[t]he more digital, participatory, and immersive, the better’.13

However, the drive to get online is not matched by a corresponding analysis

of the effects of so doing; neither the effect of mediating the Christian message

through digital technology, nor the possible distortions of that message that

media and especially digital media make possible are analysed fully. This lack of

analysis, Peter Horsfield suggests, is due to an historical understanding (or mis-

understanding) of media as ‘instruments for carrying ideas after theologians

11 The meeting took place at Vatican City on 14 June 2013; their addresses to each other can

be read at ‘Archbishop Justin Meets Pope Francis in Rome’ (14 June 2013), Justin Welby The

Archbishop of Canterbury, <http://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/articles.php/5076/

archbishop-justin-meets-pope-francis-in-rome> [accessed 22 October 2014].

12 Rachel Wagner, Godwired: Religion, Ritual and Virtual Reality (Abingdon and New York:

Routledge, 2012), p. 133.

13 L. Wilson and J. Moore, The Wired Church 2.0, illustrated edn (Nashville: Abingdon Press,

2008), as cited by Stefan Gelfgren, ‘“Let There be Digital Networks and God Will Provide

Growth?” Comparing Aims and Hopes of 19th-Century and Post-Millennial Christianity’,

in Pauline Hope Cheong, Peter Fischer-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfgren and Charles Ess, eds,

Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture: Perspectives, Practices and Futures (New York:

Peter Lang, 2012), pp. 228–42 at p. 235.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 137

have constructed them’.14 On the contrary, theology is shaped by its mediation.

Nevertheless, theology has always been mediated. Traditional church services

rely on the church leader and the sacraments to mediate the Christian mes-

sage; hence, the church is always engaged in mediation. Moreover, technology

has played a large part in that mediation—from the written word to radio and

television—the digital is just the latest form of technological mediation. Thus,

Clint Schnekloth argues that we should view ‘digital media as ministry, rather

than as tools to communicate about ministry’.15

Such communication, however, needs to be well constructed and shared.

Admittedly, as institutional affiliation has dwindled, churches have had rea-

sonable grounds for assuming that digital media is essential for connecting

with people, but the internet does not necessarily make it easier to reach

them. While the use of new media can give religious leaders access to a wide

audience, and in this sense, an increased opportunity to speak with authority,

overall, digital mediation reduces the authority of traditional texts and leaders.

Religious plurality on the World Wide Web and the lack of any one monopoly

offers the consumer a great deal of choice. Hence, the religious consumer has

access to searchable texts and commentaries and is bombarded with multi-

ple voices. At the same time, the ease with which web content can be created

and uploaded often means that the searcher is overwhelmed by poor quality,

unhelpful material. Given these factors, the user may be more interested in

the relevance and usefulness of material than in its authority or consistency;

consequently, when choosing where and when to grant authority, the user may

be drawn in by a leader’s personality rather than by his or her formal qualifica-

tions. Thus, while an online presence can give a religious group a certain brand

value (which is especially useful for megachurches and emerging churches),

it will be lost if it does not stand out from the crowd. Indeed, as Musa and

Ahmadu state: ‘If others cannot distinguish between the spirituality of the

Christian faith and that of other faiths, it is a failure of how the churches’ story

is being told in the new environment of multiple voices and sources’.16

14 Peter Horsfield, ‘“A Moderate Diversity of Books?” The Challenge of New Media to the

Practice of Christian Theology’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital

Religion, Social Media and Culture, pp. 243–58 at p. 246.

15 Clint Schnekloth, ‘Virtual Church’, Word and World, 32:3 (2012), 245–51 at 249 (original

italics).

16 Bala A. Musa and Ibrahim M. Ahmadu, ‘New Media, Wikifaith and Church Brandversation:

A Media Ecology Perspective’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital

Religion, Social Media and Culture, pp. 63–80 at p. 75.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

138 mcintosh

Whether we resist or embrace new media, it is here and religion is changed

by it. Since the development of interactive Web 2.0 technology (around 2005),

the user has been able to be a participant and co-creator of web content; this

has led to the hybrid terms ‘produser’17 and ‘prosumer’18 to express the com-

bined notion of being both a producer and a consumer. In religious circles

then, this means that faith has become ‘wikifaith’ and religion has become

‘religion 2.0’,19 collaboratively constructed and edited online by multiple users.

One striking example of digital mediation is found among Colorado Bible

College students who celebrate online communion and have engaged in an

online discussion with the college staff about whether this is an appropriate

enactment of a central Christian ritual.20 In part, an answer to their discus-

sion would have to consider the purpose of offline communion—namely to

remember Jesus’ death and the promise of salvation—and whether this can be

achieved online. While there are additional benefits to be found in offline cele-

bration of the communion, there is no tangible reason why remembrance can-

not take place online, and, hence, there is no indisputable reason for opposing

the practice. Indeed, online communion is not so different from the commu-

nion services that are broadcast over the radio in both Catholic and Protestant

traditions. In addition, there may be very little difference between taking com-

munion collectively but individually in a church building and taking it alone

but simultaneously in separate living rooms and bedrooms.

Moreover, as Jeffrey Mahan explains: ‘lay and folk movements have long

created mediations that contested with religious authorities to shape practice

and doctrine’.21 Thus, while a religion that adapts to changing media finds it

is changed in form and content, it will also find that it gains social power.22

Besides, Christianity has already been changed by media, in ways that were

contested at the time but do not seem so threatening now. With the advent

of the printing press, sacred texts became accessible for educated lay people,

which also led to greater individual freedom in the interpretation of those

17 A. Bruns, Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage (New

York: Peter Lang, 2008).

18 Musa and Ahmadu, ‘New Media, Wikifaith and Church Brandversation’, in Cheong,

Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, pp.

63–80 at p. 70.

19 See Pauline Hope Cheong and Charles Ess, ‘Introduction: Religion 2.0? Relational and

Hybridizing Pathways in Religion, Social Media, and Culture’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen,

Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, pp. 1–21 at p. 2.

20 See Jeffrey H. Mahan, ‘Religion and Media’, Religion Compass, 6:1 (2012), 14–25 at 14.

21 Ibid., 17.

22 Ibid., 18.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 139

texts. Clement of Alexandria describes the objection to replacing oral trans-

mission with the written word as follows:

The living voice was the best medium for the communication of Christian

truth. Writings were public and it was wrong to cast pearls before swine.

To write implied that one was inspired by the Holy Spirit and this was a

presumptuous claim. If one must write, it were better that one should

write badly. The heretics had shown that a clever style could mislead and

corrupt.23

Clement’s response to the objection is that it is better to be in control of

what is being written than to leave the writing to those who might misuse it.

Admittedly, written text gives a certain stability to beliefs, but over time its

cultural references are obscured and it needs reinterpreting.

With further advances in technology, Christianity entered the era of radio

and television evangelism, which produced another dramatic change. Since

radio and television have listeners and viewers rather than participants, and

they are more concerned with entertainment than with interaction, they

rendered religion more passive than active. Similarly, the development of

confession and prayer ‘apps’ for smartphones may do more to appease the

user than to encourage engagement with a religious community or genuine

repentance and a change of lifestyle. Yet, with the advent of the internet and

social networking media, it is possible for religiously interested individuals

to be actively involved in religious activities and discussions. Thus, we have

entered a dynamic era in which the individual is free to construct her or his

religious identity online. In fact, in constructing an online religious-self, the

user is able to pick and choose aspects of different religions and denomina-

tions, as opposed to having to be a confirmed member of just one religion or

denomination. As Linda Woodhead’s recent research confirms, we are in a

‘new era of post-traditional religious identity’ in which the popularity of hold-

ing multiple religious affiliations is growing.24 In this sense, then, the user is

23 Clement of Alexandria, Stromateis, first ch, as cited by Peter Horsfield, ‘Electronic

Media and the Past-Future of Christianity’, in Jolyon Mitchell and Sophia Marriage, eds,

Mediating Religion: Conversations in Media, Religion and Culture (London and New York:

T.&T. Clark/Continuum, 2003), pp. 271–82 at pp. 276–7.

24 Linda Woodhead’s keynote presentation at ‘Practical Theology and Public Life’ con

sultation, University of Birmingham, 28 February 2013, drawing on information published

in L. Woodhead and R. Catto, eds, Religion and Change in Modern Britain (Abingdon and

New York: Routledge, 2012).

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

140 mcintosh

empowered to find alternative beliefs and practices that make sense for him

or her, as opposed to accepting the beliefs handed down by parents and peers.

Nevertheless, as Mahan reveals, many adult believers are seeking out beliefs

and practices that confirm views they already hold, rather than engaging with

beliefs and practices that contest those views.25

Teenagers, however, while sharing more than ever before on social network-

ing media—such as relationship status, likes and dislikes, menus and moods—

do not engage equally in such a public and open discussion of religion and

religious issues. A US study in 2011 revealed that, while 62 per cent of users

self-identify as religious on social media, only 30 per cent engage in online dia-

logue on religious topics. In addition, the researchers found that 15–30 per cent

of users self-identify as ‘spiritual’ rather than religious, while among members

of Protestant denominations there was a trend for choosing ‘Christian-other’

(58 per cent of those self-identifying as religious) from a drop down menu,

rather than ‘Protestant’.26 By comparing the information on social media with

that given on paper questionnaires, the researchers confirmed that those who

identified as ‘spiritual’ online, expressed negative views towards organized reli-

gion offline and/or viewed religion as something private rather than public. By

not being involved in discussions around religious topics, though, those who

view religion as private are also not involved in the shaping of religious iden-

tity in the public sphere. As we may expect, discussion of religious views and

activities online occurs most among those who are part of a large network of

evangelical Protestants and who believe that proselytizing is a tenet of their

faith; yet, despite their open engagement with public discourse on religion, the

preference for ‘Christian-other’ over ‘Protestant’ gives rise to questions about

religious literacy.

Furthermore, Mark Johns reveals that religious groups attracting large num-

bers of persons prepared to make a religious declaration on social network-

ing media are not actually facilitating dialogue or increasing religious activity.27

Hence, church leaders who justify their online presence by claiming that it is a

25 Mahan, ‘Religion and Media’, at 22.

26 See Piotr S. Bobkowski and Lisa D. Pearce, ‘Baring their Souls in Online Profiles or Not?

Religious Self-Disclosure in Social Media’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50:4

(2011), 744–62 (they are primarily referring to MySpace, which was more popular than

Facebook at the time of their research).

27 Mark D. Johns, ‘Voting “Present”: Religious Organizational Groups on Facebook’, in

Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture,

pp. 151–68 at pp. 153–63.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 141

means of staying relevant should consider whether collecting Facebook ‘likes’

really has any value.

Communication Theology

Nevertheless, church leaders do need to understand the significance and pos-

sibilities inherent in new media. For centuries, theology has been in the hands

of a small group of authoritative voices, a literate elite, who have focussed on

producing consistent statements of faith and on disseminating their theology

through commercially published books. At the moment, the availability of

digital media is challenging this method of knowledge transfer; digital text is

more fluid and easily altered than printed matter and can be manipulated by

the user. Thus, Bailey and Storch state:

There is a new passion for authentic communication. People want to be

part of an open and honest conversation . . . One-way communication

is no longer enough . . . [People] are looking for those who are willing

to open the door and let others inside. Blogging is a revolution in com-

munication, community, and authentic conversation; a revolution that

churches cannot afford to ignore.28

Clearly, online communication has interactive value, but Bailey and Storch

do not pause to discuss whether this is really an indication of ‘authentic

communication’. Since online identity is deliberately constructed so as to pres-

ent the self in a certain way, it is much easier to present pseudo-beliefs and a

pseudo-persona online than it would be in face-to-face contact. Rather than

‘open and honest conversation’ then, digital media may mean having to deal

with aggressive posts and dishonest blogs.

We need, therefore, a ‘communication theology’.29 As Avery Dulles insists:

‘theology is at every point concerned with the realities of communication’.30

He bases this claim on the Trinitarian conception of a self-communicating,

28 B. Bailey and T. Storch, The Blogging Church (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007), as cited

by Gelfgren, ‘“Let There be Digital Networks and God Will Provide Growth?”’, in Cheong,

Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, at p. 237.

29 Frances Forde-Plude is a pioneer in this field, see <http://www.francesplude.org>

[accessed 26 August 2014].

30 Avery Dulles, The Craft of Theology: From Symbol to System (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan,

1992), p. 22.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

142 mcintosh

relational God, stating: ‘Because Christianity is the religion of the triune God,

it is pre-eminently a religion of communication’.31 Evidently, today’s society is

information and technology based with several reports claiming that couples

spend more time on their smartphones than in personal conversation.32 Thus,

if the church is to be effective in communicating its message, it must engage

with the contemporary culture by using new media. Nevertheless, it is not

sufficient to appoint a technologically-skilled individual; the different forms

of offline and online communication employed by the church need to come

together to form a common vision and to avoid unnecessary duplication and

inconsistency.

Social networking media sites, such as Facebook—which took only nine

months to reach 100 million users,33 and has been the largest social network-

ing site since 200834—do have a role in contemporary communication, but

their primary focus is relationship management. Alternatively, blogs and

microblogs, such as Twitter—‘the ninth most popular site in the world’35—are

better at capturing shared interests. On Twitter religious communication can

spread with previously unimaginable rapidity through retweets and the use of

hashtags to flag and group themed posts. For example, when ordinand Adam

Walker Cleaveland set his followers (tweeps) the task of composing a state-

ment of faith in less than 140 characters, using the hashtag #TOF (Twitter of

Faith) the thread went viral within days.36 Similarly, #pray4 enables instant

communication of prayer requests and, for the tweeter, an imagined (in the

sense that it cannot be seen) community of people praying.

Rick Warren, founder of conservative megachurch (Saddleback Church)

in California is a prolific tweeter and has amassed over 300,000 Twitter

31 Ibid.

32 See, for example, Jonathan Freedland, ‘Are Smartphones Causing a Bonking Crisis?’, The

Guardian, 26 November 2013; Carolyn Gregoire, ‘Too Much Texting Could be Harming

Your Love Life, Study Finds’, Huffington Post, 11 January 2014; Richard Alleyne, ‘Mobile

Phone Addiction Ruining Relationships’, The Telegraph, 30 November 2012.

33 See Gelfgren, ‘“Let There be Digital Networks and God Will Provide Growth?”’, in Cheong,

Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, at p. 234.

34 See Johns, ‘Voting “Present”’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital

Religion, Social Media and Culture, at p. 152.

35 Pauline Hope Cheong, ‘Twitter of Faith: Understanding Social Media New Working and

Microblogging Rituals as Religious Practices’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and

Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, pp. 191–206 at p. 191.

36 See ibid., p. 194.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 143

followers.37 His success as a microblogger is based on his ability to write pro-

vocative sound-bites (such as: ‘Have you noticed that everyone who favours

abortion is alive?’)38 that are speedily and repeatedly retweeted. Other inno-

vative uses of Twitter for faith-oriented communication include the Passion

Play of Wall Street’s Trinity Church in New York: over several hours on Good

Friday followers received tweets from Jesus, Peter, Pontius Pilate, Mary, Joseph

and so on.39

At its best, therefore, it seems that new media enables fast, creative and

far-reaching communication that may revitalize shared religious views; at its

worst, though, it encourages narcissism and is used to spread militant and

fundamentalist opinions. Abusive posts have forced many churches to shut

down open ‘walls’ and to exert tighter controls over the interactive features of

Web 2.0 technology.40 During the unusually lengthy period of wintry weather

in the first few months of 2013, several media reports circulated sharing the

news that Reverend Isaac Poobalan of St John’s Episcopal Church in Aberdeen,

Scotland had invited Muslims to come into the church building for their

prayers. Reverend Poobalan had seen the Muslims praying barefoot in the frost,

because the Crown Street Mosque around the corner from the church was too

small to hold them all. Yet, almost as soon as the news was shared, Reverend

Poobalan revealed that he was being abused on the church’s Facebook page, by

Christians who disapproved of his actions.41

Hence, digital communication is not enough in itself; communication that

takes Trinitarian relational theology seriously needs to focus on building and

sustaining community, not merely on sharing information.

37 See ibid., p. 199.

38 @RickWarren 4:06pm, 6 December 2010, as cited by Cheong, ‘Twitter of Faith’, in Cheong,

Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, at p. 200.

39 See Cheong, ‘Twitter of Faith’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital

Religion, Social Media and Culture, at p. 200.

40 For example, the Roman Catholic Church removed the comment feature from the Vatican

YouTube channel and the coordinator of ‘The Bible’ Facebook page closed its open wall

after a ‘vicious and sustained’ attack (see Gelfgren, ‘“Let There be Digital Networks and

God Will Provide Growth?”’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital

Religion, Social Media and Culture, at pp. 236–7).

41 See Julian Bond, ‘Facebook teaches us many things, but not necessarily how to be loving

towards each other’ (22 March 2013), <http://www.christianmuslimforum.org/index.php/

news/175-facebook-teaches-us-many-things> [accessed 26 January 2014]. Rev Poobalan’s

actions were also reported on the BBC and in the Guardian, and the trolls were also

reported on Huffington Post.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

144 mcintosh

Community—Online and Offline

We might wonder, then, how we are to define ‘community’ in the digital age,

since it is not confined to face-to-face interaction and the notion of ubuntu.

Wagner states that online social networking ‘is a pervasive form of connection,

at least potentially capable of nurturing relationships and creating a sense of

community’.42 She goes on to claim that the move from merely networking to

achieving a sense of community is to be found in the users’ levels of ‘emotional

investment and commitment’.43 On the one hand, a user may well experience

a greater sense of connectedness sitting alone at their computer screen and

logging in to discussions and groups to which they feel a deep attachment than

sitting in a church full of people with whom they feel little connection. On

the other hand, the user may be communicating with sophisticated ‘chat-bots’

without realizing that there are no real persons behind the profiles and avatars.

Consequently, it is not surprising that, for Graham Ward, for example, the

possibility of virtual community represents a lamentable shift towards a less

embodied Christian community.44 Alternatively, though, in a somewhat con-

tentious article published in 2012, Nicholas Healy argues that even in an offline

context there is no Christian community. He claims that, since Christians could

pass each other on the street and not know that they shared a faith, it does

not make sense to speak of Christian community.45 Furthermore, citing David

Martin, he claims that the Christian ‘emphasis on “community” corresponds to

a shrinkage in the constituency of persons influenced by the church’ and ‘owes

a great deal to a middle-class nostalgia about lost community’.46

As we have already noted, the influence of mainstream churches has been

in steady decline, but Healy seems to be throwing the baby out with the bath

water; after all language is fluid and perhaps we need to reassess the mean-

ing of community in light of the geographical spread and, at times, the ano-

nymity of Christian belief. Further, while some of those who claim that digital

media leads to a loss of community may be driven by ‘middle-class nostalgia’,

there is plenty of sociological evidence that local social cohesion is being

42 Wagner, Godwired, p. 127.

43 Ibid., p. 134.

44 Graham Ward, Cultural Transformation and Religious Practice (Cambridge and New York:

Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 110; Graham Ward, ‘Between Virtue and Virtuality’,

Theology Today, 59:1 (2002), 55–70.

45 Nicholas M. Healy, ‘Why There is No Christian Community’, Christian Century (16 May

2012), 26–31 at 28.

46 Ibid., 27.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 145

eroded, as Hogan and Wellman state: ‘Communities—both in the flesh and

in the ether—are far-flung, loosely bounded, sparsely knit, and fragmentary.

Most people operate in multiple partial communities as they deal with shift-

ing, amorphous networks of kin, neighbors, friends, workmates, and organiza-

tional ties’.47 Nevertheless, online activity can enhance a sense of community

by reinvigorating dated religious practice, promoting religious activities and

rendering religious faith more credible today.48 We should not abandon the

term community then, but, as Hutchings suggests, we need a new understand-

ing of authentic community that incorporates self-constructed networks.49

Part of the debate surrounding online community is bound up with the

notion of friendship. It is easy to claim, on the one hand, that Facebook has

rendered the term ‘friend’ devoid of meaning, because Facebook users can

collect ‘friends’ at the click of a button, ‘friends’ who may be mere acquain-

tances or may even be people they have never met. According to the US-based

Pew Research Center’s project on ‘Teens and Technology’, the average number

of ‘friends’ on a teenager’s Facebook account as reported in May last year is

around three hundred.50

On the other hand, social networking media has made it much easier to

rekindle and maintain deep friendships with historical friends, with whom we

may have lost touch, due to geographical distance and the passage of time,

and with whom we may have very little face-to-face contact. Similarly, for large

or emerging churches, Facebook can connect ordained leaders with their

church members and thus assist in maintaining a sense of community. As one

Danish Pastor explains: ‘Meeting more than one hundred church attendants

in church every Sunday, it is impossible to talk to everyone in person, but the

Facebook interaction during the week can compensate for this’.51

47 Bernie Hogan and Barry Wellman, ‘The Immanent Internet Redux’, in Cheong, Fischer-

Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, pp. 43–62 at pp.

55–6.

48 See Heidi A. Campbell, When Religion Meets New Media (Abingdon and New York:

Routledge, 2010), p. 38.

49 Tim Hutchings, ‘Creating Church Online: Networks and Collectives in Contemporary

Christianity’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social

Media and Culture, pp. 207–23 at p. 221.

50 Pew Internet and American Life Project, ‘Teens: Median Number of Facebook Friends’

(21 May 2013), Pew Research Center, <http://www.pewinternet.org/Infographics/2013/

Teens-Median-number-of-Facebook-friends.aspx> [accessed 23 August 2013].

51 Stine Lomborg and Charles Ess, ‘ “Keeping the Line Open and Warm”: An Activist Danish

Church and Its Presence on Facebook’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds,

Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, pp. 169–90 at p. 178.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

146 mcintosh

Hence, the ability to share our lives over the internet makes it possible to

know more about each other even when we do not see one another, so that

when/if we do meet in person, we do not meet as strangers. Nevertheless,

I believe there is still a distinction to be made between knowing about someone

and actually knowing them, the latter of which only comes from spending

time together.

Virtual Church

In conjunction with social networking media, we also need to assess ‘commu-

nity’ among the varied instances of online church. At first glance, the increas-

ing number of online churches presents a particular challenge for parishes

that have previously been centred around a church building, and for religious

practitioners who have a real and a theological attachment to a physical build-

ing. As Richard Vosko states: ‘One of the most tangible expressions of faith is

religious architecture . . . diverse sacred places serve as avenues to the experi-

ence of the holy’.52 It does seem to be true that no matter how well a virtual

church is constructed, no matter how accurately it depicts, for example, an

actual cathedral, no matter how cleverly it employs the latest 3D technology,

the simple absence of scale that is necessary for the building to appear on a

smartphone or computer screen will result in a diminished encounter with the

architecture of that building, and in many cases that may mean the loss of awe

and wonder that is akin to an experience of the holy. (Although the technology

may be awe-inspiring in a different way.)53

Nevertheless, this is not a criticism that is solely applied to the virtual

church; it has also been levelled at modern church buildings. Likewise, a vari-

ety of modern worship styles, when compared with traditional liturgies and

hymns, have been accused of reducing the capacity for reverence; as has the

use of the vernacular instead of Latin, and reading from modern versions of

the Bible instead of from the Authorised King James version. Yet, with each of

these developments the argument in favour of change claimed that out of date

symbolism, rituals and language alienated the people it was meant to serve and

52 Richard S. Vosko, ‘Liturgical Technology, Social Media, and the Green Church’, Liturgical

Ministry, 20 (2011), 87–92 at 87.

53 While a sense of amazement may ensue from technologically created digital worlds, it is

a sense of awe at human ability rather than a sense of our smallness and insignificance in

relation to a bigger picture; although that too gives some an experience of the holy, it may

equally result in an overinflated view of human importance.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 147

obscured the meaning it had once conveyed. Thus, in response to the claim

that the increasing use of technology results in a ‘theologically light’ delivery

of the Christian message, Vosko suggests that it is, at least, better at capturing

the imagination of the contemporary audience, and ‘foster[ing] more partici-

pation by congregation members by engaging more of their senses’.54 With live

streaming, the ‘congregation is no longer confined to one meeting place; it now

exists virtually everywhere’,55 and the church leader has to imagine the audi-

ence s/he is addressing. Despite the possibilities, Vosko cautions, simulcasting

of a church service ‘does not seem appropriate in churches that promote inter-

personal relationships with God and other human beings’.56

With the aim of participation in mind, the Church of England has offi-

cially sanctioned an i-church, currently led by Priest Pam Smith, as part of

the Diocese of Oxford.57 Real names have to be used when joining i-church

to enhance the notion of getting to know the other members, in contrast with

the experience of the first 3D online church, Church of Fools, founded by

Methodists in the UK in 2004, which invited the use of avatars but was plagued

by trolls. While i-church employs a traditional understanding of community,

namely one that limits the size of its membership and maintains local interac-

tion, it has experienced pressure to accept global participants.58 Alternatively,

LifeChurch.tv’s Church Online has a much looser definition of community

and favours the broadest reach; in fact, it has invested in Google AdWords so

that typing pornographic terms into a web browser’s search engine will cause

the church’s advertisements to pop-up.59 Moreover, the free 3D virtual world

‘Second Life’ includes an Anglican Cathedral, where, since 2007, avatars can

take part in religious services, and for which Mark Brown, known in Second

Life as Arkin Ariantho, was ordained. He was ordained specifically for carrying

out virtual ministry before he was ordained in the real world in New Zealand

and could conduct a service in a physical church building.60 Despite this ordi-

nation discrepancy, the seeking of Church of England approval for Anglican

services in Second Life denotes the seriousness with which services in Second

Life are regarded by their ministerial team: they hold that this is real ministry

54 Vosko, ‘Liturgical Technology, Social Media, and the Green Church’, at 89.

55 Ibid., 91.

56 Ibid., 90.

57 Campbell, When Religion Meets New Media, p. 141 and p. 124.

58 See Hutchings, ‘Creating Church Online’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess,

eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, at p. 211.

59 Ibid., p. 212.

60 Campbell, When Religion Meets New Media, p. 126.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

148 mcintosh

and real church.61 (Mark/Arkin retired from leadership of Anglicans in Second

Life in 2009, but is still involved in the ministry team in an advisory capacity).

Interestingly, Jørgen Straarup suggests that avatar religion, while avant-

garde, should be viewed positively as a ‘turn towards community’.62 That is,

while the agent who sends his/her avatar on a religious journey may be moti-

vated by real world loneliness and/or disappointment with real world religion,

in embarking on a virtual religious quest, s/he ‘may identify a road or path

back to community’.63 Furthermore, if we feel uncomfortable with the notion

of worshipping as avatars, Schnekloth forces us to consider whether we have

justifiable grounds for feeling so.64 He questions whether the activities that

take place in an online prayer chapel are any less significant than prayers in a

physical building, and he implies that the activities are not even diminished

if the online gathering is conducted by avatars in Second Life.65 Since, as we

have mentioned, all church services rely on a mediated message—mediated

through the church leader and the sacraments—there is a sense in which the

Christian message is always virtual. Similarly, Ellen Charry argues that the

notion of salvation is like a virtual identity, and one that allows the bearer to

escape the social confines and the pervasiveness of consumerism that domi-

nate everyday life.66 Considered in this way, the dichotomy between the virtual

church and the real church is reduced: the church is always engaged in mediat-

ing a virtual message, but with web-based mediation both the mediator and

the message are virtual.

The Moral Imperative of Digital Media

Positively, online churches allow for greater social inclusion, emotional sup-

port and accessibility for those who are housebound or who have not been

welcomed in a physical church but wish to engage in religious activities and be

61 See, for example, Helene Milena, ‘Proposed Constitution of AoSL’, The Anglican Cathedral

of Second Life, <http://slangcath.wordpress.com/2010/07/13/proposed-constitution-

of-aosl/> [accessed 21 October 2014]. Mark Brown’s virtual services can be accessed at

<http://slangcath.wordpress.com/author/bsnzceo/> [accessed 21 October 2014].

62 Jørgen Straarup, ‘When Pinocchio Goes to Church: Exploring an Avatar Religion’, in

Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture,

pp. 97–111 at p. 97.

63 Ibid., at p. 106.

64 Schnekloth, ‘Virtual Church’, at 245.

65 Ibid., 246.

66 Ellen Charry, ‘Virtual Salvation’, Theology Today, 61:3 (2004), 334–46.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 149

part of a religious community. In its favour, logging in from home gives users

the ability to apply individual settings for their comfort and ease of use; it also

allows users to join a variety of religious networks and construct a multifaceted

religious identity. In addition, freedom from physical buildings reduces costs

and enables diasporic communities to stay connected.

Clearly members of online churches do have a sense of community, but we

need to ask whether a sense of community is sufficient to constitute commu-

nity. While religion in the virtual world has the opportunity to interact with

the secular, to be more open and less hierarchical than traditional church and

to capture a sense of being a global community, it runs the risk of being poorly

represented by participants posting on open forums and blogs. Pseudonymous

posts may have a liberating effect for those who are otherwise stigmatized

or silenced, but such posts may be incoherent, unhelpful or insulting. When

church leaders are seen to control posts, however, dialogue decreases and par-

ticipation is undermined. Similarly, while virtual worship is less demanding

than traditional church, since it does not require regular commitment or even

explicit beliefs, it may fail to challenge problematic views or to make connec-

tions between online activity and offline action. In short, online religion has

many benefits, but these come with significant drawbacks also. Mark Brown

may have been fulfilling a need by performing religious rituals in Second Life,

just as blogging may fulfil a human need to communicate, but the possibility

of anonymity and false identities, such as meeting as avatars, begs the question

as to whether genuine community can be found this way. Indeed, Hutchings’

research reveals that: ‘Successful long-term, high-commitment fellowship

groups . . . created online . . . remain rare’.67

More positively, Horsfield argues that virtual worlds are a safe place in which

to explore alternative realities and express hope.68 In fact, in keeping with

Schnekloth and Charry’s arguments on the virtuality of the Christian message,

Horsfield notes that Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech is an expres-

sion of a virtual reality, a vision of a transformed society in which there is

racial equality.69 On this basis, Horsfield suggests that assessment of the virtual

should be asking whether it is mere escapism or whether it is transforming the

actual world in positive ways.70 From the perspective of Trinitarian theology,

67 Hutchings, ‘Creating Church Online’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds,

Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, at p. 214.

68 Peter Horsfield, ‘Theology as a Virtualising Enterprise’, Colloquium, 37:2 (2005), 131–42

at 137.

69 Ibid., 137–8.

70 Ibid., 140.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

150 mcintosh

then, such transformation would mean that relationships are nurtured and

communication is enriched. Yet, digital media encourages objectification and

voyeurism; it makes it easy to seek and store information about others with-

out interacting with them personally. Further, as Lynne Baab notes, from the

perspective of Trinitarian theology, ‘sin’ is that which damages relationships,

which, in the context of the internet includes activity that disregards the dig-

nity and worth of the self or of others, either by posting self-absorbed and dis-

paraging comments or by posting threatening and offensive comments.71

Indeed, given the recent examples of woman-hating Twitter ‘trolls’ mak-

ing rape threats using fake ‘handles’ (names) and teenage suicides linked to

anonymous cyberbullying (even though there is insufficient evidence to prove

that cyberbullying is worse than playground bullying), any use religious com-

munities make of social media needs both to emphasize responsible use and

to challenge dehumanizing behaviour.72 As well as Twitter trolls, digital media

has enabled the promotion of stereotypical and distorted images of Islam and

the publication of invasive and personal photographs on the internet. We need

to ask, as Mary Hess does: ‘How might we reshape our practices . . . so that we

can enjoy the ways in which we can learn and grow with these media but also

challenge the more problematic or even destructive elements of “life lived with

a screen”?’73 In brief, we need an ethics of communication that incorporates

cyber ethics and seeks to uphold the moral claims of self and others.

We cannot simply retreat from digital media: the virtual world is here

to stay. Indeed, for those who have access to the technology (which in 2011

was 29% of the world’s population or 2 billion people),74 especially mobile

access through smartphones and portable computers, a strict division of real

and virtual worlds is no longer possible. Rather, life online is an extension of

life offline; human experience is being mediated through Facebook, Twitter,

71 Lynne M. Baab, ‘Toward a Theology of the Internet: Place, Relationship, and Sin’, in

Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture,

pp. 277–91 at pp. 286–8.

72 See, for example, Sam Jones, ‘Labour MP Stella Creasy Receives Twitter Rape Threats’, The

Guardian, 29 July 2013, <http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/jul/29/labour-

mp-stella-creasy-twitter-rape-threats> [accessed 23 August 2013]; Amanda Lenhardt,

‘British Teen’s Suicide Puts Cyber-Bullying Back in the Spotlight’ (21 August 2013), Pew

Research Center, <http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/08/21/british-teens-

suicide-puts-cyber-bullying-back-in-spotlight/> [accessed 23 August 2013].

73 Mary Hess, ‘Life On Screen and Other Musings on Faith, Food, and Media’, Word and

World, 32:3 (2012), 252–8 at 253.

74 See Cheong and Ess, ‘Introduction’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds,

Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, at p. 8.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

belonging without believing 151

Tumblr, Instagram and so on. As Knut Lundby asserts, the internet is ‘interwo-

ven into the fabric of everyday life’.75

It makes sense, therefore, for the church, as a social movement, to perform

its rituals where the people are, namely, on the internet. Drawing on Harald

Hegstad’s assertion that ‘the “real church” is not the one defined by theologi-

cal dogma but rather the empirical church, the community people experience

when they gather in the name of Jesus, with its hopes and faults’,76 Lundby

claims that ‘the virtual experience is part of the empirical “real” church’,

and, thus: ‘[t]he quality of church in virtual space and on the internet depends

on the relevance and credibility of its ongoing day-to-day interactions in

that realm’.77

I would argue, though, that the church’s online credibility depends at least

as much upon its interactions in the real world and on whether its virtual activ-

ity adds to those actions. A cyberchurch is, at most, a superficial community;

if we are to value others as ends in themselves rather than as means to our

ends, we need to offer practical help as well as emotional support, and to do

that we need face-to-face community. An ethical approach to internet activ-

ity, then, would prioritize flesh and blood relationships over cyber-relations.

Such a prioritizing would not only oppose the objectification of self and others

on the internet, it would also oppose the addictive and compulsive behaviour

that devotes more time to checking for updates and accumulating ‘likes’ and

retweets than it gives to personal conversation with family and friends. Our

online connectivity should exhibit the same respect for persons and relation-

ships that we aim towards in our offline interactions with others.

Belonging without Believing—Online and Offline

At its best, then, the virtual world allows churches to be less institutional

and hierarchical, resulting in greater democracy and dialogue. On the con-

trary, though, Fischer-Nielsen and Gelfgren’s research concludes that Web 2.0

75 Knut Lundby, ‘Dreams of Church in Cyberspace’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren

and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, pp. 25–41 at p. 32.

76 H. Hegstad, Den virkelige kirke. Bidrag til ekklesiologien (Trondheim: Tapir Akademiske

Forlag, 2009), p. 197), as cited by Lundby, ‘Dreams of Church in Cyberspace’, in Cheong,

Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess, eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, at p. 37

(original italics).

77 Lundby, ‘Dreams of Church in Cyberspace’, in Cheong, Fischer-Nielsen, Gelfgren and Ess,

eds, Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture, p. 37.

International Journal of Public Theology 9 (2015) 131–155

152 mcintosh

technology has increased fragmentation and narrow-mindedness instead

of cultivating diversity and interreligious fellowship.78 Users are encouraged

to seek out websites that reinforce the views they hold already rather than

those that will challenge, critique and develop their beliefs. Christian groups

promote websites that are managed by like-minded Christians for other like-

minded Christians. Thus, by asserting an exclusively defined shared identity,

sectarianism is strengthened. In essence, doctrinal distinction is divisive and

inhibits community in both offline and online contexts.

On the one hand, then, with the relative ease of creating and broadcasting

posts, podcasts, discussions and streaming, digital media can be used to sup-

port self-obsession and to promote xenophobia and terrorism.79 Yet, on the

other hand, if a person’s real church is a megachurch with more than two thou-

sand members, social networking media may do more to integrate members

into the community than gatherings in the physical building. According to

Asamoah-Gyadu: ‘This [megachurch] perception of community goes against

the grain of conventional thinking that communities must be kept to man-