Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Design Principles For Competence Management Systems - A Synthesis of An Action Research Study

Design Principles For Competence Management Systems - A Synthesis of An Action Research Study

Uploaded by

Jéssica SilvérioOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Design Principles For Competence Management Systems - A Synthesis of An Action Research Study

Design Principles For Competence Management Systems - A Synthesis of An Action Research Study

Uploaded by

Jéssica SilvérioCopyright:

Available Formats

Lindgren et al.

/Competence Management Systems

SPECIAL ISSUE

DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR COMPETENCE

MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS: A SYNTHESIS

1

OF AN ACTION RESEARCH STUDY

By: Rikard Lindgren Abstract

Viktoria Institute

Hörselgången 4 Even though the literature on competence in

417 56 Göteborg organizations recognizes the need to align organi-

SWEDEN zation level core competence with individual level

rikard.lindgren@viktoria.se job competence, it does not consider the role of

information technology in managing competence

Ola Henfridsson across the macro and micro levels. To address

Viktoria Institute this shortcoming, we embarked on an action

Hörselgången 4 research study that develops and tests design

417 56 Göteborg principles for competence management systems.

SWEDEN This research develops an integrative model of

competence that not only outlines the interaction

ola.henfridsson@viktoria.se

between organizational and individual level com-

petence and the role of technology in this process,

Ulrike Schultze

but also incorporates a typology of competence

Cox School of Business

(competence-in-stock, competence-in-use, and

Southern Methodist University

competence-in-the-making). Six Swedish organi-

P. O. Box 750333

zations participated in our research project, which

Dallas, TX 75275-0333

took 30 months and consisted of two action

U.S.A. research cycles involving numerous data collection

uschultz@mail.cox.smu.edu strategies and interventions such as prototypes.

In addition to developing a set of design principles

and considering their implications for both

research and practice, this article includes a self-

assessment of the study by evaluating it according

to the criteria for canonical action research.

Keywords: Canonical action research, compe-

tence management systems, core competence,

1

Michael Myers was the accepting senior editor for this

design principles, HR management, prototypes,

paper. skill-based approach

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 435-472/September 2004 435

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Introduction he/she is to achieve high performance in the

completion of a task (Boyatzis 1982).

The concept of core competence advanced by

Prahalad and Hamel (1990) has not only re- Given the recognition that organizational core

oriented the field of strategic management toward competence is dependent on and inextricably

a focus on organizational processes and structures intertwined with individuals’ job competence, there

that produce competitive advantage, but has also has been considerable effort in the literature to

prompted many organizations throughout the world bridge the macro and micro levels of analysis (e.g.,

including those in the United Kingdom and the Muffatto 1998; Nordhaug 1998; Rothwell and

United States to identify and develop their own Lindholm 1999; Simpson 2002). These efforts

core competencies (Scarbrough 1998). Core com- point out that HR systems (processes, policies,

petencies are defined as the collective knowledge and technologies) need to be aligned with the

and capabilities that are embedded in the organization’s strategy (Hagan 1996). Lado and

organization; they are central determinants of the Wilson (1994) explicitly highlight the possibility that

organization’s competitiveness due to their HR systems can damage the organization’s com-

centrality to customer value, their resistance to petitive advantage by inhibiting the mobilization of

imitation and their ability to extend to new business new or the exploitation of existing competencies.

applications (Hamel and Prahalad 1994). The For instance, HR systems designed to achieve

core competence perspective of strategic manage- goals such as stability, predictability, and effi-

ment reflects the resource-based view of the ciency, which are typically associated with

organization (von Krogh and Roos 1995), which bureaucratic modes of organizing, are likely to

argues that an organization’s competitive advan- generate core rigidities (Leonard-Barton 1992) and

tage derives from the valuable, rare, and inimitable unmotivated employees (Morgan 1986).

resources that it can marshal (Barney 1991). With

its focus on organizational knowledge as a key Despite this prior research on the danger of mis-

strategic resource, the resource-based view in aligned HR systems, there appear to be no studies

general, and the core competence perspective in on competence management technologies, that is,

particular, is well-suited to strategy formulation and information systems specifically designed to help

management in knowledge-intensive organizations organizations manage competence, both at the

(Conner and Prahalad 1996). individual and organizational level. Given the

importance of information technology (IT) in

Competence management involves the speci- providing a common platform for competence

fication of an organization’s competence needs, management in such organizations (Alavi and

the identification of competence gaps (between Leidner 2001; Andreu and Ciborra 1996; Daven-

needed and actual competence), competence port and Prusak 1998), we regard this lack of

sourcing, competence development through research a considerable shortcoming, especially in

training and coaching, and the staffing of projects light of the strategic role that knowledge and

(Baladi 1999). While determining the organi- competence play in knowledge-intensive organi-

zation’s extant and desired core competencies is zations (Alvesson 1993; Starbuck 1992). The

generally part of strategic management’s macro research we present here is intended to address

focus (Simpson 2002), managing those com- this shortcoming by studying competence

petencies at an operational level is usually the management systems (CMS) with the purpose of

responsibility of human resources (HR) manage- developing and testing design principles that

ment (Bergenhenegouwen et al. 1996). The HR render these systems supportive of knowledge-

discipline typically concerns itself with the concept intensive organizations that are embracing a core

of job competence at the level of the individual, competence approach.

i.e., the micro level (Nordhaug 1998; Simpson

2002). Job competence is defined as possessing Design is central to the information systems

skills that are critical for the individual to master if discipline (Hevner et al. 2004; Markus et al. 2002),

436 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

and the action research method, with its iterative quences of our interventions. We conclude with

hypothesis development and testing, is particularly not only a set of revised design principles, but also

appropriate for the development of system design an assessment of our research vis-à-vis the

principles (Walls et al. 1992). Thus, we conducted criteria for evaluating canonical action research.

a 30-month action research study, which consisted

of two cycles with the following phases: diag-

nosing, action planning, action taking, evaluating,

and specifying learning (Susman and Evered Competence in Organizations

1978). The study involved six Swedish organiza-

tions that also partially funded our project. The The literature on competence in organizations

remaining financial support came from VINNOVA.2 appears to be divided along disciplinary lines. The

strategy literature focuses on the macro or

Due to the long duration of the research and the organizational level of analysis and concerns itself

conditions of our funding, we published insights with the notion of core competence as a means of

and intermediate results at various stages of the generating competitive advantage (Prahalad and

project so as to secure ongoing financial support. Hamel 1990). According to Lado and Wilson

(1994, p. 702), core competencies

These publications reported on CMS imple-

mentation failures (Lindgren and Henfridsson

include all firm-specific assets, knowl-

2002), CMS design assumptions (Lindgren et al.

edge, skills, and capabilities embedded

2003), and CMS design principles (Lindgren and

in the organization’s structure, techno-

Stenmark 2002). The research contribution we

logy, processes and interpersonal (and

offer here goes beyond these earlier publications

intergroup) relationships.

in that our analysis considers the 30-month action

research project in its entirety. We develop an

Thus, at the organizational level, structural fea-

integrative model of competence, a competence

tures such as culture (Barney 1986), routines

typology, and consider the unanticipated conse-

(Nelson and Winter 1982), and learning (Hamel

quences of our design principles for the first time.

and Prahalad 1994) are sources of a firm’s core

We thus synthesize all the steps in our study and,

competence, and hence, its competitive advan-

based on the lessons learned, refine our initial

tage.

design principles.

In contrast, the HR literature focuses more on the

The paper proceeds as follows. First, we review

micro or individual level of analysis and views

the literature on competence and develop a model

competence as “an underlying characteristic of a

that integrates macro and micro level definitions of

person, which results in effective and/or superior

competence and incorporates a typology of com-

performance in a job” (Boyatzis 1982). The per-

petence. This is followed by a method section that

sonal characteristics that facilitate high perfor-

describes action research in general, the criteria

mance (and that are therefore part of individual

by which it should be evaluated, and details about

competence) include motivation, disposition, self-

our particular action research project. Then, we

image, values, moral standards, norms of social

present our two action research cycles. In our

behavior, and traits, as well as communication,

discussion of the research findings, we highlight general reasoning, and learning capabilities

both the anticipated and unanticipated conse- (Bergenhenegouwen et al. 1996; Rothwell and

Lindholm 1999).

2 Given the recognition that macro level com-

Swedish Agency for Innovation Systems, integrates

research and development in technology, transport and petencies are highly dependent on and largely

working life. VINNOVA's mission is to promote sus- embedded in an organization’s human resources

tainable growth by financing R&D and developing (Scarbrough 1998), that is, individual members of

effective innovation systems. For more information, go

to http://www.vinnova.se/. the organization, there are considerable efforts to

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 437

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

integrate these two perspectives on organizational all crucial in an organization that seeks competitive

competence through the development of taxono- advantage through core competencies, are gener-

mies and theoretical frameworks (e.g., Muffatto ally neither acknowledged nor developed in the job

1998; Nordhaug 1998; Rothwell and Lindholm paradigm.

1999; Simpson 2002). Indeed, competence-based

theories of the firm have been developed (San- In contrast, the skill-based approach to HR

chez and Heene 1997; von Krogh and Roos 1995). management focuses on the individual and his/her

ability to contribute to the organization’s core

A number of these integration efforts highlight the competence and competitive advantage (Lawler

need for alignment between the organization’s 1994). Instead of relying on job descriptions, a

strategic orientation and the assumptions under- skill-based approach relies on person descriptions,

lying its HR practices (Bergenhenegouwen et al. which identify the skills and behaviors that an

1996; Lado and Wilson 1994). Hagan (1996) sug- individual needs to be effective in a particular work

gests that an organization’s adoption of a core area. With its emphasis on competence, the skill

competence perspective will require shifts in job paradigm focuses more on behavior than on tasks

and reward system design, as well as in staffing and processes. The skill-based approach is

and training practices. For instance, in a core particularly effective in situations requiring knowl-

competence organization, more work is done in edge and/or team work, as both imply a relatively

project teams and individuals move around the high degree of self-management and the individual

organization to complete different assignments. In worker’s ability to add unique value to products

addition to challenging the individual employee by and services. Furthermore, skill-based remunera-

demanding more effort, flexibility, and motivation in tion systems reward employees for learning and

such a competence-based organization (Bergen- flexibility, and for developing skills that allow them

henegowen et al. 1996), these changes in job to complete multiple tasks.

design challenge the value of job descriptions and

HR practices such as hiring and training that are Lawler and Ledford identify a number of chal-

based on assumptions of more stable jobs and lenges that face organizations wishing to manage

individually-assigned tasks (Lawler 1994). competencies. Shifting from a job-based orienta-

tion to a skill-based one requires significant

Lawler and Ledford (1992) distinguish between change in the physical (e.g., systems and prac-

job-based and skill-based approaches to HR tices) and conceptual (e.g., assumptions and

management, and argue that HR departments beliefs) infrastructure of HR departments. For

need to adopt a skill-based approach in order to instance, the selection of individuals for organi-

support their organizations’ development of core zational membership rather than for a particular

competencies. They highlight that the traditional, job is relatively foreign to organizations that have

job-based approach develops job descriptions and traditionally operated in a top-down, planned

then tries to find and shape individuals to fit them. manner rather than an emergent one. Further-

They contend that this paradigm is problematic in more, organizations will need to invest in new

contemporary organizations because job descrip- technology that supports a skill paradigm (Lawler

tions are generally based on how the organization and Ledford 1992).

has operated in the past, with little or no appre-

ciation for its future needs. Furthermore, the job- Having highlighted the need for alignment among

based approach fails to take into account indivi- the structural features of organizational com-

duals’ abilities to contribute to the organization’s petence, especially between the organization’s

success beyond the boundaries of their job. By strategic orientation and its HR infrastructure, we

incentivizing and evaluating employees within their now turn our attention to individual-level com-

job description boundaries, capabilities such as petence and its development. Individual compe-

learning, flexibility, communication, collaboration, tencies are skills that are critical for individuals to

and innovation across organizational boundaries, master if they are to achieve high performance in

438 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

the completion of a task (Boyatzis 1982). Even element in an individual developing along a career

though knowledge is central to individual com- track is the individual's desire, interest, and

petence (von Krogh and Roos 1995), the concept learning capability” (p. 386). This suggests that, in

of competence couples practice (Bassellier et al. addition to developing competence merely through

2003) and action (Muffatto 1998) with this knowl- the reproduction of past competencies in a

edge component. Furthermore, Sandberg (2000) situated context, individuals are also purposive in

highlights that workers’ own conception of the work their competence development, motivated either

is central to our understanding of competence. by their own competence interests or organi-

zational competence needs. We label this form of

Emphasizing that competence is the enactment of competence competence-in-the-making.

knowledge, Muffatto (1998) suggests that com-

petence is an ongoing accomplishment (also see Informed by the literature reviewed thus far and by

Orlikowski 2002). It is not an object that either an Giddens’ (1984) structuration theory as a way of

individual or an organization owns, but rather a integrating the mutually dependent realm of

continuous process of production and reproduction organizational structure (macro level) and indivi-

(Scarbrough 1998). In this ongoing process, dual action (micro level), we now develop a model

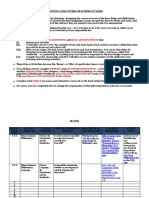

competence plays a dualistic role, serving both as of competence in organizations (see Figure 1).

input to and output of competent action. Kim’s Given our research objective, namely the

(1993) model of learning is helpful in identifying the development of design principles for competence

various components of the competence develop- management technology, we chose Orlikowski’s

ment process at the level of the individual. Kim’s (1992; also, Orlikowski and Robey 1991) adap-

model is made up of two parts: (1) a dynamic tation of structuration theory for our conceptual

learning cycle consisting of the phases of infrastructure as it highlights the role of IT in the

experiential learning (Kolb 1984), i.e., experience, recursive, organizational structuring process.

reflection, abstraction and testing, and (2) memory,

a stock of conceptual frameworks and operational According to structuration theory (Giddens 1984),

routines. Memory is both the source and the the structural properties of social systems (the

destination of the learning process. structure level in Figure 1) are enacted through

recurrent human action and interaction (the

Viewing competence as ongoing accomplishment agency level in Figure 1). Such enactment is

and applying Kim’s model of learning to com- mediated through a number of elements (i.e.,

petence development, we can distinguish between facilities, norms, and interpretive schemes) that

different types of competence. In order to act both enable and constrain human action. Tech-

competently, individuals rely on their stock of com- nology embeds these mediating elements

petence, which is derived from past actions accu- (Orlikowski and Robey 1991). As individuals use

mulated over time. However, as with the use of technology and thereby draw on these mediating

knowledge (Stehr 1994), the use of extant compe- elements (shown as technology mediating be-

tence is not a mere transfer from stock to a speci- tween the structure and agency level in Figure 1),

fic situation or action context. Instead, applying they recursively produce and reproduce the social

stored competence implies a process of re-crea- structures that shape their action.

tion that transforms the competence taken from

stock. As such, the previously accumulated stock Thus, recurrent actions of organizational members

of competence is distinct from competence-in-use. draw not only on extant competence (competence-

in-stock) to generate new competencies, but also

Taking a life-cycle perspective of competence, the on a variety of assumptions, expectations, and

literature not only suggests a past (competence-in- norms embedded in the structural features of the

stock) and a present (competence-in-use) stage of organization, which include core competencies

competence, but also a future stage. For instance, and HR practices (arrow c), and CMS (arrow b).

Lawler and Ledford emphasize that “a critical By applying these mediating elements, organiza-

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 439

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Structure

Organizational Core Competence

• Resources, learning, and routines

• HR orientation (skill-based approach)

Competence Management System

c

a

b

Competent Action

Competence-

Agency

Competence- Competence-

in-Stock in-Use in-the-Making

Individual Competence Interests

Arrow Type of Influence Nature of Influence

a Technology as a product of human CMS as the result of the competent actions taken by system

action designers and developers

b Technology as a medium of human By embedding interpretive schemes, facilities, and norms,

action CMS enable and constrain users’ competent actions

c Institutional conditions of interaction Structural features such as the organization’s core compe-

with technology tence (resources, learning, and routines), as well as con-

ceptual structures (e.g., a skill-based orientation in HR),

define, enable, and constrain individuals’ competent actions

d Institutional consequences of By reinforcing and transforming the systems of signification,

interaction with technology domination, and legitimation, CMS in use shape the core

competencies and other structural features of the

organization

Figure 1. Model of Competence in Organizations (Adapted from W. J. Orlikowski,

“The Duality of Technology: Rethinking the Concept of Technology in Organiza-

tions,” Organization Science (3:3), 1992. Copyright © 1992 INFORMS. The Institute

of Management Sciences, now the Institute for Operations Research and the

Management Sciences, 901 Elkridge Landing Road, Suite 400, Linthicum, Maryland

21090 USA.)

440 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

tional participants create and re-create the core action researcher gains both theoretical and

competencies that characterize the organization’s practical knowledge about the phenomenon.

competitive advantage (arrows a and b).

In addition to generating knowledge through

This structurational perspective on organizational experimenting in a real-world setting, action

competence and its development informed our researchers regard change as an important out-

action research study, which was motivated by our come (Susman and Evered 1978). Merely

quest to develop and test CMS design principles. studying a real-world problem without assisting to

As our integrative model demonstrates, CMS form resolve or ameliorate it is perceived as unhelpful.

part of the mediating structure that facilitates the In other words, action researchers see it as their

smooth interaction between competencies at the responsibility to assist practitioners by not only

macro and micro levels of the organization. In developing but also applying knowledge

order to support organizational competence (Mathiassen 2002).

management in day-to-day action, the design of

CMS must appreciate the reciprocal relationship of Although there are a variety of action research

the three competence types (competence-in-stock, approaches available to IS researchers (Basker-

competence-in-use, competence-in-the-making) ville and Wood-Harper 1998), Susman and

and the organization’s core competencies. Evered’s canonical action research method is one

of the most widely adopted in the social sciences

(Davison et al. 2004). As a canon of action

research, the method formalizes the standards of

this iterative, rigorous, and collaborative research

Method process by describing it in terms of the following

five phases:

Action Research

• Diagnosing refers to the joint (researcher and

Given our objective of developing and testing

practitioner) identification of situated problems

design principles that render CMS supportive of

and their underlying causes. During this

knowledge-intensive organizations with a core phase, researchers and practitioners jointly

competence orientation, we selected action formulate a working hypothesis of the

research as our mode of inquiry. Action research research phenomenon to be used in the sub-

has been described as “a post-positivist social sequent phases of the action research cycle.

scientific research method, ideally suited to the

study of technology in its human context” • Action planning is the process of specifying

(Baskerville and Wood-Harper 1996, p. 235). the actions that can improve the problem

Even though there are other methods for studying situation.

technology in its “natural” context of everyday use,

action research distinguishes itself in that it is • Action taking refers to the implementation of

interventionist and dedicated to the development the intervention specified in the action

of knowledge useful to both research and practice planning phase.

(e.g., Baskerville and Wood-Harper 1996; Susman

and Evered 1978). • Evaluating entails the joint assessment of the

intervention by practitioners and researchers.

As an interventionist method, action research

allows the researcher to test a working hypothesis • Specifying learning denotes the ongoing

about the phenomenon of interest by implementing process of documenting and summing up the

and assessing change in a real-world setting. By learning outcomes of the action research

analyzing discrepancies between the hypothesized cycle. These learning outcomes should con-

and actual changes in the real-world setting or the stitute knowledge contributions to both theory

client-system infrastructure (Susman 1983), the and practice, but they are also recognized as

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 441

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

temporary understandings that serve as the identifying implications for other situations and

starting point for a new cycle of inquiry. research contexts.

To assess the quality of our study, we will later

compare our action research method to these

Evaluation Criteria principles.

Given the variety of action research approaches

available to IS researchers (Baskerville and Wood-

Harper 1998), it is important to specify the criteria Project Setting

by which a research project should be evaluated.

We rely on the evaluation criteria proposed by Our research project was called the Competitive

Davison et al. (2004), as these were developed Knowledge-Intensive Firms project. It was a 30-

specifically for canonical action research. This month (July 1999 to December 2001), colla-

evaluation framework identifies five methodological borative study between the Viktoria Institute

principles, each including a checklist of specific (Göteborg, Sweden) and nine knowledge-intensive

criteria. The five principles are organizations (Astra Zeneca, EHPT [formerly

Ericsson/Hewlett-Packard Telecom], Ericsson

• The principle of researcher-client agreement: Mobile Data Design, Ericsson Microwave, Frontec,

given the importance of collaboration in action Guide, Volvo Car Corporation, Volvo IT, and Volvo

research, this principle seeks to ensure that Truck Corporation). Following Robey and Markus’

researchers and practitioners (clients) (1998) recommendation that practitioner sponsor-

develop a mutual understanding of and ship should be pursued to help overcome the

commitment to the research project, i.e., its commonly perceived rigor and relevance trade-off,

scope, focus, and mode of inquiry. the project was equally funded by the Swedish

research funding agency VINNOVA and the nine

• The principle of the cyclical process model: participating organizations. To avoid any potential

this principle highlights the importance of rigor conflicts over each party’s contribution to and role

in that it advocates progressing through all in the project (see Rapoport 1970), an agreement

five action research phases in a sequential specifying the responsibilities of the Viktoria

and systematic manner. Institute and the participating organizations was

signed. This agreement addressed the allocation

• The principle of theory: seeing that action of resources such as financial support, labor, and

research without theory does not constitute equipment, as well as rights and responsibilities

research, this principle highlights the impor- regarding the research results.

tance of using one or more theories to not

only guide and focus the research activity, but Of the nine organizations included in the overall

also relate the findings to the extant literature. research project, six (EHPT, Frontec, Guide, Volvo

Car Corporation, Volvo IT, and Volvo Truck

• The principle of change through action: since Corporation) participated in our research on CMS.

the purpose of action research is to change All of them fulfilled the criteria of our study in that

an unsatisfactory situation, this principle they (1) represented knowledge-intensive organi-

stipulates that interventions appropriate to the zations that were embracing a core competence

problem and the client organization should be approach and (2) were interested in assessing the

designed and implemented. role of IT in competence management. They were

either evaluating different CMS solutions or had

• The principle of learning through reflection: just acquired a CMS when they agreed to

this principle highlights the importance of participate in our research. The CMS included in

drawing insights from the research and our study ranged from packaged solutions by

442 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

vendors such as Prohunt, SAP, and Tieto Datema showed that they resulted in both anticipated and

to custom-built applications (Frontec’s Compass unanticipated consequences. A summary of our

and Guide’s Competence Marketplace). research project is presented in Table 1.

Research Process

First Action Research Cycle

In our quest to develop design principles that

would make these systems supportive of knowl- With our intent to identify design principles for

edge-intensive organizations that embraced a core CMS, we started our first action research cycle by

competence approach, we started with an investi- investigating our participating organizations’ earlier

gation into the strengths and weaknesses of the attempts at using IT to support competence

technologies upon which our participating organi- management. Their prior IT solutions included in-

zations had relied for managing competencies in house database applications, spreadsheets, and

the past (e.g., spreadsheets, Word documents, Word documents, and they had been only partially

and databases). Based on the shortcomings of successful. The competence descriptions pro-

these desktop-based solutions, we formulated two vided by these systems were inaccurate and

design principles. Since the objective of the first incomplete and therefore of little use in practice.

action research cycle was to work within the A key problem discussed during our workshops

confines of the CMS that our participating with the participating organizations was that the

organizations had selected, we translated these competence descriptions were not updated

design principles into interventions that guided the regularly and were therefore frequently obsolete.

configuration and implementation of CMS.

Another problem concerned inconsistencies in

We followed Susman and Evered’s cyclical action competence descriptions across organizational

research design, and completed the first of two units. While some managers only recorded com-

action research cycles in 4 months (July 1999 to pleted courses, others also included skills acquired

October 1999). During this time, we implemented from project activities. The most ambitious mana-

and assessed our recommendations in the parti- gers combined different information sources and

cipating organization. To our disappointment, the compiled relatively comprehensive competence

evaluation of our interventions highlighted a set of descriptions. For example, some managers at

barriers that hampered the adoption of the CMS as Guide documented their group members’ career

we had envisaged. ambitions.

With an understanding of these adoption barriers We traced the underlying cause of these problems

and a desire to find ways of overcoming them, we to the fragmented nature of the desktop appli-

embarked on a second action research cycle, a cations that the organizations were using. Our

26-month effort (November 1999 to December working hypothesis of the first action research

2001). Instead of working within the confines of cycle was that the problem of inaccurate and

the organizations’ CMS solutions, as we had in our incomplete competence data could be handled by

first action research cycle, we sought to develop using CMS (i.e., information systems specifically

and empirically test a set of design principles by designed to manage competencies in organiza-

implementing them in prototypes. Given the con- tions).

siderable effort required to develop, implement,

and evaluate CMS prototypes, we invited only two In view of the competence data problems related

of our six organizations, namely Volvo IT and to prior IT solutions, the research team and the

Guide, to participate in our second action research practitioners agreed that it was important to use

cycle. Our assessment of the four design prin- these experiences as guidance for configuring and

ciples on which we had built our two prototypes implementing CMS. Since we did not consider

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 443

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Table 1. Summary of Action Research Project

Cycle 1 (July to October 1999) Cycle 2 (November 1999 to December 2001)

Research Sites and CMS

EHPT (Prohunt) Guide (Competence Marketplace)

Guide (Competence Marketplace) Volvo IT (TP/HR)

Frontec (Compass, Prohunt)

Volvo Car Corporation (TP/HR, SAP R/3)

Volvo IT (TP/HR)

Volvo Truck Corporation (TP/HR)

Phase 1. Diagnosing

Over a series of workshops involving all six Based on our understanding of the adoption

organizations, we collected information about barriers identified in the first action research

users’ experiences with various kinds of IT-based cycle, as well as a more in-depth analysis of

competence management solutions (e.g., in- Guide’s and Volvo IT’s CMS, we identified three

house database applications, spreadsheets, and problems associated with the job-based

Word-documents) that were used prior to the assumptions embedded in these systems:

implementation of CMS. We identified poor

quality of competence data as a key problem with • The CMS isolate the individual user from other

these prior solutions. organizational members

• The CMS focus on past competence

We formulated the following working hypothesis: • The CMS are rigid in their reporting of

The problem of inaccurate and incomplete organizational competence

competence data can be resolved by using

systems designed specifically for the purpose of We formulated the following working hypothesis:

managing organizational competencies, i.e., CMS that embody the skills-based paradigm are

CMS. more effective in knowledge-intensive organi-

zations embracing a core competence approach

Data sources than are CMS reflective of the job-based

• Technology review paradigm.

• Workshop sessions

Data sources

Data analysis • Document review

The data collected through the technology review • Participant observation

and the workshops were discussed and analyzed • 22 semi-structured interviews at Guide

in collaborative sessions involving both action • 10 semi-structured interviews at Volvo IT

researchers and practitioners.

Data analysis

Starting with the categories generated in the

evaluation phase of our first action research

cycle, the documents, field notes, and interview

transcripts were analyzed using a more focused

grounded theory approach (Strauss and Corbin

1990). This procedure is known as selective

coding. Our analysis generated the three

problems associated with job-based CMS.

444 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Table 1. Summary of Action Research Project (Continued)

Cycle 1 (July to October 1999) Cycle 2 (November 1999 to December 2001)

Phase 2. Action Planning

In collaboration with representatives of the parti- We developed the Competence Visualizer and

cipating organizations, we developed two design VIP prototypes in accordance with the design

principles for the CMS implementations: principles derived from the skills-based approach

to competence management, namely:

• The principle of balanced competence

descriptions • The principle of transparency

• The principle of user control • The principle of real-time capture

• The principle of interest integration

The design principles were developed to guide • The principle of flexible reporting

the configuration and implementation of CMS in

the six organizations. The prototypes were planned to trigger new

ways of thinking about competence and

competence management among practitioners.

Phase 3. Action Taking

Our two design principles were implemented to • The Competence Visualizer prototype was

varying degrees in the six organizations: demonstrated to Guide users, and users were

given an opportunity to experiment with it

• Frontec and Guide implemented the principle of hands-on.

balanced competence descriptions

• All organizations implemented the principle of • The VIP prototype was installed on Volvo IT’s

user control intranet.

Phase 4. Evaluation

User site investigations were conducted to The Competence Visualizer and VIP prototypes

evaluate the CMS in use. were evaluated to assess the implications of the

four design principles.

Data sources for evaluation

• Focus groups Data sources for evaluation

• Participant observation • 4 focus groups at Guide

• 24 semi-structured interviews (3 interviews were • 2 focus groups at Volvo IT

conducted at each research site, except at • Participant observation

Guide, where 9 interviews were conducted) • 18 semi-structured interviews at Guide

• 16 semi-structured interviews at Volvo IT

Data analysis

The transcribed material was analyzed by using Data analysis

the open and axial coding techniques (Strauss The transcribed material was analyzed using the

and Corbin 1990). This analysis generated a set open, axial, and selective coding techniques

of recurring categories related to competence (Strauss and Corbin 1990). This analysis gener-

mapping, competence visualization, change ated two core categories: design improvements

aspects of competence, competence sharing, and organizational issues. In this analysis, prac-

individual competence development, competence titioners offered comments on and corrections to

gap assessments, and building short-term and our interpretations.

long-term organizational competence. In this

analysis, practitioners offered comments on and

corrections to our interpretations.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 445

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Table 1. Summary of Action Research Project (Continued)

Cycle 1 (July to October 1999) Cycle 2 (November 1999 to December 2001)

Phase 5. Specifying Learning

Our working hypothesis was not supported. Our working hypothesis was partially supported.

Despite our attempts to improve data quality by Our assessment of the prototypes revealed both

implementing CMS guided by the two design anticipated (Lindgren 2003; Lindgren and

principles, the problems remained. On the basis Stenmark 2002; Lindgren et al. 2003) and

of the themes identified in the data analysis, a set unanticipated consequences of these design

of adoption barriers associated with CMS principles. In light of the unanticipated conse-

implementation and use was outlined (Lindgren quences, we developed a set of revised CMS

and Henfridsson 2002): design principles by reflecting on our action

research project in its entirety.

• fragmented representation of competencies

• lack of support for identification of available staff

• competence reproduction bias

• user isolation

• lack of support for knowledge sharing

• insufficient support for group level analysis

• lack of attention to competence interests

• exclusion of strategic planning information

These disappointing outcomes encouraged us to

initiate a second action research cycle.

CMS as turn-key solutions but rather technologies their commitment to and understanding of it (see

that needed to be integrated into a social system Lawler and Ledford 1992). In our role as action

of everyday work, we relied on a series of col- researchers, we therefore initiated and evaluated

laborative workshops (involving practitioners from competence data entry routines for such employee

all six organizations) to outline design principles involvement in all six participating organizations.

that incorporated the lessons learned from the

organizations’ earlier competence management Second, addressing the problem of inconsistencies

solutions. in competence descriptions, we agreed that CMS

should balance formal and informal indicators of

First, tackling the problem of irregularly updated competence in competence descriptions. We refer

competence descriptions, we agreed that user to this as the principle of balanced competence

control is an important prerequisite for keeping descriptions. While formal descriptions of compe-

competence data in CMS up-to-date. Thus, we tence refer to documented knowledge and skills

formulated the design principle of user control, acquired and rated through official channels (e.g.,

which specifies that knowledge workers whose attending training courses or earning a degree),

competencies were captured and stored in CMS informal descriptions of competence refer to on-

would have control over their information. Rather the-job experiences, interests, personal charac-

than having the responsible manager enter the teristics, and behaviors. This principle specifies

competence data, individual knowledge workers that the formal and informal aspects of compe-

should be able to update their own competence tence complement each other and together

information. We reasoned that employees’ active provide a more holistic representation of individual

involvement in managing CMS would increase and organizational competence. For instance, the

446 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

formal competence indicator that an individual unable to address a more fundamental problem.

speaks German at an expert level is enriched and We therefore embarked on a second action

contextualized by the additional description that research cycle in order to identify and test CMS

the person lived in Germany for many years.3 design principles outside the confines of existing

CMS.

Even though all of the participating organizations

recognized the value of representing both formal

and informal indicators of competence in their

CMS, they implemented our suggested interven- Second Action Research

tion to varying degrees. This was primarily due to

Cycle

the limitations imposed by the design of their CMS

packages. For instance, Prohunt and SAP R/3 did

In our second action research cycle, we sought to

not include free-text features, thus limiting the

develop and empirically test design principles by

organization’s ability to incorporate informal com-

implementing them in prototypes separate from,

petence descriptions. Therefore, only two organi-

but complementary to, the participating organi-

zations, Frontec and Guide, whose CMS could zations’ CMS. Only two of our research partner

accommodate additional competence descriptions, organizations, Guide and Volvo IT, participated in

implemented our first intervention. this action research cycle. We targeted these two

organizations because they had well-established

At each site, we evaluated the CMS in use. Our competence management practices covering both

evaluation highlighted a number of barriers to the strategies and technologies. In fact, this strength

adoption of the CMS (Lindgren and Henfridsson could be traced to the fact that Guide and Volvo IT

2002). For instance, users indicated that they did invested a larger portion of their revenues in

not want to disclose competencies that they were competence management than the other four

no longer interested in applying or developing. In organizations and as a consequence they had

other words, the CMS stored knowledge workers’ most HR staff dedicated to develop and maintain

extant competencies, which then served as the these practices on an everyday basis. They were

basis for project assignments. Thus, the CMS thus better prepared for engaging in a new action

tended to reproduce competencies (e.g., once a C research cycle requiring intense researcher-

programmer, always a C programmer), causing practitioner collaboration.

users to misrepresent their knowledge and skill.

In addition, we had good access to these organi-

Thus, despite our attempts to improve data quality zations. The general manager of the Viktoria Insti-

by implementing CMS guided by the two design tute had previously served as the chief knowledge

principles, the problems remained. Our working officer at Guide and our contact at Volvo IT was a

hypothesis was not supported. The CMS imple- senior information architect at Volvo IT’s Web

mented and used by the six organizations were Program Center, who was enrolled in the Viktoria

unable to sufficiently solve the problems of Institute’s industrial Ph.D. program. These rela-

inaccurate and incomplete competence data. We tionships increased the likelihood that a second

concluded that we needed deeper and richer and rather lengthy action research cycle could be

insight into what caused these CMS adoption completed successfully.

problems. We suspected that the assumptions

about competence embedded in the CMS had

hampered the success of our interventions. Thus

Diagnosing

our two design principles were isolated solutions

CMS at Guide

3 The Swedish IT consulting organization Guide was

This is an example articulated at one of the workshop

sessions held at Volvo IT. founded in 1988. In 2000, at the time of this study,

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 447

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Figure 2. Competence Categories and Levels in Guide’s CMS

Guide had approximately 800 employees at 10 agement and organizational planning, (2) organi-

offices located in 3 countries. Since 1988, Guide zational development, (3) technology, tools, and

had invested 15 percent of its annual revenues systems, and (4) methods and models. The

into competence development. Of its many system stored an individual’s competencies in

competence-enhancing activities, Guide con- terms of four levels: beginner, some knowledge,

sidered the development of individuals’ compe- experienced, and expert (see Figure 2).

tencies through project assignments the most

important. Guide’s business and group managers

thus endeavored to staff projects in ways that both CMS at Volvo IT

satisfied a customer’s need and the individual

knowledge worker’s competence development With offices in Belgium, Brazil, Great Britain,

objectives. Malaysia, Sweden, and the United States, Volvo IT

is the Volvo Group’s resource and expertise center

In 1999, Guide implemented Competence Market- for IT. At the time of our study, Volvo IT had

place, a system that was intended to facilitate staff approximately 2,500 employees. Some 1,400 of

allocation and competence management. At the these worked in Sweden, with roughly 900 in

heart of the system was a database storing Göteborg, Volvo IT’s global headquarters. As do

descriptions of staff competence levels in areas many large organizations, Volvo IT recognized the

such as client-server technology and project advantage of knowing who within the organization

management. The system organized the different held what expertise. To help manage its network

competencies into four major categories: (1) man- of globally dispersed knowledge workers, Volvo IT

448 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Figure 3. Competence Tree in Volvo IT’s CMS

decided to implement a CMS in June 1999. They taking that involved the individual knowledge

chose TP/HR, an off-the-shelf, modular application worker and his/her manager.

developed by Tieto Datema (Sweden). The focus

of our research was the education/competence

module. Initial Assessment of CMS

In Volvo IT’s implementation of TP/HR, compe- In February 2000, we initiated an intensive 2-

tence was defined in terms of functional and month assessment in both organizations. We

technical skills. Functional skills referred to the identified several problems with their CMS and

work tasks such as systems analysis, develop- traced these to the embedded assumptions

ment, or support. Technical skills referred to reflecting the job-based approach (Lawler and

knowledge of specific programming languages, Ledford 1992). In particular, we identified three

software, or data management tools. Both func- problems.

tional and technical skills were further divided into

subcategories, on which employees were rated on First, the CMS at Guide and Volvo IT isolated the

a 1 (no competence) to 5 (expert competence) individual user from other organizational members.

scale (see Figure 3). Determining individuals’ This reflects the job-based view of work, in which

competence ratings was a collaborative under- competent individuals are assumed to possess the

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 449

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

knowledge and skills to fulfill a job without knowl- about the competence-reproducing mechanism of

edge sharing. In the CMS we studied, individual CMS. These concerns threatened to undermine

users could only see their own competence the accuracy with which users represented their

descriptions, not those of others. The restricted competence:

access to competence information was intended to

limit internal recruiting, but it hampered knowledge In order to avoid assignments in certain

sharing and the ability to leverage internal knowl- areas, I hide competencies that I don’t

edge resources. A project manager at Guide in want to apply.… I’m capable of working in

Göteborg put it as follows: a COBOL project, but I don’t want to do

it. If I express my competence in

Maybe it should be possible to connect COBOL there is an obvious risk that I

this group of people with similar interest have to take on assignments where this

profiles in some way. For instance, mark type of programming skill is needed. So

here [in the system] that I’m a member of my group leader advised me to leave out

this network. Then I have more search COBOL when I filled in my competence

paths and this would make it easier to description.

find knowledgeable colleagues. At pre-

sent, there is no interactive forum for This concern was underscored by an account

exchanging opinions and competence manager at Guide, who highlighted that the

sharing. It is important to make it easier omission of knowledge workers’ interests and

to initiate a dialogue. career objectives in the CMS limited its value:

Similarly, a management consultant at Volvo IT The consultants are interested in having

remarked: the right assignments…[in the Compe-

tence Marketplace system] there is no

The TP/HR system is hierarchically struc- given correspondence between a con-

tured and closed. As an individual you sultant’s competence and wanted work

can see nobody but yourself [in the tasks. Therefore it is important to keep

system]. If I search for competence, the track of existing ability as well as ambi-

system should support me in identifying tion of competence development. If the

the appropriate person. Such features system would handle information about

are missing in the system. Instead, I ambitions and interests there would be

have to talk to someone who is familiar an incentive for the consultants to use

with the employees [and their compe- the system.…The consultants should feel

tencies]. that they are able to influence which

assignments they get by using the

Second, the competence definitions of CMS at system.

Guide and Volvo IT emphasized past competence,

namely knowledge and skills that an individual The sentiment, that incorporating the future

knowledge worker already possessed. As such, dimension of competence was key to improving

the systems were not supportive of learning and the functionality of CMS, was also echoed by a

competence development, both of which are key project manager in Volvo IT:

objectives of organizations pursuing a core com-

petence strategy. The CMS did not cater for It is important that we are able to find and

emerging and future competencies, ignoring take care of people’s interests. Definitely

motivational and behavioral aspects of compe- you perform better if you are interested in

tence. As the following quote from a systems pro- the work-task in question. And surely a

grammer at Guide’s Stockholm office highlights, person’s potential to learn increases

members of the organization were concerned when they find the actual area exciting.

450 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

One of the HR managers at Volvo IT identified The major disadvantage of the system is

another challenge with regard to the CMS’s focus that it is not possible to make compe-

on past competence. He pointed out that in a tence analyses of teams and groups dif-

dynamic and fast-paced environment like IT, main- ferent sizes. The system supports ana-

taining accurate representations of competence lyses on the individual level in an excel-

required a CMS capable of dealing with skills and lent way. But we must be able to use the

knowledge as they evolve: system in order to form a project team

and analyze the total competence level.

Earlier it was easier since there were few So the system needs features facilitating

programming languages. Now the devel- evaluation of groups in different sizes.

opment is so fast. Yes, there are the Moreover, the system should also be

fourth, fifth, and sixth generation. And more flexible with regard to analyses of

individuals change as well…their com- competence status at a certain point in

petencies change over time. time and competence status changes

over time.

Third, the CMS were rigid in their reporting of

Based on our diagnosis of the CMS used in Guide

organizational competencies. The parameters for

and Volvo IT respectively, we concluded that the

competence analyses were limited (e.g., for

problems associated with their extant systems

predefined group sizes and at system-stipulated

could be traced back to a system design that

points of time). Since ad hoc reporting of com-

embraced a job-based approach to competence

petencies for gap analyses, for instance, is

management. Applying Lawler’s (1994) theorizing

increasingly important in volatile business environ-

that a skill-based approach is more conducive to

ments, the rigidity of the reporting functions limited

management of organizational competencies than

the usefulness of the CMS. One project leader at

a job-based approach, we formulated the following

Guide pointed out that the Competence Market-

working hypothesis: CMS that embody the skills-

place was deficient in its support of strategic based paradigm are more effective in knowledge-

planning because reporting focused on micro level intensive organizations embracing a core com-

competencies only: petence orientation than are CMS reflective of the

job-based paradigm.

It’s not sufficient to know the employees’

competencies. You must be able to

manage those competencies in a stra-

tegic way, but [the system] does not Action Planning

contain a complete package. Our inten-

tion is to categorize the activity with Guided by our working hypothesis, we set out to

regard to strategic goals and critical com- develop design principles that would improve the

petencies. At present, however, we can usefulness of CMS in our two participating organi-

merely visualize competencies on an zations. In formulating these design principles, a

individual level by using the system. But process that was completed in collaboration with

we want to manage competence on a, for practitioners from Guide and Volvo IT, we relied

instance, departmental level. When ana- not only on the three problems that we had

lyzing different groups of employees, we identified in the diagnosis phase, but also on the

need [the system] as a management tool three types of competence that we had identified

for the activity. in our integrated model of organizational compe-

tence: competence-in-stock, competence-in-use,

This shortcoming was echoed by a HR manager in and competence-in-the-making. Thus, we devel-

Volvo IT: oped the following four design principles:

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 451

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

• The principle of transparency: CMS should Competence Visualizer, an add-on module to

make competence-in-stock visible and acces- Guide’s Competence Marketplace. The Compe-

sible to the entire organization. This principle tence Visualizer handled flexible analysis and

responds to the problem of CMS limiting the reporting of the organization’s competence-in-

opportunities of knowledge sharing by re- stock, as well as competencies that organization

stricting access to competence data. members expressed interest in developing. The

prototype embraced three of our design principles:

• The principle of real-time capture: CMS transparency, interest integration, and flexible

should track competence-in-use in real time. reporting. We could not implement the principle of

This principle addresses the problem of real-time capture without considerable changes to

inaccurate competence data, which is caused Competence Marketplace.

by a CMS design focusing on past compe-

tence. The principle promises to generate Like Competence Marketplace, our Competence

data about competence as it emerges through Visualizer add-on was based on ASP scripts, an

knowledge work in action. IIS server, and an SQL server. Furthermore, our

prototype mirrored the system and data structures

• The principle of interest integration: CMS of the Competence Marketplace. In other words,

should accommodate a definition of compe- the competence tree and the competence rating

tence that includes individual knowledge schemes in Competence Visualizer were identical

workers’ interests in addition to their extant to those in the Competence Marketplace. How-

competence. This principle facilitates the ever, since the Competence Marketplace system

capture of competence-in-the-making by did not capture data regarding individuals’ interests

accommodating individuals’ interests as an in developing certain competencies, we relied on

indication of the skills and knowledge that test data for our prototype to enable assessment

they are motivated to develop. based on realistic use situations.

• The principle of flexible reporting: CMS As its name suggests, Competence Visualizer

should support ad hoc analyses of the relied on graphical modes of presentation to allow

organization’s competencies, both with regard users to visualize Guide’s competencies-in-stock

to different units of analysis (e.g., individual or and competence interests. Users could view com-

group) and time frames (e.g., from-to dates).

petencies at the individual, group, or organizational

This principle addresses the rigidity in CMS’

level. Furthermore, competencies could be shown

reporting functionality. By providing mana-

as a snapshot view (Figure 4), i.e., single point in

gers with flexible reporting, CMS support

time, as well as across a user-defined time period

strategic competence development by influ-

(Figure 5). These graphical representations were

encing competence-in-the-making.

expected to help users identify patterns and trends

in organizational competence needs.

These four design principles were then applied in

the design of two CMS prototypes. These were

In order to present competence-in-stock and

Guide’s Competence Visualizer and Volvo IT’s

competence interests at the individual and aggre-

Volvo Information Portal (VIP).

gated group or organizational level, Competence

Visualizer assigned numeric values to the descrip-

tive competence ratings in Competence Market-

Action Taking place. A beginner rating was assigned a value of

0.25; some knowledge was 0.5; experienced was

The CMS Prototype at Guide a 1.0; and expert was 1.25. To satisfy the design

principle of flexible reporting, Competence

In collaboration with Guide practitioners and three Visualizer displayed the competencies not only in

M.Sc. students, the first author developed the graphical, but also in tabular form.

452 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Figure 4. Snapshot of Competencies at Guide

In April 2000, the Competence Visualizer was Based on his knowledge on search engines and

demonstrated to Guide users. Our original intent recommender systems, the Volvo Information

was to implement the prototype in Guide so that Portal (VIP) system was developed as a comple-

users could evaluate our system after using it in ment to TP/HR. VIP captured knowledge workers’

their everyday work, but we were unable to do so competence interests in real time and made

due to unforeseeable organizational changes. In competence-in-the-making more transparent. Re-

early 2000, Guide merged with the Internet consul- source constraints did not allow us to implement all

tancy organization Framfab. This meant that four design principles. The VIP prototype em-

Guide’s management was preoccupied with the re- bodied the principles of transparency, real-time

organization following the merger, which made it capture, and interest integration. In this way, each

difficult to move ahead on our implementation of our design principles was covered by at least

plans, particularly as all internal development was one prototype.

put on hold. We thus opted for an alternative

evaluation strategy, which involved workshops and VIP was built on Autonomy’s AgentWare platform,

focus groups with intended Guide users. We a commercially available tool that uses neural

describe our evaluation in more detail later. networks and advanced pattern-matching tech-

niques to find similarities in textual data. VIP

allowed the users to define intelligent agents that

The CMS Prototype at Volvo IT searched an index database for intranet docu-

ments matching the user’s interests. By defining

At the time of this research, one of the members of one or more agents, VIP users were thus able to

our research team was a senior information monitor the corporate intranet for items that

architect at Volvo IT’s Web Program Center. matched their interests. The users defined their

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 453

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Figure 5. Combined Competence Chart at Guide

interests in a free-text natural language format abling knowledge sharing and collaboration across

from which the system then created an internal Volvo IT’s many offices. When invoking this fea-

digital representation. ture, the interest profiles embedded in the user’s

agents were matched with the profiles of all other

The search results from each agent were dis- agents. Matches were displayed, listing the name

played in a simple list similar to those generated and contact information of the identified users.

by search engines. By clicking on the hyperlinks Finally, the VIP prototype supported searches for

generated by the agent, users could retrieve the users with specific interests. VIP users could enter

documents matching their interests. When users a search for an interest in natural-language format

had read and identified one or more of the and VIP would return all users whose agents

returned documents as relevant, they could contained the specified interest. Figure 6 presents

provide the agent with explicit feedback through a VIP’s response to such a search.

retrain feature, which adjusted the agent’s search

criteria based on the characteristics of the In April 2000, VIP was implemented on the Volvo

retrieved document. IT intranet and made available to all intranet users

in Göteborg as part of their everyday work. Fifty

The VIP prototype also provided a community fea- people tried out the prototype when it was first

ture, which allowed users to find other users with introduced and there were twenty users with active

an interest profile similar to their own, thus en- agents at the end of the evaluation period.

454 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Figure 6. Finding a Specific Competence Interest at Volvo IT

Evaluating Stockholm, and Oslo) and comprised approxi-

mately 30 participants in total. During these work-

Evaluating at Guide shops we introduced and demonstrated Com-

petence Visualizer, encouraged users to interact

Due to the merger between Guide and Framfab, with the prototype in its test environment, and then

we relied on an approach that came as close as conducted focus group sessions in which users

possible to an organization-based evaluation discussed their thoughts on and reactions to our

process. Our process consisted of system demon- prototype. Afterward, we interviewed 18 partici-

strations and workshops during which Guide users pants.

could experiment with Competence Visualizer.

Together with the chief technician of Guide's Our evaluation efforts at Guide revealed both

Göteborg office, we made a number of prototype anticipated and unanticipated consequences of our

presentations to Guide users in the Göteborg

prototype. Overall, the prospective user seemed

office. Furthermore, we set up a test environment

to value our prototype’s flexible display of com-

with Competence Marketplace (running real data)

petence-in-stock and competence interests. The

and Competence Visualizer (running test data).

capacity to visualize the competencies of different

Users could experiment with the two applications

groups at (or across) different points in time was

in a hands-on fashion. Over a series of sessions,

considered valuable with regard to competence-in-

HR managers, account managers, and project

managers tried out Competence Visualizer in this stock and competence-in-the-making. For in-

test environment. Afterward we debriefed them to stance, the CEO for Guide in Oslo remarked:

elicit their response to our prototype, e.g., whether

they would find it useful in their work and how it [The Competence Visualizer prototype] is

compared to Competence Marketplace. useful when talking with the employees

about the situation. It is easier to under-

Another evaluation strategy involved four work- stand these charts that show the present

shops, which were held at three sites (Göteborg, situation as well as a future dimension.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004 455

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

Moreover, it is easier to understand what organizations have to explicate and publish their

we mean when we discuss employees’ competence needs in order to stimulate their

opportunities in relation to the organi- development.

zation’s activities.

It’s quite easy to appreciate the value of

Additionally, the interest-integration design prin- this system. It’s really interesting to

ciple was seen as addressing the data accuracy check out the competencies within the

problem that plagued the original CMS. A group organization on a regular basis; be able

manager at Guide’s office in Göteborg used the to find out our strengths and weak-

following example to explain the benefits of nesses. And the interest module indi-

incorporating interest competencies into a CMS: cates what work tasks the employees are

interested in working with. But, then it is

As an example: I have been working our duty to create areas of interest. That

with FORTRAN for 10 years; I’m a really is basically the best approach. In case

good FORTRAN programmer, but I don’t we need 15 experienced project leaders

want to work with it. Then I have re- within the next 12 months, we have to

moved that competence in the system introduce that specific interest to our em-

[Competence Marketplace]. For this rea- ployees. In this way you are able to

son, this interest dimension is good: I’m affect both of the curves [of the Compe-

good at it and I want to work with it, I’m tence Visualizer system]; it’s simply a

good at it, but I’m not interested in matter of marketing.

working with it, and my knowledge is

limited at the moment, but I’m eager to This interview quote highlights that organizational

learn more. competence needs and individual competence

interests cannot be treated independently in a

As this group manager highlighted, Competence CMS that embodies the skill-based paradigm.

Visualizer allowed employees to describe their Instead, managers have to work through indivi-

competence in more comprehensive ways. They duals’ competence interests in order to meet the

were able to express both existing competencies competence development needs of the organiza-

(competence-in-stock) and individual competence tion. This approach to competence development

interests, which drive competence-in-the-making. might prove to be particularly challenging in

Thus, competence interests were not represented situations where employees’ interests are at odds

at the expense of existing competencies, allowing with the organization’s (and its customers’) needs.

Guide to generate a more accurate picture of its

existing and emerging competencies, and to

compare them with its strategic core competence Evaluating at Volvo IT

goals.

After implementing the VIP prototype on Volvo IT’s

In addition to these anticipated consequences of intranet, we initiated a 10-week evaluation with a

our prototype, there were some unanticipated workshop at Volvo IT’s headquarters in Göteborg.

ones. For instance, the objective of our flexible At this workshop, which was attended by depart-

reporting design principle was to highlight compe- ment managers, HR managers, project managers,

tence gaps between existing competencies, system developers, and technicians, we intro-

individuals’ competence interests, and the organi- duced VIP as a complement to TP/HR and des-

zation’s competence needs. As the following inter- cribed its basic features. The workshop partici-

view quote from a Guide group manager high- pants (approximately 30) were then encouraged to

lights, the implication of adopting a skill-based use VIP in their everyday work. After the 10-week

approach to HR management and taking indivi- evaluation period, during which we collected

duals’ competence interests seriously, is that observational data, we interviewed 16 VIP users to

456 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 3/September 2004

Lindgren et al./Competence Management Systems

assess their perceptions of VIP, e.g., its useful- I see [the find users with similar interest

ness in their work and its value with regard to feature] as a very useful feature; as an

competence management. enabler for building networks. It is

interesting to be able to find colleagues

Our assessment revealed that VIP generated both who are interested in the same things.

anticipated and unanticipated consequences. With Because our main problem here is that

regard to anticipated consequences, a number of there are people working with similar

the practitioners remarked on the advantages of things everywhere and you don’t really

VIP’s ability to capture competence and compe- find them.

tence interests in real-time. They noted that the

original CMS contained information on neither In addition to these anticipated consequences of

competence-in-use nor competence-in-the- our design principles as implemented in VIP, our

making, whereas the prototype did. One HR man- evaluation also identified a number of unanti-

ager felt that the VIP prototype represented a “next cipated consequences. For instance, the principle

step” in competence management as it captured of transparency was expected to increase

the tasks for which knowledge workers used their knowledge sharing in the organization. However,

competencies: the feedback from one Volvo IT project manager

highlights that this is only true if the competence a

TP/HR is a lot about order and being in user seeks exists within the CMS:

control of the situation, i.e., to know what

we have and the level of education of our Then you suddenly realize that the topics

employees.…Then this prototype is

searched for are of no interest to others.

something else. It is what people do on

Naturally it is valuable to know that there

an everyday basis. It is what they use

are no organizational members but me

their skills for. It is sort of the next step.

who are interested in these kinds of

issues. Resulting from this, you under-

Several practitioners indicated that the interest-

stand clearly that there is no point to walk

integration design principle implied a future orien-

all over the office trying to find relevant

tation for CMS and they believed that this would

people to talk to.

stimulate competence development. A technology

analyst expressed this in the following way:

Thus, in the event that a competence cannot be

located in the CMS, the system potentially created

Interest is tremendously important for the

disincentives for organizational members to