Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MacNeish, Richard & Antoinette Nelken-Terner - The Preceramic of Mesoamerica.

MacNeish, Richard & Antoinette Nelken-Terner - The Preceramic of Mesoamerica.

Uploaded by

Jesus Eduardo Medina VillalobosOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MacNeish, Richard & Antoinette Nelken-Terner - The Preceramic of Mesoamerica.

MacNeish, Richard & Antoinette Nelken-Terner - The Preceramic of Mesoamerica.

Uploaded by

Jesus Eduardo Medina VillalobosCopyright:

Available Formats

Maney Publishing

The Preceramic of Mesoamerica

Author(s): Richard S. MacNeish and Antoinette Nelken-Terner

Source: Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Spring, 1983), pp. 71-84

Published by: Maney Publishing

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/529749 .

Accessed: 04/02/2015 17:18

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Maney Publishing is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Field

Archaeology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Preceramicof Mesoamerica

Richard S. MacNeish

Boston University

Boston, Massachusetts

and

Robert S. Peabody Foundation for Archaeology

Andover, Massachusetts

Antoinette Nelken-Terner

Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique de France

Mexico City, Mexico

Thispaper is an attemptto summarizeand synthesizethe Preceramic(more

than40,000 years ago to ca. 4,000 B.P. in radiocarbontime)for the major

New Worldculturearea, Mesoamerica.In attemptingto do this, the authors

have dividedthe period into two general stages: EarlyMan, withfour sub-

stages, and Archaic, with threesubstages.Each of these substagesseems to

have some general developmentalcharacteristicsin termsof technology,sub-

sistence, and culturethat are reflectedin their artifactcomplexes.Further-

more, each substageafter thefirst two seems to have more thanone cultural

traditionthat may reflectsome sort of adaptationto naturalareas or eco-

zones. Throughoutthe sequence, there is not only a developmentof more

complextechnologyand subsistencesystems,but more traditionsoccur, so

thatat the thresholdof village-agriculturewith ceramics, thereare two ma-

jor super traditions a highlandone and lowlandone. These two traditions

form the base on whichMesoamericancivilizationwas built.

Introduction Early Man: the Lithic Stage

In discussing the Preceramic period of Mesoamerica, In Mesoamerica,traces of early man are not numer-

it seems advisable from the standpoint of cultural de- ous, and most of them were discoveredduringthe last

velopment to divide this long period into two stages --- 20 years. Nevertheless, there are hints that here also

Early Man, or Lithic, from roughly 9,000 B.P. to as much earlyman went througha series of technologicalstages

as 40,000 years ago and the Archaic from roughly 4,000 thatare relatedto orSare the same as ones that seem to

B.P. in radiocarbon time to the time of the extinction of exist for the rest of the New World.1

the Pleistocene megafauna between 9,000 and 10,000 The earlieststage elsewherecharacterizedby chop-

years ago in radiocarbon time (all dates, since most are ping-choppertools is still almost unknown, and hy-

before 7,000 years ago, are uncorrected). Again we be- potheticallyit shoulddate before 30,000 or 40,000 B.P.

lieve there were developments within each of these large (FIG. 1). It has been suggestedby J. Epsteinthatsome of

general stages with there being four substages of the his earliestfinds fromthe San Isidrosite in Nuevo Leon

Lithic and three of the Archaic. Finds are still meager may belong to this earlieststage,2and perhapsthey do.

for all these substages and more research will better de- 1. Richard S. MacNeish, ''Early Man in the New World," AmSci

fine them or, perhaps, even further subdivide them. We 63:3 (1976) 316-327.

describe here what we understand on the basis of the 2. J. F. Epstein, "The San Isidro site: An early man campsite in

present (1982) evidence, knowing full well that both the Nuevo Leon, Mexico," Anthropological Papers of the University of

evidence and our Wnderstandingwill continue to grow. Texas,No. 1(1969)111-123.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

72 The Preceramic of MesoamericalMacNeish and Nelken-Terner

Figure 1. Sites of the Lithic Stage (Substages1-3). Substage1 (_), chopping-chopper tool assemblagesmore than

30,000 years old: 1) E1Bosque, Nicaragua;2) possiblyearliestSan Isidro(Nuevo Leon);3) possiblythe Diablo

Complex(Tamaulipas);4) possiblyearliestTlapacoya,Mexico (D.F.). Substage2 (A), unifacialbone tool

assemblages,ca. 30,000-15,000 B.P.: 1) earliestValsequillo(Puebla);2) Tlapacoya,Mexico (D.F.); 3) possiblyearliest

SantaMarta(Chiapas);4) possibly earliestLoltunCave (Yucatan);S) possiblyE1Cedral(San Luis Potosi);6) possibly

SantaLucia, Mexico (D.F.). Substage3 (a), leaf bifacialpoint, blades, burinassemblages,ca. 15,000-11,000 B.P.:

1) early Ajuereado,Tehuacan(Puebla,Mexico);2) Unit IE, Hueyatlaco(Puebla);3) next to earliestSantaMarta

(Chiapas);4) possiblyearliestSan Juan,San NicholasCave (Queretaro); S) possiblyzone F of CuevaBlanca, Mitla

(Oaxaca).

They are not in excavatedcontexts, however, nor have some of the basalt and andesite artifacts from various

they been dated. Epstein also suggests that these finds tests on the slopes above Tlapacoya are older (33,500)

arerelatedto the poorlydocumentedDiablo complexof than those dated at 20,000 B.P. and may be of this stage.3

Tamaulipas,which includeda few artifactsin high ter- Unfortunately, if so, there is no documentation in print

race gravels of the CanyonDiablo, indicativeof some of this speculation.

antiquity.But mostof the Diabloartifactsareunifaces- Perhaps more reliably representative of this hypothet-

types characteristicof the second stages and further- ical first stage are the E1 Bosque remains from Nicara-

more,high terracegravelsareprobablyless than30,000- 3. Lorena Mirambell, "E1 Hombre en Tlapacoya desde hace nuos 20

40,000 years old. L. Mirambellhas also suggestedthat mil anos, " Boletin INAH 4 ( 1973) 1 1-14.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field Archaeology/Vol. 10, 1983 73

gua.4Hereat least one pebbleor flakechopperandsome foundin the screen, not in situ. Again, althoughan ad-

workedbone from good context were associatedwith equatedescriptionof these finds has yet to get into print,

bones of extinct sloth (Eremotherium andMegalonychi- ffierewas indisputable associationof man'sunifacialtools

dae), mastodon (Stego mastodon), and horse (Amer- with the bones of extinctanimalssuch as the mammoth,

hippus). Dating these finds, however, presents some mastodon,horse, etc.

problems,as the radiocarbondates range from 18,000 It might be added that there are two other possible

+ 500 B.P. to more than 35,000 B.P.S Only time and examplesof this stage thathave also not been reported.

moreresearchwill tell just how reliablethese finds are One includesthe lower levels of the Santa Martacave

and if they really do representthis first stage. of ChiapaswhereMirambellput in a test thatprevented

Oursecond hypotheticalstage, however, seems to be the seniorauthorfromrediggingit with an NSF grant.9

representedby some fairly reliabledata which dates in Again therewere but a few unifacialtools and no date,

the rangefrom 15,000 to 40,000 years ago (FIG. 1). It is but the stratigraphywas clear: these levels lay under

characterized by bone tools and a unifacialindustryand stratathat dated to 9,000 B.P. The lower levels of this

is best evidencedin good datedcontext at Valsequillo, cave need to be dug once again with the same sensitive

which was excavatedby CynthiaIrwin-Williams.6She techniquesused in the initial testings,10and should, at

found 13 unifacialartifacts,such as points, burins,side that time, producea more adequatelydocumentedex-

scrapers,wedges, end scrapers,andspokeshave-likeob- ampleof StageII. Somewhatsimilararethe lower levels

jects in associationwith extinctanimalsat five locations: of Loltun Cave in Yucatan, where NorbertoGonzales

El Horno, Mirador,Tecacanco, lower Hueyatlacoand found unifacial tools in associationwith bones of the

Caulapan.Furthermore,shell near the flake artifactat extinct horse, mammoth,etc., as well as the pointed

Caulapandated to 21,850 + 850 B.P. (W1895). Juan horse-bonetool at El Cedralin San Luis Potosi datedat

Armenta,workingin the same area, but often at other 21,960 + 540 B.P. (I10436), nine otherpossible pieces

locations,also foundunifacialstone choppersas well as of workedbone, anda possiblescraperplanein a stratum

many bone tools and pieces of workedbone of extinct datedat 33,270 + 1800 B.P. (GX7684). Also, the flakes

animals.7Carbon-14dateson these remainsrangefrom at SantaLucianearLakeZumpangoNW of Mexico City,

23,940 + 1,000 B.P. (W1911) to morethan 35,000 B.P. dated 23,400 + 600 B.P. (I10427) and 26,300 + 880

Althoughthe context of these is not as good as that of B.P. (IX6628), mightbe of this stage.1l

Irwin-Williams'material,there is no denying the fact Thus, Stage II does exist. AlthoughC.V. Haynes12

thatthis culturalcomplex existed at thattime. and D. Stanford13 have theirdoubts,they cannotignore

Whatis more, this Stage II type of artifactoccurs at the facts and wish14these finds out of existence. While

a numberof early sites in otherpartsof Mexico, includ- none of these finds has yieldedlargeinventoriesandthe

ing, in our opinion, the Diablo complex of Tamaulipas stageis ill-defined,therearea numberof sites that,upon

thatwas mentionedabove. The most publicizedof these excavation,will give us bettersamplesof artifactsand

is Tlapacoya,with its datesof 21,700 + 500 B.P. (L449) ecofactsso thatthe whole mattermaybe settledto every-

and 24,000 + 4,000 B.P. (A794).8 Unfortunately,there one's satisfactionshortly.

werefew artifactsfoundin theseearlycomplexes,mainly

andesiteflakes. In fact, one of the most publicizedof 9. JoaquinGarcia,DianaSantamaria,Ticul Alverez, ManuelReyes,

these artifactswas an obsidianblade that was actually and FernandoSanchez,"Excavacionesen E1Abrigode SantaMera,

Chiapas",INAH Dept. de Prehistora Informes, No. 1 (Mexico 1976)

1-21.

4. RuthGruhn,"A note on excavationsat E1Bosque, Nicaraguain 10. RichardS. MacNeishand FrederickA. Peterson, "The Santa

1975," in Early Man in America, A. D. Bryan, ed. (Universityof MartaRock Shelter, Ocozocoautla,Chiapas," Papers of the New

Alberta:Edmonton,Alberta1978) 261-262. World Archaeological Foundation 14 (1962) 1-46.

5. JorgeEspinosa,''ExcavacionesArqueologicasen E1Bosque," In- 11. Jose Luis Lorenzo,"E1Cedral,Mexico, SLP, Mexico-un sitio

Nicaraqua1976)

forme No. 1, InstitutoGeografico Nacional (Manaqua, presenciohumanade mas de 30,000 B.P.," paperat Union Interna-

22-55. X Congress(Mexico

tionalde CienciasPrehistoricus,Protohistoricas,

City 1981) 16-22.

6. C. Irwin-Williams,''Associationof earlyman with horse, camel,

andmastodonatHueyatlaco,Valsequillo(Puebla,Mexico)," in Pleis- 12. C. V. Haynes, "The earliestAmericans,"Science 166 (1969)

tocene Extinctions, P. S. Martin,ed. (Yale UniversityPress:New 709-715.

Haven 1967) 337-347.

13. RobertL. HumphreyandDennisStanford,Pre-Llano cultures of

7. (Camacho)JuanArmenta,''Vestigiosde LaborHumanaen Hueso the Americas: Paradoxes and Possibilities (The AnthropologicalSo-

de AnimalesExtintosde Valsequillo,Puebla,Mexico," Consejo Ed- ciety of Washington:Washington,D .C. 1979) 147- 150.

itorial de Gobierno del Estado de Puebla, Mexico (1978) 1-123.

14. As P. Martin,"The discoveryof America,"Science 179 (1973)

8. Mirambell,loc. cit. (in note 3). 969-974.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and Nelken-Terner

74 The Preceramicof Mesoamerica/MacNeish

In ourschemeof things,the finaltwo EarlyManstages cations are not well understood.Obviously, one impli-

arecharacterized by specializedbifacialprojectilepoints cation is thatthe burinsappearto reflect a new kind of

as well as other tools (see FIG. 6). The first of these is bone or shell industry,but the details of this are still

not well documentedandmightdatebetween10,000 B.P. unknown. Second, the well-made, snub-nosed end

and 15,000 or 20,000 B.P.; it shouldbe characterizedby scrapersandblade scrapersof this stage probablyimply

blades, burins,and leaf-shapedpoints. EarliestAjuere- new skin-workingtechniques. Because of the limited

ado of the TehuacanValley of Puebla,15perhapssome numberof finds, however,andthe lackof in-depthstudy

Lermacomponentsof Tamaulipas,l6Unit 1E of Huey- of what we have found, we are, in fact, certainof very

atlacoof Puebla,17Zone F of CuevaBlancain Oaxaca,18 little aboutthe cultureof this stage, includingwhether

and perhapsthe next to earliest levels of Santa Marta or not therewas a highland-lowlandculturaldichotomy

Cave19may be examplesof this stage. A possible ham- at this time, as our Belizeanand some Guatemalansites

mer from Cedralthat is from a deposit said to date to suggest.24Nevertheless,the ever-increasingfinds of hy-

ca. 15,000 B.P. may also belong to this stage.20 potheticalStage IV, with its numerousregionaladapta-

One salientfeatureof this Stage III is the presenceof tions, had commencedduringStage III.

bifacial leaf-shapedLerma points, althoughobviously In fact, it is only with our final hypotheticalStage IV

this type is not very distinctiveandlasts way beyondthis that we have even a semblanceof an adequateset of

time period (FIG. 1). Whetherfutureresearchwill find artifactsfrom a numberof sites that allows us to hy-

othertypes, such as fluted (:lovis-like,2l Meadowcroft- pothesizeaboutregionaltraditions(FIG. 2). On a general

like,22or Fells (:ave-like23points is unknown,but the level, this finalPreceramicstagehadmanymorespecial-

fact remainsthatin this stage, the firstbifacialpointsdo ized bifacial projectile points Clovis, Agate Basin,

appearand may well reflect not only new lithic manu- Plainview, Golondrina,Lerma, Madden Lake, Fells

factunngtechniques,but also new ways of hunting.Other (:ave, etc. as well as a numberof othertools such as

bifacial tools also occur in this hypotheticalStage III, mullersand milling stones (see FIG. 6) which show that

which also reflectthese new lithic techniques. these people had other subsistenceoptionsbesides big-

Perhapsmore significantfor this stage in terms of game huntingand that they may have had specialized

lithic manufacturing techniquesis the seeminginitiation adaptationsto variousecozonesor environmentalzones.

of the blade-burintechniqueof manufacture.Here is a In spite of these generalities,workingout the details

whole field yet to be adequatelystudied, and its impli- of the traditionsin Mexico at this time is still very dif-

ficult at this stage of our research.In 1966 we thought

therewas only one (Sordilleran.25 By 1974, we thought

15. Richard S. MacNeish, Antoinette Nelken-Terner, and Inngard therewere two, an easternone Planoid-(Sordilleran-

Johnson, The Prehistory of the Tehuacan Valley, Vol. 2, Nonceramic and a western one-Llanoid-Cordilleran26-and now,

Artifacts (University of Texas Press: Austin, Texas 1967) 227-245. with our work in Belize, we see a third-the Fishtail-

16. Richard S. MacNeish, "A synopsis of the archaeological se- pointtradition.27 Whoknowswhattomorrowwill bring?

quence in the Sierra de Tamaulipas," Revista, Mexico de lnstituto In fact, all we can do now is to describe, and in part

Anthropologia XI (Mexico City 1958) 79-96.

repeat,what we have said before.

17 Irwin-Williams, loc . cit. (in note 6) . In terms of representativesof the easterly tradition,

18. Kent V. Flannery, "Preliminary archaeological investigation in the best documentedexampleis the late Ajuereadocom-

the valley of Oaxaca, Mexico," report to the National Science Foun- plex of the TehuacanValleyof east centralMexico, and,

dation, mimeographed (1969) 10-24. althoughno carbon-14datesaredirectlyassociatedwith

19. Joaquin Garcia-Barena, "Una panta acanalaca de le cueva Los it, bracketingdates suggest that it existed roughlyfrom

Grifos Ocozocoautla, Chiapas," Dept. de Prehistoria Cuadernos 17

(Mexico City 1981) 1-19.

20. Lorenzo, op. cit. (in note 11) 121.

24. Richard S MacNeish, S. Jeffrey K. Wilkerson, and Antoinette

21. C. V. Haynes, "Geochronology of man-mammoth sites and their

Nelken-Terner, First Annual Report of the Belize Archaic Archaeo-

bearing on the origin of the Llano complex," Pleistocene and Recent

logical Reconnaissance (Robert S. Peabody Foundation for Archae-

Environment of the Central Great Plains, W. Dort, Jr., ed. (New

ology: Andover, Massachusetts 1980) 27-68.

York City 1970) 83- 111.

25 MacNeish, Nelken-Terner, and Johnson, op. cit. (in note 15)

22 J. M. Adovasio, J. D. Gunn, J. Donahue, and R. Stuckenrath,

334-344.

''Excavations at Meadowcroft Rockshelter, a Progress Report?Penn-

sylvania Archueology 45:3 (1975) 1-93. 26. MacNeish, op. cit. (in note 1) 322-327.

23. J. B. Bird, ''The archaeology of Patagonia," Handbook of South 27. Richard S . MacNeish, Second Annua} Report of the Belize Archaic

American lndians, BHEB 143, J. Steward, ed. (Washington, D.C. Archaeological Reconnaissance (Robert S. Peabody Foundation for

1946) 17-24. Archaeology: Andover, Massachusetts 1981) 26-72.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field Archaeologyl Vol. 10, 1983 75

Figure 2. Lithic Stage, Substage4, ca. 11,000-9,600 B.P. Planoid-Cordilleran Tradition (-): 1) Late Ajuereado,

Tehuacan (Puebla); 2) Valsequillo (Puebla); 3) Tlapacoya (Mexico; D.F.); 4) Iztapan, Mexico (D.F.); 5) possibly San

Juan (Queretaro); 6) Lerma (Tamaulipas); 7) San Isidro (Tamaulipas); 8) Devil's Mouth, Texas; 9) earliest La Calzada

(Nuevo Leon; 10) Guila-Naquitz, Cueva Blanca (Oaxaca). Llanoid-Cordilleran Tradition (A): 1) Rancho Colorado

(Chihuahua); 2) Samalayucan (Chihuahua); 3) Guaymas (Sonora); 4) Rancho Weicker (Durango); 5) San Marces

(Jalisco); 6) Los Tapiales (Guatemala). Fishtail Point Tradition (_): 1) Los Grifos (Chiapas); 2) Lowe-Ha complex,

Belize; 3) Quiche Basin, Guatemala; 4) Esperanza, Honduras; 5) Turrialba, Costa Rica; 6) Madden Lake, Panama.

12,000 B.P. to 9,000 s.P.28AlthoughindigenousLerma dominantsubsistenceactivities, in thatorder,in all sea-

points(namedafterone of the majorsites in Tamaulipas) sons, in all environments.29

Proportionsof deer bones,

predominatein this latterpartof the phase, Flacco and as comparedwith horse and antelope, increase in the

Plainviewpointsthatwere probablyderivedfromNE of floor layers, suggestingnew huntingstrategiessuch as

Mexico have also been found. Crude blades, burins, stalkingindividuallarge animals using atlatl-propelled

gravers,spokeshaves,and a host of special end-scraper dartswith barbedandpointedforeshafts.Mortars,grind-

types were used, andthe huntingof herdanimalsby the ing stones, andmullersappearin associationwith spring

lance-ambushingtechnique, rabbit (or other animal)

drives, and the collecting of small animalsare the pre-

29. Richard S. MacNeish, Excavations and Reconnaissance, Vol. 5,

The Prehistory of the Tehuacan Valley (University of Texas Press:

28. MacNeish, Nelken-Terner, and Johnson, loc. cit. (in note 15). Austin, Texas 1975) 361-374.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

76 ThePreceramicof Mesoamerica/MacNeish

and Nelken-Terner

seeds, agave, and opuntia leaves; and the presence of Oaxaca37 might be of this stage,38 but again better ar-

fall fruits suggests seed-collecting, leaf-cutting, and fruit- chaeological contexts are needed.

picking subsistence activities. The leg bones of some of There is some evidence that this Plano-Cordillerantra-

the smaller animals are broken in a manner that suggests dition, documented for central Mexico, extended as far

the use of traps.30All these late additions strongly sug- north as the Rio Grande in NE Mexico. Although the

gest that these groups had new supplementary subsis- evidence is poor, a related complex of Lerma points,

tence options that could be seasonally and environmen- blades, burins, choppers, and snub-nosed scrapers was

tally adaptive. found in the lowest levels of San Nicolas Cave, near San

The matenals from the nearby Valsequillo region, dated Juan del Rio in Queretaro39associated with large and

at just before 9, lS0 s.P., are less numerous.31A stemmed small extinct and modern mammalian remains.40

point with a concave base found along with laurel-leaf Somewhat betterevidence comes from the Lerrnaphase

points among numerous horse and antelope bones sug- of Tamaulipas, dated ca. 9,270 s p 4l Here extinct beaver

gests that a process similar to that of Ajuereado was and deer bones were associated with Lerma points that

unfolding. The data from the valley of Mexico, also perhaps were fastened to lances, and with other chipped-

meager, are from two sites: the Iztapan Mammoth Kill, stone tools. Both a triangular Plano-type point that per-

dated ca. 9,250 s.p.32 and Tlapacoya II, a campsite dated haps tipped an atlatl dart and one of the pebble ham-

ca. 9,920 s.P.33Both sites seem related to the above and merstones that might well have functioned as a pestle

indicate similar developments .34 Although household may indicate supplementary subsistence options. North

tools, including an obsidian blade, gouge, semi-lunar of Tamaulipas, toward the Rio Grande, although the eco-

knife, and end-of-blade scraper, were found at Iztapan, logical data are less secure, there are hints from sites

it was obviously a kill site and not a camp. Furthermore, like San Isidro, La Calzada, and Devil's Mouth that the

the occurrence in the same mammoth, of an Agate Basin, Planoid-Cordilleran gave way to Plano and other spe-

of a Lerma-type leaf point, and a trianguloid point of the cialized complexes.42

Plano tradition of the United States suggests multiple Most of the more northeasterly Mexican sites in latest

hunting techniques, the former points being used for Pleistocene times form a unit, although they seem to

lance-ambushing and the latter for dart-stalking. These have been increasingly influenced by the many special-

remains, obviously related to those from just across the ized contemporarycomplexes in the cental United States,

lake at Tlapacoya, may belong to a different seasonal such as Plainview, Agate Basin, Scottsbluff, and Eden,

subsistence pattern, for while Lerma points, blades, and all of which might be called Plano.

semi-lunar knives still occur at Tlapacoya, choppers, How far south this Planoid-Cordillerancomplex or tra-

grinding stones, and mortars are found in association not dition extended is unknown, but some of the dates (un-

only with extinct megafauna, like horse and tapir, but corrected) 8,100 B.C., 8,780 B.C., 8,960 B.C., and 9,050

also with deer and rabbit bones.35 B.C. from Cueva Blanca and Guila-Naquitz in Oaxaca

Also possibly related is a fluted point from Tlaxcala36 seem to be as early as those in the complexes just men-

and another that occurred in the Valley of Tlacolula, tioned.43The projectile points, however, are very few

37. Marcus C . Winter, personal communication, 1982.

30. Ibid. 234-245.

38. Roberto Garcia Moll, "Analysis de los Materiales Arqueologicos

31. C. Irwin-Williams, "A summary of archaeological evidence from de la Cueva del Texcal, Puebla," Dept. de Prehistoria, Coleccion

the Valsequillo region, Puebla, Mexico." Proceedings of the 9th In- Cientifica Arqueologia No. 56 (Mexico City 1977) 9-89.

ternational Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences,

39. Cynthia Irwin-Williams, personal communication, 1965.

Chicago (Mouton: The Hague 1967) 7-22.

32. Luis Aveleyra and M. Maldonado-Koerdell, "Association of ar- 40. MacNeish, Nelken-Terner, and Johnson, op. cit. (in note 15)

tifacts with mammoth in the Valley of Mexico," AmAnt 18:4 (1953) 238-239.

332-341. 41. Richard S. MacNeish, "Preliminary archaeological investigations

33. Mirambell, loc. cit. (in note 3). in the SiexTade Tamaulipas, Mexico," TAPhA48 (Philadelphia 1958)

152-203.

34. Christine Niederberger, Zohapilco: Cinco Milenios de Ocupacion

42. Jeremiah F. Epstein, T. R. Hester, and Carol Graves, eds., Pa-

AIumana en un sitio Lacustre de la Cuenca de Mexico, Dept. de

pers on the Prehistory of Northeastern Mexico and Adjacent Texas,

Prehistoria, Coleccion Cientifica, Arqueologia 30 (Mexico City 1976)

23-49. Centerfor Archaeological Research, Report No. 9 (University of Texas

at San Antonio 1980) 1-153; LeRoy Johnson, "The Devil Mouth

35. Mirambell, loc. cit. (in note 3). Site, " Archaeological Series, Department of Anthropology, University

36. Angel Garcia Cook, "Una punta acanalada en E1 Estado de Tlax- of Texas, No. 6 (Austin, Texas, 1964) 46-57, figs. l5, l7.

cala, Mexico," FAIC No. 9 (Pueblo, Mexico 1973) 25-26. 43. Kent V. Flannery, Joyce Marcus, and Stephen A. Kowalewski,

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field ArchaeologytMol. 10, 1983 77

LermaandPedernales and manyof the otherartifacts, unitIS, thatdlatesperhapsfrom8,900-9,300 B.P., a fluted

lildethose fromTexcal Cave, phaseI, seem as relatedto point like those of Fell's Cave and E1 Inga as well as

our El Riego remains as to latest Ajuereado from two MaddenLake-likeFishtailpointsandsome "40,000

Tehuacan. other so-called artifacts."50Althoughthe tools are in-

Equallydifficultto documentis the EarlyMan tradi- adequatelydescribed,some of the scrapersseem iden-

tion in NW and sw Mexico, but Clovis pointsfoundat a tical to those of the Lowe-hacomplexof Belize.51Good

number(ca. 19) of surfacesites (RanchoWeicker,Dur- contextsand exact dates, so far, are totally missing. In

ango; Guaymas,Sonora;Rancho Coloradoand Sama- Belize our Lowe-hacomplex promisesto betterdefine

layucan,Chihuahua; etc.) in NW Mexico,44a flutedpoint the tradition,52but what we have now are mainly ma-

in associationwith about 14 Lerrnapoints, blades, bur- terialsfrom surfacecollections53and about200 artifacts

ins, and otherartifactsfound at Los Tapialesin Guate- from tests. In summary,we have found so far: Fishtail

mala, dated ca. 10,710 s.P.45 hint that the basic (bothMaddenLakeandFell's Cave vaneties)andPlain-

Cordillerancomplex of westernMexico and the Pacific view-likepoints,snub-nosedend scrapers(SantaMarta's

drainageareaof Guatemalawas undergoinga similarset parabolicend scrapers),stemmedend scapers(like Los

of influencesfromthe north.In this case, however, the Grifos), fine bifacialknives, half-moonchoppers,coup

sourceof the influenceseems to have been the Folsom de pong-like pointedchoppers,and side scrapers,both

and/orClovis (Llano)complexesof the westernUnited big and little. In fact, the complex is all so new and so

States. Perhapsthis should be called Llanoid-Cordil- ill-definedthatit is best to say no more.

leran.Exactdefinitionof this latterhypotheticaltradition We know poorly early man in Mesoamerica,but we

must await more adequateexcavationwith bettersam- do know he was there. Our hopes for the future are

ples and artifacts.Thus, much that is new may be ex- runninghigh. In fact, one of these days we may even

pectedfrompeople digging in the NW of Mesoamerica. be able to describeearly man and his culturesdunng

The southernborderof both these Cordillerantradi- each substagein Mesoamerica.The best is yet to come

tions, on the basis of the Los Grifos,Chiapasfinds, may for this first stage, so now let us turn to the second

be somewherein Guatemalaand southernMexico and stage the Archaic which is a little betterdocumented

just northof our thirdtraditionthatis literallyjust com- by artifacts,but still only known from a few excavated

ing out of the groundin CentralAmerica.Earlyfinds by components.

Ripley Bullen near Esperanzain Hondurashinted that

suchexistedas he foundsurfacesites with flutedFishtail The ArchaicStage

points.46In Panama,the finds of MaddenLake, etc.,47 The generalstage sees the shift frombasicallya hunt-

as well as thoseat Turrialba,CostaRica,48indicatedthat ing subsistencesystemto one of collectingand, with it,

this new traditionalso existedin these CentralAmerican fewerprojectilepointsandan emphasison grindingtools.

countries, and K. Brown's recent finds in the Quiche Also accompanyingthis shift is a scheduledsubsistence

Basin of Guatemalashowed that somethingsimilarex- system, band life, the domesticationof plants with the

isted there.49Los Grifos Rock Shelterhas producedin concomitantrise of agriculture,and a sedentaryway of

life.

"The Preceramic and Formative of the Valley of Oaxaca," AIandbook

The firststage, ArchaicI, commenceswith the end of

of Middle American Indians-Archaeology Supplement No. I (Uni- the Pleistocene,the extinctionof the megafauna,a shift

versity of Texas Press: Austin, Texas 1981) 48-93. to a scheduledcollecting way of life, and a seasonal

44. Garcia-Barena, op. cit. (in note 19) 1-12. micro-macroband settlementpattern(FIG. 3). The new

45. Ruth Gruhn and Alan Lyle Bryan, "Los Tapiales: A Paleo-Indian

campsite in the Guatemalan Highlands," Proceedings of the American cupations in the Quiche Basin, Guatemala," AmAnt 4s (1980)

313-

Philosophical Society 121 :3 (Philadelphia 1977) 235-271. 324.

46. Ripley P. Bullen and William W. Plowden, Jr., "Preceramic 50. Diana Santamaria, "Preceramic occupations at Los Grifos Rock

Archaic Sites in the Highlands of Honduras," AmAnt 28:3 (1963) Shelter, Ocozocoautla, Chiapas, Mexico," paper at Union Interna-

382-385. tional de Ciencas Prehistoricos y Protohistoricos X Congress, October

47. Junius B. Bird and Richard Cooke, "The occurrence in Panama

19-24(Mexico City 1981) 1-14.

of two types of Paleo-Indian projectile points," in Early Man in Amer- 51. MacNeish, Wilkerson, and Nelken-Terner, loc. cit. (in note 24).

ica, A. D. Bryan, ed. (University of Alberta: Edmonton, Alberta

1978) 263-272.

s2. MacNeish, loc. cit. (in note 27).

48. Michael J. Snarkis, "Turrialba a Paleo-Indian Quarry and

s3. Thomas R. Hester, Thomas C. Kelly, and Giancarlo Ligabue,

"A Fluted Paleo-Indian projectile point from Belize, Central Amer-

Workshop in Eastern Costa Rica," AmAnt 44 (1979) 125-138.

ica," Center for Archaeological Research, Working Papers No. I

49. Kenneth L. Brown, "A brief report on Paleoindian archaic oc- (University of Texas at San Antonio: San Antonio 1981)1-16.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

78 The Preceramic of MesoamericatMacNeish and Nelken-Terner

Figure 3. Archaic Stage, Substage1, ca. 9,600-7,000 B.P. Maritime Tradition (_): 1) Sand-Hill, Belize and Orange

Walk complex, Belize; 2) possibly Concheros (Vera Cruz). Santa Marta (a): 1) Santa Marta (Chiapas); 2) Jicaras

(Oaxaca). E1 Reigo (A): 1) E1 Riego, Tehuacan (Puebla); 2) Texcal (Puebla); 3) possibly Playa I, Mexico (D.F.);

4) Hidalgo, Tecolote Cave (Hidalgo). Infiernillo Tradition (A): 1) Infiernillo (Tamaulipas); 2) San Isidro (Nuevo

Leon); 3) Cueva de la Zorra (Neuvo Leon). Cochise Tradition: Sulphur Springs.

adaptationto the Holocene flora and fauna in various seasonal inland hunting. Closely relatedto and devel-

eco-areasled to the rise of a numberof culturaltraditions oping out of Sand Hill are the Orange Walk phases

in the generalperiod from ca. 9,000 to 7,000 B.P. (in (8,000-7,000 B.P.), also with boat buildingand wood-

radiocarbontime). working tools and macroblades.Lowe, Trinidad,and

One of these phases in the coastal ecozone of Belize San Nicolas points; small crescentic end scrapersand

was Sand Hill, roughly9,500-8,000 B.P. While it had pestles;milling stones;and mullersalso occurred.Now

large, wide, La Mina-likeand Pedernales-likepoints, it theirseason-roundcollectionincludedseeds, buthunting

is characterized by a host of largemacrobladesthatoften and maritimesubsistenceactivities still occurred.The

seem to have been used in woodworking(see FIG. 6). extensionof these complexes from Belize is unknown,

These plus gouges, adze-likeend scrapers,and the lo- but some of the earliestremainsin Cubaand Haiti may

cation of sites on an island suggest boat building.Thus be relatedbecausethey, too, have macrobladesandsim-

thereis a hint of a maritime-adapted aspectto theirsub- ilar scrapers.So far, no remainsof this time periodhave

sistence,butthe majorityof sites wereinland,suggesting been found in otherpartsof the Gulf or Pacific coasts,

some sort of seasonal plant collecting to go with their but we wouldnot be surprisedif such, when found, will

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field ArchaeologylVol. 10, 1983 79

be relatedto that which has been just discovered in coastal B.P.-that may extend up the Sierra Madre de Tamau-

Belize.54 lipas on the south to as far north as La Calzada and San

Perhaps physically closest to this complex and of the Isidro in Nuevo Leon.61 While Abasolo, Trinidad, and

same time period is the Santa Marta complex, found in Nogales, scraperplanes, grinding stones, and twined bags

Santa Marta Cave near Ocozocoautla in highland Chia- and baskets occur in it as well as in the E1 Riego tradi-

pas.55This complex is characterizedby Trinidadand San tion, Infiernillo Diamond and Almagre points are unique

Nicolas contracting stemmed points (called Almagre in to this northerncomplex as are mortars and pestles, Fue-

the original report), as well as Abasolo, Matamoros, and gan nets, and twined baskets. Again, these people seem

Nogales points, fine blades, small scraper planes, and to have been seasonally scheduled collectors who may

grinding stones. The Jicaras complex from Oaxaca with have been domesticating pumpkins, seteria, and perhaps

its Pedeinales, Trinidad, San Nicolas, and La Mina points chile.

and small scraper planes also is of this same tradition Perhaps to the NS the Sulphur Springs phase of the

and C-14 dates are roughly of the same period (6,500- Cochise tradition may extend down from Arizona and

9s000 s.P.).56 How far south this tradition extends, we New Mexico, and it as well as the Infiernillo, E1 Riego,

do not know, but the Oaxaca finds may represent the and Santa Marta traditions-all of the highlands-seem

northernedge, for just north of this complex are ones of closely related. In fact, they all had been earlier classi-

the El Riego tradition. Like it, this Santa Marta tradition fied as of the Desert Culture tradition on the basis of

seems to have basically a scheduled subsistence system their general similarities.62To better understandcultural

with hunting and plant collecting and, in some of its later developments, however, we have subdivided this more

periods, pumpkins and runner beans were perhaps being general tradition. But even our subdivisions are poorly

cultivated in Oaxaca. documented and much research is needed for this stage

North of this Santa Marta tradition in the central high- in many more parts of Mesoamerica.

lands of Mexico is one called the El Riego tradition that That situation is equally true for the second substage,

includes the El Riego phase of Tehuacan,s7 perhaps the 5,000-3,500 B.C., that is characterized by local plant

earliest remains from Texcal Cave of northernPuebla,sS domestication, stone bowls, and larger numbers of arti-

maybe the earliest part of the poorly represented Playa I facts (FIGS.4, 6). Again to the NS, extending down from

of the Valley of Mexico,59 and the Hidalgo complex of the sw, would be the Chiricahua phase of the Cochise

Tecolote Cave of Hidalgo.60 All seem to date from tradition, but in NE Mexico would be the Repelo tradi-

roughly 9,000 B.P. to 7,000 B.P. Hidalgo, El Riego, tion.63The Repelo tradition would be represented by the

Flacco, and Trinidad points characterize this complex as Ocampo phase in sw Tamaulipas, La Perra and Nogales

do scraper planes, bifacial choppers, crude blades, mull- in eastern Tamaulipas, with the latter extending down

ers, and milling stones. Data from Tehuacan suggest a the coast as far as Laguna Chila near Tampico, Vera

seasonal microband-macrobandsettlement pattern, buri- Cruz.64Some of the remains from La Calsada65and Cueva

al ceremonialism, and a seasonally scheduled subsist- de la Zona66 of Nuevo Leon may also belong to this

ence system with perhaps avocado, chile, and cucurbita tradition. Characteristicof this traditionare Abasolo (Ca-

mixtabeing cultivated andlor domesticated. Again, exact tan), Nogales, and Tortugas (Matamoros)points, gouges,

northern extension of this tradition is unknown, but in small discoidal scraper planes and choppers, grinding

southern Tamaulipas there seems to be a new phase, stones, a seasonally scheduled subsistence system in-

Infiernillo. cluding domesticates like corn, beans, squash and pump-

This phase seems to represent a new tradition-In- kins, and a macro-microband settlement pattern.

fieinillo, dated at roughly the same period 9,000-7,000 Probably north of this complex in Coahuila and ex-

tending into Texas was the Pecos River tradition with its

54. RichardS. MacNeish,Third Annual Report of the Belize Archaic

61. MacNeish,loc. cit. (in note 41).

Archaeological Reconnaissance (RobertS. PeabodyFoundationfor

Archaeology:Andover,Massachusetts1982) 1-53. 62. Ibid.

55. MacNeishand Peterson,loc. cit. (in note 10). 63. Ibid.

56. Flannery,Marcus,and Kowalewski,loc. cit. (in note 43). 64. Ibid.

57. MacNeish, Nelken-Terner,and Johnson, op. cit. (in note 15) 65. C. Roger Nance, "La Calzadaand the PrehistoricSequencein

366-372. NortheastMexico," in Epstein,Hester,andGraves,eds., op. cit. (in

note 42) 41-57.

58. GarciaMoll, loc. cit. (in note 38).

66. BurneyB. McClurkan,"The Archaeologyof la Cuevade la Zona

59. Niederberger,op. cit. (in note 34) 247-252.

de Derrumbes,"in Epstein, Hester, and Graves, eds., op. cit. (in

60. CynthiaIrwin-Williams,personalcommunication,1965. note 42) 59-69.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

80 ThePreceramicof MesoamericalMacNeish

and Nelken-Terner

Figure4. ArchaicStage, Substage2, ca. 7,000-5,500 B.P. BelizeanTradition(A): 1) Belize Complexsite, Belize;

2) PalmasSola (VeraCruz).TehuacanTradition(*): 1) Coxcatlan;2) Texcal (Puebla);3) Blanca(Oaxaca);4) Playa2

and 1, Mexico (D.F.); 5) Tecolote. Repelo Tradition(*): 1) Negales (Tamaulipas);

2) La Perra(Tamaulipas);

3) Ocampo(Tamaulipas);4) Cuevade la Zorra(Nuevo Leon);5) La Calzada(Nuevo Leon);6) LagunaChila(Vera

Cruz).Pecos Tradition(+): 1) FrightfulCave (Coahuila);CochiseTradition:Chiricahua.

distinctiveLangtrystemmedpoints,butno agriculture.67 Hidalgo,69Playa I and II in the Valley of Mexico,70

Basically,this traditionis out of the realmof Mesoamer- Texcal II in northernPuebla,7lthe CoxcatlanCave in

ica, but south of the Abasolo traditionoccurs the Te- theTehuacanvalley,72andthe Blancaphase73in Oaxaca.

huacantradition,which is typical of ArchaicSubstage EverywhereareHidalgo,Garyito,La Mina, Pelona,and

II in the highlandsof Mesoamerica.68Although more

datamay allow subdividingthis tradition,it seems to be 69. CynthiaIrwin-Williams,personalcommunication,1965.

representedby the Tecolote phase of Tecolote Cave in

70. Niederberger,loc. cit. (in note 34).

71. GarciaMoll, loc. cit. (in note 38).

67. Walter W. Taylor, "Archaic Cultures Adjacent to the North-

eastern Frontiers of Mesoamerica," Handbook of Middle American 72. RichardS. MacNeish,The Science of Archaeology (DuxburyPress:

Indians, Vol. 4 (University of Texas Press: Austin 1966) 59-94. Belmont,California1978) 146-151 .

68. MacNeish, Nelken-Terner, and Johnson, loc. cit. (in note 15). 73. Flannery,Marcusand Kowalewski,loc. cit. (in note 43).

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Field Archaeology/Vol. 10, 1983 81

Coxcatlanpoints, small scraperplanes, manos, metates, becausethe relativelylimitedremainsof this periodare

millingstones, mullerstonebowls, a seasonalscheduled burieddeeplyunderthe huge stratifiedsites of sedentary

subsistencesystem with the plantingof many domesti- agricultureof later ceramicperiods. Be that as it may,

cates, and a macro-microband settlementpattern.The the only adequatesample of remainswe have of this

manyplantsdomesticatednow spreadfrom each of the substageare from the Abejasphase of Tehuacan.76For

areasof initial domesticationto all the partsof the tra- this reason, this traditionis called the Abejas tradition

dition. Domesticatedplantsinclude amaranthand corn; and our meagercomparativematerialssuggest that the

common,tepary,andrunnerbeans;moschataand mixta MartinezremainsfromOaxaca,77the Texcalfromnorth-

squash;pumpkins,avocados, black and white zapotes, ern Puebla,78and the Zohapilco from the Valley of

and manyothers. Mexico79arealso of this traditionin the centralhighland.

Whetherthis traditionextendedsouth of Oaxacainto Projectilepoints at this time are relativelyrare, being

highlandsouthernMexico and CentralAmericaor there Garyito,Pelona, Shumla,Matamoros,and Catantypes,

is anothertraditionin that sub-areais at present un- as are scraperplanes, but grindingbowls aboundsuch

known. A couple of distincttraditionson the Gulf coast as mortars,pestles, mullers,milling stones, manos, me-

in thisperiodandcollectionsfoundnearSantaMartaand tates, tecomates, and hemisphericaland outflaring-rim

Los Grifos in Chiapas,however, suggest there may be stone bowls (FIG. 6). Fine blades also occur, as do dis-

yet anothersouthernhighlandArchaicSubstageII to be tinctive coiled basketsandpetates. While seasonalcol-

foundby futureinvestigations. lecting still took place, much of the subsistencecame

Now let us turnto the Mesoamericanlowlandswhere from hybridcorn agricultureof the incipientor subsist-

SubstageII remainsarevery rare.One of the complexes ence type. People were beginning to settle down and

on the coast of Belize is calledthe Belize phase (7,000- become sedentaryin base campsor hamlets, and burial

6,000 B.P.), with Nogales and San Nicolas-likepoints, ceremonialismcontinued. Here is the base on which

gouges, scraperplanes, large ovoid-flakeend scrapers, highlandvillage agriculture(with ceramics)was to be

grindingstones, and stone bowls.74While these people built.

seem to have exploited the coast and inlands, perhaps Closely relatedto these remains are those from the

seasonally,there is no evidence of plant domestication upperPreceramicSan Nicolas complexfroma cave near

or any kind of agriculture,incipientor otherwise.Ten- San Juandel Rio in Queretaro.80 This complexhas sim-

tativelywe considerthemto be of anotherwadition,which ilar and more projectilepoint types, but lacks the wide

tentativelywe havenamedBelizean.It contrastsnot only varietyof grindingstones and evidence of agriculture.

with those traditionsin the highlands,but also with an- Thismaybe representative of anotherundefinedtradition

other complex found on the Gulf coast that may be of of this final Archaicsubstage.To the northarethe other

this timeperiod.Herewe areconcernedwiththe remains phases Almagrein the Sierrade Tamaulipas,the Flacco

found originallyby J. Ford and Medellin Zenil on the and Guerracomplexof the SierraMadreof sw Tamau-

surfaceat PalmaSola on the centralcoastof VeraCruz.75 lipas and the Abasolo complex in northernTamaulipas

This collection includedGaryito,Pedernales,and Cox- that may be put in the Abasolo tradition.8lHere Mata-

catlanpoints, obsidianblades, and scraperplanes, and morosand Catanpredominate.Here are grindingtools,

no grindingstones. The points suggest it is of the time scraper planes, and corn agriculture and possible

periodof SubstageII, and if it is a viable entity, then it sedentarism.

must be yet anothertradition.Definitionof such a hy- As is obvious, all these complexesand phases of the

potheticaltradition,however,mustawaitarchaeological highlandsin the final Archaicstagearerelativelysimilar

investigationin this area. Also, we need evidence for even thoughwe have classified them into separatetra-

this period for the Pacific coast. So, much needs to be ditions. This highlandtraditioncontrastswith the few

done. meager remainswe have from lowland sub-areas,the

As incompleteas is our knowledgeof SubstageII of latterof whichresembleone another.In fact, it is in this

the Archaic, however, it is better than what we have

fromSubstageIII, thatcrucialtransitionalperiodleading

to village agriculturewith ceramics.SubstageIII existed 76. MacNeish,op. cit. (in note 72) 151- 155.

roughlyfromca. 5,500 B.P. to 4,300 B.P. in radiocarbon 77. Flannery,Marcus,and Kowalewski,loc. cit. (in note 43).

time (FIG. 5). Exactly why we have so few remainsof

78. GarciaMoll, loc. cit. (in note 38).

this substage, we do not understand,but perhapsit is

79. Niederberger,loc. cit. (in note 34).

74. MacNeish,loc. cit. (in note 54). 80. CynthiaIrwin-Williams,personalcommunication,1965.

75. MacNeish,Nelken-Terner,and Johnson,loc. cit. (in note 15). 81. MacNeish,loc. cit. (in note 41).

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

82 The Preceramicof Mesoamerica/MacNeish

and Nelken-Terner

Figure 5. Archaic Stage, Substage3, ca. 5,500-4,300 B.P. Abejas Tradition (|): 1) Abejas phase (Tehuacan);

2) Martinez phase (Oaxaca); 3) Texcal (Puebla); 4) Valley of Mexico: Zohapilco (D.F.). San Nicholas: 1) San

Nicholas. Abasolo (v): 1) Flacco phase (Tamaulipas); 2) Guerra phase (Tamaulipas); 3) Almagre (Tamaulipas);

4) Abasolo (Tamaulipas); Cochise Tradition: San Pedro. Maritime Tradition (v): 13 Matanchen (Nayarit); 2) Ostiones

(Guerrero); 3) Chantuto (Chiapas); 4) Palo Hueco (Vera Cruz); S) Melinda, Belize; 6) Progreso, Belize; (*) 7) Cerro

Mangote, Panama.

period or substage that the highland-lowland dichotomy bles, and seafood remains.82 This has been called the

that carries through ceramic times was born. Unfortu- Matanchen complex and whether or not it is related to

nately, the three or four complexes from as many low- the Ostiones remains, dated ca. 2,920 + 130 B.C. at

land areas, which perhaps are of as many traditions, are Puerto Marquez in Guerrero, is unknown. We say this

very poorly known and documented. All, however, seem because all that was found in the so-called Ostiones com-

to represent complexes or traditions with a sedentary way plex were flakes and a piece of ground-stone metate with

of life based on a maritime subsistence system with little the burned clay floor of some sort of house.83 Further

evidence of agriculture. 82. JosephB. Mountjoy,R. E. Taylor, and LawrenceH. Feldman,

On the Pacific coast, Preceramic remains have been "MatanchenComplex:New RadiocarbonDateson EarlyCoastalAd-

found at three places and all are basically shell mounds aptationsin West Mexico" Science 175 (1972) 1242-1243.

with very few artifacts. At the Matanchen shell midden 83. CharlesF. Brush, "A Contributionto the Archaeologyof Coast

at Ceboruco on the coast of Nayarit, in layers dated ca. Guerrero,Mexico," unpublishedPh.D. Dissertation,Departmentof

3,710 B.P., were found four flakes, three worked cob- Anthropology,ColumbiaUniversity(New York 1969) 1-175.

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

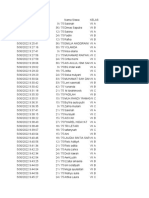

_ Substage

15,000

4,300 i14_ B.R B.P.

j 21 S¢ , , .

l00000000 . 11: . S , \\\\\\\\\W\X\\XX(;

large, , , , _ X flake

, , . - *

83

of Field Archaeology/Vol. 10, 1983

Journal

I

OF MESOAMER/CA

SURAREAS

and

Stages

Puebla Valley of Veracruz north-

Substages Panama interior Belize a Yucatan Chiapas Oaxaca Mexico Gulf east

south-

north- south Mexico interior interior

coast a Central Central Central Coast Mexico

westwest America east -

coast

Mexico Mexico a America America

Gulf Gulf Gulf

Mexico Central Coast

Radiocarbon America Coast Coast

Dates

<g. g,

ARC/iA/C F

<

A

3Jusage2 :

> 3

'\ t

ng <31uC

W X

i i

stone gde

Wet| 4t g DOME STICAT{ON

|

9,600 B.P. j ;R *

Psw:s,:

D -s

L/T/i/C X- %gtR-

-

Substage4 = R-

. . . . .

/ s .

/ / / / /

§ * * * * * * * * * * * .

/ / / / / /

/ / iS / y /

/ / / / / /

/ / / / /

-__-

B.P. _____

11,000

S S

* . ¢ .t g g

L/T///C | *@ . endscraper . . . . . . . . crude . .burin.

Substage 3 * * * * * * * * * * * * *

i g X S

5i

L/Tf//C flake ' bone ' 9 ' side-scraper

' side- ^ point spoke-shave-like

scraper point

______ ______

_ _,

more than 30,000 B*P.

-fe,%

L/TH/C X chopper

Substage I

I

in Mesoamerica.

Figure 6. Sequence of Archaic Traditions

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

84 The Preceramic of MesoamericalMacNeish and Nelken-Terner

east on the same Pacific coast in Chiapaswere the more 30,000 to 40,000 years. Limitedexcavationsin a few

abundantshell-moundremains of the Chantutocom- areasdefinea sequenceof EarlyManandArchaicstages

plexes thatdatebetween5,100 B.P. and4,000 B.P.84 Here, and substages,but the coverage is very limited and of

workedflakes andnebulousground-stonetools occurred varyingquality. Most of what we have, however, has

in extensive shell-mounddeposits at a numberof sites. been amassedin the last 20 years and if new data con-

Thus there are late Preceramiccoastal remainson the tinue to be acquiredat the same rate for the next 10

Pacific coast that seem differentfrom the contempora- years, then our conclusionsshouldbe on a muchfirmer

neous highlandremains,but just what culturesor tradi- foundation.

tions such maritime remains belong to cannot be

determinedon the basis of these very meagerremains.

The samemaybe saidof the nebulouschipsandscrap-

ers found in the Preceramicstratifieddeposits at Palo RichardStocktonMacNeishis the Directorof the

Hueco on the TlacolutlaRiver in the centralVera Cruz RobertSingletonPeabodyFoundationfor Archaeology

Gulf coast thatdate about5,000 s.P.85 in Andover,Massachusetts,as well as Professorof

The other remainsfrom the Gulf coast are from the Archaeologyin the Departmentof Archaeologyof

Belize Gulfcoast andbelongto two complexes:Progreso Boston University,Boston, Massachusetts.He received

(5,000X,000 B.P.) and Melinda(6,000-5,000 B.P.). Both

his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. from the Universityof

are mainly surface collections, so they, too, are only Chicago.He has workedthroughoutthe New World

tentativelydefined.86The earlierMelindacomplex,which for 45 years and has publishedover 214 articles or

in largepartcomes from one excavation,seems to have monographson his varied research.His interests

Shumlapoints, discoidalscrapersandchoppers,gouges, includethe origin of New Worldagricultureand the

grlndlngstones, a marltlmesubslstencesystem, andper-

. . . . .

Preceramicto which this articlepertains.

hapsa sedentaryway of life on the coast. This complex

may developinto the Progresocomplexon the coast and AntoinetteNelken-Terneris a charge'de recherche

along the rivers, which perhapshad a sedentaryway of of the CentreNationalde la RechercheScientifiquede

life based on agriculture.Progresomay have evolved France in Mexico City. She receivedher trainingand

into the early Swasey ceramicscomplex, for both have degreesat the Sorbonnein Paris and at the Escuela de

a numberof stone tools in common such as Progreso Antropologiaof Mexico. She is a specialistin the

points, keeled end scrapers,scraperplanes, blades, and period of the neolithicrevolutionand has done

manos and metates. All this is very tentative,however,

fieldworkin Mexico and Peru.

and will remain so until excavationsare completedin

the region.Then, perhaps,we will be ableto refinethese

complexes and determinetheir relationshipsto other

coastalcomplexes,includingthe CerroMangoteremains

to the southin Panama.87

ConcludingRemarks

It is readily apparentthat much researchis needed,

not only for the final stage of the Archaicin Mesoam-

erica, but for all of the Preceramic.All we can say now

is thatPreceramicremainsdo exist in Mesoamericaand

have existed for a considerablelength of time, perhaps

84. Barbara Voorhies, "The Chantuto People: An Archaic Period

Society of the Chiapas Li Horal, Mexico," in Papers of the New

World Archaeological Foundation 41 (Provo, Utah 1976) 1-147.

85. S. Jeffrey K. Wilkerson, "Pre-agricultural Village Life: The Late

Preceramic Period in Veracruz," Contributions of the University of

California Archaeological Facility, No. 27 (Berkeley, California 1975)

111-122.

86. MacNeish, loc. cit. (in note 54).

87. Charles R. McGimsey, "Cerro Mangote: A Preceramic site in

Panama," AmAnt 22 ( 1956) 15 1-161 .

This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Wed, 4 Feb 2015 17:18:56 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Kindred of The EastDocument229 pagesKindred of The EastAnonymous YYApoNFwet83% (12)

- Robert B. Fox. The Tabon Caves: Archaeological Explorations and Excavations On Palawan Island, Philippines (Manila, 1970) P. 40Document4 pagesRobert B. Fox. The Tabon Caves: Archaeological Explorations and Excavations On Palawan Island, Philippines (Manila, 1970) P. 40Jan Arlyn Juanico100% (1)

- Klein, Sartre and Imagination in The Films of Ingmar Bergman - Dan WilliamsDocument243 pagesKlein, Sartre and Imagination in The Films of Ingmar Bergman - Dan WilliamsMario PM100% (1)

- Whatmough Dialects FootnotesDocument49 pagesWhatmough Dialects FootnotesСтефан ПоповацNo ratings yet

- MacNeish PreceramicMesoamerica 1983Document15 pagesMacNeish PreceramicMesoamerica 1983CHrisNo ratings yet

- Paul Tolstoy - Early Sedentary Communities of The Basin of Mexico PDFDocument16 pagesPaul Tolstoy - Early Sedentary Communities of The Basin of Mexico PDFAngel Sanchez GamboaNo ratings yet

- Valsequillo-Gonzalez Et Al 2006Document18 pagesValsequillo-Gonzalez Et Al 2006mikey_tipswordNo ratings yet

- Valesquillo ContreversyDocument18 pagesValesquillo Contreversymikey_tipswordNo ratings yet

- MacNeish - Early Man in The New WorldDocument13 pagesMacNeish - Early Man in The New WorldTeresa AlarconNo ratings yet

- 2001 Speth and Tchernov Neandertal HuntiDocument22 pages2001 Speth and Tchernov Neandertal HuntiAnaLiggiaSamayoaNo ratings yet

- Obsidian Industries and Cultural Evolution in The Basin of Mexico Before 500 B. CDocument12 pagesObsidian Industries and Cultural Evolution in The Basin of Mexico Before 500 B. CErnesto ZamarripaNo ratings yet

- Massone y Prieto 2004Document14 pagesMassone y Prieto 2004Gabriel Bahamonde MijalicNo ratings yet

- Pleistocene Pocket Gophers From San Josecito Cave, Nuevo Leon, MexicoFrom EverandPleistocene Pocket Gophers From San Josecito Cave, Nuevo Leon, MexicoNo ratings yet

- Talalay Split Leg Figs AJA 1987Document10 pagesTalalay Split Leg Figs AJA 1987cucutenilitNo ratings yet

- 20000-15000BCE SolutreanDocument3 pages20000-15000BCE SolutreanBradley KenneyNo ratings yet

- Christensen and Winter 1997Document14 pagesChristensen and Winter 1997Soledad VictoriaNo ratings yet

- Laventa TitlepageDocument4 pagesLaventa TitlepageTefaNo ratings yet

- Pensamiento GeometricoDocument28 pagesPensamiento GeometricomemfilmatNo ratings yet

- Erlandson 2002Document34 pagesErlandson 2002Camila NeveuNo ratings yet

- Laventa TitlepageDocument4 pagesLaventa TitlepageAlejandra SandovalNo ratings yet

- PaleontologiaDocument21 pagesPaleontologiaMG Snchez RNo ratings yet

- Symbolic Use of Marine Shells and Mineral Pigments by Iberian NeandertalsDocument6 pagesSymbolic Use of Marine Shells and Mineral Pigments by Iberian NeandertalsBibyAlexaNo ratings yet

- Time Shaping DevicesDocument25 pagesTime Shaping DevicesEmiliano Mendoza PliegoNo ratings yet

- Zilhao - Symbolic Use of Marine Shells NeandertalsDocument6 pagesZilhao - Symbolic Use of Marine Shells NeandertalsNicholas RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Vedic Aryans and The Origins of Civilization Forth Expanded Edition With Additions On Natural History, Genetics and The... (Etc.) (Z-Library)Document57 pagesVedic Aryans and The Origins of Civilization Forth Expanded Edition With Additions On Natural History, Genetics and The... (Etc.) (Z-Library)anjanaNo ratings yet

- Tlatilco and The Pre-Classic Cultures of The New WorldDocument3 pagesTlatilco and The Pre-Classic Cultures of The New WorldJose ShelldonNo ratings yet

- Datación R14 CoahuilaDocument17 pagesDatación R14 CoahuilaKaban BasurtoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 PrehistoryDocument20 pagesLecture 1 PrehistoryChristopher PhillipsNo ratings yet

- Michael. B. Schiffer. Formation Processes of The Archaeological Record. Xxiv + 428 Pages, 70 Illustrations, 7 Tables. 1987. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press ISBN 0-8263..Document3 pagesMichael. B. Schiffer. Formation Processes of The Archaeological Record. Xxiv + 428 Pages, 70 Illustrations, 7 Tables. 1987. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press ISBN 0-8263..Jorge Luis Ortega VivancoNo ratings yet

- Lamb QSR 2009 IpDocument17 pagesLamb QSR 2009 IpSalvador MedinaNo ratings yet

- Clovis Technology at The Anzick SiteDocument32 pagesClovis Technology at The Anzick SitePaid0sNo ratings yet

- Genomic Insights Into The Early Peopling of The Caribbean: ReportsDocument10 pagesGenomic Insights Into The Early Peopling of The Caribbean: ReportsdannyrgsjNo ratings yet

- American Association For The Advancement of ScienceDocument5 pagesAmerican Association For The Advancement of ScienceDaniel SuaDuaNo ratings yet

- PRIMARY vs. SECONDARY SOURCESDocument2 pagesPRIMARY vs. SECONDARY SOURCESShannise Dayne ChuaNo ratings yet

- Hallazgo de Entierro de La Cultura OlmecaDocument3 pagesHallazgo de Entierro de La Cultura OlmecaRafael CastilloNo ratings yet

- The Late Pleistocene Human Occupation of Mexico: January 2008Document25 pagesThe Late Pleistocene Human Occupation of Mexico: January 2008Angel SánchezNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of Ornaments and Art: An Archaeological Perspective On The Origins of "Behavioral Modernity"Document54 pagesThe Emergence of Ornaments and Art: An Archaeological Perspective On The Origins of "Behavioral Modernity"aayyllaNo ratings yet

- The Cueva de ChiquhuiteDocument8 pagesThe Cueva de ChiquhuitearqueolisNo ratings yet

- Paleolithic Murals 2005Document2 pagesPaleolithic Murals 2005Anderson de paulaNo ratings yet

- Lab Handout: Geologic Time and The Fossil RecordDocument5 pagesLab Handout: Geologic Time and The Fossil RecordAlexander McConnellNo ratings yet

- Concepts A Contemporary Maya Achi) Community: Cations EpigraphyDocument39 pagesConcepts A Contemporary Maya Achi) Community: Cations EpigraphyKarla PerezNo ratings yet

- Third Millennium ChronologyDocument15 pagesThird Millennium ChronologykapilNo ratings yet

- Archaeomalacology Revisited: Non-dietary use of molluscs in archaeological settingsFrom EverandArchaeomalacology Revisited: Non-dietary use of molluscs in archaeological settingsCanan CakirlarNo ratings yet

- A Re-Examination of The Mesoamerican ChacmoolDocument12 pagesA Re-Examination of The Mesoamerican ChacmoolNumismática&Banderas&Biografías ErickNo ratings yet

- Timeline Teachers Page Version 3bDocument5 pagesTimeline Teachers Page Version 3bbheroNo ratings yet

- The Cosmogony of The Three WorldsDocument7 pagesThe Cosmogony of The Three WorldsJan Peter de JongNo ratings yet

- Gudeman1971 CompadrazgoDocument37 pagesGudeman1971 CompadrazgoFranciscoNo ratings yet

- Mesolithic & Neolithic PeriodDocument44 pagesMesolithic & Neolithic PeriodOlia IoannidouNo ratings yet

- The Guardian Directive: ... and the First Battle for EarthFrom EverandThe Guardian Directive: ... and the First Battle for EarthNo ratings yet

- The CalendarDocument109 pagesThe CalendarJaeden Woodland100% (1)

- Yucatan Fed KemetDocument3 pagesYucatan Fed KemetMeru Muad'Dib Massey BeyNo ratings yet

- Batangrande PDFDocument43 pagesBatangrande PDFenrique19111975No ratings yet

- Atlatl Final 3Document14 pagesAtlatl Final 3Adolfo OkuyamaNo ratings yet

- Thinking About Archaeoastronomy PDFDocument28 pagesThinking About Archaeoastronomy PDFPron GoesNo ratings yet

- Zilhao Et Al 2010 PNAS Neandertal ShellsDocument79 pagesZilhao Et Al 2010 PNAS Neandertal ShellsdoukaterNo ratings yet

- Two Symbols of Time in Nahuatl ReligionDocument24 pagesTwo Symbols of Time in Nahuatl Religiontemporarily digital ghost100% (1)

- 33.holtorf, Life of A Potsherd (Contemporary)Document23 pages33.holtorf, Life of A Potsherd (Contemporary)danieladiasortegaNo ratings yet

- The Story of Life in 25 Fossils: Tales of Intrepid Fossil Hunters and the Wonders of EvolutionFrom EverandThe Story of Life in 25 Fossils: Tales of Intrepid Fossil Hunters and the Wonders of EvolutionNo ratings yet

- HIST141 SyllabusDocument7 pagesHIST141 SyllabusBrianKoNo ratings yet

- Holiday ListDocument1 pageHoliday Listankitaagarwal89No ratings yet

- IHRMDocument233 pagesIHRMAmit Khundia100% (1)

- MCB101 Exercise 5Document5 pagesMCB101 Exercise 5triciallorin_19No ratings yet

- Things From The TownDocument485 pagesThings From The TownDamon Casantini100% (2)

- (GD2023) Bai Tap Tuan 19 Khoa de 9935702 5272023105406PMDocument43 pages(GD2023) Bai Tap Tuan 19 Khoa de 9935702 5272023105406PMitsme ngthanNo ratings yet

- Final StandingsDocument13 pagesFinal StandingsVenkatesan RamalingamNo ratings yet

- MSC Biotechnology EntranceResult PublicationDocument8 pagesMSC Biotechnology EntranceResult PublicationJay MatheNo ratings yet

- The Diplomat - Issue 1, 2010/2011Document20 pagesThe Diplomat - Issue 1, 2010/2011National University of Singapore Students' Political AssociationNo ratings yet

- Purch111 ReviewerDocument8 pagesPurch111 ReviewerBeverly A PanganibanNo ratings yet

- The Domesticated Asian Elephant in IndiaDocument21 pagesThe Domesticated Asian Elephant in IndiaeyeshoeNo ratings yet

- Use of English 01ADocument2 pagesUse of English 01AТетяна СтрашноваNo ratings yet

- Culture, Sub-Culture & Cross CultureDocument20 pagesCulture, Sub-Culture & Cross Culturenehparam14No ratings yet

- Clipower MarathiDocument3 pagesClipower MarathiRohit ParmarNo ratings yet

- 491Document41 pages491Shubhodeep Guha RoyNo ratings yet

- Drinking - Punch Bowls - PorcelainDocument70 pagesDrinking - Punch Bowls - PorcelainThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (1)

- Ukk Bahasa Indonesia Kelas VII (Responses)Document27 pagesUkk Bahasa Indonesia Kelas VII (Responses)Muhammad NursinNo ratings yet

- Independence DayDocument2 pagesIndependence DayAnita VarmaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Test For PortfolioDocument3 pagesChapter 8 Test For Portfolioapi-251282471No ratings yet

- Naming Rituals of The Kayapo XikrinDocument4 pagesNaming Rituals of The Kayapo Xikrinapi-303009494No ratings yet

- Guide To BNS Holdings PDFDocument25 pagesGuide To BNS Holdings PDFErica ClarkNo ratings yet

- Food Preparation - Dog Irons, Andirons & FirebacksDocument57 pagesFood Preparation - Dog Irons, Andirons & FirebacksThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center50% (2)

- Tanjong Rhu NotesDocument2 pagesTanjong Rhu NotesNarcissca Ariadne Alvarez83% (6)

- SL No District Name District Rte Nodal Officer Name District Rte Nodal Officer Mobile Number Block Name Blockrte Nodal Officer Mobile NumberDocument10 pagesSL No District Name District Rte Nodal Officer Name District Rte Nodal Officer Mobile Number Block Name Blockrte Nodal Officer Mobile NumberAnand Aryan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Annotatedbibliography HDDocument9 pagesAnnotatedbibliography HDapi-202480675No ratings yet

- Ohio State Fair July 28 ReleaseDocument2 pagesOhio State Fair July 28 ReleaseJennifer ShaferNo ratings yet

- De Bellis Fantasticus - Here There Be Dragons IIDocument76 pagesDe Bellis Fantasticus - Here There Be Dragons IIA Jeff Butler100% (2)