Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sir Sherwin

Sir Sherwin

Uploaded by

Christian PhilipOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sir Sherwin

Sir Sherwin

Uploaded by

Christian PhilipCopyright:

Available Formats

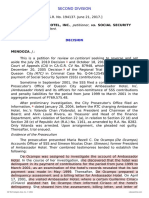

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. 110776 May 26, 1995

MARANAW HOTEL & RESORT CORPORATION (CENTURY PARK

SHERATON MANILA), petitioner,

Vs.

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION AND CIRO

BETILA, respondents.

DECISION

PUNO, J.:

Private respondent CIRO BETILA worked with petitioner Century Park

Sheraton Hotel — Manila as a room attendant from June 22, 1980 until July

22, 1989 when his services were terminated. The facts leading to his dismissal

are as follows:

On January 22, 1989, Mr. Motomu Okumura, a Japanese guest at the

Sheraton Hotel, filed a complaint with the Tourist Security Division* of the

Department of Tourism regarding the loss of 40,000 Japanese yen and

US$210.00 inside his hotel room.

An investigation was conducted by the Tourist Security Division. It found out

that the room attendant assigned to Mr. Okumura’s room on the day of the

loss was private respondent. It invited private respondent to appear on January

22, 1989 to shed light on the complaint. Private respondent failed to appear

despite receipt of notice. The investigation proceeded in his absence.

On January 28, 1989, the Tourist Security Division submitted a progress

report 1 to the hotel, with the following findings:

Investigation disclosed that Betila reported to (sic) duty on 22 January 1989

and left (at) around 2:00 p.m., earlier than his off duty, but after he had

service(d) Room 350 and no other room attendant entered the same room until

5:00 p.m. when the theft was discovered by the victim. The following day, said

person (Betila) failed to appear for investigation because such day was his

scheduled day-off. The records of Personnel Assignment Where Alleged Losses

Occurred, furnished this office by the Security Division, Century Park Sheraton

Hotel show that from June 1986 to December 1988, there were 12 reported

losses in the room assignments of Betila and all (the lost articles) were not

recovered. Two of the mentioned cases were reported to this office and

investigated by Investigators Romeo Balanquit and Leo Castillo. Both

investigators informed the undersigned that in their respective cases,

investigation disclosed that the reported losses in the room assignments of

Betila all occurred on the date before his scheduled day off, thereby providing

him (with) the best opportunity to escape investigation immediately after the

discovery of the crime committed. Said modus operandi is true in the instant

case. (Rollo, p. 54)

Private respondent was recommended to be separated from

service.

On April 5, 1989, Mr. Masatoshi Kusumoto, another Japanese guest at the

hotel, also lost his money. Again, it appeared that private respondent was the

one who cleaned his room on said date. The Tourist Security Division sent

private respondent a letter informing him of Mr. Kusumoto’s complaint. He was

also invited to appear before said office on April 8, 1989 for investigation. Once

more, private respondent did not honor the invitation. The investigation

proceeded in his absence. From the Worksheet submitted by private

respondent himself to the hotel, it was established that he was the only person

who entered the room of Mr. Kusumoto on said date, prior to the discovery of

the missing money. The investigator again recommended the dismissal of

private respondent “to deter him from victimizing more hotel guests to the

detriment of the hotel in particular and the tourism industry in general.” 3

In a letter,4 dated May 5, 1989, Nicolas R. Kirit, Executive Housekeeper of the

hotel, informed respondent Betila of the findings of the Department of Tourism

as contained in its two (2) letter-recommendations, copies of which were

attached to said letter. Private respondent was required to explain his side

within forty-eight (48) hours from receipt of the letter. Despite receipt of said

letter on May 11, 1989, private respondent did not submit his explanation.

The hotel’s management then proceeded to evaluate the findings and

recommendations made by the investigators of the Department of Tourism. It

decided to dismiss private respondent from the service and he was informed of

his dismissal in a Memorandum,5 dated July 17, 1989. He refused to

acknowledge its receipt. Instead, he filed a complaint for illegal dismissal and

unfair labor practice against petitioner. In a Decision,6 dated November 8,

1991, Labor Arbiter Salimathar V. Nambi declared his dismissal as illegal and

ordered his immediate reinstatement. The labor arbiter's decision was affirmed

by public respondent National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) — Second

Division 7 on appeal. Petitioner’s motion for reconsideration was denied.

Hence, this petition for certiorari under Rule 65.

Petitioner contends that:

RESPONDENT NLRC COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION AMOUNTING TO

LACK OF JURISDICTION IN HOLDING THAT PRIVATE RESPONDENT WAS NOT

ACCORDED DUE PROCESS.

RESPONDENT NLRC COMMITTED GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION AMOUNTING TO

LACK OF JURISDICTION IN HOLDING THAT PRIVATE RESPONDENT WAS

DISMISSED WITHOUT JUST CAUSE.

We find for the petitioner.

We do not agree with public respondent that private respondent was denied due

process on the ground that he was not formally investigated by the hotel or by the

investigator of the Department of Tourism regarding the reported losses.8

The records clearly show that petitioner fully complied with the required notice and

hearing9 prior to the dismissal of private respondent. Private respondent was given at

least three (3) chances to explain the reported losses. The investigation reports reflect

that private respondent was invited on two (2) occasions to shed light on the

complaints received from the Japanese guests of the hotel. Private respondent did not

appear in said investigations. Nor did he submit any written explanation to the

investigators exculpating himself from the charges. Finally, petitioner itself notified

private respondent of the result of the investigation conducted by the two (2)

investigators. He was required to explain but private respondent did not take heed. He

persisted to remain silent as a sphinx.

These established facts belie the finding that private respondent was denied due

process before he was dismissed. Time and again, we have stressed that due process

is simply an opportunity to be heard. Private respondent was given more than ample

opportunity to defend himself. He chose not to use his opportunities.

In a belated effort, private respondent tried to explain why he was unable to honor the

invitation to go to the Tourism office on January 22, 1989. Allegedly, he served as

Chairman of the union's COMELEC to oversee the referendum conducted by their

union on the same date.10 This afterthought excuse cannot justify his repeated

failure to explain his side. What is telling is that from the time he was first

summoned to shed light on the complaint on January 22, 1989 until he was

dismissed from service on July 22, 1989, there was not a single denial or

explanation which came from private respondent as to his complicity in the

charges of theft. There is not a thread of evidence in the record to show that he

exerted any effort to attend the investigations conducted nor even to air his side either

in person or in writing.

We also find that the public respondent erred when it found no just cause to warrant

the dismissal of private respondent. Its reliance on the case of Manila Midtown

Commercial Corporation v. Nuwhrain (Ramada Chapter) is misplaced. The factual

backdrop of the Manila Midtown case is totally different, thus:

Records likewise reveal that complainant [private respondent Masangkay] was

investigated relative to the aforesaid incidents. The investigation took place during the

months of January, June and July 1979 and the fourth or last one was on January

31, 1980. In the four investigations, no evidence was found which would link

complainant to the alleged acts of thievery. In all these four instances, respondent

[petitioner corporation] initiated numerous steps to ascertain the complaints of its

guests and to find out the guilt or involvement of the employee complained of. Among

the steps or measures adopted by the respondent was the body search of the

suspect, an intensive search of the suspect’s belongings and a thorough

investigation in respondent’s security office. All these steps taken by respondent

against complainant produced negative results. . . .

Records further reveal that there were other persons who had free access to the

hotel rooms such as the friends or visitors of the guests, janitor, chambermaid

and the housekeeper supervisor who inspects the work of the roomboy, janitor and

the chambermaid.

If respondent was really determined in its quest to find the culprit, it

should have investigated not only the roomboy [respondent Masangkay] but

also its other employees who likewise had free access to the hotel guest’s

room. The record is bereft of any evidence relative to this matter.

(Emphasis supplied)

In an attempt to align the case at bench with Manila Midtown, public

respondent opined that as a standard operating procedure, all employees of a

hotel are searched before they leave. It is a fact, however, that searches of this

nature are usually cursory. They are not done with the specific intention

of looking for stolen articles, unless there has been a reported loss and

the search is focused on a specific employee suspected to be responsible

therefor. Thus, in the Manila Midtown case, it had come to the knowledge of

the Ramada Hotel that the belongings of one of its hotel guests were missing

and Masangkay, private respondent therein, was one of the persons who had

access to the guest’s room. On the day the loss was discovered, private

respondent was already suspected as responsible for the burglary and he was

bodily searched and his things were thoroughly probed on that very day. In the

case at bench, however, the loss came to the knowledge of the hotel only after

private respondent had already left for the day. In fact, on January 22, 1989,

private respondent left at 2:00 p.m., earlier than he should. Hence, private

respondent was not given an on-the-spot thorough search.

Finally, in the Manila Midtown case, it was shown that there were other

persons and employees of the hotel who had access to the rooms serviced by

the private respondent. The theft could not be exclusively attributed to the

private respondent. In the case at bench, it has been established that only

private respondent had access to and actually entered the unoccupied

rooms of Mr. Okumura and Mr. Kusumoto on the day of the burglary. No

other person could have perpetrated the thefts.

We reiterate the rule that in cases of dismissal for breach of trust and

confidence, proof beyond reasonable doubt of an employee’s misconduct is not

required. It is sufficient that the employer had reasonable ground to believe

that the employee is reasonable for the misconduct which renders him

unworthy of the trust and confidence demanded by his position.12 In the case

at bench, it cannot be doubted that petitioner succeeded in discharging its

burden of proof.

IN VIEW WHEREOF, the petition is hereby GRANTED. The decision of public

respondent NLRC (Second Division), dated April 27, 1993, is SET ASIDE. No costs.

SO ORDERED.

Narvasa, C.J., Regalado and Mendoza, JJ., concur.

Footnotes

Agency specifically charged with receiving and investigating complaints

filed by tourists.

1. Rollo, pp. 54-55.

2. id., p. 55.

3. id., p. 56.

4. id., p. 57.

5. id., p. 65.

6. id., pp. 99-106.

7. Penned by Commissioner Rogelio I. Rayala and concurred in by Presiding

Commissioner Edna Bonto-Perez. Commissioner Domingo H. Zapanta,

however, registered his dissent; Decision, dated April 27, 1993, Rollo, pp.

32-44.

8. Rollo, at p. 105.

9. Article 277 (b), Labor Code, as amended.

10. Comment, Rollo, at p. 181.

11. No. L-57268, March 25, 1988, 159 SCRA 212.

12. Auxilio, Jr. v. National Labor Relations Commission, G.R. No.

82189, August 2, 1990, 188 SCRA 263; Ocean Terminal Services, Inc. v.

National Labor Relations Commission, G.R. No. 85446, May 27, 1991,

197 SCRA 491.

Summary

Background of the Case

The case involves the dismissal of Ciro Betila, a former room attendant at

Century Park Sheraton Hotel Manila, due to accusations of theft.

The dismissal was upheld by the court.

Complaints and Investigations

A Japanese guest, Mr. Motomu Okumura, filed a complaint with the

Department of Tourism regarding the loss of money from his hotel room. Betila

was the room attendant assigned to Okumura’s room on the day of the loss.

Betila was invited to appear before investigators but failed to do so.

Investigation revealed that Betila had left work earlier than his scheduled off-

duty time on the day of the theft. Another Japanese guest, Mr. Masatoshi

Kusumoto, also reported a loss of money from his room. Betila was again found

to be the room attendant assigned to Kusumoto’s room on the day of the loss.

Betila was invited for investigation but did not honor the invitation. It was

established that Betila was the only person who entered Kusumoto’s room

prior to the discovery of the missing money.

Dismissal and Complaint

Based on the investigation findings, the hotel management decided to dismiss

Betila from his job. Betila was informed of his dismissal but refused to

acknowledge the receipt of the memorandum. He filed a complaint for illegal

dismissal and unfair labor practice against the hotel.

Initial Decision and Appeal

The Labor Arbiter initially declared Betila’s dismissal as illegal and ordered his

reinstatement. The National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) affirmed the

decision on appeal.

Petition for Certiorari

The hotel filed a petition for certiorari, arguing that Betila was not denied due

process and that there was just cause for his dismissal.

Court’s Decision

The court agreed with the hotel’s arguments.

It found that Betila was given ample opportunity to defend himself but failed to

appear for investigation. The court emphasized that due process is simply an

opportunity to be heard, and Betila chose not to use his opportunities to

explain his side.

The court disagreed with the NLRC’s finding that there was no just cause for

Betila’s dismissal. It distinguished the present case from a previous case cited

by the NLRC, highlighting the differences in the factual backdrop. In the

present case, it was established that Betila was the only person who had

access to and entered the rooms where the thefts occurred. The court

reiterated that in cases of dismissal for breach of trust and confidence, proof

beyond reasonable doubt is not required. It is sufficient that the employer had

reasonable grounds to believe that the employee is responsible for the

misconduct.

Conclusion

The court granted the hotel’s petition and set aside the decision of the NLRC.

Betila’s dismissal was upheld, and he was not reinstated to his former position.

You might also like

- John Deere 4055 4255 4455 4555 4755 4955 Shopmanual Sec WatDocument20 pagesJohn Deere 4055 4255 4455 4555 4755 4955 Shopmanual Sec Watdoris97% (32)

- Stanley Gibbons 'Commonwealth & British Empire Stamp Catalogue 2007' Report and Market UpdateDocument12 pagesStanley Gibbons 'Commonwealth & British Empire Stamp Catalogue 2007' Report and Market Updatepeter smith100% (1)

- Sample Pre Trial BriefDocument3 pagesSample Pre Trial BriefKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Manila Vs NuDocument3 pagesManila Vs NuChristine BernalNo ratings yet

- LEGASTH Case Study No. 2Document2 pagesLEGASTH Case Study No. 2Laurene Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Manila Midtown Vs NUWHRAIN RamadaDocument3 pagesManila Midtown Vs NUWHRAIN RamadatengloyNo ratings yet

- Manila Hotel Corp. Et Al. v. NLRC, Et Al. G.R. No. 120077 October 13, 2000Document11 pagesManila Hotel Corp. Et Al. v. NLRC, Et Al. G.R. No. 120077 October 13, 2000Ivan Angelo ApostolNo ratings yet

- Concorde Hotel Vs CA - NewDocument5 pagesConcorde Hotel Vs CA - NewmilkymimiNo ratings yet

- 2 Ambassador - Hotel - Inc. - v. - Social - Security PDFDocument8 pages2 Ambassador - Hotel - Inc. - v. - Social - Security PDFmikko al rashid ringiaNo ratings yet

- Durban Apartments v. Pioneer, G.R. No. 179419, January 12, 2011Document10 pagesDurban Apartments v. Pioneer, G.R. No. 179419, January 12, 2011Alan Vincent FontanosaNo ratings yet

- 477 Scra 277Document4 pages477 Scra 277RYWELLE BRAVONo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 120077Document21 pagesG.R. No. 120077Amicus CuriaeNo ratings yet

- Amj 800Document11 pagesAmj 800looadadodNo ratings yet

- Cases ConflictsDocument74 pagesCases ConflictsDbee DveeNo ratings yet

- LABORDocument131 pagesLABORRobynne LopezNo ratings yet

- Territorial JurisdictionDocument45 pagesTerritorial JurisdictionGigiRuizTicarNo ratings yet

- Credit CasesDocument113 pagesCredit CasesRoby Renna EstoqueNo ratings yet

- Santiago Alcantara, JR., Petitioner, vs. The Court of Appeals and The PENINSULA MANILA, INC., Respondents. G.R. No. 143397, August 6, 2002. FactsDocument2 pagesSantiago Alcantara, JR., Petitioner, vs. The Court of Appeals and The PENINSULA MANILA, INC., Respondents. G.R. No. 143397, August 6, 2002. FactsTiff DizonNo ratings yet

- Cases ConflictsDocument70 pagesCases ConflictsJohn Varenz MonteroNo ratings yet

- AMBASSADOR HOTEL v. SSSDocument8 pagesAMBASSADOR HOTEL v. SSSVeah CaabayNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Abuse of RightsDocument3 pagesDoctrine of Abuse of RightsMary Jean BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Durban Apartments Corp. v. Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corp., G.R. No. 179419, January 12, 2011Document6 pagesDurban Apartments Corp. v. Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corp., G.R. No. 179419, January 12, 2011Nathan NatividadNo ratings yet

- People V RomeroDocument6 pagesPeople V Romerogel94No ratings yet

- 015 Maranaw Hotel v. NLRC - 238 SCRA 190 PDFDocument3 pages015 Maranaw Hotel v. NLRC - 238 SCRA 190 PDFJNo ratings yet

- 2 - Manila Hotel vs. NLRCDocument10 pages2 - Manila Hotel vs. NLRCjannahNo ratings yet

- RTC Makati Movement Against Graft and Corruption v. Dumlao A.M. P 93 800Document11 pagesRTC Makati Movement Against Graft and Corruption v. Dumlao A.M. P 93 800Dino Bernard LapitanNo ratings yet

- Sagum V CaDocument9 pagesSagum V CaNick NañgitNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws CasesDocument150 pagesConflict of Laws CasesDe Jesus MitchshengNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 189366 December 8, 2010 Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company, Petitioner, EUSEBIO M. HONRADO, RespondentDocument6 pagesG.R. No. 189366 December 8, 2010 Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company, Petitioner, EUSEBIO M. HONRADO, RespondentElleNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 179419Document1 pageG.R. No. 179419wex smithNo ratings yet

- Mabeza Vs NLRC PDFDocument8 pagesMabeza Vs NLRC PDFSheena ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- 2018.11.26. Plaintiffs' Reply ISO Emergency Motion Civil ContemptDocument25 pages2018.11.26. Plaintiffs' Reply ISO Emergency Motion Civil ContemptdoczharNo ratings yet

- 030b - Manila Hotel V NLRCDocument8 pages030b - Manila Hotel V NLRCvick08No ratings yet

- Maranaw Hotels and Resort Corp Vs NLRC - 123880 - February 23, 1999 - J. Purisima - Third Division PDFDocument3 pagesMaranaw Hotels and Resort Corp Vs NLRC - 123880 - February 23, 1999 - J. Purisima - Third Division PDFChristelle Ayn BaldosNo ratings yet

- Pfl-Case-2-Globe-Mackay-AssignmentDocument2 pagesPfl-Case-2-Globe-Mackay-AssignmentChrystelle ManadaNo ratings yet

- Decision: PUNO, J.Document8 pagesDecision: PUNO, J.Clark RiaNo ratings yet

- SC Decision Preventive Suspension ExtendDocument34 pagesSC Decision Preventive Suspension ExtendCSC Legal Congress 2022No ratings yet

- People of The Philippines v. Martin L. RomeroDocument4 pagesPeople of The Philippines v. Martin L. RomerobearzhugNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Respondent: Ambassador Hotel, Inc., Social Security SystemDocument9 pagesPetitioner Respondent: Ambassador Hotel, Inc., Social Security SystemMac Norhen BornalesNo ratings yet

- Edilberto L. Barcelona, Petitioner, V. Dan Joel Lim and Richard Tan, Respondents. Decision Sereno, C.J.Document10 pagesEdilberto L. Barcelona, Petitioner, V. Dan Joel Lim and Richard Tan, Respondents. Decision Sereno, C.J.Jean Monique Oabel-TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Barcelona v. LimDocument21 pagesBarcelona v. LimAAMCNo ratings yet

- Durban Apartments Co VS Pioneer Insurance and Surety CorpDocument7 pagesDurban Apartments Co VS Pioneer Insurance and Surety CorpTon Ton CananeaNo ratings yet

- Durban Apartments CorporationDocument11 pagesDurban Apartments CorporationChristiane Marie BajadaNo ratings yet

- Globe Mackay Cable and Radio Corp DigestDocument1 pageGlobe Mackay Cable and Radio Corp DigestCecilia Alexandria GodoyNo ratings yet

- Durban vs. PioneerDocument7 pagesDurban vs. PioneerVanessaClaireTeroPleñaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 120391Document4 pagesG.R. No. 120391Tashi MarieNo ratings yet

- Natl Semiconductor Vs NLRCDocument4 pagesNatl Semiconductor Vs NLRCWonder WomanNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 148198 October 1, 2003 People of The Philippines, Appellee, ELIZABETH "BETH" CORPUZ, AppellantDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 148198 October 1, 2003 People of The Philippines, Appellee, ELIZABETH "BETH" CORPUZ, AppellantroigtcNo ratings yet

- GR No 114337 Nitto Enterprises V NLRC PDFDocument4 pagesGR No 114337 Nitto Enterprises V NLRC PDFmayNo ratings yet

- Digest CaseDocument21 pagesDigest CaseRacel Abula100% (2)

- Cam Vs Casimiro (Uncorroborated and Unsubstantiated Allegation Are Not Sufficient To Establish Probable CauseDocument2 pagesCam Vs Casimiro (Uncorroborated and Unsubstantiated Allegation Are Not Sufficient To Establish Probable CauseJM BanaNo ratings yet

- Ambassador Hotel G.R. No. 194137Document5 pagesAmbassador Hotel G.R. No. 194137sofiaNo ratings yet

- Nego Necessary Deposit CasesDocument7 pagesNego Necessary Deposit CasesCZARINA AUDREY SILVANONo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Joint AffidavitDocument8 pagesSupreme Court: Joint AffidavitMesuella BugaoNo ratings yet

- Reyes vs. GaaDocument3 pagesReyes vs. GaaFrankneilNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Vs CADocument14 pagesOmbudsman Vs CAshijazaeNo ratings yet

- Mabeza v. NLRC, April 18, 1997Document12 pagesMabeza v. NLRC, April 18, 1997BREL GOSIMATNo ratings yet

- 32 Alcantara vs. CA G.R. No. 143397 August 6, 2002Document3 pages32 Alcantara vs. CA G.R. No. 143397 August 6, 2002jovani emaNo ratings yet

- Necessary Deposit - Durban Apartments Vs Pioneer InsuranceDocument7 pagesNecessary Deposit - Durban Apartments Vs Pioneer InsurancePamela ParceNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 158075 June 30, 2006Document10 pagesG.R. No. 158075 June 30, 2006kick quiamNo ratings yet

- 030-Uniwide Sales Warehouse Club v. NLRC, G.R. No. 154503, Feb 29, 2008Document11 pages030-Uniwide Sales Warehouse Club v. NLRC, G.R. No. 154503, Feb 29, 2008Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- CandidateHallTicket PDFDocument1 pageCandidateHallTicket PDFAditya YadavNo ratings yet

- Crim 4 Week 6Document2 pagesCrim 4 Week 6Rose Jane JuanNo ratings yet

- Engineering Tribology: Engineering Tribology by John Williams of Cambridge University Is An IdealDocument3 pagesEngineering Tribology: Engineering Tribology by John Williams of Cambridge University Is An IdealNguyen Van QuyenNo ratings yet

- C2a. Logic SimplificationDocument53 pagesC2a. Logic SimplificationNicolaas LimNo ratings yet

- OneTravel - Booking ConfirmationDocument2 pagesOneTravel - Booking ConfirmationRizky AlfianNo ratings yet

- Winchester 1895 RifleDocument28 pagesWinchester 1895 RifleTactic Otd ArgNo ratings yet

- VD - Part 03 - Body DesignDocument49 pagesVD - Part 03 - Body DesignEmre DemiralpNo ratings yet

- PL 2022-23 Weekly Reflective Journal PDP Assessment TemplateDocument11 pagesPL 2022-23 Weekly Reflective Journal PDP Assessment TemplateImran khanNo ratings yet

- Mapper User ManualDocument66 pagesMapper User ManualHarsha KodaliNo ratings yet

- AGPU Everything-About-PVC enDocument16 pagesAGPU Everything-About-PVC enPierluigi GhioneNo ratings yet

- Define National Income Eco415Document3 pagesDefine National Income Eco415aishahNo ratings yet

- PT Dago Energi Nusantara TIME SHEET BULANAN KARYAWAN (26 Mar 2022 SD 25 Apr 2022)Document7 pagesPT Dago Energi Nusantara TIME SHEET BULANAN KARYAWAN (26 Mar 2022 SD 25 Apr 2022)muchamad luthfi aliNo ratings yet

- 275 River Ave Carramar Qmf-Os-080-Application-Tree-Work-Permit-Updated-Annually-For-Website-And-Customer-Service-Centre2Document1 page275 River Ave Carramar Qmf-Os-080-Application-Tree-Work-Permit-Updated-Annually-For-Website-And-Customer-Service-Centre2dsfeir123No ratings yet

- Electrical Power Distribution Part 1 Fundamentals For Every EngineerDocument25 pagesElectrical Power Distribution Part 1 Fundamentals For Every EngineerFlooriNo ratings yet

- CV 2013 NgouneDocument4 pagesCV 2013 NgouneNGOUNENo ratings yet

- Midrex 2017 DFM1stQtrPrintFinalDocument13 pagesMidrex 2017 DFM1stQtrPrintFinalMohamed ShabanNo ratings yet

- Eng IV Letter of IntentDocument1 pageEng IV Letter of Intentapi-550469361No ratings yet

- Business Form Three Term 3 Holiday AssignmentDocument4 pagesBusiness Form Three Term 3 Holiday Assignmentbalozi training InstituteNo ratings yet

- Working Capital Management: Unit: 5Document20 pagesWorking Capital Management: Unit: 5Shaifali ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Universal Precautions in Infection PreventionDocument18 pagesUniversal Precautions in Infection PreventionadiNo ratings yet

- Duolingo 50 Words Essay Questions and AnswerDocument7 pagesDuolingo 50 Words Essay Questions and AnswerMaria AgnesNo ratings yet

- Bridgestone OTR Product Guide 03-07-2016 PDFDocument80 pagesBridgestone OTR Product Guide 03-07-2016 PDFwillupowersNo ratings yet

- Team Manager Appraisal Sample DocumentDocument14 pagesTeam Manager Appraisal Sample DocumentVeeNo ratings yet

- PF MainDocument500 pagesPF MainDFTB ClothesNo ratings yet

- Industrial Marketing 5-6Document2 pagesIndustrial Marketing 5-6Mary Grace Ygot ParachaNo ratings yet

- 2 Concept Plan - Myanmar Workshop - Final PDFDocument0 pages2 Concept Plan - Myanmar Workshop - Final PDFmaungohsiNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship File Very ImportantDocument32 pagesSummer Internship File Very ImportantYash SharmaNo ratings yet

- District Wise List of Working Units of Eou'SDocument21 pagesDistrict Wise List of Working Units of Eou'SOm PrakashNo ratings yet