Professional Documents

Culture Documents

West 2017

West 2017

Uploaded by

gogayin869Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

West 2017

West 2017

Uploaded by

gogayin869Copyright:

Available Formats

IPOs: The Third Year On

Jessica West, Giovanni Fernandez,

and K.C. Ma

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

A

Jessica West virtue of capitalism is that capital of financing may be irrelevant, the general

is an assistant professor is market driven to businesses public remains broadly enamored with IPOs,

of finance at Stetson

with the most profitable, produc- which can be as addictive as the Wheel of

University in DeLand,

Florida. tive opportunities. In a perfect Fortune; rival investment opportunities rarely

jwest1@stetson.edu world, two firms with similar production produce such astonishing returns in a short

should have equivalent value, but they may period of time. For that, the Oracle has a

Giovanni Fernandez have different mixes of financing depending stronger opinion:

is an assistant professor on each owner’s risk and return preference

of finance at Stetson

University in DeLand,

on capital. In this regard, an initial public You don’t have to really worry about

Florida. offering (IPO) is considered no more than a what’s really going on in IPOs. People

gfernan1@stetson.edu funding or liquidity event. Private compa- win lotteries every day but there’s no

nies, having limited access to public capital, reason to let that affect [your invest-

K.C. M a often risk diluting their own returns in ment strategy] at all. You have to

is the Roland George

exchange for outside capital in order to grow find what makes sense and follow

Professor of Applied

Investments at Stetson and scale the firm. As the “Oracle,” Warren your own course. If they want to do

University in DeLand, Buffett, said, mathematically unsound things and

Florida. one person gets lucky … it’s nothing

kcma@stetson.edu Families that own successful busi- to worry about. You don’t want to

nesses have multiple options when get into a stupid game just because

they contemplate sale. Frequently, it’s available. Buffett [2016]

the best decision is to do nothing.

There are worse things in life than IPO ONE-DAY POPS

having a prosperous business that

one understands well… If the con- Ironically, several early academic studies

glomerate form is used judiciously, it may have been responsible for the common

is an ideal structure for maximizing misperception that IPOs are, across the board,

long-term capital growth. With all its great investments (Logue [1973], Ibbotson

excesses, market-driven allocation of [1975], and Ritter [1984]). Other than the

capital is usually far superior to any 65% average one-day gain during the Internet

alternative. Buffett [2014, p. 8] bubble period (1999–2000), IPO day returns

have averaged approximately 20% since

Although the Oracle’s view is consistent 1961 in the United States, consistent across

with the argument that the particular form the world exchanges. However, most of the

Summer 2017 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 137

Exhibit 1

IPO First-Day Returns

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

IPO “pops” happened on the day of the IPOs, which the owners and underwriters. The typical methods

is mainly a result of the “underpricing discount,” mea- include, for example, lockup options (primarily con-

sured by the percentage change in the first-day closing sidered defensive arguments to avoid the controversial

price and the IPO offer price (Exhibit 1). These returns Commissions, Laddering, Analyst conf licts of interest,

seem more speculative than those that can be explained and Spinning (CLAS) prior to IPO releases),3 the 60-day

by theory. Such prosperity has been attributed to both post-IPO cool-off period, the up-to-two-year lockup

the issuers and the underwriters managing the IPOs’ period, private equity pull outs, and the resolution of

process taking advantage of the information asymmetry the information asymmetry.

of the private companies.1 As a result, the IPO pop is

not quite as interesting or relevant, because it is merely WHY SHOULD IPOS BE DIFFERENT?

leaving owners’ money on the table, and the average

public investors miss out on the opportunity all together. The consistent evidence that IPOs underperform

in the long run begs an obvious question: Why should

IPO FIVE-YEAR FLOPS IPOs be singled out and expected to perform differently

from seasoned stocks? After initial hurdles are met in

Perhaps a more meaningful issue is the long- the first year, an IPO transforms into a seasoned stock.

standing finding that IPOs have underperformed their Consider that going public, or initiating the IPO pro-

benchmarks for as long as five years after issuance. For cess, signifies an important rite of passage in the life of

the 74 years between 1935 and 2008, though not in the a young company. Rational owners should constantly

same order of magnitude, a number of authors found a weigh the costs and benefits of staying private versus

consistent pattern of underperformance in IPO returns going public.4 Such a decision should inherently depend

as significant as 20% –30% for the three-to-five-year on whether the public shares would be worth more than

period after their issuances. However, the long-term the private shares. The reverse works for owners who

underperformance should not be hastily dismissed as decide to go private. On that front, one plausible expla-

the result of the previous one-day pops because doing nation for potential underperformance is that IPOs on

so would not make economic sense. An efficient capital average are overvalued relative to comparable firms and

market would not allow an asset class with consistently can be expected to grow much faster than comparable

abnormal returns to exist over the long haul; simple seasoned firms.5 Therefore, underpricing is an oppor-

arbitrages would eliminate any known or persistent risk- tunity cost to firms that want to go public.

adjusted excess returns, positive or negative.2 To find the costs and benefits of going public, or

The conventional argument attributes the under- initiating an IPO, we draw on the previous research and

performance to various forms of market frictions. The existing theoretical framework of other experts in the

underperformance develops as a result of prolonged field. Ritter [2011] estimated that the direct cost of IPOs

information asymmetry that gives some investors a is around 7% of the net proceeds. Additionally, for the

competitive advantage that is often manufactured by first-day-18% return and 30% outstanding shares sold

138 IPOs: The Third Year On Summer 2017

Exhibit 2

Post-IPO Long-Term Returns

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

during IPOs, the opportunity cost that issuers leave on they may be buying a lemon, which could stall or derail

the table is around 9%. Why would a company choose the IPO altogether. Investors may disagree over com-

to go public if the costs are so high? Some obvious rea- pany quality and offer price prior to the IPO, and they

sons include the desire to raise capital, to allow current may have disputes over strategy throughout the public

shareholders to cash out, to have publicly traded stock to life of the firm (Brealey, Leland and Pyle [1977]).

clarify the firm’s valuation, and to provide a currency for The cost of sequestering duplicate information is

making stock-financed acquisitions. Many companies usually paid by a large number of investors in public

are acquired shortly after going public. firms. It can be reduced by the availability of a public

The opportunity to tap the public market for price that conveys information to all investors so that

equity capital is the most convincing argument about only a fraction of the investors will incur the informa-

why firms would go public—especially firms with tion production cost (Chemmanur and Fulghieri [1999]).

high-growth prospects but with limited access to other Similarly, the public market provides a tradeoff between

financing alternatives because of high leverage and duplicate information costs and the benefits from the

transaction costs (Kim and Weisbach [2008]). Although useful signals from serendipitous information, aggregated

this argument is consistent with minimizing the cost from the diverse information that stock market investors

of capital and maximizing firm value (Modigliani and collect randomly (Subrahmanyam and Titman [1999]).

Miller [1963]), the availability of capital is more impor- A more novel idea is to suggest that IPOs are a

tant than the cost of capital for an aging private com- prelude to future takeover activities (Zingales [1995],

pany that exhausts all the capital from private sources. Brau, Francis, and Kohers [2003], and Brau and Fawcett

A related argument is the liquidity benefit of being pub- [2006]). An IPO can serve as the first step toward selling

licly traded. For example, firm managers benefit from a company at an attractive price through a takeover.

control and inf luence over investment decisions despite Similar to the capital market access argument, IPOs

potential disagreements with shareholders. However, create public shares for a firm that may be used as

firms prefer to deal with outside shareholders versus currency in acquiring other companies, such as being

suppressing inside shareholders. Therefore, there is an acquired in a stock deal.

obvious tradeoff between the benefits of corporate con- The IPO is a complex process, and to this point,

trol and the cost of liquidity. The role of the IPO is to most of the previous empirical studies emphasized the ex

establish a price/value for a firm as a base to provide post explanation of the empirical irregularity. We would

public market liquidity (Amihud and Mendelson [1988] like to propose a positive model that will predict the

and Boot, Gopalan, and Thakor [2006]). time-varying risk and returns over the life of the equity.

When a firm is public and widely held, investors

may be less informed than insiders and information may AN OPTION TO GO PUBLIC

be costly to obtain. Thus, investors are less informed

than the issuers about the true value of the companies Inevitably, company owners face a crucial decision

going public. As a result, investors are concerned that with regard to strategy over implementation of the best

Summer 2017 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 139

business platform and discretion on sources of capital, A standard exception would include a firm not

given a variety of choices. At any given point in time, publishing research reports or releasing information

business owners have the option to either go public or during the 25-day quiet period after a deal has been

stay private (with non-negative values), and vice versa. completed.7 In addition, IPO firms often voluntarily

When a firm is private (public), the going-private pull back the offering information just weeks prior to

(-public) option value is zero. The equity in a firm, the IPO dates, amid “potential shareholder litigation.”

public or private, is a residual claim on profits, assuming Further maneuvering involves firms allowing under-

the firm is liquidated and all outstanding debts and other writers to stabilize deals—that is, to buy shares of an

financial claims are paid off. Thus, it is customary to IPO to boost its price, up to 30 days after a deal under

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

consider that the stock is a call option on the firm’s SEC rules. After firms file the required S-1 reports with

liquidating value, with an exercise price on outstanding minimum information for the SEC registration, it is a

debts. As private firms always have an option to go common practice for the companies to only release year-

public and public firms an option to go private, the to-year financial statement comparisons to the general

decision to initiate an IPO may be valued as a call option public, even after the quarterly information is available.

to maximize the equity share values. This situation allows firms to delay release of prior year’s

Entrepreneurs start their businesses with family reports up to another three quarters. The design of the

capital to test their products. Despite very small odds, a up-to-2-year lockup period—which prevents insiders

young business may become profitable and generate high such as owners, private equity backers, and investment

“entrepreneurial” returns. Soon enough, before private bankers from selling their shares—can be considered a

returns start diminishing, some form of external capital way to prolong the information asymmetry.

is sought to maintain the owner’s returns. Unless one However, a maneuver of restoring information

is Warren Buffett,6 everyone thinks short-term. Private asymmetry through the investment banking process

firms often claim they are in business for the long haul. is, at best, transitory because all firms are required to

But it is only rational, in maximizing firms’ value, to be follow regulations, laws, or prospectus disclosures that

eventually out in the public market within 5 to 10 years. have prespecified, short timelines. The rationale is that

When owners wish to cash out their financial efficient outside investors will price in the net reduction

interests, they usually consider public company mergers of information risk premium, because they realize that

and acquisitions. When a private company’s profit- they will inevitably become more informed through

ability is constrained and the company needs to scale increasing analyst coverage, monitoring, and market

up, seeking outside capital or a public offering often scrutiny. Therefore, one would predict that the public

makes sense. To this end, access to the public capital shares, in their early issuing stage, or IPOs, will under-

market and increased liquidity are the two major ben- perform their counterpart seasoned public shares. This is

efits for the original private shareholders. However, this consistent with the stylized empirical findings that IPOs

has to be accompanied by giving up some ownership to underperformed in the first few years of their issuances.

gain access to the public capital market. In other words, On the other hand, the interplay of higher entrepre-

owners are forced to share the entrepreneurial returns neurial returns and lower information risk premium will

and their private shares become diluted. eventually play out. After the “growing pains” in the

However, there is a price to pay for the owners short run, most young IPO firms should still be able to

to access the public capital. Because insiders are always produce higher entrepreneurial returns so to start out-

more informed, including outside shareholders will performing the market. At this point, there is not yet

reduce the risk premium originated from the infor- any empirical finding showing IPO outperformance.

mation asymmetry. On that count, the public shares Given the extensive existing research literature on

are expected to produce lower returns than the private post-IPO long-term performance, we are not joining

shares. Rational owners constantly weigh the costs and the debates on the rationales or their significance. As a

benefits of staying private versus going public, and it practical matter, our study is restricted by the general

is in their best interest to restore the risk premium by lack of private company data before going public and

creating some artificial information asymmetry along public company data after going private. Consequently,

with the process of initiating the IPO. we focus more on the IPOs’ performance two years

140 IPOs: The Third Year On Summer 2017

after their issuance. We believe it is more interesting (46%) stocks. As of the end of 2015, the live stocks were

that most of the institutional restrictions have been actively traded and the dead stocks were not.

lifted and information asymmetry has been resolved. Following the standard procedures used in pre-

Provincially, young stocks have finally traded in a reg- vious studies, we further narrowed down the IPO stock

ular market environment, which allows us to assert some universe based on the following criteria: (1) the stock

economic sense. must have an identifiable IPO date, (2) the first-day

For the 90-year period between 1926 and 2015, close price or offer price has to be at least $1.00, (3) the

with over 35,000 IPOs, we uncover new evidence that stock has to be traded for at least 2/3 of the first five-year

IPOs have outperformed their counterparts by 5% a year period, and (4) the stock has to be a true first-time ini-

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

from the third year on. Accompanying the underperfor- tial public offering, rather than a seasoned or secondary

mance in the first two years, the result is consistent with offering, nor a result of change in corporate control, such

the argument that young companies need to dilute their as a merger and acquisition or restructuring.

private share returns as a “one-time price” to pay for the The dataset is further “scrubbed” for accuracy in

access to the public capital market. The added liquidity the following ways. First, when prices on the same stock

will enhance the new firms’ growth and the entrepre- come from different sources, these prices are verified for

neurial public returns. In the following sections, we consistency and accuracy. Even though the number of

will describe the empirical procedures for the findings. errors in price data is relatively small, mainly from typos,

the magnitude of these errors on the return computations

EMPIRICAL DESIGN would be enormous if not corrected, often in the order of

a million times. Second, if the stock is listed on multiple

To this day, the empirical procedures to examine exchanges, only one price, the primary issue, is used.

the IPOs’ return performance have been well developed. Third, because we include over-the-counter (OTC)

We select the most appropriate methods used in most stocks, great care has been taken to make sure that the

recent studies to answer the questions we posit in OTC IPOs were not a result of the falling angels delisted

this study. from the major exchanges. For stocks delisted from the

major exchanges and moved onto the OTC, we recon-

THE U.S. IPO UNIVERSE nect the price history between the two in order to correct

for survivorship bias, which we discuss later. Between

One consensus among previous authors is that the number of stocks outstanding in the past year and the

the measurement of IPOs’ long-term performance is number of stocks newly issued, we are able to estimate

extremely sensitive to both the sample firms and the the number of stocks that ceased trading (not delisted).

time period used in the studies. The reason is that firms In Exhibit 3, the final stocks included in our study

from the same industry tend to ‘IPO’ during the period are summarized. On average, there were 7,906 active

when the industry is doing better than the general stocks traded during a typical year, 7,540 new IPOs, and

market. Because all publicly traded stocks have at least 7,144 IPO stocks with an offer price above $1.00. Starting

one IPO, the entire historical U.S. stock universe, live in September 2011, the number of stocks increased across

or dead, is the IPO stock universe. Thus, to avoid the the board significantly as the OTC data became avail-

industry clustering and sampling bias issue, we elect to able to academics. Notably, there was a significant varia-

use the entire U.S. stock universe for our study. tion in the number of new issues coming to the market,

To that end, we start with any publicly traded consistent with the issuers’ timing based on the prior

stocks with price history from the usual academic industry performance. A more stable delisting pattern

databases—CRSP, COMPUSTAT, and DataStream— appears to be a result of general stock market movements.

and industry databases such as Morningstar, Thompson

Reuters, Bloomberg, and the OTC. The time period in EVENT-TIME VERSUS CALENDAR-TIME

our study is 1926 to 2015, and we identified all 67,260 PORTFOLIOS

stocks traded during that period. For reasons that will

soon be clear, the initial universe includes the price The issue of selecting the relevant time point is

history of both currently live (54%) and historically dead nontrivial. The standard “event-time” methodology

Summer 2017 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 141

Exhibit 3 Exhibit 4

IPO Universe Percentage of Dead IPOs

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

uses the IPO months as time zero, and the subsequent

return is averaged across all IPOs, obviously at different

historical calendar-time points. Because most IPOs have

been clustered over time, this approach may introduce

some biases in hypotheses testing. A wealth index is first computed for each stock

by comparing the current price by the IPO first-day

close price and averaging the index across the stocks.

BUY AND HOLD VERSUS The latter approach is often preferred because it com-

EQUAL-WEIGHTED RETURNS pounds the returns on the stock level. Though the

Tracking stock performance is always a tricky arithmetic return is known to bias the true return by

issue. The technology has been well developed in the understating (overstating) the negative (positive) returns,

IPO literature. In Equation 1, an arithmetic portfolio both measures suffer the same implementation issue of

return index is constructed by first equally weighting all costly monthly rebalancing.

IPO monthly returns at the same point in time, event

time or calendar time, and subsequently compounding SURVIVORSHIP BIAS

the average return over time:

Perhaps the word “survivorship” has originated

from IPOs. Young firms are notorious for their fragile

m

P

n

EWR t = ∏ 1 + ∑ it − 1 (1) life. Approximately 37,000 “dead” stocks have ceased

t =1 i =1 Pit −1 trading (Exhibit 4). Nearly 45% of this attrition was

due to involuntary unfavorable fundamentals, such as

Pit : price of stock i at month t since IPO financial distress, bankruptcy, or poor market condi-

n: number of IPO stocks tions because of failure in reporting or nontrading, while

m: number of months since IPOs. 55% of the dead stocks were associated with voluntary

changes in control, such as liquidation, mergers and

For comparison, Equation 2 constructs a buy-and- acquisitions, or exchanges. In Exhibits 4 and 5, the

hold portfolio index: average public life of an IPO is around 11.3 years, while

the majority ‘died’ within five years. As expected, there

n

Pit 1 is a relatively high attribution rate for young firms. IPO

HRRt = ∑ P (2)

i0 n

i =1 firms have a 10% chance of failure by the end of the first

year, 25% chance of failure by the end of the second year,

Pit : ith stock close at month t since IPO. and 50% chance of failure to the five-year anniversary.

Pi0 : close price of the first trading day. In contrast, while there is a 54% chance that a one-year

142 IPOs: The Third Year On Summer 2017

Exhibit 5 Finally, for all stocks whose prices become unavailable,

Number of Live IPOs and if the stocks were still within the first five-year

period after their IPOs, the remaining return data points

were “filled” in with the assumption that the stock

returns would be reduced at annual rates of 33%, so that

the stock value would go to zero after the three years of

untraceable delisting outcomes. Unlike previous studies

that assumed the delisted stocks would have market per-

formance with a zero excess return, our treatment is

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

more conservative by building in the natural demise of

dead stocks.

RISK-ADJUSTED PROCESS

One of the major reasons to account for the sig-

nificant inconsistencies in the magnitude of the post-

IPO long-term excess returns is the various risk-adjusted

old company will not survive the following five years,

procedures authors used. Most authors elected to use the

a 20-year old company has less than a 5% attrition rate

standard asset pricing models, such as the Capital Asset

for the same time period.

Pricing Model (CAPM) or versions of Fama–French,

For those firms that expired early, the subsequent

momentum, or liquidity risk factor models to adjust for

change in values after delisting is nontrivial. Stocks that

the systematic risks in the expected returns. However,

involuntarily delisted experienced drastic drops in value

we do not think that these conventional risk-adjusted

subsequent to the delisting. The average payoff values

procedures are sufficient to account for IPOs’ risk and

for bankrupt stocks have been in the order of 10%–15%

return tradeoffs. Similar to old companies in financial

of the last trading levels. For firms fortunate enough to

distress or in bankruptcy, the volatility or the risk of new

migrate from the major exchanges to the OTC markets,

young firms is mainly attributable to company-specific

“first print” prices were usually at around a 30% discount

idiosyncrasies, rather than the standard systematic

of the last trade prices. On the other hand, for stocks

market related risks.

that delisted voluntarily because of mergers and acquisi-

To illustrate the merit of this argument, we esti-

tions or going private, estimated subsequent shareholder

mate the average Fama–French, momentum, and

returns amounted to a 20%–30% premium over the last

liquidity risk factors (Equation 3 in the next paragraph)

publicly traded prices on the exchanges. However, we

for stocks the first two years out and then three to five

do not infer that the wealth effect between the different

years after their IPOs. The average risk factors across all

delisted groups will cancel each other if survivorship is

stocks in the two periods are summarized in Exhibit 6.

left unchecked. In fact, because there is a higher chance

Other than the size factor, which is consistent with the

that IPOs will be delisted and the resulting changes in

fact that most IPOs are small-capitalization stocks, the

values will be significant, the performance measurement

comparisons suggest that the systematic risk factors are

of the surviving stocks will be seriously overstated.

significantly lower in the first five years after the IPOs.

In our study, we elect to correct for the positive

In other words, the conventional measures of systematic

selection and survivorship bias inherent in the IPO

risk are less important for young public firms, espe-

universe using several procedures. For firms being del-

cially in the immediate time periods following the IPOs.

isted, every effort has been made to link the price data

This finding emphasizes the importance of diversifica-

from exchange to exchange listings in order to pre-

tion in IPO portfolios, including an adjustment of the

serve the longest live price history. For stocks that did

idiosyncratic risk more prevalent in the young stocks.

not have data available after the delisting, the resulting

In the absence of finding a convincing model to

valuation outcomes, if available, were identified—albeit

price the idiosyncratic risk, and being able to compare

liquidation, merger and acquisition, or bankruptcy.

our findings with previous studies, we reluctantly follow

Summer 2017 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 143

Exhibit 6

IPO Systematic Risk Models

Note: *** and ** represent the 1% and 5% significance levels.

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

the typical procedures used in the existing literature. and

Therefore, we estimate both the traditional CAPM as

n m

in Equation 3. For verification, we also construct a five- 1

CAR1t = ∑ ∏ (1 + εit )

factor model (FFSC) using Fama and French’s [1993] i =1 t =1 n

market risk, value risk, and size risk factors, Carhart’s

n m

[1997] momentum factor, and Pástor and Stambaugh’s 1

CAR2t = ∑ ∏ (1 + δit )

[2003] liquidity risk factors, as specified in Equation 4: i =1 t =1 n

Rit − R ft = α i + βi ( Rit − Rmt ) + εit (3)

EVENT-TIME VERSUS CALENDAR-TIME

Rit : Return on stock i for month t PORTFOLIOS

Rft : Risk free rate for month t

βi : Beta of the stock i In Exhibit 7, we first report the results for stock

Rmt : Market return returns over the same time period after their respective

IPO events. The first-year and second-year stock excess

and returns, subsequent to their IPOs, averaged around -1.1%

and -7.71%, with the equal-weighted portfolio returns

Rit − R ft = α i + βi ( Rmt − R ft ) + si SMBt + hi HML t lower than the buy-and-hold returns as expected.

Although our finding of IPOs’ early underperformance

+ miUMDt + li LIQt + δit (4)

is similar to most previous studies, the magnitude of

the negative excess returns is in the same order of the

where Rmt - Rft is the market excess return for month t,

findings reported by Ritter [2011], a more recent study

SMBt is the size risk premium, HMLt is the value risk

that has a slightly shorter time period (1980–2008) and

premium, UMDt is the momentum risk premium, and

a smaller sample size of 7,314. Moreover, the underper-

LIQt is the liquidity risk premium. The risk factors in

formance is robust regardless of how the performance

Equations 3 and 4 are estimated over the first five years

return is measured or how the return is risk adjusted.

of the IPOs. The conventional cumulative abnormal

However, the more fascinating result is on returns

returns CAR1 and CAR2, in equal-weighted basis and

from the third year on. While the third-year raw return

buy-and-hold basis, are calculated by compounding the

averaged 17%–18%, the excess return is between +1.74%

two monthly excess returns estimated using εit and δit

and +5.71%, statistically significant at the 1% level.

from Equations 3 and 4 in the following manner:

A similar pattern emerges in the fourth and f ifth

years. In Exhibits 8 and 9, the cumulative abnormal

m

n

ε

CAR1t = ∏ 1 + ∑ it returns are presented over the five-year period after

t =1 i =1 n the IPOs. On average, although the stocks underper-

formed 7% –9% the first two years, they outperformed

m

n

εit risk hurdles by somewhere between 15% –20% in the

CAR2t = ∏ 1 + ∑ n

t =1

following three years. All in all, IPOs outperformed

i =1

their risk benchmarks by a minimum of 5% over the

144 IPOs: The Third Year On Summer 2017

Exhibit 7

Event-Time Post-IPO Annual Returns

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

Note: T-statistics in the parentheses; *** and ** represent the 1% and 5% significance levels.

Exhibit 8 returns for stocks issued four years ago. A fourth-year

Event-Time Buy-and-Hold CARs return is also constructed for stocks issued three years

ago, and so on. Under the same calendar-time basis,

the next 12-month returns for the current month IPOs

become the first-year return index. Finally, the one- to

five-year return index is obtained by averaging over all

calendar months over the entire time period. Exhibit 11

shows the annual risk-adjusted excess returns for each of

the five years after the IPOs using a calendar-time basis.

In comparison to the event-time approach, in gen-

eral, the magnitude is less extreme in that the excess return

is f lat or around a slightly negative -1% to -2% for the

first two years and +10% for the remaining three years,

We note that the difference in magnitude between the

two approaches is understandable. Because most IPOs are

time clustered in the same industry, the calendar-time

portfolios are inevitably affected by the sector risk,

five years after their issuances. If this pattern holds, which is not fully accounted for. Exhibit 12 shows the

we begin thinking differently about IPOs. excess returns associated with five individual annual

To show further robustness, we replicated the same intervals over the calendar time. Exhibits 13 and 14 also

event-time tests in various 10-year calendar-time subpe- demonstrate the time-series patterns of the cumulative

riods. The findings are summarized in Exhibit 10. The abnormal returns on a calendar-time basis. Although it

qualitative result is remarkably consistent across most is seemingly more volatile over time, we still can draw

subperiods. From the third year on, the negative excess a similar qualitative conclusion that IPOs outperformed

returns stubbornly reversed to positive returns. from the third year on.8

We further test the “third-year and on returns”

using the calendar-time approach. In this case, we iden- LOTTERY-LIKE IPO RETURNS

tify stocks that were first issued during the previous

48-month period. A fifth-year annual portfolio return On the other hand, we are still puzzled by the

index is computed by averaging the next 12-month “consistency” found in this study and many previous

Summer 2017 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 145

studies showing that at least for the first two years, distributions are classif ied based on the particular

IPOs underperformed. It begs a simple question: why year since the IPOs. Using the buy-and-hold index,

does the underperformance still exist to this day? Or, we show that the 99th percentile IPO in a year pro-

why would anyone invest in IPOs during the first two duced over 2,770% in the first year, compared with

years, knowing that they will most likely deliver a subpar the average return in the same 99th percentile of 288%

performance? An intuitive answer is that investors may (Exhibit 15, Panel B). Further, the 288% return from

reckon that investing in IPOs is fundamentally synon- the top 1% IPO performers is approximately 29 times

ymous with playing a high-stakes lottery—paying to the average U.S. stock annual return. Other than the

play for extremely high potential returns with extremely fact that extreme IPOs produced nearly 10 times the

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

small odds. returns of the average (extreme) stocks, along with

To get some insight on this issue, we compare sharp declines in the superior returns over time, they

the return distributions between IPOs and seasoned indicate the lottery nature of the early IPO market.

stocks. In Exhibit 15, Panel A, IPO monthly return However, caution should be taken against overgeneral-

izing, as the IPO extreme return multiples drastically

dropped off just a few years out of the gate.

Exhibit 9 Collectively speaking, we have found stellar and

Event-Time Equal-Weighted CARs emerging evidence for the first time that IPOs have

excess returns after the second year—which challenges

the widely held idea that IPO returns are negative. More

specifically, IPOs, as a group, reverse their first two-

year stock return losses into gains in the following three

years. For the five years after going public, IPOs have

mildly outperformed their benchmarks. The reversal of

IPO returns is consistent with many hypotheses we pos-

ited. It may simply be a result of the information asym-

metry created during the IPO process finally dissipating

over time. It is also consistent with the argument that

the early loss in public shares is the one-time “price” the

private owners pay, in the form of public scrutiny, to get

access to public capital markets. As a result, the capital

Exhibit 10

Event-Time “Third-Year Returns” in Subperiods

Note: *** and ** represent the 1% and 5% significance levels.

146 IPOs: The Third Year On Summer 2017

and liquidity enable the young firms to grow at higher value on the option to go private, which helps explain

rates and produce positive excess stock returns. why the IPO stocks start turning around “later” in

A more elegant explanation is that the reversal of the game.

IPO returns is also consistent with the notion that the Similarly, our finding is consistent with the notion

decision to initiate IPOs, or go public, is the exercise of that the likelihood of going private can be predicted

the call option on the private value of the firm. Imme- at the point of the IPOs. Bharath and Dittmar [2010],

diately after the IPOs, the option to go public is replaced using a number of factors that were available at the

with an option to go private. The going-private option time of IPOs, were able to predict over 80% of the

is valued near zero, just because the likelihood of going future going-private decisions. On average, more than

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

private right after going public is near zero by definition. two-thirds of the IPOs that eventually go private will do

However, a fundamentally outperforming young firm so before the 13th year of their public life. It is reasonable

with stock market undervaluation will create positive to assume that the first two-year underperformance has

Exhibit 11

Calendar-Time Post-IPO Annual Returns

Notes: T-statistics in the parentheses; *** and ** represent the 1% and 5% significance levels.

Exhibit 12

Calendar-Time “Third-Year Returns” in Subperiods

Note: *** and ** represent the 1% and 5% significance levels.

Summer 2017 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 147

Exhibit 13 Exhibit 14

Calendar-Time Equal-Weighted CARs Calendar-Time Buy-and-Hold CARs

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

been a result of the low probability that the majority of OVERSTATING RISK RETURNS

the new IPOs will go private.

The less-pronounced negative excess return per-

formance in the first two years could also be explained

UNDERSTATING INDUSTRY EFFECT

by the different risk-adjusted procedures used. Most pre-

Our evidence may appear to be at odds with the vious studies elected to use a matching risk factor sample

majority of the previous findings that there is a long- to compare with the IPO sample. That is, each IPO stock

term post-IPO underperformance (Exhibit 2). Because was assigned and compared with one of the 25 Fama and

the difference could be academic, it warrants some MacBeth [1973] value/growth and large/small portfo-

academic discussions: First, as many previous studies lios. The expected or risk-adjusted returns were esti-

illustrate, as well as Exhibits 7 and 11, the conclusion mated using the ex ante systematic risk profile of IPOs.

can be very sensitive to the sample and the specific As shown in Exhibit 6, the ex post risk factors of early

time period used in each study. The common reason IPO years are 10%–50% significantly lower than in the

cited is that the IPOs, concentrating in one industry, later years. This, in turn, implies that the matching risk

tend to cluster one industry at a time. This clustering is procedure would have overestimated the risk-adjusted

also a result of issuers timing the issuances at the peak returns, or underestimated the excess returns.

of the seasoned stock performance. Because there is a An additional confirmation is that Ritter [2011]

documented industry effect, it is reasonable to expect found that the equal-weighted returns for the IPOs

that there is a horde of new issuances from a similar were -4.8% for the first year, -8.1% through the second

industry near the peak of industry performance. Fol- year, and -3.3% through the first five years. In his own cal-

lowing through with the same argument, we would culations, Ritter shows that the excess return between Year

also expect that the subsequent industry reversion alone 3 and Year 5 should be around +4.8%, which is remarkably

will produce the post IPOs’ underperformance, if the close to the same order of our estimates. We are pleased to

industry effect is not accounted for in the risk model. In see that Ritter—who has an almost 30-year career as the

almost all of the previous studies, the industry effect was leading authority on IPOs—said the following:

not accounted for in the risk model. Not surprisingly,

when Gompers and Lerner [2003] included an industry I have expressed support for the view that there

factor in the risk model, the negative excess returns dis- is little evidence that IPOs underperform in the

appeared. Our study, covering the entire 90-year IPO long run relative to other companies with sim-

universe, is not a concentrated industry sample. Thus, ilar characteristics, except for the sunsets of small

the result is less affected by this bias. companies (Ritter [2011, p. 28]).

148 IPOs: The Third Year On Summer 2017

Exhibit 15

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

In addition, the more encouraging message from than the otherwise private shares. This line of reasoning

our results is that there appears to be no inefficiency in would suggest that a positive stock return resulting from

the IPO market as is often implied in previous studies. such a branding effect should follow the IPO.

Many sensible arguments are offered to explain the During a typical life cycle, businesses raise capital

IPOs’ persistent initial underperformance and subse- first from friends and families, followed by venture

quent rebounds, which result in a reasonably muted capital, private equity, public equity, and back to pri-

mispricing over the entire five-year period; this is not vate equity, in that order. An IPO should be no more

considered a prolonged time interval to value the effi- than a funding or liquidity event, subject to market con-

ciency of an asset class. Even for the most aggressive ditions, just like any other seasoned issuances. In that

investors, investing in the first two-year IPO market, sense, IPOs’ underperformance due to the dilution after

with an expected 7% annual excess return but 200 times the IPOs’ issuances are understandable. Moreover, the

the top 1% IPO performance relative to the benchmark, impact of funding events should be temporary—and

should be fundamentally synonymous with playing a it should be reversed after two years. This long-term

high-stakes lottery—a paradigm that jives with previous investment prospect for IPOs is our most significant

research on IPO negative returns. finding.

Although the initial returns on IPOs appear disap-

A BRANDING EVENT OR A FUNDING EVENT pointing with underperformance around -5% for the

first two years, one may consider it an entrance ticket

Rational owners make calculated decisions at all price for private owners to “pay to play” in the public

times to increase their public or private share values. capital market, which some widely regard as a lottery.

Such decisions are invariably linked to the timing of However, the more interesting finding is that IPOs were

changing the form of business—that is, the timing to able to recoup more than their previously realized losses

go public (private). Therefore, the initiation of an IPO from the third year on. On average, IPO stocks outper-

symbolically declares the rite of passage for a young firm formed their counterparts by 5% a year from the third

gaining access to public capital markets or, more impor- year on and, in total, by a modest +6% excess return

tantly, signals that public shares will be worth more over the entire five-year period.

Summer 2017 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 149

ENDNOTES Amihud, Y., and H. Mendelson. “Liquidity and Asset Prices:

Financial Management Implications.” Financial Management,

The authors thank the Business Foundation at Stetson Vol. 17, No. 1 (1988), pp. 5-15.

University for its financial support. The research assistance

from Gonzalo Baudet and Christopher Landers is acknowl- Bharath, S.T., and A. Dittmar. “Why Do Firms Use Pri-

edged. The usual disclaimers apply. vate Equity to Opt Out of Public Markets?” The Review of

1

Ljungqvist [2007] provided a comprehensive review Financial Studies, Vol. 23, No. 1 (2010), pp. 1771-1818.

on the underpricing discount.

2

Ritter and Welch [2002] were somewhat surprised that Boot, A.W.A., R. Gopalan, and A. Thakor. “The Entrepre-

the anomaly still existed after Ritter’s [1991] published study. neur’s Choice between Private and Public Ownership.” The

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

Later it became the basis for Gompers and Lerner’s [2003] Journal of Finance, Vol. 61, No. 2 (2006), pp. 803-836.

study on a pre-NASD sample, and they concluded the same

result of underperformance. Booth, J.R., and L. Chua. “Ownership Dispersion, Costly

3

Underwriters usually insist on lockup agreements Information, and IPO Underpricing.” Journal of Financial

when managing IPOs. These agreements prevent corporate Economics, Vol. 41, No. 2 (1996), pp. 291-310.

insiders from selling their private stock for a set period fol-

lowing the IPO. The lockup period can vary, but is normally Brau, J.C., and S. Fawcett. “Initial Public Offerings: An Anal-

180 days. During this time, owners of private stock must hold ysis of Theory and Practice.” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 61,

onto their shares. Some states require lockup agreements, No. 1 (2006), pp. 399-436.

and the SEC mandates that the issuer publicly disclose the

terms of the lockup agreement. After the lockup period ends, Brau, J.C., B. Francis, and N. Kohers. “The Choice of IPO

corporate insiders can sell their shares to the public. versus Takeover.” The Journal of Business, Vol. 76, No. 4

4

Bharath and Dittmar [2010] did a comprehensive review (2003), pp. 583-612.

of theories about why firms go public. As there are no theories

of going private, they have reverse engineered a framework Brav, A., C. Geczy, and P. Gompers. “Is the Abnormal Return

from the going public models to predict firm’s going private. Following Equity Issuances Anomalous?” Journal of Financial

5

Purnanandam and Swaminathan [2004] argue a higher Economics, Vol. 56, No. 2 (2000), pp. 209-249.

future growth prospect to support the relative values between

public versus private shares. Brealey, R., H. Leland, and D. Pyle. “Information Asym-

6

For the 50-year period between 1965 and 2014, metries, Financial Structure, Financial Intermediation.” The

Berkshire has returned 1,826,163% to its shareholders, an Journal of Finance, Vol. 32, No. 2 (1977), pp. 371-387.

annual return of 21.6%, compared with the 9.9% S&P 500

total return (2016 Berkshire’s Shareholder Meeting). Buffett, W.E. BerkShire’s Shareholders Meeting, 2016.

7

The JOBS Act allows banks to publish research on an

IPO they are working on the day of the IPO or even ear- ——. BerkShire’s Annual Report. Letters to Shareholders,

lier. But banks, fearful of legal actions, wait exactly 25 days Berkshire Hathaway Inc., 2014. www.berkshirehathaway

before publishing. .com /Spec i a l L et ter s / W E B % 2 0 pa st % 2 0 pre sent % 2 0

8

Although, the calendar-time portfolio is more imple- future%202014.pdf.

mentable, the number of stocks in the portfolio is around

5–10 stocks, which is less desirable than that needed for diver- Carhart, M. “On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance.”

sifying the idiosyncratic risk often observed in the young The Journal of Finance, Vol. 52, No. 1 (1997), pp. 57-82.

IPOs.

Chambers, D., and E. Dimson. “IPO Underpricing over the

REFERENCES Very Long Run.” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 64, No. 3 (2009),

pp. 1407-1443.

Aggarwal, R., L. Krigman, and K. Womack. “Strategic IPO

Underpricing, Information Momentum, and Lockup Expi- Chemmanur, T.J., and P. Fulghieri. “A Theory of the Going-

ration Selling.” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 66, No. 1 Public Decision.” The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 12,

(2002), pp. 105-137. No. 2 (1999), pp. 249-279.

150 IPOs: The Third Year On Summer 2017

Chen, G., M. Firth, and J. Kim. “IPO Underpricing in Chi- Loughran, T., and J. Ritter. “The New Issues Puzzle.” The

na’s New Stock Markets.” Journal of Multinational Financial Journal of Finance, Vol. 50 (1995), pp. 23-51.

Management, Vol. 14, No. 3 (2004), pp. 283-302.

——. “Why Has IPO Underpricing Changed Over Time?”

Eckbo, B.E., and O. Norli. “Liquidity Risk, Leverage, and Financial Management, Vol. 33, No. 3 (2004), pp. 5-37.

Long-Run IPO Returns.” Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 11,

Nos. 1–2 (2005), pp. 1-35. Modigliani, F., and M. Miller. “Corporate Income Taxes and

the Cost of Capital: A Correction.” The American Economic

Ellul, A., and M. Pagano. “IPO Underpricing and After- Review, Vol. 53, No. 3 (1963), pp. 433-443.

Market Liquidity.” The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 19,

The Journal of Portfolio Management 2017.43.4:137-151. Downloaded from www.iijournals.com by CORNELL UNIVERSITY on 08/02/17.

It is illegal to make unauthorized copies of this article, forward to an unauthorized user or to post electronically without Publisher permission.

No. 2 (2006), pp. 381-421. Pástor, L., and R.F. Stambaugh. “Liquidity Risk and Expected

Stock Return.” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 111, No. 3

Fama, E.F., and K.R. French. “Common Risk Factors in the (2003), 642-685.

Returns on Bonds and Stocks.” Journal of Financial Economics,

Vol. 33, No. 1 (1993), pp. 3-56. Purnanandam, A., and B. Swaminathan. “Are IPOs Really

Underpriced?” The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 17, No. 3

Fama, E.F., and J. MacBeth. “Risk, Return, and Equilibrium: (2004), pp. 811-848.

Empirical Tests.” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 81, No. 3

(1973), pp. 607-636. Ritter, J.R. “The ‘Hot Issue’ Market of 1980.” The Journal of

Business, Vol. 57, No. 2 (1984), pp. 215-240.

Gompers, P.A., and J. Lerner. “The Really Long-Run Perfor-

mance of Initial Public Offerings: The Pre-Nasdaq Evidence.” ——. “The Long-Run Performance of Initial Public Offer-

The Journal of Finance, Vo. 58, No. 4 (2003), pp. 1355-1392. ings.” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 46, No. 1 (1991), pp. 3-27.

Ibbotson, R.G. “Price Performance of Common Stock New ——. “Equilibrium in the Initial Public Offerings Market.”

Issues.” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 2, No. 3 (1975), Annual Review of Financial Economics, Vol. 3, No. 1 (2011),

pp. 235-272. pp. 347-374.

Ibbotson, R.G., and J.Ritter. “Initial Public Offerings.” Ritter, J.R., and I. Welch. “A Review of IPO Activity,

Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science, Pricing, and Allocations.” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 57,

9 (1995), pp. 993-1016. No. 4 (2002), pp. 1795-1828.

Kim, W., and M. Weisbach. “Motivations for Public Equity Subrahmanyam, A., and S. Titman. “The Going-Public

Offers: An International Perspective.” Journal of Financial Decision and the Development of Financial Markets.” The

Economics, Vol. 87, No. 2 (2008), pp. 281-307. Journal of Finance, Vol. 54, No. 3 (1999), pp. 1045-1082.

Lee, P.J., S. Taylor, and T. Walter. “IPO Underpricing Expla- Teoh, S.H., I. Welch, and T.J. Wong. “Earnings Management

nations: Implications from Investor Application and Alloca- and the Long-Run Market Performance of Initial Public

tion Schedules.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Offerings.” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 53, No. 6 (1998),

Vol. 34, No. 4 (1999), pp. 425-444. pp. 1935-1974.

Liu, X., and J. Ritter. “Local Underwriter Oligopolies and Zingales, L. “Insider Ownership and Decision to Go Public.”

IPO Underpricing.” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 102, The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 62, No. 3 (1995),

No. 3 (2011), pp. 579-601. pp. 425-448.

Ljungqvist, A. “IPO Underpricing.” In B. Espen Eckbo, ed.,

Handbook of Corporate Finance: Empirical Corporate Finance. To order reprints of this article, please contact Dewey Palmieri

Amsterdam: North-Holland, 2007, pp. 377-422. at dpalmieri@ iijournals.com or 212-224-3675.

Logue, D. “On the Pricing of Unseasoned Equity Issues:

1965–1969.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis,

Vol. 8, No. 1 (1973), pp. 91-103.

Summer 2017 The Journal of Portfolio M anagement 151

You might also like

- Nollet 2015 - Handbook of Food Analysis PDFDocument1,531 pagesNollet 2015 - Handbook of Food Analysis PDFემილი ონოფრე100% (3)

- Andonov Et Al A Global Perspective On Pension Investments in Real EstateDocument11 pagesAndonov Et Al A Global Perspective On Pension Investments in Real EstateJuan Manuel FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Toward The Efficient Impact Frontier: FeaturesDocument6 pagesToward The Efficient Impact Frontier: Featuresguramios chukhrukidzeNo ratings yet

- Benchmark Construction and Performance Evaluation of Mezzanine Finance Funds - 2017Document7 pagesBenchmark Construction and Performance Evaluation of Mezzanine Finance Funds - 2017farid.ilishkinNo ratings yet

- Does Gender Matter?: Younger Generations' Investing Behaviors in Mutual FundsDocument11 pagesDoes Gender Matter?: Younger Generations' Investing Behaviors in Mutual FundsSanjita ParabNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Risky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceDocument10 pagesRisky Business: Intermediary Lending and Development FinanceOxfamNo ratings yet

- Climbing The Economic Ladder The Role of MicrofinaDocument20 pagesClimbing The Economic Ladder The Role of MicrofinaAmmi DonNo ratings yet

- Can Equity Crowdfunding CrowdOut Other Alternative Sources of FinanceDocument80 pagesCan Equity Crowdfunding CrowdOut Other Alternative Sources of FinanceJuanda erisman ErismanNo ratings yet

- Venture Capital and Private Equity Investment PrefDocument10 pagesVenture Capital and Private Equity Investment PrefHÒANo ratings yet

- Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC The Journal of Private EquityDocument15 pagesEuromoney Institutional Investor PLC The Journal of Private EquitynishthaNo ratings yet

- Angel NetworksDocument12 pagesAngel NetworksShashank SinghNo ratings yet

- Ampersand White Paper - Risk Contribution of StocksDocument16 pagesAmpersand White Paper - Risk Contribution of StockstabbforumNo ratings yet

- Wniter PDFDocument7 pagesWniter PDFpooja.yadav22No ratings yet

- Understanding Investment StrategyDocument1 pageUnderstanding Investment StrategySatheesh Kumar TNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 122.170.126.143 On Sun, 28 Mar 2021 09:32:50 UTCDocument5 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 122.170.126.143 On Sun, 28 Mar 2021 09:32:50 UTCGaurav AgrawalNo ratings yet

- The Green Register - Spring 2011Document11 pagesThe Green Register - Spring 2011EcoBudNo ratings yet

- Corporate Venture Funds Chase Early-Stage DealsDocument3 pagesCorporate Venture Funds Chase Early-Stage DealssalmaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Investors Perception Towards Mutual FuDocument9 pagesA Study On Investors Perception Towards Mutual FuRakshita ChaubeNo ratings yet

- A Study On Investor's Perception Towards Mutual Fund in The City of BhubaneswarDocument8 pagesA Study On Investor's Perception Towards Mutual Fund in The City of BhubaneswarAkhileshNo ratings yet

- New Capitalism by Shiller FAJ 2013Document5 pagesNew Capitalism by Shiller FAJ 2013gioro_miNo ratings yet

- Financial System FragilityDocument9 pagesFinancial System FragilityAlejandro CollazosNo ratings yet

- Venture Capital and Private Equity Investment Preferences in Selected CountriesDocument11 pagesVenture Capital and Private Equity Investment Preferences in Selected CountriesValeria VillacortaNo ratings yet

- 022 Article A003 enDocument4 pages022 Article A003 enPratyush KumarNo ratings yet

- Alternative Revenues:: Can Institutions of Higher Education Balance Mission and Financial Goals?Document9 pagesAlternative Revenues:: Can Institutions of Higher Education Balance Mission and Financial Goals?sadegaonkarNo ratings yet

- Blanchett 2014Document12 pagesBlanchett 2014jacekinneNo ratings yet

- Understanding and Optimising The Social Impact of Venture Capital: Three Lessons From GhanaDocument13 pagesUnderstanding and Optimising The Social Impact of Venture Capital: Three Lessons From Ghanabintangmba11No ratings yet

- The Influence of Exchange Rate, Interest Rate and Inflation On Stock Price of LQ45 Index in IndonesiaDocument7 pagesThe Influence of Exchange Rate, Interest Rate and Inflation On Stock Price of LQ45 Index in IndonesiaWiria SalvatoreNo ratings yet

- The Wealth Report 2020part 2Document4 pagesThe Wealth Report 2020part 2NameNo ratings yet

- AstudyonoverviewofinvestmentmanagementDr G KanagavalliDocument7 pagesAstudyonoverviewofinvestmentmanagementDr G KanagavalliSaurav RanaNo ratings yet

- The Bigger They Are... - Robert M. SolowDocument10 pagesThe Bigger They Are... - Robert M. SolowHELER DAVID CAMACHONo ratings yet

- Economic Capital 2 Venture Capital, Entrepreneurshipm and Economic GrowthDocument12 pagesEconomic Capital 2 Venture Capital, Entrepreneurshipm and Economic GrowthAxel William SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Fund Performance: Active Risk Budgeting in Action: Understanding HedgeDocument12 pagesFund Performance: Active Risk Budgeting in Action: Understanding Hedgewangshuqing97No ratings yet

- Errais - Turki - What Drives Value Creation in Healthcare Investments 20-07-2022Document16 pagesErrais - Turki - What Drives Value Creation in Healthcare Investments 20-07-2022Yasmine TurkiNo ratings yet

- Fernandez 2021Document18 pagesFernandez 2021Hanane KadiNo ratings yet

- JPSP - 2022 - 193Document5 pagesJPSP - 2022 - 193snehatiwari0426No ratings yet

- Seanet 09 Moneylending-in-BusinessDocument11 pagesSeanet 09 Moneylending-in-BusinessDinesh DesmondNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Financial Inclusion in Small and Medium Enterprises Evidence From EthiopiaDocument8 pagesDeterminants of Financial Inclusion in Small and Medium Enterprises Evidence From EthiopiaRajendra LamsalNo ratings yet

- Unlocking Impact Capital The Indian Family Office EditionDocument46 pagesUnlocking Impact Capital The Indian Family Office Editionabhishek.chauhanNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 125.166.149.106 On Tue, 19 Jul 2022 07:41:46 UTCDocument19 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 125.166.149.106 On Tue, 19 Jul 2022 07:41:46 UTCIvanaCalistaHasanNo ratings yet

- 2022 HwangDocument20 pages2022 HwangescrituralesNo ratings yet

- zz1s5dz Media PDFDocument16 pageszz1s5dz Media PDFsl7789No ratings yet

- Black 2013Document10 pagesBlack 2013jacekinneNo ratings yet

- Are You Really Ready For Private Equity - 2012Document4 pagesAre You Really Ready For Private Equity - 2012farid.ilishkinNo ratings yet

- Uncertainty and IPO Initial Returns Evidence From The Tone Analysis of China's IPO ProspectusesDocument74 pagesUncertainty and IPO Initial Returns Evidence From The Tone Analysis of China's IPO Prospectusesgogayin869No ratings yet

- Valuation and Performance of Reallocated IPO SharesDocument34 pagesValuation and Performance of Reallocated IPO Sharesgogayin869No ratings yet

- Underpricing of Initial Public OfferingsDocument82 pagesUnderpricing of Initial Public Offeringsgogayin869No ratings yet

- Value Relevance, Earnings Management and Corporate Governance in ChinaDocument46 pagesValue Relevance, Earnings Management and Corporate Governance in Chinagogayin869No ratings yet

- Underpricing of EuropeanDocument14 pagesUnderpricing of Europeangogayin869No ratings yet

- Underpricing and Underperformance of Swedish IPO'sDocument69 pagesUnderpricing and Underperformance of Swedish IPO'sgogayin869No ratings yet

- Why Do European Firms Go Public?: Franck BancelDocument41 pagesWhy Do European Firms Go Public?: Franck Bancelgogayin869No ratings yet

- Venture Capitalists and The Decision To Go PublicDocument24 pagesVenture Capitalists and The Decision To Go Publicgogayin869No ratings yet

- Underwriter Reputation, Earnings ManagementDocument26 pagesUnderwriter Reputation, Earnings Managementgogayin869No ratings yet

- Venture Capital Financing and TheDocument21 pagesVenture Capital Financing and Thegogayin869No ratings yet

- IPO Listings: Where and Why?: Anne M. Anderson and Edward A. DylDocument22 pagesIPO Listings: Where and Why?: Anne M. Anderson and Edward A. Dylgogayin869No ratings yet

- Venture Capitalist Participation and The Performance ofDocument20 pagesVenture Capitalist Participation and The Performance ofgogayin869No ratings yet

- Voluntary Management EarningsDocument27 pagesVoluntary Management Earningsgogayin869No ratings yet

- Firms in Transition: A Review of The Venture Capital, IPO, and M&A LiteratureDocument80 pagesFirms in Transition: A Review of The Venture Capital, IPO, and M&A Literaturegogayin869No ratings yet

- Video 15Document18 pagesVideo 15gogayin869No ratings yet

- Venture Capital, Corporate Governance, andDocument15 pagesVenture Capital, Corporate Governance, andgogayin869No ratings yet

- WhyIPO EFMASym2011bDocument46 pagesWhyIPO EFMASym2011bgogayin869No ratings yet

- 10 1111@jofi 12583Document48 pages10 1111@jofi 12583gogayin869No ratings yet

- 10 1111@ehr 12783Document20 pages10 1111@ehr 12783gogayin869No ratings yet

- Why Does Underperformance of IPOs in The Long-Run Become DebatableDocument13 pagesWhy Does Underperformance of IPOs in The Long-Run Become Debatablegogayin869No ratings yet

- WinnerscurseDocument27 pagesWinnerscursegogayin869No ratings yet

- Why Are IPOs Underpriced Evidence From Japan's Hybrid Auction-Method OfferingsDocument30 pagesWhy Are IPOs Underpriced Evidence From Japan's Hybrid Auction-Method Offeringsgogayin869No ratings yet

- Common Information Asymmetry Factors in Syndicated Loan StructuresDocument15 pagesCommon Information Asymmetry Factors in Syndicated Loan Structuresgogayin869No ratings yet

- What's in A Vote The Short - and Long-Run Impact of Dual-Class Equity On IPO Firm ValuesDocument22 pagesWhat's in A Vote The Short - and Long-Run Impact of Dual-Class Equity On IPO Firm Valuesgogayin869No ratings yet

- Capital Gains Tax Rates and The Cost of Capital For Small Business Evidence From The IPO MarketDocument24 pagesCapital Gains Tax Rates and The Cost of Capital For Small Business Evidence From The IPO Marketgogayin869No ratings yet

- Auctions Versus Book-Built IPOs in Japan A Comparison of Aftermarket VolatilityDocument12 pagesAuctions Versus Book-Built IPOs in Japan A Comparison of Aftermarket Volatilitygogayin869No ratings yet

- Who Are The Active Investors Evidence From Venture CapitalDocument25 pagesWho Are The Active Investors Evidence From Venture Capitalgogayin869No ratings yet

- An Empirical Examination of IPO Underpricing in The Chinese A-Share MarketDocument20 pagesAn Empirical Examination of IPO Underpricing in The Chinese A-Share Marketgogayin869No ratings yet

- An Evaluation of The Impact of Stock Market Reforms On IPO Under-Pricing in China The Certification Role of UnderwritersDocument14 pagesAn Evaluation of The Impact of Stock Market Reforms On IPO Under-Pricing in China The Certification Role of Underwritersgogayin869No ratings yet

- An Empirical Analysis On The Relationship Between IPO Waves and Market Timing On The Basis of Product Market Competition in ChinaDocument9 pagesAn Empirical Analysis On The Relationship Between IPO Waves and Market Timing On The Basis of Product Market Competition in Chinagogayin869No ratings yet

- Gomez V MontalbanDocument1 pageGomez V MontalbanShariefaAichaseAsaliNo ratings yet

- # Pembagian Kelas Alkes Per KategoriDocument41 pages# Pembagian Kelas Alkes Per KategoriR.A.R TVNo ratings yet

- The Literary Comparison Contrast EssayDocument7 pagesThe Literary Comparison Contrast EssayThapelo SebolaiNo ratings yet

- Mauro Giuliani: Etudes Instructives, Op. 100Document35 pagesMauro Giuliani: Etudes Instructives, Op. 100Thiago Camargo Juvito de Souza100% (1)

- ACA - Exam - Objectives - Photoshop - CC 2018Document5 pagesACA - Exam - Objectives - Photoshop - CC 2018Jeffrey FarillasNo ratings yet

- Full Download 2014 Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing Revised Reprint 5e Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download 2014 Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing Revised Reprint 5e Test Bank PDF Full Chapterpassim.pluvialg5ty6100% (17)

- The Ape-Man: His Kith and KinDocument128 pagesThe Ape-Man: His Kith and KinamitrupaniNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Inggris Lintas Minat X GenapDocument5 pagesBahasa Inggris Lintas Minat X GenapMeena ZahraNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Alternatives NotesDocument10 pagesComparison of Alternatives NotesLibyaFlowerNo ratings yet

- Assignment-II UNIT-I Topic: AveragesDocument3 pagesAssignment-II UNIT-I Topic: AveragesAjay JaginiNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Starbucks With The Coffee BeanDocument16 pagesComparison of Starbucks With The Coffee BeanshaiNo ratings yet

- General: Specific: Leading Statement:: TITLE: A Healthy LifestyleDocument2 pagesGeneral: Specific: Leading Statement:: TITLE: A Healthy LifestyleM Arshad M AmirNo ratings yet

- Comsys 2Document10 pagesComsys 2MarjorieNo ratings yet

- ModulationDocument7 pagesModulationSyeda MiznaNo ratings yet

- Karakteristik Material Baja St.37 Dengan Temperatur Dan Waktu Pada Uji Heat Treatment Menggunakan FurnaceDocument14 pagesKarakteristik Material Baja St.37 Dengan Temperatur Dan Waktu Pada Uji Heat Treatment Menggunakan FurnaceYudii NggiNo ratings yet

- Lessons & Carols Service 2017Document2 pagesLessons & Carols Service 2017Essex Center UMCNo ratings yet

- LED Large Digital Stopwatch Timer - Electronics USADocument5 pagesLED Large Digital Stopwatch Timer - Electronics USAmrdadeNo ratings yet

- VHDL Processes: Cwru Eecs 318Document24 pagesVHDL Processes: Cwru Eecs 318KarThikNo ratings yet

- Will or Going To 90069Document2 pagesWill or Going To 90069Dragana ZafirovskaNo ratings yet

- NG-PHC-PHC: C-DTP-DSRDocument4 pagesNG-PHC-PHC: C-DTP-DSRBisi AgomoNo ratings yet

- KELOMPOK 04 PPT AUDIT Siklus Perolehan Dan Pembayaran EditDocument39 pagesKELOMPOK 04 PPT AUDIT Siklus Perolehan Dan Pembayaran EditAkuntansi 6511No ratings yet

- Project On SunsilkDocument16 pagesProject On Sunsilkiilm00282% (22)

- GST/HST Credit Application For Individuals Who Become Residents of CanadaDocument4 pagesGST/HST Credit Application For Individuals Who Become Residents of CanadaAndrea Dr FanisNo ratings yet

- MOA Motorcycle PolicyDocument3 pagesMOA Motorcycle Policysanyo enterprise100% (2)

- Pre-Reading Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesPre-Reading Lesson Planapi-489274706No ratings yet

- Piano Pentatonic Blues Scales - Overview With PicturesDocument8 pagesPiano Pentatonic Blues Scales - Overview With PicturesВладимир Перминов100% (2)

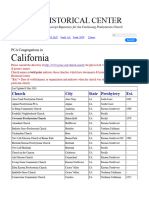

- PCA Churches in CaliforniaDocument4 pagesPCA Churches in CaliforniaLIGHT GNo ratings yet

- Me TurnoverDocument2 pagesMe TurnoverAparna ShajiNo ratings yet

- God Will Protect His Church God Will Protect His ChurchDocument17 pagesGod Will Protect His Church God Will Protect His ChurchLaura GarciaNo ratings yet