Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gastritis y Sarcina

Gastritis y Sarcina

Uploaded by

Dayana FajardoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 1 s2.0 S2352646718301509 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S2352646718301509 MainGilbert MenesesNo ratings yet

- Infectious IleoceicitisDocument2 pagesInfectious IleoceicitisYandiNo ratings yet

- Clinical, Imaging, and Endoscopic Profile of Patients With Abdominal TuberculosisDocument6 pagesClinical, Imaging, and Endoscopic Profile of Patients With Abdominal TuberculosisINDRINo ratings yet

- 299-Article Text-633-1-10-20200912Document5 pages299-Article Text-633-1-10-20200912daily of sinta fuNo ratings yet

- 16 3 2010 0350 0351 PDFDocument2 pages16 3 2010 0350 0351 PDFSandi ApriadiNo ratings yet

- Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults: A Case Series and Literature ReviwDocument6 pagesEosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults: A Case Series and Literature ReviwIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Granulomatous Appendicitis in A 12-Year-Old Boy: Derya Yayla, Bedriye Nuray Alpman, Yasemin DolekDocument3 pagesGranulomatous Appendicitis in A 12-Year-Old Boy: Derya Yayla, Bedriye Nuray Alpman, Yasemin Dolekansar ahmedNo ratings yet

- Pathologic Quiz Case: Residents' PageDocument4 pagesPathologic Quiz Case: Residents' Pagejeka222No ratings yet

- Dealmeida 2020Document3 pagesDealmeida 2020sukhmaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Diagnosis of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Intra Operative Findings and ComparisonDocument7 pages2014 Diagnosis of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Intra Operative Findings and ComparisonUrología GinecológicaNo ratings yet

- Tuberculous Ileal Perforation in Post-Appendicectomy PeriOperative Period: A Diagnostic ChallengeDocument3 pagesTuberculous Ileal Perforation in Post-Appendicectomy PeriOperative Period: A Diagnostic ChallengeIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- J Epsc 2015 05 012Document4 pagesJ Epsc 2015 05 012Hanung PujanggaNo ratings yet

- Jejunojejunal Intussusception As Initial Presentation of Coeliac Disease: A Case Report and Review of LiteratureDocument6 pagesJejunojejunal Intussusception As Initial Presentation of Coeliac Disease: A Case Report and Review of Literatureellya theresiaNo ratings yet

- 1-3-JMCRCS2024040906 Revised - Galley - Proof - 1715425008Document2 pages1-3-JMCRCS2024040906 Revised - Galley - Proof - 1715425008ILBS M.Sc. NursingNo ratings yet

- Cytomegalovirus-Associated Protein-Losing Gastropathy (Menetrier's Disease) in ChildhoodDocument3 pagesCytomegalovirus-Associated Protein-Losing Gastropathy (Menetrier's Disease) in ChildhoodGilbert MenesesNo ratings yet

- Successful Management of Giant Hydrocolpos in A LiDocument3 pagesSuccessful Management of Giant Hydrocolpos in A LiVictor FernandoNo ratings yet

- Gastroschisis: Case ReportDocument2 pagesGastroschisis: Case ReportMuhammad Syamil RozlanNo ratings yet

- Adult Intussusception A Case ReportDocument4 pagesAdult Intussusception A Case ReportRahmanssNo ratings yet

- Jurnal - Tuba Ovarii Abses - Anisa Ryani MafitriDocument7 pagesJurnal - Tuba Ovarii Abses - Anisa Ryani MafitriBagus Indra KusumaNo ratings yet

- Absceso Hepático NeonatalDocument6 pagesAbsceso Hepático NeonatalNabila Peña ZapataNo ratings yet

- Gastroenteritis Eosinofílica: Aspectos Clínicos e Imagenológicos de Una Entidad Poco Frecuente, Reporte de CasoDocument5 pagesGastroenteritis Eosinofílica: Aspectos Clínicos e Imagenológicos de Una Entidad Poco Frecuente, Reporte de CasoSilvana zeta garciaNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1701216315302577Document4 pagesPi Is 1701216315302577rio rumaropenNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Gastritis, Gastropathy, and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Education GapDocument10 pagesPediatric Gastritis, Gastropathy, and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Education GapvgmanjunathNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Ascites in Children As The Presentation of Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: A Surgeon's PerspectiveDocument6 pagesAbdominal Ascites in Children As The Presentation of Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: A Surgeon's PerspectiveIulia CeveiNo ratings yet

- Dialnet ReporteDeCaso 8584573Document7 pagesDialnet ReporteDeCaso 8584573Astrid VélizNo ratings yet

- Gastritis and Gastropathy Perspectives From The EndoscopistDocument4 pagesGastritis and Gastropathy Perspectives From The Endoscopisthenrique.uouNo ratings yet

- Endoscopia: Diagnostic Approach of Intestinal Tuberculosis: Case and Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesEndoscopia: Diagnostic Approach of Intestinal Tuberculosis: Case and Literature ReviewDumitru RadulescuNo ratings yet

- Acute Gastric Dilatation in ChildrenDocument6 pagesAcute Gastric Dilatation in ChildrenAkbar TabletNo ratings yet

- Calcagno 2018Document10 pagesCalcagno 2018cut normaya putriNo ratings yet

- MRSAcolitisGastroenterol Report2015Document4 pagesMRSAcolitisGastroenterol Report2015selandia nisrinaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Teniasis During A Convencional Gastroplasty: Case ReportDocument3 pagesDiagnosis of Teniasis During A Convencional Gastroplasty: Case ReportHugo Whysk LeonardoNo ratings yet

- Ajg 2009 524Document10 pagesAjg 2009 524Alex Cristian IonutNo ratings yet

- Peptic Ulcer Disease in Chil Den: Gastroenterology Department Mingfang Sun 2020.7.7Document23 pagesPeptic Ulcer Disease in Chil Den: Gastroenterology Department Mingfang Sun 2020.7.7Clifford MartinNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading AnakDocument19 pagesJournal Reading AnakPutra Priambodo WibowoNo ratings yet

- What S Hidden Under The Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Diffuse Type Adenocarcinoma Discovered by Targeted Biopsies A Case ReportDocument4 pagesWhat S Hidden Under The Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Diffuse Type Adenocarcinoma Discovered by Targeted Biopsies A Case ReportHerald Scholarly Open AccessNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guidelines Secondary Prevention of Gastric CancerDocument1 pageClinical Guidelines Secondary Prevention of Gastric Cancerhenrique.uouNo ratings yet

- Verrucous Antral Gastritis in Relation To Helicobacter Pylori Infection, Nutrition, and Gastric AtrophyDocument6 pagesVerrucous Antral Gastritis in Relation To Helicobacter Pylori Infection, Nutrition, and Gastric AtrophySST KNo ratings yet

- Development of Type I Gastric Carcinoid in Patients With Chronic Atrophic GastritisDocument9 pagesDevelopment of Type I Gastric Carcinoid in Patients With Chronic Atrophic GastritisAbristaSeptikasariNo ratings yet

- Case Report Vella NurfatimahDocument4 pagesCase Report Vella NurfatimahVella NurfatimahNo ratings yet

- Medicine: A Newborn Patient With Both Annular Pancreas and Meckel 'S DiverticulumDocument5 pagesMedicine: A Newborn Patient With Both Annular Pancreas and Meckel 'S DiverticulumAdrian UmbriaNo ratings yet

- A Neonatal Septic Arthritis Case Caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae - A Case ReportDocument2 pagesA Neonatal Septic Arthritis Case Caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae - A Case Reportkartini ciatawiNo ratings yet

- Pamj 12 65Document5 pagesPamj 12 65Iwi DancelNo ratings yet

- Gastritis - Facts and Doubts: Original PaperDocument10 pagesGastritis - Facts and Doubts: Original Paperindah setiyaniNo ratings yet

- Adult Idiopathic Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis A Common Presentation With An Uncommon DiagnosisDocument5 pagesAdult Idiopathic Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis A Common Presentation With An Uncommon DiagnosiszapomannNo ratings yet

- Revista Gastroenterologia Mexico: Scientific LetterDocument4 pagesRevista Gastroenterologia Mexico: Scientific LetterPriyanshu SinghNo ratings yet

- Management of Perforated Appendicitis in Children: A Decade of Aggressive TreatmentDocument5 pagesManagement of Perforated Appendicitis in Children: A Decade of Aggressive Treatmentapi-308365861No ratings yet

- Case Report Proteus Species Infection: A Diagnostic DilemmaDocument5 pagesCase Report Proteus Species Infection: A Diagnostic DilemmaTengku AdriansyahNo ratings yet

- Document 1Document4 pagesDocument 1arditia dwiNo ratings yet

- An Unusual Case of Nonsurgical Pneumoperitoneum in A Pediatric P 2023 BurnsDocument5 pagesAn Unusual Case of Nonsurgical Pneumoperitoneum in A Pediatric P 2023 BurnsAdrian MoralesNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Peritonitis in Patients With Scrub TyphusDocument3 pagesCase Report: Peritonitis in Patients With Scrub TyphusJasleen KaurNo ratings yet

- ургентна хирург тесты англ. 2011Document65 pagesургентна хирург тесты англ. 2011Cynthia GNo ratings yet

- The Rapunzel Syndrome - A Case Report: Trichobezoar As A Cause of Intestinal PerforationDocument4 pagesThe Rapunzel Syndrome - A Case Report: Trichobezoar As A Cause of Intestinal PerforationSajag GuptaNo ratings yet

- Annals of Medicine and SurgeryDocument3 pagesAnnals of Medicine and SurgeryTiti PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Tubular Ileal Duplication Causing Small Bowel Obstruction in A ChildDocument5 pagesTubular Ileal Duplication Causing Small Bowel Obstruction in A ChildDiego Leonardo Herrera OjedaNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Septic AbortionDocument4 pagesCase Study - Septic AbortionHoneylyn100% (1)

- Clostridium DifficileDocument6 pagesClostridium DifficileNutricionista Cinthia Toledo SalazarNo ratings yet

- Mesenteric Cyst Infected With: Salmonella TyphimuriumDocument2 pagesMesenteric Cyst Infected With: Salmonella TyphimuriumAbhishek Soham SatpathyNo ratings yet

- Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical SciencesDocument6 pagesResearch Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical SciencesSurajit SahaNo ratings yet

- Corpus GastritisDocument5 pagesCorpus Gastritisameer143No ratings yet

- Colitis: A Practical Approach to Colon and Ileum Biopsy InterpretationFrom EverandColitis: A Practical Approach to Colon and Ileum Biopsy InterpretationAnne Jouret-MourinNo ratings yet

- Law & Corporate FinanceDocument238 pagesLaw & Corporate FinanceRajesh Shantaram Shinde100% (1)

- Csir TransDocument11 pagesCsir TransRamish KhanNo ratings yet

- DR Niharika Maharshi Sharma ResumeDocument6 pagesDR Niharika Maharshi Sharma ResumeMSSPSNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Experimental Investigation of ConcreteDocument7 pagesA Comparative Experimental Investigation of ConcreteSafwat El RoubyNo ratings yet

- 4 January Personality - Google Search PDFDocument1 page4 January Personality - Google Search PDFNxxr Xleyxh chanelNo ratings yet

- Students' Perceptions of The Twists and Turns of E-Learning in The Midst of The Covid 19 OutbreakDocument12 pagesStudents' Perceptions of The Twists and Turns of E-Learning in The Midst of The Covid 19 OutbreakMajor HariezNo ratings yet

- Amazing Race GuidelinesDocument10 pagesAmazing Race GuidelinesVince Nicole LomocsoNo ratings yet

- Departmental Interpretation and Practice NotesDocument19 pagesDepartmental Interpretation and Practice NotesDifanny KooNo ratings yet

- Architectural Journalism - A View PointDocument2 pagesArchitectural Journalism - A View PointShaurya Chauhan100% (3)

- A Conceited Mistake by Vasko PopaDocument1 pageA Conceited Mistake by Vasko PopaIvana NIkolicNo ratings yet

- Create A Watson Assistant Instance: Lab 1: Creating Watson InstancesDocument7 pagesCreate A Watson Assistant Instance: Lab 1: Creating Watson InstancesErosNo ratings yet

- Richard-2019-9-29 - (PO 1048) PDFDocument1 pageRichard-2019-9-29 - (PO 1048) PDFLeslie Ali TapodocNo ratings yet

- Bagaimana Pendalaman Keuangan Dan Cadangan Devisa Mempengaruhi Stabilitas Nilai Tukar Di NEGARA EMERGING MARKET? (Pendekatan Panel ARDL)Document9 pagesBagaimana Pendalaman Keuangan Dan Cadangan Devisa Mempengaruhi Stabilitas Nilai Tukar Di NEGARA EMERGING MARKET? (Pendekatan Panel ARDL)Yanri DayaNo ratings yet

- Nooyen - Nursery TRIBARDocument1 pageNooyen - Nursery TRIBARRicardo Diaz NiñoNo ratings yet

- CitiesDocument1,468 pagesCitiesAlexandru BizoiNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of RepugnancyDocument13 pagesDoctrine of RepugnancyAmita SinwarNo ratings yet

- AaaDocument45 pagesAaaPriya NairNo ratings yet

- English Essay ExmDocument20 pagesEnglish Essay ExmHassanatulNo ratings yet

- Md. Shahriar Alam: Career ObjectiveDocument4 pagesMd. Shahriar Alam: Career ObjectiveAdnanNo ratings yet

- Hindyati RachmahDocument9 pagesHindyati RachmahhindyatiadtNo ratings yet

- DragonMech - Steam WarriorsDocument127 pagesDragonMech - Steam Warriorsc1768152100% (5)

- April 6, 2020: Laboratory Assignment: TrematodesDocument9 pagesApril 6, 2020: Laboratory Assignment: Trematodesthe someoneNo ratings yet

- Tertullian The African An Anthropological ReadingDocument236 pagesTertullian The African An Anthropological Readingz100% (3)

- WACOM 2017 Org ChartDocument21 pagesWACOM 2017 Org ChartLeonorin FchNo ratings yet

- 10.women LeadershipDocument26 pages10.women LeadershipAbhir Raj ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Seawright Women of Distinction Awards Ceremony BookletDocument28 pagesSeawright Women of Distinction Awards Ceremony BookletrooseveltislanderNo ratings yet

- Constitutional InterpretationDocument13 pagesConstitutional InterpretationAndrew SekayiriNo ratings yet

- Tiểu luận TemplateDocument7 pagesTiểu luận TemplateThảo NguyênNo ratings yet

- What Is Letter?Document4 pagesWhat Is Letter?Angelly V VelascoNo ratings yet

- Inglês 11 Classe (Textos Editores) PDFDocument180 pagesInglês 11 Classe (Textos Editores) PDFNota Joao Tembo50% (2)

Gastritis y Sarcina

Gastritis y Sarcina

Uploaded by

Dayana FajardoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gastritis y Sarcina

Gastritis y Sarcina

Uploaded by

Dayana FajardoCopyright:

Available Formats

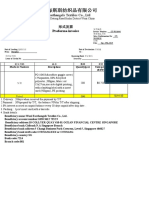

Case Report

published: 30 August 2017

doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00145

Ulcerative Gastritis and

esophagitis in two Children

with Sarcina ventriculi Infection

Tim G. J. de Meij 1*, Michiel P. van Wijk1, Aart Mookhoek 2 and Andries E. Budding3

1

Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology, VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2 Department of

Pathology, VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 3 Department of Medical Microbiology and Infection

Control, VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Sarcina ventriculi is a Gram-positive, obligate anaerobic coccus, with a characteristic

morphology. Only 22 cases of human infections by this microorganism, including 7

in children, have been reported in literature so far. Affected subjects usually present

with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and delayed gastric emptying. However,

life-threatening complications, like emphysematous gastritis and gastric perforation

have also been described. Gastroparesis and gastric outlet obstruction have been con-

sidered as a potential etiologic factor. All pediatric cases described thus far presented

Edited by:

with concomitant gastrointestinal pathology, such as Helicobacter pylori gastritis, celiac

Margaret Ip,

The Chinese University of disease, infection with Giardia lamblia or Candida spp. Here, we report two children

Hong Kong, Hong Kong with S. ventriculi infection, in whom the diagnosis was established by typical histological

Reviewed by: findings in mucosal biopsies. The first child presented with hematemesis due to ulcer-

Aleksandra Barac,

University of Belgrade,

ative esophagitis and gastritis, the second child with a history of esophageal stricture

Serbia had ulcerative gastritis. Confirmation of S. ventriculi infection is feasible by molecular

Veranja Liyanapathirana,

microbiota detection methods, since this microorganism cannot be detected by classi-

University of Peradeniya,

Sri Lanka cal culture techniques. Prompt treatment with antibiotics could prevent life-threatening

*Correspondence: complications.

Tim G. J. de Meij

t.demeij@vumc.nl Keywords: esophagitis, children, microbiota, IS-pro, Sarcina ventriculi, gastritis

Specialty section: INTRODUCTION

This article was submitted to

Infectious Diseases – Surveillance, Sarcina ventriculi is a Gram-positive, obligate anaerobic coccus, present in the soil, with a char-

Prevention and Treatment, acteristic tetrad or octet morphology. Only 22 cases of human infections by this microorganism,

a section of the journal including 7 children, have been described in literature to date. The majority of cases presented

Frontiers in Medicine with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and delayed gastric emptying. In a few cases, infection was

Received: 22 June 2017 associated with life-threatening complications, like emphysematous gastritis and gastric perforation.

Accepted: 16 August 2017 Here, we report two children with a S. ventriculi infection in whom the diagnosis could be made on

Published: 30 August 2017

typical histological findings in the mucosal biopsies. The first child presented with hematemesis due

Citation: to ulcerative esophagitis and gastritis, the second child with a history of esophageal stricture had

de Meij TGJ, van Wijk MP, ulcerative gastritis. In both children, symptoms resolved completely following targeted antibiotics.

Mookhoek A and Budding AE (2017)

Ulcerative Gastritis and

Esophagitis in Two Children with CASE PRESENTATION

Sarcina ventriculi Infection.

Front. Med. 4:145. The first patient was a 12-year old girl with a history of psychomotor retardation and refractory

doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00145 epilepsy based on West syndrome. Furthermore, she was diagnosed twice with an episode of

Frontiers in Medicine | www.frontiersin.org 1 August 2017 | Volume 4 | Article 145

de Meij et al. Esophagitis and Gastritis by S. ventriculi

Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis, successfully eradicated hemorrhagic antral and corporal gastritis was observed (Figure 3),

with triple therapy on both occasions. Percutaneous endoscopic next to two circular antral ulcers with a diameter of 5 mm. Notably,

gastrostomy (PEG) was performed early in life for long-term a large amount of stomach retention was observed, indicative for

administration of enteral nutrition. She was admitted to delayed gastric emptying. Histological examination of esopha-

the hospital because of mild dehydration due to intractable geal and gastric biopsies showed severe ulcerative esophagitis

vomiting since 3 days, possibly including blood. Aspiration of and gastritis, next to the presence of bacteria in the gastric and

stomach content via the PEG tube revealed retention of a large esophageal mucous surface. The bacteria were arranged in tetrad

amount of brownish fluid. On physical examination, the patient and octet groups, compatible with S. ventriculi (Figures 4A,B).

was tachycardic (110 beats/min), with normal blood pressure H. pylori was not observed.

and oxygen saturation. Palpation of the abdomen was not Culture of the mucosal biopsies was negative, including cul-

painful, and no other physical signs were present, besides her ture for H. pylori. Subsequently, we applied a molecular micro-

pre-existent neurological impairment. Laboratory investigation biota profiling technique, called IS-pro, which confirmed the

showed normal hemoglobin concentration (9.5 mmol/l), mean presence of S. ventriculi. Patient was treated with ciprofloxacin

cellular volume 94 fl, normal platelet count, and normal infec- and metronidazole for 10 days and the symptoms of bloody

tion and clotting parameters. At admission, she was already on stomach retention and hematemesis resolved completely

omeprazole (20 mg/day), next to phenobarbital and gabapentin within several days. Control esophagogastroduodenoscopy

as antiepileptic treatment. Differential diagnosis included performed after 6 weeks showed complete healing of the

Mallory–Weiss syndrome, viral gastro-enteritis, esophagitis, gastric and esopgaheal mucosa. In the mucosal biopies, S. ven-

recurrence of H. pylori-associated ulcer/gastritis, and bleeding triculi could no longer be detected. Duration of follow-up was

from esophageal varices. Portal hypertension was excluded by 12 months, during which period no recurrence of symptoms

abdominal ultrasound and H. pylori antigen stool test was nega- was reported.

tive. Omeprazole was increased to 40 mg/day. No hematemesis

was observed during the 3 days of admission, and therefore,

esophagogastroduodenoscopy was not performed. After Case 2

1 month, the patient was readmitted because of status epilepti- The second patient was a 15-year-old Caucasian girl with a history

cus, possibly due to insufficient intake of antiepileptic medica- of severe neurological impairment and epilepsy due to intracra-

tion linked to a gradual increase of vomiting. Convulsions were nial hemorrhage from a cerebral arteriovenous malformation

adequately treated with intravenously administered midazolam. at 8 years of age. She was prescribed Clobazam and Keppra as

Three days prior to this second admission, the mother of the antiepileptic agents and had a PEG tube for administration of

patient had aspirated large amounts of bloody retention from the enteral nutrition. She presented with respiratory failure due to

stomach, but the hemoglobin level was not decreased compared an aspiration pneumonia, for which mechanical ventilation

to the previous admission. One day following this second admis- was required. Because of the inability to insert a nasogastric

sion, the patient had an episode of hematemesis, and therefore, tube during admission, a single-contrast study of the esophagus

a esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed under general was performed, which showed a mid-esophageal stricture over

anesthesia. A timeline displaying the course of clinical symp- a length of 10 cm. An upper endoscopy was performed which

toms is depicted in Figure 1. confirmed the presence of a mid-esophageal pinpoint stenosis.

Endoscopy showed a severe, erosive esophagitis of the distal Endoscopy was also performed through the gastrocutaneous

15 cm of the esophagus (Figure 2). Furthermore, a multifocal fistula for retrograde inspection of the distal esophagus. Here,

Figure 1 | Timeline displaying the course of clinical symptoms of case 1.

Frontiers in Medicine | www.frontiersin.org 2 August 2017 | Volume 4 | Article 145

de Meij et al. Esophagitis and Gastritis by S. ventriculi

Figure 2 | Erosive esophagitis.

Figure 4 | Sarcina ventriculi in esophageal biopsies. These microorganisms

appear to be arranged in tetrads [(A) 200×], but on higher magnification

appear to be arranged in cubes composed of eight individual spheres

[(B) 400×].

Figure 3 | Erosive gastritis.

we observed a diffuse erosive gastritis and a large gastric circular

ulcer with a diameter of 10 mm at the gastro-esophageal junc-

tion with no signs of esophagitis (Figure 5). Furthermore, a

significant amount of stomach retention was seen, despite 12 h

of fasting, suggestive of delayed gastric emptying. Histological

examination of gastric biopsies showed active gastritis with the

presence of microorganisms arranged in tetrads, characteristic

of S. ventriculi, which was confirmed by the IS-pro technique.

H. pylori and Giardia lamblia were not detected. The patient was

prescribed ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for 10 days, next Figure 5 | Circular gastric ulcer.

to omeprazole (40 mg/day). At endoscopic follow-up 6 weeks

following antibiotics, the gastritis and gastric ulcer were healed

completely and S. ventriculi could no longer be detected from A timeline with the course of clinical symptoms is depicted in

the biopsies. Endoscopic dilatation of the esophageal stricture Figure 6. During follow-up period of 8 months, no recurrence

was successfully performed using Savary-Gilliard bougies. was reported.

Frontiers in Medicine | www.frontiersin.org 3 August 2017 | Volume 4 | Article 145

de Meij et al. Esophagitis and Gastritis by S. ventriculi

Figure 6 | Timeline displaying the course of clinical symptoms of case 2.

DISCUSSION and none of them had hematemesis as presenting symptom

(7, 8). Cultivation of S. ventriculi is complicated by its complex

In 1842, John Goodsir was the first to describe the presence of nutritional requirements, but diagnosis can usually be made

Sarcina microorganisms in the stomach of a patient presenting based on typical morphological features (11). Diagnosis can be

with abdominal pain, bloating, and vomiting (1). The patho- confirmed by means of molecular techniques like sequencing

genic role of S. ventriculi has been well established in the vet- or, as in our case, by IS-pro, a eubacterial DNA-based molecu-

erinary literature, including description of several fatal cases, lar detection technique (23). IS-pro is based on identification

called “abomasal bloat,” in livestock (2, 3). Its pathogenicity of species-specific length polymorphisms of the interspacer

in humans has been questioned until recent years, since only region and phylum-specific sequence polymorphisms of 16S

few symptomatic infections with Sarcina organisms in humans rDNA. Treatment of S. ventriculi usually consists of proton

have been described, only 22 cases in literature so far (4–18), pump inhibitors and antibiotics, with metronidazole and cip-

while S. ventriculi has also been detected in asymptomatic rofloxacin as most frequently prescribed agents (3, 19). In our

subjects (19, 20). Sites of infections described thus far include first case description, the patient was already on proton pump

the stomach (85%), esophagus (10%), and duodenum (5%) inhibitors prior to onset of complaints, and she recovered

(21). Presenting symptoms in patients with S. ventriculi com- both clinically and endoscopically following administration of

monly include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and, as in ciprofloxacin and metronidazole.

our case, delayed gastric emptying (8, 9). Severe complications The association between S. ventriculi infections and

like emphysematous gastritis and gastric perforation have also esophageal strictures, as described in case 2, has already been

been reported (4, 5). It has been suggested that impaired gastric described over a century ago (22). In an intriguing experiment

emptying could be a risk factor for the growth of S. ventriculi by Beijerinck et al. performed in 1911 under strict anaerobic

(8, 9). The majority of affected patients do not have mucosal conditions to prove the similarity between S. ventriculi isolated

injury on endoscopy, but increasing evidence suggests that from garden soil and from stomach contents, the researchers

S. ventriculi is associated with gastric ulcers, with an incidence used from stomach contents from patients with esophageal

of over 30% in Sarcina infections, and subsequently with an stenosis and suffering from S. ventriculi infection (22). This asso-

increased risk for emphysematous gastritis and gastric perfora- ciation has not been described in subsequent reports on human

tion (7, 21). Only seven children with symptomatic S. ventriculi S. ventriculi infections. In case 2, S. ventriculi was detected in

infection have been described in literature so far (5–7, 11, 12, mucosal biopsies from the stomach, but not from the esophagus.

22), two of them presenting with (partial) gastric necrosis. We, therefore, believe that S. ventriculi infection is more likely to

Notably, all described children had a concurrent gastrointes- be a consequence rather than a cause of esophageal strictures;

tinal disease, including H. pylori gastritis (n = 2), infection severe stenosis may create optimal anaerobic conditions for

with G. lamblia or Candida spp., history of esophageal atresia S. ventriculi to grow.

and post gastric pull through with anastomotic narrowing, In conclusion, S. ventriculi infection is a rare cause of ulcera-

and celiac disease. Our first case had no (recognized) gastro- tive gastritis and esophagitis in children, with delayed gastric

intestinal diagnosis, both cases had a PEG tube placement for emptying as possible predisposing factor. Diagnosis is usually

administration of enteral nutrition. An association between a established by typical histological findings and can be confirmed

PEG tube and S. ventriculi infection has not been described by means of molecular detection techniques. Since infection

previously. In three of seven affected children described in lit- may lead to life-threatening complications, it should be treated

erature, endoscopy revealed the presence of distal esophagitis promptly with proton pump inhibitor and antibiotics.

Frontiers in Medicine | www.frontiersin.org 4 August 2017 | Volume 4 | Article 145

de Meij et al. Esophagitis and Gastritis by S. ventriculi

ETHICS STATEMENT AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommenda- TM is treating physician of described patients and wrote

tions of the Ethical Commitee VU University medical center with first draft of the manuscript. MW performed the endosco-

written informed consent from all included subjects. The parents pies and critically assessed the manuscript. AM performed

of these subjects gave written informed consent in accordance histological analyses and critically assessed the manuscript.

with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by AB performed microbiota analysis and critically assessed the

the Ethical Commitee VU University medical center. manuscript.

REFERENCES 14. Carrigan S, Grin A, Al-Haddad S, Iakovlev V, Streutker C, Moore T, et al.

Emphysematous oesophagitis associated with Sarcina organisms in a patient

1. Goodsir J. History of a case in which a fluid periodically ejected from the receiving anti-inflammatory therapy. Histopathology (2015) 67:270–2.

stomach contained vegetable organisms of an undescribed from. Edinb Med doi:10.1111/his.12599

Surg J (1842) 57:430–43. 15. Berry AC, Mann S, Nakshabendi R, Kanar O, Cruz D. Gastric Sarcina

2. Edwards GT, Woodger NG, Barlow AM, Bell SJ, Harwood DG, Otter A, et al. ventriculi: incidental or pathologic? Ann Gastroenterol (2015) 28:495.

Sarcina-like bacteria associated with bloat in young lambs and calves. Vet Rec 16. Chougule A, Muthu V, Bal A, Rudramurthy SM, Dhooria S, Das A, et al.

(2008) 163:391–3. doi:10.1136/vr.163.13.391 Pulmonary gangrene due to Rhizopus spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella

3. Marshall TS. Abomasal ulceration and tympany of calves. Vet Clin North Am pneumoniae and probable Sarcina organisms. Mycopathologia (2015)

Food Anim Pract (2009) 25:209–20. doi:10.1016/j.cvfa.2008.10.010 180:131–6. doi:10.1007/s11046-015-9904-3

4. Tuuminen T, Suomala P, Vuorinen S. Sarcina ventriculi in blood: the 17. Sopha SC, Manejwala A, Boutros CN. Sarcina, a new threat in the bariatric era.

first documented report since 1872. BMC Infect Dis (2013) 13:169. Hum Pathol (2015) 46:1405–7. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2015.05.021

doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-169 18. Medlicott SAC, Adams F. Sarcina ventricularis complicating a patient status

5. Tolentino LF, Kallichanda N, Javier B, Yoshimori R, French SW. A case post vertical banded gastroplasty: a case report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res

report of gastric perforation and peritonitis associated with opportunistic (2015) 14:1481–4. doi:10.17554/j.issn.2224-3992.2015.04.498

infection by Sarcina ventriculi. Lab Med (2003) 34:535–7. doi:10.1309/ 19. Haroon Al Rasheed MR, Kim GJ, Senseng C. A rare case of Sarcina ventriculi

CDFF04HE9FHDQPAN of the stomach in an asymptomatic patient. Int J Surg Pathol (2015) 24(2):

6. Laass MW, Pargac N, Fischer R, Bernhardt H, Knoke M, Henker 142–5. doi:10.1177/1066896915610196

J. Emphysematous gastritis caused by Sarcina ventriculi. Gastrointest Endosc 20. Ferrier D. The constant occurrence of Sarcina ventriculi (Goodsir) in the

(2010) 72:1101–3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.021 blood of man and the lower animals: with remarks on the nature of sarcinous

7. Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, Pai RK, Brown A, Razavi M, et al. vomiting. Br Med J (1872) 1(578):98–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.578.98

Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molec- 21. Gaspar BL. The significance of Sarcina in routine surgical pathology practice.

ular study. Am J Surg Pathol (2011) 35:1700–5. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182 APMIS (2016) 124(6):436–43. doi:10.1111/apm.12526

2911e6 22. Canale-Parola E, Wolfe R. Studies on Sarcina ventriculi. I. Stock culture

8. Sauter JL, Nayar SK, Anders PD, D’Amico M, Butnor KJ, Wilcox RL. method. J Bacteriol (1960) 79:857–9.

Co-existence of Sarcina organisms and Helicobacter pylori gastritis/duodenitis 23. Budding AE, Grasman ME, Lin F, Bogaards JA, Soeltan-Kaersenhout DJ,

in pediatric siblings. J Clin Anat Pathol (JCAP) (2013) 1:103. Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, et al. IS-pro: high-throughput molecular

9. Ratuapli SK, Lam-Himlin DM, Heigh RI. Sarcina ventriculi of the stomach: fingerprinting of the intestinal microbiota. FASEB J (2010) 24(11):4556–64.

a case report. World J Gastroenterol (2013) 19:2282–5. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19. doi:10.1096/fj.10-156190

i14.2282

10. Louis GB, Singh P, Vaiphei K. Sarcina infection. BMJ Case Rep (2014) Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that the research was con-

2014:bcr2013201185. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201185 ducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be

11. Kumar M, Bhagat P, Bal A, Lal S. Co-infection of Sarcina and Giardia in a construed as a potential conflict of interest.

child. Oxf Med Case Reports (2014) 2014:118–9. doi:10.1093/omcr/omu046

12. Karakus E, Kirsaclioglu CT. Coincidence of celiac disease with Sarcina Copyright © 2017 de Meij, van Wijk, Mookhoek and Budding. This is an open-access

infection. Turk J Gastroenterol (2014) 25(Suppl 1):318. doi:10.5152/tjg. article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

2014.8028 (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided

13. Bhagat P, Gupta N, Kumar M, Radotra BD, Sinha SK. A rare association of the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this

Sarcina with gastric adenocarcinoma diagnosed on fine-needle aspiration. journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution

J Cytol (2015) 32:50–2. doi:10.4103/0970-9371.155238 or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Frontiers in Medicine | www.frontiersin.org 5 August 2017 | Volume 4 | Article 145

You might also like

- 1 s2.0 S2352646718301509 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S2352646718301509 MainGilbert MenesesNo ratings yet

- Infectious IleoceicitisDocument2 pagesInfectious IleoceicitisYandiNo ratings yet

- Clinical, Imaging, and Endoscopic Profile of Patients With Abdominal TuberculosisDocument6 pagesClinical, Imaging, and Endoscopic Profile of Patients With Abdominal TuberculosisINDRINo ratings yet

- 299-Article Text-633-1-10-20200912Document5 pages299-Article Text-633-1-10-20200912daily of sinta fuNo ratings yet

- 16 3 2010 0350 0351 PDFDocument2 pages16 3 2010 0350 0351 PDFSandi ApriadiNo ratings yet

- Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults: A Case Series and Literature ReviwDocument6 pagesEosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults: A Case Series and Literature ReviwIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Granulomatous Appendicitis in A 12-Year-Old Boy: Derya Yayla, Bedriye Nuray Alpman, Yasemin DolekDocument3 pagesGranulomatous Appendicitis in A 12-Year-Old Boy: Derya Yayla, Bedriye Nuray Alpman, Yasemin Dolekansar ahmedNo ratings yet

- Pathologic Quiz Case: Residents' PageDocument4 pagesPathologic Quiz Case: Residents' Pagejeka222No ratings yet

- Dealmeida 2020Document3 pagesDealmeida 2020sukhmaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Diagnosis of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Intra Operative Findings and ComparisonDocument7 pages2014 Diagnosis of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) Intra Operative Findings and ComparisonUrología GinecológicaNo ratings yet

- Tuberculous Ileal Perforation in Post-Appendicectomy PeriOperative Period: A Diagnostic ChallengeDocument3 pagesTuberculous Ileal Perforation in Post-Appendicectomy PeriOperative Period: A Diagnostic ChallengeIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- J Epsc 2015 05 012Document4 pagesJ Epsc 2015 05 012Hanung PujanggaNo ratings yet

- Jejunojejunal Intussusception As Initial Presentation of Coeliac Disease: A Case Report and Review of LiteratureDocument6 pagesJejunojejunal Intussusception As Initial Presentation of Coeliac Disease: A Case Report and Review of Literatureellya theresiaNo ratings yet

- 1-3-JMCRCS2024040906 Revised - Galley - Proof - 1715425008Document2 pages1-3-JMCRCS2024040906 Revised - Galley - Proof - 1715425008ILBS M.Sc. NursingNo ratings yet

- Cytomegalovirus-Associated Protein-Losing Gastropathy (Menetrier's Disease) in ChildhoodDocument3 pagesCytomegalovirus-Associated Protein-Losing Gastropathy (Menetrier's Disease) in ChildhoodGilbert MenesesNo ratings yet

- Successful Management of Giant Hydrocolpos in A LiDocument3 pagesSuccessful Management of Giant Hydrocolpos in A LiVictor FernandoNo ratings yet

- Gastroschisis: Case ReportDocument2 pagesGastroschisis: Case ReportMuhammad Syamil RozlanNo ratings yet

- Adult Intussusception A Case ReportDocument4 pagesAdult Intussusception A Case ReportRahmanssNo ratings yet

- Jurnal - Tuba Ovarii Abses - Anisa Ryani MafitriDocument7 pagesJurnal - Tuba Ovarii Abses - Anisa Ryani MafitriBagus Indra KusumaNo ratings yet

- Absceso Hepático NeonatalDocument6 pagesAbsceso Hepático NeonatalNabila Peña ZapataNo ratings yet

- Gastroenteritis Eosinofílica: Aspectos Clínicos e Imagenológicos de Una Entidad Poco Frecuente, Reporte de CasoDocument5 pagesGastroenteritis Eosinofílica: Aspectos Clínicos e Imagenológicos de Una Entidad Poco Frecuente, Reporte de CasoSilvana zeta garciaNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1701216315302577Document4 pagesPi Is 1701216315302577rio rumaropenNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Gastritis, Gastropathy, and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Education GapDocument10 pagesPediatric Gastritis, Gastropathy, and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Education GapvgmanjunathNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Ascites in Children As The Presentation of Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: A Surgeon's PerspectiveDocument6 pagesAbdominal Ascites in Children As The Presentation of Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: A Surgeon's PerspectiveIulia CeveiNo ratings yet

- Dialnet ReporteDeCaso 8584573Document7 pagesDialnet ReporteDeCaso 8584573Astrid VélizNo ratings yet

- Gastritis and Gastropathy Perspectives From The EndoscopistDocument4 pagesGastritis and Gastropathy Perspectives From The Endoscopisthenrique.uouNo ratings yet

- Endoscopia: Diagnostic Approach of Intestinal Tuberculosis: Case and Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesEndoscopia: Diagnostic Approach of Intestinal Tuberculosis: Case and Literature ReviewDumitru RadulescuNo ratings yet

- Acute Gastric Dilatation in ChildrenDocument6 pagesAcute Gastric Dilatation in ChildrenAkbar TabletNo ratings yet

- Calcagno 2018Document10 pagesCalcagno 2018cut normaya putriNo ratings yet

- MRSAcolitisGastroenterol Report2015Document4 pagesMRSAcolitisGastroenterol Report2015selandia nisrinaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Teniasis During A Convencional Gastroplasty: Case ReportDocument3 pagesDiagnosis of Teniasis During A Convencional Gastroplasty: Case ReportHugo Whysk LeonardoNo ratings yet

- Ajg 2009 524Document10 pagesAjg 2009 524Alex Cristian IonutNo ratings yet

- Peptic Ulcer Disease in Chil Den: Gastroenterology Department Mingfang Sun 2020.7.7Document23 pagesPeptic Ulcer Disease in Chil Den: Gastroenterology Department Mingfang Sun 2020.7.7Clifford MartinNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading AnakDocument19 pagesJournal Reading AnakPutra Priambodo WibowoNo ratings yet

- What S Hidden Under The Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Diffuse Type Adenocarcinoma Discovered by Targeted Biopsies A Case ReportDocument4 pagesWhat S Hidden Under The Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Diffuse Type Adenocarcinoma Discovered by Targeted Biopsies A Case ReportHerald Scholarly Open AccessNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guidelines Secondary Prevention of Gastric CancerDocument1 pageClinical Guidelines Secondary Prevention of Gastric Cancerhenrique.uouNo ratings yet

- Verrucous Antral Gastritis in Relation To Helicobacter Pylori Infection, Nutrition, and Gastric AtrophyDocument6 pagesVerrucous Antral Gastritis in Relation To Helicobacter Pylori Infection, Nutrition, and Gastric AtrophySST KNo ratings yet

- Development of Type I Gastric Carcinoid in Patients With Chronic Atrophic GastritisDocument9 pagesDevelopment of Type I Gastric Carcinoid in Patients With Chronic Atrophic GastritisAbristaSeptikasariNo ratings yet

- Case Report Vella NurfatimahDocument4 pagesCase Report Vella NurfatimahVella NurfatimahNo ratings yet

- Medicine: A Newborn Patient With Both Annular Pancreas and Meckel 'S DiverticulumDocument5 pagesMedicine: A Newborn Patient With Both Annular Pancreas and Meckel 'S DiverticulumAdrian UmbriaNo ratings yet

- A Neonatal Septic Arthritis Case Caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae - A Case ReportDocument2 pagesA Neonatal Septic Arthritis Case Caused by Klebsiella Pneumoniae - A Case Reportkartini ciatawiNo ratings yet

- Pamj 12 65Document5 pagesPamj 12 65Iwi DancelNo ratings yet

- Gastritis - Facts and Doubts: Original PaperDocument10 pagesGastritis - Facts and Doubts: Original Paperindah setiyaniNo ratings yet

- Adult Idiopathic Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis A Common Presentation With An Uncommon DiagnosisDocument5 pagesAdult Idiopathic Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis A Common Presentation With An Uncommon DiagnosiszapomannNo ratings yet

- Revista Gastroenterologia Mexico: Scientific LetterDocument4 pagesRevista Gastroenterologia Mexico: Scientific LetterPriyanshu SinghNo ratings yet

- Management of Perforated Appendicitis in Children: A Decade of Aggressive TreatmentDocument5 pagesManagement of Perforated Appendicitis in Children: A Decade of Aggressive Treatmentapi-308365861No ratings yet

- Case Report Proteus Species Infection: A Diagnostic DilemmaDocument5 pagesCase Report Proteus Species Infection: A Diagnostic DilemmaTengku AdriansyahNo ratings yet

- Document 1Document4 pagesDocument 1arditia dwiNo ratings yet

- An Unusual Case of Nonsurgical Pneumoperitoneum in A Pediatric P 2023 BurnsDocument5 pagesAn Unusual Case of Nonsurgical Pneumoperitoneum in A Pediatric P 2023 BurnsAdrian MoralesNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Peritonitis in Patients With Scrub TyphusDocument3 pagesCase Report: Peritonitis in Patients With Scrub TyphusJasleen KaurNo ratings yet

- ургентна хирург тесты англ. 2011Document65 pagesургентна хирург тесты англ. 2011Cynthia GNo ratings yet

- The Rapunzel Syndrome - A Case Report: Trichobezoar As A Cause of Intestinal PerforationDocument4 pagesThe Rapunzel Syndrome - A Case Report: Trichobezoar As A Cause of Intestinal PerforationSajag GuptaNo ratings yet

- Annals of Medicine and SurgeryDocument3 pagesAnnals of Medicine and SurgeryTiti PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Tubular Ileal Duplication Causing Small Bowel Obstruction in A ChildDocument5 pagesTubular Ileal Duplication Causing Small Bowel Obstruction in A ChildDiego Leonardo Herrera OjedaNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Septic AbortionDocument4 pagesCase Study - Septic AbortionHoneylyn100% (1)

- Clostridium DifficileDocument6 pagesClostridium DifficileNutricionista Cinthia Toledo SalazarNo ratings yet

- Mesenteric Cyst Infected With: Salmonella TyphimuriumDocument2 pagesMesenteric Cyst Infected With: Salmonella TyphimuriumAbhishek Soham SatpathyNo ratings yet

- Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical SciencesDocument6 pagesResearch Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical SciencesSurajit SahaNo ratings yet

- Corpus GastritisDocument5 pagesCorpus Gastritisameer143No ratings yet

- Colitis: A Practical Approach to Colon and Ileum Biopsy InterpretationFrom EverandColitis: A Practical Approach to Colon and Ileum Biopsy InterpretationAnne Jouret-MourinNo ratings yet

- Law & Corporate FinanceDocument238 pagesLaw & Corporate FinanceRajesh Shantaram Shinde100% (1)

- Csir TransDocument11 pagesCsir TransRamish KhanNo ratings yet

- DR Niharika Maharshi Sharma ResumeDocument6 pagesDR Niharika Maharshi Sharma ResumeMSSPSNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Experimental Investigation of ConcreteDocument7 pagesA Comparative Experimental Investigation of ConcreteSafwat El RoubyNo ratings yet

- 4 January Personality - Google Search PDFDocument1 page4 January Personality - Google Search PDFNxxr Xleyxh chanelNo ratings yet

- Students' Perceptions of The Twists and Turns of E-Learning in The Midst of The Covid 19 OutbreakDocument12 pagesStudents' Perceptions of The Twists and Turns of E-Learning in The Midst of The Covid 19 OutbreakMajor HariezNo ratings yet

- Amazing Race GuidelinesDocument10 pagesAmazing Race GuidelinesVince Nicole LomocsoNo ratings yet

- Departmental Interpretation and Practice NotesDocument19 pagesDepartmental Interpretation and Practice NotesDifanny KooNo ratings yet

- Architectural Journalism - A View PointDocument2 pagesArchitectural Journalism - A View PointShaurya Chauhan100% (3)

- A Conceited Mistake by Vasko PopaDocument1 pageA Conceited Mistake by Vasko PopaIvana NIkolicNo ratings yet

- Create A Watson Assistant Instance: Lab 1: Creating Watson InstancesDocument7 pagesCreate A Watson Assistant Instance: Lab 1: Creating Watson InstancesErosNo ratings yet

- Richard-2019-9-29 - (PO 1048) PDFDocument1 pageRichard-2019-9-29 - (PO 1048) PDFLeslie Ali TapodocNo ratings yet

- Bagaimana Pendalaman Keuangan Dan Cadangan Devisa Mempengaruhi Stabilitas Nilai Tukar Di NEGARA EMERGING MARKET? (Pendekatan Panel ARDL)Document9 pagesBagaimana Pendalaman Keuangan Dan Cadangan Devisa Mempengaruhi Stabilitas Nilai Tukar Di NEGARA EMERGING MARKET? (Pendekatan Panel ARDL)Yanri DayaNo ratings yet

- Nooyen - Nursery TRIBARDocument1 pageNooyen - Nursery TRIBARRicardo Diaz NiñoNo ratings yet

- CitiesDocument1,468 pagesCitiesAlexandru BizoiNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of RepugnancyDocument13 pagesDoctrine of RepugnancyAmita SinwarNo ratings yet

- AaaDocument45 pagesAaaPriya NairNo ratings yet

- English Essay ExmDocument20 pagesEnglish Essay ExmHassanatulNo ratings yet

- Md. Shahriar Alam: Career ObjectiveDocument4 pagesMd. Shahriar Alam: Career ObjectiveAdnanNo ratings yet

- Hindyati RachmahDocument9 pagesHindyati RachmahhindyatiadtNo ratings yet

- DragonMech - Steam WarriorsDocument127 pagesDragonMech - Steam Warriorsc1768152100% (5)

- April 6, 2020: Laboratory Assignment: TrematodesDocument9 pagesApril 6, 2020: Laboratory Assignment: Trematodesthe someoneNo ratings yet

- Tertullian The African An Anthropological ReadingDocument236 pagesTertullian The African An Anthropological Readingz100% (3)

- WACOM 2017 Org ChartDocument21 pagesWACOM 2017 Org ChartLeonorin FchNo ratings yet

- 10.women LeadershipDocument26 pages10.women LeadershipAbhir Raj ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Seawright Women of Distinction Awards Ceremony BookletDocument28 pagesSeawright Women of Distinction Awards Ceremony BookletrooseveltislanderNo ratings yet

- Constitutional InterpretationDocument13 pagesConstitutional InterpretationAndrew SekayiriNo ratings yet

- Tiểu luận TemplateDocument7 pagesTiểu luận TemplateThảo NguyênNo ratings yet

- What Is Letter?Document4 pagesWhat Is Letter?Angelly V VelascoNo ratings yet

- Inglês 11 Classe (Textos Editores) PDFDocument180 pagesInglês 11 Classe (Textos Editores) PDFNota Joao Tembo50% (2)