Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fasel ObservationsUnamunoKierkegaard 1955

Fasel ObservationsUnamunoKierkegaard 1955

Uploaded by

deigoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fasel ObservationsUnamunoKierkegaard 1955

Fasel ObservationsUnamunoKierkegaard 1955

Uploaded by

deigoCopyright:

Available Formats

Observations on Unamuno and Kierkegaard

Author(s): Oscar A. Fasel

Source: Hispania , Dec., 1955, Vol. 38, No. 4 (Dec., 1955), pp. 443-450

Published by: American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/335323

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese is collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Hispania

This content downloaded from

147.96.128.65 on Thu, 21 Mar 2024 17:36:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

OBSERVATIONS ON UNAMUNO AND KIERKEGAARD

OSCAR A. FASEL

Oklahoma Military Academy

The generally accepted idea that ante todo, porque quiero que Dios exista,

Kierkegaard is one of the great influences y despu6s, porque se me revela, por via

in Unamuno led me to make an earnest cordial, en el Evangelio, y a trav6s de

effort to trace the extent of his influence

Cristo y de la historia."4

in Unamuno's work. I searched for a History is of value to Unamuno par-

reason which would justify Unamuno's

ticularly in tracing the essence of Ca-

calling Kierkegaard his "brother" and that is, of immortality. He pur-

tholicism,

was surprised to discover the deep gap

sues the problem of immortality as it

which separates their concepts ofdeveloped

life, historically in the essay "La

truth, and religion. On all major esencia

issues,del catolicismo," and calls the

on history, art, religion, on the relation-

whole evolution of religious thought to

ship between the individual and society,

his aid. He places the great historic

on such philosophical concepts as personalities,

unity Christ and Saint Paul, and

and nothingness, there exist diametrically

whole epochs such as Hellenism, Judaism,

opposed views. Both approach theseand prob-

the Apostolic Age in the service of

lems as men of faith. In that light histhey

immediate and intimate life with its

are presented here. Though a complete

direct bearing on immortality. In his

picture of their points of view would take

investigation he makes use, among others,

more than can be said in a brief commen-of the following great church historians

tary such as this, the observations madeof his day: Harnack, History of the Dogma;

are quite sufficient to give a fair estimate Weizsi cker, The Apostolic Age of the

of Kierkegaard's limited position in Christian Church; Tr6ltsch, The Social

Unamuno's writings. Teachings of the Christian Churches;

First let us consider their concepts ofRitschl, Justification and Redemption;

history. On May 10, 1900, Unamuno Rohde, Psyche, the Cult of the Soul and

wrote to Clarin: "El ndicleo de mi estudiothe Belief in Immortality among the Greeks;

'La fe' es de obras de teologia luterana, Pfleiderer, The Philosophy of Religion on

de Herrmann, de Harnack, de Ritschl."' a Historic Basis. The endeavor of these

Thus, Unamuno developed his idea of men is summarized by the English trans-

faith according to a theology that does lator of Harnack, Thomas Bailey

not condone "the caprice to overlook all Saunders, in these words: "They rest

that we in religion and Christendom havetheir belief on a calm review of the facts

learned from history."2 "Porque, despuds of history, and their resolution is the

de todo, Jfe cristiana qu6 es? O es la outcome, not of any sectarian prejudice,

confianza en Cristo o no es nada; en la

but of an intelligent desire to promote

persona hist6rica y en la hist6rica reve-

whatever things are wholesome and

laci6n de su vida, t6ngala cada cual como

la tuviera."3 The exemplary image of the true."5 As a result, Unamuno's concept

historic Christ, the Apostolic Age, the of the Christian faith goes beyond mysti-

great historic personalities revealed to cal individualism like Kierkegaard's, be-

Unamuno the spiritual possibilities withinyond his purely subjective approach to

human nature. They motivated his striv-faith, beyond philosophical and theo-

ing to live an independent spiritual and logical speculation, beyond the weight

religious life. "Y si creo en Dios . . . es, of tradition which supports it. The his-

443

This content downloaded from

147.96.128.65 on Thu, 21 Mar 2024 17:36:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

444 HISPANIA

toric point value of view

of religious faith for life.interp

From that

tian faith as time ona he reassures

living us that the historic

thin

To such an historic orientation Kierke- process remains the surest way to arrive

gaard has this to say: "But faith, in the at the revelation of the basis of life and

province of its jurisdiction, raises a still

religion.1?

more essential protest against every at-The arts also demonstrate Unamuno's

tempt to approach Christ by the help and of Kierkegaard's divergent concepts of

what one happens to know of Him reality. On April 15, 1906, Unamuno

wrote to his friend Pedro Jimenez Ilun-

through history and the information his-

tory has preserved about the conse- dain: "Y lo que hago con mas gusto es

quences of His life. Faith's contention isla poesia,""11 and again on January 4,

that this whole attempt is-blasphemy."61907, "Hago versos. Es casi lo finico que

Kierkegaard relied exclusively on his hago desde dentro."12 Poetry, next to

personal religious experiences in mattersreligion, was the stabilizing element, the

of faith, on his "own little I," as he would great moral force in his life with which

say. He did not ask for God's revelations he overcame the limitations and shallow

"a trav6s de Cristo y de la historia." He effects of rational and materialistic exist-

did not ask for concrete and visible signsence. It was the activity through which

of God's existence here on earth, "en la he concretely expressed his religious con-

tierra de los hombres (i.e. in history)."'7sciousness.13 Like religion, it assumed a

In Training in Christianity, the consum-lasting cause-truth. "El arte es la su-

mation of his critical thought, we read: prema verdad, la que se crea en fuerza

"Can one learn from history anything de fe."4 As such it had for him the force

about Christ? No. Why not? Because oneof prayer, of being a "profundo 'Te

can 'know' nothing at all about 'Christ'; Deum' a la madre Naturaleza humani-

He is the paradox, the object of faith, zada."

existing only for faith. But all historical Kierkegaard, after an early enthusiasm

communication is communication of for art, discovered its meaninglessness

'knowledge,' hence from history oneand canbecame violently opposed to all forms

learn nothing about Christ.... History of aesthetic life, which he regarded as

makes out Christ to be another than He "erotic." His passion for purity of faith

truly is, and so one learns to know a lotdrove him to suppress within himself all

about-Christ? No, not about Christ, feeling for artistic values, and to admit

for about Him nothing can be known, He only one alternative: either an aesthetic

can only be believed."8' life or a religious one; either pleasure or

Kierkegaard was driven by an urge tosuffering. Art meant to him indulgence in

live the Christian faith in its purest form,pleasure, and he particularly denounced

detached from all earthly connections asas "a new paganism" efforts to picture

one who "quiere buscar la vida eterna Christ. "Would it be possible for me...

fuera de la historia."' He belonged to the

to dip my brush, to lift my chisel, in order

few who in Harnack's description "hear

to depict Christ ...? I answer, No, it

and understand the voice of God, in the

would be for me an absolute impossibil-

secret of their inner personal life." To be

sure, this personal approach to faith was

ity. . .. It is also inconceivable to me

whence the artist derives his calm . .. with

important to Unamuno. But mere intui-

which he has sat year in year out indus-

tion, feeling, subjective passion were

never strong enough to make him re-triously labouring to paint a portrait of

ligious. Not until he had studied theChrist-without chancing to reflect

historic process of faith at the turn ofwhether Christ desired perhaps to have a

the century was he convinced of theportrait made by his masterbrush ...."]

This content downloaded from

147.96.128.65 on Thu, 21 Mar 2024 17:36:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

UNAMUNO AND KIERKEGAARD 445

Thus Kierkegaard attacked became

Hegel'sa stranger

phi- in the land of promise.

losophy of the fine arts. He left one thing behind, took one thing

with

On the other hand, Unamuno, whohim: he left his worldly wisdom be-

held

hind and took faith

with Hegel that art is an embodiment of with him."'18

the divine, did not consider his This

long type of faith is in the truest sense

poem

a "tension in

El Cristo de Veldzquez an unworthy the void,"19 "la pura nada,"

por-

trait of divinity, a "paganism." Writing

the living of "el puro cristianismo" which

Unamuno

it meant the intensification of tells us terrified Pascal20 and

the reality

of his religious experiences. to be

Itsure

was Unamuno

the himself. "Y he de

symbol in his literary work toconfesar, en efecto, por dolorosa que la

prove that

his religious life took place confesi6n

within sea,theque nunca, en los dias de

reality of human life itself, la fenot ondeami mocedad, me hicieron

ingenua

sphere apart where Kierkegaard temblarplaced

las descripciones, por truculentas

que fuesen,

religious life. It reflects his basic conceptde las torturas del infierno,

y senti experi-

of religion, that purely religious siempre ser la nada mucho mas

ences are insufficient for the whole of aterradora que e1."21 We witness the

human reality-"el total Todo," for they emphatic reversal of past values, notably

ask for absolute independence from the in the function Unamuno gives to re-

phenomenal world, from all cultural and ligion, which denies the reality of noth-

social contacts. The whole of cultural ingness and reveals the depth of human

life-artistic and intellectual, religious nature. He struggles for a richer content

and spiritual-becomes completely im- of life itself, for the dignity of man in an

manent existence in Unamuno's poetry, age in which men like Kierkegaard,

a concrete self-life, a gradual transforma- Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Tolstoi

tion to the heights of immortality, of yielded to depression, in which the anti-

"Ser Dios," as he saw the process re- theological philosophy of HMickel, Biich-

flected in the life of the great poets. "Noner, Virchow, Vogt dealt a deadly blow

se me alcanza por qu6 el Dante, Shake- to Biblical truth. He violently denounces

speare o Cervantes han de ser mas in-their philosophy as an intellectualism

tangibles que uno cualquiera de los santosthat encourages the recognition of life's

que la Iglesia cat61lica ha elevado a susnothingness. He criticizes nothingness

altares."' 1 in Leopardi and Senancour, and calls it

No such affinity between art and re- a "t6trico pesimismo" in one of his

ligion is conceivable to Kierkegaard. He favorite poets, Jose Asunci6n Silva. He

tells us in his Journals that faith alone overlooks Kierkegaard's nihilistic basis

can establish a personal relationship toof faith in his concern with actual living

God, that every other medium is a human reality, "el hombre de carne y hueso, el

attribute to faith and as such affects its que nace, sufre y muere."22 In direct

purity. It is a faith that precludes from defiance of the powerful nineteenth cen-

the very beginning any positive approach tury movement favoring life's nothing-

to man's cultural needs. Purity of faith ness, Unamuno makes life a realm of

is possible only if man leaps into the God: ". . . hemos creado a Dios para

nothing. "Self-annihilation before God" salvar al Universo de la nada."23 Nothing

is "man's truth," "his highest perfection less is at stake than "el reino del hom-

as human being."" Kierkegaard delighted bre"-life itself. He calls every man to

in extremes and submitted only to the completeness, to perfection as Jesus and

reign of the divine, which in his religion Paul defined it. "Porque la religi6n no

is devoid of all hope for humanity, for es anhelo de aniquilarse, sino de totali-

morality and civilization. "By faith, zarse, es anhelo de vida y no de muerte."24

Abraham left the land of his fathers and Opposite Kierkegaard's negative view of

This content downloaded from

147.96.128.65 on Thu, 21 Mar 2024 17:36:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

446 HISPANIA

life stands Unamuno's affirmation: "Y adquieres tu sentido todo, pero despe-

sigo creyendo que si crey6semos todos gado de ella."30 The recognition of society

en nuestra salvaci6n de la nada seriamos as part of human reality puts his idea of

todos mejores."25 individuality in direct opposition to

In no respect does Unamuno's faith Kierkegaard's, for Kierkegaard denies

clash more decisively with Kierkegaard's the value of society. Unamuno seeks a

than in the contact it establishes with solution of the human problem not by

life. Kierkegaard speaks of faith in "via de remoci6n y exclusi6n," but by

absolute terms. Faith to him is a miracle,recognizing the truth in the nineteenth-

a passion, an end in itself. It is a service

century trend toward a definition of

which man renders to God alone. Faith man's place in society and in the uni-

may have been a miracle and a passion verse. He shows a determined will to

to Unamuno; by no means did he con- conquer the urge for a self-life in the

sider it an end in itself, a service only face

to of a new and imposing Weltgeist,

God. "Ni con inventar aquello de la fe cleansed of that "individualismo anar-

en la fe misma se salia del paso. La fe quico" which pushes man toward isola-

necesita una materia en que ejercerse."2 tion and separation. "Y digo los pueblos

The "materia" is man himself and the y no los individuos aislados, porque si

hay sentimiento y concepto colectivo,

world that surrounds him. "Considera

que no hay dentro de Dios mas que social,

tui es el de Dios, aunque el individuo

lo individualice luego."3' The individual

y el mundo."27 Unamuno clearly perceives

-"el hombre de carne y hueso"-no

God as an element of the "Yo" and at

the same time as an element of the

longer remains his own concern. He can-

world, "el mundo." God for him is withdraw

not not into the depth of his "own

little I." He must seek truth in the de-

something beyond the human sphere,

like the traditional or kierkegaardian velopment of a world-enveloping per-

God. Unamuno incorporates God into a sonality. A complete self-life is impossible

world process, a total goal--"el total without humanity and the universe.

Todo." He submits to the demands of Kierkegaard sought true reality in him-

nineteenth-century philosophy andself. Hence he defended monastic life as

theol-

ogy which give life meaning andone value

way to live to the fullest the truth of

after centuries of contempt for this individual existence. "The mystic re-

world. "No busques, pues, derecha e news and revives the last divine image

inmediatamente, fe; busca tu vida, que in man. The more he contemplates, the

si te empapas en tu vida, con ella te more clearly this image is reflected in

entrara la fe."28 Although Unamuno's him."32 Regardless of the fact that Una-

philosophical and theological studies muno consumed himself in his struggle

brought with them much complexity and with the social, political, and religious

difficulty, we cannot fail to recognize the conditions of Spain and the world in

grandeur of their attempt to make life general, he recognized that a culture

purposeful. "Cuil es tu religi6n? Y yo based on separation and total isolation

responder6: mi religi6n es buscar la ver- from the world is a wholly impossible

dad en la vida y la vida en la verdad."29 situation, and he fought the inner urge for

The great new concept in Unamuno's isolation by emphasizing the philosophi-

religion is the place of the world in man's cal concepts of unity, totality, and uni-

own character and nature. In spite of his versality as essential life values. With

these concepts he combats in En torno

intense search after the essence of life

which includes the ultimate, God and al casticismo the separating forces in

Eternity, Unamuno believes that man is traditionalism. In the essay "Adentro,"

bound to other men. "S61o en la sociedad where one would least expect him to

This content downloaded from

147.96.128.65 on Thu, 21 Mar 2024 17:36:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

UNAMUNO AND KIERKEGAARD 447

search for a unifying link standing

between the

of Kierkegaard's separating

individual and the world, he stresses the

individualism, his essays leave no doubt

mutual contact and intermingling be-individual, no matter

that the isolated

tween men, the necessity of howassociation

much he otherwise may represent

of individuals through the the world, remains

promotion of "un atomo," "una

an inward life that reflects the total abstracci6n." "No se trata de cielo y de

truth of human reality-"el yo y el infierno para apuntalar nuestra pobre

mundo." "S61o en la sociedad te encon- moral mundana, ni se trata de nada

traris a ti mismo; si te aislas de ella no

egoista y personal. No soy yo, es el

darns mas que con un fantasma de tu linaje humano todo el que entra en

verdadero sujeto propio."33 Unity and juego; es la finalidad Uiltima de nuestra

continuity of the life process become cultura toda."37 He directs his discus-

essential characteristics of the Man of sions toward the individual, "el hombre

Flesh and Bone in Del sentimiento trd- Kant," "el hombre Spinoza," "el hombre

gico. By their means the inner tension Butler"; yet all have a common destiny

produced by life's contradiction is re-in the human family. All are "hermanos

lieved. "Todo lo que en mi conspireen a humanidad." They presuppose a psy-

romper la unidad y la continuidad de chological

mi unity between the individual

vida, conspira a destruirme ...."34 In- and humanity, a psychological relation-

deed, inward unity and totality are key ship in the totality of human life. "En-

problems with Unamuno. The isolating tr6gate, pues, a los dem.is.... Mi es-

forces in Spanish civilization steadily fuerzo por imponerme a otro, por ser y

reminded him that the individual must vivir yo en 61... es lo que da sentido

not become separated from his universal religioso a la colectividad, a la solidaridad

reality, and he presents us with an ideal,

humana... necesito aduefiarme de la

the Man of Flesh and Bone, the out- sociedad humana; como soy un producto

growth of the revolt of nineteenth-cen- social, tengo que socializarme .. soy yo

tury thought against fragmentation, proyectado al Todo."38

isolation, and separation, against all in- This is intrinsically an ideal of truth

tellectual chipping of the whole truth,and Christianity which completely over-

"la verdad verdadera." shadows Kierkegaard's subjective point

Unamuno tried desperately to recon- of view, the "radically incommunicable

cile his vision of unity between the Iin

and

personal existence." Kierkegaard rid

the world with Kierkegaard's isolatinghimself of all outside interference. He

attitude. " 'Qui6n describi6 la hermosa

denied categorically man's social con-

uni6n de los hombres mas arrebatadora- sciousness as self-deceit. The idea that it

mente que quien se qued6 solitario en lais within the power of the individual to

vida?,' dice Kierkegaard, uno de los masrelieve the tension caused by life's con-

grandes solitarios."'5 Unamuno could not tradiction and to achieve a degree of

wholly free himself of the inner urge forharmony between the opposites, between

a self-life as Kierkegaard represents it.the I and the world, between the tem-

He recognized the dignity and value ofporal and the eternal order of life, is

the great solitary men in history, their unthinkable to him. Not even in the

originality and universality, their "labor

remotest sense can the gulf between the

humana" as the individualization of the opposites be narrowed, least of all closed

eternal and universal content-the hu- as Hegel taught and Unamuno believed.

man spirit. "Los grandes solitarios son, Paradox, contrast, disunity, and contra-

en efecto, los que mis han derramado sus diction make up the content of life for

espiritus entre los hombres; los mis so- Kierkegaard. He condemned Hegel's con-

ciables."36 But in spite of his deep under-

cept of unity and totality as unreal, a

This content downloaded from

147.96.128.65 on Thu, 21 Mar 2024 17:36:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

448 HISPANIA

fallacy of systematic thou

very key to his writings. Brandes' failure

mate victory is "a

to place Kierkegaard's faithroad

in its proper to

Where then does

historic perspective leaves the

the impressionpoi

lie between that Unamuno

Kierkegaard's theology is funda- and

On what can we base Unamuno's deep mentally that of the priest Brand. It

veneration for Kierkegaard? His essays certainly was Unamuno's impression:

reveal that he read only two of Kierke- "... y lo cierto es que en el fondo de la

gaard's works: Concluding Unscientific dramaturgia de Ibsen esta la teologia de

Postscript, to which I counted eight refer- Kierkegaard"44 "... y cuanto dure Brand

ences in Del sentimiento trdgico, and durard Kierkegaard." '4

Either/Or, which he read late in life.39 This is a grave error. Ibsen, who was

Yet his enthusiasm for Kierkegaard well acquainted with Kierkegaard's writ-

dates back to the year 1900. At that time ings, protested the exuberance of the

Unamuno's attention was drawn to Ib- Scandinavian critics who searched among

sen's popularity, and he read Brandes' their nationals for his "model." He was

criticism of Ibsen's work.40 Brandes, particularly annoyed with Brandes' com-

following the "Kierkegaard agitation" parison of his Brand with Kierkegaard.

(Brandes) in the Nordic countries, was "Brand is myself in my best moments,"

eager to bring his countryman Kierke- he declared.46

gaard to the attention of the world, and Ibsen's objection is well founded. His

he compared him to the priest Brand, Brand represents the idea of faith,

the main character in Ibsen's popular initiated in the nineteenth century, which

drama of the same name, making such strives for a synthesis of all life values,

statements as these: "There is in the for a reconciliation of life and faith. "La

priest Brand and in Kierkegaard vida

the y la fe han de fundirse."47 This is a

same sense of isolation.., .the same willwholly unkierkegaardian concept. Kierke-

for self-sacrifice and strength of char- gaard insists that truly religious experi-

acter.. . the same stress on personal ences serve the interests of God alone and

not of human life. He feels that Chris-

sincerity that forces his individualism to

an excess... the same conviction that tianity has become the victim of man's

in every human being there slumbers consciousness of this world, and he em-

the soul of a warrior, an invincible phasizes the opposite as fundamental in

power.., .the same attempt to under- Christianity, namely, the nothingness of

mine the authority of the church... all that is earthly, the idea of self-an-

the same despairing beating of the head nihilation.

against a stone wall."41 These were the Clearly Unamuno's interest could not

first impressions Unamuno had of Kierke-have been in Kierkegaard the thinker

gaard, and they were lasting. but in Kierkegaard the man, the fighter,

Unamuno confirms the effect of the individualist, the non-conformist who

Brandes' presentation of Kierkegaard in the evils of this world, who

fought

a revealing statement in the essay "Ibsen

passionately defied all authority, secular

y Kierkegaard" (1907) where he says: as well as religious. In the truest sense

"Fu6 el critico de Ibsen, Brandes, quien

of the word, this reactionary yet deeply

me llev6 a conocer a Kierkegaard ...."42

religious man was a brother to Unamuno

The implications of this indirect orienta-

in a hostile world that tried to deprive

tion are far-reaching. Unamuno saw him of his own convictions.

Kierkegaard through the eyes of the

critic Brandes, the "atheistic church NOTES

enemy"43 who held but slight interest 1 Unamuno, Epistolario a Clarin (Madrid,

in Kierkegaard's concept of faith, the1941), p. 101.

This content downloaded from

147.96.128.65 on Thu, 21 Mar 2024 17:36:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

UNAMUNO AND KIERKEGAARD 449

2Agnes von Zahn-Harnack, 17 Adolf

David F. Swenson,

von Harnack

Something about Kierke-

(Berlin, 1951), p. 227. gaard (Minneapolis, 1941), p. 87.

8Unamuno, El caballero 18 de Kierkegaard,

la triste Fear and Trembling (London,

figura

(Buenos Aires, 1944), p. 160. 1946), p. 13.

4 Unamuno, Mi religion y otros 19 Guido de Ruggiero, Existentialism

ensayos breves (New

(Buenos Aires, 1945), p. 12. York, 1947), p. 59.

5 Adolf von Harnack, Christianity 10 Unamuno, La agonia,

and p. 86.

History

(London, 1900), p. 9. 21 Unamuno, Del sentimiento trdgico de la vida

6 Soeren Kierkegaard, "The(Buenos Obstacle,"

Aires, 1947),Train-

p. 42.

ing in Christianity (Princeton, 22 Ibid., p. 9. 1944), sec. C.

7 c.... la historia es el pensamiento 23 Ibid., p. 130. de Dios

en la tierra de los hombres." Unamuno, La 24 Ibid., p. 179.

agonia del cristianismo (Buenos Aires, 1942), 25 Ibid., p. 43.

p. 86. 28 Ibid., p. 155.

8 Kierkegaard, op. cit., "The Obstacle," sec. B. 27 Unamuno, El caballero, p. 137.

9 Unamuno, La agonia, p. 86. 28 Ibid., p. 156.

10 Father Quintin P4rez points to the influence 29 Unamuno, Mi religidn, p. 10.

of the theologians who made historic knowledge '3 Unamuno, El caballero, p. 137.

the key to faith. He writes in his book, El 31 Unamuno, Del sentimiento, p. 131.

pensamiento religioso de Unamuno frente al de 32 Kierkegaard, Either/Or, a Fragment of Life

la iglesia (Valladolid, 1946), p. 165: "En la (Princeton, 1944), p. 203. The contemplative,

cuesti6n de Jesucristo no hace mAs que repetir monastic life-"la visi6n beatifica"-is un-

la concepci6n y hasta las frases de Harnack y

realistic to Unamuno. Not in the flight from

los 'Historiadores del dogma,' racionalistas." family and earthly possessions is perfection t

Nemesio Gonzalez Caminero, Professor of be found, but in the common life of mankin

Modern Philosophy at the Universidad Ponti- "La moral monAstica, la puramente momnstic

ficia de Comillas (Santander) says in the first?no es un absurdo? Y llamo aquf moral mon

volume of his work Unamuno (Santander, 1948), tica a la del cartujo solitario, a la del eremit

pp. 116-117: "La mano de Harnack es tan que huye del mundo--llevdndolo acaso consig

visible en toda lucubraci6n hist6rico-eclesiAs- -para vivir solo y a solas con un Dios solo tam

tica de Unamuno, que muchas veces se trata biWn y solitario" (Del sentimiento, pp. 229-230

de una mera traducci6n de las palabras ale- 33 Unamuno, El caballero, p. 137.

manas en castellano. Lo comprueban sus libros 34 Unamuno, Del sentimiento, p. 16.

de ms fondo religioso, como Del sentimientoas Unamuno, Soledad, p. 49.

trdgico de la vida y La agonia del cristianismo,36 Ibid.

y los ensayos mis explicitamente relativos al 37 Unamuno, Del sentimiento, p. 106. Cf. p. 2

problema de la fe, que no son, por otra parte,"El hombre, pues, en su estado de individuo

nms que avances y primeros disefios de las aislado, no ve, ni oye, ni toca, ni gusta, ni huele

mismas ideas expuestas despu6s en esos libros mAs que lo que necesita para vivir y conser-

mayores y en la Vida de Don Quijote y Sancho.varse.... Pero el hombre ni vive solo ni es

En cuestiones como el origen de la fe cristiana individuo aislado, sino que es miembro de

en la resurrecci6n de Jesds, la importancia his- sociedad, encerrando no poca verdad aquel

t6rica del arrianismo, el significado de ciertos dicho de que el individuo, como el dtomo, es

acontecimientos religiosos como el Concilio de una abstracci6n."

Nicea para la evoluci6n de la fe cristiana, y 38 Unamuno, Del sentimiento, p. 224.

otros puntos de vista religiosos, Unamuno los39 In 1932, in the preface to "San Manuel

ha tomado de aquellas lecturas dvidas, aunque Bueno, Mdrtir," Unamuno makes this reveal-

bien trabajosas, que hacia sobre las obras de

Harnack."

ing statement: "Precisamente ahora, cuando

estoy componiendo este pr6logo, he acabado de

1iHern~n Benitez, El drama religioso de

Unamuno (Buenos Aires, 1949), p. 415. leer la obra: 'O lo uno o lo otro' (Enten-Eller)

12 Ibid., p. 416. de mi favorito Soeren Kierkegaard, obra cuya

13 "Esos salmos de mis Poesias, con otraslectura

varias dej4 interrumpida hace unos afios-

composiciones que alli hay, son mi religi6n,antes deymi destierro" (Feb. 1924).

mi religi6n cantada y no expuesta 16gica y 40 Unamuno wrote on April 3, 1900, to Clarin:

razonadamente." Mi religidn, p. 14. "Ahora que traduzco ya el dano-noruego o

14 Unamuno, Vida de Don Quijote y Sancho norso-dands voy a chapuzarme en el te6logo

(Buenos Aires, 1945), p. 190. y pensador Kierkegaard fuente capital de

15 Kierkegaard, op. cit., p. 248. Ibsen, que decia de joven que aspiraba a ser

16 Unamuno, Soledad (Buenos Aires, 1946), p. el poeta de Kierkegaard, segfin he leido en el

53. libro de Brandes sobre Ibsen, que es donde

This content downloaded from

147.96.128.65 on Thu, 21 Mar 2024 17:36:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

450 HISPANIA

empec6 a aprender dan6s

Prophet des Nordens," in Aufsatze zur Litera- (tar

biendo alemin tur- unde ingl6s)"

Geistesgeschichte, Berlin, 1929. (Epis

41 Georg Brandes, 44 Unamuno, Mi religidn, p. 51.

Creative Sp

teenth Century 45 Unamuno, Mi religidn, p. 52. York, 19

(New

B. Anderson. See his essay, "Henrik Ibsen" 46 Ibsen, Brand (New York, 1911), trans. C. H.

(1883). Herford, III, 3.

42 Unamuno, Mi religidn, p. 51. 4 Unamuno introduces the essay "La fe" with

43 Rudolf Unger, "Kierkegaard, der religi6se this quotation from Ibsen's Brand.

This content downloaded from

147.96.128.65 on Thu, 21 Mar 2024 17:36:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Hersh Shefrin (Auth.) - Behavioral Risk Management - Managing The Psychology That Drives Decisions and Influences Operational Risk-Palgrave Macmillan US (2016) PDFDocument520 pagesHersh Shefrin (Auth.) - Behavioral Risk Management - Managing The Psychology That Drives Decisions and Influences Operational Risk-Palgrave Macmillan US (2016) PDFBarbara Lazaro100% (1)

- God Is Dead by Friedrich NietzscheDocument22 pagesGod Is Dead by Friedrich NietzscheAhmad Kliwon100% (3)

- Man and The SupernaturalDocument277 pagesMan and The SupernaturalAudioMonk100% (3)

- At The Hour of Our Death - Mary's Dormition and Christian Dying in Late Patristic and Early Byzantine LiteratureDocument20 pagesAt The Hour of Our Death - Mary's Dormition and Christian Dying in Late Patristic and Early Byzantine LiteratureMelangell Shirley Roe-Stevens SmithNo ratings yet

- Christ Circumcised: A Study in Early Christian History and DifferenceFrom EverandChrist Circumcised: A Study in Early Christian History and DifferenceNo ratings yet

- Risk Acceptability According To The Social SciencesDocument13 pagesRisk Acceptability According To The Social SciencesGonzalo MoyanoNo ratings yet

- Christian Myth and Christian History - Lynn White, Jr.Document14 pagesChristian Myth and Christian History - Lynn White, Jr.TaymiNo ratings yet

- Some Christian ConvictionsA Practical Restatement in Terms of Present-Day Thinking by Coffin, Henry SloaneDocument65 pagesSome Christian ConvictionsA Practical Restatement in Terms of Present-Day Thinking by Coffin, Henry SloaneGutenberg.org100% (1)

- A.D. 381: Heretics, Pagans, and the Dawn of the Monotheistic StateFrom EverandA.D. 381: Heretics, Pagans, and the Dawn of the Monotheistic StateRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Res. of Man-body&SoulDocument14 pagesRes. of Man-body&SoulJodie BarryNo ratings yet

- Some Christian Convictions A Practical Restatement in Terms of Present-Day ThinkingFrom EverandSome Christian Convictions A Practical Restatement in Terms of Present-Day ThinkingNo ratings yet

- Faith and History - A Comparison of Christian and Modern Views of HistoryFrom EverandFaith and History - A Comparison of Christian and Modern Views of HistoryNo ratings yet

- Jesus: Natural SupernaturalDocument4 pagesJesus: Natural SupernaturalR A CoreaNo ratings yet

- The Truth of ChristianityDocument9 pagesThe Truth of ChristianityNONAME69No ratings yet

- Dead Sea ScrollsDocument151 pagesDead Sea ScrollsramNo ratings yet

- Joachim WachDocument300 pagesJoachim Wachwibo wo1No ratings yet

- Leo Tolstoy - The Kingdom of God Is Within YouDocument393 pagesLeo Tolstoy - The Kingdom of God Is Within Youmf636No ratings yet

- Ernest Crawley - The Tree of Life - A Study of ReligionDocument360 pagesErnest Crawley - The Tree of Life - A Study of ReligionExequiel Medina100% (1)

- Christ's Humanity: The Paschal MysteryDocument37 pagesChrist's Humanity: The Paschal Mysteryakimel50% (2)

- Man and Supernatural Mysticism, UnderhillDocument277 pagesMan and Supernatural Mysticism, UnderhillWaterwind100% (1)

- The Templars and the Shroud of Christ: A Priceless Relic in the Dawn of the Christian Era and the Men Who Swore to Protect ItFrom EverandThe Templars and the Shroud of Christ: A Priceless Relic in the Dawn of the Christian Era and the Men Who Swore to Protect ItNo ratings yet

- Conybeare, F. C. - Proclus and The Close of Greek Philosophy - PAS, 1, 2 - 1889-1890!97!110Document15 pagesConybeare, F. C. - Proclus and The Close of Greek Philosophy - PAS, 1, 2 - 1889-1890!97!110the gatheringNo ratings yet

- Religious Quest So 028175 MBPDocument475 pagesReligious Quest So 028175 MBPHanushccka KunNo ratings yet

- Markides, Kyriacos Eastern Orthodox Mysticism & Trans Personal TheoryDocument21 pagesMarkides, Kyriacos Eastern Orthodox Mysticism & Trans Personal TheoryΝικόλαος Μαγαλιός100% (4)

- Jean Danielou - Selected PapersDocument103 pagesJean Danielou - Selected Papers123Kalimero100% (3)

- Cultic Anti-Judaism and Chaucer Litel ClergeonDocument17 pagesCultic Anti-Judaism and Chaucer Litel ClergeonEd ParnovNo ratings yet

- A Short History of the InquisitionFrom EverandA Short History of the InquisitionRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- The Gnosis or Ancient Wisdom in The Christian Scriptures - William KingslandDocument230 pagesThe Gnosis or Ancient Wisdom in The Christian Scriptures - William Kingslandtjramsden100% (2)

- Postmodernism: The Death of God and The Rise of The CommunityDocument17 pagesPostmodernism: The Death of God and The Rise of The CommunityrajeevsonaliNo ratings yet

- Worshiping, Witnessing, and Wondering: Christian Wisdom for Participation in the Mission of GodFrom EverandWorshiping, Witnessing, and Wondering: Christian Wisdom for Participation in the Mission of GodNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press Harvard Divinity SchoolDocument20 pagesCambridge University Press Harvard Divinity Schoolcri28100% (1)

- New Light from the Great Pyramid: The Astronomico-Geographical System of the Ancients RecoveredFrom EverandNew Light from the Great Pyramid: The Astronomico-Geographical System of the Ancients RecoveredNo ratings yet

- Harnack - What Is ChristianityDocument195 pagesHarnack - What Is ChristianityemanuelwildNo ratings yet

- Theology and History An Outline of MethodologicalDocument15 pagesTheology and History An Outline of MethodologicalPeter WitbooiNo ratings yet

- Towards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture: Grounding Our Identity in ChristFrom EverandTowards an Incarnational Spiritual Culture: Grounding Our Identity in ChristNo ratings yet

- Eastern Orthodox Mysticism and Transpersonal Theory PDFDocument21 pagesEastern Orthodox Mysticism and Transpersonal Theory PDFjcbazinetNo ratings yet

- Becoming Muslim, Nuh Ha Mim KellerDocument7 pagesBecoming Muslim, Nuh Ha Mim KellerAneesa MemonNo ratings yet

- The Christian Identity in A Corrupt Society in The Light of 1 Peter 2 and Its Challenge To The Contemporary ChristianDocument9 pagesThe Christian Identity in A Corrupt Society in The Light of 1 Peter 2 and Its Challenge To The Contemporary ChristianGodswill M. O. UfereNo ratings yet

- Ayesha Iftikhar-1617139 EnlDocument5 pagesAyesha Iftikhar-1617139 EnlMuhammad AayanNo ratings yet

- Crawley Tree of LifeDocument101 pagesCrawley Tree of Lifeszaman10No ratings yet

- Michael Azkoul St. Gregory of Nyssa and The Tradition of The FathersDocument122 pagesMichael Azkoul St. Gregory of Nyssa and The Tradition of The FathersFabian GraculusNo ratings yet

- Journal of Biblical and Pneumatological Research: Volume One, 2009From EverandJournal of Biblical and Pneumatological Research: Volume One, 2009No ratings yet

- Brown Conversion and Christianization in Late Antiquity 2004 PDFDocument18 pagesBrown Conversion and Christianization in Late Antiquity 2004 PDFnimportequoi38No ratings yet

- Golgotha Jerusalem and Athens Patristic12Document33 pagesGolgotha Jerusalem and Athens Patristic12Marios AshikkisNo ratings yet

- 1995 - Howard Clark Kee - A Century of Quests For The Culturally Compatible JesusDocument13 pages1995 - Howard Clark Kee - A Century of Quests For The Culturally Compatible Jesusbuster301168No ratings yet

- Inescapablechris 0000 BowiDocument222 pagesInescapablechris 0000 BowialexNo ratings yet

- Jesus Christ and History by George E. Ladd 1963Document38 pagesJesus Christ and History by George E. Ladd 1963Tiago Silva100% (3)

- Contemporary Christianity As A New ReligionDocument14 pagesContemporary Christianity As A New ReligionJodie Barry100% (1)

- The Mystery and the World: Passion for God in Times of UnbeliefFrom EverandThe Mystery and the World: Passion for God in Times of UnbeliefNo ratings yet

- Inner Christianity: A Guide To The Esoteric TraditionDocument2 pagesInner Christianity: A Guide To The Esoteric TraditionyogimanmanNo ratings yet

- Job Interview Questions For Financial AnalystsDocument5 pagesJob Interview Questions For Financial AnalystsPabitha MonishaNo ratings yet

- Stronghold of Jante Curse-Breaking Prayers DWJD-team SFC-int PDFDocument5 pagesStronghold of Jante Curse-Breaking Prayers DWJD-team SFC-int PDFturbitolocoNo ratings yet

- (NLP - Document) Power Attitudes and AffirmationDocument3 pages(NLP - Document) Power Attitudes and AffirmationAncaGheraseNo ratings yet

- Hamza ReportDocument29 pagesHamza ReportPrince MjNo ratings yet

- AzeemiyaDocument17 pagesAzeemiyaMusafirus Siir100% (1)

- Training Development - IndianOilDocument75 pagesTraining Development - IndianOilAbsarul Haque100% (1)

- Clustering Large Data Sets With Mixed Numeric and Categorical ValuesDocument14 pagesClustering Large Data Sets With Mixed Numeric and Categorical ValuesNurlita Kusuma DewiNo ratings yet

- (Ivan Lowe) A First Textbook of Research MethodoloDocument401 pages(Ivan Lowe) A First Textbook of Research Methodoloksreddy2002No ratings yet

- Job DesignDocument7 pagesJob DesignBeezy BeeNo ratings yet

- Sample Narrative Essay - 30th April 2023Document2 pagesSample Narrative Essay - 30th April 2023Dale QuadrosNo ratings yet

- Berklee Summer Program EssayDocument2 pagesBerklee Summer Program EssaySantiago Cuadra100% (1)

- Indianness in Nissim EzekielDocument3 pagesIndianness in Nissim EzekielAniket BobdeNo ratings yet

- S Problem Set 4: 1 Young & Friedman 5 26Document5 pagesS Problem Set 4: 1 Young & Friedman 5 26Jake AJNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Cell RegenerationDocument10 pagesIntroduction To Cell Regenerationlalithapoyya92% (13)

- Locke BigDocument266 pagesLocke BigHelena BrownNo ratings yet

- Week 2-Chapter 1 - Philosophical Thoughts On EducationDocument6 pagesWeek 2-Chapter 1 - Philosophical Thoughts On EducationJuan Miguel Sapad AlpañoNo ratings yet

- Eudonia and HappinessDocument49 pagesEudonia and HappinessFurkan AydinerNo ratings yet

- The Clave MatrixDocument11 pagesThe Clave MatrixKhadija-taj O'connor-Parris100% (2)

- Sta Se To Tebe SmatraDocument83 pagesSta Se To Tebe SmatraMilica PavlovicNo ratings yet

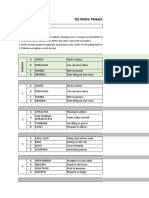

- Tes Profil Pribadi - Definisi Kata: NamaDocument8 pagesTes Profil Pribadi - Definisi Kata: Namareadme345No ratings yet

- Channeling Your Higher SelfDocument25 pagesChanneling Your Higher SelfStan Bogdan100% (1)

- Organizational BehaviorDocument19 pagesOrganizational BehaviorfadeellaNo ratings yet

- Reader ResponseDocument7 pagesReader ResponseArmand NarcellesNo ratings yet

- First Film Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesFirst Film Lesson Planapi-273740325No ratings yet

- (Article) The Development of Peirce's Philosophy by Murray G. MurpheyDocument7 pages(Article) The Development of Peirce's Philosophy by Murray G. MurpheydositheeNo ratings yet

- Firth, R. Austin and The Argument From Illusion PDFDocument12 pagesFirth, R. Austin and The Argument From Illusion PDFgabrielaberchtNo ratings yet

- Tone - 8 - Plagal 4 - 10 June 2012 - 1 AP - 1 Matt - All SaintsDocument8 pagesTone - 8 - Plagal 4 - 10 June 2012 - 1 AP - 1 Matt - All SaintsMarguerite PaizisNo ratings yet