Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anti-Natalism Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Anti-Natalism Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Uploaded by

thongwj-wa12Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Eddy Current (RFT) ProcedureDocument12 pagesEddy Current (RFT) ProcedureAnonymous gFcnQ4go83% (6)

- Still Better Never To Have Been: A Reply To (More Of) My Critics - David BenatarDocument31 pagesStill Better Never To Have Been: A Reply To (More Of) My Critics - David BenatarAnonymous oyXvKN4OK100% (3)

- Alco Century 628'sDocument5 pagesAlco Century 628'sstaustell92100% (1)

- Torts OutlineDocument69 pagesTorts Outlinecflash94No ratings yet

- Bengkalis Muria - Jurnal Khusus - Hanifah Hilyah SyahDocument9 pagesBengkalis Muria - Jurnal Khusus - Hanifah Hilyah Syahreza hariansyahNo ratings yet

- Nursing Health AssessmentDocument6 pagesNursing Health Assessmentramonlu05100% (1)

- Fallacies of Relevance: Appeal To ForceDocument6 pagesFallacies of Relevance: Appeal To ForceTomato MenudoNo ratings yet

- Methods of PhilosophizingDocument4 pagesMethods of Philosophizingmichelle manliguezNo ratings yet

- Debating Procreation (With David Benatar)Document2 pagesDebating Procreation (With David Benatar)Mauricio RíosNo ratings yet

- TRENDS Reviewer - CompleteDocument5 pagesTRENDS Reviewer - Completejhna mggyNo ratings yet

- PHILOSOPHYDocument5 pagesPHILOSOPHYSyntheria YashikaNo ratings yet

- Ignorance Is Not BlissDocument5 pagesIgnorance Is Not BlissSelinaNo ratings yet

- (John Duns Scotus) - Ordinatio III dd.1-17Document280 pages(John Duns Scotus) - Ordinatio III dd.1-17Khegan Delport100% (1)

- Part TwoDocument74 pagesPart Twoирина черкашинаNo ratings yet

- Pointers Human BehaviorDocument3 pagesPointers Human BehaviorElizabeth April GalveNo ratings yet

- Argumentum Ad Baculum)Document8 pagesArgumentum Ad Baculum)JESSAMINE ANN DEGALANo ratings yet

- Evil Inside Human Violence and CrueltyDocument3 pagesEvil Inside Human Violence and CrueltyNino BasilaiaNo ratings yet

- Bowman Torts OutlineDocument46 pagesBowman Torts OutlineLauren JanuzziNo ratings yet

- Fallacies 093440Document16 pagesFallacies 093440barcenaljeremyNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Arguments and FallaciesDocument3 pagesModule 5 Arguments and FallaciesNiger RomeNo ratings yet

- Fallacies Activity and WorksheetDocument2 pagesFallacies Activity and WorksheetYumi NabanaNo ratings yet

- Fallacies Common Mistakes in Thinking: Submitted By: Christian John CunananDocument16 pagesFallacies Common Mistakes in Thinking: Submitted By: Christian John Cunanancj cunananNo ratings yet

- Philosophy ReportDocument29 pagesPhilosophy ReportEZ.JETH. BERGSTROMNo ratings yet

- Emilio Aguinaldo College: Midterm ExamDocument10 pagesEmilio Aguinaldo College: Midterm ExamEldonVinceIsidroNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic PhilDocument2 pagesDiagnostic PhilAra Russel BathanNo ratings yet

- Safety, Identity and Consent: A Limited Defense of Reproductive Human CloningDocument12 pagesSafety, Identity and Consent: A Limited Defense of Reproductive Human CloningMatt BruhnNo ratings yet

- PhilosophyDocument2 pagesPhilosophyHannah AgravanteNo ratings yet

- Logical Fallacies PracticeDocument2 pagesLogical Fallacies PracticeMelissa Jo AlbrechtNo ratings yet

- Gender and Society NotesDocument24 pagesGender and Society NotesBarb Bluebumblebee88% (16)

- ActivityDocument2 pagesActivityd.laraNo ratings yet

- CasebuildDocument5 pagesCasebuildSantiagoNo ratings yet

- Human IndignityDocument168 pagesHuman IndignityRay CoilNo ratings yet

- Logic NotesDocument2 pagesLogic NotesMad DummyNo ratings yet

- Intentional Torts Cheat Sheet: by ViaDocument1 pageIntentional Torts Cheat Sheet: by ViadelibsuzcezNo ratings yet

- Online Examination For Argumentation and DebateDocument2 pagesOnline Examination For Argumentation and Debatejetlee estacionNo ratings yet

- Notes On Aquinas and PoliticsDocument19 pagesNotes On Aquinas and PoliticsJared WuerzburgerNo ratings yet

- Torts Outline 4th Edition (2nd One)Document24 pagesTorts Outline 4th Edition (2nd One)michael bradfordNo ratings yet

- MAP Vocab Quiz 1Document1 pageMAP Vocab Quiz 1Daniela Hernandez MagroNo ratings yet

- MIEVILLE - Theses On MonstersDocument4 pagesMIEVILLE - Theses On Monsterscubanosantiaguero100% (1)

- Instructor Manual For Corrections The Essentials 2nd Second Edition Mary K Stohr Anthony WalshDocument24 pagesInstructor Manual For Corrections The Essentials 2nd Second Edition Mary K Stohr Anthony WalshKimberlyBennettcipym100% (27)

- The Ethics of Preventive War - (Part I Conceptual, Normative, and Methodological Terrains)Document17 pagesThe Ethics of Preventive War - (Part I Conceptual, Normative, and Methodological Terrains)Alastair HughesNo ratings yet

- Common Principled ArgumentsDocument4 pagesCommon Principled Arguments9tcydfhfqbNo ratings yet

- Torts QuicksheetDocument5 pagesTorts QuicksheetDisha PatelNo ratings yet

- 21st Literature Week 15 (Short Quiz)Document2 pages21st Literature Week 15 (Short Quiz)Jasmine MendozaNo ratings yet

- Richard Swinburne - Natural EvilDocument8 pagesRichard Swinburne - Natural EvilJack BlackNo ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument35 pagesReviewergianmarlo.sungaNo ratings yet

- Avoid Fallacies-A Worksheet and HandoutDocument3 pagesAvoid Fallacies-A Worksheet and Handoutrehan bagusNo ratings yet

- MTLB Final Quiz CompiledDocument7 pagesMTLB Final Quiz CompiledOwkay HNo ratings yet

- CLASS X - English - Themes Chapter WiseDocument3 pagesCLASS X - English - Themes Chapter Wisecyrilgilbertson88% (8)

- Philo - Set CDocument2 pagesPhilo - Set CNoel abarcaNo ratings yet

- Planning ArgumentDocument2 pagesPlanning ArgumentRTW SebasNo ratings yet

- Instructions: A. Write The Letter of The Best Possible Answer in The AnswerDocument4 pagesInstructions: A. Write The Letter of The Best Possible Answer in The AnswerMariaJorjiyPonceNo ratings yet

- Yes, The Baby Should Live - A Pro-Choice Response To Giubilini and MinervaDocument7 pagesYes, The Baby Should Live - A Pro-Choice Response To Giubilini and MinervaSea AnglerNo ratings yet

- Glashausser Fall 2016 Torts Barranco OutlineDocument39 pagesGlashausser Fall 2016 Torts Barranco OutlineLizzy McEntireNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Outline (2018 Edits)Document35 pagesCriminal Law Outline (2018 Edits)Keith Pridgen100% (2)

- Prelim Lesson 3 ElearningDocument6 pagesPrelim Lesson 3 ElearningSophia Katrina FactoraNo ratings yet

- FALLACIESDocument9 pagesFALLACIESAbegail FloresNo ratings yet

- Criminology ReviewerDocument18 pagesCriminology ReviewerAngela TecsonNo ratings yet

- Fleming - S Torts I Outline PDFDocument30 pagesFleming - S Torts I Outline PDFno contract100% (3)

- Dispute Resolution and Crises Management QA 1Document9 pagesDispute Resolution and Crises Management QA 1Mandanas GabrielNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Philosophy 12: Department of Education Maryknoll High School of AsuncionDocument2 pagesIntroduction To Philosophy 12: Department of Education Maryknoll High School of AsuncionMary-Rose CasuyonNo ratings yet

- Sperm Competition and the Evolution of Animal Mating systemsFrom EverandSperm Competition and the Evolution of Animal Mating systemsNo ratings yet

- En GB-car Exchange AgreementDocument2 pagesEn GB-car Exchange Agreementbaby_charm100% (1)

- FirmwareUpgradeInstructionsRx3iCPEs v1Document4 pagesFirmwareUpgradeInstructionsRx3iCPEs v1Wilson KnuppNo ratings yet

- Waste Heat Conversion in Compression Ignition Engine To The Electric Power by Using Exhaust Heat Recovery System Contained TEGDocument5 pagesWaste Heat Conversion in Compression Ignition Engine To The Electric Power by Using Exhaust Heat Recovery System Contained TEGJohnny M. Pancha RamosNo ratings yet

- Superior & Inferior Mesenteric Arteries Portal Vein & Its TributariesDocument19 pagesSuperior & Inferior Mesenteric Arteries Portal Vein & Its TributariesHevin GokulNo ratings yet

- Lesson1.2 Day3 Clean and Sanitize Kitchen PremisesDocument16 pagesLesson1.2 Day3 Clean and Sanitize Kitchen PremisesAliyah PlaceNo ratings yet

- Shipping Out of Sleepers FAT-TK-011-CHKDocument4 pagesShipping Out of Sleepers FAT-TK-011-CHKThai Hai LyNo ratings yet

- Electrical Workshop: 1) Safety ClothesDocument12 pagesElectrical Workshop: 1) Safety Clothessohail arshadNo ratings yet

- IPD Patient History ChecklistDocument2 pagesIPD Patient History ChecklistdrjriNo ratings yet

- Bohren Et Al Lancet MH Series 4 2023Document12 pagesBohren Et Al Lancet MH Series 4 2023Thierry UhawenimanaNo ratings yet

- Post Traumatic Stress Reactions in Children of War: Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry March 1999Document8 pagesPost Traumatic Stress Reactions in Children of War: Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry March 1999yuliaNo ratings yet

- Importance of Psychology in Nursing PracticeDocument6 pagesImportance of Psychology in Nursing PracticeNan Nda Pradipta67% (3)

- Do Dont - Does DoesntDocument2 pagesDo Dont - Does Doesntdeathnote lNo ratings yet

- Resilience During CovidDocument41 pagesResilience During CovidGiorgosNo ratings yet

- Biology CH 7 Practice TestDocument6 pagesBiology CH 7 Practice Testvaleria100% (2)

- Controversy About Mabini's Paralysis: ShrinesDocument2 pagesControversy About Mabini's Paralysis: ShrinesDarry BlanciaNo ratings yet

- History of Myplate PresentationDocument23 pagesHistory of Myplate Presentationapi-547212356No ratings yet

- Banks On Second-Endorsed Checks Accept or Not?Document3 pagesBanks On Second-Endorsed Checks Accept or Not?Vanessa May GaNo ratings yet

- 5.1 The Structure of Plasma Membranes Student NotesDocument24 pages5.1 The Structure of Plasma Membranes Student NotesLisa MillardNo ratings yet

- Microfinance For Sanitation. Indonesia Water Supply and Sanitation Magazine PERCIK July 2005.Document60 pagesMicrofinance For Sanitation. Indonesia Water Supply and Sanitation Magazine PERCIK July 2005.Oswar MungkasaNo ratings yet

- KEMELIX 3504X-LQ - (RB) : Safety Data SheetDocument9 pagesKEMELIX 3504X-LQ - (RB) : Safety Data SheetLuigi NicoraNo ratings yet

- Vistamore SDN BHD Project Quality Plan Section 1Document8 pagesVistamore SDN BHD Project Quality Plan Section 1Wan Mohamad Noor Hj IsmailNo ratings yet

- Factors That Affect Time Management of Humanities and Social Sciences Grade 11 Senior High School StudentsDocument8 pagesFactors That Affect Time Management of Humanities and Social Sciences Grade 11 Senior High School StudentsCamile IgnacioNo ratings yet

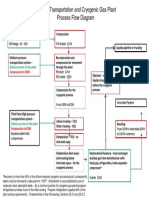

- Generic Transportation and Cryogenic Gas Plant Process Flow DiagramDocument1 pageGeneric Transportation and Cryogenic Gas Plant Process Flow DiagramSyahmi AbdullahNo ratings yet

- ScalpDocument17 pagesScalpKaruna PrabhuNo ratings yet

- 12 Chapter2Document48 pages12 Chapter2Arinta Purwi Suharti100% (1)

- Decon Technologies Information PackDocument22 pagesDecon Technologies Information PacksoldatosnNo ratings yet

Anti-Natalism Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Anti-Natalism Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Uploaded by

thongwj-wa12Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anti-Natalism Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Anti-Natalism Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Uploaded by

thongwj-wa12Copyright:

Available Formats

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.

edu/anti-natalism/

b. Challenges to the Asymmetry Argument

c. The Deluded Gladness Argument

d. Challenges to Deluded Gladness

e. Overall’s Sexism Challenge to Benatar

f. The Hypothetical Consent Argument

g. Challenges to Hypothetical Consent

h. The No Victim Argument

Anti-Natalism i. The Exploitation Argument

j. Negative Utilitarianism

Anti-natalism is the extremely provocative view that it is either always or usually impermissi-

k. Broader Implications

ble to procreate. Some find the view so offensive that they do not think it should be dis-

2. Additional Objections to Philanthropic Arguments

cussed. Others think their strongly intuitive disagreement with it is enough in itself to reject

a. Procreative Autonomy

all arguments for anti-natalism. In the first twenty years of the twenty-first century, however,

b. Pro-Mortalism

a distinct literature emerged that addressed anti-natalism. Sophisticated arguments both in

3. The Misanthropic Argument

favour of and against anti-natalism have been developed and defended. Philanthropic argu-

a. Premise 2 of the Misanthropic Argument

ments for anti-natalism, that is, arguments that emphasize liking and trusting human beings

i. Harm to Humans

(as opposed to misanthropic arguments), focus on the harm done to individuals who are

ii. Harm to Animals

brought into existence. For example, David Benatar’s Asymmetry Argument says that it is

iii. Harm to the Environment

wrong to procreate because of an asymmetry between pleasure and pain. The absence of pain

b. Premise 1 of the Misanthropic Argument

is good even if no one experiences that good whereas the absence of pleasure is not bad un-

c. The Presumptive Duty Not to Procreate

less someone is deprived of it. Since everyone who comes into existence will inevitably expe-

4. Anti-Natalism and Duties to the Poor

rience nontrivial harm, it is better that they are not brought into existence since no one

5. Future Directions

would be harmed by their non-existence. Other philanthropic arguments include the idea

a. Religious Perspectives on Anti-Natalism

that individuals cannot consent to their creation, that procreating necessarily involves creat-

b. Anti-Natalism and Non-Western Ethics

ing victims, and that procreation involves exploiting babies in order to get fully formed

c. Anti-Natalism and Population Ethics

adults. Misanthropic arguments for anti-natalism, on the other hand, appeal to the harm that

d. Human Extinction as the Goal of Anti-Natalism

individuals who are brought into existence will cause. These include the harms that humans

6. References and Further Reading

inflict upon each other, other animals, and the environment. Finally, it has also been recog-

nized that if we have a duty to relieve extreme poverty when possible, there may be a corre-

sponding duty for both the rich and poor to cease from procreating. 1. Philanthropic Arguments for Anti-Natalism

This section outlines important philanthropic arguments for anti-natalism, which focus on

There are numerous ways to expand the debate about anti-natalism. For instance, scholars of

the harm done to individuals who are created. Philanthropic arguments are particularly con-

religion have had little to say about anti-natalism, but it is unclear that they can completely

troversial because they tend to conclude that it is always all-things-considered impermissi-

dismiss certain of these arguments out of hand. Additionally, the debate about anti-natalism

ble to procreate. The specific arguments outlined in this article include the Asymmetry

has primarily been conducted within the context of Western philosophy. It is an open ques-

Argument, the Deluded Gladness Argument, the Hypothetical Consent Argument, the No

tion how the arguments for anti-natalism would be evaluated by various non-Western ethical

Victim Argument, and the Exploitation Argument. This section concludes by briefly examin-

theories. Finally, environmental ethics and population ethics have had little to say about anti-

ing the broader implications of philanthropic arguments.

natalism, and as such there are many avenues for further exploration.

a. Benatar’s Asymmetry Argument

Table of Contents

The South African philosopher David Benatar is probably the most influential contemporary

1. Philanthropic Arguments for Anti-Natalism

proponent of anti-natalism, although later we will see that he has offered a misanthropic ar-

a. Benatar’s Asymmetry Argument

1 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM2 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

gument for anti-natalism, he is best known for defending a strong philanthropic argument (2) the presence of pleasure is good (Benatar 2006, 30).

which says that it is always impermissible to procreate.

However, Benatar claims that this sort of symmetry does not exist when applied to the ab-

Benatar’s main defense of philanthropic arguments is to be found in his book, Better Never sence of pain:

to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence (2006). Since its publication, he has de-

fended the main lines of argument in this book from various critiques and appears not to (3) the absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone,

have wavered from his initial conclusions. Benatar explains that “[t]he central idea of [his]

book is that coming into existence is always a serious harm” (2006, 1; emphasis added). He whereas

is well aware that the strong evolutionary tendency towards optimism means that many will

find such a conclusion repulsive. Finally, while Benatar focuses most of his discussion on hu- (4) the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is somebody for whom this absence

man procreation, he is clear from the beginning that his argument applies to all sentient be- is a deprivation (Benatar 2006, 30).

ings because they are capable of experiencing harm (2006, 2).

One reason for holding the asymmetry between (3) and (4) is that it enjoys great explanatory

How does Benatar arrive at such a controversial conclusion? Consider that many people hold power. According to Benatar, it explains four different asymmetries better than competing al-

that procreation is often permissible because most individuals who come into existence be- ternatives. The first asymmetry it explains is also probably the most obvious one. This is the

lieve that their lives are worth living. In other words, many of us think our lives are worth liv- asymmetry between the claim that we have a strong duty not to intentionally bring someone

ing despite facing a certain number of obstacles and difficulties throughout our lives. into existence who will suffer, but we do not have a corresponding duty to bring happy per-

Moreover, a problem about personal identity raised by twentieth-century moral philosopher sons into existence (Benatar 2006, 32). The second asymmetry is between the strangeness of

Derek Parfit complicates matters further. This problem is called the non-identity problem citing the benefit to a potential child as the reason for bringing them into existence versus the

and raises questions about whether it is even possible for an individual with an extremely low coherence of citing the harms to a potential child as the reason for not bringing them into ex-

quality of life to coherently wish that their life had gone differently (1996). For example, if istence (Benatar 2006, 34). The third asymmetry involves our retrospective judgments.

Sally was born to different parents or in different circumstances, it is doubtful that Sally While we can regret both bringing an individual into existence and not bringing an individual

would really be the same person at all, and not some other different person, Sally*. Benatar into existence, it is only possible to regret bringing an individual into existence for the sake of

argues that all of this is the result of a simple mistake. He suggests that the non-identity that individual. If that individual had not been brought into existence, they would not exist

problem only arises because people frequently conflate a life worth continuing with a life and hence nothing could be regretted for their sake (Benatar 2006, 34). The fourth asymme-

worth starting. According to Benatar, these are hardly the same. This is because the former try is between our judgments about distant suffering versus uninhabited regions. We should

judgment is one that a person who already exists makes about themselves, while the latter rightly be sad and regret the former, but we should not be sad or regret that some far away

judgment is one about a potential though non-existent being (Benatar 2006, 19-23). planet (or island in our own world), is uninhabited (Benatar 2006, 35).

Benatar’s thesis is that no lives are worth starting, even though many lives are worth continu-

ing once they have been started. Here is a chart Benatar uses to further explain his view (Benatar 2006, 38):

One of the main ways that Benatar defends this view is by appealing to important asymme- If X exists If X never exists

tries between non-existence and existence. For Benatar, “there is a crucial difference between

Presence of pain (Bad) Absence of pain (Good)

harms (such as pains) and benefits (such as pleasures) which entails that existence has no

advantage over, but does have disadvantages relative to, non-existence” (Benatar 2006, 30). Presence of pleasure (Good) Absence of pleasure (Not bad)

Here is a key distinction that Benatar needs to establish the Asymmetry Argument: the ab-

sence of pain is good even if no one experiences that good while the absence of pleasure is not Thus, the absence of pain is good even if the best or perhaps only way to achieve it is by the

bad unless someone is deprived of it. Consider: very absence of the person who would otherwise experience it. This asymmetry between

harm and pleasure explains why it is wrong to have a child because they will not benefit from

(1) the presence of pain is bad, that existence, while “it is not strange to cite a potential child’s interests as a basis for avoid-

ing bringing a child into existence” (Benatar 2005, 34). With this asymmetry established,

and that Benatar concludes that coming into existence in our world is always a harm. In sum, “[t]he

3 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM4 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

fact that one enjoys one’s life does not make one’s existence better than non-existence, be- Elizabeth Harman claims that Benatar’s Asymmetry Argument “equivocates between imper-

cause if one had not come into existence there would have been nobody to have missed the sonal goodness and goodness for a person” (2009, 780). It is true that the presence of pain is

joy of leading that life and thus the absence of joy would not be bad” (Benatar 2005, 58). bad. It is both personally and impersonally bad. However, the absence of pain is only imper-

sonally good since there is no person who exists to experience its absence (Harman 2009,

780). But for the asymmetry to hold Benatar would have to show that absence of pain is also

b. Challenges to the Asymmetry Argument personally good. All of the various rejoinders to these claims cannot be discussed, but it is

Benatar’s Asymmetry Argument has been challenged in a number of places. Some have sug- noteworthy that Benatar has directly responded to many criticisms of his arguments (for ex-

gested that the distinction between a life worth starting and a life worth continuing does not ample, Benatar 2013).

hold up to scrutiny (DeGrazia 2012; Metz 2011, 241). Why think these are two distinct stan-

dards? For example, why not hold that a life worth starting just is a life that will be worth

continuing? Some have argued that Benatar does not do enough to defend this distinction,

c. The Deluded Gladness Argument

which is an important one for the success of his argument. Another objection has been to Benatar also offers a second argument in support of his anti-natalist conclusion, which can

challenge directly the asymmetries defended by Benatar. While Benatar suggests that an ab- be called the Deluded Gladness Argument. The main thrust of this argument is to show that

sence of pleasure is not bad unless there is an individual who is deprived of it, perhaps it is while typical life assessments are often quite positive, they are almost always mistaken. This

better understood as not good (Metz 2011, 242). Likewise, maybe an absence of pain is better serves as a standalone argument for the claim that we should refrain from procreating since

understood as not bad (Metz 2011, 242-243). This would modify Benatar’s chart to the fol- all (or almost all) lives are quite bad. It also offers support for the Asymmetry Argument

lowing: which says that if an individual’s life will contain even the slightest harm, it is impermissible

to bring them into existence. This argument aims to show that in the vast majority of cases,

If X exists If X never exists the harms contained in human lives are far from slight. Benatar argues that “even the best

lives are very bad, and therefore that being brought into existence is always a considerable

Presence of pain (Bad) Absence of pain (Not Bad)

harm” (2006, 61).

Presence of pleasure (Good) Absence of pleasure (Not Good)

Most people’s own self-assessments of their lives are positive. In other words, most people

There are at least two reasons to favour this symmetry to the asymmetry posited by Benatar. are glad to have been brought into existence and do not think they were seriously harmed by

First “is the fact of symmetry itself. As many physicists, mathematicians and philosophers of being brought into existence. The ‘Deluded Gladness Argument’ is Benatar’s reasons for

science have pointed out, symmetrical principles and explanations are to be preferred, ceteris thinking that such self-assessments are almost always the result of delusion. Benatar explains

paribus, to asymmetrical ones” (Metz 2011, 245). Second, the symmetry may better explain that “[t]here are a number of well-known features of human psychology that can account for

“uncontroversial judgments about the relationship between experiences such as pleasure and the favourable assessment people usually make of their own life’s quality. It is these psycho-

pain and their degree of dis/value” (Metz 2011, 245). logical phenomena rather than the actual quality of a life that explain (the extent of) the posi-

tive assessment” (2006, 64). The most important psychological factor is the Pollyanna

Another alternative understanding of the four procreative asymmetries Benatar claims are Principle which says that people are strongly inclined towards optimism in their judgments.

best explained by the basic asymmetry between pain and pleasure is the idea that the four People recall positive experiences with greater frequency and reliability than negative experi-

asymmetries themselves are fundamental. As such they need not rely on a further asymmetry ences. This means that when people look back on the past, they tend to inflate the positive as-

for their explanation (2002, 354-355). For those who disagree, DeGrazia writes that another pects of it while minimizing the negative features. This also affects how people view the fu-

alternative explanation is that “we have much stronger duties not to harm than to benefit and ture, with a bias towards overestimating how well things will go. Subjective assessments

that this difference makes all the difference when we add the value of reproductive liberty. If about overall well-being are also consistently over-stated with respect to positive well-being

so, the asymmetry about procreative duties does not favor the fundamental asymmetry be- (Benatar 2006, 64-65). Just consider that “most people believe that they are better off than

tween benefit and harm championed by Benatar” (DeGrazia 2010 322). most others or than the average person” (Benatar 2006, 66). People’s own assessments of

their health do not correlate with objective assessments of it. The self-assessments of happi-

Ben Bradley argues that Benatar’s asymmetry fails because “there is a conceptual link be- ness of the poor are (almost) always equivalent to those offered by the rich. Educational and

tween goodness and betterness; but if pleasure were intrinsically good but not better than its occupational differences tend to make insignificant differences to quality of life assessments

absence, there would be no such link” (Bradley 2013, 39; see also Bradley 2010). too (Benatar 2006, 66-67).

5 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM6 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

Benatar claims that some of this Pollyannaism can be explained by “adaptation, accommoda- special concern both for one another and for each of their children and, in this way, for the

tion, or habituation” (2006, 67). If there is a significant downturn in a person’s life, their family as a whole” (1998, 143). At least for some people, procreating and the family unit are

well-being will suffer. However, they often readjust their expectations to their worse situation an important part of self-fulfillment. If Gewirth is right about the value of self-fulfillment,

and so eventually their self-assessments do not remain low; they move back towards the orig- and procreating contributes to self-fulfillment (at least for certain individuals), then these

inal level of well-being (Benatar 66-67). Subjective well-being report changes more accu- ideas constitute a reason to reject Deluded Gladness. At the very least, Gewirth’s theory of

rately than actual levels of well-being. People often also assess their own well-being by mak- self-fulfilment needs to be considered by Benatar in addition to the hedonistic theories,

ing relative comparisons to others. This means that self-assessments are more often compar- desire-fulfillment theories, and objective list theories he criticizes for encouraging inaccurate

isons of well-being, instead of assessments of actual well-being (Benatar 2006, 68). Benatar self assessments about quality of life.

further argues that on three main theories of how well a life is going–hedonistic theories,

desire-fulfillment theories, and objective list theories—assessments of how well one’s life is There are also important questions about whether the type of self-deception that seems to be

going are almost always too positive. He consistently points out that there is a distinction be- required by the Undeluded Gladness Argument is even possible. For example, some theories

tween the well-being that an individual ascribes to their own life and the actual well-being of of deception say that the deceiver knowingly and intentionally deceives another agent. But

that individual’s life. Benatar’s point is that these things do not often align. Once we have a this makes it difficult to see how self-deception is even possible. The deceiver would know

more accurate picture of how bad our lives really are, we should ask whether we would inflict they are deceiving themselves since deceit is intentional. A problem arises because the notion

the harms that occur in any ordinary life to a person who already exists. The answer, accord- that many people have simply deluded themselves into thinking their lives are better than

ing to Benatar is clearly ‘no’. (87-88). While it is possible to have a life that avoids most they really are could plausibly be thought to be a form of self-deception. And yet on the the-

harms, we are not in a good epistemic position to identify whether this will apply to our own ory of self-deception just described, we might wonder whether such self-deception is even

offspring. Given that the odds of avoidance are slim to begin with, procreation is akin to a possible. Connections between arguments for anti-natalism and self-deception are surely

rather nasty game of Russian roulette. worthy of more consideration. As it stands, the literature on anti-natalism in general has not

taken into account how different theories of self-deception might affect various arguments.

d. Challenges to Deluded Gladness

Regardless of the status of Benatar’s asymmetry thesis, he has also urged that our lives are

e. Overall’s Sexism Challenge to Benatar

far worse than the value at which we normally assess them. If it turns out that most lives are Christine Overall suggests that Benatar’s arguments, even if true, could have harmful conse-

actually not worth living, then this is a reason in itself not to procreate. But many have sug- quences for women. This is thus a moral rather than an epistemic challenge to anti-natalism.

gested that Benatar is mistaken about this fact. For instance, the fact that so many people are First, Overall holds that we do not have a duty to procreate because women have procreative

glad for their existence might be evidence in itself that such gladness is not deluded control over their own bodies (Overall 2012, 114). Second, she objects to the idea that there

(DeGrazia 2012, 164). Furthermore, any plausible moral theory must be able to account for are no costs associated with procreation, especially when one considers the nine-month preg-

the fact that most people are glad to be alive and think that their lives are going well nancy and delivery. Third, she worries that adopting Benatar’s views could actually lead to

(DeGrazia 2012, 158). more female infanticide and violence towards pregnant women. One question here, then, is

whether Benatar is sufficiently sensitive to the plight of women and the potential conse-

Another objection is that it fails to distinguish between higher-order pleasures and minor quences his arguments might have for them. Is anti-natalism ultimately a sexist position?

pains. Being tired or hungry is a harm, but it is outweighed by more valuable goods such as

loving relationships. Many of the negative features that Benatar associates with existence can Benatar responds to Overall by claiming that a right to not reproduce only exists if there is no

be overridden in this way (Harman 2009, 783). moral duty to reproduce. This reply closely links rights with duties. He also observes that the

costs women incur in procreating are not what is under dispute. The question at stake here is

Alan Gewirth has comprehensively defended the concept of self-fulfillment as key to a mean- whether it is permissible to procreate, not whether there are costs involved in procreating.

ingful life (1998). Although special relationships like the one between parents and children Finally, Benatar again reiterates that his arguments have to do with morality, which in this

violate egalitarian norms, having a family does not violate anyone else’s human rights. This case is distinct from the law. This is why he holds that “contraception and abortion should

forms part of the basis for Gewirth claiming that while “children have not themselves volun- not be legally mandatory even though contraception and early abortion are morally required”

tarily participated in setting up the family, their special concern for their parents and siblings (Benatar 2019, 366). Finally, Benatar suggests that Overall has not provided specific evidence

is appropriately viewed as derivative, both morally and psychologically, from the parents’ that anti-natalism would harm women. In turning this objection on its head, he claims that

7 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM8 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

anti-natalism might actually be good for women. For if widely adopted, then there might be The anti-natalist urges that procreation is analogous to the Gold manna case, not the Rescue

less of a tendency to view women primarily as child birthers and rearers (Benatar 2019, case. Procreation imposes a nontrivial and unconsented harm on the individual who is cre-

366-367). Which of Benatar or Overall is correct about the consequences of anti-natalism for ated for the purposes of bestowing a pure benefit. Those who would procreate, then, do not

women appears to be an empirical question. have the hypothetical consent of the individuals they procreate. Why is this the case? If an in-

dividual does not exist, she cannot be harmed nor benefitted. Language is misleading here

because when procreation does not occur there is no ‘individual’ who does not exist. There is

f. The Hypothetical Consent Argument simply nothing. There is no person in a burning car, no people on the island, and no free-

After Benatar’s work, the Hypothetical Consent Argument is probably the most discussed ar- floating soul waiting to be created. Procreation always involves bestowing a pure benefit,

gument for anti-natalism in the literature. The basic idea of the argument is that procreation something this argument says is impermissible.

imposes unjustified harm on an individual to which they did not consent (Shiffrin 1999;

Singh 2012; Harrison 2012). But what makes procreation an unjustified harm? For there are

clearly certain cases where harming an unconsenting individual is justified. Consider the fol-

g. Challenges to Hypothetical Consent

lowing oft-discussed case: Connected to the counterclaim that our lives usually go well is the idea that it is actually per-

missible to sometimes bestow a pure benefit on someone. There are cases where parents are

Rescue. A man is trapped in a mangled car that apparently will explode within minutes. better understood as exposing their child to certain harms rather than imposing such harms

You alone can help. It appears that the only way of getting him out of the car will break on them. Even if the act of procreation is ultimately best understood as imposing harms, it

his arm, but there is no time to discuss the matter. You pull him free, breaking his arm, may be justified in light of bestowing a pure benefit on the created individual. Parents often

and get him to safety before the car explodes (DeGrazia 2012, 151). make their children participate in activities where the gain is only a pure benefit; the activity

has nothing to do with avoiding a greater harm. Consider parents who encourage excellence

It is permissible in this case to harm the man in a nontrivial way without his consent because in scholarship, music, or athletics (DeGrazia 2012, 156-157). If this is right, then there is also

doing so clearly prevents the greater harm of his death. We can say that in such a case you reason to reject the Hypothetical Consent Argument for anti-natalism.

have the man’s hypothetical consent because he would (or rationally ought to) consent to the

harm if he could. But now consider a different case that is also frequently discussed:

h. The No Victim Argument

Gold manna. An eccentric millionaire who lives on an island wants to give some money Gerald Harrison argues that to coherently posit the existence of moral duties means there

to inhabitants of a nearby island who are comfortably off but not rich. For various rea- must be a possible victim (that can be hurt by the breaking of a duty). In light of this, he sug-

sons, he cannot communicate with these islanders and has only one way of giving them gests that “we have a duty not to create the suffering contained in any prospective life, but we

money: by flying in his jet and dropping heavy gold cubes, each worth $1 million, near do not have a duty to create the pleasures contained in any prospective life” (2012, 94). It is

passers-by. He knows that doing so imposes a risk of injuring one or more of the is- intuitive to think that we have the following two duties: (1) There is a duty to prevent suffer-

landers, a harm he would prefer to avoid. But the only place where he can drop the ing; and (2) There is a duty to promote pleasure (Harrison 2012, 96). Since there would be no

cubes is very crowded, making significant (but nonlethal and impermanent) injury victim if one failed to create happy people, this nicely explains why we do not have a duty to

highly likely. Figuring that anyone who is injured is nevertheless better off for having procreate even if we are sure our offspring will have very happy lives. However, this also ex-

gained $1 million, he proceeds. An inhabitant of the island suffers a broken arm in re- plains why we have a duty not to create suffering people since if we do so there are clearly

ceiving her gold manna (DeGrazia 2012, 151-152). victims (that is, the suffering people who were created).

What makes this eccentric millionaire’s actions impermissible in this case is that the benefit Since all lives contain suffering, there is a duty to never procreate. For in procreating, we al-

imposed does not involve avoiding a greater harm. This is what ethicists refer to as a pure ways fail to do our duty to prevent suffering because there is an actual victim of suffering.

benefit. So, the idea is that it is impermissible to confer a pure benefit on someone who has That an individual has an on balance or overall happy life cannot outweigh the duty to not

not consented to it, while it is permissible to confer a benefit on someone to prevent a non- procreate because in failing to procreate there is no victim (Harrison 2012, 97-99).

trivial harm to them. In the Rescue case there is hypothetical consent to the harm, whereas in

the Gold manna case there is no such consent. According to Harrison, the duty not to procreate is therefore underpinned by two prima facie

duties. First, we have a duty to prevent harm. Second, we have a “duty not to seriously affect

9 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM10 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

someone else with [their] prior consent” (2012, 100). However, Harrison acknowledges that Two well-known consequentialist ethical theories are act-utilitarianism and rule-

“[f]ulfilling this duty will mean that no more lives are created and this […] is a bad state of af- utilitarianism. The former focuses on evaluating the permissibility of individual actions

fairs, even if it is not bad for anyone” (2012, 100). The reason we do not have a duty from en- based on their effects while the latter instead seeks to discover a set of rules which if followed

suring that this state of affairs does not obtain is that doing so would involve bringing people will maximize positive effects. This strategy involves categorizing different types of action. It

into existence who will in fact be harmed by their existence. On the other hand, that no more has been observed that a different type of utilitarianism, negative utilitarianism, entails anti-

lives are created does not harm anyone. Harrison further notes that though his position en- natalism (for example, Belshaw 2012; Metz 2011). On this moral theory, the only salient as-

tails the strange claim that a person can be happy for being brought into existence, even pect of morality is avoiding pain. When assessing whether a particular action is permissible

though they are harmed by it, there is nothing incoherent in it. For example, someone could (or what set of rules to follow) we should only ask whether the effects of that action will be

place a large bet in our name without our consent. Doing so is wrong even if the bet is won painful. Obtaining pleasure (in any sense) simply does not factor into moral reasoning on

and we ultimately benefit from it (Harrison 2012, 100). this view.

Since every life contains at least some pain, it is best to avoid it by simply not starting that life

i. The Exploitation Argument in the first place. According to negative utilitarianism, no amount of pleasure could outweigh

The Exploitation Argument for anti-natalism, offered by Christopher Belshaw, involves the even the smallest degree of pain, since pleasure does not count for anything morally. While

idea that procreation fundamentally involves exploitation (Belshaw 2012). Consider that we the connection between negative utilitarianism and anti-natalism has been identified, anti-

have the intuition that we should end the lives of animals who are suffering even if there is natalists have hardly been eager to adopt this as an argumentative strategy. Not only is nega-

some chance that they could be happy in the future (Belshaw 2012, 120). Suppose that there tive utilitarianism a highly controversial moral theory in itself, but it seems to entail pro-

are categorical desires, which involve reasons to ensure our future existence. Further suppose mortalism, the view that people should end their lives. This is, after all, seemingly the best

that there are also conditional desires, which, assuming a future, offer reason to think that way to avoid any future pains. Since many anti-natalists have gone to great lengths to show

one state of affairs will obtain over some other one (Belshaw 2012, 121). Belshaw continues to that the view does not in fact entail pro-mortalism, appealing to negative utilitarianism is

suggest that while a baby is a human animal, it is necessarily not a person in a more robust largely avoided by proponents of anti-natalism.

sense. This is because babies are not psychologically knit together, nor do they have categori-

cal or conditional desires (Belshaw 2012, 124). Likewise, there is no continuity between a

baby and the adult it becomes; it is implausible to think these are the same person. For a

k. Broader Implications

baby: It is important to note that there is a difference between offering theoretical arguments for a

particular conclusion and enforcing policies which ensure that conclusion is enacted. The

[H]as no developed notion of itself, or of time, no desire to live on into the future, no philosophical debate about anti-natalism is almost entirely theoretical. Many authors defend-

ability to think about the pain and decide to endure it. Further, if we think seriously ing anti-natalism seem well aware that there are strong prudential and moral reasons not to

about a baby’s life we’ll probably agree it experiences pain in more than trivial force anti-natalist policies on people. Likewise, though they think anti-natalism is true there

amounts. Even perfectly healthy babies come into the world screaming, cry a lot, suffer is a general recognition that it will not be widely adopted in practice.

colic and teething pains, keep people awake at night. None of us can remember any-

thing about it (Belshaw 2012, 124).

2. Additional Objections to Philanthropic Arguments

An important claim of the Exploitation Argument is that such a life is not worth living. Even

if only through a baby can a person be brought into existence, this does not compensate the a. Procreative Autonomy

baby for the harm it experiences (Belshaw 2012, 124). This means that we must exploit ba-

One reason that has been offered to reject anti-natalist conclusions in general is that procre-

bies in order for there to be humans. I might be glad that there was a baby who was exploited

ative autonomy is more important (for example, Robertson 1994). Procreative autonomy is

in order for me to come to exist, but it would still be better for that baby had it never been

important because procreation is often central to an individual’s identity, dignity, and life’s

born. In procreating “we are inevitably free-riding on the several misfortunes of small, help-

meaning. In other words:

less and shortlived creatures.” (Belshaw 2012, 126).

Whether or not to have children, when and by what means to have them, how many to

j. Negative Utilitarianism have, and similar choices are extremely important to us. These decisions greatly affect

11 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM12 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

our narrative identity—for example, whether or not we become parents, what sort of has also developed a distinct misanthropic argument. He also speculates that misanthropic

family we have—and much of the shape of our lives. Few decisions seem as personal arguments are even more likely to be met with scorn than philanthropic arguments. This is

and far-reaching as reproductive decisions. That procreative freedom is very important because while the latter are in some sense about protecting individuals, the former focuses on

seems too obvious to require further defense (DeGrazia 2012, 155). the bad aspects of humanity (Benatar 2015, 35). Whether Benatar is right about this remains

an open question as most of the anti-natalist literature tends to focus on the philanthropic ar-

Those who are attracted to this type of response could admit that anti-natalists get at impor- guments.

tant truths about procreation, but simply maintain that procreative autonomy is more impor-

tant. Here’s Benatar’s basic misanthropic argument for anti-natalism:

(1) We have a (presumptive) duty to desist from bringing into existence new members

b. Pro-Mortalism of species that cause (and will likely continue to cause) vast amounts of pain, suffering

Another objection that sometimes gets levelled against anti-natalism is that it entails pro- and death.

mortalism, the view that individuals ought to end their lives. As noted above, this is probably

one reason why anti-natalists have avoided tying their views to negative utilitarianism. (2) Humans cause vast amounts of pain, suffering and death.

However, it seems doubtful that any of the main arguments for anti-natalism entail pro-

mortalism. With respect to Benatar’s work, he consistently states that even though lives are Therefore,

not worth creating, most are worth continuing. The same can be said of the Hypothetical

Consent Argument. Once an individual has received the pure benefit of existence, realizing (3) We have a (presumptive) duty to desist from bringing new humans into existence.

this fact does not imply they should commit suicide, just as the islander whose arm is broken (Benatar 2012, 35).

by the gold manna ought not to end his life. The No Victim Argument neatly avoids this

worry because one has a duty to promote one’s own pleasure. Once one comes into existence

there is an actual victim if one fails to promote their own pleasures, so there is a duty to pro-

a. Premise 2 of the Misanthropic Argument

mote one’s pleasure. Presumably, for most people and throughout most of their lives, suicide Premise 2 is the one in most need of defense. To defend it Benatar appeals to humanity’s gen-

would not fulfill this duty. Finally, the Exploitation Argument also avoids this objection. For erally poor impulses, their destructiveness towards one another, the suffering they cause

on this argument most adult human lives are indeed worth continuing, the problem is rather other animals, and the damage that they do to the environment.

the exploitation of the babies to get such lives in the first place. Benatar says that even though

he holds most lives are going poorly, it does not entail that we should commit suicide. This is

i. Harm to Humans

because we typically each have interests in continuing to live. Our lives would have to be

worse than death, which is extremely bad, in order for suicide to be justified. This will only Regarding humanity’s poor impulse control in general, Benatar is quick to observe that the

rarely be the case (Benatar 2013, 148). vast majority of human achievements are not possible for most humans. We therefore should

not judge the human species in general based on the performance of exceptional people. In

fact, it is now well-document that humans exhibit numerous cognitive biases which cause us

3. The Misanthropic Argument to both think and act irrationally (Benatar 2015, 36). Consider that:

The philanthropic arguments which were discussed in the previous section conclude that be-

cause of the harm done to the created individual, it is always all things considered wrong to For all the thinking that we do we are actually an amazingly stupid species. There is

procreate. This section explains what is known as the misanthropic argument for anti- much evidence of this stupidity. It is to be found in those who start smoking cigarettes

natalism. Unlike the philanthropic arguments, this argument focuses on the harm caused by (despite all that is known about their dangers and their addictive content) and in the

the individuals who are created. The conclusion of this argument is slightly weaker, claiming excessive consumption of alcohol—especially in those who drive while under its influ-

that procreation is almost always impermissible, or only impermissible given the current sit- ence. It is to be found in the achievements of the advertising industry, which bear am-

uation in which procreation occurs. ple testament to the credulity of humanity (Benatar 2015, 36).

Though Benatar is best known for offering a philanthropic argument for anti-natalism, he These cognitive failings often cause humans to harm each other. We exhibit an extreme ten-

13 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM14 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

dency toward conformity and following authority, even when doing so leads us to hurt each mals are painful and stressful” (Benatar 2015, 44). The average meat eater will consume at

other (Benatar 2015, 37). least 1690 animals in their lifetime (a rather low estimate) which is an extremely large

amount of harm (Benatar 2015, 54-55).

Even if one contends that our intelligence compensates for these moral deficiencies, it is diffi-

cult to defend this claim in light of human destructiveness:

iii. Harm to the Environment

Many hundreds of millions have been murdered in mass killings. In the twentieth cen- Humans are also incredibly destructive to the environment. The human population is grow-

tury, the genocides include those against the Herero in German South-West Africa; the ing exponentially and the negative environment effects per person continue to increase too.

Armenians in Turkey; the Jews, Roma, and Sinti in Germany and Nazi-occupied This is partly due to industrialization and a steady growth in per capita consumption

Europe; the Tutsis in Rwanda; and Bosnian Muslims in the former Yugoslavia. Other (Benatar 2015, 48). As a result:

twentieth-century mass killings were those perpetrated by Mao Zedong, Joseph Stalin,

and Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge. But these mass killings were by no means the first. The consequences include unprecedented levels of pollution. Filth is spewed in massive

Genghis Khan, for example, was responsible for killing 11.1% of all human inhabitants quantities into the air, rivers, lakes, and oceans, with obvious effects on those humans

of earth during his reign in the thirteenth century […] The gargantuan numbers should and animals who breath the air, live in or near the water, or who get their water from

not obscure the gruesome details of the how these deaths inflicted and the sorts of suf- those sources. The carbon dioxide emissions are having a ‘greenhouse effect,’ leading to

fering the victims endure on their way to death. Humans kill other humans by hacking, global warming. As a result, the icecaps are melting, water levels are rising, and climate

knifing, hanging, bludgeoning, decapitating, shooting, starving, freezing, suffocating, patterns are changing. The melting icecaps are depriving some animals of their natural

drowning, crushing, gassing, poisoning, and bombing them (Benatar 2015, 39). habitat. The rising sea levels endanger coastal communities and threaten to engulf

small, low-lying island states, such as Nauru, Tuvalu, and the Maldives. Such an out-

Humans also do not just murder each other. They also “rape, assault, flog, maim, brand, kid- come would be an obvious harm to its citizens and other inhabitants. The depletion of

nap, enslave, torture, and torment other humans” (Benatar 2015, 40). Though these are the the ozone layer is exposing earth’s inhabitants to greater levels of ultraviolet light.

worst harms, humans also frequently “lie, steal, cheat, speak hurtfully, break confidences and Humans are encroaching on the wild, leading to animal (and plant) extinctions. The de-

promises, violate privacy, and act ungratefully, inconsiderately, duplicitously, impatiently, struction of the rain forests exacerbates the global warming problem by removing the

and unfaithfully” (Benatar 2015, 43). Even if justice is sought, it is hardly ever achieved. trees that would help counter the increasing levels of carbon dioxide (Benatar 2015,

Many of the most evil leaders in human history ruled for the course of their natural lives, 48).

while others had peaceful retirements or were only exiled (Benatar 2015, 43). In sum, “‘Bad

guys’ regularly ‘finish first’. They lack the scruples that provide an inner restraint, and the ex- CO2 emissions per year per person are massive. While they are lower in developing countries,

ternal restraints are either absent or inadequate” (Benatar 2015, 43). they tend to have much higher birthrates than their wealthier counterparts. As the popula-

tion increases, adding more humans will invariably harm the environment.

ii. Harm to Animals

The amount of suffering that humans inflict on animals each year is hard to fathom. Given

b. Premise 1 of the Misanthropic Argument

that the vast majority of humans are not vegetarians or vegans, most of them are complicit in Notice that premise 1 of this argument does not claim that we should kill members of a dan-

this suffering. Consider that “[o]ver 63 billion sheep, pigs, cattle, horses, goats, camels, buf- gerous species or stop that dangerous species from procreating. Instead, it merely says “that

falo, rabbits, chickens, ducks, geese, turkeys, and other such animals are slaughtered every one should oneself desist from bringing such beings into existence” (Benatar 2015, 49). For

year for human consumption. In addition, approximately 103.6 billion aquatic animals are this premise to be true it also does not have to be the case that every single member of the

killed for human consumption and non-food uses” (Benatar 2015, 44). These numbers ex- species is dangerous. The likelihood that a new member of the species will cause significant

clude the hundreds of millions of male chicks killed every year because they cannot produce harm is enough to make procreation too dangerous to be justified. Also notice that this

eggs. It also excludes the millions of dogs and cats that are eaten in Asia every year (Benatar premise is silent on the species in question. It would be easily accepted if it were about some

2015, 44). Each year there are also 5 billion bycatch sea animals, which are those caught in non-human species: “Imagine, for example, that some people bred a species of non-human

nets, but not wanted. Finally, at least 115 million animals are experimented on each year animal that was as destructive (to humans and other animals) as humans actually are. There

(Benatar 2015, 45). Furthermore, “[t]he deaths of the overwhelming majority of these ani- would be widespread condemnation of those who bred these animals” (Benatar 2015, 49).

15 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM16 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

c. The Presumptive Duty Not to Procreate oping countries who are suffering.

Presumptive duties are defeasible. The duty only holds if there are no good reasons to do oth-

Benatar is so far the only one to make connections between Singer’s argument and anti-

erwise (Benatar 2015, 51). One possible way of avoiding the misanthropic argument is to

natalism. Here is his interpretation of Singer’s argument:

counter that the good that humans do is pervasive enough to often defeat this presumptive

duty. If this is right, then procreation will often be permissible (Benatar 2015, 51). However,

Singer’s Poverty Relief argument on our duty to the poor

in light of the vast harms that humans do, meeting the burden of proof regarding the amount

of counteracting good that humans do, is going to be extremely difficult. Remember that the

(1) If we can prevent something bad from happening, without sacrificing anything of

benefits here do not just have to counter the harms to other humans, but the harm done to

comparable moral importance, we ought to do it.

billions of animals every year, in addition to the environment more generally (Benatar 2015,

52). We would also need a clear understanding of what constitutes good outweighing bad.

(2) Extreme poverty is bad.

Does saving two lives outweigh the bad of one violent murder? Benatar is doubtful, claiming

the number of lives needing to be saved to outweigh the bad is much higher than two (2015,

(3) There is some extreme poverty we can prevent without sacrificing anything of com-

52). Likewise, offering benefits to future generations cannot count as part of the good that

parable moral importance.

outweighs the bad because such humans would not exist if the presumptive duty were fol-

lowed in the first place. Under the current conditions of the world, more new humans add

Therefore,

more additional harms than they do any offsetting benefits (Benatar 2015, 54). Finally, a

more modest response is the assertion that the presumptive duty not to procreate can occa-

(4) We ought to prevent some extreme poverty (Benatar 2020, 416).

sionally be defeated. Perhaps the children of a particular individual would do enough offset-

ting good that it would justify creating them (Benatar 2015, 54). While this scenario is cer-

This argument nicely avoids disagreement between utilitarians and non-utilitarians because

tainly possible, it is doubtful that those considering procreating will be in a good position to

both sides will agree that we should prevent bad things from happening even if there is some

know this about their future offspring.

disagreement about how to measure bad or just what constitutes a comparable moral sacri-

fice. Benatar observes that Singer’s argument has clear implications for procreative ethics.

4. Anti-Natalism and Duties to the Poor We must either accept those implications or give up Singer’s conclusion.

Thus far, very little has been said about how our duties to the poor are impacted by anti-

What does Singer’s argument imply about procreative ethics? The first implication has to do

natalism. However, there are important connections between duties to the poor and procre-

with the opportunity costs of having children. His argument “implies that, at least for now,

ative ethics. Consider the following scenario: Suppose that you are walking on your way to

the relatively affluent ought to desist from having children because they could use the re-

work in the morning. You find yourself walking by a pond and observe a drowning child. If

sources that would be needed to raise resulting children to prevent extreme poverty”

you stop to help the child, you will probably ruin your nice new clothes and also be late for

(Benatar 2020, 417). In wealthy countries it costs anywhere from two hundred thousand to

work. There is no tangible risk of you drowning since the pond is not very deep for an adult.

three hundred thousand dollars to raise a child from birth to the age of eighteen years old.

There is also no one else around. If you do not help the child now, then they will almost cer-

Having children should be forgone by the wealthy so that they can spend this money on alle-

tainly drown. What should you do? This example is modified from Peter Singer, a famous

viating extreme poverty. It also implies that even adoption may be impermissible for the

utilitarian who is well-known for defending the idea that we have rather strong obligations to

wealthy if their resources are still more effectively spent elsewhere (Benatar 2020, 418).

help the poor, particularly those in developing countries. Singer thinks it is obvious what you

should do in this case. You should stop to help the drowning child. The value of the child’s

Another implication of Singer’s argument has to do with natality costs. It implies that many

life is worth much more than what it costs for you to help them, namely, your new clothes

people should refrain from procreating, especially the poor, because of the bad things that

and having to explain to your boss why you were late. The next step is to draw an analogy be-

will inevitably happen to those they bring into existence (Benatar 2020, 420). Sacrificing

tween the children in the pond and the less-well off developing nations. In fact, Singer sug-

procreation is not of comparable moral importance since no one is harmed by not being

gests that people in wealthier countries are in the very position of walking past ponds with

brought into existence. So, it is more important that the poor refrain from procreating to pre-

drowning children everyday. The people we could help are just a bit farther away and we do

vent their children from experiencing extreme poverty. Benatar suggests that if Singer is

not see them directly in front of us. But this is not a morally significant difference. So, those

right, we might even have a duty to prevent the poor from procreating, though this would be

of us in wealthier countries need to devote a lot more of our resources to help those in devel-

17 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM18 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

the prevention of a bad thing, not relief from it. Of course, Benatar is well aware that this brought into existence God allows them to commit a great deal of evil because of the value of

conclusion is unlikely to be met by many with approval. According to Benatar at least, no one morally significant freedom, to name just one theistic response to evil. However, it is another

would be harmed if people refrained from procreating for these reasons, and much suffering to say that such solutions justify the act of bringing humans into existence who do not al-

would be prevented. While these ideas are far from uncontroversial, and likely to even cause ready exist.

offense to some, it is clear that more work needs to be done exploring how our duties to the

poor are connected to anti-natalism. Another underexplored connection between a theistic perspective and misanthropic argu-

ments for anti-natalism regards humanity’s treatment of the environment. In the Judeo-

Christian tradition, for example, the planet is a gift from God to humans. We are supposed to

5. Future Directions cherish, protect, and look after the environment and the non-human animals that it contains.

This section identifies three potential areas for future research into anti-natalism. The first Clearly, just the opposite has happened. In light of the fact that population increase is di-

regards a lack of direct interaction between religious perspectives and arguments for anti- rectly tied to the climate crises, might those in religious traditions who hold that the planet is

natalism. The second involves the need for more interaction between anti-natalism and non- a gift be obligated to cease procreating? These and related ideas are at least worthy of explo-

Western approaches to ethics. The third is about the surprising dearth of engagement with ration by scholars of religion.

anti-natalism in the philosophical literature on population ethics.

b. Anti-Natalism and Non-Western Ethics

a. Religious Perspectives on Anti-Natalism The philosophical literature on anti-natalism is dominated by those working in Western phi-

Perhaps more than any other group, religious believers cringe when they hear defenses of losophy. It is important to briefly consider ways in which debates about procreative ethics

anti-natalism. In the classical monotheistic tradition, for example, existence is held to be in- could be forwarded by including non-Western ethical perspectives, African philosophy, for

trinsically good. This has played out in the prizing of the nuclear family. It might seem rather example. This literature emerged (professionally) in the 1960s, with the demise of coloniza-

unsurprising, then, that religious thinkers have had little to say about the anti-natalist de- tion and the rise of literacy rates on the African continent. There are three main branches of

bate. However, the rejection of anti-natalism out of hand by the religious believer might turn African ethics. First, African thinkers distinguish the normative conception of personhood

out to be short-lived. First, theists who are committed to the claim that existence is intrinsi- from the metaphysical or biological conceptions of the person (Menkiti 1984). On this under-

cally good are committed to the further claim that there are literally no lives not worth con- standing of ethics, the most central feature of morality is for individuals to develop their per-

tinuing. Some might find this conclusion difficult to accept. For even if it were to apply to all sonhood. This is typically done by exercising other-regarding virtues and hence can only be

actual lives, it is easy to think of possible lives that are so awful they are not worth continu- accomplished within the context of community. On this view personhood is a success term

ing. Second, in holding that existence is intrinsically good, theists are under pressure to ex- such that one could fail to be a person (in the normative sense) (Ikuenobe 2006; Molefe

plain why they are not obligated to procreate as much as possible. They need to explain this 2019). Second, harmony has been postulated as the most important aspect of morality in in-

because an obligation to procreate as much as possible is absurd. digenous African societies. Harmony is about establishing a balance or equilibrium amongst

humans with each other and all else, including the natural world. Disrupting the harmony of

If theists can coherently explain why existence is intrinsically good while avoiding the prob- the community is one of the worst things an individual can do. That personhood and har-

lematic results just mentioned, they may well have an answer to philanthropic arguments for mony are both understood within the context of relating to others shows why, in part, com-

anti-natalism. They can acknowledge that procreation is a weighty moral decision that ought munity is of supreme importance in the African tradition (Metz forthcoming; Paris 1995;

to be taken more seriously than prospective couples often take it. They can even concede that Ramose 1999). Third, vitalist approaches to morality say that everything, both animate and

certain cases of procreation probably are impermissible. However, if procreating really is to inanimate, are imbued with life force, a kind of imperceptible energy. On this approach, the

bring about an individual whose existence is intrinsically valuable, then many instances of goal of morality is to increase life force in oneself and others. Procreation is valuable because

procreation will indeed be permissible. Yet this does not necessarily let the theist off the hook it creates a being with life force (Magesa 1997).

when it comes to the misanthropic arguments for anti-natalism. The harm that most human

lives will do seems hard to deny. One possibility for the theist is to say that this type of con- On African personhood accounts of morality, an individual can only develop and exercise

cern reduces to the problem of evil. Therefore, solutions to the problem of evil can be used as moral virtue in the context of the community, traditionally including not merely present gen-

resources to show why procreation is permissible even in light of the harm humans do. But erations but also future ones, often called the ‘not-yet-born’. To deny the importance of the

there are many questions for such a strategy. It is one thing to say that once humans are continuance of the community through procreation seems to fly in the face of such an ethic.

19 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM20 of 24 3/25/2022, 4:08 PM

Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/Anti-Natalism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://iep.utm.edu/anti-natalism/

Likewise, in African relational ethics, harmony amongst individuals is of the upmost impor- 1804 to reach one billion people. A century ago, the world had approximately 1.8 billion peo-

tant. Again, the continuance of the community through procreation appears vital to the exis- ple. However, the current population sits at approximately 7.8 billion people (Hedberg 2020,

tence of and promotion of harmony in the community. In other words, there can be no per- 3). Hedberg contends that “population is a serious contributor to our environmental prob-

sonhood or harmony without a community of persons. Given its importance, the community lems, we are morally obligated to pursue the swift deceleration of population growth, and

ought to continue via procreation. Finally, on vitality accounts, anti-natalism appears to deny there are morally permissible means of achieving this outcome—means that avoid the coer-

the importance of creating beings with life force. There is thus a rather apparent tension be- cive measures employed in the past” (Hedberg 2020, 3). Indeed, such coercive measures in

tween anti-natalism and African communitarian ethics. the past are probably part of the reason that many environmental organizations and govern-

ments which claim to care deeply about the climate crisis virtually never mention the popula-

However, consider that, despite initial appearances, it could be argued that misanthropic ar- tion. Yet it does not matter if humans become more efficient and individually have a less bad

guments for anti-natalism are in conflict with African ethics. Furthermore, it is plausible that impact on the environment if such improvements are outpaced by population growth. So far,

philanthropic arguments are consistent with at least some line of thought in African ethics. any improvements in individual impact have been greatly outpaced by population growth. On

While tensions may remain between the two views, much more exploration of a possible syn- the very plausible (if not obvious) assumptions that (1) climate change poses a significant and

thesis between anti-natalism, and African ethics is needed. There are least five possible rea- existential threat to the human species; and (2) that population growth contributes to climate

sons why these two views might be consistent with each other (and in some cases mutually change, environmental ethicists need to start contending with misanthropic arguments for

supportive). First, African ethics emphasizes doing no harm to the community. Procreation anti-natalism. Remember that these arguments leave open the possibility (however small)

right now harms many communities, given that creating more people means making valuable that humans may not cause so much damage in the future and as such it might not be imper-

resources even more scarce, for example. Second, procreation harms the global community missible to bring more into existence.

and environment. An important line in African thought is that humans should strive to be in

harmony with the natural environment, not just with each other. Until we find ways to

greatly reduce our carbon footprints, procreating harms the environment and thereby pro-

d. Human Extinction as the Goal of Anti-Natalism

duces disharmony. Third, even if strong philanthropic versions of anti-natalism which do not At the beginning of Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence, Benatar

rely on better resource distribution or environmental considerations are followed, consider acknowledges that his work will likely have no (or almost no) impact on people’s procreative

that even if everyone refrained from procreating there would still be a human community for choices. He writes:

many years (the next 80 or so), right up until the very last person existed. The opportunity to