Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Safari - Jan 12, 2024 at 11:54 AM

Safari - Jan 12, 2024 at 11:54 AM

Uploaded by

pjpmzd6b9cCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Rule 115 - Rules of CourtDocument6 pagesRule 115 - Rules of CourtMigoy DA100% (1)

- Churchille Mari vs. Gonzales - DigestDocument4 pagesChurchille Mari vs. Gonzales - DigestDudly Rios67% (3)

- 3 - People vs. Andrade, G.R. No. 187000, November 24, 2014Document7 pages3 - People vs. Andrade, G.R. No. 187000, November 24, 2014Michelle CatadmanNo ratings yet

- 3 People V AndradeDocument9 pages3 People V AndradeFrances Angelica Domini KoNo ratings yet

- MTQ 3Document10 pagesMTQ 3naxreal24No ratings yet

- CRIM PRO - Cases.F1Document11 pagesCRIM PRO - Cases.F1Jessie May Althea VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- People v. AndradeDocument4 pagesPeople v. AndradeBrian Kelvin PinedaNo ratings yet

- CASE POOL Crim 2 Cases Atty. Suyat Syllabus PDFDocument142 pagesCASE POOL Crim 2 Cases Atty. Suyat Syllabus PDFMheryza De Castro PabustanNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz vs. PeopleDocument3 pagesDela Cruz vs. PeopleShery Ann ContadoNo ratings yet

- WEEK 6 - No. 1 Failure To Move Quash or To Allege Any Ground Thereof (People Vs Andrade)Document1 pageWEEK 6 - No. 1 Failure To Move Quash or To Allege Any Ground Thereof (People Vs Andrade)saripmohan03No ratings yet

- Application For BailDocument6 pagesApplication For BailgeorgecloneyNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz V PEOPLEDocument10 pagesDela Cruz V PEOPLEMp CasNo ratings yet

- What Is Confirmatory Test in Drugs CasesDocument2 pagesWhat Is Confirmatory Test in Drugs CasesRoberto Rivero IIINo ratings yet

- 4 de La Cruz Vs People (SI-Drugtest On Accused Not Charged Under RA9165)Document9 pages4 de La Cruz Vs People (SI-Drugtest On Accused Not Charged Under RA9165)Avatar09No ratings yet

- De La Cruz vs. People of The Philippines - Special Penal LawsDocument2 pagesDe La Cruz vs. People of The Philippines - Special Penal Lawsحنينة جماءيلNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE vs. SullanoDocument2 pagesPEOPLE vs. SullanoTrishaNo ratings yet

- People Vs SullanoDocument6 pagesPeople Vs Sullanomaricar bernardinoNo ratings yet

- Dismissed Drug CasesDocument71 pagesDismissed Drug CasesErnesto AbesamisNo ratings yet

- Vaporo and Tulilik Case - Illegal Search - Two Searches ConductedDocument6 pagesVaporo and Tulilik Case - Illegal Search - Two Searches ConductedRothea SimonNo ratings yet

- GR No 227394Document12 pagesGR No 227394russelsithliNo ratings yet

- JAIME D. DELA CRUZ, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines, RespondentDocument8 pagesJAIME D. DELA CRUZ, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines, RespondentredlacsonNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz vs. PeopleDocument7 pagesDela Cruz vs. PeopleJade QSNo ratings yet

- Social Justice Society v. Dangerous Drugs BoardDocument16 pagesSocial Justice Society v. Dangerous Drugs Boardred gynNo ratings yet

- Jaime Dela Cruz v. PeopleDocument13 pagesJaime Dela Cruz v. PeopleCourtney TirolNo ratings yet

- Vaporoso v. People of The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesVaporoso v. People of The Philippinessuis generisNo ratings yet

- Dela CruzDocument10 pagesDela CruzjoNo ratings yet

- Chain of CustodyDocument8 pagesChain of CustodyKuya Kim100% (1)

- People vs. ManlangitDocument10 pagesPeople vs. ManlangitMrChips JayNo ratings yet

- Article 80-113Document55 pagesArticle 80-113Sweet jenesie MirandaNo ratings yet

- (As Modified by RA 10640) : "Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002"Document41 pages(As Modified by RA 10640) : "Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002"Peter ManuelNo ratings yet

- 2014) Laid Down The Links That Must Be Established in The Chain of Custody, To Wit: "First, The SeizureDocument6 pages2014) Laid Down The Links That Must Be Established in The Chain of Custody, To Wit: "First, The Seizuredeuce scriNo ratings yet

- Sec 15 Acquitted - Not Arrested But Subjected To Mandatory Drug TestingDocument21 pagesSec 15 Acquitted - Not Arrested But Subjected To Mandatory Drug TestingCon QuerorNo ratings yet

- 007 Dela Cruz vs. PeopleDocument8 pages007 Dela Cruz vs. Peoplest3ll4_my8No ratings yet

- People vs. ManlangitDocument8 pagesPeople vs. ManlangitGEiA Dr.No ratings yet

- Demurrer 2Document8 pagesDemurrer 2Janus Mari AbanNo ratings yet

- First G.R. No. People of Siu Ming Tat And: VersusDocument3 pagesFirst G.R. No. People of Siu Ming Tat And: VersusJohannes YapyapanNo ratings yet

- RA 9165 SPL SummaryDocument4 pagesRA 9165 SPL SummaryRay Lambert Menchavez100% (1)

- Estipona v. Hon Lobrigo - OdtDocument15 pagesEstipona v. Hon Lobrigo - OdtDayanski B-mNo ratings yet

- Nisperos y Padilla v. PeopleDocument46 pagesNisperos y Padilla v. Peoplezedric santosNo ratings yet

- A. People Vs Sullano, GR No. 228373 Dated March 12, 2018Document11 pagesA. People Vs Sullano, GR No. 228373 Dated March 12, 2018Princess Marjorie RebutNo ratings yet

- Digest - SJS Vs Dangerous Drugs BoardDocument4 pagesDigest - SJS Vs Dangerous Drugs BoardRosemary Red100% (1)

- Dela Cruz V PeopleDocument2 pagesDela Cruz V PeopleMaureen CoNo ratings yet

- Plea Bargain OrderDocument3 pagesPlea Bargain OrderitssaabNo ratings yet

- Iii. Tumabini v. People, G.R. No. 224495, February 19, 2020Document3 pagesIii. Tumabini v. People, G.R. No. 224495, February 19, 2020Dan K100% (1)

- Illegal Drugs CasesDocument23 pagesIllegal Drugs CasesmimslawNo ratings yet

- Chain of Custody RuleDocument39 pagesChain of Custody RuleRLO1100% (2)

- People v. GuanzonDocument10 pagesPeople v. Guanzonsuperwezowski7No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 217097 - Search and SEizuresDocument10 pagesG.R. No. 217097 - Search and SEizuresSANDRA MAE BONRUSTRONo ratings yet

- Judgment On Lauta Drug CaseDocument6 pagesJudgment On Lauta Drug CaseLahnee F. MagatNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines V Angel Angeles y ArimbuyutanDocument2 pagesPeople of The Philippines V Angel Angeles y ArimbuyutanErneylou RanayNo ratings yet

- Drugs CasesDocument4 pagesDrugs CasesrobelinNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument19 pagesCase DigestEsto, Cassandra Jill SumalbagNo ratings yet

- Tumabini Vs PeopleDocument7 pagesTumabini Vs PeopleAthea Justine YuNo ratings yet

- People v. AndradeDocument2 pagesPeople v. AndradejasminealmiraNo ratings yet

- Santos vs. People (Full Text, Word Version)Document11 pagesSantos vs. People (Full Text, Word Version)Emir Mendoza100% (1)

- Drugs DigestDocument4 pagesDrugs DigestjasminezeroNo ratings yet

- Latest Juris Drugs 3 2020Document8 pagesLatest Juris Drugs 3 2020dyosaNo ratings yet

- ALCALA, Sheena Mae - 1st DraftDocument6 pagesALCALA, Sheena Mae - 1st Draftdwight yuNo ratings yet

- People vs. SanchezDocument5 pagesPeople vs. SanchezmNo ratings yet

- The Nuremberg Trials: Complete Tribunal Proceedings (V. 2): Trial Proceedings From Preliminary Hearing Held on 14 November 1945 to 30 November 1945From EverandThe Nuremberg Trials: Complete Tribunal Proceedings (V. 2): Trial Proceedings From Preliminary Hearing Held on 14 November 1945 to 30 November 1945No ratings yet

- The Nuremberg Trials (V. 2): Trial Proceedings From Preliminary Hearing Held on 14 November 1945 to 30 November 1945From EverandThe Nuremberg Trials (V. 2): Trial Proceedings From Preliminary Hearing Held on 14 November 1945 to 30 November 1945No ratings yet

- 1 People Vs Goce, 247 SCRA 780 (1995)Document6 pages1 People Vs Goce, 247 SCRA 780 (1995)Perry YapNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Q and A 21Document204 pagesCriminal Procedure Q and A 21Mary Jane GarinNo ratings yet

- Chelsea Cook Domestic Violence/Assault Charges in Front of ChildrenDocument3 pagesChelsea Cook Domestic Violence/Assault Charges in Front of ChildrenAdam ForgieNo ratings yet

- UNITED STATES of America Ex Rel. Frank PHELAN, Appellant, v. Joseph R. BRIERLEY, Warden, State Correctional Institution, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaDocument42 pagesUNITED STATES of America Ex Rel. Frank PHELAN, Appellant, v. Joseph R. BRIERLEY, Warden, State Correctional Institution, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents Leodegario A Barayang, SR: First DivisionDocument4 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents Leodegario A Barayang, SR: First DivisionIrish Joi TapalesNo ratings yet

- 2 Heirs of Honrales V HonralesDocument8 pages2 Heirs of Honrales V HonralesFrances Angelica Domini KoNo ratings yet

- Crim Pro FinalsDocument12 pagesCrim Pro FinalsAxel FontanillaNo ratings yet

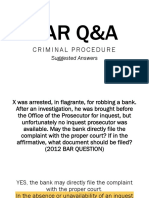

- BAR QnADocument107 pagesBAR QnAJune Vincent Ferrer III50% (2)

- Bayani Subido JR Vs Sandiganbayan Et AlDocument5 pagesBayani Subido JR Vs Sandiganbayan Et AlJoshua Janine LugtuNo ratings yet

- CrimProc 1 25Document27 pagesCrimProc 1 25Rogelio A.C Jr.No ratings yet

- Albert vs. SandiganbayanDocument6 pagesAlbert vs. SandiganbayanRenceNo ratings yet

- A007 Acts of LascivousnessDocument28 pagesA007 Acts of LascivousnessLeolaida AragonNo ratings yet

- Mock TrialDocument6 pagesMock TrialtatskoplingNo ratings yet

- G.R. Nos. 138874-75 - 03feb2004 (Chiong Case)Document35 pagesG.R. Nos. 138874-75 - 03feb2004 (Chiong Case)Donald Dwane Reyes100% (3)

- Sibulo Vs Toledo MupasDocument5 pagesSibulo Vs Toledo Mupas1222No ratings yet

- Esmael Orquinaza Vs PeopleDocument5 pagesEsmael Orquinaza Vs PeopleAnonymous oDPxEkdNo ratings yet

- Case Detail - Public - Broward County Clerk of CourtsDocument12 pagesCase Detail - Public - Broward County Clerk of CourtsRamenth100% (1)

- Aguinaldo Vs Ventus PDFDocument19 pagesAguinaldo Vs Ventus PDFAnonymous F8TfwgnhNo ratings yet

- Special Penal LawsDocument36 pagesSpecial Penal LawsmaryanneNo ratings yet

- Cudia Vs CADocument2 pagesCudia Vs CARei MarchNo ratings yet

- People V GapasinDocument4 pagesPeople V GapasinmarkNo ratings yet

- Estipona, Jr. vs. LobrigoDocument33 pagesEstipona, Jr. vs. Lobrigokrissa_omandamNo ratings yet

- York County Court Schedule For Feb. 24Document17 pagesYork County Court Schedule For Feb. 24York Daily Record/Sunday NewsNo ratings yet

- People Vs de Grano PDFDocument23 pagesPeople Vs de Grano PDFEnzoNo ratings yet

- Marcos V Ruiz, G.R. No. 70746-47, Sept 1, 1992Document8 pagesMarcos V Ruiz, G.R. No. 70746-47, Sept 1, 1992Sarah Jane-Shae O. SemblanteNo ratings yet

- AM No. 03-1-09-SCDocument5 pagesAM No. 03-1-09-SCmatinikkiNo ratings yet

- Cases On PD 705Document38 pagesCases On PD 705johnlee rumusudNo ratings yet

- Tagapan Cicl PDFDocument255 pagesTagapan Cicl PDFMasacal Suhaib MosaNo ratings yet

Safari - Jan 12, 2024 at 11:54 AM

Safari - Jan 12, 2024 at 11:54 AM

Uploaded by

pjpmzd6b9cOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Safari - Jan 12, 2024 at 11:54 AM

Safari - Jan 12, 2024 at 11:54 AM

Uploaded by

pjpmzd6b9cCopyright:

Available Formats

G.R. No.

187000

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 187000 November 24, 2014

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Petitioner,

vs.

AQUILINO ANDRADE, ROMAN LACAP, YONG FUNG YUEN, RICKY YU,

VICENTE SY, ALVIN SO, ROMUALDO MIRANDA, SINDAO MELIBAS,

SATURNINO LIWANAG, ROBERTO MEDINA and RAMON NAVARRO,

Respondents.

DECISION

PERALTA, J.:

It is clearly provided by the Rules of Criminal Procedure that if the motion to

quash is based on an alleged defect in the information which can be cured by

amendment, the court shall order the amendment to be made.

For this Court's consideration is the Petition for Review on Certiorari under

Rule 45 of the Rules of Court, which seeks to reverse and set aside the

Decision1 dated May 29, 2008 and Resolution2 dated February 26, 2009 of

the Court of Appeals (CA).

The antecedent facts are the following:

Pursuant to the instructions of then Director of the Bureau of Corrections,

Dionisio R. Santiago, on June 30, 2003, a random drug test was conducted in

the National Bilibid Prison (NBP) wherein the urine samples of thirty-eight

(38) inmates were collected and subjected to drug testing by the Chief

Medical Technologist and Assistant Medical Technologist of the Alpha

Polytechnic Laboratory in Quezon City, and out of that number, twenty-one

(21) urine samples tested positive.

After confirmatory tests doneby the NBI Forensic Chemistry Division, those

twenty-one (21) urine samples, which included that of herein respondents,

yielded positive results confirming the result of the initial screen test.

Necessarily, the twenty-one (21) inmates were charged with violation of

Section 15, Article II of Republic Act No. 9165 (RA 9165) under identical

Informations,3 which read as follows:

The undersigned State Prosecutor of the Department of Justice, accuses

AQUILINO ANDRADE for Violation of Section 15, Article II of R.A. 9165,

committed as follows:

That on or about June 30, 2003, in the New Bilibid Prisons, Muntinlupa City,

Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-

named accused, without having been authorized by law, did then and there

willfully, unlawfully, and feloniously use or in any manner introduced into the

physiological system of his body, Methamphetamine Hydrochloride,

otherwise known as "shabu," a dangerous drug inviolation of the aforecited

law.4

All respondents pleaded "Not Guilty" to the crime charged during their

arraignment on June 29, 2006. Thereafter, the case was set for pre-trial and

trial on August 11, 2006.5

On August 29, 2006, respondents filed a Consolidated Motion to Dismiss on

the ground that the facts alleged in the Information do not constitute a

violation of Section 15, RA 9165, which reads:

6. A strict reading of the provisions of Section 15, Article II, RA 9165

reveals that the accused did not commit the offense charged. Under RA

9165, the offense of Violation of Section 15 thereof is committed by a

person apprehended or arrested for using dangerous drug, and who is

found to be positive for use of any dangerous drug after a confirmatory

test, to wit:

xxxx

7. In the case at bar, the accused were never apprehended or arrested for

using a dangerous drug or for violating the provisions of RA 9165, which

would warrant drug testing and serve as basis for filing the proper

information in court. In fact, the accused were merely called to the

Maximum Security Conference Hall in the morning of June 30, 2003 and

with seventeen (17) other inmates made to undergo drug testing, pursuant

to the directive of then Sr. Usec. Santiago. It was only after they were

found positive for dangerous drugs that the information for Violation of

Section 15, RA 9165 was filed against each of them.

8. Section 36, Article III, RA 9165 further enumerates the persons subject

to mandatory and random drug tests, who if found positive after such drug

test shall be subject to the provisions of Section 15. x x x

xxxx

National penitentiary inmates or inmates of the Bureau of Corrections are

not included in the enumeration. Thus, even if the accused have been

found positive in the mandatory or random drug test conducted by

BUCOR, they cannot be held liable under Section 15.

9. Assuming for the sake of argument, but not admitting, that the accused

were apprehended or arrested for using a dangerous drug or for violating

the provisions of RA 9165 which led to the June 30, 2003 screen test, or

that the accused are subject to mandatory or random drug testing, the

drug test would be invalid absent a showing that the same was conducted

within twenty-four (24) hours after the apprehension or arrest of the

offender through a confirmatory test within fifteen (15) days receipt of the

result in accordance with the provisions of Section 38, Article II of RA 9165

x x x.

xxxx

10. In the case, the accused were not informed of the results of the

screening test, thus depriving them of the right to challenge the same

through a confirmatory drug test within the required fifteen (15)-day

period after receipt of the positive result.6

Respondents' lawyer, on the date set for hearing, manifested that he intends

to pursue the Motion to Dismiss filed by respondents' previous counsel,7

hence, the pre-trial and trial were reset to September 29, 2006.

The pre-trial and trial were further reset to November 29, 20068 due to a

typhoon that occurred on the earlier scheduled date.

The Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Muntinlupa, before the scheduled hearing

date for pre-trial and trial, issued an Order9 granting respondents'

Consolidated Motion to Dismiss,10 ruling as follows:

To be liable under this Act the following essential requisites must be present:

1. The offender must have been arrested or apprehended for use of

dangerous drugs; or apprehended or arrested for violation of RA 9165

and the apprehending or arresting officer has reasonable ground to

believe that the person arrested or apprehended on account of physical

signs or symptoms or other visible or outward manifestation is under the

influence of dangerous drugs; or must have been one of those under

Sec. 36 of Art. III of RA 9165 who should be subjected to undergo drug

testing;

2. The offender must have been found positive for use of dangerous drug

after a screening and confirmatory test;

3. The offender must not have been found in his/ or her possession such

quantity of dangerous drug provided for under Section 11 of this Act;

4. That if the offender arrested or apprehended has been found to be

positive for use of dangerous drugs after a screening laboratory

examination, the results of the screening laboratory examination of test

shall be challenged within fifteen (15) days after receipt of the result

through a confirmatory test conducted in any accredited analytical

laboratory equipment with a gas chromatograph/mass spectrometry or

some such modern method.

xxxx

It is clear from the foregoing facts that the inmates were not apprehended nor

arrested for violation of any provision of R.A. 9165. These inmates were in the

National Bilibid Prisons (NBP) serving sentences for different crimes which

may include also drug offenses. They were subjected to drug tests only

pursuant to the request made by then Director Dionisio Santiago.

Furthermore, they were not one of those persons enumerated in Section 36

of the said Act who may be subjected to mandatory drug testing. Hence, the

first essential requisite has not been complied with. If one essential requisiteis

absent, the Court believes that these inmates cannot be held liable for the

offense charged. They may be held liable administratively for violation of the

Bureau of Corrections or NBP rules and regulations governing demeanor of

inmates inside a penitentiary but not necessarily for violation of Sec. 15 of

R.A. 9165. The court need not discuss the other elements of the crime as the

same has become moot and academic in view of the absence of the first

essential element.

WHEREFORE, finding no probable cause for the offense charged in the

Information these cases are ordered DISMISSED with costs de officio.

SO ORDERED.11

Petitioner filed a Petition for Certiorari with the CA after its Motion for

Reconsideration was denied.

The CA, in its Decision dated May 29, 2008, affirmed the trial court's Order,

the fallo of which reads:

WHEREFORE, the instant petition for certiorari is DENIED. The assailed Orders

of the public respondent Regional Trial Court of Muntinlupa City, Branch 204,

in Criminal Cases Nos. 06-224, 06-229, 06-231, 06-232, 06-234, 06-235,

06-237, 06-238, 06-239 and 06-241, STAND.

SO ORDERED.12

Consequently, petitioner filed its Motion for Reconsideration, but was denied

in a Resolution dated February26, 2009. Thus, the present petition.

Petitioner asserts the following argument:

THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED WHEN IT HELD THAT PRIVATE

RESPONDENTS MAY NOT BE HELDLIABLE FOR VIOLATION OF SECTION 15,

ARTICLE II OF RA 9165.13 According to petitioner, the CA erred because

respondents had lost the remedy under Section 3(a), Rule 117 of the Rules of

Court having been already arraigned before availing of the said remedy.

Respondents, however, insist that the CA is correct in upholding the RTC's

decision dismissing the Informations filed against them. They claim that since

the ground they relied on is Section 3(a), Rule 117 of the Rules of Court, their

motion to quash may be filed even after they have entered their plea.

Basically, the issue presented before this Court is not so much as the

timeliness of the filing of the motion toquash, but whether the CA erred in

upholding the RTC's grant of respondents' motion and eventually dismissing

the case based on lack of probable cause.

This Court finds the present petition meritorious.

The ground relied upon by respondents in their "Motion to Dismiss," which is,

that the facts alleged in the Information do not constitute an offense, is

actually one of the grounds provided under a Motion to Quash in Section 3

(a),14 Rule 117 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure.

It must be emphasized that respondents herein filed their Motion after they

have been arraigned. Under ordinary circumstances, such motion may no

longer be allowed after arraignment because their failure to raise any ground

of a motion to quash before they plead is deemed a waiver of any of their

objections. Section 9, Rule 117 of the Rules of Court provides:

Sec. 9. Failure to Move to Quash or to Allege Any Ground Therefor. - The

failure of the accused to assert any ground of a motion to quash before he

pleads to the complaint or information, either because he did not file a motion

to quash or failed to allege the same in said motion, shall be deemed a waiver

of any objections except those based on the grounds provided for in

paragraphs (a),(b), (g), and (i) of Section 3 of this Rule.

However, since the ground asserted by respondents is one of the exceptions

provided under the above-provision, the timeliness of the filing is

inconsequential. The mistake lies inthe RTC's dismissal of the case.

The RTC judge went beyond her authority when she dismissed the cases

based on lack of probable cause and not on the ground raised by

respondents, to wit:

WHEREFORE, finding no probable cause for the offense charged in the

Informationthese cases are ordered DISMISSED with cost de officio.

SO ORDERED.15

Section 2,16 Rule 117 of the Revised Rules on Criminal Procedure plainly

states that in a motion to quash, the court shall not consider any ground other

than those stated in the motion, except lack of jurisdiction over the offense

charged. In the present case, what the respondents claim in their motion to

quash is that the facts alleged in the Informations do not constitute an

offense and not lack of probable cause as ruled by the RTC judge.

The RTC judge's determination of probable cause should have been only

limited prior to the issuance of a warrant of arrest and not after the

arraignment. Once the information has been filed, the judge shall then

"personally evaluate the resolution of the prosecutor and its supporting

evidence"17 to determine whether there is probable cause to issue a warrant

of arrest. At this stage, a judicial determination of probable cause exists.18

In People v. Castillo and Mejia,19 this Court has stated:

There are two kinds of determination of probable cause: executive and

judicial. The executive determination of probable cause is one made during

preliminary investigation. It is a function that properly pertains to the public

prosecutor who is given a broad discretion to determine whether probable

cause exists and to charge those whom he believes to have committed the

crime as defined by law and thus should be held for trial. Otherwise stated,

such official has the quasi-judicial authority to determine whether or not a

criminal case must be filed in court. Whether or not that function has been

correctly discharged by the public prosecutor, i.e.,whether or not he has

made a correct ascertainment of the existence of probable cause in a case, is

a matter that the trial court itself does not and may not be compelled to pass

upon.

The judicial determination of probable cause, on the other hand, is one made

by the judge to ascertain whether a warrant of arrest should be issued against

the accused. The judge must satisfy himself that based on the evidence

submitted, there is necessity for placing the accused under custody in order

not to frustrate the ends of justice. If the judge finds no probable cause, the

judge cannot be forced to issue the arrest warrant.20

The difference is clear: The executive determination of probable cause

concerns itself with whether there is enough evidence to support an

Information being filed. The judicial determination of probable cause, on the

other hand, determines whether a warrant of arrest should be issued. In

People v. Inting:21

x x x Judges and Prosecutors alike should distinguish the preliminary inquiry

which determines probable cause for the issuance of a warrant of arrest from

the preliminary investigation proper which ascertains whether the offender

should be held for trial or released. Even if the two inquiries are conducted in

the course of one and the same proceeding, there should be no confusion

about the objectives. The determination of probable cause for the warrant of

arrest is made by the Judge. The preliminary investigation proper – whether

or not there is reasonable ground to believe that the accused is guilty of the

offense charged and, therefore, whether or not he should be subjected to the

expense, rigors and embarrassment of trial – is the function of the

Prosecutor.22

While it is within the trial court’s discretion to make an independent

assessment of the evidence on hand, it isonly for the purpose of determining

whether a warrant of arrest should beissued. The judge does not act as an

appellate court of the prosecutor and has no capacity to review the

prosecutor’s determination of probable cause; rather, the judge makes a

determination of probable cause independent of the prosecutor’s finding.23

In truth, the court's duty in an appropriate case is confined merely to the

determination of whether the assailed executive or judicial determination of

probable cause was done without orin excess of jurisdiction or with grave

abuse of discretion amounting to want of jurisdiction.24 In this particular

case, by proceeding with the arraignment of respondents, there was already

an admittance that there is probable cause. Thus, the RTC should not have

ruled on whether or not there is probable cause to hold respondents liable for

the crime committed since its duty is limited only to the determination of

whether the material averments in the complaint or information are sufficient

to hold respondents for trial.1âwphi1none In fact, in their motion, respondents

claimed that the facts alleged in the Informations do not constitute an

offense.

Considering that the RTC has already found probable cause, it should have

denied the motion to quash and allowed the prosecution to present its

evidence and wait for a demurrer to evidence to be filed by respondents, if

they opt to, or allowed the prosecution to amend the Information and in the

meantime suspend the proceedings until the amendment of the Information

without dismissing the case.

Section 4, Rule 117 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure clearly states

that if the ground based upon is that "the facts charged do not constitute an

offense," the prosecution shall be given by the court an opportunity to correct

the defect by amendment, thus:

Section 4. Amendment of the complaint or information. - If the motion to

quash is based on an alleged defect of the complaint or information which

can be cured by amendment, the court shall order that an amendment be

made.

If it is based on the ground that the facts charged do not constitute an

offense, the prosecution shall be given by the court an opportunity to correct

the defect by amendment. The motion shall be granted if the prosecution fails

to make the amendment, or the complaint or information still suffers from the

same defect despite the amendment.25

If the defect in the information is curable by amendment, the motion to quash

shall be denied and the prosecution shall be ordered to file an amended

information.26 Generally, the fact that the allegations in the information do

not constitute an offense, or that the information does not conform

substantially to the prescribed form, are defects curable by amendment.27

Corollary to this rule, the court should give the prosecution an opportunity to

amend the information.28 In the present case, the RTC judge outrightly

dismissed the cases without giving the prosecution an opportunity to amend

the defect in the Informations. In People v. Talao Perez,29 this Court ruled

that, "...even granting that the information in question is defective, as pointed

out by the accused, it appearing that the defects thereof can be cured by

amendment, the lower court should not have dismissed the case but should

have ordered the Fiscal to amend the information." When there is any doubt

about the sufficiency of the complaint or information, the court should direct

its amendment or that a new information befiled, and save the necessity of

appealing the case on technical grounds when the complaint might easily be

amended.30

Even the CA admitted that the RTC erred in that regard, thus:

Indeed, Section 4, Rule 117 of the Rules of Court, requires that the

prosecution should first be given the opportunity to correct the defects in the

information before the courts may grant a motion to quash grounded on

Section 3(a), and it may only do so when the prosecution fails to make the

amendment, or the information suffers from the same defect despite the

amendment. Pursuant to this rule, it would thus seem that the trial court did

err in this regard.31

The CA, however, still upheld the ruling of the RTC, stating that "whatever

perceived error the trial court may have committed is inconsequential as any

intended amendment to the informations filed surely cannot cure the

defects,"32 and to justify such conclusion, the CA proceeded to decide the

merits of the case based merely on the allegations in the Information. Such

pronouncement, therefore, is speculative and premature without giving the

prosecution the opportunity to present its evidence or, to at least, amend the

Informations. In People v. Leviste,33 we stressed that the State, like any other

litigant, is entitled to its day in court; in criminal proceedings, the public

prosecutor acts for and represents the State, and carries the burden of

diligently pursuing the criminal prosecution in a manner consistent with public

interest.34 The prosecutor's role in the administration of justice is to lay

before the court, fairly and fully, every fact and circumstance known to him or

her to exist, without regard to whether such fact tends to establish the guilt or

innocence of the accused and without regard to any personal conviction or

presumption on what the judge may or is disposed to do.35 The prosecutor

owes the State, the court and the accused the duty to lay before the court the

pertinent facts at his disposal with methodical and meticulous attention,

clarifying contradictions and filling up gaps and loopholes in his evidence

tothe end that the court's mind may not be tortured by doubts; that the

innocent may not suffer; and that the guilty may not escape unpunished.36 In

the conduct of the criminal proceedings, the prosecutor has ample

discretionary power to control the conduct of the presentation of the

prosecution evidence, part of which is the option to choose what evidence to

present or who to call as witness.37 Thus, the RTC and the CA, by not giving

the State the opportunity to present its evidence in court or to amend the

Informations, have effectively curtailed the State's right to due process.

IN LIGHT OF THE FOREGOING, the present Petition for Review on Certiorari is

hereby GRANTED. The Decision dated May 29, 2008 and Resolution dated

February 26, 2009 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 100016 are

hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE.

SO ORDERED.

DIOSDADO M. PERALTA

Associate Justice

WE CONCUR:

PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, JR.

Associate Justice

Chairperson

MARTIN S. VILLARAMA, JR. JOSE CATRAL MENDOZA*

Associate Justice Associate Justice

FRANCIS H. JARDELEZA

Associate Justice

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in

consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of tye opinion of the

Court's Division.

PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, JR.

Associate Justice

Chairperson, Third Division

CERTIFICATION

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution and the Division

Chairperson's Attestation, I certify that the conclusions in the above Decision

had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned to the writer

of the opinion of the Court's Division.

MARIA LOURDES P.A. SERENO

Chief Justice

Footnotes

* Designated Acting Member in lieu of Associate Justice Bienvenido L.

Reyes, per Special Order No. 1878, dated November 21, 2014.

1 Penned by Associate Justice Mariflor P. Punzalan Castillo, with

Associate Justices Rodrigo V. Cosico and Hakim S. Abdulwahid,

concurring; rollo, pp. 28-42.

2 Id. at 43-45.

3 Records, pp. 5-6.

4 Id. at 5.

5 Id. at 79.

6 Id. at 107-109.

7 Id. at 90.

8 Id. at 121.

9 Id. at 133-137; per Presiding Judge Juanita T. Guerrero.

10 Id. at 138-139.

11 Id. at 136-137.

12 Rollo, p. 41. (Emphasis in the original)

13 Id. at 17.

14 Sec. 3. Grounds. - The accused may move to quash the complaint or

information on any of the following grounds:

(a) That the facts charged do not constitute an offense;

(b) That the court trying the case has no jurisdiction over the

offense charged;

(c) That the court trying the case has nojurisdiction over the person

of the accused;

(d) That the officer who filed the information had no authority to do

so;

(e) That it does not conform substantially to the prescribed form;

(f) That more than one offense is charged except when a single

punishment for various offenses is prescribed by law;

(g) That the criminal action or liability has been extinguished;

(h) That it contains averments which, if true, would constitute a legal

excuse or justification; and (i) That the accused has been previously

convicted or acquitted of the offense charged, or the case against

him was dismissed or otherwise terminated without his express

consent. (Emphasis supplied)

15 Emphasis supplied.

16 Section 2. Form and contents. - The motion to quash shall be in

writing, signed by the accused or his counsel, and shall distinctly specify

its factual and legal grounds. The court shall consider no grounds other

than those stated in the motion, except lack of jurisdiction over the

offense charged. (Emphasis supplied)

17 Rules on Criminal Procedure, Rule 112, Sec. 6.

18 Alfredo C. Mendoza v. People of the Philippines, et al., G.R. No.

197293, April 21, 2014.

19 Id., citing 607 Phil. 754 (2009) [Per J. Quisumbing, Second Division].

20 Id., at 764-765, citing Paderanga v. Drilon, 273 Phil. 290, 296 (1991)

[Per J. Regalado, En Banc]; Roberts, Jr. v. Court of Appeals,324 Phil. 568,

620-621 (1996) [Per J. Davide, Jr., En Banc]; Ho v. People, 345 Phil. 597,

611 (1997) [Per J. Panganiban, En Banc].

21 G.R. No. 88919, July 25, 1990, 187 SCRA 788 [Per J. Gutierrez, Jr., En

Banc].

:

You might also like

- Rule 115 - Rules of CourtDocument6 pagesRule 115 - Rules of CourtMigoy DA100% (1)

- Churchille Mari vs. Gonzales - DigestDocument4 pagesChurchille Mari vs. Gonzales - DigestDudly Rios67% (3)

- 3 - People vs. Andrade, G.R. No. 187000, November 24, 2014Document7 pages3 - People vs. Andrade, G.R. No. 187000, November 24, 2014Michelle CatadmanNo ratings yet

- 3 People V AndradeDocument9 pages3 People V AndradeFrances Angelica Domini KoNo ratings yet

- MTQ 3Document10 pagesMTQ 3naxreal24No ratings yet

- CRIM PRO - Cases.F1Document11 pagesCRIM PRO - Cases.F1Jessie May Althea VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- People v. AndradeDocument4 pagesPeople v. AndradeBrian Kelvin PinedaNo ratings yet

- CASE POOL Crim 2 Cases Atty. Suyat Syllabus PDFDocument142 pagesCASE POOL Crim 2 Cases Atty. Suyat Syllabus PDFMheryza De Castro PabustanNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz vs. PeopleDocument3 pagesDela Cruz vs. PeopleShery Ann ContadoNo ratings yet

- WEEK 6 - No. 1 Failure To Move Quash or To Allege Any Ground Thereof (People Vs Andrade)Document1 pageWEEK 6 - No. 1 Failure To Move Quash or To Allege Any Ground Thereof (People Vs Andrade)saripmohan03No ratings yet

- Application For BailDocument6 pagesApplication For BailgeorgecloneyNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz V PEOPLEDocument10 pagesDela Cruz V PEOPLEMp CasNo ratings yet

- What Is Confirmatory Test in Drugs CasesDocument2 pagesWhat Is Confirmatory Test in Drugs CasesRoberto Rivero IIINo ratings yet

- 4 de La Cruz Vs People (SI-Drugtest On Accused Not Charged Under RA9165)Document9 pages4 de La Cruz Vs People (SI-Drugtest On Accused Not Charged Under RA9165)Avatar09No ratings yet

- De La Cruz vs. People of The Philippines - Special Penal LawsDocument2 pagesDe La Cruz vs. People of The Philippines - Special Penal Lawsحنينة جماءيلNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE vs. SullanoDocument2 pagesPEOPLE vs. SullanoTrishaNo ratings yet

- People Vs SullanoDocument6 pagesPeople Vs Sullanomaricar bernardinoNo ratings yet

- Dismissed Drug CasesDocument71 pagesDismissed Drug CasesErnesto AbesamisNo ratings yet

- Vaporo and Tulilik Case - Illegal Search - Two Searches ConductedDocument6 pagesVaporo and Tulilik Case - Illegal Search - Two Searches ConductedRothea SimonNo ratings yet

- GR No 227394Document12 pagesGR No 227394russelsithliNo ratings yet

- JAIME D. DELA CRUZ, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines, RespondentDocument8 pagesJAIME D. DELA CRUZ, Petitioner, vs. People of The Philippines, RespondentredlacsonNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz vs. PeopleDocument7 pagesDela Cruz vs. PeopleJade QSNo ratings yet

- Social Justice Society v. Dangerous Drugs BoardDocument16 pagesSocial Justice Society v. Dangerous Drugs Boardred gynNo ratings yet

- Jaime Dela Cruz v. PeopleDocument13 pagesJaime Dela Cruz v. PeopleCourtney TirolNo ratings yet

- Vaporoso v. People of The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesVaporoso v. People of The Philippinessuis generisNo ratings yet

- Dela CruzDocument10 pagesDela CruzjoNo ratings yet

- Chain of CustodyDocument8 pagesChain of CustodyKuya Kim100% (1)

- People vs. ManlangitDocument10 pagesPeople vs. ManlangitMrChips JayNo ratings yet

- Article 80-113Document55 pagesArticle 80-113Sweet jenesie MirandaNo ratings yet

- (As Modified by RA 10640) : "Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002"Document41 pages(As Modified by RA 10640) : "Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002"Peter ManuelNo ratings yet

- 2014) Laid Down The Links That Must Be Established in The Chain of Custody, To Wit: "First, The SeizureDocument6 pages2014) Laid Down The Links That Must Be Established in The Chain of Custody, To Wit: "First, The Seizuredeuce scriNo ratings yet

- Sec 15 Acquitted - Not Arrested But Subjected To Mandatory Drug TestingDocument21 pagesSec 15 Acquitted - Not Arrested But Subjected To Mandatory Drug TestingCon QuerorNo ratings yet

- 007 Dela Cruz vs. PeopleDocument8 pages007 Dela Cruz vs. Peoplest3ll4_my8No ratings yet

- People vs. ManlangitDocument8 pagesPeople vs. ManlangitGEiA Dr.No ratings yet

- Demurrer 2Document8 pagesDemurrer 2Janus Mari AbanNo ratings yet

- First G.R. No. People of Siu Ming Tat And: VersusDocument3 pagesFirst G.R. No. People of Siu Ming Tat And: VersusJohannes YapyapanNo ratings yet

- RA 9165 SPL SummaryDocument4 pagesRA 9165 SPL SummaryRay Lambert Menchavez100% (1)

- Estipona v. Hon Lobrigo - OdtDocument15 pagesEstipona v. Hon Lobrigo - OdtDayanski B-mNo ratings yet

- Nisperos y Padilla v. PeopleDocument46 pagesNisperos y Padilla v. Peoplezedric santosNo ratings yet

- A. People Vs Sullano, GR No. 228373 Dated March 12, 2018Document11 pagesA. People Vs Sullano, GR No. 228373 Dated March 12, 2018Princess Marjorie RebutNo ratings yet

- Digest - SJS Vs Dangerous Drugs BoardDocument4 pagesDigest - SJS Vs Dangerous Drugs BoardRosemary Red100% (1)

- Dela Cruz V PeopleDocument2 pagesDela Cruz V PeopleMaureen CoNo ratings yet

- Plea Bargain OrderDocument3 pagesPlea Bargain OrderitssaabNo ratings yet

- Iii. Tumabini v. People, G.R. No. 224495, February 19, 2020Document3 pagesIii. Tumabini v. People, G.R. No. 224495, February 19, 2020Dan K100% (1)

- Illegal Drugs CasesDocument23 pagesIllegal Drugs CasesmimslawNo ratings yet

- Chain of Custody RuleDocument39 pagesChain of Custody RuleRLO1100% (2)

- People v. GuanzonDocument10 pagesPeople v. Guanzonsuperwezowski7No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 217097 - Search and SEizuresDocument10 pagesG.R. No. 217097 - Search and SEizuresSANDRA MAE BONRUSTRONo ratings yet

- Judgment On Lauta Drug CaseDocument6 pagesJudgment On Lauta Drug CaseLahnee F. MagatNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines V Angel Angeles y ArimbuyutanDocument2 pagesPeople of The Philippines V Angel Angeles y ArimbuyutanErneylou RanayNo ratings yet

- Drugs CasesDocument4 pagesDrugs CasesrobelinNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument19 pagesCase DigestEsto, Cassandra Jill SumalbagNo ratings yet

- Tumabini Vs PeopleDocument7 pagesTumabini Vs PeopleAthea Justine YuNo ratings yet

- People v. AndradeDocument2 pagesPeople v. AndradejasminealmiraNo ratings yet

- Santos vs. People (Full Text, Word Version)Document11 pagesSantos vs. People (Full Text, Word Version)Emir Mendoza100% (1)

- Drugs DigestDocument4 pagesDrugs DigestjasminezeroNo ratings yet

- Latest Juris Drugs 3 2020Document8 pagesLatest Juris Drugs 3 2020dyosaNo ratings yet

- ALCALA, Sheena Mae - 1st DraftDocument6 pagesALCALA, Sheena Mae - 1st Draftdwight yuNo ratings yet

- People vs. SanchezDocument5 pagesPeople vs. SanchezmNo ratings yet

- The Nuremberg Trials: Complete Tribunal Proceedings (V. 2): Trial Proceedings From Preliminary Hearing Held on 14 November 1945 to 30 November 1945From EverandThe Nuremberg Trials: Complete Tribunal Proceedings (V. 2): Trial Proceedings From Preliminary Hearing Held on 14 November 1945 to 30 November 1945No ratings yet

- The Nuremberg Trials (V. 2): Trial Proceedings From Preliminary Hearing Held on 14 November 1945 to 30 November 1945From EverandThe Nuremberg Trials (V. 2): Trial Proceedings From Preliminary Hearing Held on 14 November 1945 to 30 November 1945No ratings yet

- 1 People Vs Goce, 247 SCRA 780 (1995)Document6 pages1 People Vs Goce, 247 SCRA 780 (1995)Perry YapNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Q and A 21Document204 pagesCriminal Procedure Q and A 21Mary Jane GarinNo ratings yet

- Chelsea Cook Domestic Violence/Assault Charges in Front of ChildrenDocument3 pagesChelsea Cook Domestic Violence/Assault Charges in Front of ChildrenAdam ForgieNo ratings yet

- UNITED STATES of America Ex Rel. Frank PHELAN, Appellant, v. Joseph R. BRIERLEY, Warden, State Correctional Institution, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaDocument42 pagesUNITED STATES of America Ex Rel. Frank PHELAN, Appellant, v. Joseph R. BRIERLEY, Warden, State Correctional Institution, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents Leodegario A Barayang, SR: First DivisionDocument4 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents Leodegario A Barayang, SR: First DivisionIrish Joi TapalesNo ratings yet

- 2 Heirs of Honrales V HonralesDocument8 pages2 Heirs of Honrales V HonralesFrances Angelica Domini KoNo ratings yet

- Crim Pro FinalsDocument12 pagesCrim Pro FinalsAxel FontanillaNo ratings yet

- BAR QnADocument107 pagesBAR QnAJune Vincent Ferrer III50% (2)

- Bayani Subido JR Vs Sandiganbayan Et AlDocument5 pagesBayani Subido JR Vs Sandiganbayan Et AlJoshua Janine LugtuNo ratings yet

- CrimProc 1 25Document27 pagesCrimProc 1 25Rogelio A.C Jr.No ratings yet

- Albert vs. SandiganbayanDocument6 pagesAlbert vs. SandiganbayanRenceNo ratings yet

- A007 Acts of LascivousnessDocument28 pagesA007 Acts of LascivousnessLeolaida AragonNo ratings yet

- Mock TrialDocument6 pagesMock TrialtatskoplingNo ratings yet

- G.R. Nos. 138874-75 - 03feb2004 (Chiong Case)Document35 pagesG.R. Nos. 138874-75 - 03feb2004 (Chiong Case)Donald Dwane Reyes100% (3)

- Sibulo Vs Toledo MupasDocument5 pagesSibulo Vs Toledo Mupas1222No ratings yet

- Esmael Orquinaza Vs PeopleDocument5 pagesEsmael Orquinaza Vs PeopleAnonymous oDPxEkdNo ratings yet

- Case Detail - Public - Broward County Clerk of CourtsDocument12 pagesCase Detail - Public - Broward County Clerk of CourtsRamenth100% (1)

- Aguinaldo Vs Ventus PDFDocument19 pagesAguinaldo Vs Ventus PDFAnonymous F8TfwgnhNo ratings yet

- Special Penal LawsDocument36 pagesSpecial Penal LawsmaryanneNo ratings yet

- Cudia Vs CADocument2 pagesCudia Vs CARei MarchNo ratings yet

- People V GapasinDocument4 pagesPeople V GapasinmarkNo ratings yet

- Estipona, Jr. vs. LobrigoDocument33 pagesEstipona, Jr. vs. Lobrigokrissa_omandamNo ratings yet

- York County Court Schedule For Feb. 24Document17 pagesYork County Court Schedule For Feb. 24York Daily Record/Sunday NewsNo ratings yet

- People Vs de Grano PDFDocument23 pagesPeople Vs de Grano PDFEnzoNo ratings yet

- Marcos V Ruiz, G.R. No. 70746-47, Sept 1, 1992Document8 pagesMarcos V Ruiz, G.R. No. 70746-47, Sept 1, 1992Sarah Jane-Shae O. SemblanteNo ratings yet

- AM No. 03-1-09-SCDocument5 pagesAM No. 03-1-09-SCmatinikkiNo ratings yet

- Cases On PD 705Document38 pagesCases On PD 705johnlee rumusudNo ratings yet

- Tagapan Cicl PDFDocument255 pagesTagapan Cicl PDFMasacal Suhaib MosaNo ratings yet