Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 viewsNLR V 01 SINCLAIR v. RAMASAMI KANKANI

NLR V 01 SINCLAIR v. RAMASAMI KANKANI

Uploaded by

FelicianFernandopulle1) The accused, a head kankani (labor contractor), took a loan of Rs. 1,000 from the complainant employer to clear debts and bring more laborers to the estate.

2) There was an agreement that the loan could be repaid from wages earned, but wages for November were not fully paid within 60 days as required by law.

3) The court found that the loan did not qualify as an "advance" against wages under the labor ordinance, and the agreement did not make the kankani criminally liable if he otherwise was not. The accused was acquitted and discharged.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- RDC Hiring TestDocument5 pagesRDC Hiring TestPranitNo ratings yet

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Dishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintFrom EverandDishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Pre Trial BriefDocument10 pagesPre Trial BriefDiosa Mae Sarillosa0% (1)

- Legal Memorandum KceditedDocument8 pagesLegal Memorandum KceditedCnfsr KayceNo ratings yet

- Angel Jose Warehousing CoDocument4 pagesAngel Jose Warehousing CoChristiane Marie BajadaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest CreditDocument9 pagesCase Digest CreditCrestu JinNo ratings yet

- Civil Case 2Document8 pagesCivil Case 2fayeNo ratings yet

- PAL ESLA V NLRCDocument16 pagesPAL ESLA V NLRCJanelle Leano MarianoNo ratings yet

- Obli Con - Article 1169Document23 pagesObli Con - Article 1169Manilyn Beronia Pascioles0% (1)

- 2 - Magdalena Estates Inc Vs RodriguezDocument3 pages2 - Magdalena Estates Inc Vs RodriguezLariza Aidie100% (1)

- Republic of The Philippines Vs Sps Arturo and Laura SupanganDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Vs Sps Arturo and Laura SupanganJaimie Lyn TanNo ratings yet

- Sanchez Vs Harry Lyons ConstructionDocument4 pagesSanchez Vs Harry Lyons ConstructionJacquelyn AlegriaNo ratings yet

- Doctrines CasesDocument16 pagesDoctrines CasesIndira PrabhakerNo ratings yet

- Hermojina Estores Vs Sps. SupanganDocument4 pagesHermojina Estores Vs Sps. SupanganJomarco SantosNo ratings yet

- Angel Warehouse vs. CheldaDocument4 pagesAngel Warehouse vs. CheldaRey Victor GarinNo ratings yet

- What Is Quasi ContractDocument14 pagesWhat Is Quasi Contractchirayu goyalNo ratings yet

- What Is Quasi ContractDocument14 pagesWhat Is Quasi Contractchirayu goyalNo ratings yet

- Decision BENGZON, J.P., J.Document7 pagesDecision BENGZON, J.P., J.Glesa SalienteNo ratings yet

- 53 Angel Jose Warehousing V Chelda EnterprisesDocument6 pages53 Angel Jose Warehousing V Chelda Enterprisesjuan aldabaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-25704 April 24, 1968 ANGEL JOSE WAREHOUSING CO., INC., Plaintiff-Appellee, CHELDA ENTERPRISES and DAVID SYJUECO, Defendants-AppellantsDocument18 pagesG.R. No. L-25704 April 24, 1968 ANGEL JOSE WAREHOUSING CO., INC., Plaintiff-Appellee, CHELDA ENTERPRISES and DAVID SYJUECO, Defendants-AppellantsQhryszxianniech SaiburNo ratings yet

- Nego 10th To 11thDocument21 pagesNego 10th To 11thElyn ApiadoNo ratings yet

- Susana Glaraga Vs Sun LifeDocument4 pagesSusana Glaraga Vs Sun Lifecrisanto perezNo ratings yet

- TortDocument19 pagesTortLays RdsNo ratings yet

- CASE #1:: Cralaw Virtua1aw LibraryDocument34 pagesCASE #1:: Cralaw Virtua1aw LibraryNaoimi LeañoNo ratings yet

- 1169Document58 pages1169Manilyn Beronia Pascioles0% (1)

- Magdalena Estates vs. RodriguezDocument3 pagesMagdalena Estates vs. RodriguezJaysonNo ratings yet

- Angel Jose V Chelda 1968Document9 pagesAngel Jose V Chelda 1968Dindo EpinoNo ratings yet

- Crismina Garments Vs CADocument2 pagesCrismina Garments Vs CAJude ChicanoNo ratings yet

- Proper Application of Interest Rate - Estores vs. SupanganDocument3 pagesProper Application of Interest Rate - Estores vs. SupanganRommel P. AbasNo ratings yet

- 04-46 Angel Jose Warehousing v. Chelda EnterprisesDocument4 pages04-46 Angel Jose Warehousing v. Chelda EnterprisesGene Charles MagistradoNo ratings yet

- Herrera Vs Petrophil CorpDocument5 pagesHerrera Vs Petrophil CorpJohn AysonNo ratings yet

- ObliCon CH 3 Pt1 Full CasesDocument111 pagesObliCon CH 3 Pt1 Full CasesLiaa AquinoNo ratings yet

- 1.cebu International V. Ca 316 SCRA 488Document9 pages1.cebu International V. Ca 316 SCRA 488Rhena SaranzaNo ratings yet

- Legal Memo - Collection of Sum of MoneyDocument9 pagesLegal Memo - Collection of Sum of MoneyArnold Cavalida Bucoy100% (3)

- MANILA-BANKING-V-TEODORO DigestDocument4 pagesMANILA-BANKING-V-TEODORO DigestLau NunezNo ratings yet

- Amrit Lal Goverdhan Lalan Vs State Bank of TravancoreDocument9 pagesAmrit Lal Goverdhan Lalan Vs State Bank of TravancoreEbadur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Villaroel vs. EstradaDocument9 pagesVillaroel vs. EstradaMitchayNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellant vs. vs. Defendant-Appellee Gerardo P. Moreno, Jr. N. O. BuenoDocument8 pagesPlaintiff-Appellant vs. vs. Defendant-Appellee Gerardo P. Moreno, Jr. N. O. BuenoGabe BedanaNo ratings yet

- Odiamar vs. ValenciaDocument2 pagesOdiamar vs. Valenciazandree burgos100% (1)

- Liam Law v. Olympic Sawmill Co., G.R. L-30771 (Usury Law Is For Some Time NowDocument2 pagesLiam Law v. Olympic Sawmill Co., G.R. L-30771 (Usury Law Is For Some Time Nowavelim44No ratings yet

- Oblicon QuestionsDocument3 pagesOblicon QuestionsDanNo ratings yet

- Oblicon DoctrineDocument73 pagesOblicon Doctrineleziel.santosNo ratings yet

- University School of Law and Legal Studies, GgsipuDocument7 pagesUniversity School of Law and Legal Studies, GgsipuAnand mishraNo ratings yet

- Group 1 ReportingDocument12 pagesGroup 1 ReportingPrincess ParasNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-28569. February 27, 1970 J. M. TUASON & Co. INC., Plaintiff-Appellant, v. LIGAYA JAVIER, Defendant-AppelleeDocument23 pagesG.R. No. L-28569. February 27, 1970 J. M. TUASON & Co. INC., Plaintiff-Appellant, v. LIGAYA JAVIER, Defendant-AppelleeKristin C. Peña-San FernandoNo ratings yet

- Jan 15 2019 Compiled Cases, UnfinishedDocument13 pagesJan 15 2019 Compiled Cases, Unfinishedjimmy100% (1)

- Dario Nacar Vs Gallery FramesDocument2 pagesDario Nacar Vs Gallery FramesJerald ParasNo ratings yet

- The Contract Act: Law, BC & Ethics - Newly Added Questions in Latest Practice Manual (April 2016)Document20 pagesThe Contract Act: Law, BC & Ethics - Newly Added Questions in Latest Practice Manual (April 2016)Vasanth KumarNo ratings yet

- Law Cases Batch 2Document27 pagesLaw Cases Batch 2SofiaNo ratings yet

- Quasi ContractDocument17 pagesQuasi ContractGenesia Pereira100% (2)

- 6.quiamco vs. Capital InsuranceDocument4 pages6.quiamco vs. Capital InsuranceBasmuthNo ratings yet

- Full Case Piczon Vs PiczonDocument2 pagesFull Case Piczon Vs PiczonYanaglyzzaNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. Grisaldo Whether The Loss of Chattel Mrotgage Extinguishes The ObligationDocument4 pagesRepublic vs. Grisaldo Whether The Loss of Chattel Mrotgage Extinguishes The ObligationGerald Bowe ResuelloNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument4 pagesCase DigestEugene Albert Olarte JavillonarNo ratings yet

- GR 130994Document9 pagesGR 130994Seventeen 17No ratings yet

- With A Period-Extinguishments CASESDocument7 pagesWith A Period-Extinguishments CASESMelanie Graile TumaydanNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument5 pagesCase AnalysisrhobiecorboNo ratings yet

- CT CasesDocument13 pagesCT CasesMique VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Credit 1st SetDocument8 pagesCredit 1st SetRhena SaranzaNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Labor Contract Law of the People's Republic of China (2007)From EverandLabor Contract Law of the People's Republic of China (2007)No ratings yet

- Alexander V Railway Executive - (1951) 2 AllDocument7 pagesAlexander V Railway Executive - (1951) 2 AllFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Note Mercantile Credit Co LTD V Hamblin - (Document1 pageNote Mercantile Credit Co LTD V Hamblin - (FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Farnworth Finance Facilities LTD V Attryde ADocument6 pagesFarnworth Finance Facilities LTD V Attryde AFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Parliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaDocument5 pagesParliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Frederick E Rose (London) LTD V WM H Pim, JuDocument11 pagesFrederick E Rose (London) LTD V WM H Pim, JuFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain V BoDocument4 pagesPharmaceutical Society of Great Britain V BoFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 20 of 2014Document12 pages20 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Chapelton V Barry Urban District Council - (Document6 pagesChapelton V Barry Urban District Council - (FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 32 of 2014Document11 pages32 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- A Roberts & Co LTD and Another V LeicestershDocument9 pagesA Roberts & Co LTD and Another V LeicestershFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction 8th Amendment 2137 40Document2 pagesJurisdiction 8th Amendment 2137 40FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 085 NLR NLR V 04 He Estate of Margaret WernhamDocument6 pages085 NLR NLR V 04 He Estate of Margaret WernhamFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Y%S, XLD M Dka %SL Iudcjd Ckrcfha .Eiü M %H: The Gazette of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaDocument2 pagesY%S, XLD M Dka %SL Iudcjd Ckrcfha .Eiü M %H: The Gazette of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 25 of 2011Document9 pages25 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 17 of 2014Document8 pages17 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 12 of 2011Document3 pages12 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 46 of 2007Document3 pages46 of 2007FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 29 of 2011Document6 pages29 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 04 of 2014Document11 pages04 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 18 of 2014Document3 pages18 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Parliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaDocument10 pagesParliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 15 of 2014Document3 pages15 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 14 of 2014Document18 pages14 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 7 of 2011Document10 pages7 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 37 of 2011Document10 pages37 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 2 of 2011Document3 pages2 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Parliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaDocument8 pagesParliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 16 of 2011Document3 pages16 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 10 of 2007Document58 pages10 of 2007FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 26 of 2007Document19 pages26 of 2007FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- State of West Bengal: The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 1975 Crilj 1249Document14 pagesState of West Bengal: The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 1975 Crilj 1249Rupali RamtekeNo ratings yet

- TortsDocument44 pagesTortsajay narwalNo ratings yet

- Purisima vs. Ricafranca G.R. No. 237530 November 29 2021Document19 pagesPurisima vs. Ricafranca G.R. No. 237530 November 29 2021Rikki Marie PajaresNo ratings yet

- Souradeep Rakshit: SubjectDocument15 pagesSouradeep Rakshit: SubjectSaif AliNo ratings yet

- Custodial Investigation Section 12. (1) Any Person Under Investigation For The Commission of AnDocument5 pagesCustodial Investigation Section 12. (1) Any Person Under Investigation For The Commission of AnBananaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Masipil, GR No. 85177Document8 pagesPeople vs. Masipil, GR No. 85177G-ONE PAISONESNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 248202Document11 pagesG.R. No. 248202Moyna Ferina RafananNo ratings yet

- Unified Maine Common Law Grand Jury: Lex Naturales Dei GratiaDocument3 pagesUnified Maine Common Law Grand Jury: Lex Naturales Dei GratiaLEBJ100% (1)

- Tierzah Mapson IndictmentDocument18 pagesTierzah Mapson IndictmentNational Content DeskNo ratings yet

- Travel-On v. CA / PP v. ManiegoDocument2 pagesTravel-On v. CA / PP v. ManiegolchieSNo ratings yet

- 12/04/19 - Gideon's Army Weekly Conference Call Saturday 9 Am CST For American Political PrisonersDocument26 pages12/04/19 - Gideon's Army Weekly Conference Call Saturday 9 Am CST For American Political PrisonersLoneStar1776No ratings yet

- Reportable: Bhagwan Singh ..... Appellants(s) Versus State of Uttarakhand ..... Respondents(s)Document11 pagesReportable: Bhagwan Singh ..... Appellants(s) Versus State of Uttarakhand ..... Respondents(s)Rudresh Shubham SinghNo ratings yet

- Cases - Quantum of EvidenceDocument13 pagesCases - Quantum of EvidenceCzarina CidNo ratings yet

- Tan Tek Beng Case - Legal EthicsDocument10 pagesTan Tek Beng Case - Legal EthicsShannin MaeNo ratings yet

- Case Digests2.1Document6 pagesCase Digests2.1Charlotte SagabaenNo ratings yet

- Foronda vs. Guerrero: FactsDocument23 pagesForonda vs. Guerrero: FactsErin GamerNo ratings yet

- Second Auburn Hospital LawsuitDocument18 pagesSecond Auburn Hospital LawsuitJames MulderNo ratings yet

- (Indispensable Party, Solidary Obligation) : G.R. No. 193753, September 26, 2012 Facts RulingDocument5 pages(Indispensable Party, Solidary Obligation) : G.R. No. 193753, September 26, 2012 Facts RulingAira GraileNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Injunction R58 Fulltext CasesDocument113 pagesPreliminary Injunction R58 Fulltext CasesAudreyNo ratings yet

- Right To Confront WitnessesDocument13 pagesRight To Confront WitnessesAlona Medalia Cadiz-GabejanNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 3962, February 10, 1908Document11 pagesG.R. No. 3962, February 10, 1908You EdgapNo ratings yet

- Sherrill v. Commandant, USDB, 10th Cir. (2004)Document5 pagesSherrill v. Commandant, USDB, 10th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 12th Quarterly Report For Oakland NSADocument85 pages12th Quarterly Report For Oakland NSAali_winstonNo ratings yet

- 51 Secretary of Justice vs. LantionDocument1 page51 Secretary of Justice vs. LantionNMNGNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Castro vs. Bustos FULL TEXTDocument6 pagesHeirs of Castro vs. Bustos FULL TEXTRuth Abigail R. Acero-FloresNo ratings yet

- US Vs PompeyaDocument8 pagesUS Vs PompeyaAlvin HalconNo ratings yet

NLR V 01 SINCLAIR v. RAMASAMI KANKANI

NLR V 01 SINCLAIR v. RAMASAMI KANKANI

Uploaded by

FelicianFernandopulle0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views3 pages1) The accused, a head kankani (labor contractor), took a loan of Rs. 1,000 from the complainant employer to clear debts and bring more laborers to the estate.

2) There was an agreement that the loan could be repaid from wages earned, but wages for November were not fully paid within 60 days as required by law.

3) The court found that the loan did not qualify as an "advance" against wages under the labor ordinance, and the agreement did not make the kankani criminally liable if he otherwise was not. The accused was acquitted and discharged.

Original Description:

Original Title

NLR-V-01-SINCLAIR-v.-RAMASAMI-KANKANI

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1) The accused, a head kankani (labor contractor), took a loan of Rs. 1,000 from the complainant employer to clear debts and bring more laborers to the estate.

2) There was an agreement that the loan could be repaid from wages earned, but wages for November were not fully paid within 60 days as required by law.

3) The court found that the loan did not qualify as an "advance" against wages under the labor ordinance, and the agreement did not make the kankani criminally liable if he otherwise was not. The accused was acquitted and discharged.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views3 pagesNLR V 01 SINCLAIR v. RAMASAMI KANKANI

NLR V 01 SINCLAIR v. RAMASAMI KANKANI

Uploaded by

FelicianFernandopulle1) The accused, a head kankani (labor contractor), took a loan of Rs. 1,000 from the complainant employer to clear debts and bring more laborers to the estate.

2) There was an agreement that the loan could be repaid from wages earned, but wages for November were not fully paid within 60 days as required by law.

3) The court found that the loan did not qualify as an "advance" against wages under the labor ordinance, and the agreement did not make the kankani criminally liable if he otherwise was not. The accused was acquitted and discharged.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 3

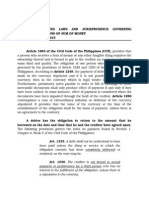

( 43 )

SINCLAIR v. RAMASAMI KAN KAN I.

P. (7., Hatton, 18,987.

Ordinances No. 11 of 1865, s. 11, and No. 15 of 1889, ss. 6 and 7—Loans to

kankani for procuring coolies—Agreement to repay such loans by

wages earned—Effect of such agreement on the criminal liability of the.

kankani under the Labour Ordinances—Meaning of " advances."

Loans made to an estate kankani f o r procuring coolies cannot be

debited t o him in the settlement o f wages due to him, as such loans are

n o t " advances " in the sense o f the t e r m explained in section 12 o f the

Ordinance N o . 13 o f 1889.

E v e n if there was an agreement between the labourer and his

e m p l o y e r that such loans should be set off against wages due, it cannot

have the effect o f making him criminally liable under the Ordinance if.

at the time o f quitting service, the m o n t h l y wages earned b y him shall

n o t have been paid in full within sixty days from the expiration o f the

month during which such wages have been earned.

HE facts of this case are fully stated in the judgment of the

Supreme Court.

Domhorst and Seneviratne, for the accused appellant.

Van Langenberg, for respondent.

Cut: adv. vult.

10th May, 1895. LAWRIE, J.—

The accused, a head kankani, who had a gang of coolies, took

service under the complainant in September, 1894, It is not said

on what estate he (the accused) and his coolies had formerly served,

but it is clear that they owed money, and that the complainant

advanced to the accused Rs. 1,000 to be paid to his creditors, to

enable him to clear accounts and to come to the estate. The

accused gave two promissory notes for these advances of Rs. 1,000.

After the accused and his coolies had been on the estate for

about two months and a half, the accused got a further advance

of Rs. 1,000 from the complainant for the purpose of procuring

and bringing to the estate some more coolies ; the accused

succeeded in getting more coolies, who joined his gang.

7-

( )

For this advance of Rs. 1,000 the accused gave a third promissory

note. There is evidence, which the Magistrate believed, that

after the first advances were made, and about the time the last

advance of Rs. 1,000 was paid, the complainant and the accused

arranged and agreed that " these loans and advances should be

" repaid in a special way, if the complainant should so desire, viz.,

" by accused's wages as earned being set against them as part pay-

" ment." On the 1st January, 1895, there was a pay day on the

estate, and the wages to the end of October were paid. I under

stand that the accused then received his wages in cash, and that

the agreement that the complainant might retain them in part

payment of the debt on the promissory notes was not taken

advantage of by him.

At the end of February the accused wished to leave the estate

with all his coolies; the complainant objected. On the 27th

February there was a meeting with a Proctor on behalf of the

head kankani, who made an offer to pay the Rs. 2,000, but that

offer was rejected by the complainant. The accused then left

the estate, but next day (28th February) he was tried in the

Hatton Police Court for the offence of quitting service without

leave or notice, and on the 22nd March he was found guilty

and sentenced to three months' rigorous imprisonment. Hence

this appeal.

The 7th section of Ordinance No. 13 of 1889, as amended by

section 2 of the Ordinance No. 7 of 1890, enacts that no labourer

shall be liable to punishment for quitting service without

leave or reasonable cause, if at the time of such alleged offence

the monthly wages earned by him shall not have been paid in

full within sixty days from the expiration of the month during

which such wages have been earned.

The 6th section enacts that, in computing the amount of wages

due to a labourer for any period of service, such labourer shall

be debited with the amount of all advances of money made to

him, and with the value of all food, clothes, or other articles

supplied to him during such period, which the employer is not

liable to supply at his own expense. The words " during such

period " are material; old advances may not be taken into con

sideration, only advances or supplies made within the period for

which wages are claimed and the subsequent sixty days. Here the

employer had paid Rs. 1,000 to the accused in December sub

sequent to the month of November for which the accused pleads

his wages were not paid. Was then the advance of Rs. 1,000 in

December an advance which can be computed in ascertaining

whether wages were due on the 27tb February ?

( *5 )

In endeavouring to fix the meaning of the words " all advances

of money " made to a labourer, I hold that an advance is different

from a loan. It is competent to turn to the 12th section of the

same Ordinance to see what there is meant by an advance: it there

means " money, food, clothes, or other articles which had been

" advanced or supplied to the labourer as against the wages for

" which he may be suing."

In Jacob's case (P. C , Kandy, 15,797, decided on 3rd August,

1893), my brother Withers said :—" My interpretation of the

" Labour Ordinance is that only advances by way of anticipated

" wages can be taken into account in computing what, if anything,

" is due to a labourer by way of wages earned by him at the date

"of hiB committing the offence of quitting service without leave."*

This is a direct authority which I with confidence follow, but

the complainant urges that by custom, and in this case by special

agreement, the advance of Rs. 1,000 made in December was an

advance to be repaid out of wages to be subsequently earned.

Whatever was formerly the effect of the customary understand

ing that large loans made to,a head kankani were to be repaid

out of wages, and that wages could legally be retained in payment

of old advances, I think that customary understanding was

corrected by the Ordinance I have quoted, which enacts that as a

set-off to wages shall only be put advances made against wages,

not (as I read the Ordinance) advances for bringing coolies and

the like.

The Magistrate rests his judgment indeed entirely on the special

agreement which he holds was made between the complainant

and the accused. It is not necessary to decide now what the effect

of that agreement would be in a civil case for wages. It surely

has no effect in a criminal case. If this kankani is not liable to

punishment under this Ordinance, he has not made himself

liable by this agreement criminally.

His wages for November were not paid to him ; more than sixty

days elapsed under the Ordinance ; he was not liable to punish

ment if he then left; he did not render himself liable to punish

ment because he agreed with his employer that he might retain

the wages in payment of a debt: that was an advantage to the

employer, which I assume the employer might gain by, but the

agreement cannot bring within the punitive clauses of the Labour

Ordinance a man who is not liable to punishment if he had not

made the agreement.

I am of opinion that the accused was wrongly convicted, and

that he is entitled to an acquittal«nd discharge.

* Ante, p . 42 of these report*.

You might also like

- RDC Hiring TestDocument5 pagesRDC Hiring TestPranitNo ratings yet

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Dishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintFrom EverandDishonour of Cheques in India: A Guide along with Model Drafts of Notices and ComplaintRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Pre Trial BriefDocument10 pagesPre Trial BriefDiosa Mae Sarillosa0% (1)

- Legal Memorandum KceditedDocument8 pagesLegal Memorandum KceditedCnfsr KayceNo ratings yet

- Angel Jose Warehousing CoDocument4 pagesAngel Jose Warehousing CoChristiane Marie BajadaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest CreditDocument9 pagesCase Digest CreditCrestu JinNo ratings yet

- Civil Case 2Document8 pagesCivil Case 2fayeNo ratings yet

- PAL ESLA V NLRCDocument16 pagesPAL ESLA V NLRCJanelle Leano MarianoNo ratings yet

- Obli Con - Article 1169Document23 pagesObli Con - Article 1169Manilyn Beronia Pascioles0% (1)

- 2 - Magdalena Estates Inc Vs RodriguezDocument3 pages2 - Magdalena Estates Inc Vs RodriguezLariza Aidie100% (1)

- Republic of The Philippines Vs Sps Arturo and Laura SupanganDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Vs Sps Arturo and Laura SupanganJaimie Lyn TanNo ratings yet

- Sanchez Vs Harry Lyons ConstructionDocument4 pagesSanchez Vs Harry Lyons ConstructionJacquelyn AlegriaNo ratings yet

- Doctrines CasesDocument16 pagesDoctrines CasesIndira PrabhakerNo ratings yet

- Hermojina Estores Vs Sps. SupanganDocument4 pagesHermojina Estores Vs Sps. SupanganJomarco SantosNo ratings yet

- Angel Warehouse vs. CheldaDocument4 pagesAngel Warehouse vs. CheldaRey Victor GarinNo ratings yet

- What Is Quasi ContractDocument14 pagesWhat Is Quasi Contractchirayu goyalNo ratings yet

- What Is Quasi ContractDocument14 pagesWhat Is Quasi Contractchirayu goyalNo ratings yet

- Decision BENGZON, J.P., J.Document7 pagesDecision BENGZON, J.P., J.Glesa SalienteNo ratings yet

- 53 Angel Jose Warehousing V Chelda EnterprisesDocument6 pages53 Angel Jose Warehousing V Chelda Enterprisesjuan aldabaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-25704 April 24, 1968 ANGEL JOSE WAREHOUSING CO., INC., Plaintiff-Appellee, CHELDA ENTERPRISES and DAVID SYJUECO, Defendants-AppellantsDocument18 pagesG.R. No. L-25704 April 24, 1968 ANGEL JOSE WAREHOUSING CO., INC., Plaintiff-Appellee, CHELDA ENTERPRISES and DAVID SYJUECO, Defendants-AppellantsQhryszxianniech SaiburNo ratings yet

- Nego 10th To 11thDocument21 pagesNego 10th To 11thElyn ApiadoNo ratings yet

- Susana Glaraga Vs Sun LifeDocument4 pagesSusana Glaraga Vs Sun Lifecrisanto perezNo ratings yet

- TortDocument19 pagesTortLays RdsNo ratings yet

- CASE #1:: Cralaw Virtua1aw LibraryDocument34 pagesCASE #1:: Cralaw Virtua1aw LibraryNaoimi LeañoNo ratings yet

- 1169Document58 pages1169Manilyn Beronia Pascioles0% (1)

- Magdalena Estates vs. RodriguezDocument3 pagesMagdalena Estates vs. RodriguezJaysonNo ratings yet

- Angel Jose V Chelda 1968Document9 pagesAngel Jose V Chelda 1968Dindo EpinoNo ratings yet

- Crismina Garments Vs CADocument2 pagesCrismina Garments Vs CAJude ChicanoNo ratings yet

- Proper Application of Interest Rate - Estores vs. SupanganDocument3 pagesProper Application of Interest Rate - Estores vs. SupanganRommel P. AbasNo ratings yet

- 04-46 Angel Jose Warehousing v. Chelda EnterprisesDocument4 pages04-46 Angel Jose Warehousing v. Chelda EnterprisesGene Charles MagistradoNo ratings yet

- Herrera Vs Petrophil CorpDocument5 pagesHerrera Vs Petrophil CorpJohn AysonNo ratings yet

- ObliCon CH 3 Pt1 Full CasesDocument111 pagesObliCon CH 3 Pt1 Full CasesLiaa AquinoNo ratings yet

- 1.cebu International V. Ca 316 SCRA 488Document9 pages1.cebu International V. Ca 316 SCRA 488Rhena SaranzaNo ratings yet

- Legal Memo - Collection of Sum of MoneyDocument9 pagesLegal Memo - Collection of Sum of MoneyArnold Cavalida Bucoy100% (3)

- MANILA-BANKING-V-TEODORO DigestDocument4 pagesMANILA-BANKING-V-TEODORO DigestLau NunezNo ratings yet

- Amrit Lal Goverdhan Lalan Vs State Bank of TravancoreDocument9 pagesAmrit Lal Goverdhan Lalan Vs State Bank of TravancoreEbadur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Villaroel vs. EstradaDocument9 pagesVillaroel vs. EstradaMitchayNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellant vs. vs. Defendant-Appellee Gerardo P. Moreno, Jr. N. O. BuenoDocument8 pagesPlaintiff-Appellant vs. vs. Defendant-Appellee Gerardo P. Moreno, Jr. N. O. BuenoGabe BedanaNo ratings yet

- Odiamar vs. ValenciaDocument2 pagesOdiamar vs. Valenciazandree burgos100% (1)

- Liam Law v. Olympic Sawmill Co., G.R. L-30771 (Usury Law Is For Some Time NowDocument2 pagesLiam Law v. Olympic Sawmill Co., G.R. L-30771 (Usury Law Is For Some Time Nowavelim44No ratings yet

- Oblicon QuestionsDocument3 pagesOblicon QuestionsDanNo ratings yet

- Oblicon DoctrineDocument73 pagesOblicon Doctrineleziel.santosNo ratings yet

- University School of Law and Legal Studies, GgsipuDocument7 pagesUniversity School of Law and Legal Studies, GgsipuAnand mishraNo ratings yet

- Group 1 ReportingDocument12 pagesGroup 1 ReportingPrincess ParasNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-28569. February 27, 1970 J. M. TUASON & Co. INC., Plaintiff-Appellant, v. LIGAYA JAVIER, Defendant-AppelleeDocument23 pagesG.R. No. L-28569. February 27, 1970 J. M. TUASON & Co. INC., Plaintiff-Appellant, v. LIGAYA JAVIER, Defendant-AppelleeKristin C. Peña-San FernandoNo ratings yet

- Jan 15 2019 Compiled Cases, UnfinishedDocument13 pagesJan 15 2019 Compiled Cases, Unfinishedjimmy100% (1)

- Dario Nacar Vs Gallery FramesDocument2 pagesDario Nacar Vs Gallery FramesJerald ParasNo ratings yet

- The Contract Act: Law, BC & Ethics - Newly Added Questions in Latest Practice Manual (April 2016)Document20 pagesThe Contract Act: Law, BC & Ethics - Newly Added Questions in Latest Practice Manual (April 2016)Vasanth KumarNo ratings yet

- Law Cases Batch 2Document27 pagesLaw Cases Batch 2SofiaNo ratings yet

- Quasi ContractDocument17 pagesQuasi ContractGenesia Pereira100% (2)

- 6.quiamco vs. Capital InsuranceDocument4 pages6.quiamco vs. Capital InsuranceBasmuthNo ratings yet

- Full Case Piczon Vs PiczonDocument2 pagesFull Case Piczon Vs PiczonYanaglyzzaNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. Grisaldo Whether The Loss of Chattel Mrotgage Extinguishes The ObligationDocument4 pagesRepublic vs. Grisaldo Whether The Loss of Chattel Mrotgage Extinguishes The ObligationGerald Bowe ResuelloNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument4 pagesCase DigestEugene Albert Olarte JavillonarNo ratings yet

- GR 130994Document9 pagesGR 130994Seventeen 17No ratings yet

- With A Period-Extinguishments CASESDocument7 pagesWith A Period-Extinguishments CASESMelanie Graile TumaydanNo ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument5 pagesCase AnalysisrhobiecorboNo ratings yet

- CT CasesDocument13 pagesCT CasesMique VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Credit 1st SetDocument8 pagesCredit 1st SetRhena SaranzaNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Labor Contract Law of the People's Republic of China (2007)From EverandLabor Contract Law of the People's Republic of China (2007)No ratings yet

- Alexander V Railway Executive - (1951) 2 AllDocument7 pagesAlexander V Railway Executive - (1951) 2 AllFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Note Mercantile Credit Co LTD V Hamblin - (Document1 pageNote Mercantile Credit Co LTD V Hamblin - (FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Farnworth Finance Facilities LTD V Attryde ADocument6 pagesFarnworth Finance Facilities LTD V Attryde AFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Parliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaDocument5 pagesParliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Frederick E Rose (London) LTD V WM H Pim, JuDocument11 pagesFrederick E Rose (London) LTD V WM H Pim, JuFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain V BoDocument4 pagesPharmaceutical Society of Great Britain V BoFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 20 of 2014Document12 pages20 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Chapelton V Barry Urban District Council - (Document6 pagesChapelton V Barry Urban District Council - (FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 32 of 2014Document11 pages32 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- A Roberts & Co LTD and Another V LeicestershDocument9 pagesA Roberts & Co LTD and Another V LeicestershFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction 8th Amendment 2137 40Document2 pagesJurisdiction 8th Amendment 2137 40FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 085 NLR NLR V 04 He Estate of Margaret WernhamDocument6 pages085 NLR NLR V 04 He Estate of Margaret WernhamFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Y%S, XLD M Dka %SL Iudcjd Ckrcfha .Eiü M %H: The Gazette of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaDocument2 pagesY%S, XLD M Dka %SL Iudcjd Ckrcfha .Eiü M %H: The Gazette of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 25 of 2011Document9 pages25 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 17 of 2014Document8 pages17 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 12 of 2011Document3 pages12 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 46 of 2007Document3 pages46 of 2007FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 29 of 2011Document6 pages29 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 04 of 2014Document11 pages04 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 18 of 2014Document3 pages18 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Parliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaDocument10 pagesParliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 15 of 2014Document3 pages15 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 14 of 2014Document18 pages14 of 2014FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 7 of 2011Document10 pages7 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 37 of 2011Document10 pages37 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 2 of 2011Document3 pages2 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- Parliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaDocument8 pagesParliament of The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri LankaFelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 16 of 2011Document3 pages16 of 2011FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 10 of 2007Document58 pages10 of 2007FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- 26 of 2007Document19 pages26 of 2007FelicianFernandopulleNo ratings yet

- State of West Bengal: The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 1975 Crilj 1249Document14 pagesState of West Bengal: The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 1975 Crilj 1249Rupali RamtekeNo ratings yet

- TortsDocument44 pagesTortsajay narwalNo ratings yet

- Purisima vs. Ricafranca G.R. No. 237530 November 29 2021Document19 pagesPurisima vs. Ricafranca G.R. No. 237530 November 29 2021Rikki Marie PajaresNo ratings yet

- Souradeep Rakshit: SubjectDocument15 pagesSouradeep Rakshit: SubjectSaif AliNo ratings yet

- Custodial Investigation Section 12. (1) Any Person Under Investigation For The Commission of AnDocument5 pagesCustodial Investigation Section 12. (1) Any Person Under Investigation For The Commission of AnBananaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Masipil, GR No. 85177Document8 pagesPeople vs. Masipil, GR No. 85177G-ONE PAISONESNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 248202Document11 pagesG.R. No. 248202Moyna Ferina RafananNo ratings yet

- Unified Maine Common Law Grand Jury: Lex Naturales Dei GratiaDocument3 pagesUnified Maine Common Law Grand Jury: Lex Naturales Dei GratiaLEBJ100% (1)

- Tierzah Mapson IndictmentDocument18 pagesTierzah Mapson IndictmentNational Content DeskNo ratings yet

- Travel-On v. CA / PP v. ManiegoDocument2 pagesTravel-On v. CA / PP v. ManiegolchieSNo ratings yet

- 12/04/19 - Gideon's Army Weekly Conference Call Saturday 9 Am CST For American Political PrisonersDocument26 pages12/04/19 - Gideon's Army Weekly Conference Call Saturday 9 Am CST For American Political PrisonersLoneStar1776No ratings yet

- Reportable: Bhagwan Singh ..... Appellants(s) Versus State of Uttarakhand ..... Respondents(s)Document11 pagesReportable: Bhagwan Singh ..... Appellants(s) Versus State of Uttarakhand ..... Respondents(s)Rudresh Shubham SinghNo ratings yet

- Cases - Quantum of EvidenceDocument13 pagesCases - Quantum of EvidenceCzarina CidNo ratings yet

- Tan Tek Beng Case - Legal EthicsDocument10 pagesTan Tek Beng Case - Legal EthicsShannin MaeNo ratings yet

- Case Digests2.1Document6 pagesCase Digests2.1Charlotte SagabaenNo ratings yet

- Foronda vs. Guerrero: FactsDocument23 pagesForonda vs. Guerrero: FactsErin GamerNo ratings yet

- Second Auburn Hospital LawsuitDocument18 pagesSecond Auburn Hospital LawsuitJames MulderNo ratings yet

- (Indispensable Party, Solidary Obligation) : G.R. No. 193753, September 26, 2012 Facts RulingDocument5 pages(Indispensable Party, Solidary Obligation) : G.R. No. 193753, September 26, 2012 Facts RulingAira GraileNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Injunction R58 Fulltext CasesDocument113 pagesPreliminary Injunction R58 Fulltext CasesAudreyNo ratings yet

- Right To Confront WitnessesDocument13 pagesRight To Confront WitnessesAlona Medalia Cadiz-GabejanNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 3962, February 10, 1908Document11 pagesG.R. No. 3962, February 10, 1908You EdgapNo ratings yet

- Sherrill v. Commandant, USDB, 10th Cir. (2004)Document5 pagesSherrill v. Commandant, USDB, 10th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 12th Quarterly Report For Oakland NSADocument85 pages12th Quarterly Report For Oakland NSAali_winstonNo ratings yet

- 51 Secretary of Justice vs. LantionDocument1 page51 Secretary of Justice vs. LantionNMNGNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Castro vs. Bustos FULL TEXTDocument6 pagesHeirs of Castro vs. Bustos FULL TEXTRuth Abigail R. Acero-FloresNo ratings yet

- US Vs PompeyaDocument8 pagesUS Vs PompeyaAlvin HalconNo ratings yet