Professional Documents

Culture Documents

bellymodelsJHumLact 2008 Spangler 199 205

bellymodelsJHumLact 2008 Spangler 199 205

Uploaded by

Timothy JohnsonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

bellymodelsJHumLact 2008 Spangler 199 205

bellymodelsJHumLact 2008 Spangler 199 205

Uploaded by

Timothy JohnsonCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/5415880

Belly Models as Teaching Tools: What Is Their Utility?

Article in Journal of Human Lactation · June 2008

DOI: 10.1177/0890334408316079 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

0 5,301

4 authors, including:

Andrea L Randenberg Maeve Howett

Antelope Valley Hospital University of Massachusetts Amherst

3 PUBLICATIONS 63 CITATIONS 18 PUBLICATIONS 107 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Break the Cycle of Children's Environmental Health Disparities View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Maeve Howett on 03 February 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Journal of Human Lactation http://jhl.sagepub.com/

Belly Models as Teaching Tools: What Is Their Utility?

Amy K. Spangler, Andrea L. Randenberg, Michelle G. Brenner and Maeve Howett

J Hum Lact 2008 24: 199

DOI: 10.1177/0890334408316079

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jhl.sagepub.com/content/24/2/199

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

International Lactation Consultant Association

Additional services and information for Journal of Human Lactation can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jhl.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jhl.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://jhl.sagepub.com/content/24/2/199.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Apr 24, 2008

What is This?

Downloaded from jhl.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on January 13, 2012

Reviews

Belly Models as Teaching Tools: What Is Their Utility?

Amy K. Spangler, MN, IBCLC, Andrea L. Randenberg, BSN, IBCLC, Michelle G. Brenner, MD, IBCLC,

and Maeve Howett, PhD, IBCLC

Abstract

Marble/ball models are often used to represent newborn stomach capacity; however, their accu-

racy has not been determined. The objective of this review was to analyze data on newborn

stomach capacity and determine whether marble/ball models serve as accurate representations.

A literature search yielded limited data, most emanating from the early 1900s. Data suggest that

anatomic capacity of the newborn stomach varies with the birth weight of the infant. Physiologic

capacity bears no relation to anatomic capacity of the newborn stomach but is a measure of the

ability of the mother to produce milk and the newborn to ingest milk. Given the wide range of

feeding volumes on days 1 and 3 and the reported 8-fold increase in average feeding volume

during the same time period, it is best to acknowledge that feeding volumes like anatomic stom-

ach capacity vary widely and do not lend well to visual representation by marble/ball models.

J Hum Lact. 24(2):199-205.

Keywords: newborn stomach capacity; marble/ball models; physiologic capacity;

anatomic capacity

Introduction removal.1,2 However, it is not unusual in the early puer-

perium for parents to express a concern that there appears

Healthy, full-term, breastfed, newborn infants typically

to be very little “milk” or colostrum in the mother’s

have no need for supplements to their mothers’ milk

breasts. In an effort to allay their concerns, it is a popular

assuming early, frequent feeds, and adequate milk

practice among breastfeeding educators to use a set of

balls, beads, nuts, marbles, or similar objects as a teach-

Received for review April 23, 2007; revised manuscript accepted for publi-

cation December 28, 2007. ing tool to illustrate the small size of a newborn infant’s

Amy K. Spangler is a registered nurse as well as an international board certi-

stomach. Use of belly models is a way of demonstrating

fied lactation consultant. She has served as president of the International to new parents that the small amount of colostrum pro-

Lactation Consultant Association and chair of the United States Breastfeeding duced by the breast may match the amount the newborn

Committee. She is a member of the affiliate faculty at Emory University School

of Nursing and a perinatal instructor at Northside Hospital. Andrea L.

infant’s stomach can hold. The belly models also reinforce

Randenberg is a registered nurse certified in neonatal intensive care nursing as the need for the infant and mother to remain close together

well as an international board certified lactation consultant. Michelle G. for frequent and uninterrupted feedings.3 A 2006 La Leche

Brenner is an international board certified lactation consultant. She has been in League International publication4 about colostrum intake

private practice pediatrics and is currently in academic pediatric practice at

Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters in Norfolk, Virginia. She is reports that

a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding, the

International Lactation Consultant Association, and the Academy of Breastfeed- A one day old baby’s stomach capacity is about 5-

ing Medicine. Maeve Howett is a pediatric nurse practitioner and lactation con- 7 ml or about the size of a marble. By day three the

sultant in Atlanta, Georgia. She is presently a clinical assistant professor in newborn’s stomach capacity has grown to about

family and community nursing at Emory University. Her research interests are

interdisciplinary, focusing on women’s experiences of infant feeding in breast-

0.75-1 ounce (22-29 ml) or about the size of a

feeding and nonbreastfeeding mothers and early childhood nutrition. “shooter” marble. Around day seven the newborn’s

Address correspondence to Amy K. Spangler, MN, IBCLC, 12 Ball Creek stomach capacity is now about 1.5-2 ounces (44-59

Way, Atlanta, GA 30350; e-mail: amy@amysbabies.com. ml) or about the size of a ping-pong ball.

J Hum Lact 24(2), 2008

DOI: 10.1177/0890334408316079 Comparable teaching tools assign similar but slightly

© Copyright 2008 International Lactation Consultant Association different capacities to the small marble (5-7 mL),

199

Downloaded from jhl.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on January 13, 2012

200 Spangler et al J Hum Lact 24(2), 2008

shooter marble (22-27 mL), and ping pong ball (60-81 taken by newborns is a consequence of colostrum avail-

mL).5 The popularity of these tools suggests that a ability, or the delay in lactogenesis II is an adaptation for

visual representation of a newborn’s stomach capacity infant protection, it is important to note that although

is clinically useful to practitioners as an adjunct to par- healthy, full-term infants possess sufficient nutrient stores

ent education. This review is an effort to understand if to maintain homeostasis, these stores may be insufficient

the belly models are expressing accurate information or depleted in preterm, ill, or at-risk infants (an infant of

about infant stomach capacity and feeding volumes in a diabetic mother, those born with meconium-stained

the newborn period, as the initial data to support the fluid, or birth asphyxia).8

use of the models was published nearly a century ago. One potential explanation for small feeding volumes in

the hours immediately after birth was suggested by

First Days and Small Volumes Zangen et al9 as an immature gastric relaxation response

in accommodating the entry of a meal. In an effort to gain

Before birth, the fetus is housed in a sterile environ-

insight into the mechanisms for early satiety in the first

ment and the stomach is exposed only to amniotic fluid.

days of life, a latex balloon attached to an 8-French feed-

Soon after birth, the newborn is exposed to an open

ing tube was inserted into the stomach of live newborns.

environment and the stomach must process nutrient-

The researchers evaluated pressure and volume changes

dense colostrum or infant formula. Although mechanisms

in the stomach using a computer-driven air pump to

responsible for the rapid growth and functional matura-

inflate the balloon and measure volume. Receptive relax-

tion of the stomach remain unclear, there is evidence that

ation and compliance increased in response to distention

both endogenous hormones and ingested nutrients play

over the first 80 hours after birth and the volume of air

an important role.6

required to fill the stomach to a maximum pressure (30

During the period immediately after birth, the gas-

mm Hg) more than doubled during this period. Gastric

trointestinal tract undergoes profound growth, structural

volumes at the maximum pressure ranged from 38 to 76

change, and functional maturation.6 Mechanisms respon-

mL. Increasing age and the number of feedings accounted

sible for the changes remain to be elucidated, but there is

for more than half the measured changes in volume but

evidence that ingested colostrum and immunoglobulins

explaining how a few hours and a few meals alter gas-

contained therein may play an important role.6 The most

tric neuromuscular function can only be speculative,

common explanation for small feeding volumes ingested

given the many physiologic changes during the first

by breastfeeding infants in the hours following birth is

days after birth. Suggesting that infants have “imma-

the limited availability of colostrum in the maternal

ture” relaxation is inadequate to explain why small

breast; however, the normal delay of the breast in sup-

volumes are physiologic; however, the findings by

plying copious amounts of milk may instead represent

Zangen et al9 add further support to the importance of

one part of a complex physiologic process of assimilat-

not overfeeding in the first days.

ing the newborn into the outside world.

An editorial7 published in The Lancet in 1965

The Transition to Higher Volumes

described the first feed,

Apart from the findings of Zangen et al, little is known

In the general physiological upheaval after birth, about infant stomach capacity in the first days of life. The

the first feed has excited less interest than the first first reports of infant stomach capacity were published

breath. If a healthy, mature baby is put to the in the late 1800s using postmortem examination—

breast or is offered a bottle soon after birth, so lit- obviously a poor substitute to measurement in a live

tle is taken in volume and calories those three model.10,11 In 1894, Zuccarelli attempted to measure the

days of self-imposed starvation can be regarded capacity for stomach distention by removing the stomach

as physiological. from the body of newborn infants and distending it with

water. The stomach contents after distention were approx-

The reasons for this relative fast for the first 2 or 3 days imately 4.5 times the original volumes (33 mL as com-

are unclear. It is likely multifactorial and may represent pared with 7 mL).6,12

an important mechanism of adaptation to extrauterine life The first reports in live infants were done by Scammon

that requires the infant and mother be close together for and Doyle13 in 1920 and focused on changes in gastric

frequent feedings. Whether the small feeding volume capacity during the first 10 days of life. Scammon and

Downloaded from jhl.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on January 13, 2012

J Hum Lact 24(2), 2008 Belly Balls as Teaching Tools 201

Table 1. Physiologic and Anatomic Stomach Capacity

Author Method Measure Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Day 6 Day 7 Day 8 Day 9 Day 10

Scammon Prefeed and Physiologic 7 (3-60) 13 (4-60) 27 (3-110) 36 (5-130) 57 (8-140) 64 (2-155) 68 (10-145) 71 (10-160) 76 (5-148) 81 (10-210)

and Doyle postfeed capacity, mL

(1920)13 weighing (range)

Scammon Postmortem Anatomic 30-35

and Doyle exam capacity, mL

(1920)13

Doyle referred to anatomic stomach capacity as the In 1987, sonogram was first used to measure stom-

term given to the stomach volume measured by post- ach size and was found to positively correlate with ges-

mortem examination. Approximate feeding volume tational age from 9 to 40 weeks gestation.12 However,

obtained by prefeed and postfeed weighing in live the reliability of sonographic assessment of stomach

infants was termed physiologic capacity of the stom- capacity based on stomach dimensions has not yet

ach.14 Scammon and Doyle13,14 clarified their use of been documented. Children of the same weight and

the term by emphasizing that age might be expected to have similar stomach capac-

ities; however, varied metabolic rates, caloric needs,

Physiologic capacity shows little relation to the and feeding frequencies may affect feeding volumes.

anatomic (actual) capacity of the organ (stomach) Milk intake or transfer during a breastfeeding is

but is rather a measure of the ability of the aver- affected by a number of variables, including, but not

age mother to furnish nourishment in this period limited to, the amount of milk available in the breast

and the ability of the average child to receive it. (affected by the timing of lactogenesis II), infant suck-

ling skills, breastfeeding techniques, and the length of

Despite being the accepted standard mechanism for time between feedings.

assessing breast milk intake, test weighing is actually Saint et al,15 using an integrating electronic balance to

a measure of milk transfer (a reflection of the volume measure milk intake, reported that the average amount

of the milk that is provided and ingested) (see Table 1) of milk yield during the first 24 hours after birth in a

and not a measure of anatomic capacity. sample of 9 women was 37.1 mL, with a range of 7 to

Unlike our current understanding of the need to 122 mL. On day 3 postpartum, an average milk yield of

breastfeed an infant 8 to 12 times in a 24-hour period, 408 mL was reported, with a range of 98 to 775 mL.

infants in Scammon’s study were breastfed no more than A significant correlation was found between milk

5 times a day, with many infants fed less than 5 times a intake, determined by weighing the infant, and milk

day; infants on day 1 received on average 1 to 2 feedings. yield (milk volume extracted from the mother), deter-

The infants are described as “breastfed” and no mention mined by weighing the mother, but neither provide evi-

is made of supplemental feedings. No indication is given dence of stomach capacity. Milk yield was not related to

as to why the number of feedings was limited but is prob- parity. Infants in the study by Saint et al15 breastfed an

ably reflective of the encroachment of a cultural shift in average of 6 times in the first 24 hours with a range of 3

infant care that was well intentioned but based upon arti- to 8 feedings. On day 2, infants fed an average of 7.5

ficial feeding schedules. It is also important to note that times a day with a range of 5 to 10 feedings. There was

the average feeding volumes listed in the study (and no significant correlation between milk yield and feeding

termed physiologic stomach capacities) represented a frequency for the first 5 postpartum days. However, by

wide range of values among mother-infant pairs with 3 day 14 and day 28 there was a significant positive corre-

mL being the smallest amount and 60 mL being the lation between milk yield and feeding frequency.

largest amount consumed at a feeding on day 1. Infor- Neville8 described a pattern of milk intake in which

mation on parity and prior breastfeeding experience was mean milk transfer is low during the first 2 days post-

not provided.13 However, based on this and other data partum, rises rapidly on days 3 and 4, correlating with

published at the time, Scammon calculated the average the timing of lactogenesis II, and then increases more

newborn anatomic capacity to be 30 to 35 mL at birth slowly to reach maximum levels of approximately 800

and 100 mL by 4 weeks of age, representing a 3-fold mL per day at 6 months postpartum in exclusively

increase.14 breastfeeding women.

Downloaded from jhl.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on January 13, 2012

202 Spangler et al J Hum Lact 24(2), 2008

Table 2. Anatomic Stomach Capacity Measured by Naveed degree to which repeated measurements or calculations

et al16 at Autopsy will show the same or similar results. If a procedure is

Birth Weight, g Stomach Capacity, mL imprecise, its clinical usefulness is hampered consider-

ably. The results of calculations of a measurement can be

500-1000 (n = 21) 6-10

1001-1500 (n = 18) 10-12 accurate but not precise; precise but not accurate; neither

1501-2000 (n = 22) 12-15 or both. A result is valid if it is both accurate and precise.

2001-2500 (n = 19) 15-18 Neville17 reported that test weighing is an accurate

> 2500 (n = 20) 18-21

indicator of breast milk intake. Meier et al18,19 reported

that test weighing for this purpose is slightly inaccu-

rate because of evaporative water loss but that this

The Correlation Between Stomach Capacity

and Birth Weight

inaccuracy is too small to be clinically relevant.

Savenije and Brand20 concluded that test weighing

Not unlike the 19th-century colleagues discussed earlier, is an accurate but imprecise method for assessing milk

Naveed et al16 examined 100 perinatal autopsy speci- intake in young infants and should therefore not be

mens from 63 fresh stillbirths and 37 deaths occurring in used in clinical practice. Their conclusions were based

the first week after birth in an effort to determine stom- on a single set of prefeeding and postfeeding weight

ach capacity as it relates to birth weight. The stomach measurements for each study infant in an attempt to

was decompressed and tied at the cardiac and pyloric reflect practice in actual clinical situations in which

end. They then loosened the cardiac end and filled the test weighing is used, rather than repeated samples, as

stomach with water using a 10-mL syringe until the fun- occurs in most research studies.

dus of the stomach ballooned out with obliteration of the It is important for clinicians to understand the benefits

gastric curvatures. The water was then retrieved and the of test weighing as well as the limitations, especially

volume recorded. Naveed et al calculated the mean of 2 when small incremental changes are being measured.

consecutive measurements differing by less than 5%. Data show that when following strict research protocols,

Care was taken to minimize stretch artifacts and mea- test weighing provides an accurate estimate of intake

surement errors. They found that the larger the infant, the across a range of infant weights and intake volumes.19

greater the stomach capacity, suggesting a positive cor- Before clinical interventions are entertained, multiple

relation between measured stomach capacity and birth measurements as well as clinical indices should be ascer-

weight. tained. In a research setting, where repeated measure-

Table 2 shows the estimated stomach capacity for ments are obtained and then averaged, test weighing

infants of different birth weights, as derived from a lin- with suitable scales can be both accurate and precise.

ear regression equation. There was no significant dif- However, in a clinical setting, it is also important for the

ference between live born and stillborn infants in any clinician to take several weights and compute the aver-

of the weight groups except in the 1501 to 2000 g age, as no single measurement can be considered reli-

weight range (anatomic). Stomach capacity reportedly able. The accuracy of a single test weight can vary from

had no relation to the total number of feeds in the live +15 to −15 mL, therefore the usefulness of a single test

born group. This finding contradicts that of Zangen weight in assessing intake, particularly when very small

et al who reported that volume was affected by both amounts of milk are consumed, is limited.

increasing age and the number of feedings. Zangen Although prefeeding and postfeeding weights are

et al,9 however, studied healthy, live newborns, whereas considered reliable research tools for measuring milk

the data in the study by Naveed et al16 were derived from transfer and average feeding volumes, these data cannot

autopsy examinations. be extrapolated to estimate either the size of the stomach,

the physiologic capacity of the stomach, or the volume of

Prefeed and Postfeed Weights fluid the organ is capable of containing, thus it is not

appropriate to use measurements of prefeeding and post-

Numerous studies have examined the reliability of test

feeding weights to describe stomach capacity.

weighing. Accuracy is defined as the degree of confor-

mity of a measured or calculated quantity to its actual

Are the Marble/Ball Models Accurate?

(true) value, that is, the ability of a measurement tech-

nique to measure the true value of the property. Precision, After reviewing the literature, it appears that the avail-

also referred to as reproducibility or repeatability, is the able research does not provide any evidence to support

Downloaded from jhl.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on January 13, 2012

J Hum Lact 24(2), 2008 Belly Balls as Teaching Tools 203

Table 3. Volume of Hollister Belly Ball Modelsa

Age of Infant, d Object Stated Volume, mL Mathematical Formula, mL Displacement Method, mL

Original tool

1 Small marble 5-7 1.77 2.0

3 Shooter marble 22-27 8.2 9.0

10 Ping pong ball 60-81 27.6 30

Revised tool

1 Shooter marble 5-7 8.2 9.0

3 Ping pong ball 22-27 27.6 30

10 Extra-large chicken egg 60-81 Nonspherical, volume not calculated 60

a

The “Belly Balls Lactation Tool” by Hollister, Inc has recently been modified. The revised tool contains a shooter marble, ping pong ball, and extra-large

chicken egg represented by a plastic egg.

the use of marble/ball models to represent newborn

stomach capacity or stomach size. Based on available

data (see Tables 1 and 2), these models may be useful

only as a representation of average breast milk intake

during the early newborn period.

Given their popularity, we decided to explore the fea-

sibility of using the models as a visual representation of

average feeding volume. Using data from Saint et al,15 the

average amounts of colostrum produced on days 1 and 3

were 37 mL and 408 mL, respectively. By day 14 average

milk yield was 1156 mL. Study infants reportedly breast-

fed an average of 6 times on day 1 and 7.5 times on day

3.15 To determine average feeding volume, we divided the

average amount of colostrum produced on days 1 and 3

by the average number of feeds. The average feeding vol-

ume was 6.1 mL on day 1 and 54.4 mL on day 3.

In an effort to determine the accuracy of the marble/

ball models to represent average feeding volumes during

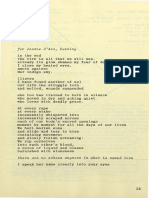

Figure 1. Original Hollister Belly Ball models. The illustrated cir-

the first 10 days of life, we calculated the volume (capac- cles above are not meant to be accurate representations of

ity) of the small marble, shooter marble, and ping pong the actual Belly Ball models by Hollister (2006).

ball obtained from the “Belly Balls Lactation Tool” by

Hollister, Inc (see Figure 1) using the following methods:

the small marble and shooter marble are now assigned

(1) pouring a measured amount of water into a container

to the shooter marble and ping pong ball. The small

with milliliter markings (volufeed bottle), then measuring

marble has been removed and an extra-large chicken

the amount of water displaced when the object is inserted

egg has been added. The results in Table 3 show that

into the container, and (2) applying a mathematical

the revised marble/ball models more accurately reflect

formula for determining volume (capacity), that is, mul-

stated volumes. However, it appears that neither the

tiplying the diameter (d) cubed by π (3.14), then dividing

original nor the revised models could be useful in

the product by 6, noting that 1 cm3 = 1 mL (see Table 3).

accurately representing average breast milk intake on

A 6-inch (152 mm) Dial Caliper (General Tools Manu-

days 1, 3, or 10.

facturing Company, New York; No. 142, UPC 44145)

was used to measure the diameter of each object. The

The Implications of Exceeding Stomach Capacity

small marble measured 1.5 cm in diameter, the shooter by Overfeeding the Newborn

marble measured 2.5 cm in diameter; and the ping pong

ball measured 3.75 cm in diameter. At birth, gastroesophageal sphincter tone is poor,

The “Belly Ball Lactation Tool” has recently been offering little resistance to regurgitation of food. In

revised (see Figure 2). Values previously assigned to addition, the emptying time of the newborn stomach is

Downloaded from jhl.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on January 13, 2012

204 Spangler et al J Hum Lact 24(2), 2008

Discussion

The benefits of breastfeeding are compelling and a

growing body of evidence shows that exclusive breast-

feeding for the first 6 months of life is optimal.25 With

greater emphasis on exclusive breastfeeding and growing

concern over obesity and its health problems, health care

professionals are rightly concerned about the amount of

milk a mother produces and the amount of milk a baby

Figure 2. Revised Hollister Belly Ball models. The illustrated cir- consumes in the first days after birth.

cles above are not meant to be accurate representations of Measurement of infant stomach capacity has been

the actual belly ball models by Hollister (2007). Scammon attempted for over 100 years. Exact volumes cannot be

R, Doyle L. Observations on the capacity of the stomach

in the first ten days of postnatal life. Am J Dis Child.

standardized, but data suggest that anatomic stomach

1920;20:516-538. Naveed M, Manjunath C, Sreenivas V. capacity16 and physiologic stomach capacity vary widely.15

An autopsy study of relationship between perinatal stom- During the first 3 days after birth, the newborn stomach

ach capacity and birth weight. Indian J Gastroenterol. becomes more compliant and develops greater receptive

1992;11:156-158. http://www.ameda.com/breastfeeding/ relaxation, associated with a larger volume capacity.9 These

started/stomach.aspx. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

changes in the newborn stomach, combined with the con-

comitant increase in milk production associated with lacto-

slow; barium studies during the first week of life show

genesis II, help to explain the progression of feeding

failure of complete emptying even after 24 hours.21

volumes over the first 10 days of life.

Gastroesophageal reflux, the retrograde movement of

Recognizing the usefulness of visual aids in com-

food and acid from the stomach into the esophagus and

municating educational concepts such as feeding vol-

sometimes the oropharynx, occurs often in infants. It is

ume, is there an alternative to the marble/ball models?

described by parents as “spitting up” and causes little

Saint et al reported average feeding volume on day 1

concern unless it interferes with feeding and nutrition,

of 6.1 mL, therefore one possible model could be a tea-

causes poor weight gain, discomfort, damages the esoph-

spoon (1 teaspoon = 5 mL). As a familiar household

agus, leads to breathing difficulties, or continues beyond

object, a teaspoon would reinforce to families that the

infancy into childhood. Harris et al22 reported that aspira-

small amount of colostrum ingested per feeding on day

tion of gastric contents is responsible for 3 out of every

1 is normal and adequate for their infant.

100 000 deaths among infants less than 1 year of age.22

Additionally, a teaspoon could be used to supplement

Premature and sick infants have an even greater risk for

those infants who fail to latch on and breastfeed effectively

aspiration due to small stomach size, poor cough reflex,

for one or more feedings. However, it is important to note

and inability to coordinate suckling, swallowing, and

that because a wide range of feeding volumes on day 1

breathing.23 It has been suggested that the volume of

(1.1-20.4 mL) and day 3 (13.1-103.3 mL) has been

liquid that can be safely administered to a neonate is

reported, and the reasons for these variances are unclear, it

determined by the capacity of the stomach. Researchers

may be best to simply acknowledge that feeding volumes

acknowledge that there is much to be learned about

vary widely and like stomach capacity, do not lend well to

appropriate feeding volumes during the first days after

visual representation given our current knowledge.

birth, and report high variability in the intake of

colostrum by exclusively breastfed infants during that

Suggestions for Future Research

time period.15,24 Yamauchi and Yamanouchi24 reported

intake of 168.2 to 406.6 mL of breast milk in 24 hours on Factors that potentially impact feeding volumes (and

day 3, whereas Saint et al15 reported milk yield of 98.3 to changes in feeding volumes) during the first week of

775 on day 3. Were accurate data on stomach capacity life include availability of milk, infant suckling skills,

available, they could be used to guide the clinician in physiologic mechanisms (caloric needs, gastric empty-

determining the volume of a feed for ill or premature ing time, intestinal motility, gastric relaxation and

infants, and the volume of supplement for infants unable compliance), length of feeding, and frequency of feed-

to breastfeed for one or more feedings. ings. The relationship of these factors and their affect

Downloaded from jhl.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on January 13, 2012

J Hum Lact 24(2), 2008 Belly Balls as Teaching Tools 205

on milk transfer need to be explored further to deter- 18. Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Fleming BA, Streeter PL, Lawrence PB.

Estimating milk intake of hospitalized preterm infants who breastfeed.

mine their contribution to the small feeding volumes J Hum Lact. 1996;12:21-26.

during the first few days after birth and the increase in 19. Meier PP, Engstrom JL, Crichton CL, Clark DR, Williams MM,

feeding volumes thereafter. The work in Australia Mangurten HH. A new scale for in-home test-weighing for mothers of

preterm and high risk infants. J Hum Lact. 1994;10:163-168.

using high-resonance sonography to study suckling

20. Savenije O, Brand P. Accuracy and precision of test weighing to assess

suggests further possibilities for understanding stom- milk intake in newborn infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

ach capacity.26 A large-scale research study would be 2006;91:330-332.

helpful in determining average volumes that can be 21. Belknap W. Principles and Practices of Pediatrics. Philadelphia, PA:

Lippincott; 1990.

consistently validated, whether physiologic capacity 22. Harris C, Baker S, Smith G, Harris R. Childhood asphyxiation by

differs between breastfed and formula-fed infants, and food: a national analysis and review. JAMA. 1984;251:2231-2235.

clinical indicators of overfeeding. 23. Singh M. Disorders of weight and gestation. In: Singh M, ed. Care of

the Newborn. 3rd ed. New Delhi, India: Sagar Publications; 1985.

24. Yamauchi Y, Yamanouchi I. Breast-feeding frequency during the first 24

References hours after birth in full-term neonates. Pediatrics. 1990;86:171-175.

1. Nylander G, Lindemann R, Helsing E, Bendvold E. Unsupplemented 25. Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

breastfeeding in the maternity ward. Positive long-term effects. Acta Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(1):CD003517.

Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1991;70:205-209. 26. Ramsay DT, Kent JC, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. Ultrasound imaging

2. Kramer MS, Kakuma R. The optimal duration of exclusive breast- of milk ejection in the breast of lactating women. Pediatrics. 2004;

feeding: a systematic review. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;554:63-77. 113:361-367.

3. Smith L. Coach’s Notebook: Games and Strategies for Lactation

Education. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2002.

4. La Leche League International. What is Colostrum? How Does It Benefit

Resumen

My Baby? Schaumburg, IL: La Leche League International; 2006.

5. Belly Balls Lactation Education Tool. Libertyville, IL: Hollister;

Los modelos Bolas/Canicas (Marble/balls) se usan con

2005. frecuencia para representar la capacidad estomacal del

6. Xu R. Development of the newborn GI tract and its relation to colostrum/ recién nacido, pero su precisión no se ha determinado. El

milk intake: a review. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1996;8:35-48.

7. The first drink [editorial]. Lancet. 1965;1:791-792.

objetivo de esta revisión fue de analizar datos sobre la

8. Neville M. Studies in human lactation: milk volumes in lactating capacidad estomacal del recién nacido y determinar si los

women during the onset of lactation and full lactation. Am J Clin Nutr. modelos marble/ball son representaciones precisas. Una

1988;48:1375-1386. revisión de la literatura mostró datos muy limitados, la

9. Zangen S, Di Lorenzo C, Zangen T, Mertz H, Schwankovsky L,

Hyman P. Rapid maturation of gastric relaxation in newborn infants. mayoría de principios de los 1900s. Los datos sugieren

Pediatr Res. 2001;50:629-632. que la capacidad anatómica del estomago del recién

10. Guillot N. De la nourrice et du nourrisson. Union Med. 1852:61. nacido varia con el peso al nacer del bebe. La capacidad

11. Bouchard. De la mort par iuanition et etudes experimentales sur la

nutrition chez le nouveau-ne. 1864, Paris.

fisiológica no tiene relación con la capacidad anatómica

12. Goldstein I, Reece E, Yarkani S, Wan M, Green J, Hobbins J. Growth of del estomago del recién nacido, pero es la medida

fetal stomach in normal pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:641. de la habilidad de la madre de producir leche y la

13. Scammon R, Doyle L. Observations on the capacity of the stomach in

the first ten days of postnatal life. Am J Dis Child. 1920;20:516-538.

ingesta del recién nacido. Dado el gran margen de los

14. Scammon R. Some graphs and tables illustrating the growth of the volúmenes de alimentación en el día 1 y 3 y el aumento

human stomach. Am J Dis Child. 1919;17:395. de 8 veces reportado en el promedio del volumen de ali-

15. Saint L, Smith MM, Hartmann P. The yield and nutrient content of col- mentación durante el mismo periodo, es mejor reconocer

sotrum and milk of women from giving birth to 1 month post-partum.

Br J Nutr. 1984;52:87-95. los volúmenes de alimentación como la capacidad

16. Naveed M, Manjunath C, Sreenivas V. An autopsy study of relation- anatómica que varía en un gran margen y no confiarse a

ship between perinatal stomach capacity and birth weight. Indian la representación visual de los modelos marble/ball.

J Gastroenterol. 1992;11:156-158.

17. Neville M. Accuracy of single- and two-feed test weighing in assess-

ing 24-hr breast milk production. Early Hum Dev. 1984;9:275-281.

Downloaded from jhl.sagepub.com at EMORY UNIV on January 13, 2012

View publication stats

You might also like

- Adventures in Tandem NursingDocument3 pagesAdventures in Tandem NursingPesawaran VacationNo ratings yet

- Yarn ManufacturerersDocument31 pagesYarn ManufacturerersMarufNo ratings yet

- SeminarDocument10 pagesSeminarSridharNo ratings yet

- What Nurses Need To Know Regarding Nutritional and Immunobiological Properties of Human MilkDocument16 pagesWhat Nurses Need To Know Regarding Nutritional and Immunobiological Properties of Human MilkAmalia Dwi AryantiNo ratings yet

- Pacifier and Bottle Nipples: The Targets For Poor Breastfeeding OutcomesDocument3 pagesPacifier and Bottle Nipples: The Targets For Poor Breastfeeding Outcomesbeleg100% (1)

- flujos-tetinasDocument12 pagesflujos-tetinasmarisolpaulinaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics On BreastfeedingDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Topics On Breastfeedingafnhemzabfueaa100% (1)

- Apoyo A Diada - Guia para SLPDocument11 pagesApoyo A Diada - Guia para SLPPaula Belén Rojas CunazzaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Breast FeedingDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Breast Feedings1bivapilyn2100% (2)

- How Breastfeeding WorksDocument78 pagesHow Breastfeeding WorksgldsbarzolaNo ratings yet

- Breast Feeding Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesBreast Feeding Literature Reviewgatewivojez3No ratings yet

- Thesis On BreastfeedingDocument4 pagesThesis On Breastfeedingppxohvhkd100% (2)

- Nresearch PaperDocument14 pagesNresearch Paperapi-400982160No ratings yet

- Core_Curriculum_for_Lactation_ConsultantDocument2 pagesCore_Curriculum_for_Lactation_ConsultantsivasooryanutubeNo ratings yet

- Nresearch PaperDocument13 pagesNresearch Paperapi-399638162No ratings yet

- Review of Literature On Breast FeedingDocument9 pagesReview of Literature On Breast Feedingafmzkbuvlmmhqq100% (1)

- Research Paper On Benefits of BreastfeedingDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Benefits of Breastfeedingzyjulejup0p3100% (1)

- Benefits of BreastfeedingDocument2 pagesBenefits of BreastfeedingDavid GooseNo ratings yet

- Editorial: Breastmilk: It's Not Just For Breakfast Anymore!Document1 pageEditorial: Breastmilk: It's Not Just For Breakfast Anymore!lila bNo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding Benefits Research PaperDocument8 pagesBreastfeeding Benefits Research Paperafnhdcebalreda100% (1)

- Dissertation On Exclusive BreastfeedingDocument6 pagesDissertation On Exclusive BreastfeedingPaperWritingServicesCanada100% (1)

- A Review of The Breastfeeding Literature Relevant To Osteopathic PracticeDocument6 pagesA Review of The Breastfeeding Literature Relevant To Osteopathic PracticeYesenia PaisNo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding Thesis StatementDocument8 pagesBreastfeeding Thesis Statementhod1beh0dik3100% (2)

- Human Milk: Composition, Clinical Benefits and Future Opportunities: 90th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Lausanne, October-November 2017From EverandHuman Milk: Composition, Clinical Benefits and Future Opportunities: 90th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Lausanne, October-November 2017No ratings yet

- Lopez Bassols 2020 Assisted Nursing A Case Study of An Infant With A Complete Unilateral Cleft Lip and PalateDocument6 pagesLopez Bassols 2020 Assisted Nursing A Case Study of An Infant With A Complete Unilateral Cleft Lip and PalateNELSON VIDIGALNo ratings yet

- Midwifery: SciencedirectDocument10 pagesMidwifery: SciencedirectFarin MauliaNo ratings yet

- Calma Sistema de Alimentacion para Bebes Resumen de EstudioDocument16 pagesCalma Sistema de Alimentacion para Bebes Resumen de Estudiojaneth laprinceNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Breast FeedingDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Breast Feedingcpifhhwgf100% (1)

- Thesis On Exclusive BreastfeedingDocument5 pagesThesis On Exclusive Breastfeedingebonybatesshreveport100% (2)

- Breast 20 Feeding 5 B15 DDocument9 pagesBreast 20 Feeding 5 B15 DJaanuchowdary PolavarapuNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Bhs InggrisDocument9 pagesJurnal Bhs Inggrisyuliani utamiNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Through The Life Cycle 6Th Edition Brown Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument32 pagesNutrition Through The Life Cycle 6Th Edition Brown Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFnhanselinak9wr16100% (12)

- Nutrition Through The Life Cycle 6th Edition Brown Solutions ManualDocument11 pagesNutrition Through The Life Cycle 6th Edition Brown Solutions Manualrobertadelatkmu100% (30)

- Breastfeeding Dissertation TopicsDocument8 pagesBreastfeeding Dissertation TopicsBuyACollegePaperOnlineMilwaukee100% (1)

- Literature Review On Benefits of BreastfeedingDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Benefits of Breastfeedingafdtzgcer100% (1)

- Bowling Nur 4222 Integrated Review FinalDocument14 pagesBowling Nur 4222 Integrated Review Finalapi-349455792No ratings yet

- Biology of Metabolism in Growing AnimalsDocument491 pagesBiology of Metabolism in Growing AnimalsFernando CruzNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Exclusive Breastfeeding PDFDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Exclusive Breastfeeding PDFegtwfsaf100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0266613813002192 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0266613813002192 Mainnengsi susantiNo ratings yet

- Amamentação 1Document7 pagesAmamentação 1Rafael PereiraNo ratings yet

- E20160772 FullDocument10 pagesE20160772 FullRaehana AlaydrusNo ratings yet

- Am J Clin Nutr 2007 Fewtrell 635S 8SggDocument4 pagesAm J Clin Nutr 2007 Fewtrell 635S 8SggMariaNo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding and Infant Growth: Amber Gigi Hoi and Luseadra MckerracherDocument2 pagesBreastfeeding and Infant Growth: Amber Gigi Hoi and Luseadra MckerracherFranco AlminoNo ratings yet

- Previous Breastfeeding Experience and Its in Uence On Breastfeeding Outcomes in Subsequent Births: A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesPrevious Breastfeeding Experience and Its in Uence On Breastfeeding Outcomes in Subsequent Births: A Systematic ReviewChae YojaNo ratings yet

- Example Literature Review BreastfeedingDocument7 pagesExample Literature Review Breastfeedingafmzeracmdvbfe100% (2)

- Articulo Escalas 2019Document15 pagesArticulo Escalas 2019deboraNo ratings yet

- Effect of Early Limited Formula On Duration and ExDocument10 pagesEffect of Early Limited Formula On Duration and ExAdi Brando SagalaNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Breastfeeding Dyad - A Guide For Speech-Language PathologistsDocument5 pagesAssessing The Breastfeeding Dyad - A Guide For Speech-Language PathologistsPaloma LópezNo ratings yet

- Peer-to-Peer Milk Donors' and Recipients' Experiences and Perceptions of Donor Milk BanksDocument11 pagesPeer-to-Peer Milk Donors' and Recipients' Experiences and Perceptions of Donor Milk BanksFarin MauliaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Asi Craniofacial 2005Document9 pagesJurnal Asi Craniofacial 2005Masjid AlhudaNo ratings yet

- Milk Flow Rates From Bottle Nipples Used After Hospital DischargeDocument6 pagesMilk Flow Rates From Bottle Nipples Used After Hospital DischargeVânia CarolinaNo ratings yet

- Amir2016 Article SelectedAbstractsFromTheBreastDocument16 pagesAmir2016 Article SelectedAbstractsFromTheBreastLinda Puji astutikNo ratings yet

- OMA's ProjectDocument86 pagesOMA's Projectossaiprince709No ratings yet

- Benefits of Breastfeeding Research PaperDocument7 pagesBenefits of Breastfeeding Research Paperafedpmqgr100% (1)

- Experiences and Perspectives About Breastfeeding in "Public": A Qualitative Exploration Among Normal-Weight and Obese MothersDocument8 pagesExperiences and Perspectives About Breastfeeding in "Public": A Qualitative Exploration Among Normal-Weight and Obese MothersNoella BezzinaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Knowledge and Practice of Exclusive BreastfeedingDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Knowledge and Practice of Exclusive Breastfeedingc5rh6ras100% (1)

- Research Paper On Exclusive BreastfeedingDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Exclusive Breastfeedingmadywedykul2100% (1)

- Breastfeeding Thesis PaperDocument4 pagesBreastfeeding Thesis PaperBestCustomPaperWritingServiceCanada100% (2)

- Chen 2015Document9 pagesChen 2015Beatriz A GálvezNo ratings yet

- Zainab ProjectDocument35 pagesZainab ProjectOpeyemi JamalNo ratings yet

- Effect of Natural-Feeding Education On Successful Exclusive Breast-Feeding and Breast-Feeding Self-Efficacy of Low-Birth-Weight InfantsDocument9 pagesEffect of Natural-Feeding Education On Successful Exclusive Breast-Feeding and Breast-Feeding Self-Efficacy of Low-Birth-Weight InfantsDiana RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Nursing Research PaperDocument14 pagesNursing Research Paperapi-735739064No ratings yet

- Han Book 2009 FinalDocument61 pagesHan Book 2009 FinalTimothy JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Book 1Document1 pageBook 1Timothy JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Biol 366 Asterids 3 TextDocument36 pagesBiol 366 Asterids 3 TextTimothy JohnsonNo ratings yet

- BrassicaceaeDocument18 pagesBrassicaceaeTimothy JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual Toad DissectionDocument5 pagesLab Manual Toad DissectionDegorio, Jay Anthony G. 11 - QuartzNo ratings yet

- EPP201 Pass Paper Revision Questions 1Document9 pagesEPP201 Pass Paper Revision Questions 1Boey Keen HuangNo ratings yet

- Land Rover Discovery SportDocument2 pagesLand Rover Discovery SportnikdianaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 17 Plane Motion of Rigid Bodies: Energy and Momentum MethodsDocument11 pagesChapter 17 Plane Motion of Rigid Bodies: Energy and Momentum MethodsAnonymous ANo ratings yet

- GEV Organic ProductsDocument4 pagesGEV Organic ProductssubhashNo ratings yet

- Autoclaved Aerated ConcreteDocument4 pagesAutoclaved Aerated ConcreteArunima DineshNo ratings yet

- Garmin 530W QuickReferenceGuideDocument24 pagesGarmin 530W QuickReferenceGuideLuchohueyNo ratings yet

- Enter Your Response (As An Integer) Using The Virtual Keyboard in The Box Provided BelowDocument102 pagesEnter Your Response (As An Integer) Using The Virtual Keyboard in The Box Provided BelowCharlie GoyalNo ratings yet

- Spectrophotometer UseDocument4 pagesSpectrophotometer UseEsperanza Fernández MuñozNo ratings yet

- Matanglawin: The Philippines Growing Plastic ProblemDocument8 pagesMatanglawin: The Philippines Growing Plastic ProblemChelsea Marie CastilloNo ratings yet

- Note 2Document11 pagesNote 2Taqiben YeamenNo ratings yet

- كيفية التفكير المعماري- د.إبراهيم رزقDocument38 pagesكيفية التفكير المعماري- د.إبراهيم رزقAhmed HusseinNo ratings yet

- Feynman R Lectures in Physics Electromagnetism Greek PDF TorrentDocument2 pagesFeynman R Lectures in Physics Electromagnetism Greek PDF TorrentCynthia0% (1)

- Warning: No Smoking! No Open Flame! While Installing Your Jet KitDocument2 pagesWarning: No Smoking! No Open Flame! While Installing Your Jet KitBrad MonkNo ratings yet

- NCR 7403 Uzivatelska PriruckaDocument149 pagesNCR 7403 Uzivatelska Priruckadukindonutz123No ratings yet

- Model Based Control Design: Alf IsakssonDocument17 pagesModel Based Control Design: Alf IsakssonSertug BaşarNo ratings yet

- Stone ColumnsDocument30 pagesStone ColumnsSrinivasa Bull67% (6)

- List of Map Items Class X 2017-18Document3 pagesList of Map Items Class X 2017-18Mayank GhatpandeNo ratings yet

- Murray Thomson Thesis HandbookDocument257 pagesMurray Thomson Thesis HandbookSherif Mohamed KhattabNo ratings yet

- CulturalDocument11 pagesCulturalasddsaNo ratings yet

- Reading Passage 1: IELTS Practice Tests PlusDocument16 pagesReading Passage 1: IELTS Practice Tests PlusNguyen Lan AnhNo ratings yet

- 9th Science EM WWW - Tntextbooks.inDocument328 pages9th Science EM WWW - Tntextbooks.inMohamed aslamNo ratings yet

- Manual Reductor SumitomoDocument11 pagesManual Reductor SumitomoPhilip WalkerNo ratings yet

- Takeoff and Landing PerformanceDocument177 pagesTakeoff and Landing PerformanceАндрей ЛубяницкийNo ratings yet

- Jay Orear - Notes On Statistics For Physicists PDFDocument49 pagesJay Orear - Notes On Statistics For Physicists PDFdelenda3No ratings yet

- Hyundai R220LC-9SDocument185 pagesHyundai R220LC-9Sazze bouz100% (10)

- State Map TSP Kayin MIMU696v03 09sep2016 ENG A3Document1 pageState Map TSP Kayin MIMU696v03 09sep2016 ENG A3Naing SoeNo ratings yet

- 1976 - Susan Leigh Star - LeighDocument3 pages1976 - Susan Leigh Star - LeighEmailton Fonseca Dias100% (1)