Professional Documents

Culture Documents

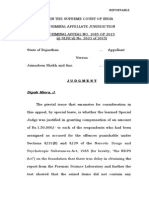

Investigation Having Case Laws

Investigation Having Case Laws

Uploaded by

Shristi DeyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Investigation Having Case Laws

Investigation Having Case Laws

Uploaded by

Shristi DeyCopyright:

Available Formats

7

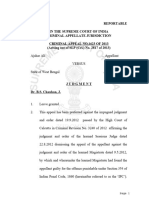

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE

KN. Chandrasekharan Pillai *

IN THE survey year a large number of decisions on different aspects of criminal

procedure have been handed down by the various High Courts and the Supreme

Court. Some decisions which the author considers very important alone have

been surveyed here. As usual for facilitating easy and speedy reference, the

cases have been dealt with under some general topics.

I WORKING OF FUNCTIONARIES IN CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

The higher judiciary have had occasions to criticise the role of different

functionaries in the criminal justice system. For example, both the sessions

judges and senior police officers were criticised by the Madhya Pradesh High

Court in State of M.P. v. Gyan1 wherein two accused charged with murder

were granted anticipatory bail on the plea of suffering from hypertension. The

court was so unhappy that it went on record, "Indeed this court thinks that

there are sufficient reasons to doubt the honesty and integrity of the... Sessions

Judge."2

About the non-cooperation of the police, the court lamented:3

This Court would hope that someone responsible for administering this

State would find time to look into this matter and take remedial

measures. This court would also hope that the authority looking into

this matter also notices that large number of cases remain pending in

this Court only because of this non-cooperation. This Court would like

these sentiments of this Court to be read and appreciated by citizens

to voice their concern in the matter. It should be appreciated that this

Court is not responsible for all the delays nor is it responsible for

mounting arrrears of cases in this Court and these problems would not

be solved so long as police officials do not change their attitude.

There were instances where police atrocities came to light and the appellate

court could not convict the accused for serious offences for want of cogent

* Professor, Department of Law, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Kochi.

1 1992CriLJ 192.

2 Id. at 195.

3 Id. at 193.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

110 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

evidence.4 In one case the public was responsible for the destruction of police

station and the records of the case.

In Golaka Chandra Jena v. Director General of Police5 the dependants of

the victims of police atrocities were awarded a compensation of Rs. 30,000/-

by the Orissa High Court. The court's response may have some positive impact

as the state may require the police to act lawfully.

Role of the courts

The higher judiciary commented adversely upon the attitude of some trial

courts for not punishing the offenders and for not playing the role that has been

assigned to them under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (Code). In State

of Karnataka v. Shivappa? the court did not punish the offender though he was

found to be guilty of bribery. The Karnataka High Court warned:7

The viewpoint of the.... Sessions Judge that a conviction was for some

reason not merited despite a finding to the contrary by him, indicates

a tendency to run away from responsibility and we would say, of a

duty that rested on him in dealing with white collar culprits. We do

hope that the... Judge will not be guilty of such remissness again.

The Orissa High Court reminded the trial courts that they have a role to

bring out the truth in criminal trials. In a case8 where the trial court recorded an

acquittal as the prosecutor chose not to summon the investigating officer and

the informant, the court pointing out that section 165 of the Evidence Act,

1872 and section 311 of the Code act as complementary to each other, said:9

The Court has a duty to see that due to inept handling of the Prosecutor,

a guilty person does not go unpunished, or an innocent gets punished.

It is strange that counsel for State declined to examine as many as six

witnesses including the Investigating Officer and the informant, merely

because two other witnesses had stated something about the alleged

acts of the accused persons.

II INVESTIGATION

Arrest

In Kultej Singh v. C.I. of Police,10 the Karnataka High Court ruled that the

plea of the police that their keeping the arrested for one day in the lock-up

4 See State v Balakrishnan, 1992 Cri U 1872, Sham Kant v. State of Maharashtra, 1992 Cri U

3243. In the latter case the public was responsible for the destruction of police station and

consequently the records of the case.

5 1992 Cn LJ 2901.

6 1992 Cri LJ 3264.

7 Id. at 3272

8 Nilamani Das v, Bhikan Nayak, 1992 Cri LJ 2242.

9 Ibid

10 1992 Cri LJ 1173

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVffl] Criminal Procedure 111

before he was produced before the magistrate would amount to arrest could not

be accepted in the view of section 57 read with section 46.

It has been ruled by the Madras High Court in Krishna Swamy v. Inspector

ofPolice,11 that if the accused is not released on bail under section 167(2), the

magistrate may pass an order of remand under section 309(2) of the Code.

Such an order of remand will not be invalid for the reason of the accused

having not been released on bail under section 167(2) and the charge sheet has

not been submitted within the period of 90/60 days as prescribed therein.

Whether non-availability of police for escort constituted a valid ground for

extending the period of remand of an accused under section 167(2) was answered

by the Andhra Pradesh High Court in Kurra Dasradha Ramaiah thus:12

Whenever it is not possible to produce an accused before the Magistrate,

the concerned Investigating Officer or any other responsible police

officer in charge of the case or the jail Superintendent shall file a

detailed report before the Magistrate explaining the circumstances under

which it was not possible to produce the accused on that particular

day. If the Magistrate is satisfied after going through the report, he

may dispense with the production of the accused and pass appropriate

orders under section 167... as to the detention of the accused. The

Magistrate should not pass an order in this regard mechanically in a

routine manner; the order should be a well considered reasoned one.

The court also deprecated the practice of applying for bail to a court by

suppressing the pendency of earlier application. The court said:13

Filing of bail application simultaneously in different courts may lead

to passing of conflicting orders. As a matter of practice, we direct that

no bail application shall be filed in any court when application already

filed in another court is still pending. In every application for

enlargement on bail there should be specific mention that no other

application for bail is pending in any other court.

In view of the explicit language of section section 167(2)(b)14 it is not

known how this ruling would be looked upon by other High Courts.

In Chamanlal Jain v. State15 the Rajasthan High Court ruled that its inherent

power could not be invoked to redress grievance of the accused that he was

remanded by the trial court under the Terrorists and Disruptive Activities Act

1985 (TADA) without perusing the connected records. The accused could seek

redressal of grievances only from the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court in C.B.I, Special Investigation Cell v. Anupam J.

11 1992 Cri LJ 2998.

12 1992 Cri LJ 3485 at 3501.

13 Ibid,

14 S. 167 (2) (b) lays down, "No Magistrate shall authorise detention in any custody under this

section unless the accused is produced before him". Also see XXIII ASIL 271-72 (1987).

15 1992 Cri LJ 955.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

112 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

Kulkarni,16 has held that custody after the expiry of the first 15 days can only

be judicial custody during the rest of the periods of 90 days or 60 days and that

police custody if found necessary can be ordered only during the first period of

15 days. However, if the accused is involved in another case, he can be

rearrested and remanded to police custody with the permission of the magistrate.17

What amounts to first information report (FIR)

In Jagdish v. State of M.P.X% the question was whether the statement that

asked the circle inspector to rush to the place of occurrence constituted FIR.

The Madhya Pradesh High Court responded to this question by pointing out

that it was only if the object was to narrate the circumstances of a crime, with

a view that the receiving police officer might proceed to investigate thereon,

that the message would be FIR.19

The Punjab and Haryana High Court also had an occasion to deal with this

question in Ram Singh v. State of Punjab wherein the court said:20

The first information or first information report though not mentioned

in the Code anywhere, yet it has always been understood to mean the

first information in point of time received by the police for purposes

of conducting the investigation.

The court has therefore ruled out the possibility of having more than one

FIR in a case.

First information and quashing of FIR

Time and again it has been held not only by the Supreme Court but also by

the High Courts in the country that investigation is within the exclusive territory

earmarked for the police and that their activities should not be interfered with

or without sufficient reasons. It has also been said that if the citizens approach

the police with complaints they cannot refuse to register cases on flimsy grounds.

In State of Haryana v. BhajanlaP1 the Supreme Court reiterated the above

views and said that since the word 'information' under section 154 is not

qualified as 'reasonable' on information given, it is the duty of the police

under that provision to register and then under section 156(1) to investigate.

They should have reasons to suspect the commission of crime. Quashing of

investigation should not be resorted to.

These views are in one form or another echoed in Munnalal v. State of

HP.,22 Hasan Alikhan v. State23 Mrs. Rita Wilson v. State of HP.24 In Rajeshwar

16 1992 C n U 2768

17 See discussions of the court in 1992 Cn LJ 2768 at 2776 quoting Dharampal's case, 1982 Cn

U 1103

18 1992 Cn U 981

19 Id. at 984

20 1992 Cn U 805 at 809

21 1992 Cn U 527

22 1992 C n U 1558

23 1992 C n U 1828.

24 1992 Cn U 2400

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVIII] Criminal Procedure 113

v. State25 the Madras High Court held that a sub-inspector can be both a first

informant and investigating officer.

In Jayantibhai Lalubhai Patel v. State of Gujarat26 it has been ruled that a

FIR sent to a magistrate under section 157(1) is a public document under

section 74, Evidence Act, 1872.

In Buteswar Singh v. State of Bihar21 the Patna High Court has said that the

magistrate mentioned under section 156(3) is judicial magistrate. It has also

been said that under section 157(1) FIR should be promptly sent to the judicial

magistrate.

In Seraj Aslam v. State of U.P.1% the Allahabad High Court reiterated that

the power under section 156(3) should be exercised judicially. A judicial officer

not intending to exercise this power in a particular case has to give reasons for

his conclusion.

It has also been held by the Karnataka High Court that the power under

section 156(3) to order investigation cannot be exercised after taking cognizance

of the offence on the complaint of the complainant under section 200. Order

under the provision is a precognizance order.29

Further investigation under section 173(8)

In Jayant Vitamins Ltd. v. Chaitanyakumar30 the Supreme Court has held

that investigation into an offence is a statutory function of the police and the

superintendence thereof is vested in the state government. The court may not

be justified in interfering with investigation without any compelling reason.

This view of the government's power has been reiterated by the Allahabad

High Court which in Zutfiqur Beg alias Baby v. State of U.P. said:31

Upto the stage of submission of a charge-sheet final report in the case

by the police under section 173 of the Code, the executive wing of

the State Government has full power and control over the investigation

of the case.

Purpose of test indentiflcation parade (TIP)

The objective of TIP came to be discussed by the Madhya Pradesh High

Court in Khalak Singh v. State of M.P., thus:32

The purpose of TIP is to test the statement of the witness made in the

Court, which constitutes substantive evidence, it being the safe rule

that the sworn testimony of the witness in Court as to the identity of

the accused requires corroboration in the form of an earlier identification

proceedings. Such parades, which belong to the investigation stage,

25 1992 Cri U 661.

26 1992 Cri U 2377.

27 1992 Cri U 2122.

28 1992 Cri LJ 2244.

29 1992 Cri U 2897.

30 1992 (4) SCC 15.

31 1992 Cri U 2067 at 2070-71.

32 1992 Cri U 1150 at 1154.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

114 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

serve to prove the authority with material to assume themselves if the

investigation is proceeding on right lines and therefore it is desirable

to hold them at the earliest opportunity. A further reason is that an

early opportunity to identify also tends to minimize the chances of the

memory of the identifying witnesses fading away due to long lapse of

time.

Counsel's presence during interrogation

In Poolpandi v. Superintendent, Central Excise33 the question whether the

person questioned under the Customs Act, 1962 or Foreign Exchange Regulation

Act, 1973 is entitled for lawyer's presence at the time of questioning was

answered in the negative by the Supreme Court.

In Sundaram v. Director, C.B.I., Madras,34 the Madras High Court has also

held that in the context of TADA, the offenders were not entitled to have an

interview with their advocate either under section 303 or under section 482.

Statement under section 164

In Ramchit Rajbhar v. State of West Bengal, the general purpose of recording

a statement under section 164 has been summed up by the court thus:35

The general purpose of recording such a statement of a witness is to

fix him to it when it is feared that he may resile afterwards or may

be tampered with. There is another purpose for recording the statement

under section 164. Statements made soon after the incident are far

more trustworthy than later denials or embellishments. Such statements

are admissible in evidence and presumption of genuineness under section

80 of the Evidence Act attaches to such statements. However, a

statement recorded under section 164 can never be used as substantive

evidence of truth of the facts but it may be used for the purpose of

contradiction or corroboration of the witness who made it, as per

provisions of sections 145 and 157 of the Evidence Act.

In Ambika Prasad v. State of U.P.,36 the Allahabad High Court clarified

that committal by a magistrate, who recorded statement under section 164,

may not be bad under section 479 as he is connected with it only in a public

capacity. Moreover in committal proceedings no question of law is decided.

It has been ruled by the Orissa High Court in Dhaneshwar Mallick v. State

of Orissa37 that refusal by a magistrate to record statement of witnesses under

section 164 does not affect fair trial. It is purely discretionary for the magistrate

to record statements of witnesses under this provision.

The Andhra Pradesh High Court in NS.R. Krishna Prasad v. Directorate of

33 1992 Cri U 2761.

34 1992 Cri U 3136.

35 1992 Cri U 372 at 378.

36 1992 Cri U 1478.

37 1992 Cri LJ 1711.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVni] Criminal Procedure 115

Enforcement, New Delhi3* has stated that the requirement of administering

caution under section 164(2) while recording statement is applicable in recording

statement under section 108, Customs Act also.

High Court has power to order investigation

The High Courts have also been exercising their writ jurisdiction to order

inquiry/investigation. The Kerala High Court in Sarojini Ammal v. Union of

India has identified the contingencies when it may be proper for it to order

enquiry/investigation:39

If the Court feels that the police failed in its statutory duty or basic

trust or that consideration of larger social justice requires it, it will

exercise its jurisdiction under Article 226 and issue a direction to cause

an investigation. But this is not a matter of right in a party nor a

matter for indulgence in favour of a party. Institutional perspectives

and sound considerations of policy should prevail in this area. A party

cannot choose his investigator or judge....

Dying declaration recorded by police officer in the presence of doctor admissible

In Thakur Das v. State of H.P.40 the Himachal Pradesh High Court ruled

that there was no prohibition against recording of dying declaration by police

officer. The mode of recording other than by way of question-answer is also

not material according to the court.

Impact of section 167(5) on a summons case beyond six months

In State of Punjab v. Amar Singh,41 the Punjab and Haryana High Court

held that the evidence collected during the investigation beyond the period of

six months would be rendered inadmissible by the provisions and not the

evidence which was collected earlier by an investigation.

Bail under the proviso to section 167(2)

The question whether there is right to bail under section 167(2) proviso in

the sense that if the prosecution failed to submit the charge sheet within 90

days, the accused should be released on bail, has been answered in the negative

by the Allahabad High Court in Hariom v. State of UP.42 The court found

support for its view in Lakhmanbhai Pancholi v. State of Gujarat.43

The Bombay High Court in Abdul Wahid v. State of Maharashtra,44 held

that a person should seek bail under the proviso to section 167(2) before the

submission of charge sheet.

38 1992 Cri LJ 1888.

39 1992 Cri LJ 3110 at 3114; see also Sri Pranab Jyothi Gogoi v. State of Assam, 1992 Cri U 154.

40 1992 Cri U 2415.

41 1992 Cri U 1000.

42 1992 Cri U 182; also see Shankar alias Gouri Shankar v. State of Tamil Nadu, 1991 Cri U

1745.

43 1990 Cri U 1275,

44 1992 Cri U 1900.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

116 Annual Survey of Indian Law [ 1992

In Srisivanna v. State of Karnataka,45 the Karnataka High Court said that if

the 90th day happened to be a holiday and the state failed to file the report on

that day, the accused is entitled to claim bail on the next day under the proviso.

Another interesting question in this connection that arose before the Madhya

Pradesh High Court in Devendrakumar v. State of M.P.46 was whether the

period of 90 days for the purpose of applying the proviso could include the

period of bail granted under section 439. The court answered it in the negative

as the accused was not subject to the disabilities attendant with incarceration

during that period.

Impact of submission of charge sheet.

The Orissa High Court ruled47 that submission of charge sheet may make

the court to cancel bail granted under this provision.

However, the Andhra Pradesh High Court in Madaba Ramaiah v. State of

Andhra Pradesh4* did not accept this view. In this case the court set aside the

cancellation of bail ordered by the magistrate on the ground that the charge

sheet was filed on the 91st day on which date he was granted bail. The court

stated:49

When an accused person is released on the ground that the charge

sheet has not been filed, the Court has no power to correct it under

section 362... on the ground that there was some defect in granting

bail. There is no provision in the Code for cancellation of bail in the

case of persons that were released under the proviso to sub-section (2)... .

The Supreme Court has in Aslam Babulal Desai v. State of Maharashtra50

declared that mere submission of charge sheet cannot be a ground for

cancellation of bail granted under the proviso. The court clarified:51

We are, therefore, of the view that once an accused is released on bail

under section 167 (2) he cannot be taken back in custody merely on

the filing of a charge sheet but there must exist special reasons for so

doing besides the fact that the charge sheet reveals the commission of

a non-bailable crime. The ratio of Rajnikant case to the extent it is

inconsistent herewith does not, with respect, state the law correctly.

The court reasoned the above conclusion thus:52

The delay in completion of the investigation can be on pain of the

accused being released on bail. The prosecution cannot be allowed to

45 1992 Cri U 2287.

46 1992 Cri U 1730.

47 Sanatan Sahu v. State of Orissa, 1992 Cri LJ 352.

48 1992 Cri U 676.

49 Id. at 678.

50 1992 (4) SCC 272.

51 Id. at 291.

52 Ibid.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVIII] Criminal Procedure 117

trifle with individual liberty if it does not take its task seriously and

does not complete it within the time allowed by law. It would also

result in avoidable difficulty to the accused if the latter is asked to

secure a surety and a few days later be placed behind the bars at the

sweet will of the prosecution on production of a charge sheet.

The law on this point thus seems to have been straightened by this decision.

Ill INITIATION OF CRIMINAL PROCEEDING

Cognizance order on material other than police report

It has been held by the Orissa High Court in Mohamed Jakaullah v. Noor

Mohamed Khan53 that when the magistrate based his cognizance order on the

material in the protest petition and case diary and not merely on the statement

of witnesses recorded under section 164, the cognizance is treated to have been

taken on police report under section 190(l)(b) rather than under section

190(l)(a).

The Orissa High Court in Pitambar Buhan v. State54 has stated that taking

cognizance includes intention of initiating a judicial proceeding against an

offender in respect of an offence or taking steps to see whether there is basis

for initiating judicial proceeding.

In Venkatesh Narayanappa v. Sri Vittal55 the Karnataka High Court opined

that a magistrate's taking cognizance on a police report after keeping silence

on it for more than six months and taking sworn statement of the complainant

was proper.

The magistrate's power to take cognizance ignoring police report has also

been reiterated in Jagannath Das v. State,56 by the Orissa High Court.

Prosecution of offences against public justice without sanction from concerned courts

In Sardul Singh v. State of Haryana,51 and Shiv Prasad Paliwal v. State of

Rajasthan5% it has been pointed out that initiation of criminal proceedings

against those accused of having committed offences in proceedings in the

courts, should be done on the complaint of the concerned court. The Punjab

and Haryana High Court said:59

The reading of the above referred provision of section 195 coupled

with the procedure prescribed in section 340... absolutely leave no

doubt that not only cognizance of such offences without the complaint

in writing of court concerned is barred but also the investigation into

such offences because that will amount to taking over the function of

53 1992 Cri U 4022.

54 1992 Cri U 645.

55 1992 Cri U 586.

56 1992 Cri LJ 2204.

57 1992 Cri U 354.

58 1992 Cri U 357.

59 Id. at 356.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

118 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

the court, where forgery was committed, by the investigating agency

which is against the mandate of section 340... .

In the latter case the Rajasthan High Court said that in making the complaint

the court need not go by the language of section 340 if it is clear that it is in

the interest of justice that the court was initiating criminal proceedings.

The Bombay High Court in Godrej and Boyce Manufacturing Co. Ltd. v.

Union of India60 has stated that the magistrate can proceed directly under

section 343 as if in a case instituted on police report.

Requirement of sanction

In some cases the importance of requirement of sanction to prosecute has

been stressed by the courts. The tendency of the prosecution to avoid the

requirement of sanction also came for criticism.61

The rationale for this requirement has been expressed by the Madras High

Court in M.S. Kuppuswamy v. State,62 thus:

The purpose of sanction being vested in a departmental authority is to

provide an opportunity for assessment and weighing of the accusation

in a dispassionate and responsible manner. Such an approach in the

matter of according sanction must be apparent on the face of the record.

It will be appropriate, that the order of sanction reflects the

understanding of the facts by the sanctioning authority in his own way

not being put into a straight-jacket of repeating the facts put forth by

the Investigating Agency. Sanction to prosecute must have sanctity

attached to it, for the liberty of the person prosecuted is involved.

Initiation of action against additional accused

In Atibal Singh v. State of M. P.63 the Madhya Pradesh High Court has

ruled that a sessions court can summon additional accused even before an

inquiry or trial. The court said:64

The Court of Sessions prior to the framing of charge, can, without its

recording evidence, summon a person as an additional accused on the

basis of the document in the final report of the investigating officer

under section 173 independently of the provisions of section 319, as

has been held in the Patna Full Bench case of Latfur Rehman with

which I am in respectful agreement.

The court has pointed out that the magistrate is also entitled to do so but his

60 1992 Cri LJ 3752.

61 See Mohan Tiwari v. Arunachal Pradesh, 1992 Cri LJ 737; Ram Adhar Yadav v. Ramchandra

Misra, 1992 Cri LJ 2216; Soumyndra Narain Choudhury v. State, 1992 Cri LJ 1472;

Prakashchandra Jaiswal v. State of V.P., 1992 Cri LJ 1590.

62 1992 Cri LJ 56 at 70.

63 1992 Cri LJ 3209.

64 Id at 3214.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVIII] Criminal Procedure 119

power is incidental to taking cognizance under section 190 and not under

section 319.

AH witnesses need not be examined in enquiry on complaint

It has been reiterated by the Orissa High Court in Rabindra Prasad Sing v.

Smt Lili Bala Sing,65 that in an inquiry under section 202 it is for the complainant

to limit the number of witnesses to be examined.

Rejecting an argument that the criminal courts should not take cognizance

of an offence under section 138 of Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 and

section 420, Indian Penal Code, 1860, (IPC) the Bombay High Court in

Pawankumar v. Ashish Enterprises, said:66

There is nothing in law to prevent the criminal courts from taking

cognizance of the offence, provided the elements of an offence are

made out on the face of the complaint-petition itself, merely because

on the same facts, the persons concerned might be also subjected to

civil liability... . If the allegations disclose a criminal offence, the

complaint ought not be dismissed even if civil remedy is obtainable.

That there is no possibility of conviction is no ground for dismissal.

I . KM. Mathew v. State of Kerala,61 the Supreme Court has ruled that a

magistrate can discharge a person on his appearance in the court when there

are no specific allegations made on the complaint against him. The court's

observations are pertinent:6*1

It is open to the accused to plead before the magistrate that the process

against him ought not to have been issued. The magistrate may drop

the proceedings if he is satisfied on reconsideration of the complaint

that there is no offence for which the accused could be tried. It is his

judicial discretion. No specific provision is required for the magistrate

to drop the proceedings or rescind the process.

In Rakesh Kumar v. State of Punjab69 involving trial of offences under

section 498A IPC, it was held by the Punjab and Haryana High Court that

since stridhan (dowry) was given at Ludhiana and the consequences arose also

at Ludhiana, the Ludhiana courts will have jurisdiction.

IV BAIL

Considerations in granting bail

While the delay in the proceedings has indeed influenced the courts in

granting bail in Virsa Singh v. State through C.B.I.,10 Jai Singh v. State of

65 1992 Cri U 1716; see also Dinabandu Das v. Balakrishna Das, 1991 Cri LJ 3273.

66 1992 Cri U 1619 at 1629.

67 1992 Cri LJ 377 ft

68 Id. at 3780.

69 1992 Cri LJ 1815.

70 1992 Cri U 164.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

120 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

Rajasthan,11 Mohamad Yusuf Ali v. Asst. Collector of Customs12 it has been

declared by the courts that filing of nomination papers73 for Lok Sabha elections

or affliction with cardiac disease74 may not be considerations for granting bail.

The Orissa High Court in Biswanath Bapat v. Sanjay Saha15 has reiterated that

the court can grant bail only when the accused surrenders to the court. The

Rajasthan High Court's concern76 in the trial courts' apathy in dealing with bail

applications may be shared by all. It was observed:77

It is really disturbing that the trial courts are so unaware of liberties

of the citizens. Now, it is settled proposition of law that expeditious

criminal trial is a fundamental right of the accused, especially when

he is in jail. No accused can be kept in jail for uncertain period, as

an undertrial prisoner, especially when there is no fault on his part.

Bail granted by police

An interesting question arose in Haji Mohamed Wasim v. State of U.P.n

before the Allahabad High Court as to the validity of bail granted by police

officers. In this case the accused who was on bail granted by police preferred

not to appear before the court. The trial court issued a non-bailable warrant

which came to be challenged by the accused under section 482. The court

ruled that he has to take fresh bail from the trial court. It reasoned:79

My conclusion on consideration of different provisions as discussed

earlier, is that the power of a police officer in-charge of a police station

to grant bail and the bail granted by him comes to an end with the

conclusion of the investigation except in cases where the sufficient

evidence is only that of a bailable offence, in which eventuality he can

take security for appearance of the accused before the magistrate on

a day fixed or from day to day until otherwise directed. No parity can

be claimed with an order passed by magistrate in view of enabling

provision contained in clause (b) of section 209... under which the

committal Magistrate has been empowered to grant bail until conclusion

of trial, which power was otherwise restricted to grant of bail by him

during pendency of committal proceedings under clause (a) of section

209... .

In Nazeem v. Asst. Collector, Customs,™ it has been ruled by the Bombay

High Court that even after a bail application is disposed of on merits, it is

71 1992 Cri LJ 2873.

72 1992 Cri LJ 3285.

73 Donthi Reddy Chinna Gangireddy v. State ofA.P.t 1992 Cri LJ 1049.

74 Venkataramanappa v. State of Karnataka, 1992 Cri LJ 2268.

75 1992 Cri LJ 3105.

76 Supra note 71.

77 Id. at 2895.

78 1992 Cri U 1299, see also Morit Malhotra v. State of Rajasthan, 1991 Cri U 806.

79 Id at 1302.

80 1992 Cn LJ 390.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVIII] Criminal Procedure 121

permissible for the party once again to present another application for a

reconsideration of that order since such orders are interim ones and are capable

of modification.

In Shobha Ram v. State of U.P.™ another question was raised. After bail

application of the accused was rejected, a co-accused was granted bail by a

judge. So the applicant made a second application on the ground that on

identical facts a co-accused was granted bail. He was granted bail. This came

to be challenged on the ground that the applicant did not let the judge know

that his first application for bail was rejected and hence there was no parity in

rejection of bail application. The court responded:82

The contention by the... counsel of the applicant that there could be

no parity in rejection of bail application appears to have much force.

The reason for it is that when the bail application of one co-accused

is rejected on merits, the other co-accused who is not a party to that

bail application, had no opportunity to make his submissions before

the Court. It is only when he moves his bail application that he can

make his association, which are to be heard and decided on merits by

this court. So it cannot be said that his bail application would be liable

to be rejected merely because the bail application of other co-accused

had been rejected earlier.

The Andhra Pradesh High Court was presented with another question in

Malla Ramarao v. Stated The applicant after the rejection of his application

for bail twice by the sessions court and once by the High Court approached the

High Court again.The High Court depreciated this kind of application as both

the sessions court and the High Court have concurrent jurisdiction. The court

pointed out:84

The moment he filed an application and the same has been disposed

of either in his favour or against him, indicates that the petitioner or

petitioners are aware of the accusation that has been levelled against

them. When he is aware of the accusation levelled against him and the

court passed an appropriate order rejecting his application, as a dutiful

citizen he is bound to surrender before the concerned police.

Bail to drug offenders

The question whether the discretion of the court to grant bail under section

439 was curtailed by section 37 of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic

Substances Act, 1985 (NDPS Act) has been answered in the affirmative by the

Karnataka High Court in Shankar Krishnara Habib v. State of Karnataka}5

The court reasoned:

81 1992 Cri LJ 1371.

82 Id. at 1372.

J8T3 1992 Cri U 2208.

84 Id. at 2209.

85 1992 Cri U 205 at 213.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

122 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

What the NDPS Act says is that a person accused of an offence

punishable for imprisonment for a term of 5 years or more his request

will be considered only when the Public Prosecutor has an opportunity

to oppose such an application and secondly when the Public Prosecutor

opposes such an application the court is satisfied that on the material

collected there are reasonable grounds to believe that the person against

whom accusation is made is not guilty of such offence and thirdly in

case of release he is not likely to commit any offence.

The court, however, gave a ruling in Smt. Kamalabai v. State of Karnataka*6

that the High Court's power under section 439 is not affected by the provisions

of the NDPS Act.

It was held in Shokat All v. State of Rajasthan*1 that a juvenile accused

under the NDPS Act could be granted bail also by sessions/High Courts.

The Madras High Court in Superintendent, Narcotics Control Bureau, South

Zone, Madras v. Selvaraju has said that section 37 of the NDPS Act has

overriding effect. It is pertinent to note that the Madras High Court89 invoked

constitutional provisions under article 227 to grant bail to a person accused

under the Terrorists and Disruptive Activities Act as other provisions including

section 482 in the Code were excluded from operation.

In Asst. Collector of Customs, Bombay v. Madam Ayabo Atendam it was

declared by the Bombay High Court that the bail order passed prior to submission

of charge sheet would be operative till the submission of the charge sheet only

and after that a de novo consideration whether to grant bail or not would have

to be taken.

Cash security

The insistence for high cash security for bail came for drastic criticism by

the Karnataka High Court thus:91

In the case on hand, the present approach of the... Sessions Judge in

insisting upon the petitioner to deposit a cash security of Rs. 750/- in

each case totalling Rs. 6750/- is not only harsh and oppressive but

indirectly denial of bail thus depriving the person his individual liberty.

It has also been ruled by the Bombay High Court in Rajeev Bhatia v.

Abdulla Mohamed Gani,n that in customs cases where the accused has exercised

an option of furnishing cash bail and desired thereafter to change over to the

security of a surety, the customs authorities have no right to object to the

refund of the cash amount pending the trial.

86 1992 Cri U 561.

87 1992 Cri U 1335.

88 1992 Cri LJ 2143.

89 D. Veerasekaran v. State of Tamil Nadu, 1992 Cri LJ 2168.

90 1992 Cri LJ 2349

91 Afsarkhan v. State by Girija Nagar Police, 1992 Cri U 1676.

92 1992 Cri U 2092.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVIII] Criminal Procedure 123

Requirement of hearing of prosecution before granting bail

The Karnataka High Court responding to the statutory requirement of hearing

the prosecutor under section 104D of the Karnataka Forest Act, 1964 before

the accused is granted bail observed:93

I even go to the extent of observing that the interest of the State and

the interest of the accused have been properly balanced inasmuch as

the right to move the Court for release on bail is conceded to the

accused on the one hand and at the same time right of the prosecution

to state its case against release of the accused on bail is recognized

by the legislature. I therefore, hold that section 104-D... is constitutional

and valid.

In State of Karnataka v Chinnavasappa s/o Hanumanthappa9A it was held

unless the civil judge and first class magistrate was appointed additional sessions

judge under section 9 of the Code, he would not have jurisdiction to grant bail

in a case coming under the jurisdiction of the sessions court during his temporary

holding charge of the latter.

Cancellation of bail

Generally speaking, the courts do not seem to be inclined to cancel bail

once granted. This trend is in consonance with the Supreme Court rulings on

the subject.

While in Brijeshwar Dayal Verma v. State of U.P.,95 the Allahabad High

Court cancelled the bail on the ground that the accused got bail on

misrepresentation of facts, the application for cancelling the bail in State of

Maharashtra v. Kriti Ambani96 was rejected by the Bombay High Court saying

that there was no evidence that the accused was not cooperating with

investigators. The Orissa High Court in State of Orissa v. Jagannath Patel,91

also refused to cancel the bail in a dowry death case. However, the same High

Court in Gurumurti Digal v. Ashok Kumar Digal9% cancelled the bail as the

bail granted to him by the sessions court in a case involving rape of a minor

child was not found proper.

The Delhi High Court in Tilak Raj Kohli v. Devendra Kumar99 reiterated

that for cancellation stronger grounds are necessary. It, however, cancelled the

bail in Ashok Kumar v. State,m as the witness on reliance of whose statement

the accused was granted bail had disowned his statement. The court has identified

and discussed the grounds on which cancellation can be ordered.

An unwarranted comment was made by a judge of the Madhya Pradesh

93 Mohamed v State of Karnataka, 1992 Cn LJ 89 at 92

94 1992 C n U 95

95 1992 Cn U 4 1 1

9j6 1992 Cn U 1647

fl 1992CnLJ 1818

98 1992 C n U 1917

99 1992 Cn U 4000

100 1992CrxLJ 3821

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

124 Annual Survey of Indian Law [ 1992

High Court in Vikramjit Singh v. State ofM.P.,m to the effect that persons like

the accused before him should not be granted bail. He, however, ganted bail

since another accused in the case was granted bail by another judge of the

same High Court. Taking the cue the state moved application for cancellation

of bail. On being moved for special leave, the Surepme Court struck down the

order observing:102

It appears that the ... Judge while passing the impugned order, failed

to appreciate that no bench can comment on the functioning of a

coordinate bench of the same court, much less sit in judgment as an

appellate court over its decision. If the State was aggrieved by the

order of bail by Mr. D.C. Verma, it could have approached this court,

but that was not done.

Anticipatory bail

Impropriety of the judicial officers in dealing with bail applications came

to be criticised in NKSM Shahul Hameed v. Mohamed Ibrahim,m in which

even after the arrest and an application for bail the accused were granted

anticipatory bail. The observations are worth quoting:104

If a Magistrate was cocksure of the foundation that the order of Sessions

Judge cannot at all be executed, he ought to have boldly sought for

clarification. The act of... Magistrate in not seeking for such clarification

as well as the act of... Sessions Judge in passing an order granting

anticipatory bail on the admitted factum of arrest of the person accused

of, much earlier to the grant of anticipatory bail, smack of judicial

impropriety in the circumstances of the case. The grant of anticipatory

bail, in such circumstances, would lend a helping hand to the persons

accused during the course of trial to create a cloud of suspicion about

their arrest, confession, consequent discovery of incriminating facts

under section 27 of the Evidence Act etc. and derive maximum benefit

out of it.

While in Baldev v. State,105 and Harshad Mehta v. Union of India,i05a no

anticipatory bail was granted as it would have affected investigation, in Ambalal

Punamchand Rashamwala v. State,1™ anticipatory bail was refused as non-

bailable warrants had already been issued by the concerned court.

The question whether an accused can be given anticipatory bail on

apprehension of arrest for an offence allegedly committed in Madhya Pradesh

by the Kerala High Court was answered in the negative in T. Madhusoodanan

v. Superintendent of Police.m

101 1992 Cri U 5 1 6 .

102 Id. at 517.

103 1992 Cri U 227.

104 Id. at 230.

105 1992 Cri U 1604.

105a 1992 Cri U 4032.

106 1992 Cri LJ 2373.

107 1992 Cri LJ 3472.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVHI] Criminal Procedure 125

It has thus followed its own earlier decision in C.T. Mathew v. Govt of

India, Home Department (CIB).m

In Khimiben v. State of Gujarat,m the Gujarat High Court deprecated the

tendency of granting anticipatory bail to offenders involved in dowry death

cases and ordered cancellation of anticipatory bail. The court, it appears, was

influenced by the Supreme Court ruling in Samunder Singh v. State of Gujarat,110

which stressed the need for caution in granting anticipatory bail to persons

involved in dowry death cases. The Karnataka High Court in State of Karnataka

v. Narayanappa,ui refused to cancel anticipatory bail though it was granted on

improper grounds, as there was no evidence of misusing the freedom by the

accused.

V TRIAL AND TRIAL PROCEDURE

The importance of trial procedure came to be emphasized by the Andhra

Pradesh High Court in R. Venkat Reddy v. State,112 in which in a propsecution

for offence under section 193 IPC, instead of warrant procedure, summons

procedure was followed. The court said:113

Every right of the accused is well knit in the Code of Criminal

Procedure in order to link it with the protection available under Article

21 of the Constitution of India. It is, therefore, mandatory for the courts

to follow meticulously the procedure — either warrant or summons —

prescribed in the Code of Criminal Procedure in trying the accused,

lest it may attract the consequences that flow from violation of the

mandatory procedure prescribed by the law culminating in deprivation

of the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 21... .

The Karnataka High Court has however pointed out in Gurappa

Haramanthappa Bijapur v. State,U4 that adherence to technicalities in matters

which are n6t of vital or important significance in criminal trials may frustrate

the ends of justice.

Non-examination of a witness by prosecution

In Jodha Koda Rabari v. State ofGujarat,u5 the Gujarat High Court pointed

out that if there was some material to indicate that prosecution witness has

been won over by the accused, then the non-examination of that witness by the

prosecution cannot be a matter of criticism.

It has also been held that if a witness makes two inconsistent statements,

and the court is satisfied that the earlier statement was true that would not

m f992CriLJ 1316.

my 1992 Cri LJ 1994.

no

in

1992 Cri U 705.

1992 Cri U 225.

112 1992 Cri U 414.

113 Id. at 417.

114 1992 Cri U 1653.

115 1992 Cri LJ 3298.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

126 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

debar the court from acting on such evidence.

In Kuldip Singh v. State of Punjab,116 the Supreme Court has stated that

when a witness gives one statement at the time of inquest and later in the court

he changes it, the inquest report can be looked into to test the veracity of

statement though inquest report does not constitute evidence.

Examination of accused under section 313

In Kabul alias Khudia v. State of Rajashtan,111 the Rajasthan High Court

has ruled that if no opportunity was given to the accused to explain certain

circumstances, those circumstances should be excluded from evidence.

The importance of section 313 has been emphasized by the Supreme Court

also in Stat€ of Maharashtra v. Sukhdev Singh alias Sukha. The court observed:118

It is trite law that the attention of the accused must be specifically

invited to inculpatory pieces of evidence or circumstances laid on record

with a view to giving him an opportunity to offer an explanation if

he chooses to do so. The section imposes a heavy duty on the court

to take great care to ensure that the incriminating circumstances are

put to the accused and his response solicited.

In Virisingh v. State of U.P.U9 though the accused did not contest the

genuineness of injury report etc. the court subjected them to further scrutiny.

The Allahabad High Court said:120

The mere fact that the genuineness of the injury and the Radiologist's

report was not disputed, does not mean that the jurisdiction of the

court to ascertain the truth and arrive at a correct legal decision, is

ousted.

It has been emphasized by the Karnataka High Court that the accused

should be given opportunity to cross-examine the witnesses.121

Similarly in T.N. Janardhanan Pillai v. State,122 the Kerala High Court also

noted the importance of examination of witnesses by the defence. Indeed, the

court noted that the trial court has discretion to recall witnesses. But once they

have been recalled the defence should be given opportunity to cross-examine

them.

In Nain Singh v. Nain Singh,123 the Jammu and Kashmir High Court said

that in the absence of a request of summoning prosecution witnesses by the

prosecutor in view of section 271 of the Code, there is no obligation on the part

116 1992 Cri LJ 3592

117 1992 C n U 1491

118 1992 (3) SCC 700 at 741.

119 1992 Cri LJ 1383.

120 Id. at 1384.

121 See State of Karnataka v. Dandapam Modahar, 1992 Cri LJ 24.

122 1992 Cri U 436.

123 1992 Cri LJ 2004.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVIII] Criminal Procedure 127

of court to summon them by coercive means.

In Sreedhar Pillay v. P.J. Alexander,124 the Kerala High Court has again

reiterated that the trial court should help the accused to produce material

evidence even in a case where the evidence is strong for the prosecution as

they may help him to rebut the prosecution case.

The decision in Dwarka Prasad v. State ofM.P.125 by the Madhya Pradesh

High Court indicates that if a person gives a statement in trial conflicting with

a statement recorded under section 164, he could be charged for perjury under

section 344. In the instant case the charge was not sustained as the accused did

not get sufficient notice of the gist of the offence.

In Nawal Kishore Shukla v. State of UP.,n6 the Allahabad High Court

opined that a magistrate can examine a witness required by the complainant

though his name does not appear in the original list of witnesses.

In Purushottam Subra v. State of Orissa,121 two important questions arose

as to whether the failure of magistrate to explain particulars of the offence

under section 251 vitiated trial and whether admission of guilt by the accused

when the prosecution report did not make out an offence under a statute would

give the authority to convict the accused. Both were answered in the negative.

In State of Maharashtra v. Sundar P. Lalvani,m the Bombay High Court

reversed the acquittal recorded by the trial court under the Imports and Exports

(Control) Act, 1947 and recorded conviction. On invoking its inherent powers

for review/recall the court responded:129

The Code of Criminal Procedure does not make a provision for any

such procedure, and secondly, even if the inherent powers under section

482... are to be invoked, it would not be open to this court to permit

something thereunder which is specifically prohibited under section

362... .

In Hemantakumar Mohapatra v. Binod Bihar Mohapatra,130 the accused

appeared in court, took bail and his counsel on his behalf cross-examined

witnesses. But instead of his real name, some other name was mentioned in the

charge sheet. The complainant moved the court for correcting the name. But

the trial court rejected the prayer. The Orissa High Court considered it a

clerical error and ruled that there was nothing wrong in the court to make

necessary corrections.131

In Vadla Balaiah v. K Raghavendra Reddy, the Andhra Pradesh High

Court said about the mode of service thus:132

124 1992 Cri LJ 3433.

125 1992 Cri U 2027.

126 1992 Cri U 1554.

127 1992 Cri LJ 1417.

128 1992 Cri U 2015.

129 Id. at 2019.

130 1992 Cri LJ 2183.

131 Id. at 2187.

132 1992 Cri U 4019 at 4020.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

128 Annual Survey of Indian Law [ 1992

The criminal law does not say that in the case of a revision, if service

of notice is not effected on the opposite side, the service has to be

affected in a particular way. In the absence of any procedure prescribed

in this behalf, the only procedure to be followed is by directing the

notices to be published in a local newspaper.

In Guthikonda Srihariprasada Rao v. Guthikonda Lakshmi Rajyma, the

Andhra Pradesh High Court examined the mode of service of summons under

the Code. It was observed:133

Now in the new Code sections 61 and 62... are almost identical to

sections 68 and 69 of the old Code. Here also sections 61 and 62 ...

do not contemplate service of summons through registered post. A

reading of the provisions of the Code clearly indicates that only in the

case of service of summons on witnesses, service by post is

contemplated.

It has been held by the Madras High Court in Vasanthi v. Kamaswami,m

that an acquittal recorded under section 248(1) by a trial court in a case

involving offences under sections 494 and 495 read with section 109 IPC

merely on the ground of absence of complainant was improper. The court

observed that merely because the complainant or her witnesses are not available

for cross-examination under section 246(4) of the Code, the magistrate cannot

record an acquittal under section 248(1) of the Code on the plea that the

complainant had not proved her case.

The courts exempt persons accused of less serious offences from appearing

in the court. In Mangaroo v. State of L/.P.135 rejecting the order of magistrate

cancelling the exemption granted to the accused, the Allahabad High Court

declared:136

If the complainant moves such an application for cancellation of

exemption out of revenge or in order to pressurise the applicant so that

he may lose his job in a foreign country only to face trial which is

not for a very serious offence involving moral turpitude, it would not

be permitted.

Charging

It has been reiterated in serveral cases decided by different High Courts

that at the stage of framing charges, the court is required to evaluate the

material and documents with a view to finding out whether the facts taken at

their face value disclose the existence of the ingredients of the alleged offence.137

133 1992 CrLLJ 1594 at 1595.

134 1992 Cri U 2442.

135 1992 Cri LJ 1397.

136 Id. at 1398.

137 Sumati Vijay Jain v. State ofM.P., 1992 Cri U 97; Sri Sudhirkumar Arya v. State, 1992 Cri LJ

21; S.B.I., Balangir Branch v. Satyanarayana Sarangi, 1992 Cri LJ 2635; and Ramachandra

alias Rama Pandan Sahu v. Niranjan Rout, 1992 Cri LJ 304.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol, XXVIII] Criminal Procedure 129

In State of Karnataka v. Dandapani Modaliar,m the court clarified that the

Code provides for some time to intervene between the date on which the

accused is required to state as to whether he wishes to cross-examine any or all

the witnesses examined by the prosecution before framing charge. Failure to

give this opportunity is not an illegality though.

It has been reiterated by the Rajasthan High Court130 that framing a charge

is an order of moment which takes away a valuable right of the accused to be

discharged. It cannot therefore be an interlocutory order and it should be

revisable. In this connection the Kerala High Court's ruling in NK. Narayanan

v. V.V. Vidyadharan,iA0 surveyed in 1991 might also be noted.

In Satyanarayana Mohapatra v. State of Orissa,XAX the Orissa High Court

said that the order charging the offenders without obtaining sanction and without

jurisdiction is interlocutory and hence not revisable.

With regard to the application of section 221 on framing of alternative

charge, the Delhi High Court in Jatinderkumar v. State (Delhi Administration),142

observed:

[T]he question of framing charge in the alternative can arise when

there is no doubt about facts which can be proved but doubt is as to

what offence will be constituted on those facts.

Discharge

The object of discharge has been adverted to by the Karnataka High Court

in Bangarappa v. Ganash Narayan Hegde143 thus:

Because the object of discharge is to save the accused from unnecessary

prolonged harassment which is a necessary concomitant of protracted

trial. Thus if there is no prima facie case or sufficient and strong

grounds to proceed against the accused are not made out and the

allegations are baseless or the proceedings are mainly aimed at harassing

an accused, under such circumstances it is just and proper for the trial

court to discharge the accused and thus prevent abuse of the process

of the court.

In State of Mizoram v. K. Lalruata}^ the Gauhati High Court pointed out

that before discharge is ordered, three preliminaries have to be gone through:

(0 consideration of police report and the document referred to in section 173

and which are furnished to the accused, (ii) examination if any, of the accused

as the magistrate thinks necessary, (Hi) giving prosecution and the accused an

opportunity of being heard and then to consider whether the charge is groundless.

138 Supra note 121.

139 See Jarnail Singh v. State of Rajasthan, 1992 Cri LJ 810.

140 1992 Cri U 780.

141 1992 Cri LJ 2904,

142 1992 Cri U 1482 at 1484.

143 1992 Cri U 3788 at 3804.

144 1992 Cri LJ 970.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

130 Annual Survey of Indian Law [ 1992

The need for reasoned discharge order has been stressed by the Orissa High

Court in Rabindrakumar Sarain v. State of Orissa.145

In Anilkumar v. State of Rajasthan, involving dowry death, the Rajasthan

High Court spoke about the applicability of section 222 thus:146

When a person is charged with an offence, consisting of several

particulars and if all the particulars are proved, then it will constitute

the main offence, while if only some of those particulars are proved

and their combination constitutes a minor offence, the accused can be

convicted of the minor offence, though he was not charged with it.

Thus a minor offence within the meaning of section 222... would not

be something independent of the main offence or an offence merely

involving lesser punishment. The minor offence should be composed

of some of the ingredients constituting the main offence and be a part

of it.

In Chandar Singh v. State ofM. P., commenting upon the conduct of trial,

the Madhya Pradesh High Court said:147

Before parting with the case, we feel constrained to record our

displeasure on the serious infirmities of not recording any finding on

the charge under section 323 or 323/149 of the IPC though framed.

No court engaged in dispensation of justice can afford to be so

unmindful and nonchalant and it is not expected of it to deliver such

a sketchy judgment and that too on a capital charge.

VI TRANSFER OF CASES

In State of Gujarat v. Ratilal Uttamchand Morabia,m the order of the

sessions judge transferring a case against respondent pending at the sub-divisional

magistrate's (SDM) court was reversed by the Gujarat High Court saying that

though under section 6 of the Code, SDM's court is a criminal court, it may

not give sessions judge jurisdiction to transfer such a case. This power vests

with the district magistrate rather than the sessions judge.

In M. Mohan Shet v. State of Karnataka,149 the Karnataka High Court

rejected the application for transfer of a case made on the ground that an

advocate of their choice was not available.

VII APPEAL/REVISION

In Kalandhicharan Pani v. Ganesh Dalai,150 the appellate jurisdiction of

145 1992 Cri U 1868.

146 1992 Cri U 3637 at 3640.

147 1992 Cri U 3947 at 3952-53.

148 1992 Cri U 9.

149 1992 Cri LJ 1403.

150 1992 Cri U 281.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVIII] Criminal Procedure 131

the High Court has been detailed. Since the trial court's findings were based on

surmises, retrial was ordered.

The Andhra Pradesh High Court in Hoechest India Ltd. v. State of A.P.151

has also ordered retrial as the trial was not proper.

In Durga Prasad Soni v. State of A. P.152 the same High Court said that

where in addition to the substantive fine of Rs. 100/- a recurring fine of

Rs. 5/- per day for failure to pay up the market fee exceeded the maximum

amount, appeal does lie under section 374. So bar under section 376(c) will not

be applicable to such a case.

It has been reiterated by the Supreme Court in E. Balakrishnamma Naidu v.

State of AP. 153 that if the state does not elect to appeal on acquittal, the

appellate court will not interfere with it.

In Haryana v. Ramlal,154 the Punjab and Haryana High Court has said that

one appeal of convictions in six cases cannot be competent. Six appeals will

have to be filed.

In has been decided by the Supreme Court in Ram Milan v. State of U.P.155

that the appellate court while reversing the order of acquittal has to consider

the entire evidence in detail and give cogent and convincing reasons as to why

an interference is warranted.

When two judges on the Division Bench differ, the matter should be put

before the third judge and the court will have the third judge's opinion as final.

It is so declared by the Karnataka High Court in B. Subbaiah v. State of

Karnataka}56

In Dharamaji Gangaram Gholem v. Vinoba Sona Khode,151 the Bombay

High Court ruled that a revision by the complainant in the sessions court

against acquittal of the accused by the trial court should be entertained with

special leave. The court reasoned:158

Sub-section (2) of section 399 does speak of provisions of different

sub-sections of section 401 being applicable "so far as may be". But

sub-section (4) of section 401 speaks of the remedy of appeal provided

by the Code and not any particular provision thereof. Sub-section (4)

of section 378 permits a complainant in a private case to assail a

verdict of acquittal by an appeal to the High Court which appeal can

be preferred only after grant of special leave to appeal. Therefore this

fetter would come in the way of revision entertainable by the Sessions

Judge also.

151 1992 Cri U 2360.

152 1992 Cri U 1614.

153 1992 Cri U 2328.

154 1992 Cri U 2482.

155 1992 Cri LJ 2537.

156 1992 Cri U 3740 at 3742.

157 1992 Cri U 870,

158 Id. at 872.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

132 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

The Orissa High Court in R. Jagadish Murthy v. Balaram Mohanty,*59

observed:160

It is to be noted that section 397(1) does not say on whose motion

court may call for the records of the lower court. But sub-section (3)

indicates that an aggrieved party may make an application. So far as

High Court is concerned, section 401 (1) expressly authorises the court

to exercise power of revision suo motu apart from the application from

a party. The complainant is entitled to move a revision even if State

does not. On the same consideration, revision is maintainable at the

instance of aggrieved private party, even if prosecution was instituted

by police and not on the basis of a complaint.

About the jurisdiction of the High Court in appeal and revision the court

said:161

While the High Court sitting in appeal under section 386 of the Code

can convert finding of acquittal into one of conviction, section 401

sub-section (3) debars conversion of acquittal into conviction. High

Court, however, would not disturb a finding of fact unless it appears

that the trial court shut out any evidence, or overlooked any material

evidence or where there has been manifest error on a point of fact.

In Suresh T. Kilachand v. Sampat Shripat,162 the Bombay High Court held

that bar against review in section 362 cannot be overcome by invoking inherent

power under section 482. With regard to recall, the court said:163

It would be useful to bear in mind the supportive arguments which

would direct the issue, the first of them being that the expression "recall"

of a judgment is virtually a play with words because it involves the

process of setting aside the judgment and this is a power which, under

the Code of Criminal Procedure, rests only with the appellate court.

Secondly, by using the word "recall" one cannot escape from the fact

that the expression "recall" is a disgrace for an initial process of setting

aside the final judgment, restoration of the matter, rehearing which

involves a review and the ultimate possibility of an alteration of the

judgment. The would bring us a full circle back to section 362... .

The Orissa High Court in P. Madhusudan Rao v. State of Orissa164 dealt

with the procedure that should be followed in a case where the possession of

case property is claimed by the accused but he is not capable of accounting for

it. The court said:165

159 1992 Cri U 996.

160 Id. at 999.

161 Ibid.

162 1992 Cri U 1203; see also State of Maharashtra v. Sundar P. Lalwani, 1992 Cri U 2015.

163 Id. at 1210.

164 1992 Cri U 1864.

165 Id. at 1865.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVHI] Criminal Procedure 133

I am inclined to hold that in a case where there is no rival claim and

accused claiming the property to be belonging to him has not

satisfactorily accounted for the same, court should make the departure

from the normal rule and without immediately on judgment of acquittal,

passing an order of disposal, make further enquiry to give opportunity

to accused who is acquitted and from whose custody property is taken

to satisfy the court that he is entitled to the same.

The claimant may have to approach civil courts.

In Virendrakumar Handa v. Dilawarkhan Alij Khan,166 the Bombay High

Court decided that the sessions judge should not interfere with the magistrate's

order under section 457 giving temporary possession to a party as it is an

interlocutory order.

VIII LIMITATION

In Mahendrakumar Lohia v. Sitaraman More,161 the Gauhati High Court

referring to the Supreme Court decision in Sarwan Singhm observed:169

I hold from the reading of sections 467 and 468 ... that for the purpose

of limitation as specified in section 468 ... the limitation starts on the

date of the offence or where the commission of the offence was not

known to the person aggrieved by the offence, the first day on which

such offence comes to the knowledge of such person or where it is not

known by whom the offence is committed, the first day on which the

identity of the offence is known to the person aggrieved by the offence.

The same principle was applied in a case involving offence connected with

return of stridhan. In Babram Singh v. Sukhwant Kaurm the Punjab and Haryana

High Court ruled that unless stridhan is returned, the offence of criminal

breach of trust under section 406 continues. Consequently the period of limitation

is not to be reckoned from the day when the wife was allegedly turned out of

the house of the husband but would continue giving a fresh cause of action

until the stridhan is returned.

With regard to the starting point of limitation of appeal under section 341,

the Orissa High Court in Prahallad Mallik v. State of Orissa, observed:171

In conclusion, we hold that the starting point of limitation of appeal

under section 341 ... is the date on which the Court records a conclusion

that there appears to be commission of offence under clause (b) of

sub-section (1) of Section 195.

166 1992 CriU 2476.

167 1992 Cri U 660.

168 State of Punjab v Sarwan Singh, AIR 1981 SC 1054.

169 Supra note 167 at 661.

170 1992 Cri U 792 (P & H).

171 1992 CnLJ 1432 at 1436,

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

134 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

In State of Karnataka v. B.S. Vijaya Murthy,m the Karnataka High Court

after examining section 468 said that it is clear that the section is applicable in

cases where the offences are punishable with fine, or in cases where the

punishment is imprisonment for one year or between one year and three years

and not otherwise.

In K Kasappa Naidu v. State ofA.P.m the Andhra Pradesh High Court has

also stated that if an offence is stated to be punishable with not less than six

months, it cannot be construed as a term not exceeding one year for the

purposes of section 468(2).

In Bhaskar Hanamatse Meharwade v. State of Karnataka,114 when tro

magistrate permitted addition of offence under sections 201 and 202 IPC in a

case under section 279/304A IPC making it barred by limitation, the Karnataka

High Court upheld the addition and prosecution and pointed out that under

section 468(3) the court is entitled to consider the period of limitation applicable

to the offence punishable with more severe punishment when the offences are

tried together.

IX QUASHING CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS

In some cases the High Courts have, in exercise of their inherent powers,

quashed the proceedings on the ground that the allegations in the cases did not

make out offences triable; in some other cases the High Courts refused to

quash the proceedings.175

In J. Bhoomipalan v. Inspector of Police, Pallavaram,116 the Madras High

Court clarified that section 482 cannot be used to quash an order of the police

including the petitioner in the rowdy list. The court pointed out that article 226

of the Constitution could be invoked. The court said:177

[T]he inherent power is there for the High Court only for the two

specified purposes:

(i) to make such orders as may be necessary to give effect to any

order under this Code; and

(ii) to prevent abuse of process of any court or otherwise to secure

the ends of justice.

The court further reasoned:178

172 1992 Cri LJ 1690.

173 1992 Cri LJ 1214.

174 1992 Cri LJ 3985.

175 See ANZ Grindlays Bank v. Shipping & Clearing (Agents) Pvt. Ltd., 1992 Cri LJ 97;

Somasekharappa v. State of Karnataka, 1992 Cri LJ 1318; Kunnath Abdul Salam Abdurahiman

Vstad v. K.N. Mohammed Ali, 1992 Cri U 4079; T. Parthasarathy v. Smt. Madhu Sangal,

1992 Cri LJ 26; Arvind Kotecha, Director, Kotecha Investment Corporation Pvt. Ltd. v. Mahesh

Kumar Mathur, 1992 Cri LJ 124; Ashwani Kumar v. Delhi Administration, 1992 Cri U 446.

176 1992 Cri LJ 1235.

177 Id. at 1238.

178 Id. at 1239.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Vol. XXVIII] Criminal Procedure 135

Section 482... thus is not available to any person or to the court to

interfere with the order passed by the executive government after the

conviction and sentence recorded by the Court.

In Dr. A.M. Berry v. Ravi Arora,m the Delhi High Court quashed the

proceedings based on the Supreme Court decision in Madhav Rao Scindiam

even at the initial stage. The court pointed out that the rejection of an earlier

petition on the ground of absence of prima facie case is no bar for filing

another on the same ground as it does not amount to review or revision of the

earlier order.

In Jitendra Mohan Gupta v. Statem the police submitted charge sheet

when the petition for quashing the case on the ground of absence of offence

was pending. The purpose was to deny the court jurisdiction under section 482.

The Delhi High Court responded:182

Once this court comes to the conclusion from the record made available

that no case is made out against the petitioner then there cannot be

any ban on the exercise of inherent power where this court feels that

there is an abuse of the process of the court or other extraordinary

situation excites the court's jurisdiction.

X SENTENCE/EXECUTION OF SENTENCE

In Hackbridge Hewitic and Easun Ltd. v. Provident Fund Inspectot

Exempted III-Division,m rejecting a plea that since the petitioners had already

paid the dues and the department was satisfied there should be no action, the

Madras High Court said:184

The doctrine of estoppel cannot be invoked to render valid a transaction

which the legislation has, on grounds of general public policy, enacted

is to be valid, or to give the court a jurisdiction which is denied to

it by statute, or to oust the court's statutory jurisdiction under an

enactment which precludes the parties contracting out of its provisions....

The court expressed the view that the trial court may in view of the

mitigating circumstances consider imposing only fine.

Both in Anirudha Pad v. State of Orissa,1*5 and Madhusudan Sahoo v.

Basuder Pradhan,xm the Orissa High Court ordered the trial courts to give the

accused the benefit of probation.

179 1992 Cri LJ 1327.

180 1988 Cri U 853.

181 1992 Cri LJ 4016.

182 M a t 4018.

183 1992 Cri U 303.

184 Id. at 306.

185 1992 Cri U 122.

186 1992 Cri LJ 1359.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

136 Annual Survey of Indian Law [1992

The Madhya Pradesh High Court in State ofM.P. v. Mohandas,i87 has held

that the period of detention during the pendency of appeal can be set off under

section 428. The court reasoned:188

Considering the context in which the word 'trial' has been used in

section 428 ... and the object and purpose underlying that provision,

we are of the opinion that the word 'trial' used in that provision includes

also proceedings in appeal, like those in the instant appeal.

In State of Maharashtra v. Surbi Chagan Hirabhai Maraman Devsi,m

against the magistrate's awarding of lesser sentence though the offence carried

a much higher punishment on the ground of the respondent being a female, the

Bombay High Court responded:190

The reasoning of the... magistrate that from the scheme of the Code

of Cirminal Procedure the special privileges to ladies insofar as bail

is concerned should also be applied in the case of award of sentence

to females is without any basis. Once an accused is found guilty of

a given offence, then the sentence awarded is to be considered

irrespective of the sex of the accused.

Accordingly the sentence was enhanced.

Rejecting the plea for reducing the punishment in a case involving offences

of rash and negligent driving killing two and injuring one, the Delhi High

Court in Raj Pal v. State said:191

It was submitted that imposition of fine only could also meet the ends

of justice. In answer to it, I would feel content to refer to State of

Karnataka v. Krishna... wherein a conviction under section 304A the

sentence of fine only was imposed by the trial court and the High

Court had refused to enhance sentence. The Supreme Court was

"constrained" to do what the High Court "should have done" and

enhanced the sentence for the conviction under section 304A to 6

month's rigorous imprisonment and fine of Rs. 1000/- and in default

to undergo R.I. for two months.

The court followed the philosophy reflected in the Supreme Court judgment

in Rattan Singh v. State of Punjab,™2 in which it observed, "When a life has

been lost and the circumstances of driving are harsh, no compassion can be

given".

In Sebastian alias Kunju v. State of Kerala,193 the Kerala High Court suo

187 1992 Cri U 101.

188 Id. at 104-05.