Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Arch 0044-8613 1999 Num 58 3 3538

Arch 0044-8613 1999 Num 58 3 3538

Uploaded by

iPro BerryOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Arch 0044-8613 1999 Num 58 3 3538

Arch 0044-8613 1999 Num 58 3 3538

Uploaded by

iPro BerryCopyright:

Available Formats

Archipel

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War

Danny Wong Tze-Ken

Citer ce document / Cite this document :

Wong Tze-Ken Danny. Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War. In: Archipel, volume 58, 1999. L'horizon

nousantarien. Mélanges en hommage à Denys Lombard (Volume III) pp. 131-158;

doi : https://doi.org/10.3406/arch.1999.3538

https://www.persee.fr/doc/arch_0044-8613_1999_num_58_3_3538

Fichier pdf généré le 21/04/2018

Danny WONG Tze-Ken

Chinese Migration to Sabah

Before the Second World War

Throughout its modern history, the state of Sabah in the Federation of

Malaysia has never had a sizeable Chinese community. At no time since the

beginning of mass entries of Chinese into the state did the number go beyond

30% of the state's total population. Yet, despite the numbers, the Chinese

played a significant role in the development of the state.

While commonly accepted as being a part of the wider Chinese Diaspora,

there are some characteristics that are peculiar only to the Chinese in Sabah.

These include, the overwhelming position of the Hakka dialect group within

the Chinese Community ; Sabah is one of the few places in Southeast Asia

where the Hakka is the lingua franca of the Chinese community. Sabah is

also one of the few states where there were systematic attempts on the part

of the colonial government to bring in Chinese immigrants. Nowhere else in

the region was there a northern Chinese community during the pre-Second

World War days. Also the comparatively high percentage of Chinese in the

state who are Christians (30 %) as compared to the whole of Malaysia (9 %),

is among several distinctive features found among the Chinese in Sabah.

It is hoped that this study will help to explain some of the characteristics

of the Chinese in Sabah mentioned earlier.

Early Migration

Even though a Chinese presence in Sabah is a phenomenon of the modern

era, links between the territory of present day Sabah (Borneo) and China

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999, pp. 131-158

132 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

could date back to the Han Dynasty in China. (!) Nevertheless, such links,

which were part of the larger ties between China and the region of Southeast

Asia, were limited only to occasional trade missions and travelling by the

Chinese to the part of the world which they called Nanhai or " South Seas ",

and rarely did the Chinese settle in large numbers in Southeast Asia. (2) In the

case of Sabah, although there are speculations about the possible Chinese

colonies in existence in the territory, little convincing evidence is found. (3)

Several features in the state lend some support to this proposition. The name

of the longest river in Sabah, the Kinabatangan River, and the highest

mountain, Kinabalu, provide room for speculation about the possible

similarity between the word "Kina" and "Cina" (Chinese in the some

Bornean languages including Dusun, Bajau and also Malay). Another

phenomenon that suggests possible early Chinese presence in Sabah is that

the physical features of the Dusun-Kadazan ethnic group resemble Chinese.

All these suppositions however could not be proven for want of sources and

evidence. Nevertheless, it is apparent that more Chinese arrived in Sabah

after the establishment of British rule on Labuan in 1846. (4)

Spencer St. John, an English traveller who visited the west coast of Sabah

in 1858, reported several encounters with indigenous people who could

speak Hokkien (Minnanhua) dialect fluently. Most of them professed to be

descendants of Chinese who were petty traders plying between Labuan and

the mainland. (5) As most of the Chinese who arrived from Labuan had

originated from the Straits Settlements, especially Singapore, this trend

1. The place name of Duyuan, as recorded in the Honshu, Dilizhi 28 xia (Zhonghua shuju, 1962,

p. 1671) is believed by some to be Borneo. See Han Sin Fong, The Chinese in Sabah, East

Malaysia, Taipei, 1975, The Oriental Culture Service, p. 20. Beijing, quoting Hsu Yun-tsiao,

"Hua Chiao", in Xanyang Year Book, 1951, Singapour, Nanyang Press, 1951, Part X, p. 5.

2. For historical links between China and Southeast Asia, see Wang Gungwu, "The Nanhai

Trade : A Study on the Early History of Chinese Trade in the South China Sea", Journal of

the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (hereafter JMBRAS), Vol. XXXI, 1958, Part

2. No. 182; Reprint, Singapore, The Times Academic Presss, 1998 (The Nanhai Trade. The

Early History of Chinese Trade in the South China Sea).

3. For a detailed discussion on early Chinese links with Borneo, see Han Sin Fong, The

Chinese in Sabah, East Malaysia, pp. 20-31.

4. For an overview of the epigraphic remains of the Chinese of Labuan, see Wolfgang Franke

& Chen Tieh Fan, Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, University of

Malaya Press, 1982-1987, III, pp. 1202-1218. Also see Nicholas Tarling, "The entrepôt at

Labuan and the Chinese", in Jerome Ch'en & Nicholas Tarling eds., Studies in the Social

History of China & South-East Asia, Cambridge, At the University Press, 1970, pp. 355-373.

5. Spencer St. John, Life in the Forests of the Far East, Travels in Sabah and Sarawak in the

late 1850s, London, 1862, [Reprinted by Oxford University Press, Kuala Lumpur, 1986], p.

311.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 133

BALEMBANGAN iÇ^ f^BANOGI l.

TUARAN

TELIPOK TAMPARULI

GAYAI MENGGATAL

AMI KINABAIU

JESSELTONtnrlNANAM •

PUTATAN*7PENAMPANG

L ABUAN /BAD AS f ME MBAKUT

TAWAU

'

APAS RO.

WALLACE BAY

SEBATIK I.

Map of Sabah

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

1 34 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

persisted until several years after the establishment of the North Borneo

Company rule. The Hokkiens and the Teochius (Chaozhou) continued their

domination of the scene until the North Borneo Company brought in other

dialect groups.

Even though there were already Chinese in the state prior to 1881, their

number was small. The Chinese only began to enter Sabah in large numbers

after 1881, the year when the territory was taken over by the British North

Borneo Company. The Company was started by Alfred Dent and his partners

in London. They first started their venture in 1878 by establishing several

stations in Sabah including Tempassuk, Sandakan (Elopura) and Papar.

Three years later, the Company's efforts in administrating the newly

acquired territory were recognised by the British Government, which granted

a Royal Charter for the Company to function with the backing of the British

Government.

Immigration Schemes under the North Borneo Company

Among the first questions encountered by the British North Borneo

Company was the need of a sizeable population to supply a sufficient labour

force for the development of the territory. The native population of Sabah

was considered by officials of the Company to be too few and unsuited to

meet the requirements of modern development.^) In 1881, the number of

indigenous people was estimated to be 60,000 to 100,000.(7) These figures

were made up of the Dusuns, Bajaus, Muruts, Orang Sungei, Idahans,

Rungus and many others who also differed in custom and way of life.

The government realised that in order to forge ahead with its

development policy, immigration should be encouraged by every means.

Guided by the successes of other British colonial possessions such as Hong

Kong and Singapore, where sizeable Chinese communities existed, North

Borneo Company officials began to look towards China. Many in the North

Borneo Company administration subscribed to the idea of encouraging the

immigration of Chinese to the new territory. Such a view was supported by

6. Rizalino Oades, "Chinese Emigration Through Hong Kong to Sabah Since 1880", M.A.

Dissertation, Hong Kong University, 1961, p. 39.

7. It is difficult to give an exact figure to the total indigenous population of the state for 1881

as no census was taken. The first census of 1891 gave 67,062 as the total population for the

state, but it was incomplete, as the census did not include many indigenous people who were

left out. However, the figure of 100,000 could be an over-estimation. See Lee Yong Leng,

North Borneo (Sabah) : A Study in Settlement Geography, Singapore, Eastern Universities

Press Ltd., 1965, p. 45.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 135

Alfred Dent and William Hood Treacher, the first Governor of British North

Borneo, (8) and a scheme to bring Chinese into Sabah was planned.

Treacher 's successor, William Crocker, who was acting Governor in

1887, remarked that by encouraging Chinese to migrate to Sabah, "You may

not only secure the development of the country (...) but a paying population

who will in time provide a revenue so much in excess of the cost of

government that the venture has every promise of becoming a profitable

investment ".(9) Crocker was of course referring not only to the industrious

characteristics of the Chinese, but also of their vices and habits, particularly

relating to opium smoking, gambling, and drinking habits from which the

government could extract a dependable revenue through duties and taxes.

Thus efforts were made to procure Chinese labourers for the country. On

5th October 1881 for instance, 29 Macao Cantonese coolies arrived in

Sandakan (10) from Singapore by the S.S. Royalist. William B. Pryer, the first

Resident for Sandakan had sent his Chinese servant to Singapore to obtain

their service. The labourers or coolies were engaged at a monthly salary of

$2.50 with free meals. (U) This method however, was considered to be too

costly and lacking control as the labourers did not, due to the steady $2.50

monthly pay, work to the expectations of some company officials. A proper

system of procuring Chinese labourers and a proper pay scheme was

advocated. (12>

Pryer 's attempt was followed by a series of systematic efforts to bring in

Chinese immigrants to the state. Between 1881 and 1941, Chinese were

brought to Sabah through at least three major immigration schemes, namely,

Sir Walter Medhurst's Scheme, the Basel Missionary Society Scheme and

the Free Passage Scheme.

8. William Hood Treacher, "Sketches of Sarawak, Brunei, Labuan and North Borneo",

Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 21, 1890, p. 27.

9. William M. Crocker, Report on British North Borneo, Sandakan, 1887, p. 5.

10. The existence of this group of Macao Cantonese coolies is mentioned only in the

correspondances of the North Borneo Company. Whereas the earliest surviving Chinese

epigraphic materials in Sandakan should be the inscriptions dated from 1887 comemorating

the fondation of the Sansheng gong by Chinese from Guangdong province. See Wolfgang

Franke & Chen Tieh Fan, Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Malaysia, Vol. Ill, pp. 1232-1247.

11. "Governor Treacher to Chairman and Court of Director", 15 October 1881, Colonial

Office (hereafter CO) 874/228.

12. "L. B. Von Donop, Director of Agriculture to Governor Treacher", 12 November 1881,

CO874/228.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

136 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

Medhurst 's Scheme

The first scheme was implemented between 1882 and 1886 under the

newly appointed Commissioner of Immigration, Sir Walter Medhurst. 0 3) In

addition to being responsible for creating a workable system of obtaining

Chinese labourers and agriculturalists, Medhurst was also instructed to

induce respectable Chinese to form companies for taking up grants of land to

cultivate tropical cash crops. Medhurst set out for China in 1882 with a sum

of $50,000, by far the largest amount ever granted to a single project by the

North Borneo Company. Sir Alfred Dent, the chairman of the company, was

so confident of Medhurst that he wrote him, " It is unnecessary for us to

point out how important it is that you should always work in consort with the

governor [Treacher] ".(14> Dent was wrong in his judgement. Not only did

Medhurst fail to co-ordinate with Governor Treacher, he also failed to

appreciate the immediate needs of the new territory.

Treacher and Pryer, having always looked to the Straits Settlements and

the Malay States for inspiration and guidance, were advised by Hugh Low,

the Resident of Perak, to prepare a scheme that would allow a gradual and

cautious flow of agriculturalists, pioneers, timber-cutters, labourers and

fishermen. Pryer even went to the extent of clearing land and he readied four

reception huts for an initial batch of 100 immigrants. The site chosen was

probably at Melapi, a small settlement 50 miles up the Kinabatangan River

where there were already 20 Chinese, chiefly carpenters and shopkeepers

from Sandakan, " who appear to get on very well with the other

inhabitants"^15) Medhurst received advice and details about the necessary

steps need to be taken, but he ignored them.

In Hong Kong, Medhurst proclaimed on behalf of the Company the offer

of free passage to those who were seeking employment and willing to start a

new life in the new territory. But he did not select the participants. Perhaps,

Medhurst was more concerned with the quantity rather than the quality of

new immigrants for Sabah.

13. Sir Walter Medhurst (1822-1885), joined the Office of the British Superintendency of

Trade in China in the 1840s as a clerk. Prior to that, he was a part of the London Missionary

Society establishment in Singapore. For many years an interpreter to the English Government,

he was also Consul General at Shanghai until 1877 when he received a knighthood.

Appointed Immigration Commissioner of British North Borneo in 1882.

14. "Alfred Dent, Court of Directors to Sir Walter Medhurst", 8 September 1882,

CO874/118.

15. "Report by L. B. Von Donop in Governor Treacher to Chairman", 29 September 1881,

CO874/228.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 137

At least five shiploads of Chinese immigrants came under Medhurst's

scheme. The first batch of 43 came down to Sabah on the steamer S.S.

Hainan. All except one emigrated on his own account without any form of

assistance from the Company. They were mainly what Medhurst described

as "prospectors". The second emigration took place on 31 October 1882,

also via the Hainan. This time, a total of 225 Chinese emigrated to Sabah, of

whom 147 were sponsored, receiving free passage and a portion of wages

paid on account ; whereas most of the others went under a loan of passage

money only. Also included in this trip were two Chinese Christians of the

Hakka dialect group from the Basel Missionary Society, sent to investigate

the new territory for future emigration. There was also a Chinese physician.

The two Christians were funded by Medhurst whereas the doctor received a

half passage subsidy. (16>

The third emigration took place on 8th January 1883 via the S.S. Fokkien

which brought with it 340 immigrants, including 30 families with 81

members. A total of $518 were spent by Medhurst in subsidising this

passage. The fourth shipment arrived in Sabah in April 1883, also via the

Fokkien. Included in the passenger list were 96 Christian Hakkas who, upon

receiving the report of the two delegates sent down on the second trip, had

decided to leave for Sabah. They were settled in Kudat where a settlement

was opened. A further fifth shipment arrived via the S.S. Thaïes with 114

passengers. (17>

Medhurst sent down at least 1,000 Chinese immigrants. Chief among the

group were petty traders, shopkeepers, tailors, shoe makers, labourers and

some farmers, many under the sponsorship of the company. Medhurst was

under the impression that Singapore was booming due to the mass of

Chinese there, but he failed to realise that, unlike Singapore, Sabah suffered

from a lack of enterprises. What Sabah needed was pioneers who were

willing to face the challenge of opening up the country, and not traders or

craftsmen. C1 8) Yet this trend persisted at least until 1886 when Medhurst

returned to England. As shipload after shipload of these unsuited people

disembarked in Sandakan and Kudat, the towns were crowded with them. In

16. Walter Medhurst, "Report on Immigration and the Formation of Chinese Companies",

Secretariat File, No. 16.

17. "Managing Director to Sir Walter Medhurst", 18 September 1883, CO874/1 18.

18. K. G. Tregonning, A History of Modern Sabah, 1881-1963, Singapore, University of

Malaya Press, 1965, p. 130.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

138 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

Kudat for instance, out of a total of 937 inhabitants, 348 were Chinese, of

whom 222 were shopkeepers. (19)

Not only did these traders end up earning very little by trading with each

other, they faced severe competition from their counterparts from Singapore

and Labuan, for whom they were no match. The latter, having arrived much

earlier and being well-verse in the native languages, knew the needs of the

locals. Some of these new immigrants were quite successful, earning to a

profit as middlemen in rice trading. The new immigrants, who were mainly

Cantonese, were basically city-dwellers, and unaccustomed to the forest

before them. Even the few artisans and farmers in the group were finding life

difficult in the new territory. Many packed their bags and returned to China,

or made their way to Singapore. Only a small number remained.

Despite this setback, Medhurst's venture did yield some positive results.

Among those who arrived under Medhurst's scheme were the Hakkas, who

would later play a very significant role in the development of the territory.

The Basel Missionary Society Scheme (1905-14)

In December 1905, two successful pioneers from Kudat were sent back to

China to encourage their fellow countrymen to immigrate to Sabah. The two,

Yong Ah Kit and Lee Ah Pin, both Hakkas, returned in 1906 with 150 Hakka

men, women and children. The North Borneo Company then resettled them

in the Inanam and Menggatal-Tuaran area on the west coast. Like previous

assisted immigrants, they were given land and financial assistance. (2°) The

First eight months of 1906 saw the arrival of 884 free Chinese at Jesselton,

many of whom were Hakka agriculturists who had come to join their

relatives. (21)

In 1912, the economy of the state suffered a setback from the plummeting

rubber prices, this caused a decline in Chinese immigration into the state.

Except for the Hakka Christians who had arrived as agriculturists, Chinese

immigration into the state as a whole suffered a setback. The outbreak of the

First World War also resulted in a reduction in labour procurement for

estates. This was mainly due to the absence of European estate managers and

supervisors, of whom many had returned to Europe for the war. This

however, did not deter many free labourers from entering the state through

19. Tregonning, Ibid., p. 80.

20. Tregonning, Ibid., p. 141.

21. British North Borneo Official Gazette, 2 September 1906.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 139

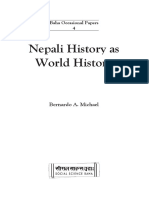

ri.^i/'f H

A Chinese

(Courtesy

trader and

of Sabah

his family

State in

Archives)

Sabah, c. 1890

An Hakka girl in Kudat, c. 1890

(Courtesy of Sabah State Archives)

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

140 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

the sponsorships of relatives. Again, most of these sponsors were Hakka

Christians. Most of these new immigrants were settled on the government

subsidised settlements at Inanam, Menggatal, Telipok, Tuaran, Pinangsoo,

Tamalang Bamboo, Buk Buk and Penampang.

The Basel Missionary Society remained a reliable recruiter for the North

Borneo Company. Arrangements were made to encourage more Hakka

Christians, who were considered to be the "right" class of immigrants, (22)

and who were regarded as the mainstay of the agricultural and industrial

population of the state. An agreement was entered into between the North

Borneo North Borneo Company and the Basel Missionary Society in

November 1912, whereby the Basel Missionary Society would continue its

role in bringing in Christian Hakka settlers. The agreement stipulated that :

1. Each family shall receive 10 acres of land upon arrival.

2. The premium is set at $1 per acre, and an annual quit rent of 500 per acre shall be

collected. There will be no quit rent for the first two years.

3. No permanent titles shall be given should the immigrants failed to repay advances.

4. The Government will undertake the guarantee of temporary accommodation for the

immigrants.

5. Half of the land given shall be cultivated with paddy and other cash crops, while the

other half is for subsistence crops.

6. When necessary, the Government shall provide food rations for the first six months.

7. Each family should consist of four to eight persons.

8. The Government will grant to the Mission, land for schools, churches and cemeteries,

and provide grants-in-aid for their upkeep.

9. The Government shall provide attaps and tools on arrival.

10. The family can choose to settle down with their own relatives upon arrival. (»)

Most of the Hakka Christians who came under the Basel Missionary

Society Scheme were originated from the various counties in Guangdong

province where the society had carried out mission work among the Hakkas

since the mid- 19th century, particularly the counties of Meixian, Wuhua,

Longchuan, Zijin, Dongguan, Huizhou, Xingning, Huaxian, Baoan and

Qingyuan.

In March 1913, a total of 26 families or 111 Hakka Christians were

brought in by the Basel Mission to settle in Inanam. This resulted in the

cultivation of 500 acres of land. On top of that, as in previous agreements,

the North Borneo Company granted each family 10 acres of land. (24> The

22. "Governor Gueritz to Court of Director", 7 December 1905, CO874/746.

23. Source : "Governor to Chairman", 31 March 1913, CO874/746.

24. British North Borneo Herald, 16 May 1913.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 141

group was divided into two, with 12 families settling in Menggatal and 10

others in Inanam. Four of the families went to Kudat. (25)

New settlements for Hakka Christians who came under the Basel

Missionary Society scheme were also opened in Menggatal and Telipok with

the arrival of two additional groups of 53 families (167 members) and 30

families (105 individuals) respectively. However, the later group who had

settled in Telipok transferred their allegiance to the Roman Catholic Mission

as no Basel Missionary Clergy was present there until 1927. (26)

The new Chinese settlements along the Tuaran road connecting Inanam,

Menggatal, Telipok, Temparuli and Tuaran resulted in the further

development of a group of Christian Chinese smallholders, similar to those

who had arrived earlier in Kudat. The Hakka Christians soon became

important rubber smallholders in Sabah, due to their being given favourable

land concessions and government subsidies. Although their holdings could

not compare in size with the large European-owned rubber estates, they

remained important contributors to the development of the Sabah economy.

In Kudat, 63 families or 273 persons arrived during 1913-1914 and were

settled in the Pinangsoo, Tamalang Bamboo and Buk Buk settlements under

the terms agreed upon by the Basel Mission and the North Borneo Company.

Under the agreement, each family would be given a plot of five acres

without premium, and rent would be free for two years, and taxed at $1 per-

acre, annually thereafter. This was considered a very favourable term as most

of these people had never owned any land before. (27)

Free Passage Scheme (1921-1941)

At the beginning of the twenties, the Chinese in Sabah numbered about

thirty thousand, making up probably one-fifth of the territory's population.

The idea of having a sizeable Chinese labour force in the state remained a

widely accepted notion. The North Borneo Company decided to further

encourage the Chinese to enter the state by introducing a new immigration

scheme.

The scheme, known as the "Free-Passage" or "Free Pass" scheme, was

much simpler and almost hassle-free compared to the earlier ones. Under the

" Free-Passage " scheme, the government had not engage itself in direct

25. "Resident, West Coast to Governor", 13 March 1913, C0874/746.

26. See BCCM (Basel Christian Church of Malaysia) Centenary Magazine, Kota Kinabalu,

1983, p. 72.

27. See Oades, "Chinese Emigration Through Hong Kong to Sabah", p. 56 and BCCM

Centenary Magazine, pp. 23-47.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

142 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

procuring of labour as it had earlier. Instead, a pass would be offered to any

bona fide Chinese settler in Sabah with a landholding of not more than 25

acres. The settler could obtain the pass from the district officer and had it

sent to his relatives in China, entitling the latter to free passage to Sabah.

Upon receipt of the pass, the intended family member or relative would

present himself or herself to the Company's agent at Hong Kong, before

being shipped out to Sabah at the expense of the North Borneo Company.

Unlike the earlier schemes, the new scheme was aimed at attracting

settlers instead of labourers. By 1920, the need for settlers in Sabah

outweighed the need for labourers. Procurement of labourers to work on the

estates depended much on the planting programmes of the European-owned

estates, this resulted in slower opening and cultivation of new land.

Furthermore, Chinese labourers had only consisted of about 50 % of the total

labour force in the estates, while the rest were either Javanese or indigenous

people. A settler, however, could help to put more land under cultivation,

and at the same time, pay more in revenue tax.

For the purpose of disseminating information concerning the new

scheme, an illustrated pamphlet in Chinese advertising the prospects for

settlers in Sabah was distributed. (28) The scheme offered the new arrivals the

opportunity to take up, within a year of their arrivals, a plot of 5 acres of

land without premium and free of rent for two years. Apart from that,

various other terms similar to those offered to the Basel Church settlers were

included.

The newly arrived family members would stay with their sponsors, who

would ensure their well being. While women normally joined their

husbands, male relatives would normally stay with their sponsors for some

time before being granted a plot of land of their own. To safeguard the new

arrivals from being mistreated by their relatives, the District Officers made

frequent visits to their dwelling places. (29>

Despite its attractive terms and easy access to Sabah, the scheme did not

immediately receive a favourable response when first introduced in 1921.

Only 24 passes were taken up that year. This lukewarm response was mainly

due to a sharp fall in the price of rubber, the mainstay of the agriculture

activities in the state at that time. In fact, the drop of rubber and copra prices

had greatly affected the number of Chinese settlers on the west coast,

28. British North Borneo Administration Report, 1922, p. 58.

29. "Court of Directors to Governor", 15 January 1925, as cited in Tregonning, A History of

Modern Sabah, p. 150.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 143

especially among the Hakka Christian settlers along Tuaran Road. Between

1920 and 1921, the number of Hakka Christian settlers in Inanam had

declined to 25 families, while 16 families remained in Menggatal and 12 in

Telipok.(3°) By 1924, many had sold their lands, repaid the government, and

left. (3D

But as rubber prices began to increase, so too did the demand for more

labourers. This soon led to an increase in the popularity of the free passage

scheme ; more passes were issued. The popularity of the scheme was also, in

part, encouraged by the government's newly promulgated " Land Ordinance

of November 1923", which saw favourable new land terms offered to non-

indigenous Asians. Under the scheme, the concessionist would be exempted

from paying land rent for the first six years if the land were cultivated within

six months of occupation. (32>

After 1924, the number of passes issued actually increased. While only

24 passes were issued in 1921, a total of 800 passes were taken up by 1924.

In 1927, a total of 1,054 passes were issued, and 1,665 in 1929.

Among the Chinese in Sabah, the scheme was particularly popular among

the Hakkas who took the opportunity to bring in their relatives, (33) an

endeavour that they could not afford on their own. To the Hakkas, whose

earlier lives in China were generally spent in over-crowded communal land,

the offer of agricultural land by the government looked like a bonus, if not a

windfall. The eagerness of the new immigrants to take up land of their own

often result in applications for land coming in faster than the Land Ranger

could deal with them. The granting of land to the new immigrants resulted in

the opening of new, previously undeveloped areas. One such place was the

area around Appas Road in Tawau, which eventually become an important

agricultural area. (34)

One of the most remarkable consequences of the free passage scheme

was the increase of Chinese female immigrants. This indicated that the new

immigrants intended to settle down in the state. This also changed the gender

ratio of the Chinese from 367 females per 1,000 males in 1921 to 565

females per 1,000 males in 1931. (35> Again, in most cases, it was the Hakkas

30. British North Borneo Administration Report, 1922, p. 60.

31. British North Borneo Administration Report, 1924, p. 9.

32. K. G. Tregonning, A Modern History of Sabah, p. 150.

33. British North Borneo Herald 16 July 1929.

34. British North Borneo Herald, 16 November 1928.

35. See L. W. Jones, The Population of Borneo : A Study of the Peoples of Sarawak, Sabah

and Brunei, London, University of London, The Athlone Press, 1966, p. 51.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

144 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

who had brought their women folk to Sabah, as they were the main group, to

utilise the scheme.

Table 1. Number of Female Chinese in Sabah

According to Dialect Group, 1921-1951

Dialect Group 1921 1931 1951

Hakka 6,168 11,330 20,610

Cantonese 2,413 3,621 4,995

Hokkien 1,213 1,735 3,074

Teochiu 424 710 1,562

Hailam 124 333 1,347

Source : L. W. Jones, North Borneo : A Report on the Census of Population held in

4th July, 1951, London : University of London, 1953, p. 112.

The new immigration scheme resulted in a steady increase in the number

of Hakkas in Sabah. In the 1921 census, the Chinese community was

counted in their respective dialect groups for the first time. Among the eight

dialect groups included, the Hakkas were numbered 18,000 persons, 47.82%

of the total Chinese population in Sabah. In 1931, ten years after the

implementation of the "Free-Passage" scheme, the total number of Hakkas

in the state had increased to 27,424 persons, or 54.78 % of the total Chinese

population. The Cantonese, who had long been the largest dialect group,

were a distant second with only 12,831 persons, 26.63 % of the total Chinese

population in 1931. (36) Since 1921, the Hakka community had replaced the

Cantonese as the largest dialect group in the state, and the first ten years of

the "Free-Passage" scheme ensured that the Hakka's position as the largest

Chinese dialect group would become unassailable. In many ways, this

significant change would also result in the Hakka dialect emerging as the

most widely spoken dialect in Sabah.

There were also Chinese who had arrived in Sabah on their own account

and worked as labourers in the various estates on the east coast of Sabah,

including places like the Kinabatangan and Segama river basins. Others were

36. L. W. Jones, North Borneo : A Report on the Census of Population held in 4th July, 1951,

London, University of London, 1953, p. 112.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 145

recruited to work on the railroad on the west coast of Sabah. Many of these

people eventually settled along the railways from Jesselton (Kota Kinabalu)

to Tenom in the interior.

Table 2. Total of Chinese Arrivals to Sabah

under the Free-Passage Scheme / Self-sponsored, 1921-1940

Year Free Passage Scheme / Self-sponsored

1921 18 -NA-

1922 4 -NA-

1923 200 -NA-

1924 530 -NA-

1925 204 -NA-

1926 317 -NA-

1927 886 -NA-

1928 1,278 2,724

1929 1,067 2,967

1930 1,157 2,882

1931 395 1,519

1932 92 1,086

1933 187 2,315

1934 643 3,307

1935 667 3,837

1936 395 4,577

1937 493 7,912

1938 345 3,342

1939 263 1,992

1940 373 2,472

Total 3,859 31,998

Source : North Borneo Annual and Administrative Reports, 1921-1940.

There are however, some differences in characteristics between the self-

sponsored Chinese and those who came under the various schemes initiated

by the North Borneo Company. Firstly, most of the Chinese who came under

the various free passage schemes were settled on the west coast of Sabah,

including the Kudat peninsula. Once settled, the new arrivals were granted

land as normally stipulated in the immigration agreement. As a result of the

new land ownership, most of the Chinese on the west coast, Hakkas, were

much more docile, and experienced a greater growth in numbers. This is

different from the self-sponsored Hakkas, most of whom had worked as

indentured labourers in the various estates upon their arrivals. Though many

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

146 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

eventually took up land at the end of their contract, there were also many

who continued to work as wage earners, or in some cases, left the state for

good. Due to the concentration of the earlier agriculture estates on the east

coast of Sabah, many of the self-sponsored Chinese also concentrated on the

east coast. When rubber estates sprang up on the west coast after 1905, a

steady entry of free Chinese labourers to work in these estates also began.

Some were also hired as workers on railway construction. As a result of this,

the Hakka concentration on the west coast of Sabah is much higher than on

the east coast.

Secondly, unlike their counterparts who had arrived under the various

schemes, many of whom were Christians, the self-sponsored Chinese were

normally practitioners of Chinese religions, including ancestor worship. This

is evident from the pattern of growth experienced by the Basel Church in

Sabah. The church, which is a Hakka-based church, did not open in

Sandakan until 1907. This was long overdue, for Sandakan was the capital

for the state, and has been in existence since 1878. (37> The Basel Church was

not opened in Tawau until 1950, and in Lahad Datu until 1972.

Table 3. Chinese Population

According to the Censuses of 1911, 1921, 1931 and 1951

Chinese/Year 1911* 1921 1931 1951

Hakka -NA- 18,153 27,424 44,505

Cantonese -NA- 12,268 12,831 11,833

Hokkien -NA- 4,022 4,634 7,336

Teochiu -NA- 2,480 2,511 3,948

Hailam -NA- 1,294 1,589 3,571

Other Chinese -NA- 1,039 1,067 3,181

Total 27,801 39,256 50,056 74,374

* Figures on the various dialect groups were not available.

Source : Extracted from L. W. Jones, North Borneo : A Report on the Census of

Population held in 4th July 1951, London, University of London, 1953, p. 112. No

census was taken in 1941.

37. Prior to the establishment of the Basel Church in Sandakan, an Anglican/SPG church, St.

Michael's and All Angels, was started in 1888. Most of the worshippers in the church were

Hakka Chinese. Nonetheless, the fact that it took the Basel Church such a long time to make

an inroad into Sandakan clearly suggests that the Hakka Christian community in that town

was small.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War \A1

Problems of Chinese Immigrants and Minor Immigration Schemes

The immigration of Chinese to Sabah after 1883 continued steadily with

an average of 100 to 200 persons every month. Most of those who arrived

were contract workers brought in to work in the many tobacco estates that

had sprung up in the territory. The demand for more labourers at this stage

was a result of the success of Sabah tobacco in penetrating the international

market in 1887. The tobacco industry experienced a minor boom in 1888,

where nearly 70 companies were involved in the planting of the crop,

representing German, Dutch and British interests. This resulted in a rise in

the demand for labourers to work on the estates.

Early days at the estates were most unkind to the Chinese, many fell sick

and succumbed to the harshness of the land and weather. Most labourers

were brought in under very stiff indenture or under agreements, which would

bind them to the estates for many years. In the estates, living conditions were

deplorable, men were normally housed in filthy quarters at the coolie-lines

or kongsi, the workers were also poorly paid. Maltreatment by estate

managers and supervisors was common. Many suffered from physical

distress and were left without medical treatment. Up to 1890, the death rate

in the estates was high. Before the end of 1890, nearly 2,000 out of the total

of 8,061 Chinese working in estates had died. In the case of the Tongood

Estate, which was highlighted by the British North Borneo Herald, the estate

had a dreadful mortality rate of 70% from July 1890 to June 1891.(38) The

appalling conditions did affect Chinese immigration. In 1891, a total of

1,155 Chinese labourers left Sabah for Singapore after the completion of

their initial contracts ; and a further 85 1 left for Hong Kong ; (39) their

departures could be seen as a setback to the goal of the North Borneo

Company in the procuring of labourers.

In 1891, most estates registered a death rate of over 20%, and several

went as high as 40 %. This had some negative effect on those who intended

to emigrate from China via Hong Kong. In April 1891 for instance, out of

300 labourers who signed up in Hong Kong, only 4 could be persuaded to

come to Sabah. Another problem was that many of those who had signed up

were pronounced fit by the Hong Kong Government Emigration Office, but

upon arrival, the estates would normally find that only the weak ones had

made the trip. Only in 1890 were medical check-ups were carried out in

38. British North Borneo Herald, 1 October 1891.

39. British North Borneo Official Gazette, 1 February 1892.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

148 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

Sabah to ensure that those who intended to enter the state were in good

health. (40)

As the tobacco plantations were profiting from favourable market prices,

free coolies, who were mainly artisans, began to demand higher pay. In the

Lahad Datu Estate in Darvel Bay for instance, a daily wage of 60 cents was

demanded by Chinese coolies in 1891, ten cents more than the usual

price. (41) Apart from occasional maltreatment, and complaints received at

the Office of Superintendent of Immigration and Labour, welfare at the

estates had begun to improve. An amendment was made to the " Estate

Coolies and Labourers Protection Proclamation of 1883" in which a

provision for proper medical attention in the estates was added. (42)

The demand for Chinese labourers on the tobacco estates, however,

suffered a setback from 1890 to 1893, when the tobacco industry in Sabah

collapsed, partly due to the McKinley Tariff imposed by the United States

Government. The tariff was a protective measure aimed at safeguarding the

interests of the tobacco planters in southern Virginia. Under the tariff,

American cigar manufacturers stopped importing from Sabah tobacco

leaves, for wrapping cigars. As a result of this setback, Sabah suffered a

revenue deficit in 1892, when the state revenue of £51,118 was outweighed

by an expenditure of £53,044. (43) The demand for labourers was on the rise

again from 1893 onwards, when the demand for tobacco leaves improved.

As much as the Chinese were wanted in Sabah, the procurement of them

at a reasonable price was a problem. Apart from the Singapore merchants

who controlled the labour trade from the island and the Straits Settlements,

the North Borneo Company Administration was also confronted by rings of

coolie brokers operating at Amoy (Xiamen) and Canton. (44> E. E.

Abrahamson, the Company Agent at Hong Kong, was sent by the Court of

Directors in 1887 to seek a clearing from the Chinese Government to allow

direct procurement of Chinese labourers. Abrahamson even had discussions

with Li Hongzhang at the zongli yamen or Foreign Office, in Tianjin, where

he concluded some important contracts with Li for procuring labourers. They

also agreed on re-establishing steamer service from China to Sabah. (45)

40. Ibid., p. 136.

41. British North Borneo Herald, 1 January 1891.

42. "British North Borneo Government Notification No. 79", British North Borneo Official

Gazette, 1 April 1891.

43. British North Borneo Herald, 1 November 1893.

44. E. E. Abrahamson's Report in British North Borneo Herald, 1 March 1888.

45. British North Borneo Herald, 1 March 1888.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 149

Despite all his efforts, Abrahamson failed to secure labourers from the two

ports of Amoy (Xiamen) and Swatow (Shantou).

At Canton Abrahamson's effort was met with some success, especially

engagements that were based on agreements for three years at $9 per month

wages and an advance to the labourers prior to the commencement of work.

The Company also need to pay a $50 per head commission to the brokers,

which was probably the lowest, compared to those charged by the Teochiu

and Hokkien brokers at Amoy. (46> This was probably one of the reasons why

Sabah had received more immigrants from the province of Guangdong than

from other provinces.

The flow of Chinese into Sabah increased every year. The number who

arrived and those who choose to remain in Sabah out-weighed those who

returned to China after the lapse of their contracts. This steady rise in

Chinese immigration to Sabah was prompted by several reasons. An editorial

of the British North Borneo Herald suggested three factors that had

prompted the increase. The increase of the entry tax from $20 to $100 per

head for all new Chinese immigrants seeking entry to Australia had turned

many prospective immigrants away from that place. Many were seeking

alternative destinations, of which Sabah would provide such opportunity at a

very low price. The imposition of a $10 per annum poll tax on all

immigrants by the Australian Government also prompted a decline in

immigration to that country. The unbearable living condition in China,

particularly the desolation caused by the flooding of the Yangzi River had

prompted more Chinese to seek a new livelihood outside their country. Last

but not least, was the persecution faced by the Hakkas, who were the main

supporters of the Taiping Rebellion, which compelled many to look for an

opportunity to start a new life elsewhere.

For many years, William B. Pryer was the Superintendent of Immigration

and Labour. He later transferred this responsibility to Captain R. D. Beeston.

In 1894, the government engaged the service of Dr. N. B. Denny s to promote

the immigration of Chinese into Sabah. (47> Dr. Dennys, who was a man with

vast experience in Chinese affairs, went to Hong Kong with the support of

the planters on the Kinabatangan River, with the purpose of breaking into the

Chinese-controlled recruiting organisation. The planters in North Borneo

were hoping to secure Chinese labourers at $35 per head as compared to the

price of $60 being charged by the Chinese brokers. He failed. The Chinese

46. British North Borneo Herald, 1 March 1888.

47. British North Borneo Herald, 1 May 1894.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

1 50 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

brokers were unbreakable, and they retaliated by pooling enough resources

to offer lower rates than Dr. Dennys could manage to estates in the Marudu

Bay and elsewhere, causing the Kinabatangan planters to withdraw their

support for Dennys. (48) The failure prompted Dr. Dennys to recommend to

the government to take over the whole affair of importing Chinese labourers.

Once again, he failed, for the idea was too drastic and too expensive to be

even considered. (49>

By the time of Dr. Dennys 'appointment to the post of Superintendent of

Immigration and Labour, the general condition of the Chinese labourers had

improved. His appointment lent further support to this development. By

then, the coolies even had enough money to remit back to China. (5°) The

year after Dr. Dennys 'appointment saw the ascendancy of William Clarke

Cowie as the managing director of the North Borneo Company ; and the

appointment of L. P. Beaufort (1895-1900) as the new governor. Cowie, who

had spent considerable time in Sabah, viewed the influx of the Chinese into

Sabah with contempt. He was one of those who believed labourers could be

secured among the indigenous people, living in large settlements further

inland. (51) Thus, Cowie refused to sponsor any immigration plan put forward

by the Governor or whoever. In fact, under Cowie 's leadership, no money

was spent on immigration. This policy was to last for almost a decade, until

1903, when Cowie was compelled to give in, mainly because of the urgent

need of procuring labourers for the railways.

Cowie had previously rejected the need to secure sufficient Chinese

labourers from China for the proposed Jesselton-Tenom railway track.

Attempts by the Governor to bring in labourers from Singapore were

reprimanded. To make things worse, Governor Beaufort added new obstacles

to importing immigrants from China by imposing several new taxes,

including one on rice, the staple diet of labourers. The 5 % duty added to the

cost of rice had a profound effect on those estates that continue to secure

their labour independently. The tax had turned away many prospective

immigrants from Sabah who moved on to other destinations. The monthly

immigration report from Dr. Dennys for 1896 to 1899 revealed a sharp

decrease in the labour flow from China. The steamer S.S. Memmon, which

run a regular service on the Hong Kong-Sabah-Singapore route often saw the

48. Tregonning, A History of Modern Sabah, p. 137.

49. Ibid.

50. Ibid.

51. Ibid.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 151

majority of its passengers from China heading for Singapore, by-passing

Sabah. (52> Fewer coolies from China were engaged during this period

because the cost of engaging a Chinese coolie from China was by then

relatively more expensive than getting them from Singapore.

Throughout the period of Cowie's chairmanship, the flow of Chinese into

Sabah was limited to very small number. Many of the early settlers also left

for either their homeland or other destinations. Among the lower income

groups, only those Hakkas with small land holdings choose to remain in

bigger numbers, their influx into the state were not so adversely affected. (53>

This was mainly due to the fact that Sabah, even with many restrictions and

unattractive taxes, still offered the Hakkas something better than being

persecuted, both politically and religiously in their homeland. Only

occasionally did Sabah receive large shipments of Chinese immigrants, and

they consisted mostly of free coolies and some contract coolies. A most

unexpected influx of coolies, both free and contract, took place in May 1899

when 182 free Chinese and some 425 contract coolies were landed in

Sandakan by the steamer Mansang. They were meant for the Kinabatangan

and Lahad Datu Tobacco Estates. (54)

The problem of obtaining sufficient manpower for the estates, especially

with more and more leaving the state upon the completion of their contract,

refusing to sign a new contract, caused an outcry from the Chinese Advisory

Board and the planters. (55> They even went so far as to send a protest to

London in 1898 regarding the new taxes. (56>

At the closing stage of the nineteenth century, Governor Hugh Clifford (1900-

1901), who had succeeded Beaufort, attempted to solve the problem of the

shortage of labourers and pioneers in Sabah. Taking advantage of the turmoil in

China at that time, especially of the Boxer Rebellion, Governor Clifford offered

free land to refugee Chinese Christians. He had communicated this intention

through the commissioner of land to the agents in Canton and Swatow. The

attempt however, failed to elicit any response from the Chinese.

In an attempt to procure Chinese labourers for working on the railway, a

Chinese recruiter from Sabah went to Hong Kong in 1902. After failing to

52. British North Borneo Herald, 1 May 1896.

53. Ibid.

54. British North Borneo Herald, 16 May 1899.

55. The planters in Sabah formed their own Planters 'Association of North Borneo. It

remained a very influential group in the history of the state. The Association was even given a

seat in the North Borneo State Legislative Council upon its formation in 1912.

56. Tregonning, A History of Modern Sabah, p. 137.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

152 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

recruit any, he proceeded to Foochow where two years earlier the Sarawak

Government had succeeded in obtaining a sizeable number of Chinese

immigrants. A total of 169 were recruited and were brought to Sabah for the

railway. This group suffered great loses while working on the railway. Not

only were they badly paid and miserably housed, they were also underfed.

Most died from beriberi. The incident sparked off a riot in Foochow against

the recruiters. Not only did the event result in the small number of Foochow

Chinese in Sabah prior to the Second World War, it also demonstrated the ill-

preparedness of the government to handle new immigrants at that time.

Due to the unfavourable living conditions caused by the 5 % Rice Tax,

many Chinese labourers left the state for China or other destinations. The tax

also affected the hiring power of many plantation estates that were burdened

with paying more for provisions for the Chinese labourers. Many decided to

reduce the number of workers. In 1903, Governor Birch recommended that

the rice tax be abolished. Birch was taken aback by the outflow of Chinese

labour from the state. In February 1903, the Court of Directors reluctantly

suspended the tax. They also set aside a total of $ 60,000 to assist the

Chinese immigration programme. For the purpose of more effective

immigration control, the Coolie Depot at Berhala Island outside of Sandakan

was repaired and maintained. Mass immigration of Chinese to Sabah was

then resumed.

By 1907, Chinese made up more than 50 % of the total labour force in the

estates throughout Sabah, with 4,856 out of a total of 10,467. In that year, all

the Chinese labourers except 181 of them were engaged on a written contract

for 3 years. The contract, which promised a financial advance upon re-

engagement after the lapse of the previous contract, usually left many of the

Chinese tied to the estates, without the slightest hope of freeing themselves

from the debt incurred. This practise of allowing various advances to the

labourers, had left the coolies at the mercy of their employees. Throughout

the period 1911-1920, for instance, labour unrest in the estates were very

common, mainly due to the many grievances on the labourers 'part, caused

by discrimination and cruel treatment at the hands of the mandor

(supervisors) and managers of estates. At times, labour unrest would result in

the death of the manager and his staff. The Armed Constabulary or police

were usually called upon to stop this unrest.

An amendment to the "Labour Contract Ordinance 1890" was made in

1908 whereby the Protector of Labourers was given more authority to look

after the welfare of the labourers in Sabah, including the Chinese. For

indentured Chinese workers, there were efforts on the government's part, to

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 153

reduce the total length of service from three to two years, if the contract was

executed outside of Sabah. The duration was later cut to not more than 300

days for a contract executed within the state. (57>

The northern Chinese

One distinguishing feature of Chinese immigration to Sabah was the

presence of a northern Chinese community in the vicinity of Jesselton. This

is unique because so far, nearly all the Chinese who came to Sabah and

Southeast Asia were of southern origin, particularly from the two provinces

of Guangdong and Fujian. This pioneer group of northerners, or the

"

Shandong community " as the local Chinese wrongly termed them, were

natives of Hebei province. The community was brought in through the effort

of Sir West Ridgeway, the Chairman of the North Borneo Company who

thought they would make good pioneers in Sabah, after watching them at

work during his train journey from Beijing in 1913. An agreement was

immediately entered into in August 1913 with the new Chinese Republic

Government of Yuan Shikai, whereby similar terms to those agreed with the

Basel Missionary Society were offered to the northern Chinese. The terms

included a 10 acre land grant to each family with no premium required, rent

free for two years, and 50 cents per-annum per-acre thereafter. The

favourable terms were accepted and steps were undertaken to begin the

recruiting of the northern Chinese. (58>

The forwarding company of Messrs. Forbes & Company of Tianjin was

engaged to send this first batch of 107 families or 430 persons to Sabah.

Most of these northern Chinese originated from the counties of Jingzhou,

Wenan, Shenzhou, Gu'an, Cangxian, Baxian, Yongqing, Jinghai and Tianjin,

all in the province of Hebei. The group was accompanied by a Dr. Sia Tien

Bao (Xie Tanbao), who was deputised by the Chinese Government to be the

overseer of the group. Even though the agreement had provided for a total of

250 families to emigrate to Sabah, this figure was never achieved as due to

the high cost incurred for bringing down the first 107 families, and no

further immigration of northern Chinese was undertaken. (59>

The northern Chinese immigrants were settled at the foot of the hill of

Reservoir Road (Jalan Kolam Air). The land was not as fertile as those given

57. "Proclamation No. 9, 1916", British North Borneo Official Gazette, 28 August 1916.

58. Tregonning, A History of Modern Sabah, p. 147.

59. J. Maxwell Hall, "Our Northern Chinese : Shantung Settlement on Penampang Road",

Kinabalu Magazine, Vol. II, No. 3 & 4, January- April 1953, p. 21.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

1 54 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

to the Hakka Christians along Tuaran Road, but with much perseverance,

they overcame the weakness of the land and began to produce sufficient food

for themselves. Unlike the Hakka Christian settlers who were left alone to

work on their land, the northern Chinese had to spend two to three days a

week working on public projects, including the railway. Other days were

spent working their land. (6°)

Although the northern Chinese worked extremely hard to produce

sufficient food for themselves and to generate extra income, the hardship

faced by the community did take its toll as some who could not withstand

the harsh conditions chose to return to China. (61) By 1928, the numbers in

the community declined to 375, compared to 430 in 1920. (62) The Hebei

Chinese also brought with them a different form of education. When they

opened their own school in 1917, housed in the kitchen of Captain H. V.

Woon, the superintendent of the settlement who was appointed by the North

Borneo Company, lessons were conducted in Mandarin, the official language

of modern China, using the National Chinese Reader. (63) This differed from

most of the Chinese schools, which conducted lessons in their own dialects,

depending on the dialect background of the sponsors of the schools

concerned. Chan Pin Chung was appointed as the schoolmaster of the

Jinqiao School. Thirty students attended the school.

Apart from having a different dialect, the northern Chinese also had

among them several family names which are distinct from the southern

Chinese. Among the most common family names among the 107 families

are, Dong, Fan, Fang, Gong, Han, Nie, Shi, Zhuang and and Xu. t64)

Another feature that became quite common among the northern Chinese

was their inter-marriages with native women, particularly the Dusuns of the

Penampang area. The impetus for this feature was however, different from

that experienced by the early Hokkiens and Teochiu traders who came to

Sabah without their families, where the scarcity of Chinese women in the

country from the middle to the end of the 1800s had compelled the earlier

pioneers to marry native women. In the case of the northern Chinese, by the

time of their arrival, there was already a sizeable number of Chinese women

60. Ibid.

61. Many sold their land before their departure for China. British North Borneo Herald, 2

January 1934.

62. See also British North Borneo Herald, 2 June 1934.

63. "Inspector of Schools to Governor Secretary", 6 April 1917, Secretariat File, No. 812.

64. Wolfgang Franke & Chen Tieh Fan, Chinese Epigraphic Material in Malaysia, Vol. Ill,

Kuala Lumpur, University of Malaya Press, 1987, pp. 1224-1231.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 155

in Sabah. Nonetheless, the northern Chinese could not relate well to the

majority of southerners who were socially and linguistically different from

them. This created social barriers between the two groups of Chinese. The

northern Chinese speak their own dialect and Mandarin. Most would not

have the faintest idea of what their southern counterparts were saying. The

southerners would normally speak their own dialects, and had very little, if

any, knowledge of Mandarin. At that time too, inter-dialect group marriages

were still unpopular. Thus this combination of factors resulted in very little

integration with the southern Chinese, compelling many of the younger

northern Chinese to settle for a Dusun wife. (65)

Further Immigration until 1941

During the economic boom of the 1920s, a greater portion of the Chinese

influx was self-funded, and unrestricted. Sabah, which was hardly known to

the prospective immigrants, suddenly became attractive and became a

popular destination after 1925. The increasing popularity of Sabah could be

attributed to the favourable environment of the territory and the difficulty of

life in China. Sabah experienced an unprecedented economic boom which

offered many opportunities for a better livelihood. Apart from that, the

territory was no longer a " god-forsaken " hinterland compared to the

situation a few decades earlier. The presence of a sizeable Chinese

community would ensure a familiar environment for the new immigrants.

The ceaseless natural catastrophes in China, especially the 1928 flood, and

the political strife prompted many to seek greener pastures abroad, and

Sabah became one of the favoured destinations.

The steady growth of the Chinese community and their industry and

efforts in the development of the Sabah did not go unnoticed. In 1928, Sir

Neil Malcolm, the chairman of the North Borneo Company commented :

It is not too much to say, that under the influence of these two factors - land terms and

road development - the country is undergoing a remarkable and most interesting change

in character... It is no longer a land of only a few large companies, whose profits are

distributed in London, but is rapidly becoming a home for Chinese peasant proprietors,

working and living under British Administration. <66)

The North Borneo Company Government also initiated a programme to

train sufficient number of European officials to speak the Hakka dialect and

Mandarin. In 1928, a "Language Proficiency Bonus" was introduced to the

65. Tregonning, A History of Modern Sabah, p. 147.

66. "91st Half- Yearly Meeting of the British North Borneo North Borneo Company", British

North Borneo Herald, 1 September 1928.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

156 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

government service scheme. Under the scheme, government officials were

encouraged to learn Chinese and would be rewarded with a special

allowance on reaching a certain standard.

The opening years of the 1930s saw some gloomy prospects in the

economic development of Sabah and the world as a whole. The financial

crash of 1929 had taken a long time to recede. In 1931, when the state was

still experiencing an economic slump and the price for rubber, the main

primary produce of the state, was still very poor, many rubber estates were

closed or reduced their labour forces. This forced many Chinese to leave the

state. Even the smallholders who were the chief group of people to benefit

from the "Free-Passage" Scheme during the 1920s, felt the strain, and they

were now unable to continue bringing down their relatives or friends. Some

also returned to China. The total number of Chinese who arrived in the state

under the "Free-Passage" scheme dropped from 1,133 in 1930, to 395 in

1931. In 1932, there were only 92 arrivals, and 187 in 1933.

The number of Chinese emigrants who had arrived in Sabah on their own

account was almost ten times as many as those who came in under the

assisted scheme. Between 1930 and 1940, a total of 31,998 Chinese entered

the state on their own, compared to 3,859 Chinese entered the state under the

"Free-Passage" scheme. The overwhelming entry of free immigrants from

China was due to worsened conditions in southern China. By 1936, Japanese

military encroachments in China was already gaining momentum, many

decided to leave China to avoid the war and political turmoil, and to search

for better livelihood. 4,577 free-Chinese entered Sabah in 1936, and another

7,912 came in 1937. The sudden increase was also a result of the imposition

of a quota for entry into Hong Kong by the Hong Kong government. Faced

with the difficulty of gaining entry into Hong Kong, many Chinese then

decided to go to Sabah and Malaya.

In 1938, worried by its inability to check the inflow of undesirable

refugees from southern China and by the prospect of overstraining the

resources of the state, the North Borneo Company officials decided to limit

immigration. A requirement was imposed whereby a prospective immigrant

must be in possession of $ 10 to $ 70 for adults, and $ 3 to $ 10, for each

dependent minor. (6?) The requirements, considerably heavy in those days,

made Sabah an unattractive destination for those intending to emigrate,

many chose to go to other destinations. A year later, the flow of Chinese into

the state had slowed to a trickle.

67. "Notification No. 136", North Borneo Official Gazette, 21 April 1928.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

Chinese Migration to Sabah Before the Second World War 157

The year 1941 marked the end of mass entry of Chinese into Sabah. The

Asian phase of the Second World War had began at the end of that year. The

outbreak of the war had completely stopped the process of migration from

China to Sabah. Even though Chinese immigration into Sabah resumed for

the first few years after the end of the war, the number of arrivals was small,

and it stopped altogether a few years after China fell into the hands of the

Communist Party of China in 1949.

The Chinese were brought into Sabah in great numbers since the

beginning of North Borneo Company rule in 1881. Even though there were

already some Chinese in the state prior to 1881, their numbers were small.

And apart from the years when William Cowie was Chairman of the North

Borneo Company, Chinese entries into Sabah had always received support

from the North Borneo Company Administration. Immigration of Chinese

into Sabah also depended on the demand for labourers to undertake

agriculture activities. In turn, such demands also depended on the rise and

fall of prices for agricultural products in the world markets.

One important feature of Chinese immigration into Sabah is the attention

given by the North Borneo Company to attracting Chinese pioneers and

agriculturists. In order to attract these people, various schemes offering

attractive conditions such as land and financial assistance were introduced.

Among the most successful was the introduction of the Free Passage Scheme

in 1921. This was extremely successful in attracting the Hakka dialect groups,

who were mostly of peasant origins. This resulted in the increase of the

Hakkas to the extent that they became the largest dialect group in Sabah. The

presence of a northern Chinese community in Sabah also demonstrated the

eagerness of the North Borneo Company to procure Chinese labourers without

any form of provincial prejudice. Nonetheless, the majority of the Chinese in

Sabah originated from the two southern provinces of Guangdong and Fujian.

Even though mass Chinese entries into Sabah ceased a few years after the

Second World War, the number of Chinese who had entered Sabah prior to

the War numbered about 70,000, out of which more than 30,000 were

female. (68) In many ways, the large number of womenfolk in Sabah prior to

the War suggests that most of the Chinese in Sabah had decided to make

Sabah their permanent place of dwelling long ago.

68. As there was no census taken for 1941, the figure given was derived from an average

based on the 1931 and 1951 figures, also taking into consideration the four years'lull ingrowth

caused by the War. See L. W. Jones, A Report on the Census of Population held in 4 July

1951, London, 1953, p. 112.

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

158 Danny Wong Tze-Ken

Glossary

Baoan SiaTianbao

Baxian Teochiu

Cangxian Tianjin

Basel Missionary Society Wenan

Chan Pin Chung j$^J& Wuhua SU

Dong M Xingning ^

Dongguan ^fg Xu ^

Duyuan fflâ Yong Ah Kit

Fan ?g Yongqing

Fang ^ YuanShikai

Fuzhou Zhuang ^

Gong Zijin %£

Gu'an zongliyamen

Han $|

Honshu

Hebei

Huaxian

Huizhou M

Jinqiao j$ti

Jinghai ^?

Jingzhou ^

Lee Ah Pin

LiHongzhang 2p

Longchuan f|/[|

Meixian

Nanhai

Nie ^

Qingyuan If

Shenzhou

Shi ^

Archipel 58, Paris, 1999

You might also like

- The Chinese in Modern Malaya (Victor Purcell)Document72 pagesThe Chinese in Modern Malaya (Victor Purcell)zahin zainNo ratings yet

- SecretsDocument38 pagesSecretsDenial YoungNo ratings yet

- 《the Island of Formosa》Document822 pages《the Island of Formosa》Pei Chin100% (2)

- History of Laos Manich 2Document177 pagesHistory of Laos Manich 2Long HoàngNo ratings yet

- Sea Nomads 1Document12 pagesSea Nomads 1qpramukantoNo ratings yet

- History of SabahDocument50 pagesHistory of SabahJoy TagleNo ratings yet

- Chinese Cmnty in Surabaya, Claudine - SalmonDocument39 pagesChinese Cmnty in Surabaya, Claudine - SalmonStefano KwokNo ratings yet

- Palawan As A Sovereign State - Psu Study Committee OutputDocument48 pagesPalawan As A Sovereign State - Psu Study Committee OutputJoselito Alisuag100% (2)

- Remedi TOEFLDocument15 pagesRemedi TOEFLMuhammad FadhilNo ratings yet

- Quaker Oats & SnappleDocument5 pagesQuaker Oats & SnappleemmafaveNo ratings yet

- b12562890 Yan Qinghuang Vol2Document386 pagesb12562890 Yan Qinghuang Vol2Durga ArivanNo ratings yet

- Solheim On NusantaoDocument12 pagesSolheim On NusantaoJose Lester Correa DuriaNo ratings yet

- MODULE 1 Lesson 2Document27 pagesMODULE 1 Lesson 2Kiara Adelene GestoleNo ratings yet

- The Trans-Sumatra Trade and The Ethnicization of The BatakDocument44 pagesThe Trans-Sumatra Trade and The Ethnicization of The BatakDafner Siagian100% (1)

- La Communauté Chinoise de Surabaya. Essai D'histoire, Des Origines À La Crise de 1930Document88 pagesLa Communauté Chinoise de Surabaya. Essai D'histoire, Des Origines À La Crise de 1930rahardi teguhNo ratings yet

- Journal01 19 WangDocument13 pagesJournal01 19 WangLoki PagcorNo ratings yet

- Cabiao Nueva EcijaDocument8 pagesCabiao Nueva EcijaLisa MarshNo ratings yet

- The Documented History of The Kelabits of Northern SarawakDocument30 pagesThe Documented History of The Kelabits of Northern SarawakTamás VerebNo ratings yet

- Lou Marxis Gallevo Prof. Ruby Liwanag Iii-9 Bsse Philippine Development ExperienceDocument11 pagesLou Marxis Gallevo Prof. Ruby Liwanag Iii-9 Bsse Philippine Development ExperienceCj LowryNo ratings yet

- Draft: Do Not Cite Without Permission From The AuthorDocument14 pagesDraft: Do Not Cite Without Permission From The AuthorVincit Omnia VeritasNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Chinese CultureDocument20 pagesMalaysian Chinese CultureSherry Yong PkTianNo ratings yet

- Group 4 Badjau, Lumad, and Ata-Manobo Script: TulopDocument12 pagesGroup 4 Badjau, Lumad, and Ata-Manobo Script: TulopJunerey Hume Torres RodriguezNo ratings yet

- 7 TCR I 2 - Fernandez - Exploring The Pangasinan Cordillera Connection The Pangasinenses and The IbaloisDocument15 pages7 TCR I 2 - Fernandez - Exploring The Pangasinan Cordillera Connection The Pangasinenses and The IbaloisignasadrianeloveNo ratings yet

- Chinese in The PhilippinesDocument10 pagesChinese in The PhilippinesPamie Penelope BayogaNo ratings yet

- A Reconstruction of 15th Century Calatagan CommunityDocument15 pagesA Reconstruction of 15th Century Calatagan CommunityMariano PonceNo ratings yet

- Sao Noan Oo's Presentation at SOAS On The 24th. of November On 2108 Be Mai TaiDocument17 pagesSao Noan Oo's Presentation at SOAS On The 24th. of November On 2108 Be Mai TaitaisamyoneNo ratings yet

- Study of Chainese Lone Words in MalayDocument16 pagesStudy of Chainese Lone Words in MalayShaakir Mim100% (1)

- The Visayan Raiders of The China Coast SummaryDocument3 pagesThe Visayan Raiders of The China Coast SummaryPaculba Louigi IgdonNo ratings yet

- Module 1: Introduction To History: Learning ObjectivesDocument7 pagesModule 1: Introduction To History: Learning ObjectivesMariz Dioneda50% (2)

- Bijdragen Tot de Taal - Land - en Volkenkunde Journal of The HDocument44 pagesBijdragen Tot de Taal - Land - en Volkenkunde Journal of The HTengku MarianaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 3-6 MidtermsDocument34 pagesCHAPTER 3-6 MidtermsJonafe JuntillaNo ratings yet

- Singapore Landscape: A Historical Overview of Housing ChangeDocument16 pagesSingapore Landscape: A Historical Overview of Housing ChangeArnav DasaurNo ratings yet

- Precolonial PH in Sonming Records PDFDocument12 pagesPrecolonial PH in Sonming Records PDFJacob Walse-DomínguezNo ratings yet

- 1H-1-L4 - Rural Life - 2021Document21 pages1H-1-L4 - Rural Life - 2021你的小蘿莉No ratings yet

- Chung - Waqf Land in Singapore DraftDocument35 pagesChung - Waqf Land in Singapore DraftAchmad SahuriNo ratings yet

- Like The Early Ancestors of HumankindDocument6 pagesLike The Early Ancestors of HumankindGermaine AquinoNo ratings yet

- History of BatangasDocument5 pagesHistory of BatangasMixsz LlhAdyNo ratings yet

- Article Arch 0044-8613 1980 Num 19 1 1524Document19 pagesArticle Arch 0044-8613 1980 Num 19 1 1524anjangandak2932No ratings yet

- Hausa LandDocument362 pagesHausa LandMartin konoNo ratings yet

- Khmer Dan MalayDocument51 pagesKhmer Dan MalayHamdan YusoffNo ratings yet

- History of The PhilippinesDocument20 pagesHistory of The PhilippinesEechram Chang AlolodNo ratings yet

- The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891From EverandThe Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891No ratings yet

- "Lubo": Figure 1. Some of The Trading Products of The People of Lubao During The Pre-Colonial TimesDocument5 pages"Lubo": Figure 1. Some of The Trading Products of The People of Lubao During The Pre-Colonial TimesHaydee Fay GomezNo ratings yet

- Lntroduction.-The: Alfredo EvangelistaDocument17 pagesLntroduction.-The: Alfredo EvangelistaAnna Jewel LealNo ratings yet

- Tanauan-CityDocument25 pagesTanauan-CityRealie BorbeNo ratings yet

- Islam and Chinese - Denys LombardDocument18 pagesIslam and Chinese - Denys LombardkayralaNo ratings yet

- The Pre Hispanic PhilippinesDocument13 pagesThe Pre Hispanic PhilippinesNoel Sales BarcelonaNo ratings yet

- Nepal History As World HistoryDocument60 pagesNepal History As World HistoryslakheyNo ratings yet

- The Ili Rebellion: The Moslem Challenge To Chinese Authority in Xinjiang, 1944-1949Document296 pagesThe Ili Rebellion: The Moslem Challenge To Chinese Authority in Xinjiang, 1944-1949Justin JacobsNo ratings yet

- The Rhodesian HistoryDocument37 pagesThe Rhodesian HistoryNokuthula MoyoNo ratings yet

- Hansen - Valerie - The Impact of The Silk Road Trade On Local Community - The Turfan Oasis, 500-800Document28 pagesHansen - Valerie - The Impact of The Silk Road Trade On Local Community - The Turfan Oasis, 500-800Mehmet TezcanNo ratings yet

- MinsupalaDocument6 pagesMinsupalaFEDERICA ELLAGANo ratings yet

- Unit 5Document10 pagesUnit 5Kezia Rose SorongonNo ratings yet

- Taiwanese LiteratureDocument18 pagesTaiwanese LiteratureLance Joseph MurataNo ratings yet

- Document 1Document6 pagesDocument 1Kathleen Joy AbareNo ratings yet

- Writing The South Seas: Imagining The Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial LiteratureDocument45 pagesWriting The South Seas: Imagining The Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial LiteratureUniversity of Washington Press100% (1)