Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tamil Literature

Tamil Literature

Uploaded by

utp3196Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Tirukkural MalayalamDocument122 pagesTirukkural MalayalamAnil Sarngadharan100% (1)

- Telugu BooksDocument168 pagesTelugu BooksNava Grahaz57% (47)

- Legendary Society of Ancient TamilsDocument187 pagesLegendary Society of Ancient Tamilsdhiva0% (1)

- Journal of The Asiatic Society, 1963, Vol. V, No. 1 & 2Document202 pagesJournal of The Asiatic Society, 1963, Vol. V, No. 1 & 2vj_episteme100% (1)

- Bhattacharya Gaurinath - An Introduction To Classical SanskritDocument273 pagesBhattacharya Gaurinath - An Introduction To Classical Sanskritbrrhi100% (1)

- Sources of Ancient Indian HistoryDocument5 pagesSources of Ancient Indian HistoryRamita Udayashankar100% (2)

- Satakam and Slokas of Sri Kalahastiswara in Telugu With MeaningDocument37 pagesSatakam and Slokas of Sri Kalahastiswara in Telugu With Meaningsaaisun50% (2)

- TPM Telugu Songs 222 - 386Document162 pagesTPM Telugu Songs 222 - 386Manjunath S100% (3)

- Learn Telugu PDFDocument15 pagesLearn Telugu PDFதெய்வேந்திரன் தேனிNo ratings yet

- Numbers in KannadaDocument2 pagesNumbers in KannadaGera Amith Kumar59% (37)

- Early Tamil Literature and Society in UpDocument20 pagesEarly Tamil Literature and Society in UpDurai IlasunNo ratings yet

- Date of KautilyaDocument21 pagesDate of KautilyaPinaki ChandraNo ratings yet

- Sources Texts Epigraphic and Numismatic DataDocument25 pagesSources Texts Epigraphic and Numismatic Datachunmunsejal139No ratings yet

- Essays On Gupta CultureDocument3 pagesEssays On Gupta CultureTanushree Roy Paul100% (1)

- Bharatas Natyashastra PDFDocument8 pagesBharatas Natyashastra PDFClassical RevolutionaristNo ratings yet

- Sources Early MedDocument24 pagesSources Early MedShreya SinghNo ratings yet

- 23044957Document25 pages23044957SandraniNo ratings yet

- 5 A.R. Venkatachalapathy, Introduction' and 4 Cankam PoemsDocument32 pages5 A.R. Venkatachalapathy, Introduction' and 4 Cankam Poemskhushie1495No ratings yet

- 3 Sources of History MrunalDocument12 pages3 Sources of History MrunalRajaDurai RamakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Dimock Goddess of SnakesDocument16 pagesDimock Goddess of SnakeskaiyoomkhanNo ratings yet

- Viloma-Kavya - Journal ArticleDocument9 pagesViloma-Kavya - Journal Articlekairali123No ratings yet

- The Buddhist Conception of Kingship and Its Historical Manifestations: A Reply To SpiroDocument9 pagesThe Buddhist Conception of Kingship and Its Historical Manifestations: A Reply To SpiroTanya ChopraNo ratings yet

- Sample Answers Ch-3 and Ch-4Document8 pagesSample Answers Ch-3 and Ch-4vaibhavi jhaNo ratings yet

- Sangam AgeDocument11 pagesSangam AgeHarshitha EddalaNo ratings yet

- Bhart Hari: Bhartrhari Navigation Search Devanagari FL Sanskrit Sanskrit Sanskrit Grammar Spho A Sanskrit PoetryDocument11 pagesBhart Hari: Bhartrhari Navigation Search Devanagari FL Sanskrit Sanskrit Sanskrit Grammar Spho A Sanskrit PoetryvivekishuNo ratings yet

- The Purushasukta - Its Relation To The Caste SystemDocument11 pagesThe Purushasukta - Its Relation To The Caste Systemgoldspotter9841No ratings yet

- The Literary Scene in Marathi in 1971Document11 pagesThe Literary Scene in Marathi in 1971Reshma HussainNo ratings yet

- Understanding Indian History: Module - 1Document9 pagesUnderstanding Indian History: Module - 1Altaf Ul RehmanNo ratings yet

- Format. Hum - A Scientific Approach of Various Doctrines of Indian Knowledge Systems Through Poetic FormDocument8 pagesFormat. Hum - A Scientific Approach of Various Doctrines of Indian Knowledge Systems Through Poetic FormImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- The Early Bhakti Poets of Tamil Nadu-LibreDocument30 pagesThe Early Bhakti Poets of Tamil Nadu-Libresharath00No ratings yet

- The Engraving of Civilization in Malayalam LiteratureDocument3 pagesThe Engraving of Civilization in Malayalam LiteratureRajender BishtNo ratings yet

- 06 - Chapter 1Document26 pages06 - Chapter 1Ganesh Prasad KNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit Subhāṣita Saṃgraha-S in Old-Javanese and Tibetan (Ludwik Sternbach)Document45 pagesSanskrit Subhāṣita Saṃgraha-S in Old-Javanese and Tibetan (Ludwik Sternbach)Qian CaoNo ratings yet

- 05 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument17 pages05 - Chapter 1 PDFAãfréëd PàtèłNo ratings yet

- Art and Culture UpdatedDocument54 pagesArt and Culture Updatednaresh yadavNo ratings yet

- Hymns of The Alvars JMSCooperDocument111 pagesHymns of The Alvars JMSCooperHarsha AnanthramNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter4Document26 pages09 Chapter4Dharsana RathNo ratings yet

- Indian Literary Theory and CriticismDocument18 pagesIndian Literary Theory and CriticismAdwaith JayakumarNo ratings yet

- Indian History Through The Ages Medieval India: Module - 3Document27 pagesIndian History Through The Ages Medieval India: Module - 3madhugangulaNo ratings yet

- Manu V. Devadevan - The Historical Evolution of Literary Practices in Medieval Kerala CA 1200 To 1800 CEDocument357 pagesManu V. Devadevan - The Historical Evolution of Literary Practices in Medieval Kerala CA 1200 To 1800 CEsreenathpnrNo ratings yet

- The Writer's Class of Ancient India - A Study in Social MobilityDocument14 pagesThe Writer's Class of Ancient India - A Study in Social MobilityNishant SinghNo ratings yet

- Challenging Narratives of History and SexualityDocument38 pagesChallenging Narratives of History and SexualityAbhirami NairNo ratings yet

- Ananda Coomaraswamy - Review of Manimekhalai in Its Historical Setting by S. Krishnaswami AiyangarDocument3 pagesAnanda Coomaraswamy - Review of Manimekhalai in Its Historical Setting by S. Krishnaswami AiyangarManasNo ratings yet

- Craftsmen in Early Medieval Peninsular IndiaDocument36 pagesCraftsmen in Early Medieval Peninsular IndiaPriyanka MokkapatiNo ratings yet

- Gérard Colas - The Criticism and Transmission of Texts in Classical IndiaDocument13 pagesGérard Colas - The Criticism and Transmission of Texts in Classical Indiapkirály_11No ratings yet

- Hsslive Xii History CH 3 English SajeevanDocument4 pagesHsslive Xii History CH 3 English SajeevanAtul KumarNo ratings yet

- Digital Documentation of Buddhist Sites PDFDocument16 pagesDigital Documentation of Buddhist Sites PDFAdharsh ArchieNo ratings yet

- Avalokitesvara Tantric Connections in Cambodia and Campā Between The Tenth and Thirteenth CenturiesDocument26 pagesAvalokitesvara Tantric Connections in Cambodia and Campā Between The Tenth and Thirteenth Centurieslieungoc.sbs22No ratings yet

- Sources of Indian HistoryDocument9 pagesSources of Indian Historyabbas18No ratings yet

- Kajian Kakawin Calon Arang 22 November 2022Document8 pagesKajian Kakawin Calon Arang 22 November 2022Afif Bawa Santosa AsroriNo ratings yet

- Final FormatDocument32 pagesFinal FormatTanusri SinhaNo ratings yet

- Literary SourcesDocument7 pagesLiterary SourcesAnushka YaduwanshiNo ratings yet

- Sources of Ancient Indian HistoryDocument8 pagesSources of Ancient Indian HistoryHassan AbidNo ratings yet

- Aircraft and Robots in An Ancient Indian Text - Atlantis Rising Magazine LibraryDocument4 pagesAircraft and Robots in An Ancient Indian Text - Atlantis Rising Magazine LibraryNikšaNo ratings yet

- 017 Bisakha Goswami PoskeDocument6 pages017 Bisakha Goswami PoskeMadokaram Prashanth IyengarNo ratings yet

- Social Life in Northern India A. D. 600 To1000 by Brij Narain SharmaDocument3 pagesSocial Life in Northern India A. D. 600 To1000 by Brij Narain SharmaAtmavidya1008No ratings yet

- Early Indian Notions of HistoryDocument13 pagesEarly Indian Notions of HistoryRoshan N WahengbamNo ratings yet

- Panchatantrapdf AA 76-2 PDFDocument65 pagesPanchatantrapdf AA 76-2 PDFSubraman Krishna kanth MunukutlaNo ratings yet

- ALCHIMIA-BENGALI-0-Article Text-377-7-10-20180420 PDFDocument34 pagesALCHIMIA-BENGALI-0-Article Text-377-7-10-20180420 PDFgtnlmnc99235No ratings yet

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 4From EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 4Lucas den BoerNo ratings yet

- Tattvabodha (Volume VII): Essays from the Lecture Series of the National Mission for ManuscriptsFrom EverandTattvabodha (Volume VII): Essays from the Lecture Series of the National Mission for ManuscriptsNo ratings yet

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 2From EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 2No ratings yet

- T.V. Reddy's Fleeting Bubbles: An Indian InterpretationFrom EverandT.V. Reddy's Fleeting Bubbles: An Indian InterpretationNo ratings yet

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 1From EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 1Nina MirnigNo ratings yet

- ManimekalaiDocument117 pagesManimekalaiSundararajan JeyaramanNo ratings yet

- Topic: Tamil Syllabus (Code:006) Class - IX (2021-2022) Term - 1 (IYAL 1 To 3)Document6 pagesTopic: Tamil Syllabus (Code:006) Class - IX (2021-2022) Term - 1 (IYAL 1 To 3)Rajnesh vanavarajanNo ratings yet

- Retail Scorecard NewDocument3,615 pagesRetail Scorecard NewND ProductsNo ratings yet

- SL No. Title and Author SubjectDocument12 pagesSL No. Title and Author SubjectAumFormlessNo ratings yet

- GTE February 2023 ResultDocument3 pagesGTE February 2023 ResultAnand RajaNo ratings yet

- Pure Tamil Baby Names For Girls Pure121 PDFDocument6 pagesPure Tamil Baby Names For Girls Pure121 PDFArun PrakashNo ratings yet

- Andhra Nayaka SatakamDocument47 pagesAndhra Nayaka SatakamnageshwarBI50% (2)

- Tamil Literature Sangam Age To Contemporary TimesDocument14 pagesTamil Literature Sangam Age To Contemporary Timesgokul viratNo ratings yet

- TamilCube Mooligai Marmam PDFDocument88 pagesTamilCube Mooligai Marmam PDFSenthil KumarNo ratings yet

- Purananuru: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument7 pagesPurananuru: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchVanitha CNo ratings yet

- TeluguDocument4 pagesTeluguVakamalla SubbareddyNo ratings yet

- KMSC LL LLL LLLLLLL I LFLFLLLL: J DGD S) D-Ugr-2Document10 pagesKMSC LL LLL LLLLLLL I LFLFLLLL: J DGD S) D-Ugr-2Kevin ArnoldNo ratings yet

- Nirvagam Iii, Iv Sem - Bba BHM Bca BSW Bba (T&T)Document92 pagesNirvagam Iii, Iv Sem - Bba BHM Bca BSW Bba (T&T)SanjuNo ratings yet

- English To Tamil DictionaryDocument4 pagesEnglish To Tamil DictionaryVidhya Raghavan100% (2)

- 1810 MaruthiDocument86 pages1810 Maruthideva nesanNo ratings yet

- Discussions About Vandanam and VanakkamDocument7 pagesDiscussions About Vandanam and VanakkamRavi Vararo100% (1)

- Byjus 05 02 2022Document1 pageByjus 05 02 2022Nandini N RNo ratings yet

- Andhra Nayaka SatakamDocument47 pagesAndhra Nayaka Satakamsirishadeepthi9840No ratings yet

- Pure Tamil Baby Names For Girls Pure PDFDocument6 pagesPure Tamil Baby Names For Girls Pure PDFArun PrakashNo ratings yet

- నా పెళ్లాలు 8Document8 pagesనా పెళ్లాలు 8Anonymous 9nRdJN8cW20% (5)

- Who Planted The Bombs in Chennai TrainDocument4 pagesWho Planted The Bombs in Chennai TrainThavam RatnaNo ratings yet

- Current Titles PriDocument69 pagesCurrent Titles Prirasia.kangNo ratings yet

- Power Point PresentationDocument15 pagesPower Point PresentationDivya PsNo ratings yet

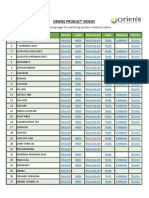

- Oriens Product Video LinksDocument2 pagesOriens Product Video LinksImthiyas ARM100% (1)

Tamil Literature

Tamil Literature

Uploaded by

utp3196Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tamil Literature

Tamil Literature

Uploaded by

utp3196Copyright:

Available Formats

THE MAKING OF THE ANCIENT TAMIL LITERARY CANON

Author(s): V. Rajesh

Source: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress , 2006-2007, Vol. 67 (2006-2007), pp.

153-161

Published by: Indian History Congress

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44147932

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Indian History Congress is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE MAKING OF THE ANCIENT TAMIL

LITERARY CANON

V. Rajesh

In a multi-cultural and pluralist society like India, when litera

production is associated with power, the notion of canon is histo

contingent. It has been argued that the wide array of overlapp

institutional practices like writing commentaries, citing sourc

reference confers a literary text a canonical status.1 In other words

levels of objectification that a literary text undergoes in tradition c

it a canonical status. The reasons for objectification may differ

scholarly concern to that of an assertion of power by an emerging

elite. It was the Orientalists who took up the canonization of cl

Sanskrit texts during the colonial period. A normative value was

subsequently established and it was widely believed that the canons thus

produced represent the total literary ethos and the essentials of Indian

culture. More than any other factor, it was the print culture that

established the fixity and closure for literary texts, which in pre-modern

period was more fluid. This does not however, mean that it was left

uncontested. Here, we seek to demonstrate that the notion of 'Sanganv

literary canon is historically contingent or to state more clearly, shaped

by the contemporary needs. At the first instance, it will be argued how

the Tamil literary tradition itself was historically shaped, and secondly

it will be suggested how this process effected the modern understanding

of the Tamil literary canon. The aim here is not to question in any way

the chronology or the integrity of the text but aspects like the

commissions and omissions, interpolations and marginalisation in the

making of a canon will be highlighted.

The 'Sangam' literature constitutes Ettutokai (Eight anthologies)

and Pattupattu (Ten songs) dated to first three centuries of the Christian

era. Some scholars are averse to include the latter as a part of 'Sangam'

literature since the tradition itself did not sanction.2 'Sangam' means an

assembly. The first detailed account of the existence of the assembly of

poets and their works in Tamil tradition emerges in the 8lh century A.D.

commentary to the grammatical work Iraiyanar Akapporul. The

commentary states that the ancestors of the Pandya kings established

three literary academies where poets, gods and sages participated and

contributed poems. The claims made for the number of years for each

academy was enormous which goes beyond the comprehension of

modern historical understanding.3 The works of the first two academies

were lost and for the third the commentary outline the following,

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

154 IHC: Proceedings , 67th Session , 2006-07

Netuntokainanuru, Kuruntokainanuru, Narrinainanuru, Purananuru,

Ainkurunuru, Patirrupattu, Nurraimpatu Kali, Elupalu Paripatal and

Tolkappiyam.

As we have seen above, the commentary outlined only the Ettutokai

and the grammatical text Tolkappiyam as third 'Sangalli' works but did

not include Pattupattu. Some of the poets who composed poems in

Ettutokai were the authors of the Pattupattu. In that sense, it is enigmatic

as to why the 8th century commentary must include the former as works

of third Sangam while leaving out the latter. Was Pattupattu not available

to the 8lh century commentator? According to K.N. Sivaraja Pillai, the

commentary to Iraiyanar Akapporul was orally transmitted for ten

generations and that it was one Nilakantan of Muciri who had actually

put it down in writing in 8lh century A.D.4 Though, the names of the

individual anthologies were mentioned as part of 'Sangam' literature,

no where in the poems of the anthologies we find any evidence of the

assembly of poets and the concomitant production of literature. The term

'Sangam' , as Zvelebil argues was appropriated from the Jainas who

founded the Dravida Sangam.5

'Tokai' means anthology, which presupposes a collection and

compilation. Thus Ettutokai means eight anthologies. Each of the

collections in Ettutokai can be understood as an anthology. Tokai in

Kuruntokai means an anthology of short four hundred. Thus, in

Kuruntokai, we have four hundred unique lyrical love poems in aciriyam

meter composed by 203 poets. The tradition has preserved, apart from

the names of the poets who composed the poems, the names of the

compilers and patrons were also preserved. Thus, Purikko compiled

Kuruntokai and the tradition also informs us that the poems were

compiled based on the number of lines. For example, the poems of

Kuruntokai were compiled based on the length of four to eight lines.

Similarly, Narrinai comprises the poems of length in between Kuruntokai

and Akananuru i.e. 9-12 lines. The name of the compiler of this anthology

is not known but the tradition informs us that it was commissioned by

Pannatu tanta Pantiyan Maran Valuti. That the poems of Narrinai were

composed in aciriyam meter is commonly known. Akananuru means

four hundred poems on 'Akam'. Urutirra Canmar compiled it under the

patronage of Pantiyan Ukkirap Peru valuti. The length of the poems ranges

from 1 3 to 3 1 lines. The four hundred poems were composed in aciriyam

meter.

The poems, written and recited from lsl century A.D. onwards were

compiled around 3rd century A.D. According to Kamil Zvelebil, 'the

first compilation was not much removed in time from the stage of actual

composition of some of the poems: it may even have been

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient India 155

contemporaneous with it.'6 At the e

information about names of compilers

was compiled by Madurai Uppurikuti

the commission of Pantiyan Ukkira

Purananuru 21, 367. Commenting on

J.R. Marr observes that, 'If such tra

conclude that these anthologies were co

when these kings lived, and possibly

of the personages who figure in the po

and puram'.7 It is pertinent to underst

poems into an anthology form aroun

attributes this compilation to the di

consequently, the consolidation of the

he argues that since 'Sangam' poems

'literacy', the oral poems, which wer

selected, compiled and put down int

might have been a factor for compilin

of compilation i.e., based on number

there was a consciousness of the exis

compilation reflect the systematizat

we are not sure whether the compile

compiler had selected the poems fro

have to suppose that the sources we a

was considered to be essential by th

society. We do not have any evidence

Purananuru. Patirruppattu is exclusivel

in all probability it must have been com

Chera chiefs. Kalitokai and Paripatal,

is a part of eight anthologies, it is n

scholarly circles that the two antholog

of post-Sangam period (5lh-7lh A.D

treating these two anthologies as lat

Indo- Aryan loanwords with thought c

of the anthologies.10 Thus, the six o

been compiled around 3rd century A

content and thematic unity of these

fact it represents simultaneity of pr

As already stated, it was the comm

grammatical text Iraiyanar Akapporu

the existence of łSangam' According

the grammar is the lord Siva himself.

time when there was fervor of Saiva and Vaishnava bhakti in the Tamil

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

156 IHC: Proceedings , 67th Session , 2006-67

land. Moreover, contestation against the sramanic religion was endemic

to the period under discussion. The author of the commentary was very

much conscious of the existence of 'Dravida Sanganť of Jainas, though

there is no direct allusion to it. The commentary, according to K.

Sivathamby, 'attempts to take over an obviously Jaina and Buddhist

institution (sanga) and give it a Hindu form and content'.11 The references

to the existence of only the individual anthologies in the commentary

i.e, Netuntokainanuru, Kuruntokainanuru, Narrinainanuru, Purananuru,

Ainkurunuru, Patirrupattu, Nurraimpattukali and Elupatu Paripatal

indicate a fact that these individual anthologies were not yet collected

together into super anthology - the Ettutokai. The process of

anthologisation was intimately connected to the politics of identity

assertion and hence it is pertinent to address the issues of legitimization

by the newly emerging ruling elite.

The invocatory poems to the five out of eight anthologies require

considerable attention as it may relate to the process of anthologisation.

Akananuru, Kuruntokai, Narrinai, Ainkurunuru and Puranauru contain

an invocatory poem written by Paratam Patiya Peruntevanar. The subject

matter of these invocatory verses is completely alien to the rest of the

poems in the anthologies. Akananuru has an invocatory poem in praise

of Siva. So is also the case with Purananuru. Narrinai and Ainkurunuru

which have an invocatory poem in praise of Vishnu. Kuruntokai alone

contains an invocatory poem in praise of Murukan. John Ralston Marr

has shown that these invocatory poems are alien to the subject matter of

the rest of the poems in the respective five anthologies.12 The preface or

the invocatory poem in the Patirupattu is missing and it can only be

speculated that it might have been written for this anthology too. The

rest two anthologies Kalitokai and Paripatal did not contain any

invocatory poems written by Peruntevenar. Whether Kalitokai and

Paripatal were composed or not at a time when Peruntevanar wrote

invocatory poems for the rest of the anthologies are open to doubt. But

there is a general agreement, as already discussed among scholars that

these two works are later than the rest of the anthologies. Marr has

convincingly argued that Peruntevenar must have been contemporaneous

with or later than the 9lh century A.D. Pallava Nandivarman.13 It is rather

anachronistic that M.G.S. Narayanan treats these invocatory verses as a

part of the original anthology in outlining the Vedic, Sastric and Puranic

elements in the Cankam period.14 Even the secular nature of the Sangam

anthologies were attributed a religious fervour when invocatory verses

were written during early medieval Tamilakam. These attempts reflect

the case that bhakti was a dominant ideology during early medieval

Tamilakam. The historiography on Tamil bhakti religion in one way or

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient India 157

the other emphasized the connectio

poetry with the Sangam poems in term

employed for the composition of the p

their songs based on Akam and Puram

though the varying thought content

poets must have mastered the classic

back to the question of the availability

period of existence.

It has been argued in the nationali

period in the Tamil history is consid

century A.D.). The Kalabhras patron

country there was a disruption of text

conventions. Ethical texts were pro

stressed on peace, virtue and morali

witnessed a break under the Jain pat

and songs were condemned by Jaina

disruption of bardic tradition during

country.16 There is a story in the comm

which states that the grammar was wr

because of the absence of men spe

(poetics) of the classical 'Sangam' liter

from outside the Pandya country wh

men specialized in Col (orthography)

rationale for the legend is to legitim

patronized poetics associated with

Iraiyanar Kalaviyal. It must be under

discovered the grammar written by lo

according to the story. In other wor

newly emerging elite groups were a

invocatory verses written to the clas

the deliberate stripping of some of th

the attempts of the newly emerg

Tamilakam. The contestation against th

from the attempts that were made as

made in the verses of the Saiva and Vaishnava saints. Buddhists and

Jains countered these attacks and it can be gleaned from the text

production from their religious viewpoint. Thus, in Viracoliyam, the

author who was a Mahayanist stated that it was Avalokiteshwara who

gave Tamil to Agasthya.17

In the epigraphical textual tradition of Pandyas too, we find the

allusion to 'Sangam*. In the Tamil portion of the Dalavaypuram copper

plates of the early Pandyas, we find allusion to the establishment of

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

158 IHC: Proceedings , 67th Session, 2006-07

'Sanganť by the ancestors of the Pandyas.1R In the larger Cinnamanur

plates, we find the allusion to the establishment of 'Sangam' by Pandyas

and also the translation of Mahabharata into Tamil.19 It has been argued

that an inscription from Ramnad district published in Madras

Epigraphisťs Report [No. 334] alludes to the ancestor of Etticatan, who

was a poet who sat on the 'Sangam' bench.20 Thus, both the literary and

the epigraphical texts produced during early medieval Tamilakam

represent a sense of belonging to the classical Tamil literature. In thought

content and ideology, both literature and inscriptions of early medieval

Tamilakam represent an alienating distanciation from the classical Tamil

literature.21

By the end of early medieval period (around 1 2th century A.D.), Tamil

society became complex. From 12lh century A.D., there was a

proliferation of the institutions of pedagogical learning located at the

sacred sectarian centres. Both Saivite and Vaishnavite hagiographical

works were produced by then and there was a need to comment on the

text. Commentary (Urai) presupposes the existence of text (Mulam).

The cultural milieu of these commentators was different from that of

the original text. In the process of the comprehending of the meaning

for certain verses, the commentators disagreed. But there was an attempt

at systematizing the knowledge during the medieval period.

Commentaries often carry the subjective bias of the commentator, since

the commentator may be associated with a particular sect.22 While

commenting the commentator had to cite references and sources. U. V.

Swaminatha Iyer while delivering the lecture on Arachi (research) in

early 20lh century stated that in his life as a researcher, he understood

the existence of verses (mulam) from commentary (Urai) and

commentary (Urai) from verses (mulam).23 Thanks to the medieval

commentators whose systematization of knowledge helped modern

scholars like U. V, Saminatha Iyer to re-discover the texts from oblivion.

In Indian tradition, even the commentaries were oral in origin. It was

formulaic suited for memorization and recollection. Zvelebil has shown

a verse from Iraiyanar Akapporul's commentary, as to how this

commentary was orally transmitted ( ini urai natantu vantavaru

collutum ).24

The individual anthologies that we noticed in Iraiyanar Akapporul's

commentary, in the course of time around 10th - 1 1th centuries A.D, were

collected together and made into a super anthology the Ettutokai. It was

first mentioned, along with Pattupattu (Ten songs) in Peraciriyar's

commentary on Tolkappiyam's Porulatikaram (Poetics). Zvelebil

attributes the chronology of the commentary to around 1 3lh century A.D.25

Around the same period, Mayilainathar's commentary on the

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient India 1 59

grammatical text Nannul also alludes

anthologies Ettutokai and Pattupattu.

scholars of final redaction and codification of classical Tamil literature.

The anthologies must have attained the present shape at the point in

time under discussion. But having said that, it is extremely difficult to

locate the interpolations in the original text. The internal uniformity in

terms of meter, language and theme is remarkable and there is no question

of interpolations. The redactors faithfully copied the text and they only

super anthologized. U.V. Swaminatha Iyer stated that in those days, the

commentators showed great respect to the verses (Mulam) and they were

trained in copying it exactly without mistake, though there was a freedom

of commenting on the verses.26

There were number of commentators whose commentary on the

grammatical text Tolkappiyam deserves discussion. It was felt necessary

by the medieval linguists to master the language for pedagogical

purposes. Series of commentaries were written, so that pedagogical

exposition could be made without much difficulty. It was around 11th

century A.D, that the first commentary to Tolkappiyam was written by

llampuranar. In his commentary there are no allusions to the existence

of super anthologies, the Ettutokai and Pattupattu. The individual

anthologies must have been redacted and codified after his period. If it

were in existence, we would not expect great commentators like

llampuranar for not mentioning it. Naccinarkkiniyar commented apart

from Pattupattu on the first two full books and five chapters to the third

book of Tolkappiyam. He must have been a contemporary of

Parimelalakar and thus can be dated to 14th century A.D. Apart from

llampuranar and Naccinarkkiniyar, Cenavaraiyar (1 3th c.), Peraciyar ( 1 2th-

13th), Teyvaccilaiyar and Kallatar (16lh -17th c.) also commented on a

few portions of Tolkappiyam. Though old anonymous commentaries exist

for the individual anthologies of Ettutokai, it is enigmatic as to why it

was not commented in detail like Tolkappiyam. Moreover, except for

Kuruntokai, the names of the commentators who wrote commentaries

for the rest of the anthologies are not available. In medieval period,

primacy was given to religious texts and grammatical works whereas

earlier secular literatures like 'Sangam' literature was sidelined and not

recommended for pedagogical learning. For Ainkurunuru, Patirrupattu,

Akananuru and Purananuru, we have old anonymous commentaries in

fragments. No conclusive dates have been established for these

anonymous commentaries so far. Only for Kuruntokai, for the first 380

poems, we have evidence that Peraciriyar wrote commentary, who lived

around 12th -13th centuries A.D. For the rest 20 poems in Kuruntokai, U.

V. Swaminatha Iyer stated that Naccinarkinniyar of the 14lh century A.D

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

160 IHC: Proceedings , 67th Session , 2006-07

wrote a commentary.27 But unfortunately, both these commentaries are

not available for us today. When U. V. Swaminatha Iyer and Damodaram

Pillai re-discovered the classical Tamil texts, they retained the old

anonymous commentaries and also v/rote full detailed commentaries

wherever they felt it necessary. Thus, the making of the ancient Tamil

literary canon was intimately tied to the needs of the time.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1 . A.R. Venkatachalapathy, 'In Print, On the Net: Tamil Literary Canon in the Colo

and Post-Colonial Worlds' in Suman Gupta, Tapan Basu and Subarno Banerji (eds

India in the Age of Globalisation : Contemporary Discourses and Texts , Neh

Memorial Museum and Library, 2003, p. 135.

2. John Ralston Marr, The Eight Anthologies: A Study in Early Tamil Literatu

Institute of Asian Studies, Madras, 1985, p. 7.

3. Thus the first Cankam lasted for 4440 years and the second for 3700 years wh

third Cankam for 1850 years. See K.R. Govindaraja Mudaliyar and M.V.

Venugopala Pillai (ed.), Kalaviyal ennum Iariyanar Akapporul mulamum,

Nakkiranar Uraiyum , 1939, pp. 5-7.

4. K.N. Sivaraja Pillai, Chronology of Early Tamils , University of Madras, 1932, p.

19.

5. Kamil V. Zvelebil, The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India ,

Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1973, p. 48.

6. Quoted in K. Sivathamby's, Literary History in Tamil. A Historiographical Analysis ,

Tamil University, Tanjavur, 1986, p. 32.

7. John Ralston Marr, op. cit., 1985, p. 331.

8. K. Sivathamby, op. cit., 1986, p. 33.

9. Ibid., p. 32.

10. Kamil Zvelebil, op. cit., 1973, pp. 121-130.

11. K. Sivathamby, op. cit., 1986, p. 35.

12. John Ralston Marr, op. cit., 1985, p. 71.

13. Ibid. p. 72.

14. M.G.S. Narayanan, 'The Vedic-Puranic-Sastric Element in Sangam Society and

Culture' , Proceedings of the Indian History Congress , 36th Session, Aligarh, 1975,

p.78.

15. A.K. Ramanujan and Norman Cutler, 'From Classicism to Bhakti* in Vinay

Dharwadkar (ed.), The Collected Essays of A.K. Ramnujan , Oxford University Press,

2001, pp. 232-259; Indira V. Peterson, Poems to Siva: The Hymns of the Tamil

Saints, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1989, p. 84; Friedhelm Hardy, Viraha-

Bhakti : The Early History of Krsna Devotion in South India, Oxford University

Press, Delhi, 1983, p. 276.

16. M. Arunachalam, The Kalabhras in the Pandya country and Their Impact on the

Life and Letters There, University of Madras, 1979, pp. 84-90.

17. K. Sivathamby, op. cit., 1986, p. 36.

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ancient India 161

18. Dalavaypuram Copper Plates, Tamil Portio

of the Early Pandyas c 300 B. C to 984 A.Dt

2002, pp. 74-75.

19. Cinnamanur Plates V. 102-104, Ibid. p. 1

20. Kamil V. Zvelebil, Tamil Literature , Leid

21 . 'Sense of Belonging' and 'Alienating Dist

employed by Paul Ricoeur in understanding t

see Paul Ricoeur, Hermeneutics and the Hum

J. Thompson, Cambridge University Press

22. For an excellent analysis of medieval and

Tirukkural text see, Norman Cutler, 'Int

Commentary in the Creation of a Text 'JA

23. U. V. Swaminathier, Canka Tamizhum Pirka

Library, 1929, p. 144.

24. Kamil V. Zvelebil, op. cit., 1973, p.249.

25. Ibid., p. 25.

26. U. V. Swaminathier, op. cit., 1929, p. 14

27. See preface in U. V. Swaminathier's (ed.),

first published 1973.

This content downloaded from

205.253.37.196 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 09:56:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Tirukkural MalayalamDocument122 pagesTirukkural MalayalamAnil Sarngadharan100% (1)

- Telugu BooksDocument168 pagesTelugu BooksNava Grahaz57% (47)

- Legendary Society of Ancient TamilsDocument187 pagesLegendary Society of Ancient Tamilsdhiva0% (1)

- Journal of The Asiatic Society, 1963, Vol. V, No. 1 & 2Document202 pagesJournal of The Asiatic Society, 1963, Vol. V, No. 1 & 2vj_episteme100% (1)

- Bhattacharya Gaurinath - An Introduction To Classical SanskritDocument273 pagesBhattacharya Gaurinath - An Introduction To Classical Sanskritbrrhi100% (1)

- Sources of Ancient Indian HistoryDocument5 pagesSources of Ancient Indian HistoryRamita Udayashankar100% (2)

- Satakam and Slokas of Sri Kalahastiswara in Telugu With MeaningDocument37 pagesSatakam and Slokas of Sri Kalahastiswara in Telugu With Meaningsaaisun50% (2)

- TPM Telugu Songs 222 - 386Document162 pagesTPM Telugu Songs 222 - 386Manjunath S100% (3)

- Learn Telugu PDFDocument15 pagesLearn Telugu PDFதெய்வேந்திரன் தேனிNo ratings yet

- Numbers in KannadaDocument2 pagesNumbers in KannadaGera Amith Kumar59% (37)

- Early Tamil Literature and Society in UpDocument20 pagesEarly Tamil Literature and Society in UpDurai IlasunNo ratings yet

- Date of KautilyaDocument21 pagesDate of KautilyaPinaki ChandraNo ratings yet

- Sources Texts Epigraphic and Numismatic DataDocument25 pagesSources Texts Epigraphic and Numismatic Datachunmunsejal139No ratings yet

- Essays On Gupta CultureDocument3 pagesEssays On Gupta CultureTanushree Roy Paul100% (1)

- Bharatas Natyashastra PDFDocument8 pagesBharatas Natyashastra PDFClassical RevolutionaristNo ratings yet

- Sources Early MedDocument24 pagesSources Early MedShreya SinghNo ratings yet

- 23044957Document25 pages23044957SandraniNo ratings yet

- 5 A.R. Venkatachalapathy, Introduction' and 4 Cankam PoemsDocument32 pages5 A.R. Venkatachalapathy, Introduction' and 4 Cankam Poemskhushie1495No ratings yet

- 3 Sources of History MrunalDocument12 pages3 Sources of History MrunalRajaDurai RamakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Dimock Goddess of SnakesDocument16 pagesDimock Goddess of SnakeskaiyoomkhanNo ratings yet

- Viloma-Kavya - Journal ArticleDocument9 pagesViloma-Kavya - Journal Articlekairali123No ratings yet

- The Buddhist Conception of Kingship and Its Historical Manifestations: A Reply To SpiroDocument9 pagesThe Buddhist Conception of Kingship and Its Historical Manifestations: A Reply To SpiroTanya ChopraNo ratings yet

- Sample Answers Ch-3 and Ch-4Document8 pagesSample Answers Ch-3 and Ch-4vaibhavi jhaNo ratings yet

- Sangam AgeDocument11 pagesSangam AgeHarshitha EddalaNo ratings yet

- Bhart Hari: Bhartrhari Navigation Search Devanagari FL Sanskrit Sanskrit Sanskrit Grammar Spho A Sanskrit PoetryDocument11 pagesBhart Hari: Bhartrhari Navigation Search Devanagari FL Sanskrit Sanskrit Sanskrit Grammar Spho A Sanskrit PoetryvivekishuNo ratings yet

- The Purushasukta - Its Relation To The Caste SystemDocument11 pagesThe Purushasukta - Its Relation To The Caste Systemgoldspotter9841No ratings yet

- The Literary Scene in Marathi in 1971Document11 pagesThe Literary Scene in Marathi in 1971Reshma HussainNo ratings yet

- Understanding Indian History: Module - 1Document9 pagesUnderstanding Indian History: Module - 1Altaf Ul RehmanNo ratings yet

- Format. Hum - A Scientific Approach of Various Doctrines of Indian Knowledge Systems Through Poetic FormDocument8 pagesFormat. Hum - A Scientific Approach of Various Doctrines of Indian Knowledge Systems Through Poetic FormImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- The Early Bhakti Poets of Tamil Nadu-LibreDocument30 pagesThe Early Bhakti Poets of Tamil Nadu-Libresharath00No ratings yet

- The Engraving of Civilization in Malayalam LiteratureDocument3 pagesThe Engraving of Civilization in Malayalam LiteratureRajender BishtNo ratings yet

- 06 - Chapter 1Document26 pages06 - Chapter 1Ganesh Prasad KNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit Subhāṣita Saṃgraha-S in Old-Javanese and Tibetan (Ludwik Sternbach)Document45 pagesSanskrit Subhāṣita Saṃgraha-S in Old-Javanese and Tibetan (Ludwik Sternbach)Qian CaoNo ratings yet

- 05 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument17 pages05 - Chapter 1 PDFAãfréëd PàtèłNo ratings yet

- Art and Culture UpdatedDocument54 pagesArt and Culture Updatednaresh yadavNo ratings yet

- Hymns of The Alvars JMSCooperDocument111 pagesHymns of The Alvars JMSCooperHarsha AnanthramNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter4Document26 pages09 Chapter4Dharsana RathNo ratings yet

- Indian Literary Theory and CriticismDocument18 pagesIndian Literary Theory and CriticismAdwaith JayakumarNo ratings yet

- Indian History Through The Ages Medieval India: Module - 3Document27 pagesIndian History Through The Ages Medieval India: Module - 3madhugangulaNo ratings yet

- Manu V. Devadevan - The Historical Evolution of Literary Practices in Medieval Kerala CA 1200 To 1800 CEDocument357 pagesManu V. Devadevan - The Historical Evolution of Literary Practices in Medieval Kerala CA 1200 To 1800 CEsreenathpnrNo ratings yet

- The Writer's Class of Ancient India - A Study in Social MobilityDocument14 pagesThe Writer's Class of Ancient India - A Study in Social MobilityNishant SinghNo ratings yet

- Challenging Narratives of History and SexualityDocument38 pagesChallenging Narratives of History and SexualityAbhirami NairNo ratings yet

- Ananda Coomaraswamy - Review of Manimekhalai in Its Historical Setting by S. Krishnaswami AiyangarDocument3 pagesAnanda Coomaraswamy - Review of Manimekhalai in Its Historical Setting by S. Krishnaswami AiyangarManasNo ratings yet

- Craftsmen in Early Medieval Peninsular IndiaDocument36 pagesCraftsmen in Early Medieval Peninsular IndiaPriyanka MokkapatiNo ratings yet

- Gérard Colas - The Criticism and Transmission of Texts in Classical IndiaDocument13 pagesGérard Colas - The Criticism and Transmission of Texts in Classical Indiapkirály_11No ratings yet

- Hsslive Xii History CH 3 English SajeevanDocument4 pagesHsslive Xii History CH 3 English SajeevanAtul KumarNo ratings yet

- Digital Documentation of Buddhist Sites PDFDocument16 pagesDigital Documentation of Buddhist Sites PDFAdharsh ArchieNo ratings yet

- Avalokitesvara Tantric Connections in Cambodia and Campā Between The Tenth and Thirteenth CenturiesDocument26 pagesAvalokitesvara Tantric Connections in Cambodia and Campā Between The Tenth and Thirteenth Centurieslieungoc.sbs22No ratings yet

- Sources of Indian HistoryDocument9 pagesSources of Indian Historyabbas18No ratings yet

- Kajian Kakawin Calon Arang 22 November 2022Document8 pagesKajian Kakawin Calon Arang 22 November 2022Afif Bawa Santosa AsroriNo ratings yet

- Final FormatDocument32 pagesFinal FormatTanusri SinhaNo ratings yet

- Literary SourcesDocument7 pagesLiterary SourcesAnushka YaduwanshiNo ratings yet

- Sources of Ancient Indian HistoryDocument8 pagesSources of Ancient Indian HistoryHassan AbidNo ratings yet

- Aircraft and Robots in An Ancient Indian Text - Atlantis Rising Magazine LibraryDocument4 pagesAircraft and Robots in An Ancient Indian Text - Atlantis Rising Magazine LibraryNikšaNo ratings yet

- 017 Bisakha Goswami PoskeDocument6 pages017 Bisakha Goswami PoskeMadokaram Prashanth IyengarNo ratings yet

- Social Life in Northern India A. D. 600 To1000 by Brij Narain SharmaDocument3 pagesSocial Life in Northern India A. D. 600 To1000 by Brij Narain SharmaAtmavidya1008No ratings yet

- Early Indian Notions of HistoryDocument13 pagesEarly Indian Notions of HistoryRoshan N WahengbamNo ratings yet

- Panchatantrapdf AA 76-2 PDFDocument65 pagesPanchatantrapdf AA 76-2 PDFSubraman Krishna kanth MunukutlaNo ratings yet

- ALCHIMIA-BENGALI-0-Article Text-377-7-10-20180420 PDFDocument34 pagesALCHIMIA-BENGALI-0-Article Text-377-7-10-20180420 PDFgtnlmnc99235No ratings yet

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 4From EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 4Lucas den BoerNo ratings yet

- Tattvabodha (Volume VII): Essays from the Lecture Series of the National Mission for ManuscriptsFrom EverandTattvabodha (Volume VII): Essays from the Lecture Series of the National Mission for ManuscriptsNo ratings yet

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 2From EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 2No ratings yet

- T.V. Reddy's Fleeting Bubbles: An Indian InterpretationFrom EverandT.V. Reddy's Fleeting Bubbles: An Indian InterpretationNo ratings yet

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 1From EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 1Nina MirnigNo ratings yet

- ManimekalaiDocument117 pagesManimekalaiSundararajan JeyaramanNo ratings yet

- Topic: Tamil Syllabus (Code:006) Class - IX (2021-2022) Term - 1 (IYAL 1 To 3)Document6 pagesTopic: Tamil Syllabus (Code:006) Class - IX (2021-2022) Term - 1 (IYAL 1 To 3)Rajnesh vanavarajanNo ratings yet

- Retail Scorecard NewDocument3,615 pagesRetail Scorecard NewND ProductsNo ratings yet

- SL No. Title and Author SubjectDocument12 pagesSL No. Title and Author SubjectAumFormlessNo ratings yet

- GTE February 2023 ResultDocument3 pagesGTE February 2023 ResultAnand RajaNo ratings yet

- Pure Tamil Baby Names For Girls Pure121 PDFDocument6 pagesPure Tamil Baby Names For Girls Pure121 PDFArun PrakashNo ratings yet

- Andhra Nayaka SatakamDocument47 pagesAndhra Nayaka SatakamnageshwarBI50% (2)

- Tamil Literature Sangam Age To Contemporary TimesDocument14 pagesTamil Literature Sangam Age To Contemporary Timesgokul viratNo ratings yet

- TamilCube Mooligai Marmam PDFDocument88 pagesTamilCube Mooligai Marmam PDFSenthil KumarNo ratings yet

- Purananuru: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument7 pagesPurananuru: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchVanitha CNo ratings yet

- TeluguDocument4 pagesTeluguVakamalla SubbareddyNo ratings yet

- KMSC LL LLL LLLLLLL I LFLFLLLL: J DGD S) D-Ugr-2Document10 pagesKMSC LL LLL LLLLLLL I LFLFLLLL: J DGD S) D-Ugr-2Kevin ArnoldNo ratings yet

- Nirvagam Iii, Iv Sem - Bba BHM Bca BSW Bba (T&T)Document92 pagesNirvagam Iii, Iv Sem - Bba BHM Bca BSW Bba (T&T)SanjuNo ratings yet

- English To Tamil DictionaryDocument4 pagesEnglish To Tamil DictionaryVidhya Raghavan100% (2)

- 1810 MaruthiDocument86 pages1810 Maruthideva nesanNo ratings yet

- Discussions About Vandanam and VanakkamDocument7 pagesDiscussions About Vandanam and VanakkamRavi Vararo100% (1)

- Byjus 05 02 2022Document1 pageByjus 05 02 2022Nandini N RNo ratings yet

- Andhra Nayaka SatakamDocument47 pagesAndhra Nayaka Satakamsirishadeepthi9840No ratings yet

- Pure Tamil Baby Names For Girls Pure PDFDocument6 pagesPure Tamil Baby Names For Girls Pure PDFArun PrakashNo ratings yet

- నా పెళ్లాలు 8Document8 pagesనా పెళ్లాలు 8Anonymous 9nRdJN8cW20% (5)

- Who Planted The Bombs in Chennai TrainDocument4 pagesWho Planted The Bombs in Chennai TrainThavam RatnaNo ratings yet

- Current Titles PriDocument69 pagesCurrent Titles Prirasia.kangNo ratings yet

- Power Point PresentationDocument15 pagesPower Point PresentationDivya PsNo ratings yet

- Oriens Product Video LinksDocument2 pagesOriens Product Video LinksImthiyas ARM100% (1)