Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Are Nutritional Guidelines Followed in The Pediatric...

Are Nutritional Guidelines Followed in The Pediatric...

Uploaded by

Beatriz RibeiroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Are Nutritional Guidelines Followed in The Pediatric...

Are Nutritional Guidelines Followed in The Pediatric...

Uploaded by

Beatriz RibeiroCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

published: 07 June 2021

doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.648867

Are Nutritional Guidelines Followed

in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit?

Mylène Jouancastay 1† , Camille Guillot 1† , François Machuron 2 , Alain Duhamel 2,3 ,

Jean-Benoit Baudelet 4 , Stéphane Leteurtre 1,3* and Morgan Recher 1,3

1

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, CHU Lille, Lille, France, 2 Department of Methodology, Biostatistics, and Management, CHU

Lille, Lille, France, 3 ULR 2694 - METRICS: Évaluation des Technologies de Santé et des Pratiques Médicales, Univ. Lille,

CHU Lille, Lille, France, 4 Congenital and Pediatric Cardiology Unit, CHU Lille, Lille, France

Background: French (2014) and American (2017) pediatric guidelines recommend

starting enteral nutrition (EN) early in pediatric intensive care. The aims of this study were

to compare the applicability of the guidelines in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU)

and to identify risk factors of non-application of the guidelines.

Edited by:

Demet Demirkol, Methods: This retrospective, single-center study was conducted in a medical–surgical

Istanbul University, Turkey PICU between 2014 and 2016. All patients from 1 month to 18 years old with a length of

Reviewed by: stay >48 h and an exclusive EN at least 1 day during the PICU stay were included. The

Vijay Srinivasan,

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia,

outcome variable was application of the 2014 and 2017 guidelines, defined by energy

United States intakes ≥90% of the recommended intake at least 1 day as defined by both guidelines.

Dick Tibboel,

The risk factors of non-application were studied comparing “optimal EN” vs. “non-optimal

Erasmus Medical Center, Netherlands

EN” groups for both guidelines.

*Correspondence:

Stéphane Leteurtre Results: In total, 416 children were included (mortality rate, 8%). Malnutrition occurred

stephane.leteurtre@chru-lille.fr

in 36% of cases. The mean energy intake was 34 ± 30.3 kcal kg−1 day−1 . The 2014

† These authors have contributed

and 2017 guidelines were applied in 183 (44%) and 296 (71%) patients, respectively

equally to this work and share first

authorship

(p < 0.05). Following the 2017 guidelines, enteral energy intakes were considered as

“satisfactory enteral intake” for 335 patients (81%). Hemodynamic failure was a risk factor

Specialty section: of the non-application of both guidelines.

This article was submitted to

Pediatric Critical Care, Conclusion: In our PICU, the received energy intake approached the level of intake

a section of the journal recommended by the American 2017 guidelines, which used the predictive Schofield

Frontiers in Pediatrics

equations and seem more useful and applicable than the higher recommendations of the

Received: 02 January 2021

Accepted: 19 April 2021

2014 guidelines. Multicenter studies to validate the pediatric guidelines seem necessary.

Published: 07 June 2021

Keywords: guidelines, malnutrition, enteral nutrition, energy intake, pediatric intensive care

Citation:

Jouancastay M, Guillot C,

Machuron F, Duhamel A, WHAT IS KNOWN

Baudelet J-B, Leteurtre S and

Recher M (2021) Are Nutritional • Malnutrition is frequent and a source of high morbi-mortality in the pediatric intensive care

Guidelines Followed in the Pediatric

unit (PICU).

Intensive Care Unit?

Front. Pediatr. 9:648867.

• Early adequate nutritional therapy is recommended.

doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.648867 • The application of recent pediatric nutritional guidelines has not been previously studied.

Frontiers in Pediatrics | www.frontiersin.org 1 June 2021 | Volume 9 | Article 648867

Jouancastay et al. Application of Nutritional Recommendations in PICU

WHAT IS NEW (considered as the acute phase in our study). The following EN

data were collected: time to initiate, volume (in milliliters per

We found that energy intake in the PICU approached the hour), energy (in calories per milliliter), interruption and feeding

intake recommended by the American 2017 guidelines, which intolerance (defined by vomiting or diarrhea as more than three

used the predictive Schofield equations and seem more useful liquid stools per day), and constipation (need for a laxative or

and applicable than the higher recommendations of the intrarectal treatment).

2014 guidelines. Nutritional status was determined using the z-score weighted

for age (13). Malnutrition included underweight (z-score <-

INTRODUCTION 2) and overweight (z-score >2). Malnourished and normo-

nourished patients were compared.

The prevalence of malnutrition at pediatric intensive care unit The energy requirements differed between the two guidelines

(PICU) admission is high (30–50%) and associated with a (Supplementary Table 1) (6, 7). Firstly, for each patient, both

longer period of mechanical ventilation and higher rates of guidelines were considered as “applied” if the patient received

mortality and nosocomial infections (1–4). In the PICU, oral more than 90% of the recommended energy intake, considering

nutrition was most often impossible. The European Society his age classification, at least 1 day during the hospitalization

for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (10). Secondly, energy intakes were considered as “satisfactory

(ESPGHAN) suggested the use of enteral nutrition (EN) support enteral intake” if they were ≥60% of the energy recommended

in critically ill children (5). However, the evaluation of the by the 2017 guidelines by the end of the PICU stay (maximum 1

nutritional status and optimal energy requirements for children week) (7).

in the PICU remains challenging. Early (first 24–48 h) EN is Risk factors of the non-application of the guidelines were

recommended, and optimal nutrition should be attained at studied using groups: “optimal EN vs. non-optimal EN” in the

the end of the first week of hospitalization (6, 7). If indirect 2014 and 2017 guidelines, respectively. EN was considered to be

calorimeter was not available, energy requirements can be optimal if the cumulative enteral energy intakes were ≥90% of the

estimated in the PICU using predicted equations or nutritional recommended energy intakes for each guideline for at least half

guidelines based on healthy children (8, 9). of the PICU stay, as used in the study of de Menezes at al. (10).

Several previous studies have shown that the levels of energy Quantitative variables were expressed as means (standard

intake in the PICU were less than those estimated by equations deviation) in the case of normal distribution or medians

and have identified risk factors of the non-application of (interquartile range, IQR) otherwise. Normality of distributions

nutritional guidelines (10–12). In the past few years, the French was assessed using histograms and the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine (2014) and the Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (percentage).

American Pediatric Nutrition Group (2017) published guidelines The association between the potential risk factors and the status

for nutrition support in the PICU (6, 7). However, no study has regarding the application of the guidelines (non-optimal EN

evaluated or compared the applicability of these two guidelines in vs. optimal EN) was assessed using Student’s t test or Mann–

the PICU. Whitney U test (according to the distribution) for continuous

The aims of the present study were to (1) compare the variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables. Variables

applicability of the 2014 and 2017 guidelines and (2) identify with p < 0.1 in bivariate analysis were considered candidates

risk factors of the non-application of both these guidelines in for the multivariable model according to their clinical relevance

the PICU. as risk factors of the non-application of guidelines in the

literature. These variables were included in a multivariable

METHODS logistic regression. For each continuous predictor, the log-

linearity assumption was assessed using the restricted cubic

This retrospective, single-center study was conducted in a spline functions. The collinearity between the predictors was also

medical–surgical PICU between October 2014 and December examined with a maximum level for the variance inflation factor

2016. All patients aged from 1 month to 18 years with a fixed at 2.5. Odds ratios for the risk of non-application of the

length of stay >48 h and an exclusive EN for at least 1 day guidelines were computed using 95% confidence intervals. Data

during the PICU stay were included. The exclusion criteria were analyzed using the SAS software package, release 9.4 (SAS

were: (a) patients with PICU length of stay <48 h; (b) no Institute, Cary, NC).

exclusive EN during the PICU stay; (c) oral nutrition exclusively; The study protocol was approved by the French Ethics and

(d) parenteral nutrition exclusively; (e) contraindication to EN Legal committees (CER-SFP 2017-068, DEC20-220).

(digestive surgery, occlusive syndrome, and bowel ischemia); and

(f) missing data. RESULTS

The data collected (ICCA, Philips R ) were: diagnosis at

admission, Pediatric Index of Mortality 2 (PIM2) score, Population Description

hemodynamic failure (defined by use of vasopressor agents), Of the 531 eligible patients, 416 were included (33, 47, 12, 11, six,

invasive or non-invasive ventilation, sedation (defined by use of and six patients were excluded according to criteria a, b, c, d, e,

hypnotic and morphinic agents), paralytic agents, length of PICU and f, respectively), with a median age of 14.5 months (IQR = 4–

and hospital stay, and mortality at 60 days (D60). The daily EN 60). The median time taken to obtain the target energy intakes

energy intake was calculated during the first 10 days in PICU was 3 days (IQR = 1–4). The median time to initiate EN was

Frontiers in Pediatrics | www.frontiersin.org 2 June 2021 | Volume 9 | Article 648867

Jouancastay et al. Application of Nutritional Recommendations in PICU

24 h (IQR = 7–48). Feeding intolerance occurred in 195 patients intakes were considered as “satisfactory enteral intake” (>60%

(47%) (Table 1). recommended energy intakes at the end of the first week in PICU)

At PICU admission, 151 patients (36%) were malnourished: for 335 patients (81%).

127 underweight (30%) and 24 overweight (6%). Mortality

rate at D60 was statistically increased in malnourished patients

compared to normo-nourished patients (16 vs. 4%, p < 0.001), Risk Factors of Non-application of

without differences in the median length of stay (5 vs. 6 days), Guidelines

PIM2 score (2.2% vs. 2.3%), and time to initiate EN (22 vs. 24 h). Enteral nutrition was optimal (defined as cumulative enteral

energy intakes ≥90% of the recommended energy intakes for

Comparison of Guidelines each guideline for at least half of the PICU stay) for 88 patients

The mean enteral energy intakes were 34 ± 30.3 kcal kg−1 day−1 (21%) for the 2014 guidelines and 161 patients (39%) for the

and represented 45% of the recommended energy intakes for the 2017 guidelines (p = 0.003). For each guideline, there was no

2014 guidelines and 66% for the 2017 guidelines according to difference between optimal EN and non-optimal EN for 2014 and

each age classification (p = 0.03). The 2014 and 2017 guidelines 2017, respectively, for mortality at D60 (p = 0.07 and p = 0.12),

were applied (>90% of the recommended energy intake at least or length of stay (p = 0.16 and p = 0.81). For both guidelines,

1 day) in 183 (44%) and 296 (71%) patients, respectively (p < time to initiate EN was significantly longer in the non-optimal

0.05). Following the 2017 American guidelines, enteral energy EN compared to the optimal EN group (24 vs. 10 h and 29 vs.

11 h, respectively; both p < 0.001).

In the multivariate analysis, hemodynamic failure was a risk

factor of non-application of the guidelines for 2014 [odds ratio

TABLE 1 | Demographic and clinical characteristics of the population.

(OR) = 5.3, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.1–28.4] and 2017

Variable N = 416 (OR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.1–7.5). Previous chronic cardiac disease

was a protective factor of non-application of the guidelines for

Male patients, n (%) 226 (54.1) 2014 (OR = 0.5, 95% CI = 0.3–0.9) and 2017 (OR = 0.5, 95% CI

Age, median month (IQR) 14.5 (4–60) = 0.3–0.9). For the 2017 guidelines, chronic digestive disease was

Weight, median kg (IQR) 9.1 (5.4–18) a protective factor (OR = 0.6, 95% CI = 0.4–0.9) (Table 2).

PIM 2, median% (IQR) 2.2(1.1–6.8)

Chronic disease, n (%)

Chronic cardiac disease 92 (22) DISCUSSION

Chronic digestive disease 124 (29.7)

Malnutrition, n (%) 151 (36.2) This study is the first examining the applicability and risk

Z-score < −2 127 (30.5) factors of the non-application of two national guidelines in

Z-score > 2 24 (5.7) the PICU. In our 416 children (mortality rate, 8%), 36% of

Diagnosis at PICU admission patients were malnourished at PICU admission. The mean

Respiratory 202 (48.5) enteral energy intakes (34 kcal kg−1 day−1 ) represented 45 and

Neurologic 61 (14.6) 66% of, respectively, the 2014 and 2017 guidelines’ recommended

Surgical 59 (14.1) energy intakes. The 2014 and 2017 guidelines were, respectively,

Digestive disease 29 (6.9) applied to 44 and 71% of patients. Following the 2017 American

Cardiac disease 17 (4.1) guidelines, enteral energy intakes were considered as “satisfactory

Sepsis 16 (3.8) enteral intake” for 81% of patients. Hemodynamic failure was

Burn 13 (3)

an independent risk factor of the non-application of both

Trauma 12 (3)

guidelines, whereas cardiac and digestive antecedents were

Other 7 (1.6)

protective factors.

Mechanical ventilation, n (%) 201 (48)

Many studies have previously shown that the application

Vasopressors, n (%) 53 (12)

of nutritional recommendations was difficult in the PICU,

regardless of the previous guidelines used (10–12, 14). In the

Paralytic agents, n (%) 27 (6.4)

American prospective study by de Menezes et al., in the PICU (n

Morphine agents, maximum rate (mg kg−1 day−1 ), mean (range) 2.4 (6.5)

= 207 children), only 20.8% of the population had energy intakes

Midazolam, maximum rate (mcg kg−1 min−1 ), mean (range) 1.05 (2.55)

>90% of the target [estimated with World Health Organization

Procedures, n (%) 233 (55)

(WHO) equations] (10). Moreover, Kyle et al. observed (n =

Time to initiate EN (h), median (IQR) 24 (7–48)

240 children) that the energy intakes were >90% of the energy

Enteral nutrition interruptions, mean (range) 1.1 (1.5)

intakes recommended by the Schofield equations for 40% of all

Gastrointestinal intolerance, n (%) 195 (47)

patient-days in the PICU (11).

Length of PICU stay (days), median (IQR) 5 (3–10)

ESPHGAN guidelines provided a clinical guide of EN in

Mortality at day 60, n (%) 34 (8.1)

pediatric patients (5), but basal metabolism was probably altered

EN, enteral nutrition; IQR, interquartile; PIM 2, Pediatric Index of Mortality 2; PICU, in critically ill patients and estimation of the optimal energy

pediatric intensive care unit. requirement was not provided (4, 15). The energy requirements

Frontiers in Pediatrics | www.frontiersin.org 3 June 2021 | Volume 9 | Article 648867

Frontiers in Pediatrics | www.frontiersin.org

Jouancastay et al.

TABLE 2 | Univariate and multivariate analyses for optimal and non-optimal application of the 2014 and 2017 EN guidelines.

2014 French guidelines (n = 416) 2017 American guidelines (n = 416)

b

Univariate Multivariate analysis Univariate Multivariate analysisb

analysisa analysisa

Optimal EN, Non-optimal EN, p OR (95% CI) p Optimal EN, Non-optimal EN, p OR (95% CI) p

n = 88 (21%) n = 328 (79%) n = 161 (39%) n = 255 (61%)

PIM 2, median (IQR) 1.6 (0.8–4.5) 2.6 (1–6.7) 0.21 1.6 (0.8–4) 3.4 (1–7.4) 0.78

Chronic cardiac disease, n (%) 32 (36) 60 (18) <0.001 0.5 (0.3–0.9) 0.014 51 (32) 41 (16) <0.001 0.5 (0.3–0.9) 0.019

Chronic digestive disease, n (%) 40 (45) 84 (25) <0.001 0.6 (0.4–1.0) 0.075 67 (42) 57 (22) <0.001 0.6 (0.4–0.9) 0.032

Malnutrition, n (%) 39 (44) 112 (34) 0.089 0.8 (0.5–1.3) 0.39 72 (45) 79 (31) 0.006 0.7 (0.4–1.0) 0.065

EN interruption, median (IQR) 0 (0–1) 1 (0–2) 0.12 0 (0–1) 1 (0–2) 0.004 1.1 (0.9–1.3) 0.41

Feeding intolerance, n (%) 44 (50) 151 (46) 0.48 74 (46) 120 (47) 0.83

Invasive ventilation, n (%) 32 (36) 169 (51) 0.014 1.2 (0.7–2.0) 0.53 62 (38) 138 (54) 0.002 1.1 (0.7–1.8) 0.61

Non-invasive ventilation, n (%) 45 (51) 171 (52) 0.91 82 (51) 134 (53) 0.74

Hemodynamic failure, n (%) 2 (2) 51 (15) 0.004 5.3 (1.1–28.4) 0.049 7 (4) 46 (18) <0.001 2.7 (1.1–7.5) 0.047

Paralytic agents, n (%) 2 (2) 25 (8) 0.090 2.7 (0.6–12.9) 0.22 4 (2.5) 23 (9) 0.013 2.9 (0.9–9.1) 0.077

Morphinic agents, maximum rate (mg kg−1 1.2 (0.6–2) 1.5 (1–6) 0.030 1 (0.9–1.1) 0.92 1.2 (0.7–2) 1.5 (1–7) 0.002 1.0 (0.9–1.1) 0.76

day−1 ), median (IQR)

Midazolam, maximum rate (mcg kg−1 min−1 ), 1.7 (0.6–3) 1.5 (0.5–3) 0.65 1.5 (0.5–3) 1.5 (0.7–3) 0.67

median (IQR)

4

Outcomes

Mortality at day 60, n (%) 1 (4) 31 (10) 0.071 9 (6) 25 (10) 0.12

Length of stay in PICU (days), median (IQR) 6 (3–11) 5 (3–10) 0.16 5 (3–10) 5 (3–10) 0.81

Energy intake received (kcal kg −1 day−1 ), 59.7 25.4 (12.7–38.4) <0.001 52.4 18.4 (10.0–28.1) <0.001

median (IQR) (41.8–73.5) (40.0–66.2)

Time to initiate EN (h), median (IQR) 10 (3–26) 24 (9–53) <0.001 11 (4–27) 29 (12–58) <0.001

EN, enteral nutrition; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; PIM 2, Pediatric Index of Mortality 2.

a Mann–Whitney test for quantitative variables and chi-square for categorical variables.

b Multivariate logistic regression for the risk of non-optimal application of guidelines.

Application of Nutritional Recommendations in PICU

June 2021 | Volume 9 | Article 648867

Jouancastay et al. Application of Nutritional Recommendations in PICU

differed between the two guidelines (Supplementary Table 1). guidelines because no EN protocol was used in our unit at that

The 2017 recommended energy intakes were lower than those time. Thirdly, we did not compare the energy intake with the

of the 2014 guidelines (6, 7). The 2014 guidelines were based on measured energy requirements in our study (indirect calorimetry

the Apports Nutritionnels Conseillés reference, which is used in or carbon dioxide production) (18) because these methods were

France to assess the nutritional status of the healthy population not routinely used.

(8). The 2017 guidelines recommended energy intakes using In our PICU, the received energy intake approached the level

the Schofield equations and were closer than the energy intakes of intake recommended by the American 2017 guidelines, which

measured by indirect calorimetry in the PICU (9, 16). In used the predictive Schofield equations. They therefore seem

other words, the 2017 guidelines seem to be more accurate for more useful and applicable than the 2014 guidelines. Multicenter

establishing the nutritional targets for patients in the PICU. studies to validate the pediatric guidelines seem necessary.

Several authors previously recommended a decrease in the target

energy intakes, described as “autophagy,” in the acute phase in DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

critically ill adults and children (14, 15, 17). Then, the 2017

guidelines recommended to target energy intakes equal to or The original contributions presented in the study are included

>60% as estimated by predictive Schofield equations at the end in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be

of the first week in the PICU (7), closer than the recent adult directed to the corresponding author/s.

recommendations (70% of the energy expenditure in the acute

phase) (18). According to this threshold, “satisfactory enteral ETHICS STATEMENT

intake” occurred in 81% of the patients in our study.

In our study, hemodynamic failure was a risk factor of The studies involving human participants were reviewed and

the non-application of both the 2014 and 2017 guidelines, as approved by French Ethics and Legal committees (CER-SFP

described in pediatric (WHO guidelines 1985, n = 84) (12) 2017-068, DEC20-220). Written informed consent from the

and adult (n = 2,410) patients (19). According to these studies, participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to

the definition of hemodynamic failure varies: vasopressor agents participate in this study in accordance with the national

used, scoring system, or the lactate level increased (12, 20). legislation and the institutional requirements.

Moreover, the 2017 adult nutritional guidelines recommend

delaying EN when an uncontrolled shock with an increased AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

lactate rate exists (21). In 2020, ESPNIC (European Society of

Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care) suggested to start EN MJ and CG conceptualized the study, conducted the initial

early in children who were stable on vasopressor agents (22). analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed, and revised the

In our study, chronic cardiac and digestive diseases manuscript. FM performed the statistical analysis and revised

were protective factors of the non-application of nutritional the manuscript. J-BB analyzed and revised the manuscript. SL

guidelines. As shown by de Menezes et al., malnutrition was and MR conceptualized the study, reviewed, and revised the

more important in cases of chronic cardiac or digestive disease, manuscript. AD performed statistical analysis and revised the

and malnutrition was a protective factor of the non-application manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript

of the 2017 guidelines (10). as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of

Our study had several limitations. Firstly, it was a single-center the work.

study. The population was heterogeneous (severity of illness,

length of stay in the PICU, etc.), but comparable to those in SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

previous pediatric studies (10, 11). Secondly, the applications of

the guidelines were compared in a retrospective sample using a The Supplementary Material for this article can be found

period of study at the beginning of the 2017 guidelines. However, online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.

the energy intake was probably somewhat independent of the 2021.648867/full#supplementary-material

REFERENCES 4. Wilson B, Typpo K. Nutrition: a primary therapy in pediatric acute

respiratory distress syndrome. Front Pediatr. (2016). 4:108. doi: 10.3389/fped.

1. De Souza Menezes F, Leite HP, Koch Nogueira PC. Malnutrition as an 2016.00108

Independent Predictor of clinical outcome in critically ill children. Nutr 5. Braegger C, Decsi T, Dias JA, Hartman C, Kolacek S, Koletzko B, et al.

Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif. (2012) 28:267–70. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.05.015 Practical approach to paediatric enteral nutrition: a comment by the

2. Grippa RB, Silva PS, Barbosa E, Bresolin NL, Mehta NM, Moreno YMF. ESPGHAN committee on nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2010).

Nutritional status as a predictor of duration of mechanical ventilation 51:110–22. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d336d2

in critically ill children. Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif. (2017) 6. Lefrant J-Y, Hurel D, Cano NJ, Ichai C, Preiser J-C, Tamion F, et al. [Guidelines

33:91–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.05.002 for nutrition support in critically ill patient]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. (2014)

3. Ventura JC, Hauschild DB, Barbosa E, Bresolin NL, Kawai K, Mehta NM, 33:202–18. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2014.01.008

et al. Undernutrition at PICU admission is predictor of 60-day mortality 7. Mehta NM, Skillman HE, Irving SY, Coss-Bu JA, Vermilyea S, Farrington

and PICU length of stay in critically ill children. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2020) EA, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support

120:219–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.06.250 therapy in the pediatric critically ill patient: society of critical care medicine

Frontiers in Pediatrics | www.frontiersin.org 5 June 2021 | Volume 9 | Article 648867

Jouancastay et al. Application of Nutritional Recommendations in PICU

and american society for parenteral and enteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter 17. Reintam Blaser A, Berger MM. Early or late feeding after ICU admission?

Enteral Nutr. (2017) 41:706–42. doi: 10.1177/0148607117711387 Nutrients. (2017) 9:1278. doi: 10.3390/nu9121278

8. Martin A. The ’apports nutritionnels conseillés (ANC)’ for the French 18. Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Alhazzani W, Calder PC, Casaer

population. Reprod Nutr Dev. (2001) 41:119–28. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2001100 MP, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive

9. Vazquez Martinez JL, Martinez-Romillo PD, Diez Sebastian J, Ruza care unit. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. (2019) 38:48–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.

Tarrio F. Predicted versus measured energy expenditure by continuous, 2018.08.037

online indirect calorimetry in ventilated, critically ill children 19. Reignier J, Boisramé-Helms J, Brisard L, Lascarrou J-B, Ait Hssain A,

during the early postinjury period. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2004) Anguel N, et al. Enteral versus parenteral early nutrition in ventilated

5:19–27. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000102224.98095.0A adults with shock: a randomised, controlled, multicentre, open-label,

10. De Menezes FS, Leite HP, Nogueira PCK. What are the factors that influence parallel-group study (NUTRIREA-2). Lancet Lond Engl. (2018) 391:133–

the attainment of satisfactory energy intake in pediatric intensive care unit 43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32146-3

patients receiving enteral or parenteral nutrition? Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty 20. Bakker J. Lactate levels and hemodynamic coherence in acute

Calif. (2013) 29:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.04.003 circulatory failure. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. (2016)

11. Kyle UG, Jaimon N, Coss-Bu JA. Nutrition support in critically 30:523–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2016.11.001

ill children: underdelivery of energy and protein compared with 21. Reintam Blaser A, Starkopf J, Alhazzani W, Berger MM, Casaer MP,

current recommendations. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2012) 112:1987– Deane AM, et al. Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients:

92. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.07.038 ESICM clinical practice guidelines. Intensive Care Med. (2017) 43:380–

12. De Neef M, Geukers VGM, Dral A, Lindeboom R, Sauerwein HP, Bos AP. 98. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4665-0

Nutritional goals, prescription and delivery in a pediatric intensive care unit. 22. Tume LN, Valla FV, Joosten K, Jotterand Chaparro C, Latten L, Marino LV,

Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. (2008) 27:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.10.013 et al. Nutritional support for children during critical illness: European Society

13. Mehta NM, Corkins MR, Lyman B, Malone A, Goday PS, Carney of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) metabolism, endocrine

LN, et al. Defining pediatric malnutrition: a paradigm shift toward and nutrition section position statement and clinical recommendations.

etiology-related definitions. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. (2013) 37:460– Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46:411–25. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05922-5

81. doi: 10.1177/0148607113479972

14. Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Cahill N, Wang M, Day A, Duggan CP, et al. Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the

Nutritional practices and their relationship to clinical outcomes in critically absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a

ill children–an international multicenter cohort study∗ . Crit Care Med. (2012) potential conflict of interest.

40:2204–11. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e18a8

15. Joosten KFM, Kerklaan D, Verbruggen SCAT. Nutritional support and the Copyright © 2021 Jouancastay, Guillot, Machuron, Duhamel, Baudelet, Leteurtre

role of the stress response in critically ill children. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab and Recher. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Care. (2016) 19:226–33. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000268 Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in

16. Meyer R, Kulinskaya E, Briassoulis G, Taylor RM, Cooper M, Pathan N, other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s)

et al. The challenge of developing a new predictive formula to estimate are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance

energy requirements in ventilated critically ill children. Nutr Clin Pract. (2012) with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted

27:669–76. doi: 10.1177/0884533612448479 which does not comply with these terms.

Frontiers in Pediatrics | www.frontiersin.org 6 June 2021 | Volume 9 | Article 648867

You might also like

- Dubai World Ehs - 2007 Regulations & StandardsDocument106 pagesDubai World Ehs - 2007 Regulations & StandardsSAYED100% (10)

- ASPEN Pediatría 2017Document37 pagesASPEN Pediatría 2017Consultorio Pediatria ShaioNo ratings yet

- Guia Esphan Espen Espr Cspen Nutricion ParenteralDocument127 pagesGuia Esphan Espen Espr Cspen Nutricion ParenteralLuz Dary Paez VArgasNo ratings yet

- PYMS TamizajeDocument6 pagesPYMS TamizajeKevinGallagherNo ratings yet

- J Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2021 - Compher - Guidelines For The Provision of Nutrition Support Therapy in The AdultDocument30 pagesJ Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2021 - Compher - Guidelines For The Provision of Nutrition Support Therapy in The AdultPabloNo ratings yet

- Clinical Impact of Prescribed Doses of Nutrients For Patients Exclusively Receiving Parenteral Nutrition in Japanese HospitalsDocument9 pagesClinical Impact of Prescribed Doses of Nutrients For Patients Exclusively Receiving Parenteral Nutrition in Japanese Hospitalsmarco marcoNo ratings yet

- J Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2017 - Mehta - Guidelines For The Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in TheDocument37 pagesJ Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2017 - Mehta - Guidelines For The Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in TheZ. Raquel García OsornoNo ratings yet

- A Stepwise Enteral Nutrition Algorithm For Critically Ill ChildrenDocument13 pagesA Stepwise Enteral Nutrition Algorithm For Critically Ill ChildrenHerwina BrahmantyaNo ratings yet

- Assesing The Appropriatenes of Parenteral Nutrition Use in Hospitalized Patients EspenDocument8 pagesAssesing The Appropriatenes of Parenteral Nutrition Use in Hospitalized Patients EspenDarío ParraNo ratings yet

- J Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2021 - Compher - Guidelines For The Provision of Nutrition Support Therapy in The AdultDocument30 pagesJ Parenter Enteral Nutr - 2021 - Compher - Guidelines For The Provision of Nutrition Support Therapy in The Adultsulemi castañonNo ratings yet

- A Stepwise Enteral Nutrition Algorithm For Critically (Susan Dan Nilesh Mehta)Document7 pagesA Stepwise Enteral Nutrition Algorithm For Critically (Susan Dan Nilesh Mehta)NyomanGinaHennyKristiantiNo ratings yet

- Ems 113478Document16 pagesEms 113478AfniNo ratings yet

- 10 1002@jpen 1723Document16 pages10 1002@jpen 1723Helena OliveiraNo ratings yet

- LitiasisDocument7 pagesLitiasisSandy SalazarNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Therapy in Critically Ill Patients A Review of Current Evidence For CliniciansDocument7 pagesNutrition Therapy in Critically Ill Patients A Review of Current Evidence For CliniciansangiolikkiaNo ratings yet

- ESPEN Guidelines On Nutritional Support For Polymorbid Internal Med PatDocument18 pagesESPEN Guidelines On Nutritional Support For Polymorbid Internal Med PatAmany SalamaNo ratings yet

- Nut in Clin Prac - 2023 - Mohamed Elfadil - Peptide Based Formula Clinical Applications and BenefitsDocument11 pagesNut in Clin Prac - 2023 - Mohamed Elfadil - Peptide Based Formula Clinical Applications and BenefitshizburNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Practices With A Focus On Parenteral NutDocument10 pagesNutrition Practices With A Focus On Parenteral NutJose VasquezNo ratings yet

- Post-ICU Nutrition The Neglected Side of Metabolic SupportDocument3 pagesPost-ICU Nutrition The Neglected Side of Metabolic SupportHubert PastasNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0261561420301941 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0261561420301941 MainNatalia BeltranNo ratings yet

- Clinical Nutrition: ESPEN GuidelineDocument18 pagesClinical Nutrition: ESPEN GuidelineMariana RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Nutritional ManagmentDocument19 pagesNutritional ManagmentgianellaNo ratings yet

- Parenteral Nutrition Objectives For Very Low Birth Weight Infants: Results of A National SurveyDocument9 pagesParenteral Nutrition Objectives For Very Low Birth Weight Infants: Results of A National SurveyjlionelmoNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Nutrition in Extremely Preterm Infants Undergoing Surgery For Patent Ductus ArteriosusDocument12 pagesPerioperative Nutrition in Extremely Preterm Infants Undergoing Surgery For Patent Ductus ArteriosusOctavianus KevinNo ratings yet

- Characterizing International Approaches To Weaning Children From Tube Feeding - A Scoping ReviewDocument12 pagesCharacterizing International Approaches To Weaning Children From Tube Feeding - A Scoping Revieweo.mobilestoreNo ratings yet

- Simple Nutrition Screening Tool For Pediatric InpatientsDocument7 pagesSimple Nutrition Screening Tool For Pediatric InpatientsYulmira YulmiraNo ratings yet

- Wong 2016Document7 pagesWong 2016Andreas Dhymas DmkNo ratings yet

- 1.2.21 Aspects of Protected Mealtimes Are Associated With Improved Mealtime Energy and Protein Intakes in Hospitalized Adult Patients On Medical and Surgical Wards Over 2 YearsDocument5 pages1.2.21 Aspects of Protected Mealtimes Are Associated With Improved Mealtime Energy and Protein Intakes in Hospitalized Adult Patients On Medical and Surgical Wards Over 2 Yearsciksas19No ratings yet

- Nutrients: Complications Associated With Enteral Nutrition: CAFANE StudyDocument12 pagesNutrients: Complications Associated With Enteral Nutrition: CAFANE StudySiti WarohmahNo ratings yet

- Mekhancha Dahel2014Document1 pageMekhancha Dahel2014richard menzNo ratings yet

- 2022 - Enteral Feeding, IF 2.2Document8 pages2022 - Enteral Feeding, IF 2.2Manal Haj HamadNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Practice Surveys On Parenteral Nutrition For Preterm InfantsDocument5 pagesA Systematic Review of Practice Surveys On Parenteral Nutrition For Preterm InfantsKhor Chin PooNo ratings yet

- Kad 2Document50 pagesKad 2nellieauthorNo ratings yet

- (2019) Parenteral Nutrition in The ICU Lessons Learned Over The Past Few YearsDocument7 pages(2019) Parenteral Nutrition in The ICU Lessons Learned Over The Past Few YearsAnna Maria Ariesta PutriNo ratings yet

- ASPEN NutritionDocument18 pagesASPEN Nutritionsilvio da costa guerreiroNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2405457722000432 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S2405457722000432 MainjvracuyaNo ratings yet

- Optimal Timing For Introducing Enteral Nutrition in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDocument8 pagesOptimal Timing For Introducing Enteral Nutrition in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitAnonymous 1EQutBNo ratings yet

- Intensive & Critical Care Nursing: Research ArticleDocument6 pagesIntensive & Critical Care Nursing: Research ArticleJaemin cuteNo ratings yet

- Volume-Based Protocol Improves Delivery of Enteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Trauma Patients 2020Document6 pagesVolume-Based Protocol Improves Delivery of Enteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Trauma Patients 2020Marcelo Andrés Ortega ArjonaNo ratings yet

- ESPEN Practical Guideline Clinical Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseDocument22 pagesESPEN Practical Guideline Clinical Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseChico MotaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AningDocument7 pagesJurnal AningSitaNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Management of The Critically Ill.29Document16 pagesNutritional Management of The Critically Ill.29Ririn Muthia ZukhraNo ratings yet

- Artigo - Compliance Oral Nutrition Supplement - ReviewDocument20 pagesArtigo - Compliance Oral Nutrition Supplement - ReviewFrancielle A.RNo ratings yet

- 2 ESPEN-ESPGHAN-ECFS Guidelines On Nutrition Care For Infants Children and Adults With Cystic FibrosisDocument21 pages2 ESPEN-ESPGHAN-ECFS Guidelines On Nutrition Care For Infants Children and Adults With Cystic FibrosisAmany SalamaNo ratings yet

- Association of Infant Feeding Practices and Food NDocument11 pagesAssociation of Infant Feeding Practices and Food NBULAN IFTINAZHIFANo ratings yet

- Improving Growth of Infants With Congenital Heart Disease Using A Consensus-Based Nutritional PathwayDocument8 pagesImproving Growth of Infants With Congenital Heart Disease Using A Consensus-Based Nutritional Pathwaybela siskaNo ratings yet

- 23 - Bapat2019Document10 pages23 - Bapat2019Rosa PerezNo ratings yet

- Nutricion ParenteralDocument18 pagesNutricion ParenteralTadeo PradoNo ratings yet

- Berger-Monitoreo Nutricional en UCI-2018Document10 pagesBerger-Monitoreo Nutricional en UCI-2018Brayan AuntaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Nutrition ESPENDocument15 pagesClinical Nutrition ESPENBBD BBDNo ratings yet

- Guidelines ASPENDocument138 pagesGuidelines ASPENJaqueline Odair100% (1)

- Nutrition of The Critically Ill Patient and Effects of Implementing A Nutritional Support Algorithm in ICUDocument10 pagesNutrition of The Critically Ill Patient and Effects of Implementing A Nutritional Support Algorithm in ICUFildzah Aulia UlhaqNo ratings yet

- Parenter Enteral Nutr 2009 Mehta 260 76Document17 pagesParenter Enteral Nutr 2009 Mehta 260 76Bogdan CarabasNo ratings yet

- YOR-PICU-001 Updated en Guidelines Dec 2013Document16 pagesYOR-PICU-001 Updated en Guidelines Dec 2013Meirinda HidayantiNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of Early Oral Nutrition in Mild Acute PancreatitisDocument6 pagesThe Benefits of Early Oral Nutrition in Mild Acute PancreatitisrayiNo ratings yet

- Insulin Treatment in Children and Adolescents With DiabetesDocument20 pagesInsulin Treatment in Children and Adolescents With Diabetesmreda983No ratings yet

- PYMS Is A Reliable Malnutrition Screening ToolsDocument8 pagesPYMS Is A Reliable Malnutrition Screening ToolsRika LedyNo ratings yet

- PIIS2405457722004831Document4 pagesPIIS2405457722004831Karla Rosángel CordónNo ratings yet

- Total Nutritional Therapy: A Nutrition Education Program For PhysiciansDocument7 pagesTotal Nutritional Therapy: A Nutrition Education Program For PhysiciansTia WasrilNo ratings yet

- Negative Impact of Hypocaloric Feeding and Energy Balance On Clinical Outcome in ICU PatientsDocument8 pagesNegative Impact of Hypocaloric Feeding and Energy Balance On Clinical Outcome in ICU PatientsDaniela HernandezNo ratings yet

- The Lovely BonesDocument2 pagesThe Lovely BonesJohn ConstantineNo ratings yet

- Laptop Price List-Afresh笔记本Document6 pagesLaptop Price List-Afresh笔记本Miriam BarahonaNo ratings yet

- MBA Syllabus 2021 NewDocument245 pagesMBA Syllabus 2021 Newarchana97anilNo ratings yet

- SensION1 ManualDocument40 pagesSensION1 ManualMaria Victoria GuarinNo ratings yet

- Digital WatermarkingDocument29 pagesDigital WatermarkingAngelNo ratings yet

- Android - Architecture: Linux KernelDocument3 pagesAndroid - Architecture: Linux KernelMahnoor AslamNo ratings yet

- Preventionof HypothermiaDocument2 pagesPreventionof HypothermiarisnayektiNo ratings yet

- The Marketing Challenge of Low Resource CustomersDocument7 pagesThe Marketing Challenge of Low Resource Customersvivek mithraNo ratings yet

- Ieee C37.20.3-2013Document70 pagesIeee C37.20.3-2013damaso taracena100% (2)

- Spss SyllabusDocument2 pagesSpss SyllabusBhagwati ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Stinger 3470: Boom Truck CraneDocument4 pagesStinger 3470: Boom Truck CraneKatherinne ChicaNo ratings yet

- A Semi Detailed Lesson Plan in Physical ScienceDocument2 pagesA Semi Detailed Lesson Plan in Physical ScienceHannah Jane AllesaNo ratings yet

- Afd 021019 1 1B 50Document100 pagesAfd 021019 1 1B 50Sab-Win DamadNo ratings yet

- Shell Turbo Oil T46: Performance, Features & Benefits Main ApplicationsDocument4 pagesShell Turbo Oil T46: Performance, Features & Benefits Main Applicationshaider100% (1)

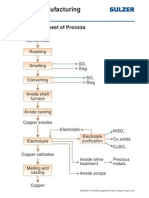

- Copper Manufacturing Process: General Flowsheet of ProcessDocument28 pagesCopper Manufacturing Process: General Flowsheet of ProcessflaviosazevedoNo ratings yet

- Donald Redford - Akhenaten - New Theories and Old FactsDocument27 pagesDonald Redford - Akhenaten - New Theories and Old FactsDjatmiko TanuwidjojoNo ratings yet

- Big Data Analytics (2017 Regulation) : Unit - 2 Clustering and ClassificationDocument7 pagesBig Data Analytics (2017 Regulation) : Unit - 2 Clustering and ClassificationcskinitNo ratings yet

- Ghost Usb Honeypot MasterDocument15 pagesGhost Usb Honeypot MasterVinamra MittalNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Rules and SafetyDocument9 pagesLaboratory Rules and SafetyMehul KhimaniNo ratings yet

- Final - ERP Implementation in Indian ContextDocument9 pagesFinal - ERP Implementation in Indian Contextsurajmukti0% (1)

- 25 191 1 PB PDFDocument11 pages25 191 1 PB PDFRaihatil UmmiNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Psak 73 Implementation On Leases in Indonesia Telecommunication CompaniesDocument17 pagesThe Impact of Psak 73 Implementation On Leases in Indonesia Telecommunication CompaniesAnin YusufNo ratings yet

- 02-Mushtaq Ali LigariDocument32 pages02-Mushtaq Ali LigariAbdul Arham BalochNo ratings yet

- 2020 ECO Topic 1 International Economic Integration Notes HannahDocument23 pages2020 ECO Topic 1 International Economic Integration Notes HannahJimmyNo ratings yet

- Digital BankingDocument3 pagesDigital BankingDPC Gym100% (1)

- Phil Hine en PermutationsDocument41 pagesPhil Hine en Permutationsgunter unserNo ratings yet

- Servest Training CatalogueDocument62 pagesServest Training Catalogueayandamakabongwe06No ratings yet

- DVT Case StudyDocument3 pagesDVT Case StudyCrystal B Costa78No ratings yet

- MTH151 Syllabus S12Document6 pagesMTH151 Syllabus S12schreckk118No ratings yet