Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fisher ImpactsVoiceChange 2014

Fisher ImpactsVoiceChange 2014

Uploaded by

stephenieleevos1Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fisher ImpactsVoiceChange 2014

Fisher ImpactsVoiceChange 2014

Uploaded by

stephenieleevos1Copyright:

Available Formats

The Impacts of the Voice Change, Grade Level, and Experience on the Singing Self-

Efficacy of Emerging Adolescent Males

Author(s): Ryan A. Fisher

Source: Journal of Research in Music Education , October 2014, Vol. 62, No. 3 (October

2014), pp. 277-290

Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of MENC: The National Association for

Music Education

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43900256

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sage Publications, Inc. and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Journal of Research in Music Education

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ļļJlEJ National Association

for Music Education

Article

Journal of Research in Music Education

2014, Vol. 62(3) 277-290

The Impacts of the Voice © National Association for

Music Education 2014

Change, Grade Level, and Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Experience on the Singing DOI: 10.1177/0022429414544748

jrme.sagepub.com

Self-Efficacy of Emerging USAGE

Adolescent Males

Ryan A. Fisher1

Abstract

The purposes of the study are to describe characteristics of the voice chan

sixth-, seventh-, and eighth-grade choir students using Cooksey's voice-ch

classification system and to determine if the singing self-efficacy of adolescent

is affected by the voice change, grade level, and experience. Participants (N = 8

consisted of volunteer sixth-grade, seventh-grade, and eighth-grade males enroll

a public school choral program. Participants completed the Singing Self-Efficacy

for Emerging Adolescent Males (SSES). After completing the SSES, participants

individually audio-recorded performing simple vocal exercises to attain each bo

vocal range. Results revealed that 45% of sixth-grade participants, 48. 1 5% of sev

grade participants, and 87.88% of eighth-grade participants were classified as chan

voices. Results of a three-way between-subjects ANOVA revealed no main effec

voice-change stage or grade level. A main effect was found for experience, fav

participants with 3 or more years of experience in choir. No statistically signi

interactions were found.

Keywords

voice change, self-efficacy, male

'University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA

Corresponding Author:

Ryan A. Fisher, Rudi E. Scheidt School of Music, University of Memphis, 1 29 Music Building, Memphis, TN

38152-3160, USA.

Email: ryan.fìsher@memphis.edu

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

278 Journal of Research in Music Education 62(3)

Despite extensive research on the topic of the male voice change, mid

high school choir directors continue to struggle with the various challe

change presents. Much of our current knowledge of the physical charact

male voice change has derived from John Cooksey. Influenced by his

McKenzie (1956), Cooper (Cooper & Kuertsteiner, 1970), and Swan

Cooksey engaged in several longitudinal studies, which resulted in a f

sification system for the changing male voice: Midvoice I, Midvoice II

New Voice, and Emerging Adult Voice (Cooksey, 1999; Cooksey &

Research has validated Cooksey's male voice-change classification syste

Bless, 1984; Cooksey, 1984, 1985; Cooksey & Welch, 1998; Fisher,

1984; Killian, 1999).

A preponderance of research on the adolescent male voice has focus

of onset of the voice change (Barresi & Bless, 1984; Cooksey, 1984;

Friesen, 1972; Hollien, Green, & Massey, 1994; Karr, 1988; Sturdy

recent research on the male voice mutation has indicated a trend toward

of onset (Fisher, 2010; Killian, 1999; Killian & Wayman, 2010; Rutk

Killian (1999) found that 50% of fifth-grade and 81% of sixth-gra

already in one of Cooksey 's voice change stages. Fisher (2010) measure

fifth-, and sixth-grade males who were either in general music, band,

not enrolled in any music elective and found the age of onset for tha

1 1 .20 years of age, with 46% of fourth-grade, 62% of fifth-grade, and

grade males classified as "changing" or "changed" voices. Most recently

Wayman (2010) measured the voices of boys enrolled in either cho

found that 81.25% of sixth-grade males, 85.1 1% of seventh-grade male

of eighth-grade males had begun their voice change.

Authors in other areas of research concerning the voice change hav

teacher knowledge of and accommodations for the changing voice

Chapman, 1989; Kennedy, 2004; Killian, 2003; Usher, 2005), adolesce

agility (Hook, 2005), and intensity control (Harris, 1996). As Killian

much of the body of research concerning the adolescent male has focus

physiological characteristics of the voice change with little knowledge

the psychological or psychosocial aspects of the changing male vo

(2001) performed an action research study on the perceptions of adolesc

ing the voice change by interviewing eighth-grade male members of her

ble. She reported that the boys felt at ease with their vocal mutation and t

director (the researcher) and parents treated them positively throughout t

process. Killian (1997) surveyed and interviewed boys with changing v

as adult men on their perceptions of the voice change process. She note

the adult participants had emotional responses when recalling the mem

voice change. Nineteen percent of the adult participants in Killian's stud

voice change process to be a negative experience. Singers seemed to be

aware of the voice change than nonsingers and reported feeling phys

hoarseness during the voice change. Several adult male participants respo

quality of their mature voice was not as good as their prepubertal voice.

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fisher 279

Research m

from the lit

little is actu

their own s

capability to

control and

people's mot

ceived effic

make at sign

efficacy ten

and are mor

Within the

ment, moti

1986; Multo

1995; Zimm

Students' se

(Pintrich &

impact stud

by impleme

(Meece, Her

ment (Ande

Research al

music achie

McCormick

2004), jazz im

tal ensembl

McCormick (

in music per

a choral pro

more efficac

program to b

The purpose

sixth-, seve

sification sy

ing on stage

Method

Participants (N = 80) consisted of volunteer sixth-grade (n = 20), seventh-grade (n

27), and eighth-grade (n = 33) males recruited from one intermediate school choir ( n

5), one middle school choir ( n = 47), and two junior high school choirs ( n = 28) fro

four separate schools located in a south-central state in the United States. Ages range

from 11.33 to 14.73 years old ( M= 12.95, SD = 0.87). Choirs were selected through

purposive sampling in order to ensure that adequate representation of possible ma

participants was present.

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

280 Journal of Research in Music Education 62(3)

Instrument

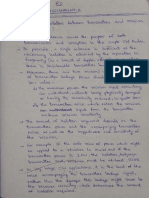

In order to examine the singing efficacy of participants, the researcher created the

Singing Self-Efficacy Scale for Emerging Adolescent Males (SSES) with assistance

from another researcher with expertise in writing self-efficacy scales based on the

Bandura model.1 The 26-item scale consisted of statements like, "I can sing well," "I

can sing without my voice cracking," and "I can sing soft in my low voice when asked

to." Participants read each item and responded by circling one number on a scale from

0 to 10 with 10 being confident I can do and 0 being cannot do at all (see Figure 1).

Responses from all items were summed, resulting in an overall singing self-efficacy

score for each participant that could range from 0 to 260, with 260 indicating extremely

high efficacy and 0 indicating extremely low efficacy. On the back of the scale, partici-

pants provided demographic information, including date of birth, grade level, and

number of years in an organized choir.

Before administering the instrument to participants, a content validity panel con-

sisting of three choir directors with experience in working with emerging adolescent

males reviewed the scale and offered recommended amendments. The scale also was

field tested with 22 males in Grades 6 through 8 who were enrolled in a middle school

choir. Students who participated in the field test were not included in the main study

sample. Items containing the terms falsetto, head voice , and chest voice confused

many of the students in the field test. On the basis of recommendations by the content

validity panel and field test participants, falsetto and head voice were replaced with

high voice , and chest voice was replaced with mid voice. The scale also was color

coded with every other item in blue so that participants would not respond accidentally

to the wrong item. Each participant was assigned randomly a numerical code, and that

corresponding numerical code was placed on the right-hand side of his SSES in order

to ensure his score on the various measures (SSES and vocal exercises data) was prop-

erly attributed to him. The SSES was assessed for reliability and was found to be

internally consistent (a = .92).

Procedures

Participants in the study were escorted to a separate room so that the remaining choir

members who elected not to participate in the study could continue with regular

rehearsal. Each participant was issued the 26-item SSES for Emerging Adolescent

Males and was told to review the instrument but wait to begin until instructions could

be given. I then encouraged the participants to read each item carefully and to respond

by circling only one number (0 to 10) for each item. Participants were encouraged to

consider their own confidence ability to perform a given task when responding to each

item and not to consider how they perceived peers or teachers would rate them. I

instructed each participant to review his responses to ensure that no item had been

skipped unintentionally and that no item had multiple responses. Administration of the

scale took approximately 10 min.

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fisher 28 1

Singing Self-efficacv Scale for Emerging Adolescent Males

Please rate each of the following statements based on how confident you are that YOU can do

each of the following.

Please circle one rating for each statement - please do not circle between numbers.

Cannot Moderately Confident

1. I can sing well. 01 23456789 10

2. I can sing in tune. 01 23456789 10

3. I can move from my mid voice to high voice 0 1 2345678910

with no problem.

4. I can easily sing in my high voice. 01 23456789 10

5. I can sing loud in my low voice when asked to. 0 1 2345678910

6. I can sing without my voice cracking. 01 23456789 10

7. I can sing loud in my high voice when asked to. 0123456789 10

8. I can match pitch in any octave. 0 1 2345678910

9. I can sing without a breathy sound in my mid 0 1 2345678910

voice.

10. I can sing soft when asked to. 01 23456789 10

11. I can sing in my high voice comfortably. 0 1 2345678910

12. I can sing soft in my high voice when asked to. 0 1 2345678910

13. I can control my singing in my mid voice. 0 1 23456789 10

14. I can change notes quickly when I sing. 01 23456789 10

15. I can sing with a good sound in my low voice. 0 1 2345678910

16. I can sing soft in my low voice when asked to. 0 1 2345678910

17. I can sing with a full voice in all parts of my q 1 23456789 10

voice.

18. I can sing without a breathy sound in my high 0 1 2345678910

voice.

19. I can hold a high note for a long time. 0123456789 10

20. I can sing every note in my voice when I slide 0 1 2345678910

from low to high.

21. I can control my singing in my high voice. 01 23456789 10

22. I can hold a low note for a long time. 01 23456789 10

23. I can sing higher notes without straining. 0 1 23456789 10

24. I can sing a long phrase of music without 0 1 2345678910

having to take extra breaths.

25. I can easily sing in my low voice. 0 1 2 3456 7 8910

26. I can sing without a breathy sound in my low 01 2345678910

voice.

Figure I . Singing Self-Efficacy Scale for emerging adolescent males.

After completing and submitting the SSES, I audio-recorded participants individu-

ally performing simple vocal exercises in order to attain each boy's vocal range.

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

282 Journal of Research in Music Education 62(3)

Unchanged Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 Stage 5

Midvmoe I M&tvotae !J Uiâvùim IIA New Vtetce lEreergmg Adufe Vosee

Figure 2. Cooksey's voice-change stages for emerging adolescent males.

Before privately recording each participant, I reviewed and rehearsed the v

sandi exercises with each individual. Participants were instructed to glide slow

their lowest to highest note on an ah vowel. They would repeat the ascendin

sando for a total of three times with the attempt to get higher each time. N

were instructed to glide from their highest to lowest note on an ah vowel thr

while attempting to get lower each time. This procedure for measuring voc

without a stimulus pitch has shown to be effective in previous research (Fish

Willis & Kenny, 2008).

Participants were recorded using the internal microphone of a MacBook P

GHz Intel Core 2 Duo; Apple, Inc.). Students were instructed to stand on a m

near the computer and were signaled to begin each exercise. I used Gar

4.1.2 (Apple, Inc.) software to record and analyze each participant's perf

After data were collected at each school, I privately listened to each partici

recorded sound files. The highest note reached in the ascending glissandi ex

was labeled as the highest terminal pitch (HTP), and the lowest note reached

descending glissandi exercises was labeled as the lowest terminal pitch (L

HTP and LTP established the vocal range of each singer. In addition to

each participant's HTP and LTP, I documented vocal characteristics, lik

tional gaps, presence of falsetto, and hoarseness. As Cooksey (1999) not

presence of falsetto with phonational gaps is one characteristic of Stages 3,

5 of the voice change.

To determine the pitch class of the HTP and LTP, I used the internal digita

included in the GarageBand software and documented the results in an Excel

sheet. Portions of the sound file often were isolated in order to determine mo

rately the HTP or LTP. Inteijudge reliability of this vocal range test was re

Fisher (2008, 2010) with 93% agreement for HTP and 90% agreement for LT

vocal ranges were established, each participant was classified using Cooksey'

of the male voice change (Figure 2). Participants classified as unchanged wer

as 0, while those in Stages 1 through 5 were coded with the corresponding nu

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fisher

Data Ana

Descriptiv

latedfor a

classificati

participan

exercises.

(Hz) in ord

subjects A

change, gr

the voice-

years , 2 =

with a non

Results

I calculated means and standard deviations for HTP and LTP for all participants ( N =

80). HTP ranged from 233.08 Hz (Bb3) to 1244.51 Hz (Eb6) (M = 557.85, SD =

237.08), and LTP ranged from 98.00 Hz (G2) to 293.67 Hz (D4) ( M= 176.79, SD =

37.60).

Each participant was classified according to Cooksey's voice-change classification

system. Twenty-nine participants (36.25%) were classified as unchanged voices, 15

participants (18.75%) were classified in Stage 1,11 participants (13.75%) were classi-

fied in Stage 2, 13 participants (16.25%) were classified in Stage 3, 13 participants

(16.25%) were classified in Stage 4, and 3 participants (3.75%) were classified in

Stage 5 of the voice change.

The reported choral experience of the participants ranged from 1 to 1 1 years, with

57.5% having 1 to 2 years of choral experience and 42.5% having 3 or more years of

choral experience. Types of choral experiences referenced by the participants included

participation in school, church, and/or community choirs.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for sixth-, seventh-, and eighth-grade par-

ticipants. Results indicated a steady decline of the mean HTP and LTP from sixth

through eighth grades. While the mean LTP seems to show a steady decline with each

successive grade level, the mean HTP lowered between seventh and eighth grades by

nearly 178 Hz (approximately a perfect 5th). Also, the percentages of unchanged

voices reduced from sixth to eighth grade, with the most sizeable reduction found

between seventh and eighth grades (-39.73%).

In order to determine the relationship of the voice change, grade level, and experi-

ence to participants' singing self-efficacy, a three-way between-subjects ANOVA was

used with singing self-efficacy serving as the dependent variable and voice-change

stage (0, 1, 2, 3, 4), grade level (6, 7, and 8), and experience (1 = 1 to 2 years of choral

experience , 2 = 3 or more years of choral experience) as the independent variables.

The reported choral experience of the participants ranged from 1 to 1 1 years, with

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

284 Journal of Research in Music Education 62(3)

Table I. Overall Vocal Range Descriptive Statistics for Sixth-, Seventh-, and

Participants.

Sixth Grade Seventh Grade Eighth Grade

Variable (n = 20) ( n = 27) (n = 33)

Mean age 1 1 .92 (0.47) 1 2.69 (0.4 1 ) 1 3.79 (0.4 1 )

Mean HTP (in Hz) 644.64 (208. 18) 61 9.87 (26 1 .27) 44 1 . 1 1 ( 1 88.65)

Mean LTP (in Hz) 208.42 (29.69) 1 77.44 (33.44) 1 54.39 (35.44)

Voice-change stage

Unchanged 55.00% 51.85% 12.12%

Changing 45.00% 48.15% 87.88%

1 30.00% 11.11% 18.18%

2 10.00% 14.81% 9.09%

3 5.00% 7.41% 24.24%

4 0.00% 11.11% 30.30%

5 0.00% 3.70% 6.06%

Note. Numbers in parenthe

57.5% having 1 to 2 y

choral experience. Par

while the remainder of

stage. Because only 3 p

were eliminated from

categorized in Stage 5

Table 2 shows the ove

variables. Participants

SSES, and participants

grade participants sco

choir scored much hig

were met for all varia

using Levene's statistic

.18), grade level (L = 0

Results of the ANOV

1.41,/? = .24, t|2 = .07,

effect for experience,

more years of experien

Discussion

The purposes of the study were to describe characteristics of the voice change in six

seventh-, and eighth-grade choir students using Cooksey's voice-change classifica

system and to determine if differences in singing self-efficacy exist dependin

stage of voice change, grade level, and experience.

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fisher

Table 2. Ov

Grade Leve

Variable M (SD) Skewness Kurtosis

Voice-change stage

0 178.24(31.37) -.03 -.87

1 163.93 (34.36) -.57 -.65

2 189.44(29.03) -.73 -.78

3 170.91 (59.74) -.54 -.34

4 176.62(42.55) .55 -.77

Grade level

6 164.55 (35.01) .08 -.90

7 182.46(33.64) -.06 -.10

8 176.58(43.66) -.60 .54

Experience

1 167.07(35.14) -.31 .40

2 187.87(40.37) -.68 .59

Results from this study reveal

participants classified in the la

and seventh-grade participan

unchanged versus 12% of eig

Wayman (2010) reported only

participants as unchanged. A co

from other students reveals ot

only 1 7% of the sixth-grade ma

33% of sixth-grade males to b

19% of sixth-grade males to be

These inconsistencies may be

Killian (1999) measured males

measured general music and no

males enrolled in band and choi

classified in each voice-change s

to have higher percentages of c

sisted only of males enrolled in

males who begin their voice ch

"good singers" and therefore a

show that vocal training during

change or at least minimize the

research is warranted to compa

in choir and those who are not t

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

286 Journal of Research in Music Education 62(3)

Results from this study also revealed that years of participation i

impact on emerging adolescent males' singing self-efficacy. This find

research that efficacy declines throughout schooling (Pintrich & Sch

can derive two explanations for this result. Choir directors of the par

study may have provided a positive and motivational climate in rehea

time, increased the singing efficacy of their students. This explanation

research that indicated teachers can impact student efficacy positivel

Kitsantas, 1996). If the effectiveness of these choir directors can

increased singing self-efficacy of choir members, then research on the

niques employed in these choir directors' rehearsals would be useful

music education community.

The other explanation for this finding could be that those with low

efficacy dropped out of choir and those with a higher singing efficacy c

research has shown that those with low efficacy, when faced with dif

give up (Bandura, 2006). Perhaps those with low singing-efficacy find

of vocal development (particularly through the vocal mutation) to be t

not worth continuing in choir. Though Klinedinst (1991) found stud

cept" in music to be a predictor variable of student retention in band,

needed to determine if singing self-efficacy plays a role in student re

ensembles.

It is interesting to note that the voice change did not seem to impact the singing

self-efficacy of the participants in this study. One might assume that the vocal difficul-

ties associated with the more advanced stages of the voice change would have an

impact on emerging adolescents' singing self-efficacy. One could conclude that the

small sample size and lack of equal representation of participants classified in each

voice change stage prohibited a statistically significant finding, but the low effect size

(r|2 = .07) indicates that a main effect, even with ideal sample size, may be improbable.

This finding may not support the assumption, then, that middle school and junior high

males drop out of choir because of their voice change. Perhaps performance achieve-

ment has more of an impact on self-efficacy and retention than simply the challenges

associated with the voice change. Authors of future research should consider examin-

ing if high singing self-efficacy correlates with high performance achievement in

emerging adolescent males, as has been found in other studies (McCormick &

McPherson, 2003; McPherson & McCormick, 2006).

In conclusion, the finding that emerging adolescent males who have participated in

a choral program for 3 or more years had a higher singing self-efficacy should provide

encouragement to the choral community. Choir directors strive to improve and increase

the singing abilities of their students, and the conclusions of this study suggest that,

over time, the self-perceptions of students' singing abilities may improve. Though the

voice change did not have an effect on singing self-efficacy, choir directors should

continue carefully and skillfully to guide these developing males through this tumultu-

ous period so that they emerge with confidence in their singing abilities.

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fisher 287

Declaration

The author de

and/or public

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this

article.

Note

1. Dr. Natalie Royston, assistant professor of music education at Iowa State University,

assisted with the creation of the Singing Self-Efficacy Scale.

References

Adler, A. (1999). A survey of teacher practices in working with male singers before and du

the voice change. Canadian Journal of Research in Music Education , 40(A), 29-33.

Anderman, E. M., Patrick, H., Hruda, L. Z., & Linnenbrink, E. (2002). Observing classro

goal structures to clarify and expand goal theory. In C. Midgley (Ed.), Goals, goal str

tures, and patterns of adaptive learning (pp. 243-278). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human beh

ior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds

Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (Vol. 5., pp. 307-337). Greenwich, CT: Information A

Bandura, A., & Schunk, D. (1981). Cultivating competence, self efficacy, and intrinsic in

est through proximal self motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology ,

587-598. doi: 10. 1037/0022-35 14.41 .3.586

Barresi, A. L., & Bless, D. (1984). The relation of selected aerodynamic variables to the percep-

tion of tessitura pitches in the adolescent changing voice. In M. Runfola (Ed.), Research

symposium on the male adolescent voice (pp. 97-1 10). Buffalo: State University of New

York Press.

Chapman, R. T. (1989). Training of the male adolescent singing voice prior to, during, and fol-

lowing voice mutation using the "vocal behavior training " methodology of Dr. Raymond

Smolover (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). New York University, New York, NY.

Cooksey, J. M. (1984). The male adolescent changing voice: Some new perspectives. In M.

Runfola (Ed.), Research symposium on the male adolescent voice (pp. 4-59). Buffalo: State

University of New York Press.

Cooksey, J. M. (1985). Vocal-acoustical measures of prototypical patterns related to voice

maturation in the adolescent male. In V. Lawrence (Ed.), Transcripts of the thirteenth

symposium, Care of the Professional Voice, Part II: Vocal therapeutics and medicine

(pp. 469-480). New York: NY: Voice Foundation.

Cooksey, J. M. (1999). Working with the adolescent voice. St. Louis, MO: Concordia.

Cooksey, J. M., & Welch, G. F. (1998). Adolescence, singing development and national

curricula design. British Journal of Music Education , /5(1), 99-111. doi: 10. 10 17/

S026505 1 70000379X

Cooper, I., & Kuersteiner, J. K. (1970). Teaching junior high school music. Boston, MA: Allyn

and Bacon.

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

288 Journal of Research in Music Education 62(3)

Davison, P. D. (2010). The role of self-efficacy and modeling in improvisation am

diate instrumental music students. Journal of Band Research , 45( 2), 42-58.

Fisher, R. A. (2008). The effect of ethnicity on the age-of onset of the mal

(Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of North Texas, Denton.

Fisher, R. A. (2010). Effect of ethnicity on the age of onset of the male voice ch

Research in Music Education , 58, 1 16-130. doi: 10.1 177/002242941037137

Friesen, J. H. (1972). Vocal mutation in the adolescent male: Its chronology

son with fluctuations in musical interest (Unpublished doctoral dissertation)

Oregon, Eugene.

Groom, M. D. (1984). A descriptive analysis of development in adolescent ma

the summer time period. In M. Runfola (Ed.), Research symposium on the m

voice (pp. 80-85). Buffalo: State University of New York Press.

Harris, L. D. (1996). A study of intensity control in males with developing voic

for pitch range and tessitura (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Univer

Texas, Denton.

Hollien, H., Green, R., & Massey, K. (1994). Longitudinal research on adolesce

in males. Journal of Acoustical Society of America, 96 , 2646-2654. doi: 10.1

Hook, S. (2005). Vocal agility in the male adolescent changing voice (Unpubl

dissertation). University of Missouri, Columbia.

Karr, J. P. (1988). A vocal survey of male adolescent voices grades six throug

on the incidence of changed voices with relation to extant theories (Unpubli

thesis). University of Louisville, Kentucky.

Kennedy, M. C. (2004). "It's a metamorphosis": Guiding the voice change at the

American Boychoir School. Journal of Research in Music Education , 52, 264-280.

doi: 10.2307/3345859

Killian, J. N. (1997). Perceptions of the voice-change process: Male adult versus adolescent

musicians and nonmusicians. Journal of Research in Music Education , 45 , 521-535.

doi: 10.2307/3345420

Killian, J. N. (1999). A description of vocal maturation among 5th- and 6th-grade boys. Journal

of Research in Music Education , 47 , 357-369. doi: 10.2307/3345490

Killian, J. N. (2003). Choral director's self reports of accommodations made for boys' changing

voices. In R. Duke & J. Henninger (Eds.), Texas Music Education Research 2003. Austin,

TX: Texas Music Educators Association. Retrieved from http://www.tmea.org/080_

College/Research/Kil2003 .pdf

Killian, J. N., & Wayman, J. B. (2010). A descriptive study of vocal maturation among male

adolescent vocalists and instrumentalists. Journal of Research in Music Education , 58 ,

5-19. doi: 10.1 177/0022429409359941

Klinedinst, R. E. (1991). Predicting performance achievement and retention of fifth-grade

instrumental students. Journal of Research in Music Education , 39, 225-238.

Kriekland, P. D. (2001). The perceptions of boys regarding the changing voice (Unpublished

master's thesis). Michigan State University, Lansing.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Larkin, K. C. (1986). Self-efficacy in the prediction of academic

performance and perceived career options. Journal of Counseling Psychology , 33 , 265-

269. doi: 1 0. 1 037/0022-0 1 67.33.3.265

McCormick, J., & McPherson, G. (2003). The role of self-efficacy in a musical performance

examination: An exploratory structural equation analysis. Psychology of Music , 31 , 37-5 1 .

doi: 1 0. 1 1 77/030573560303 1 00 1 322

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fisher 289

McKenzie, D

University P

McPherson, G

nents of mu

98-102.

McPherson, G. E., & McCormick, J. (2006). Self-efficacy and music performance. Psychology

of Music, 34 , 322-336. doi: 10.1 177/0305735606064841

Meece, J. L., Herman, P., & McCombs, B. (2003). Relations of learner-centered teaching prac-

tices to adolescents' achievement goals. International Journal of Educational Research ,

39 , 457-475. doi:10.1016.j.ijer.2004.06.009

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991 ). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic

outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology , 38 , 30-38.

doi: 1 0. 1 037/0022-0 1 67.38. 1 .30

Nelson, D. L. (1997). High-risk adolescent males , self efficacy, and choral performance: An

investigation of affective intervention (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Arizona State

University, Tempe.

Nielsen, S. G. (2004). Strategies and self-efficacy beliefs in instrumental and vocal individual

practice: A study of students in higher music education. Psychology of Music, 52, 41 8-43 1 .

doi: 10.1 177/0305735604046099

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in achievement settings. Review of Educational

Research , 66 , 543-578. doi: 10.3 102/00346543066004543

Pajares, F., & Valiante, G. (1999). Grade level and gender differences in the writing self-

beliefs of middle school students. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 24 , 390-405.

doi: 10.1006/ceps. 1998.0995

Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (1996). Motivation in education: Theory , research , and appli-

cations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Rutkowski, J. (1984). Two year results of a longitudinal study investigating the validity of

Cooksey's theory for training the adolescent male voice. In M. Runfola (Ed.), Research

symposium on the male adolescent voice (pp. 86-96). Buffalo: State University of New

York Press.

Schunk, D. H. (1995). Self-efficacy and education and instruction. In J. E. Maddux (Ed.), Self-

efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 281-303).

New York, NY: Plenum.

Steele, N. A. (2009). The relationship between collegiate band members 'preferences of teacher

interpersonal behavior and perceived self-efficacy (Doctoral dissertation). Available from

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3377468)

Sturdy, L. A. ( 1 939). The status of voice range of junior high school boys (Unpublished master's

thesis). University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Swanson, F. J. (1977). The male singing voice ages 8 to 18. Cedar Rapids, I A: Laurance.

Usher, A. L. (2005). Tracking the adolescent male voice mutation: Public middle school choral

teachers ' preparation, practices, and success (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Kent

State University, Kent, OH.

Watson, K. E. (2010). The effects of aural versus notated instructional materials on achieve-

ment and self-efficacy in jazz improvisation. Journal of Research of Music Education , 58,

240-259. doi: 10.1 177/00224294103771 15

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

290 Journal of Research in Music Education 62(3)

Willis, E., & Kenny, D. T. (2008). Relationship between weight, speaking fundam

quency, and the appearance of phonational gaps in the adolescent male chan

Journal of Voice, 22, 451^171. doi: 10. 1016/j.jvoice.2006.1 1.007

Zimmerman, B. J., & Bandura, A. (ivy4). impact ot selî-reguiatory intiuences on writ-

ing course attainment. American Educational Research Journal , 37, 845-862.

doi: 1 0.3 1 02/000283 1 203 1 004845

Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic

attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational

Research Journal, 29 , 663-676. doi: 10.3 102/000283 12029003663

Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (1996). Self-regulated learning of a motoric skill: The

role of goal setting and self-monitoring. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology , 8, 60-75.

doi: 1 0. 1 080/ 1 04 1 3209608406308

Author Biography

Ryan A. Fisher is assistant professor of music education and music education division head at

the University of Memphis. His research interests include the male voice change and self-

efficacy in music teaching and learning.

Submitted August 21, 2012; accepted June 24, 2013.

This content downloaded from

132.174.253.85 on Wed, 13 Mar 2024 06:34:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- 50 Awesome Blues Riffs For Diatonic Harmonica, Vol.17 by Ben Hewlett & Paul LennonDocument40 pages50 Awesome Blues Riffs For Diatonic Harmonica, Vol.17 by Ben Hewlett & Paul LennonAndré Calixto67% (3)

- Gary E. McPherson - Five Aspects of Musical PerformanceDocument8 pagesGary E. McPherson - Five Aspects of Musical PerformanceArturo González FloresNo ratings yet

- Note!: Kyrie Eleison (Lord Have Mercy) From The Missa de AngelisDocument1 pageNote!: Kyrie Eleison (Lord Have Mercy) From The Missa de AngelisKLMN Music100% (1)

- SMG Arpeggio Compendium Complete Book For Guitar PDFDocument75 pagesSMG Arpeggio Compendium Complete Book For Guitar PDFFF100% (1)

- Sweet AdolescentFemaleChanging 2015Document20 pagesSweet AdolescentFemaleChanging 2015stephenieleevos1No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 85.247.100.146 On Mon, 05 Apr 2021 11:29:03 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 85.247.100.146 On Mon, 05 Apr 2021 11:29:03 UTCInês SacaduraNo ratings yet

- DAVIDSON, Jane The Effects of Gesture and Movement Training On The Intonation of Children's Singing in Vocal Warm-Up SessionsDocument15 pagesDAVIDSON, Jane The Effects of Gesture and Movement Training On The Intonation of Children's Singing in Vocal Warm-Up SessionsNery BorgesNo ratings yet

- Sweet VoiceChangeSinging 2018Document18 pagesSweet VoiceChangeSinging 2018stephenielee.kodalymattersNo ratings yet

- Daugherty Et Al 2010 Student Voice Use and Vocal Health During An All State Chorus EventDocument22 pagesDaugherty Et Al 2010 Student Voice Use and Vocal Health During An All State Chorus EventDiana SilvaNo ratings yet

- Construction of MusicDocument8 pagesConstruction of MusicArdian AriefNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc., MENC: The National Association For Music Education Journal of Research in Music EducationDocument16 pagesSage Publications, Inc., MENC: The National Association For Music Education Journal of Research in Music EducationCláudioNo ratings yet

- Crist, The Effect of Tempo and Dynamic ChangesDocument16 pagesCrist, The Effect of Tempo and Dynamic ChangesDomen MarincicNo ratings yet

- Hallam Show. Constructions of Musical AbilityDocument8 pagesHallam Show. Constructions of Musical AbilityOksana TverdokhlebovaNo ratings yet

- Accompaniment EffectsDocument16 pagesAccompaniment EffectsPaolo FratelloNo ratings yet

- Yoon & Feliciano 2007 Stimulus PairingDocument14 pagesYoon & Feliciano 2007 Stimulus PairinggiselleprovencioNo ratings yet

- From Child To Musician Skill Development During The Begining Stages of Learning An InstrumentDocument31 pagesFrom Child To Musician Skill Development During The Begining Stages of Learning An InstrumentHeidy Carvajal GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Sources of Self-Efficacy Among Secondary School Music StudentsDocument16 pagesMeasuring The Sources of Self-Efficacy Among Secondary School Music StudentsInês SacaduraNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument5 pagesArticleBIG DUCKNo ratings yet

- Conceptions of Musical AbilityDocument22 pagesConceptions of Musical AbilityResa RespatiNo ratings yet

- Sight-Singin Instruction in The Choral EnsembleDocument12 pagesSight-Singin Instruction in The Choral EnsembleradamirNo ratings yet

- Uat PeredictsDocument25 pagesUat PeredictsAlexandreNo ratings yet

- Larson - The Effects of Chamber Music Experience On Music Performance Achievement, Motivation and Attitude Among High School Band StudentsDocument24 pagesLarson - The Effects of Chamber Music Experience On Music Performance Achievement, Motivation and Attitude Among High School Band StudentsLuis Varela CarrizoNo ratings yet

- Cmev39 Nichols ProofDocument22 pagesCmev39 Nichols ProofIntan MeeyorNo ratings yet

- Music Speech and SongDocument11 pagesMusic Speech and SongThmuseoNo ratings yet

- Music Research PapersDocument4 pagesMusic Research Papers33 Siddhant JainNo ratings yet

- University of Illinois Press Council For Research in Music EducationDocument8 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press Council For Research in Music EducationChristoph GenzNo ratings yet

- Davis 1998Document14 pagesDavis 1998Sofia GatoNo ratings yet

- Effects of A Preparatory Singing Pattern On Melodic Dictation SuccessDocument12 pagesEffects of A Preparatory Singing Pattern On Melodic Dictation Successyi luNo ratings yet

- University of Illinois Press Council For Research in Music EducationDocument15 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press Council For Research in Music EducationChristoph GenzNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Music On Short-Term and Long-Term MemoryDocument25 pagesThe Effects of Music On Short-Term and Long-Term MemoryLustre GlarNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Children Toward Singing and Choir Participation and Assessed Singing SkillDocument13 pagesAttitudes of Children Toward Singing and Choir Participation and Assessed Singing Skillli manniiiNo ratings yet

- Vocal Improvisation and Creative Thinking by Australian and American University Jazz SingersDocument13 pagesVocal Improvisation and Creative Thinking by Australian and American University Jazz SingersDévényi-Bakos BettinaNo ratings yet

- Garofalo and Whaley, COMPARISON OF THE UNIT STUDY AND TRADITIONAL APPROACHES FOR TEACHING MUSIC THROUGH SCHOOL BAND PERFORMANCEDocument7 pagesGarofalo and Whaley, COMPARISON OF THE UNIT STUDY AND TRADITIONAL APPROACHES FOR TEACHING MUSIC THROUGH SCHOOL BAND PERFORMANCEJamesNo ratings yet

- Works Works: Swarthmore College Swarthmore CollegeDocument16 pagesWorks Works: Swarthmore College Swarthmore CollegejajajaneinNo ratings yet

- 14797Document26 pages14797wen monteNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Mediated Music Lessons On The Development of At-Risk Elementary School ChildrenDocument5 pagesThe Effect of Mediated Music Lessons On The Development of At-Risk Elementary School ChildrenKarina LópezNo ratings yet

- Feasibility of Using An Augmented Immersive Virtual Reality Learning Environment To Enhance Music Conducting SkillsDocument12 pagesFeasibility of Using An Augmented Immersive Virtual Reality Learning Environment To Enhance Music Conducting Skillsrani rasyidaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document12 pagesJurnal 2mang jajangNo ratings yet

- Academic Performance and Music PreferenceDocument33 pagesAcademic Performance and Music PreferencePrecious Heiress MarasiganNo ratings yet

- Childhood Preservice Teachers' Confidence in Singing: EarlyDocument12 pagesChildhood Preservice Teachers' Confidence in Singing: EarlyMiharu NishaNo ratings yet

- Three Keys To Effective Choral RehearsalDocument11 pagesThree Keys To Effective Choral RehearsalMaurice Dan GeroyNo ratings yet

- Vocalizations of Infants (9-11 Months Old) in Response To Musical and Linguistic StimuliDocument16 pagesVocalizations of Infants (9-11 Months Old) in Response To Musical and Linguistic StimuliLaura F MerinoNo ratings yet

- Articole MeloterapieDocument46 pagesArticole MeloterapiePatricia Andreea BerbecNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 200.144.238.1 On Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 200.144.238.1 On Thu, 17 Jun 2021 12:14:24 UTCAlessandra ZanchettaNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument12 pagesUntitled Documentapi-329934174No ratings yet

- Aural Dictation Affects High Achievement in Sight Singing PDFDocument19 pagesAural Dictation Affects High Achievement in Sight Singing PDFSama Pia100% (1)

- Factors and Abilities Influencing Sightreading Skill in MusicDocument17 pagesFactors and Abilities Influencing Sightreading Skill in MusicTeresaPeraltaCalvilloNo ratings yet

- Francois Et Al 2013 - 8 Years Old With 2 Years StudyDocument6 pagesFrancois Et Al 2013 - 8 Years Old With 2 Years StudyfarawaheedaNo ratings yet

- Hallam Changes in Motivation PDFDocument25 pagesHallam Changes in Motivation PDFboviaoNo ratings yet

- Importance of Musicin ECEDocument10 pagesImportance of Musicin ECEdasaiyahslb957No ratings yet

- Student Musicians'Ear-Playing Ability As AFunction of VernacularMusic ExperiencesDocument15 pagesStudent Musicians'Ear-Playing Ability As AFunction of VernacularMusic ExperiencesSTELLA FOURLA100% (1)

- University of Illinois Press, Council For Research in Music Education Bulletin of The Council For Research in Music EducationDocument14 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press, Council For Research in Music Education Bulletin of The Council For Research in Music EducationJeon KookNo ratings yet

- Timbre Choirs - Final PaperDocument10 pagesTimbre Choirs - Final Paperapi-285912473No ratings yet

- Franca & Wagner 2014effects of Vocal Demands On Voice Performance of Student SingersDocument9 pagesFranca & Wagner 2014effects of Vocal Demands On Voice Performance of Student SingersAira RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Singing Teachers Talk Too MuchDocument11 pagesSinging Teachers Talk Too Muchapinporn chaiwanichsiri100% (2)

- The Effects of Classical Guitar Ensembles On Student Self-Perceptions and Acquisition of Music SkillsDocument12 pagesThe Effects of Classical Guitar Ensembles On Student Self-Perceptions and Acquisition of Music SkillsetikaNo ratings yet

- 2016 Articol RAE Auditia MuzicalaDocument6 pages2016 Articol RAE Auditia MuzicalaDorina IuscaNo ratings yet

- GerryUnrauTrainor 2012 PDFDocument11 pagesGerryUnrauTrainor 2012 PDFLaura F MerinoNo ratings yet

- CurwenDocument5 pagesCurwenWan Nurhakimah BalqisNo ratings yet

- Vocal Warm-Up Practices and PerceptionsDocument10 pagesVocal Warm-Up Practices and PerceptionsLoreto SaavedraNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S019188691400556X MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S019188691400556X MainkuspiluNo ratings yet

- Can Music Help Special Education Students Control Negative Behavior in the Classroom?From EverandCan Music Help Special Education Students Control Negative Behavior in the Classroom?No ratings yet

- The Child-Voice in Singing treated from a physiological and a practical standpoint and especially adapted to schools and boy choirsFrom EverandThe Child-Voice in Singing treated from a physiological and a practical standpoint and especially adapted to schools and boy choirsNo ratings yet

- Latiahan Soal ReadingDocument10 pagesLatiahan Soal ReadingWakhidNo ratings yet

- Why Is Music So WonderfulDocument8 pagesWhy Is Music So WonderfulGeorgette CharalampidouNo ratings yet

- CQ-D1703W Operating InstructionsDocument52 pagesCQ-D1703W Operating InstructionsAlexey OnishenkoNo ratings yet

- Kids A2.1.Final Test Versão NunoDocument5 pagesKids A2.1.Final Test Versão NunoNuno RibeiroNo ratings yet

- I Would Like To Join A Musical Band, A Choir and A Dance Group. I Have Taken The ABRSM GradeDocument3 pagesI Would Like To Join A Musical Band, A Choir and A Dance Group. I Have Taken The ABRSM GradeJenise ThomasNo ratings yet

- Booklet ArrauDocument44 pagesBooklet Arraubulinuta2004No ratings yet

- How To Start A Record Label in 2020Document8 pagesHow To Start A Record Label in 2020Mercedes Moss100% (1)

- Rs Assi2Document9 pagesRs Assi2Pavan ParthikNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 7 q1 Week 1 Music 1Document11 pagesMapeh 7 q1 Week 1 Music 1FrennyNo ratings yet

- Crown Him With Many Crowns DDocument2 pagesCrown Him With Many Crowns DJhinNo ratings yet

- Star Delta Transformation: Dr.V.Joshi ManoharDocument14 pagesStar Delta Transformation: Dr.V.Joshi ManoharhariNo ratings yet

- Taylor Swift LyricsDocument68 pagesTaylor Swift LyricsAan R SyahrainNo ratings yet

- Abba Gold Violin IDocument4 pagesAbba Gold Violin IPABLO GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Annexure-7. M.A. Hindustani Music (Final)Document51 pagesAnnexure-7. M.A. Hindustani Music (Final)Dipti GuptaNo ratings yet

- 38521-1 v17.4Document1,377 pages38521-1 v17.4Oscar Elena VarelaNo ratings yet

- Rev'z Song LyricsDocument27 pagesRev'z Song LyricsdishkuNo ratings yet

- Focus2 2E Review Test 1 Units1 2 Speaking GroupA B ANSWERSDocument3 pagesFocus2 2E Review Test 1 Units1 2 Speaking GroupA B ANSWERSlitvindima04No ratings yet

- RSPBA MAP The Piper's Cave For BagpipesDocument1 pageRSPBA MAP The Piper's Cave For BagpipesJulianNo ratings yet

- AdorkableDocument194 pagesAdorkableAya MhNo ratings yet

- Mekelle University: Eit-M School of Electrical and Computer EngineeringDocument35 pagesMekelle University: Eit-M School of Electrical and Computer EngineeringFìrœ Lōv MånNo ratings yet

- Synthesizers A Brief IntroductionDocument60 pagesSynthesizers A Brief IntroductionAyoub AmriNo ratings yet

- Labs Us List Per Subject Schedule UpdatedDocument12 pagesLabs Us List Per Subject Schedule UpdatedArlene ZonioNo ratings yet

- ITZY Wannabe (ENGLISH LYRICS)Document1 pageITZY Wannabe (ENGLISH LYRICS)Zyann Key AbuganNo ratings yet

- Claudio VeeraragooDocument2 pagesClaudio VeeraragoobernmamNo ratings yet

- Sax Fingering ChartDocument7 pagesSax Fingering ChartAnthony strelzowNo ratings yet

- Packet 3Document11 pagesPacket 3Jeremy SyNo ratings yet

- Corre Corazon PianoDocument3 pagesCorre Corazon PianoRojas Villacrez JesusNo ratings yet