Professional Documents

Culture Documents

VARC 15 Exam Portal

VARC 15 Exam Portal

Uploaded by

Suraj DasguptaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

VARC 15 Exam Portal

VARC 15 Exam Portal

Uploaded by

Suraj DasguptaCopyright:

Available Formats

VARC 15 2023

Scorecard

Accuracy

119166 Qs Analysis

16

Solutions

Bookmarks

Sec 1

Directions for questions 1-4: The following passage

consists of a set of six questions. Read the passage

and answer the questions that follow.

If someone asked you to list the defining features of

being human, you might cite our formidable linguistic

prowess, our finely tuned moral sense, and our

unrivalled capacity for creative invention. All these have

no doubt played their parts in making us the globally

dominant species that we are, enabling us to share

ideas, form close-knit communities, and eke out an

existence in an unprecedented range of environments.

Yet an equally important factor in the success of our

species has been our capacity for precise imitation.

Copying other people is what creates the very possibility

of complex culture, and cultural imitation is a universal

human trait. Every person on the planet (barring those

with certain cognitive deficits) is equipped to pick up

the knowledge and skills nurtured by any culture that

has existed. If a Palaeolithic infant time-travelled to the

present, she would develop much like any other normal

child, learning to read and write and to use all the

advanced technologies of the 21st century.

In addition to technical skills, however, we also imitate

behaviours where the link between what we do and

some hoped-for outcome is much less clear — rituals

being a prime example. People engage in ritual activities

for all sorts of reasons: to commune with the divine, to

mark changes in status, to bury the dead, and

sometimes for no reason at all that anybody can

remember. No matter what the goal is, however, the

actual mechanisms by which rituals are supposed to

work are typically inscrutable. There’s no clear causal

process: you simply have to do things this way, and

that’s that.

This has some remarkable consequences. Human

populations living side-by-side tend to have a lot in

common. They adopt the same basic techniques of

production, use similar tools and natural resources, live

in similar kinds of houses and so on. At the level of

practical affairs, there might be little to tell them apart.

However, their rituals are a different story altogether.

Arbitrary conventions on how to achieve certain goals —

placate the gods, or ensure an adequate crop — can

assume any pattern: in straightforward physical terms,

they don’t actually have to do anything. And yet they are

far from impotent. Indeed, in social terms they can have

very significant effects. To start with, they serve as

admirable group markers precisely because they are of

no use to those outside the group. And they don’t just

demarcate people. Rituals also bind them together.

How? And how far can they stretch?

The very fact that ceremonial actions are not intelligible

in practical terms means that we can endow them with

many possible functions and meanings. Furthermore, if

we don’t know very much about what others are

thinking, we tend to believe that what is personally

meaningful about the experience of joining in is shared

by everyone else. This is the ‘false consensus bias’, well-

documented in social psychology. These two facts

together explain why painful or frightening (in the

jargon, ‘dysphoric’) rituals — such as traumatic

initiations and hazing practices — lead to bonding.

Whatever each performer thinks or feels about the

experience, they all assume that the other participants

feel the same as them. The same goes for non-ritual

experiences, too: the more painful or horrifying it is, the

stronger the effect. If we are hurt in a plane crash, we

might dwell on it for years afterwards, considering how

it changed our lives and wondering why it happened,

how it could have been different and so on. Discovering

other people who share this experience can be

powerful: they seem uniquely placed to understand us in

a way that others simply can’t. In fact, we might go so

far as to say that people have no right to comment if

they haven’t been through what we have been through.

Ritual is able to work with these feelings – provoking

them as part of an intense experience of bonding with a

group.

Ritual is popularly misconstrued as an exotic, even

quirky topic — a facet of human nature that, along with

beliefs in supernatural agents and magical spells, is

little more than a curious fossil of pre-scientific culture,

doomed to eventual extinction in the wake of rational

discovery and invention. Nothing could be further from

the truth. Humans are as ritualistic today as they have

ever been.

Q.1 [11916616]

What is the main focus of the author in this passage?

1 Rituals have unscientific origins and are doomed to

eventual extinction.

2 Painful experiences can lead to strong bonding

between humans.

3 Rituals serve many socio-emotional purposes and

are likely to continue to be in existence.

4 Linguistic prowess and ritual oriented bonding are

the main reasons behind the human supremacy in the

world.

A w

Directions for questions 1-4: The following passage

consists of a set of six questions. Read the passage

and answer the questions that follow.

If someone asked you to list the defining features of

being human, you might cite our formidable linguistic

prowess, our finely tuned moral sense, and our

unrivalled capacity for creative invention. All these have

no doubt played their parts in making us the globally

dominant species that we are, enabling us to share

ideas, form close-knit communities, and eke out an

existence in an unprecedented range of environments.

Yet an equally important factor in the success of our

species has been our capacity for precise imitation.

Copying other people is what creates the very possibility

of complex culture, and cultural imitation is a universal

human trait. Every person on the planet (barring those

with certain cognitive deficits) is equipped to pick up

the knowledge and skills nurtured by any culture that

has existed. If a Palaeolithic infant time-travelled to the

present, she would develop much like any other normal

child, learning to read and write and to use all the

advanced technologies of the 21st century.

In addition to technical skills, however, we also imitate

behaviours where the link between what we do and

some hoped-for outcome is much less clear — rituals

being a prime example. People engage in ritual activities

for all sorts of reasons: to commune with the divine, to

mark changes in status, to bury the dead, and

sometimes for no reason at all that anybody can

remember. No matter what the goal is, however, the

actual mechanisms by which rituals are supposed to

work are typically inscrutable. There’s no clear causal

process: you simply have to do things this way, and

that’s that.

This has some remarkable consequences. Human

populations living side-by-side tend to have a lot in

common. They adopt the same basic techniques of

production, use similar tools and natural resources, live

in similar kinds of houses and so on. At the level of

practical affairs, there might be little to tell them apart.

However, their rituals are a different story altogether.

Arbitrary conventions on how to achieve certain goals —

placate the gods, or ensure an adequate crop — can

assume any pattern: in straightforward physical terms,

they don’t actually have to do anything. And yet they are

far from impotent. Indeed, in social terms they can have

very significant effects. To start with, they serve as

admirable group markers precisely because they are of

no use to those outside the group. And they don’t just

demarcate people. Rituals also bind them together.

How? And how far can they stretch?

The very fact that ceremonial actions are not intelligible

in practical terms means that we can endow them with

many possible functions and meanings. Furthermore, if

we don’t know very much about what others are

thinking, we tend to believe that what is personally

meaningful about the experience of joining in is shared

by everyone else. This is the ‘false consensus bias’, well-

documented in social psychology. These two facts

together explain why painful or frightening (in the

jargon, ‘dysphoric’) rituals — such as traumatic

initiations and hazing practices — lead to bonding.

Whatever each performer thinks or feels about the

experience, they all assume that the other participants

feel the same as them. The same goes for non-ritual

experiences, too: the more painful or horrifying it is, the

stronger the effect. If we are hurt in a plane crash, we

might dwell on it for years afterwards, considering how

it changed our lives and wondering why it happened,

how it could have been different and so on. Discovering

other people who share this experience can be

powerful: they seem uniquely placed to understand us in

a way that others simply can’t. In fact, we might go so

far as to say that people have no right to comment if

they haven’t been through what we have been through.

Ritual is able to work with these feelings – provoking

them as part of an intense experience of bonding with a

group.

Ritual is popularly misconstrued as an exotic, even

quirky topic — a facet of human nature that, along with

beliefs in supernatural agents and magical spells, is

little more than a curious fossil of pre-scientific culture,

doomed to eventual extinction in the wake of rational

discovery and invention. Nothing could be further from

the truth. Humans are as ritualistic today as they have

ever been.

Q.2 [11916616]

What, according to the author, is inscrutable about

rituals?

1 Why rituals exist

2 How rituals work

3 How humans bond

4 How rituals guide scientists

A w

Directions for questions 1-4: The following passage

consists of a set of six questions. Read the passage

and answer the questions that follow.

If someone asked you to list the defining features of

being human, you might cite our formidable linguistic

prowess, our finely tuned moral sense, and our

unrivalled capacity for creative invention. All these have

no doubt played their parts in making us the globally

dominant species that we are, enabling us to share

ideas, form close-knit communities, and eke out an

existence in an unprecedented range of environments.

Yet an equally important factor in the success of our

species has been our capacity for precise imitation.

Copying other people is what creates the very possibility

of complex culture, and cultural imitation is a universal

human trait. Every person on the planet (barring those

with certain cognitive deficits) is equipped to pick up

the knowledge and skills nurtured by any culture that

has existed. If a Palaeolithic infant time-travelled to the

present, she would develop much like any other normal

child, learning to read and write and to use all the

advanced technologies of the 21st century.

In addition to technical skills, however, we also imitate

behaviours where the link between what we do and

some hoped-for outcome is much less clear — rituals

being a prime example. People engage in ritual activities

for all sorts of reasons: to commune with the divine, to

mark changes in status, to bury the dead, and

sometimes for no reason at all that anybody can

remember. No matter what the goal is, however, the

actual mechanisms by which rituals are supposed to

work are typically inscrutable. There’s no clear causal

process: you simply have to do things this way, and

that’s that.

This has some remarkable consequences. Human

populations living side-by-side tend to have a lot in

common. They adopt the same basic techniques of

production, use similar tools and natural resources, live

in similar kinds of houses and so on. At the level of

practical affairs, there might be little to tell them apart.

However, their rituals are a different story altogether.

Arbitrary conventions on how to achieve certain goals —

placate the gods, or ensure an adequate crop — can

assume any pattern: in straightforward physical terms,

they don’t actually have to do anything. And yet they are

far from impotent. Indeed, in social terms they can have

very significant effects. To start with, they serve as

admirable group markers precisely because they are of

no use to those outside the group. And they don’t just

demarcate people. Rituals also bind them together.

How? And how far can they stretch?

The very fact that ceremonial actions are not intelligible

in practical terms means that we can endow them with

many possible functions and meanings. Furthermore, if

we don’t know very much about what others are

thinking, we tend to believe that what is personally

meaningful about the experience of joining in is shared

by everyone else. This is the ‘false consensus bias’, well-

documented in social psychology. These two facts

together explain why painful or frightening (in the

jargon, ‘dysphoric’) rituals — such as traumatic

initiations and hazing practices — lead to bonding.

Whatever each performer thinks or feels about the

experience, they all assume that the other participants

feel the same as them. The same goes for non-ritual

experiences, too: the more painful or horrifying it is, the

stronger the effect. If we are hurt in a plane crash, we

might dwell on it for years afterwards, considering how

it changed our lives and wondering why it happened,

how it could have been different and so on. Discovering

other people who share this experience can be

powerful: they seem uniquely placed to understand us in

a way that others simply can’t. In fact, we might go so

far as to say that people have no right to comment if

they haven’t been through what we have been through.

Ritual is able to work with these feelings – provoking

them as part of an intense experience of bonding with a

group.

Ritual is popularly misconstrued as an exotic, even

quirky topic — a facet of human nature that, along with

beliefs in supernatural agents and magical spells, is

little more than a curious fossil of pre-scientific culture,

doomed to eventual extinction in the wake of rational

discovery and invention. Nothing could be further from

the truth. Humans are as ritualistic today as they have

ever been.

Q.3 [11916616]

According to the passage, which of the following will be

an example of “false-consensus bias”?

1 A bullied child assuming that everyone in its class

is a bully.

2 A doctor assuming that his unorthodox treatment

method will be endorsed by legal practitioners.

3 A political worker assuming that all politicians are

crooks.

4 A devout follower of a spiritual leader assuming

that all the other devotees of his Guru are sincere.

A w

Directions for questions 1-4: The following passage

consists of a set of six questions. Read the passage

and answer the questions that follow.

If someone asked you to list the defining features of

being human, you might cite our formidable linguistic

prowess, our finely tuned moral sense, and our

unrivalled capacity for creative invention. All these have

no doubt played their parts in making us the globally

dominant species that we are, enabling us to share

ideas, form close-knit communities, and eke out an

existence in an unprecedented range of environments.

Yet an equally important factor in the success of our

species has been our capacity for precise imitation.

Copying other people is what creates the very possibility

of complex culture, and cultural imitation is a universal

human trait. Every person on the planet (barring those

with certain cognitive deficits) is equipped to pick up

the knowledge and skills nurtured by any culture that

has existed. If a Palaeolithic infant time-travelled to the

present, she would develop much like any other normal

child, learning to read and write and to use all the

advanced technologies of the 21st century.

In addition to technical skills, however, we also imitate

behaviours where the link between what we do and

some hoped-for outcome is much less clear — rituals

being a prime example. People engage in ritual activities

for all sorts of reasons: to commune with the divine, to

mark changes in status, to bury the dead, and

sometimes for no reason at all that anybody can

remember. No matter what the goal is, however, the

actual mechanisms by which rituals are supposed to

work are typically inscrutable. There’s no clear causal

process: you simply have to do things this way, and

that’s that.

This has some remarkable consequences. Human

populations living side-by-side tend to have a lot in

common. They adopt the same basic techniques of

production, use similar tools and natural resources, live

in similar kinds of houses and so on. At the level of

practical affairs, there might be little to tell them apart.

However, their rituals are a different story altogether.

Arbitrary conventions on how to achieve certain goals —

placate the gods, or ensure an adequate crop — can

assume any pattern: in straightforward physical terms,

they don’t actually have to do anything. And yet they are

far from impotent. Indeed, in social terms they can have

very significant effects. To start with, they serve as

admirable group markers precisely because they are of

no use to those outside the group. And they don’t just

demarcate people. Rituals also bind them together.

How? And how far can they stretch?

The very fact that ceremonial actions are not intelligible

in practical terms means that we can endow them with

many possible functions and meanings. Furthermore, if

we don’t know very much about what others are

thinking, we tend to believe that what is personally

meaningful about the experience of joining in is shared

by everyone else. This is the ‘false consensus bias’, well-

documented in social psychology. These two facts

together explain why painful or frightening (in the

jargon, ‘dysphoric’) rituals — such as traumatic

initiations and hazing practices — lead to bonding.

Whatever each performer thinks or feels about the

experience, they all assume that the other participants

feel the same as them. The same goes for non-ritual

experiences, too: the more painful or horrifying it is, the

stronger the effect. If we are hurt in a plane crash, we

might dwell on it for years afterwards, considering how

it changed our lives and wondering why it happened,

how it could have been different and so on. Discovering

other people who share this experience can be

powerful: they seem uniquely placed to understand us in

a way that others simply can’t. In fact, we might go so

far as to say that people have no right to comment if

they haven’t been through what we have been through.

Ritual is able to work with these feelings – provoking

them as part of an intense experience of bonding with a

group.

Ritual is popularly misconstrued as an exotic, even

quirky topic — a facet of human nature that, along with

beliefs in supernatural agents and magical spells, is

little more than a curious fossil of pre-scientific culture,

doomed to eventual extinction in the wake of rational

discovery and invention. Nothing could be further from

the truth. Humans are as ritualistic today as they have

ever been.

Q.4 [11916616]

Which of the following can be inferred from the line “the

more painful or horrifying it is, the stronger the effect”?

1 Shared pain is always more profound than

individual loss is.

2 Painful experiences may lead to stronger bonding

between individuals.

3 Painful experiences are the primary cause behind

false consensus bias.

4 If one doesn’t share our pain, he/she has no right to

comment on it.

A w

Directions for questions 5-8: The passage given below

is followed by a set of six questions. Choose the most

appropriate answer to each question.

The first protest was solo: The day the exhibition,

opened an African-American artist, Parker Bright, stood

in front of it wearing a T-shirt with “Black Death

Spectacle” handwritten on its back, sometimes partly

blocking the view, sometimes engaging others in

conversation. A photograph of Mr. Bright at the Whitney

was posted on Twitter.

Objections to the painting went viral with an open letter

from Hannah Black, a British-born writer and artist who

lives in Berlin, co-signed by others, charging that the Till

image was “black subject matter,” off limits to a white

artist. Ms. Black belittled the Schutz painting as

exploiting black suffering “for profit and fun” and

demanded that it be not only removed from the

exhibition but also destroyed.

For me, as for others, the ground kept shifting with the

eruption of opinion pieces, interviews, blog and

Facebook posts, and emails with friends. The

discussion was upsetting, bracing, ultimately beneficial.

Is the censorship, much less the destruction of art,

abhorrent? Yes. Should people offended or outraged by

an artwork or an exhibition mount protests? Absolutely.

And might a museum have the foresight to frame a

possibly controversial work of art through labels or

programming? Yes, that, too. Inside the new National

Museum of African American History and Culture, Till’s

coffin occupies a sanctuary that has become a shrine.

Lonnie G. Bunch III, that museum’s founding director,

has said its placement “almost gives people a catharsis

on all of the violence that the community has

experienced over time.” Many people found themselves

in the messy middle ground, seeing both sides, grasping

for precedents.

What came to my mind are earlier works of art by those

who crossed ethnic lines in their depiction of social

trauma. “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti” (1931-32),

a series by Ben Shahn, a white Jewish artist, was a

stinging commentary on the trial of the immigrants

Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in

Massachusetts during the 1920s — a politically charged

case that mirrored issues surrounding ethnicity, class

and corruption in the justice system. In the same vein, it

was a white Jewish schoolteacher and songwriter, Abel

Meeropol, who wrote the wrenchingly beautiful “Strange

Fruit,” an anti-lynching ballad made famous by Billie

Holiday that in 1939 “tackled racial hatred head on,” as

David Margolick wrote in “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday,

Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights.” Ms.

Schutz’s painting is not the only work of art inspired by

the lynching of Till: There’s a ballad that Bob Dylan

wrote, and performed in 1962, titled “The Death of

Emmett Till,” released belatedly in 2010.

Those who call for the removal of Ms. Schutz’s painting

today seem to align themselves with black artists who

in 1997 started a letter-writing campaign against what

they considered the negative stereotypes of blacks in

the early work of Kara Walker, the African-American

artist known for her mercilessly Swiftian portrayals of

antebellum plantation life. They also appear to side with

Roman Catholics who in 1999, led by then Mayor

Rudolph W. Giuliani, protested a painting at the Brooklyn

Museum by the British artist Chris Ofili. It depicted the

Madonna and Child as black on a surface embellished

with small cutouts from pornographic magazines and a

few pieces of tennis-ball-size elephant dung, heavily

varnished and decorated with beads.

Over time, artists have periodically depicted or evoked

lynching, but the injured black body is a subject or

image that black artists and writers have increasingly

sought to protect from misuse, especially by those who

are not black. This debate flared up in 2015 when, in a

reading at Brown University, the poet and performance

artist Kenneth Goldsmith — most of whose work is

based on appropriation, sometimes of violent deaths —

read as a poem a slightly rearranged version of the

autopsy report of Michael Brown, the black 18-year-old

shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo.

Mr. Goldsmith was reviled on Twitter, accused of

exploiting this material.

For a moment, Ms. Black’s letter about the Schutz

painting created the impression that African-American

opinion on this issue was monolithic. It is not. Antwaun

Sargent posted a balanced editorial linked to a short,

blunt statement.

Q.5 [11916616]

Which of the following is clear from the passage?

1 There is a unilateral opinion among black people

that black subject matter is off limits to white artists.

2 Ms. Schutz’s painting is not the only work of art

inspired by the suicide of Till.

3 Black artists have increasingly sought to protect

the misuse of the injured black body in art.

4 Ms. Schutz’s painting was unsuccessful in its effort

to portray the death of Till in a proper context.

A w

Directions for questions 5-8: The passage given below

is followed by a set of six questions. Choose the most

appropriate answer to each question.

The first protest was solo: The day the exhibition,

opened an African-American artist, Parker Bright, stood

in front of it wearing a T-shirt with “Black Death

Spectacle” handwritten on its back, sometimes partly

blocking the view, sometimes engaging others in

conversation. A photograph of Mr. Bright at the Whitney

was posted on Twitter.

Objections to the painting went viral with an open letter

from Hannah Black, a British-born writer and artist who

lives in Berlin, co-signed by others, charging that the Till

image was “black subject matter,” off limits to a white

artist. Ms. Black belittled the Schutz painting as

exploiting black suffering “for profit and fun” and

demanded that it be not only removed from the

exhibition but also destroyed.

For me, as for others, the ground kept shifting with the

eruption of opinion pieces, interviews, blog and

Facebook posts, and emails with friends. The

discussion was upsetting, bracing, ultimately beneficial.

Is the censorship, much less the destruction of art,

abhorrent? Yes. Should people offended or outraged by

an artwork or an exhibition mount protests? Absolutely.

And might a museum have the foresight to frame a

possibly controversial work of art through labels or

programming? Yes, that, too. Inside the new National

Museum of African American History and Culture, Till’s

coffin occupies a sanctuary that has become a shrine.

Lonnie G. Bunch III, that museum’s founding director,

has said its placement “almost gives people a catharsis

on all of the violence that the community has

experienced over time.” Many people found themselves

in the messy middle ground, seeing both sides, grasping

for precedents.

What came to my mind are earlier works of art by those

who crossed ethnic lines in their depiction of social

trauma. “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti” (1931-32),

a series by Ben Shahn, a white Jewish artist, was a

stinging commentary on the trial of the immigrants

Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in

Massachusetts during the 1920s — a politically charged

case that mirrored issues surrounding ethnicity, class

and corruption in the justice system. In the same vein, it

was a white Jewish schoolteacher and songwriter, Abel

Meeropol, who wrote the wrenchingly beautiful “Strange

Fruit,” an anti-lynching ballad made famous by Billie

Holiday that in 1939 “tackled racial hatred head on,” as

David Margolick wrote in “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday,

Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights.” Ms.

Schutz’s painting is not the only work of art inspired by

the lynching of Till: There’s a ballad that Bob Dylan

wrote, and performed in 1962, titled “The Death of

Emmett Till,” released belatedly in 2010.

Those who call for the removal of Ms. Schutz’s painting

today seem to align themselves with black artists who

in 1997 started a letter-writing campaign against what

they considered the negative stereotypes of blacks in

the early work of Kara Walker, the African-American

artist known for her mercilessly Swiftian portrayals of

antebellum plantation life. They also appear to side with

Roman Catholics who in 1999, led by then Mayor

Rudolph W. Giuliani, protested a painting at the Brooklyn

Museum by the British artist Chris Ofili. It depicted the

Madonna and Child as black on a surface embellished

with small cutouts from pornographic magazines and a

few pieces of tennis-ball-size elephant dung, heavily

varnished and decorated with beads.

Over time, artists have periodically depicted or evoked

lynching, but the injured black body is a subject or

image that black artists and writers have increasingly

sought to protect from misuse, especially by those who

are not black. This debate flared up in 2015 when, in a

reading at Brown University, the poet and performance

artist Kenneth Goldsmith — most of whose work is

based on appropriation, sometimes of violent deaths —

read as a poem a slightly rearranged version of the

autopsy report of Michael Brown, the black 18-year-old

shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo.

Mr. Goldsmith was reviled on Twitter, accused of

exploiting this material.

For a moment, Ms. Black’s letter about the Schutz

painting created the impression that African-American

opinion on this issue was monolithic. It is not. Antwaun

Sargent posted a balanced editorial linked to a short,

blunt statement.

Q.6 [11916616]

The author’s point of view regarding the main issue

raised in the passage is that:

1 discussing it was beneficial, even if it was initially

uncomfortable.

2 black subject matter being off limits to white artists

is an opinion that only black artists have.

3 works of art that cross ethnic lines are wrenchingly

beautiful.

4 people offended by works of art may engage in

destruction of that art.

A w

Directions for questions 5-8: The passage given below

is followed by a set of six questions. Choose the most

appropriate answer to each question.

The first protest was solo: The day the exhibition,

opened an African-American artist, Parker Bright, stood

in front of it wearing a T-shirt with “Black Death

Spectacle” handwritten on its back, sometimes partly

blocking the view, sometimes engaging others in

conversation. A photograph of Mr. Bright at the Whitney

was posted on Twitter.

Objections to the painting went viral with an open letter

from Hannah Black, a British-born writer and artist who

lives in Berlin, co-signed by others, charging that the Till

image was “black subject matter,” off limits to a white

artist. Ms. Black belittled the Schutz painting as

exploiting black suffering “for profit and fun” and

demanded that it be not only removed from the

exhibition but also destroyed.

For me, as for others, the ground kept shifting with the

eruption of opinion pieces, interviews, blog and

Facebook posts, and emails with friends. The

discussion was upsetting, bracing, ultimately beneficial.

Is the censorship, much less the destruction of art,

abhorrent? Yes. Should people offended or outraged by

an artwork or an exhibition mount protests? Absolutely.

And might a museum have the foresight to frame a

possibly controversial work of art through labels or

programming? Yes, that, too. Inside the new National

Museum of African American History and Culture, Till’s

coffin occupies a sanctuary that has become a shrine.

Lonnie G. Bunch III, that museum’s founding director,

has said its placement “almost gives people a catharsis

on all of the violence that the community has

experienced over time.” Many people found themselves

in the messy middle ground, seeing both sides, grasping

for precedents.

What came to my mind are earlier works of art by those

who crossed ethnic lines in their depiction of social

trauma. “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti” (1931-32),

a series by Ben Shahn, a white Jewish artist, was a

stinging commentary on the trial of the immigrants

Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in

Massachusetts during the 1920s — a politically charged

case that mirrored issues surrounding ethnicity, class

and corruption in the justice system. In the same vein, it

was a white Jewish schoolteacher and songwriter, Abel

Meeropol, who wrote the wrenchingly beautiful “Strange

Fruit,” an anti-lynching ballad made famous by Billie

Holiday that in 1939 “tackled racial hatred head on,” as

David Margolick wrote in “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday,

Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights.” Ms.

Schutz’s painting is not the only work of art inspired by

the lynching of Till: There’s a ballad that Bob Dylan

wrote, and performed in 1962, titled “The Death of

Emmett Till,” released belatedly in 2010.

Those who call for the removal of Ms. Schutz’s painting

today seem to align themselves with black artists who

in 1997 started a letter-writing campaign against what

they considered the negative stereotypes of blacks in

the early work of Kara Walker, the African-American

artist known for her mercilessly Swiftian portrayals of

antebellum plantation life. They also appear to side with

Roman Catholics who in 1999, led by then Mayor

Rudolph W. Giuliani, protested a painting at the Brooklyn

Museum by the British artist Chris Ofili. It depicted the

Madonna and Child as black on a surface embellished

with small cutouts from pornographic magazines and a

few pieces of tennis-ball-size elephant dung, heavily

varnished and decorated with beads.

Over time, artists have periodically depicted or evoked

lynching, but the injured black body is a subject or

image that black artists and writers have increasingly

sought to protect from misuse, especially by those who

are not black. This debate flared up in 2015 when, in a

reading at Brown University, the poet and performance

artist Kenneth Goldsmith — most of whose work is

based on appropriation, sometimes of violent deaths —

read as a poem a slightly rearranged version of the

autopsy report of Michael Brown, the black 18-year-old

shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo.

Mr. Goldsmith was reviled on Twitter, accused of

exploiting this material.

For a moment, Ms. Black’s letter about the Schutz

painting created the impression that African-American

opinion on this issue was monolithic. It is not. Antwaun

Sargent posted a balanced editorial linked to a short,

blunt statement.

Q.7 [11916616]

It can be inferred that the statement by Antwaun

Sargent referred to in the passage most likely:

1 was in favour of lynching in general, even if it came

at the cost of injured black bodies.

2 addressed Hannah Black directly, and explained

precisely where and how she was wrong.

3 addressed Hannah Black directly, and said she had

no right over black subject matter too.

4 presented a point of view that was African-

American, but nevertheless different from that of

Hannah Black.

A w

Directions for questions 5-8: The passage given below

is followed by a set of six questions. Choose the most

appropriate answer to each question.

The first protest was solo: The day the exhibition,

opened an African-American artist, Parker Bright, stood

in front of it wearing a T-shirt with “Black Death

Spectacle” handwritten on its back, sometimes partly

blocking the view, sometimes engaging others in

conversation. A photograph of Mr. Bright at the Whitney

was posted on Twitter.

Objections to the painting went viral with an open letter

from Hannah Black, a British-born writer and artist who

lives in Berlin, co-signed by others, charging that the Till

image was “black subject matter,” off limits to a white

artist. Ms. Black belittled the Schutz painting as

exploiting black suffering “for profit and fun” and

demanded that it be not only removed from the

exhibition but also destroyed.

For me, as for others, the ground kept shifting with the

eruption of opinion pieces, interviews, blog and

Facebook posts, and emails with friends. The

discussion was upsetting, bracing, ultimately beneficial.

Is the censorship, much less the destruction of art,

abhorrent? Yes. Should people offended or outraged by

an artwork or an exhibition mount protests? Absolutely.

And might a museum have the foresight to frame a

possibly controversial work of art through labels or

programming? Yes, that, too. Inside the new National

Museum of African American History and Culture, Till’s

coffin occupies a sanctuary that has become a shrine.

Lonnie G. Bunch III, that museum’s founding director,

has said its placement “almost gives people a catharsis

on all of the violence that the community has

experienced over time.” Many people found themselves

in the messy middle ground, seeing both sides, grasping

for precedents.

What came to my mind are earlier works of art by those

who crossed ethnic lines in their depiction of social

trauma. “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti” (1931-32),

a series by Ben Shahn, a white Jewish artist, was a

stinging commentary on the trial of the immigrants

Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in

Massachusetts during the 1920s — a politically charged

case that mirrored issues surrounding ethnicity, class

and corruption in the justice system. In the same vein, it

was a white Jewish schoolteacher and songwriter, Abel

Meeropol, who wrote the wrenchingly beautiful “Strange

Fruit,” an anti-lynching ballad made famous by Billie

Holiday that in 1939 “tackled racial hatred head on,” as

David Margolick wrote in “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday,

Café Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights.” Ms.

Schutz’s painting is not the only work of art inspired by

the lynching of Till: There’s a ballad that Bob Dylan

wrote, and performed in 1962, titled “The Death of

Emmett Till,” released belatedly in 2010.

Those who call for the removal of Ms. Schutz’s painting

today seem to align themselves with black artists who

in 1997 started a letter-writing campaign against what

they considered the negative stereotypes of blacks in

the early work of Kara Walker, the African-American

artist known for her mercilessly Swiftian portrayals of

antebellum plantation life. They also appear to side with

Roman Catholics who in 1999, led by then Mayor

Rudolph W. Giuliani, protested a painting at the Brooklyn

Museum by the British artist Chris Ofili. It depicted the

Madonna and Child as black on a surface embellished

with small cutouts from pornographic magazines and a

few pieces of tennis-ball-size elephant dung, heavily

varnished and decorated with beads.

Over time, artists have periodically depicted or evoked

lynching, but the injured black body is a subject or

image that black artists and writers have increasingly

sought to protect from misuse, especially by those who

are not black. This debate flared up in 2015 when, in a

reading at Brown University, the poet and performance

artist Kenneth Goldsmith — most of whose work is

based on appropriation, sometimes of violent deaths —

read as a poem a slightly rearranged version of the

autopsy report of Michael Brown, the black 18-year-old

shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo.

Mr. Goldsmith was reviled on Twitter, accused of

exploiting this material.

For a moment, Ms. Black’s letter about the Schutz

painting created the impression that African-American

opinion on this issue was monolithic. It is not. Antwaun

Sargent posted a balanced editorial linked to a short,

blunt statement.

Q.8 [11916616]

The author introduces the protest by the African-

American artist Parker Bright in order to:

1 connect his “Black Death Spectacle” with “The

Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti” and “Strange Fruit”.

2 point out that even in today’s world Black Death is a

Spectacle that merits attention from Ms. Black’s world.

3 showcase and contrast how Black Death and

Hannah Black are similar in that they share a

nomenclatural similarity.

4 create a buildup to a slowly increasing protest

against the painting by Ms. Schutz.

A w

Directions for questions 9-12: The passage given below

is followed by a set of six questions. Choose the most

appropriate answer to each question.

Conspicuously lost in the grand theatre of geopolitics

have been the Syrian people themselves. Their

perspectives have been systematically sidelined from

conversations about the fate of the Assad regime,

Daesh, and the refugee crisis. With the liberation of

various swathes of territory from the regime, a radical

experiment in self-governance would be conducted

across the country against the backdrop of ongoing

war. The Syrian revolution is only the latest illustration

of how self-emancipation powerfully drives those to

organise from “below” to create new social institutions

that can stand independently of the existing state

machinery.

As Assad deployed the might of the state apparatuses

against protesters during the early days of the civil

uprisings, there was no unified strategy or armed

struggle in response. It was predominantly an organic

reaction to the regime’s repression. The spontaneous

nature of the protests was largely predetermined by the

absence of an effective political opposition that could

organise and mobilise society in times of unrest.

However, as the uprising spread, so did the need for

coordination among communities, resulting in the

formation of local groups to institutionalise the

revolutionary energy that was rapidly proliferating.

The motivating drive was one of self-determination, but

not within a nationalist register. Instead, all Syrians were

recognised to have the ability to determine their destiny

in the micro-political sense, rather than being

pigeonholed into an arbitrary Syrian “national identity.”

Anarchism, broadly understood, was the methodology

animating revolutionaries—one that was firmly

grounded in a set of practices rather than any

ideological illusions.

The harsh political landscape of a despotic government

forced many to become creative and exploit openings,

leading to an autonomous and decentralised mode of

organising. The slow contraction of regime authority in

pockets of the country led to municipal and regional

gaps in power, rather than wider provincial or national

spaces. A web of administrative institutions

mushroomed at the municipal levels, including majlis

madani (civil councils), majlis al-mantaqa (district

councils), mahkama (courts), and shurta madaniy (civil

police).

In Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami’s Burning

Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, a central

narrative missing from most accounts of the conflict is

offered, brimming with the voices of silenced yet

resilient Syrians under siege. The authors devote their

attention to interviews of activists, fighters, and

refugees who depict how life in the liberated areas

(those independent from both Assad and Daesh)

functioned, through self-organised local councils called

Local Coordination Committees (LCCs). Even less

known is the tremendous figure from whom much of the

ideas of autonomous governance would germinate.

Q.9 [11916616]

Which of the following can be inferred from the given

passage?

1 The earliest sites of the insurgency were in smaller

towns and cities located in impoverished regions

2 Journalists all over the world devote their attention

only to the interviews of activists, fighters and refugees

while depicting the state of the people of Syria.

3 Self-organized local councils of Syria have also

been attacked by the Assad government.

4 Some areas of the country are no longer under the

regime’s control.

A w

Directions for questions 9-12: The passage given below

is followed by a set of six questions. Choose the most

appropriate answer to each question.

Conspicuously lost in the grand theatre of geopolitics

have been the Syrian people themselves. Their

perspectives have been systematically sidelined from

conversations about the fate of the Assad regime,

Daesh, and the refugee crisis. With the liberation of

various swathes of territory from the regime, a radical

experiment in self-governance would be conducted

across the country against the backdrop of ongoing

war. The Syrian revolution is only the latest illustration

of how self-emancipation powerfully drives those to

organise from “below” to create new social institutions

that can stand independently of the existing state

machinery.

As Assad deployed the might of the state apparatuses

against protesters during the early days of the civil

uprisings, there was no unified strategy or armed

struggle in response. It was predominantly an organic

reaction to the regime’s repression. The spontaneous

nature of the protests was largely predetermined by the

absence of an effective political opposition that could

organise and mobilise society in times of unrest.

However, as the uprising spread, so did the need for

coordination among communities, resulting in the

formation of local groups to institutionalise the

revolutionary energy that was rapidly proliferating.

The motivating drive was one of self-determination, but

not within a nationalist register. Instead, all Syrians were

recognised to have the ability to determine their destiny

in the micro-political sense, rather than being

pigeonholed into an arbitrary Syrian “national identity.”

Anarchism, broadly understood, was the methodology

animating revolutionaries—one that was firmly

grounded in a set of practices rather than any

ideological illusions.

The harsh political landscape of a despotic government

forced many to become creative and exploit openings,

leading to an autonomous and decentralised mode of

organising. The slow contraction of regime authority in

pockets of the country led to municipal and regional

gaps in power, rather than wider provincial or national

spaces. A web of administrative institutions

mushroomed at the municipal levels, including majlis

madani (civil councils), majlis al-mantaqa (district

councils), mahkama (courts), and shurta madaniy (civil

police).

In Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami’s Burning

Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, a central

narrative missing from most accounts of the conflict is

offered, brimming with the voices of silenced yet

resilient Syrians under siege. The authors devote their

attention to interviews of activists, fighters, and

refugees who depict how life in the liberated areas

(those independent from both Assad and Daesh)

functioned, through self-organised local councils called

Local Coordination Committees (LCCs). Even less

known is the tremendous figure from whom much of the

ideas of autonomous governance would germinate.

Q.10 [11916616]

What is the central theme of the passage?

1 Analysing the formation of local independent

groups as a result of civilian’s reaction to the state’s

repression.

2 Showcasing the regime’s persecution of activists

and its brutal assault upon civilians.

3 Syria entering a new era with the downfall of the

Assad regime.

4 Understanding the perspectives of the Syrians who

are full of revolutionary energy.

A w

Directions for questions 9-12: The passage given below

is followed by a set of six questions. Choose the most

appropriate answer to each question.

Conspicuously lost in the grand theatre of geopolitics

have been the Syrian people themselves. Their

perspectives have been systematically sidelined from

conversations about the fate of the Assad regime,

Daesh, and the refugee crisis. With the liberation of

various swathes of territory from the regime, a radical

experiment in self-governance would be conducted

across the country against the backdrop of ongoing

war. The Syrian revolution is only the latest illustration

of how self-emancipation powerfully drives those to

organise from “below” to create new social institutions

that can stand independently of the existing state

machinery.

As Assad deployed the might of the state apparatuses

against protesters during the early days of the civil

uprisings, there was no unified strategy or armed

struggle in response. It was predominantly an organic

reaction to the regime’s repression. The spontaneous

nature of the protests was largely predetermined by the

absence of an effective political opposition that could

organise and mobilise society in times of unrest.

However, as the uprising spread, so did the need for

coordination among communities, resulting in the

formation of local groups to institutionalise the

revolutionary energy that was rapidly proliferating.

The motivating drive was one of self-determination, but

not within a nationalist register. Instead, all Syrians were

recognised to have the ability to determine their destiny

in the micro-political sense, rather than being

pigeonholed into an arbitrary Syrian “national identity.”

Anarchism, broadly understood, was the methodology

animating revolutionaries—one that was firmly

grounded in a set of practices rather than any

ideological illusions.

The harsh political landscape of a despotic government

forced many to become creative and exploit openings,

leading to an autonomous and decentralised mode of

organising. The slow contraction of regime authority in

pockets of the country led to municipal and regional

gaps in power, rather than wider provincial or national

spaces. A web of administrative institutions

mushroomed at the municipal levels, including majlis

madani (civil councils), majlis al-mantaqa (district

councils), mahkama (courts), and shurta madaniy (civil

police).

In Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami’s Burning

Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, a central

narrative missing from most accounts of the conflict is

offered, brimming with the voices of silenced yet

resilient Syrians under siege. The authors devote their

attention to interviews of activists, fighters, and

refugees who depict how life in the liberated areas

(those independent from both Assad and Daesh)

functioned, through self-organised local councils called

Local Coordination Committees (LCCs). Even less

known is the tremendous figure from whom much of the

ideas of autonomous governance would germinate.

Q.11 [11916616]

What is the reason for no unified strategy or armed

struggle in response to the Assad’s violent suppression

of the protestors?

1 Syrians starved for munitions required to take over

their government.

2 Due to the spontaneous nature of the protests,

people didn’t get time to group together.

3 These spontaneous insurrections were

decentralized and bereft of any political party

leadership.

4 There were ideological and political disagreements

within different opposition groups which led to fighting

within the opposition.

A w

Directions for questions 9-12: The passage given below

is followed by a set of six questions. Choose the most

appropriate answer to each question.

Conspicuously lost in the grand theatre of geopolitics

have been the Syrian people themselves. Their

perspectives have been systematically sidelined from

conversations about the fate of the Assad regime,

Daesh, and the refugee crisis. With the liberation of

various swathes of territory from the regime, a radical

experiment in self-governance would be conducted

across the country against the backdrop of ongoing

war. The Syrian revolution is only the latest illustration

of how self-emancipation powerfully drives those to

organise from “below” to create new social institutions

that can stand independently of the existing state

machinery.

As Assad deployed the might of the state apparatuses

against protesters during the early days of the civil

uprisings, there was no unified strategy or armed

struggle in response. It was predominantly an organic

reaction to the regime’s repression. The spontaneous

nature of the protests was largely predetermined by the

absence of an effective political opposition that could

organise and mobilise society in times of unrest.

However, as the uprising spread, so did the need for

coordination among communities, resulting in the

formation of local groups to institutionalise the

revolutionary energy that was rapidly proliferating.

The motivating drive was one of self-determination, but

not within a nationalist register. Instead, all Syrians were

recognised to have the ability to determine their destiny

in the micro-political sense, rather than being

pigeonholed into an arbitrary Syrian “national identity.”

Anarchism, broadly understood, was the methodology

animating revolutionaries—one that was firmly

grounded in a set of practices rather than any

ideological illusions.

The harsh political landscape of a despotic government

forced many to become creative and exploit openings,

leading to an autonomous and decentralised mode of

organising. The slow contraction of regime authority in

pockets of the country led to municipal and regional

gaps in power, rather than wider provincial or national

spaces. A web of administrative institutions

mushroomed at the municipal levels, including majlis

madani (civil councils), majlis al-mantaqa (district

councils), mahkama (courts), and shurta madaniy (civil

police).

In Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami’s Burning

Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, a central

narrative missing from most accounts of the conflict is

offered, brimming with the voices of silenced yet

resilient Syrians under siege. The authors devote their

attention to interviews of activists, fighters, and

refugees who depict how life in the liberated areas

(those independent from both Assad and Daesh)

functioned, through self-organised local councils called

Local Coordination Committees (LCCs). Even less

known is the tremendous figure from whom much of the

ideas of autonomous governance would germinate.

Q.12 [11916616]

Which of the following can definitely be said about the

author of the passage?

1 The author is critical of Robin Yassin-Kassab and

Leila Al-Shami’s Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution

and War.

2 The author thinks that the emergence of local self-

governing bodies is a radical change in Syria.

3 The author feels that anarchy is the right way to

gain freedom from the clutches of tyrants like Assad

and Daesh.

4 The author thinks that the i

w m w

w m m

A w

D w

w w

W m m O

D m

m w

w w

m w m

m

m

m m

m w w

w

m w

m m

m m

A w m

m

m w

m m w m

m m

m w w w

w

m m A

w w w

w

m w U

m

m V W W

w NA O W

m m m C W

w U m

U ww w w

w

m m m w

m m

w m

w m w

V m

U w

w w

w w w

G HW m

U

G m G W

U m

W w

w m

w w W m H

m

w w w

w m m

m

m m w

m U A

w C w

U m m

w w m

m w m Am

m C w

— w — N

m N m m

w

U

m

W m W ww

w w

w m w

w m

m w w

w

W H

m

A w U

mm w G

Q m w

m

U w

w

w w w mm M

C

m w m

m m

w

Q

A w w

m

A w

D w

w w

W m m O

D m

m w

w w

m w m

m

m

m m

m w w

w

m w

m m

m m

A w m

m

m w

m m w m

m m

m w w w

w

m m A

w w w

w

m w U

m

m V W W

w NA O W

m m m C W

w U m

U ww w w

w

m m m w

m m

w m

w m w

V m

U w

w w

w w w

G HW m

U

G m G W

U m

W w

w m

w w W m H

m

w w w

w m m

m

m m w

m U A

w C w

U m m

w w m

m w m Am

m C w

— w — N

m N m m

w

U

m

W m W ww

w w

w m w

w m

m w w

w

W H

m

A w U

mm w G

Q m w

m

U w

w

w w w mm M

C

m w m

m m

w

Q

W w

m m

m m

m m

m m

m m m

m m

mw w w m

A w

D w

w w

W m m O

D m

m w

w w

m w m

m

m

m m

m w w

w

m w

m m

m m

A w m

m

m w

m m w m

m m

m w w w

w

m m A

w w w

w

m w U

m

m V W W

w NA O W

m m m C W

w U m

U ww w w

w

m m m w

m m

w m

w m w

V m

U w

w w

w w w

G HW m

U

G m G W

U m

W w

w m

w w W m H

m

w w w

w m m

m

m m w

m U A

w C w

U m m

w w m

m w m Am

m C w

— w — N

m N m m

w

U

m

W m W ww

w w

w m w

w m

m w w

w

W H

m

A w U

mm w G

Q m w

m

U w

w

w w w mm M

C

m w m

m m

w

Q

A w m

m

m

w w

w

m

m w m

A w

D w

w w

W m m O

D m

m w

w w

m w m

m

m

m m

m w w

w

m w

m m

m m

A w m

m

m w

m m w m

m m

m w w w

w

m m A

w w w

w

m w U

m

m V W W

w NA O W

m m m C W

w U m

U ww w w

w

m m m w

m m

w m

w m w

V m

U w

w w

w w w

G HW m

U

G m G W

U m

W w

w m

w w W m H

m

w w w

w m m

m

m m w

m U A

w C w

U m m

w w m

m w m Am

m C w

— w — N

m N m m

w

U

m

W m W ww

w w

w m w

w m

m w w

w

W H

m

A w U

mm w G

Q m w

m

U w

w

w w w mm M

C

m w m

m m

w

Q

W m

m w

w U

m m

w m m

m

m

M

w m

A w

w m

w m

D

m

w

m m w

m

m

m m

m m W

m w m m—

w m

w m w

A w

Q

w w

mm C

D m

w

w m

U w m

m m

m w

m mm m m U m

w m m

U m

m D m

m w

U m

w

U m

m D m w

m

m

U m

D m

m w

A w

Q

m

w w

w w

A m m

P

m w m

H

w N Aw

m

m

C

M

m H

A m

m

m w m m

m

A w

w m

w m

D

m

w

w w m

m

m

w m

w

D m w w w

m m

m U A

m m

A w

Q

w w

mm C

m w

w w C m

w

N D w w H

M w

w A m

m

CC V m m

m w

m w w w m

w w w C

m C

w w w

w

m m

w w w C

w w w m

D m m

w w w

m C

A w

Q

w w

mm C

m m

m w

w w m

A

M w mm

w NA w m w

Am M

w

A

A

A m

ww

m A

ww

w m

A w

Q

m

w w

w w

W

m

P w

w

A

m m

m m

m

m

m

w

w

w

A w

w m

w m

D

m

w

C m

m m w

w

A w

m m m

O C m

m

m G w w

m m m

w w m

C m w

A w

You might also like

- FREE PTE Ebook EnglishWiseDocument12 pagesFREE PTE Ebook EnglishWiseripgodlike50% (2)

- Magical Hair - LeachDocument19 pagesMagical Hair - LeachSuranja Lakmal Perera100% (2)

- Basic Communication WorksheetDocument4 pagesBasic Communication Worksheetchelsea albarece100% (1)

- (Download Ebook) Video-Based LearningDocument101 pages(Download Ebook) Video-Based LearningredwankaaNo ratings yet

- The Science of Social Intelligence: 45 Methods to Captivate People, Make a Powerful Impression, and Subconsciously Trigger Social Status and ValueFrom EverandThe Science of Social Intelligence: 45 Methods to Captivate People, Make a Powerful Impression, and Subconsciously Trigger Social Status and ValueRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Understanding Stupidity by James F Welles PH DDocument153 pagesUnderstanding Stupidity by James F Welles PH Dmarius311100% (1)

- Introduction To Intercultural CommunicationDocument4 pagesIntroduction To Intercultural CommunicationErik HemmingNo ratings yet

- Luckmann-Common Sense, Science and The Specialization of KnowledgeDocument15 pagesLuckmann-Common Sense, Science and The Specialization of KnowledgeHéctor VeraNo ratings yet

- By Paul Henrickson, PH.DDocument6 pagesBy Paul Henrickson, PH.DPaul HenricksonNo ratings yet

- Sense - Think - Act: 200 exercises about basic human abilityFrom EverandSense - Think - Act: 200 exercises about basic human abilityNo ratings yet

- The Crowd & The Psychology of Revolution: Two Classics on Understanding the Mob Mentality and Its MotivationsFrom EverandThe Crowd & The Psychology of Revolution: Two Classics on Understanding the Mob Mentality and Its MotivationsNo ratings yet

- The CrowdDocument94 pagesThe Crowd村上杂記Murakami NotesNo ratings yet

- CH 7 Factors That Influence Communiction Draftv2Document44 pagesCH 7 Factors That Influence Communiction Draftv2Freddy Orlando MeloNo ratings yet

- Spender-Man Made Language Kapitola 5Document26 pagesSpender-Man Made Language Kapitola 5Eliana ValzuraNo ratings yet

- How Whole Brain Thinking Can Save the Future: Why Left Hemisphere Dominance Has Brought Humanity to the Brink of Disaster and How We Can Think Our Way to Peace and HealingFrom EverandHow Whole Brain Thinking Can Save the Future: Why Left Hemisphere Dominance Has Brought Humanity to the Brink of Disaster and How We Can Think Our Way to Peace and HealingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Improper Behaviour Imperative For CivilizationDocument14 pagesImproper Behaviour Imperative For CivilizationAchyut ChetanNo ratings yet

- The Third Vision: The Science of Personal TransformationFrom EverandThe Third Vision: The Science of Personal TransformationNo ratings yet

- Logic PDFDocument118 pagesLogic PDFAdhengo Beuze100% (2)

- Religion and PoliticsDocument11 pagesReligion and PoliticsMatthew100% (1)

- Cook Greuter IECDocument12 pagesCook Greuter IECAlan DawsonNo ratings yet

- Intro To OB (Lecture #1) - EnglishDocument2 pagesIntro To OB (Lecture #1) - Englishmtowne200No ratings yet

- The Stories Which Civilisation Holds As SacredDocument9 pagesThe Stories Which Civilisation Holds As SacredChris HesterNo ratings yet

- The Reillusionment: Globalization and the Extinction of the IndividualFrom EverandThe Reillusionment: Globalization and the Extinction of the IndividualNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of Human Existence - Edward O. WilsonDocument143 pagesThe Meaning of Human Existence - Edward O. WilsonTOM LUCYNo ratings yet

- Retrospect and ProspectDocument7 pagesRetrospect and ProspectLuis Achilles FurtadoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Deeper Cultural Assumptions-What Is Reality and TruthDocument7 pagesChapter 7 - Deeper Cultural Assumptions-What Is Reality and TruthmargaretmxNo ratings yet

- VARC - RC - Extrapolation (4-Apr)Document5 pagesVARC - RC - Extrapolation (4-Apr)nehanain0116No ratings yet

- Exopolitics and Integral Theory - Giorgio Piacenza CabreraDocument95 pagesExopolitics and Integral Theory - Giorgio Piacenza CabreraExopolitika MagyarországNo ratings yet

- John Dewey - The Quest For CertaintyDocument15 pagesJohn Dewey - The Quest For Certaintyalfredo_ferrari_5No ratings yet

- To Freedom: Mastering Our Tools Article by Yaron BarzilayDocument2 pagesTo Freedom: Mastering Our Tools Article by Yaron BarzilayLucas MouraNo ratings yet

- Global Mind World SituationDocument69 pagesGlobal Mind World Situationrkumar267303No ratings yet

- Hylozoics LiteratureDocument129 pagesHylozoics LiteratureSean HsuNo ratings yet

- Models, Metaphors, and Intuition: How we think, learn and communicateFrom EverandModels, Metaphors, and Intuition: How we think, learn and communicateRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (398)

- It All Was A Lie!: A Brutal Encounter with RealityFrom EverandIt All Was A Lie!: A Brutal Encounter with RealityNo ratings yet

- CO120 RhodesWeek3AssignmentDocument3 pagesCO120 RhodesWeek3AssignmentJessica RhodesNo ratings yet

- Meet Your Political Mind: The Interactions Between Instincts and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorFrom EverandMeet Your Political Mind: The Interactions Between Instincts and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorNo ratings yet

- Cultural and Social InfluencesDocument21 pagesCultural and Social Influencesbanarisali100% (1)

- Meet Your Mind Volume 1: The Interactions Between Instincts and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorFrom EverandMeet Your Mind Volume 1: The Interactions Between Instincts and Intellect and Its Impact on Human BehaviorNo ratings yet

- Rolfing Structural Integration Gravity Ida Rolf PDFDocument23 pagesRolfing Structural Integration Gravity Ida Rolf PDFsergio antonio dos santosNo ratings yet

- 4 Educated But IgnorantDocument5 pages4 Educated But IgnorantSPAHIC OMERNo ratings yet

- On Keeping Up The TensionDocument6 pagesOn Keeping Up The Tensionnelsonmugabe89No ratings yet

- Our Tribal Future: How to Channel Our Foundational Human Instincts into a Force for GoodFrom EverandOur Tribal Future: How to Channel Our Foundational Human Instincts into a Force for GoodNo ratings yet

- Pro Lo QueDocument10 pagesPro Lo QueDravid AryaNo ratings yet

- Ethics EssaysDocument3 pagesEthics Essaysparkerhemmingsen1201No ratings yet

- Finding Truths: Hidden Secrets of the Human Condition That Will Transform Your Life and The WorldFrom EverandFinding Truths: Hidden Secrets of the Human Condition That Will Transform Your Life and The WorldNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument5 pagesEssayMekka IbañezNo ratings yet

- Enculturation and AcculturationDocument15 pagesEnculturation and AcculturationAj VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Why Evolved Cognition Matters To Understanding Cultural Cognitive VariationsDocument12 pagesWhy Evolved Cognition Matters To Understanding Cultural Cognitive VariationsJenny sunNo ratings yet

- London RiotsDocument3 pagesLondon RiotsPaul BateNo ratings yet

- UNIFIED - COSMOS, LIFE, PURPOSE: Communicating with the Unified Source Field & How This Can Guide Our LivesFrom EverandUNIFIED - COSMOS, LIFE, PURPOSE: Communicating with the Unified Source Field & How This Can Guide Our LivesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Research Paper Topics SupernaturalDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Topics Supernaturalafedonkfh100% (1)

- BQ Moral Action Reason EssaysDocument52 pagesBQ Moral Action Reason Essaysfmedina491922No ratings yet

- On The Human Species: A Philosophy on Reason and the Emergence of Civilized HumanityFrom EverandOn The Human Species: A Philosophy on Reason and the Emergence of Civilized HumanityNo ratings yet

- Holiday List 2024 PDFDocument1 pageHoliday List 2024 PDFSuraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

- Soft Skill & Interpersonal Communication Organizer PDFDocument80 pagesSoft Skill & Interpersonal Communication Organizer PDFSuraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

- SQL NotesDocument37 pagesSQL NotesSuraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

- (It-704c) Data Warehousing and Data Mining (2013-14)Document6 pages(It-704c) Data Warehousing and Data Mining (2013-14)Suraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

- JobApplicationEssentials Badge20230712 28 Jw9z76Document1 pageJobApplicationEssentials Badge20230712 28 Jw9z76Suraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

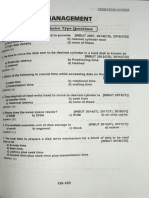

- Disk Management: Multiple Choice 1ype QuestionsDocument5 pagesDisk Management: Multiple Choice 1ype QuestionsSuraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

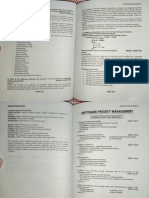

- SWE3Document12 pagesSWE3Suraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

- A State Level Webiner OnDocument3 pagesA State Level Webiner OnSuraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

- SWE2Document25 pagesSWE2Suraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 26-Aug-2022Document25 pagesAdobe Scan 26-Aug-2022Suraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 19 Oct 2021Document25 pagesAdobe Scan 19 Oct 2021Suraj DasguptaNo ratings yet

- PythonDocument8 pagesPythondesaikrish713No ratings yet

- 2023E1476-2023 Master of Environmental Engineering (Suzhou University of Science and Technology)Document14 pages2023E1476-2023 Master of Environmental Engineering (Suzhou University of Science and Technology)Marie DuoNo ratings yet

- AP English 3 Satire Essay (No Child Left Behind)Document5 pagesAP English 3 Satire Essay (No Child Left Behind)gongsterrNo ratings yet

- Rubric For Hunting For WordsDocument11 pagesRubric For Hunting For WordsPamela RegidorNo ratings yet

- Compound NounsDocument3 pagesCompound NounsLichelle BalagtasNo ratings yet

- Collective ViolenceDocument3 pagesCollective ViolenceagrawalsushmaNo ratings yet

- Mapeh Lesson Exemplar Format For Grade 1 To 6Document3 pagesMapeh Lesson Exemplar Format For Grade 1 To 6Marlon Canlas MartinezNo ratings yet

- Harshacv ProcesstrainerDocument2 pagesHarshacv Processtrainerharshameruga1996No ratings yet

- Comm 424 ProposalDocument8 pagesComm 424 Proposalapi-582248232No ratings yet

- DMM Cycle PDFDocument1 pageDMM Cycle PDFRafael MoreiraNo ratings yet

- IBPS AFO Syllabus 2Document3 pagesIBPS AFO Syllabus 2deepak palNo ratings yet

- Contrast Two or More Classification Systems For Abnormal BehaviorDocument3 pagesContrast Two or More Classification Systems For Abnormal BehaviorSerena MohajerNo ratings yet

- Final-DLL - MATH 10 - Q4 - Week 6 7 8 and 9Document11 pagesFinal-DLL - MATH 10 - Q4 - Week 6 7 8 and 9Emmz Samora CamansoNo ratings yet

- Chem1 Homo&Heterogenous RubyDocument7 pagesChem1 Homo&Heterogenous RubySheena Dominique Gerardino TimbadNo ratings yet

- Turbo MachineDocument5 pagesTurbo MachineHarish KumarNo ratings yet

- Parts of A Research Paper 5th GradeDocument7 pagesParts of A Research Paper 5th Gradexbvtmpwgf100% (1)

- Corrected-Module - CPAR - Module3 - Amboy 2Document22 pagesCorrected-Module - CPAR - Module3 - Amboy 2Colleen Vender100% (1)

- A Story To RememberDocument3 pagesA Story To RememberVen Rupert VilvarNo ratings yet

- Planning GuideDocument72 pagesPlanning GuideNur Qaisara BatrisyiaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Literature On The Impact of Student Involvement On Student Development and Learning: More Questions Than Answers?Document14 pagesAnalysis of The Literature On The Impact of Student Involvement On Student Development and Learning: More Questions Than Answers?Kevin JewelNo ratings yet

- Kami Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesKami Lesson Planapi-551692577No ratings yet

- Confusing Pairs...Document6 pagesConfusing Pairs...Nathan HudsonNo ratings yet

- Laporan Skrip Group Project MandarinDocument9 pagesLaporan Skrip Group Project MandarinFatiha IwaniNo ratings yet

- The Apple International School, Dubai: Structure of An AtomDocument3 pagesThe Apple International School, Dubai: Structure of An AtommanojNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in Remote LaboratoriesDocument13 pagesCurrent Trends in Remote LaboratoriesBazithNo ratings yet

- DPP - 3 (Thermal Properties of Matter)Document7 pagesDPP - 3 (Thermal Properties of Matter)DarkAngelNo ratings yet

- Further Edited INYANG WORK - 2018 - FINAL PUBLISHDocument63 pagesFurther Edited INYANG WORK - 2018 - FINAL PUBLISHINYANG, OduduabasiNo ratings yet