Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Exclusion Clauses and Limiting Terms

Exclusion Clauses and Limiting Terms

Uploaded by

Ibidun Tobi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views19 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views19 pagesExclusion Clauses and Limiting Terms

Exclusion Clauses and Limiting Terms

Uploaded by

Ibidun TobiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 19

EXCLUSION CLAUSES AND LIMITING TERMS

These are contractual terms that aim to limit, modify

or exclude the liability, obligations or remedies of a

party to a contract. Such clauses are usually

incorporated into a contract by a party who is at risk of

incurring unfavorable liability to another. For an

exemption clause to be valid however, there must be a

consensus between the contracting parties, and it must

not be barred due to the operation of established legal

principles regarding the validity of such clauses.

According to the court in COOPERATIVE DEVELOPMENT

BANK PLC V. MFON EKANEM & ORS [2008] 12NWLR

(PT 910) 420, parties to a contract have the freedom to

determine the terms of their contract. Such terms as

agreed by the parties determine the rights and

obligations that arises from the contact. Hence, since

parties have the right to determine their contractual

terms, they also have the power to exclude, exempt or

limit the obligations and rights arising from such terms.

Thus, where a contracting party wishes to escape from

some obligations that should have arisen from a

contract, clauses may be inserted into the contract to

either exempt or limit the party from such obligations,

and on the long run, to deprive the other party of his

remedy for the breach of such obligation in the

contract.

Most exemption clauses are usually found in standard

form contracts, the content of which are generally

fixed and determined by a single party, whereby the

other party’s freedom of contract comprises of the

decision of whether or not he chooses to accept the

fixed contractual terms. E.g contract between banks

and customers, insurers and clients etc. Generally,

exemption clauses are enforceable as they reflect an

agreement between contracting parties. However, with

regard to factors that must be considered for exclusion

clauses to be effective, the court in EKONG

ARCHIBONG V FIRST BANK OF NIGERIA PLC [2014]

LPELR-22649 (CA) held that exclusion clauses can only

operate if they are actually part of the contract that is,

adequate notice of it must be given to the other party

before the conclusion of the contract. More

specifically, the courts have formulated some

principles and requirements that guide the operation

of exclusion clauses;

(A) UNSIGNED DOCUMENTS:

Whether or not an exclusion clause contained in a

document not signed by the other party is valid

and enforceable depends on the nature of the

document. The document containing an

exemption clause must be a contractual document

that is; it must contain contractual terms as

against a receipt, ticket or voucher. For instance,

documents such as receipts, tickets voucher, etc

are by nature evidence or acknowledgement of

payments and do not qualify as contractual

documents. Thus, for a party to be bound by an

exemption clause contained in a document not

signed by him, the document must be such

containing the whole or some terms of the

contract e.g Bill of Lading, Deed of Sale, etc.

Where the unsigned document containing the

exclusion clause is not a contractual document,

the clause will be valid and deemed incorporated

into the contract if the affected party is given

reasonable notice of the clause before or at the

time of executing the contract but not after.

Otherwise, the clause will be inoperative and

unenforceable against such party.

The essence of the rule regarding unsigned

documents is to establish that an affected party is

aware or was put on notice of the clause before

executing the contract. Where the clause is

contained in an unsigned contractual document, it

is enforceable because a party cannot claim

ignorance of the document containing the term

upon which the contract is based.

In IWUOHA V NIGERIAN RAILWAY CORPORATIONS

(1997) 4 NWLR (pt.500) 419, the appellant claimed

40,000 damages against the railway corporation

for his missing goods the waybill given to the

appellant after paying for the freight contained the

following exclusion clause “All tariff are carried

subject to the Nigerian Railway Corporation Act on

Tariff Regulation made thereunder, copies of

which are available for examination free of charge

at the station. This document (i.e the waybill) is

evidence of contract as well as acknowledgement

of money paid”. The Tariff Regulation of 1981

limits the liability of the corporation to #20 per

package of missing goods and since it was two

package’s of the appellant goods that was

discovered missing, the respondent accepted

liability to the sum of #40. The court held that the

appellant was only entitled to the #40 because the

waybill is a contractual document which contains

the terms of the contract including the

incorporated conditions contained in the Railway

Corporation Act and the Tariff Regulations.

For non-contractual unsigned documents

containing exclusion clause, efforts must be made

by the party seeking to rely on such clause to bring

it to the notice of the other party before or when

the contract is executed. In chapel ton i. Barry

U.D.C (1940) 1KB 532,the plaintiff contracted to

hire two desk chairs from the defendant. The

defendant placed a notice stating the price for a

session of hire and the plaintiff paid and took two

chairs and was issued a receipt which he put in his

pocket without reading. While using one of the

chairs, it collapsed and the plaintiff sustained

bodily injury. In an action for damages against the

defendants, the defendants pleaded to be

excluded from liability because there was a

provision at the back of the ticket issued to the

plaintiff excluding them from all liabilities for any

injury or damage arising from the hire of the chair.

The court rejected this defense and held that the

defendants are liable for the injury. According to

the court, the receipt was not a contractual

document and no reasonable person would

imagine that it was anything but a receipt for the

money paid for the chairs. In addition, the receipt

was only issued after the contract had already

been executed. SEE ALSO ODENIYI V ZARD &CO

(1972)2 NWLR 34.

However, where reasonable steps is taken to alert

the adverse party of the existence of an exclusion

clause in an unsigned non-contractual document,

the court will enforce the clause. In MCQUARY V

BIG WHITE SKI RESORT (1993) BCJ NO. 2897, the

plaintiff sustained a fractured pelvis when he skied

off the edge of a ski run into a ten foot deep

concrete culvert. Although the plaintiff did not sign

a written document, the lift pass contained

comprehensive excluding terms which the plaintiff

denied to have read. The court considered the

drafting design, color of the ticket and the synage

at the resort and concluded that reasonable steps

had been taken to alert the plaintiff of the

exclusion clause. The lift ticket contained the

words “Exclusion of Liability” in bold, capital

letters printed in red and blue. The defendant also

placed a number of colored signs throughout its

property which highlighted in bold, capital letters

the same exclusion clause found on the ticket.

Upon consideration of all these factors, the court

upheld the exclusion clause. See also Argiros v

Whistler and Blackcomb mountain (2002) OJ NO.

3916; Imo Concorde Hotel v Anya (1992) 4 NWLR

(pt.234) 210.

Where such displayed notices are however placed

where adverse parties cannot easily see it before

contracting, exclusion of liability will not be

upheld. In OLLEY V MARLBOROVGH COURTS LTD

(1949) 1KB 532, a couple booked in at the

reception desk of a hotel and paid for a week’s

stay after which they went into the bedroom. On

the bedroom wall was a notice stating that the

hotel would not be liable for items stolen unless

handed in for safe custody. The wife’s fur coat was

stolen from the room. In an action against the

defendant, liability was denied on the basis of the

notice placed on the wall of the bedroom. The

court held that the exemption clause could not

avail the defendants because the contract was

executed at the reception desk and the plaintiffs

became aware of the clause after executing the

contract.

(B) SIGNED DOCUMENT: Generally, a party who

signs any contractual document in the absence of

fraud or misrepresentation, is bound by its terms

including any exemption clause it may contain.

According to the court in L’ESTRANGE V GRAUCOB

LTD (1934) 2 KB 394, where a party signs a

document which he knows affects his rights, the

party is bound by the document in the absence of

fraud or misrepresentation even though the party

may not have read or understood the document.

According to the court in MARVCO COLOUR

RESEARCH LTD V HARRIS (1982) 141 DLR, 577, an

individual cannot rely on his/her failure to read the

agreement to argue that the terms of the

agreement are not legally binding.

In BLOMBERG V BLACKCOMB SKING ENT LTD

(1992) 64 BCLR 51, the court held that a document

containing exclusion clauses, signed by the plaintiff

at the time of purchasing his ticket was sufficient

to fully exonerate the defendant from liability. In

this case, the plaintiff sustained serious injuries

after colliding with another skier at the defendant

ski resort. The plaintiff had signed a document

containing an exclusion clause before obtaining a

pass into the resort. The plaintiff argued that he

did not understand that he was signing a

document of such nature, that none on behalf of

the defendant informed him of the terms in the

document, and that he required eyeglasses for

reading and did not have his glasses with him

when he was signing the document. The court

upheld the exclusion clause.

The court in GOOD-SPEED V. TYAX MOUNTAIN

LAKE RESORT LTD [2005] BCSC 1577, recognized

some exceptions to this general rule including: non

est factum, an agreement induced by fraud or

misrepresentation, and mistakes as to the

excluding terms.

NON-EST FACTUM: literally means “not my

deed” whereby a party claims that the

document signed by him/her is fundamentally

different from what he/she intended to sign. In

other words, the document was signed by

mistake, without knowledge of its meaning. In

CHAGOURY V. ADEBAYO TAYLOR [1973] 3VILR,

532, where a party signs a document which

forms part of a contract and the document

further refers to another document which

contains exclusion clauses whether he reads

them or not unless there is fraud or

misrepresentation. In CURTIS V. CHEMICAL

CLEANING AND DYEING CO. [1951] 11CB, 805.

Curtis took her wedding dress to be dry cleaned.

She was asked to sign a receipt upon which

Curtis inquired to know why she had to sign the

receipt. She was told that the dry cleaners will

not accept certain risks and specifically

mentioned the beads and sequins on the dress

as something they could not take responsibility

for. Curtis then signed the receipt. The exclusion

clause was however very wide and covered

much more than the beads and sequins. When

Curtis went to recover her dress, the beads and

sequins were okay but there was a bad stain on

the dress. She complained and the dry cleaner

pointed to the clause she had signed. In an

action for damages, the court held that the shop

assistant had misled Curtis as to the scope of the

exclusion clause and the dry cleaner could only

rely on the clause as it was represented and not

as it was.

NOTE: With regard to the plea of non-est

factum, the adverse party must be such that

through no fault of his, is unable to have any

understanding of the purpose of the particular

document maybe as a result of blindness,

illiteracy, or some other disability which requires

the reliance on others for advice as to what is

being signed.

Secondly, the signatory must have made a

fundamental mistake as to the nature and effects

of a document being signed, or the document

must have been radically different from one

intending to be signed.

In SAUNDERS V. ANGLIA BUILDING SOCIETY [1970]

UKHL5, the plaintiff signed a document without

first informing herself of its contents. She was lied

to by her nephew’s business partner that the

documents were merely to confirm a gift of her

house to her nephew. In fact, the documents were

such that allows the nephew’s business partner to

grant a mortgage over the property in favor of

Anglia Building Society. When the business partner

defaulted on the mortgage, Anglia Building Society

claimed to foreclose and repossess the house.

Judgement was given against the plaintiff.

According to the court, the plaintiff has the burden

of demonstrating that she has not acted

negligently and the plea of NON EST FACTUM can

generally not be claimed by a person full of

capacity.

It is noteworthy that in CURTIS case, the receipt

contained a clause exempting the defendants

from all liability for damage to items signed.

Upon further inquiry by Curtis, she was told that

the defendants would not accept liability for

certain specified risks in this case, any damage

done to the beads and sequins on the dress. The

decision in that case was therefore based on the

inducement of the plaintiff to believe that the

clause only referred to the beads and sequins.

Mistake refers to an erroneous believe or

incorrect understanding of the nature or effect

of the exclusion clause at the time of signing the

document. Thus, non est factum and mistake

are of the same legal implications.

Other exceptions that restrict the scope and

effect of excluding terms and are applicable to

both signed and unsigned documents include:

a) THE CONTRA PROFERENTEM RULE – In

considering the validity of an exemption

clause, the courts resolve any doubt in favour

of an adverse party and against the person

seeking to rely on it. In other words, the

courts interpret the wordings of an exclusion

clause strictly and where there is any

ambiguity or vagueness in the way the clause

is drafted, it will be interpreted against the

party relying on it contra proferens. In

INSIGHT VACATIONS PROPERTY LTD V YOUNG

(2011) 4 CA 16, Mrs Young was travelling

around Europe with her husband in a motor

coach. While the coach was in transit, she got

up to retrieve an item from her bag in the

overhead luggage shelf. The coach braked

suddenly and she fell backward and suffered

injury. In an action for breach of an implied

term, insight vacations relied on an exclusion

clause contained in the contract stating that

where the passenger occupies a motor-coach

seat fitted with a safety belt, neither the

operators nor their agents will be liable for

any injury arising from an accident or incident,

if the safety belt is not worn at the time of

such accident or incident. The court held that

the words should be given their ordinary

meaning with the effect that the exclusion

would only apply to those time a passenger

occupies his/her seat and not where a

passenger stands up to move about the coach

to retrieve some items from the overhead

shelf.

In HOUGHTON V TRAFALGAR INSURANCE

(1954) 1QB 247, a term in a car insurance

policy excluded the insurers liability where

excess load was being carried. A car was

involved in an accident when six passengers

instead of five for which it was constructed.

The court interpreted the term “load” strictly

thereby excluding passengers.

Aside instances of ambiguity or vagueness,

the rule is also applied in cases of negligence.

An exclusion clause will not be construed to

exclude liability for negligence except the

clause expressly refers to negligence.

Similarly, where a party’s contractual liability

could arise both from negligence and another

cause of action such as breach of contract,

unless an exemption clause specifically refers

to or mentions negligence, it will not be

construed to cover negligence. According to

the court in GILLESPIE BROS LTD V BOWLES

TRANSPORT (1973)1QB 400, it is inherently

improbable that a contracting party would

intend to absolve the other party from the

consequences of that other party’s

negligence.

Thus, where a party wishes to exempt his

liability for negligence, he must specifically

ascertain that fact to the other party. In

WHITE V WARRICK (1953)2 ALL ER 1021, the

plaintiff hired a bicycle from the defendants. It

was a term of their agreement that ‘nothing in

this agreement shall render the owners liable

for any personal injuries to the riders of the

machine hired’. The plaintiff was injured when

he was thrown off the bicycle when the

defective saddle suddenly tipped over. He

brought an action for negligence in tort and

for breach of contract. It was held that the

exemption clause covered only the liability for

breach of contract (such as implied term as to

fitness for purpose etc) but not from liability

in negligence which is a tortious liability.

Even where the only type of liability possible

in a situation is negligence, it has been held

that in the absence of the express mention of

‘negligence’ in the wordings of the exemption

clause, the clause will not be interpreted to

cover negligence. In HOLLIER V RAMBLER

MOTORS(AMC) LTD (1972) 2QB 71, the

plaintiff brought his car to the defendants’

garage for repair, and it was damaged in a fire

caused by the negligence of the defendants’

servants. In an action for negligence, the

defendants relied on a clause providing that

the defendants were not responsible for any

damage caused by fire to customers’ cars on

their premises. The court held that the clause

did not protect the defendants from the

consequences of their negligence but only

operated as a warning to customers that the

defendants would not be liable if the cars

were damaged by fire not due to their

negligence.

B) THIRD PARTIES- By the doctrine of privity

of contract, a contract cannot confer any

rights or liabilities on a person who is not a

party to the contract. Thus, an exclusion

clause generally cannot protect someone who

is not a party to a contract in which it is

contained. In ADLER V DICKSON (1955) 1QB

158, the plaintiff who was a passenger on a

ship fell from the gangway of the ship. He

consequently sued the captain of the ship. The

captain sought protection under a clause

contained in the ticket for the voyage which

excludes the company’s liability for any injury

whatsoever to the person of any passenger

arising or occasioned by the negligence of the

company’s servants. The court held that the

clause only protected the company and even

if it had been extended to include the servants

of the company, it would have been

unenforceable since the servants were not

parties to the contract.

C) FUNDAMENTAL BREACH- This refers to

an event resulting from the failure of a contracting

party to perform a primary obligation under a contract

with the effect of depriving the other party of

substantially the whole benefit which it was the

intention of the parties that he should obtain from the

contract. In other words, it is a breach in consequence

of which the performance of the contract becomes

something totally different from that which the

contract contemplates. In other words, a fundamental

breach is a breach of a condition or fundamental term.

In addition to the right of an aggrieved party to

repudiate the contract and claim damages in such

instances, another legal effect is the inapplicability of

any exemption clause inserted in the contract for the

benefit of any party in breach. In other words, a party

guilty of a fundamental breach cannot avoid liability by

relying on an exemption clause no matter how

comprehensively drafted. According to the court in

Karsales ( Harrow) Ltd V Wallis (1956) 2 ALL ER 866,

exempting clauses, no matter how widely they are

expressed, only avail a party when he is carrying out

the contract in its essential respects. He is not allowed

to use them as a cover for misconduct or indifference

or enable him turn a blind eye to his obligations. They

do not avail him when he is guilty of a breach which

goes to the root of the contract. In ADEL BOSCHILLI V

ALLIED COMMERCIAL EXPORTERS LTD (1961) 1 ALL NLR

917, in a contract for the supply of cloth between a

supplier in London and a buyer in lagos, the shipped

sample was found very much inferior in quality to the

sample which formed the basis of the agreement. The

suppliers tried to rely on an exemption clause to wit ,

‘for goods not of UK origin, we cannot undertake any

guarantees or admit any claims beyond such as are

admitted by and recovered by the manufacturers’. The

court held that the clause did not avail the defendants

any protection in this instance. In SHOTAYO AND

ARUNKEGBE V NIGERIAN TECHNICAL CO (1970) 2 ALR

159, the plaintiffs who were transporters, bought a

second-hand lorry from the defendants under a hire

purchase agreement which contained a clause

excluding all warranties and conditions as to fitness or

road worthiness of the lorry. The lorry turned out to be

unfit for its work and unroadworthy. Over a period of

seven months, it broke down four times and was only

able to make three business journeys and was under

repairs the rest of the time. The plaintiffs sued for

breach of condition as to fitness for purpose and the

defendants denied liability relying on the exemption

clause. It was held that the defendants were not

entitled to protection under the exemption clause

because they had committed a fundamental breach of

the contract.

According to the court in GEORGE MITCHELL (CHESTER

HALL) LTD V FINNEY LOCK SEEDS LTD (1981) 1 LLOYD’S

REP 476, an exclusion clause could only operate in the

situation where the person relying on it was

performing the contract in the manner contemplated

by both parties as expressed in their agreement. Thus,

an exclusion clause will not excuse a non-contractual

performance that is, performance totally different

from that which the contract contemplates.

You might also like

- References - Law of Banking-1Document27 pagesReferences - Law of Banking-1Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Former President Trump's Attorney's Letter To Town of Palm BeachDocument3 pagesFormer President Trump's Attorney's Letter To Town of Palm BeachWTSP 10No ratings yet

- 20160316-Wp25124Of2005MHC-RR-PIL - RailwaysDocument4 pages20160316-Wp25124Of2005MHC-RR-PIL - RailwaysDisability Rights AllianceNo ratings yet

- Eagleridge Development Corporation vs. CameronDocument3 pagesEagleridge Development Corporation vs. CameronPaola EscobarNo ratings yet

- Exemption Clauses (Stud - Version)Document66 pagesExemption Clauses (Stud - Version)Farouk Ahmad0% (2)

- Document 1Document10 pagesDocument 1nkita MaryNo ratings yet

- 1-GDEHKL Contract Law - Terms of A ContractDocument68 pages1-GDEHKL Contract Law - Terms of A ContractsamsheungNo ratings yet

- Exclusion ClausesDocument4 pagesExclusion Clausesssewanyana256No ratings yet

- Eviddigestssec 9-25Document97 pagesEviddigestssec 9-25Carene Leanne BernardoNo ratings yet

- Exclusion Clause - Lpb201 (Law of Contract)Document9 pagesExclusion Clause - Lpb201 (Law of Contract)junry2017No ratings yet

- Exclusion ClausesDocument6 pagesExclusion ClausesalannainsanityNo ratings yet

- Terms of The ContractDocument27 pagesTerms of The ContractTsholofelo100% (1)

- EXCLUSION CLAUSESsDocument11 pagesEXCLUSION CLAUSESsnkita MaryNo ratings yet

- First Division: ChairpersonDocument166 pagesFirst Division: ChairpersonRoel PukinNo ratings yet

- 06 Allied Banking Corporation V CADocument2 pages06 Allied Banking Corporation V CAYPENo ratings yet

- Damodar Valley Corporation Vs KK Kar 12111973 SCs730026COM966732Document7 pagesDamodar Valley Corporation Vs KK Kar 12111973 SCs730026COM966732giriNo ratings yet

- Exemption or Exclusion ClauseDocument50 pagesExemption or Exclusion ClauseDebbie PhiriNo ratings yet

- Exclusion ClausesDocument16 pagesExclusion ClausesRach.ccnnNo ratings yet

- FLT Insurance Chevron: CralawDocument10 pagesFLT Insurance Chevron: CralawAngelie Gacusan BulotanoNo ratings yet

- No Claim CertificateDocument18 pagesNo Claim CertificateRinku SinghNo ratings yet

- Law Notes Vitiating FactorsDocument28 pagesLaw Notes Vitiating FactorsadeleNo ratings yet

- Exclusion ClausesDocument17 pagesExclusion ClausesMuhamad Taufik Bin Sufian100% (3)

- Eagleridge Development Corp (Civil Procedure)Document3 pagesEagleridge Development Corp (Civil Procedure)Phearl UrbinaNo ratings yet

- Case CommentDocument5 pagesCase CommenttigersnegiNo ratings yet

- Law Exemption ClauseDocument34 pagesLaw Exemption ClauseClarence Gan100% (4)

- Exclusion Clause AnswerDocument4 pagesExclusion Clause AnswerGROWNo ratings yet

- Vega v. San Carlos MillingDocument2 pagesVega v. San Carlos MillingPepper Potts50% (2)

- G.R. No. 177839 - First Lepanto-Taisho Insurance Corp. v. Chevron Phil., IncDocument9 pagesG.R. No. 177839 - First Lepanto-Taisho Insurance Corp. v. Chevron Phil., IncAmielle CanilloNo ratings yet

- First Lepanto-Taisho Insurance Corporation V Chevron, 663 SCRA 309 (2012)Document8 pagesFirst Lepanto-Taisho Insurance Corporation V Chevron, 663 SCRA 309 (2012)Shiela AdlawanNo ratings yet

- ACFrOgBucdPk4AzgOgmEMkPj2SC0LQw4jGVZHRhQHIG2qQkfk 8DfaN OOP12kA3K-lp105NivtaGou0hHXiqIR3oWuh8HkIDBa0cpOZW8jMllWDg6X92a8KJ 6uQ41g8ttVFYcjMlDCmGd3H6BODocument14 pagesACFrOgBucdPk4AzgOgmEMkPj2SC0LQw4jGVZHRhQHIG2qQkfk 8DfaN OOP12kA3K-lp105NivtaGou0hHXiqIR3oWuh8HkIDBa0cpOZW8jMllWDg6X92a8KJ 6uQ41g8ttVFYcjMlDCmGd3H6BOsaharshreddyNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 6 Week 7Document2 pagesTutorial 6 Week 7Ryan RivaldiNo ratings yet

- Dupasquier v. Ascendas (Philippines) Corp. G.R. No. 211044, 24 July 2019 FactsDocument4 pagesDupasquier v. Ascendas (Philippines) Corp. G.R. No. 211044, 24 July 2019 FactsachiNo ratings yet

- Vega Vs San Carlos Milling CoDocument9 pagesVega Vs San Carlos Milling CoDora the ExplorerNo ratings yet

- DEPOSIT - Safety Deposit BoxDocument16 pagesDEPOSIT - Safety Deposit BoxMaddison YuNo ratings yet

- Exemption Clause in KenyaDocument9 pagesExemption Clause in KenyaFRNCIS BASIS MAUGONo ratings yet

- Exemption Clauses and Discharge (Allow, Release) of Contract by DATIUS DIDACEDocument54 pagesExemption Clauses and Discharge (Allow, Release) of Contract by DATIUS DIDACEDATIUS DIDACE(Amicus Curiae)⚖️No ratings yet

- Ceniza Last DayDocument7 pagesCeniza Last DayJumel John H. ValeroNo ratings yet

- Gilat Satellite Networks, Ltd. v. UCPB, G.R. No. 189563, April 7, 2014Document8 pagesGilat Satellite Networks, Ltd. v. UCPB, G.R. No. 189563, April 7, 2014Ramil GarciaNo ratings yet

- Vega vs. San Carlos Milling Co PDFDocument11 pagesVega vs. San Carlos Milling Co PDFMelfay ErminoNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CHP 5 - Refund - Guarantees - 5 - Aids - To - Construction - of - Demand - Instruments - and - GuaranteesDocument11 pagesCHP 5 - Refund - Guarantees - 5 - Aids - To - Construction - of - Demand - Instruments - and - GuaranteesBikram ReflectionsNo ratings yet

- No 27 Exclusion ClauseDocument6 pagesNo 27 Exclusion Clauseproukaiya7754No ratings yet

- The Parole Evidence Rule - Docx1Document7 pagesThe Parole Evidence Rule - Docx1rulenso passmoreNo ratings yet

- Sing, Jr. V FEB LeasingDocument6 pagesSing, Jr. V FEB LeasingErnie GultianoNo ratings yet

- Guangdong Chinese Co - LTD Vs Damco Logistics UgandaDocument14 pagesGuangdong Chinese Co - LTD Vs Damco Logistics UgandaKellyNo ratings yet

- JP Handbook - 2Document39 pagesJP Handbook - 2ACBNo ratings yet

- FIRST LEPANTO-TAISHO INSURANCE CORPORATION vs. CHEVRON Phil Case Digest 2012 (Surety)Document2 pagesFIRST LEPANTO-TAISHO INSURANCE CORPORATION vs. CHEVRON Phil Case Digest 2012 (Surety)Sam LeynesNo ratings yet

- CA Agro-Industrial Development Corp Vs CADocument3 pagesCA Agro-Industrial Development Corp Vs CAJoona Kis-ingNo ratings yet

- 2001 Construction of Terms of ContractDocument227 pages2001 Construction of Terms of ContractElisabeth Chang0% (2)

- Keihin-Everett Forwarding Co., Inc. vs. Tokio Marine Malayan Insurance Co., Inc. and Sunfreight Forwarders & Customs Brokerage, IncDocument4 pagesKeihin-Everett Forwarding Co., Inc. vs. Tokio Marine Malayan Insurance Co., Inc. and Sunfreight Forwarders & Customs Brokerage, IncNeon True BeldiaNo ratings yet

- Terms and RepresentationDocument6 pagesTerms and Representationnicole camnasioNo ratings yet

- Gilat Satellite vs. United CoconutDocument4 pagesGilat Satellite vs. United CoconutZei MallowsNo ratings yet

- 2004 ZWHHC 12Document7 pages2004 ZWHHC 12Clayton MutsenekiNo ratings yet

- Bharati Knitting Co.Document2 pagesBharati Knitting Co.mafer56303No ratings yet

- TABL1710 AssignmentDocument7 pagesTABL1710 AssignmentAsdsa Asdasd100% (1)

- Exemption ClauseDocument23 pagesExemption Clausebba22090030No ratings yet

- Ong Lim Sing Jr. vs. FEB Leasing Finance Corp 524 SCRA 333 GR 168115 June 8 2007Document8 pagesOng Lim Sing Jr. vs. FEB Leasing Finance Corp 524 SCRA 333 GR 168115 June 8 2007Rhodail Andrew CastroNo ratings yet

- 2023 S C M R 1390Document4 pages2023 S C M R 1390Bruce KhanNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondent: Third DivisionDocument9 pagesPetitioner Vs Vs Respondent: Third DivisionKristine MagbojosNo ratings yet

- Contract II Law 486 TutorialDocument2 pagesContract II Law 486 TutorialAimi IryaniNo ratings yet

- Transfield Philippines VS Luzon Hydro CorpDocument1 pageTransfield Philippines VS Luzon Hydro CorpchaNo ratings yet

- Soccer (Football) Contracts: An Introduction to Player Contracts (Clubs & Agents) and Contract Law: Volume 2From EverandSoccer (Football) Contracts: An Introduction to Player Contracts (Clubs & Agents) and Contract Law: Volume 2No ratings yet

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Group 4Document5 pagesGroup 4Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- GST 203 Question and AnswerDocument7 pagesGST 203 Question and AnswerIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- In Nigeria IncidentsDocument8 pagesIn Nigeria IncidentsIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Labour Law AssDocument7 pagesLabour Law AssIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Group 6 - Statutory Marriage - 1Document12 pagesGroup 6 - Statutory Marriage - 1Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document8 pagesAssignment 1Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- GST 104 (Incomplete)Document26 pagesGST 104 (Incomplete)Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Proposals For Further Alterations of The 1999 Constitution (As Amended) Presented by The Sug 15th Judicial Council of EsutDocument8 pagesProposals For Further Alterations of The 1999 Constitution (As Amended) Presented by The Sug 15th Judicial Council of EsutIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- LPT203 20202021Document2 pagesLPT203 20202021Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

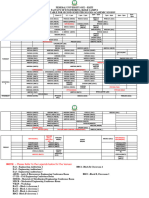

- 2nd Semester LECTURE TIMETABLE - ENGINEERINGDocument2 pages2nd Semester LECTURE TIMETABLE - ENGINEERINGIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Defence of Mistake SlideDocument15 pagesDefence of Mistake SlideBarr A. A KolawoleNo ratings yet

- Constitution Group WorkDocument14 pagesConstitution Group WorkIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Impact of The Land Use Act On Customary Land Tenure in NigeriaDocument3 pagesImpact of The Land Use Act On Customary Land Tenure in NigeriaIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Jil 201 PDocument6 pagesJil 201 PIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Phi 102 - Introduction To Philosophy 2Document4 pagesPhi 102 - Introduction To Philosophy 2Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Trusts MR FeyiDocument21 pagesTrusts MR FeyiIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law AssignmentDocument6 pagesCommercial Law AssignmentIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Group 7 Family Law.Document9 pagesGroup 7 Family Law.Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- GROUP C PresentationDocument19 pagesGROUP C PresentationIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Commercial Law - Lecture NotesDocument2 pagesCommercial Law - Lecture NotesIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Precious 1Document5 pagesPrecious 1Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- JIL 201 ZuluDocument5 pagesJIL 201 ZuluIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- FACULTY OF LAW PAST QUESTIONS 2019 2020 Till Date. (Compiled by Ola of Canada)Document12 pagesFACULTY OF LAW PAST QUESTIONS 2019 2020 Till Date. (Compiled by Ola of Canada)Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Law Past Questions 2019 2020 Till Date. (Compiled by Ola of Canada)Document44 pagesFaculty of Law Past Questions 2019 2020 Till Date. (Compiled by Ola of Canada)Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Google Law102 NoteDocument47 pagesGoogle Law102 NoteIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Remedies For Unlawful DismissalDocument20 pagesRemedies For Unlawful DismissalIbidun TobiNo ratings yet

- LPT 311Document4 pagesLPT 311Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Law of Banking Garnishing - 1Document9 pagesLaw of Banking Garnishing - 1Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- LPT 311 Group 7Document4 pagesLPT 311 Group 7Ibidun TobiNo ratings yet

- Victorias Secret Case StudyDocument9 pagesVictorias Secret Case StudyGYEM LHAMNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Company Accounting Australia New Zealand 5th Edition Jubb Test Bank PDFDocument11 pagesDwnload Full Company Accounting Australia New Zealand 5th Edition Jubb Test Bank PDFnevahonyumptewa683100% (20)

- Introduction To Computer EthicsDocument4 pagesIntroduction To Computer Ethicsnavneet_prakashNo ratings yet

- Arnado Vs Adaza (Full Text)Document4 pagesArnado Vs Adaza (Full Text)Anonymous kDxt5UNo ratings yet

- NATRES ReviewerDocument19 pagesNATRES ReviewerAndrea IvanneNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 - Accounting For Partnerships and Limited Liability CompaniesDocument46 pagesChapter 12 - Accounting For Partnerships and Limited Liability Companiesanywhere1906No ratings yet

- National Power Corporation v. Maruhom (G.R.No. 183297)Document1 pageNational Power Corporation v. Maruhom (G.R.No. 183297)JP Murao IIINo ratings yet

- Statement of Claim To The Defendant: Sheilade Santos'TDocument16 pagesStatement of Claim To The Defendant: Sheilade Santos'TJosh WingroveNo ratings yet

- Quantum Securities PVT - LTD Vs The Director DirectorateDocument57 pagesQuantum Securities PVT - LTD Vs The Director DirectoratePGurusNo ratings yet

- Tender and Auctions Law No. 8 of 1976Document20 pagesTender and Auctions Law No. 8 of 1976londoncourseNo ratings yet

- Right To Constitutional Remedies: Article-32Document22 pagesRight To Constitutional Remedies: Article-32Dolphin100% (1)

- Time-Bound Home Exam-2020: Purbanchal UniversityDocument2 pagesTime-Bound Home Exam-2020: Purbanchal UniversitybikramNo ratings yet

- Student HandbookDocument12 pagesStudent HandbookGogo Soriano100% (1)

- Sponsored By: HON. RONALD E. FLORES, M.DDocument4 pagesSponsored By: HON. RONALD E. FLORES, M.DMiamor NatividadNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of DamageDocument1 pageAffidavit of DamageblossomNo ratings yet

- SAHRC Final Report, SU Language Investigation - 14 March 2023Document42 pagesSAHRC Final Report, SU Language Investigation - 14 March 2023Mmangaliso KhumaloNo ratings yet

- Book 7Document777 pagesBook 7Riya TayalNo ratings yet

- Form No. 143 CONTRACT OF LEGAL SERVICESDocument2 pagesForm No. 143 CONTRACT OF LEGAL SERVICESKristianne SipinNo ratings yet

- Resident Marine Mammals of Protected Seascape Tanon Strait, Et Al. v. Secretary Angelo ReyesDocument19 pagesResident Marine Mammals of Protected Seascape Tanon Strait, Et Al. v. Secretary Angelo ReyesDenise CruzNo ratings yet

- Alliedbank Tirona Filestate VitangcolDocument4 pagesAlliedbank Tirona Filestate VitangcolbubblingbrookNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines v. Ronnie LibriasDocument3 pagesPeople of The Philippines v. Ronnie LibriasWarlie Zambales DiazNo ratings yet

- Right of Children To Free and Compulsory Education ActDocument11 pagesRight of Children To Free and Compulsory Education Actluxsoap95No ratings yet

- Rafael Usatorres and Lidia Usatorres, His Wife v. Marina Mercante Nicaraguenses, S.A. D/B/A Mamenic Line, A Foreign Corporation, 768 F.2d 1285, 11th Cir. (1985)Document4 pagesRafael Usatorres and Lidia Usatorres, His Wife v. Marina Mercante Nicaraguenses, S.A. D/B/A Mamenic Line, A Foreign Corporation, 768 F.2d 1285, 11th Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- REGALADODocument16 pagesREGALADOIrish AlonzoNo ratings yet

- Zaragosa Vs CADocument2 pagesZaragosa Vs CAJaysonNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines Vs Erick MontierroDocument3 pagesPeople of The Philippines Vs Erick Montierromelrene jalmanzarNo ratings yet

- Amity Intra 2012 PetitionerDocument19 pagesAmity Intra 2012 PetitionerSimar Singh50% (2)

- Florida LLC Formation FormDocument5 pagesFlorida LLC Formation FormJuanFer Alvarez100% (1)