Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Howard 2009

Howard 2009

Uploaded by

Innoj MacoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Nursing Ethics and Jurisprudence 1Document17 pagesNursing Ethics and Jurisprudence 1dmsapostol100% (2)

- AMEE Guide No. 4 Effective Continuing Education - The CRISIS CriteriaDocument16 pagesAMEE Guide No. 4 Effective Continuing Education - The CRISIS CriteriaaungNo ratings yet

- (Ana Smith Iltis) Research Ethics (Routledge Annal (BookFi)Document192 pages(Ana Smith Iltis) Research Ethics (Routledge Annal (BookFi)Zaneta DivjakoskaNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1: Quarter 3 - Module 2: Characteristics, Processes and Ethics of ResearchDocument32 pagesPractical Research 1: Quarter 3 - Module 2: Characteristics, Processes and Ethics of ResearchVINCENT BIALEN80% (30)

- Obe PDFDocument6 pagesObe PDFjaycee_evangelistaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Compacting: An Easy Start to Differentiating for High Potential StudentsFrom EverandCurriculum Compacting: An Easy Start to Differentiating for High Potential StudentsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Graduating European Dentist: Contemporaneous Methods of Teaching, Learning and Assessment in Dental Undergraduate EducationDocument8 pagesThe Graduating European Dentist: Contemporaneous Methods of Teaching, Learning and Assessment in Dental Undergraduate Educationalvin fauziyahNo ratings yet

- Eur J Dental Education - 2017 - Field - The Graduating European Dentist A New Undergraduate Curriculum FrameworkDocument9 pagesEur J Dental Education - 2017 - Field - The Graduating European Dentist A New Undergraduate Curriculum FrameworkHernández Becerra Ivanna PaolaNo ratings yet

- 2 Eur J Dental Education - 2008 - Oliver - Curriculum Structure Principles and StrategyDocument11 pages2 Eur J Dental Education - 2008 - Oliver - Curriculum Structure Principles and StrategyRiris MarisaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Undergraduate Dental Education Curriculum (BDS)Document248 pagesGuidelines For Undergraduate Dental Education Curriculum (BDS)aamnashah25100% (1)

- Problem-Based Learning: An Interdisciplinary Approach in Clinical TeachingDocument6 pagesProblem-Based Learning: An Interdisciplinary Approach in Clinical TeachingArdianNo ratings yet

- Vertical and Horizontal Integration of K PDFDocument6 pagesVertical and Horizontal Integration of K PDFTrường Nguyễn HuyNo ratings yet

- The Changing Face of Dental Education: The Impact of PBL: Educational MethodologiesDocument16 pagesThe Changing Face of Dental Education: The Impact of PBL: Educational MethodologiesDr. Erwin HandokoNo ratings yet

- Edu623 Designing Learning Environments Final Project Eschlegel May 01-2016Document19 pagesEdu623 Designing Learning Environments Final Project Eschlegel May 01-2016api-317109664No ratings yet

- A Model For Easily Incorporating Team-Based Learning Into Nursing EducationDocument16 pagesA Model For Easily Incorporating Team-Based Learning Into Nursing EducationMuhammad Wahyu NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Instituto Nacional de Salud Pu Blica: Innovations in Graduate Public Health Education: TheDocument4 pagesInstituto Nacional de Salud Pu Blica: Innovations in Graduate Public Health Education: TheForce MapuNo ratings yet

- The Challenge of Change: Introducing Flexible Learning Into A Traditional Medical and Health Sciences FacultyDocument9 pagesThe Challenge of Change: Introducing Flexible Learning Into A Traditional Medical and Health Sciences FacultyAnonpcNo ratings yet

- Application of Theories Principles and Models of Curriculum Munna and Kalam 2021Document7 pagesApplication of Theories Principles and Models of Curriculum Munna and Kalam 2021Vaughan LeaworthyNo ratings yet

- Ar HeaDocument48 pagesAr HeaAneelaNo ratings yet

- Physical Sciences: Principles of Inclusive Curriculum DesignDocument5 pagesPhysical Sciences: Principles of Inclusive Curriculum DesignIjNo ratings yet

- Innovation in ELTDocument4 pagesInnovation in ELTHà Đặng Nguyễn NgânNo ratings yet

- Curricullum - Models - Black FontsDocument50 pagesCurricullum - Models - Black FontsAnas khanNo ratings yet

- Educational Summary Report 10454Document6 pagesEducational Summary Report 10454kman0722No ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6105 Assessment 4 Assessment Strategies and Complete Course PlanDocument12 pagesNURS FPX 6105 Assessment 4 Assessment Strategies and Complete Course PlanEmma WatsonNo ratings yet

- Ect 212 Curriculum ImplementationDocument81 pagesEct 212 Curriculum Implementationaroridouglas880No ratings yet

- 12 Tips para Renovación CurricularDocument8 pages12 Tips para Renovación CurricularNAYITA_LUCERONo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development in Nursing Education. Where Is The Pathway?Document6 pagesCurriculum Development in Nursing Education. Where Is The Pathway?IOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Learning Teaching - Learning MethodsDocument55 pagesFacilitating Learning Teaching - Learning MethodsIeda RahmanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1807593222001119 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1807593222001119 MainNadiraNo ratings yet

- Learning Outcomes and Instructional ObjectivesDocument6 pagesLearning Outcomes and Instructional Objectivesvinoth_2610100% (1)

- Modern Techniques of TeachingDocument16 pagesModern Techniques of TeachingVaidya Omprakash NarayanNo ratings yet

- AdvocacyTraining Web Version FinalDocument16 pagesAdvocacyTraining Web Version FinalEmanNo ratings yet

- Salado MAEPM COMPRE EXAM IN CURDEVDocument3 pagesSalado MAEPM COMPRE EXAM IN CURDEVRovie SaladoNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument14 pagesResearch ProposalRaki' Tobias JonesNo ratings yet

- Curric Instruct Desgn-Assgn 1Document14 pagesCurric Instruct Desgn-Assgn 1api-630481673No ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document61 pagesChapter 10Manar ShamielhNo ratings yet

- Combining Chalk Talk With Powerpoint To Increase In-Class Student EngagementDocument13 pagesCombining Chalk Talk With Powerpoint To Increase In-Class Student EngagementJuan Augusto Fernández TarazonaNo ratings yet

- Jdenteduc 2010 74 464 471Document8 pagesJdenteduc 2010 74 464 471YuniarNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Preparedness and Practice Management Skills of Graduating Dental Students Entering The Work ForceDocument8 pagesResearch Article: Preparedness and Practice Management Skills of Graduating Dental Students Entering The Work ForceNurul HusnaNo ratings yet

- MELCs WalkthroughDocument23 pagesMELCs WalkthroughallanrnmanalotoNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development Thesis PDFDocument7 pagesCurriculum Development Thesis PDFaflpaftaofqtoa100% (2)

- Staff Support in Continuing Professional DevelopmentDocument6 pagesStaff Support in Continuing Professional DevelopmentAmealyena AdiNo ratings yet

- Conference Paper No. 35: Curriculum Redevelopment: Stakeholders Sharing The Decision MakingDocument18 pagesConference Paper No. 35: Curriculum Redevelopment: Stakeholders Sharing The Decision MakingWallacyyyNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Studies EssayDocument14 pagesCurriculum Studies EssayDaiva Stalnionyte100% (1)

- Poster Writing To CheckDocument10 pagesPoster Writing To Checklaetitiarousselin4No ratings yet

- SamihussDocument7 pagesSamihussNader ElbokleNo ratings yet

- Towards A Theoretical Framework For Curriculum Development in Health Professional EducationDocument14 pagesTowards A Theoretical Framework For Curriculum Development in Health Professional EducationNgọc Linh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Curriculum & Course DesignDocument4 pagesCurriculum & Course DesignGhulam MujtabaNo ratings yet

- Assigment CurriculumDocument3 pagesAssigment CurriculumJoseph Elvinio PerrineNo ratings yet

- The Compromised Most Essential Learning Competencies: An Qualitative InquiryDocument11 pagesThe Compromised Most Essential Learning Competencies: An Qualitative InquiryPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- ScienceDirect Citations 1715638522749Document15 pagesScienceDirect Citations 1715638522749luis.velasquezNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument25 pagesContent ServersyaNo ratings yet

- Assessment For Learning - An Introduction To The ESCAPE ProjectDocument11 pagesAssessment For Learning - An Introduction To The ESCAPE ProjectYuslaini YunusNo ratings yet

- Henzi Etal (2006) - Perspectives Dental Students About Clinical EducationDocument17 pagesHenzi Etal (2006) - Perspectives Dental Students About Clinical EducationMiguel AraizaNo ratings yet

- Yiu 2011Document10 pagesYiu 2011Chris MartinNo ratings yet

- SLACDocument25 pagesSLACWinnie Poli100% (2)

- Rosal Hubilla y Carillo Vs Case DigestDocument17 pagesRosal Hubilla y Carillo Vs Case DigestbaimonaNo ratings yet

- Latest Research Docx Teshale Wirh Cfwork - For MergeDocument23 pagesLatest Research Docx Teshale Wirh Cfwork - For MergeTeshale DuressaNo ratings yet

- Supporting Academic Development To Enhance The Student ExperienceDocument12 pagesSupporting Academic Development To Enhance The Student ExperienceHazel Owen100% (1)

- The Schoolwide Enrichment Model in Science: A Hands-On Approach for Engaging Young ScientistsFrom EverandThe Schoolwide Enrichment Model in Science: A Hands-On Approach for Engaging Young ScientistsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Embedding Equality and Diversity into the Curriculum – a literature reviewFrom EverandEmbedding Equality and Diversity into the Curriculum – a literature reviewNo ratings yet

- Medical Education in Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine: Advanced Concepts and StrategiesFrom EverandMedical Education in Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine: Advanced Concepts and StrategiesPatricia A. KritekNo ratings yet

- Using the National Gifted Education Standards for Pre-KGrade 12 Professional DevelopmentFrom EverandUsing the National Gifted Education Standards for Pre-KGrade 12 Professional DevelopmentRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (8)

- NURS FPX 5005 Assessment 1 Protecting Human Research ParticipantsDocument4 pagesNURS FPX 5005 Assessment 1 Protecting Human Research ParticipantsEmma WatsonNo ratings yet

- Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar Lie, Franklin Miller, David Wendler - The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics (2008)Document848 pagesEzekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar Lie, Franklin Miller, David Wendler - The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics (2008)Dóri PappNo ratings yet

- What Is Research Ethics?Document7 pagesWhat Is Research Ethics?Nadie Lrd100% (1)

- Biomedical EngineeringDocument5 pagesBiomedical EngineeringFranch Maverick Arellano Lorilla100% (1)

- Syllabus Soc 616 Spring 08 SillsDocument18 pagesSyllabus Soc 616 Spring 08 SillsStephen SillsNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in Conducting SIPDocument60 pagesEthical Issues in Conducting SIPMavrichk100% (1)

- Critical Thinking in Clinical ResearchDocument491 pagesCritical Thinking in Clinical ResearchGustavo AndradeNo ratings yet

- 2022 October - Vol 37, No. 10Document12 pages2022 October - Vol 37, No. 10S. FelixNo ratings yet

- Becoming Widely Available Associated Press Story External Icon Concluded PDF Iconexternal IconDocument5 pagesBecoming Widely Available Associated Press Story External Icon Concluded PDF Iconexternal IconmattyNo ratings yet

- Module 5 PEDocument28 pagesModule 5 PEGauri GhuleNo ratings yet

- Research International RulesDocument41 pagesResearch International RulesEinstein Claus Balce Dagle100% (1)

- Thesis Statement Animal TestingDocument8 pagesThesis Statement Animal Testingafcmwheic100% (2)

- The Ethical Context of ResearchDocument9 pagesThe Ethical Context of ResearchArianne FarnazoNo ratings yet

- 2019-03-19 - MoH GSR 227 - New Drugs and Clinical Trial Approval Regulations 2019-147-264Document118 pages2019-03-19 - MoH GSR 227 - New Drugs and Clinical Trial Approval Regulations 2019-147-264go downNo ratings yet

- Ethics in ResearchDocument13 pagesEthics in ResearchCarissa De Luzuriaga-BalariaNo ratings yet

- What Makes Clinical Research EthicalDocument12 pagesWhat Makes Clinical Research EthicalMagda VillarrealNo ratings yet

- Principles of Ethics in Clinical Trials-Prof. Dr. Dr. Rianto Setiabudy, SPFKDocument23 pagesPrinciples of Ethics in Clinical Trials-Prof. Dr. Dr. Rianto Setiabudy, SPFKJoko WinarnoNo ratings yet

- POPIA Code of Conduct For ResearchDocument12 pagesPOPIA Code of Conduct For ResearchKayla RobinsonNo ratings yet

- UNICEF Procedure On Ethics in Evidence Generation 092015Document23 pagesUNICEF Procedure On Ethics in Evidence Generation 092015Panagiotis StathopoulosNo ratings yet

- ICAST Combined Manuals V3Document46 pagesICAST Combined Manuals V3MazlinaNo ratings yet

- HealthSystemResearch DevelopmentDesignsandMethodsDocument6 pagesHealthSystemResearch DevelopmentDesignsandMethodsSani BaniaNo ratings yet

- Module 1. Lesson2Document18 pagesModule 1. Lesson2Titser G.No ratings yet

- Electronic Torture - JeffPolachek - Study of Bio Ethical Issues - Mind Control Victim TestimonyDocument14 pagesElectronic Torture - JeffPolachek - Study of Bio Ethical Issues - Mind Control Victim Testimonystop-organized-crimeNo ratings yet

- SAS - Session-26-Research 1Document5 pagesSAS - Session-26-Research 1ella retizaNo ratings yet

- Conduct & Public Disclosure of Human Suject Research Policy POL-GSKF-408Document10 pagesConduct & Public Disclosure of Human Suject Research Policy POL-GSKF-408ouñateNo ratings yet

- Online IRB Certification NIH Drug Lit AnswersDocument5 pagesOnline IRB Certification NIH Drug Lit AnswersITisNeil67% (3)

- Isef Rules and GuidelinesDocument16 pagesIsef Rules and GuidelinesAia Mie Cornel CometaNo ratings yet

Howard 2009

Howard 2009

Uploaded by

Innoj MacoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Howard 2009

Howard 2009

Uploaded by

Innoj MacoCopyright:

Available Formats

An Integrated Curriculum: Evolution,

Evaluation, and Future Direction

Katherine M. Howard, Ph.D.; Tanis Stewart, Ph.D.; Wendy Woodall, D.D.S.;

Karl Kingsley, Ph.D.; Marcia Ditmyer, Ph.D.

Abstract: The topic of curriculum reform has received an enormous amount of attention in the field of dental education. While re-

cently established dental schools benefit from the evolution of curriculum change and innovation in constructing their new curri-

cula, these advantages can become lost if the curriculum is not assessed to ascertain the degree to which the curriculum accurate-

ly reflects the initial intended goals. The purpose of this educational research project was to evaluate a dental school curriculum

to determine the extent of vertical and horizontal integration originally intended. After a faculty retreat that presented a historical

perspective and prevalent concepts of the definitions of an integrated curriculum, a survey instrument was distributed to all course

directors asking them to assign each of their courses to one of ten established models of integration. Analysis of the survey results

allowed the mapping of each of the eighty-four courses to four themes of integration. Chi-square analysis demonstrated courses

were distributed in a classic bell-shaped curve along the integration continuum. Dental school year 4 courses mapped to the high-

est levels of integration, while no courses were assigned to the lowest level (fragment or silo model). All courses were found to

have at least some level of integration. More than half (n=43) were found to be both horizontally and vertically integrated.

Dr. Howard is Assistant Professor of Biomedical Sciences; Dr. Stewart is Director of Information Technology; Dr. Woodall is

Assistant Professor of Clinical Sciences; Dr. Kingsley is Assistant Professor of Biomedical Sciences; and Dr. Ditmyer is Assistant

Professor of Professional Studies—all at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, School of Dental Medicine. Direct correspondence

and requests for reprints to Dr. Katherine M. Howard, School of Dental Medicine, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 1001 Shadow

Lane, MS 7410, Las Vegas, NV 89106-4124; 702-774-2630 phone; 702-774-2721 fax; katherine.howard@unlv.edu.

Key words: integration, curriculum reform, dental education, curriculum evaluation

Submitted for publication 1/16/09; accepted 4/3/09

I

n 1995, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) docu- meet the oral health needs of the public throughout

mented numerous challenges to dental education, the twenty-first century.

citing curricula that are often fragmented, out- Under the auspices of the ADEA CCI, the

dated, crowded with redundant material, and delivered former Competencies for the New Dentist were

in “disciplinary silos.”1 In addition, most traditional updated, now under the name “Competencies for

dental curricula were found to be bound to conven- the New General Dentist.”3 The new competencies,

tional pedagogical methods. In response to this report, in turn, are leading to the development of founda-

various calls for curriculum and pedagogical change in tion knowledge guidelines to be used, among other

dental education have been made, with the momentum things, to play a part in test construction of Part I of

for change accelerating over the past several years. The the National Board Dental Examination (NBDE);

theme of the 85th American Dental Education Associa- initiation by the Commission on Dental Accreditation

tion (ADEA) Annual Session in 2008, for example, of its Standards for Predoctoral Dental Education;

was “Curricular Change: It’s Time,” which included and introduction of interdisciplinary questions into

a focus on curriculum reform to meet the educational Part II of the NBDE.

needs of the new millennial learner. Curriculum reform includes, but is not limited

Attention to curriculum reform has been to, topics such as revising competencies, implement-

a cumulative result of a number of issues facing ing problem- or case-based learning, and exploring

dental education, and, in 2005, the ADEA Board of alternative methods for delivering education mate-

Directors appointed an oversight committee—the rial across generations—from the Silent Generation

Commission on Change and Innovation in Dental (born in 1922–41) to the baby boomers (1942–61) to

Education (ADEA CCI)—to foster discussion and Generation X (1962–81) to the Millennials (1982 to

provide leadership for implementing changes in den- the present).2 As a component of curriculum reform,

tal education.2 The establishment of the commission curriculum integration enables learners to recognize

was intended to provide a means for collaboration how diverse concepts and/or processes are inter-

on innovative change in dental education so that related.4 This concept has received much attention

dentists entering the profession are competent to across the health sciences.5-9

962 Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 73, Number 8

Many researchers concur that curriculum individual models that portray various fundamental

integration through use of problem- or case-based aspects of integration. The ten are fragmented, con-

approaches increases the quality of instruction, im- nected, nested, sequenced, shared, threaded, webbed,

proves cohesiveness in sequencing of four-year pro- integrated, networked, and immersed models. The

grams, enhances communication of faculty by work- operational definition for each of these models ap-

ing together on new curricula, and invigorates the pears in Table 1.

learning process by developing critical thinking skills It is hoped that dental school curricula inher-

in students.8,10 This evidence has been one of the pri- ently incorporate a multiple-discipline theme leading

mary motivations for using technology in education to one common goal: to graduate knowledgeable and

that supports and enhances learning by facilitating competent dentists. This natural or innate level of

integration within and across the disciplines. These integration, however, can be greatly improved upon.

methods of integration provide new and improved Once clearly understood, utilizing these themes

tools for students, which may promote critical think- and corresponding models or methods to their best

ing and foster a deeper understanding of the material. possible fit within a particular school or program

One additional effect of these newer methods may be may help administrators and educators create ver-

their synergistic effects, allowing curricula to be more satile, dynamic, and comprehensive curricula. The

easily adapted to changing technology and newer or University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) School

evolving methods of instruction. of Dental Medicine (SDM), founded in 2002, estab-

The evidence base for integrated curricula first lished a curriculum that implements both vertical

appeared in small, progressive medical colleges,11,12 and horizontal integration of the three disciplines of

which helped to direct modernization and improve- biomedical, behavioral, and clinical sciences.7,19,23

ment efforts towards more interdisciplinary and in- The original intent of the UNLV-SDM’s mission was

tegrated courses that became widely adopted within to offer foundation subject matter concurrently with

medical and health science centers.13-15 Integrated clinical instruction to complement the clinical setting

curricula then began to appear in combination with and ensure achievement of clinical competence. The

problem-based learning (PBL),16 and frameworks purpose of this educational research project was to

for specific types of integration, such as vertical and evaluate the SDM curriculum and determine the

horizontal integration, evolved further.17,18 These extent of integration of the current curriculum as

frameworks for vertical and horizontal integration it relates to the ten models of integration outlined

and integrated multi- and interdisciplinary teaching above. This comprehensive evaluation will aid in

have been further developed within the dental school developing future strategies aimed towards enhanc-

setting.5,9,19 Although standardization of these con- ing the SDM curriculum model in the future and may

cepts and frameworks has been called for,8 a working serve as a useful example for other schools with the

definition has not yet been standardized. same goals.

Many proposed frameworks of integration

focus on creating general categories that include a

combination of approaches for connecting topics Methods

or disciplines. For instance, Fogarty defined three

categories of courses: 1) courses that fall within a All current UNLV-SDM course directors (CDs)

single discipline, 2) courses that fall within mul- (n=38) were asked to evaluate each of their courses

tiple disciplines, and 3) courses in which the learner (n=84) using a brief survey instrument. From a list of

is immersed in the learning.20-22 Courses within a the ten models of integration, the CDs were asked to

single discipline are, fundamentally, the more tra- select the model they perceived best illustrated their

ditional method of individual class instruction, in course framework and design. Although the course

which there is little or no relationship with other may potentially fall within more than one model

courses. Courses incorporating multiple disciplines based on their design, each CD was instructed to se-

integrate several different topics or subjects that have lect only one model from the list that best represented

some commonality or relevant connections. Courses his or her course.

with an immersed theme involve a learning process The survey instrument included a visual display

internal to the student, gained from learning prob- and definition of each of the ten models of integra-

lem-solving skills and also critical thinking. Within tion, as defined by Fogarty.20,21 Prior to the adminis-

these three general categories, Fogarty defined ten tration of the survey instrument, all faculty members

August 2009 ■ Journal of Dental Education 963

Table 1. Operational definitions of models of integration

Model Operational Definition

Single Discipline

Fragmented Focuses on a traditional pedagogical approach in which subject matter and/or courses are disconnected.

Subject matter is linked only by coincidence.

Connected Subject matter within a single discipline is connected from course to course. Key concepts taught in a

course lead to concepts within a subsequent course.

Nested Multiple skills are taught within a single course.

Multiple Discipline

Sequenced Topics within a single department/discipline are arranged to coincide with one another.

Shared Faculty within a single department/discipline do team planning and/or teaching in which overlapping

concepts emerge.

Threaded Skills are taught in a specific order as they feed into the next topic or skill within and across departments/

disciplines.

Webbed A common theme serves as a basis for instruction within and across departments/disciplines.

Integrated Interdisciplinary approach in which faculty do team planning and/or teaching both within disciplines and

across departments.

Learner Models

Networked Courses are taught so that students are required to integrate content that leads to external networks in the

field of dentistry.

Immersed Courses are student-centered so that the learner filters the content and becomes immersed/absorbed in his

or her learning experience.

Sources: Based on Fogarty R. Ten ways to integrate curriculum. Educational Leadership 1991;49:2; and Fogarty R, Stoehr J. Integrating

curricula with multiple intelligences: teams, themes, and threads. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2007.

and CDs were presented with a brief review of the the data were gathered, courses were matched to the

history of curriculum integration during a UNLV- models to create a representation of the current level

SDM faculty retreat. This review of curriculum of integration and determine the number of courses

integration included more prevalent theories found in within each model.

the literature involving integrated curriculum models, Approval for administration of the survey and

including the ten models of integration described the administration protocol were received from the

above. Faculty members were encouraged to engage UNLV Institutional Research Board (IRB), as an

in discussions of this framework and these models exemption to human subjects research under the

as they relate to the current curriculum at SDM and Basic HHS Policy for Protection of Human Research

to ask questions specific to their courses. Subjects (OPRS#0801-2599).

The total number of courses was tallied for each

of the ten models, and course numbers were cross-

referenced to create several independent matrices Results

depicting the current level of integration as perceived

by faculty members. The majority of courses were The UNLV-SDM is comprised of three depart-

assigned as, or belonging, to two basic themes: 1) ments: Biomedical Sciences, Professional Stud-

across departments/disciplines, and 2) within and ies, and Clinical Sciences. Figure 1 outlines the

across departments/disciplines. Differences between relationship within the school regarding curriculum

the themes were found among all the UNLV-SDM development and feedback. The three departments

courses using chi-square distribution. Chi-square jointly coordinate the curriculum, which is then

analysis was determined to be the most appropriate presented to the curriculum committee for approval.

test, as it is most commonly used to make infer- The curriculum committee is comprised of faculty

ences about a single population variance, although representatives from each department and two dental

it may be useful in many other applications.24 Once student representatives. The curriculum committee

964 Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 73, Number 8

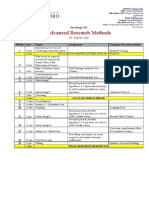

Executive Committee

Student Focus

BIOMEDICAL

Groups

SCIENCES

CURRICULUM

COMMITTEE

CLINICAL PROFESSIONAL

SCIENCES STUDIES

Figure 1. UNLV-SDM departmental relationships regarding curriculum development

also receives input from student focus groups and vidual department, or dental student school year, the

the executive committee in making final curriculum courses were also segregated and analyzed by these

determinations. criteria (Figures 4 and 5). The results of the survey

Course survey results were obtained from revealed that no course at SDM fell within the frag-

thirty-eight faculty members encompassing eighty- mented or traditional silo model. The majority of the

four courses, which represented 100 percent of the courses fell within two themes: across departments/

courses offered in the SDM curriculum. Course disciplines, and within and across disciplines/depart-

numbers were cross-referenced to create several ments (fifty-four out of eighty-four, Figure 4). The

matrixes depicting faculty members’ perceptions of “within and across disciplines” themes were found

the current level of integration. After reviewing the to have the most number of courses (twenty-eight);

information, four specific themes emerged: 1) courses however, the individual model “shared,” which falls

in which integration primarily occurred within a into the “across disciplines” theme, was the model

single discipline, 2) courses in which integration selected most by faculty members as representing

occurred primarily across disciplines, 3) courses the level of integration (twenty courses). With the

in which integration primarily occurred within and chi-square analysis, significant differences between

across disciplines, and 4) courses in which integra- the themes were found. There were significant dif-

tion primarily occurred within and across learners. ferences in the curriculum between the number of

The ten models of integration were then organized courses “within a single discipline” (n=16) and the

within these four themes (Figure 2). number of courses “across disciplines” (n=26) and

Once the four themes were established, courses “within and across disciplines” (n=29) (χ2=4.65,

were mapped to match the theme and model. Figure 3 p=0.003). Significant differences were also found

depicts the total number of courses tallied for each of in the curriculum between the number of courses

the ten models. In order to ascertain any patterns of “within and across learners” (n=14) and the number

integration with respect to the integration theme, indi- of courses “across disciplines” (n=26) and “within

August 2009 ■ Journal of Dental Education 965

WITHIN A SINGLE

DISCIPLINE

FRAGMENTED

CONNECTED

NESTED

ACROSS DISCIPLINES

SEQUENCED

SHARED

WITHIN AND ACROSS

DISCIPLINES

THREADED

INTEGRATED

WEBBED

WITHIN AND ACROSS

LEARNERS

IMMERSED

NETWORKED

Figure 2. Mapping of UNLV-SDM curriculum themes and models

and across disciplines” (n=29) (χ2=6.31, p=0.001). levels of integration (Figure 5A). With respect to

However, no significant differences were found departments responsible for the courses taught, there

between the number of courses “within a single dis- was a fairly even distribution among the four themes,

cipline” (n=16) and the number of courses “within with the exception of a relatively large number of

and across learners” (n=14) (p=0.42) or between the clinical sciences courses falling within the single

number of courses “across disciplines” (n=26) and discipline theme (Figure 5B).

the number of courses “within and across disciplines”

(n=29) (p=0.623). Figure 4 depicts the graphical

representation of the number of courses mapped to Discussion

the four identified themes. In addition, the identified

In the IOM report that documented challenges

themes were grouped by dental school year and by

facing dental education, one concern expressed was

department (Figure 5). Dental school year 4 (DS4)

that the current dental school curriculum is crowded

courses mapped entirely to the themes “within and

with redundant material, which is often taught in

across disciplines” and “within and across learners,”

disciplinary silos.1 The UNLV-SDM was in a unique

whereas DS1 courses were biased toward the lower

position to establish a curriculum that crossed tra-

966 Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 73, Number 8

Figure 3. Course mapping of UNLV-SDM courses to themes and models of integration

ditional disciplinary silos. This new dental school level of integration in the entire curriculum. Although

established a curriculum that implements both a definitions of integration vary widely and the SDM

vertical and horizontal integration of the biomedi- departmental organization already encompassed

cal, behavioral, and clinical sciences,23 and a unique integration of multiple disciplines, the ten models of

departmental organization was created. integration as proposed by Fogarty were used as an

In order to promote curriculum innovation dis- initial reference point for this evaluation.20-22

cussions, share strategies, provide leadership, and as- An analysis of the course survey resulted in the

sist with the dissemination of information, the ADEA categorization of the ten models into four themes.

CCI enlisted the help of representatives or liaisons This organization into themes aided in the evaluation

from participating dental schools. The liaisons attend of the level of integration of the SDM curriculum

special conferences twice yearly; attendance has as a whole. Although definitions of integration vary

included representatives from over forty-six dental widely throughout the literature, one prevailing con-

schools and upwards of 140 participants. The liaisons cept included in all integration models is that integra-

were charged with identifying a curriculum reform tion represents a continuum, along which learners

project for their individual dental schools. In consul- are taught subject matter ranging from lower levels

tation with the dean of the UNLV-SDM, the school’s of integration such as fragmented and nested models

liaisons identified a project to evaluate the integrated to higher levels of integration in which the learner is

curriculum to determine if the original goals had been immersed in the subject material and makes decisions

met and to determine future directions for change based upon knowledge and experience. The SDM

in the curriculum. As a first step in the UNLV-SDM curriculum was organized into four themes.

curriculum evaluation, the liaisons participated in a The first theme—within a single discipline

faculty retreat and conducted a survey to ascertain the models—included the fragmented, connected, and

August 2009 ■ Journal of Dental Education 967

Total SDM Courses Mapped to Themes

**

30 * **

*

25

20

Number of Courses

15

10

0

Single Discipline Across Within and Within and

Disciplines Across Across Learners

Disciplines

*p=0.003 **p=0.001

Figure 4. Distribution of UNLV-SDM courses across integration themes

nested models. The fragmented model is the more skills taught to DS1 and DS2 students prior to entry

traditional pedagogical approach, in which a course into the clinic. While DS1, DS2, and DS3 courses

is taught as a separate and distinct unit. The con- were mapped to “within a single discipline,” no DS4

nected model views subject matter within a single courses were mapped to this theme. While this result

discipline as connected from course to course. Key could be anticipated, it was reassuring to confirm that

concepts taught in a course lead to concepts within DS4 courses were being offered at the highest levels

a subsequent course. The nested model uses a three- of integration.

dimensional approach in which multiple skills are The second theme—across discipline mod-

taught within a single course.25 None of the SDM els—includes the sequenced and shared models. The

courses mapped to the fragmented model, which sequenced model views the course matter as separate

likely reflects the integrated nature of the SDM information connected by a common theme. Units

departmental structure. Only one biomedical sci- are taught separately, but rearranged or sequenced

ence and two behavioral science courses mapped to in such a manner as to create a framework to relate

this theme of integration. Fourteen clinical science the concepts. The shared model brings different

courses were identified as “nested” within the single subject matter together into a single theme using

discipline theme. This relatively large number of overlapping concepts to organize the framework. The

clinical courses likely reflects the basic clinical motor shared model was the single model selected most by

968 Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 73, Number 8

SDM Courses Mapped to Themes by Dental School

A. Year

Course Percentage to Total Course

80

70

60

Offered in Year

DS1

50

DS2

40

DS3

30

DS4

20

10

0

Single Across Within and Within and

Discipline Disciplines Across Across

Disciplines Learners

SDM Courses Mapped to Themes by Department

B.

Course Percentage to Total Course

50

45

Offered by Departments

40

35

30 Biomedical Science

25 Behavior Sciences

20 Clinical Sciences

15

10

5

0

Single Across Within and Within and

Discipline Disciplines Across Across

Disciplines Learners

Figure 5. Distribution of UNLV-SDM courses in integration themes

the course directors. The majority of courses falling The third theme—within and across discipline

within this theme were DS1 and DS2 courses; again models—included the webbed, threaded, and inte-

there was a lack of DS4 courses. All three depart- grated models. The webbed model uses a common

ments mapped courses within this theme with no theme to integrate subject matter. The threaded model

remarkable differences. develops several ideas and then threads them together

August 2009 ■ Journal of Dental Education 969

using a common theme. The integrated model rear-

ranges subject matter around overlapping concepts, Conclusions

patterns, and designs, blending them together. The

All courses in the SDM curriculum were found

“within and across discipline” theme was the most

to have at least some level of integration. More than

commonly identified theme for SDM courses. Cours-

half (n=43) were found to be both horizontally and

es from all dental school years were represented in

vertically integrated. The number of courses falling

this theme as well as from each department.

within each theme represented a bell-shaped curve,

The fourth theme—within and across learner

with fewer courses at both the lowest and high-

models—included the immersed and networked

est level of integration. This distribution reflects a

models. The immersed model allows the learner to

continuum of integration that parallels the needs of

take information previously gathered and look more

dental students as they progress through their dental

deeply into its meaning and uses. The learner begins

education. The majority of DS4 courses mapped

to integrate all data with little or no outside interven-

to the highest level of integration, reflecting the

tion. The networked model takes the learner beyond

expectation that DS4 students are capable of using

the immersed level. Learners are able to target re-

their acquired foundational knowledge to approach

sources within and across their areas of study through

subject matter with critical thinking skills. Because

the use of experts. This is where the learner works

the assessment of level of course integration was

independently with minimal oversight. Seventy-five

based on self-reported perceptions of faculty mem-

percent of the DS4 courses mapped to this level of

bers, future studies should look at whether the level

integration. In contrast, relatively few DS1, DS2, and

selected actually reflects course content and whether

DS3 courses were assigned to this theme.

the model chosen is the most appropriate for teach-

There are some limitations to drawing conclu-

ing the course content. Future studies will address

sions from this study. SDM courses were assigned to

these issues in our continuing efforts to evaluate the

one level of integration by the course directors after

SDM curriculum.

a faculty retreat that introduced each of the ten mod-

els of integration. The survey instrument contained

a visual guide and definitions of the ten models of REFERENCES

1. Field MJ, ed. Dental education at the crossroads: chal-

integration to assist faculty members in assigning

lenges and change. An Institute of Medicine Report.

their courses to one level of integration. Although Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1995.

the course directors are the most knowledgeable 2. Kalkwarf KL, Haden NK, Valachovic RW. ADEA Com-

persons concerning course content and design, each mission on Change and Innovation in Dental Education.

faculty member could conceivably have interpreted J Dent Educ 2005;69(10):1085–7.

3. American Dental Education Association. Competencies

the defined levels of integration differently. A more

for the new general dentist (as approved by the 2008 ADEA

unbiased approach could utilize a panel of calibrated House of Delegates). J Dent Educ 2008;72(7):810–22.

faculty to assign each course to a level of integration 4. Melnick SA, Schubert MB. Curriculum integration: es-

based upon a thorough review of course content and sential elements for success. Presentation at the Annual

design. However, this labor-intensive process seemed Meeting of the American Educational Research Associa-

unjustified for this initial evaluation of the SDM tion, Chicago, IL, 1997.

5. Allen KL, More FG. Clinical simulation and foundation

curricula. In addition to the possibility of some am- skills: an integrated multidisciplinary approach to teach-

biguity concerning the models of integration, some ing. J Dent Educ 2004;68(4):468–74.

courses could genuinely encompass more than one 6. Jansen DA, Morse WA. Positively influencing student

level of integration. For instance, the first portion nurse attitudes toward caring for elders: results of a cur-

of the course could present basic concepts, while riculum assesment study. Gerontology Geriatrics Educ

2004;25(2):1–14.

the second half utilizes a more integrated approach. 7. Kingsley K, O’Malley S, Stewart T, Howard KM. Re-

Because the study limitations were encountered by all search enrichment: evaluation of structured research in

the CDs, the statistical differences identified in this the curriculum for dental medicine students as part of the

study likely reflect the overall level of integration of vertical and horizontal integration of biomedical training

the SDM curriculum. and discovery. BMC Med Educ 2008;8:9.

8. Kysilka M. Understanding integrated curriculum. Cur-

riculum J 1998;9(2):197–209.

9. Snyman W, Kroon J. Vertical and horizontal integration of

knowledge and skills: a working model. Eur J Dent Educ

2005;9:26–31.

970 Journal of Dental Education ■ Volume 73, Number 8

10. Drake SM, Burns RC. Meeting standards through in- 18. Dahle LO, Brynhildsen J, Fallsberg MB, Rundquist I,

tegrated curriculum. Alexandria, VA: Association for Hammar M. Pros and cons of vertical integration between

Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2004. clinical medicine and basic science within a problem-

11. Geffen LB, Birkett DJ, Alpers JH. The Flinders experiment based undergraduate medical curriculum: examples

in medical education revisited. Med J Aust 1991;155(11– and experiences from Linkoping, Sweden. Med Teach

12):745–50. 2002;24(3):280–5.

12. St Jeor ST, Scott BJ, MacKintosh FR, Daugherty SA, 19. Kingsley K, O’Malley S, Stewart T, Galbraith GM. The

Goodman PH, Lazerson J. Nutrition education curriculum integration seminar: a first-year dental course integrating

at the University of Nevada School of Medicine. J Cancer concepts from the biomedical, professional, and clinical

Educ 1989;4(4):235–40. sciences. J Dent Educ 2007;71(10):1322–32.

13. Blue AV, Garr D, Del Bene V, McCurdy L. Curricular 20. Fogarty R. Ten ways to integrate curriculum. Educational

renewal for the new millennium at the Medical University Leadership 1991;49:2.

of South Carolina College of Medicine. J S C Med Assoc 21. Fogarty R, Stoehr J. Integrating curricula with multiple

2000;96(1):22–7. intelligences: teams, themes, and threads. Palatine, IL:

14. Curry RH, Makoul G. The evolution of courses in profes- Skylight Publishing, Inc., 1995.

sional skills and perspectives for medical students. Acad 22. Fogarty R, Stoehr J. Integrating curricula with multiple

Med 1998;73(1):10–3. intelligences: teams, themes, and threads. 2nd ed. Thou-

15. Nierenberg DW. The use of “vertical integration groups” sand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2007.

to help define and update course/clerkship content. Acad 23. School of Dental Medicine, University of Nevada, Las

Med 1998;73(10):1068–71. Vegas. Vision, mission & goals. At: http://dentalschool.

16. Harden R, Crosby J, Davis MH, Howie PW, Struthers unlv.edu/vision.html. Accessed: January 16, 2009.

AD. Task-based learning: the answer to integration and 24. Hayes W. The chi-square and the f distributions. In: Hayes

problem-based learning in the clinical years. Med Educ W, ed. Statistics, 5th ed. Fort Worth: International Thom-

2000;34(5):391–7. son Publishing, 1994:350–75.

17. Brynhildsen J, Dahle LO, Fallsberg MB, Rundquist I, 25. Jacobs H. Interdisciplinary curriculum: design and imple-

Hammar M. Attitudes among students and teachers on mentation. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision

vertical integration between clinical medicine and basic and Curriculum Development, 1989.

science within a problem-based undergraduate medical

curriculum. Med Teach 2002;24(3):286–8.

August 2009 ■ Journal of Dental Education 971

You might also like

- Nursing Ethics and Jurisprudence 1Document17 pagesNursing Ethics and Jurisprudence 1dmsapostol100% (2)

- AMEE Guide No. 4 Effective Continuing Education - The CRISIS CriteriaDocument16 pagesAMEE Guide No. 4 Effective Continuing Education - The CRISIS CriteriaaungNo ratings yet

- (Ana Smith Iltis) Research Ethics (Routledge Annal (BookFi)Document192 pages(Ana Smith Iltis) Research Ethics (Routledge Annal (BookFi)Zaneta DivjakoskaNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1: Quarter 3 - Module 2: Characteristics, Processes and Ethics of ResearchDocument32 pagesPractical Research 1: Quarter 3 - Module 2: Characteristics, Processes and Ethics of ResearchVINCENT BIALEN80% (30)

- Obe PDFDocument6 pagesObe PDFjaycee_evangelistaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Compacting: An Easy Start to Differentiating for High Potential StudentsFrom EverandCurriculum Compacting: An Easy Start to Differentiating for High Potential StudentsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Graduating European Dentist: Contemporaneous Methods of Teaching, Learning and Assessment in Dental Undergraduate EducationDocument8 pagesThe Graduating European Dentist: Contemporaneous Methods of Teaching, Learning and Assessment in Dental Undergraduate Educationalvin fauziyahNo ratings yet

- Eur J Dental Education - 2017 - Field - The Graduating European Dentist A New Undergraduate Curriculum FrameworkDocument9 pagesEur J Dental Education - 2017 - Field - The Graduating European Dentist A New Undergraduate Curriculum FrameworkHernández Becerra Ivanna PaolaNo ratings yet

- 2 Eur J Dental Education - 2008 - Oliver - Curriculum Structure Principles and StrategyDocument11 pages2 Eur J Dental Education - 2008 - Oliver - Curriculum Structure Principles and StrategyRiris MarisaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Undergraduate Dental Education Curriculum (BDS)Document248 pagesGuidelines For Undergraduate Dental Education Curriculum (BDS)aamnashah25100% (1)

- Problem-Based Learning: An Interdisciplinary Approach in Clinical TeachingDocument6 pagesProblem-Based Learning: An Interdisciplinary Approach in Clinical TeachingArdianNo ratings yet

- Vertical and Horizontal Integration of K PDFDocument6 pagesVertical and Horizontal Integration of K PDFTrường Nguyễn HuyNo ratings yet

- The Changing Face of Dental Education: The Impact of PBL: Educational MethodologiesDocument16 pagesThe Changing Face of Dental Education: The Impact of PBL: Educational MethodologiesDr. Erwin HandokoNo ratings yet

- Edu623 Designing Learning Environments Final Project Eschlegel May 01-2016Document19 pagesEdu623 Designing Learning Environments Final Project Eschlegel May 01-2016api-317109664No ratings yet

- A Model For Easily Incorporating Team-Based Learning Into Nursing EducationDocument16 pagesA Model For Easily Incorporating Team-Based Learning Into Nursing EducationMuhammad Wahyu NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Instituto Nacional de Salud Pu Blica: Innovations in Graduate Public Health Education: TheDocument4 pagesInstituto Nacional de Salud Pu Blica: Innovations in Graduate Public Health Education: TheForce MapuNo ratings yet

- The Challenge of Change: Introducing Flexible Learning Into A Traditional Medical and Health Sciences FacultyDocument9 pagesThe Challenge of Change: Introducing Flexible Learning Into A Traditional Medical and Health Sciences FacultyAnonpcNo ratings yet

- Application of Theories Principles and Models of Curriculum Munna and Kalam 2021Document7 pagesApplication of Theories Principles and Models of Curriculum Munna and Kalam 2021Vaughan LeaworthyNo ratings yet

- Ar HeaDocument48 pagesAr HeaAneelaNo ratings yet

- Physical Sciences: Principles of Inclusive Curriculum DesignDocument5 pagesPhysical Sciences: Principles of Inclusive Curriculum DesignIjNo ratings yet

- Innovation in ELTDocument4 pagesInnovation in ELTHà Đặng Nguyễn NgânNo ratings yet

- Curricullum - Models - Black FontsDocument50 pagesCurricullum - Models - Black FontsAnas khanNo ratings yet

- Educational Summary Report 10454Document6 pagesEducational Summary Report 10454kman0722No ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6105 Assessment 4 Assessment Strategies and Complete Course PlanDocument12 pagesNURS FPX 6105 Assessment 4 Assessment Strategies and Complete Course PlanEmma WatsonNo ratings yet

- Ect 212 Curriculum ImplementationDocument81 pagesEct 212 Curriculum Implementationaroridouglas880No ratings yet

- 12 Tips para Renovación CurricularDocument8 pages12 Tips para Renovación CurricularNAYITA_LUCERONo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development in Nursing Education. Where Is The Pathway?Document6 pagesCurriculum Development in Nursing Education. Where Is The Pathway?IOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Learning Teaching - Learning MethodsDocument55 pagesFacilitating Learning Teaching - Learning MethodsIeda RahmanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1807593222001119 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1807593222001119 MainNadiraNo ratings yet

- Learning Outcomes and Instructional ObjectivesDocument6 pagesLearning Outcomes and Instructional Objectivesvinoth_2610100% (1)

- Modern Techniques of TeachingDocument16 pagesModern Techniques of TeachingVaidya Omprakash NarayanNo ratings yet

- AdvocacyTraining Web Version FinalDocument16 pagesAdvocacyTraining Web Version FinalEmanNo ratings yet

- Salado MAEPM COMPRE EXAM IN CURDEVDocument3 pagesSalado MAEPM COMPRE EXAM IN CURDEVRovie SaladoNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument14 pagesResearch ProposalRaki' Tobias JonesNo ratings yet

- Curric Instruct Desgn-Assgn 1Document14 pagesCurric Instruct Desgn-Assgn 1api-630481673No ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document61 pagesChapter 10Manar ShamielhNo ratings yet

- Combining Chalk Talk With Powerpoint To Increase In-Class Student EngagementDocument13 pagesCombining Chalk Talk With Powerpoint To Increase In-Class Student EngagementJuan Augusto Fernández TarazonaNo ratings yet

- Jdenteduc 2010 74 464 471Document8 pagesJdenteduc 2010 74 464 471YuniarNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Preparedness and Practice Management Skills of Graduating Dental Students Entering The Work ForceDocument8 pagesResearch Article: Preparedness and Practice Management Skills of Graduating Dental Students Entering The Work ForceNurul HusnaNo ratings yet

- MELCs WalkthroughDocument23 pagesMELCs WalkthroughallanrnmanalotoNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Development Thesis PDFDocument7 pagesCurriculum Development Thesis PDFaflpaftaofqtoa100% (2)

- Staff Support in Continuing Professional DevelopmentDocument6 pagesStaff Support in Continuing Professional DevelopmentAmealyena AdiNo ratings yet

- Conference Paper No. 35: Curriculum Redevelopment: Stakeholders Sharing The Decision MakingDocument18 pagesConference Paper No. 35: Curriculum Redevelopment: Stakeholders Sharing The Decision MakingWallacyyyNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Studies EssayDocument14 pagesCurriculum Studies EssayDaiva Stalnionyte100% (1)

- Poster Writing To CheckDocument10 pagesPoster Writing To Checklaetitiarousselin4No ratings yet

- SamihussDocument7 pagesSamihussNader ElbokleNo ratings yet

- Towards A Theoretical Framework For Curriculum Development in Health Professional EducationDocument14 pagesTowards A Theoretical Framework For Curriculum Development in Health Professional EducationNgọc Linh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Curriculum & Course DesignDocument4 pagesCurriculum & Course DesignGhulam MujtabaNo ratings yet

- Assigment CurriculumDocument3 pagesAssigment CurriculumJoseph Elvinio PerrineNo ratings yet

- The Compromised Most Essential Learning Competencies: An Qualitative InquiryDocument11 pagesThe Compromised Most Essential Learning Competencies: An Qualitative InquiryPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- ScienceDirect Citations 1715638522749Document15 pagesScienceDirect Citations 1715638522749luis.velasquezNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument25 pagesContent ServersyaNo ratings yet

- Assessment For Learning - An Introduction To The ESCAPE ProjectDocument11 pagesAssessment For Learning - An Introduction To The ESCAPE ProjectYuslaini YunusNo ratings yet

- Henzi Etal (2006) - Perspectives Dental Students About Clinical EducationDocument17 pagesHenzi Etal (2006) - Perspectives Dental Students About Clinical EducationMiguel AraizaNo ratings yet

- Yiu 2011Document10 pagesYiu 2011Chris MartinNo ratings yet

- SLACDocument25 pagesSLACWinnie Poli100% (2)

- Rosal Hubilla y Carillo Vs Case DigestDocument17 pagesRosal Hubilla y Carillo Vs Case DigestbaimonaNo ratings yet

- Latest Research Docx Teshale Wirh Cfwork - For MergeDocument23 pagesLatest Research Docx Teshale Wirh Cfwork - For MergeTeshale DuressaNo ratings yet

- Supporting Academic Development To Enhance The Student ExperienceDocument12 pagesSupporting Academic Development To Enhance The Student ExperienceHazel Owen100% (1)

- The Schoolwide Enrichment Model in Science: A Hands-On Approach for Engaging Young ScientistsFrom EverandThe Schoolwide Enrichment Model in Science: A Hands-On Approach for Engaging Young ScientistsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Embedding Equality and Diversity into the Curriculum – a literature reviewFrom EverandEmbedding Equality and Diversity into the Curriculum – a literature reviewNo ratings yet

- Medical Education in Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine: Advanced Concepts and StrategiesFrom EverandMedical Education in Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine: Advanced Concepts and StrategiesPatricia A. KritekNo ratings yet

- Using the National Gifted Education Standards for Pre-KGrade 12 Professional DevelopmentFrom EverandUsing the National Gifted Education Standards for Pre-KGrade 12 Professional DevelopmentRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (8)

- NURS FPX 5005 Assessment 1 Protecting Human Research ParticipantsDocument4 pagesNURS FPX 5005 Assessment 1 Protecting Human Research ParticipantsEmma WatsonNo ratings yet

- Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar Lie, Franklin Miller, David Wendler - The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics (2008)Document848 pagesEzekiel J. Emanuel, Christine Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar Lie, Franklin Miller, David Wendler - The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics (2008)Dóri PappNo ratings yet

- What Is Research Ethics?Document7 pagesWhat Is Research Ethics?Nadie Lrd100% (1)

- Biomedical EngineeringDocument5 pagesBiomedical EngineeringFranch Maverick Arellano Lorilla100% (1)

- Syllabus Soc 616 Spring 08 SillsDocument18 pagesSyllabus Soc 616 Spring 08 SillsStephen SillsNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in Conducting SIPDocument60 pagesEthical Issues in Conducting SIPMavrichk100% (1)

- Critical Thinking in Clinical ResearchDocument491 pagesCritical Thinking in Clinical ResearchGustavo AndradeNo ratings yet

- 2022 October - Vol 37, No. 10Document12 pages2022 October - Vol 37, No. 10S. FelixNo ratings yet

- Becoming Widely Available Associated Press Story External Icon Concluded PDF Iconexternal IconDocument5 pagesBecoming Widely Available Associated Press Story External Icon Concluded PDF Iconexternal IconmattyNo ratings yet

- Module 5 PEDocument28 pagesModule 5 PEGauri GhuleNo ratings yet

- Research International RulesDocument41 pagesResearch International RulesEinstein Claus Balce Dagle100% (1)

- Thesis Statement Animal TestingDocument8 pagesThesis Statement Animal Testingafcmwheic100% (2)

- The Ethical Context of ResearchDocument9 pagesThe Ethical Context of ResearchArianne FarnazoNo ratings yet

- 2019-03-19 - MoH GSR 227 - New Drugs and Clinical Trial Approval Regulations 2019-147-264Document118 pages2019-03-19 - MoH GSR 227 - New Drugs and Clinical Trial Approval Regulations 2019-147-264go downNo ratings yet

- Ethics in ResearchDocument13 pagesEthics in ResearchCarissa De Luzuriaga-BalariaNo ratings yet

- What Makes Clinical Research EthicalDocument12 pagesWhat Makes Clinical Research EthicalMagda VillarrealNo ratings yet

- Principles of Ethics in Clinical Trials-Prof. Dr. Dr. Rianto Setiabudy, SPFKDocument23 pagesPrinciples of Ethics in Clinical Trials-Prof. Dr. Dr. Rianto Setiabudy, SPFKJoko WinarnoNo ratings yet

- POPIA Code of Conduct For ResearchDocument12 pagesPOPIA Code of Conduct For ResearchKayla RobinsonNo ratings yet

- UNICEF Procedure On Ethics in Evidence Generation 092015Document23 pagesUNICEF Procedure On Ethics in Evidence Generation 092015Panagiotis StathopoulosNo ratings yet

- ICAST Combined Manuals V3Document46 pagesICAST Combined Manuals V3MazlinaNo ratings yet

- HealthSystemResearch DevelopmentDesignsandMethodsDocument6 pagesHealthSystemResearch DevelopmentDesignsandMethodsSani BaniaNo ratings yet

- Module 1. Lesson2Document18 pagesModule 1. Lesson2Titser G.No ratings yet

- Electronic Torture - JeffPolachek - Study of Bio Ethical Issues - Mind Control Victim TestimonyDocument14 pagesElectronic Torture - JeffPolachek - Study of Bio Ethical Issues - Mind Control Victim Testimonystop-organized-crimeNo ratings yet

- SAS - Session-26-Research 1Document5 pagesSAS - Session-26-Research 1ella retizaNo ratings yet

- Conduct & Public Disclosure of Human Suject Research Policy POL-GSKF-408Document10 pagesConduct & Public Disclosure of Human Suject Research Policy POL-GSKF-408ouñateNo ratings yet

- Online IRB Certification NIH Drug Lit AnswersDocument5 pagesOnline IRB Certification NIH Drug Lit AnswersITisNeil67% (3)

- Isef Rules and GuidelinesDocument16 pagesIsef Rules and GuidelinesAia Mie Cornel CometaNo ratings yet