Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Drnyei MotivationMotivatingForeign 1994

Drnyei MotivationMotivatingForeign 1994

Uploaded by

Macs PorCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Underwarren Grimoire Spells From BelowDocument15 pagesUnderwarren Grimoire Spells From BelowMatheus RomaNo ratings yet

- Seven Secrets Boxing FootworkDocument25 pagesSeven Secrets Boxing Footworkehassan4288% (16)

- Hurricane HardwareDocument20 pagesHurricane HardwareRohn J JacksonNo ratings yet

- Dornyei (1994) Foreign Language Classroom PDFDocument13 pagesDornyei (1994) Foreign Language Classroom PDFdk_ain100% (1)

- Task 2 - Concept, Characteristics and Learning StylesDocument8 pagesTask 2 - Concept, Characteristics and Learning StylesScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Background, Rationale, and Purpose: Constructivism, For Instance, A Modern Theory of Knowledge, Holds ThatDocument8 pagesChapter 1: Background, Rationale, and Purpose: Constructivism, For Instance, A Modern Theory of Knowledge, Holds ThatHeidi JhaNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Foundation For Curriculum Development in NepalDocument15 pagesPhilosophical Foundation For Curriculum Development in NepalTe MenNo ratings yet

- Learning Theories For Tertiary Education A Review of Theory Application and Best PracticeDocument7 pagesLearning Theories For Tertiary Education A Review of Theory Application and Best PracticeInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework 1Document16 pagesTheoretical Framework 1bonifacio gianga jrNo ratings yet

- Social Interaction and The Use of Analogy An Analysis of Preservice TeachersDocument21 pagesSocial Interaction and The Use of Analogy An Analysis of Preservice TeachersAnanda Hafizhah PutriNo ratings yet

- Apjeas PDFDocument6 pagesApjeas PDFacer1979No ratings yet

- Dornyei - Understanding L2 MotivationDocument10 pagesDornyei - Understanding L2 MotivationMarina Smirnova100% (1)

- Matrik Anotasi Landasan, Pendekatan & Prinsip KurDocument4 pagesMatrik Anotasi Landasan, Pendekatan & Prinsip Kurdenbagusardap685No ratings yet

- (JOURNAL) Salma Ladina's JournalDocument13 pages(JOURNAL) Salma Ladina's Journalsalmalad13No ratings yet

- Revised PED 702 - MA ELEDocument31 pagesRevised PED 702 - MA ELEMarvic ReyesNo ratings yet

- Ped 702 Topic 1Document15 pagesPed 702 Topic 1amara de guzmanNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning EnhancementDocument16 pagesTeaching and Learning EnhancementAshraf ImamNo ratings yet

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument7 pagesCurriculum Developmentitsnisarahmed7443No ratings yet

- New Themes and Approaches in Second Language Motivation ResearchDocument19 pagesNew Themes and Approaches in Second Language Motivation ResearchJonny IreNo ratings yet

- The Essential of Instructional DesignDocument18 pagesThe Essential of Instructional DesignEka KutateladzeNo ratings yet

- Thesis Chapter 1Document10 pagesThesis Chapter 1Maria Camille Villanueva SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Rosenberg Koehler 2015 HRTEDADocument27 pagesRosenberg Koehler 2015 HRTEDAVincentNo ratings yet

- Professional Development in ScienceDocument87 pagesProfessional Development in ScienceUdaibir PradhanNo ratings yet

- Teaching ReadingDocument27 pagesTeaching Readingahmed alaouiNo ratings yet

- Rosenberg Koehler 2015 HRTEDADocument27 pagesRosenberg Koehler 2015 HRTEDARena mehdisyahmilaNo ratings yet

- The Nature and Methods of Learning by Doing: American Psychologist December 2001Document35 pagesThe Nature and Methods of Learning by Doing: American Psychologist December 2001Francisco Delgado NietoNo ratings yet

- The Applicability of Active Teaching-Learning Methodologies in Health: An Integrative ReviewDocument6 pagesThe Applicability of Active Teaching-Learning Methodologies in Health: An Integrative ReviewIJAERS JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Thinking Skills and Creativity: Martín Cáceres, Miguel Nussbaum, Jorge Ortiz TDocument18 pagesThinking Skills and Creativity: Martín Cáceres, Miguel Nussbaum, Jorge Ortiz TdillaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Concept Mapping Strategy On Cognitive Processes in Science at Secondary LevelDocument19 pagesEffectiveness of Concept Mapping Strategy On Cognitive Processes in Science at Secondary LevelShirley de LeonNo ratings yet

- Expansive Framing As Pragmatic Theory For Online and Hybrid Instructional DesignDocument32 pagesExpansive Framing As Pragmatic Theory For Online and Hybrid Instructional DesignsprnnzNo ratings yet

- The Role of Assessment in A Learning Culture. ShepardDocument11 pagesThe Role of Assessment in A Learning Culture. ShepardMariana CarignaniNo ratings yet

- ID Analisis Keterampilan Berpikir Kritis CADocument6 pagesID Analisis Keterampilan Berpikir Kritis CAspasi masaNo ratings yet

- The Portfolio As A Tool For Stimulating Re Ection by Student TeachersDocument16 pagesThe Portfolio As A Tool For Stimulating Re Ection by Student TeachersMelissa AvilaNo ratings yet

- Peer Observation of Teaching PDFDocument24 pagesPeer Observation of Teaching PDFDanonino12No ratings yet

- JSS Hughes Davis Imenda2019Document13 pagesJSS Hughes Davis Imenda2019John Raizen Grutas CelestinoNo ratings yet

- The Leaners' View On Interdisciplinary Approach in Teaching Purposive CommunicationDocument4 pagesThe Leaners' View On Interdisciplinary Approach in Teaching Purposive CommunicationTricia Mae Comia AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Passion and Commitment in Teaching Research-A Meta-SynthesisDocument10 pagesPassion and Commitment in Teaching Research-A Meta-SynthesisKhairul Yop AzreenNo ratings yet

- Teaching Controversial Issues in SocialDocument12 pagesTeaching Controversial Issues in Socialenglishlina1No ratings yet

- Adam A Chapter 4Document28 pagesAdam A Chapter 4davidNo ratings yet

- Types and Class of EdResearchDocument75 pagesTypes and Class of EdResearchleandro olubiaNo ratings yet

- PR2 Research Chapter 2Document10 pagesPR2 Research Chapter 2Gabriel Jr. reyesNo ratings yet

- Motivation in Learning Contexts. Theoretical Advances and Methodological ImplicationsDocument20 pagesMotivation in Learning Contexts. Theoretical Advances and Methodological ImplicationsProf. Dr. Sattar AlmaniNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Instruction: Prospective Science Teachers' Conceptualizations About Project Based LearningDocument19 pagesInternational Journal of Instruction: Prospective Science Teachers' Conceptualizations About Project Based LearningYUNITA NUR ANGGRAENINo ratings yet

- Saf 1Document17 pagesSaf 1Siska WidiawatiNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and Education: Integrating Curriculum, Teaching and LearningDocument15 pagesPhilosophy and Education: Integrating Curriculum, Teaching and LearningSimon FillemonNo ratings yet

- Dthickey@indiana - Edu Gchartra@indiana - Edu Andrewch@indiana - EduDocument34 pagesDthickey@indiana - Edu Gchartra@indiana - Edu Andrewch@indiana - Edud-ichaNo ratings yet

- 2022 Al-Hoorie - Self-Determination Mini-Theories in Second Language Learning A Systematic Review of Three Decades of ResearchDocument36 pages2022 Al-Hoorie - Self-Determination Mini-Theories in Second Language Learning A Systematic Review of Three Decades of Researchraywilson.uoftNo ratings yet

- Project-Based Learning in Post-Secondary Education - TheoryDocument28 pagesProject-Based Learning in Post-Secondary Education - Theorysalie29296No ratings yet

- Rea Ramirez2008Document21 pagesRea Ramirez2008hajra yansaNo ratings yet

- Motivation and Foreign Language RacticeDocument3 pagesMotivation and Foreign Language RacticeJames ElechukwuNo ratings yet

- 608 1550 1 SMDocument7 pages608 1550 1 SMSkypperNo ratings yet

- Power and AgencyDocument35 pagesPower and AgencyFelipe Ignacio A. Sánchez VarelaNo ratings yet

- Contextualized and Localized Teaching As A Technique in Teaching Basic StatisticsDocument7 pagesContextualized and Localized Teaching As A Technique in Teaching Basic StatisticsSarah AgonNo ratings yet

- Ajmcsr11 161Document5 pagesAjmcsr11 161MarkusNo ratings yet

- Guilloteaux MotivatingLanguageLearners 2008Document24 pagesGuilloteaux MotivatingLanguageLearners 2008Macs PorNo ratings yet

- 1995 Riding Fowell LevyDocument8 pages1995 Riding Fowell LevyNanda adin NisaNo ratings yet

- METLIT.1.Characterizing Educational Design ResearchDocument27 pagesMETLIT.1.Characterizing Educational Design ResearchWhindi Widhiyanti SNo ratings yet

- A Contextualized Approach To Curriculum and InstructionDocument8 pagesA Contextualized Approach To Curriculum and InstructionClara Panay100% (1)

- The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning In and Across the DisciplinesFrom EverandThe Scholarship of Teaching and Learning In and Across the DisciplinesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Interactional Research Into Problem-Based LearningFrom EverandInteractional Research Into Problem-Based LearningSusan M. BridgesNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Teachers’ Questions and Tasks to Develop Reading Comprehension: The Application of the Cogaff Taxonomy in Developing Critical Thinking Skills in MalaysiaFrom EverandAn Investigation of Teachers’ Questions and Tasks to Develop Reading Comprehension: The Application of the Cogaff Taxonomy in Developing Critical Thinking Skills in MalaysiaNo ratings yet

- Thinking as Researchers Innovative Research Methodology Content and MethodsFrom EverandThinking as Researchers Innovative Research Methodology Content and MethodsNo ratings yet

- Uncovering Student Ideas in Physical Science, Volume 1: 45 New Force and Motion Assessment ProbesFrom EverandUncovering Student Ideas in Physical Science, Volume 1: 45 New Force and Motion Assessment ProbesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Oxford LanguageLearningMotivation 1994Document18 pagesOxford LanguageLearningMotivation 1994Macs PorNo ratings yet

- LearnerMotivationFramework2 26 14EVMSDocument21 pagesLearnerMotivationFramework2 26 14EVMSMacs PorNo ratings yet

- Veenman PerceivedProblemsBeginning 1984Document37 pagesVeenman PerceivedProblemsBeginning 1984Macs PorNo ratings yet

- Directed Motivational Currents A Case Study of EFL Students in A CostaDocument14 pagesDirected Motivational Currents A Case Study of EFL Students in A CostaMacs PorNo ratings yet

- Guilloteaux MotivatingLanguageLearners 2008Document24 pagesGuilloteaux MotivatingLanguageLearners 2008Macs PorNo ratings yet

- The Anatomy of Directed Motivational Currents Exploring Intense and EnduringDocument46 pagesThe Anatomy of Directed Motivational Currents Exploring Intense and EnduringMacs PorNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae - SUDHIR GUDURIDocument8 pagesCurriculum Vitae - SUDHIR GUDURIsudhirguduruNo ratings yet

- Noob's Character Sheet 2.3 (Cypher System)Document4 pagesNoob's Character Sheet 2.3 (Cypher System)Pan100% (1)

- El Poder de La Innovación - Contrate Buenos Empleados y Déjelos en PazDocument27 pagesEl Poder de La Innovación - Contrate Buenos Empleados y Déjelos en PazJuan David ArangoNo ratings yet

- Manual de Instruções Marantz SR-7500 DFU - 00 - CoverDocument56 pagesManual de Instruções Marantz SR-7500 DFU - 00 - CoverAntonio VidalNo ratings yet

- Incarcerated Vaginal Pessary - A Report of Two CasesDocument3 pagesIncarcerated Vaginal Pessary - A Report of Two CasesIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Afante Louie Anne E. Budgeting ProblemsDocument4 pagesAfante Louie Anne E. Budgeting ProblemsKyla Kim AriasNo ratings yet

- DEVELOPMENT BANK OF RIZAL vs. SIMA WEIDocument2 pagesDEVELOPMENT BANK OF RIZAL vs. SIMA WEIelaine bercenioNo ratings yet

- Activa Product ImprovementsDocument17 pagesActiva Product ImprovementsadityatfiNo ratings yet

- Boysen PlexibondDocument3 pagesBoysen PlexibondlimbadzNo ratings yet

- 3.32 Max Resources Assignment Brief 2Document3 pages3.32 Max Resources Assignment Brief 2Syed Imam BakharNo ratings yet

- Learner's Development Assessment HRGDocument5 pagesLearner's Development Assessment HRGChiela BagnesNo ratings yet

- Solo 1-MathDocument3 pagesSolo 1-Mathapi-168501117No ratings yet

- Brigham Chap 11 Practice Questions Solution For Chap 11Document11 pagesBrigham Chap 11 Practice Questions Solution For Chap 11robin.asterNo ratings yet

- Top Five Recycling ActivitiesDocument4 pagesTop Five Recycling Activitiesdsmahmoud4679No ratings yet

- REFLECTION Paper About Curriculum and Fishbowl ActivityDocument1 pageREFLECTION Paper About Curriculum and Fishbowl ActivityTrisha Mae BonaobraNo ratings yet

- Bagaimana Pendalaman Keuangan Dan Cadangan Devisa Mempengaruhi Stabilitas Nilai Tukar Di NEGARA EMERGING MARKET? (Pendekatan Panel ARDL)Document9 pagesBagaimana Pendalaman Keuangan Dan Cadangan Devisa Mempengaruhi Stabilitas Nilai Tukar Di NEGARA EMERGING MARKET? (Pendekatan Panel ARDL)Yanri DayaNo ratings yet

- Bhs IndonesiaDocument3 pagesBhs IndonesiaBerlian Aniek HerlinaNo ratings yet

- Livspace Interior Expo, HulkulDocument35 pagesLivspace Interior Expo, HulkulNitish KumarNo ratings yet

- Frozen ShoulderDocument44 pagesFrozen ShoulderEspers BluesNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Ugong Pasig National High SchoolDocument12 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Ugong Pasig National High SchoolJOEL MONTERDENo ratings yet

- Beginners Guide To Voip WP 2016Document13 pagesBeginners Guide To Voip WP 2016sharnobyNo ratings yet

- (Download PDF) Digital Media Steganography Principles Algorithms and Advances 1St Edition Mahmoud Hassaballah Editor Online Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument43 pages(Download PDF) Digital Media Steganography Principles Algorithms and Advances 1St Edition Mahmoud Hassaballah Editor Online Ebook All Chapter PDFdorothy.parkhurst152100% (15)

- April 6, 2020: Laboratory Assignment: TrematodesDocument9 pagesApril 6, 2020: Laboratory Assignment: Trematodesthe someoneNo ratings yet

- 5 Books Recommended by Paul Tudor JonesDocument4 pages5 Books Recommended by Paul Tudor Jonesjackhack220No ratings yet

- Design Specifications of PV-diesel Hybrid SystemDocument7 pagesDesign Specifications of PV-diesel Hybrid Systemibrahim salemNo ratings yet

- 2.2.5 Lab - Becoming A Defender - ILMDocument2 pages2.2.5 Lab - Becoming A Defender - ILMhazwanNo ratings yet

- Examination Calendar 2022 23Document4 pagesExamination Calendar 2022 23shital yadavNo ratings yet

Drnyei MotivationMotivatingForeign 1994

Drnyei MotivationMotivatingForeign 1994

Uploaded by

Macs PorOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Drnyei MotivationMotivatingForeign 1994

Drnyei MotivationMotivatingForeign 1994

Uploaded by

Macs PorCopyright:

Available Formats

Motivation and Motivating in the Foreign Language Classroom

Author(s): Zoltán Dörnyei

Source: The Modern Language Journal , Autumn, 1994, Vol. 78, No. 3 (Autumn, 1994),

pp. 273-284

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the National Federation of Modern Language Teachers

Associations

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/330107

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/330107?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

National Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations and Wiley are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Modern Language Journal

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Motivation and Motivating in the

Foreign Language Classroom

ZOLTAN DORNYEI

Department of English, E6tv6s University

1146 Budapest, Ajt6si Diirer sor 19, Hungary

Email: dornyei@ludens.elte.hu

MOTIVATION IS ONE OF THE MAIN DETER- tion research, which would be consistent with

minants of second/foreign language (L2) the perceptions of practising teachers and

learning achievement and, accordingly, the last which would also be in line with the current

three decades have seen a considerable amount results of mainstream educational psychologi-

of research that investigates the nature andcal research.

role of

motivation in the L2 learning process. Much It must

of be noted that Gardner's (32) motiva-

tionby

this research has been initiated and inspired theory does include an educational dimen-

sion and that the motivation test he and his

two Canadian psychologists, Robert Gardner

and Wallace Lambert (see 34), who, together

associates developed, the Attitude/Motivation

Test Battery (AMTB) (31), contains several

with their colleagues and students, grounded

motivation research in a social psychological

items focusing on the learner's evaluation of th

framework (for recent summaries, see 33;classroom

35). learning situation. However, the

Gardner and his associates also established sci- main emphasis in Gardner's model-and the w

entific research procedures and introduced

it has been typically understood-is on genera

standardised assessment techniques and instru- motivational components grounded in the so-

ments, thus setting high research standards cialand

milieu rather than in the foreign languag

bringing L2 motivation research to maturity. classroom. For example, the AMTB contains

Although Gardner's motivation construct section

didin which students' attitudes toward the

not go unchallenged over the years (see 2; language

44), teacher and the course are tested.

it was not until the early 1990s that a marked This may be appropriate for measurement pur-

shift in thought appeared in papers on L2 poses,

mo- but the data from this section do not

tivation as researchers tried to reopen the provide

re- a detailed enough description of the

search agenda in order to shed new light classroom

on the dimension to be helpful in generat-

subject (e.g., 10; 19; 51; 52). The main problem

ing practical guidelines. As Gardner and MacIn-

with Gardner's social psychological approach tyre (35) recently stated concerning the learn-

appeared to be, ironically, that it was tooing situation-specific section of the AMTB,

influ-

ential. In Crookes and Schmidt's words, it was "attention is directed toward only two targets,

"so dominant that alternative concepts have largely because they are more generalisable

not been seriously considered" (p. 501). This across different studies" (p. 2). Finally, Gard-

resulted in an unbalanced picture, involving a ner's motivation construct does not include de-

conception that was, as Skehan put it, "limited tails on cognitive aspects of motivation to learn,

compared to the range of possible influenceswhereas this is the direction in which educa-

that exist" (52: p. 280). While acknowledging tional psychological research on motivation ha

unanimously the fundamental importance ofbeen moving during the last fifteen years.

the Gardnerian social psychological model, re- The purpose of this paper-following Crooke

searchers were also calling for a more prag-and Schmidt's and Skehan's initiative-is to

matic, education-centred approach to motiva- help foster further understanding of L2 mo

tion from an educational perspective. A nu

ber of relevant motivational components (m

The Modern Language Journal, 78, iii (1994) of them largely unexploited in L2 research)

0026-7902/94/273-284 $1.50/0

C1994 The Modern LanguageJournal be described, and these will then be integr

into a multilevel L2 motivation construct. In

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

274 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

addition, a set of practical stinct, drive, arousal, need,

guidelines on and howon personality

to

apply the research resultstraits to likeactual teaching

anxiety and will and

need for achievement,

be formulated; I believemore that the

recently question

on cognitive appraisals ofof

success

how to motivate students is an area on which L2 and failure, ability, self-esteem, etc. (53; 54).

motivation research has not placed sufficient L2 learning presents a unique situation due

emphasis in the past. to the multifaceted nature and role of language.

Interestingly, a very recent paper by Oxford It is at the same time: a) a communication coding

and Shearin sets out to pursue similar goals system

to that can be taught as a school subject,

those of the current author, by discussing b) mo-an integral part of the individual's identity in-

tivational theories from different branches of volved in almost all mental activities, and also

psychology--general, industrial, educational,

c) the most important channel of social organisation

embedded in the culture of the community

and cognitive developmental psychology-and

where it is used. Thus, L2 learning is more com-

by integrating them into an expanded theoreti-

plex than simply mastering new information

cal framework that has practical instructional

implications. This very comprehensive and andin-

knowledge; in addition to the environmen-

sightful study, together with the workstal and cognitive factors normally associated

cited

above and the author's current discussion,with

may learning in current educational psychol-

provide a firmer basis for new directions ogy,

of re-it involves various personality traits and so-

search in L2 motivation. cial components. For this reason, an adequate

L2 motivation construct is bound to be eclectic,

At the outset, I would like to acknowledge

once again the seminal work of Robert Gardner bringing together factors from different psy-

and his colleagues. Gardner's theory has pro- chological fields.

foundly influenced my thinking on this subject, Coming from Canada, where language learn-

and I share Oxford and Shearin's assertion that: ing is a featured social issue-at the crux of the

The current authors do not intend to overturn the relationship between the Anglophone and

Francophone

ideas nor denigrate the major contributions of re- communities--Gardner and

searchers such as Gardner, Lambert, Lalonde, and Lambert were particularly sensitive to the social

others, who powerfully brought motivational issues dimension of L2 motivation. The importance of

to the attention of the L2 field. We want to main- this dimension is not restricted to Canada. If we

consider that the vast majority of nations in the

tain the best of the existing L2 learning motivation

theory and push its parameters outward (p. 13).world are multicultural, and most of these are

Indeed, there will be an attempt in this papermultilingual,

to and that there are more bilinguals

in the world than there are monolinguals (32),

integrate the social psychological constructs

we cannot fail to appreciate the immense social

postulated by Gardner, Clement, and their asso-

ciates into the proposed new framework of relevance

L2 of language learning worldwide.

motivation. Integrativeness and Instrumentality. Gardner's

motivation construct has often been under-

stood as the interplay of two components, inte-

THE SOCIAL DIMENSION OF L2

grative and instrumental motivations. The for-

MOTIVATION

mer is associated with a positive disposition

towardhas

One recurring question in recent papers the L2 group and the desire to interact

been how "social" a L2 motivation construct with and even become similar to valued mem-

should be and what the relationship between

bers of that community. The latter is related to

social attitudes and motivation is. To start with,

the potential pragmatic gains of L2 proficiency,

it must be realised that "attitudes" and "motiva-such as getting a better job or a higher salary. It

tion" tend not to be used together in the psy- must be noted, however, that Gardner's theory

chological literature as they are considered to and test battery are more complex and reach

be key terms of different branches of psychol-beyond the instrumental/integrative dichot-

ogy. "Attitude" is used in social psychology and omy. As Gardner and MacIntyre state, "The im-

sociology, where action is seen as the function portant point is that motivation itself is dy-

of the social context and the interpersonal/ namic. The old characterization of motivation

intergroup relational patterns. Motivational in terms of integrative vs. instrumental orienta-

psychologists, on the other hand, have been tions is too static and restricted" (p. 4).

looking for the motors of human behaviour in The popularity of the integrative-instru-

the individual rather than in the social being, mental system is partly due to its simplicity and

focusing traditionally on concepts such as in- intuitively convincing character, but partly also

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Zoltdn D6rnyei 275

to the fact that broadly

ment that the most de

pressing difficulty motiva-

affective" and "pragmatic-

tion researchers face is that of "clarifying the

mensions doorientation-context

usually links that exist. There

emerg

studies of motivation. However, in the last dec- would seem to be a wider range of orientatio

ade, investigations have shown that these dimen- here than was previously supposed, and there

sions cannot be regarded as straightforward uni- considerable scope to investigate different con

versals, but rather as broad tendencies-or textual circumstances (outside Canada!) by

varying the L1-L2 learning relationship in dif-

subsystems- comprising context-specific clus-

ters of loosely related components. As Gardner

ferent ways" (p. 284). To put it simply, the exact

nature

and MacIntyre concluded, it is simplistic not to of the social and pragmatic dimensions

recognise explicitly the fact that sociocultural

of L2 motivation is always dependent on who

context has an overriding effect on all aspects

learns what languages where.

of the L2 learning process, including motivation.

Clement and Kruidenier found in their Cana- FURTHER COMPONENTS OF L2 MOTIVATION

dian research that in addition to an instrumental

Although the majority of past research

orientation, three other distinct general orienta-

tions to learn a L2 emerged, namely knowledge,tended to focus on the social and pragm

dimensions of L2 motivation, some studies have

friendship, and travel orientations, which had tradi-

attempted to extend the Gardnerian construct

tionally been lumped together in integrativeness.

Moreover, when L2 was a foreign rather than by aadding new components, such as intrinsic/

extrinsic motivation (9; 10), intellectual curi-

second language (i.e., learners had no direct

osity (41), attribution about past successes/

contact with the L2 community), a fourth, socio-

cultural, orientation was also identified. failures (26; 52), need for achievement (26),

self-confidence (13, 15, 40), and classroom goal

Investigating young adult learners in a for-

structures (38), as well as various motives re-

eign language learning situation in Hungary,

D6rnyei (26) identified three loosely related lated

di- to learning situation-specific variables

such as classroom events and tasks, classroom

mensions of a broadly conceived integrative

motivational subsystem: 1) interest in foreignclimate

lan- and group cohesion, course content

and

guages, cultures, and people (which can be associ-teaching materials, teacher feedback, and

grades and rewards (9-11; 14; 19; 25; 37; 38; 41;

ated with Clement and Kruidenier's "socio-

46; 51;one's

cultural orientation"); 2) desire to broaden 52). In the following discussion, I will

give an overview

view and avoid provincialism (cf., Clement and of these motivational areas and

then outline a L2 motivation construct that at-

Kruidenier's "knowledge orientation"); and

tempts

3) desire for new stimuli and challenges to integrate these components.

(sharing

Intrinsic/Extrinsic Motivation and Related Theo-

much in common with Cl6ment and Kruidenier's

"friendship" and "travel orientations"). A ries. One of the most general and well-known

distinctions in motivation theories is that be-

fourth dimension, the desire to integrate into a new

tween intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Extrin-

community (cf., "travel orientation"), overlapped

with the instrumental motivational subsystem. sically motivated behaviours are the ones that

Investigating secondary school pupils in the the individual performs to receive some extrin-

same context, Clement, D6rnyei, and Noels sic reward (e.g., good grades) or to avoid pun-

found that, in this population, instrumental and ishment. With intrinsically motivated behav-

knowledge orientations clustered together, and they iours the rewards are internal (e.g., the joy of

identified four other distinct orientations, xeno- doing a particular activity or satisfying one's

philic (similar to "friendship orientation"), iden- curiosity).

tification, sociocultural, and English media. In an- Deci and Ryan argue that intrinsic motiva-

other foreign language learning context, tion is potentially a central motivator of the ed-

among American high school students learning ucational process:

Japanese, Oxford and Shearin also found that Intrinsic motivation is in evidence whenever stu-

in addition to integrative and instrumental dents' natural curiosity and interest energise their

orientations, the learners had a number of learning. When the educational environment pro-

other reasons for learning the language, rang-vides optimal challenges, rich sources of stimula-

tion, and a context of autonomy, this motivational

ing from "enjoying the elitism of taking a diffi-

wellspring in learning is likely to flourish (p. 245).

cult language" to "having a private code that

parents would not know" (p. 12). Extrinsic motivation has traditionally been

These studies confirm Skehan's (51) argu-

seen as something that can undermine intrinsic

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

276 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

motivation; several studies have

pointconfirmed that

out that tests and exams can be powerful

students will lose their natural intrinsic interest

proximal motivators in long lasting, continuous

in an activity if they have to do it to meet some behaviours such as language learning; they

extrinsic requirement (as is often the case with function as proximal subgoals and markers of

compulsory readings at school). Brown (10)progress that provide immediate incentive, self-

points out that traditional school settings with inducements, and feedback and that help mo-

their teacher domination, grades and tests, as bilise and maintain effort. Proximal goal-

well as "a host of institutional constraints that setting also contributes to the enhancement of

glorify content, product, correctness, compet- intrinsic interest through favourable, continued

itiveness" tend to cultivate extrinsic motivation involvement in activities and through the satis-

and "fail to bring the learner into a collabora- faction derived from subgoal attainment. At-

tive process of competence building" (p. 388). tainable subgoals can also serve as an important

Recent research on intrinsic/extrinsic mo- vehicle in the development of the students' self-

tivation has shown that under certain circum- confidence and efficacy-two concepts that

will be analysed below.

stances-if they are sufficiently self-determined

and internalised-extrinsic rewards can be com- Oxford and Shearin argue that in order to

bined with, or even lead to, intrinsic motiva- function as efficient motivators, goals should be

tion. The self-determination theory was introduced specific, hard but achievable, accepted by the

by Deci and Ryan as an elaboration of the students, and accompanied by feedback about

intrinsic/extrinsic construct. Self-determi- progress. As the authors conclude, "Goal set-

nation (i.e., autonomy) is seen as a prerequisite

ting can have exceptional importance in stimu-

lating L2 learning motivation, and it is there-

for any behaviour to be intrinsically rewarding.

In the light of this theory, extrinsic motiva-

fore shocking that so little time and energy are

tion is no longer regarded as an antagonistic

spent in the L2 classroom on goal setting"

counterpart of intrinsic motivation but has

(p. 19).

been divided into four types along a continuumCognitive components of motivation. Since the

between self-determined and controlled forms mid-1970s, a cognitive approach has set the di-

of motivation (24): External regulation refers rection

toof motivation research in educational

the least self-determined form of extrinsic mo- psychology. Cognitive theories of motivation

tivation, involving actions for which the locus view

of motivation to be a function of a person'

initiation is external to the person, such as thoughts

re- rather than of some instinct, need,

drive, or state; information encoded and trans-

wards or threats (e.g., teacher's praise or paren-

formed into a belief is the source of action.

tal confrontation). Introjected regulation involves

externally imposed rules that the student ac- In his analysis of current theories of motiva-

cepts as norms that pressure him or her totion, be- Weiner (53) lists three major cognitive

have (e.g., "I must be at school on time," or "I

conceptual systems: attribution theory, learned

should have prepared for class"). Identified regula-

helplessness, and self-efficacy theory. All three con-

tion occurs when the person has come to cern iden-the individual's self-appraisal of what he or

tify with and accept the regulatory processshe can or cannot do, which will, in turn, affect

see-

how he

ing its usefulness. The most developmentally or she strives for achievement in the

advanced form of extrinsic motivation is inte- future. The central theme in attribution theory is

the

grated regulation, which involves regulations study of how causal ascriptions of past fail-

that

are fully assimilated with the individual's ures otherand successes affect future goal expect-

values, needs, and identities. Motives tradi- ancy. For example, failure that is ascribed to

tionally mentioned under instrumental motiva- low ability or to the difficulty of a task decreases

the expectation of future success more than

tion in the L2 literature typically fall under one

failure that is ascribed to bad luck or to a lack of

of the last two categories-identified regula-

tion or integrated regulation-depending on effort. In his exploratory study among Hun-

how important the learner considers the goalgarian

of L2 learners, the current author (26)

identified an independent "attributions about

L2 learning to be in terms of a valued personal

outcome. past failures" component to L2 motivation and

Proximal goal-setting. The theories arguedpresented

that such attributions are particularly

above may suggest that extrinsic significant in foreign

goals such as language learning con-

tests and exams should be avoided as much as texts where "L2 learning failure" is a very com-

mon phenomenon.

possible since they are detrimental to intrinsic

motivation. Bandura and Schunk, however, Learned helplessness refers to a resigned, pessi-

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Zoltan D6rnyei 277

mistic, helpless ing. Individuals

state with a high

that need for achieve-

deve

person wants to ment are interested in excellencebut

succeed for its own feel

sake, tend to initiate achievement

impossible or beyond him activities,

or he

son, that is, thework with probability

heightened intensity at these tasks, of

does not appear and persist

toin the be face of failure. Oxford and

increased

or effort. It is Shearin provide a detailed analysis

a feeling of on how

"I need sim

which, once established,

theories in general might be relevant tois L2 mo-ver

reverse. tivation research, and in an earlier paper (26) I

have argued

Self-efficacy refers to an individual's that in institutional/academic

judgement

of his or her ability to perform contexts,

a specificwhere academic achievement situa-

action.

tions are very

Attributions of past accomplishments salient,

play anneed for achievement will

play a particularly important

important role in developing self-efficacy, but role.

people also appraise efficacy from observa-

tional experiences (e.g., by observing peers), as

MOTIVATIONAL COMPONENTS THAT ARE

well as from persuasion, reinforcement, and

SPECIFIC TO LEARNING SITUATIONS

evaluation by others, especially teachers or par-

ents (e.g., "You can do it!" or "You Since theareend of the 1980s more importa

doing

fine!") (49). Once a strong sensehas ofbeen attached in the

efficacy is L2 motivation litera-

developed, a failure may not have turemuch

to motives related to the learning situation

impact.

Oxford and Shearin emphasise that (e.g., 9-11;

many 14; 19; 25; 37; 38; 51; 52). In order to

stu-

dents do not have an initial belief in their self- grasp the array of variables and processes in-

efficacy and "feel lost in the language class" volved at this level of L2 motivation, it appears

(p. 21); teachers therefore can and should help useful to separate three sets of motivational

them develop a sense of self-efficacy by provid- components (motives and motivational condi-

ing meaningful, achievable, and success- tions): 1) course-specific motivational components

engendering language tasks. concerning the syllabus, the teaching materials,

Self-confidence. Self-confidence-the belief the teaching method, and the learning tasks;

that one has the ability to produce results, ac- 2) teacher-specific motivational components concern-

complish goals or perform tasks competently-- ing the teacher's personality, teaching style,

is an important dimension of self-concept. It feedback, and relationship with the students;

appears to be akin to self-efficacy, but used in a and 3) group-specific motivational components con-

more general sense. Self-confidence was first cerning the dynamics of the learning group.

introduced in L2 literature by Clement (13) to Course-specific motivational components. Based

describe a secondary, mediating motivational on Keller's motivational system-which is par-

process in multi-ethnic settings that affects a ticularly comprehensive and relevant to class-

person's motivation to learn and use a L2. Ac- room learning-Crookes and Schmidt postu-

cording to his conceptualisation, self-confi- late four major motivational factors to describe

dence includes two components, language use L2 classroom motivation: interest, relevance, expect-

anxiety (the affective aspect) and self-eval- ancy, and satisfaction. This framework appears to

uation of L2 proficiency (the cognitive aspect), be particularly useful in describing course-

and is determined by the frequency and quality specific motives.

of interethnic contact (cf., 15; 40). The first category, interest, is related to intrin-

Although self-confidence was originally con- sic motivation and is centred around the indi-

ceptualised with regard to multi-ethnic settings, vidual's inherent curiosity and desire to know

Clement, D6rnyei, and Noels showed that it is a more about him or herself and his or her en-

major motivational subsystem in foreign lan- vironment. Relevance refers to the extent to

guage learning situations as well (i.e., where which the student feels that the instruction is

there is no direct contact with members of the

connected to important personal needs, values,

L2 community). This is in line with the impor-

or goals. At a macrolevel, this component coin-

tance attached to self-efficacy in the educa-

cides with instrumentality; at the level of the

tional psychological literature. learning situation, it refers to the extent to

Need for achievement. A central element ofwhich

clas- the classroom instruction and course

sical achievement motivation theory, needcontent

for are seen to be conducive to achievin

achievement is a relatively stable personality the

traitgoal, that is, to mastering the L2. Expectan

refers to the perceived likelihood of success

that is considered to affect a person's behaviour

is related to the learner's self-confidence and

in every facet of life, including language learn-

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

278 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

performance

self-efficacy at a general level; againstof

at the level external

the standards. Of th

two, the

learning situation, it concerns former should

perceived be dominant. For exam-

task

difficulty, the amount of ple,

effort required,

praise-a the

type of informational feedback-

amount of available assistance and guidance,

should attribute success to effort and ability, im

the teacher's presentation of the

plying task,

that and

similar fa- can be expected i

successes

miliarity with the task type.the future. Praise should

Satisfaction avoid, however, the in-

concerns

clusion of controlling

the outcome of an activity, referring to the com-feedback (e.g., the com

bination of extrinsic rewards such

parison asstudents'

of the praisesuccess

or to the successe

good marks and to intrinsicor

rewards

failures ofsuch

others)as en-

(7). Ames points out tha

joyment and pride. Attainable proximal

social comparison, sub-

which is considered ver

detrimental

goals (as discussed above) are related to primarily

intrinsic motivation, is often im-

to this component. posed in a variety of ways in the classroom, in

Teacher-specific motivationalcluding announcement

components. Per-of grades (sometime

haps the most important teacher-related motive

only the highest and lowest), displays of selecte

has been identified in educational

papers and psychology

achievements, and ability groupin

as affiliative drive (3), whichGroup-specific

refers to motivational

students' components. Class

need to do well in school in room learning

order takes place

to please the within groups a

teacher (or other superordinate figures

organisational like

units; these units are powerful

parents) whom they like socialandentities with a "life Al-

appreciate. of their own," so that

though this desire for teacher group approval

dynamics influence

is an student affects and

extrinsic motive, it is often cognitions (for a review,

a precursor to in-see 30; 50). In addi

trinsic interest (5), as is attested by good tion, group goals and the group's commitmen

teachers whose students become devoted to to these goals do not necessarily coincide with

their subject. those of the individual, but may reinforce or

A second teacher-related motivational com- reduce them.

ponent is the teacher's authority type, that

Withis,respect to L2 motivation, four aspects of

whether he or she is autonomy supportinggroup

or dynamics are particularly relevant:

controlling. Sharing responsibility with stu-

1) goal-orientedness, 2) norm and reward system,

dents, offering them options and choices, let- cohesion, and 4) classroom goal structures.

3) group

ting them have a say in establishing priorities, A group goal is best regarded as a composite of

and involving them in the decision making individual goals, that is, an "end state desired by

enhance student self-determination and intrin- a majority of the group members" (50: p. 351).

sic motivation (23, 24). Groups are typically formed for a purpose, but

A third motivational aspect of the teacher the is

"official goal" may not be the only group

goal and in extreme cases may not be a group

his or her role in direct and systematic socializa-

tion ofstudent motivation (8), that is, whethergoal

he orat all. For example, the goal of a group of

she actively develops and stimulates learners' students may be to have fun rather than to

motivation. There are three main channels for learn. The extent to which the group is attuned

to pursuing its goal (in our case, L2 learning) is

the socialization process: 1) Modelling: teachers,

in their position as group leaders, embodyreferred

the to as goal-orientedness.

"group conscience" and, as a consequence, stu- The group's norm and reward system is one of

dent attitudes and orientations toward learningthe most salient classroom factors that can af-

will be modelled after their teachers, both in fect student motivation. It concerns extrinsic

terms of effort expenditure and orientations of motives that specify appropriate behaviours re-

quired for efficient learning. As has been dis-

interest in the subject. 2) Task presentation: effi-

cient teachers call students' attention to the cussed earlier, extrinsic regulations should be

purpose of the activity they are going to internalised

do, its as much as possible to foster intrin-

potential interest and practical value, and sic motivation.

even Rewards and punishment (typ-

the strategies that may be useful in achieving ically expressed in grades) should give way to

the task, thus raising students' interest group and

norms, which are standards that the ma-

metacognitive awareness. 3) Feedback: this jority of group members agree to and which

proc-

ess carries a clear message about the teacher's become part of the group's value system. In

priorities and is reflected in the students' classes

mo-where, for example, doing home assign-

tivation. There are two types of feedback: ments and preparing for tests conscientiously

infor-

mational feedback, which comments on have compe-not become accepted group norms, bad

tence, and controlling feedback, whichgrades judgesand other punitive measures will not be

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Zoltdn Dornyei 279

efficient in eclectic, multifaceted construct.

getting studentIn order to in-

their home studies. On the other hand, once a tegrate the various components, it appears nec-

norm has been internalised and has become a essary to introduce different levels of motiva-

self-evident pre-condition for the group tion,to

similarly but not in exactly the same way as

function, the group is likely to cope withwas done by Crookes and Schmidt.

devia-

tions by putting pressure on members whoBasedvio- on the research literature presented

late the norm. This may happen through a and the results of Clement, D6rnyei, and

above

Noels's

range of group behaviours-from showing ac- classroom study-in which a tripartite

tive support for teacher's efforts to have L2the

motivation construct emerged comprising

norms observed, to expressing indirectlyintegrative dis- motivation, self-confidence, and the

agreement with and dislike for deviant mem- appraisal of the teaching environment-we may

bers, and even to openly criticising them conceptualise

and a general framework of L2 mo-

putting them in "social quarantine." tivation. This framework consists of three levels:

Group cohesion is the "strength of the relation-the Language Level, the Learner Level, and the

ship linking the members to one another Learning and to Situation Level (see Figure I). The three

the group itself" (30: p. 10). In a meta-analysis,levels coincide with the three basic constituents

Evans and Dion found a consistent positive ofrela-

the L2 learning process (the L2, the L2

tionship between cohesion and group perfor- learner, and the L2 learning environment) and

mance, and the findings of Clement, D6rnyei, also reflect the three different aspects of lan-

and Noels confirmed that perceived group guage

co- mentioned earlier (the social dimension,

hesion is an important motivational component the personal dimension, and the educational

in a L2 learning context. This may be duesubject to the matter dimension).

fact that in a cohesive group, members want Thetomost general level of the construct is the

contribute to group success and the group's Language Level where the focus is on orienta-

goal-oriented norms have a strong influence tions and motives related to various aspects of

over the individual. the L2, such as the culture it conveys, the com-

munity in which it is spoken, and the potential

Classroom goal structures can be competitive, coopera-

usefulness of proficiency in it. These general

tive, or individualistic. In a competitive structure,

students work against each other and only motives

the determine basic learning goals and ex-

best ones are rewarded. In a cooperative situa- plain language choice. In accordance with the

tion, students work in small groups in which Gardnerian approach, this general motiva-

each member shares responsibility for the tional out- dimension can be described by two broad

come and is equally rewarded. In an individu- motivational subsystems, an integrative and an

alistic structure, students work alone, and one's instrumental motivational subsystem, which, as has

probability of achieving a goal or reward is nei- been argued before, consist of loosely related,

ther diminished nor enhanced by a capable context-dependent motives. The integrative

other. There is consistent evidence from pre- motivational subsystem is centred around the

school to graduate school settings that, com- individual's L2-related affective predisposi-

pared to competitive or individualistic learning tions, including social, cultural, and eth-

experiences, the cooperative goal structure is nolinguistic components, as well as a general

more powerful in promoting intrinsic motiva- interest in foreignness and foreign languages.

tion (in that it leads to less anxiety, greater task The instrumental motivational subsystem con-

involvement, and a more positive emotional sists of well-internalised extrinsic motives (iden-

tone), positive attitudes towards the subject tified and integrated regulation) centred

area, and a caring, cohesive relationship with around the individual's future career en-

peers and with the teacher (36; 42). Julkunen deavours (cf., 26).

(38) analysed the effects of these three goal The second level of the L2 motivation con-

structures on L2 motivation and his results sup- struct is the Learner Level, involving a complex of

ported the superiority of cooperative learning. affects and cognitions that form fairly stable

personality traits. We can identify two motiva-

tional components underlying the motivational

SUMMARY OF THE L2 MOTIVATION

CONSTRUCT

processes at this level, need for achievement and self-

confidence, the latter encompassing various as-

The variety of relevant motivation types andlanguage anxiety, perceived L2 compe-

pects of

components described above is in accordance tence, attributions about past experiences, and

with the earlier claim that L2 motivation is an self-efficacy.

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

280 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

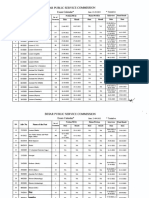

FIGURE I

Components of Foreign Language Learning Motivation

LANGUAGE LEVEL Integrative Motivational Subsystem

Instrumental Motivational Subsystem

LEARNER LEVEL Need for Achievement

Self-Confidence

* Language Use Anxiety

* Perceived L2 Competence

* Causal Attributions

* Self-Efficacy

LEARNING SITUATION LEVEL

Course-Specific Motivational Interest

Components Relevance

Expectancy

Satisfaction

Teacher-Specific Motivational Affiliative Drive

Components Authority Type

Direct Socialization of Motivation

* Modelling

* Task Presentation

* Feedback

Group-Specific Motivational Goal-orientedness

Components Norm & Reward System

Group Cohesion

Classroom Goal Structure

The third level of L2 motivation is the Learn- research (for two excellent overviews, see 6; 39

The reader is also referred to Oxford and

ing Situation Level, made up of intrinsic and ex-

trinsic motives and motivational conditions Shearin's article mentioned above, which con-

tains very useful practical instructional implica-

concerning three areas. 1) Course-specific motiva-

tions of the theories discussed, as well as to

tional components are related to the syllabus, the

Brown's recent book (9), which includes de-

teaching materials, the teaching method, and

tailed

the learning tasks. These are best described bydiscussion on how to capitalise on the

students' intrinsic motivation in the second lan-

the framework of four motivational conditions

proposed by Crookes and Schmidt: interest, rele- guage classroom.

vance, expectancy, and satisfaction. 2) Teacher- It must be emphasised that the following

strategies are not rock-solid golden rules, but

specific motivational components include the affilia-

rather suggestions that may work with one

tive drive to please the teacher, authority type, and

teacher

direct socialization of student motivation (modelling, or group better than another and that

task presentation, and feedback). 3) Group- might work today but not tomorrow as they lose

specific motivational components are made uptheir

of novelty. Nevertheless, such a list provides,

four main components: goal-orientedness, norm in Brophy's words, "a 'starter set' of strategies

to

and reward system, group cohesion, and classroom select from in planning motivational ele-

goal structure.

ments to include in instruction" (p. 48). The

strategies will be organised according to the cat-

HOW TO MOTIVATE L2 LEARNERS

egories introduced in the proposed L2 con-

struct above. As can be expected, most of the

strategies

In this last section, a list of strategies to moti- will concern the Learning Situation

vate language learners will be presented, Level.

draw-Motives belonging to the Language and

ing partly on the author's own experience Learner

and Levels tend to be more generalised and

established and, therefore, do not lend them-

partly on findings in educational psychological

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Zoltdn Dornyei 281

selves as the L2 classroom, to

easily avoiding hypercritical

manipu or pu-

tions. nitive treatment, and applying special anxiety-

Language Level. reducing activities and techniques (for a sum-

mary, see 55).

1) Include a sociocultural component in the L2 syl-

labus by sharing positive L2- related experiences 9) Promote motivation-enhancing attributions by

in class, showing films or TV recordings, play- helping students recognise links between effort

ing relevant music, and inviting interesting na- and outcome; and attribute past failures to con-

tive speaking guests. trollable factors such as insufficient effort (if

this has been the case), confusion about what to

2) Develop learners' cross-cultural awareness system-

do, or the use of inappropriate strategies,

atically by focusing on cross-cultural similarities

rather than to lack of ability, as this may lead to

and not just differences, using analogies to make

the strange familiar, and using "culture teach- learned helplessness.

ing" ideas and activities (such as the ones in-10) Encourage students to set attainable subgoals for

cluded, for example, in 12; 20; 21; 27; 28; 47).themselves that are proximal and specific (e.g.,

learning 200 new words every week). Ideally,

3) Promote student contact with L2 speakers by ar-

ranging meetings with L2 speakers in your these subgoals can be integrated into a person-

alised learning plan for each student.

country; or, if possible, organising school trips

or exchange programs to the L2 community; orLearning Situation Level: Course-specific motiva-

finding pen-friends for your students. tional components.

4) Develop learners' instrumental motivation by dis-11) Make the syllabus of the course relevant by bas-

cussing the role L2 plays in the world and its

ing it on needs analysis, and involving the stu-

dents in the actual planning of the course

potential usefulness both for themselves and

their community. programme.

Learner Level. 12) Increase the attractiveness of the course content

5) Develop students' self-confidence by trusting by using authentic materials that are within stu-

them and projecting the belief that they will dents' grasp; and unusual and exotic supple-

achieve their goal; regularly providing praise, mentary materials, recordings, and visual aids.

encouragement, and reinforcement; making 13) Discuss with the students the choice of teaching

sure that students regularly experience success materials for the course (both textbooks and

and a sense of achievement; helping remove un- supplementary materials), pointing out their

certainties about their competence and self- strong and weak points (in terms of utility, at-

efficacy by giving relevant positive examples tractiveness, and interest).

and analogies of accomplishment; counter- 14) Arouse and sustain curiosity and attention by

balancing experiences of frustration by involv- introducing unexpected, novel, unfamiliar, and

ing students in more favourable, "easier" activ- even paradoxical events; not allowing lessons to

ities; and using confidence-building tasks (for settle into too regular a routine; periodically

example, see 22). breaking the static character of the classes by

6) Promote the students' self-efficacy with regard to changing the interaction pattern and the seat-

achieving learning goals by teaching students ing formation and by making students get up

learning and communication strategies, as well and move from time to time.

as strategies for information processing and 15) Increase students' interest and involvement in the

problem-solving, helping them to develop real- tasks by designing or selecting varied and chal-

istic expectations of what can be achieved in a lenging activities; adapting tasks to the stu-

given period, and telling them about your own dents' interests; making sure that something

difficulties in language learning. about each activity is new or different; includ-

7) Promote favourable self-perceptions of competence ing game-like features, such as puzzles, prob-

in L2 by highlighting what students can do in the lem-solving, avoiding traps, overcoming obsta-

L2 rather than what they cannot do, encouraging cles, elements of suspense, hidden information,

the view that mistakes are a part of learning, etc.; including imaginative elements that will

pointing out that there is more to communica- engage students' emotions; leaving activities

tion than not making mistakes or always find- open-ended and the actual conclusion uncer-

ing the right word, and talking openly about tain; personalising tasks by encouraging stu-

your own shortcomings in L2 (if you are a non- dents to engage in meaningful exchanges, such

native teacher) or in a L3. as sharing personal information; and making

8) Decrease student anxiety by creating a sup- peer interaction (e.g., pair work and group

portive and accepting learning environment in work) an important teaching component.

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

282 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

16) Match difficulty of taskstivation

with by presenting

students' tasks asabilities

learning oppor-

so that students can expect to

tunities to besucceed

valued rather thanifimposed

they de-

put in reasonable effort. mands to be resisted, projecting intensity and

enthusiasm,

17) Increase student expectancy of task raising fulfillment

task interest by connecting

by

familiarising students with the

the task withtask type,

things that suffi-

students already find

ciently preparing them for coping

interesting or hold inwith the out

esteem, pointing task

chal-

content, giving them detailed guidance

lenging or exotic aspects of the about

L2) calling at-

the procedures and strategies that the

tention to unexpected task

or paradoxical re-

aspects of

quires, making the criteria for

routine success

topics, (or

and stating the purposegrad-

and util-

ing) clear and "transparent," ity of the and

task. offering stu-

dents ongoing assistance. 24) Use motivating feedback by making your

feedback informational

18) Facilitate student satisfaction by allowing rather than

stu-control-

ling; giving that

dents to create finished products positive competence

they can feedback,

perform or display, encouraging

pointing out thethem

value of tothe be

accomplishment

proud of themselves afterand not overreacting to aerrors

accomplishing task, (for a summary

taking stock from time to oftime

error correction

of their without

general

generating anxiety

see 55).of what the group

progress, making a wall chart

has learned, and celebrating success.

Group-specific motivational components.

Teacher-specific motivational25)

components.

Increase the group's goal-orientedness by initiat-

ing discussions

19) Try to be empathic, congruent, and with students about the group

accepting;

according to the principles goal(s),

of and asking them from time to time t

person-centred

education, these are the three basic teacher evaluate the extent to which they are approach

characteristics that enhance learning (48). Em-

ing their goal.

pathy refers to being sensitive to students' needs, 26) Promote the internalisation of classroom norm

feelings, and perspectives. Congruence refers by to establishing the norms explicitly right from

the start, explaining their importance and how

the ability to behave according to your true self,

that is, to be real and authentic without hiding

they enhance learning, asking for the student

behind facades or roles. Acceptance refers to agreement,

a and even involving students in for

nonjudgmental, positive regard, acknowledging mulating norms.

each student as a complex human being with27) Help maintain internalised classroom norms by

both virtues and faults. observing them consistently yourself, and no

20) Adopt the role of a facilitator rather thanletting

an any violations go unnoticed.

authority figure or a "drill sergeant," develop- 28) Minimise the detrimental effect of evaluation on

ing a warm rapport with the students. intrinsic motivation by focusing on individual im

provement and progress, avoiding any explici

21) Promote learner autonomy by allowing real

or implicit comparison of students to eac

choices about alternative ways to goal attain-

ment; minimising external pressure and control other, making evaluation private rather than

(e.g., threats, punishments); sharing respon- public, not encouraging student competition,

sibility with the students for organising their and making the final (end of term/year/

time, effort and the learning process; inviting course) grading the product of two-way nego

them to design and prepare activities them- tiation with the students by asking them to ex

selves and promoting peer-teaching; including press their opinion of their achievement in a

project work where students are in charge; and personal interview.

giving students positions of genuine authority. 29) Promote the development of group cohesion an

22) Model student interest in L2 learning by show- enhance intermember relations by creating class-

ing students that you value L2 learning room as a situations in which students can get to

meaningful experience that produces satisfac- know each other and share genuine persona

tion and enriches your life, sharing your per- information (feelings, fears, desires, etc.),

sonal interest in L2 and L2 learning with the organising outings and extracurricular activ-

students, and taking the students' learning ities, and including game-like intergroup com

process and achievement very seriously (since petitions in the course.

showing insufficient commitment yourself is 30) Use cooperative learning techniques by fre-

the fastest way to undermine student motiva- quently including groupwork in the classes in

tion). which the group's-rather than the individ-

23) Introduce tasks in such a way as to stimulate ual's-achievement is evaluated (for L2 teach-

intrinsic motivation and help internalise extrinsic mo- ing-specific guidelines, see 17; 18; 42).

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Zoltdan D6rnyei 283

CONCLUSION 4. Bandura, Albert & Dale Schunk. "Cultivating Com-

petence, Self-Efficacy, and Intrinsic Interest

The intent of this paper was to make L2 mo-

Through Proximal Self-Motivation." Journal of

tivation research more "education-friendly,"

Personality and Social Psychology 41 (1981): 586-98.

that is, "congruent with the concept 5. ofBlumenfeld,

motiva- Phyllis C. "Classroom Learning and

tion that teachers are convinced is critical for Motivation: Clarifying and Expanding Goal

SL [second language] success" (19: p. 502). Theory." Journal of Educational Psychology 84

Drawing on a long succession of research in sec- (1992): 272-81.

ond language acquisition, as well as on impor- 6. Brophy, Jere. "Synthesis of Research on Strategies

tant findings in general and educational psy- for Motivating Students to Learn." Educational

Leadership 45,2 (1987): 40-48.

chology, an attempt was made to outline a 7. - & Thomas L. Good. "Teacher Behavior and

comprehensive motivational construct relevant

Student Achievement." Handbook of Research on

to L2 classroom motivation. This construct

Teaching. Ed. Merlin C. Wittrock. New York

comprises three broad levels, the Language Level,Macmillan, 1986: 328-75.

the Learner Level, and the Learning Situation

8. -Level;

& Neelam Kher. "Teacher Socialization as a

these levels correspond to the three basic con- Mechanism for Developing Student Motivatio

stituents of the L2 learning process (L2, L2

to Learn." The Social Psychology ofEducation-Cu

learner, and L2 learning environment), and rent

re- Research and Theory. Ed. Robert S. Feldma

Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1986: 25

flect the three different aspects of language

88.

(the social dimension, the personal dimension,

9. Brown, H. Douglas. Teaching by Principles. Englew

and the educational subject matter dimension).

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1994.

Based on the components of this model, a num-

10. . "M & Ms for Language Classrooms? An-

ber of practical motivational strategies were

other Look at Motivation." Georgetown University

listed that may help language teachers gain a Table on Language and Linguistics 1990. Ed.

Round

better understanding of what motivates their

James E. Alatis. Washington, DC: Georgetown

students in the L2 classroom. Univ. Press, 1990: 383-93.

Although the proposed division of levels11.of. "Affective Factors in Second Language

motivation appears to be parsimonious, and theLearning." The Second Language Classroom: Direc-

construct integrates many lines of research, it tions

is for the Eighties. Ed. J. E. Alatis, H. B. Altman

at this stage no more than a theoretical possi-& P. M. Alatis. New York: Oxford Univ. Press,

1981: 111-29.

bility because many of its components have

12. Celce-Murcia, Marianne, Zoltin D6rnyei & Sarah

been verified by very little or no empirical re-

Thurrell. "Communicative Competence: A Ped-

search in the L2 field. In fact, only the compo-

agogically Motivated Framework with Content

nents at the Language Level and the self- Specifications" (submitted for publication).

confidence construct at the Learner Level have

13. Clement, Richard. "Ethnicity, Contact and Com-

been analysed systematically, notably by Gard- municative Competence in a Second Lan-

ner, Clement, and their associates. There is guage." Language: Social Psychological Perspectives.

clearly a need for much further research on L2 Ed. H. Giles, W. P. Robinson & P. M. Smith.

motivation; this paper is intended to be part of Oxford: Pergamon, 1980: 147-54.

14. - , Zoltin D6rnyei & Kimberly A. Noels. "Mo-

a discussion that will hopefully result in a more

clearly defined and elaborate model of motiva- tivation, Self-confidence and Group Cohesion

in the Foreign Language Classroom." Language

tion in foreign language learning.

Learning (in press).

15. - & Bastian G. Kruidenier. "Aptitude, Atti-

tude and Motivation in Second Language Pro-

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ficiency: A Test of Clement's Model." Journal of

Language and Social Psychology 4 (1985): 21-37.

16. - & Bastian G. Kruidenier. "Orientations on

1. Ames, Carole. "Classrooms: Goals, Structures and Second Language Acquisition: 1. The Effect

Student Motivation." Journal of Educational Psy- Ethnicity, Milieu, and their Target Langu

chology 84 (1992): 267-71. on their emergence." Language Learning 33

2. Au, Shun Y. "A Critical Appraisal of Gardner's (1983): 273-91.

Social-Psychological Theory of Second- 17. Cooperative Language Learning; A Teacher's Resource

Language (L2) Learning." Language Learning Book. Ed. Carolyn Kessler. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

38 (1988): 75-100. Prentice Hall Regents, 1992.

3. Ausubel, David P., Joseph D. Novak & Helen Hane-

18. Cooperative Learning. Ed. Daniel D. Holt. Washington,

sian. Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View. 2nd DC: Center for Applied Linguistics & ERIC Clear-

ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart, 1978. inghouse on Languages and Linguistics, 1993.

This content downloaded from

134.255.25.148 on Sun, 11 Feb 2024 09:48:10 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

284 The Modern Language Journal 78 (1994)

19. Crookes, Graham & Richard W. Schmidt.

Teaching." "Motiva-

Diss., Univ. of Joensuu. Dissertation

tion: Reopening the Research Agenda."

Abstracts Lan-

52 (1991): 716C.

guage Learning 41 (1991): 469-512.

38. -. Situation- and Task-Specific Motivation in For-

20. Culture Bound. Ed. Joyce M. Valdes.Learning

eign-Language Cambridge:and Teaching. Joensuu:

Cambridge Univ. Press, 1986.Univ. of Joensuu, 1989.

39. Keller,

21. Damen, Louise. Culture Learning: TheJohnFifth

M. "Motivational

Dimension Design of Instruc-

in the Language Classroom. Reading, MA:

tion." Instructional Addi-

Design Theories and Models: An

son-Wesley, 1987. Overview of their Current Status. Ed. C. M. Reig-

22. Davies, Paul & Mario Rinvolucri. The Confidence

elruth. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1983:

Book. London: Longman, 1990. 383-434.

23. Deci, Edward L. & Richard 40. M.

Labrie, Normand Intrinsic

Ryan. & Richard Clement.

Mo- "Eth-

tivation and Self-Determination nolinguistic in Human Vitality, Self-Confidence and Sec-

Behavior

New York: Plenum, 1985. ond Language Proficiency: An Investigation."

24. -, Robert J. Vallerand, Luc G. Pelletrier & Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development

Richard M. Ryan. "Motivation and Education: 7 (1986): 269-82.

The Self-Determination Perspective." Educa- 41. Laine, Eero J. "Foreign Language Learning Mo-

tional Psychologist 26 (1991): 325-46. tivation: Old and New Variables." Proceedings of

25. D6rnyei, Zoltan. "Analysis of Motivation Compo- the 5th Congress of lAssociation internationale de lin-

nents in Foreign Language Learning." Paper, guistique appliquee. Ed. Jean-Guy Savard & Lorne

9th World Congress of Applied Linguistics, Laforge. Quebec: Les Presses de l'Universit?

Thessaloniki-Halkidiki, Greece, April 1990 Laval, 1981: 302-12.

[ERIC DOC ED 323 810]. 42. McGroarty, Mary. "Cooperative Learning and Sec-

26. -. "Conceptualizing Motivation in Foreign- ond Language Acquisition." Cooperative Learning.

Language Learning." Language Learning 40 Ed. Daniel D. Holt. Washington, DC: Center for

(1990): 45-78. Applied Linguistics & ERIC Clearinghouse on

27. - & Sarah Thurrell. "Teaching Conversa- Languages and Linguistics, 1993: 19-46.

tional Skills Intensively: Course Content and 43. Milleret, Margo. "Cooperative Learning in the

Rationale." ELTJournal 48 (1994): 40-49. Portuguese-for- Spanish-Speakers Classroom."

28. - & Sarah Thurrell. Conversation and Dialogues Foreign Language Annals 25 (1992): 435-40.

in Action. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall, 44. Oller, John W. Jr. "Can Affect Be Measured?"

1992. IRAL 19 (1981): 227-35.

29. Evans, Charles R. & Kenneth L. Dion. "Group 45. Oxford, Rebecca & Jill Shearin. "Language

Cohesion and Performance; A Meta-Analysis." Learning Motivation: Expanding the Theoreti-

Small Group Research 22 (1991): 175-86. cal Framework." Modern Language Journal 78

30. Forsyth, Donelson R. Group Dynamics. 2nd ed. Pa- (1994): 12-28.

cific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole, 1990. 46. Ramage, Katherine. "Motivational Factors and

31. Gardner, Robert C. The Attitude/Motivation Test Bat- Persistence in Foreign Language Study." Lan-

tery: Technical Report. London, ON: Univ. of West- guage Learning 40 (1990): 189-219.

ern Ontario, 1985. 47. Robinson, Gail L. Crosscultural Understanding. He-

32. -. Social Psychology and Second Language Learn- mel Hempstead: Prentice Hall, 1988.

ing: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation. London: 48. Rogers. Carl. Freedom to Learn for the 80's. Columbus,

Edward Arnold, 1985. OH: Merrill, 1983.

33. - & Richard Clment. "Social Psychological 49. Schunk, Dale H. "Self-Efficacy and Academic Mo-