Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students' Active Procrastination

The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students' Active Procrastination

Uploaded by

fatma zülal kullukçuCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Barry 2007 Motivating The RELUCTANT STUDENTDocument6 pagesBarry 2007 Motivating The RELUCTANT STUDENTInês Coelho100% (1)

- Corsi Block Tapping TestDocument20 pagesCorsi Block Tapping TestHarshita JainNo ratings yet

- Essential Readings in Problem-Based Learning: Exploring and Extending the Legacy of Howard S. BarrowsFrom EverandEssential Readings in Problem-Based Learning: Exploring and Extending the Legacy of Howard S. BarrowsNo ratings yet

- G4 Q1 W5 DLLDocument7 pagesG4 Q1 W5 DLLMark Angel MorenoNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Conversations: Challenging Habits of ThoughtFrom EverandInterdisciplinary Conversations: Challenging Habits of ThoughtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Schraw, Wadkins, and Olafson (2007) - A Grounded Theory of Academic Procrastination PDFDocument14 pagesSchraw, Wadkins, and Olafson (2007) - A Grounded Theory of Academic Procrastination PDFMireille KirstenNo ratings yet

- Development of An Academic Procrastinati PDFDocument10 pagesDevelopment of An Academic Procrastinati PDFLienel Mitsuna LacabaNo ratings yet

- Why Students Procrastinate - A Qualitative ApproachDocument17 pagesWhy Students Procrastinate - A Qualitative ApproachjoseanerezNo ratings yet

- Hensley Psychology ProcrastinationDocument8 pagesHensley Psychology ProcrastinationTrisztán AranyNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument12 pagesChapter ITom NicolasNo ratings yet

- Understanding Procrastination A Case of A Study SKDocument19 pagesUnderstanding Procrastination A Case of A Study SKDhatri shuklaNo ratings yet

- Ba Harrison J 2014Document48 pagesBa Harrison J 2014Anissa RizkyNo ratings yet

- K B 02 Scielzo McCloskyScielzoDocument42 pagesK B 02 Scielzo McCloskyScielzojyothi swarupNo ratings yet

- Ej 915928Document20 pagesEj 915928Nanang HardiansyahNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Essay 2Document10 pagesLiterature Review of Essay 2Vasu patelNo ratings yet

- PR2-RRL Bonifacio Group4 CuriosityDocument2 pagesPR2-RRL Bonifacio Group4 CuriosityFoamy Cloth BlueNo ratings yet

- Cavusoglu 2015Document10 pagesCavusoglu 2015shwethambarirameshNo ratings yet

- Attribution As A Predictor of Procrastination in Online Graduate StudentsDocument19 pagesAttribution As A Predictor of Procrastination in Online Graduate StudentsТеодора ДелићNo ratings yet

- Argumentation & Discussion 1Document6 pagesArgumentation & Discussion 1AryaNo ratings yet

- ProkrastinasiDocument12 pagesProkrastinasiYuli LasmiatiNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument38 pagesUntitledNorelie AbapoNo ratings yet

- Academic Interventions For Academic Procrastination: A Review of The LiteratureDocument15 pagesAcademic Interventions For Academic Procrastination: A Review of The LiteratureGio SalupanNo ratings yet

- Avaliação The Measurement of Student Engagement - A Comparative Analysis of Various MethodsDocument20 pagesAvaliação The Measurement of Student Engagement - A Comparative Analysis of Various MethodsTiagoRodriguesNo ratings yet

- Academic Probation, Time Management, and Time Use in A College Success CourseDocument20 pagesAcademic Probation, Time Management, and Time Use in A College Success CourseFabiano DantasNo ratings yet

- Correlates of Academic ProcrastinationDocument10 pagesCorrelates of Academic ProcrastinationLoquias RJNo ratings yet

- Lin 2014Document20 pagesLin 2014Alimatu FatmawatiNo ratings yet

- Studie Ejunju LeeDocument11 pagesStudie Ejunju LeeuincomNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Online Graduate Students' Motivation and Self-Regulation On Academic ProcrastinationDocument17 pagesThe Impact of Online Graduate Students' Motivation and Self-Regulation On Academic ProcrastinationNanang HardiansyahNo ratings yet

- Luke Ranieri 17698506 Assignment 1 Researching Teaching and LearningDocument4 pagesLuke Ranieri 17698506 Assignment 1 Researching Teaching and Learningapi-486580157No ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practices For Children, Youth, and Young Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive ReviewDocument17 pagesEvidence-Based Practices For Children, Youth, and Young Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive ReviewCristinaNo ratings yet

- 2016-Zoupidis Et Al.-PrimariaDocument20 pages2016-Zoupidis Et Al.-PrimariaEsther MarinNo ratings yet

- 72 HFHBDocument10 pages72 HFHBNatasyaNo ratings yet

- Jaber and Hammer 2016 Learning To Feel Like A ScientistDocument32 pagesJaber and Hammer 2016 Learning To Feel Like A ScientistrodrigohernandezNo ratings yet

- Tan E-Lynn Sample Ethics ProposalDocument17 pagesTan E-Lynn Sample Ethics ProposalThiban Raaj100% (1)

- Running Head: PRE-PROPOSAL DRAFT 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: PRE-PROPOSAL DRAFT 1Brenda Lee MoralesNo ratings yet

- Lee 2005 Pro CR StinationDocument11 pagesLee 2005 Pro CR StinationalgiNo ratings yet

- Towards A Better Understanding of The ST PDFDocument7 pagesTowards A Better Understanding of The ST PDFtesfayergsNo ratings yet

- Exploring Relationships Between Procrastination, Perfectionism, Self-Forgiveness and Academic Grade: A Path Analysis.Document40 pagesExploring Relationships Between Procrastination, Perfectionism, Self-Forgiveness and Academic Grade: A Path Analysis.Beth RapsonNo ratings yet

- Expectancy Value InterventionsDocument6 pagesExpectancy Value Interventionsapi-350693115No ratings yet

- Explaining Newton's Laws of Motion: Using Student Reasoning Through Representations To Develop Conceptual UnderstandingDocument26 pagesExplaining Newton's Laws of Motion: Using Student Reasoning Through Representations To Develop Conceptual UnderstandingYee Jiea PangNo ratings yet

- Genderand Age Differencesin Procrastination CangialosiDocument17 pagesGenderand Age Differencesin Procrastination CangialosielegadoNo ratings yet

- Past Science CourseworkDocument5 pagesPast Science Courseworkjxaeizhfg100% (2)

- Chapter 5 ResearchDocument4 pagesChapter 5 ResearchMark Virgil P Tubalhin100% (1)

- Academic Satisfaction and Its Relationship To Internal Locus of Control Among Students of Najran UniversityDocument5 pagesAcademic Satisfaction and Its Relationship To Internal Locus of Control Among Students of Najran UniversityMar Jory del Carmen BaldoveNo ratings yet

- Academic Satisfaction and Its Relationship To Internal Locus of Control Among Students of Najran UniversityDocument5 pagesAcademic Satisfaction and Its Relationship To Internal Locus of Control Among Students of Najran UniversitySteeven ParubrubNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Open Inquiry Performances of HighDocument16 pagesDynamic Open Inquiry Performances of HighNadea NovasarasetaNo ratings yet

- Experiences of College Students With Psychological Disabilities: The Impact of Perceptions of Faculty Characteristics On Academic AchievementDocument11 pagesExperiences of College Students With Psychological Disabilities: The Impact of Perceptions of Faculty Characteristics On Academic AchievementCoordinacionPsicologiaVizcayaGuaymasNo ratings yet

- On The Psyhology of The Subject PoolDocument24 pagesOn The Psyhology of The Subject PoolCaryl Mae BocadoNo ratings yet

- PR 2 - Lindog MARCH 2024 (Body)Document42 pagesPR 2 - Lindog MARCH 2024 (Body)villanuevadimple91No ratings yet

- Academic Procrastination, Self Efficacy and Anxiety of StudentsDocument7 pagesAcademic Procrastination, Self Efficacy and Anxiety of Studentscharvi didwania100% (3)

- Assignment 2Document12 pagesAssignment 2api-485956198No ratings yet

- Mind The Gap! Students' Use of Exemplars and Detailed Rubrics As Formative AssessmentDocument21 pagesMind The Gap! Students' Use of Exemplars and Detailed Rubrics As Formative AssessmentPhu NguyenNo ratings yet

- Development and Validation of A 2x2 Mode PDFDocument39 pagesDevelopment and Validation of A 2x2 Mode PDFMariano DhinzkieeNo ratings yet

- Academic Procrastination and The Performance of Graduate-Level Cooperative Groups in Research Methods CoursesDocument20 pagesAcademic Procrastination and The Performance of Graduate-Level Cooperative Groups in Research Methods CoursesMiko BristolNo ratings yet

- Final ResearchDocument6 pagesFinal Researchelechar morenoNo ratings yet

- Report2 Wan RongDocument11 pagesReport2 Wan RongnfwahidahNo ratings yet

- Article1424941613 - Taura Et AlDocument7 pagesArticle1424941613 - Taura Et AlI Ketut SuenaNo ratings yet

- Procrastination and Academic PerformancesDocument45 pagesProcrastination and Academic Performancesadrianelindog02No ratings yet

- Student Voices Following Fieldwork FailureDocument14 pagesStudent Voices Following Fieldwork FailureSergioNo ratings yet

- Academic Procrastination and Factors ContributingDocument12 pagesAcademic Procrastination and Factors ContributingAldi kristiantoNo ratings yet

- FINALDocument117 pagesFINALAvrielle Haven JuarezNo ratings yet

- JR I ArticleDocument19 pagesJR I ArticleaneelaNo ratings yet

- Faculty Development and Student Learning: Assessing the ConnectionsFrom EverandFaculty Development and Student Learning: Assessing the ConnectionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Reading Assessment Behavioral Checklist - Form 2Document1 pageReading Assessment Behavioral Checklist - Form 2farnaida kawitNo ratings yet

- The Cognitive Model: Beck and EllisDocument13 pagesThe Cognitive Model: Beck and Ellismohammad alaniziNo ratings yet

- Annurev Neuro 101222 110632Document20 pagesAnnurev Neuro 101222 110632Kama AtretkhanyNo ratings yet

- Task 2 - Group Oral PresentationDocument6 pagesTask 2 - Group Oral PresentationBI2-0620 Siti Nurshahirah Binti Mohamad AzmanNo ratings yet

- AI AutoDocument16 pagesAI Autoمحمد أحمدو اليعقوبيNo ratings yet

- Lecture Bloom TaxonomyDocument5 pagesLecture Bloom TaxonomyAnne BautistaNo ratings yet

- Principles 6-8Document28 pagesPrinciples 6-8Paula García GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Brochure CMU-DELE 03-05-2023 V12Document12 pagesBrochure CMU-DELE 03-05-2023 V12Lucas Fernandes LuzNo ratings yet

- SED LING 2 Activity 2Document3 pagesSED LING 2 Activity 2Sylvia DanisNo ratings yet

- Pagina 1 y 2. 1 Copia. Pagina 3. 25 CopiasDocument3 pagesPagina 1 y 2. 1 Copia. Pagina 3. 25 Copiasanalisalazar390No ratings yet

- Etiology and Recovery of Neuromuscular Fatigue Following Sim..Document1 pageEtiology and Recovery of Neuromuscular Fatigue Following Sim..Martín Seijas GonzálezNo ratings yet

- SS3 Culmination: The Best of MEDocument34 pagesSS3 Culmination: The Best of MEMartine Andrei Macado SabandoNo ratings yet

- Tacit & Explicit KnowlwdgeDocument12 pagesTacit & Explicit KnowlwdgeJeswin P UNo ratings yet

- AsynchornousDocument1 pageAsynchornousjohn paul PatronNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism CognitivismDocument2 pagesBehaviorism CognitivismIan PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Adjuster Training Modul FIDocument6 pagesAdjuster Training Modul FIFaisal AzharNo ratings yet

- Semantics - NG NghĩaDocument2 pagesSemantics - NG NghĩaK60 Trần Đoan TrangNo ratings yet

- 영교론 Glossary 모음Document12 pages영교론 Glossary 모음Seunghye ParkNo ratings yet

- Simple Reaction Time - Lab ReportDocument7 pagesSimple Reaction Time - Lab ReportRUFINO, Aira JheanneNo ratings yet

- Physical Self and DevelopmentDocument2 pagesPhysical Self and Developmentvictoria vistanNo ratings yet

- Understanding EmotionsDocument9 pagesUnderstanding EmotionsBuat DaftardaftarNo ratings yet

- Basics of Generative AIDocument6 pagesBasics of Generative AIneerajsingh2452No ratings yet

- الفضاءات الباقية في الذاكرةDocument24 pagesالفضاءات الباقية في الذاكرةhl7694016No ratings yet

- A Self-Efficacy Theory Explanation For The Management of Remote Workers in Virtual OrganizationsDocument20 pagesA Self-Efficacy Theory Explanation For The Management of Remote Workers in Virtual OrganizationsLuan CardosoNo ratings yet

- Development Topic GuideDocument16 pagesDevelopment Topic Guideanushka09indxbNo ratings yet

- NCM 102 Prelim NotesDocument12 pagesNCM 102 Prelim NotesCABAÑAS, Azenyth Ken A.No ratings yet

- Gestalt TheoryDocument32 pagesGestalt TheoryStevenNo ratings yet

The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students' Active Procrastination

The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students' Active Procrastination

Uploaded by

fatma zülal kullukçuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students' Active Procrastination

The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students' Active Procrastination

Uploaded by

fatma zülal kullukçuCopyright:

Available Formats

The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students’ Active

ProcrastinationLauren C. Hensley

hen students procrastinate, they divert time fromacademicstoward other activities, returning

W

toacademicsat a later time. The prevailingconsensusamong higher education scholars and

practitionersis that procrastination reflects motivationalstruggles and harms students

academically(Milgram & Tenne, 2000). However, somestudents intentionally procrastinate in

college and appear tobenefitfrom doing so. Activeprocrastination describes the behavior of

students who prefer to work under pressure, choose to postponeassignedwork, complete

requirementsby deadlines, andattainsatisfactorygrades(Chu & Choi, 2005). An active

procrastinator might, forinstance, start writinga paper the night before it is due. She would

engage in this activity not as a last resort but with theanticipationof stayingfocused, meeting

assignmentexpectations, andachievingher desiredgradein aminimalamount of time.

Although “legitimizing the procrastinationprocess”is a possibleimplication(Schraw, Wadkins,

& Olafson, 2007, p. 23), caution is warranted in light of the competingevidenceandpotential

impacton students. To simultaneously weigh the appealand ramifications of active

procrastination, this studyidentifiesreasons forcollege students’commitmentto

procrastination alongsideperceivedlimitations ofthe behavior.

ctive procrastination is a departure from the form of procrastinationdefinedby scholars as

A

passive(i.e., avoidant, maladaptive) in nature.Traditionally,researcherslinkedprocrastination

to difficulty with self-regulationand discomfortwith making decisions (Milgram & Tenne,

2000), as well as low confidence andgrades(Corkin,Yu, & Lindt, 2011). To better understand

why some procrastinators did not experience these correlates oroutcomes, scholars reframed

procrastination as an active, rather than apassive,behavior (Choi & Moran, 2009; Chu & Choi,

2005). Byapproachingprocrastination as an active(i.e., purposeful,adaptive) behavior,

scholars couldhighlightbeneficialoutcomesfor studentswho intentionally delayedacademics.

Survey-based studies of active procrastination haveincluded undergraduates of allacademic

levels and arangeofethnicbackgrounds. The studies,which reportedaggregateresults and did

not test for group-level differences,demonstratedoverallpositiverelations between active

procrastination and desirable characteristics.Researchersdemonstrated connections to high

gradesin a human development course (Corkin et al.,2011), life satisfaction and self-reported

cumulative GPA for students at three Canadian universities (Chu & Choi, 2005), and emotional

stabilityfor Canadian business students (Choi & Moran,2009). Corkin et al. expressed concern,

however, aboutnegativecorrelations with students’motivationfor learning.

Twomajorqualitativestudies shed light on collegestudents’ procrastination. In an interview

b ased study of German undergraduates from 17 disciplines, mostthemeswere “deficit-

Academic Year 2022-2023

1

Hensley, L.C. (2016). The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students’ Active Procrastination.Journal

of College Student Development 57(4), 465-471. doi:10.1353/csd.2016.0045.

o riented” (p. 404), reflecting a lack of motivation,self-regulation, or confidence (Klingsieck,

Grund, Schmid, & Fries, 2013). Theaspectof workingbest under pressureemergedfor a small

group ofparticipantsas one of manythemes. In anotherstudy, “students who viewed

themselves as successful procrastinators”participatedin interviews andfocusgroups (Schraw

et al., 2007, p. 24). Findingsrevealedvariousbenefitsof procrastination, including heightened

creativityand the opportunity to reflect on atopicbefore working on it. One student remark

suggested that active procrastination was not entirelypositive: “You’ve just got to tell yourself

that procrastination is the right thing to do even though you know it isn’t” (Schraw et al., p. 20).

To better understand thisinternalcontradiction,I developed a phenomenology of college

students’ active procrastination. The study extendsprior investigationsby drawing outpositive

andnegativeaspectsthat existed simultaneously inthe lived experience of active

procrastination.

ctive procrastination appears bothcontradictoryand commonplace. The preponderance of

A

evidencecharacterizes cramming as ineffective, yetit is difficult toignorestudents’ descriptions

of working well under pressure (Ferrari, 2001). Although active procrastination is connected

with highgrades, it has not beenidentifiedas adirect cause of highacademicperformance

(Chu & Choi, 2005). Active procrastinators are confident in their ability to learn but do not have

a strong desire to learn (Corkin et al., 2011). Furtherresearchis needed to explore the intricacies

of this behavior andclarifythe extent of itsbenefitsfor students.

ETHOD

M

The inductiveprocessesof phenomenology provideda means foridentifyingthemesthat

definedwhat it meant to actively procrastinate. Phenomenologyis aqualitativemethodology

thatenhancesunderstanding of aspecificphenomenonby developing a description of

shared,coremeaningsderivedfromindividualaccounts(Moustakas, 1994). Iselectedthis

methodologyin order toundertakean in-depth studyof active procrastinationviathe

experiences and reflections of a small group ofparticipantswith firsthand knowledge of the

phenomenon.

articipantsandDataCollection

P

Seven students whose recounted experiences reflected active procrastination became thefocusof

the study,similarto the samplingmethodused bySchraw et al. (2007) and in line with

recommendedrangesfor phenomenologicalresearch.The sample reflected the use ofcriterion

sampling,whereby“allindividualsstudied representpeople who have experienced the

phenomenon” (Creswell, 2013, p. 128).Participantsweretraditionallyaged undergraduates at

a large, 4-year public university in the Midwestern United States during spring 2013. Students

represented six different majors,primarilyin thesciences (e.g., microbiology, neuroscience).

Four students hadminors, which were in the humanities(e.g., dance, English). Four

participantswere men and three were women; all wereWhite.

Academic Year 2022-2023

2

Hensley, L.C. (2016). The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students’ Active Procrastination.Journal

of College Student Development 57(4), 465-471. doi:10.1353/csd.2016.0045.

y writing in studyjo urnals,participantsprovideda personal record of procrastination. Guided

B

by five questions in an introductoryjo urnalentry,students conveyed their typicalperceptionsof

procrastination and described the semester’s demands. Writing six additional entries over one

month, students reflected on thoughts, feelings, andoutcomesassociated withspecificinstances

of procrastination. In a follow-up semi-structuredinterview, each student described recent

procrastination in depth and elaborated upon multiplejo urnalexcerpts.

nalysis

A

Using the phenomenologicaldata analysis approachdeveloped by Moustakas (1994), I first

identified significantstatements thatreflected students’descriptions of active procrastination. I

then namedcore componentscommon acrossparticipantsby translatingspecificaccounts into

sharedconceptsandabstractions. I discussed andrevisedthecoding schemewith a doctoral

candidate until we reachedconsensusthat it reflectedparticipants’ experiences. Next, I

clusteredthemesin an overarchingframework. Toenhancetrustworthiness, Icreateda cross

caseanalysismatrix toensureeachthemeappearedacross all cases.Finally, I developed the

written description of thephenomenon.

INDINGS

F

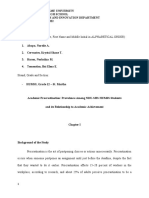

Findingsrevealedthreemajorthemesabout activeprocrastination: Purposeful delayfacilitated

greater efficiency (I’m good at it); was done systematically (I’ve learned I can); and was

reinforcedby appealingacademicand socialoutcomes(It’s worth it). Table 1 provides an

overview ofthemes,codes, andtextual evidence. Theexistence of a concomitantnegative

componentfor eachpotential benefitwas an unexpectedthemethatemergedfrom the

analysis. The drawbacks of active procrastinationdid notfunctionseparately from thebenefits.

Rather, they appeared asinherentcounterpoints tothepositivecomponentsand were part of

the broader experience; active procrastination was not active procrastination without both sides.

I ’m Good at It: The Efficiency of Procrastination

Studentsviewedthemselvesaseffectiveprocrastinators.Whenstudentshadopenblocksoftime,

they“ha[d]moreexcuses”tousesocialmedia,answertexts,playvideogames,orstreamonline

videos.Withtheurgencyofanupcomingdeadline,studentscouldbetterregulatetheirattention.

Students preferred the efficiency of working under pressure, which they described as providing

them with anenhancedability tofocusandignoredistractions.

s anaspectof thisapproach, students experiencedheightened levels ofstressand anxiety as

A

they turned to complete last-minute work.Despitetheirgradesbeing satisfactory, students were

alsoawarethat procrastination could reduce the qualityof learning. Students could “cut to the

chase and give them what they want out of the paper” or “relyon short-term memory” without

developing deep understanding.

Academic Year 2022-2023

3

Hensley, L.C. (2016). The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students’ Active Procrastination.Journal

of College Student Development 57(4), 465-471. doi:10.1353/csd.2016.0045.

I ’ve Learned I Can: The Intentionality of Procrastination

Students learned frompriorschooling that procrastinationwas a viableresponsetoacademic

requirements. Theycreditedtheiracademicabilitieswithenablingthem to “catch up orretain

more information than [their] peers.” Students who procrastinated in high school continued the

behavior in college, where their courses weresomewhatmorechallengingyet did notrequirea

dramaticshiftin study habits. Theypredictedhowmuch effortassignmentsrequiredand

allocatedonly that amount of time.

rocrastination did not always go according to plan. Frustration resulted from under-estimating

P

time, distractions, or obstacles. Looking to the future, students were not optimistic about “still

getting by with procrastinated work” in advanced courses, graduate school, or the workforce.

I t’s Worth It: ThePerceivedValue of Procrastination

For the time being, students continued to procrastinate because working under pressure

repeatedly produced acceptableacademicoutcomes,such as As and Bs on most papers, exams,

andassignmentscompleted close to deadlines. As onestudent reasoned, “What’s the point in

changing when I know I can do this and it works for me?” Still, students often sensed they

“could have done a little bit better” and that passinggradeswere “certainly not the quality of

work [they were] able to produce.” Moreover, they recognized it was risky to expect

procrastination to suffice in all situations.

Academic Year 2022-2023

4

Hensley, L.C. (2016). The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students’ Active Procrastination.Journal

of College Student Development 57(4), 465-471. doi:10.1353/csd.2016.0045.

TABLE 1.

MajorThemes,Codes, and ExemplaryQuotes

I’m Good At It

ResearchinBriefI Work and Learn Effectively Close But Efficiency Comes at a Cost

to Deadlines

I ’m more efficient with less “ If it’s due the next rocrastination

P “I felt very rushed when

time (few distractions, high day, I can sit down causesstress c ompleting theassignments,

focus) andfocusjust on which led to

my paper, and get anoverallmorestressfulexperience

it done really than I needed to have.”

efficiently.”

I complete coursework best “ When I I don’t learn as deeply “If I did not procrastinateIwould

under pressure procrastinate, I as I could s tart preparing for exams earlier

write better. I and have a better grasp of

remember things material.”

better. So as far as

quality of

schoolwork, I

think that I do

better when I

procrastinate.”

I’ve Learned I Can I Know I Can

RespondtoAc ademicRequirementsWith Procrastination But This System May Not Always Work

Innateacademicability “ You can feel like, y abilities differ based on

M “ In biology, that doesn’t

‘I’ll put that off. the course work for me. I have to

I’m smart enough. I read.”

can catch up to

that.’”

Planning to procrastinate “ I have a plan and I My plans don’t always work “It was like, ‘yeah, that’s

believe it will help n ot happening.’”

me in the end.”

I’ve figured out a system “ I’ve done a lot of I know I can’t do this forever “I think in the future it’s

[papers] and I know p robably gonna backfire on

how long they take.” me sometime.”

It’s Worth It

It’s Worth It in Terms ofAcademicOutcomes But I Know I Could Still Do Better

ygradesare not threatened by

M “ Procrastination Myacademicoutcomes “ I did decent; however, I

procrastination usually doesn’t have c ould be better think I could have done a

a little better if I had started

largeimpacton studying earlier.”

mygrade.”

ositiveacademicoutcomesreinforce

P “ When I dofinally I need to be careful not to “There’s trouble when you

mybehavior do [a ssignments] overgeneralize take that justification and

I get apply it to another course

goodgradesand where that

theprojectlooks doesn’t work.”

pretty good. So then

I think that I can

just

procrastinate all the

time.”

It’s Worth It in Terms of SocialOutcomes But What I’m Procrastinating Is on the Back of My Mind

rocrastinatingensuresI have balance

P “ If I’d started I can’t enjoy other activities “When I go to do something

in my life earlier I might not a s much e lse, I’m always thinking

have been about what I’m supposed to

able to hang out be

with my friends.” doing.”

rocrastination makes time for

P “ Some of my best I feel upset with myself “Typically I feel a kind of

meaningful experiences times so far in eird sense of guilt.”

w

college have been

from

procrastination.

They’re the

memories that are

priceless.”

s for desirable socialoutcomes, students chose to procrastinate toensurethey would not miss

A

out on the college experience. They defended the importance of “find[ing] the balance that works

for you,”highlightingextracurricularinvolvementand family visits made possible by the time

carved out by procrastination. Lingering thoughts about incomplete schoolwork wouldtrigger

worry and guilt during students’ social and leisure activities. Managing these thoughts, however,

outweighed theprospectof “being a really perfectstudent and never having any fun.”

ISCUSSION

D

This study portrays theinherenttensionin students’decisions to delay, offering several

refinementsto earlier conceptualizations of activeprocrastination (Choi & Moran, 2009; Chu &

Choi, 2005). Active procrastinators receiveoutcomessatisfying enough to encourageongoing

procrastination but recognize they could learn more deeply or receive slightly highergrades.

These students use pressure to force themselves tofocus, but this pressure is unpleasant and

depends onexternalregulation. Students meet deadlinesin most situations, but their plans to

procrastinate can be unfruitful at times. They intentionally decide to delay, yet with this

intentionality comes the recognition that procrastination might not fit allcontexts.Focus,stress,

fun, and guilt allcontributeto the holistic experienceof active procrastination,revealingthe

complexityof itspreviouslystated connections toaffectand well-being (Choi & Moran, 2009).

eaturesofcontemporarycollege students andenvironmentsreveala broadercontextfor

F

active procrastination. As mobiledevicesand streamingmediainfuse campus, active

procrastinationemergesas a way for students to forcethemselves tofocus. Many young-adult

college students also have the Millennial characteristic of a need for immediate gratification, that

is, toattainnearly instantaneous results (Oblinger,2003). They place high value on relationships

and are accustomed to managing multiple activities (Levine & Dean, 2012). Lengthy papers and

end-of-semester exams offer less appeal than leisure or social experiences with more immediate

rewards. In line with these characteristics, it is not surprising to see college studentsstrategically

procrastinating to fit in schoolwork as one of many activities.

indings of this studyrevealseveral reasons forstudents’commitmentto procrastination.

F

Active procrastinators can often completeassignmentsefficiently,attainacceptablegrades, and

advance social connections. There are, however, drawbacks in terms ofstress, surface-level

learning, and feelings of regret and guilt.Acknowledgingthe delicate balance between

procrastination’s draws and drawbacks,implicationsfor practice relate to both educational

environmentsand support for self-directed change.

Students most likely to engage in active procrastination appear to be those with a strong sense of

a cademicconfidence paired with a history of not puttingforth great time or effort to earn high

grades. Advisors and support personnel who inquire into these students’ backgrounds will likely

hear statements about rarely having to study in high school. To support higher order learning

Academic Year 2022-2023

6

Hensley, L.C. (2016). The Draws and Drawbacks of College Students’ Active Procrastination.Journal

of College Student Development 57(4), 465-471. doi:10.1353/csd.2016.0045.

o utcomes, it may be important to help such studentsrefinethe number of situations in which

they procrastinate. Active procrastinatorsseektominimizethe time and effort spent on

academics, but cognitive growthrequiresexpendingmental energy(Nist & Holschuh, 2005).

The key topromotinglearning may lie in connectingactive procrastinators with opportunities

for cognitivelychallenging, engaging learning experiences.

ctive procrastination often reflects detachment between the learner and the act of learning; it is

A

a way, students reported, of “get[ting] it done and over with.” Toshifttheauthorityfor learning

from anexternalto aninternalperspective,instructorscouldcreate participatoryclassroom

environments(e.g., Learning Parterships Model; BaxterMagolda, 1999) in which students play

amajor roleinconstructingknowledge. Advisors couldhelp active procrastinators

selectcourses and cocurricular experiences that presenthigh levels ofchallengeand

personal importance,factorsassociated with viewingeffort as valuable rather than

wasteful.

roducing greaterawarenessof thebenefitsand limitationsof procrastination may also be key

P

to supporting active procrastinators. The effectiveness of procrastinationinterventionsdepends

in large part on how well they reflect students’ reasons for procrastination (Klingsieck et al.,

2013). It is not effective to simply advise students to stop procrastinating in order to succeed in

college. Active procrastinators will likely disregard such overarching statementsasirrelevant

andinaccurate. Advisors might suggest studyjo urnalsto help students track their behavior and

gatherinsightsinto the thoughts, feelings, behaviors,andoutcomesassociated with

procrastination. Theprocessof change is supportedwhenindividuals’ reasons both for and

against making changes in their lives are brought to the surface, particularly in thecontextof an

advising or counseling relationship (Miller & Rose, 2009).

eflections on procrastination were gathered from a small number ofparticipants, whose depth

R

ofparticipationaligned with phenomenologicalresearch.Findingsrefinedthe

conceptualization of active procrastination and informed practicalimplications. The sample

used had limiteddiversityand findings may not representthe experience of active

procrastination for a broaderrangeof ages, ethnicities,or background characteristics. Future

researchersmay wish to usesimilar datacollectionmethodsto explore active procrastination

among morediversesamples. The extension of thisresearchmayrevealadditionalcontextual

features relevantfor active procrastinators who attenddifferent types ofinstitutionsor are in a

different stage of life than their young-adultclassmates.

You might also like

- Barry 2007 Motivating The RELUCTANT STUDENTDocument6 pagesBarry 2007 Motivating The RELUCTANT STUDENTInês Coelho100% (1)

- Corsi Block Tapping TestDocument20 pagesCorsi Block Tapping TestHarshita JainNo ratings yet

- Essential Readings in Problem-Based Learning: Exploring and Extending the Legacy of Howard S. BarrowsFrom EverandEssential Readings in Problem-Based Learning: Exploring and Extending the Legacy of Howard S. BarrowsNo ratings yet

- G4 Q1 W5 DLLDocument7 pagesG4 Q1 W5 DLLMark Angel MorenoNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Conversations: Challenging Habits of ThoughtFrom EverandInterdisciplinary Conversations: Challenging Habits of ThoughtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Schraw, Wadkins, and Olafson (2007) - A Grounded Theory of Academic Procrastination PDFDocument14 pagesSchraw, Wadkins, and Olafson (2007) - A Grounded Theory of Academic Procrastination PDFMireille KirstenNo ratings yet

- Development of An Academic Procrastinati PDFDocument10 pagesDevelopment of An Academic Procrastinati PDFLienel Mitsuna LacabaNo ratings yet

- Why Students Procrastinate - A Qualitative ApproachDocument17 pagesWhy Students Procrastinate - A Qualitative ApproachjoseanerezNo ratings yet

- Hensley Psychology ProcrastinationDocument8 pagesHensley Psychology ProcrastinationTrisztán AranyNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument12 pagesChapter ITom NicolasNo ratings yet

- Understanding Procrastination A Case of A Study SKDocument19 pagesUnderstanding Procrastination A Case of A Study SKDhatri shuklaNo ratings yet

- Ba Harrison J 2014Document48 pagesBa Harrison J 2014Anissa RizkyNo ratings yet

- K B 02 Scielzo McCloskyScielzoDocument42 pagesK B 02 Scielzo McCloskyScielzojyothi swarupNo ratings yet

- Ej 915928Document20 pagesEj 915928Nanang HardiansyahNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Essay 2Document10 pagesLiterature Review of Essay 2Vasu patelNo ratings yet

- PR2-RRL Bonifacio Group4 CuriosityDocument2 pagesPR2-RRL Bonifacio Group4 CuriosityFoamy Cloth BlueNo ratings yet

- Cavusoglu 2015Document10 pagesCavusoglu 2015shwethambarirameshNo ratings yet

- Attribution As A Predictor of Procrastination in Online Graduate StudentsDocument19 pagesAttribution As A Predictor of Procrastination in Online Graduate StudentsТеодора ДелићNo ratings yet

- Argumentation & Discussion 1Document6 pagesArgumentation & Discussion 1AryaNo ratings yet

- ProkrastinasiDocument12 pagesProkrastinasiYuli LasmiatiNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument38 pagesUntitledNorelie AbapoNo ratings yet

- Academic Interventions For Academic Procrastination: A Review of The LiteratureDocument15 pagesAcademic Interventions For Academic Procrastination: A Review of The LiteratureGio SalupanNo ratings yet

- Avaliação The Measurement of Student Engagement - A Comparative Analysis of Various MethodsDocument20 pagesAvaliação The Measurement of Student Engagement - A Comparative Analysis of Various MethodsTiagoRodriguesNo ratings yet

- Academic Probation, Time Management, and Time Use in A College Success CourseDocument20 pagesAcademic Probation, Time Management, and Time Use in A College Success CourseFabiano DantasNo ratings yet

- Correlates of Academic ProcrastinationDocument10 pagesCorrelates of Academic ProcrastinationLoquias RJNo ratings yet

- Lin 2014Document20 pagesLin 2014Alimatu FatmawatiNo ratings yet

- Studie Ejunju LeeDocument11 pagesStudie Ejunju LeeuincomNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Online Graduate Students' Motivation and Self-Regulation On Academic ProcrastinationDocument17 pagesThe Impact of Online Graduate Students' Motivation and Self-Regulation On Academic ProcrastinationNanang HardiansyahNo ratings yet

- Luke Ranieri 17698506 Assignment 1 Researching Teaching and LearningDocument4 pagesLuke Ranieri 17698506 Assignment 1 Researching Teaching and Learningapi-486580157No ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practices For Children, Youth, and Young Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive ReviewDocument17 pagesEvidence-Based Practices For Children, Youth, and Young Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comprehensive ReviewCristinaNo ratings yet

- 2016-Zoupidis Et Al.-PrimariaDocument20 pages2016-Zoupidis Et Al.-PrimariaEsther MarinNo ratings yet

- 72 HFHBDocument10 pages72 HFHBNatasyaNo ratings yet

- Jaber and Hammer 2016 Learning To Feel Like A ScientistDocument32 pagesJaber and Hammer 2016 Learning To Feel Like A ScientistrodrigohernandezNo ratings yet

- Tan E-Lynn Sample Ethics ProposalDocument17 pagesTan E-Lynn Sample Ethics ProposalThiban Raaj100% (1)

- Running Head: PRE-PROPOSAL DRAFT 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: PRE-PROPOSAL DRAFT 1Brenda Lee MoralesNo ratings yet

- Lee 2005 Pro CR StinationDocument11 pagesLee 2005 Pro CR StinationalgiNo ratings yet

- Towards A Better Understanding of The ST PDFDocument7 pagesTowards A Better Understanding of The ST PDFtesfayergsNo ratings yet

- Exploring Relationships Between Procrastination, Perfectionism, Self-Forgiveness and Academic Grade: A Path Analysis.Document40 pagesExploring Relationships Between Procrastination, Perfectionism, Self-Forgiveness and Academic Grade: A Path Analysis.Beth RapsonNo ratings yet

- Expectancy Value InterventionsDocument6 pagesExpectancy Value Interventionsapi-350693115No ratings yet

- Explaining Newton's Laws of Motion: Using Student Reasoning Through Representations To Develop Conceptual UnderstandingDocument26 pagesExplaining Newton's Laws of Motion: Using Student Reasoning Through Representations To Develop Conceptual UnderstandingYee Jiea PangNo ratings yet

- Genderand Age Differencesin Procrastination CangialosiDocument17 pagesGenderand Age Differencesin Procrastination CangialosielegadoNo ratings yet

- Past Science CourseworkDocument5 pagesPast Science Courseworkjxaeizhfg100% (2)

- Chapter 5 ResearchDocument4 pagesChapter 5 ResearchMark Virgil P Tubalhin100% (1)

- Academic Satisfaction and Its Relationship To Internal Locus of Control Among Students of Najran UniversityDocument5 pagesAcademic Satisfaction and Its Relationship To Internal Locus of Control Among Students of Najran UniversityMar Jory del Carmen BaldoveNo ratings yet

- Academic Satisfaction and Its Relationship To Internal Locus of Control Among Students of Najran UniversityDocument5 pagesAcademic Satisfaction and Its Relationship To Internal Locus of Control Among Students of Najran UniversitySteeven ParubrubNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Open Inquiry Performances of HighDocument16 pagesDynamic Open Inquiry Performances of HighNadea NovasarasetaNo ratings yet

- Experiences of College Students With Psychological Disabilities: The Impact of Perceptions of Faculty Characteristics On Academic AchievementDocument11 pagesExperiences of College Students With Psychological Disabilities: The Impact of Perceptions of Faculty Characteristics On Academic AchievementCoordinacionPsicologiaVizcayaGuaymasNo ratings yet

- On The Psyhology of The Subject PoolDocument24 pagesOn The Psyhology of The Subject PoolCaryl Mae BocadoNo ratings yet

- PR 2 - Lindog MARCH 2024 (Body)Document42 pagesPR 2 - Lindog MARCH 2024 (Body)villanuevadimple91No ratings yet

- Academic Procrastination, Self Efficacy and Anxiety of StudentsDocument7 pagesAcademic Procrastination, Self Efficacy and Anxiety of Studentscharvi didwania100% (3)

- Assignment 2Document12 pagesAssignment 2api-485956198No ratings yet

- Mind The Gap! Students' Use of Exemplars and Detailed Rubrics As Formative AssessmentDocument21 pagesMind The Gap! Students' Use of Exemplars and Detailed Rubrics As Formative AssessmentPhu NguyenNo ratings yet

- Development and Validation of A 2x2 Mode PDFDocument39 pagesDevelopment and Validation of A 2x2 Mode PDFMariano DhinzkieeNo ratings yet

- Academic Procrastination and The Performance of Graduate-Level Cooperative Groups in Research Methods CoursesDocument20 pagesAcademic Procrastination and The Performance of Graduate-Level Cooperative Groups in Research Methods CoursesMiko BristolNo ratings yet

- Final ResearchDocument6 pagesFinal Researchelechar morenoNo ratings yet

- Report2 Wan RongDocument11 pagesReport2 Wan RongnfwahidahNo ratings yet

- Article1424941613 - Taura Et AlDocument7 pagesArticle1424941613 - Taura Et AlI Ketut SuenaNo ratings yet

- Procrastination and Academic PerformancesDocument45 pagesProcrastination and Academic Performancesadrianelindog02No ratings yet

- Student Voices Following Fieldwork FailureDocument14 pagesStudent Voices Following Fieldwork FailureSergioNo ratings yet

- Academic Procrastination and Factors ContributingDocument12 pagesAcademic Procrastination and Factors ContributingAldi kristiantoNo ratings yet

- FINALDocument117 pagesFINALAvrielle Haven JuarezNo ratings yet

- JR I ArticleDocument19 pagesJR I ArticleaneelaNo ratings yet

- Faculty Development and Student Learning: Assessing the ConnectionsFrom EverandFaculty Development and Student Learning: Assessing the ConnectionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Reading Assessment Behavioral Checklist - Form 2Document1 pageReading Assessment Behavioral Checklist - Form 2farnaida kawitNo ratings yet

- The Cognitive Model: Beck and EllisDocument13 pagesThe Cognitive Model: Beck and Ellismohammad alaniziNo ratings yet

- Annurev Neuro 101222 110632Document20 pagesAnnurev Neuro 101222 110632Kama AtretkhanyNo ratings yet

- Task 2 - Group Oral PresentationDocument6 pagesTask 2 - Group Oral PresentationBI2-0620 Siti Nurshahirah Binti Mohamad AzmanNo ratings yet

- AI AutoDocument16 pagesAI Autoمحمد أحمدو اليعقوبيNo ratings yet

- Lecture Bloom TaxonomyDocument5 pagesLecture Bloom TaxonomyAnne BautistaNo ratings yet

- Principles 6-8Document28 pagesPrinciples 6-8Paula García GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Brochure CMU-DELE 03-05-2023 V12Document12 pagesBrochure CMU-DELE 03-05-2023 V12Lucas Fernandes LuzNo ratings yet

- SED LING 2 Activity 2Document3 pagesSED LING 2 Activity 2Sylvia DanisNo ratings yet

- Pagina 1 y 2. 1 Copia. Pagina 3. 25 CopiasDocument3 pagesPagina 1 y 2. 1 Copia. Pagina 3. 25 Copiasanalisalazar390No ratings yet

- Etiology and Recovery of Neuromuscular Fatigue Following Sim..Document1 pageEtiology and Recovery of Neuromuscular Fatigue Following Sim..Martín Seijas GonzálezNo ratings yet

- SS3 Culmination: The Best of MEDocument34 pagesSS3 Culmination: The Best of MEMartine Andrei Macado SabandoNo ratings yet

- Tacit & Explicit KnowlwdgeDocument12 pagesTacit & Explicit KnowlwdgeJeswin P UNo ratings yet

- AsynchornousDocument1 pageAsynchornousjohn paul PatronNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism CognitivismDocument2 pagesBehaviorism CognitivismIan PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Adjuster Training Modul FIDocument6 pagesAdjuster Training Modul FIFaisal AzharNo ratings yet

- Semantics - NG NghĩaDocument2 pagesSemantics - NG NghĩaK60 Trần Đoan TrangNo ratings yet

- 영교론 Glossary 모음Document12 pages영교론 Glossary 모음Seunghye ParkNo ratings yet

- Simple Reaction Time - Lab ReportDocument7 pagesSimple Reaction Time - Lab ReportRUFINO, Aira JheanneNo ratings yet

- Physical Self and DevelopmentDocument2 pagesPhysical Self and Developmentvictoria vistanNo ratings yet

- Understanding EmotionsDocument9 pagesUnderstanding EmotionsBuat DaftardaftarNo ratings yet

- Basics of Generative AIDocument6 pagesBasics of Generative AIneerajsingh2452No ratings yet

- الفضاءات الباقية في الذاكرةDocument24 pagesالفضاءات الباقية في الذاكرةhl7694016No ratings yet

- A Self-Efficacy Theory Explanation For The Management of Remote Workers in Virtual OrganizationsDocument20 pagesA Self-Efficacy Theory Explanation For The Management of Remote Workers in Virtual OrganizationsLuan CardosoNo ratings yet

- Development Topic GuideDocument16 pagesDevelopment Topic Guideanushka09indxbNo ratings yet

- NCM 102 Prelim NotesDocument12 pagesNCM 102 Prelim NotesCABAÑAS, Azenyth Ken A.No ratings yet

- Gestalt TheoryDocument32 pagesGestalt TheoryStevenNo ratings yet