Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reflecting On Your Own Talk: The Discursive Action Method at Work

Reflecting On Your Own Talk: The Discursive Action Method at Work

Uploaded by

Vishrut PatelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reflecting On Your Own Talk: The Discursive Action Method at Work

Reflecting On Your Own Talk: The Discursive Action Method at Work

Uploaded by

Vishrut PatelCopyright:

Available Formats

10

Reflecting on Your Own Talk: The

Discursive Action Method at Work

Joyce Lamerichs and Hedwig te Molder

This chapter describes how we developed a Conversation Analysis-based

intervention approach, which we call the Discursive Action Method. The

method aims to make people critically aware of how they talk and, on that

basis, to help them shape their own practices. The method has its roots in

an early statement of what Edwards and Potter termed their ‘Discursive

Action Model’ (Edwards and Potter, 1993) and is based on insights from

Conversation Analysis and Discursive Psychology1 more generally (Edwards,

1997; Edwards and Potter, 1992; Hepburn and Wiggins, 2007; Hutchby and

Wooffitt, 1998; Potter, 1996; Potter and Te Molder, 2005).

We developed the Discursive Action Method (DAM, for brevity’s sake) as

a systematic method in response to the needs that emerged from trying to

educate young people about health and wellbeing. The framework was a

four-year participatory health education project called LIFE21,2 and our brief

was to encourage adolescents to work out school-based health interventions

geared towards their peers. What we developed over that period is, we think,

a robust and portable set of techniques, based fundamentally on a CA reading

of talk, that can be used in a variety of intervention programmes.

Before explaining the steps of the DAM in greater detail, it is important

to point out that the method can fulfil different functions. The method can

work with any intervention where there is engagement between trainers or

facilitators and the people whose practices are to be changed (as is reported

in other chapters in this volume; see for example, Kitzinger with call tak-

ers on a help line in Chapter 6, Stokoe’s work with mediators in Chapter 7,

or Finlay, Walton and Antaki’s with care staff in Chapter 9). Depending on

the key questions that are posed during the workshop by trained workshop

leaders, different goals can be achieved. As such, the method can stimulate

participants to improve their listening skills, raise their awareness of how

184

C. Antaki (ed.), Applied Conversation Analysis

© Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited 2011

Reflecting on Your Own Talk 185

they talk and act, or encourage participants to develop their own activities.

In the context of the current project, the method aimed to accomplish the

second and the third goal in particular. While applied here in a health con-

text, we think the method consists of a set of generic steps that makes it a

useful approach to be employed in other settings, where it can be flexibly

adapted to the needs of the target group. We will discuss these matters of

applicability more fully in the discussion. In the remainder of this chapter

we set out to explain the method’s steps and how they were applied, how the

method was instrumental in raising adolescent’s critical awareness of how

they talk and act with their peers, as well as how it formed a basis for setting

up school-based health activities.

Background to the project: a conversational turn in

developing health activities

The participatory health education project that brought us into contact with

young people was conducted in cooperation with the municipal health serv-

ices in Eindhoven, a middle-sized city in the south of the Netherlands. The

municipal health services are well-connected to the target group on many

levels (see, for an overview, Lamerichs et al., 2006). LIFE21 was ultimately

conducted at three secondary schools for higher education in Eindhoven.

The project’s aim was to invite adolescents (14 to 17 years of age) to think

about the ways in which they talk about health in their everyday conversa-

tions, and to use those reflections as the basis for them to develop health

interventions aimed at their peers.

There have been several attempts to apply insights from interaction analysis

to the area of health communication. Initiatives that aim to improve commu-

nication in this area share a concern for: (1) working with naturally occurring

talk rather than data created for the purpose of research (e.g., setting up focus

groups with target group members) and (2) using taped material (often referred

to as ‘trigger tapes’, see Jones, 2007: 2299) or transcripts as the basis to engage in

a discussion about particular aspects of the unfolding talk (Koole and Padmos,

1999; Roberts, Davies and Jupp, 1992). The development of the DAM can be

placed within this tradition. One of the method’s most important assets is its

strong basis in the interactional details of the conversational materials. But

compared to other projects, our method is also innovative in two other ways.

First, the input for the method – conversational data from the target group – is

collected by members of the target group themselves; and second, after a pre-

liminary analysis of the data by the researchers involved in the project, mem-

bers of the target group are turned into analysts of their own data.

You might also like

- Ethical Comportment - Mne 625Document18 pagesEthical Comportment - Mne 625api-312894659No ratings yet

- Group-Based, Person-Centered Diabetes Self-Management Education: Healthcare Professionals ' Implementation of New ApproachesDocument11 pagesGroup-Based, Person-Centered Diabetes Self-Management Education: Healthcare Professionals ' Implementation of New ApproachesChristian MolimaNo ratings yet

- Participatory Action Research:: An Educational Tool For Citizen-Users of Community Mental Health ServicesDocument35 pagesParticipatory Action Research:: An Educational Tool For Citizen-Users of Community Mental Health ServicesMauricio TejadaNo ratings yet

- 510 Final Design ProposalDocument12 pages510 Final Design Proposaljstieda6331No ratings yet

- Research, Development, Diffusion and Social Interaction ModelsDocument13 pagesResearch, Development, Diffusion and Social Interaction ModelsSimon FillemonNo ratings yet

- Copro Guidance Feb19Document20 pagesCopro Guidance Feb19Sebastian MaierNo ratings yet

- 01 Koshy Et Al CH 01Document24 pages01 Koshy Et Al CH 01sandyshores492No ratings yet

- Curriculum Development PaperDocument7 pagesCurriculum Development PaperAnggaflash RevolverNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Teaching Project Paper 1Document10 pagesRunning Head: Teaching Project Paper 1api-539369902No ratings yet

- Daniel Stevens Edae 624 Ttop FinalDocument12 pagesDaniel Stevens Edae 624 Ttop Finalapi-361448302No ratings yet

- Step One: A Clear VisionDocument4 pagesStep One: A Clear Visionnorma thamrinNo ratings yet

- Lec 02Document6 pagesLec 02Renei Rose Bernabe MangohigNo ratings yet

- Advocacy ManualDocument212 pagesAdvocacy Manualsylvain_rocheleauNo ratings yet

- It Coursework Community Spirit EvaluationDocument7 pagesIt Coursework Community Spirit Evaluationpqltufajd100% (2)

- Focus Groups: A Practical Tool For Practitioner Research: IB Journal of Teaching PracticeDocument6 pagesFocus Groups: A Practical Tool For Practitioner Research: IB Journal of Teaching PracticeIrma SeverinoNo ratings yet

- Reflection On Ipe Groupwork 1Document2 pagesReflection On Ipe Groupwork 1api-636812749No ratings yet

- A Delphi Approach To Boost An Open Innovation PolicyDocument18 pagesA Delphi Approach To Boost An Open Innovation PolicyArvind BhisikarNo ratings yet

- Olajumoke Akintomide Critical PaperDocument9 pagesOlajumoke Akintomide Critical PaperjumokeNo ratings yet

- Methods Used in ExtensionDocument10 pagesMethods Used in ExtensionDebapriya BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Concern Based ModelDocument16 pagesConcern Based ModelZYuanDingNo ratings yet

- Focus Group Methodology1Document18 pagesFocus Group Methodology1Itzel HernandezNo ratings yet

- Positionpaperonproblem Basedlearningnetwork PDFDocument17 pagesPositionpaperonproblem Basedlearningnetwork PDFcita ignacioNo ratings yet

- 4 THDocument76 pages4 THGete ShitayeNo ratings yet

- The Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) : A Model For Change in IndividualsDocument16 pagesThe Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM) : A Model For Change in Individualsmfruz80No ratings yet

- Theory of ChangeDocument16 pagesTheory of ChangeBach AchacosoNo ratings yet

- A Conceptual Framework For Infusing Behavior Change Theories Into Program DesignDocument10 pagesA Conceptual Framework For Infusing Behavior Change Theories Into Program DesignrahimisaadNo ratings yet

- Exploring Faculty Preparedness and Capability For Interprofessional LearningDocument1 pageExploring Faculty Preparedness and Capability For Interprofessional LearningSadashiv RahaneNo ratings yet

- Essay Introduction ExampleDocument4 pagesEssay Introduction Examplekbmbwubaf100% (3)

- Focus Group 1346Document10 pagesFocus Group 1346almaasNo ratings yet

- Health Research For Policy, Action and Practice: Resource Modules Version 2, 2004Document34 pagesHealth Research For Policy, Action and Practice: Resource Modules Version 2, 2004pa3ckblancoNo ratings yet

- NLP Communication Seminars in Nursing - HenwoodDocument5 pagesNLP Communication Seminars in Nursing - HenwoodTushank BangalkarNo ratings yet

- Action-Oriented ApproachDocument8 pagesAction-Oriented Approachsteban AlemanNo ratings yet

- Anubhav - Assignment FLCDocument14 pagesAnubhav - Assignment FLCTREESANo ratings yet

- Behaviour Change Communication in Health PromotionDocument11 pagesBehaviour Change Communication in Health Promotionsandranahdar611No ratings yet

- R.P.P. Postítulo Inglés-Gerardo González QuevedoDocument25 pagesR.P.P. Postítulo Inglés-Gerardo González QuevedoGerardo E. GonzálezNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument4 pagesDownloadLuis FelipeNo ratings yet

- Signature AssignmentDocument5 pagesSignature AssignmentDavid MizrahiNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument4 pagesResearch MethodologySubrat RathNo ratings yet

- English 10 - 2nd Quarter - Module First WeekDocument8 pagesEnglish 10 - 2nd Quarter - Module First WeekMeg KylaNo ratings yet

- Step Ly Step: The Human Relations SurveyDocument6 pagesStep Ly Step: The Human Relations SurveyAlvaro Ruiz UnicvNo ratings yet

- Center For Collaborative Action ResearchDocument8 pagesCenter For Collaborative Action ResearchIrwansyah ritongaNo ratings yet

- Mass Media EffectivenessDocument7 pagesMass Media EffectivenessProfessor Jeff French100% (1)

- Defining Peer Education - 1999 - Journal of AdolescenceDocument12 pagesDefining Peer Education - 1999 - Journal of AdolescenceIvo TheusNo ratings yet

- 01 Koshy Et Al CH 01 PDFDocument24 pages01 Koshy Et Al CH 01 PDFiamgodrajeshNo ratings yet

- Step 1 - Developing A Conceptual Model Instructions and WorksheetDocument8 pagesStep 1 - Developing A Conceptual Model Instructions and WorksheetTolulope AbiodunNo ratings yet

- Using CTL-based Online Discussion Strategies To Facilitate Higher Level LearningDocument7 pagesUsing CTL-based Online Discussion Strategies To Facilitate Higher Level LearningErsa Izmi SafitriNo ratings yet

- Diversity Inclusion Curriculum ResourceDocument64 pagesDiversity Inclusion Curriculum Resourceapi-283591116100% (1)

- MOOC Welcome Video enDocument6 pagesMOOC Welcome Video enТ' АмарбаясгаланNo ratings yet

- KKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKK M N N N N N NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNDocument12 pagesKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKKK M N N N N N NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNEuston ChinharaNo ratings yet

- Expert Concept Mapping Study On Mobile Learning: PurposeDocument15 pagesExpert Concept Mapping Study On Mobile Learning: PurposeJuan BendeckNo ratings yet

- Health EducationDocument18 pagesHealth Educationsharma0120No ratings yet

- Action Research: A Strategy in Community EducationDocument8 pagesAction Research: A Strategy in Community EducationBee BeeNo ratings yet

- 01 Introduction To Research MethodsDocument6 pages01 Introduction To Research Methodsodhiambovictor2424No ratings yet

- Community Based Social MarketingDocument7 pagesCommunity Based Social MarketingJosé A. AristizabalNo ratings yet

- Cando G10Q2 SLHT1Document9 pagesCando G10Q2 SLHT1Jaymarie PepitoNo ratings yet

- Focus Groups - Anita GibbsDocument7 pagesFocus Groups - Anita Gibbsnguyenngocquangyl123No ratings yet

- Who Are The Beneficiaries of Our Educational Research?Document9 pagesWho Are The Beneficiaries of Our Educational Research?chitanda eruNo ratings yet

- W11 - W13 Lesson 4 Communication Aids and Strategies Using Tools of Technology - ModuleDocument8 pagesW11 - W13 Lesson 4 Communication Aids and Strategies Using Tools of Technology - ModuleShadrach AlmineNo ratings yet

- A Guide for Culturally Responsive Teaching in Adult Prison Educational ProgramsFrom EverandA Guide for Culturally Responsive Teaching in Adult Prison Educational ProgramsNo ratings yet

- Player InstructionsDocument1 pagePlayer InstructionsVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Ancillary Sheets v1.3Document6 pagesAncillary Sheets v1.3Vishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Vault Sheet v1.3Document1 pageVault Sheet v1.3Vishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Reflective Questions, Prompts and GuidelinesDocument2 pagesReflective Questions, Prompts and GuidelinesVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Cocoon Stat BlocksDocument4 pagesCocoon Stat BlocksVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Bone Dry BushesDocument5 pagesBone Dry BushesVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- FromTheMud A4 Dark EN v0Document1 pageFromTheMud A4 Dark EN v0Vishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- The Museum - Facilitator's Master Sheet-1Document1 pageThe Museum - Facilitator's Master Sheet-1Vishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Dungeon Room GeneratorDocument4 pagesDungeon Room GeneratorVishrut Patel0% (1)

- Layers of Unreality - Character CreationDocument6 pagesLayers of Unreality - Character CreationVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- A Guide For Academics - Open Book Exams: What Is It?Document2 pagesA Guide For Academics - Open Book Exams: What Is It?Vishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Welcome To The Ninth WorldDocument2 pagesWelcome To The Ninth WorldVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- k1nn8EThT1eZ5 BE4f9XlA Patel Event Plus Org ChartDocument1 pagek1nn8EThT1eZ5 BE4f9XlA Patel Event Plus Org ChartVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1: MTH 334: IISER PuneDocument1 pageAssignment 1: MTH 334: IISER PuneVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- 2400 Orbital Decay v1.3 SpreadsDocument2 pages2400 Orbital Decay v1.3 SpreadsVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3: MTH 334: IISER PuneDocument1 pageAssignment 3: MTH 334: IISER PuneVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- Notes 15: Wright-Fisher ModelDocument4 pagesNotes 15: Wright-Fisher ModelVishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- PH360: Biological Physics (2018)Document3 pagesPH360: Biological Physics (2018)Vishrut PatelNo ratings yet

- V.,M Oo - ,: Six Dimensions Fluency RubricDocument1 pageV.,M Oo - ,: Six Dimensions Fluency Rubricapi-548626684No ratings yet

- Rubrics For Reading Evaluation Grade 6Document15 pagesRubrics For Reading Evaluation Grade 6Jimboy GocelaNo ratings yet

- 7 Types of CurriculumDocument2 pages7 Types of CurriculumYstal TylerNo ratings yet

- Lojban For Beginners - Robin TurnerDocument222 pagesLojban For Beginners - Robin Turnermaeslor100% (1)

- English 7 Activity Sheet: Quarter 3 - MELC 2Document14 pagesEnglish 7 Activity Sheet: Quarter 3 - MELC 2Ludovina Calcaña100% (2)

- English 1 GR Lesson: EN2OL-If-j-1.3 EN2LC - Ia-J-1.1 EN2PA-Ia-c - 1.1 EN2BPK-Ia-3 EN2G - Ia-E-7.4 EN2SS-Ia-e - 1.2Document7 pagesEnglish 1 GR Lesson: EN2OL-If-j-1.3 EN2LC - Ia-J-1.1 EN2PA-Ia-c - 1.1 EN2BPK-Ia-3 EN2G - Ia-E-7.4 EN2SS-Ia-e - 1.2Jingeren Tin PedrosoNo ratings yet

- English Plus 1 Practice Kit Grammar Present Simple PositiveDocument2 pagesEnglish Plus 1 Practice Kit Grammar Present Simple PositiveMarcela acostaNo ratings yet

- Sentence Starters Transition Word Mini-LessonDocument5 pagesSentence Starters Transition Word Mini-Lessonapi-243149546No ratings yet

- Grammar Review For New Teachers - Revised VersionDocument57 pagesGrammar Review For New Teachers - Revised VersionClaudio Reyes DuránNo ratings yet

- IELTS Academic High Score - ExtractDocument30 pagesIELTS Academic High Score - ExtractHuynh Van NguyenNo ratings yet

- African American Vernacular LanguageDocument15 pagesAfrican American Vernacular LanguageSimao Bougama100% (2)

- 34 The Zim-Zam ManDocument6 pages34 The Zim-Zam ManS ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Syllabus 07 08 It III-i Advanced English Communication Skills LabDocument3 pagesSyllabus 07 08 It III-i Advanced English Communication Skills LabChaitanya Kumar ReddyNo ratings yet

- Poor Listening Could Lead To Conflicts and Relationship BreakdownDocument4 pagesPoor Listening Could Lead To Conflicts and Relationship BreakdownSamad Raza KhanNo ratings yet

- Are Native English Speakers Really Better TeachersDocument3 pagesAre Native English Speakers Really Better TeachersDimas LuzNo ratings yet

- Ilearn TOEFL Compile PresentationDocument107 pagesIlearn TOEFL Compile PresentationpietysantaNo ratings yet

- Machine Translation ProjectDocument9 pagesMachine Translation ProjectOffice Hydro-CarpatiNo ratings yet

- Arabic Curriculum 7-8Document4 pagesArabic Curriculum 7-8ismaeelNo ratings yet

- Grammar AnswersDocument1 pageGrammar AnswersF DNo ratings yet

- English - Q3 - Week 2Document4 pagesEnglish - Q3 - Week 2Jessel CleofeNo ratings yet

- Great Writing 5e Foundations Unit 2 Exam View TestDocument7 pagesGreat Writing 5e Foundations Unit 2 Exam View TestGraceNo ratings yet

- Adverbs of Manner ExerciesDocument2 pagesAdverbs of Manner ExerciesrobiNo ratings yet

- Advanced Skill Acquisition Programme (ASAP) Government of KeralaDocument7 pagesAdvanced Skill Acquisition Programme (ASAP) Government of KeralaalwinalexanderNo ratings yet

- Q01 Al Baqarah Aayah 125Document4 pagesQ01 Al Baqarah Aayah 125rakinNo ratings yet

- Listening - Cot4thDocument6 pagesListening - Cot4thmichel.atilanoNo ratings yet

- Comparative ChartDocument3 pagesComparative ChartMatías Vladímir CastillejosNo ratings yet

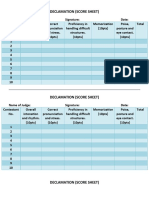

- Declamation and Speech Choir Score SheetDocument3 pagesDeclamation and Speech Choir Score SheetGlad RoblesNo ratings yet

- Hortatory TextDocument8 pagesHortatory TextAthiyya NRNo ratings yet

- AUDIO RECORDING RubricDocument1 pageAUDIO RECORDING RubricEnrique Sandoval HernándezNo ratings yet

- Who Wants To Be A Millionaire ReadingDocument27 pagesWho Wants To Be A Millionaire ReadingSara Cicero RodriguezNo ratings yet