Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 viewsRm3 Enterep212 Entrep Mind Pre Final Period

Rm3 Enterep212 Entrep Mind Pre Final Period

Uploaded by

chenyuishaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Example of Knowledge Management Exam QuestionsDocument23 pagesExample of Knowledge Management Exam QuestionsZhongyi Li80% (5)

- What Happened Before The Organization? A Model of Organization FormationDocument10 pagesWhat Happened Before The Organization? A Model of Organization Formationaftab alamNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5: Breeding Gazelles Competencies: 5.1. A Born or Made Perspective of EntrepreneursDocument25 pagesChapter 5: Breeding Gazelles Competencies: 5.1. A Born or Made Perspective of Entrepreneursmilton04No ratings yet

- Ent Opp SearchDocument25 pagesEnt Opp SearchTanmay SharmaNo ratings yet

- Kumari-2018-SSRN Electronic JournalDocument9 pagesKumari-2018-SSRN Electronic JournalAudree ChaseNo ratings yet

- OpportunitiesDocument31 pagesOpportunitiesPrabha KaranNo ratings yet

- Defining Entrepreneurship - Competing PerspectivesDocument18 pagesDefining Entrepreneurship - Competing Perspectiveseddygon100% (2)

- Knowledge Entrepreneurship: Knowledge Entrepreneurship Describes The Ability To Recognize or Create An Opportunity andDocument6 pagesKnowledge Entrepreneurship: Knowledge Entrepreneurship Describes The Ability To Recognize or Create An Opportunity andhmehtaNo ratings yet

- Employee Motivation and Performance: Obiekwe NdukaDocument32 pagesEmployee Motivation and Performance: Obiekwe NdukaRitika kumariNo ratings yet

- Careers of Perspective: As Repositories Knowledge: A New On Boundaryless CareersDocument20 pagesCareers of Perspective: As Repositories Knowledge: A New On Boundaryless CareersAyyutyas IstiiqomahNo ratings yet

- A Stupidity-Based Theory of OrganizationsDocument27 pagesA Stupidity-Based Theory of OrganizationsJohn Thornton Jr.No ratings yet

- A Situated Metacognitive Model of The Entrepreneurial MindsetDocument13 pagesA Situated Metacognitive Model of The Entrepreneurial MindsetDih LimaNo ratings yet

- Clustering Competence in EIDocument36 pagesClustering Competence in EIHemanth GoparajNo ratings yet

- Career Development TheoryDocument7 pagesCareer Development TheoryNorashady100% (1)

- 2000 Lee Knowledge Value Chain 783 Knowledge ValuDocument11 pages2000 Lee Knowledge Value Chain 783 Knowledge ValuLuzMary Mendoza RedondoNo ratings yet

- Krueger - 2003 - The Cognitive Psychology of EntrepreneurshipDocument36 pagesKrueger - 2003 - The Cognitive Psychology of EntrepreneurshipAnonymous nQB4ZCNo ratings yet

- NORC at The University of Chicago, Society of Labor Economists, The University of Chicago Press Journal of Labor EconomicsDocument33 pagesNORC at The University of Chicago, Society of Labor Economists, The University of Chicago Press Journal of Labor EconomicsrezasattariNo ratings yet

- EntrepreneuriatDocument12 pagesEntrepreneuriatencglandNo ratings yet

- Theories and Assumptions of Entrepreneurship - 0Document16 pagesTheories and Assumptions of Entrepreneurship - 0Clarissa Puguon-maslang PallayNo ratings yet

- Small Business, Innovation, and EntrepreneurshipDocument6 pagesSmall Business, Innovation, and EntrepreneurshipastiNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Role of The Cognitive VariablesDocument25 pagesEntrepreneurial Intentions: The Role of The Cognitive VariablesZeeshan AhmadNo ratings yet

- Organisational DesignDocument37 pagesOrganisational Designpayal sachdevNo ratings yet

- Functionnal StupidityDocument27 pagesFunctionnal StupidityBlaise DupontNo ratings yet

- World's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisherDocument24 pagesWorld's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisheranissaNo ratings yet

- 2000 Lee Knowledge - Value - Chain - 783 - Knowledge - ValuDocument11 pages2000 Lee Knowledge - Value - Chain - 783 - Knowledge - ValuLuzMary Mendoza RedondoNo ratings yet

- A Prescriptive Analysis of Search and Discovery : James O. FietDocument20 pagesA Prescriptive Analysis of Search and Discovery : James O. FietCelina LimNo ratings yet

- Written Assignment Unit 3Document5 pagesWritten Assignment Unit 3Patrice ZombreNo ratings yet

- Theories of Entrepreneurship (14.8.23)Document25 pagesTheories of Entrepreneurship (14.8.23)Himanshu SahdevNo ratings yet

- MOG 2 - Topic 12 - MotivationDocument13 pagesMOG 2 - Topic 12 - MotivationAtif DeewanNo ratings yet

- Transitioning From Hierarchical Bureaucracies Into Adaptive Self-Organizing: The Necessity of Intrinsic Motivation and Self-DeterminationDocument29 pagesTransitioning From Hierarchical Bureaucracies Into Adaptive Self-Organizing: The Necessity of Intrinsic Motivation and Self-DeterminationAntti SnellmanNo ratings yet

- 14: Emotional - Intelligence - As - A - Tool - For - SucDocument27 pages14: Emotional - Intelligence - As - A - Tool - For - SucCarlis Gazzingan100% (1)

- Strategic Resource Management Is Explored Further by Cassia andDocument5 pagesStrategic Resource Management Is Explored Further by Cassia andKimberly JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Work Based ProposalDocument17 pagesWork Based ProposalSteve Mclean100% (1)

- The Knowledge Spillover Theory of EntrepreneurshipDocument37 pagesThe Knowledge Spillover Theory of EntrepreneurshipBipllab RoyNo ratings yet

- Organizational Expatriates' Career Success Aspirations and The Influence of Nationality, Age, and Gender: An Exploratory StudyDocument16 pagesOrganizational Expatriates' Career Success Aspirations and The Influence of Nationality, Age, and Gender: An Exploratory StudyjulianaLatuihamalloNo ratings yet

- Intellectual CapitalDocument12 pagesIntellectual Capitaltramo1234100% (4)

- ET&PDocument15 pagesET&PrejeeeshNo ratings yet

- Prior Knowledge and The Discovery of Ent PDFDocument22 pagesPrior Knowledge and The Discovery of Ent PDFThu LeNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument44 pagesResearch PaperElijah PerolNo ratings yet

- Holsapple y Joshi (2002) Knowledge ManagementDocument19 pagesHolsapple y Joshi (2002) Knowledge ManagementMercedes Baño HifóngNo ratings yet

- Tacit Knowledge and Knowledge ConversionDocument19 pagesTacit Knowledge and Knowledge ConversionFrancesco CassinaNo ratings yet

- A Knowledge-Based Theory of The Firm To Guide Strategy FormulationDocument18 pagesA Knowledge-Based Theory of The Firm To Guide Strategy FormulationDaniloOronozNo ratings yet

- Creativity in Research and Development Environments: A Practical ReviewDocument17 pagesCreativity in Research and Development Environments: A Practical ReviewIvy BeeNo ratings yet

- Sharma and Chrisman 1999Document18 pagesSharma and Chrisman 1999Ayouth Siva Analisis StatistikaNo ratings yet

- Academy of ManagementDocument26 pagesAcademy of ManagementEleonora VintelerNo ratings yet

- Kudesia - 2015 - Mindfulness and Creativity in The WorkplaceDocument23 pagesKudesia - 2015 - Mindfulness and Creativity in The WorkplaceTheLeadershipYogaNo ratings yet

- Social Structural Characteristics of PsyDocument23 pagesSocial Structural Characteristics of PsyYanuar Rahmat hidayatNo ratings yet

- Moberg, D. J. (N.D.) - Managerial Wisdom. The Next Phase of Business Ethics: IntegratingDocument5 pagesMoberg, D. J. (N.D.) - Managerial Wisdom. The Next Phase of Business Ethics: Integratingsnas2206No ratings yet

- A Psychological Model of Entrepreneurial BehaviorDocument12 pagesA Psychological Model of Entrepreneurial BehaviorSamant Khajuria0% (1)

- OFAD-115-MOTIVATION-PRFORMANCE-REWARDS Lesson 8Document3 pagesOFAD-115-MOTIVATION-PRFORMANCE-REWARDS Lesson 8RICHELLE CASTAÑEDANo ratings yet

- Herzberg's TheoryDocument15 pagesHerzberg's TheoryBeezy Bee100% (1)

- Language TeachingDocument33 pagesLanguage TeachingMar'atun SholekhahNo ratings yet

- Anh Truong - Research Methodology1Document8 pagesAnh Truong - Research Methodology1Tram AnhNo ratings yet

- WICS: A Model of Educational Leadership: by Robert J. SternbergDocument7 pagesWICS: A Model of Educational Leadership: by Robert J. SternbergSuvrata Dahiya PilaniaNo ratings yet

- L01 Career Theories OverviewDocument19 pagesL01 Career Theories Overviewdannybmc12No ratings yet

- Journal of Business VenturingDocument17 pagesJournal of Business VenturingmehdiNo ratings yet

- Workbook & Summary - Range - Based On The Book By David EpsteinFrom EverandWorkbook & Summary - Range - Based On The Book By David EpsteinNo ratings yet

- The Power of Minds at Work (Review and Analysis of Albrecht's Book)From EverandThe Power of Minds at Work (Review and Analysis of Albrecht's Book)No ratings yet

- Task 1 PDFDocument11 pagesTask 1 PDFRisaaNo ratings yet

- Social Justice Understanding Health Equity VS Health EqualityDocument1 pageSocial Justice Understanding Health Equity VS Health Equalitygio gonzagaNo ratings yet

- Project Discover: An Application of Generative Design For Architectural Space PlanningDocument9 pagesProject Discover: An Application of Generative Design For Architectural Space PlanningMatthew StewartNo ratings yet

- Topic 5 Multicultural Diversity in TourismDocument4 pagesTopic 5 Multicultural Diversity in TourismNikki BalsinoNo ratings yet

- Villones Table of ContentsDocument5 pagesVillones Table of ContentsBevsly VillonesNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Human DevelopmentDocument3 pagesModule 1 Human DevelopmentMish Lim100% (1)

- Local Media255311538547502585Document7 pagesLocal Media255311538547502585Kyla Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Tools For The Elaboration of Global Marketing Strategy (1) Globlal MKT 5Document48 pagesTools For The Elaboration of Global Marketing Strategy (1) Globlal MKT 5Kiara BaldeónNo ratings yet

- Match LettersDocument43 pagesMatch Lettersshahzad khanNo ratings yet

- Detecting Sarcasm in Text - An Obvious Solution To A Trivial ProblemDocument5 pagesDetecting Sarcasm in Text - An Obvious Solution To A Trivial ProblemsiewyukNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 The Voyage Through The Life SpanDocument9 pagesChapter 9 The Voyage Through The Life SpanMaricris Gatdula100% (1)

- Time Table MCS Fall-19Document8 pagesTime Table MCS Fall-19Aiman KhanNo ratings yet

- ICT 3416 Introduction To Knowledge Management COURSE OUTLINEDocument4 pagesICT 3416 Introduction To Knowledge Management COURSE OUTLINEOkemwa JaredNo ratings yet

- Learning Area Grade Level Quarter Date I. Lesson Title Ii. Most Essential Learning Competencies (Melcs) Iii. Content/Core ContentDocument4 pagesLearning Area Grade Level Quarter Date I. Lesson Title Ii. Most Essential Learning Competencies (Melcs) Iii. Content/Core ContentAlvin PaboresNo ratings yet

- Object Detection With Deep Learning: A ReviewDocument21 pagesObject Detection With Deep Learning: A ReviewDhananjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Kuliah Ke 4 Proses Identifikasi Risiko Dengan Berbagai MetodeDocument48 pagesKuliah Ke 4 Proses Identifikasi Risiko Dengan Berbagai MetodeINDAH PURNAMA SARI MARDJUNINo ratings yet

- Final Case Construction For Cep891 Jie XuDocument9 pagesFinal Case Construction For Cep891 Jie Xuapi-661692973No ratings yet

- Lehman - Et - Al-2017-Rethinking The Biopsychosocial Model of HealthDocument17 pagesLehman - Et - Al-2017-Rethinking The Biopsychosocial Model of HealthAlejandroNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual SepmDocument14 pagesLab Manual SepmPOOJA P RAJ0% (1)

- Political Ideas and Ideologies - Lesson 2Document33 pagesPolitical Ideas and Ideologies - Lesson 2MissMae QAT100% (1)

- 3 Recent Trends and Constraints in Nursing ResearchDocument18 pages3 Recent Trends and Constraints in Nursing Researchfordsantiago01No ratings yet

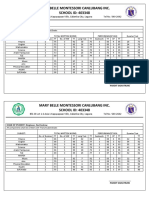

- Mary Belle Montessori Canlubang Inc. SCHOOL ID: 403348Document18 pagesMary Belle Montessori Canlubang Inc. SCHOOL ID: 403348Jep Jep PanghulanNo ratings yet

- Analisa Kinerja Dengan Pendekatan Balanced ScorecardDocument9 pagesAnalisa Kinerja Dengan Pendekatan Balanced ScorecardDinar SaharaniNo ratings yet

- Attention and PerceptionDocument10 pagesAttention and PerceptionSalami ibrahimNo ratings yet

- Critically Examined The Relationship Between Community Psychology and Other Discipline You KnowDocument2 pagesCritically Examined The Relationship Between Community Psychology and Other Discipline You KnowMisbahudeen AbubakarNo ratings yet

- The Needs of Training and Development: Prepared By: Benjamin S. AndayaDocument31 pagesThe Needs of Training and Development: Prepared By: Benjamin S. AndayaBench AndayaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Astri PDFDocument5 pagesDaftar Pustaka Astri PDFSri wardaniNo ratings yet

- BasicDocument3 pagesBasicTuesday EscabarteNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 2ndCO USING TIME EXPRESSIONSDocument5 pagesENGLISH 2ndCO USING TIME EXPRESSIONSmaricel ludioman100% (3)

- Lesson Plan Week 5 - Maths Y2Document5 pagesLesson Plan Week 5 - Maths Y2Sajida NirshadNo ratings yet

Rm3 Enterep212 Entrep Mind Pre Final Period

Rm3 Enterep212 Entrep Mind Pre Final Period

Uploaded by

chenyuisha0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views11 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views11 pagesRm3 Enterep212 Entrep Mind Pre Final Period

Rm3 Enterep212 Entrep Mind Pre Final Period

Uploaded by

chenyuishaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 11

RM3 ENTEREP212 N7 ENTREP MIND

PRE-FINAL PERIOD

Entrepreneurial Scripts and Entrepreneurial Expertise: The

Information Processing Perspective

The term “ expert script” refers to highly developed,

sequentially ordered knowledge in a specific field (Glaser,

1984; Leddo and Abelson, 1986; Lord and Maher, 1990; Read,

1987). Scripts are defined as commonly recognized

sequences of events that permit rapid comprehension of

expertise-specific information by experts (Schank and

Abelson, 1977), as cited in Abbott and Black, 1986. An expert

script is most often acquired through extensive real-world

experience, and it dramatically improves the information

processing capability of an individual (Glaser, 1984), although

not without the danger of promoting thinking errors such as

stereotypic thinking, the inhibition of creative problem

solving, and the discouragement of disconfirmation of the

script in the face of discrepant information (Walsh, 1995).

Expert information processing theory generally treats the

terms knowledge structure and expert script as synonymous.

Sequences and Norms The most general element of expert

script structure is based upon unique differences in the

knowledge organization of experts versus novices. Glaser

suggests that the knowledge of novices is topical versus

contextual; i.e., it is organized around the literal objects

explicitly apparent in a problem statement. Hence,

limitations in the thinking of novices are due to their inability

to infer further knowledge from the literal cues in expertise-

specific problem statements. Conversely, experts’

knowledge is organized around principles and abstractions

that (1) are not apparent in problem statements, (2) subsume

literal objects, and (3) derive instead from a knowledge about

the application of particular subject matter, leading experts

to generate relevant inferences within the context of the

knowledge structure or script that they have acquired (Glaser,

1984). Thus expert scripts specify context, because (1) they

have a “sequential structure” and (2) they incorporate the “

norms” that guide the actions of experts in their area of

specialty (Leddo and Abelson, 1986: 107). Accordingly, the

first, general specification of the structure of an expert script

is that it should include both sequences and norms.

In interpreting the results of three studies that seek experts’

explanation for script failure, Leddo and Abelson (1986)

identify an opportunity to explore the components of

expertise. Their findings suggest three possible components

of expertise that might be observed empirically in making

distinctions between experts and novices. Essentially, Leddo

and Abelson propose that the opportunity to distinguish

novices from experts occurs at two key points in expertise-

specific situations, when the performance of an expert script

(an attempt to utilize expertise) might fail. These points occur

either (1) at the time of script “entry” or (2) as individuals

engage in “doing” the things that serve the main goal of a

script (e.g., take steps to form a new organization). Script

“entry” depends on “...having the objects in question” (Leddo

and Abelson, 1986, 121). For example, an expert helicopter

pilot requires a helicopter, an expert seismic geologist a

seismograph, an expert trauma physician a well-equipped

emergency room. Script “doing” means accomplishing the

main action and achieving the purpose of the script. “Doing”

depends on two subrequirements: ability and willingness.

Ability is defined as possessing the rudimentary techniques

and skills necessary to a specialized domain (e.g., closing the

deal may depend on one’s persuasive skill) (Leddo and

Abelson, 1986, 121). Willingness, in turn, is defined as the

propensity to act.

In the case of entrepreneurs, the “Entry” and “Doing” action

thresholds of expert information processing theory parallel

the theoretical (Shapero, 1982) and empirical (Krueger, 1993)

action thresholds that explain individual intentions to form a

new venture. Thus “Entry” (the beginning processes of

organizational formation) depends on feasibility – specifically

on arrangements resources from that environment such as

capital, opportunity, and contacts, and “Doing” depends on a

combination of ability and willingness. Since expert

information processing theory suggests that expertise results

from an individual’s use of an expert script, it can be argued

that new venture formation expertise ought to be related to

individual scripts containing the “Entry”-based component

“feasibility” and the “Doing” components “ability” and

“willingness.” It follows that discrimination among new

venture formation experts and between experts and novices

should be possible using these constructs.

Motivations, Emotions, and Entrepreneurial Passion

The study of motivation can be traced to the early works of

Freud (1900, 1915) in which his use of the term “instincts”

operates a great deal like “drives” or “motivations” (Deutsch

and Krauss, 1965). For Freud (1915), “instincts” were

persistent pressures to change an internal state by external

activities, often via “unconscious mental activity” (Deutsch

and Krauss, 1965). To Freud, instincts (or motivations)

influenced behavior on both conscious and unconscious

levels. Given that one’s most fundamental drivers are

biologically based, it follows that obtaining what is necessary

for survival is a strong human motivation. That basic

motivation is inherent in all humans and makes achieving

success and avoiding failure a necessity. Since the beginning

of time we, as the collective human race, are motivated to

survive. In its most basic form, motivation, as defined by

Maslow (1946), is the human drive to satisfy the body’s need

for survival, with its highest form reflected in achievement

motivation (Ach). Achievement motivation is a research

stream initially fostered by Atkinson (1957, 1964). A

unidimensional approach was taken by McClelland and

Winter (1969), and a multi-dimensional approach was also

taken by Spence and Helmreich (1978) and Carsrud et al.

(1989). For example, Atkinson (1957, 1964) builds his model

of achievement motivation on his prior theory, levels of

aspirations (clearly something entrepreneurs often do and

yet which few entrepreneurship researchers have directly

studied). Could aspiration level explain why some people

choose to build high growth firms and others choose life-style

firms? His theory addresses the tendency of individuals to

both achieve success (creating a successful venture) and

avoid failure (starvation).

Survival-oriented motivation can be seen in the “necessity

entrepreneur” identified in the Global Entrepreneurship

Monitor (GEM) studies (Reynolds et al. 2002). This type of

entrepreneur is more concerned with avoiding the failure of

starvation than other types of entrepreneurs. We have

evolved a long way from the days of cavemen (and

cavewomen) and in our modern world, we obtain what we

need for survival by working

to obtain the monetary means required to purchase what we

need and want, thus the evolution of motivation. Most people

do this by working as an employee for a corporation or other

types of organization. They have a particular role to play

within that setting and specific tasks they must fulfill in order

to be rewarded a predetermined amount of money (hence

work or task motivation) (Pinder, 1984, 1998). Whether or not

the individual likes the job that he or she must perform or the

company in which he or she works can sometimes take a

backseat to the more pressing issue of making money in order

to support one’s self and family. However, not everyone fits

into the role of an employee working for another person within

an organization. Some decide to blaze their own trail through

the business world as entrepreneurs, hence the

“opportunistic entrepreneur” of the GEM studies (Reynolds et

al., 2002) who is focused on the achievement of success

through exploiting an opportunity for some form of gain. Here

the intention of the entrepreneur and the pursuit of the

recognized opportunity are critical. Obviously, the question of

what motivates the pursuit of an opportunity should be of

interest to researchers, entrepreneurs creating ventures, and

policy makers wishing to foster entrepreneurial behaviors.

Clearly, commercially oriented entrepreneurs are working to

earn money, power, prestige, and/or status. But these might

not be the only “rewards” or “motivations” they are striving

for, as anyone working with either social or biotechnology

entrepreneurs will attest to. The search for a disease cure

may be a far more powerful motivator than making money,

especially if it is the entrepreneur’s child that has the disease.

Entrepreneurs have the same motivations as anyone for

fulfilling their needs and wants in the world; however, they use

those motivations in a different manner – they create ventures

rather than just work in them.

We still have much to learn about the entrepreneur,

especially with respect to the role of motivation in the

entrepreneur. The sociologist Homans (1961) proposed the

motivational principles of hedonism and the theory of the

“economic man,” which still have relevance to the study of

mankind, especially the entrepreneur. The utilitarian

emphasis on the role of “reward,” “drive reduction,”

“pleasure,” “reinforcement,” or “satisfiers,” as proposed by

psychological theories of motivation in learning (Deutsch and

Krauss, 1965), can still inform the entrepreneurial researcher

and guide their research endeavors. McClelland (1985)

summed up the role of motives, values, and skills as those

factors that determine what people do in their lives. We

believe that entrepreneurship researchers have yet to

adequately tie those three factors together although social

values clearly impact the development of social ventures and

not-for-profit organizations.

Drive Theories and Incentive Theories

Traditionally, motivation has been studied in order to answer

three kinds of questions: (i) What activates a person? (ii) What

makes him, or her, choose one venture over another? and (iii)

Why do different people respond differently to the same

stimuli? These questions give rise to three important aspects

of motivation: activation, selection-direction, and

preparedness of response (Perwin, 2003). Existing

motivational theories can be divided roughly into drive

theories and incentive theories. Drive theories suggest that

there is an internal stimulus, e.g., hunger or fear, driving the

person and that the individual seeks a way to reduce the

resulting tension. The need for tension reduction thus

represents the motivation (Freud, 1924; Murray, 1938;

Festinger, 1957). On the other hand, incentive theories

emphasize the motivational pull of incentives, i.e., there is an

end point in the form of some kind of goal, which pulls the

person toward it, such as achievement motivation in the

entrepreneur (Carsrud et al., 1989). In other words, in drive

theories the push factors dominate, while in incentive

theories the pull factors dominate. The cognitive approach to

personality psychology has traditionally emphasized the pull

factors and the incentive nature of motives (Perwin, 2003).

Diversity and Complexity of Motivational Theories

Fisher (1930) noted that there are fundamentally two schools

of motivational theories, one based in economics and the

other rooted in psychology. These have been in conflict with

each other for decades. Recently, Steel and König (2006) and

Wilson (1998) called for the use of consilience, which they

describe as the linking of facts and fact-based theory across

disciplines to create a common framework between the two

schools. We also see this lack of consilience in

entrepreneurship research with respect to its view of the

entrepreneur. This might account for the lack of progress in

our understanding of the entrepreneurial mind and how it ties

to the venture creation process. If the multi-disciplinary

nature of entrepreneurship research is to return to looking at

motivation as an explanatory factor in entrepreneurial

behavior, it must also bridge the wide variety of theories of

motivation and tie them to environmentally oriented theories

like RBV (Penrose, 1959). Likewise, any motivational and

resource-based models adopted by entrepreneurship

researchers must also have some temporal components as

there is an inherent time dimension in opportunity

recognition and firm creation.

Entrepreneurship could become indebted to the recent work

of Steel and König (2006) on motivation. They have brought

together various theories of motivation as applied in

economics, management, and psychology (with a time

dimension) into what they call temporal motivational theory

(TMT). In addition, Locke and Latham (2002, 2004) have

married task motivation and goal setting in their recent

commentaries. What is interesting is that these two

approaches to motivation have yet to be adopted by

entrepreneurship researchers.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations in Entrepreneurs

Although motivation can exist in many forms, it ultimately

comes from two places: from inside one’s self and from one’s

outside environment. Motivation could come internally from

the emotional high one feels when launching a firm or

externally from the admiration of society or money received

from the venture. That is, motivation can be intrinsic and

extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation refers to a personal interest in

the task, e.g., achievement motivation (Carsrud et al., 1989),

and extrinsic motivation refers to an external reward that

follows certain behavior (Perwin, 2003; Nuttin, 1984).

Therefore, intrinsic motivations include a large proportion of

self-development and self-actualization. Note, however,

intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are not mutually exclusive;

one can be motivated by both to perform an act (Nuttin, 1984;

Elfving, 2008). Ryan and Deci (2000) view motivation as the

core of biological, cognitive, and social regulation. They

further state that it involves the energy, direction, and

persistence of activation and intention. To help better

understand the role of both intrinsic and extrinsic

motivations, Ryan and Deci (2000) take into account

selfdetermination theory (SDT). SDT spotlights the

importance of one’s inner-evolved resources for personality

development and behavioral self-regulation. Through this

theory, Ryan and Deci (2000) empirically identified three

inherent psychological needs that are necessary for self-

motivation and personality integration. These are the need for

competence, relatedness, and autonomy. If these needs are

satisfied within an individual concerning a particular act, they

will be more inclined to persist at completing the task with

intrinsic motivation. Conversely, if these needs are not fully

met, they will be more likely to be extrinsically motivated by

external factors (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Of course, extrinsic

and intrinsic motivations can occur together, but Ryan and

Deci point to SDT in helping to determine the primary

motivator. Applied to entrepreneurs, the extent to which their

venture fulfills the needs defined by SDT will contribute to

their intrinsic and extrinsic motivation levels.

(TO BE CONTINUED)

You might also like

- Example of Knowledge Management Exam QuestionsDocument23 pagesExample of Knowledge Management Exam QuestionsZhongyi Li80% (5)

- What Happened Before The Organization? A Model of Organization FormationDocument10 pagesWhat Happened Before The Organization? A Model of Organization Formationaftab alamNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5: Breeding Gazelles Competencies: 5.1. A Born or Made Perspective of EntrepreneursDocument25 pagesChapter 5: Breeding Gazelles Competencies: 5.1. A Born or Made Perspective of Entrepreneursmilton04No ratings yet

- Ent Opp SearchDocument25 pagesEnt Opp SearchTanmay SharmaNo ratings yet

- Kumari-2018-SSRN Electronic JournalDocument9 pagesKumari-2018-SSRN Electronic JournalAudree ChaseNo ratings yet

- OpportunitiesDocument31 pagesOpportunitiesPrabha KaranNo ratings yet

- Defining Entrepreneurship - Competing PerspectivesDocument18 pagesDefining Entrepreneurship - Competing Perspectiveseddygon100% (2)

- Knowledge Entrepreneurship: Knowledge Entrepreneurship Describes The Ability To Recognize or Create An Opportunity andDocument6 pagesKnowledge Entrepreneurship: Knowledge Entrepreneurship Describes The Ability To Recognize or Create An Opportunity andhmehtaNo ratings yet

- Employee Motivation and Performance: Obiekwe NdukaDocument32 pagesEmployee Motivation and Performance: Obiekwe NdukaRitika kumariNo ratings yet

- Careers of Perspective: As Repositories Knowledge: A New On Boundaryless CareersDocument20 pagesCareers of Perspective: As Repositories Knowledge: A New On Boundaryless CareersAyyutyas IstiiqomahNo ratings yet

- A Stupidity-Based Theory of OrganizationsDocument27 pagesA Stupidity-Based Theory of OrganizationsJohn Thornton Jr.No ratings yet

- A Situated Metacognitive Model of The Entrepreneurial MindsetDocument13 pagesA Situated Metacognitive Model of The Entrepreneurial MindsetDih LimaNo ratings yet

- Clustering Competence in EIDocument36 pagesClustering Competence in EIHemanth GoparajNo ratings yet

- Career Development TheoryDocument7 pagesCareer Development TheoryNorashady100% (1)

- 2000 Lee Knowledge Value Chain 783 Knowledge ValuDocument11 pages2000 Lee Knowledge Value Chain 783 Knowledge ValuLuzMary Mendoza RedondoNo ratings yet

- Krueger - 2003 - The Cognitive Psychology of EntrepreneurshipDocument36 pagesKrueger - 2003 - The Cognitive Psychology of EntrepreneurshipAnonymous nQB4ZCNo ratings yet

- NORC at The University of Chicago, Society of Labor Economists, The University of Chicago Press Journal of Labor EconomicsDocument33 pagesNORC at The University of Chicago, Society of Labor Economists, The University of Chicago Press Journal of Labor EconomicsrezasattariNo ratings yet

- EntrepreneuriatDocument12 pagesEntrepreneuriatencglandNo ratings yet

- Theories and Assumptions of Entrepreneurship - 0Document16 pagesTheories and Assumptions of Entrepreneurship - 0Clarissa Puguon-maslang PallayNo ratings yet

- Small Business, Innovation, and EntrepreneurshipDocument6 pagesSmall Business, Innovation, and EntrepreneurshipastiNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Role of The Cognitive VariablesDocument25 pagesEntrepreneurial Intentions: The Role of The Cognitive VariablesZeeshan AhmadNo ratings yet

- Organisational DesignDocument37 pagesOrganisational Designpayal sachdevNo ratings yet

- Functionnal StupidityDocument27 pagesFunctionnal StupidityBlaise DupontNo ratings yet

- World's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisherDocument24 pagesWorld's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisheranissaNo ratings yet

- 2000 Lee Knowledge - Value - Chain - 783 - Knowledge - ValuDocument11 pages2000 Lee Knowledge - Value - Chain - 783 - Knowledge - ValuLuzMary Mendoza RedondoNo ratings yet

- A Prescriptive Analysis of Search and Discovery : James O. FietDocument20 pagesA Prescriptive Analysis of Search and Discovery : James O. FietCelina LimNo ratings yet

- Written Assignment Unit 3Document5 pagesWritten Assignment Unit 3Patrice ZombreNo ratings yet

- Theories of Entrepreneurship (14.8.23)Document25 pagesTheories of Entrepreneurship (14.8.23)Himanshu SahdevNo ratings yet

- MOG 2 - Topic 12 - MotivationDocument13 pagesMOG 2 - Topic 12 - MotivationAtif DeewanNo ratings yet

- Transitioning From Hierarchical Bureaucracies Into Adaptive Self-Organizing: The Necessity of Intrinsic Motivation and Self-DeterminationDocument29 pagesTransitioning From Hierarchical Bureaucracies Into Adaptive Self-Organizing: The Necessity of Intrinsic Motivation and Self-DeterminationAntti SnellmanNo ratings yet

- 14: Emotional - Intelligence - As - A - Tool - For - SucDocument27 pages14: Emotional - Intelligence - As - A - Tool - For - SucCarlis Gazzingan100% (1)

- Strategic Resource Management Is Explored Further by Cassia andDocument5 pagesStrategic Resource Management Is Explored Further by Cassia andKimberly JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Work Based ProposalDocument17 pagesWork Based ProposalSteve Mclean100% (1)

- The Knowledge Spillover Theory of EntrepreneurshipDocument37 pagesThe Knowledge Spillover Theory of EntrepreneurshipBipllab RoyNo ratings yet

- Organizational Expatriates' Career Success Aspirations and The Influence of Nationality, Age, and Gender: An Exploratory StudyDocument16 pagesOrganizational Expatriates' Career Success Aspirations and The Influence of Nationality, Age, and Gender: An Exploratory StudyjulianaLatuihamalloNo ratings yet

- Intellectual CapitalDocument12 pagesIntellectual Capitaltramo1234100% (4)

- ET&PDocument15 pagesET&PrejeeeshNo ratings yet

- Prior Knowledge and The Discovery of Ent PDFDocument22 pagesPrior Knowledge and The Discovery of Ent PDFThu LeNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument44 pagesResearch PaperElijah PerolNo ratings yet

- Holsapple y Joshi (2002) Knowledge ManagementDocument19 pagesHolsapple y Joshi (2002) Knowledge ManagementMercedes Baño HifóngNo ratings yet

- Tacit Knowledge and Knowledge ConversionDocument19 pagesTacit Knowledge and Knowledge ConversionFrancesco CassinaNo ratings yet

- A Knowledge-Based Theory of The Firm To Guide Strategy FormulationDocument18 pagesA Knowledge-Based Theory of The Firm To Guide Strategy FormulationDaniloOronozNo ratings yet

- Creativity in Research and Development Environments: A Practical ReviewDocument17 pagesCreativity in Research and Development Environments: A Practical ReviewIvy BeeNo ratings yet

- Sharma and Chrisman 1999Document18 pagesSharma and Chrisman 1999Ayouth Siva Analisis StatistikaNo ratings yet

- Academy of ManagementDocument26 pagesAcademy of ManagementEleonora VintelerNo ratings yet

- Kudesia - 2015 - Mindfulness and Creativity in The WorkplaceDocument23 pagesKudesia - 2015 - Mindfulness and Creativity in The WorkplaceTheLeadershipYogaNo ratings yet

- Social Structural Characteristics of PsyDocument23 pagesSocial Structural Characteristics of PsyYanuar Rahmat hidayatNo ratings yet

- Moberg, D. J. (N.D.) - Managerial Wisdom. The Next Phase of Business Ethics: IntegratingDocument5 pagesMoberg, D. J. (N.D.) - Managerial Wisdom. The Next Phase of Business Ethics: Integratingsnas2206No ratings yet

- A Psychological Model of Entrepreneurial BehaviorDocument12 pagesA Psychological Model of Entrepreneurial BehaviorSamant Khajuria0% (1)

- OFAD-115-MOTIVATION-PRFORMANCE-REWARDS Lesson 8Document3 pagesOFAD-115-MOTIVATION-PRFORMANCE-REWARDS Lesson 8RICHELLE CASTAÑEDANo ratings yet

- Herzberg's TheoryDocument15 pagesHerzberg's TheoryBeezy Bee100% (1)

- Language TeachingDocument33 pagesLanguage TeachingMar'atun SholekhahNo ratings yet

- Anh Truong - Research Methodology1Document8 pagesAnh Truong - Research Methodology1Tram AnhNo ratings yet

- WICS: A Model of Educational Leadership: by Robert J. SternbergDocument7 pagesWICS: A Model of Educational Leadership: by Robert J. SternbergSuvrata Dahiya PilaniaNo ratings yet

- L01 Career Theories OverviewDocument19 pagesL01 Career Theories Overviewdannybmc12No ratings yet

- Journal of Business VenturingDocument17 pagesJournal of Business VenturingmehdiNo ratings yet

- Workbook & Summary - Range - Based On The Book By David EpsteinFrom EverandWorkbook & Summary - Range - Based On The Book By David EpsteinNo ratings yet

- The Power of Minds at Work (Review and Analysis of Albrecht's Book)From EverandThe Power of Minds at Work (Review and Analysis of Albrecht's Book)No ratings yet

- Task 1 PDFDocument11 pagesTask 1 PDFRisaaNo ratings yet

- Social Justice Understanding Health Equity VS Health EqualityDocument1 pageSocial Justice Understanding Health Equity VS Health Equalitygio gonzagaNo ratings yet

- Project Discover: An Application of Generative Design For Architectural Space PlanningDocument9 pagesProject Discover: An Application of Generative Design For Architectural Space PlanningMatthew StewartNo ratings yet

- Topic 5 Multicultural Diversity in TourismDocument4 pagesTopic 5 Multicultural Diversity in TourismNikki BalsinoNo ratings yet

- Villones Table of ContentsDocument5 pagesVillones Table of ContentsBevsly VillonesNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Human DevelopmentDocument3 pagesModule 1 Human DevelopmentMish Lim100% (1)

- Local Media255311538547502585Document7 pagesLocal Media255311538547502585Kyla Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Tools For The Elaboration of Global Marketing Strategy (1) Globlal MKT 5Document48 pagesTools For The Elaboration of Global Marketing Strategy (1) Globlal MKT 5Kiara BaldeónNo ratings yet

- Match LettersDocument43 pagesMatch Lettersshahzad khanNo ratings yet

- Detecting Sarcasm in Text - An Obvious Solution To A Trivial ProblemDocument5 pagesDetecting Sarcasm in Text - An Obvious Solution To A Trivial ProblemsiewyukNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 The Voyage Through The Life SpanDocument9 pagesChapter 9 The Voyage Through The Life SpanMaricris Gatdula100% (1)

- Time Table MCS Fall-19Document8 pagesTime Table MCS Fall-19Aiman KhanNo ratings yet

- ICT 3416 Introduction To Knowledge Management COURSE OUTLINEDocument4 pagesICT 3416 Introduction To Knowledge Management COURSE OUTLINEOkemwa JaredNo ratings yet

- Learning Area Grade Level Quarter Date I. Lesson Title Ii. Most Essential Learning Competencies (Melcs) Iii. Content/Core ContentDocument4 pagesLearning Area Grade Level Quarter Date I. Lesson Title Ii. Most Essential Learning Competencies (Melcs) Iii. Content/Core ContentAlvin PaboresNo ratings yet

- Object Detection With Deep Learning: A ReviewDocument21 pagesObject Detection With Deep Learning: A ReviewDhananjay SinghNo ratings yet

- Kuliah Ke 4 Proses Identifikasi Risiko Dengan Berbagai MetodeDocument48 pagesKuliah Ke 4 Proses Identifikasi Risiko Dengan Berbagai MetodeINDAH PURNAMA SARI MARDJUNINo ratings yet

- Final Case Construction For Cep891 Jie XuDocument9 pagesFinal Case Construction For Cep891 Jie Xuapi-661692973No ratings yet

- Lehman - Et - Al-2017-Rethinking The Biopsychosocial Model of HealthDocument17 pagesLehman - Et - Al-2017-Rethinking The Biopsychosocial Model of HealthAlejandroNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual SepmDocument14 pagesLab Manual SepmPOOJA P RAJ0% (1)

- Political Ideas and Ideologies - Lesson 2Document33 pagesPolitical Ideas and Ideologies - Lesson 2MissMae QAT100% (1)

- 3 Recent Trends and Constraints in Nursing ResearchDocument18 pages3 Recent Trends and Constraints in Nursing Researchfordsantiago01No ratings yet

- Mary Belle Montessori Canlubang Inc. SCHOOL ID: 403348Document18 pagesMary Belle Montessori Canlubang Inc. SCHOOL ID: 403348Jep Jep PanghulanNo ratings yet

- Analisa Kinerja Dengan Pendekatan Balanced ScorecardDocument9 pagesAnalisa Kinerja Dengan Pendekatan Balanced ScorecardDinar SaharaniNo ratings yet

- Attention and PerceptionDocument10 pagesAttention and PerceptionSalami ibrahimNo ratings yet

- Critically Examined The Relationship Between Community Psychology and Other Discipline You KnowDocument2 pagesCritically Examined The Relationship Between Community Psychology and Other Discipline You KnowMisbahudeen AbubakarNo ratings yet

- The Needs of Training and Development: Prepared By: Benjamin S. AndayaDocument31 pagesThe Needs of Training and Development: Prepared By: Benjamin S. AndayaBench AndayaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Astri PDFDocument5 pagesDaftar Pustaka Astri PDFSri wardaniNo ratings yet

- BasicDocument3 pagesBasicTuesday EscabarteNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 2ndCO USING TIME EXPRESSIONSDocument5 pagesENGLISH 2ndCO USING TIME EXPRESSIONSmaricel ludioman100% (3)

- Lesson Plan Week 5 - Maths Y2Document5 pagesLesson Plan Week 5 - Maths Y2Sajida NirshadNo ratings yet