Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Zemman 1983

Zemman 1983

Uploaded by

Vicky Fernandez AlmeidaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Zemman 1983

Zemman 1983

Uploaded by

Vicky Fernandez AlmeidaCopyright:

Available Formats

Legal Mobilization: The Neglected Role of the Law in the Political System

Author(s): Frances Kahn Zemans

Source: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 77, No. 3 (Sep., 1983), pp. 690-703

Published by: American Political Science Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1957268 .

Accessed: 18/09/2013 20:24

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The American Political Science Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Legal Mobilization:

The NeglectedRole of theLaw in thePoliticalSystem

FRANCESKAHNZEMANS

American Judicature Society

This articleargues that the role of the law in thepolitical systemhas been construedmuch too

narrowly.A reviewof thepoliticalscienceliterature demonstrates an interestin thelaw thatis largely

confined to the making of new laws, social change, and social control. That view implies an

acceptanceof thelegalprofession'sdistinctionbetweenpublic and privatelaw as a reasonableguide

for politicalscientistsin thestudyof law.

A more interactiveview of the law is presented,characterizing legal mobilization(invokinglegal

norms)as a form of political activityby whichthecitizenryusespublic authorityon its own behalf.

Further,thelegal system,structuredto considercases and controversies on an individualbasis,pro-

videsaccess to governmentauthorityunencumberedby the limitsof collectiveaction. Thisform of

public power, althoughcontingent,is widelydispersed.

Considerationof thefactors that influencelegal mobilizationis importantnot only to under-

standing who uses the law, but also as predictorsto the implementationof public policy; with

veryfew exceptions,the enforcementof the laws depends upon individualcitizensto initiatethe

legalprocess. By virtueof thisdependence,an aggregationof individualcitizensactinglargelyin their

own interestsstronglyinfluencestheform and extentof the implementation of public policy and

therebytheallocation of power and authority.

PoliticalScienceViewstheLegalSystem Fromdoctrinal analysisofdecisions (Cushman,

1960)to examination of judicialdecisionmakers

Descriptions of Americangovernment tradi- (Pritchett, 1948;Schmidhauser, 1979),theproc-

tionallyincludea discussionof the role of the essesbywhichtheyareselected(Abraham,1974;

judicial system,and its politicalimportance is Chase, 1972;Grossman,1965),and therelation-

typically acknowledged byreferences to Tocque- ship betweentheirpersonalcharacteristics and

ville's observation that "Scarcelyany political decisions (Goldman,1964;Nagel,1962;Schubert,

questionarisesin the UnitedStatesthatis not 1965),thefocusof politicalscienceattention to

resolved, sooner or later, into a judicial thelegalsystemhas beenon policymaking and

question."Yet the studyof law and the legal case outcomes.Althoughinterestin judicial

system hasbeenperipheral tothestudyofgovern- behaviorhas wanedsubstantially, theparallelin-

ment,withspecialarguments deemednecessary to terest inpolicymaking through thecourtshasnot

justifytheirconsideration as politicalinstitutions.(Horowitz, 1977).Specialattention hasbeengiven

Thus, demonstrated interesthas untilrecently to therole,potential, and limitsof thejudicial

beenconfined largely to thedirectpolicymakingbranchinbreaking newgroundinpubliclawand,

roleof thecourtsin a commonlaw system that morebroadly,in promoting, if not generating,

has both a writtenconstitution and a well- broadsocialchange(Casper,1976;Dahl, 1957;

established traditionof judicialreview.Thisvir- Scheingold, 1974).1 Around this interest has

tuallyexclusive orientation towardlawmakingas grownan entireliterature on theimpactof court

thesolepolitical roleofthecourtsworthy ofstudy decisions(Becker& Feeley,1973;Milner,1971;

is clearfromevena cursory reviewofthepolitical Muir, 1967; Rodgers& Bullock,1972;Wasby,

scienceliterature. 1970).

More recently politicalscientists have turned

theirattentionto the criminaljustice system

Thisis a revisedversionofa paperpresented at the

1980Annual Meeting oftheAmerican PoliticalScience 'There has also been a substantialnormativelitera-

Association. tureon the policymakingrole of the courts,most of it

Theauthor wishestothank Thomas Davies,Herbertwrittenby lawyers.For conflictingviewsof the appro-

Jacob,Michael Lipsky,andStuart Scheingold fortheir priate role of the judiciary in the American govern-

comments onearlierdraftsandMarkPetracca formost mentalscheme,see Bickel (1970), Cox (1976), Green-

ableresearch assistance. berg(1974), Wechsler(1959), and Wright(1971).

690

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1983 LegalMobilization 691

(Casper, 1972; Eisenstein& Jacob, 1977; Feeley, state),has essentially ignoredthe legal system

1979; Heumann, 1978; Wilson, 1975). Although altogether. Thisfactreflects boththeancestry of

thisarea of researchmay appear to be far afield the politicalparticipation literature (in voting

fromthe law-makinginterestexhibitedin earlier studies)and the traditional distinctionbetween

work, thereis an underlyingtheoreticalconnec- law and politics.Participation research has been

tion. First, criminaljustice clearly falls on the oriented to "public"policyand outcomes; itim-

public side of the traditionalpublic-privatelaw plicitlyrequiresa politicalconsciousness, an

dichotomy;like public law generally,it is in- awareness of entry intothepoliticalarenaand a

timatelyconcernedwiththe relationshipbetween desireforan effectbeyondone's personallife

thecitizenand thestate.Further,whethertheter- space.

minologyis "social change" or "social control," A definition of politicalactivitywhichrelies

thepoliticalscienceperspectiveon thelaw has re- uponthepublicmotivation of theactormaybe

mained the same-the action is unidirectional, attractive by virtueof its clarityand simplicity,

emanatingfromstate actors and imposed upon butitwouldexcludemuchofwhatwetraditional-

the citizenry. ly thinkof as politicalactivity. Attempts to use

Even criticsof thepublic-private law distinction thepoliticalsystem to gainpersonalor groupad-

justifya broader considerationof the political vantagemaybe criticized forfailureto consider

role of thejudicial branchin termsof rulemaking thegeneralgood,buttheseattempts arecertainly

(Shapiro, 1972); i.e., it is appropriateforpolitical not dismissedas private or apolitical and

scientiststo studythe legal systemonlyto the ex- therefore beyondthelegitimate concerns ofthose

tentthatthe legal systemperformsessentiallythe attempting to explaintheauthoritative distribu-

same role, although constrained by different tionofsocialvaluables.Indeeda central question

structural apparatus, as the more clearly in American politicalthoughthasbeenthemain-

acknowledgedpoliticalbranchesof government. tenanceof a publicspirit(Arendt,1959;Tocque-

The pervasiveness of thisviewis perhapsmostevi- ville, 1963). The dominantAmericanideology

dent outside the field of public law, where the responds to thisconcern withan underlying faith

most consistentreferencesto the politicalrole of thatthepublicgood willmostlikelybe achieved

the courtsin the mainstreamof politicalscience through an aggregation of theassertion of nar-

are found in the interest-group literature(Key, rowerinterests (Hirschman, 1979).

1958; Truman,1951). But even there,thejudicial Theverynatureofthejudicialprocessblursthe

branchis seen as a last resortin the effortto in- public-private distinctionthat pervades the

fluence the making of public policy.2 Whatever politicalscienceliterature. In a commonlaw

else the law may do has been consideredbeyond systemin whichtherulesare said to emergein

the scope of inquiryby those interestedin the largemeasureout of an aggregation of cases

politicalrole of thelegal systemor in thepolitical broughtforconsideration, the initiation of in-

systemmoregenerally.The core workof thelegal dividualdemands(and not merelyoutcomes)is

system,whichdeals withindividualcases and con- centralto the development of the law. In this

troversies,is by and large left to the so-called common lawsystem, withitscommitment tostare

privatelaw arena,whichis beyondtheboundaries decisis,eachcasehasthepotential to influence all

of politicalconcernand thereforebest left(with subsequent similarcases. This processhas been

theirconcurrence)to the legal academyand pro- described as

fession.3

onein which theclassification

changesas the

PoliticalBehaviorand the is made.Theruleschange

classification as the

Public-PrivateDichotomy areapplied.

rules Moreimportant, arise

therules

outof a process which,whilecomparing fact

creates

situations, therulesand thenapplies

The study of individual participationin the them (Levi,1948,pp.3-4).

polity(thatis, action directedfromcitizento the

in-

reactive

The pointis thatcourtsareessentially

so rules"changeas theyare applied"

stitutions,

2Therehas been some recognitionof interestgroup in responseto claimsmade.Withinthelimitsof

activityto maximizeor minimizetheimplementation of jurisdictionalrulesthatstructureparticipation,

court decisionsas anotherstrategyof group influence individual actuallysettheagendaof the

litigants

(Peltason, 1955). This activitycomes closestto thelegal judicialbranchof government.

mobilizationthat is the topic of this article, but is

limitedby its exclusivefocus on the conscious policy

motivationof recognizedpoliticalgroups. 41tis true that some appellate courts, particularly

3An exceptionis Jacob's (1969) work on delinquent courtsof finalreview,exercisesubstantialdiscretionin

debtors. both the selectionof cases to be heard and issues to be

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

692 TheAmerican

PoliticalScienceReview Vol. 77

In addition, of course, there are the more narrowspace whichhis own legal rightsoccupy.

unusualcases thatbeginas privatemattersof per- ... The generalgood whichresultstherefrom is

sonal interestto the claimantand that,by virtue not onlythe ideal interestthatthe authorityand

majesty of the law are protected, but...

of the court's responseto them,are transformed that the establishedorder of social relationsis

into significant new policy.A prominentexample defendedand assured(Ihering,1879,pp. 68-69).

is the case of Clarence Gideon, the ne'er-do-well

Florida convictsentencedto prison withoutthe The unity of public and private law has been

benefitof counselin his felonydefense(Gideon v. suggested more recently in an inquiry into ad-

Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335, 1963). Withina few ministrativelaw that questions the validity of the

shortyearsof thatdecision,theextentof criminal distinction between private dispute-settling and

defenseand the role and financialburdenof the administrative law. "To what extent," it is asked,

statein providingit had been revolutionized. "does private dispute settlement consist of

The moregeneralpointis thatindividualchoice anything other than the disposition of challenges

and demands on public authorityby invoking to decisions about the use of state power?" (Vin-

legal rightsare closelyinterwoven withthemaking ing, 1978, p. 179). Study of the use of state power

of publicpolicywithoutanyrequisiteinvolvement is, of course, at the core of the political scientist's

by a collectivityor any necessityfora publiccon- task; its direct use by the citzenry as in mobiliza-

sciousness.However,even recognitionof the im- tion of the law, therefore, ought to be of par-

portanceof privatelymotivatedindividualcases ticular concern in a democratic political system.

to the developmentof the law ties theirpolitical

role to a requisitecontributionto rulemaking.A Legal Mobilizationas PoliticalParticipation

muchbroaderconceptualizationis necessaryifthe

fullmagnitudeof thepoliticalrole of thelaw is to Political participation is implied in the very no-

be appreciated. tion of democracy. Whether characterized as serv-

The traditionalpublic law-privatelaw dichot- ing the protection or maximization of interest,

omy, relyingas it does upon the differencebe- providing for self-rule, or as a means of self-

tweentherelationships controlled(i.e., stateto in- realization of one's humanity, political participa-

dividualand individualto individual,respectively) tion has been and continues to be central to demo-

is, like the public motivationaltest of political cratic theory (Arendt, 1959; Bachrach, 1967;

participation,an easybutconceptuallymisleading Dahl, 1961; Fanon, 1965). Although these various

distinctionthatdoes not well servesocial science roles are surely not mutually exclusive, neither are

analysis of the legal system.As Durkheimlong they necessarily mutually dependent. More impor-

ago noted, tant to the concerns expressed here, each of these

goals is potentially available through legal activity

a lawisprivateinthesensethatitisalwaysabout and, it might be argued, more so than from tradi-

individualswhoare present and acting;butso,

tionally acknowledged modes of political partici-

too,alllawispublic,inthesensethatitisa social

function and thatall individuals

are, whatever pation. For unlike other governmental structures,

theirvaryingtitles,functionaries of society. the legal system is structuredprecisely to promote

(Durkheim, 1964,p. 68) individual rather than collective action. Although

that surely limits the precipitousness of change

To takeDurkheim'scharacterization one stepfur- that is likely to occur, it also means that the in-

ther, the individual in realitybecomes a func- dividual citizen does not require the imprimatur

tionaryof the state, who is employinghis legiti- of an annointed group to have access to govern-

mate authorityby usingthe law; thisincludesthe ment authority. The legal system, limited as it is to

so-called private law, which is itselfwrittento real cases or controversies involving directly in-

reflectpublic norms and achieve public goals. jured or interested parties, provides a uniquely

Iheringgoes further and arguesthatthe assertion democratic (as opposed to republican) mechanism

of one's legal rightsis not only an obligationto for individual citizens to invoke public authority

oneself,but a dutyowed to society: on their own and for their benefit. The bulk of

this activity takes place among private citizens

In defending asserts

[theindividual]

legalrights who, in the process of involving legal norms,

and defendsthewholebodyof law,withinthe employ the power of the state and so become state

actors themselves.5

considered.To stressthisproactivebehaviorof the

courts,however,is to committhecommonerrorof 'The state is not dormantin thisprocess. Individual

overemphasis uponuppercourts,whenin mostcasesit participationin the legal systemis highlystructuredby

of the complexjurisdictionalrulesand thecontentof thesub-

is courtsof firstinstancethatare theterminus

legalprocess. stantivelaws thatbenefitsome at theexpenseof others.

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1983 LegalMobilization 693

In thisway the legal systemcan be considered ess by which a legal systemacquires its cases."

quintessentially democratic, although not These definitionsare at once too broad and too

necessarilyegalitarianif the competenceand the narrow.The firstis too broad because it does not

meansto make use of thisaccess to governmental distinguishlaw fromgovernmentpower; thus it

authority is not equally distributed. Despite would, forexample,includeas an act of law the

neglectby political science, the fact is that the burglaryof a psychiatrist'sofficeto obtainDaniel

shareof theoutputof thepoliticalsystemthatin- Ellsberg's case file. Although that perspective

dividualsreceiveis in part determinedby the ex- may be highly recommendedby virtue of its

tentto whichtheymobilizethe law on theirown avoidanceof manyof themostcomplexquestions

behalf.The relianceof some of thedistribution of that have historicallyplagued jurisprudential

social valuables upon individual assertions of thought,it is a conceptualizationthatdistortsthe

public authorityis ultimatelydemocratic,for it common understandingof law as a framework

mitigatessome of the problemsinherentin repre- within which governmentalactors can operate

sentativegovernment, includingthe limitsof col- legitimately,setting limits on governmental

lectiveaction and the difficultyof measuringin- power.7The definitionis too narrowbecause it is

tensityof subjectiveinterest.If the dispersionof unidirectionaland fails to recognizethe interac-

powerprovidesprotectionfromtyranny, thenthe tivenatureof thelaw. Finally,althoughBlack has

potential for every individual to mobilize the done more than anyone to call attentionto legal

law can play an importantrole in democratic mobilizationas a meaningfularea of study,he

governance." definesmobilizationfartoo formalistically and so

Withoutdiminishing eithertherule-making role fails to encompass the breadthof its role in the

of the courtsor the importanceof collectiveac- distributionof governmentalpower among the

tionin politics,scholarlyneglectof thecitizenry's citizenry.

mobilizationof thelaw has contributedto a wide- Althoughdefiningmobilizationas "the process

spread failure to recognize the centralityof by whicha legal systemacquires its cases" seems

individualdemands to the very implementation ratherall-encompassing,Black goes on to make

process that determinesthe benefitsthat citizens the directinvolvementof public actors a prere-

actuallyreceivefromtheirgovernment. quisite to the transformation of an incidentor

As early as 1971 Pound noted that all law is situationinto a "case." In the criminalsystem

limitedby thenecessityof appeal to individualsto thismeans involvementby the police, in the civil

set it in motion.Thus he concludedthat systemtheactual filingof a case in court.The at-

tractiveness of thisdefinitionis its relativeease of

Last and mostof all (law makers)muststudy operationalization.Yet an understanding of cases

howto insurethatsomeonewillhavea motive even so defined is itself necessarilydependent

forinvoking themachinery his

oflawto enforce upon knowledge about those potential cases

ruleinthefaceofopposinginterests in

ofothers which do not enterthe formalsystemand why

it. (Pound,1917,p. 167)

infringing theydo not. Further,and morecloselyrelatedto

the role of the legal systemas a mechanismfor

Despite this and other briefreferencesin the participatorydemocracy,an individualthat in-

literatureto theobvious importanceof therole of vokes the law on his or her own behalf without

litigantsin the legal process,neithertheynor the direct assistance from the formal mechanism

factorsthatinfluencetheirlegalactivityhave been assumes the role of governmentalactor. This

accorded much serious scholarly attention. form of mobilizingpublic authorityis indeed

Black's (1973) work,"The Mobilizationof Law," worthyof inquiry.In addition,it can be argued

is an important exception. Black, however, thatsuccessfullegal mobilizationmaybe substan-

defineslaw as the equivalent of "governmental

tially more efficientthan the interpositionof

social control,"and itsmobilizationas "the proc-

police,prosecutors,and courtsin theimplementa-

tion of the law.

A more useful formulationof legal mobiliza-

tionis providedbyLempert(1976) as "the process

These limitationsimposedin the state'sexerciseof by which legal norms are invoked to regulate

socialcontrol,however, do notdiminish theindepen- behavior" (p. 173). This definitionincludesthe

denceof theindividual to actalone. earlieststages of the mobilizationprocesswhen,

"Theexistenceof a legalstructurethatallowsforin-

dividualmobilizationof thelawis surelynotsufficient

todefinea democratic society.Yettheextenttowhicha

toemploy

isentitled

citizen ofgovernment 7Thisis not to arguethatthelaw playsno rolein

theauthority

by mobilizingthelaw adds to thediffusion of power socialcontrol, to thedominant

butto offera corrective

and therebyto thedemocratic on lawas a mechanism

natureof thepolitical viewthatfocusesexclusively of

system. socialcontrol.

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

694 The AmericanPoliticalScienceReview Vol. 77

in Eastonian terms,desires or wants are trans- initiatedcontacts"would seem to incorporate

formedinto demands,when the public authority legalcontacts.Yet whenit comesto theirdata

inherentin legal norms is firstassertedby the analysis,they,like others,are particularly in-

citizenin thisparticipatory act. Fromthisperspec- terested in attempts to influence governmental

tivelegal mobilizationis not dependentupon the policydecisionsand in collectively oriented out-

use of particularformalstructures.Most impor- comes.In reporting thecorrelations amongcam-

tant,it does not excludeindividualactionand im- paignactivity, communal activity,andvoting they

plicitly recognizes the central role that mere assert:

knowledgeand assertionof legal normshave in

the distributionof public policy. The individual Whatmayholdtheselmodesofactivity to-

citizen can be a true participantin the govern- gether isthatallinvolve somepoliticalconscious-

mentalschemeas an enforcerof the law without ness,someawareness of and concern about

representative or professionalintermediaries. issuesthattranscend theindividual'smostnar-

The model of politicalparticipationthatunder- rowlifespace.Butparochial participationcan

takeplaceintheabsence ofsuchgeneral concern

lies thisconceptualizationincludesan activerole with politicalmatters (Verba & Nie,1972,p. 71).

forthe citizenryin both the makingand the im-

plementationof public policy. In contrast,the Althoughsuch a characterization mightrea-

more traditionalperspectiveon citizenparticipa- sonablyexcludethebulkoflegalactivity fromthe

tion in governancehas been orientedalmost ex- mainarenaof politicalparticipation, it is inap-

clusivelyto policymaking.Verba and Nie (1972, propriateon two different counts. First, it

p. 3) for example, are interestedin democratic substantially narrows thepurview ofpolitical par-

participationas "processesof influencing govern- ticipation as it has beenvariously conceptualized

mentalpolicies,not carryingthemout." Consist- inthetheoretical literature;second,itfailstotake

ent with that view, the crucial question with cotmnizance of the particular difficultyin char-

respectto therelationshipbetweenthecitizenand acterizing publicversusprivateissuesin a legal

the state has been how the preferencesof the system thatis structured to generate rulesoutof

citizensof a societyare aggregatedinto a social an incremental aggregation of individual (largely

choice. Further,accordingto Verba and Nie, it is "private") cases, and throughwhichthe im-

"through participation[that] the goals of the plementation of publicpolicyoftenproceeds.As

societyare set in a way thatis assumed to maxi- a resultit failsto acknowledge theimportance of

mize the allocation of benefitsin a society to citizen-initiated demandsto theactualdistribu-

matchthe needs and desiresof the populace" (p. tionof socialvaluables.

4). However, no such assumptionis warranted.

For althoughtheyclaimthat"the relevantconse- Law as Potential-Rights as Contingent:

quence of participationfor the individualcitizen TheCitizen'sRoleinEnforcement

is what he gets from the government"(p. 9),

along withotherstudentsof participation theyfail "Law," according to SamuelJohnson, "sup-

to acknowledgethatwhatone getsis notthesame plies the weak with adventitiousstrength"

as allocation,forthe latteris onlythe apportion- (Boswell,1791,1969,p. 498).In otherwords,law

mentor designationof government benefits,and conferspower.8In Dahl's (1961) words,the

not theiractual distribution.Althoughwhat one "mantleoflegality" conferred on private citizens

gets is most certainlyrelated to governmental provides themwithpowerpreviously unavailable

allocativedecisions,to a substantialdegreewhat to them.Any new authoritative rule,whether

citizensreceivefromthegovernment is dependent statute, judge-made commonlaw,or administra-

upon the demands they make for theirentitle- tiveregulation, merely provides opportunities. As

ments and upon participationin the policy- an essentially reactive process, thelegalsystem fits

implementation as wellas thepolicy-making proc- an Entrepreneurial market mode;9it is structured

ess. In particular,what the populace actually

receives from governmentis to a large extent

dependentupon theirwillingnessand abilityto

'This is not to deny that the laws stronglyreflect

assertand use the law on theirown behalf. Yet relativepowerpositionsin society,but herethefocusis

legal mobilizationas political demand has been on low as a resourceavailable to the citizenry.

virtuallyignoredby theliterature thatpurportsto

9Recognitionof the relevanceof a marketmodel as

be concernedwithwho getswhat. explanatoryof the actual operationof the legal system

Verba and Nie's definitionof politicalpartici- does not constitutea normativeendorsementof an

pation ("activitiesby privatecitizensaimed at in- idealized view thatan invisibleforceoperatesto form

fluencingactionsof government personnel")does individualjudicial decisions into an optimal body of

not necessarilyexclude legal activity,and the commonlaw precedents(Engel & Steele, 1979,p. 333).

mode of participationthey denote as "citizen- All thatis claimedis thecentralrole in thedistribution

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1983 LegalMobilization 695

so thatbyinvoking thelawprivate citizens playa formsof politicalparticipation, theycan provide

criticalrolein its enforcement. Whatever rights the resourcesto supportthe assertionof in-

areconferred arethuscontingent uponthefactors dividualclaims.For example,Nonetfoundthat

thatpromoteor inhibit decisionsto mobilizethe theunionplayedthisimportant roleinfacilitating

law. theclaimsof theirmembers forworkmen's com-

Ironically it has been sociologists ratherthan pensation (Nonet,p. 9), eventhoughsucha role

politicalscientists who haverecognized thatthe lay outsidethe union contract.Thereis also

legalprocessmakestheindividual a participant in evidencefromothercontexts thatsimilar support

governance ratherthanan objectof governmentforthe assertionof individualclaimsis forth-

(Nonet,1969;Selznick,1969).Selznick'sstudyof comingfrommoreinformal networks. Friends,

thelaw of employment and Nonet'sstudyof the relatives, employers, co-workers, and neighbors

administration ofthestateworkmen's compensa- all playa partinincreasing awareness ofthelegal

tionlawsbytheIndustrial Accident Commission natureof problemsand thustheavailability of

in Californiabothdocument thelegalization of legalremedies (Jacob,1969).In addition theypro-

the administrative process; i.e., enforcementvideguidancein thesearchforand selection of

agenciesprogressively becomepassiverecipientslegalassistance (Curran,1977).

of privately initiatedclaimswithan increasing Suchcitizenparticipation inthelegalprocessis

orientation to the settlement of disputes.Al- typically assumedto be central to private butnot

thoughon one handthatdevelopment mayhave publiclaw; however, thatdistinction is clearerin

theeffect ofdiverting publicpolicygoalsinherent theorythanin practice.Although it is truethat

intheenabling legislation, ithastheadvantage of thestateis authorized to enforce publiclawon its

makinglegalizedpolicyresponsive to individual owninitiative, andthatinprivate lawthatright is

circumstances (Selznick, 1969).1o grantedexclusively to privatecitizens(Black,

Nonetfoundthatthesocialwelfaremodel,in 1973,p. 128),theevidence indicates thatthestate

whichgovernment is activelyto provideservice only rarelyexercisesthatauthority becausein

and distribute benefits, is byitselfunableto ac- general thelegalsystem is structured torespond to

complish theintended ends;in theagencyhe ex- citizen-initiated complaints." Boththegrowth of

amined, legalizationactually facilitatedthe thecriminal law and thecreationof specialized

transformation ofwelfare policyintosecurerights administrative structures have an impactupon

(Nonet,1969,p. 263). In the process,private legalmobilization, butitis largely byvirtue ofthe

citizensbecomeactiveagentsofthegrowth ofthe shifting ofa substantial proportion ofthecoststo

law; insteadof a passiveobjectof thestate,the thepolity.Although thishastheeffect ofmaking

citizenis the demanderof rightsand status. it cheaperand lesscomplicated foran individual

Nonet's conclusion thatthelaw was liberating,to makea claim,thecasespursued bygovernment

freeingthe injuredemployeefromdependence stilldependlargely uponcomplaints fromoutside,

uponagencyandindustry notionsofhisinterests,thatis, on activeparticipation bythecitizenry.

soundscuriously likeFanon's arguments about Anillustrationofjusthowimportant individual

theliberation andself-realization thatcomefrom complainants areinthelegalprocesscanbe found

participation in politics.In both cases citizens in a briefpamphletwritten and circulatedby

transform themselves fromobjects to willful PEER, theProjectonEqualEducationRights, of

participants. theNOW LegalDefenseandEducationFund(to

Participation and thedistribution of demands "monitor enforcement progress underfederal law

in any entrepreneurial schemedepend upon forbidding sexdiscrimination ineducation").The

resources, skill,aggressiveness, and rightscon- pamphlet isaptlytitled"Anyone'sGuidetoFiling

sciousness, noneof whichis evenlydistributed in a TitleIX Complaint."Afterfirstpointing out

society.Becausevirtually all legalrightsin the thedependence ofHEW's civilrights office onin-

UnitedStatesdependuponthecitizento initiate dividualcomplaints, the pamphletgoes on to

the legal process, the distribution of such

resources andaccessto themarecritical. It is here

thatorganizedgroupsplaya centralrole in an

otherwise individualized system, foras withother "For evidenceof the influenceof privatecitizensat

various stages in the criminaljustice system(the most

obviously "public" area of law), see Hagan (1982).

Studies of antidiscrimination statutes, also virtually

universallyattest to the critical role of citizen com-

of legalityplayed by individualdecisionmakersassert- plaints(Berger,1967; Mayhew, 1968). In those excep-

ing theirrightsunderthe law. tional areas in whichgovernmentenforcement is very

'Lowi (1979) similarlydocumentsthe centralrole of proactive,suchas victimlesscrimeand InternalRevenue

citizen-complainantsin thedevelopmentof administra- Serviceregulations,thereis substantialdependenceon

tiveregulationsat the federallevel. informersin lieu of complainants.

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

696 TheAmerican

PoliticalScienceReview Vol. 77

describe,step by step, the process involved,in- aberrations.However,a systemthatis dependent

cludinga sample letterfor filinga Title IX com- upon individualcomplainantscannot easily dis-

plaintand informationabout whereto send it. It criminate

- among these cases. Legal mobilization

carefullyarguesthatthe costs to the complainant and the initiation of complaints with public

are minimaland informsthe readerabout avail- authoritiesis thus dependent on complainant-

able supportgroupsto help preventpossibleanti- related variables rather than offender-related

cipatedharassment.Further,it stressestheimpor- variables.To theextentthatthe bulk of the com-

tance of persistence."DON'T GIVE UP! HEW plaints are individualized, the agency's work

will get around to your case . . [they]probably becomes substantiallyparticularized.'3

won't go ahead unless you say so." Finally,the The importanceof citizenmobilizationof the

directionsstressthe public policy importof an law to its enforcement is furtherreflectedin the

individualcomplaint: continuingdebateoverCongressionaland judicial

authorization of private causes of action. A

HEW's estimation of thepublicdemandforan citizen'srightto filea privatelawsuitin thecourts

endtosexdiscrimination ineducation is basedin eitherto secure compliance directlyor to seek

largeparton thenumber ofTitleIX complaints damages for injuriessufferedby virtueof non-

filed.The morecomplaints HEW receives, the compliance.Proponentsof a strongenforcement

morelikelyit is thatHEW willdevotegreater effort oftendo notwantto relyon suitsby private

energy to enforcing

and resources TitleIX.

citizens as the only mechanismto force com.

The same phenomenon is found, and often pliance. Indeed it has been noted that "the very

criticized,in the enforcementof housing codes origins of administrative agencies lay in

(Mileski, 1971), the criminallaw (Reiss and Bor- dissatisfaction with private litigation as an

dua, 1967), and the work of the Federal Trade undemocraticmechanismfor social choice and

Commission(Cox et al., 1969). Yet thereseemsto control" (Stewart & Sunstein, 1982, p. 1294).

be some reevaluation of its implications.Ten Despite the documented pervasive reliance of

yearsaftertheNader Reporton theFederalTrade regulatory agencies on citizen-complainants

Commissionattackedadministrative agenciesfor (Kagan, 1978), the authorizationto bring com-

actingonlywhenpeople sendlettersof complaint, plaints (and suits if necessary)against violators

Nader himselfseems to have changed his mind constitutesa grantof substantialcontrolto the

about the efficacy,and possiblythe democracy, agency, at least insofar as there is virtually

of reliance upon individual complainants. His unlimiteddiscretionnot to pursuea case. The op-

proposal for the enactment of a Corporate tion of a privatecause of action thus limitsan

Democracy Act (needed "to keep up with the agency'senforcement monopoly.The continuing

economicand politicalevolutionof giantcorpora- debate and the criticisms of private rightsof

tions") places theburdenof enforcement squarely action as usurpationsof legislativeauthoritythat

and solely on individualcitizens. "Rather than "may engenderoverenforcement of regulatory

dependingon a new bureaucracyto police itspro- statutes"(Fein, 1981,p. 23) reflecthow seriously

visions,the ACT would be largelyself-executing. mobilizationof thelaw is takenas a tool of policy

So citizensinjuredby the non-performance of a implementation."4

standard could go to court, not Washington"

(Nader & Green, 1979).12 Understanding Legal Mobilization

Reliance upon citizen-initiatedcomplaints

underminesthe abilityof government agenciesto Having argued the political relevanceof legal

set theirown agendas as authorizedby theirena- mobilizationto boththeindividualcitizenand the

blinglegislation.Althoughtheycan and do select

among cases forparticularattention,agenciesare

bound to respondto complaints.As a result,any "Steele's studyof the consumerfraudsectionof the

enforcementagenda-settingattemptedby a gov- Illinois attorneygeneral's office suggests that little

aggregationof cases In the officestudiedthere

ernmentalagency depends upon the affected was even a change inoccurs. public posturefromone of "rid-

citizenry'sdemandsforimplementation. Agencies ding the State of merchantswho habituallyemploy

would oftenlike to concentratetheireffortson fraud" to "rightingthe wrong and recoveringthe

exposingand pursuingseriousand continuousof- individual'smoneywheneverpossible" (Steele, 1975,p.

fenders, being less concerned with individual 1180).

14Inrecentyearstherightsof citizensto bringlegal ac.

tionto forcecompliancewithstatutesthatare subjectto

"Reliance upon complainantsgoingto courtto imple- agency enforcementhas been the subject of a sub-

mentpublic policymakesjurisdictionalrulesextremely stantialbody of law. See Fein (1981) fora discussionof

important.See, for example, Cannon v. Universityof recentU.S. Supreme Court action; for a more theo-

Chicago, 441 U.S. 677. reticaldiscussionsee Stewartand Sunstein(1982).

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1983 LegalMobilization 697

itis nownecessary

society,

larger toexamine some (Grumet,1970).Theserequirements are botha

thatinfluence

of thefactors theinvoking oflegal resultand partof thegrowing recognition that

norms.Although an in-depthevaluation ofall the childabuseis a socialproblem appropriate forin-

variablesthat influencelegal mobilizationis tervention by the criminallaw. Batteredwives

beyondthe scope of this article,thereare a providea similar example.Although longviewed

number offactors attention

thatmerit andwillbe as a privatematter,with the police actively

consideredin turn;generating legal demands, discouraged frominvolving themselves in intra-

socioeconomicstatus,and theissuespecificity of familialdisputes,a new consciousnesshas

legalmobilization. changedboth the reporting of offensesto the

policeandtheirresponse, insomecasesas a direct

Generating LegalDemands resultof court-endorsed consentagreements.

The complexity of theperception of interests

Therelationship between thelawas written and and theirtransformation intolegaldemandsis il-

thenatureoftheclaimsmadeis nota simpleone. lustrated bytherecent Chicagostrip-search cases.

The traditional view,mostclearlyarticulated by Overa periodofmanyyears,theIllinoisDivision

Pound (1942), holds that conflicting interests of theAmericanCivilLibertiesUnionreceived

(demandsor desires)existwherever a "plurality complaints fromwomenthattheyhadbeenstrip-

of humanbeings. . . come intocontact" (p. 66), searched,in some cases including body-cavity

and thata legal systemstrivesfor order"by searches,afterbeingarrested forminoroffenses

recognizing certainof theseinterests, bydefining bytheChicagoPoliceDepartment. Withonlyin-

the limitswithinwhichthoseinterests shallbe frequent complaints, itwasassumedthatthecases

recognizedand given effect throughlegal wereaberrations, and theywerehandledas in-

precepts"(Pound, 1942,p. 65). Conceptualized dividualabuses.The investigative reporting unit

thisway,thelaw,muchlikethestandard scheme of a local television stationrevealednumerous

of politicalparticipation,responds to and orders incidents, insomecasesinvolving womenstopped

pre-existentinterests,grantinglegalrecognition to forminortraffic violations andtakentothepolice

someand providing a mechanism through which stationbecausetheyhad leftdriver'slicensesat

theycan be secured.Pound statesquite em- home.By priorarrangement, eachof thereports

phaticallythatinterests wouldexistirrespective of broadcastthe telephonenumberof the local

a legalorder(Pound,1942,p. 66). Although that ACLU office, whichhadagreedtosetup a special

conceptualization oflawas an ordering ofexisting hotlineeachevening to provideassistance to vic-

social interestsaccurately describespartof the tims.Hundredsof complaints werereceived.

relationship of law to the largersociety,it is Eventually theIllinoislegislature passeda strip-

misleading becauseit presents as unidirectionalsearchbill thatbarspolicefromstrip-searching

whatis a highly interactiveprocess. personsarrestedfor misdemeanors or traffic

Thereis ampleevidencethatperceptions of violationsunlesstheoffense involves weaponsor

desires,wants, and interestsare themselvesdrugs.The lawsuitfiledbytheACLU on behalf

strongly influenced bythenatureand content of ofthewomenresulted inan injunction againstthe

legalnormsand evolving socialdefinitions of the ChicagoPoliceDepartment and thepayment of

circumstances inwhichthelawisappropriately in- damagesto manyof thewomenplaintiffs (other

voked.Indeedthisis partoftheeducative roleof casesarestillpending). Although thiscaseis also

thelaw(Andenaes,1966).Thus,forexample, the an exampleofindividual incidents generating new

growth ofconsumer protection lawshasgenerated law,interms oflegalmobilization itis mostinter-

demandson publicauthority by changingthe estingas an illustration ofsomeoftheinhibitions

public'sviewof thecircumstances underwhich uponthetransformation of interests or wantsto

theycanreasonably feelwronged andentitled toa demands.The plaintiffs werenotpredominantly

legal remedy.Put anotherway,it changesthe poor nor membersof racial minorities whose

citizenry'sperceptions of theirinterests. failureto use thelawmayhavebeenattributable

In many instances legal mobilizationis to a status-related lack of legal competence

generated notbythewriting of newlaws,butby (Carlin& Howard,1965).One was the former

changingsocial perceptions of the natureof a wifeofa judge.Shame,fear,assumptions thatthe

problem and theappropriateness of theinterven-policeandthelawareoneandthesame,failure to

tionof stateauthority. Assaultand battery, for getanyresponsefromtheinternal investigative

example,are violationsof the criminallaw in divisionof theChicagoPoliceDepartment, and

every state, but only recently has there been a the perception that the legal expense was not

substantial effortto enforcetheselaws in child worththepossiblegain-thesefactors, singlyor

abusecases.Publicandprivate organizations now in combination, keptthewomenfrompursuing

promote thereporting ofsuchcases,withdoctors thesecases. The revelation thatsuch practices

and teachersincreasingly requiredto do so werenot acceptable,thatcomplaints wouldbe

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

698 PoliticalScienceReview

TheAmerican Vol. 77

heard and pursuedby a legitimateorganization, mobilization. Unlike campaign or communal

generateda totallyunexpecteddemand. activities,both of whichmay requirea relatively

The foregoingexamples provide an introduc- large investmentfor a long-term,highriskgain,

tionto legal mobilizationas an interactive process particularizedcontact (and legal mobilization)

thatis quite differentfromPound's conceptuali- may be less costlyin relationto potentialgain.

zation of the relationshipbetweeninterestsand Furthermore,the benefits,if forthcoming,are

law. The viewthatlaw and changingsocial norms moreimmediate.Thus Milbrath'sconclusionthat

as well as individualcircumstancesare centralto personswhose energiesare absorbed in personal

the criticalstep of perceivingand definingsitua- problems are less likely to value political par-

tions or incidentsas legallyactionable also con- ticipationmay say littlemore than thateveryone

trastssharplywithmuch of the recentliterature has only a given quantum of time, energy,and

on legal services.As Brakel(1979, p. 883) notedin resources,and that rationalactorsmustevaluate

a recentreviewof a book representative of that the potential benefits and burdens of action

genre," 'Legal needs' of a populationare talked beforecommitting theirscarce resources.This is

about as if theyweresome objective,measurable, relevantto anycitizenand not onlythoseof lower

meetable entity." That view pervades the legal socioeconomicstatusforwhom prioritiesmay be

servicesliteratureand can be tracedto the influ- set, in part,by theireconomicsituation.Indeed a

ence of Carlin and Howard (1965) and Carlin, reviewof availabledata indicatesthatthereis sub.

Howard, and Messinger (1966). Without dis- stantial rationalityto decisions to mobilize the

countingits substantialmerit,Carlin's work and law.

muchof thesubsequentpush forlegal servicesfor In contrastto theconclusionthatthereis a sim-

the poor implythatknowledgeof the law and its ple inverse relationshipbetween socioeconomic

protections,and thecost and distribution of legal status and use of the legal system (Carlin &

counsel are sufficientto explain the observable Howard, 1965), data thatare more issue specific

patternof legalmobilization.Althoughthereis no show a substantiallymore complex pattern.For

doubt thatthecost of legal advice is a criticalfac- example,whereasa studyof New York accident

tor in mobilizingthe law, it is onlyone of many, victims found that those with higher socio-

and not alwaysthe most important. economic statuswere more likelyto take action,

socioeconomicstatus had the opposite effecton

SocioeconomicStatus and Legal Mobilization the likelihoodof retaininga lawyer(Hunting&

Neuwirth, 1962, p. 68). The reason for this

Both the political participationand the legal apparentinconsistency is thataccidentvictimsof

servicesliteraturesemphasize the importanceof higherstatus were more likelyto use self-help.

socioeconomic status as a predictorof citizens' That, of course, does not mean that legal

activitiesin seeking influenceupon or benefits mobilizationdid notoccur,onlythatlawyerswere

fromthe state. Milbrath,forexample,speaks of not employed.

"persons whose energiesare absorbedin personal In anotherissue-specificstudy, of debtors in

problems as likelyto place littlevalue on par- four Wisconsin cities, Jacob (1969) similarly

ticipationin politics" (Milbrath, 1965, p. 70). found that socioeconomicstatuswas not a very

Indeed most studies of political participation powerful predictor of legal mobilization.

show thatthosewithhigherincome,moreeduca- Although respondents with more education,

tion, and higherstatus occupations participate higher income, and higher-statusoccupations

more(Verba & Nie, 1972,p. 12). Thus Verba and were more likely to score highlyon a judicial

Nie conclude that "the relationshipbetween efficacyscale (Jacob, 1969, p. 121), when it

socioeconomicstatusand overall participationis actuallycame to usingthelaw to theirown advan-

linearand fairlystrong"(p. 130). tage,thesevariableswerenotverypredictive.Not

A disaggregation of theVerba-Niedata demon- surprisingly, although social characteristics

stratesthat the relationshipthey find between helped to distinguishdelinquent debtors from

socioeconomic status and political participation more responsiblecreditusers, theydid not dis-

does nothold acrossall themodesof participation tinguishusers of court services(i.e., bankrupts)

that emergedfromtheirfactoranalysis of par- fromabstainers(i.e., garnishees)(Jacob, 1969,p.

ticipatorybehavior. "Particularizedcontact," a 54). Since goingto a lawyerwas thebestpredictor

citizen-initiatedcontact (with a governmental of active(filingforbankruptcy)vs. passive(being

official)takenforhis or herown benefitdoes not the subject of a garnishment proceeding)

correlate highly with socioeconomic status behavior, these data raise questions about the

(r= .07; forothermodes of participationr ranges validity of generalizing,across differentissue

from.27 to .33). As a noncollectiveaction taken areas, about the relationshipbetweenlawyeruse

on behalf of the individual,this mode of par- (or access to the potentialadvantagesofferedby

ticipation is most closely analogous to legal the law) and socioeconomicstatus.

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1983 LegalMobilization 699

The most fruitfuldata set for examiningthe focus that has substantiallyrestrictedunder-

importanceof issue specificity to the determina- standingof the law as a formof political par-

tion of who mobilizesthe law is reportedin The ticipationand of itsrolein thepolity.Still,it must

Legal Needs of the Public (Curran, 1977). This be recognizedthat issues vary in the extentto

national survey, covering twenty-nineproblem whichit is likelyor in some cases necessarythat

areas (each with a potentialfor legal mobiliza- the public legal apparatusbe employed.

tion),foundthatlawyeruse variesmostbytypeof Table 1 presentsa typologyof issues along a

problem.Althoughtheoverallmean of lawyeruse legal mobilization continuum,encompassinga

does not vary by income, when the data are wide varietyof issues in which the law has a

analyzedby problemarea, substantialdifferences potential role to play. Movement from left to

emerge. For example, high income respondents righton the continuumis increasingly into areas

are less likelythanlow incomerespondentsto use that are more generallyconceptualizedas legal

lawyersin tortsand juvenilematters(p. 153), yet issues and thereforemore likelyto be subject to

highincomeadultsare morelikelyto use lawyers legal mobilization.

in a numberof other problem areas. Similarly, Farthestto therightis themandatorycolumn,a

overall lawyeruse does not varywiththe educa- selectgroup of issues whichby theirverynature

tion of the respondent,but when lawyeruse is requirenot onlythe invokingof legal norms,but

analyzed issue by issue, many differencesare entryintotheformallegal systemand pursuitof a

observed(p. 158). It is beyond the scope of this case to judicial disposition.15

In theseexamples,a

articleto tryto explainthesedifferences.The cen- citizenexplicitly seekstheimprimatur of thestate.

tral point of thesedata for an approach to legal To take a case in point,althoughmarriagesmay

mobilizationas a formof politicalparticipationis dissolveexperientially in a numberof ways,part-

thatinvokingthelaw may occur witha varietyof nersoftenseek directbenefitsfromauthoritative-

goals in mind and that the individual citizen- ly endinga relationshipin a divorceproceeding.

actor's decisionto mobilizethelaw is not dictated These benefitscome mostlyin the formof state

merelyby demographicvariables. Minimallyit protectionof post-marriagebenefits,including,

meansthatlegal mobilization(and perhapspoliti- for example, welfarepayments,the transferof

cal participationmore generally) needs to be property,and the status necessaryto obtain the

evaluated withgreaterspecificitythan has here- imprimaturof the state in a new marriage,yet

toforeoccurred. anotherlegal relationship.As currentlywritten,

the law providesthat this status can be accom-

plished only throughjudicial dissolutionof the

of Legal Mobilization

Issue Specificity maritalrelationship.A similarpointcan be made

withrespectto all of the otheritemsin the man-

The circumstancesunder which the law is datorycolumn in Table 1. Althougheach might

mobilizedand by whom are subject to limitsim- be considered instrumentalto obtaining some

posed by theabilityof thelegal systemto provide othergoal (e.g., settlingdebtsor seekingrevenge),

the desired result. There are at least two issue- in everycase it is the authoritativerulingby the

relatedfactorsthatweighheavilyon thedecision- courtthatis the immediateobject.

making process involved in legal mobilization. The issueslistedin theothercolumnsin Table I

The firstis theextentto whichthegoal soughtre-

are different;for these, the legal systemis only

quires the use of the state legal apparatus. The one of a numberof possiblemeansof obtaininga

second, related factor, is the availability of desired end. Although the emergenceof these

specialized structures,legal and extralegal, to interestsand goals are themselvesinfluencedby

facilitatethe pursuitof particulargoals. Before

thelaw, thelegal apparatusneed not be employed

consideringthese in detail, it is appropriateto in theirpursuit;indeed,theyusuallyare notunless

note thatthisdoes not implythatlegal mobiliza-

otherapproaches fail to achieve the desiredout-

tion is merely a mode of dispute resolution.

come. Yet the breadthof issues over which the

Although disputes may provide the classic or law can be mobilizedis a reflectionof the extent

ideal-typicalwork of the courts,legal mobiliza- to which modernAmerican societyhas become

tion, and much of the work of the public courts, legalized, with even the most intimateof social

oftenoccurswithouta clear disputein the classic

relationshipshavingbecome subject to definition

sense. Thus an examinationof thepoliticalroleof

and influenceby the state.16

the law mustnecessarilyinclude the entirerange

of issuesoverwhichcitizensmobilizethepowerof

the state on theirown behalfand should not be "5Thatmany of these proceedingsare highlyroutin-

limitedto disputesper se. ized and thereforenoncontentiousdoes not in any way

As discussed previously,legal mobilizationis diminishthe necessityto invokethe public law.

also not limitedto directuse of statelegal struc- "See Abel (1979) for a discussionof the progressive

tures; it is preciselythat kind of narrowingof legalizationof numerousareas of social behavior,

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

700 The AmericanPoliticalScience Review Vol. 77

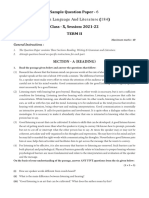

Table 1LFrequencyof Legal Mobilization:The Span of Issues

Never Rarely Sometimes Frequently Mandatory

Social snubs* Intrafamily Consumer Personalinjury(Auto) Divorce

Juvenile Contractdisputes Willsand estates Bankruptcy

Job discrimination Landlord-tenant Sale of house Garnishment

Small claims Probate

Make newlaw

Adoption

*Social snubsmay well be themotivationbehindlegal mobilization,but some otherlegallyrecognizedrightmust

be asserted.

Issues thatare typicallylegal includethose for system.' Experiencewiththe law, the inter-

whichthereis broad social understanding thatthe personalrelationships amongactors,and net-

law plays a potentialrole and provides certain worksaffecting accessto legaladviceareamong

rightsand duties.Includedheretoo are issuesfor othervariablesthatwouldrequireconsideration

whichspecializedstructures have developedwhich in thedevelopment of a modelof legalmobiliza-

minimizethe need for directappeal to the court tion.Thattaskis, however, beyondthescopeof

system.Personal injuriesresultingfromautomo- thisessay.'8Herewe mustsettleformakingthe

bile accidents,for example, are now controlled generalcase thatlegalmobilization is an impor-

largely by insurance companies and personal- tantalbeituniqueformofcitizenparticipation in

injurylawyers.This does not mean thatthelaw is thepolityand thatit is worthy of substantially

not mobilized, because where specialized struc- moreseriousscholarly attentionthanit has been

tures and professionalpersonneldominate,the accorded.

law is knownand playsa sub rosa partin negotia-

tions and settlements(Mnookin & Kornhauser, Conclusion

1979; Ross, 1980). Indeedit is formattersthatfall

intothe "typically"and "mandatory" categories Defining as theactofinvok-

legalmobilization

that lawyersare most likelyto be used in this inglegalnormstoregulate behavior is purposively

country(Curran,1977),and in some cases abroad broadenoughto includetheearliest stageoflegal

as well (Schuyt, Groenendijk, & Sloot, 1976; inthesimplest

activity; case,a particularbehavior

Users' Survey,1979). is demanded byverbalappealto thelaw.Thelaw

However, specialized structuresand lawyers' is thusmobilized whena desireor wantis trans-

specializationare not restrictedto thoseparticular lated into a demandas an assertionof one's

areas; for example,a currentstudyof consumer rights.At thesametimethatthelegitimacy of

grievancesand disputesin Milwaukee has iden- one's claimis groundedin rulesof law, thede-

tifiedno less than nine different forumsforpro- mandcontains threat

an implicit to usethepower

cessingthiskindof dispute(Ladinsky,Macauley, of thestateon one's own behalf.This is most

& Anderson, 1979), althoughnot all forumsare definitelynotto arguethata legalmobilization

specialized exclusivelyto consumerissues. The framework providesa completeanalyticscheme

emergenceof these institutionsas well as con- forunderstanding the law and its place in the

sumeraffairsorganizationsand specializedlegal polity;thatwouldbe bothpresumptuous and in-

expertisein thisarea is, like the law itself,both a accurate,forsurelyitis notthecasethatthelaw

resultof and contributorto the demand forcon- affectsactualbehavioronlyvia citizendemands.

sumer rights.Such organizationsalso increase Muchoftheimpactofthelawresults fromvolun-

knowledge and use of legal rights, thereby tarycompliance thatstemsfrombothan obliga-

facilitatinglegal mobilization. In other words, tionto obeyand a fearof sanction;i.e., a great

theyincreasethisformof politicalparticipationin

much the same way thatmoreobviouslypolitical

organizations have been characterized as "'In particular,jurisdictionalrulescontrollingstand-

generatingand facilitating moretraditionalforms ing,class action rules,and theAmericanruleregarding

of political participation (Almond & Verba, attorneys'fees(makingeach participantin a legal action

1965). responsibleforhis or herown legal fees)play a signifi-

There are of course numerousothervariables cant role in structuringlegal mobilization.

thatare important,indeedcentral,to the mobili- "8I have consideredelsewhere(Zemans, 1982) therole

zation of law. Judicialrules,for example,struc- of many of these factorsin decisions to assert rights

ture and therebylimitparticipationin the legal underlaw.

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1983 LegalMobilization 701

dealofcitizenbehavior is self-regulated, withlaw has a peculiarly democratic nature.Itssuitability

providing a backdropof state-imposed parame- to absorbthedemandsof numerous claimants of

ters.Bycontrast, actuallegalmobilization occurs courselimitsits potentialto promotecentrally

onlywhenthereis an activedemandbased on plannedchange."Moreover, atthesametimethat

legalnorms.Although it mustbe precededbya the legal structure minimizesthe role of the

preceptual stageinwhicha givenincident orsitua- official actor,itassumesand so encourages com-

tion is conceptualizedfirstas calling for a petenceamongthecitizenry at large.

response, andsecondas actionable inthelaw,itis The selective focusherehas beenon thesorely

notuntilthelawisactually invoked thatparticipa- neglectedinteractive natureof the law. More

tionoccurs. specifically, it has beenarguedthatthegovern-

Thisarticlehas concentrated on theindividual mentalpowerinherent in thelaw is usedby the

caseintheso-calledprivate lawarenanotbecause citizenactively and individually to participate in

itis theonlycaseforwhichthisperspective is rele- thepoliticalsystem inorderto receivepartofthe

vant(as documented, bothprosecutors and regu- authoritative distribution of valuables.Law is of

latoryagenciesalso dependheavilyon complain- coursenotthepanaceaofthepowerless, butbyits

antsto initiatecases),butbecausethatis where verynatureit does lend its legitimacy and the

theargument needsto be mademoststrongly. In powerofthestatetowhomever hastheability and

additionto theso-calledprivate lawbeingwritten willingness to use it (Thompson,1975).

to reflectpublicnormsand to achievepublic An interactive viewof thelaw thatacknowl-

goals,itis in thisarenawhereimplementation of edges the universalavailability of government

thelawis mostheavily dependent upontheactive powerto thecitizenry hasimportant implications

participation of theindividual citizen,wherethe forsocialization in a democratic society.Neglect

citizenis mostlikelyto becomeeffectively a func- of legalmobilization as a formof politicalpar-

tionary of thestateby invoking thestate'slegal ticipation is botha result anda partoftheskewin

authority. socialization

political towardtheobligation ofthe

Thereis no question thatbetter mechanisms for citizento obeythelaw.Suchan orientation to the

aggregating claimswould increasethe benefits law is unidirectional (fromstateto citizen),and

received fromthelaw.Butto baseanalyses ofthe presents thelawas merely a mechanism forsocial

relationship betweenlaw and politicsexclusivelycontrol.It doesnotinanywayendorsean active,

on theroleofgroupsorgroupactionwouldbe to assertive participatory citizenry thatis central to a

neglect thepotential fortheindividual citizento democratic society.An interactive approachto

use thelawto hisor herownbenefit without the thelawdictates thepromotion ofa legally compe-

intervention ofa grouporrepresentative. Itwould tentcitizenry as essential ifpublicaimsareto be

also be to ignoretheuniqueroleofthelawinthe realizedin a system in whichtheimplementation

diffusion of publicpoweramongthepopulace.19 of publicpolicyis highly dependent uponmobili-

The bifurcation of researchbetweenpolicy- zationof thelawbyindividual citizens.It is time

makingand policy implementation has left forresearchers to broadentheirscopeand notto

unexplored theroleof citizenparticipation as a be bound by respondents'awarenessof the

linkagebetween them.Further, thisapproachhas "political"natureof theiracts.To do otherwise

resultedin an insufficient understanding of the causesus to remain victims ofthetraditional view

factors important totheimplementation ofpublic thatseparateslaw and politicsand leavesun-

policy.Becauseofthecontingent natureofpublic explored an important areaofinteraction between

policies,whoactually getswhatfromgovernmentcitizens and thestate.

is insignificantpartdetermined bythewillingness

and abilityto invokeexisting lawsand to usethe

powerof the stateto demandcomplianceto References

benefit oneself.20 Structured as itis to providean

individualized mechanism bywhichpowermaybe Abel, R. L. Delegalization: A critical review of its

diffused throughout thesociety, thelegalsystem ideology, manifestationsand social consequences.

Jahrbuchftir Rechtssoziologieand Rechtstheorie,

1979, 6, 27-47.

Abraham, H. J. Justicesand presidents:a political

"9Itmatterslittlethatelitesmay be morelikelyto use historyof appointmentsto theSupremeCourt. New

thelaw thanthemasses.Whatmattersis thatin mobiliz- York: OxfordUniversityPress, 1974.

ingthelaw, as comparedto otherformsof politicalpar-

ticipation,the ordinarycitizen,as an individual,has a

greaterpotentialto receiveauthoritativebenefits. 2"Thisstructurallimiton plannedchangesin thelegal

20Thisfactis recognizedby interestgroupsthatactive- systemalso accounts for a very differentprocess of

ly use the courtsas a forumforthe implementation of policydiffusionfromthatfoundin thelegislativearena.

legal rules. See Gendlin(1980). See Canon and Baum (1981).

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

702 TheAmerican

PoliticalScienceReview Vol. 77

Almond, G., & Verba, S. The civic culture. Boston: Fein, B. E. RecedingU.S. judicial influencemarkedby

LittleBrown, 1965. rulings in 1980-81 term. National Law Journal,

Andenaes, J. The generalpreventiveeffectsof punish- August 17, 1981, p. 23.

ment. Universityof Pennsylvania Law Review, Gendlin,F. A talk withRuck Sutherland.Sierra, Jan-

1966, 114, 949-983. Feb, 1980, pp. 18-22.

Arendt,H. The human condition.Garden City, N.Y.: Goldman, S. Politics,judges and theadministration of

Doubleday, 1959. justice: the backgrounds, recruitment,and deci-

Bachrach,P. The theoryof democraticelitism.Boston: sional tendenciesof thejudges of the U.S. Ct. of

LittleBrown, 1967. Appeals, 1961-4. Ph.D. dissertation,Harvard Uni-

Becker,T., & Feeley,M. (Ed.). The impactof Supreme versity,1964.

Court decisions. New York: Oxford University Greenberg,J. Litigation for social change: methods,

Press, 1973. limitsand role in democracy. The Record of the

Berger,M. Equality by statute: the revolutionin civil Association of the Bar of the City of New York,

rights.Garden City,N.Y.: Doubleday, 1967. 1974, 29, 320.

Bickel,A. The SupremeCourtand theidea ofprogress. Grossman,J. B. Lawyersand judges: theABA and the

New York: Harper & Row, 1970. politicsofjudicial selection.New York: JohnWiley,

Black, D. The mobilizationof law. Journal of Legal 1965.

Studies, 1973, 2, 125-129. Grumet,B. R. The plaintiveplaintiffs:victimsof the

Boswell, J. Life of Samuel Johnson.London: Oxford battered child syndrome.Family Law Quarterly,

UniversityPress, 1969 (Originallypublished,1791.) 1970, 4, 296-317.

Brakel, S. J. (Review of Lawyers and the pursuit of Hagan, J. Victimsbefore the law: a study of victim

legal rights by Handler, Hollingsworth, and involvementin the criminaljustice process.Journal

Erlanger.AmericanBar FoundationResearchJour- of Criminal Law and Criminology, 1982, 73,

nal. 1979, No. 4, 873-883. 317-330.

Canon, B. C., & Baum, L. Patternsof adoption of Heumann, M. Plea bargaining.Chicago: Universityof

tort law innovations:An application of diffusion Chicago Press, 1978.

theory to judicial doctrines. American Political Hirschman,A. 0. Shiftinginvolvements: public interest

Science Review, 1981, 75, 975-987. and privateaction. Princeton,N.J.: PrincetonUni-

Carlin, J., & Howard, J. Legal representation and class versityPress, 1979.

justice. U.C.L.A. Law Review, 1965, 12, 381. Horowitz, D. Courts and social policy. Washington,

Carlin, J., Howard, J., & Messinger,S. Civil justice D.C.: The BrookingsInstitution,1977.

and thepoor: issuesfor sociological research.New Hunting,R., & Neuwirth,G. Who sues in New York

York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1966. City. New York: Columbia UniversityPress, 1962.

Casper, J. D. American criminaljustice. Englewood Ihering,R. von. The strugglefor law. Chicago: Cal-

Cliffs,N.J.: Prentice-Hall,1972. laghan, 1879.

Casper, J. D. The SupremeCourt and nationalpolicy- Jacob, H. Debtors in court: the consumption of

making. American Political Science Review, 1976, government services.Chicago: Rand McNally, 1969.

70, 50-63. Kagan, R. A. Regulatoryjustice. New York: Russell

Chase, H. W. Federal judges: the appointingprocess. Sage Foundation, 1978.

Minneapolis:Universityof MinnesotaPress, 1972. Key, V. 0. Politics, parties and pressure groups.

Cox, A. The role of the Supreme Court in American Springfield,Ill.: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1958.

government.New York: Oxford UniversityPress, Ladinsky, J., Stewart,M., & Anderson, J. The Mil-

1976. waukee dispute mapping project: a preliminary

Cox, E. F., et al. The Nader Report on the Federal report. Disputes Processing Research Program,

Trade Commission.New York: Grove Press, 1969. WorkingPaper 1979-3, 1979.

Curran, B. The legal needs of the public. Chicago: Lempert,R. 0. Mobilizingprivatelaw: an introductory

AmericanBar Foundation, 1977. essay. Law and SocietyReview, 1976,2, 173-189.

Cushman, R. E. Leading constitutionaldecisions. Levi, E. H. An introductionto legal reasoning.

New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1960. Chicago: Universityof Chicago Press, 1948.

Dahl, R. Decision-makingin a democracy:theSupreme Lowi, T. J. The end of liberalism.New York: W. W.

Court as a nationalpolicy-maker.Journalof Public Norton, 1979.

Law, 1957, 6, 279-295. Mayhew,L. H. Law and equal opportunity:a studyof

Dahl, R. Who governs?New Haven, Conn.: Yale Uni- the Massachusettscommissionagainst discrimina-

versityPress, 1961. tion. Cambridge,Mass.: Harvard UniversityPress,

Durkheim,E. The division of labor in society. New 1968.

York: Free Press, 1964. Milbrath,L. W. Politicalparticipation.Chicago: Rand

Eisenstein, J., & Jacob, H. Felony justice. Boston: McNally, 1965.

LittleBrown, 1977. Mileski, M. Policing slum landlords: an observation

Engel, D. M., & Steele, E. H. Civil cases and society: studyof administrative control.Ph.D. dissertation,

process and order in the civil justice system,ABF Departmentof Sociology, Yale University,1971.

ResearchJournal,1979, 2, 295-346. Milner, N. A. The court and local law enforcement:

Fanon, F. The wretchedof theearth.New York: Grove the impact of Miranda. BeverlyHills, Calif.: Sage

Press, 1965. Publications.

Feeley, M. The process is the punishment:handling Mnookin, R. H., & Kornhauser,L. Bargainingin the

cases in a lower criminalcourt. New York: Russell shadow of the law. Yale Law Journal, 1979, 88,

Sage Foundation, 1979. 950-997.

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1983 LegalMobilization 703

Muir,W. Prayerin thepublic schools: law and attitude 1976.

change.Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967. Selznick, P. Law, society,and industrialjustice. New

Nader, R., & Green, M. Corporate democracy. The York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1969.

New York Times,December 28, 1979, p. A27. Shapiro, M. From public law to public policy or the

Nagel, S. Ethnic affiliationsand judicial propensities. "Public" in "Public Law." PS, 1972, 5, 410-418.

Journalof Politics, 1962, 24, 94-110. Steele, E. H. Fraud, dispute, and the consumer:

Nonet, P. Administrative justice. New York: Russell respondingto consumercomplaints. Universityof

Sage Foundation, 1969. PennsylvaniaLaw Review, 1975, 123, 1107-1186.

PEER. Anyone's guide to filinga TitleIX complaint. Stewart,R. B., & Sunstein,C. R. Public programsand

Washington, D.C.: Project on Equal Education private rights. Harvard Law Review, 1982, 95,

Rights,NOW, no date. 1193-1322.

Peltason, J. W. Federal courtsin thepoliticalprocess. Thompson, E. P. Whigs and hunters. New York:

New York: Doubleday, 1955. Pantheon, 1975.

Pound, R. The limitsof effectivelegal action. Inter- Tocqueville, A. de. Democracyin America. New York:

nationalJournalof Ethics, 1917, 27, 150-161. AlfredA. Knopf, 1963.

Pound, R. Social control throughlaw. New Haven, Truman, D. The governmentalprocess. New York:

Conn.: Yale UniversityPress, 1942. AlfredA. Knopf, 1951.

Pritchett,C. H. The Roosevelt court: a study in Users' survey.Royal Commission on Legal Services.

judicial politics and values. New York: Macmillan, Final Report, vol. 2, pp. 173-298, London: Her

1948. Majesty's StationeryOffice, 1979.

Reiss, A. J., Jr., & Bordua, D. J. Environmentand Verba, S., & Nie, N. Participationin America. New

organization:a perspectiveon the police. In D. J. York: Harper & Row, 1972.

Bordua (Ed.). The police: six sociological essays. Vining, J. Legal identity.New Haven, Conn.: Yale

New York: JohnWiley,pp. 25-55, 1967. UniversityPress, 1978.

Rodgers,H. R., Jr.,& Bullock,C., III. Law and social Wasby, S. The impact of the United States Supreme

change, civil rightslaws and their consequences. Court. Homewood, Ill.: Dorsey Press.

New York: McGraw-Hill,1972. Wechsler, H. Toward neutral principlesof constitu-

Ross, H. L. Settled out of court. Chicago: Aldine, tional law. Harvard Law Review, 1959, 73, 1-35.

1980. Wilson, J. Q. Thinkingabout crime.New York: Basic

Scheingold, S. The politics of rights. New Haven, Books, 1975.

Conn.: Yale UniversityPress, 1974. Wright,S. Professor Bickel, the scholarlytradition,

Schmidhauser,J. R. Judges and justices: thefederal and theSupremeCourt. HarvardLaw Review, 1971,

appellatejudiciary. Boston: LittleBrown, 1979. 84, 769-805.

Schubert,G. Thejudicial mind. Evanston, Ill.: North- Zemans, F. K. Frameworkforanalysisof legal mobili-

westernUniversityPress, 1965. zation.AmericanBar FoundationResearchJournal,

Schuyt,K. Groenendijk,K., & Sloot, B. De WegNaar 1982, 4, 911-1071.

Het Recht (The Road to Justice)Deventer:Kluwer,

This content downloaded from 129.171.178.62 on Wed, 18 Sep 2013 20:24:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Parametric - Statistical Analysis PDFDocument412 pagesParametric - Statistical Analysis PDFNaive Manila100% (2)

- Arturo Escobar - Designs For The PluriverseDocument313 pagesArturo Escobar - Designs For The PluriverseReza Mohsin75% (4)

- Peter Gabel and Paul Harris RLSC 11.3Document44 pagesPeter Gabel and Paul Harris RLSC 11.3khizar ahmadNo ratings yet

- New Directions in Comparative Public LawDocument5 pagesNew Directions in Comparative Public Lawabhishek GuptaNo ratings yet

- Zamboni - Legal Realisms. On Law and PoliticsDocument23 pagesZamboni - Legal Realisms. On Law and PoliticstisafkNo ratings yet

- Judicial Myth and RealityDocument27 pagesJudicial Myth and RealityJamie VodNo ratings yet

- Chon - IP and Critical TheoriesDocument11 pagesChon - IP and Critical TheoriesRichard ShayNo ratings yet

- Int J Constitutional Law 2013 Hirschl 1 12Document12 pagesInt J Constitutional Law 2013 Hirschl 1 12jjjvvvsssNo ratings yet

- The Sociology o F L A W in The United States: M. P. BaumgartnerDocument15 pagesThe Sociology o F L A W in The United States: M. P. BaumgartnerNabiella AuliaNo ratings yet

- Hossein, R - Legitimacy, Religion and Nationalism in The Middle East - 1990Document24 pagesHossein, R - Legitimacy, Religion and Nationalism in The Middle East - 1990Tristan Ayela-BeardmoreNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 34.195.88.230 On Sun, 24 Jan 2021 23:40:29 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 34.195.88.230 On Sun, 24 Jan 2021 23:40:29 UTCmarting91No ratings yet

- Postmodernism A ND Constitutive LawDocument7 pagesPostmodernism A ND Constitutive LawEric SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Lieberman IdeasInstitutionsPolitical 2002Document17 pagesLieberman IdeasInstitutionsPolitical 2002Vinícius Gregório BeruskiNo ratings yet

- Institutional Response To Criminalizatio PDFDocument13 pagesInstitutional Response To Criminalizatio PDFPiero Alonso Mori SáenzNo ratings yet

- Legal NormsDocument15 pagesLegal NormsCocobutter VivNo ratings yet

- 2 Law Socy Rev 407Document23 pages2 Law Socy Rev 407kirthana shivakumarNo ratings yet

- Constitutional, Criminal, CivilDocument25 pagesConstitutional, Criminal, CivilMohomoud SarmanNo ratings yet

- Law As A Weapon in Social ConflictDocument17 pagesLaw As A Weapon in Social ConflictFelipe NogueiraNo ratings yet

- Symbolic PowerDocument32 pagesSymbolic PowermarcelolimaguerraNo ratings yet

- Afterword To "Anthropology and Human Rights in A New Key": The Social Life of Human RightsDocument7 pagesAfterword To "Anthropology and Human Rights in A New Key": The Social Life of Human RightsDani MansillaNo ratings yet

- Judicial Authority and The Struggle For An Indonesian RechtsstaatDocument36 pagesJudicial Authority and The Struggle For An Indonesian Rechtsstaatalicia pandoraNo ratings yet

- Oxford Handbooks Online: Law and SocietyDocument20 pagesOxford Handbooks Online: Law and SocietyKaice Kay-cNo ratings yet

- Abuse of Law - Young SmithDocument7 pagesAbuse of Law - Young SmithCarlos SánchezNo ratings yet