Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Effect of Flash Banners On Multiattribute Decision Making: Distractor or Source of Arousal?

The Effect of Flash Banners On Multiattribute Decision Making: Distractor or Source of Arousal?

Uploaded by

22124218Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Effect of Flash Banners On Multiattribute Decision Making: Distractor or Source of Arousal?

The Effect of Flash Banners On Multiattribute Decision Making: Distractor or Source of Arousal?

Uploaded by

22124218Copyright:

Available Formats

The Effect of Flash Banners

on Multiattribute Decision

Making: Distractor or

Source of Arousal?

Rong-Fuh Day

Southern Taiwan University of Technology

Gary C.-W. Shyi

National Chung-Cheng University

Jyun-Cheng Wang

National Tsing Hua University

ABSTRACT

The role of peripheral flash advertisements in decision making as a

distractor or a source of arousal was examined. Participants were

asked to perform multiattribute decision making in a display envi-

ronment with or without banners of advertisement flashing occasion-

ally in the peripheral region of the display. The flash banners acceler-

ated the speed of decision making, although the participants rarely

made eye movements in response to the banners or fixated their eyes

on them. It was interesting to note that the participants’ pupil sizes

increased with the presence of flash banners. These findings suggest

that rather than distracting participants’ attention, flash banners

appear to elevate the general level of arousal of the participants,

which in turn led to making faster on-line decisions. © 2006 Wiley

Periodicals, Inc.

E-commerce has gradually emerged as an important platform for con-

ducting business in Taiwan as well as in other parts of the world. Com-

Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 23(5): 369–382 (May 2006)

Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com)

© 2006 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. DOI: 10.1002/mar.20117

369

pared to the traditional physical stores, on-line cyberstores, using mod-

ern technologies, create a different informational environment. One of the

most notable cyberstore features is the wide use of flashing banners to

present information. Interest in the effectiveness of flashing banners as

means of influence has been growing in recent years. Flash technology

has been used for various purposes. Here, the discussion is limited to

peripheral flash advertisement.

Choosing and purchasing a product are common tasks performed by

visitors to on-line stores. Basically, on-line purchasing behavior can be

characterized as a kind of consumer decision making and can be aptly

viewed and analyzed from the perspective of information processing.

Much consumer and marketing research has already addressed how a

specific process is constructed and executed in terms of individual char-

acteristics, decision, and context (Bettman, Luce, & Payne, 1998). How-

ever, the role that peripheral flash ads, so popular today, play in making

decisions is not yet fully understood. It is believed that a better under-

standing of the role of flash in decision making will provide better insight

on the design of Web sites and add to the knowledge of how situational

factors may affect on-line consumers’ purchase decisions.

Theoretically, attention is conceived as an important mediating factor

for explaining the interaction between the flash ad and the on-line task.

A brief review of the literature indicates that attention can play at least

two different roles in the decision-making process when flash ads are

involved. One possible role is that, because flash ads typically appear

along with the information a consumer would use for making his or her

decisions, their presence may act as a distractor, interrupting the ongo-

ing decision process (Egeth & Yantis, 1997; Kahneman, 1973; Norman &

Bobrow, 1975). Another possible role for peripheral flash ads has recently

been suggested by Dreze and Hussherr (2003), who reported that par-

ticipants in their study learned to avoid allocating attention to periph-

eral ads, and by Gao, Koufaris, and Ducoffe (2004), who found that ani-

mated ads could sometimes induce negative feelings, such as irritation.

In these latter cases flash ads may have elevated arousal in the viewer

rather than distracting the viewer’s attention. Although these implicit

assumptions regarding the role of flash ads coexist in the literature, lit-

tle has been done to examine these possible roles directly.

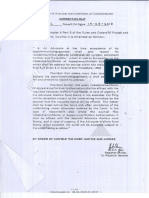

This study examines the effect of flash banners on the process of deci-

sion making (see Table 1). Of specific concern is the question of whether

flash banners are better characterized as a distractor or as a source of

arousal for on-line consumers. To answer this question, a laboratory

experiment was designed with the dual-task paradigm (Pashler, 1995;

Pashler, Johnston, & Ruthruff, 2001). In contrast to the viewpoint of the

motivation, opportunity, and ability model (MacInnis & Jaworski, 1989;

MacInnis, Moorman, & Jaworski, 1991), decision making was assumed

to be the primary task, and ad information processing the secondary

task. Furthermore, eye movements and pupil sizes were recorded on-

370 DAY, SHYI, AND WANG

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

Table 1. A Summary for the Roles of Flash Ads, Hypotheses, Predictions, and

Experimental Results.

Dependent Variable Hypothesis Result

Decision time (DT) Hypothesis: flash ads as a distractor

DT in no-flash-ads environment ⬍ DT in Not supported

flash-ads environment

Hypothesis: flash ads as an arousal source

DT in no-flash-ads environment ⬎ DT in Supported

flash-ads environment

Decision accuracy (AD) Hypothesis: flash ads as a distractor

AD in no-flash-ads environment ⬎ AD in Not supported

flash-ads environment

Hypothesis: flash ads as an arousal source

AD in no-flash-ads environment ⫽ AD in Supported

flash-ads environment

Level of arousal (LoA) Hypothesis: flash ads as an arousal source

AL in no-flash-ads environment ⬍ LoA in Supported

flash-ads environment

line while participants were making their decisions. With this approach,

direct observation of whether attention was allocated to the primary

task of decision-making or to the peripheral flash ads was possible.

Attention

Research on flash ad stems from two lines of investigation, namely, mar-

keting research of advertisement and visual search in the field of atten-

tion. In advertising research, researchers are mainly concerned with

whether or not flash would increase the recall of flash content or the

click rate (Cho, 2003; Li & Bukovac, 1999; Yoon, 2003; Zhang, 2000). In

attentional research on visual search, researchers have investigated

whether or not flash would increase or decrease the efficiency of infor-

mation search on the Web in terms of expended time and accuracy (Hong,

Thong, & Tam, 2004; Zhang, 2000). Although these two lines of research

clearly reflect different academic and practical interests, they both main-

tain the same theoretical assumption that attention plays an important

mediating role in information processing (Bettman et al., 1998; Kahne-

man, 1973; MacInnis & Jaworski, 1989; MacInnis et al., 1991).

Most researchers in the area of attention agree that attention can be

regarded as processing resources with limited supply when an individ-

ual is faced with multiple demands of concurrent mental activities (Kah-

neman, 1973; Luck & Vecera, 2002). Hence, issues regarding the allo-

cation and control of attentional resources are important. In general,

allocation and control of attention can be accomplished in two distinct

modes: voluntary and involuntary control (Kahneman, 1973). Voluntary

THE EFFECT OF FLASH BANNERS 371

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

attentional control, also termed top-down or goal-directed attention,

assumes that the allocation of attentional resources is dependent on

such endogenous factors as an individual’s goals or expectations (Egeth

& Yantis, 1997; Johnston & Dark, 1986). Involuntary attention control,

also termed bottom-up or stimulus-driven attention, assumes that the

allocation of attention is induced by the properties of an external event

without the individual’s deliberate intent, such as a sudden movement

in the periphery or a sudden flash or onset of light (Egeth & Yantis,

1997). Norman and Bobrow (1975) suggested that there was an impor-

tant relationship between attention allocation and task performance in

that task performance is a monotonic function of attentional resources

allocated to the mental activities required by the task. These views of

attention and their supporting empirical evidence provide a general

framework for analyzing and understanding the potential roles of atten-

tion in decision making.

Multiattribute Decision Making

A multiattribute decision in the marketing context is characterized by

a decision maker’s need to choose one brand out of a set of alternatives,

where each alternative is described by a common set of attributes. Because

this kind of decision is very common in everyday life, it has been widely

used and studied in the fields of behavioral decision making and con-

sumer behavior. One approach to studying multiattribute decision is

from the information processing perspective. According to this perspec-

tive, decision making is viewed as a kind of problem solving that, given

an initial problem state and goal, the decision maker transforms the

problem state step by step in the working memory until the goal state

is achieved (Holland, Holyoak, Nisbett, & Thagard, 1986; Newell & Simon,

1972; Payne, Bettman, & Johnson, 1993). The decision-making process

can, therefore, be subdivided into a set of elementary information

processes (EIPs), such as reading, comparing, etc. (Payne et al., 1993).

Based on the set of EIPs, a variety of the decision-making strategies can

be modeled, such as WAD, EBA, etc., and the processing effort for each

decision strategy can be estimated more precisely in terms of the num-

ber of EIPs. This approach allows ready comparisons among various deci-

sion-making strategies.

Peripheral Flash Ad as a Distractor

Flash ads are comprised of two parts: flash function and ad information.

Flash is characterized as temporal discontinuities in the physical prop-

erty of objects presented in a scene. Prior studies have suggested that

visual transients, that is, motion, changes in stimuli over time, and abrupt

onset (appearance) or offset (disappearance) of objects, are likely to cap-

ture attention, especially when they occur briefly. In addition, because

372 DAY, SHYI, AND WANG

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

most Web ads are distinguishable in some respect of their physical prop-

erties from the main content of a Web page, they tend to create discon-

tinuities in the spatial distribution of physical properties and act like

singletons in a visual scene. A larger number of studies in visual atten-

tion have repeatedly demonstrated that singletons can capture atten-

tion automatically without a deliberate intent or effort on the part of an

observer (Egeth & Yantis, 1997; Yantis & Egeth, 1999). Because a flash

ad has these two properties, it can presumably trigger involuntary or

automatic allocation of attention. It captures a customer’s attention and,

as a consequence, diverts away part of the consumer’s processing resources

from the target.

As stated earlier, the deployment of attention in a visual scene is largely

dependent upon two opposing factors, namely top-down versus bottom-up

attentional controls (Egeth & Yantis, 1997; Pashler et al., 2001). As Pash-

ler et al. (2001) put it, “Human behavior emerges from the interaction of

the goals that people have and the stimuli that impinge on them” (p. 630).

More realistically, the information environment on the Web nowadays is

so complex that intensive and dynamic interactions between the two

modes of controls are inevitable. On the one hand, when consumers enter

an on-line store with the goal of choosing one brand of product from a set

of alternatives, the deployment of attention is voluntary in the sense that

attention plays an active role of monitoring and fueling the operation of

EIPs in the working memory. On the other hand, during the primary task,

a decision maker’s attention is likely to be captured by the peripheral

flash ad, and then the limited processing resources would be diverted to

process the ad, the secondary task. Two negative effects on the primary

task are expected to occur after the secondary task is activated. First,

when the secondary task is operating, a decision maker is expected to for-

get some of the information needed for processing the primary task. Sec-

ond, when the secondary task is finished, the decision maker returns to

the primary task to complete the task. At this point, a recovery period is

needed to reprocess information that was forgotten. Based on the above

rationale, flash peripheral ad is expected to act as a distractor. Specifically,

according to the distractor hypothesis, it is proposed that in an informa-

tion environment with flash peripheral advertisement, a participant needs

more time to perform decision-making tasks than in an information envi-

ronment without peripheral flash. Furthermore, each time the decision

maker recovers the original state, he or she may have to redo some EIPs.

These additional operations may increase the likelihood of errors during

the decision process, meaning that flash peripheral advertisement may

negatively affect performance in terms of decision accuracy.

Peripheral Flash Ad as a Source of Arousal

Rather than viewing flash ads as distractors, results from several recent

empirical studies on Web ads suggest that peripheral flash ads could play

THE EFFECT OF FLASH BANNERS 373

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

a very different role. Some research suggests that flash ads are not effec-

tive enough to capture the on-line users’ attention. For instance, Dreze and

Hussherr (2003) recorded on-line users’ eye fixations on a portal Web site

and analyzed their scanning paths. They found that on-line users only

occasionally fixated the regions at which Web ads were located, suggest-

ing that on-line users may have learned to avoid diverting attention to Web

ads. Furthermore, Hong et al. (2004) argued that on-line users tend to

suppress the interference caused by flash ads through exerting additional

mental efforts on doing the primary task. These suggestions depart from

the distractor hypothesis in which it is thought that flash might activate

and capture attention involuntarily to peripheral ads and therefore inter-

rupt the primary task at hand. Similarly, animation ads seem to influence

a visitor’s affective states. For example, Gao et al. (2004) argued that,

given the overpowering effect of continuous animation on the human

peripheral vision, on-line animated ads have become a form of intrusive

presentation that, like scrolling messages at the edges of a television

screen, is a source of irritation or negative arousal to the on-line users.

Taken together, these findings lead us to consider an alternative hypoth-

esis, one in which peripheral flash ads act as a source of arousal, rather

than a distractor, to on-line decision makers. Specifically, according to the

arousal hypothesis, it is proposed that in an information environment

with flash peripheral advertisement, an individual has a higher level of

arousal than in an information environment without peripheral flash.

Prior research also has established a theoretical link between arousal

and attention. For example, in Kahneman’s (1973) capacity model of

attention, arousal will increase the total capacity of attention or sup-

ply of processing resource, and narrow the attention focus by concen-

trating on the dominant aspect of the situation at the expense of other

aspects, leading to improved performance. Furthermore, one recent

study has demonstrated that at the higher level of arousal, the inter-

nal clock appears to run faster, leading to a shortening of subjective

time, which in turn helps to push the participants to speed up their

cognitive responses (Wearden & Penton-Voak, 1995). Based on such

reasoning, if flash ads indeed arouse rather than distract participants,

it is predicted that participants’ performances in decision making will

actually be improved. In other words, according to the arousal hypoth-

esis, it is proposed that in an information environment with flash

peripheral advertisement, a participant will perform decision-making

tasks more efficiently in terms of decision time than in an information

environment without peripheral flash. Furthermore, because arousal

helps narrow the focus of attention, the decision-making task may be

protected to some extent from interruption caused by the peripheral ad.

Consequently, there would be a dramatic decrease in the likelihood

that elementary information processes and calculation errors would

be done in the recovery period. Therefore, it is proposed that there is

no difference in decision accuracy between the information environ-

ment with or without flash peripheral advertisement. The study inves-

374 DAY, SHYI, AND WANG

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

tigates which hypothesis better explains the role of peripheral flash

ads—as a distractor or as a source of arousal.

METHOD

Participants

A total of 30 college students were recruited as participants from the

Southern Taiwan University of Technology, Taiwan. Each participant

was paid a cash reward of NT$100 for their participation. In order to

encourage them to make decisions accurately, an additional incentive of

NT$80 was awarded based on decision accuracy.

Stimulus Materials and Apparatus

The information environment was manipulated by placing either flash

banners around the decision information or no extraneous information

at all. The information for the decision-making task was arranged and

displayed in the form of an alternative-attribute matrix, which has been

widely used in prior research on decision making (Payne et al., 1993).

As shown in Figure 1, the information matrix consisted of four alter-

natives, each with four attributes. The layout of the information envi-

ronment was displayed in the medium resolution mode of 800*600 pix-

els. In the no–flash-banner environment, only the decision information

Figure 1. Layout of the two information environments used in the experiment. The

top banner shown in the right panel is the peripheral flash advertisement. The central

portion of the both layouts is the decision information matrix about four skin-protec-

tion lotions. It describes four attributes, including SPF, Polished, Moisture, and Fresh-

ness. The values of each attribute are relative scores, ranging from 1 to 5. It is worth

noting that the original experimental layout was in Chinese. In this case, the EBA

decision tasks on the two decision information matrices are equivalent in terms of ele-

mentary information processes. The spatial distribution of eye fixations for the EBA

tasks in the two information environments is shown. As can be seen from the figure,

only a handful of eye fixations were laid on the peripheral banners.

THE EFFECT OF FLASH BANNERS 375

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

matrix was shown at the center of the screen, occupying an area of

600*400 pixels. In the flash-banner environment, flash banners with a

size of 468*60 pixels were placed both above and below the area of deci-

sion information. Five designers drew a total of 64 single-framed ban-

ners with their sizes meeting the standards outlined by the Interactive

Advertising Bureau for a full banner of 468*60 IMU. In order to avoid

the potential effect of color, all banners were drawn in grayscale. Dur-

ing the experiment proper, two banners were randomly selected from the

banner pool and displayed for 1.5 seconds above and below the decision

information matrix in an alternating manner. This continuous and tran-

sient placement of different banners in the peripheral regions created

a distinct impression of flash.

An EyeLink II eye-tracking system (SR Research, Canada) with a sam-

pling rate of 500 Hz was used to track and record the participants’ eye

movements (saccades and fixations) and their pupil sizes while the deci-

sion-making task was being performed. Prior research has suggested

that eye movement is directly related to the underlying cognitive process

(Just & Carpenter, 1976; Rayner, 1998), which is also known as the

eye–mind assumption. Just and Carpenter (1976), for example, suggested

that eyes often fixated on the external referents whose corresponding

internal representations are processed. Various research tracking eye

movements in the past has provided the evidence to support the eye–mind

assumption in that eye movement is a sufficient and valid reflection of

the decision process. It should also be noted that pupil size has been

regarded as a reliable and sensitive index for reflecting the level of arousal

and the capacity of momentary mental effort (Beatty & Lucero-Wagoner,

2000; Kahneman, 1973). That is, the level of arousal and the momentary

effort in information processing are positively related.

Task and Strategies

Prior to the actual experiment, participants were trained to use two

strategies, the weighted additive rule (WADD) and the elimination-by-

aspects method (EBA), to solve two choice problems in each information

environment. The operational definitions of the two decision strategies

followed faithfully those of Payne et al. (1993).

As described by Payne et al., the WADD choice strategy not only con-

siders the values of each alternative for all the relevant attributes, but

also takes into account all the relative weights of the attributes. With

WADD, the decision maker can derive an overall evaluation of each alter-

native by multiplying the weight with the value for each attribute, and

adding together those weighted values across all attributes. After deriv-

ing the weighted value for each alternative, the one with the highest

value will be selected. In contrast, the EBA choice strategy first deter-

mines the most important attribute and the cutoff value for that attrib-

ute is also retrieved. Then, all alternatives with values for that attribute

376 DAY, SHYI, AND WANG

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

below the cutoff are eliminated. This process is repeated until only one

alternative remains.

In order to keep each participant’s performance on the decision tasks

comparable with one another, equivalent tasks were created by randomly

swapping columns designating the four attributes or rows designating the

four alternatives in the matrix of decision information. For both the

WADD strategy and the EBA strategy, the exchange of the attribute

columns or alternative rows of a decision information matrix would make

the choice tasks performed on the decision matrix equivalent. In this

way, it was ensured that equivalent tasks performed in the various infor-

mation environments were equivalent in terms of level of difficulty.

Design and Procedure

Only one within-subject factor was manipulated in the experiment; namely,

the primary decision-making task was performed either with flash banners

presented in the periphery of the display screen, or without.

The participants were tested individually in the actual experiment,

which was divided into two sessions: the training session and the exper-

imental session. In the training session, a video was played for 10 min-

utes to instruct the participants about how to use WADD and EBA strate-

gies to solve a choice task. After watching the instructional video, the

participants decided whether to replay the video or to start practicing the

two learned strategies on the computer. During the practice, participants

were told to use both the WADD and the EBA strategy three times to solve

the problem of selecting a restaurant location. The decision information

matrix for practice also consisted of four alternatives, each with four

attributes, in the same manner as those that were later used in the exper-

imental session. Upon arriving at a decision, the participants received

immediate feedback regarding accuracy of their decisions.

During the experimental session, the experimenter first put the eye

tracker’s leather-padded headband on the participant’s head and cali-

brated the eye tracker. The calibration and a subsequent validation took

about 7 minutes to complete. Then, an experimental program designed

for the present study was launched and the participant was told to arrive

at a choice as quickly and accurately as possible, with the use of the deci-

sion strategies practiced earlier. Each participant was asked to perform

one WADD and one EBA decision task with the flash banners presented

in the peripheral region, and to perform one of each task in the no-flash

peripheral ad information environment. The order of performing the

tasks with or without peripheral flash banners was randomly deter-

mined for each participant. The matrix of decision information stayed

on the screen until a decision was made. The participant’s decision choice,

along with his or her eye movement and pupil size were recorded. The

time to reach a decision, its accuracy, as well as variations in pupil size,

were the main dependent variables for data analysis.

THE EFFECT OF FLASH BANNERS 377

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

RESULTS

Before any formal analysis, the eye movement data of each participant

were first inspected with a custom-made program to see whether or not

the data were valid (see Figure 1). Except for one participant whose data

was invalid, a total of 18,726 fixations from 29 participants were used for

further analysis, of which 12,036 fixations were recorded from the

no–flash-ad information environment, and 8,490 fixations were recorded

from the flash-ad information environment.

Basic Analysis of Banner Position and Decision Strategy

In the flash-ad information environment, the area of the top banner

received about 3.21% of the total fixations, whereas the area of the bot-

tom banner got only .41% of the total fixations. This result is consistent

with the prior finding that banners placed on top were more attractive

than those placed at the bottom (Wang & Day, in press).

With the use of an SPSS-based paired-samples t test, it was found

that the EBA decision task received significantly fewer fixations (M ⫽

103.87) than the WADD task (M ⫽ 203.01), t ⫽ 8.56, p <.001. Moreover,

participants spent significantly less time on the EBA task (M ⫽ 24618.82)

than on the WADD decision task (M ⫽ 54274.68), t ⫽ 9.83, p ⬍ .001.

These results were consistent with the previous findings reported in the

literature that the WADD strategy tended to require more cognitive

effort, hence more time, than the EBA strategy (Payne et al., 1993). How-

ever, there was no significant difference in response accuracy (percent cor-

rect) between the WADD decision strategy (M ⫽ 89.6%) and the EBA

strategy (M ⫽ 91.3%) (z ⫽ .14, p ⬎ .1). Judging from the mean accuracy

in each task, it seems obvious that the difficulty level of the decision

tasks did not exceed the participants’ mental capacity.

Analysis of Information Environment

To see how the difference in information environment may affect par-

ticipants’ performance on each task, the paired-sample t test was again

applied on the decision time for each task. The mean decision time for the

no–flash-ad environment (M ⫽ 43552.20) was significantly greater than

the mean decision time for the flash-ad environment (M ⫽ 35341.31), t

⫽ 2.831, p ⬍ .01. Analogously, the mean pupil size in the no–flash-ad

environment was significant smaller (M ⫽ 6165.90) than that in the

flash-ad environment (M ⫽ 6242.01), t ⫽ 3.471, p ⬍ .01. However, there

was no significant difference in response accuracy between the two infor-

mation environments (z ⫽ 0.14, p ⬎ .1). Taken together, these results

suggest that the presence of peripheral flash banners may have acted as

a source of (additional) arousal such that with their presence partici-

pants actually sped up their processes of decision making. Furthermore,

378 DAY, SHYI, AND WANG

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

as a consequence of a higher level of arousal, mobilizing more process-

ing resources may have helped compensate the possible deleterious effect

on response accuracy caused by the presence of flash banners.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This study aims to clarify the role that flash peripheral ads may act as

a distractor or as a source of arousal in the on-line process of making

decisions. It was found that, with the same level of decision accuracy,

participants actually reached decisions with less time and exhibited a

higher level of arousal for equivalent decision tasks in the information

environment with peripheral flash ads than without. Moreover, it was also

found that participants fixated directly on the peripheral flash banners

only occasionally, with an average of less than 4% of the time. These find-

ings provide support to the view that flash peripheral ads tend to be a

source of arousal rather than a distractor. According to Kahneman’s

(1973) capacity model, the presence of flash peripheral ad first aroused

the participant, which in turn may have motivated the participant to

increase the supply of processing resources. Concomitantly, the decision-

making tasks benefited from sharing the additional supply of mental

resources and resulted in improved performance.

One of the most interesting aspects in these findings is that although

participants fixated their eyes on the peripheral ads only sparingly, they

were unable to isolate themselves completely from the influence of the

peripheral ad. Such influence is consistent with the nature of visual sys-

tem in that peripheral vision is dominated by the retinal magnocellular

system, which is sensitive to motion or signals of transient change (e.g.,

flash) arising from objects located in the peripheral area of the visual

field (Palmer, 1999). Therefore, in this study, the flash can exert its influ-

ence on the participants through peripheral vision, perhaps even with-

out their conscious awareness.

These findings also extend the popular Yerkes-Dodson (Yerkes & Dod-

son, 1908) law of psychological motivation to the on-line decision sce-

nario. The main idea suggested by the Yerkes-Dodson law is that arousal

is an important mediator or intervening variable in many types of behav-

ior. According to the Yerkes-Dodson law, when arousal level is posited on

a continuum where one end entails a state of calm and the other entails

an extreme heightened state, the relationship between the arousal level

and the cognitive performance can be characterized as an inverted-U

shape. In the present study, the information environment without flash

banners may represent a situation in which the participant’s inner state

was at the calm end. Upon the sudden presence of flash banners, how-

ever, the participant’s inner state may be shifted to the more heightened

end. As a consequence of heightened arousal, the participant accelerated

his or her speed in reaching a decision. The findings not only contribute

THE EFFECT OF FLASH BANNERS 379

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

to identify the subtle effect on arousal by the presence of flash periph-

eral ad, but also empirically confirm the theoretical link between the

arousal and the cognitive activity, that is, on-line decision making.

Finally, the present study contributes to methods for directly meas-

uring the working of attention with the eye tracker. In doing so, a poten-

tial risk of a circular inference was avoided by the usage of the recall

test and task performance as a substitute for the mediating effect of

attention (MacInnis et al., 1991). Moreover, this study specifically

addresses the changes in pupil size. This affective index did, however,

shed light on subtle changes in the physiological states of the partici-

pant and thus provides an additional dimension to understanding the

effect of flash ad.

The findings have two significant implications. As prior research

noted, arousal may cause attention narrowing and speed up response so

that a decision is taken before all relevant information has been assim-

ilated (Kahneman, 1973; Payne et al., 1993). This suggests that in the

real Web environment in which individuals can freely decide their own

strategies, flash ads may push on-line customers to use more heuristic

or simpler strategies to quickly arrive at a choice, although this may

not represent an optimal solution. Second, the results empirically val-

idated the belief that ads on the tops of Web pages are more valuable

than those at the bottom.

Limitations and Future Research

When interpreting these results, the reader should be aware of certain

limitations. First, the task is more fit to the on-line purchase scenario

in which customers are ready to buy and have a clear goal in mind. Sec-

ond, in order to control the moderating effect of decision strategy, the

strategies to be used were provided as part of the experiment. This

design feature of the present study may not fully reflect the actual on-

line decision behavior of individuals, which has been characterized as

being constructive and opportunistic (Payne et al., 1993). Third, the

decision information layout is based on the tradition of behavioral deci-

sion making. It abstracts the actual purchase information environment

in order to exclude irrelevant confounding factors. In spite of the bene-

fits of this more abstract approach, future research can be executed in

a more realistic Web environment to investigate the effects of other fac-

tors. Finally, this research used a restricted flash that had only contin-

uously changing single-frame banners at a constant speed. Future

research can use different ways to display ad information, such as onset,

offset, movement, etc., and different frequencies such as quick versus

slow or constant or unexpected with the aid of up-to-date Web technol-

ogy. Such manipulations have been validated as beneficial in revealing

the role of peripheral vision and involuntary attention control (Yantis

& Jonides, 1990).

380 DAY, SHYI, AND WANG

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

REFERENCES

Beatty, J., & Lucero-Wagoner, B. (2000). The pupillary system. In J. T. Cacioppo,

L. G. Tassinary, & G. Berntson (Eds.), Handbook of psychophysiology (2nd

ed., pp. 142–162). New York: Cambridge University.

Bettman, J. R., Luce, M. F., & Payne, J. W. (1998). Constructive consumer choice

processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 187–217.

Cho, C. H. (2003). The effectiveness of banner advertisements: Involvement and

click-through. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 80, 623–645.

Dreze, X., & Hussherr, F. X. (2003). Internet advertising: Is anybody watching?

Journal of Interactive Marketing, 17, 8–23.

Egeth, H. E., & Yantis, S. (1997). Visual attention: Control, representation, and

time course. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 269–297.

Gao, Y., Koufaris, M., & Ducoffe, R. H. (2004). An experimental study of the effect

of promotional techniques in Web-based commerce. Journal of Electronic Com-

merce in Organization, 2, 1–20.

Holland, J. H., Holyoak, K. J., Nisbett, R. E., & Thagard, P. R. (1986). Induction:

Processes of inference, learning, and memory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hong, W., Thong, J. Y. L., & Tam, K. Y. (2004). Does animation attract on-line users’

attention? The effects of flash on information search performance and per-

ception. Information Systems Research, 15, 60–86.

Johnston, W. A., & Dark, V. J. (1986). Selective attention. Annual Review of Psy-

chology, 37, 43–75.

Just, M. A., & Carpenter, P. A. (1976). Eye fixations and cognitive processes.

Cognitive Psychology, 8, 441–480.

Kahneman, D. (1973). Attention and effort. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Li, H., & Bukovac, J. L. (1999). Cognitive impact of banner ad characteristics:

An experimental study. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 76,

341–353.

Luck, S., & Vecera, S. P. (2002). Attention. In H. Pashler & S. Yantis (Eds.),

Stevens’ handbook of experimental psychology (Vol. 1): Sensation and per-

ception (pp. 235–286). New York: Wiley.

MacInnis, D. J., & Jaworski, B. J. (1989). Information processing from adver-

tisements: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Marketing, 53, 1–23.

MacInnis, D. J., Moorman, C., & Jaworski, B. J. (1991). Enhancing and measur-

ing consumer’s motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand infor-

mation from ads. Journal of Marketing, 55, 32–53.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

Norman, D. A., & Bobrow, D. G. (1975). On data-limited and resource-limited

processes. Cognitive Psychology, 7, 44–64.

Palmer, S. (1999). Vision science: Photons to phenomenology. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Pashler, H. (1995). Attention and visual perception: Analyzing divided atten-

tion. In S. M. Kosslyn & D. N. Osherson (Eds.), An invitation to cognitive sci-

ence (Vol. 2): Visual cognition (2nd ed., pp. 71–100). Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Pashler, H., Johnston, J. C., & Ruthruff, E. (2001). Attention and performance.

Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 629–651.

THE EFFECT OF FLASH BANNERS 381

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1993). The adaptive decision maker.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rayner, K. (1998). Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20

years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 372–422.

Wang, J. C., & Day, R. F. (in press). The effects of attention inertia on adver-

tisements on the WWW. Computers in Human Behavior.

Wearden, J. H., & Penton-Voak, I. S. (1995). Feeling the heat: Body temperature

and the rate of subjective time, revisited. Quarterly Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Section B, 48, 129–141.

Yantis, S., & Egeth, H. E. (1999). On the distinction between visual salience and

stimulus-driven attentional capture. Journal of Experimental Psychology/Human

Perception & Performance, 25, 661–676.

Yantis, S., & Jonides, J. (1990). Abrupt visual onsets and selective attention:

Voluntary versus automatic allocation. Journal of Experimental Psychol-

ogy/Human Perception & Performance, 16, 121–134.

Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). Relation of strength of stimulus to rapid-

ity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18,

459–482.

Yoon, S. J. (2003). An experimental approach to understanding banner adverts’

effectiveness. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing,

11, 255–272.

Zhang, P. (2000). The effects of animation on information seeking performance

on the World Wide Web: Securing attention or interfering with primary tasks.

Journal of Association for Information Systems, 1, 1–28.

Correspondence regarding this article should be sent to: Jyun-Cheng Wang,

Institute of Technology Management, National Tsing Hua University, 101, Sec-

tion 2, Kuang Fuh Road, Hsinchu 30013, Taiwan (jcwang@mx.nthu.edu.tw).

382 DAY, SHYI, AND WANG

Psychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

You might also like

- Carl Jung and The Ancient ToltecDocument2 pagesCarl Jung and The Ancient Toltecinfo7679100% (1)

- Roth - BA - MB VvipDocument16 pagesRoth - BA - MB VvipWasim QuraishiNo ratings yet

- UNC Lit ReviewDocument4 pagesUNC Lit ReviewpravinsuryaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Neuroscience: Advances in Understanding Consumer PsychologyDocument6 pagesConsumer Neuroscience: Advances in Understanding Consumer PsychologySimonNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Research Work by Marketing StudentsDocument16 pagesConsumer Behaviour Research Work by Marketing Studentsyumna kamalNo ratings yet

- Linda E. Couwenberg, Maarten A.S. Boksem, Roeland C. Dietvorst, Loek Worm, Willem J.M.I. Verbeke, Ale SmidtsDocument12 pagesLinda E. Couwenberg, Maarten A.S. Boksem, Roeland C. Dietvorst, Loek Worm, Willem J.M.I. Verbeke, Ale SmidtsAltair CamargoNo ratings yet

- Self-Congruency As A Cue in Different AdvertisingDocument36 pagesSelf-Congruency As A Cue in Different Advertisingjesusjrincon4685No ratings yet

- Sample Ch08Document19 pagesSample Ch08Dobranis Razvan - IonutNo ratings yet

- "The Impact of Neuro Marketing On Consumer Buying Behavior": JETIR2401583Document10 pages"The Impact of Neuro Marketing On Consumer Buying Behavior": JETIR2401583nivedithadbNo ratings yet

- Computers in Human Behavior: Full Length ArticleDocument6 pagesComputers in Human Behavior: Full Length ArticleBlayel FelihtNo ratings yet

- Impact of Neuromarketing Applications On Consumers: Surabhi SinghDocument21 pagesImpact of Neuromarketing Applications On Consumers: Surabhi SinghEmilioCamargoNo ratings yet

- Acp 3080Document13 pagesAcp 3080sophiaw1912No ratings yet

- Impact of Neuromarketing Applications On CustumerDocument21 pagesImpact of Neuromarketing Applications On CustumerMailaNo ratings yet

- Wyllow HDocument25 pagesWyllow Hapi-511262792No ratings yet

- Explaining The Special Case of Incongruity in AdveDocument33 pagesExplaining The Special Case of Incongruity in Advequinnacai87No ratings yet

- Experiencing Interactive Advertising Beyond Rich Media - Impacts of Ad Type and Presence On Brand Effectiveness in 3D Gaming Immersive Virtual EnvironmentsDocument15 pagesExperiencing Interactive Advertising Beyond Rich Media - Impacts of Ad Type and Presence On Brand Effectiveness in 3D Gaming Immersive Virtual EnvironmentsSerban SergiuNo ratings yet

- Impact of Neuromarketing Applications On Consumers: September 2020Document21 pagesImpact of Neuromarketing Applications On Consumers: September 2020Roopalli ChadhaNo ratings yet

- Antonia Mantonakis@brocku CaDocument25 pagesAntonia Mantonakis@brocku CaKhánh Huyền ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Neuromarketing ESSAY Adriana Bianchi PDFDocument7 pagesNeuromarketing ESSAY Adriana Bianchi PDFAdriana BianchiNo ratings yet

- NueromarketingDocument6 pagesNueromarketingStanley CheruiyotNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument7 pagesContent ServerMaria Fernanda AlmanzaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Dual-Task Processing On Consumers' Responses To High-And Low-Imagery Radio AdvertisementsDocument14 pagesThe Effects of Dual-Task Processing On Consumers' Responses To High-And Low-Imagery Radio AdvertisementsSava BogdanNo ratings yet

- Cultural Sponsorships Affect The Positive PerceptionDocument12 pagesCultural Sponsorships Affect The Positive PerceptionAntonio IvičevićNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior Dissertation PDFDocument8 pagesConsumer Behavior Dissertation PDFHelpWritingAPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Predicting Advertising Success BeyondDocument40 pagesPredicting Advertising Success BeyondAom SakornNo ratings yet

- Mathur and Sangeeta Jauhari (2017) Neuro Marketing Has An Important Role To Play in UnderstandingDocument4 pagesMathur and Sangeeta Jauhari (2017) Neuro Marketing Has An Important Role To Play in UnderstandingDrRishikesh KumarNo ratings yet

- A Study of The Effect of Product Placement in Television Shows AnDocument28 pagesA Study of The Effect of Product Placement in Television Shows AnMohsin KhalidNo ratings yet

- tmpF1C8 TMPDocument6 pagestmpF1C8 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- How Playable Ads Influence Consumer Attitude: Exploring The Mediation Effects of Perceived Control and Freedom ThreatDocument15 pagesHow Playable Ads Influence Consumer Attitude: Exploring The Mediation Effects of Perceived Control and Freedom ThreatMinza JehangirNo ratings yet

- Reconsidering Recall and Emotion in AdvertisingDocument9 pagesReconsidering Recall and Emotion in AdvertisingAnna Tello BabianoNo ratings yet

- Exposé Media PsychologyDocument9 pagesExposé Media PsychologyAgustina ContrerasNo ratings yet

- 6 Plassman Etal IJA 2007Document25 pages6 Plassman Etal IJA 2007edNo ratings yet

- Artículo NeuromarketingDocument11 pagesArtículo NeuromarketingARANZA ROSALES ALARCONNo ratings yet

- Social Media TiesDocument10 pagesSocial Media Tiesmuneebantall555No ratings yet

- An İntroduction To Neuromarketing and Understanding The Consumer Brain: They Do Purchase, But Why ? An İnsight For Review and İmplicationsDocument8 pagesAn İntroduction To Neuromarketing and Understanding The Consumer Brain: They Do Purchase, But Why ? An İnsight For Review and İmplicationseduzier eduzierNo ratings yet

- m201612002 PDFDocument6 pagesm201612002 PDFFiona Liana PaeteNo ratings yet

- Neuromarketing: Towards A Better Understanding of Consumer BehaviorDocument17 pagesNeuromarketing: Towards A Better Understanding of Consumer Behavioryulissa paz rozalesNo ratings yet

- Measuring Web Advertising Effectivenessin ChinaDocument17 pagesMeasuring Web Advertising Effectivenessin ChinaVICTOR HUGO SALVATIERRA MANCHEGONo ratings yet

- Neuromarketing - The Hope and Hype of Neuroimaging in Business PDFDocument19 pagesNeuromarketing - The Hope and Hype of Neuroimaging in Business PDFGuilherme RochaNo ratings yet

- External Communication Ass 02Document11 pagesExternal Communication Ass 02nkuta pitmanNo ratings yet

- Serminar in Decision Management PHDDocument20 pagesSerminar in Decision Management PHDRAPHAELNo ratings yet

- Linkage Between Persuasion Principles and AdvertisingDocument6 pagesLinkage Between Persuasion Principles and AdvertisingDhanesswary SanthiramohanNo ratings yet

- Self-Monitoring and Consumer Psychology: Kenneth G. DebonoDocument25 pagesSelf-Monitoring and Consumer Psychology: Kenneth G. Debono....snsnnsnsnNo ratings yet

- Impact of Advertising Appeals On Purchase IntentioDocument11 pagesImpact of Advertising Appeals On Purchase IntentioSaswat Kumar DeyNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Psy 3616 PDFDocument14 pagesFinal Paper Psy 3616 PDFapi-573370612No ratings yet

- Determining The Effect of Advertising Media On ChildrenDocument8 pagesDetermining The Effect of Advertising Media On ChildrenronnieBNo ratings yet

- MillwardBrown POV NeuroscienceDocument4 pagesMillwardBrown POV NeuroscienceDatalicious Pty LtdNo ratings yet

- Research Xe AnDocument22 pagesResearch Xe AnXean RamosNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Advertising On Cypriot Consumer The Effects of Advertising On Cypriot Consumer BehaviorDocument42 pagesThe Effects of Advertising On Cypriot Consumer The Effects of Advertising On Cypriot Consumer BehaviorMario UrsuNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document3 pagesAssignment 2Giuseppe D. RohrNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal RevisedDocument7 pagesResearch Proposal Revisedapi-602703387No ratings yet

- Marketing Research ProjectDocument32 pagesMarketing Research Projectkotha SaitejaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Gender Differences in Information Processing: in Relation To Advertising Appeals OrderDocument6 pagesThe Effect of Gender Differences in Information Processing: in Relation To Advertising Appeals OrderSEP-PublisherNo ratings yet

- Juanitas - 2CASSESSMENT 3 (Exposure To Comprehension)Document2 pagesJuanitas - 2CASSESSMENT 3 (Exposure To Comprehension)President GirlNo ratings yet

- Poistioning ReviewDocument8 pagesPoistioning Reviewletter2lalNo ratings yet

- Around The Web With Cognitive Psychology - EditedDocument8 pagesAround The Web With Cognitive Psychology - EditedAthman MwajmaNo ratings yet

- Advertising Habits Influencing Consumer Buying Behavior 1Document10 pagesAdvertising Habits Influencing Consumer Buying Behavior 1RanielJohn GutierrezNo ratings yet

- How Advertising Works What Do We Really KnowDocument19 pagesHow Advertising Works What Do We Really KnowboboboNo ratings yet

- Neuromarketing: No Brain, No Gain!Document13 pagesNeuromarketing: No Brain, No Gain!Anonymous traMmHJtV100% (1)

- 10 Chapter 2Document55 pages10 Chapter 2Kezza FaithNo ratings yet

- Mit Neet Globalstateengineeringeducation2018 PDFDocument170 pagesMit Neet Globalstateengineeringeducation2018 PDFAljohn CamuniasNo ratings yet

- Unit 2Document30 pagesUnit 2Nguyễn ThiênNo ratings yet

- Best Practices For Oracle Database On WindowsDocument54 pagesBest Practices For Oracle Database On WindowsCatalin Enache100% (1)

- Simple Present Exercises Sc101m2Document2 pagesSimple Present Exercises Sc101m2Rodrigo MartinezNo ratings yet

- REEd New SYLLABUS - Fundamentals of TheoDocument6 pagesREEd New SYLLABUS - Fundamentals of TheoMarjorie Gantalao - ResullarNo ratings yet

- It16 17Document44 pagesIt16 17Srikant PotluriNo ratings yet

- Competency Based EducationDocument23 pagesCompetency Based EducationRicha AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Arsenio Ray Maddox: ObjectiveDocument3 pagesArsenio Ray Maddox: ObjectiveArsenio MaddoxNo ratings yet

- Question Bank Is Created As Backup VoluntaryDocument3 pagesQuestion Bank Is Created As Backup VoluntaryD Y Patil Institute of MCA and MBA100% (1)

- 21st Century Literature Budgeted LessonDocument5 pages21st Century Literature Budgeted Lessonalona rose jimeneaNo ratings yet

- Capability Vs CompetencyDocument2 pagesCapability Vs CompetencyAgentSkySkyNo ratings yet

- MUET SpeakingDocument4 pagesMUET SpeakingJewelle QiNo ratings yet

- Mixed Methods Research DesignDocument7 pagesMixed Methods Research DesignBayissa BekeleNo ratings yet

- A Nation Without Education Is Little More Than A Gathering ofDocument3 pagesA Nation Without Education Is Little More Than A Gathering ofĀLįįHaiderPanhwerNo ratings yet

- 3 Data Sampling, Collection and Testing PowerpointDocument14 pages3 Data Sampling, Collection and Testing PowerpointRyana Rose CristobalNo ratings yet

- Head of Spanish Job Description - Jan 23Document7 pagesHead of Spanish Job Description - Jan 23Carolina MorenoNo ratings yet

- DLP Sci8 W4-4Document5 pagesDLP Sci8 W4-4Vanessa Joy SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Downloaded On - 06-04-2018 21:20:07Document240 pagesDownloaded On - 06-04-2018 21:20:07Anshul BansalNo ratings yet

- Effects of Computer Among Children - Docx RealDocument43 pagesEffects of Computer Among Children - Docx RealKiniNo ratings yet

- Managing Medical Records in Specialist Medical CenDocument4 pagesManaging Medical Records in Specialist Medical CenNur Aziera Md ShahNo ratings yet

- IO Structure With Support QuestionsDocument4 pagesIO Structure With Support QuestionsM M100% (1)

- Van Den Braden 2016 TBLTDocument14 pagesVan Den Braden 2016 TBLTNgọc Điệp ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Advances in Operating SystemsDocument2 pagesAdvances in Operating SystemsRaghavendra PhaydeNo ratings yet

- Program Book For Short Term Internship (1) (5) .Docx 22-6-2023Document36 pagesProgram Book For Short Term Internship (1) (5) .Docx 22-6-2023VIJAYKUMAR GNo ratings yet

- HRM-2022 P S SanjanaDocument16 pagesHRM-2022 P S SanjanaSanjanaNo ratings yet

- Irritable Bowel SyndromeDocument13 pagesIrritable Bowel SyndromeMay Ann ValledorNo ratings yet

- BUSM 1139 Elizabeth Health: BUSM1139 - SUSINDRA - NICHOLASHUGO - S3417647 1Document10 pagesBUSM 1139 Elizabeth Health: BUSM1139 - SUSINDRA - NICHOLASHUGO - S3417647 1Nicholas HugoNo ratings yet

- Devasc Module 2Document17 pagesDevasc Module 2Youssef FatihiNo ratings yet

- Solaris 9 For DummiesDocument387 pagesSolaris 9 For DummiesKerim Basol100% (1)