Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clinical Pharmacy Roger Walker Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 5th Ed

Clinical Pharmacy Roger Walker Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 5th Ed

Uploaded by

stella.gillesania.chenCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Pharmacy Roger Walker Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 5th Ed

Clinical Pharmacy Roger Walker Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 5th Ed

Uploaded by

stella.gillesania.chenCopyright:

Available Formats

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

OBSTETRIC AND GYNAECOLOGICAL DISORDERS

Drugs in pregnancy and

lactation

P. Russell, L. Yates, E. Grant and P. Golightly

47

Nevertheless, it has been estimated that over 80% of expectant

Key points mothers take three or four drugs at some stage of pregnancy

(Headley et al., 2004) with a significant number of women

Drugs in pregnancy

taking medication at the time their pregnancy is detected.

Indications for drug use range from chronic illnesses such as

epilepsy and depression to those commonly associated with

pregnancy such as hypertension, urinary tract infections and

gastro-intestinal complaints.

Approximately 2–3% of all live births are associated with

a congenital anomaly. Although exogenous factors such as

drugs may account for only 1–5% of these (affecting <0.2% of

all live births), given that drug-associated malformations are

largely preventable, they remain an important consideration.

Drugs as teratogens

Drugs in lactation

A teratogen is defined as any agent that results in structural

or functional abnormalities in the fetus, or in the child after

birth, as a consequence of maternal exposure during pregnancy.

Examples of drugs that are known to be human teratogens are

shown in Box 47.1. The teratogenic mechanism for most drugs

remains unclear, but may be due to the direct effects of the drug

on the fetus and/or as a consequence of indirect physiological

changes in the mother or fetus. Perhaps the best known, and

most widely studied teratogen is thalodimide, a mild sedative

Drugs in pregnancy Box 47.1 Examples of drugs considered to be human

teratogens

The use of both prescription and over-the-counter drugs in

pregnancy presents a number of challenges to those asked to Androgens

provide advice to women either pre-conceptually or during

pregnancy. This is in part due to the fact that no two cases are

the same, and that each enquiry ideally requires an individual

risk assessment that takes into account what is known about

the drug and its effects on the developing fetus, as well as the

Ethanol

woman's personal medical and family history. It is now well

recognised that certain drugs, chemicals and other agents,

readily cross the placenta and may act as teratogens, resulting

in harm to the unborn child. Robust scientific human data on Phenytoin

the effects of many of these drugs, particularly newer prepa-

rations, are, however, frequently lacking.

There is now a greater appreciation of the risks of drug use

in pregnancy, and it is generally accepted that maternal phar-

macotherapy should be avoided or minimised where possible. 739

© 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

47

that was widely marketed as a remedy for pregnancy-related system, which can be damaged by exposure to certain drugs,

nausea and vomiting. In 1961, thalidomide was withdrawn from for example, ethanol, at any stage of pregnancy. The external

the UK market following numerous reports of severe anatom- genitalia also continue to form from the seventh week until

ical birth defects in infants of mothers who took the drug in term, and consequently, danazol, which has weak androgenic

early pregnancy. Whereas external congenital anomalies such properties, can cause virilisation of a female fetus if given in

as limb abnormalities, spina bifida and hydrocephalus may be any trimester after the eighth week of pregnancy when the

obvious at birth, some defects may take many years to manifest androgen receptors begin to form (Rosa, 1984).

clinically or be identified. Examples of delayed effects of terato- Further examples include the angiotensin-converting

gens are the behavioural and intellectual disorders associated enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, which if given in the second and

with in utero alcohol exposure and the development of clear-cell third trimesters can result in fetal renal dysfunction and subse-

vaginal cancer in young women following maternal intake of quent oligohydramnios, that is, reduced amniotic fluid volume

diethylstilboestrol, used first in the 1930s for the prevention of (Sedman et al., 1995). The non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

miscarriage and preterm delivery (Herbst et al., 1971). drugs (NSAIDs) are another important group of drugs that

may cause problems specifically in the third trimester. These

drugs inhibit prostaglandin synthesis in a dose-related fashion

Critical periods in human fetal development

and, when given late in pregnancy, may result in premature clo-

The human gestation period is approximately 40 weeks from the sure of the fetal ductus arteriosus and fetal renal impairment

first day of the last menstrual period (38 weeks' post-conception) (Koren et al., 2006). NSAIDs should therefore be avoided dur-

and is conventionally divided into the first, second and third ing the third trimester.

trimesters, each lasting 3 calendar months. Another method for

classifying the stage of pregnancy is according to the stage of

Principles of teratogenesis

fetal development. This is a more useful approach when assess-

ing the potential risks associated with drug use in pregnancy. In 1959, James Wilson, co-founder of The Teratology Society,

proposed several principles of teratogenesis that have since

been expanded and modified but remain fundamental in assess-

ing whether a drug or chemical exposure during pregnancy is

The first two weeks post-conception are regarded as the pre- likely to be associated with reproductive or developmental tox-

embryonic stage and describe the period up to implantation icity. A basic understanding of these factors is essential to both

of the fertilised ovum. Teratogenic exposure during the pre- the interpretation of preclinical (animal) reproductive toxicity

embryonic stage is thought to elicit an ‘all-or-nothing’ response, studies and to enable accurate risk assessment in clinical prac-

leading either to death of the embryo or complete recovery and tice. A subset of Wilson's principles are discussed as follows.

normal development of the fetus. Fetal malformations follow-

ing drug exposure during this period are therefore thought to

be unlikely, except where the half-life of the drug is sufficient to

extend exposure into the embryonic stage. A good example of The stage of pregnancy at which a drug exposure occurs is

the latter is isotretinoin and related vitamin A derivatives which key to determining the likelihood, severity or nature of any

have half-lives up to a week, and which when used systemically, adverse effect on the fetus. Risk both between and within tri-

for example, for the treatment of acne and psoriasis, are recog- mesters may be variable. For example, folic acid antagonists,

nised teratogens (Nulman et al., 1998). for example, trimethoprim, are associated with an increased

risk of neural tube defects if exposure occurs before neural

tube closure (third to fourth week post-conception), but not

after this period (Hernandez-Diaz et al., 2001). It has also

Organogenesis occurs predominantly during the embryonic been suggested that trimethoprim should be avoided after

stage and, with the exception of the central nervous system, 32 weeks' gestation in view of the theoretical risk of severe

eyes, teeth, external genitalia and ears, is complete by the end jaundice in the neonate as a result of bilirubin displacement

of the 10th week of pregnancy. Exposure to drugs during this from protein binding, although clinical evidence to support

critical period therefore represents the greatest risk of major this is lacking (Dunn, 1964). Unfortunately, the precise period

birth defects. For this reason, women are often advised to of teratogenic risk is known for very few substances. One drug

avoid or minimise all drug use in the first trimester whenever for which this period has been established is thalidomide,

possible. It is important to bear in mind however, that very where exposure between days 20 and 36 post-conception is

few drugs are in fact proven teratogens and that exposure in associated with a high risk of congenital malformation (Lenz,

the second and third trimesters may still result in fetal harm. 1988; Newman, 1986).

Drug dose

During the fetal stage, the fetus continues to develop, grow A threshold dose above which drug-induced malformations

and mature and, importantly, remains susceptible to some are more likely to occur has now been demonstrated for cer-

740 drug effects. This is especially true for the central nervous tain teratogenic compounds, although for most a ‘safe dose’

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

DRUGS IN PREGNANCY AND LACTATION 47

has not been conclusively determined. The likelihood of a Similarly, maternal treatment with systemic isotretinoin dur-

dose relationship underlies the recommendation to use the ing the first trimester results in fetal malformation in only

lowest effective dose in pregnancy. For this reason, more fre- 18–35% of the live born infants, with a further 30% of chil-

quent monitoring of drug levels may be recommended for cer- dren exhibiting developmental delay in the absence of physi-

tain drugs during pregnancy. cal deformity (Benke, 1984; Braun et al., 1984; Hill, 1984).

Pharmacological effect

Teratogenicity of a drug may be species dependent. Interest- Pharmacological effects on the fetus are by far the most com-

ingly, preclinical thalidomide studies in mice and rats did not mon drug effects during pregnancy, and the consequences

result in congenital malformation in the offspring (Breitkreutz are often minor and reversible compared to the idiosyn-

and Anderson, 2008; Miller et al., 2009; Vorhees et al., 2001). cratic effects that can lead to major irreversible anomalies.

Birth defects or other adverse reproductive outcomes observed Pharmacological effects are usually dose related and to some

in animal studies cannot therefore be simply extrapolated to extent predictable. Drugs may adversely affect the fetus via

the human situation. Further, the drug dose and route of effects on the maternal circulation or they may cross the pla-

administration used in early animal studies may not be com- centa and exert a direct pharmacological effect on the fetus.

parable to clinical use in humans. Equally, drugs are sometimes administered to pregnant

women in order to treat fetal disorders; for example, flecain-

ide has been used to resolve fetal tachycardia.

The neonate can also be adversely affected by maternal

Not all fetuses exposed to known teratogenic drugs show evi- drug therapy (see Table 47.1). It is generally only at birth that

dence of having been affected in utero. It remains undeter- signs of fetal distress are observed due to in utero drug expo-

mined as to whether this variable susceptibility to teratogenic sure or the effects of abrupt discontinuation of the maternal

drugs is a result of genetic differences in the exposed mothers, drug supply. The capacity of the neonate to eliminate drugs

the fetal genotype, modifying environmental factors or a com- is reduced, and this can result in significant accumulation of

bination of all three. Malformations are reported to occur in some drugs, leading to toxicity. Neonatal withdrawal effects

only 20–50% of infants born to mothers exposed to thalido- may require treatment.

mide during the period of greatest risk for embryopathy, that Idiosyncratic drug effects in the fetus and neonate are pos-

is, days 20–36 post-fertilisation (Lenz, 1966; Newman, 1985). sible but occur rarely compared with pharmacological effects.

Table 47.1 Examples of drugs with pharmacological effects on the fetus or neonate S 7

Drug Possible adverse pharmacological effect Notes

NSAID

regularly

741

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

47

Maternal pharmacokinetic changes

There are a number of maternal changes which occur during Albumin is the main plasma protein responsible for bind-

pregnancy and are summarised in Table 47.2. ing acidic drugs such as phenytoin and salicylates, whilst

1

-acid glycoprotein predominantly binds basic drugs, includ-

ing -blockers and opioid analgesics. As pregnancy pro-

gresses, the plasma volume increases at a greater rate than

Gastric and intestinal emptying time increases by 30–40% in the increase in albumin which results in hypoalbuminae-

the second and third trimesters (Pavek et al., 2009) and could mia. In addition, steroid and placental hormones occupy the

be important in delaying absorption and time to onset of protein-binding sites. This leads to an increase in the frac-

action for some drugs (Loebstein et al., 1997). There is also tion of unbound drug. Clinical effect is related to the concen-

a reduction in gastric acid secretion in the first and second tration of unbound drug, which usually remains unchanged

trimesters and an increase in mucus secretion. As a conse- even though the total (bound plus unbound) plasma con-

quence of the increase in gastric pH, the ionisation, and hence centration is decreased. Thus, a fall in the total plasma con-

absorption, of weak acids and bases can be affected. centration does not usually require an increase in dose. The

Cardiac output and respiratory volume increase during 1

-acid glycoprotein concentrations remain the same as those

pregnancy leading to hyperventilation and increased pulmo- in non-pregnancy.

nary blood perfusion. These changes cause higher pulmonary Phenytoin is bound to albumin and exhibits the effects

absorption of anaesthetics, bronchodilators, pollutants, cigarette described earlier, but the situation is further complicated by

smoke and other volatile drugs. increased hepatic metabolism that may necessitate a dose

increase. Consequently, therapy can only be reliably guided by

clinical assessment or measurement of unbound rather than

Distribution

total plasma concentration.

The volume of distribution of drugs may be altered because

of an increase of up to 50% in blood (plasma) volume and a

30% increase in cardiac output. Renal blood flow increases by

up to 50% at the end of the first trimester and uterine blood The metabolic activity of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes

flow increases and peaks at term (36–42 L/h). There is also a CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP 2A6 and CYP 2C9 and uridine

mean increase of 8 L in body water (60% to placenta, fetus 5 -diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) isoenzymes

and amniotic fluid and 40% to maternal tissues). As a conse- (UGT1a1, UGT1A4 and UGT2B7) is increased during

quence, there may be increased dosage requirements for some pregnancy. Drugs metabolised by these isoenzymes may

drugs to achieve the same therapeutic effect, provided these therefore require dose adjustment. This may decrease the

effects are not offset by other pharmacokinetic changes. Both amount of the drug available for transfer across the pla-

the total plasma and the free-drug concentrations of pheny- centa and thereby influence fetal exposure. In contrast, the

toin, carbamazepine and valproic acid decrease during preg- metabolic activity of CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 is decreased

nancy, but the free-drug fraction (ratio of free to total plasma during pregnancy and drugs metabolised by these isoen-

concentration) may increase (Pavek et al., 2009). zymes may need dose reduction to minimise toxicity (see

Table 47.3).

In general, the effects on individual drugs are inconsistent

Table 47.2 Summary of pharmacokinetic changes during and difficult to predict, but knowledge of the effect of preg-

pregnancy nancy on isoenzymes may inform decisions about possible

Absorption Change during pregnancy

monitoring and/or dose alterations.

Within the first few weeks of pregnancy, the glomerular filtration

rate (GFR) increases by approximately 50%. Consequently,

those drugs which are excreted primarily unchanged by the

Distribution kidneys, for example, lithium, digoxin and penicillin, show

enhanced elimination and lower steady-state concentrations.

The following drugs have shown pregnancy-induced increases

of 20–65% on their renal elimination (Anderson, 2005):

Metabolism

Excretion

742

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

DRUGS IN PREGNANCY AND LACTATION 47

Table 47.3 Summary of pregnancy-induced effects on hepatic metabolism of some drugs Anderson, 2005

Isoenzyme Drugs/probes Effect on clearance

CYP1A2

CYP2A6 ND

Phenytoin

Proguanil ND

a

CYP2D6 ND ND

Cortisola ND ND b

b

ND ND

ND, not detectable.

a

Dextromethorphan and cortisol used as probes of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 activity.

b

Extent variable depending on the drug studied.

Drug dosing in pregnancy

As a general principle, the dose of a drug given at any stage

of pregnancy should be as low as possible to minimise poten-

tial toxic effects to the fetus. Drug therapy that is considered

essential can be tapered to the lowest effective dose either

before conception (ideally) or at the time the pregnancy is

Fetal-placental transfer

diagnosed. Where drug exposure during the third trimester is

Most drugs diffuse easily across the placenta and thus predicted to have an adverse effect on the neonate postpar-

enter the fetal circulation to some extent. In general, tum, consideration may be given to slowly reducing the dose

the ratio fetal:maternal drug concentration is less than towards term to minimise the risks to the baby. Such decisions

1. Drugs differ in the extent to which they bind to fetal are, however, not always straightforward. Recommendations

and maternal proteins. For example, fetal and newborn to wean an expectant mother off antidepressants and anti-

plasma proteins appear to bind ampicillin and benzylpen- psychotics to reduce the likelihood of neonatal withdrawal syn-

icillin with less affinity and salicylates with greater affin- drome (characterised by jitteriness, altered muscle tone, poor

ity, than maternal proteins. Maternal albumin gradually feeding and irritability) and, in the case of the SSRIs, avoid the

decreases during pregnancy and fetal albumin concentra- possible increased risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension

tions increase, so different fetal: maternal albumin con- of the newborn (PPHN) are now being challenged. Not only

centrations occur at different stages of pregnancy. The are there insufficient data to conclusively demonstrate neonatal

degree of protein binding of any drug is an important benefit or an optimal time of weaning, but also the increased

determinant of its movement across the placenta. Drugs risk of psychiatric problems and relapse in the immediate post-

which are highly protein bound tend to achieve higher partum period needs to be taken into account.

maternal and lower fetal concentrations. Drugs with very Many physiological changes occur during pregnancy which

large molecular weights such as insulin and heparin have may affect the way the body handles drugs. Knowledge of

negligible transfer. Lipophilic, un-ionised drugs cross the these changes can allow some prediction of the impact on

placenta more easily than polar drugs, and weakly basic pharmacotherapy while remaining aware that there is variabil-

drugs may become ‘trapped’ in the fetal circulation due ity in the extent of these changes during the pregnancy, and

to the slightly lower pH compared with maternal plasma. high inter-individual variability. The need for changes in dos-

Some other factors such as enzymes or drug efflux trans- ages is influenced by whether the drug is excreted unchanged

porters in the placenta may facilitate or restrict the trans- by the kidneys or which metabolic isoenzymes are involved in

fer of a drug to the fetus. its elimination. Women taking drugs with enhanced clearance 743

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

47

and for which a good correlation between plasma levels and denominator of drug exposure is unknown, and an abnor-

therapeutic effect exist, should have their plasma concentra- mal outcome may be coincidental to the drug exposure.

tions closely monitored and dose adjusted to reduce the risk of More recently, prospective controlled trials have been util-

suboptimal therapy, for example, phenytoin, carbamazepine, ised where the pregnancy outcomes of a defined cohort of

lithium and digoxin. Similarly, highly protein-bound drugs women exposed to the drug are compared with outcomes of

may require free-drug concentration monitoring. However, a matched control group. Complete follow-up of each preg-

there is no clear guidance for adjusting doses during preg- nancy and post-natal monitoring is an essential feature of this

nancy, and for most drugs, the concentration of free drug, type of investigation.

and therefore the effect of that drug, is unchanged.

Pregnancy itself can cause a temporary worsening or improve-

Pre-conception advice

ment of some diseases and in that way influence drug dosages.

Drug use during the first trimester, in particular, the embry-

onic stage, carries the greatest risk of malformation as this is

Drug selection in pregnancy

when the fetal organs are being formed. Ideally, all unnecessary

Although there are few, if any, drugs for which safe use in drug therapy should be discontinued prior to conception.

pregnancy can be absolutely assured, only a handful of However, inadvertent drug exposure frequently occurs, as

drugs in current clinical use have been conclusively shown to approximately half of all pregnancies are unplanned. It is

be teratogenic. In general, drugs that have been used exten- thus critical to make careful drug choices when prescribing

sively in pregnant women without apparent problems are for women of reproductive potential.

recommended in preference to new drugs for which there is Women with chronic illnesses requiring drug treatment

less experience of use. For example, methyldopa is used rarely should be offered specialist counselling before conception,

to treat hypertension in the non-pregnant state but has histor- and the options explored to reduce or change drug therapy to

ically been preferred in pregnancy because of a long history a safer agent. Epilepsy is an example, in which, if continued

of safe use (Schaefer et al., 2007). However, older drugs may drug treatment is necessary, attempts are made to stabilise

be less effective in terms of controlling maternal illness and treatment with a single drug at the lowest effective dose. It is

are often associated with an increased side-effect risk profile. also important to note that many pregnant women become

In most cases, the decision as to whether to commence or less adherent to their drug therapy out of concern about pos-

continue with a medication in pregnancy will depend on the sible harm to their infant. In many cases, such as asthma,

risk–benefit analysis for that specific mother–infant pair. A inflammatory bowel disease, epilepsy, inadequate treatment

frequent error made by health professionals is to apply the of the underlying disease may be more detrimental to the

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy risk mother–fetus pair than the drugs used to treat the condition.

categories (A (no demonstrable risk), B, C, D and X (terato- It is thus essential that women of reproductive potential are

genic agents that are considered to be completely contrain- given clear and accurate information so that unrealistic fears

dicated in pregnancy) when considering whether or not to about the risks to their baby do not result in unnecessary

prescribe a drug in pregnancy. It is now widely accepted that pregnancy termination or disease relapse.

these categories are oversimplified and are of little practi- All women planning a pregnancy should be offered gen-

cal help in a clinical setting. The FDA has proposed that the eral advice to minimise the risk of congenital anomalies. This

existing categories be replaced with more detailed informa- includes avoidance of recreational drugs, ‘natural’ or herbal

tion sheets containing a summary of the fetal risk and the remedies, alcohol, smoking, vitamin A products, minimisation

additional maternal factors that need to be taken into consid- of caffeine consumption and beginning daily supplementation

eration. Importantly, the need for a detailed section discussing with at least 400 µcg of folic acid to reduce the risk of neu-

the available data including observed human versus animal ral tube defects. It is recommended that the daily dose of folic

data, the study design, dose exposure, and reported congen- acid be increased to around 4–5 mg daily in women who have

ital malformations and/or adverse events has been empha- epilepsy or who have had a previous child with a neural tube

sised (see http://www.fda.gov for up-to-date information). defect. Some infectious diseases may carry important fetal con-

It is worth noting that standard literature sources often sequences if contracted during pregnancy. For example, rubella

contain unhelpful information such as ‘do not use in preg- infection in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy is associated with

nancy unless the benefits outweigh the risks’. This is under- an increased risk of miscarriage and a syndrome comprising

standable from a medico-legal point of view but offers little in problems such as deafness, cardiac defects and mental retarda-

terms of risk assessment. The primary literature is frequently tion in more than 20% of pregnancies. Women who lack immu-

inadequate because ethical and legal restraints mean that ran- nity to rubella should be immunised prior to conception.

domised controlled trials are rarely undertaken in pregnant

women. Often, the only information that is available is con-

Post-conception advice

fined to retrospective studies, voluntary reporting schemes

and/or animal studies. The rate of anomalies in retrospective It is important to draw distinction between advice given to

studies and voluntary reporting databases may be erroneously women pre-conceptually and that provided to a pregnant

elevated due to preferential reporting of abnormal outcomes. woman who has already been exposed to a drug. In the

744 Individual case reports are also difficult to interpret as the former setting, it may be recommended that an alternative

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

DRUGS IN PREGNANCY AND LACTATION 47

preparation be considered or that a drug treatment be stopped (Horta et al., 2007), juvenile-onset diabetes (Horta et al.,

where clinically appropriate. This advice often hinges on the 2007) and atopic disease (Fewtrell, 2004). Adults who were

lack of definitive safety data and does not automatically breastfed as infants often have lower blood pressure and

translate to exposure to that drug in pregnancy being an indi- lower cholesterol levels (Horta et al., 2007). Maternal ben-

cation for discontinuing the drug, additional fetal monitoring efits include reduced risk of developing pre-menopausal

or termination of the pregnancy on the basis of the exposure. breast cancer and delayed resumption of menstrual cycle.

Any change to the woman's medication should be based on a Breastfeeding also strengthens the mother–infant bond.

careful and individual risk assessment and include a discus- There are few contraindications to breastfeeding, although

sion with the woman to provide her with accurate up-to-date maternal HIV infection in developed countries is a notable

evidence-based advice. In many such cases, the woman can be exception. The percentage of women exclusively breastfeed-

reassured that a normal baby is the most likely outcome, or ing their infants after 6 months is often less than 20% (Scott

where appropriate be offered additional prenatal investigation et al., 2006). Reasons for early discontinuation of breastfeed-

to screen for congenital malformation where the risk to fetus ing include return to work, concerns about inadequate lacta-

is considered to be significant. tion or safety of drug use.

Breastfeeding mothers frequently require treatment with pre-

scription medicines or may self-medicate with over-the-counter

Teratology Information Services and Pregnancy

preparations, nutritional supplements or herbal medicines. It is

Registries

important for health professionals to understand the principles

It is difficult to keep up to date with the published literature. of safe use of medications during lactation in order to provide

There is an increasing need for summary documents that include appropriate advice.

and critically appraise all available data, and which enable health There are two main goals to consider when formulating

care providers to have a balanced and informed discussion with advice for nursing mothers. These are to protect the infant from

patients regarding the risks and benefits of a certain therapy in maternal drug-related adverse effects and to allow, whenever

pregnancy. This is evidenced by the current debate surrounding possible, necessary maternal medication (Berlin et al., 2009).

the teratogenic potential of various antidepressants with con-

flicting opinion even amongst experts in the field.

Transfer of drugs into breast milk

Teratology information services (TISs) have been established

in several countries across the world and provide evidence- Most drugs pass into breast milk to some degree although trans-

based, up-to-date information and individual case-based risk fer is usually low. The drug ‘dose’ ingested by the infant via breast

assessments. In addition to reviewing published literature on milk only rarely causes adverse effects. Examples of adverse

drugs, teratology services also have access to specialist online effects observed in breastfed infants exposed to medication via

databases and discussion forums. A number routinely collect breast milk are given in Table 47.4, although not all of these are

pregnancy outcome data on the women about whom they receive proven to be directly due to the drug ingested via breast milk.

an enquiry, to enable surveillance for potential teratogens.

For some new drugs, pregnancy registries have been initi-

ated that record all reported drug exposures and follow up the Table 47.4 Adverse reactions reported in breastfed infants

outcome of the pregnancy. These registries are cumulative and Atenolol

work on the basis that specific anomalies would be identified

relatively quickly and that there will eventually be sufficient sta-

tistical power to detect the magnitude of any increased risk rel-

ative to the general population. These registries may be held by Codeine Death

a TIS, or by independent groups with an interest in a defined

area. The 2009 A/H1N1 influenza pandemic provided an exam-

ple of teratology services across the globe responding to the

urgent need for safety data by establishing registries on antivi-

ral and pandemic vaccine exposure during the pandemic.

Drugs in lactation

Breast milk is the best form of nutrition for young infants.

It provides all the energy and nutrients required for the first

6 months of life. The World Health Organization (WHO,

2001) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)

recommend exclusive breastfeeding for this period. Benefits

of breastfeeding include protection of the infant against

gastric, respiratory and urinary tract infections (Kramer Phenytoin

and Kakuma, 2002), and reduction in rates of obesity 745

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

47

Almost all drugs enter milk by passive diffusion of un-ionised, milk. The most important example is iodides which pass into

unbound drug through the lipid membranes of the alveolar cells milk in high concentrations (Hale, 2010).

of the breast, according to the pH partitioning theory. Several

factors influence the rate and extent of passive diffusion. These

Milk to plasma concentration ratio

include maternal plasma level, physiological differences between

plasma and milk and the physicochemical properties of the drug. Several methods have been proposed to determine the

Differences in composition between blood and milk determine amount of drug transferred to breast milk. The milk to

which physicochemical characteristics influence diffusion. plasma (M/P) ratio is often used as a measure of the extent

Milk differs from blood in that it has a lower pH (7.2 vs. 7.4), of drug transfer into breast milk. It is usually obtained from

less buffering capacity and higher fat content. The following case reports or small clinical studies and may be based on

drug parameters affect the extent of transfer into milk: paired concentrations or full area under the concentration–

time curve (AUC) analysis. M/P ratios that are based on a

pKa. This is a measure of the fraction of the drug that is

pair of milk and plasma samples collected simultaneously

ionised at a given pH, for example, physiological pH. Highly

may be inaccurate as they assume that the concentrations of

ionised drugs tend not to concentrate in milk. For basic

drug in milk and plasma are in parallel, which may not be the

drugs, for example, erythromycin, a greater fraction will be

case. It is better to collect multiple samples of plasma and

ionised at an acidic pH, so the milk compartment will tend

milk across a dosing interval or until the drug is cleared from

to ‘trap’ weak bases. In contrast, acidic drugs, for example,

both phases after a single dose, for determination of an M/P

penicillins, are more ionised at higher pH values and will be

ratio based on the respective AUCs (M/PAUC). Figure 47.1

‘trapped’ in the plasma compartment. Drugs with higher

demonstrates the markedly different estimates of M/P ratio

pKa values generally have higher milk/plasma ratios.

that can be obtained via both sampling methods. The true

Protein binding. Drugs that are highly bound to plasma

M/P ratio may vary significantly during the same episode of

proteins, for example, warfarin, are likely to be relatively

breastfeeding.

retained in maternal plasma because there is a lower

If human-derived M/P ratios are lacking for a particular

total protein content in the milk. High protein binding

drug, it may be possible to predict the extent of transfer using

essentially restricts the drug to the plasma compartment

known physicochemical properties, for example, pKa, and a

as only the free fraction of the drug crosses the biological

published predictive model (Atkinson and Begg, 1990; Begg

membrane. Milk concentrations of highly protein-bound

et al., 1992). M/P ratios obtained from animal studies should

drugs are usually low.

not be used for clinical decision making, as they may not cor-

Lipophilicity. The alveolar epithelium of the breast is a

relate well with human M/P ratios.

lipid barrier. Transfer of water-soluble drugs and ions is

Studies in humans demonstrate that most drugs have an

inhibited by this barrier. CNS active drugs usually have

M/P ratio less than 1.0, with the range of reported ratios being

the characteristics required to pass into milk.

from around 0.1 to 5.0. It is often thought that drugs with high

Molecular weight. Drugs with low molecular weights

M/P ratios (e.g. 5.0) are unsafe because the concentration in

(<200) readily pass into milk through small pores in the cell

milk exceeds that in plasma, while those with low ratios (<1.0)

walls of alveolar cells. Drugs with higher molecular weights

are believed to be safe. This is not always the case as the M/P

cross cell membranes by dissolving in the lipid layer which

ratio often fails to correlate with the ‘dose’ of drug the infant

may substantially reduce milk concentrations. Proteins such

as heparin or insulin with very large molecular weights of

> 6000 are virtually excluded from milk. a

75

The profile of a drug that passes minimally into milk would

therefore be an acidic drug that is highly protein bound and

has low to moderate lipophilicity, for example, most NSAIDs.

Concentration

50

In contrast, a weakly basic drug that has low plasma protein

binding and is relatively lipophilic will achieve higher concen- b

trations in the milk compartment, for example, sotalol. c

In the first few days of life, large gaps exist between the 25

alveolar cells. These permit enhanced passage of drugs into Milk

milk. By the end of the first week, these gaps close under the Plasma

influence of prolactin (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2011). There 0

0 6 12 18 24

is greater passage of drugs into colostrum (early milk) than in

Time (h)

mature milk as the former contains more protein and less fat.

There is also some variation in fat and protein content of milk Fig. 47.1

between the beginning and end of a feed, but these changes

have less influence on drug passage than the physicochemical

properties of the drug. MP

Another method by which a drug may enter milk is by a MP

746 pumping system whereby energy is used to effect transfer into

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

DRUGS IN PREGNANCY AND LACTATION 47

ingests via milk. The amount of drug transferred into milk infants, so estimation of the likely steady-state average plasma

is principally determined by the maternal plasma level. Thus, drug concentration will be very approximate. Weight-adjusted

even where the M/P ratio is high, if the maternal plasma level Clinf values, that is, L/h/kg, are often significantly less than

is low, drug transfer is still low. Therefore, the M/P ratio must adult values in the early stages of life (Table 47.5).

never be used as the sole measure of drug safety in breastfeed- Given the difficulty in estimating infant plasma drug con-

ing. However, it can be used to estimate the ‘dose’ ingested via centrations, the relative infant dose, for example, compared

milk, which is a better predictor of safety. with a therapeutic infant dose, is often used as a surrogate of

exposure. To give some basis for comparison, the likely infant

dose from milk can be compared with an infant therapeutic

Calculating the infant ‘dose’ ingested via milk

dose. This is reasonable for drugs such as paracetamol that

Infant plasma drug levels are the most accurate indicator of are usually administered to infants but is unsuitable for drugs

drug exposure, but these are seldom available. such as antidepressants that are not. In the absence of a clearly

When using quantitative data from milk analyses, the most defined range of infant doses, the weight-adjusted maternal

accurate estimation of the infant ‘dose’ is from studies in which dose expressed as a percentage (% dose) is widely used to indi-

the milk is collected over a complete dose interval at steady cate infant drug exposure.

state and the total dose is calculated (Fig. 47.2). Unfortunately,

these studies are seldom performed. Therefore, information Relative infant dose (RID)

must be obtained from less than ideal conditions.

Dose in infant via milk [ Dinf (mg / kg / day)]

If the M/P ratio is known from published studies, the likely 100

infant dose (Dinf) can be calculated as follows, with some Dose in mother [ Dmat (mg / kg / day)]

assumptions:

Dinf Cp mat M /P Vmilk For the great majority of drugs, this calculation yields infant

doses in the order of 0.1–5.0% of the weight-adjusted maternal

where Cpmat is the average maternal plasma concentration.

dose expressed as a percentage (% dose). It is generally thought

M/PAUC is used in preference to a ratio based on paired con-

that relative infant dose values of less than 10% of the mater-

centrations when available, but this is seldom the case. The

nal dose are probably safe. However, the inherent toxicity of the

volume of milk ingested (Vmilk) is not known but is generally

drug should be taken into account when using this figure.

assumed to be around 150 mL of milk per kilogram of body

To calculate the daily infant drug intake via milk, the

weight per day. The above equation simplifies if the actual

standard milk intake of 150 mL/kg/day is multiplied by the

milk concentration data are available:

concentration of the medication in milk:

Dinf C milk Vmilk Estimated daily infant intake = Drug concentration in milk

( cg/L) × 0.15/infant weight (kg)

The likely infant plasma drug concentration (Cpinf) can be

Some authors use the peak concentration in milk to indicate

calculated by:

the maximum infant intake.

Cpinf F Dinf / Clinf

where F is oral availability and Clinf is the infant clearance. Variability

Unfortunately, neither F nor Clinf is known accurately for To complicate matters further, there will be significant vari-

ability between and within individuals in the values used to

20 estimate infant exposure (i.e. Dinf, F, Clinf, where Dinf is itself a

function of the estimated parameters Cpmat, M/P, volume of

milk). Some of this variability will change over time due to

Cumulative infant dose

developing organ function in the maturing baby and part will

10

Table 47.5 Approximate drug clearance by age as percentage

of maternal value (Begg, 2000)

0

0 4 8 12 16 20 24

Time (h)

Fig. 47.2

at steady state. 747

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

47

be unexplained variability. In addition to this pharmacoki- The maternal drug regimen can affect infant risk. Single

netic variability, there will be variability in response of the doses or short courses seldom present problems, whereas

infant to any given concentration of the drug. It is fortunate chronic therapy can be problematic. Topical or inhalation

that most drugs seem to fall readily into safe (RID <10%) therapy usually results in much lower plasma drug levels and

based on expected exposure. However, care should be taken therefore lower passage into milk. Multiple maternal medica-

when using these values to assess drug safety in lactation, tions increase the risk to the infant.

when variability in the estimates of the parameters used may

impact on the accuracy of prediction of their safety. This is

especially true for those circumstances when initial estimates Reducing risk to the breastfed infant

of these parameters are less precise, for example, in neonates. A number of strategies may be adopted to reduce the risk of

Recently, attention has been focused on the possible role drug-related side effects in the breastfed infant. One technique

of pharmacogenetic factors in affecting the safety of breast- that has been recommended for reducing infant exposure is to

fed infants exposed to drugs via milk (Madadi et al., 2009). give the maternal dose immediately after the infant has been

Sedation (and one death) occurred in infants of mothers with fed with the aim of avoiding feeding at peak milk concen-

rare genotypes of cytochrome P450 2D6 leading to ultra-rapid trations. However, this is often impractical, especially where

metabolism of codeine to morphine. The incidence of these young infants are feeding frequently up to 2 hourly. In addi-

genotypes varies amongst different populations. The overall tion, accurate data on times of peak levels in milk are often

percentage of Western Europeans with the CYP2D6 ultra- unavailable, and it cannot be assumed that times of peak milk

rapid metaboliser phenotype is 5.4% (Ingelman-Sundberg, levels mirror those in plasma. This technique should be used

2005). Higher percentages have been reported in populations selectively, that is, where the drug has a short half-life and

from northeast Africa and the Middle East. where peak and trough levels are predictable, for example,

antibiotics, anaesthetics.

Assessing the risk to the infant Where a single dose of a drug known to be hazardous is

Many factors must be considered when assessing the risk of given to a breastfeeding mother, for example, a radiophar-

maternal drug therapy to the breastfeeding infant (Box 47.2). maceutical, it will usually be possible to resume breastfeeding

Inherent toxicity of the drug will be a main factor in deter- after a suitable washout period, calculated as five times the

mining infant safety. Thus, antineoplastic drugs, radionu- half-life. Where the half-life is very long, the washout period

clides and iodine containing compounds would be of concern. necessary to avoid hazardous exposure to the infant may

Multiple maternal therapy with drugs with similar side-effect exceed the period of sustainable lactation.

profiles, for example, psychotropic drugs or anticonvulsants is Breastfeeding mothers should be advised to avoid

likely to increase the risk to the infant. Oral bioavailability is self-medication. Where drug use is clearly indicated, the lowest

an indicator of the drug's ability to reach the systemic circula- effective dose should be used for the shortest possible time. Use

tion after oral administration. Drugs with a low oral bioavail- of topical therapy such as eye/nasal drops for hay fever would

ability are either poorly absorbed from the gastro-intestinal reduce drug exposure in comparison to oral antihistamines.

tract, broken down in the gut or undergo extensive ‘first pass’ The maternal regimen should be simplified wherever pos-

metabolism in the liver before entering plasma. sible. A review of therapy before delivery will help to reduce

The presence of active metabolites, for example, desmethyl- risks to the neonate. New drugs are best avoided if a therapeu-

diazepam, may prolong infant drug exposure and lead to drug tic equivalent is available for which data on safe use in lacta-

accumulation, especially where drug clearance is low such as tion exists. All infants exposed to drugs via breast milk should

in the neonatal period. Similarly, drugs with long half-lives, be monitored for any untoward effects. Measures to ensure

for example, fluoxetine, may be problematic at this time. Drug the safety of the breastfed infant are summarised in Box 47.3.

clearance by the infant does not reach adult values until 6–7 Some commonly used drugs thought to be safe to use in moth-

months (Table 47.5). A premature infant of 30 weeks' ges- ers of full-term healthy infants are listed in Table 47.6.

tational age has a drug clearance value of about 10% of

the maternal value. It is important to distinguish between

gestational age and time after delivery. A 2-week-old infant Special situations

born at 28 weeks will have a gestational age of 30 weeks.

Neonates and especially premature infants are at greater risk

Box 47.2 Factors affecting infant risk from maternal therapy of developing adverse effects after exposure to drugs via breast

milk. Gastric emptying time is significantly prolonged and,

in some cases, may alter absorption kinetics. Protein binding

is decreased and values for total body water are higher than

for adults. Renal function is limited because the kidney is

anatomically and functionally immature. The neonate's capac-

ity to conjugate drugs in the liver is often deficient. For example,

the half-life of oxazepam (which is subject to glucuronidation)

748 is three to four times longer in neonates than in adults.

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

DRUGS IN PREGNANCY AND LACTATION 47

Box 47.3 Measures to ensure the safety of the breastfed infant

Allergy

The theoretical possibility exists for an allergic reaction in an

infant exposed to a drug in breast milk. Even minimal expo-

sure to the drug could cause an allergic response. However,

in practice, such reactions are very rare and only if the infant

has already experienced an allergic reaction to a particular

drug should maternal use be discouraged or breastfeeding

avoided.

Accurate details relating to maternal use of recreational drugs

may be difficult to obtain. Usage may be chronic or sporadic.

The role of the health professional in ensuring the safety of the

breastfed infant is important, and the advice should be that

substances such as cannabis, LSD and cocaine should be

avoided whilst breastfeeding.

Significant amounts of alcohol pass into milk although

it is not normally harmful to the infant if the quantity and

Table 47.6 Examples of commonly used drugs thought to

duration of intake are limited. The occasional consumption

be safe for use in breastfeeding mothers of full-term healthy

infantsa of a small alcoholic beverage is acceptable if breastfeeding

is avoided for about 2 h after the drink. Chronic or heavy

Drug groups Individual drugs consumers of alcohol should not breastfeed. High intakes

of alcohol decrease milk let down and disrupt nursing until

maternal levels decrease. Heavy maternal use may cause infant

sedation, fluid retention and hormone imbalances in breast-

fed infants.

Nicotine has been suggested to decrease basal prolactin

production although effects may be variable. Ideally, moth-

Progestogens Insulin ers should be encouraged not to smoke whilst breastfeed-

ing. Nicotine and its metabolite, cotinine, are both present in

milk. Undertaking smoking cessation with a nicotine patch is

Loratadine a safer option than continued smoking. Whilst transdermal

Nystatin nicotine patches produce a sustained lower nicotine plasma

level, nicotine gums produce large variations in peak levels.

A 2 -3 h washout period is recommended before breastfeeding

a

This table is to be used as a guide only. Expert advice is required when after maternal use of a nicotine gum.

the maternal dose is high, if the infant is premature, has renal or hepatic Caffeine appears in breast milk rapidly after maternal

disease or G6PD deficiency. intake. Fussiness, jitteriness and poor sleep patterns have been

reported in infants of mothers with very high caffeine intakes

equivalent to about 10 or more cups of coffee daily. Preterm

and newborn infants metabolise caffeine very slowly and are

at increased risk of adverse effects.

Infants with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD)

deficiency are susceptible to adverse effects even when only

Drug effects on lactation

small amounts of certain drugs are present in milk. G6PD

is an enzyme present in erythrocytes that is responsible for Drugs that affect dopamine activity are the main cause of

maintaining the antioxidant compound glutathione in its effects on milk production, mainly mediated by effects on

active form. Deficiency of this enzyme makes the erythro- prolactin. Early postpartum use of oestrogens may reduce the

cyte more susceptible to oxidative stress, resulting in hae- volume of milk, but the effect is variable and depends on the

molysis. Only small amounts of drug are needed to cause dose and the individual response. Progestogen contraceptives

such a reaction. Breastfeeding should be avoided or a safer are preferred.

alternative chosen if the infant has a known or suspected Drugs may occasionally be used therapeutically for their

G6PD deficiency and the mother is taking drugs that have effect on lactation. Dopamine agonists such as cabergoline

been reported to cause oxidative stress (e.g. nitrofurantoin, decrease milk production, and this effect may be utilised, for

dapsone). example, after an infant death. Dopamine agonists should not 749

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

47

be used routinely for relief of the symptoms of postpartum

pain or engorgement which can be managed with simple anal- Case 47.2

gesics or breast support. Dopamine antagonists such as dom- A 30-year-old woman with epilepsy is currently taking valproic

peridone may be used in cases of inadequate lactation which acid 1500 mg daily. She wishes to conceive but is concerned

have not responded to first-line methods such as improved about the possibility of birth defects due to valproate exposure

technique or milk expression by hand or pump. in pregnancy. Her seizures have been difficult to control with

Other drugs may affect lactation as an unwanted side effect, alternative anticonvulsants.

for example, diuretics. When these are used on a long-term

basis, infant weight gain should be monitored. Questions

Case studies

Answers

Case 47.1

A woman is 6 weeks' pregnant and has been diagnosed with

depression that warrants pharmacological intervention. She

wishes to recommence venlafaxine, which has been helpful in the

past. She is also anxious that the ethanol she consumed around

the time of conception may have harmed her baby.

Questions

Answers

Case 47.3

A 2-day-old full-term infant has excessive shrill crying, is jittery

and is feeding poorly. The medical team cannot find any cause

for these effects. The mother is worried that they may be due

to paroxetine exposure via breast milk and wonders whether

St John's wort would be a safer alternative. She has taken

paroxetine 20 mg daily throughout pregnancy, and this has been

continued after delivery.

You note from a specialist textbook that the likely infant

exposure is about 2% of the weight-adjusted maternal dose.

Questions

750

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

DRUGS IN PREGNANCY AND LACTATION 47

Answers

in utero

Case 47.5

A mother who wishes to give up smoking seeks advice on the

safety of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) whilst breastfeeding.

She is currently in the latter stages of pregnancy but does not

wish to use these products until after delivery and has not been

successful in significantly reducing her smoking without aids.

Questions

Answers

used.

Case 47.4

A breastfeeding mother returned to see her midwife 4 weeks

after delivery of a full-term healthy infant. She is complaining of

bilateral nipple pain during and after breastfeeding, a problem

that was constant for the past 4 days. She was advised to

use miconazole cream 2% to the nipples after each feed. This

provided initial relief but symptoms returned after a few days.

She was given a course of fluconazole 200 mg daily for 14 days

for a presumed candidal infection but expressed concern that the

medication might affect the infant.

Questions

Answers

Acknowledgements

The contribution of Stephen B. Duffull, Sharon J. Gardiner and

David K. Woods to previous versions of this chapter which appeared

in earlier editions is gratefully acknowledged. 751

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

lOMoARcPSD|34638345

47

References

Anderson, G., 2005. Pregnancy-induced changes in pharmacokinetics: a Art No. CD003517 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003517. Available at

mechanistic-based approach. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 44, 989–1008. http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab003517.html.

Atkinson, H.C., Begg, J., 1990. Prediction of drug distribution Lawrence, R.A., Lawrence, R.M., 2011. Breastfeeding. A Guide for the

into human milk from physicochemical characteristics. Clin. Medical Profession, seventh ed. Elsevier, Philadelphia.

Pharmacokinet. 18, 151–167. Lenz, W., 1966. Malformations caused by drugs in pregnancy. Am. J.

Begg, E.J., 2000. Clinical Pharmacology Essentials. The Principles Dis. Child 112, 99–106.

Behind the Prescribing Process. Adis International, Auckland. Lenz, W., 1988. A short history of thalidomide embryopathy. Teratology

Begg, E.J., Atkinson, E.J., Duffull, S.B., 1992. Prospective evaluation of 38, 203–215.

a model for the prediction of milk:plasma drug concentrations from Loebstein, R., Lalkin, A., Koren, G., 1997. Pharmacokinetic changes

physicochemical characteristics. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 33, 501–505. during pregnancy and their clinical relevance. Clin. Pharmacokinet.

Benke, P.J., 1984. The isotretinoin teratogen syndrome. J. Am. Med. 33, 328–343.

Assoc. 251, 3267–3269. Madadi, P., Ross, C.J., Hayden, M.R., et al., 2009. Pharmacogenetics

Berlin, C.M., Paul, I.M., Vesell, E.S., 2009. Safety issues of maternal of neonatal opioid toxicity following maternal use of codeine

drug therapy during breastfeeding. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 85, 20–22. during breastfeeding: a case control study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.

Braun, J.T., Franciosi, R.A., Mastri, A.R., et al., 1984. Isotretinoin 85, 31–35.

dysmorphic syndrome. Lancet 1, 506–507. Miller, M.T., Ventura, L., Stromland, K., 2009. Thalidomide and

Breitkreutz, I., Anderson, K.C., 2008. Thalidomide in multiple misoprostol: ophthalmologic manifestations and associations both

myeloma: clinical trials and aspects of drug metabolism and toxicity. expected and unexpected. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol.

Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 4, 973–985. Teratol. 85, 667–676.

Dunn, P.M., 1964. The possible relationship between the maternal Newman, C.G., 1985. Teratogen update: clinical aspects of

administration of sulphamethoxypyridazine and hyperbilirubinaemia thalidomide embryopathy: a continuing preoccupation. Teratology

in the newborn. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Commonw. 71, 128–131. 32, 133–144.

Fewtrell, M.S., 2004. The long term benefits of having been breastfed. Newman, C.G., 1986. The thalidomide syndrome: risks of exposure and

Curr. Paediatr. 14, 97–103. spectrum of malformations. Clin. Perinatol. 13, 555–573.

Hale, T.W., 2010. Medications and Mothers' Milk, fourteenth ed. Hale Nulman, I., Berkovitch, M., Klein, J., et al., 1998. Steady-state

Publishing, Amarillo. pharmacokinetics of isotretinoin and its 4-oxo metabolite:

Headley, J., Northstone, K., Simmons, H., et al., 2004. Medication use implications for fetal safety. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 38, 926–930.

during pregnancy: data from the Avon longitudinal study of parents Pavek, P., Ceckova, M., Staud, F., 2009. Variation of drug kinetics in

and children. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 60, 355–361. pregnancy. Curr. Drug Metab. 10, 520–529.

Herbst, A.L., Ulfelder, H., Poskanzer, D.C., 1971. Adenocarcinoma of Rosa, F.W., 1984. Virilization of the female fetus with maternal danazol

the vagina. Association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor exposure. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 149, 99–100.

appearance in young women. N. Engl. J. Med. 15, 878–881. Schaefer, C., Peters, P., Miller, R.K. (Eds.), 2007. Drugs During

Hernandez-Diaz, S., Werler, M.M., Walker, A.M., et al., 2001. Neural Pregnancy and Lactation: Treatment Options and Risk Assessment,

tube defects in relation to use of folic acid antagonists during second ed. Academic Press, Oxford.

pregnancy. Am. J. Epidemiol. 153, 961–968. Scott, J.A., Binns, C.W., Oddy, W.H., et al., 2006. Predictors of breastfeeding

Hill, R.M., 1984. Isotretinoin teratogenicity. Lancet 1, 1465. duration: evidence from a cohort study. Pediatrics 117, e646–e655.

Horta, B.L., Bahl, R., Martines, J.C., et al., 2007. Evidence on the Long- Sedman, A.B., Kershaw, D.B., Bunchman, T.E., 1995. Recognition and

Term Effects of Breastfeeding. WHO, Geneva. management of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor fetopathy.

Ingelman-Sundberg, M., 2005. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome Pediatr. Nephrol. 9, 382–385.

P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and Vorhees, C.V., Weisenburger, W.P., Minck, D.R., 2001. Neurobehavioral

functional diversity. Pharmacogenomics J. 5, 6–13. teratogenic effects of thalidomide in rats. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 23,

Koren, G., Florescu, A., Costei, A.M., et al., 2006. Non-steroidal anti- 255–264.

inflammatory drugs during third trimester and the risk of premature closure World Health Organization 2001 54th World Health Assembly, 2001.

of the ductus arteriosus: a meta-analysis. Ann. Pharmacother. 40, 824–829. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. The Optimal

Kramer, M.S., Kakuma, R., 2002. Optimal duration of exclusive Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding. WHO, Geneva. Available at

breastfeeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . Issue 1 http://apps.who.int/gb/archive/pdf_files/WHA54/ea54id4.pdf.

Further reading

Department of Health 2002 Infant feeding, 2000. Lee, A., 2006. Adverse Drug Reactions, second ed. Pharmaceutical

A Summary Report. DH, London. Available at http://www Press, London.

.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/ Schaefer, C., Peters, P.W.J., Miller, R.K. (Eds.) 2007. Drugs During

PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4008114. Pregnancy and Lactation. second ed. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Department of Health, 2003. Infant Feeding Recommendation. DH, Tomson, G., Sundwall, A., Lunell, N.O., et al., 1979. Transplacental

London. Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/ passage and kinetics in the mother and newborn of oxazepam given

dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4096999.pdf. during labour. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 25, 74–81.

Hale, T.W., Ilett, K., 2002. Drug Therapy and Breastfeeding: From

Theory to Clinical Practice. Parthenon Publishing, New York.

Useful websites

UK Teratology Information Service (UKTIS): OTIS (American Organisation of Teratology Information Services):

www.uktis.org www.otispregnancy.org

TOXBASE: Motherisk (Canadian Teratology information service):

www.toxbase.org www.motherisk.org.

752 European Network of Teratology Information Services:

http://www.entis-org.com

Downloaded by Stella Chen (stella.gillesania.chen@gmail.com)

You might also like

- The Dictionary of Fashion HistoryDocument567 pagesThe Dictionary of Fashion Historytarnawt100% (6)

- TeratologyDocument34 pagesTeratologyธิติวุฒิ แสงคล้อย100% (1)

- Practical Research 1 Quarter 1 - Module 20: Literature Review On SpotlightDocument9 pagesPractical Research 1 Quarter 1 - Module 20: Literature Review On SpotlightMark Allen Labasan100% (1)

- Deliverance QuestionnaireDocument9 pagesDeliverance Questionnaireyoutube_archangel100% (3)

- 2019-2020 Annual Calendar For School Counselors ArtifactsDocument9 pages2019-2020 Annual Calendar For School Counselors Artifactsapi-292958567No ratings yet

- Sample Deed of Sale House and LotDocument3 pagesSample Deed of Sale House and LotJess Villa100% (1)

- Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics by Cate Whittlesea and Karen HodsonDocument15 pagesClinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics by Cate Whittlesea and Karen Hodsonstella.gillesania.chenNo ratings yet

- Prescribing in PregnancyDocument2 pagesPrescribing in Pregnancymedical studentNo ratings yet

- Evolving Knowledge in Framing of Teratogenic Activity Towards Risk PerceptionDocument13 pagesEvolving Knowledge in Framing of Teratogenic Activity Towards Risk Perceptionsandy candyNo ratings yet

- Teratogenicity and Teratogenic Factors: AbbreviationsDocument5 pagesTeratogenicity and Teratogenic Factors: AbbreviationsItzel HernadezNo ratings yet

- Teratology & Drugs: BY DR C Sunithya Asst Prof Obs and GynaeDocument70 pagesTeratology & Drugs: BY DR C Sunithya Asst Prof Obs and GynaeMs BadooNo ratings yet

- (OBa TeratogensDocument15 pages(OBa TeratogensClyde Yuchengco Cu-unjiengNo ratings yet

- 4 - Drugs Used in Pregnancy and LactationDocument26 pages4 - Drugs Used in Pregnancy and Lactationtf.almutairi88No ratings yet

- Pharmacology of Pregnancy - PPT - Dr. Maulana Antian Empitu (Airlangga Medical Faculty)Document51 pagesPharmacology of Pregnancy - PPT - Dr. Maulana Antian Empitu (Airlangga Medical Faculty)rizkyyunitaa15100% (2)

- Jurnal KehamilanDocument13 pagesJurnal KehamilanNuraini Putri UtamiNo ratings yet

- ObstetricsA - Teratology, Teratogens, and Fetotoxic Agents - Dr. Marinas (Lea Pacis) PDFDocument15 pagesObstetricsA - Teratology, Teratogens, and Fetotoxic Agents - Dr. Marinas (Lea Pacis) PDFPamela CastilloNo ratings yet

- Teratogenicity and Its Risk FactorsDocument14 pagesTeratogenicity and Its Risk Factorssandy candyNo ratings yet

- Drugs During Pregnancy MyDocument29 pagesDrugs During Pregnancy Mysaadkadir450No ratings yet

- Drug Teratogens PDFDocument26 pagesDrug Teratogens PDFgibreilNo ratings yet

- Sato 2012Document6 pagesSato 2012triNo ratings yet

- Principles of Human Teratology: Drug, Chemical, and Infectious ExposureDocument7 pagesPrinciples of Human Teratology: Drug, Chemical, and Infectious ExposurenanaNo ratings yet

- Teratogenic Effect of Different Drugs at Different Stages in PregnancyDocument4 pagesTeratogenic Effect of Different Drugs at Different Stages in PregnancyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Over-the-Counter Medications in PregnancyDocument8 pagesOver-the-Counter Medications in PregnancyAlloiBialbaNo ratings yet

- Drug in PregnancyDocument5 pagesDrug in PregnancyNesru Ahmed AkkichuNo ratings yet

- PSB 578 PDFDocument4 pagesPSB 578 PDFDrAnisha PatelNo ratings yet

- Drugs in Pregnancy and LactationDocument6 pagesDrugs in Pregnancy and LactationRidwan FajiriNo ratings yet

- Lijekovi U TrudnoćiDocument5 pagesLijekovi U TrudnoćiEsad MedarNo ratings yet

- Amer Peds Recomm Re Psy Drugs and PregnancyDocument10 pagesAmer Peds Recomm Re Psy Drugs and Pregnancyscribd4kmhNo ratings yet

- Effect of Maternal Substance Abuse On The Fetus, Neonate, and ChildDocument12 pagesEffect of Maternal Substance Abuse On The Fetus, Neonate, and ChildAndres RamirezNo ratings yet

- Teratogenic Mechanisms of Medical DrugsDocument17 pagesTeratogenic Mechanisms of Medical DrugsKarol Valeria Garcia GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Drug in PregnancyDocument49 pagesDrug in PregnancyGarry B GunawanNo ratings yet

- Teratogens and Teratogenesis: General Principles of Clinical TeratologyDocument6 pagesTeratogens and Teratogenesis: General Principles of Clinical TeratologyKenny KayNo ratings yet

- 6811-Article Text-24511-1-10-20110110Document3 pages6811-Article Text-24511-1-10-20110110Mohammed shamiul ShahidNo ratings yet

- Teratogen: Student's Name Institution Course Title Instructor's Name DateDocument10 pagesTeratogen: Student's Name Institution Course Title Instructor's Name DateJudith ChebetNo ratings yet

- Dr. Vikas S. Sharma MD PharmacologyDocument67 pagesDr. Vikas S. Sharma MD Pharmacologyrevathidadam55555No ratings yet

- Dr. Vikas S. Sharma MD PharmacologyDocument67 pagesDr. Vikas S. Sharma MD Pharmacologyrevathidadam55555No ratings yet

- Teratogenic Mechanisms of MedicalDocument17 pagesTeratogenic Mechanisms of MedicalLeandro V. L.No ratings yet

- 02 Pharmacotherapy in Pregnancy and LactationDocument10 pages02 Pharmacotherapy in Pregnancy and LactationAlejandra RequesensNo ratings yet

- Taking Medicines in Pregnancy: What’s Safe and What’s Not - What The Experts SayFrom EverandTaking Medicines in Pregnancy: What’s Safe and What’s Not - What The Experts SayNo ratings yet

- The Role of Xenobiotic-Metabolizing Enzymes in The PlacentaDocument18 pagesThe Role of Xenobiotic-Metabolizing Enzymes in The Placentavirginia.mirandaNo ratings yet

- Hum. Reprod. Update 2010 Van Gelder 378 94Document17 pagesHum. Reprod. Update 2010 Van Gelder 378 94Leon L GayaNo ratings yet

- Pharma Reviewer-1Document9 pagesPharma Reviewer-1pinpindalgoNo ratings yet

- PIIS0016508506008651Document29 pagesPIIS0016508506008651Ongoongoseven b. e. bNo ratings yet

- Drugs Used in Pregnancy and LactationDocument13 pagesDrugs Used in Pregnancy and LactationFarina FaraziNo ratings yet

- F. Etwel Et Al 2014Document8 pagesF. Etwel Et Al 2014reclinpharmaNo ratings yet

- Some Issues To Consider While Prescribing Medications For : Pregnant and Lactating PatientsDocument25 pagesSome Issues To Consider While Prescribing Medications For : Pregnant and Lactating PatientsKishor Bajgain100% (1)

- Article Elsevier Contraception ThymorégulateursDocument5 pagesArticle Elsevier Contraception Thymorégulateursouazzani youssefNo ratings yet

- Appendix - Drug Use During PregnancyDocument6 pagesAppendix - Drug Use During PregnancySankar KuttiNo ratings yet

- American Academy of Pediatrics: ABBREVIATION. FDA, Food and Drug AdministrationDocument8 pagesAmerican Academy of Pediatrics: ABBREVIATION. FDA, Food and Drug AdministrationFadjar PoernomoNo ratings yet

- OBSTETRICS - 1.07 Teratology (Dr. Hidalgo)Document8 pagesOBSTETRICS - 1.07 Teratology (Dr. Hidalgo)Sofi CharuNo ratings yet

- General Pharmacology: By: Alemseged W, 2021Document61 pagesGeneral Pharmacology: By: Alemseged W, 2021abdi debele bedaneNo ratings yet

- Csdmard in Rheumatoid Arthritis During Pregnancy and Lactation: A ReviewDocument10 pagesCsdmard in Rheumatoid Arthritis During Pregnancy and Lactation: A Reviewyuliana160793No ratings yet

- Amphetamines, The Pregnant Woman and Her Children: A Review: State-Of-The-ArtDocument11 pagesAmphetamines, The Pregnant Woman and Her Children: A Review: State-Of-The-ArtAndreas NatanNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy of The Dental Patient During Pregnancy and LactationDocument6 pagesPharmacotherapy of The Dental Patient During Pregnancy and Lactationfarmasi RSUD joharbaruNo ratings yet

- TeratologyDocument4 pagesTeratologyxiejie22590No ratings yet

- Drugs in Pregnancy 2020Document44 pagesDrugs in Pregnancy 2020kristal eliasNo ratings yet

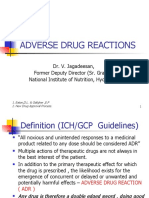

- Adverse Drug Reactions: Dr. V. Jagadeesan, Former Deputy Director (Sr. Grade), National Institute of Nutrition, HyderabadDocument32 pagesAdverse Drug Reactions: Dr. V. Jagadeesan, Former Deputy Director (Sr. Grade), National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabadapurupa1No ratings yet

- F4cd8a06d3a63e4463e31f34 PDFDocument3 pagesF4cd8a06d3a63e4463e31f34 PDFRinaldi InalNo ratings yet

- Drugs in PregnancyDocument98 pagesDrugs in PregnancyWilliamNo ratings yet

- Treatment of S Zo in PregnancyDocument8 pagesTreatment of S Zo in PregnancyTita Genisya SadiniNo ratings yet

- Drug in PregnancyDocument3 pagesDrug in PregnancyDaily DoseNo ratings yet

- K-19 Obat-Obat Dalam Masa KehamilanDocument31 pagesK-19 Obat-Obat Dalam Masa KehamilanChristian Lumban GaolNo ratings yet

- Epilepsy and Oral Hormonal Contraception-Indian Perspective: Review ArticleDocument6 pagesEpilepsy and Oral Hormonal Contraception-Indian Perspective: Review ArticleKirubakaranNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Progestogens in The Maintenance of Early Pregnancy in Women With Threatened Miscarriage or Recurrent MiscarriageDocument20 pagesEfficacy of Progestogens in The Maintenance of Early Pregnancy in Women With Threatened Miscarriage or Recurrent MiscarriagesilviuNo ratings yet

- AM DrugsDocument17 pagesAM Drugsstella.gillesania.chenNo ratings yet

- F3) P-GoutDocument8 pagesF3) P-Goutstella.gillesania.chenNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics by Cate Whittlesea and Karen HodsonDocument15 pagesClinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics by Cate Whittlesea and Karen Hodsonstella.gillesania.chenNo ratings yet

- F4) P-Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument11 pagesF4) P-Rheumatoid Arthritisstella.gillesania.chenNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy Handbook - ALLERGIC RHINITISDocument8 pagesPharmacotherapy Handbook - ALLERGIC RHINITISstella.gillesania.chenNo ratings yet

- Dear John Book AnalysisDocument2 pagesDear John Book AnalysisQuincy Mae MontereyNo ratings yet

- Enrico de Leus Froilan San JuanDocument16 pagesEnrico de Leus Froilan San JuanBryan Cesar V. AsiaticoNo ratings yet

- KAPILA User Guide 2023-24Document12 pagesKAPILA User Guide 2023-24SUTHANRAJ K SEC 2020No ratings yet

- Upload Documents For Free AccessDocument3 pagesUpload Documents For Free AccessNitish RajNo ratings yet

- Cicerone November PDFDocument8 pagesCicerone November PDFJay LaurenziNo ratings yet

- GAD Action PlanDocument4 pagesGAD Action PlanLance Aldrin Adion100% (1)

- Mobile Commerce Final Exam 2023 TP039612Document8 pagesMobile Commerce Final Exam 2023 TP039612Harshan BalaNo ratings yet

- Environmental ManualDocument7 pagesEnvironmental ManualHeni KusumawatiNo ratings yet

- Disha 1000 MCQ 7Document51 pagesDisha 1000 MCQ 7Jai HoNo ratings yet

- Human Action: A Treatise On Economics by Ludwig Von MisesDocument6 pagesHuman Action: A Treatise On Economics by Ludwig Von MisesHospodar VibescuNo ratings yet

- Training Report On Uti Mutual Funds: Kunal Agrawal Bba 5 Semester, September (08-11) Isb & M, KolkataDocument38 pagesTraining Report On Uti Mutual Funds: Kunal Agrawal Bba 5 Semester, September (08-11) Isb & M, KolkataArhum JalilNo ratings yet

- CHN ReviewerDocument10 pagesCHN ReviewerAyessa Yvonne PanganibanNo ratings yet

- WAEC Literature in English SyllabusDocument2 pagesWAEC Literature in English SyllabusLamin Bt SanyangNo ratings yet

- US Vs DIONISIO (Forcible Entry) G.R. No. L-4655Document3 pagesUS Vs DIONISIO (Forcible Entry) G.R. No. L-4655thelawanditscomplexitiesNo ratings yet

- People v. MadsaliDocument3 pagesPeople v. MadsaliNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- FilmDocument2 pagesFilmBlinky Antonette FuentesNo ratings yet

- PT Form 2 DANICADocument1 pagePT Form 2 DANICANoreen PayopayNo ratings yet

- Mr. Ranjit Kumar Paswan PDFDocument27 pagesMr. Ranjit Kumar Paswan PDFAysha SafrinaNo ratings yet

- ShowfileDocument179 pagesShowfileSukumar NayakNo ratings yet

- John Read Middle School - Class of 2011Document1 pageJohn Read Middle School - Class of 2011Hersam AcornNo ratings yet

- Simulacro 3 GildaDocument27 pagesSimulacro 3 GildamauricioNo ratings yet

- Gilgit BaltistanDocument4 pagesGilgit BaltistanJunaid HassanNo ratings yet

- Indian Legal & Constitutional History Syllabus PDFDocument2 pagesIndian Legal & Constitutional History Syllabus PDFkshitijNo ratings yet

- Rfi 230 Wall Finishing in StairsDocument1 pageRfi 230 Wall Finishing in StairsusmanNo ratings yet

- Bhakti - TheologiansDocument9 pagesBhakti - TheologiansHiviNo ratings yet