Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Moment in Warsaw

A Moment in Warsaw

Uploaded by

Roman GoerssCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Moment in Warsaw

A Moment in Warsaw

Uploaded by

Roman GoerssCopyright:

Available Formats

A Moment in Warsaw

by Roman Goerss

As the elevator doors clicked shut, it finally hit me. Since arriving in Warsaw a week earlier, something had been nagging at the edge of my thoughts, something different about the city I couldn't put my finger on, and as the elevator lurched upward, I realized what it was: no one smiles here. I was in a building called the Palace of Culture and Science in the center of Warsaw. A large central tower flanked by two smaller buildings, at 757 feet it remains the city's tallest structure, as its creator likely intended. The building was a "gift" from the mass-murderer Joseph Stalin to the Polish people during the mid-1950s, and I struggled to believe that the structure being shaped like a giant middle finger was a coincidence. Literally dwelling in the shadow of a symbol of Soviet-era oppression was characteristic of the mood I'd found in many parts of Poland, a country that had been invaded so many times it was difficult to keep track of the wars its people had endured. When I asked students at our camp whether they believed Poland would be invaded again in their lifetime, I always received one of two replies: "Yes," or "I don't like to think about such things." When I later asked why so many people in the city frowned or remained tight-lipped, my hosts would explain that it was customary in central Europe to be more reserved in one's facial expressions, yet I couldn't help but feel it symbolized a melancholy I sensed in the city's architecture. Having worked briefly in U.S. politics, I was accustomed to dealing with groups who framed their objectives in apocalyptic, life or death terms. Now, after walking the grounds of Auschwitz and the other Nazi death camps in Poland, it is difficult to summon the same intense anger at unfair zoning regulations and inefficient health policy I'd once felt. Politics seems more real here, more serious, and I feel ashamed to have ever used words like "inhumanity" or "evil" thinking I knew their meaning. Promoting freedom abroad feels different, like I am playing for keeps in a much larger and more dangerous game, and I worry about how few people seem to be on the side of freedom. Still, there is cause for hope. I was deeply impressed with the knowledge and enthusiasm of the attendees at our recent camp, the local Poles and other young people who'd journeyed from Albania, Belarus, southern Russia, and Italy. Our local partners, the Polish American Foundation for Economic Research and Education (PAFERE), were incredible, and we anticipate further ventures together. My musing was interrupted by the ding of the elevator, and I stepped out into the observation floor of the Palace, far above the streets of Warsaw. The view was quite impressive. "Would you like to buy something?" Startled, I turned from the window to see a young Polish woman surrounded by statuettes of the Palace and other tourist trinkets. "Wait a minute," I said "you mean to tell me that the former symbol of communist domination in Warsaw, built on the orders of Stalin himself, has a gift shop??" "Pretty much," she said, and for the first time in a long while, I saw a smile. The statuettes were overpriced, but I have to say I've never been a prouder participant in capitalism.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Delay Defeats EquityDocument5 pagesDelay Defeats EquityMercy NamboNo ratings yet

- City of Baguio vs. NiñoDocument11 pagesCity of Baguio vs. NiñoFD BalitaNo ratings yet

- New Deal Debate Lesson Plan OutlineDocument10 pagesNew Deal Debate Lesson Plan Outlineapi-284278077No ratings yet

- Peyton Last FinalDocument22 pagesPeyton Last Finalanon_501381No ratings yet

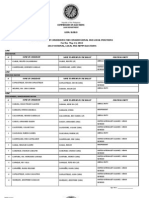

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Constitution and By-Laws: Teachers' LeagueDocument7 pagesConstitution and By-Laws: Teachers' LeagueYhielle Nopal100% (1)

- AP U.S. History Guided Reading:: Answer Sheet On Schoology When FinishedDocument4 pagesAP U.S. History Guided Reading:: Answer Sheet On Schoology When FinishedDominic Rodger EzNo ratings yet

- Employees Union of Bayer v. Bayer Phils.Document3 pagesEmployees Union of Bayer v. Bayer Phils.Trxc MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Vac-Sick Leave RequestDocument1 pageVac-Sick Leave RequestSivakumaran KandasamyNo ratings yet

- Araw NG Pagbasa Press Release v2Document1 pageAraw NG Pagbasa Press Release v2pribhor2No ratings yet

- CMFR Database On The Killing of Filipino Journalists/Media Workers Since 1986Document4 pagesCMFR Database On The Killing of Filipino Journalists/Media Workers Since 1986Center for Media Freedom & ResponsibilityNo ratings yet

- Fragmented Citizenships in GurgaonDocument11 pagesFragmented Citizenships in GurgaonAnonymous GlsbG2OZ8nNo ratings yet

- Manila Mail - March 1-15, 2014Document32 pagesManila Mail - March 1-15, 2014Winona WriterNo ratings yet

- DVM-Third Merit ListDocument1 pageDVM-Third Merit ListNadir Hussain BhuttaNo ratings yet

- University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences Lahore 1st Merit List On (05 Sep, 2020) For DVM (Morning)Document4 pagesUniversity of Veterinary and Animal Sciences Lahore 1st Merit List On (05 Sep, 2020) For DVM (Morning)Usman SadiqNo ratings yet

- Crime in India - 2016: Snapshots (States/Uts)Document14 pagesCrime in India - 2016: Snapshots (States/Uts)Isaac SamuelNo ratings yet

- 2010 01 08 - DR1Document2 pages2010 01 08 - DR1Zach EdwardsNo ratings yet

- President of PakistanDocument5 pagesPresident of PakistanhabibNo ratings yet

- View - Print Submitted FormDocument2 pagesView - Print Submitted Formᓬᔢᗯᕠᖇ ᑹᖆᗋᔡᕬᗠNo ratings yet

- Reception For Ron DeSantisDocument2 pagesReception For Ron DeSantisSunlight FoundationNo ratings yet

- Cities Service Oil Company, As Owner of The Steamship Cities Service Baltimore, Libellant-Appellant, v. The ARUNDEL CORPORATION, Respondent-AppelleeDocument3 pagesCities Service Oil Company, As Owner of The Steamship Cities Service Baltimore, Libellant-Appellant, v. The ARUNDEL CORPORATION, Respondent-AppelleeScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dictators and Other RulersDocument3 pagesDictators and Other RulersThavamNo ratings yet

- Astorga Vs VillegasDocument2 pagesAstorga Vs VillegasKaren Feyt MallariNo ratings yet

- Committee Meeting Minutes Apr. 08, 2019Document2 pagesCommittee Meeting Minutes Apr. 08, 2019RyoNo ratings yet

- DR.J.J IraniDocument19 pagesDR.J.J Iraniritusin67% (3)

- Open Letter To All Political Parties - Key Pledges To Be Included in ManifestosDocument4 pagesOpen Letter To All Political Parties - Key Pledges To Be Included in ManifestosSampath SamarakoonNo ratings yet

- CD - 96. PNB v. CedoDocument2 pagesCD - 96. PNB v. CedoCzarina CidNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14Document4 pagesChapter 14eraNo ratings yet

- General Studies - I Indian Heritage & CultureDocument4 pagesGeneral Studies - I Indian Heritage & CultureHexaNotesNo ratings yet