Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Soft Power in China's Foreign

Soft Power in China's Foreign

Uploaded by

mariajosemeramCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Proud Boys Telegram MessagesDocument141 pagesProud Boys Telegram MessagesDaily Kos100% (1)

- The Dragon Roars Back: Transformational Leaders and Dynamics of Chinese Foreign PolicyFrom EverandThe Dragon Roars Back: Transformational Leaders and Dynamics of Chinese Foreign PolicyNo ratings yet

- China's Soft Power: Discussions, Resources, and ProspectsDocument21 pagesChina's Soft Power: Discussions, Resources, and ProspectsTsunTsunNo ratings yet

- 2021 China Rising Threat' or Rising Peace'Document17 pages2021 China Rising Threat' or Rising Peace'Shoaib AhmedNo ratings yet

- China A Rising Soft Power: BDS-2B - 20L-1369 - Pakistan Studies - , 2021Document5 pagesChina A Rising Soft Power: BDS-2B - 20L-1369 - Pakistan Studies - , 2021Mansoor TariqNo ratings yet

- Soft Power With Chinese Characteristics: The Ongoing DebateDocument17 pagesSoft Power With Chinese Characteristics: The Ongoing DebateConference CoordinatorNo ratings yet

- Soft Power With Chinese Characteristics: The Ongoing DebateDocument17 pagesSoft Power With Chinese Characteristics: The Ongoing DebateKanka kNo ratings yet

- China and Peaceful Development EssayDocument12 pagesChina and Peaceful Development EssaydimpoulakosNo ratings yet

- (ARTIKEL JIRUD BAHASA INGGRIS) Bridging Towards Political PowerDocument21 pages(ARTIKEL JIRUD BAHASA INGGRIS) Bridging Towards Political PowerkevinndarmawanNo ratings yet

- Air Commodore Khalid Iqbal (Retd) : IPRI Journal XII, No. 2 (Summer 2012) : 127-136Document10 pagesAir Commodore Khalid Iqbal (Retd) : IPRI Journal XII, No. 2 (Summer 2012) : 127-136Sammar EllahiNo ratings yet

- Nathan & Zhang-2022-Chinese Foreign Policy Under Xi JinpingDocument16 pagesNathan & Zhang-2022-Chinese Foreign Policy Under Xi JinpingThu Lan VuNo ratings yet

- China's Soft Power: Effective International Media Presence From Chi-Fast To Chi-FilmDocument15 pagesChina's Soft Power: Effective International Media Presence From Chi-Fast To Chi-FilmJournal of Development Policy, Research & PracticeNo ratings yet

- China's Soft Power (Cho and Jeong 0806)Document21 pagesChina's Soft Power (Cho and Jeong 0806)juangabriel26100% (2)

- China's Cultural Future: From Soft Power To Comprehensive National PowerDocument21 pagesChina's Cultural Future: From Soft Power To Comprehensive National PowerCarlosNo ratings yet

- SS Haseeb Bin Aziz N0-4 2016Document16 pagesSS Haseeb Bin Aziz N0-4 2016shishir balekarNo ratings yet

- Does The Rise of China Support or Refute Realist Ir TheoryDocument4 pagesDoes The Rise of China Support or Refute Realist Ir Theoryrps94No ratings yet

- Is China A Threat To The WorldDocument7 pagesIs China A Threat To The WorldABRAHAM ALBERT DIAZNo ratings yet

- What China and Russia Don't Get About Soft PowerDocument3 pagesWhat China and Russia Don't Get About Soft PowerRômulo AguiarNo ratings yet

- Chinese Foreign Policy Making - A Comparative PerspectiveDocument6 pagesChinese Foreign Policy Making - A Comparative Perspectivefl33tusNo ratings yet

- The Power of Soft Power of China: Pradeep TandonDocument10 pagesThe Power of Soft Power of China: Pradeep TandonImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- China's Soft Power Diplomacy in Southeast AsiaDocument28 pagesChina's Soft Power Diplomacy in Southeast AsiaSotheavy CheaNo ratings yet

- Cheng - Analysing Chinese Foreign PolicyDocument7 pagesCheng - Analysing Chinese Foreign PolicyFrida Farah Velazquez TagleNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy Making Process A Case StuDocument11 pagesForeign Policy Making Process A Case StuSakim ShahNo ratings yet

- NarrativesDocument4 pagesNarrativeskishoresutradharNo ratings yet

- MEC - Chinese Soft PowerDocument5 pagesMEC - Chinese Soft PowerPaola Isabel Cano CanalesNo ratings yet

- Essay 04Document3 pagesEssay 04carvedblockNo ratings yet

- CNAS Report China IO PDFDocument32 pagesCNAS Report China IO PDFFrancisco Sanz de UrquizaNo ratings yet

- China's Cultural DiplomacyDocument21 pagesChina's Cultural DiplomacyZhao Alexandre HuangNo ratings yet

- Analisi Geopolitica CinaDocument12 pagesAnalisi Geopolitica CinaChiara ContinenzaNo ratings yet

- Khalid Saifullah and Irfan Hussain Qaisrani Vol 2 2023Document18 pagesKhalid Saifullah and Irfan Hussain Qaisrani Vol 2 2023Aaqib KhanNo ratings yet

- Hard-Soft-Smart-Sharp PowerDocument4 pagesHard-Soft-Smart-Sharp Powermatheusxavier90No ratings yet

- Rand Strategy Under Xi Jinping China's Grand Strategy Under Xi JinpingDocument38 pagesRand Strategy Under Xi Jinping China's Grand Strategy Under Xi JinpingAnon AnonononNo ratings yet

- Economic Statecraft in China's New Overseas Special Economic Zones: Soft Power, Business or Resource Security?Document19 pagesEconomic Statecraft in China's New Overseas Special Economic Zones: Soft Power, Business or Resource Security?Angie H FuentesNo ratings yet

- Bucharest University of Economic Studies Faculty of Business and TourismDocument7 pagesBucharest University of Economic Studies Faculty of Business and Tourism23andreiNo ratings yet

- The Rise of China and Its Power Status: Yan XuetongDocument29 pagesThe Rise of China and Its Power Status: Yan XuetongCarlosNo ratings yet

- Friedberg 2015Document23 pagesFriedberg 2015DiegoNo ratings yet

- VarrallDocument24 pagesVarrallrasulNo ratings yet

- China's Pandemic Power PlayDocument26 pagesChina's Pandemic Power PlaypaintoisandraNo ratings yet

- Concept of Soft Power inDocument28 pagesConcept of Soft Power inAntonina PogodinaNo ratings yet

- The American and Chinese Quests To Win Hearts and MindsDocument8 pagesThe American and Chinese Quests To Win Hearts and MindsAlex Von MendNo ratings yet

- 4 30 09cullDocument11 pages4 30 09cullAndreeaNo ratings yet

- China's Soft PowerDocument16 pagesChina's Soft PowerFANOMEZANTSOA VINCENTNo ratings yet

- The Rise of China, Balance of Power Theory and US National Security Reasons For OptimismDocument43 pagesThe Rise of China, Balance of Power Theory and US National Security Reasons For Optimismdwimuchtar 1367% (3)

- Chinese Eyes On Africa Authoritarian Flexibility Versus Democratic GovernanceDocument17 pagesChinese Eyes On Africa Authoritarian Flexibility Versus Democratic Governancemrs dosadoNo ratings yet

- Four Contradictions Constraining China's Foreign Policy BehaviorDocument9 pagesFour Contradictions Constraining China's Foreign Policy BehaviorŞeyma OlgunNo ratings yet

- Chinese Foreign Policy Under Xi JinpingDocument18 pagesChinese Foreign Policy Under Xi JinpingbillpetrrieNo ratings yet

- Appeasement DA: First The U.S. Is Containing China Now - The Pivot Proves. Mearsheimer 16Document17 pagesAppeasement DA: First The U.S. Is Containing China Now - The Pivot Proves. Mearsheimer 16Josh ChoughNo ratings yet

- China's Grand Strategy Isec - A - 00383Document38 pagesChina's Grand Strategy Isec - A - 00383anredo02No ratings yet

- 2021 China New Direction ReportDocument33 pages2021 China New Direction ReportMayAssemNo ratings yet

- China's Futures: PRC Elites Debate Economics, Politics, and Foreign PolicyFrom EverandChina's Futures: PRC Elites Debate Economics, Politics, and Foreign PolicyNo ratings yet

- Pov 010Document26 pagesPov 010Simbarashe HondoNo ratings yet

- El 'Poder Blando' de China en ÁfricaDocument11 pagesEl 'Poder Blando' de China en ÁfricaPilarNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal SampleDocument14 pagesResearch Proposal Samplebing zhuNo ratings yet

- Incrementalism, Normalisation, Partnership and Reassurance: PRC's Quest For Success in The 1990sDocument24 pagesIncrementalism, Normalisation, Partnership and Reassurance: PRC's Quest For Success in The 1990sKidsNo ratings yet

- Book Rep 2 Lyle Goldstein Meeting China HalfwayDocument9 pagesBook Rep 2 Lyle Goldstein Meeting China HalfwayKateryna BidulaNo ratings yet

- Public Diplomacy of People's Republic of China Anja L HessarbaniDocument15 pagesPublic Diplomacy of People's Republic of China Anja L HessarbaniDaniel PradityaNo ratings yet

- Wang The Economic Rise of ChinaDocument24 pagesWang The Economic Rise of ChinaPAMELA JULIETA GARCIA DI GRAZIANo ratings yet

- Living with the Dragon: How the American Public Views the Rise of ChinaFrom EverandLiving with the Dragon: How the American Public Views the Rise of ChinaNo ratings yet

- Xi Jinping and The Chinese DreamDocument7 pagesXi Jinping and The Chinese DreamShay WaxenNo ratings yet

- 5 Challenges in China's Campaign For International Influence - The DiplomatDocument3 pages5 Challenges in China's Campaign For International Influence - The Diplomatmanish shankarNo ratings yet

- RAISING PAN AMERICANS Early WDocument26 pagesRAISING PAN AMERICANS Early WmariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- Public Diplomacy Tools of PowDocument11 pagesPublic Diplomacy Tools of PowmariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- WSEAS TRANSACTIONS On ENVIRONMENT and DEVELOPMENTDocument7 pagesWSEAS TRANSACTIONS On ENVIRONMENT and DEVELOPMENTmariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- Soft Power IndiaDocument18 pagesSoft Power IndiamariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- Tourism Destination CompetitivDocument31 pagesTourism Destination CompetitivmariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- Culture and Organizations - SpringerLinkDocument16 pagesCulture and Organizations - SpringerLinkmariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- Covid Diplomacy in The Era ofDocument15 pagesCovid Diplomacy in The Era ofmariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- 1mapping The Presence of The KoDocument14 pages1mapping The Presence of The KomariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- Concerns or Desires Post-PandeDocument21 pagesConcerns or Desires Post-PandemariajosemeramNo ratings yet

- BDC Reso SRVDocument2 pagesBDC Reso SRVJohn Paul M. MoradoNo ratings yet

- Types of Leadership Styles: Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic Michael SangerDocument3 pagesTypes of Leadership Styles: Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic Michael Sangermehwish kashifNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Letter 201/1/2023: Engaging With Society: Meeting The Challenges of A Changing WorldDocument8 pagesTutorial Letter 201/1/2023: Engaging With Society: Meeting The Challenges of A Changing WorldFeroza AngamiaNo ratings yet

- MIC of MyanmarDocument2 pagesMIC of Myanmarsopheayem168No ratings yet

- Wilder, Gary (2015), "Freedom Time: Negritude, Decolonization, and The Future of The World. Durham: Duke University PressDocument401 pagesWilder, Gary (2015), "Freedom Time: Negritude, Decolonization, and The Future of The World. Durham: Duke University PressjmfiloNo ratings yet

- Redeeming The Prince: The Meaning of Machiavelli 'S Masterpiece. Maurizio ViroliDocument3 pagesRedeeming The Prince: The Meaning of Machiavelli 'S Masterpiece. Maurizio Virolicrobelo7No ratings yet

- Response: Richard PriceDocument12 pagesResponse: Richard Priceabimanyu setiawanNo ratings yet

- واقع وآفاق الاقتصاد الجزائري في ظل التكامل الاقتصادي الإقليمي المغاربيDocument22 pagesواقع وآفاق الاقتصاد الجزائري في ظل التكامل الاقتصادي الإقليمي المغاربيsaker soumayaNo ratings yet

- Idea of TelanganaDocument25 pagesIdea of TelanganaEd SheeranNo ratings yet

- Building National IntegrationDocument5 pagesBuilding National IntegrationnoumaNo ratings yet

- Lit 316 Activity Justinecastro JohnmarksantosDocument2 pagesLit 316 Activity Justinecastro JohnmarksantosJohn Mark SantosNo ratings yet

- Asia Pacific Viewpoint - 2021 - Lin - Theorising From The Belt and Road InitiativeDocument9 pagesAsia Pacific Viewpoint - 2021 - Lin - Theorising From The Belt and Road InitiativeBraeden GervaisNo ratings yet

- Functionalism Is A Theory of International Relations That Arose During The Inter-War PeriodDocument7 pagesFunctionalism Is A Theory of International Relations That Arose During The Inter-War Period259317No ratings yet

- COUNTRIES AND NATIONALITIES Exercises and KeyDocument5 pagesCOUNTRIES AND NATIONALITIES Exercises and KeyViviana Valencia PossoNo ratings yet

- Wa0000.Document2 pagesWa0000.jarinaparveen1807No ratings yet

- PDF Post Fascist Japan Political Culture in Kamakura After The Second World War Hein Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Post Fascist Japan Political Culture in Kamakura After The Second World War Hein Ebook Full Chapterronald.lamb361100% (1)

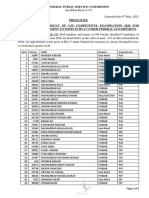

- Federal Public Service Commission: Merit Roll No. Name Domicile Group/ ServiceDocument9 pagesFederal Public Service Commission: Merit Roll No. Name Domicile Group/ ServiceMehar Mahmood Idrees100% (4)

- BSSD 103 Governance and Development Assignment 1 Part 1 Semester 1Document12 pagesBSSD 103 Governance and Development Assignment 1 Part 1 Semester 1TatendaNo ratings yet

- Filipinos Are Lazy?Document4 pagesFilipinos Are Lazy?Jason LambNo ratings yet

- 2 PDFDocument2 pages2 PDFnandi_scrNo ratings yet

- Penguatan Kapasitas Kelembagaan Remaja Masjid Dalam Upaya Peningkatan Kecakapan Sosial S0cul Skill RemajaDocument151 pagesPenguatan Kapasitas Kelembagaan Remaja Masjid Dalam Upaya Peningkatan Kecakapan Sosial S0cul Skill RemajaAhmad Ilham SipahutarNo ratings yet

- Đề 2303 - AME-HN-Ôn thi vào 10-MT (11 - 04 - 23)Document4 pagesĐề 2303 - AME-HN-Ôn thi vào 10-MT (11 - 04 - 23)Rubi AnhNo ratings yet

- The Idea of Intellectual Final 3Document2 pagesThe Idea of Intellectual Final 3Anindita karmakarNo ratings yet

- Malcolm X Essay PromptDocument3 pagesMalcolm X Essay PromptSam GitongaNo ratings yet

- 010 - Ucc1 Lien United States Corporation CompanyDocument11 pages010 - Ucc1 Lien United States Corporation Companyakil kemnebi easley el0% (1)

- Tugas Bahasa InggrisDocument9 pagesTugas Bahasa InggrisAnisa SabrinaNo ratings yet

- Dinamika Isu Republik Maluku Selatan (RMS) Terhadap Masyarakat Ambon Dalam Konflik 1999Document24 pagesDinamika Isu Republik Maluku Selatan (RMS) Terhadap Masyarakat Ambon Dalam Konflik 1999Yuke Tri hafsaniNo ratings yet

- Adjectives Describing People and Personal Qualities Vocabulary Word ListDocument9 pagesAdjectives Describing People and Personal Qualities Vocabulary Word ListabdlatifabhamidNo ratings yet

- Perspectives On International Relations Power Institutions and Ideas 5th Edition Nau Solution ManualDocument44 pagesPerspectives On International Relations Power Institutions and Ideas 5th Edition Nau Solution Manualevan100% (29)

Soft Power in China's Foreign

Soft Power in China's Foreign

Uploaded by

mariajosemeramOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Soft Power in China's Foreign

Soft Power in China's Foreign

Uploaded by

mariajosemeramCopyright:

Available Formats

JUSTYNA SZCZUDLIK-TATAR

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

Determinants

The launch by Deng Xiaoping of the “policy of reform and opening” in 1978

is an important landmark in the contemporary history of China. An autarkic,

closed state associated with economic and social experiments of “the Great Leap

Forward,” “people’s communes” and the “Cultural Revolution” and underpinned

by Marxist theories of class struggle and export of revolution embarked, after

a protracted power struggle and the death of the chief ideologist of these doctrines,

upon the process of modernization. Freedom of economic activity—albeit

unaccompanied by political freedoms, with this state of affairs attributed to the

Confucian tradition—has been promoted by China as proof that it is possible to

build a modern Asian state that incorporates selectively Western values while

remaining faithful to its civilizational achievements. Deng’s reforms have been

continued by his successors. China has shown high economic growth year after

year, it is active on the international scene, engages in resolving global issues,

pursues economic and diplomatic expansion in developing countries, promotes

economic integration with Asian states and works towards solving border issues

with its neighbors.

These activities, as well as China’s growing spending on the military and on

a space program, have been giving rise to apprehensions in other states. The

early 1990s saw the emergence of perceptions of a “China threat,” chiefly in the

U.S. Attention was being drawn to the fact that China posed a threat to stability

in Asia, sought to change the balance of power in the region and to challenge the

United States.1 The China threat was highlighted during the first term of

G.W. Bush’s presidency, when the American administration treated China as

a rival. U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice spoke of China as a potential

threat to stability in the Asia and Pacific region and she maintained that China

1

K. R. Al-Rodham, “A Critique of the China Threat Theory: A Systematic Analysis,” Asian

Perspective, 2007, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 42–44.

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 45

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

was not a status quo power.2 The realization by the Chinese authorities that the

country’s development could cause uneasiness worldwide was, presumably, the

foremost reason for deliberately using soft power tools to project a positive

image of the PRC.

The second factor was a drop in U.S. popularity resulting from the

G. W. Bush administration’s methods of conducting the war on terror and, in

consequence, from the reduced American involvement in Africa and Latin

America. This offered China a chance to use a particular space that had emerged

in these regions and to attempt a rivalry with the United States—an undertaking

made possible also by China’s economic successes achieved year after year and

making it increasingly confident of its position. The PRC launched a diplomatic

offensive, using soft power tools and focusing on the developing countries. The

stepping-up of activity in these regions was due both to their economic

attractiveness and to their need for development support, which China can offer.

What is more, China’s development level and potential—even its political

system—hold appeal for these states.

Using soft power is one of the ways to realize the most important Chinese

interests. Accordingly, soft power is subordinated to the foreign policy aims,

which include: to continue reforms and economic development and, in this

connection, to search abroad for a raw materials base and sales markets; to

ensure security in the region; to pursue the one-China principle (to establish

diplomatic relations with the states that still maintain official relations with

Taiwan); to win the developing states’ goodwill, so that they support China in

the UN (for instance, on human rights, on the isolation of Taiwan, or on blocking

Japan’s permanent membership in the UN Security Council). The strategic aim

is to regain the superpower status. The superpower issue has been an unchanging

element of China’s foreign policy since the empire era. It is worth noting that

since the early 1990s Chinese researchers and decision-makers have applied an

analytical construct known as comprehensive national power (CNP—in

Chinese, zonghe guoli) to assess the level of general power of a nation-state

using mathematical formulas. At present the United States comes first in CNP

2

C. Rice, “Campaign 2000: Promoting the National Interest,” Foreign Affairs, 2000, vol. 75,

no. 1, p. 56.

46 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

ratings.3 Soft power is meant to help China move up to precisely this position.

Presumably Beijing wants to achieve this aim in 2049, on the hundredth

anniversary of the establishment of the PRC. 4

Defining Remarks and the Chinese Perspective

Joseph S. Nye defined power as the ability to change the behavior of others

to achieve the desired result by such means as reward, punishment, or attraction.

The first two are attributes of hard power consisting of a state’s military and

economic might, while attraction is the defining factor of soft power. Nye

describes soft power as a way to attain the desired results through appeal,

seduction and attraction. Soft power is neither persuasion, influence, sanction

nor a payment for proper behavior. It is not about inducing and coercing a certain

behavior, but about skillfully shaping the preferences of others. According to

Nye, three types of resources (sources) constitute soft power: culture, in particular

its elements having appeal for others; values, including political values realized

by a state in its internal and external policy; and foreign policies. The possession

of soft power resources does not automatically ensure the effectiveness of soft

power. It is the context of actions and the tools applied that matter. Depending

on the context and the recipient’s attitude, soft power can carry a positive

message, attract, and thereby help achieve the intended objective—but it can

also discourage and repulse. Soft power tools are not defined absolutely; they

are not confined within a single cohesive catalogue. Whatever leads to promotion,

increased attractiveness, and whatever attracts attention and, consequently,

shapes the preferences of others, can be classified as a soft power tool.

Even though soft power and its resources have been defined, this is a vague

concept giving rise to numerous controversies. The identification of its sources,

in particular the inclusion of economic issues in hard power, is debatable.

A question arises through the prism of which power—hard or soft— humanitarian

aid, or official development assistance (ODA) as an element of economic policy,

should be viewed. In view of numerous debates on the correctness of Nye’s

definition and typology, in literature on Chinese soft power economic issues are

almost invariably taken into account on the grounds that they are a meaningful

3

Hu Angang, Men Honghua, The Rising of Modern China: Comprehensive National Power and

Grand Strategy, 2002, www.irchina.org.

4

J. Rowiñski, “Chiny: nowa globalna potêga? Cieñ dawnej œwietnoœci i lat poni¿enia,” in:

A. D. Rotfeld (ed.), Dok¹d zmierza œwiat, Warszawa, 2008, p. 371.

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 47

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

element of China’s diplomatic activity. Also in this study a proportion of

activities of an economic nature are included in soft power.

In China the soft power concept has met with considerable interest. Chinese

scholars and officials subscribe for the greater part to the Nye definition, even

though they differ on the resources and tools. In the debate on the Chinese

perception of soft power, launched in 1993 following the publication of the first

article on this issue,5 two strains of thought have developed. One, represented

mainly by Chinese sociologists and philosophers and shared by a majority of

Chinese decision-makers, regards culture as the paramount source of soft power.

The other strain, a minority one represented by experts on international relations,

suggests that soft power should be perceived through the prism of tools rather

than sources, since it is the former that determine the effectiveness of actions.

Proponents of this strain argue that political power—which they define as an

ability to create agendas, establish international institutions and propose new

solutions advantageous both to the initiator state and to other actors, and

projecting a positive image6—is the principal tool.

In the Chinese authorities’ official rhetoric soft power is perceived through

the prism of culture. However, practice shows that—besides using tools that

draw from cultural sources—political (diplomatic) and economic instruments are

also widely used. Their significance—and perhaps also changes in the perception of

soft power by the Chinese authorities—is evidenced by statements of PRC

Chairman Hu Jintao at the 11th conference of ambassadors in 2009, when he

referred (albeit indirectly) to the strengthening of soft power in the political and

economic fields and announced an expansion of China’s diplomatic activity into

other regions.7

5

Wang Huning, “Zuowei guojia shili de wenhua: ruanquanli” (Culture as National Power: Soft

Power), Fudan Daxue Yuebao, 1993, no. 3.

6

B. S. Glaser, M. E. Murphy, “Soft Power with Chinese Characteristics: The Ongoing Debate,”

in: Chinese Soft Power and Its Implications for the United States: Competition and Cooperation

in the Developing World, CSIS, Washington, D.C., 2009; Yan Xuetong, Xu Jin, “Zhong mei

ruanshili bijiao” (Comparison of Chinese and American Soft Power), Xiandai Guoji Guanxi,

2008, no. 1; Yu Xintian, “Ruanshili jianshe yu zhongguo duiwai zhanlüe” (The Role of Soft

Power in Chinese International Strategy), Guoji Wenti Yanjiu, 2008, no. 2.

7

Dishiyici zhuwai shijie huiyi zai jing zhaokai (11th Conference of Ambassadors Held in Beijing),

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, 20 July 2009.

48 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

Tools of Chinese Soft Power

It seems that an appropriate criterion by which to classify the tools of

Chinese soft power is a division of the sources from which soft power is derived.

Based on the analysis of China’s activity, three groups of sources (resources) can

be identified: culture, foreign policy and economic policy.

The first group of tools is linked with cultural and educational diplomacy,

where China applies two strategies: of “inviting in” (qing jinlai) and of “going

out” (zou chuqu). The “inviting in” strategy concerns activities in China itself

and it consists in creating suitable conditions to attract foreigners to China. At

home these people become, owing to their personal experiences and direct

contacts, China’s “emissaries,” as it were. The “going out” strategy covers

activities conducted abroad and targeted at recipients outside China. The object

is to reach people hitherto not interested in China, to enhance their knowledge

about the country and to shape their views on China.

Under the “inviting in” strategy China employs tools of an educational

nature. They include: projects to improve the quality of education at Chinese

institutions of higher education with a view to attracting foreign students; the

development of Chinese language study programs for foreigners; an educational

offer for foreign students; and a program of government scholarships. Among

the tools of a cultural nature the promotion of tourism figures prominently,

including efforts to have as many historical sites as possible added to the

UNESCO World Heritage List.

In the “going out” strategy, a network of Confucian Institutes developed

since 2004 is the most visible instrument. The Institutes operate under the

auspices of the Ministry of Education and of the Chinese National Office for

Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language (Hanban), with these institutions

known to have a substantial promotional budget. The objective of the Institutes

is to promote the teaching of Chinese abroad. Once a year the Institutes hold

Chinese proficiency competitions for foreign students, known as the “Chinese

Bridge” (Hanyu Qiao). The winners of national rounds take part in the final

competition in China. The Institutes also operate as foreign centers for the HSK

exam (Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi), a Chinese equivalent of the TOEFL test.

The tools of a strictly cultural nature include organizing festivals of Chinese

culture and exhibitions of Chinese art abroad, participation in international film

and theatrical contests and book fairs, as well as the China Book International

program to support the translation of Chinese literature into foreign languages

and its popularization abroad.

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 49

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

The media are another important soft power instrument classifiable as

a “going out” strategy tool. Improvement of information policy, including media

targeted at foreign audiences, merits attention. For instance, a number of Chinese

web sites in many languages, targeted at foreign readers, have been set up. In

1992 the CCTV-4 television channel was established, broadcasting in Mandarin

Chinese language to the Chinese diaspora and the residents of Hong Kong,

Taiwan and Macao. It was the first Chinese TV channel available abroad. In

2000 an English-language information channel CCTV-9 was established,

followed in the following years by channels broadcasting in Spanish, French,

Arabic and Russian.

Major international events organized by China should also be regarded as

soft power tools. One example were the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, which

the PRC used as an opportunity to promote its cultural achievements (a monumental

pageant presenting the history of Chinese civilization shown during the opening

ceremony) and the country’s might (China ranked first in the medal table).

Another opportunity for China was the 2010 Expo Shanghai.

The second group of China’s soft power tools is derived from foreign policy

resources. Major and highly visible instruments include frequent official and

unofficial visits abroad by Chinese officials, both top- and lower-ranking.

Invitations are also extended to other states’ leaders, with rich media coverage

later provided for such visits. Besides official visits, China has organized

informal summits designed to highlight China’s role as an important partner and

the significance of a given country for the PRC.

The Chinese leadership attaches great importance to professional diplomatic

staff. Diplomats are prepared for being posted to a concrete state and region and

they remain linked with that region throughout their professional career. Rarely

are they appointed to culturally and geographically different states. The diplomatic

corps has been steadily rejuvenated and foreign posts have been filled by better

and better prepared officials, who usually command the language of the host

country.

Involvement in the work of international organizations is a tool through

which China wishes to be perceived as a responsible partner. The mistrustful and

passive attitude of the 1990s has been replaced by active participation in

numerous institutions. China is a member of global and regional organizations.

Significantly, not only has it joined the existing organizations, but it has also

initiated setting up new institutions or cooperation forums. Dovetailing with this

50 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

trend is also a good neighborhood policy reflected in regional integration and in

resolving border issues or toning down the related rhetoric.

China has also changed its attitude towards UN peacekeeping missions.

Today participation in these missions is one of more important Chinese soft

power tools. Disparagement of these missions through emphasizing the principle

of non-intervention and respect for the sovereignty of other states, that hallmark

of the period between 1971 and 1978, began to change in the 1980s and 1990s.

After the authorities realized that staying away from the missions marginalized

China’s international position, damaging its image, arousing the sense of China

threat and obstructing the pursuit of its interests, China has increasingly been

involved in peacekeeping.8

The third group of tools draws from economic sources. China has been

applying economic diplomacy, or aid diplomacy, chiefly towards states in need

of support which find the Chinese offer attractive, predominately in Africa,

Latin America and Asia. Aid is provided by writing off debts and making

preferential-term loans, mainly for infrastructure projects, such as the

construction of roads, railways or public utility buildings. A loan is usually made

subject to recognition by the borrower state of the one-China principle and to

a guarantee that Chinese firms will have a sizable stake in project

implementation. The reason for the latter is that these firms (generally selected

by the authorities) use their own equipment and labor, often in exchange for

deliveries of raw materials. Chinese investment projects are another tool. It is

common practice for Chinese companies to form joint ventures with local

companies, mostly in construction, mining or the fuel industry. Humanitarian aid

provided by China in case of natural and man-made disasters is also significant

for China’s image. It covers both financial assistance and dispatch of Chinese

rescue teams to disaster-struck areas.

Chinese Soft Power in Practice Illustrated by Selected Regions

China directs the broadest spectrum of its soft power tools to where the

scope for its action is relatively wide (whether due to other states’ lower interest

in a given region or to failures of other states’ policies) and where it sees

8

China’s National Defence 2008, Appendix III, China’s Participation in UN Peacekeeping

Operations, January 2009, www.gov.cn; B. Gill, Chin-Hao Huang, “China’s Expanding

Peacekeeping Role: Its Significance and the Policy Implications,” SIPRI Policy Brief, February

2009, p. 2; J. Rowiñski, P. Szafraniec, “ChRL a misje pokojowe ONZ,” Stosunki Miêdzy-

narodowe, 2008, nos. 1–2 (vol. 37).

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 51

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

a chance of realizing its economic and political interests. It has been active in

Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia—though it should be noted that it has

also been engaged in the Middle East and in Central Asia, i.e. in areas where the

influences of the U.S. and Russia are fairly strong. It can be said with much

certainty that China will gradually expand its involvement to the remaining

regions, including Europe; this, presumably, will be the task of a new Chinese

leadership to emerge in 2012 and 2013. 9

The following sections will outline Chinese soft power activity only in three

regions where China’s presence has been relatively long for reasons of historical

experience or geographical proximity: in Latin America, Africa and Southeast

Asia. Given the variety and large number of undertakings in these areas, this

study does not aspire to presenting all of them. The purpose is to analyze the

phenomenon itself, and the examples presented are but a modest fragment of the

catalogue of activities undertaken by the PRC.

Latin America

Underlying China’s activity in Latin America are economic aims, first of all

to ensure access to raw materials, sales markets and investment opportunities.

Additionally, China seeks to turn the one-China principle into reality by

establishing diplomatic relations with those states in the region that still maintain

official relations with Taiwan. Of the 23 countries which recognize Taiwan, as

many as 12 are Latin American.

In 2008 China adopted a document which laid down the objectives and tasks

of its policy towards the region. The document, permeated with Aesopian

rhetoric, contains a significant passage which refers to Latin America as a region

abounding in natural resources that constitute a large development potential—an

indirect indication of China’s main interests in the region.10 China has taken

efforts to emphasize the importance of relations with individual states through

the tightening of bilateral relations—a purpose served by mutual visits at the

level of heads of state and government. These contacts have expanded demonstrably

since 2001, when PRC Chairman Jiang Zemin paid a nearly two-week visit to

countries in the region. Thereafter many Chinese delegations have come to Latin

America, including two visits (in 2004 and 2008) by Chairman Hu Jintao

9

Hu Jiantao’s term as secretary general of the CPC ends in 2012, and his term as PRC chairman

—in 2013.

10

China’s Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean, www.gov.cn.

52 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

himself. In 2009 PRC Vice-chairman Xi Jinping visited Jamaica, Colombia,

Venezuela, Brazil and Mexico, while Chinese Vice-premier Hui Liangyu paid

a visit to Argentina, Barbados, Ecuador and the Bahamas. The PRC signed

bilateral strategic partnership agreements with Brazil, Venezuela, Mexico and

Argentina; free trade agreements with Chile, Peru and Costa Rica; and numerous

sectoral agreements.11

The PRC has been involved in the work of regional organizations. Since

2004 it has been a permanent observer in the Organization of Latin American

States, a member of the East Asia-Latin America Cooperation Forum

(FOCALAE), and a member of the APEC. Also, China cooperates with the

Inter-American Development Bank and the Caribbean Development Bank,

a relationship facilitating the distribution of aid in countries of the region.

China’s participation in the United Nations stabilization mission in Haiti

reflects its involvement in the region and its responsibility for security there.

This is the first UN mission in Latin America with China’s participation.

That said, the most widely used instruments are those of an economic nature.

They are meant to help realize China’s economic interests, “link” states in the

region with China and convince them of the benefits of China’s activity. The

accompanying rhetoric, assurances of cooperation based on mutual benefits

(“win-win” strategy) and the principle of non-interference in other states’

internal affairs are designed to create a positive image of the PRC. Concrete

tools range from preferential loans—chiefly for infrastructure projects, in

exchange for access to raw materials—to debt-forgiving and investment. China

is interested in receiving from the region oil, natural gas, copper, iron, lead,

nickel and aluminum; these resources are obtainable mainly from Brazil, Chile,

Argentina, Venezuela, Peru, Cuba and Ecuador.

China has been increasing its investment in the region. Three Chinese oil

groups: China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec), China National

Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and China National Petroleum Corporation

(CNPC) are present in Latin America. For instance, in 2004 Sinopec invested

US$1 billion in a joint venture with Petrobras of Brazil to build an oil pipeline

connecting the north and the south of Brazil.12 The Chinese company Baosteel

11

China’s Foreign Policy and “Soft Power” in South America, Asia, and Africa. A Study Prepared

for Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate, Washington, D.C., 2008, p. 16.

12

A. Castillo, “China in Latin America,” The Diplomat, 18 June 2009; China’s Foreign Policy...,

op. cit., p. 24.

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 53

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

jointly with Vale do Rio Doce of Brazil invested in the construction of a steel

mill in the state of Espirito Santo in the south of Brazil. This US$3-billion

project was financed by the Chinese company (60%) and by the Brazilian

partner (40%).13 During PRC Vice-chairman Xi Jinping’s 2009 visit to Brazil the

two sides signed an agreement under which the China Development Bank

undertook to lend Petrobras US$10 billion to finance oil exploration, while

Brazil agreed to deliver 100,000 barrels of oil per day to China.14 In Venezuela

the CNPC set up a joint venture with the state-owned Petroleos de Venezuela;

this arrangement enabled China to extract oil from 15 oil fields in the country. In

Peru the CNPC bought shares in Pluspetrol, which holds oil fields along the

border with Ecuador. Chinese firms are also interested in modernizing Peru’s

pipelines to facilitate the transport of oil to ports on the Pacific coast.15

Moreover, China Aluminum Corporation (Chinalco) will invest, over 30 years,

more than US$2 billion in one of the world’s most productive copper mines at

Toromocho in central Peru. The extraction of this raw material necessitates the

removal of the local population. The Chinese company offered compensation of

US$1,000 and dwellings elsewhere. In a referendum held among the inhabitants

a majority accepted this arrangement.16

Aid provided by China is a very important instrument of building a positive

image of China and of “linking” Latin American states economically. Support

provided to Grenada in reconstruction after the Ivan hurricane in 2004; to Peru

after the 2007 earthquake; and to Haiti after the powerful earthquake in 2010 are

cases in point. Aid is provided also to states which have severed diplomatic

relations with Taiwan, as a reward, as it were, for supporting the one-China

principle—but also to those which continue to maintain official relations with

Taipei, as a means of persuading their governments to recognize the PRC. For

instance, before the 2007 cricket World Cup, China helped build sports stadiums

in Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, Jamaica—and even in Saint Lucia, which

maintains official relations with Taiwan.17

13

Jiang Shixue, “The Panda Hugs the Tulcano: China’s Relations with Brazil,” China Brief,

15 May 2009, vol. 9, no. 10, p. 8.

14

Ibidem; E. Ellis, “China’s Maturing Relationship with Latin America,” China Brief, 18 March

2009, vol. 9, no. 6, p. 5.

15

J. Kurlanzick, “China’s Latin Leap Forward,” World Policy Journal, fall 2006, p. 38.

16

E. Ellis, “China’s Maturing Relationship...,” op. cit., p. 5; J. Simpson, “Peru’s ‘Copper Mountain’

in Chinese Hands,” BBC, 17 June 2008.

17

China’s Foreign Policy..., op. cit., pp. 26–27.

54 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

It is difficult to state unequivocally how effective the Chinese soft power

activities have been. One way to approach the assessment of their effectiveness

is to analyze China’s diplomatic successes and failures in a given region or state,

and international opinion surveys.

In 2004 Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru and Venezuela granted China market

economy status (MES). Also, the severing of diplomatic relations with Taiwan

by three Central American states and the establishment of relations with China

should be seen as China’s diplomatic success. In 2004 the Dominican Republic

established official relations with Beijing—presumably under the influence of

a promise of over US$100 million in Chinese aid. In 2005 Grenada broke

relations with Taiwan, and in consequence it received from China an assurance

of substantial financial aid after the 2004 Ivan hurricane, plus support to its

agriculture and a scholarship program.18 In 2007 Costa Rica established diplomatic

relations with China. The PRC offered to purchase US$300 million worth of

Costa Rican bonds, provide US$130 million in financial aid and set up a scholarship

program; it also declared itself interested in building an oil refinery in this

country, and Costa Rica cancelled Dalai Lama’s visit scheduled for 2008. 19

Signs of effectiveness of Chinese soft power notwithstanding, there have

been noticeable failures. It should be regarded as a failure that 12 states in the

region maintain official relations with Taiwan.20 China’s hope for a domino

effect to follow the establishment of diplomatic relations by the Dominican

Republic, Grenada and Costa Rica has not materialized. It should be seen as

a failure that Saint Lucia re-established diplomatic relations with Taiwan in 2007

after ten years of official relations with Beijing. Yet another example is the

emerging displeasure in states in the region with the growth of the Chinese

diaspora, whose members take jobs away from local workers, with low safety

standards in Chinese firms in the region, and with too intensive exploitation of

natural resources detrimental to the natural environment. What is more, states in

the region claim that cheap imports from the PRC have been hurting their

economies. In 2005 the president of Brazil authorized the introduction of

anti-dumping tariffs and temporary restrictions on imports of Chinese goods,

18

Ibidem, pp. 17 and 26–27.

19

D. P. Erikson, “China’s Strategy toward Central America: The Costa Rican Nexus,” China

Brief, 27 May 2009, vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 6–7.

20

These are: Belize, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras,

Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Christopher and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the

Grenadines.

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 55

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

mainly textiles, to Brazil.21 Some states have also been concerned that they

might become too dependent on Chinese investment and that local firms entering

into joint ventures with China might be treated merely as sub-contractors. These

concerns have been voiced in Ecuador. Following the investment by China in

2006 of about US$1.5 billion in the acquisition of the Ecuadorian assets

of EnCana, a Canadian group, the government of Ecuador rescinded China’s

oilfields rights which had been part of the agreement and made it sign a new

agreement permitting oil production only. A Hong-Kong-based company

Hutchison Whampoa was also forced to give up its concession to operate the

Port of Manta in connection with a pending dispute over the fulfillment by the

government side of its contractual obligations.22 However, in 2009, with Ecuador

plunged in a grave economic and financial crisis, the president of Ecuador

mollified his attitude towards China and he encouraged China to invest. 23

Opinion polls, that seemingly most reliable measure of the effectiveness of

soft power activities, indicate that perceptions of China by the states in the

region are for the greater part positive. In a poll conducted by the BBC in 2005

in Chile, Argentina and Brazil, positive views of China dominated (respectively,

56%, 44% and 53%).24 A similar poll conducted in 2009 by the same center

showed 62% of positive perceptions of China in the Central American countries

and 60% among the population of Chile. A similar trend emerges from Pew

Global [Attitudes Project] surveys. In Brazil, favorable views of China

accounted for 50% in 2007, for 47% in 2008 and again for 50% in 2009. In

Argentina positive opinions of China reached 32% in 2007, 34% in 2008 and

42% in 2009. Also, Brazil and Argentina treat China as a partner (poll results

being, respectively, 49% and 45%).25

Based on the above examples of effectiveness and ineffectiveness of China’s

soft power activities a thesis can be ventured that despite positive opinions about

China in the region, China’s position there is neither strong nor well-established.

This is evidenced by shifts in the different states’ attitudes in response to

external determinants (such as the economic crisis or modifications of U.S.

21

Jiang Shixue, “The Panda Hugs the Tulcano...,” op. cit., p. 9.

22

E. Ellis, “China’s Maturing Relationship...,” op. cit., p. 5.

23

J. Llangari, “Hit by Crisis Ecuador Makes Sales Pitch to China,” Reuters, 13 February 2009.

24

22 Nation Poll Shows China Viewed Positively by Most Countries, www.worldpublicopinion.org.

25

Most Muslim Publics Not So Easily Moved. Confidence in Obama Lifts U.S. Image Around the

World: 25-Nations, www.pewglobal.org, pp. 44–45.

56 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

policy towards the region). Given the geographical distance between China and

Latin America and the region’s traditionally strong relations with the U.S., there

seems to be little promise of China’s deep and long-term involvement.

Presumably China is aware of this, as implied by the focus it puts on economic

issues while steering clear of issues of a political or ideological nature. Under

the circumstances, the overriding aim is to use to the greatest possible extent the

region’s natural resources as a prerequisite for the PRC’s further economic

development.

Africa

The African continent is another area of China’s activity. China’s increased

involvement in Africa has been in evidence since 2000. The underlying

considerations are, like in Latin America, economic: to ensure the supply of

resources for the burgeoning Chinese economy and to build markets for Chinese

goods. China’s policy towards Africa has been determined by its thirst for

resources. Its political aims—to enlist the support of African states as non-

permanent members of the UN Security Council, or (albeit to a lesser extent than

in Latin America) to have Taiwan pushed into diplomatic isolation—are

subordinated to the economic objectives. At present four African states maintain

official relations with Taiwan: Burkina Faso, Swaziland, Gambia, and São Tomé

and Príncipe. China also wants to build up its international position by

demonstrating its responsibility for states in the region.

China has been pursuing its targets through both bilateral and multilateral

contacts. In 2000 a Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) was established

at China’s initiative. The FOCAC meets every three years, alternately in China

and in one of the African states. The third FOCAC meeting held in Beijing in

2006 assembled representatives of 48 African states—a symbolic event in that it

emphasized these countries’ rank in relations with China. During the forum

Chairman Hu Jintao presented the essential tasks China wanted to realize by

2009 with a view to tightening its relations with Africa. They were: to double aid

to Africa through the provision of US$3 billion in preferential-term loans and

US$2 billion in credit; to establish a US$5 billion China-Africa development

fund as a way of supporting Chinese businesses and encouraging their

investment in Africa; to build an African Union conference center; to cancel the

poorest African countries’ debts; to continue the opening of the Chinese market

to African products and to increase (from 190 to 440) the number of

duty-exempt products exported by the poorest African countries to China; to

create three to five trade and economic cooperation zones. Furthermore, there

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 57

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

were declarations to build 30 hospitals, to provide a RMB300 million grant for

the construction of 30 malaria prevention and treatment facilities, to build 100

schools in rural areas, and to increase the number of state scholarships for

African students, from 2,000 to 4,000 annually.26 The meeting adopted an action

plan for 2007–2009 which set down in detail the targets presented by Chairman

Hu Jintao.27

The most recent FOCAC meeting took place in October 2009 in Egypt. At

the meeting an action plan for 2010–2012 was adopted. China offered African

countries a US$1 billion loan for the development of small and medium-sized

African businesses; the cancellation of debts of the poorest countries having

diplomatic relations with the PRC; US$1.5 billion in financial support to health

programs; an increase, to 5,500 by 2012, of the number of government

scholarships. Furthermore, China undertook to train African personnel and it

offered African scientists opportunities to conduct research in China. 28

In January 2006 China published an official document defining its policy

towards Africa. The document emphasizes the importance of Africa to China

and the similarity of historical experiences (colonialism). Noteworthy is

a provision on an important role in the UN of the African states, “which strive

for the realization of the principle of equality of states.” With respect to the

economy as an area of cooperation, emphasis is placed on the development of

trade, investment, assistance, debt cancellation and cooperation with resource-

rich states.29

The rank of African states in China’s policy is borne out by Chinese leaders’

frequent visits to the region. Besides top-level political meetings, the PRC

organizes business forums with African entrepreneurs. For instance, at one such

meeting held in Ethiopia in 2003 contracts worth about US$680 million were

signed.30

United Nations’ peacekeeping missions in Africa are China’s important soft

power tool. At present more than 75% of Chinese personnel participating in

26

Full text: Address by Hu Jintao at the Opening Ceremony of the Beijing Summit of the Forum on

China-Africa Cooperation, 4 November 2006, www.focacsummit.org.

27

Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action Plan (2007–2009), 16 November 2006,

www.fmprc.gov.cn; China’s Foreign Policy..., op. cit., p. 110.

28

Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Sharm El-Sheik Action Plan (2010-2012), www.focac.org.

29

China’s African Policy, 12 January 2006, www.fmprc.gov.cn.

30

J. Eisenman, J. Kurlantzick, “China’s Africa Strategy,” Current History, May 2006, p. 221.

58 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

missions abroad is deployed in Africa.31 The PRC participates in missions in

Western Sahara, the Ivory Coast, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan,

and Sudan’s Darfur.32 It also offers de-mining assistance by training personnel

and providing equipment in such regions as Angola, Mozambique, Chad, Burundi,

Guinea-Bissau, Sudan, Egypt and Ethiopia.33 As yet another noteworthy initiative,

China has sent three of its ships to the waters of Somalia to protect commercial

vessels against pirates. This is a precedent: for the first time the Chinese Navy is

operating outside the Pacific.

Broadly construed aid is yet another soft power tool. It is provided on

a package basis. China has granted preferential loans without demanding

commitments in respect of democratization or observance of human rights, and

it has cancelled existing debts. As in Latin America, lending is usually for

infrastructure projects and loans are offered subject to guarantees of Chinese

firms’ considerable participation in the implementation of contracts.34 Chinese

firms carry out contracts using their own equipment and they employ Chinese

workers—a practice resented because, while unemployment in the host country

remains high, jobs go to the growing Chinese diaspora. The Chinese expatriate

communities are estimated to have grown in the past ten years to 30,000 (from

3,000) in Zambia and to 300,000 in South Africa. Aid is usually disbursed

during informal meetings of the ambassadors of African states to Beijing, or

before Chinese officials’ African visits. It is distributed via the Export-Import

Bank of China, the China Construction Bank, or Chinese diplomatic missions in

African countries. Eligible for this aid are the authorities of a given state, state

institutions, or state-owned enterprises. Aid to non-governmental institutions is

not part of the established practice.35 In return for the support received, African

states provide China with access to raw materials. Prominent examples of aid

include: the sports stadiums built in Gambia and Sierra Leone; the Ministry

of Foreign Affairs’ building in the capital of Mozambique, Maputo;36 the

31

D. H. Shinn, “Chinese Involvement in African Conflict Zones,” China Brief, 2 April 2009,

vol. 9, no. 7, p. 7.

32

B. Gill, Chin-Hao Huang, “China’s Expanding Peacekeeping Role...,” op. cit., p. 2.

33

D. H. Shinn, “Chinese Involvement in African Conflict Zones,” op. cit, p. 8.

34

J. Kurlantzick, “Beijing’s Safari: China’s Move into Africa and Its Implications for Aid,

Development, and Governance,” Policy Outlook, November 2006.

35

Ibidem.

36

J. Eisenman, J. Kurlantzick, “China’s Africa Strategy,” op. cit., pp. 219–221.

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 59

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

Parliament building and the country’s largest sports stadium in the Congo; and

roads, railways and telecommunication systems built or modernized in many

other countries in the region. 37

Angola, a state with the second-largest oil deposits in Africa, is an example

of Chinese investment known as aid-for-resources. In 2004 China offered

Angola a US$2 billion loan for the upgrading of infrastructure, on the condition

that 70% of related contracts were set aside for Chinese firms. By 2007 the loan

was increased by another US$2 billion. Angola has been repaying it with

deliveries of oil to China at a rate of over 520,000 barrels per day.38 Following

China’s offer of support, Angola, which had been negotiating terms of aid with

the International Monetary Fund, broke off these talks.

A survey conducted by the BBC in 2009 in Ghana and Nigeria showed that

the majority of opinions about China were positive (75% and 72%,

respectively).39 According to a Pew Global survey 75% of the Nigerians had

a favorable view of China in 2007, and 85% in 2009. In Kenya the figures were,

respectively, 81% and 73%.40 Moreover, it should be seen as a success of

China’s African policy that a number of states broke off diplomatic relations

with Taiwan in favor of the PRC: the Republic of South Africa, the Republic of

Central Africa and Guinea-Bissau in 1998; Liberia in 2003; Senegal in 2005;

Chad in 2006; and Malawi in 2007. 41

Yet African states have also indicated their displeasure with Chinese activity

in the region. China has been accused of causing environmental degradation by

too intensive mining, and of disregard of working conditions. Zambia is a case in

point. Since 2005 protests have been staged there against the presence of

Chinese firms, with the protesters claiming that working conditions are poor,

pay low and payments overdue. During Hu Jintao’s 2009 visit a scheduled trip to

a mine was cancelled for fear of worker protests.42 During recent elections in

Zambia an opposition candidate who accused Chinese firms of exploiting local

37

Wenran Jiang, “Chinese Inroads in DR Congo: A Chinese ‘Marshall Plan’ or Business?” China

Brief, 12 January 2009, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 9.

38

J. L. Parenti, “China-Africa Relations in the 21st Century,” JQF, 2009, no. 52, p. 119;

J. Kurlanzick, “Beijing’s Sarafi...,” op. cit.

39

Views of China and Russia Decline in Global Poll, www.worldpublicopinion.org.

40

Most Muslim Publics…, op. cit.

41

J. L. Parenti, “China-Africa Relations in the 21st Century,” op. cit.

42

“Exploited Workers Protest Against Chinese Company,” Asia News, 3 May 2008.

60 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

labor has won considerable support. He also championed breaking off

diplomatic relations with Beijing and establishing relations with Taipei. China

intervened, warning that a victory of the opposition candidate would result in the

severing of relations and in the withdrawal of Chinese aid and investment (China

is Zambia’s important investor, in particular in the copper sector).43 Similar

objections to China have been voiced by other states. The Republic of South

Africa objects to cheap imports from China, Gambia accuses Sinopec of having

concealed data on the actual impact of oil mining on the environment, while in

Ethiopia there have been kidnappings of employees of Chinese oil companies.

Notwithstanding indications of displeasure with Chinese presence in the

region, and despite the distance separating China and Africa, this is an area

where China has a chance to stabilize and strengthen its position. A tradition of

mutual contacts (viz. the Bandung conference or China’s foreign policy strategy

of the 1960s seeking cooperation with developing countries, including in Africa)

works in China’s favor. China’s future in Africa will depend on how it makes use

of its potential. By putting its seal of approval on the aid-for-resources system

—a corruption-breeding, non-transparent scheme which, as in Nigeria, increases

the indebtedness of the aid-recipient country—it will undermine its position in

the region. On the other hand, if it works towards a better balance between the

soft and hard tools, responding promptly to a given country’s or a given region’s

needs, and—as in Angola44—implements more fully the “win-win” strategy, it

will improve its chance of succeeding in Africa.

Southeast Asia

Asia remains the priority direction in China’s foreign policy. The paramount

objective of the activity in Asia is to ensure security and stability in the region as

a prerequisite for China’s further economic development. This objective has

been pursued by resolving border issues with its neighbors, by integration

(mainly economic) via organizations of a regional nature, by setting up free

trade zones, or through Asian business forums. Furthermore, China is seeking to

establish itself as the region’s leader and, consequently, to have the region

recognized in fact as a Chinese influence zone.

43

J. L. Parenti, “China-Africa Relations in the 21st Century,” op. cit.

44

For more on China’s policy in Nigeria and Angola see A. Vines, L. Wong, M. Weimar,

I. Campos, Thirst for African Oil: Asian National Oil Companies in Nigeria and Angola,

London, 2009.

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 61

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

The different methods of winning Asian states’ goodwill are wrapped in

a rhetoric invoking common Asian roots (Asian values: Confucianism, Buddhism),

similar historical experiences, and the principle of mutual advantages (“win-

win”), which is emphasized in all areas of China’s activity. China’s activities in

Asia have been dubbed the Chinese “Monroe Doctrine” for an alleged similarity

between the PRC’s current policy in the region and the building of an American

influence zone in the western hemisphere in the 19 th century.45

The beginnings of China’s soft power activities in Asia date back to 1997,

i.e. to the Asian crisis. The absence of firm activity by the U.S. in curbing the

crisis and misguided decisions by the International Monetary Fund offered

China an opportunity to demonstrate its position. At the time the PRC refused to

depreciate the yuan, a stance which enabled the economic situation to stabilize

and major problems on the international capital market to be averted. This

decision earned China the goodwill of Asian states, particularly members of the

ASEAN, an organization China has been cooperating with since the early 1990s

and in which it has enjoyed a partner status (ASEAN Dialogue Partner) since

1996. In 2000 China put before the ASEAN countries a proposal to set up a free

trade zone, one of the largest in the world. Two years later a framework

agreement was signed, providing for the establishment of a free trade zone

comprising China and the ASEAN. In 2010 the zone embraced six relatively

developed countries: Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore

and Thailand. In 2015 the other ASEAN countries will join in.46 The importance

of the ASEAN and of other states in the region in the policy of the PRC is

confirmed by other forms of institutional cooperation with these countries.

China participates in meetings of ASEAN+1 (the Association members plus

China), ASEAN+3 (the Association members plus China, Japan and South

Korea), in the East Asia Summit comprising the ASEAN states, China, Japan,

South Korea, India, New Zealand and Australia, and in the ASEAN Regional

Forum, which draws together the Association members and 17 states in Asia and

in the European Union, as well as Australia and the U.S. Moreover, China has

initiated other forms of cooperation with the ASEAN countries, such as the

annual China-ASEAN Expo with its accompanying event, the China-ASEAN

45

J. Kurlantzick, “China’s Charm: Implications of Chinese Soft Power,” Policy Brief, June 2006,

no. 47, p. 4.

46

T. Lum, W. M. Morrison, B. Vaughn, “China’s ‘Soft Power’ in Southeast Asia,” CRS Report for

Congress, 4 January 2008, p. 15; A. Gradziuk, “Implications of ASEAN-China Free Trade

Agreement (ACFTA),” PISM Bulletin, no. 8 (616), 19 January 2010.

62 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

Business and Investment Summit held in China since 2004, or the Boao

economic forum in the Hainan Island in China—an event modeled after the

Davos forum in terms of organization and format.

Serving to ensure stability in Asia is a “good neighborhood policy.” It is

reflected primarily in efforts to ensure stability in the neighboring countries

through solving border disputes or softening their rhetoric. At the 2002 summit

under the ASEAN+3 formula a declaration was signed on the conduct of parties

on the Spratley Archipelago, which is an object of a dispute among China,

Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei. Although the

declaration merely preserves the status quo rather than settle the dispute, China

recognizes as a fact the right of other states to raise claims. In January 2009

China ended a dispute over land borders with Vietnam and has toned down the

rhetoric of its dispute over the Paracel Archipelago. In 2003 the PRC acceded to

the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia which promotes respect

for the territorial integrity and sovereignty of states in the region, non-interference in

their internal affairs and renunciation of the use of force. Improvement in

China-Taiwan relations in the wake of the island’s 2008 elections and growing

economic integration between those two actors also dovetail with the good

neighborhood policy. Regular direct air and sea connections have been

established between the PRC and Taiwan, and China has consented to the

island’s participation—in an observer capacity and under the name of Chinese

Taipei—in the World Health Assembly (WHO’s decision-making body).

Close bilateral relations maintained with Asian states and the provision of

economic aid are important soft power tools. For instance, China has provided

aid to Burma in the form of loans (in 2006 it promised US$200 million in loans)

and support to infrastructure projects in the extraction industry (natural gas, oil)

and road, railway and airport construction.47 In addition, Burma received US$10

million in aid after the cyclone that had hit it in 2008.48 In return, it signed in

2007 an agreement with China on oil and gas exploration off Burma’s coast.

Moreover, China undertook to build pipelines from Burma to the cities of

Kunming and Chongqing in China.49 This is a project of strategic importance

47

T. Lum, W. M. Morrison, B. Vaughn, “China’s ‘Soft Power’ in Southeast Asia,” op. cit., p. 6.

48

H. H. M. Hsiao, A. Yang, “Transformations in China’s Soft Power toward ASEAN,” China

Brief, 24 November 2008, vol. 8, no. 22, p. 12.

49

T. Lum, W. M. Morrison, B. Vaughn, “China’s ‘Soft Power’ in Southeast Asia,” op. cit.,

pp. 11–12.

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 63

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

because the pipeline, bypassing as it will the Malacca Straits, will reduce

dependence on U.S.-controlled sea routes. Similar practices have been employed

in relations with Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, resulting in agreements between

Chinese and Vietnamese firms for the exploitation of oil and gas reserves in the

Tonkin Gulf and a similar agreement with the Cambodian side on the extraction

of these resources from deposits in Cambodia.50 The much-promoted principle

of non-interference in internal affairs of other states helps realize China’s

interests in Asian countries, because it enables China to invest in countries under

sanctions as well as in those where other states’ activity (U.S. in particular) is

lower. For instance, following the withdrawal of Philippine troops from Iraq in

2004, the United States markedly scaled down its aid to this country. The PRC

then came up with its offer during a visit paid by Philippine President Gloria

Arroyo to Beijing.51

China is perceived by the Asian states as an important partner in the region.

This is evidenced by such moves as Cambodia’s giving up in 1998 its informal

relations with Taiwan or cancellation of Dalai Lama’s visit in 2002 at the request

of the Chinese authorities. In 2001 the Thai government refused to allow

a meeting of Falun Gong activists to be held in Thailand, and Indonesia and

Malaysia followed suit.52 China’s growing role in the region was borne out by

the 2008 appeal by the leaders of Cambodia, Laos and the Philippines for more

Chinese investment in the region to stabilize the situation in the face of the

global crisis.53 As yet another proof of the efficiency of Chinese soft power,

ASEAN is said to adopt decisions upon considering China’s position or potential

reaction—in particular concerning Burma, Cambodia and Thailand.54. What is

more, opinion polls confirm China’s positive image in the region. In a survey

conducted in Thailand in 2003, China was indicated as the country’s closest

friend by more than two-thirds of the respondents, while only 9% named the

U.S.55 In BBC surveys conducted in 2005 in Indonesia and the Philippines,

50

Ibidem.

51

J. Kurlantzick, “China’s Charm Offensive in Southeast Asia,” Current History, September

2006, p. 272.

52

Ibidem, p. 275.

53

H. H. M. Hsiao, A. Yang, “Transformations in China’s Soft Power toward ASEAN,” op. cit.,

p. 13.

54

J. Kurlantzick, “China’s Charm Offensive...,” op. cit., p. 140.

55

Bates Gill, Yanzhong Huang, “Sources and Limits of Chinese ‘Soft Power,’” Survival, summer

2006, vol. 48, no. 2, p. 24.

64 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

positive views on China dominated (68% and 70%, respectively).56 In Malaysia

a Pew Global survey conducted in 2008 revealed that 83% of the public had

positive opinions on China. 57

On the negative side, China’s involvement in the region could be causing

excessive degradation of the environment through over-intensive mining of raw

materials and river regulation. Standing out as a potential source of failures of

Chinese soft power are China’s activities in the Mekong Delta. This area,

encompassing China’s Yunnan province and parts of Burma, Cambodia, Laos,

Thailand and Vietnam, is a food basket for the countries in the region—an

important source of river fauna and an arable land. The proposed construction by

China of new dams upstream the river could change significantly its

watercourse, affecting adversely the water level and fish resources in Cambodia,

just as it could interfere with rice farming in Vietnam. China refused to join the

Mekong River Commission, an inter-governmental agency comprising four

riparian states situated on the lower reaches of the river.58 To date, despite the

controversy over the construction of dams on the Mekong, the authorities of the

Delta states have been disinclined to criticize China’s conduct for fear of losing

aid and political support. Yet this is a potential source of disagreements in the

region and it undermines the effectiveness of China’s soft power.

Yet another factor likely to weaken the effectiveness of China’s soft power

are ethnic disagreements between China and the region’s countries with large

Chinese diasporas. The number of Chinese in Southeast Asian countries is

estimated at some 30 million, with the largest expatriate Chinese communities in

Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. The diaspora is accused of transferring

profit to China, a practice strongly resented by native populations, of Sinizing

the host countries (these concerns are reflected in the Chinese diaspora being

described as the fifth column), and so on. Yet, unlike Latin America, where

geographic distances and the involvement of other actors in the region undercut

the effectiveness of activities, the Asian area has been linked with Chinese

influences for centuries. In the face of globalization processes Southeast Asia

seems to have no alternative to cooperation with China. It seems that the

56

22 Nation Poll Shows China Viewed Positively by Most Countries, 5 March 2005, www.world

publicopinion.org.

57

Global Economic Gloom—China and India Notable Exception: 24-Nation Pew Global

Attitudes Survey, www.pewglobal.org, pp. 39–46.

58

M. Richardson, Dams in China Turn the Mekong Into a River of Discord, 16 July 2009,

www.yaleglobal.yale.edu.

The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3 65

Justyna Szczudlik-Tatar

employment of soft power tools meant to project a warmer image of the PRC

and the playing down of conflict-breeding issues reflect a rational approach by

Chinese diplomacy, as this increases the likelihood of attaining the most

important aims in the region.

Conclusions

The deliberate employment of soft power tools by Chinese diplomacy

reflects growing pragmatism of Chinese foreign policy and could be a challenge

to other actors—first of all to the U.S., but also to the European Union. The very

scale of Chinese activities as well as their multidirectionality and the multiplicity

of the tools employed warrant such a conclusion. In summing up these

deliberations on Chinese soft power it is worthwhile to consider its strengths and

weaknesses, because their definition could be helpful in taking action designed

to enhance, for instance, the European Union’s soft power and to derive benefits

from China’s diplomatic activity.

The strengths of Chinese soft power include:

– diplomatic offensive in regions “neglected” by other actors, notably by

the U.S. and the European Union. China’s involvement in many regions, such as

Africa, Latin America or Asia, is a specific effect of scale not to be disregarded

by other states;

– centralization of activities, which improves decision-making and

implementation and prevents a protracted negotiation process;

– highlighting of common bonding elements. One example here is the

practice of invoking the colonial past, which makes possible the building of

a community of experience, or even of a victim mentality;

– aid in the form of preferential-term lending or implementation of

infrastructure projects. The visible evidence of this aid are newly-built roads,

schools, hospitals and other public utility facilities (a kind of product

placement);

– de-linking aid from democratization processes, or from plans for its use

and future settlement;

– highlighting the principle of sovereignty and non-interference in internal

affairs of other states and the freedom to choose a political system and

development model;

– frequent visits by Chinese leaders to the target countries of the PRC’s

diplomatic offensive. These visits boost the partners’ self-esteem;

66 The Polish Quarterly of International Affairs, 2010, no. 3

Soft Power in China’s Foreign Policy

– initiating integration processes (mainly in Asia) through setting up new

organizations, cooperation forums, or informal regional and sub-regional summits;

– involvement in matters of security and peace, reflected in the changed

attitude towards UN peacekeeping missions; projecting the image of a state